I am at the end of a trilogy that has taken six years to make. I feel both a sense of completion and an awareness that I am not done. There’s so much more work to do, politically. As I write this, there is legislation pending in San Francisco’s City Hall1 to consider whether or not to catalogue and account for the AR-15s, BearCats, military assault vehicles, tanks, pepper balls and breaching devices that the city owns. The militarization of our city streets is so connected to the problem of mass incarceration. It’s difficult to be an artist in public schools, surrounded by children in need and the accompanying lack of resources to support them, and witnessing the money spent on war machines aimed against the parents of those same children. Facing the ongoing fact of America’s prison industrial complex, I choose perseverance. I choose dancing off the ground to conjure joy. I choose to integrate bodies in flight into the social justice equation. Pushing against gravity, I look up, stand up, fight back.

Who is this art for?

Politically speaking, repair is complicated. It requires time, perseverance and some opening of the heart, and it needs to be nurtured by trauma-informed processes.

In 2021 and 2022, I led the creation of a site-specific performance project grounded in my belief that alternatives to incarceration create more public safety than prisons and punishment-driven caging. Apparatus of Repair is the third installment in a trilogy of public art projects called The Decarceration Trilogy: Dismantling the Prison Industrial Complex One Dance at a Time. This trilogy centres principles of Restorative Justice and gathers currently and formerly incarcerated people, as well as survivors of violence. Over two years, we dove into restoration via a vicarious restorative process, knowing that the conversations we generated would inform the creation of site-specific public art.

It started for me in 2011, when my partner was given a long sentence in federal prison. It started in 2018, when I began connecting with the women of Essie Justice Group, an organization of women with incarcerated loved ones. It started when Kevin Martin, a Restorative Justice facilitator at Community Works in Oakland, CA and I met in a restorative circle for a teen who had harmed someone in his family. The young man’s case was diverted from the courts to Community Works, an organization that serves youth with alternatives to incarceration. Kevin and I entered the circle as community members, sharing what we know about assault, harm, self-worth and boundaries. This circle led Kevin and I to get to know each other, and I asked him to lead the restorative component of Apparatus of Repair.

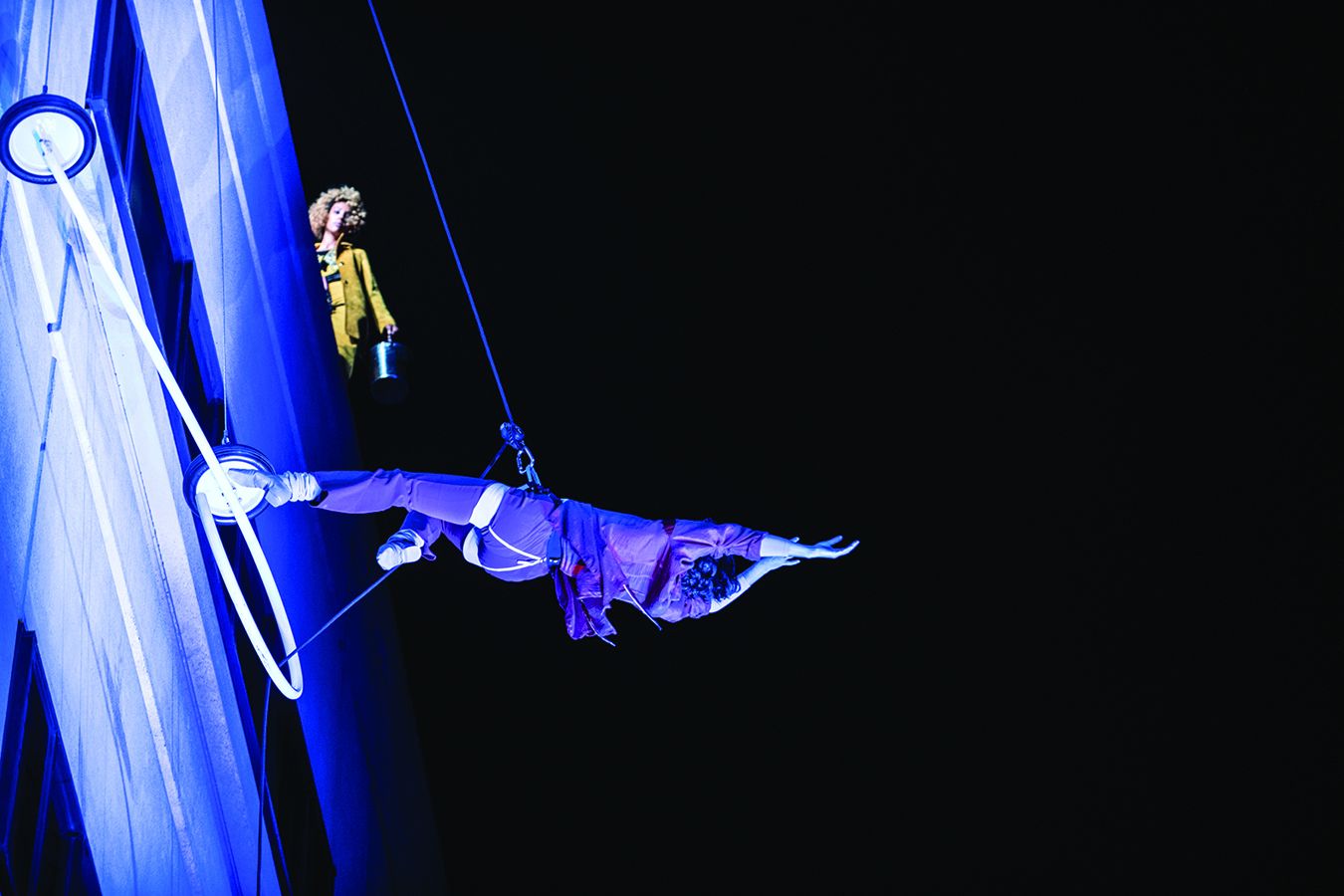

The project generated three Restorative Justice (RJ) processes and the premiere of an aerial performance on the San Francisco College of the Law, a six-story law school (see the video link at the start of this text for footage of excerpts of Apparatus of Repair, 2022). This performance was created with currently and formerly incarcerated people—a team including dancers, designers, and a composer—and survivors of violence. It toured the East and West Coasts of the USA, and we are hoping for continued touring.

Restorative Justice has as many definitions as modern dance or contemporary circus. It has many sides and applications. It is a fast-growing social movement offering potent, effective solutions to harm. It centres agency, which former director of the Ella Baker Center Zach Norris describes in his book Defund Fear as “the antidote to trauma.”2 Restorative Justice causes less damage and holds more hope than our current legal system. At its best, it is a community-driven process; rather than focusing on the punishment meted out, it measures results by how successfully the harm is repaired. It views crime as a violation of people and relationships rather than a violation of the state and the law. It is survivor-centered, accountability-based, safety-driven and racially equitable.

The creation of Apparatus of Repair was process-driven, and the final project encompasses engineering experiments, aerial choreography, physical risk and a sound score grounded in the experiences of people who have been in prison or impacted by violent crime. The artists translated ideas of over-policing and under-policing in communities of colour; the moment of really looking in the mirror and acknowledging that you have caused harm; cycles of harm from childhood violence to perpetuating violence; and the ways harm can live in one’s body for years after it has assaulted the nervous and skeletal systems.

I am a self-taught choreographer with training in dance, aerial dance and circus arts via Master Lu Yi at the SF Circus Center. I’ve spent twenty-six years transforming oral history into public art and ten years working with prison systems-impacted communities, including my own family. Through creative change, I am connecting systems-impacted individuals and organizations, reclaiming public space for women (including trans women) and enacting public dialogue about prison systems change.

The process

Our methodology begins with three Restorative Justice circles rooted in talking it out. They can be described as vicarious circles, because they do not contain individuals directly harmed by someone in the room.

The dancers and our composer are essential participants in the circles. After the circles are complete, I create a conceptual frame for the show, and the apparatus design follows the conceptual frame. From the concept design, composer MADlines writes the music and lyrics. The movement invention comes last as a response to the emotionality and narrative of the piece, the rhythms in the music, and what the apparatus allows the body to do. Movement invention is led by the dancers, with me directing and shaping their efforts from the ground. There is, as I direct from the Quad of the law school, targeted shouting, pointing and mimicking flight.

We arrive at our first circle. We are dancers, aerialists, a composer, a Restorative Justice facilitator and formerly incarcerated people. There are sandwiches. Turkey and bacon. Hummus and red pepper. Chocolate-covered almonds. Chocolate-covered coconut. Fancy lemonade with bubbles.

Some of the truths that we arrived with:

G is back in the world after thirty-five years in prison and has forty-five days to find a job and a place to live before he is kicked out of his halfway house.

-

B arrives home from his day of work at the homeless shelter and kisses his wife so sweetly. We can see them over Zoom.

B has kept circles before and embraces what they can bring to this project.

G is not shy about telling his story.

One of us brings positional complexity as someone who has been sexually assaulted and partnered with someone who has caused sexual harm. One of us has been teaching in the juvenile system for eight years but has never participated in an RJ circle herself.

One man talks about the moment he shifted from eleven to twelve years old. How he went from a cute boy to a man everyone is afraid of, including his own mother. How he was a runaway, and no one was there to catch him as the world’s dangerous stereotypes descended onto him. Diminished him.

One man talks of absent fathers. Of a mother from a generation that did not lead with support and insisted that everything that happens at home stays at home. He never once went to a basketball game as part of a team. He became prey to a predator and child sexual assault. He turned to the street and caused harm. He spoke eloquently and emotionally of the precious series of moments when someone who was there for him when he was a sensitive child could have made everything different.

One of us talks about wrangling with an abuser as a young person. About isolating into an abusive relationship. About felony convictions for the abusive partner, who then bought his way out of prison and returned to their college with an ankle monitor. About how she dropped out of college altogether in response—another system of abuser isolation. About how no one thought to support her in coming back to college. About how male privilege left her, a survivor, out in the cold.

One of us talks about the gift of being authentic among Black men. How rare it is. And when he comes back in another life, tonight’s authenticity is what he wants for and with his brothers, uncles and all the men in his family.

There are more stories. About children not believed. About children asked to become the adult caretaker as early as the third grade. About having a dream as a young Black child and giving up on it because there was no one around to nurture it. And about the self-inflicted harm of giving up on one’s best self and turning to the street. For a place to belong.

There is anger. There is “everyone talks about supporting Black women,” but no one actually does so. There are tears and a call for anger as precision, as fuel. Not as a weapon to harm. There is incredulity. Why don’t we have tracks laid down to intervene before harm becomes extreme? Why do we put our resources toward punishment instead of intervention?

One of us talks about moving forward and backward and forward again. About how God and nature, named by a person who is not religious, are calling him forward as part of his return from prison after three decades and only 100 days out from his time behind the walls. He brings out his wallet, and despite not having any scissors, he realizes it’s time to stop carrying around his prison ID. All of the pain and glory of survival bound up in that card must go now if he is to move toward his hope of owning his own business. He folds the ID four times, accordion style, so that it becomes unrecognizable. At the end of the night, he drops it purposefully into the recycling bin.

One of us is embarrassed. For being big and bold and taking up space with the injury that comes from being harmed. But then she retracts the embarrassment. Because she is learning her right to take up space.

One of us is tired of being in her own story. At first, she told no one about it, because in telling it, the experience becomes someone else’s burden too, and she didn’t want to do that to someone she loves.

We have so much to learn about our right to take up space, to be injured and to repair.

The facilitator’s question has rooted the circle in deep and agonizing stories. But it has also brought to light some of the pain we all carry. And light mends us. The circle has lifted us through its seamless container, drawn with care, equity and respect. As a group, we forgive, and we do not. We find repair, and we do not. We connect old wounds to newer wounds. We find useful terms for real accountability. We name survivor-centred demands. We commit to living free from creating victims. At the end of the circle, we rest. As a collective, we have moved and been moved.

Moving outward

From this initial circle, we move outward. We invite the public into a circle with us as they watch a small excerpt of performance material with two people who are formerly incarcerated. We then move across the country to New York and sit in a circle with the dancers, our composer and seven people who are currently and formerly incarcerated, mostly in Sing Sing. This was the first Zoom experience with the five men living at Sing Sing prison who met with us. Joseph Wilson and I co-designed and co-led the gathering. Joseph lives in Sing Sing prison and is the co-founder of the Sing Sing Family Collective. Maddy Clifford, the project’s composer and a published writer, led substantive content.

The gatherings to date reinforce my view that prisons don’t keep us safe, that they recreate the very trauma that leads to harm in the first place. Every week, I work with the women of Essie Justice Group. This work bolsters my knowledge that changing carceral systems is an act of intersectional feminism. It’s what Black women want. Prisons break you down and offer almost nothing to build you back up. Prisons perpetuate slave conditions for Black and Brown people at every level. If you have caused harm, you have to get to that moment of looking in the mirror and taking responsibility for the rest of your life, and that process requires cushioned support. At the same time and equally importantly, the criminal legal system as it functions right now does not offer a process of repair for people who have been accosted, violated or raped. And survivors are completely varied and individual in what we need.

Meeting with the five men from Sing Sing was a pivotal moment for me. I felt how much they valued being seen and heard as human beings. I felt the excitement of Hudson Link Director Sean Pica, whose work was leading this tiny group of a dozen people toward vital communication that really changes lives. I felt my own desire to speak about how secondary incarceration has and continues to injure my son and me. About how those scars breathe in my body still. They likely always will.

My belief in prison systems change grows with this process. It does not diminish. Working with Joseph Wilson is an act of rebellion against the complacency and exploitation of the prison industry. Accountability does not have to dehumanize.

The performance: experiments and risks

After a year of social process, we turn to the art. To engineering. The project is designed for public performance in proximity to prison systems. In San Francisco, we plan the premiere on the roof of a law school. Ironically, the law school is immersed in a reconciliation process with its own history of harm, and its name change to “San Francisco College of the Law” coincides with our performances on the building.

Because I want the project to tour, I work with our rigging team to create a set that can fit on an airplane. We nearly succeed with that goal, but the pandemic and shipping limitations make ground shipping more affordable for parts of the set.

The piece starts with a bucket and pouring water. Designer Sean Riley and I chose water as an element that a survivor of harm can use to control their environment. The project’s artists embraced how water can cleanse, but also cause damage. We pour water on the building to cleanse it before we dance on it. We drink water, and we end the piece by drenching a dancer in a cleansing bath. We tie see-through containers of water to a steel yoke, giving soloist MaryStarr Hope the opportunity to show audiences what balance can look like and how our prison systems are out of balance if one measures their efficacy for creating safety.

We also experiment with wheels. Until now, I have never designed a set that can roll on a building. For the set and the piece as a whole, I am working with the phrase “reimagining public safety.” I first heard it from Oakland activist Cat Brooks. It is now used widely among prison abolitionists. And so, Sean Riley and I create a set that is rooted in abstraction and aspiration. The large set pieces are abstract and unrecognizable as common objects like a chair or a door.

We dance with poles framed end-to-end by wheels. Poles that mark the space between inside and outside prison. Poles that mark what is most often a false binary between those who cause harm and those who have been harmed. Poles that can be tossed and flipped around, that bodies can be twisted onto, that roll when they are released so that dancers are free to leave and come back to them. There is a big learning curve in rehearsals as the participants learn to work in a tight quartet; to avoid landing on the poles after a double flip and breaking an ankle; to catch the dancers in the air at just the right moment of flight.

Aerialist Megan Lowe surpasses expectations with these poles. She brings vast kinetic intelligence to aerial performance, and her work on the project generates potent inquiry. She questions how to represent the voices of the incarcerated when she herself has been deeply scarred by violence and violation. She questions cross-racial representation as a biracial Asian/white dancer telling a part of the story rooted in American Blackness.

I bring her struggle to Joseph Wilson, our primary collaborator in Sing Sing. As a Black man in prison, he responds:

From a spectacular and flight-laden quartet, the piece quiets into an emotional final solo. This is a choreographic risk—to end the piece with a story that centres the harm of sexual violence. Soloist Alayna Stroud works with another pole on wheels rigged parallel to the ground. The pole is designed as both a circle within which she can find safety, and a horizontal pole she can throw like a javelin. Throw in anger. Throw to radically change her environment. When a group of high school students in New York sees the piece, they are captivated by the accompanying text: “If 60 percent of my body is made of water, how much spit will it take to rid my body of him?” I’m saddened that the world has already failed them, as they are already wrestling with sexual violation. But I am also glad that the project speaks to them without shame.Please tell our Asian friend that I respect and understand her position on the disconnect with the African-American experience. However, using the historical Asian-American experience as her guide, she may find similarities. After all, systematic harm is not foreign to Asian-Americans. Feelings of being othered, categorized, stigmatized, dismissed, subjugated and dominated by America’s culture propagated by the cisgendered, patriarchal, white male, White-body supremacy is living within her body too. She should dance it out. She should dance out Asian hate. She should dance out conformity to white culture. She should dance out of her skin tone. She should dance out of her barriers to the beauty standard. She should dance out of slurs and microaggressions. These harms and prisons we have in common.

Audience and critical response

Prisons are hard to hear about. We have tucked them away down long roads in the middle of nowhere so that regular people can just get on with their day without having to think about the consequences of mass incarceration, the three-strikes law, sentencing enhancements or the warehousing of mostly Black and Brown bodies. But those bodies are also everyday Americans. According to Essie Justice Group, one in four women and one in two Black women have an incarcerated loved one.3

I use spectacle to pull the viewer in. I try to make a lasting impression with an audience that centers uplift but also does not shy away from political difficulties. Led by the dancers’ invention, I try to blend elegance, the unexpected, sorrow and delight. In the performance, the rolling set pieces bring movement to a big concrete wall. They animate as they swing in a pendulum, and as the dancers match, they enhance and amplify that pendulum.

Audiences have questions. What can an artist bring to the question of prison reform? How do you train for a show like this? What’s the process? Does the music come before the movement? What do the costumes signify? Can art change anything?

What I can say most honestly about audiences who have seen the work is how hungry they are for stories told by people directly impacted by prison systems. Our shows in San Francisco (see the video link to Apparatus of Repair, 2022) were haunted by Bay Area winds, heat waves and cold waves, although thankfully, there was no wildfire smoke. In Ossining, New York, at Bethany Arts Community, a couple of miles from Sing Sing prison, audiences hovered in the cold nights of sold-out October outdoor seating. It was so dark you could not see in front of you. We have never, in twenty-three years of outdoor public art-making, performed in a place so dark at night, where no urban light pollution can cut into the magic of a real blackout and the emergence of the first light cue. When the lights came up and an aerialist loomed on a distant roof, a three-year-old in the audience asked his mom, “Is she real? And if she is real, what is she doing there?”

One formerly incarcerated man in San Francisco told me that if he had seen the piece before he was sent down, he probably would not have gone to prison. Someone else in New York, who had been released for just a few weeks, said that only someone who knows prison could have created this performance. As we are a collaborative group of artists, I accepted her compliment but extended its accuracy to the whole creative team. Some audiences travelled on trains for two or more hours to get to the show—this is true of one academic in New York who teaches prison systems change in her classes at Siena College and to everyday audiences in Marin County, California, who live in the countryside and drive to the city to be civically engaged.

San Francisco’s independent news and culture site 48 Hills describes Apparatus of Repair as an “Acrobatic Abolitionist Exegesis.”4 San Francisco Public Art Historian Annice Jacoby describes the performance as “A joy to behold! Apparatus of Repair is superb, as culture, as a pendulum of justice and display of defiance, defying injustice and gravity. A salute to your masterful grappling with the weight of pain, and the lightness of righteous energy to uplift and sustain the best of life. The work is magnificent, the talent muscular, buoyant and exhilarating, with a score of lament and beat of insistence.”5

Notes

- See Koch, Arthur. “San Francisco City Hall Public Comment on AB481, Police use of military equipement.11/11/2022.” YouTube, uploaded by Arthur Koch, 15 November 2022, www.youtube.com/watch?v=0Gt0nvE5SEQ [^]

- See Norris, Zach. (2021). Defund Fear: Safety Without Policing, Prisons, and Punishment. Beacon Press, 2021, pp. 93. [^]

- See Clayton, Gina, Endria Richardson, Lily Mandlin, and Brittany Farr. Because She’s Powerful: The Political Isolation and Resistance of Women with Incarcerated Loved Ones. Essie Justice Group, 2018. www.becauseshespowerful.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Essie-Justice-Group_Because-Shes-Powerful-Report.pdf [^]

- See Bieschke, Marke. “Arts Forecast: SF Fringe, Mill Valley Fall Arts Fest, Dark Side of the Circus … ” 48hills, 14 September 2022, 48hills.org/2022/09/arts-forecast-sf-fringe-mill-valley-fall-arts-dark-side-of-the-circus/ [^]

- Jacoby, Annice. Personal communication. 16 September 2022. [^]

References

Bieschke, Marke. “Arts Forecast: SF Fringe, Mill Valley Fall Arts Fest, Dark Side of the Circus …” 48hills, 14 September 2022, 48hills.org/2022/09/arts-forecast-sf-fringe-mill-valley-fall-arts-dark-side-of-the-circus/

Clayton, Gina, Endria Richardson, Lily Mandlin, and Brittany Farr. Because She’s Powerful: The Political Isolation and Resistance of Women with Incarcerated Loved Ones. Essie Justice Group, 2018. www.becauseshespowerful.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Essie-Justice-Group_Because-Shes-Powerful-Report.pdf

Koch, Arthur. “San Francisco City Hall Public Comment on AB481, Police use of military equipement.11/11/2022.” YouTube, uploaded by Arthur Koch, 15 November 2022, www.youtube.com/watch?v=0Gt0nvE5SEQ

Norris, Zach. Defund Fear: Safety Without Policing, Prisons, and Punishment. Beacon Press, 2021, pp. 93.

Thomson, Jess. “Massive, Strange White Structures Appear on Utah’s Great Salt Lake. Newsweek, 8 September 2022, www.newsweek.com/mysterious-mounds-great-salt-lake-utah-explained-mirabilite-1741151