This paper develops an original account of intersectional feminist theory as a type of non-ideal theory by addressing some of the feminist critiques of intersectionality. While intersectionality has gained tremendous popularity since Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term in 19891 and is now the gold standard in feminist scholarship, there has also been a “mushrooming intersectionality critique industry” (May 2015: 98) in more recent times.2 The current situation can be summarized as follows: although there is widespread agreement among feminist scholars with the intersectional mode of thinking that feminist theory should pay attention to multiple interrelated forms of oppression, there is controversy over whether “intersectionality” is a suitable conceptual tool to achieve this. One possible reason for this situation is that there is little consensus on what intersectionality is or does for feminist theory. What exactly does it mean for feminist theory to be intersectional? What kind of work should feminist philosophers engage in, in order to implement theory in an intersectional manner? The primary aim of this paper is to propose answers to these questions, thus contributing toward untangling the controversy surrounding the notion of intersectionality and to the efforts to make feminist theory more intersectional.

The first section starts by analyzing two major critiques of intersectionality: the incommensurability critique (intersectionality leads to multiple, mutually exclusive identities of women) and the infinite regress critique (intersectionality endlessly breaks women into smaller subgroups). Both critiques take intersectionality to fragment women along the lines of identity categories such as race, class, and sexuality. Underlying this interpretation, I argue, is the metaphysical assumption that identity is a fixed entity. Intersections of gender with race would fragment women only when there is such a thing as a fixed racial identity, for example, that of “Black” that can break the identity of “women” into a smaller unified piece of identity of “Black women,” which can be broken again by other fixed identities of “queer,” “heterosexual,” “disabled,” and so on. This is far from how identity is actually lived. The critics seem to be concerned only with how women would be fragmented by the intersection of identities, while disregarding what women who exist at the intersection of multiple forms of oppression, such as women of color, are actually doing with their identities.

To demonstrate this point, the second section explores concrete cases of how Asian American women experience their “Asian” identity in their everyday lives.3 The cases include those pertaining to the stereotypical binary between the “Asian-as-patriarchal vs. White-as-gender-progressive” identities, the “model minority” myth, growing anti-Asian racism in the age of COVID-19, and Asian-Black feminist solidarities. As these cases will illustrate, what it means to be Asian or to have Asian identity is not fixed but changing according to how this identity is related to power. I will identify three characteristic types of the identity-power relationship: manifestation of power-as-oppression through the construction of identity, reproduction of power-as-oppression, and creation of new forms of power, namely resistance and solidarity, through the reconstruction of identity. The cases show that Asian women do not passively hold or possess their identity. In contrast, they navigate power dynamics and negotiate the relationship between power and identity in their lives in at least three different ways. In this regard, the lives of women of color and other multiply-oppressed women can be explained as the locus at which the power dynamics of oppression are manifested and resisted through the (re)construction of identity.

Based on this analysis, the third and last section draws a connection between intersectionality and non-ideal theory. Although intersectionality and non-ideal theory are both oft-discussed topics in feminist social and political philosophy, the relationship between the two has been less examined. Engaging some of the key works on non-ideal theory, I develop the following accounts: intersectional feminist theory is a strong version of non-ideal theory that focuses on the lives of the multiply oppressed, that is, the locus where oppressions operate and are challenged, and thereby shows how the intersecting structure of oppressions works and helps to generate strategies to dismantle this structure. In contrast, the critiques of intersectionality are weaker versions of non-ideal theory that address the actual (in the opposite sense of the hypothetical) but do not engage oppressed people’s lives, and thus fail to show how the system of oppression works.

1. Critiques of Intersectionality: Incommensurability, Infinite Regress, and Fragmentation

Let us take a closer look at the two strands of critique. The first sees intersectionality as resulting in the increase of incommensurable identities. For example, Naomi Zack (2005) contends in her oft-cited critique that intersectionality does not help to make feminism inclusive, but rather fragments women into multiple discrete identities. According to Zack’s interpretation of intersectionality, each specific intersection of race and class represents a distinct kind of gender identity mainly because intersectionality rejects the additive analysis. Black working-class women, for example, are not the women in the white feminist sense who are in addition Black and in addition working-class. Instead, Zack claims that intersectionality construes Black working-class women as having their own gender identity, which is distinguished from those of women of other races and classes such as white middle-class women’s gender identity. This way, different intersections are reified as “different kinds of female gender [that] may be perceived to be so distinctive as to be virtually incommensurable” (Zack 2005: 7–8).

Zack argues that the multiplication of women’s discrete identities reinforces the exclusion of women of color: once the identities of women of color become incommensurable with those of white women, life situations of women of color are understood as the problem belonging only to their own identities, rather than the problem that “women” face. For instance, “most of feminist anthologies are still either about gender, in which the subjects are white women, or about race, in which the subjects are [B]lack women, Latinas, or other women of color” (2005: 16), which suggests that, according to Zack, there is no real change that the feminist attention to intersectionality has made to the hegemony of “white women as women.” Zack concludes that intersectionality causes “de facto racial segregation,” which fixes women of color at their specific intersection and merely allows them to create their own feminisms, while retaining the status quo dominance of white feminism intact (2005: 2–3, 7–8).

Nancy Ehrenreich (2002) also makes an argument that falls under the umbrella of the incommensurability critique. The intersection of race and gender subordinations, according to Ehrenreich, makes the interests of women of color “fundamentally different” from those of white, racially privileged women. Similarly, conflicts between the interests of poor and affluent women and lesbian and heterosexual women become inevitable, which undermines the viability of meaningful advocacy on behalf of “women” (Ehrenreich 2002: 266–69). Ehrenreich calls this the “zero sum” problem—“it is not possible to simultaneously further the interests of all the various subgroups within a particular group” (2002: 267).

Another line of critique is that intersectionality incurs an infinite regress, as Ehrenreich defines it, “the tendency of all identity groups to split into ever-smaller subgroups” (2002: 267). The association of intersectionality with infinite regress has become so influential that it has been examined by many intersectional scholars (Carastathis 2016: 131–34; Collins & Bilge 2016: 127–28; Gasdaglis & Madva 2020: 1300–1306). This strand of criticism interprets intersectionality as impeding generalizations about group interests (of, for example, women) or even about subgroup interests (of, for example, women of color, Black women), as there is “a potentially endless list of hybrid positions or cross-cutting groupings that can be yielded (such as [B]lack working class, lesbian, young, poor, rural, disabled and so on)” (Anthias 2013: 5–6). As the regress goes on, there would be no group, and the individual would become the only cohesive unit of analysis (Ehrenreich 2002: 270).

The infinite regress problem is closely linked to the “dilemmas of difference” that feminist theory has confronted from its inception (Di Stefano 1988). Georgia Warnke describes the dilemma as follows. Once feminist theory starts recognizing differences between European and non-European women or between rich and poor women, it is:

led to still further differences between rich European women and poor European women or between middle-class American women and middle-class Argentinean women and so on. . . . [If so,] can there be any identity to the category of woman so that women as a group can form the locus of feminist interests and political practice? If there are only rich and poor women, European and non-European women, and if these groups themselves break down into smaller groups depending on race, class, ethnicity, and age, what happens to a specifically feminist or women’s perspective? (Warnke 2013: 248–49, emphasis added)

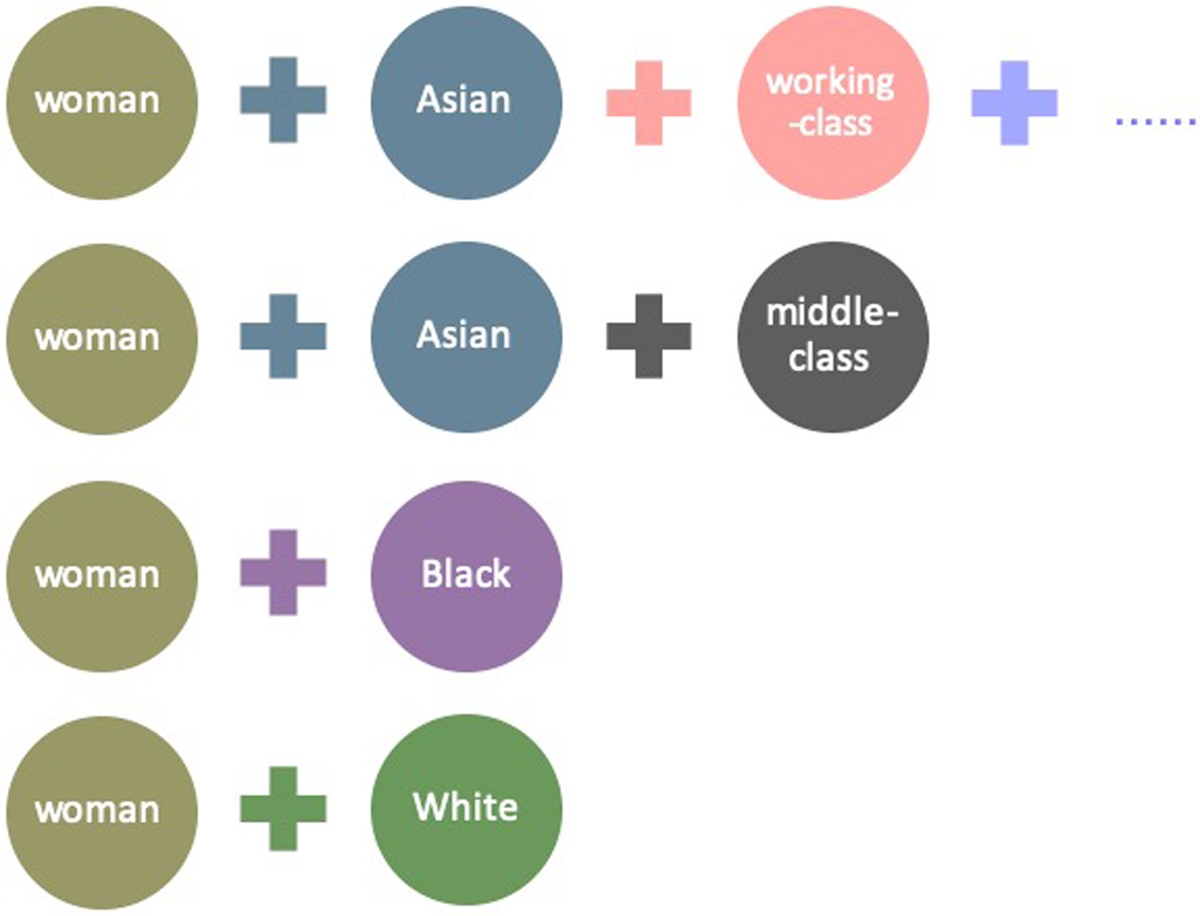

In sum, in both types of critique reviewed here, intersectionality is interpreted as a matter of division or fragmentation. The infinite regress critique is the claim that every time different identity categories (such as race, class, sexuality, etc.) are factored in, women are fragmented into even finer subgroups. The incommensurability critique is the claim that these subgroups end up having irreconcilably different identities. As each intersection of race and gender (e.g., Black women, white women) or of class and gender (e.g., working-class women, middle-class women) is reified as a distinct identity, women, the critics argue, are fragmented along the lines of race and class.

The interpretation of intersectionality as fragmentation, however, relies on a problematic understanding of identity.4 Intersections of gender with other identities would fragment women only when each of these identities is a fixed thing that remains the same across different people, occasions, and contexts. More specifically, the criticism assumes a view close to what Elizabeth Spelman (1988) calls the “pop-bead metaphysics,” where each identity category, such as race, gender, and class, is analogized as a bead that can be popped into other beads to form a necklace or bracelet. Spelman uses this analogy to illustrate (and criticize) the additive analysis of identity: the necklace—one’s identity as a whole—consists of a sum of beads—their race, gender, class, and other identity categories—which are neatly divisible from and unaffected by one another. According to this view, one’s being a “woman” is unrelated to the racial and class parts of her identity, just as each bead exists on its own and separable from other beads. Hence all women share the same identity as a “woman,” and differences among them lie only in their “non-woman” parts, such as the racial bead and the class bead into which the gender bead labeled “woman” is inserted (Spelman 1988: 14–15, 136–37).

While Spelman’s metaphor is originally intended to illustrate the relationship between the beads (that is, racial, gender, and other identities), I use it to describe the characteristics of each bead/identity. As a metaphysics of identity, the pop-bead view makes the following two flawed assumptions. (i) First, it assumes that (racial/gender/class/etc.) identity is already given as a thing that does not change. For example, the bead labeled “Asian” exists even before someone lives as an “Asian” in specific sociohistorical contexts through interactions with other people, communities, and society. This means that the “Asian” identity stays the same regardless of what the subject does with this identity and what relationships they build with the power dynamics of society. That is, identity is a fixed entity that remains the same across all contexts and occasions. One’s having “Asian” identity is like taking a pre-made, unchanging bead labeled as such, and thus, it remains the same whoever takes it. (ii) This characteristic of identity makes it possible to put people in stable distinct groups according to their identities. If “Asian” identity is a fluid and flexible process, as I will argue in the following sections, different people—or even the same person—who live as “Asian” may experience or build different narratives of what it means to be “Asian.” During this meaning-making journey, they may find commonalities/intersections as well as differences/tensions with those who live with other racial identities. (I will explain this in detail in §2.5). In contrast, according to the pop-bead metaphysics, racial groups are clearly demarcated from one another, in the same way that the bead labeled “Asian” is an ontologically different entity from other beads labeled “Black,” “Latinx,” and so on.

This is the view of identity that the criticisms of intersectionality rely on (see Figure 1). The infinite regress critique can be put as follows: women, or the group of people who possess the bead labeled “woman,” are divided into smaller groups according to whether they insert this bead into those labeled “Asian,” “Black,” or “White.” In a like manner, Asian women are further divided into smaller subgroups once different class identities are popped into the “woman” and “Asian” beads that they have. And the same goes for sexuality, disability, age, and so on. The incommensurability critique is the claim that the end products—namely, the sum of identity categories analogized with pop-bead necklaces—are mutually exclusive. Although Asian women and Black women have the same bead labeled “woman,” as it is inserted into two ontologically distinct entities, namely, the two beads labeled “Asian” and “Black” respectively, it ends up constituting necklaces that are “so distinctive as to be virtually incommensurable” (Zack 2005: 8). In sum, both critiques presuppose that there is some Asian identity or Asianness shared by all individuals who identify as Asian, and this Asianness constitutes a thing that is clearly distinguished from Black and other racial identities. As noted above, this presupposition is closely related to the view of identity as a fixed entity, which exists without being affected by how it is lived by different people and lived in varying relationships with power.

This picture of identity is far from how identity is experienced in reality. I agree with Patricia Hill Collins and Sirma Bilge that critics of intersectionality often adopt a limited understanding of the concept, merely as a form of “abstract inquiry” while overlooking intersectional praxis (Collins 2015: 15–17; Collins & Bilge 2016: 129). I argue that the critics are so preoccupied with the abstract inquiry of how women would be divided by the intersection of identities that they neglect what women who exist at the intersection of multiple forms of oppression, such as women of color, are actually doing with their identities. When we look into their everyday lives, which I do in the next section, the criticism does not hold.

2. Cases: How Asian American Women Experience Asian Identity

2.1. Analysis: Three Types of Identity-Power Relationships

This section shows that, contrary to the critics’ static view, identity is experienced in a fluid and flexible process. I analyze different ways in which Asian American women experience their “Asian” identity and demonstrate that what it means to be Asian varies according to how this identity is related to the dynamics of power. The charge of fragmentation is a misunderstanding of intersectionality grounded in a misunderstanding of identity that fails to consider how identity is actually lived in its changing relationship with power. It is necessary to clarify what I mean by “power” here. In this paper, I use the term to refer to two distinct forms of power: the negative form as structural oppression (Frye 1983; Young 1990) and the positive form as solidarity and empowerment against oppression (Allen 1999; 2008).5 I argue that what an identity is—especially marginalized race, gender, and other group identities—depends on how the identity is linked to the negative and positive forms of power. There are at least three different types of relationships between identity and power:

-

Manifestation of oppression: By this term, I refer to cases in which the power of structural oppression is manifested in constructing meanings of an identity.

I analyze how intersecting gender and race ideologies manifest in shaping the Asian-as-patriarchal identity (§2.2).

I also discuss what it means to be Asian during the COVID-19 pandemic. The intersecting structure of xenophobic, racial, language, and gender oppression operates to attach the “Yellow Peril” label to Asian bodies (§2.4).

-

Reproduction of oppression: There is a tendency that marginalized groups, in order to survive in an oppressive society, conform to the meaning of their identities as constructed by the oppressive structure. This survival strategy reproduces and reinforces the power of oppression.

For instance, I examine how the Asian/Gender-Backward vs. White/Gender-Progressive binary is reflected in partner choices and reproduces white supremacist hegemony (§2.2).

Living up to the name of “Model Minority” has been a tactic for many Asian Americans to blend into the white-dominated US society. Yet, it does not really protect them from racism, as seen in the case of anti-Asian attacks during the pandemic (§2.3).

-

Transformative resistance to oppression: By reshaping and redefining their identity as a center of resistance to oppression and meaningful transformation of society, marginalized groups create new forms of power as solidarity and empowerment.

I discuss some of the recent Asian American efforts to break up the acquiescent model minority stereotype and to speak up against racism. I focus on how Asian American feminist movements redefine what it means to be Asian and build solidarity with other feminists of color to dismantle the oppressive structure (§2.5).

As such, the case study plays a crucial role in supporting the argument of this paper. The cases will demonstrate that identity is not experienced in a way that the criticisms picture it to be. It is not that identity such as “Asian” is already there, as if it were some tangible object like a bead and thus having “Asian” identity were like possessing the pre-given thing. Identity is situated in a fluid process, in which the subject navigates at least three different relationships with power. “Asian” identity—what it is and what it means to have this identity—is being made as the subject lives as “Asian” through these changing relationships between identity and power (see Table 1). In short, the cases below will show that the view of identity as a fixed entity does not hold in actuality, and therefore, the criticism of intersectionality that relies on this flawed view of identity cannot hold as well.

The View of Identity (e.g., “Asian” Identity) as a Fluid Process.

| Identity-Power Relationship | Examples of Identity |

| a. Manifestation of oppression |

|

| b. Reproduction of oppression |

|

| c. Transformative resistance to oppression |

|

2.2. Asian as Gender-Backward vs. White as Gender-Progressive

I begin this analysis with a reference to Crazy Rich Asians (Chu 2018), the first Asian-led Hollywood movie in 25 years that portrays a type of tension that Asian American women face with regard to their identities as “Asians,” “Americans,” and “women.” When Rachel Chu, a Chinese-American economics professor, meets her co-ethnic boyfriend’s mother, Eleanor, for the first time in Singapore, Rachel talks about how passionate she is about her career. Eleanor quickly dismisses Rachel, saying, “Pursuing one’s passion . . . how American.” Eleanor speaks about how she has been sacrificing herself for the family, or committing herself to “Asian” values. In the words of one of Rachel’s friends, Eleanor thinks Rachel is a kind of “banana—yellow on the outside, white on the inside.”

Karen Pyke and Denise Johnson (2003) identify a similar pattern in their interviews with young Asian American women: whether an Asian American woman is family- or career-oriented, or whether she has a quiet and reserved or an outgoing and outspoken personality, tends to translate to whether she is an Asian or a whitewashed American. Being Asian is often perceived, by both Asians and non-Asians, as inherently serving patriarchal values, which is diametrically opposed to whiteness—a designation that is considered more progressive in terms of gender. This opposition between Asian and white identities leads some Asian American women to feel pressured to comply with the stereotype of Asian femininity in co-ethnic settings, because otherwise their racial/ethnic identity would be challenged (Pyke & Johnson 2003: 47–49), just like Rachel is treated as a banana. For instance, a Korean-American girl named Lisa was worried that if she spoke up in classes where she had many Asian peers, she would be considered no longer Asian—a designation linked with the image of a shy, quiet, and passive girl. Lisa said: “I think they would think that I’m not really Asian. Like I’m whitewashed . . . like I’m forgetting my race. I’m going against my roots and adapting to the American way. And I’m just neglecting my race” (Pyke & Johnson 2003: 48).

Gendered racial stereotypes are pervasive in multi-racial settings as well. According to a study of workplace experiences of East Asians in North America, those who acted dominant and thus violated the stereotype of being less dominant than whites were more likely to be disliked by their coworkers and targeted for racial harassment (Berdahl & Min 2012: 146–49). Similarly, in a qualitative study on Asian American women’s experiences of discrimination, 34% of the participants responded saying that they were expected to be submissive and passive, and faced surprise or retaliation when they challenged this pigeonholing. One participant recalled: “male Caucasian friends [told me] that I didn’t ‘act like an Asian woman’ when I objected to something they said or did, as I was not as docile and gracious as they thought Asian women should be” (Mukkamala & Suyemoto 2018: 39, see also 42–43).

These experiences highlight the stereotypical dilemma that one cannot have Asian identity and resist patriarchy at the same time: Asian women either have to conform to gender-discriminatory norms of femininity to retain their racial identity, or risk their racial identity to pursue gender-egalitarian values. While some Asian women choose (or are pressured into choosing) the former, others opt for the latter. Nadia Kim (2006) tracks one strategy that Asian women use to oppose patriarchal norms: acclaiming white masculinity and denigrating Asian masculinity. In Kim’s interviews with Korean immigrant women in the US, the women used “the ideal of gender progressive white American man as the bar against which they challenged Korean men as patriarchal, hence backwards in ‘third world’ sense” (Kim 2006: 532). This way, the women rearrange the relationship between their identity and the power of gender oppression. However, this is a limited resistance strategy as it reaffirms white supremacist hegemony that establishes whiteness as the norm.

For example, Heesu, who had dated a white American man to live a life unburdened by Confucian patriarchy but ended up marrying a Korean man said that Korean men should “give up things that are too Korean in a way. . . . [My husband] wants to Koreanize the American’s way of thinking . . . but I think the opposite, that you should be Americanized if you’re living here in America.” Heesu thought that Korean traditions were at odds with white America, so her husband needed to be culturally Americanized/whitewashed (Kim 2006: 529).6 Yet this pro-assimilation stance is, as Karen Pyke maintains, a double-edged sword because it reinforces the image of Asians as inferior to whites (Pyke 2010: 89–90). I should make it clear that my discussion is not to blame individual Asian women who view “white men as avenues of liberation . . . from the patriarchal . . . realities of their own backgrounds” (Chou & Feagin 2015: 161). Rather, I maintain that the structure of white supremacist patriarchy places them in a lose-lose situation. The fact that resistance to (co-ethnic) male dominance is connected to the reinforcement of white (male) dominance, or in other words that Asian women are in a social position wherein they cannot employ a “magic bullet” resistance strategy, demonstrates how dense the interlocking web of racism and sexism is (Kim 2006: 533; Pyke 2010: 91–92). Here, what it means to be Asian is constructed by the manifestation of white supremacist gender hegemony, which disparages Asian/nonwhite expressions of gender and privileges white expressions of gender. The (limited) resistance tactic employed by some Asian women, which involves compliance with the negative connotation of Asian identity, reproduces hegemonic power.

2.3. Asians as a Model Minority (Who Do Not Speak Up against Racism)

In their influential book Myth of the Model Minority (2015), Rosalind Chou and Joe Feagin point out that the “model minority,” which seems like a compliment, is in fact an oppressive and damaging label that puts pressure on Asian Americans to conform to the white-dominated racial order. Calling Asian Americans “model minorities” enables whites to differentiate themselves from people of color and to disparage other people of color (especially Black and Latinx people) as “problem minorities” that do not attain as high educational or career achievements as do the model minorities. The stereotype also sustains the myth that all Americans of color can achieve the American dream just like the “model” minorities, who work hard and do not challenge the status quo of racial hierarchy that has whites at the top but are eager to assimilate into it. To keep the “top subordinate” title and avoid racial hostility, Asian American communities have often conformed to the “success-driven, assimilationist Asian” stereotype (Chou & Feagin 2015: 2–4, 20–21, 142–43).

This conformity is expressed in the form of Asians’ attack of other Asians who speak up for change. Chou and Feagin discuss the case of an Asian American student organization in a large US university. The organization published a report on problems faced by Asian American students on campus and made suggestions how the university could better address their needs, such as hiring an Asian American mental health counselor and ensuring more Asian American representation in student government. The report drew positive responses from the university administration and other students of color. However, this student organization was accused by fellow Asian American students of “making Asian Americans look bad” (2015: 169–73). As one member of the organization recalled: “[T]hat was the most hurtful because a lot of the criticism came from our own community. . . . [P]eople were saying, ‘Why do you have to rock the boat?’ People saying, ‘Why are you looking for trouble? Why are you seeing things that aren’t there? I’ve never experienced racism. It must not exist’” (2015: 170).

This case illustrates how the identity of “model minorities who do not cause a ruckus” has been embraced and internalized by many Asian Americans. For Asian American students, as Chou and Feagin note, “fear of white backlash trumped even modest actions to bring campus change” (2015: 170). Taking the model minority identity to be “their ultimate ticket into gaining social acceptance,” the students hoped that the actions for change would not “ruin it for the rest of them” (2015: 173; quoting Tuan 1998: 8). This kind of acquiescence may be understood as a survival technique that individual Asians employ to protect themselves from white retaliation. However, it ultimately contributes toward maintaining the root cause of such retaliation—that is, the racist structure of US society—by discouraging Asian communities from subverting it. Here, the power dynamics surrounding the Asian identity can be put this way: the power of structural racism manifests in constructing the Asian-as-model-minority identity and is reinforced through Asians’ conformity to this meaning of being Asian.

2.4. Asian as Yellow Peril/Perpetual Foreigner: Anti-Asian Racism amid COVID-19

Striving to fit white expectations does not protect Asian Americans from racism. This is demonstrated by the recent pandemic-fueled surge in anti-Asian hate incidents. Since COVID-19 spread across the US and states began shutting down in March 2020, there has been a growing tendency to blame Asians for the pandemic. One-third of Americans have witnessed someone blaming Asian people for the pandemic, according to a survey conducted in April 2020 (Jackson, Berg, & Yi 2020). President Trump’s repeated reference to the coronavirus as the “Chinese virus” and “kung flu” has intensified this tendency (Itkowitz 2020; Nawaz & Choi 2020; Wang 2020), which ignored the World Health Organization’s guidelines discouraging the use of geographic locations when naming diseases because doing so stigmatizes people living in those locations (AAJA MediaWatch Committee 2020). Stop AAPI Hate, a national coalition documenting COVID-related racist incidents against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, collected more than 2,800 reports nationwide from March to December 2020 (Stop AAPI Hate 2021). Some firsthand experiences reported include:

I was in line at the pharmacy when a woman approached me and sprayed Lysol all over me. She was yelling out, “You’re the infection. Go home. We don’t want you here!” I was in shock and cried as I left the building. No one came to my help. (Marietta, GA)

I got into the elevator (mask on) so I could get my mail from the lobby. The elevator opened on the 4th floor and this unmasked white woman yelled “OH HELL NO” when she saw me. The elevator door opened on the 1st floor and she gets out of the elevator and looks me up and down and goes, “You f**king Chinese people, you’re not going to get away with this, we’re going to get you.” (Portland, OR)

I was the only Asian American at a conference with work colleagues and I had an allergy flare up that day. One woman, seeing me sneeze, told me I couldn’t be there, that I needed to leave, and ordered me not to touch any of the coffee and cookies put out by the convention. She singled me out when other people in the conference were sneezing, sniffling and coughing. (Monterey, CA)

Attacks have also become physical, where Asian Americans were spit on, beaten, slashed, and killed (Tavernise & Oppel 2020; Valentine 2021). In January 2021, 84-year-old Vicha Ratanapakdee, who went for a morning walk in his San Francisco neighborhood, died after being violently shoved to the ground. More than 20 attacks targeting elderly Asian Americans have been reported in Oakland’s Chinatown alone over the first two weeks in February 2021 (Cowan 2021; Westervelt 2021).

In the racist rhetoric underlying these incidents, being Asian means being diseased, dirty, and dangerous: Asians are the ones who brought the virus to the US and who are spreading it. This clearly shows that Asian Americans are not fully accepted as Americans, no matter how hard they try to be exemplary minorities hoping for acceptance. As one commentator notes, Asian Americans are “racialized as the perpetually ‘foreign’ (read un-American) [and] once again the enemy. . . . Every time [President Trump] says ‘foreign virus,’ and every time the right-wing media uses the terms ‘Chinese virus’ and ‘Wuhan virus,’ they are actively reinforcing that once again, ‘the Chinese’ are diseased, evil aliens bent on harming ‘real’ Americans” (Wu 2020: 29). In brief, Asian Americans are seen as “perpetual foreigners” who are not part of America at best, and “yellow perils” who pose a threat to America at worst.

Xenophobic racism is not the only form of oppression that operates here. Pointing out that the Asian-as-threatening-minority identity is the flipside of the Asian-as-model-minority identity, Rosina Lippi-Green’s renowned book English with an Accent (2012) analyzes how language-focused discrimination marks Asian Americans as the Other. The ideology of the standard, non-accent English intersects with xenophobic racism, and entitles non-Asians to mock Asians (both US-born and immigrant) for their accents (real or imagined) (Lippi-Green 2012: 289–90). Key findings from the relevant literature are presented as follows:

Accent hallucination: Even when there is no foreign accent from Asians, non-Asians tend to hear it from them.

Unequal burden of communication: Non-native English speakers bear the brunt of responsibility to facilitate communication between native and non-native English speakers.

“Native English speakers are willing to judge Asian learners of English – their intelligence, friendliness, work ethic and many other complex personality traits – on the basis of very little information – as long as there is no ambiguity about race. That is, race sometimes has more of an effect than actual English language skills when such judgments are made” (Lippi-Green 2012: 285).

This way, race- and language-based oppression operates together to construct the meaning of being Asian to be an “unassimilable race” (2012: Ch. 15).

Sexism also exacerbates racist attacks on Asian women, who have reported 2.4 times more hate incidents than Asian men to the Stop AAPI Hate initiative (2020). Executive directors of the initiative suggest several factors that make Asian women more vulnerable to hate incidents. One is the sexist stereotype that “women are not going to fight back, are more vulnerable, less likely to respond, and so when people feel like they have a license to [harass someone], they [are going to] go after people who may appear to be vulnerable” (Lu 2020). This is especially the case for Asian women, who are racialized-sexualized as docile and shy. COVID-19 has been used as a rhetoric for perpetrators to inflict and justify harassment and misogyny against Asian women, who they think are weak and less likely to stand up for themselves. Other explanations for the gender disparity in COVID-related hate incidents include unequal caregiving responsibilities under patriarchy. The housework that women are expected to do, such as grocery shopping, takes them outside the home and makes them more vulnerable to racial harassment on the streets (Lu 2020).

In sum, the power of xenophobic racism, language-based discrimination, and sexism is manifested in forging the Asian-as-yellow-peril identity. The location of Asian American women at the intersection of these oppressions shapes their multilayered experiences of being Asian during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2.5. Beyond Model Minority: Asian American Feminist and Anti-Racist Movements

As it turns out during the pandemic, embracing the apolitical/acquiescent model minority identity and not speaking up does not protect Asians against racist hostility. Asians who have denied the existence of anti-Asian racism as a structure can no longer downplay it as they are actually more publicly scrutinized and vulnerable to attacks in their everyday lives.

With growing critical awareness of racism, Asians have been building new Asian identities that divert from the model minority myth. Asian American organizations set up websites to document firsthand experiences of anti-Asian discrimination across the US, such as Stop AAPI Hate (stopaapihate.org) and Stand against Hatred (standagainsthatred.org). They also put together resources to educate people on the anti-Asian hate across the country and denounce discrimination. For instance, the Asian American Journalists Association MediaWatch Committee (2020) published guidelines for news media covering the COVID-19 pandemic, and included recommendations such as avoiding the blanket use of generic images of Chinatown to illustrate stories on the virus. There have been local- and community-level campaigns as well. An LA-based Korean-American named Esther Lim published a booklet titled “How to Report a Hate Crime” in multiple Asian languages with assistance of her bilingual family and friends. The booklet, which was made online, includes useful phrases that less-English-proficient Asians can rely on in order to request help. It led to a collaboration with the LA versus Hate initiative, which sought to approach Asian communities where hate crimes were underreported (Lim 2020; Huang 2020).

As these movements illustrate, being Asian no longer means enduring and being willing to assimilate into the white-dominated racial order that actually attaches the negative labels of “yellow perils” and “perpetual foreigners” to Asians. Asian American movements denaturalize and deconstruct the “Asian = apolitical” identification and reconstruct Asian identity in a way that it means active engagement in anti-racist politics.

In particular, I want to draw attention to Asian Americans’ fight against the larger structure of white supremacist/anti-people of color racism, not only anti-Asian racism. An important edited volume titled Asian American Feminisms and Women of Color Politics (Fujiwara & Roshanravan 2018) traces the trajectory of how Asian American feminists have built cross-racial solidarity with other communities of color to challenge the system of white supremacy and heteropatriarchy. For example, the co-editor Shireen Roshanravan discusses #Asians4BlackLives, the solidarity campaign with the Black Lives Matter movement conducted by Asian American (mostly feminist and queer) communities and collectives. Instead of a simplistic “we, too, are victims of racism” logic, Roshanravan argues, this campaign intentionally ruptures the Asian identity constructed as the obedient, insular, and anti-Black model minority (Roshanravan 2018: 274–78). Asian Americans, as explained earlier, have become racially visible as model minorities at the expense of Black and Latinx communities that are derogated as problem minorities. That is, the authorized version of Asian identity has relied on anti-Black and anti-Latinx racism: it has drawn “hostile boundaries against other nonwhite groups while ‘protecting and serving’ white supremacy” (2018: 271). Enacting solidarity with Black communities requires critical consciousness-raising about and actions to undo anti-Blackness and white supremacy within Asian communities. Asians4BlackLives explicitly calls on Asian Americans to “reject the model minority myth, which was historically created to delegitimize Black resistance while absolving non-Black Americans from addressing systemic racism” (Asians4BlackLives 2020). Only when Asian Americans reject the Asian identity defined by the divisive racist optic, can they “generate an opacity in who/what [Asians] are” (Roshanravan 2018: 276) and open space for “crafting a new narrative of what it means to be [Asian] in the US” (W. et al 2015), which is essential in building substantial (not tokenistic) solidarity with Black communities.

Black and Asian Feminist Solidarities, a collaborative project between Black Women Radicals (BWR) and the Asian American Feminist Collective (AAFC), is another significant example of solidarity among feminists of color. As part of this project, BWR and AAFC co-hosted a panel discussion titled “Sisters and Siblings in the Struggle” on April 30, 2020. The participants had a critical conversation on the following aspects:

Between the histories of xenophobic racism, medical experimentation and surveillance, prejudice in (and out) of the public health system, the violence of white capitalist heteronormative patriarchal supremacy and more, Black and Asian American communities are disproportionately experiencing the detrimental impacts of [COVID-19]. In New York and across the nation, there is an increase of xenophobic racism and violence against Asian Americans. Reports have shown that in states and cities such as Louisiana, Chicago, Milwaukee, and Michigan that the majority of those who are infected and dying from [COVID-19] are Black. While there are well-documented tensions between Black and Asian American communities, there is an equally long history of Black and Asian solidarities and community building both in the United States and abroad. (Black Women Radicals & Asian American Feminist Collective 2020a)

How can Black and Asian American feminists engage in a critical dialogue on the impacts of COVID-19 in their respective communities? What can we learn from the long history of solidarity between our communities? More importantly, how can we continue to build Black and Asian feminist solidarity in this moment? (Black Women Radicals & Asian American Feminist Collective 2020b)

Among the important points that this example of solidarity suggests, I would like to focus on two that are particularly relevant to our discussion. First, in line with Asians4BlackLives and other movements analyzed above, Asian feminists who work toward cross-racial feminist solidarity create new narratives of what it means to be Asian. For them, their Asian identity is a starting point of solidarity with other feminists of color in order to subvert the intersecting structure of white supremacist capitalist heteropatriarchy. By recreating Asian identity, Asian feminists challenge the negative form of power as structural oppression and wield new forms of power as solidarity, resistance, and liberation.

Cross-racial feminist coalition-building also indicates that Asian women are no longer restricted to the “Asian/gender-backward vs. white/gender-progressive” binary (§2.2). According to this binary, Asianness implies a patriarchal and regressive identity that is inferior to the white identity, and thus, the only option that Asian women can choose for resistance seems to be distancing themselves from their Asianness. In contrast, in the case at hand, Asian feminists do not give up or deny their Asian identity in order to resist oppressions. Rather, they resist as Asians. They challenge what constructs the binary opposition between the Asian/backward and white/progressive identities in the first place, that is, the white-dominated gender hegemony, and change the connotation of Asian identity from “backward” to “progressive.” This shows that what it means to be Asian is not fixed at what has been established by the dominant hegemony. As Asian American feminisms grow, “Asian” is redefined as a “center of meaningful social change” that has transformative potential to challenge intersecting systems of oppression (Chun, Lipsitz, & Shin 2013: 920).

Second, solidarity among feminists of color suggests that the fragmentation criticism of intersectionality fails to reflect the actual experiences of women of color and other multiply-oppressed women. As examined earlier, the criticism presupposes the notion that identity is a fixed, static thing, like a pop-bead or some other pre-made/pre-given object, that stays the same whoever has it in whatever contexts. One implication of this pop-bead metaphysics is that two or more individuals have either totally identical or totally different identities. So, the criticism of intersectionality for fragmenting women unfolds as follows: Black women and Asian women have the same beads labeled “woman,” which are popped into two different beads labeled “Black” and “Asian” each and end up constituting two distinct necklaces (i.e., “Black woman” and “Asian woman”); this way, once race is factored in and the intersectionality of gender and race is considered, women are fragmented along racial lines into distinct—and virtually incommensurable—subgroups.

This is an incorrect understanding of identity and intersectionality. As the case here shows, identities and solidarities of women of color are not an either-or matter. That is, it is not the case that either Black and Asian women have the exact same identity as “woman” (and thus solidarity is possible) or they have completely different identities as “Black” and “Asian” (and thus solidarity is impossible). Rather, their solidarity becomes possible when they recognize tensions as well as similarities between Black and Asian communities within the oppressive structure of society and transform themselves. This is the process that Allison Weir calls “transformative identification.” Weir writes:

Transformative identification involves a recognition of the other that transforms our relation to each other, that shifts our relation from indifference to a recognition of interdependence. Thus identification with the other becomes not an act of recognizing that we are the same, or feeling the same as the other, or sharing the same experiences. . . . [Instead,] this kind of identification transforms our identities: through identification with the other we transform ourselves, and we construct a new “we”: a new identity. (Weir 2013: 78)

Weir discusses three kinds of identification that the process of transformative identification involves: identification with feminist ideals, identification with each other, and identification with feminists as a resistant “we” (2013: 68). In the case at hand, Black and Asian women create cross-racial solidarity by dedicating themselves to, or identifying with, critical race feminist ideals of challenging white supremacist capitalist heteropatriarchy. They identify with each other and identify with themselves as a “we,” that is, “sisters and siblings in the struggle” who fight together against intersectional oppression. Given that women of color are transforming themselves and constructing a new identity as a feminist “we,” the criticism that intersectional analyses and practices fragment women into smaller, mutually exclusive subgroups is misplaced.

3. Intersectional Feminist Theory as a Strong Non-Ideal Theory

3.1. Identity as a Fixed Thing, Identity as a Fluid Process, and Fragmentation

Thus far, I have explored some of the ways in which Asian identity is related to negative forms of power (such as systemic oppression) and to positive forms of power (such as solidarity and empowerment). I have identified and analyzed three types of identity-power relationships as exhibited in Asian women’s lives: (a) the manifestation of oppression in shaping the stereotypical meaning of identity, (b) the reproduction of oppression through the internalization of and conformity to this stereotype, and (c) the transformative resistance to oppression by reshaping identity as a starting point of solidarity praxis.

Taken together, the cases of Asian women’s experiences demonstrate that identity is “fluid and changing, always in the process of creating and being created by dynamics of power” (Cho, Crenshaw, & McCall 2013: 795, emphasis added):

The Asian-as-gender-backward, Asian-as-yellow-peril, and Asian-as-perpetual-foreigner identities are created by the power dynamics of intersecting oppressions, such as gender, race, xenophobic, and language-focused oppressions. That is, intersectional oppression is (a) manifested in creating derogatory identities.

By breaking the stereotypes and pejorative labeling, and redefining “Asian” as an identity with liberatory potential, Asian feminist and anti-racist movements create new positive forms of power such as resistance, solidarity, and empowerment. Their coalition-building with other feminists of color exemplifies (c) transformative resistance to the intersecting system of oppressions.

Located conceptually between the above two is (b) the reproduction of oppression, where identity is in the process of creating and being created by power. Some Asian women try to disassociate themselves from Asian womanhood defined in terms of patriarchy, by preferring white masculinity and denigrating Asian masculinity. This way, they rearrange the relationship between their identities and the power of patriarchy and create power as resistance. Yet, it is limited (as opposed to transformative) resistance, in that the negative connotation of Asian (Asian-as-inferior-to-white) is still created and maintained by the power of white supremacy. Similarly, some may say that Asians have gained some “power” by adopting the apolitical, assimilationist model minority identity and moving up the racial hierarchy. This power does not protect Asians from racism, as the model minority identity reproduces and is produced by the structural power of white racism.

I argue that, given this dynamic character of identity, the critiques of the alleged fragmentation of intersectionality are misplaced. As discussed earlier, the underlying assumption of the incommensurability critique and the infinite regress critique is that there is such a thing as static, unitary identity—for example, a fixed “Asian” identity that can break the identity of “women” into a smaller unified piece of identity of “Asian women.” To use the pop-bead metaphor, it is like the exact same objects (such as the beads of the same size, color, and material that are labeled “woman”) are distributed among 1000 people; out of those 1000 who have the same identity as “woman,” 50 people also possess another bead marked “Asian” which is clearly distinguished from the bead marked “Black”; and in the same way, this homogeneous group that has the “Asian” and “woman” identities can be divided again into smaller subgroups, according to what other fixed identities/entities such as “queer,” “heterosexual,” and “disabled” they have.

However, the concrete cases of Asian women’s experiences demonstrate that this view of identity is inadequate. Insofar as Asian identity is lived through the fluid process of meaning change, that Asian race and female gender are “intersecting” indicates that race and gender are experienced together as an interrelated, multilayered process in Asian women’s lives, rather than that Asian women are reified into one fixed intersectional location. The cases also illustrate that Asian women do not passively hold or possess their identity. In contrast, they navigate power dynamics and negotiate the relationship between power and identity in at least three different ways, by affecting and being affected by intersecting systems of oppression.

Critics might argue that this new picture of identity would exacerbate, not bring solutions to, the alleged fragmentation by intersectionality.7 The argument would proceed as follows: If Asian identity changes according to its relationship with power, doesn’t it mean that there are multiple Asian identities and corresponding (sub)groups of Asian? If so, aren’t Asians fragmented even more finely?

I maintain that this concern relies again on the metaphysical assumption of identity as a fixed thing. Only when identity is a fixed, internally homogeneous entity, the changeability of Asian identity would indicate that there are multiple Asian identities-as-entities, such as an object named Asian-as-yellow-peril, an object named Asian-as-model-minority, an object named Asian-as-critical-race-feminist, and so on. This view of identity does not properly capture Asian women’s diverse experiences of their Asian identities. Asian women do not switch meanings of their being Asian as though they switch the Asian-as-model-minority bead in their necklace to the Asian-as-critical-race-feminist bead.

That an Asian woman can resist (a) the xenophobic narrative that defines Asians as yellow perils, deconstruct (b) the meaning of Asian identity as a white assimilationist model minority, and create (c) a new definition of her being Asian as an important starting point of feminist/anti-racist solidarity does not mean that these three meanings of being Asian (i.e., “yellow peril,” “model minority,” and “critical race feminist”) exist as separate things. For, even a critical race feminist Asian woman who redefines her Asian identity as a positive one with transformative potential is likely to still face xenophobic racism in the US, and her having strived to fit the hard-working/apolitical model minority stereotype once may have affected her in many ways, including her critical awareness about this stereotype. In this sense, “yellow peril,” “model minority,” and “critical race feminist” are all part of Asian identity, that is, experiences that constitute what it means to be Asian in this specific socio-historical context of the current US society. Hence it is inadequate to divide Asian women into three discrete subgroups as if each Asian woman belonged to only one mode of being Asian. It is more adequate to understand these three meanings of Asian identity as interconnected nodes or dimensions of the multifaceted process of living as “Asian.” To put it more generally, women of color (and other multiply-oppressed subjects) are not fragmented into subgroups along the lines of different meanings of their racial identity (or other marginalized group identities); instead, they are situated within the process where they continuously move across different kinds of relationship between identity and power, and thereby experience their identity in diverse but interconnected ways.

3.2. Intersectional Feminist Theory as a Non-Ideal Theory in a Strong Sense

In this regard, the actual lived experiences of the multiply oppressed are the site at which the identity-power relationship is worked out. More specifically, the everyday lives of women and others facing multiple oppressions are the spaces in which the power dynamics of intersecting oppressions are manifested, reproduced, and resisted through the construction and reconstruction of identity. The raison d’être of contemporary feminist scholarship is that feminist theory should address how sexism works in mutually supporting ways with other forms of oppression rather than as a singular, pure form of oppression (see McCall 2005: 1779–80; Collins 2015: 2–3). For a theory to help us understand and challenge the workings of multiple, intersecting oppressions, it must pay attention to the space in which these oppressions actually work—that is, the actual daily lives of women of color, working-class women, women in the global South, queer, trans, and gender non-confirming people, and other multiply-oppressed groups.

It is in this sense that I suggest that intersectional feminist theory can be best understood as a type of non-ideal theory. Both intersectionality and non-ideal theory are much-discussed topics in feminist social and political philosophy, but the connection between the two has been less examined. To draw this connection, it is important first to explain what non-ideal theory is and how it has been employed in social and political philosophy. The term non-ideal theory was first popularized by John Rawls in A Theory of Justice (1971/rev. ed. 1999), where he divided his theory of justice into two parts: ideal and non-ideal. According to this distinction, ideal theory addresses the principles of justice that would govern a perfectly just society, in which “everyone is presumed to act justly and to do his [sic] part in upholding just institutions” (Rawls 1999: 8). Ideal theory, Rawls argues, provides guidance for non-ideal theory that addresses imperfect societies with injustice: once we have an ideal conception of justice in hand, we can judge existing unjust societies in light of how far they depart from the ideal justice. From this consideration, Rawls focuses on establishing principles that would regulate a hypothetical, ideally-just society, which he contends is of more fundamental importance than tackling sexism, racism, and other kinds of injustice in the current society (1999: §§2, 38–39, 59).

However, critical race and feminist philosophers have pointed out that merely applying the notion of ideal justice to problems of a non-ideal society is insufficient at best and ideological at worst. Charles Mills (1997; 2004; 2007) is one of those who have prompted the increasing discussion of non-ideal theory in the area of social/political philosophy. Mills explains that, whereas ideal theory “abstain[s] from theorizing about oppression and its consequences,” non-ideal theory “make[s] the dynamic of oppression central and theory guiding” (Mills 2004: 170, 177). Mills’s 2004 article is particularly notable for the argument that ideal theory is an ideology. By abstracting away from the actual workings of injustice, ideal theory falls into an ideology that can only reflect the interests of the privileged. For it is the privileged (especially white middle-class men) who experience “the least cognitive dissonance” between ideal and non-ideal worlds. They do not face discrimination and marginalization on the grounds of race, gender, and class, so their lives in the current unjust/non-ideal society are not very different from those in an ideal society that is free from oppression (Mills 2004: 166–70). Therefore, Mills points out that ideal theory does not provide guidance to address injustice and promote justice, but instead reinforces the oppressive status quo. Mills argues that it is non-ideal theory that helps us get closer to the ideal/non-oppressive society. By centering on, rather than setting aside, non-ideal/oppressive realities, non-ideal theory facilitates a clearer understanding of the structure of oppression that underlies the present social order. This way, non-ideal theory aids in challenging structural oppression and changing the social order to be closer to the ideally just (Mills 2004: 180; see also Khader 2018; Pateman & Mills 2007).

Lisa Tessman draws on Mills to further distinguish between two senses of non-ideal theory: a weak and a strong sense. In the introduction to the edited volume Feminist Ethics and Social and Political Philosophy: Theorizing the Non-Ideal (2009), Tessman stresses that the distance between an ideal/perfect society and a non-ideal/imperfect society is because of systemic oppression. The difference between the weak and strong non-ideal theories lies in the theory’s focus on this systemic injustice:

In a weak sense, simply employing a methodology of examining actual rather than counterfactual/hypothetical ideal(ized) worlds qualifies a work as an instance of non-ideal theory. But the essays in this volume, being feminist, qualify as non-ideal theory in a stronger sense as well: they not only examine and theorize actual lives, they focus on the lives of those who live under conditions that are particularly distant from the ideal (in the sense of perfect), a distance that is generated and sustained by systemic sources of injustice. While no one lives an ideal (in the sense of perfect) life or under ideal (in the sense of perfect) conditions, some people live worse or more difficult lives, and under worse or more difficult conditions, than others. Sometimes this is due to natural luck. Often, it is due to the injustices of domination and oppression. Developing theory that reflects the lives of women and others who face systemic injustice requires theory that is non-ideal(ized) in this stronger sense: it focuses on the actualities of people whose lives, through injustice, are kept distant from an ideal. (Tessman 2009: xviii, original emphasis)

Let us recall that Asian American women experience COVID-related anti-Asian incidents more often and in different ways than do Asian American men. Asian American women, in Tessman’s terms, live under conditions that are particularly distant from the ideal/perfect, a distance that is created and maintained by the systemic injustice of gendered xenophobic racism. This way, a social theory that focuses on the lives of multiply- and intersectionally-oppressed people qualifies as an instance of strong non-ideal theory explained by Tessman.

The distinction between strong and weak versions of non-ideal theory is also similar to the distinction between thick and thin case studies. According to Heidi Grasswick and Nancy McHugh, what is characteristic of the use of case studies by feminist and critical race philosophers is that these philosophers are committed to employing in their analyses “thickly described cases,” namely, “cases that focus on elements of marginalized and oppressed peoples’ experiences” (Grasswick & McHugh 2021: 15). Whereas thinly described cases, including hypothetical cases, are meant to provide more detail and concreteness than abstract theory so they can illustrate a philosophical point made by abstract philosophical methods, the point of using thickly described cases is not details per se. Rather, feminist and critical race philosophers employ thickly described cases in order to reveal the complexity of how injustices play out and develop potential solutions to conditions of injustice, by attending to the details of oppressed peoples’ lives (Grasswick & McHugh 2021: 14–17).

Echoing Tessman, Mills, Grasswick and McHugh, I define “strong non-ideal theory” as follows: it is a theory that, by focusing on the lives of the multiply oppressed, presents the intersecting dynamics of oppression as central and theory-guiding. I argue that intersectional feminist theory can be best explained as a non-ideal theory in this strong sense. Intersectional feminist theory seeks to foreground the lives of women and others who are multiply oppressed, that is, those who live under difficult, non-ideal conditions not because of mere luck but because sexism, racism, heterosexism, and other forms of oppression intersect and work together. In so doing, this theory facilitates the understanding and potential transformation of the oppressive social structure.

Intersectional feminist theory as a strong non-ideal theory differs from ideal theory like Rawls’s, which puts aside the actualities of oppressed people’s lives. It also differs from non-ideal theory in the weak sense, which addresses the actual/non-ideal as opposed to the hypothetical/ideal but fails to engage the lives of the multiply oppressed, and thus fails to show clearly how the intersecting system of oppression works. The critiques of intersectionality examined in this paper count as this kind of weak non-ideal theory. Of course, they are “non-ideal” theories in that they concern the actual/non-ideal. Unlike Rawlsian ideal theory that focuses exclusively on the hypothetical/perfectly-just world, the critiques of intersectionality address what might happen in the real/unjust world, for example, whether and to what extent intersectionality would fragment women and hinder feminist purposes. However, they are not non-ideal enough and are only weakly non-ideal, in that they focus too much on the abstract inquiry of how the intersection of race and gender would divide women along racial lines and too little on how such intersection is actually experienced in the lives of women of color. In contrast, implementing feminist theory in an intersectional manner indicates doing a stronger non-ideal theory, which attends to the detailed elements of the actual experiences of multiply-oppressed women and others, and by doing so, reveals how sexism operates in mutually constructing ways with other forms of oppression and helps to dismantle such intersecting structure of oppressions.

In this paper, I have discussed why intersectional feminist theory can best be understood as a non-ideal theory in the strong sense. I have attempted to provide an example of it, specifically an Asian American feminist theory that, by focusing on the actual lived experiences of Asian American women, presents the power dynamic of racism, sexism, xenophobia, and language-based oppression central and theory-guiding. When feminist theory foregrounds the actual locus at which the dynamic of intersecting oppressions is executed, navigated, and negotiated, it can better assist the comprehension of and resistance against oppressive dynamics.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Lisa Schwartzman and Robyn Bluhm for their valuable feedback and encouragement as I developed this article. An earlier version of the article was presented at the 2021 American Philosophical Association Pacific Division Meeting. I would like to thank Boram Jeong for providing insightful comments on my presentation there. I am also grateful to two anonymous reviewers and the area editor for their constructive feedback and suggestions.

Notes

- In Crenshaw’s groundbreaking works (1989; 1991), the term “intersectionality” was used to (i) criticize the marginalization of women of color within feminism and to (ii) demand a better recognition of particular contexts where women of color experience sexism, which are not the same as those of white women. Although the term intersectionality was invented by Crenshaw, these two main ideas, which I refer to as (i) anti-marginalization and (ii) difference-recognition, were not completely new. It is more correct to say that, as much of the recent intersectionality literature points out (see, e.g., Anthias 2013: 5; Collins 2015: 10; K. Davis 2008: 70–72; Gasdaglis & Madva 2020: 1290; McCall 2005: 1779–80; Nash 2008: 2–3; Ruíz 2018: 336–37), the neologism gave a name to a fundamental, pre-existing concern within feminist scholarship: Black feminists (e.g., Combahee River Collective 1977; A. Y. Davis 1981; Hull, Bell-Scott, & Smith 1982; hooks 1984; Lorde 1984; King 1988) and other critical race/decolonial feminists (e.g., Lugones & Spelman 1983; Spelman 1988; Mohanty 1988) had emphasized that the concept of “woman” was used in dominant Western feminist discourses in a way that falsely generalized the perspective of middle-class, heterosexual, Western women, while relegating women of color, working-class women, queers, and Two-Thirds World women as the “Other” (Heyes 2000: 54). That is, Black and decolonial feminists, as Jennifer Nash puts it, “destabilized the notion of a universal ‘woman’ without explicitly mobilizing the term ‘intersectionality’” (Nash 2008: 3). In this regard, these feminists can be called antecedents to intersectionality, or intersectional feminists broadly construed. ⮭

- For an overview of the critiques of intersectionality, see Carastathis (2016: Ch. 4), Tomlinson (2013), Carbado (2013: 812–16), Collins and Bilge (2016: 123–29), and Cho, Crenshaw, and McCall (2013: 787–88). ⮭

- In this paper, the term “Asian” will be used interchangeably with the term “Asian American” to mean Asian in the US. I will use these terms in their broadest sense to encompass diverse Asian populations in the US: Asians of different ethnicities (e.g., Chinese, Filipino, Indian, Vietnamese) and citizenship statuses (e.g., US citizen at birth, foreign-born/naturalized citizen, foreign-born/non-citizen) (U.S. Census Bureau 2019a; 2019b). I use the term to refer not only to US-born and immigrant Asians who identify themselves as “Asian American,” but also to Asians who do not identify so (i.e., those who identify as Asian immigrants in the US rather than as American). ⮭

- In this paper, I use the term “identities” to refer to social group identities such as race, gender, class, and other group identities. In particular, I focus on marginalized group identities, such as “Asian,” “Black,” and “woman.” I will argue that what each of these identities is itself depends on how it is related to power. For instance, a marginalized racial identity may have a negative connotation constructed by the power of oppression, as well as a positive connotation that marginalized group members create as they wield the power of resistance and solidarity. In this regard, the term “identity” will be used to indicate diverse lived experiences of being X (e.g., “Asian,” “Black,” “woman”), which include certain traits/stereotypes associated with the group (externally) as well as sources of resistance/solidarity through marginalized group members’ identification with social justice ideals and with each other (internally). As the paper proceeds, I will discuss this conception of “identification-with” developed by Allison Weir (2013) in more detail. In terms of group membership, I do not make a sharp distinction between externally ascribed membership and self-identified membership because (1) self-identification is a complex topic that is beyond the scope of this paper, and (2) whether someone is a member of a certain marginalized group does not always fit into either external ascription or self-identification. For example, as for a biracial or multiracial person, whether they live as, feel like, belong to, or fit into “Asian,” “Black,” and so on is related to both how others and the society identify them and how they identify themselves. Similarly, an immigrant Mexican woman in the US may or may not have “Mexican American” identity, which is a complicated combination of her self-identification, xenophobic/anti-immigrant oppression in the US, and communities surrounding her in both Mexico and the US. Thus, I will use the term “identity” in a way that it covers these diverse relationships and experiences of living with a marginalized group identity, instead of limiting it to its one dimension. ⮭

- Iris Marion Young is one of the first contemporary philosophers who theorized oppression as a structural concept. In Justice and the Politics of Difference (1990), Young famously argues that oppressed groups, such as women and/or people of color, suffer injustice not as a result of “a few bad apples” but as a result of the “normal” process (e.g., cultural, political, and economic institutions) of a well-intentioned society. Oppression in this sense is structural: it exists as an established social structure and system, rather than as a mere individual moral deviation (Young 1990: 40–42, 61–63). Along with many other feminist philosophers, Amy Allen agrees with this idea of oppression being structural. Allen, however, claims that Young’s analysis provides an incomplete conception of power, in that it equates the term power only with structural oppression and fails to conceptualize individual and collective empowerment as modes of power. Allen proposes a new feminist conception of power that encompasses and distinguishes three modes of power: power-over (oppression/domination), power-to (individual empowerment/resistance), and power-with (collective empowerment/solidarity) (Allen 1999: Ch. 5; 2008). In this paper, the term power is used in line with Allen’s conception. By the “negative” form of power, I refer to what Allen calls power-over, which corresponds to Young’s notion of structural oppression. I use the term “positive” form of power in a broad sense that includes diverse modalities of power opposing structural oppression: resistance, solidarity, and individual and collective empowerment (i.e., both power-to and power-with). ⮭

- Kim found a pattern in the interviews that the women conflated “American” and “white” when they reflected on gender (Kim 2006: 525, 530; see also Chou & Feagin 2015: 161–66). ⮭

- I thank an anonymous reviewer for asking me to address this point. ⮭

References

1 AAJA MediaWatch Committee (2020, February 13). AAJA Calls on News Organizations to Exercise Care in Coverage of the Coronavirus Outbreak. Asian American Journalists Association. Retrieved from https://aaja.org/2020/02/13/aaja-calls-on-news-organizations-to-exercise-care-in-coverage-of-the-coronavirus-outbreak/

2 Allen, Amy (1999). The Power of Feminist Theory: Domination, Resistance, Solidarity. Westview Press.

3 Allen, Amy (2008). Power and the Politics of Difference: Oppression, Empowerment, and Transnational Justice. Hypatia, 23(3), 156–72.

4 Anthias, Floya (2013). Intersectional What? Social Divisions, Intersectionality and Levels of Analysis. Ethnicities, 13(1), 3–19.

5 Asians4BlackLives (2020, June 1). Asians 4 Black Lives: Uplift Black Resistance, Help Build Black Power [Tumblr post]. Retrieved from https://a4bl.tumblr.com/post/619777369649102848/asians-4-black-lives-uplift-black-resistance

6 Berdahl, Jennifer L. and Ji-A Min (2012). Prescriptive Stereotypes and Workplace Consequences for East Asians in North America. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 18(2), 141–52.

7 Black Women Radicals and Asian American Feminist Collective (2020a). Black and Asian-American Feminist Solidarities: A Reading List. Retrieved from https://www.blackwomenradicals.com/blog-feed/black-and-asian-feminist-solidarities-a-reading-list

8 Black Women Radicals and Asian American Feminist Collective (2020b). Sisters and Siblings in the Struggle. Retrieved from https://aaww.org/sisters-and-siblings-in-the-struggle/

9 Carastathis, Anna (2016). Intersectionality: Origins, Contestations, Horizons. University of Nebraska Press.

10 Carbado, Devon W. (2013). Colorblind Intersectionality. Signs, 38(4), 811–45.

11 Cho, Sumi, Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, and Leslie McCall (2013). Toward a Field of Intersectionality Studies: Theory, Applications, and Praxis. Signs, 38(4), 785–810.

12 Chou, Rosalind S. and Joe R. Feagin (2015). Myth of the Model Minority: Asian Americans Facing Racism (2nd ed.). Routledge.

13 Chu, Jon M. (Director) (2018). Crazy Rich Asians [Film]. Warner Bros. Pictures.

14 Chun, Jennifer Jihye, George Lipsitz, and Young Shin (2013). Intersectionality as a Social Movement Strategy: Asian Immigrant Women Advocates. Signs, 38(4), 917–40.

15 Collins, Patricia Hill (2015). Intersectionality’s Definitional Dilemmas. Annual Review of Sociology, 41, 1–20.

16 Collins, Patricia Hill and Sirma Bilge (2016). Intersectionality. Polity Press.

17 Combahee River Collective (2000). The Combahee River Statement [1977]. In Barbara Smith (Ed.), Home Girls: A Black Feminist Anthology (264–74). Rutgers University Press.

18 Cowan, Jill (2021, February 12). A Tense Lunar New Year for the Bay Area after Attacks on Asian-Americans. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/12/us/asian-american-racism.html

19 Crenshaw, Kimberlé (1989). Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 139–67.

20 Crenshaw, Kimberlé (1991). Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–99.

21 Davis, Angela Y. (1981). Women, Race & Class (1st ed.). Random House.

22 Davis, Kathy (2008). Intersectionality as Buzzword: A Sociology of Science Perspective on What Makes a Feminist Theory Successful. Feminist Theory, 9(1), 67–85.

23 Di Stefano, Christine (1988). Dilemmas of Difference: Feminism, Modernity, and Postmodernism. Women & Politics, 8(3–4), 1–24.

24 Ehrenreich, Nancy (2002). Subordination and Symbiosis: Mechanisms of Mutual Support between Subordinating Systems. UMKC Law Review, 71, 251–324.

25 Frye, Marilyn (1983). The Politics of Reality: Essays in Feminist Theory. Crossing Press.

26 Fujiwara, Lynn and Shireen Roshanravan (Eds.) (2018). Asian American Feminisms and Women of Color Politics. University of Washington Press.

27 Gasdaglis, Katherine and Alex Madva (2020). Intersectionality as a Regulative Ideal. Ergo, 6(44), 1287–30.

28 Grasswick, Heidi and Nancy Arden McHugh (2021). Making the Case: Feminist and Critical Race Philosophers Engage Case Studies. SUNY Press.

29 Heyes, Cressida (2000). Line Drawings: Defining Women through Feminist Practice. Cornell University Press.

30 hooks, bell (1984). Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center. South End Press.

31 Huang, Josie (2020, October 8). As Trump Blames ‘the Chinese Virus,’ These Asian American Women Won’t Stand for the Racism. LAist. Retrieved from https://laist.com/2020/10/08/trump-coronavirus-racist-asian-american-women-la-fight-back.php

32 Hull, Akasha Gloria, Patricia Bell-Scott, and Barbara Smith (1982). All the Women Are White, All the Blacks Are Men, but Some of Us Are Brave: Black Women’s Studies. Feminist Press.

33 Itkowitz, Colby (2020, June 23). Trump Again Uses Racially Insensitive Term to Describe Coronavirus. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/trump-again-uses-kung-flu-to-describe-coronavirus/2020/06/23/0ab5a8d8-b5a9-11ea-aca5-ebb63d27e1ff_story.html

34 Jackson, Chris, Jennifer Berg, and Jinhee Yi (2020, April 28). New Center for Public Integrity/Ipsos Poll Finds Most Americans Say the Coronavirus Pandemic Is a Natural Disaster: Three in Ten Americans Blame China or Chinese People for the Pandemic. Retrieved from https://www.ipsos.com/en-us/news-polls/center-for-public-integrity-poll-2020

35 Khader, Serene J. (2018). Decolonizing Universalism: A Transnational Feminist Ethic. Oxford University Press.

36 Kim, Nadia Y. (2006). “Patriarchy Is So Third World”: Korean Immigrant Women and “Migrating” White Western Masculinity. Social Problems, 53(4), 519–36.

37 King, Deborah K. (1988). Multiple Jeopardy, Multiple Consciousness: The Context of a Black Feminist Ideology. Signs, 14(1), 42–72.

38 Lim, Esther Young (2020). How to Report a Hate Crime. Retrieved from https://www.hatecrimebook.com/work

39 Lippi-Green, Rosina (2012). English with an Accent: Language, Ideology and Discrimination in the United States (2nd ed.). Routledge.

40 Lorde, Audre (1984). Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. Crossing Press.

41 Lu, Wendy (2020, March 31). This Is What It’s Like to Be an Asian Woman in the Age of the Coronavirus. The Huffington Post. Retrieved from https://www.huffpost.com/entry/asian-women-racism-coronavirus_n_5e822d41c5b66ea70fda8051

42 Lugones, María and Elizabeth Spelman (1983). Have We Got a Theory for You! Feminist Theory, Cultural Imperialism and the Demand for ‘the Woman’s Voice’. Women’s Studies International Forum, 6(6), 573–81.

43 May, Vivian M. (2015). Pursuing Intersectionality, Unsettling Dominant Imaginaries. Routledge.

44 McCall, Leslie (2005). The Complexity of Intersectionality. Signs, 30(3), 1771–800.

45 Mills, Charles W. (1997). The Racial Contract. Cornell University Press.

46 Mills, Charles W. (2004). ‘Ideal Theory’ as Ideology. In Peggy DesAutels and Margaret Urban Walker (Eds.), Moral Psychology: Feminist Ethics and Social Theory (163–81). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

47 Mills, Charles W. (2007). Intersecting Contracts. In Carole Pateman and Charles W. Mills (Eds.), Contract and Domination (165–99). Polity.

48 Mohanty, Chandra Talpade (1988). Under Western Eyes: Feminist Scholarship and Colonial Discourses. Feminist Review, 30, 61–88.