Extracts from MA Thesis

Master in Contemporary Circus Practices 2018–2020

Saar Rombout, Stockholm University of the Arts

Artistic Practice

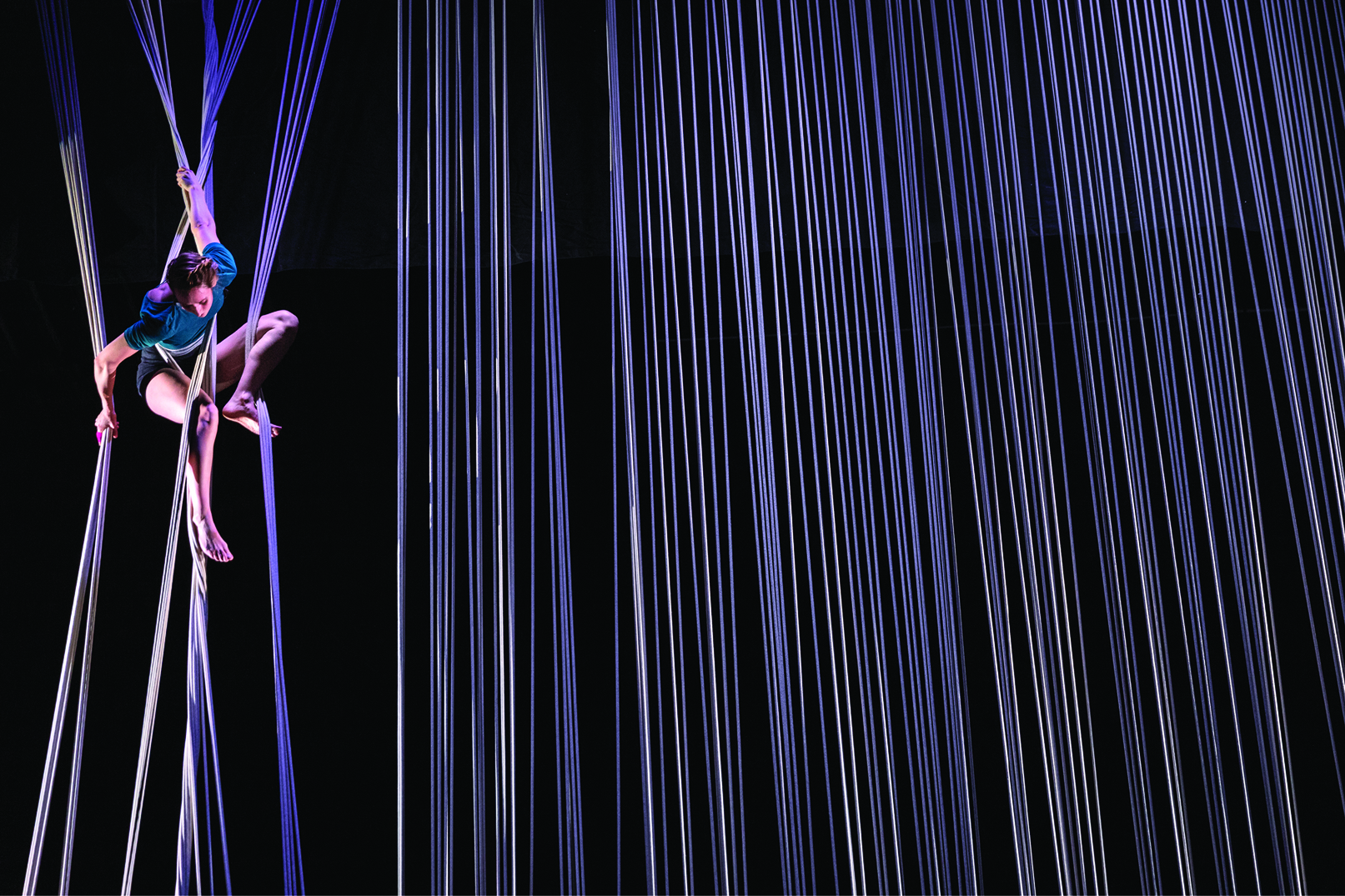

This project is a preliminary research into opening up a conversation and discussion about what creative rigging and rigging design can mean in circus, what roles the rigger can have and how rigging can be both a technical tool and an essential element in the artistic process. In circus, the way you move is very closely linked to the apparatus you use. By designing new apparatuses or rigging constructions with which circus artists may intra-act,1 I create new potential ways to move. The installation works partly as a score or a script for the performers to interpret and collaborate with, rather than being just an instrument that humans use to do tricks. Working with ropes and knots is often seen as a craft, instead of an art form, but I think it can be both.

Craft

The way I work with the ropes, the material sensibility that I have with them, is a kind of craftsmanship. In The Craftsman, Richard Sennett describes craftsmanship as highly skilled work with good coordination between head and hand that combines thinking and doing with an appreciation for quality and doing good work for its own sake (9). What does it mean to do good quality work, and how do you achieve it? Sennet suggests three ways of developing quality through skill:

Problem solving and problem finding.

Filling a quiver: the assembling of skills which are more than a one-to-one match between challenge and response.

Working with resistance rather than fighting it.

For Sennet, problem solving and problem finding mean that there is not just one fixed solution for each problem; he calls single solution a “cognitive death sentence.”2 Instead, it is better to explore different ways of solving a problem to find new things that need improvement. So each time you solve a problem, you should try to find new problems at the same time. There are no solutions that do not open up other problems, and every problem has multiple solutions. This is the kind of problem solving that allows you to develop technically on your own. This is learning by experimenting, not by a teacher telling you the perfect solution or a set formula.

The second one is the quiver, which is where an archer keeps their arrows. There is no one-to-one correspondence between means and end. There is not one single best practice. The more arrows you collect in that quiver, the more means you have for creative expression. The more versatile you are in the way you do something, the more you can react to what is happening and play with it instead of needing everything to go according to a fixed plan. This also builds confidence that you can meet the challenges that different circumstances will bring.

Sennet explains that the way to work with resistance instead of fighting it is to apply minimal force. A carpenter hammering into a piece of wood, who encounters a hidden knot, will lighten their blows in order to test and explore what is there. The use of minimal force is all about what Sennett calls the dialectics of resistance, which is how the artist or craftsman learns to befriend resistance and explore it before dealing with it. One should investigate. Perhaps there is a promising reason hidden in why something isn’t working smoothly. Using minimal force in response to resistance allows curiosity to come into play. The moment that there is resistance and you explore it is when you are most in touch with the material.

A practice that begins as explicit knowledge becomes tacit when a specific technique becomes ingrained in your body. As your skill level increases, you find out that one technique you have learned doesn’t fit if you do something slightly different. Because there is resistance there is an explicit unpacking at that point. Something has to go wrong to re-explore or reconsider a technique. You then learn a variation of techniques and the creation of a new practice, which then becomes tacit again. You develop a notion of experimentation from within without having to think about it. A technique does not get better by doing the same thing over and over again, but by getting to know all the slight variations to performing the same kind of activity. You learn from difficulty and ambiguity.

Learning is an education of attention. Embodied knowledge or tacit knowledge takes time to acquire. You cannot learn it from a book, it can only be learned through practice. Developing your own practice means discovering and identifying what the integral parts are for you. Some parts will only be known to you, and it may not yet be clear how other parts relate to the rest of your practice. It is not always important to know. The important thing is that you want to know, investigate and explore.

I think there is a lot of craftsmanship involved in circus. In a circus school, you learn a lot of technical skills. You need these techniques to become familiar with your body, the apparatus or material you work with and the space. You are learning to pay attention to details that you never knew existed and to find potential you never thought possible. Circus scholar Vincent Focquet suggests craft as a way to read material agencies better, to look for ways to deal with them and to follow the material. Craft opens the possibility to skilfully make things in more than human worlds, which could be a leading tactic for doing circus (Focquet 46).

Starting to see circus as a craft, will require new conceptualizations of knowledge, in which knowledge is not confined to the timeframes before and after physical practice. Rather, craft calls for a conceptualization of thinking that is happening in and through practice. In other words: a paradigm in which doing circus is thinking circus. (Focquet 49)

As you hear about sculptors who chip away bits of stone to let the sculpture hidden inside reveal itself, I feel like that about the ropes sometimes. I do not necessarily decide what I am going to make. Often, I have images in my mind inspired by all the things I see and experience from other objects and people, but that is not the same as what comes out of the ropes. I often work from intuition. I build models and draw things that exist in my mind, and I feel the need to bring them into another reality and dimension. When I start looking for material in the workshop to build a model, there are certain things that jump out and call out to be used. It is hard to explain this without personifying it. The space and time to let those things appear or come out without a fixed plan is a luxury that I have been able to enjoy during my MA research. I have been able to develop my craft, thinking through crafting and exchanging and sharing my practice with a group of like-minded people who challenge how I think and how I do things.

Designers must know about materiality; they must be familiar with how materials can be bent and manipulated to a purpose. But a designer must also know people: how they interact with objects, how they relate to the future state of affairs encapsulated in a designed object, and how they feel. […] To design is to bring about new things in the world. These things that are not just occupying space; they are fulfilling a purpose, and they have meaning on their own. To design is to create meaningful things for meaningful uses, understanding different uses and different materials. (Sicart 87–88)

Rigging

I have been interested in knots and forces since a very young age. This interest grew the more I worked with ropes as my circus discipline. During my bachelor’s degree in circus and performance art, I also became interested in the rigging involved in circus. I love the math and physics involved, the problem-solving mentality of it, and I also thought it was important as an aerialist to know what you are hanging from. Your life is literally on the line. I really enjoyed working both as a rigger and as a performer, but there seemed to be a big separation between them. I do not know if that came from my own expectations or the value I felt that was put on it by the world around me, but the two roles definitely were not on the same level.

After falling on my sacrum in 2017 in Costa Rica, I was hardly able to walk and could not perform. I felt very strongly that I had to prove somehow that I was still a performer. It was hard to be in a place where everyone knew me by how I moved and performed and then not be able to move like I normally did. It felt like a big part of my identity was taken away from me. In the end, it made me appreciate all the other facets involved in performances so much more. The injury helped me recognize how many other aspects of circus I enjoyed and was good at. I toured as a rigger and a stage manager. I designed and sewed costumes. I taught and was involved in the creation of shows. These were all things that I had done before in some way, but were underappreciated by myself and others around me. They came easily to me, so I never really noticed them. The challenge of performing, on the other hand, made me feel like I had to prove that I could do that as well. Now, I can move again like I could before. However, the importance I give to different parts of my practice has been changed by this experience. Performing is no longer the central thing that everything else circles around. Rigging, designing and organizing have become more intrinsic parts of the way I create and practice my artform.

One of the things I have always liked about circus is that, for me, it never felt really competitive because everyone does something different. Even so, there is still a strong drive for many circus artists to be strong, virtuoso and original. You do have to compete for work, and there are circus festivals that are competitions. This encourages this competitiveness. However, I am happy that it does not feel so competitive in the circus circles where I usually spend time. Putting competitiveness on hold opens up space for collaboration between artists, performers and audiences.

The hierarchy that exists not only within circus but also in general in the performing art world is very fixed. When I started writing this piece, I wanted to write about how creative rigging can be more than just something technical. This made me realize that by saying it in such a way, I maintain the same hierarchical norms that I wish to surpass. Many circus artists probably think that they are not treating technicians differently from other performers, but it is amazing how big the difference is between how I am treated when I work as a performer and as a rigger by artists, venues and organizers. The fact that I am a female rigger reveals other hierarchies. I feel like I first have to prove that I really know what I am doing before people will accept that I can do this job, while it is automatically assumed that most of my male colleagues will be able to do their job well. There are many hierarchies or dualities that I would like to see change: artist/rigger, human/nonhuman, art/craft, performer/audience, male/female.

Over the years, and especially during my master’s research, rigging has become as important as my movement practice, and it has developed into an essential part of my artistic practice. The way I designed the rigging would affect the way I moved and intra-acted with the ropes. This movement, in turn, gave me new ideas for how to redesign the rigging. Each rope installation I design and build reveals many possibilities and potential roads to take, and it creates different futures for myself or other artists to explore.

Notes

- Intra-action is a term coined by Karen Barad as the mutual constitution of entangled agencies. See Adams, Erin, Kerr, Stacey, Pittard, Beth. “Three Minute Theory: What is Intra-Action?” YouTube, uploaded by Three Minute Theory, 20 Nov. 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v0SnstJoEec. Accessed 30 Aug. 2022. ⮭

- See Sennett, Richard. “Richard Sennett: Craftsmanship.” YouTube, uploaded by MAK - Museum für angewandte Kunst, Wien, 12 Oct. 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nIq4w9brxTk. Accessed 30 Aug. 2022. ⮭

References

Adams, Erin, Kerr, Stacey, Pittard, Beth. “Three Minute Theory: What is Intra-Action?” YouTube, uploaded by Three Minute Theory, 20 Nov. 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v0SnstJoEec. Accessed 30 Aug. 2022.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v0SnstJoEec

Focquet, Vincent. To Withdraw to a Humble Circus, Three Dramaturgical Tactics. 2019. Ghent University, MA dissertation. Universiteitsbibliotheek Gent, https://lib.ugent.be/catalog/rug01:002789946.https://lib.ugent.be/catalog/rug01:002789946

Sennett, Richard. The Craftsman. Penguin, 2009.

Sennett, Richard. “Richard Sennett: Craftsmanship.” YouTube, uploaded by MAK - Museum für angewandte Kunst, Wien, 12 Oct. 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nIq4w9brxTk. Accessed 30 Aug. 2022.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nIq4w9brxTk

Sicart, Miguel. Play Matters, MIT Press, 2014.