1. Introduction

Anne Conway claims that there is divine justice in the progress of time: created beings, or creatures in her system, are appropriately rewarded and punished (CC 35; VI.7).1 It has not, however, been noticed that another of Conway’s commitments, that of divine emanative constant creation, is in tension with her temporal picture of moral responsibility. Conway writes that God’s “preservation or continuation of his creatures is a constant act of creation” (CC 33; VI.6). Conway’s constant creation picture includes a commitment to divine emanative causation, a reflection of her Platonist metaphysics well-articulated by Jacqueline Broad (2018), Sarah Hutton (2004; 2018), and Christia Mercer (2012a). Emanative causation has a significant atemporal aspect: God’s act coexists with its effects. Conway emphasizes that divine agency has “no succession or time in it,” with no past or future, before and after (CC 18; III.8). Causal relations are atemporal, not proceeding successively from before to after, or past to future. Moreover, Conway’s constant creation picture has it that all times are determined by the same divine causal contribution, an emanative one.

It is in the nature of creatures to have succession in motion (CC 14; II.6). Their actions have a successive structure that conflicts with the atemporal structure of emanative causation according to which a cause coexists with its effects. In other words, creaturely agency proceeds from before to after, or past to future, unlike emanative causation. So, it seems that creatures are not emanative causes. Conway’s claim that motion happens “only in subordination to God as his instrument” reinforces the impression that God is the only cause (CC 70; IX.9). Conway’s picture of divine justice in the progress of time suggests that creatures are causes and in turn morally responsible. Somehow, creatures must also be atemporal emanative causes despite their temporal nature.

I propose that this tension between Conway’s commitment to emanative constant creation and moral responsibility can be resolved with the resources of her metaphysics of time. Vital motion is a divinely given intrinsic power to do good, that is, an inner power to emanate perfection. Creatures have vital motion that enables their causal contributions to be simultaneous with its effects. Local motion, by contrast, belongs only to creatures and always has duration. Conway’s attribution of vital motion to creatures allows that an aspect of their agency transcends time and reflects their divine origin, in accordance with her overall Platonist metaphysics.

2. A Tension between Emanative Constant Creation and Moral Responsibility

Conway’s philosophical methodology is systematic, consisting mainly of a set of derivations of interesting results from assumptions about God’s nature. She writes that from careful reflection on divine attributes “the truth of everything can be made clear, as if from a treasure house stored with riches” (CC 44; VII.2). The assumptions about God are substantive, but they are often common ground between Conway and her intended interlocutors. Working through The Principles of the Most Ancient and Modern Philosophy is a delightful exercise in drawing out surprising consequences of commonplace divine attributes.

There are three kinds of beings or species in Conway’s system: God, Christ, and creatures.2 Species are individuated according to whether they change or not, and the kinds of change that are possible for them. God is immutable because he is absolutely perfect, Christ is partially mutable, changing only for the better, and creatures are fully mutable, able to change for the better or worse. Christ’s development is best understood as a monotonic progression, while creatures sometimes regress with respect to the good.

The relationship of each species to time requires some clarification. God is in time, but is not limited by time (CC 14; II.5). Emily Thomas explains Conway’s challenging remarks concerning God’s presence in time as a commitment to temporal holenmerism (2017: 998–1002). Holenmerism is a medieval approach to accounting for the relation of soul to body. Robert Pasnau explains it as the view that the soul is present in the body as a “whole in the whole” and a “whole in the parts” (2011: 296). For example, my soul is present in the whole of my body, and yet my soul is also wholly present in its parts, that is, my arm, my hand, my finger, and so on. Holenmerism is especially useful for understanding Conway’s account of immediate divine presence because it allows distinct ontological items to be co-located, as God is in nature but not identical to it.3 God’s spiritual presence in the world can be understood in terms of literal occupying of space or time, or a metaphorical presence by agency. That is, in the case of time, divine holenmeric presence is either a matter of divine agency’s effects in time or God’s location in time. Thomas argues that Conway endorses both divine holenmeric presence by causal determination and, perhaps more controversially, temporal location (2017: 999–1000). On the latter point, Thomas cites Conway’s claim that “God is really and intimately present in all times and does not change” (CC 51; VII.4). In sum, God is unchangingly located in all times and also causally determines them.

Creatures, by contrast, change with time. Conway identifies time with the transition from one state to another in creatures (CC 51; VII.4). Christ changes, and shares temporality with creatures, but like God he can never turn away from the good, as he can only improve (CC 24–25; V.3).4 Christ is a mediator because otherwise there would be a gap between two extremes, God’s absolute perfection and a creature’s imperfection (CC 25; V.3). God works with creatures via Christ, a point that we will return to in what follows (CC 25; V.4).

According to Conway’s system, with divine help, all creatures are eventually restored to a condition “not simply as good as that in which they were created, but better” (CC 42; VII.1). In other words, Conway is committed to universal salvation.5 Hutton writes that Conway may be unique among the Cambridge Platonists in grounding her account of salvation in her physics (1996: 121).

Increases in perfection bring with them, not necessarily immediately, increases in spiritual aspects of creatures. Decreases in perfection manifest in creatures, “at the appropriate time,” as increasingly crasser bodily characteristics (CC 42; VII.1). Spirit and body are not distinct substances or essences in creatures (CC 41; VII.1). Creatures are one kind of substance with spiritual and bodily aspects that change into one another. For instance, pain diminishes the crassness of the body, making it more subtle or spiritual (CC 43; VII.1). With this background in mind, we are ready to delve into Conway’s commitment to divine justice in the progress of time.

Divine justice is revealed alike in the progress and regress of creaturely development:

This justice appears as much in the ascent of creatures as in their descent, that is, when they change for better or worse. When they become better, this justice bestows a reward and prize for their good deeds. When they become worse, the same justice punishes them with fitting penalties according to the nature and degree of their transgression. (CC 35; VI.7)

Conway claims in this passage that it is a matter of justice that creatures receive punishment for regress and reward for progress. As they ascend, they become more spiritual, and as they descend, they become more bodily. That leads us directly to her doctrine of transmutation.

Conway has a thoroughly egalitarian metaphysics. Any being can progress, via incremental changes, up the hierarchy of being and increase to higher levels of perfection (CC 32–33; VI.6). A rock can become a plant, eventually turn into a non-human animal, human, and angel, all while remaining the same individual.

Conway’s argument for transmutation rests on divine power, goodness, and wisdom (CC 32; VI.6). God knows that creatures must be able to develop beyond the limitations of their species if they are to achieve higher levels of perfection. Equally, one’s outer constitution should match their inner life. Brutality in humans lends itself to a descent to a brutish form (CC 36; VI.7).6 For Conway, divine punishment is a natural aspect of change, not a product of “final judgment.” Marcy Lascano notes that changes of outer material form are a spontaneous consequence of changes in perfection (2013: 331).

Divine punishment for sin also involves suffering as well as “chastisement” through which “evil turns back again to good” (CC 42; VII.1). The latter is an aspect of her account of universal salvation, as any pain or torment is ultimately redemptive. Conway’s reference to chastisement indicates a commitment to a robust concept of moral responsibility because not only is punishment and reward merited, but sometimes attitudes of disapprobation can be justified. Indeed, she allows for the appropriateness of praise and blame (CC 58; VIII.2). Conway’s position on moral responsibility has further complexities that we will return to in the penultimate section. Still, we have enough to understand that Conway has a deep commitment to moral responsibility.

The second half of our puzzle concerns Conway’s doctrine of emanative constant creation. Conway’s commitment to emanation causation is part of her Platonist metaphysics. Christia Mercer describes early modern Platonist metaphysics, hereafter Neoplatonism, as a picture according to which God emanates unity, goodness, and power to creation (2012a: 112–13). Mercer writes that Neoplatonist metaphysics has it that souls “receive power from God, and act by emanating it” (2012a: 113). Conway explicitly describes her position as an emanative picture.

Consider a paradigm passage of Neoplatonist reasoning in Conway:

For God is infinitely good, loving, and bountiful; indeed, he is goodness and charity itself, the infinite fountain and ocean of goodness, charity, and bounty. In what way is it possible for that fountain not to flow perpetually and to send forth living waters? For will not that ocean overflow in its perpetual emanation and continual flux for the production of creatures? For the goodness of God is communicated and multiplied by its own nature, since in himself he lacks nothing nor can anything be added to him because of his absolute fullness and his remarkable and mighty abundance. (CC 13; II.4)

Conway claims that God’s goodness is an active emanation of his communicable perfections for the benefit of creatures. The active nature of divine goodness is a key point that we will return to in the next section.

Further, Conway has an emanative constant creation picture. She claims that the “preservation or continuation of his creatures is a constant act of creation,” a result that she claims to have demonstrated in the preceding text (CC 33; VI.6). Conway’s argument for that result is less evident than her case that God’s creation is necessitated but free. Implicit arguments that preservation is constant creation can, nevertheless, be derived from Conway’s explicit remarks.

From the claim that “God was always a creator and will always be a creator because otherwise he would change,” Conway concludes that death is not a departure but a return in a different form (CC 13; II.5). If God were to cease creating beings or fail to continue to preserve their being, he would change, which would be in conflict with his divine immutability. So, creatures exist in various forms across infinite times. The same line of reasoning supports her claim that preservation is mere constant creation.7 God does not create a creature and then merely preserve its existence. Otherwise, his action would change in conflict with divine immutability.

Relatedly, Conway describes God’s operations as a single action:

Moreover this continual action or operation of God, insofar as it is in him, proceeds from him, or insofar as it refers to himself, is only one continual action or command of his will; it has no succession or time in it, no before or after, but is always simultaneously present to God so that nothing is past or future because he has no parts. (CC 18; III.8)

Conway emphasizes that God’s activity in creation and preservation is “only one” continuous action. Herein lies another implicit rationale for Conway’s constant creation picture: God’s act of preservation does not differ from that of creation because he has only one act of will. Moreover, it is critical to note Conway’s description of the atemporal nature of God’s causal contribution: God’s action is wholly present without succession, before and after, past or future.

Jacqueline Broad notes an atemporal aspect of the Neoplatonist emanative, influx model: “the motion brought about by the influx is coexistent with the motion of God” (2018: 589). Conway’s position is similar, as the prior passage suggests, and we will confirm shortly. But our comparison requires a qualification. God lacks motion because “all motion is successive and can have no place in God” (CC 18; III.8).8 God is an unmoved “first mover of all his creatures” (CC 18; III.8).9

Conway offers some examples to aid the imagination and understanding of how a motionless, unchanging ground gives rise to temporal succession:

Suppose a great circle or wheel to move about its center, which always remains still in that one place. In the same way, the sun is moved around its center by some angel or spirit who is in its center, within the space of so many days. Now, although the center moves the whole and produces a great and continual motion, it nevertheless remains always still and is not moved in any way. (CC 18; III.8)

Conway offers an analogy to the relation between the motion of a wheel and its fixed center, presumably a point. She also uses the example of the sun turning around its unchanging center, perhaps an axis. Overall, these images reflect an atemporal aspect of emanative causation.

God’s immutable will is the correlate of the unchanging, center point of the wheel, while succession in creatures is the correlate of the spokes or the outer rim of the wheel that change their spatial relations. The center of the wheel and the sun, whether a point or a line, is a static fulcrum on which motion depends just like motion depends on an unchanging divine ground. Conway’s analogies reflect Broad’s point that an emanative cause coexists with its effect. For instance, the center of the wheel coexists with every part and movement of the wheel and remains unchanging in its relation to those parts and motion throughout. With that final piece, we can make our temporal puzzle more precise.

Conway’s constant creation picture has it that God continuously emanates his attributes to creatures in a single act that grounds the entirety of the stages of the world’s history. And creaturely agency is grounded in God’s power on Conway’s Neoplatonist framework: creatures are assumed to act via emanation of God’s power. Crucially, God’s emanation coexists with its effects, rather than proceeding from before to after, or past to future. Creatures are essentially temporal so that they change with time, changes for which they are either rewarded or punished via immanent divine justice. Creaturely agency has a successive temporal structure that is incongruent with the atemporal structure of emanative causation. Simply put, the temporal structure of creaturely agency apparently precludes their being emanative causes and in turn morally responsible.

It is not a mere commitment to constant creation that raises the puzzle. Philip Quinn (1988) argues that even with constant creation, created beings can count as causes under Humean constant conjunction accounts, counterfactual approaches, or necessitarian theory. So, there is no conflict.

Quinn’s argumentative strategy is instructive--define first what is meant by “cause” before deciding whether created beings count as causes. Creatures may also be seen as causes under those accounts of causation. Our issue is more specific: it concerns an apparent conflict between the atemporal structure of emanative causation and the successive structure of creaturely agency. Likewise, we seek a resolution that shows how creatures can be emanative causes.

Conway’s metaphysics has resources to resolve the apparent conflict. Our temporal puzzle can be resolved by appeal to Conway’s distinction between vital motion and local motion. Vital motion enables creaturely agency to transcend time, modeling the atemporal features of emanative causation, or so I will suggest.

3. Conway on Vital and Local Motion

The interpretative suggestion developed in this section is aimed at removing a prima facie obstacle, presented by Conway’s emanative constant creation picture, to her commitment to moral responsibility. The solution to this puzzle lies in Conway’s attribution of vital motion to matter. This proposal is not intended to provide a comprehensive account of moral responsibility in Conway or cover all of the relevant problems. Julia Borcherding notes, for instance, that Conway’s position that creatures are a multiplicity of spirits raises a difficulty concerning how creatures can be unified enough to provide a proper subject for moral responsibility (2019: 137). The following interpretative proposal is only intended to address an aspect of the issues for moral responsibility.

Conway’s metaphysics of matter and spirit is a keystone of her system, as is evident from the long title of her work: The Principles of the Most Ancient and Modern Philosophy concerning God, Christ and Creation, that is, concerning the Nature of Spirit and Matter, thanks to which all the Problems can be resolved which could not be resolved by Scholastic Philosophy nor by Modern Philosophy in general, whether Cartesian, Hobbesian, or Spinozian. To understand her metaphysics of matter and spirit, it is helpful to begin by considering an interpretative point that is still in dispute, before turning to subtle issues concerning life.

Conway is a monist about the created world: creatures are a single kind of substance.10 She rejects Descartes’s dualism that posits spiritual and bodily substances with distinct essences. Some interpret Conway’s alternative as a commitment to an immaterialist, or spiritualist, monism that reduces body to spirit.11 Jacqueline Broad argues for a non-reductive interpretation: Conway’s system posits creatures with a principle of life whose essence is to change both their spiritual and bodily modes, neither of which is reducible to the other (2003: 66–67, 80). Both reductive-spiritualist and non-reductive approaches find support in the text.12 Though they disagree over whether matter is ultimately reducible to spirit, the crucial point is that both approaches agree that all creatures have a necessary principle of life and spirit, a central aspect of Conway’s vitalism.

Conway often connects life with spirit. The closest Conway comes to offering a definition of life appears in a passage where she characterizes life in terms of God’s communicable attributes, that is, spirit, light, goodness, holiness, justice, and wisdom (CC 45; VII.2). Incommunicable attributes are divine qualities that cannot be shared by creatures: independence, immutability, absolute infinity, and complete perfection. She claims further that all divine attributes, both communicable and incommunicable, are “alive” and “life itself” (CC 45; VII.2). Life is not one thing, but a multiplicity.

Those key passages suggest that Conway’s attribution of life to matter is the claim that all matter manifests some of God’s perfections. That position is reflected in Conway’s critique of “dead matter.” God is pure spirit, not at all material (CC 42; VII.1). Conway claims that bare material existence, that is, mere extension in length, breadth, depth, impenetrability, and motion, is precluded by the requirement that existence reflects divine attributes (CC 45–46; VII.2). In other words, nothing is merely material because all of existence has some aspect of divinity.

A crucial corollary to that argument attributes an internal principle of motion to matter:

Since dead matter does not share any of the communicable attributes of God, one must then conclude that dead matter is completely non-being, a vain fiction and Chimera, and an impossible thing. … Furthermore, since one cannot say how dead matter shares in divine goodness in the least, one has even less chance of showing how it is capable of reason and able to acquire greater goodness to infinity, which is the nature of all creatures since they grow and progress infinitely toward greater perfection, as shown above. (CC 45–46; VII.2)

Conway writes that dead matter is impossible because it lacks any of God’s communicable attributes and draws out the consequence that dead matter is incapable of improvement, that is, not able “to acquire greater goodness to infinity.”

Matter is living in virtue of participating in divine perfection, and it also has an intrinsic power to emanate and progress in its level of perfection to achieve a higher degree of life. Conway defends that latter point earlier in the text by appeal to divine attributes. Divine goodness, power, and wisdom dictates that God creates intrinsically good creatures so that they have an inner power for improvement (CC 32; VI.6). That enables “greater participation in divine goodness” (CC 32; VI.5). Moreover, the “highest excellence” of creatures is an unbounded, infinite approach towards ever higher levels of perfection (CC 33; VI.6). We have now uncovered a second crucial aspect of Conway’s account of living matter: vital motion.

To clarify, God is entirely immaterial but also has vital motion. God’s vital motion is aimed only at grounding progress in creatures, as he is incapable of improvement (CC 24; V.3). This position is nascent in Conway’s distinctly active conception of divine goodness. Conway likens God’s infinite goodness to a fountain that continually sends “forth living waters” to creatures, whereby divine perfections are “communicated” and “multiplied” (CC 13; II.4). God’s infinite goodness grants creatures an intrinsic power to attain higher degrees of perfection or life.

Conway’s vitalist position resembles, in some respects, that of her physician Francis Mercury van Helmont and an early view of her mentor Henry More. Carolyn Merchant observes that van Helmont maintained a monistic picture according to which bodies have an internal principle of change and the position that spirit and body can turn into one another by degrees (1979: 173). Conway’s account of vital motion includes an internal principle of change, which is oriented towards the good of creatures. Their development in perfection is spontaneously reflected in transmutation from degrees of materiality to spirituality or vice versa. Jasper Reid (2018) argues that More’s early position in his philosophical poems presents a vitalist account of matter in terms of an inner principle of change, a position that is superseded by More’s dualistic approach in the mid 1670s.13

The following passage further confirms Conway’s commitment to an inner principle of motion:

In a stricter sense, [vital] motion is proper to a creature because it proceeds from its inner being. It is consequently called internal motion to distinguish it from external motion, which comes from something else and can in this respect be called foreign. When this external motion tries to move a body or some other thing to a place where it has no natural inclination, this motion is violent and unnatural, as when a stone is thrown up into the air, which unnatural and violent motion is clearly local and mechanical and in no way vital, because it does not proceed from the life of the thing so moved. But every motion which proceeds from the proper life and will of a creature is vital, and I call this the motion of life, which clearly is neither local nor mechanical like the other kind but has in itself life and vital power. (CC 69; IX.9)

Conway writes here that vital motion is precisely the kind of agency that proceeds from an inner rather than outer cause. External motion as a change imposed on a creature from without, rather than from within, comprises only local or mechanical motion. Throwing a rock upwards, for instance, goes against its natural tendency, perhaps to move toward the center of the earth.

Conway’s account of vital motion in the above passage attributes a power to creatures of causing their motion. Crucially, they can only do so with God’s help, so that God’s vital motion exists for the purpose of grounding motion in creatures. We will return to that point, but to foreshadow, I will argue that Conway has a concurrentist picture.

Vital motion proceeds from the agent’s life and will, while motion that is only caused by something external is mere local motion. Local motion is an instrument of vital motion, at least when it affects other creatures (CC 66; IX.6). In some cases, local motion is combined with vital motion. When motion is fully determined by external causes, it is mere local motion without vital motion, for example, a rock being thrown upwards. As a creature increases in its ability to emanate perfection via vital motion, it also attains a “more noble kind or degree of life” (CC 69; IX.9). In sum, vital motion enables creatures to increase in their degree of perfection or life.

The role of vital motion in enabling attainment of greater degrees of perfection is reflected in Conway’s critique that Descartes and Hobbes’s view of matter omits the most “noble attribute” of substance:

If anyone asks what are these more excellent attributes, I reply that they are the following: spirit or life and light, by which I mean the capacity for every kind of feeling, perception, or knowledge, even love, all power and virtue, joy and fruition. … But this capacity to acquire the above mentioned perfections is an altogether different attribute from life and perception, and these are altogether different from extension and figure; thus vital action is clearly different from local or mechanical motion, although not separate or separable from it, inasmuch as it always uses this motion as its instrument, at least in all its dealings with other creatures. (CC 66; IX.6)

Conway claims in this passage that spirit or life and light are neglected in the identification of matter with extension and impenetrability. She writes that spirit or life and light are the capacity for perfections of cognition, virtue, love, and the like. The capacity to actually acquire those perfections via vital action is “an altogether different attribute” from life, perception, and in turn distinct from extension and figure. This requires further explanation.

First, Conway’s claim that the capacity to acquire perfections through vital motion is a distinct attribute from life can be explained by the interpretation developed thus far. Recall that Conway identifies life with divine attributes, both communicable and incommunicable. Vital action concerns a divinely given power to progress in communicable attributes and hence, should not be conflated with life. Life includes incommunicable attributes, presenting a limit on the degree of life that creatures can achieve.

Second, her claim that extension and figure is distinct from life, perception, and vital motion, is the claim that the latter is irreducible to the former.14 Conway identifies, for example, visual perception as a process distinct from mechanical or local motion, as change of place (CC 67; IX.9). Local motion is an instrument of vital motion. Conway maintains that the eye cannot see without light, and light triggers the vital motion of sight in the eye. Not only do the eyes receive light that triggers this vital motion of sight, but also Conway claims that vital motion travels to the external object of vision (CC 67; IX.9). Perception requires local motion, but is not reducible to size, shape, length, breadth, and depth.15 Local and vital motion have a differential structure.

A key passage suggests that vital motion, unlike local motion, can occur at an instant:

And if it [vital motion] can penetrate the bodies through which it passes by means of its intimate presence, then it may be transmitted from one body to another in a single moment, in fact, in no time at all. I mean that the motion or action itself does not require the least time for transmission, although it is impossible that a body in which the motion is carried from place to place [local motion] should not take some time … (CC 69; IX.9)

Conway tells us in this passage that vital motion can be transmitted in an instant, even though the local motion required to realize this motion always has a duration.16 Local motion has an intrinsically successive structure, whereas vital motion has an atemporal structure.

Thus, vital motion appears to be an aspect of creaturely agency that models the requisite atemporal structure of emanative causation. Vital power can be transmitted at an instant so that it is simultaneous with its effect, which implies that a creature’s vital power coexists with its effect. Vital action need not proceed from before to after, or past to future, as local motion does.

My suggested atemporal interpretation of vital motion also fits well with another intriguing passage:

Thus we see how every motion and action, considered in the abstract, has a marvelous subtlety or spirituality in itself beyond all created substances whatsoever, such that neither time nor place can limit them. (CC 69; IX.9)

Conway claims that an aspect of creaturely agency is unlimited by time. My interpretation of vital motion, which has it that vital power is simultaneous with its effects, accommodates that. For an example of how vital action is not limited by space, Conway claims that love emanates so that lovers are present to one another even over long distances (CC 53; VII.4). A picture has thus emerged according to which creaturely agency resembles its divine origin.

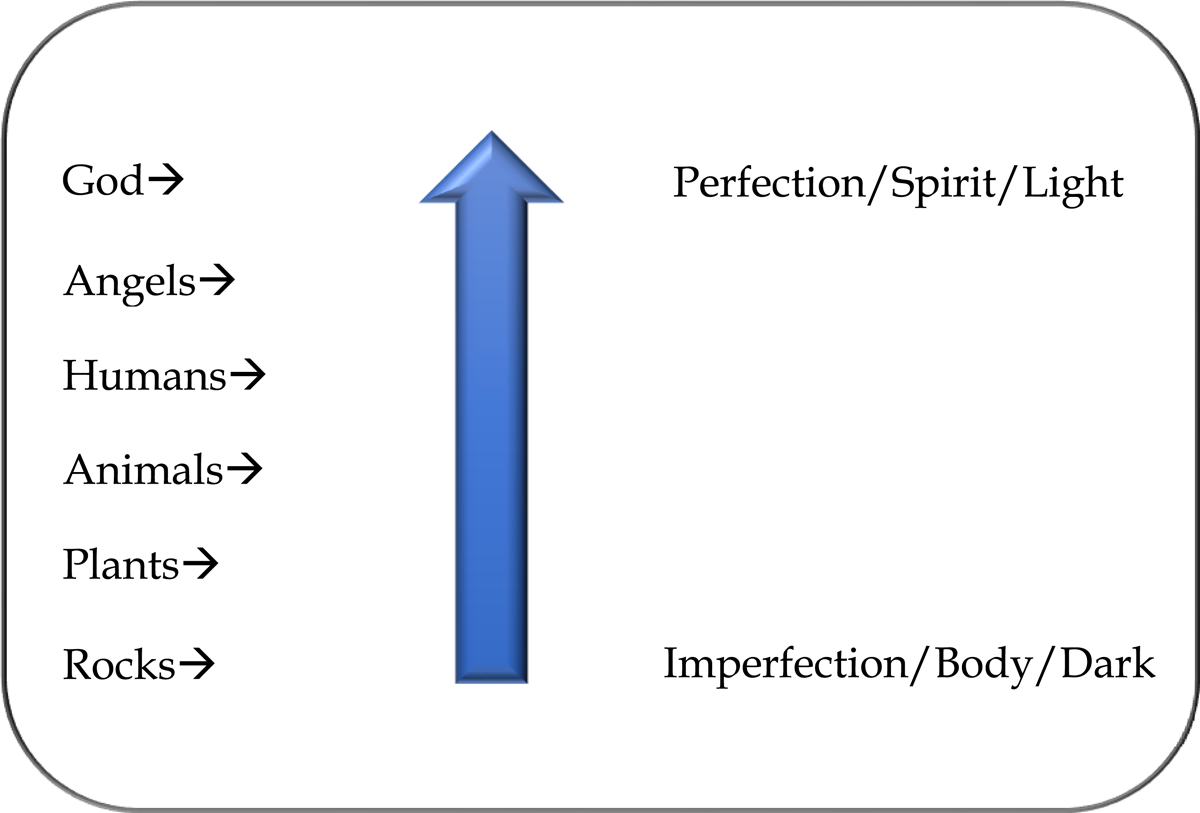

That result is precisely what we would expect, given her Neoplatonist picture, which can be illustrated in a diagram:

Creation is on a continuum with divinity so that the power through which creatures act is God’s power. Furthermore, divinely given vital motion enables them to progress up the hierarchy of being, which has a lower bound because nothing is infinitely a body or evil (CC 42; VII.1). There is no limit to goodness as God is infinitely good, though divine perfection serves as an upper bound so that creatures can only infinitely approach higher degrees of life.17 Conway uses metaphors of darkness and light to explain body and spirit, respectively (CC 38; VI.11). With the overall metaphysics in mind, we can explain how creatures are also causes.

Recall that the problem with emanative constant creation is that God’s causal agency does not proceed from before to after or past to future (CC 18; III.8). Causation is timeless, but creaturely agency has a temporal structure. Conway writes that God would never accelerate creaturely development so that it happened at an instant, even though he could, because then creatures would not be able to attain “through their own efforts, ever greater perfection” (CC 66; IX.6). How do we reconcile the temporal structure of creaturely agency with the atemporal nature of emanation causation so that creatures can also count as causes? Our resolution lies in the fact that local motion always proceeds successively as an instrument of vital motion, which in turn can be transmitted at an instant, as an emanative cause.

Whenever local motion is grounded in creatures’ vital motion, they count as emanative causes of their actions, even if local motion unfolds over time. In other words, creatures count as causes of their actions when it follows from the life and will of a creature, which Conway describes as a vital power and in turn vital action. To avoid misunderstanding, it should be noted that creatures are only partial causes of their actions.

Alfred Freddoso (1991) identifies mere conservationism, concurrentism, and occasionalism as three main medieval accounts of the status of created beings as potential causes beyond God, and these positions were influential in the early modern period. Conway is best described as a concurrentist: the position that all creaturely activity is a product of causal coordination between God and creatures. Concurrentism contrasts with occasionalism because it admits causal agency to created beings, as partial causes of their actions. Occasionalism has it that God is the only cause. Further, it contrasts with mere conservationism as the position that creatures can cause things on their own without God’s immediate intervention.

A mere conservationist interpretation is not well supported by the text. First, Conway speaks of God and creatures requiring a union through Christ so that they can work together (CC 25; V.4). Conway’s appeal to shared agency suggests that creatures cannot supply the requisite causal agency on their own, in opposition to a mere conservationist position. Second, recall that Conway claims that creatures only cause motion as God’s instrument (CC 70; IX.9). Thus, they cannot cause motion on their own, contrary to a mere conservationist interpretation.

Rather than taking an occasionalist interpretation of Conway’s remarks on creatures as “instruments,” we can understand it as a commitment to a concurrentist position. God gives creatures the power to emanate communicable divine perfections and to that extent they are “instruments of divine wisdom, goodness, and power, which operate in them and with them” (CC 66; IX.6). God emanates his communicable perfections via vital motion so that creatures can transmit his perfections. Conway is best described as maintaining a concurrentist picture, as God and creatures make joint causal contributions.

That proposal in turn raises other problems. I emphasized throughout how vital motion is a divinely given power to emanate perfections that ultimately tends to a creature’s good and improvement. Vital motion is a universal feature of all of creation. Nevertheless, how can we make sense of a power to do good in rocks, such that God concurs even with their actions? Does that mean we should hold rocks accountable? Also, I have focused on how God helps creatures to progress via vital motion, but we must also consider changes for the worse.

Creatures can use their vital motion, though intrinsically good, to change from bad to good as well as good to bad (CC 24; V.3). Creaturely development is imperfect. In addition, vital motion is received immediately from God (CC 69; IX.9). Does God then concur with sin via vital motion? Conway would reject the idea that God is causally responsible for sin. The next, penultimate section will address the problem of concurrence with evil along with the issue of how to make sense of divine concurrence with “good” actions in beings with minimal capacities for agency.

4. Replies to Objections

It strains credulity that even grains of sand have a divinely given power to do good. In addition, for changes for the worse, God’s concurrence with them appears to make him responsible for evil. Conway denies that. We will begin with the issue concerning the universality of the power to do good.

The problem stems from a particularly moral conception of goodness. So, saying that all creatures, even rocks, have a power to do good via vital motion suggests that we can hold rocks accountable, should blame them, etc. That is implausible: a rock is unaffected by praise or blame and incapable of changing behavior in response. Therein also lies our solution. The goodness that all creatures have and emanate is not moral.

Sarah Hutton (2018) argues that Conway endorses a Neoplatonist account of goodness as acting according to one’s nature and in turn similarity to God. Hutton’s insight is that perfection is primarily a metaphysical concept in Conway, though it does not exclude the existence of specifically moral goodness. The perfection that all of creation shares is a matter of similarity to God and acting in accordance with nature. Hutton’s proposal works even for the most difficult type of case: substances, like rocks, that seem to lack agency in any meaningful sense.

Though Hutton does not explicitly connect her interpretation with Conway’s account of vital motion, it dovetails with it. Recall that, for Conway, vital motion stems from the life and will of a creature. Creatures have vital power from God and, as Hutton’s interpretation predicts, it is “a proper consequence of its essence” and thus, vital motion follows from their nature (CC 69; IX.9). Conway’s example of local motion without vital motion is the case of a rock being thrown upward against its “natural inclination.” A rock’s natural tendency may be to move towards the center of the earth or perhaps to remain at rest, either of which may be what Conway has in mind when she speaks of a rock’s natural inclination. Either of those states might be said to follow from its essence or nature, and to that extent may qualify as a case of vital motion. Further, when the rock acts according to its nature, it is not determined by anything outside itself and, hence, is more similar to God. The hierarchy of being reflects stages in a creature’s development of higher levels of self-determination and resemblance to God.

With that, we have the resources to address the first concern. The sense in which rocks have a power to do good merits no blame when they fail or praise when they succeed. Shortly, we will see that, for Conway, those attitudes can be appropriately directed towards beings with higher levels of cognition. The initial air of implausibility derives from conceiving of goodness in a primarily moral sense. The universal goodness of creatures is not moral. A power to do good is a matter of emanating communicable perfections via vital motion. Equivalently, vital action is a matter of acting according to nature, a power that stems from a creature’s life and will. Rocks have vital power to a very limited degree, but they have it nonetheless. When viewed in light of her metaphysics of perfection, her universal attribution of vital motion is reasonable.

Our puzzle raised at the outset of the paper specifically concerns moral responsibility. We require a further understanding of the complexities of her view before addressing the problem of sin. Conway maintains that all creatures were originally a species of human beings identified according to their virtues (CC 31; VI.4). She also speaks of their having “fallen” and “degenerated” from an original goodness (CC 42; VII.1). At the outset, all creatures were human beings, and the complete hierarchy of creatures from rocks, to plants, to animals, to human beings, to angels stems from that decline. In other words, material form reflects changes in inner perfection so that the “fall” spontaneously generates that continuum.

Conway describes moral goodness in terms of reason: a good man is “able to give a suitable explanation for what he does or will do because he understands that true goodness and wisdom require that he do so” (CC 15–16; III.1). For Conway, morally responsible agents are rational or reasons-responsive, capable of acting for reasons of truth and goodness. The position that reason is a critical stage in the development of creatures is evident from her critique of dead matter. Conway stresses a difficulty concerning how dead matter can be capable of reason and able to infinitely acquire greater perfection (CC 46; VII.2). Acting for reasons requires sophisticated cognition that rocks lack, though they can develop those capacities via transmutation over long periods of time (CC 66; IX.6). In other words, rocks have purely metaphysical perfection and imperfection without moral responsibility, though they can develop moral responsibility by progressing up the hierarchy of being. With that background in mind, we will address the second objection.

The second objection is that insofar as God concurs in all creaturely actions, he also concurs with changes for the worse, suggesting that God is responsible for evil. We require an answer to the objection that shows how God is not responsible for evil. Given the distinctions that we have set up in the course of answering the first objection, we can divide the problem into two kinds of cases: non-moral or purely metaphysical evil and moral evil or sin.

God’s concurrence with non-moral evil, or purely metaphysical imperfection, raises no special problem in her system. God’s causal contribution provides a creature’s power of motion, but the creature also makes a necessary casual contribution. A creature’s ability to emanate perfections via vital motion is a function of its capacity for self-determination, so that it can act via internal rather than external causes. Conway assumes that creatures are not fully independent, as that is an incommunicable attribute (CC 45; VII.2). Outside forces can determine them and diminish their power for vital action, like Conway’s example of throwing a rock upwards. Moreover, Conway’s system has an implicit rationale for the existence of metaphysical imperfection. She argues that God’s creation is necessary (CC 16; III.2–3). Recall that his goodness must “overflow,” and he cannot multiply himself or improve himself (CC 13; II.4). Thus, God only creates metaphysically imperfect, limited beings. Moral evil raises additional issues that require further consideration.

Conway claims that even though all motion comes from God, God is not the cause of sin. Instead, sin is a result of misusing our divinely given powers for good, a point she illustrates with the following example:

If, for example, a ship is moved by wind but is steered by a helmsman so that it goes from this or that place, then the helmsman is neither the author nor cause of the wind; but the wind blowing, he makes either a good or bad use of it. When he guides the ship to its destination, he is praised, but when he grounds it on the shoals and suffers shipwreck, then he is blamed and deemed worthy of punishment. (CC 58; VIII.2)

In the above passage, Conway depicts agency as requiring materials to act upon just as the helmsman requires wind to sail the boat. The helmsman is not responsible for the wind, but only for the way he makes use of the wind. Given his choices, he is praised or blamed for the result.

God is responsible for the existence of motion, while the helmsman is responsible for how the ship is directed via vital motion. God continually creates the vital powers through which creatures choose to direct that motion. As suggested in the last section, a creature’s actions are always a joint product of efforts by God and creatures. Without the contribution of creatures, the propagation of motion is indeterminate. Altogether, God constantly creates creatures with an intrinsically good power of vital motion and provides the circumstances in which they determine motion and the power to do so.

Divine agency is never an external cause. God is internal to everything in Conway’s system: Conway maintains that through Christ’s mediation “he [God] is immediately present in all things and immediately fills all things” (CC 25; V.4). On Conway’s view, a creature can receive motion or action immediately either from God via Christ or other creatures.18 A creature’s action is due to a foreign cause when they are determined contrary to what follows from their nature by another creature’s action (CC 69; IX.9). Actions that are not coerced in this way follow from a creature’s vital motion. For example, as long as the captain’s direction of the ship is not determined against their will by another sailor, they are responsible for the result.

Crucially, a creature’s causal contribution resembles divine action, but it is not an act of creation. Conway writes that “it is solely the function of God and Christ alone to give being to things” (CC 48; VII.3). The direction of motion is not an act of creation that gives rise to a distinct being. Motion is a mode rather than a substance (CC 68; IX.9). Modes do not introduce distinct beings or substances, but distinct qualities of a single substance (CC 10; I.7). With God’s help, creatures determine modes of motion (CC 70; IX.9). Creatures lower down on the hierarchy of being, such as rocks, make causal contributions that are not driven by high-level cognition. For instance, facts about the features of their bodies and relative forces will determine how motion is communicated (CC 69; IX.9). Rational creatures, by contrast, can also affect how motion is communicated via their capacity for choice. Sin is a matter of abusing an intrinsically good power of vital motion by choosing for bad reasons. Only creatures with reason can sin.

Conway explains “corruptibility” and the moral evil of a tyrant by appeal to indifference (CC 15; III.1). For Conway, indifference is not a matter of equipoise, but a power to act or not act. Marcy Lascano (2017) and Jonathan Head (2019) observe that this is a central difference between God and creatures: God’s freedom is never indifferent, but always necessitated by truth and goodness. God always acts for the best and hence, supports a creature’s vital motion, an intrinsic good. But rational agents can use their intrinsically good powers for ill: they can choose, independent of external causes, contrary to truth and goodness. The transmission of motion in cases of moral responsibility depends, in part, on a creature’s decisions.

With that, it is clear that divine concurrence with moral evil does not make God responsible for evil. God constantly creates the intrinsically good vital motions of creatures, which in the limit tends to their restoration. Indeed, without a creature’s causal contribution, there would be no moral evil. Creatures bear final responsibility for sin due to their indifference.

A fuller picture of Conway’s position has emerged from critical evaluation. Perfection manifests as a continuum in nature. Rocks emanate perfections and act according to their nature, limited as it is. They lack high-level cognition, but they contain the seeds of their future moral development. Through long periods of time and transmutation all beings eventually attain reason and become subjects of moral responsibility and capable of specifically moral perfection and imperfection. For beings on the low end of the hierarchy, imperfection is initially only a result of their natural and necessary limitations. Later, they become capable of moral imperfection as a consequence of choosing to abuse their vital power for good, for which they bear responsibility.

Conway’s system is rich enough to account for creaturely causation and has resources to respond to some natural objections. We have shown that creatures can be causally responsible, as a necessary condition for moral responsibility. It is common, however, to think that freedom is also a necessary condition for moral responsibility. Conway’s position on freedom is complex, and we have only briefly remarked upon it in the preceding discussion. We will close with some brief remarks on an implication of the proposed atemporal interpretation of vital motion for issues of determinism.

Sarah Hutton claims that, for Conway, the created world is not deterministic (2018: 239). One option for understanding the variety of indeterminism that Hutton has in mind may be as follows: creatures with indifference are not necessitated in the sense that they have a power to do otherwise. That in turn is a natural fit for the view that freedom requires alternative possibilities. Without excluding that approach, I will highlight another kind of indeterminism that is supported by the proposed atemporal interpretation of vital motion.

Eleonore Stump highlights an indeterminist position that “the past does not determine a unique future” (1999: 321). Stump’s variety of indeterminism is reflected in the preceding approach to understanding vital action: a creature’s vital power is transmitted at an instant, undetermined by prior states of time. In vital action, creaturely agency resembles the divine in that it does not proceed from past to future or before to after. Stump pairs the preceding kind of indeterminism with an “ultimate causal responsibility” account of the freedom required for moral responsibility.19 An agent is free when their choices are ultimately up to them, rather than, say, being determined by the prior state of affairs. Indeed, Conway has the resources to account for creatures as emanative causes so that their successes and failures can ultimately be due to their own efforts.

5. Conclusion

Initially, it seemed that only divine agency could fit the atemporal structure of emanative causation that Conway endorses. God’s act of will is single and coexists with its effects, namely all temporal succession. Creaturely agency proceeds in time from before to after and past to future, but an aspect of their agency models the structure of emanation causation. Vital motion can be transmitted at an instant, even though local motion qua instrument always has duration. Creatures can causally determine modes of motion via emanation of vital motion. For Conway, not all emanative vital acts concern specifically moral agency, as that requires reason. All creatures can emanate divine metaphysical perfection, but rational creatures can also emanate higher perfections of cognition and distinctively moral perfection. Rational creatures can choose to use their intrinsically good vital motion either in accordance with God’s commands or not. Recalling Conway’s metaphor of the helmsman, creatures are not responsible for the existence of motion, but they can be responsible for whether they make good or bad use of it via vital motion.

Acknowledgements

This paper benefited from extensive comments from two anonymous Ergo referees as well as John Grey. In addition, I developed this paper with helpful feedback from colleagues at Grand Valley State University and participants at the 2019 meeting of The Central States Philosophical Association Meeting and Michigan State University’s History of Philosophy Circle. Finally, I thank Krista Benson, David Crane, Andrew Knoll, and Sue Sample for their valuable feedback and support.

Notes

- All citations are from Allison P. Coudert and Taylor Corse’s 1996 Cambridge edition translation of The Principles of the Most Ancient and Modern Philosophy, cited parenthetically according to page number, chapter, and section. ⮭

- There is interpretative debate over whether these three species are really one substance in Conway’s system. See Jessica Gordon-Roth (2018) for a detailed discussion of these issues. ⮭

- Crucially, Conway rejects a Spinozist position that reduces God to nature (CC 64; IX.3). Holenmerism allows that distinct ontological items can be co-located in time as well as space. God is holenmerically present in nature, but ontologically distinct from it. ⮭

- Christia Mercer (2012b) offers a helpful metaphor for understanding Conway’s account of Christ’s intermediary status: imagine a perfectly designed score that is realized by various changing movements or progressions of musical notes. Mercer explains that like Christ, the score is something perfect and eternal, but the performance of the score involves change in the variations of the notes that realize this divine pattern (2012b: 186). ⮭

- See Jonathan Head (2017) for further discussion of issues concerning time and salvation. ⮭

- Further, divine justice requires that the proper subject of reward and punishment persist throughout radical change from one species to another (CC 29; VI.2). ⮭

- Peter Loptson suggests that the interpretation that every moment God creates may raise a problem for understanding God’s immutability (1982: 32). To avoid conflict, he argues that we should just interpret Conway as claiming that God continuously creates, which fits well with Conway’s claim that preservation is a constant act of creation (CC 33; VI.6). ⮭

- The continuation of that paragraph section further says that “if we wish to speak properly, there is no motion because all motion is successive and can have no place in God” (CC 18; III.8). It may be tempting to read Conway as denying the existence of motion in general. But we can also understand Conway as simply saying that motion does not exist in God. Motion is part of the nature of creatures (CC 14; II.6). If motion does not exist, neither do creatures. For that reason, a less eliminative reading of III.8 is preferable. ⮭

- Conway’s claims about motion exhibit a clear Aristotelian influence, an analysis of which goes beyond the scope of this paper. Notably, Conway also cites Aristotle on spirit and matter (CC 51; VII.4). Mercer’s account of early modern Platonist metaphysics does not exclude Aristotelian influence: she argues that early moderns practiced “conciliatory eclecticism” sometimes combining Plato, among other thinkers, with Aristotle (2012a: 107–111). ⮭

- There is consensus that Conway is a monist about kinds of created substance. But there is debate over whether she is also an existence monist, i.e., whether there is only numerically one created substance. See Emily Thomas (2020) for a critical response to Jessica Gordon-Roth’s (2018) claim that Conway vacillates on her answer to the question of existence monism about the created world. Existence monism would raise a further set of issues for moral responsibility. ⮭

- Sarah Hutton (1997) and Stephen Clucas (2000) endorse spiritualist interpretations according to which body is reducible to spirit. ⮭

- Broad’s non-reductive interpretation has some advantages over the reductive, spiritualist interpretation. First, it helps to make sense of Conway’s position that change requires material parts (CC 20; III.9). It seems that matter cannot be reducible to spirit if the changes that spirit undergoes depend on physical parts. Second, Conway claims that spirit and body are modes of created substances (CC 41–42; VII.1). Modal dependence is an asymmetric relation. Reductionist interpretations of Conway’s monism have it that the body is grounded in spirit and not vice versa. Conway, however, describes the metaphysical status of body and spirit equally as modes of created substance. Spirit and body alike depend on the essence of substance, i.e., mutability. I offer these only as preliminary, not decisive considerations. ⮭

- It is worth mentioning that Reid qualifies his point about the vitalist aspects of matter in More’s early position. Reid also describes early More as claiming that “by virtue of being vital, these things would not really qualify as bodies at all” (2018: 50). Conway never presents a dichotomy between living and having a body: she argues that bodies are living. Ultimately, Reid claims that early More’s considered view is that there is no such thing as a “mere body” (2018: 51). Conway agrees that bodies have non-material aspects, so there is clear agreement on that weaker claim. ⮭

- A vitalist materialist conception of matter posits vital motion without assuming the existence of spirit, contrary to Conway. That materialist version of vitalism contrasts with the inert conception of matter that Conway attributes to Descartes and Hobbes as mere “extension and impenetrability” (CC 65–66; IX.6). Ann Thomson (2001) provides a helpful discussion of the distinction between early modern mechanistic materialism and vitalist materialism. Charles Wolfe and Michaela van Esveld (2014) provide a useful discussion of the relevant Epicurean context for vitalist materialism in the early modern period. ⮭

- Conway’s descriptions of local motion are brief, but they fit with Henry More’s account of local motion in The Immortality of the Soul as changes in figure, posture, and degree of motion in material parts (Book 1, Chapter VII, Section 6). ⮭

- In a May 1651 letter from Henry More to Conway, omitted from the 1930 edition of her correspondence, More discusses paradoxes of motion and claims that there is no motion at an instant. Conway apparently agrees in the case of local motion, but she allows for instantaneous transmission in the case of vital motion. For Conway’s correspondence, see Marjorie Hope Nicolson and Sarah Hutton’s 1992 edition of The Conway Letters: The Correspondence of Anne, Viscountess Conway, Henry More, and their Friends. ⮭

- Conway claims that “a creature is capable of a further and more perfect degree of life, ever greater and greater to infinity” (CC 67; IX.7). ⮭

- Conway emphasizes that Christ’s status as a mediator does not cancel God’s immediate presence and action in creatures (CC 25; V.4). ⮭

- See also Robert Kane (1996) on the ultimate responsibility view of freedom. Thank you to an anonymous referee for the suggestion that the ultimate responsibility approach might pair well with Conway’s position on freedom. ⮭

References

1 Borcherding, Julia (2019). Nothing Is Simply One Thing: Conway on Multiplicity in Causation and Cognition. In Dominik Perler and Sebastian Bender (Eds.), Causation and Cognition in Early Modern Philosophy (123–44). Routledge. http://doi.org/10.4324/9781315146539-7

2 Broad, Jacqueline (2003). Women Philosophers of the Seventeenth Century. Cambridge University Press. http://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190673321.001.0001

3 Broad, Jacqueline (2018). Conway and Charleton on the Intimate Presence of Souls in Bodies. Journal of the History of Ideas, 79(4), 571–91. http://doi.org/10.1353/jhi.2018.0035

4 Clucas, Stephen (2000). The Duchess and the Viscountess: Negotiations between Mechanism and Vitalism in the Natural Philosophies of Margaret Cavendish and Anne Conway. In-Between: Essays and Studies in Literary Criticism, 9(1–2), 125–36.

5 Conway, Anne (1992). The Conway Letters: The Correspondence of Anne, Viscountess Conway, Henry More, and Their Friends 1642–1684 (Revised Edition). Marjorie Hope Nicolson and Sarah Hutton (Eds.). Clarendon Press. http://doi.org/10.1093/actrade/9780198248767.book.1

6 Conway, Anne (1996). The Principles of the Most Ancient and Modern Philosophy. Allison P. Coudert and Taylor Corse (Eds. and Trans.). Cambridge University Press. http://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511597978.005

7 Freddoso, Alfred J. (1991). God’s General Concurrence with Secondary Causes: Why Conservation Is Not Enough. Philosophical Perspectives, 5, 553–85. http://doi.org/10.2307/2214109

8 Gordon-Roth, Jessica (2018). What Kind of Monist Is Anne Finch Conway? Journal of the American Philosophical Association, 4(3), 280–97. http://doi.org/10.1017/apa.2018.24

9 Head, Jonathan (2017). Anne Conway on Time, the Trinity, and Eschatology. Philosophy and Theology, 29(2), 277–95. http://doi.org/10.5840/philtheol201781480

10 Head, Jonathan (2019). Anne Conway and Henry More on Freedom. International Journal of Philosophical Studies, 27(5), 631–48. http://doi.org/10.1080/09672559.2019.1659843

11 Hutton, Sarah (1996). Henry More and Anne Conway on Preexistence and Universal Salvation. In Marialuisa Baldi (Ed.), “Mind Senior to the World”: Stoicismo e Origenismo Nella Filosfia Platonica del Seicento Inglese (113–26). FrancoAngeli.

12 Hutton, Sarah (1997). Anne Conway, Margaret Cavendish and Seventeenth Century-Scientific Thought. In Lynette Hunter and Sarah Hutton (Eds.), Women, Science, and Medicine 1500–1700 (218–34). Sutton Publishing.

13 Hutton, Sarah (2004). Anne Conway: A Woman Philosopher. Cambridge University Press. http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511487217

14 Hutton, Sarah (2018). Goodness in Anne Conway’s Metaphysics. In Emily Thomas (Ed.), Early Modern Women on Metaphysics (229–46). Cambridge University Press. http://doi.org/10.1017/9781316827192.013

15 Kane, Robert (1996). The Significance of Free Will. Oxford University Press. http://doi.org/10.1093/0195126564.001.0001

16 Lascano, Marcy P. (2013). Anne Conway: Bodies in the Spiritual World. Philosophy Compass, 8(4), 327–36. http://doi.org/10.1111/phc3.12025

17 Lascano, Marcy P. (2017). Anne Conway on Liberty. In Jacqueline Broad and Karen Detlefsen (Eds.), Women and Liberty, 1600–1800: Philosophical Essays (163–77). Oxford University Press. http://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198810261.003.0011

18 Loptson, Peter (1982). Introduction. In Peter Loptson (Ed.), Principia philosophiae (1–59). Martinus Nijhoff.

19 Mercer, Christia (2012a). Platonism in Early Modern Natural Philosophy: The Case of Leibniz and Conway. In James Wilberding and Christoph Horn (Eds.), Neoplatonism and the Philosophy of Nature (103–26). Oxford University Press. http://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199693719.003.0006

20 Mercer, Christia (2012b). Knowledge and Suffering in Early Modern Philosophy: G. W. Leibniz and Anne Conway. In Sabrina Ebbersmeyer (Ed.), Emotional Minds (179–206). De Gruyter. http://doi.org/10.1515/9783110260922.179

21 Merchant, Carolyn (1979). The Vitalism of Francis Mercury Van Helmont: Its Influence on Leibniz. Ambix, 26(3), 170–83. http://doi.org/10.1179/amb.1979.26.3.170

22 More, Henry (1925). The Immortality of the Soul. In Flora Isabel MacKinnon (Ed.), Philosophical Writings of Henry More (57–180). Oxford University Press.

23 Pasnau, Robert (2011). Metaphysical Themes, 1274–1671. Oxford University Press. http://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199567911.001.0001

24 Quinn, Philip (1988). Divine Conservation, Secondary Causes, and Occasionalism. In Thomas V. Morris (Ed.), Divine and Human Action: Essays in the Metaphysics of Theism (50–73). Cornell University Press.

25 Reid, Jasper (2018). The Cambridge Platonists: Material and Immaterial Substance. In Rebecca Copenhaver (Ed.), Philosophy of Mind in the Early Modern and Modern Ages (43–68). Routledge. http://doi.org/10.4324/9780429508158-3

26 Stump, Eleonore (1999). Alternative Possibilities and Moral Responsibility: The Flicker of Freedom. The Journal of Ethics, 3, 299–324.

27 Thomas, Emily (2017). Time, Space, and Process in Anne Conway. British Journal for the History of Philosophy, 25(5), 990–1010. http://doi.org/10.1080/09608788.2017.1302408

28 Thomas, Emily (2020). Anne Conway as a Priority Monist: A Reply to Gordon-Roth. Journal of the American Philosophical Association, 6(3), 275–84. http://doi.org/10.1017/apa.2019.1

29 Thomson, Ann (2001). Mechanistic Materialism vs Vitalistic Materialism. La Lettre de la Maison française d’Oxford, 14, 21–36.

30 Wolfe, Charles T. and Michaela M. van Esveld (2014). The Material Soul: Strategies for Naturalising the Soul in an Early Modern Epicurean Context. In Danijela Kambaskovic (Ed.), Conjunctions of Mind, Soul and Body from Plato to the Enlightenment, vol. 15 of Studies in the History of Philosophy of Mind (371–421). Springer. http://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9072-7_19