If I see, hear, or touch a sparrow, the sparrow seems real to me. Unlike Bigfoot or Santa Claus, it seems to exist; I will therefore judge that it does indeed exist. The “sense of existence” (SE) refers to the kind of awareness that typically grounds such ordinary judgments of existence or “reality.” The sense of existence has been invoked by Humeans, Kantians, Ideologists, and the phenomenological tradition to make substantial philosophical claims. However, it is extremely controversial; its very existence has been called into question. This paper aims to clarify the nature and reality of the sense of existence by studying a psychiatric condition in which the sense appears to be disrupted: depersonalization disorder (DPD).

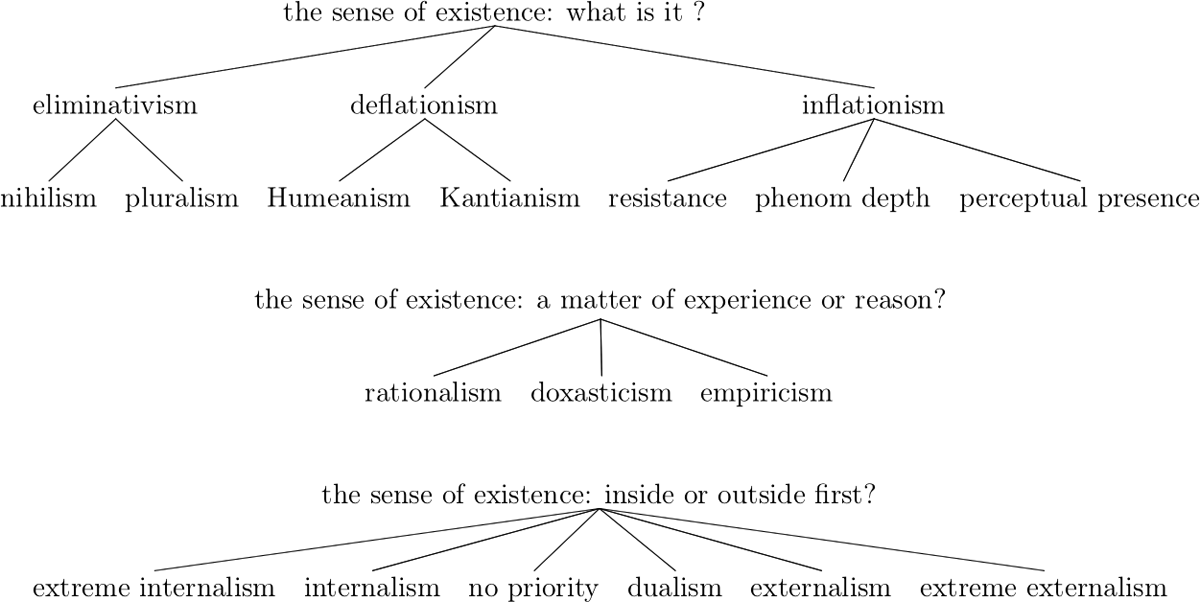

After some terminological preliminaries (§1), I will map the philosophical debates concerning SE (§2, see figure 1). This mapping is particularly important because debates on the topic are found among very different traditions and sub-fields; they often use confusingly different terminology. For the sake of simplicity, I will focus on what I take to be the most influential views on SE in the literature. I will then present different sources of empirical data that can be adduced to settle these debates (§§3–4). DPD is probably the most fecund out of these sources, I will argue. Finally, I will argue that DPD refutes these “dominant” theories of SE (§§5–6). However, I will propose that it might vindicate a couple of much less popular theories (§7).

I use “to exist” and “to be real” as synonymous throughout this paper. To talk about existence as a property of particulars (i.e., as something that can be attributed to particulars as opposed to something that can only be attributed to properties) might make some philosophers nervous. Frege (1980) and Russell (2009) have convinced many people that while we can say that roses exist, to mean that the general property of being a rose is instantiated, it does not make sense to say of a particular rose that it exists. Talk of a particular “being real,” might by contrast seem closer to ordinary language and thus more innocuous. I have four reasons for retaining the expression “sense of existence” instead of using the more common “sense of reality”: (i) “to exist” is one meaning of “to be real”; (ii) major philosophers such as Hume, Kant, Maine de Biran, and James have discussed SE using this or similar expressions (“idea of existence,” “feeling of existence,” “sentiment de l’existence”), often in order to argue about the very property of existence;1 (iii) “sense of reality” is now slightly misleading: it has been widely used to refer to phenomena that (I shall argue) are only loosely connected to existence, such as the sense of perceptual presence. (iv) Finally, it is not clear to me that we are ordinarily less prone to talk about the existence of particulars than of their being real. Think, for example, of the debates about the existence of particulars such as God, Bigfoot, or Jesus. This point about ordinary language suggests that existence at least seems to be a property of particulars and that the talk of a sense of existence for particulars makes sense prima facie, which is all we will need.

As might already be clear, I will call “property of a particular”, or simply “property”, anything that can be attributed to a particular by a predicate.2 I will exclusively focus on SE regarding (non-dependent) particulars (I will omit “non-dependent” in what follows). We may also have a SE regarding universals or dependent particulars (tropes), but I will not discuss these in this paper.

Finally, it will be useful to introduce a notion that might, on certain theories, be weaker than existence: the notion of being. It is extremely tempting to say that there are things, such as Pegasus, that do not exist. If we call “being” the property of falling within the range of the universal quantifier, it is extremely tempting to infer, then, that there are things, such as Pegasus, that have being even though they do not exist. Meinongians are famous for giving way to such a temptation while their opponents argue that everything exists (or, equivalently, that nothing fails to exist) so that being entails existence.3

1. Defining SE

I have said that SE is the kind of awareness that grounds our judgments of existence or reality. This definition is an approximation at best. First, there may be different kinds of awareness that are grounded on each other and which together ground our judgments of existence. For instance, we might have an implicit and pre-reflective awareness of existence that grounds a more explicit awareness; this more explicit awareness might in turn ground our beliefs and judgments of existence. In such a case, we can set aside the derived forms of awareness and focus on the most fundamental. We would thus define SE as follows:

The sense of existence (SE): The sense of existence is the most fundamental kind of awareness (if any) that grounds our judgments of existence.

If it exists, SE probably justifies some of our judgments of existence; it might also fix the meaning of our use of “existence.” However, I have defined SE in terms of awareness (phenomenology) rather than justification (epistemology) or meaning-fixation (semantics). These distinctions are important because our judgments of existence are frequently justified by judgments of plausibility, which are largely independent of SE (as I have defined it). I may judge that the monster I seem to see in Loch Ness, for which I have a certain SE, does not really exist: I believe that such a thing cannot exist, and I know that I took hallucinogenic drugs ten minutes ago. Conversely, I can be justified in believing that Pope Francis exists even though I have never seen him and I have no SE regarding him.

2. Mapping the SE Debates

If I try to discover the features of my perceptual experience in virtue of which the sparrow I am watching seems real to me, I may be disappointed. My experience seems to tell me how the sparrow is, not that it is real. In this respect, existence awareness seems to be quite unlike color awareness or shape awareness. There does not seem to be a specific experiential feature associated with existence. We might accordingly assign SE a further feature:

Elusiveness: SE (if there is such a thing) is elusive.

2.1. Eliminativism I: Nihilism

If we can’t find existence in our experiences, this may be because there is no such thing as existence awareness. The simplest reaction to SE’s elusive character is simply to deny that we possess SE at all. Let us call this position “nihilist eliminativism.” Many philosophers have argued that existence is not a property (of particulars), most notably Brentano (2014: 161–62), Frege (1980: 65), and Russell (2009).4 There is a close connection between this claim and the claim that there is no SE: assuming that our experience is not systematically misleading (a form of “phenomenal conservatism”), the latter claim seems to entail the former. However, I am not aware of any philosopher who explicitly endorses a nihilist form of eliminativism about SE.5

2.2. Eliminativism II: Pluralism

A more common view denies that SE exists, not because there is no awareness of existence for particulars but because this awareness is fragmented into different, equally fundamental forms. For the pluralist, SE is elusive because there are many senses of existence. Pluralism regarding SE is an important stance; it was arguably endorsed by Heidegger (1927/1996), who defended pluralism about existence on phenomenological grounds. According to Heidegger, things that seem to exist seem to exist in very different ways or “modes”. Tools seem to exist by being “ready-to-hand” (very roughly: available for being used by us), scientific entities and mere quantities of matter seem to exist by being “present-at-end” (very roughly: available for being observed and studied scientifically), and we seem to exist in an altogether different and sui-generis way which he calls “Dasein”.6 Pluralism about SE has also been defended quite recently by Fortier on anthropological and neuroscientific (rather than phenomenological) grounds (2018). To articulate the pluralist view about SE more precisely, we should define the following.

A relatively fundamental existence awareness: A kind of existence awareness is relatively fundamental if it is not grounded on other kinds of existence awareness.

Pluralism is the claim that there is more than one relatively fundamental existence awareness. In what follows, I will suppose that pluralism is false for the sake of simplicity. However, I will assess it briefly near the end of the paper (§8).

2.3. Deflationist Views

Researchers who see SE’s elusiveness as a reason for being circumspect about it do not usually deny its reality. They instead claim that it does not add anything to our awareness of particulars, or equivalently, that is not a separable feature of our awareness of particulars. We can call this view deflationist. Deflationists can merely claim that SE is a necessary aspect of our awareness of particulars. A more interesting kind of deflationism will provide a genuine theory of SE, however, claiming that it is or at least reduces to our awareness of particulars. According to this last kind of deflationism, we find SE elusive because we look for certain things in our awareness of particulars, instead of simply looking at this awareness. Deflationists are all committed to the thesis that existence awareness and SE are ubiquitous.

Universal necessity of existence awareness: One cannot be aware of something without being aware of it as existing.

Hume claims that,

The idea of existence [. . .] is the very same with the idea of what we conceive to be existent. To reflect on any thing simply, and to reflect on it as existent, are nothing different from each other. That idea, when conjoined with the idea of any object, makes no addition to it. (THN 1.2.6)

Hume is therefore a deflationist.7

2.4. Empiricism and Rationalism about SE

Hume is also an empiricist in that he believes SE to be a matter of experience. According to him, SE reduces to our experiences of particulars. By contrast, Descartes and other modern proponents of the ontological argument for the existence of God believe that at least for some particulars (God, maybe some mathematical entities), SE can be construed on the model of rational insight rather than perception.

Kant arguably shares Hume’s deflationism (A599–600/B627–28):

[. . .] when I think a thing, through whichever and however many predicates I like (even in its complete determination), not the least bit gets added to the thing when I posit in addition that this thing is. (B628)

He also believes that no existence claim can be deduced from the concept of a particular. However, he considers the attribution of existence to depend (partly but decisively) on synthetic a priori insights (A225/B273). He thus takes SE to be (partly but decisively) a matter of rationality. We can therefore say that he is a deflationist and rationalist about SE.

Kant’s precise view of existence and SE is notoriously hard to fathom, let alone reconstruct. Drawing on Stang’s (2015; 2016) astute interpretation, and using our modern terminology, I would say that for Kant the anti-Meinongian claim that everything exists (i.e., that being entails existence) is a priori true, which entails that I cannot be rational and be aware of something without being aware of that thing as existing.8

2.5. Doxasticism

The empiricism/rationalism distinction is orthogonal to the deflationism/non-deflationism distinction. Moreover, the former distinction does not partition views on SE. Some researchers deny that SE is grounded on experience or rationality; they instead invoke habits or beliefs. Farkas (2014) has recently defended this stance, which we can call “doxasticism”. She argues, after reviewing the psychiatric literature on hallucinations, that there is no necessary and sufficient experiential condition for the sense of reality. Although it can be reinforced by aspects of our experience, the sense of reality ultimately hinges on what the subject believes to exist—on “the whole nexus of the subject’s beliefs.”9

2.6. The Variety of “Inflationist” Views

Both the rationalist and empiricist versions of deflationism may initially appear implausible. I do not seem to have a sense of reality regarding particulars I merely imagine (as opposed to those I perceive or remember), but the deflationist seems committed to claiming that I do. For him, any awareness of particular must come with SE. This objection is not fatal, however. The phenomenology of the imagination is unclear; some authors, such as James (1890: XXI), have argued that the imagination endows a sense of existence on the particulars it conjures up.10

In any case, this objection has probably led many philosophers to believe that specific aspects of experience can be dissociated from our awareness of particulars, and that these aspects ground our awareness of existence. This belief emerges most strongly in the sentimentalist francophone tradition for which the “feeling of existence” (sentiment d’existence) is of central philosophical importance. The sentimentalist tradition probably originates with Malebranche; it also includes Rousseau (1992a; 1992b), the Encyclopedists (see the entry on “Existence” in Diderot and d’Alembert 1778), the Ideologists (Condillac 1754/1997; Destutt de Tracy 1800; Maine de Biran 1981), and their physiologist peers (Cabanis, Bichat).11 This non-deflationist or “inflationist” belief (as Deflationists might want to call it) is also common among many thinkers whose stance on SE may have been influenced by the sentimentalist tradition (Schopenhauer 1969: §17; Théodule Ribot 1885; James 1890: XXI; Bergson 1896/1912; Dilthey 1883; Henry 2011), and many phenomenologists (Husserl 2013a; 2013b; Henry 2011 again). These thinkers all ground SE in some interoceptive aspects of experience, or other aspects (agentive or affective) that are not purely sensory. They can explain SE’s elusive character by claiming that these aspects of experience are themselves elusive and often overlooked.

Before elaborating on (what I take to be) the most popular inflationist accounts of SE, it is important to distinguish between the different tasks that such accounts must undertake. An inflationist theory of SE should obviously show that a certain, separable aspect of experience constitutes SE. We could imagine a purely empirical (psychological, neurophysiological, or even introspective) justification for the latter claim. We might thus imagine demonstrating through introspection or neurophysiological measures the existence of aspect A, such that someone’s experience will have A only when they are disposed to judge that something really exists. However, this kind of empirical justification would leave pending a conceptual or philosophical question that we need to answer if we want our theory to be genuinely illuminating. This question regards the connection between the specified aspect of experience and existence.

The connection question for an inflationist theory of SE: What connects this aspect of experience to existence? What grounds the fact that experiences with this aspect constitute the sense of existence, rather than, say, of beauty, flashy colors or triangularity?

Strictly speaking, in order to answer the connection question, one will need to explain why this aspect of experience concerns apparent existence rather than beauty, flashy colors, or triangularity. And for that, one will have to refer to the phenomenology or “folk psychology” of existence, that is, to the way we spontaneously apprehend it. However, classical philosophers usually assume that SE is reliable (i.e., apparent existence reliably tracks existence), so in order to answer the connection question, they only need to explain why this aspect of experience concerns existence (as opposed to apparent existence). And they can do that by invoking claims about what exists and what existence is (as opposed to claims about the phenomenology or the folk psychology of existence).

The following analogy can help us understand this point as well as the significance of the connection question. Suppose a theory purports to explain our awareness of the color blue by claiming that it is grounded in a certain aspect of experience (characterized, say, by a particular quale and a particular pattern in the primary visual cortex). If the theory were merely justified by the fact that this aspect of experience is correlated to subjects’ tendency to judge that there are blue things in their visual environment, it would be very disappointing. To be really illuminating, such a theory should explain what connects this aspect of experience to the color blue, and why it is connected to this color rather than to beauty, yellow squares, or hills. The answer to this “connection question” will depend on one’s theory of colors; it must involve some philosophical theorizing. A physicalist who identifies colors with sets of reflectances will typically argue that these experiences reliably track a certain set of reflectances in normal conditions, and that these reflectances define blue objects. A dispositionalist will connect the color blue and experiences having this aspect by claiming that the color blue is simply defined by the fact that blue things elicit such experiences (associated, remember, with a tendency to judge that there are blue things in the visual environment). Both the physicalist and the dispositionalist assume that our sense of the color blue is reliable. As for the eliminativist, she will claim that there really are no blue things—but only things that seem to be blue—and that our sense of the color blue is accordingly not reliable at all. She will however claim that this aspect of experience trivially tracks things that elicit this aspect of experience, which are exactly the things that seem to us to be blue.

It is important to answer the connection question if we want a theory of SE to be really enlightening. It provides what we might call a philosophical or conceptual (as opposed to merely empirical) justification for a theory of SE. Unfortunately, inflationist theories of SE often leave their answers to the question rather implicit. I will try to make them explicit in what follows.

I will now present what seems to me to be the most influential current inflationist theories. They are neither exhaustive nor exclusive of each other. However, they and their motivations are at least prima facie distinct; it is important to get their differences clear. As I have noted, terminology remains unsettled; many authors use “reality,” “presence,” “real presence,” or “existence” interchangeably. This sometimes renders it unclear whether they are analyzing the sense of reality in terms of something prima facie different such as presence, or simply referring to something else.

2.6.1. Resistance and Effort

When we doubt whether something is real, we may—like Doubting Thomas—touch it to check. Such behavior has significant implications, according to an influential view traceable back to the Greek atomists and developed by Ideologists such as Condillac (1754/1997), Destutt de Tracy (1800), and Maine de Biran (1812/1981).12 On this view, the sense of reality equates to the sense of resistance. The sense of resistance is paradigmatically triggered by effortful, “active touch” (Massin & Vignemont 2020). According to resistance theories, “to resist [. . .] is to exist” (Destutt de Tracy 1800).13 Current advocates of these theories include Ratcliffe (2013) and Massin (2011).

Ideologists conceptually justify the resistance account of SE as follows: (i) something is real, in one sense of the term, if it is independent of my will; (ii) resistance is a mark of volitional independence. On some versions of this view, such as Maine de Biran’s, this criterion of reality does not apply to the will itself. The will is real without being independent of the will, and its reality is manifested by our felt efforts. Another conceptual justification of the resistance account is based on the claims that (i) to be real is to be causally efficient (sometimes called Alexander’s dictum14) and (ii) resistance and effort are symptoms (and sometimes even direct perceptions) of causal efficacy (Armstrong 1997). Resistance theory does not imply that our awareness of existence or reality is limited to touchable objects. The sense of existence is only the fundamental ground of our judgments of existence. However, active touch and feelings of resistance can ground our judgments of reality in complicated ways. I may be aware of the reality of a given object by being aware that it would resist if I touched it. This kind of awareness arguably depends on a peculiar form of tactile sensation elicited by vision, especially by close “peripersonal vision” (Vignemont 2021).

2.6.2. Phenomenological Depth

When I see an opaque cube, I am not only aware of its proximal faces in front of me. I am also aware of its hidden faces. I would be surprised to discover that what seemed to be a cube was in fact flat on the other side. Gestalt psychologists term this phenomenon “amodal completion”; modern philosophers sometimes call it “presence” or “real presence.” As I will explain later, I prefer to avoid these terms. Instead, I refer to a sense of “phenomenological depth.” This is the sense that an object will appear in a certain way if I move around it (where the way it will appear depends on the kind of object it is). The sense of phenomenological depth has long fascinated philosophers: it appears to be an awareness of the fact that a perceived object outstrips what I directly or proximally perceive of it. Therefore, it seems to be an awareness of the fact that the object is independent of what I directly perceive of it. There moreover seems to be a sense in which “to be real” is simply to be independent of my awareness; this provides both an answer to the connection question and a conceptual justification for the theory. The sense of phenomenological depth might accordingly seem to be a good candidate for SE, and this is indeed a widespread theory. Many philosophers who endorse this view of SE also consider phenomenological depth to be a perceptual phenomenon grounded on sensorimotor abilities—more specifically in perceptual expectations (Noë 2005; Siegel 2011: VII); this is how I understand Husserl’s notion of appräsentation (2013a; 2013b).15

2.6.3. Perceptual Presence

When I regard a painting that depicts Saint George and the dragon, the painting’s frame and colors seem real in a way that George and the dragon do not. They seem real in the sense that they seem to belong to real space: the three-dimensional manifold where I also happen to be standing. We can refer to this sense that something is spatially related to me as the “sense of perceptual presence.” This theory’s conceptual justification might be that “to be real” is to belong to the same spatial manifold as I do. Many people seem to assume that the sense of perceptual presence is identical to the sense of phenomenological depth. The two senses are conceptually distinct, however. We might imagine a creature that has a sense of presence regarding ordinary objects but possesses no expectations about their hidden parts and no sense of phenomenological depth whatsoever. The two senses might even come apart in real life (as opposed to in merely imaginary cases). When I stand in front of a trompe l’œil that represents an apple, the apple phenomenally seems to be present. However, it is not clear that it seems to have phenomenological depth; I would not be surprised if I moved around and failed to see the back of an apple.16

Matthen (2005; 2010) has developed an influential perceptual presence theory of SE. According to him, the sense of perceptual presence depends on the subject’s sensorimotor abilities. Moreover, it is implemented in the assertive mode rather than in the content of perception:

Visual experiences have imagistic content. Real existence cannot be asserted by imagistic content. Normal scene-vision, however, does assert real existence [. . .] Hence, there is a semantically significant component of visual experience that is distinct from its imagistic content. This is the Feeling of Presence. I conjecture that the Feeling of Presence arises out of a visually guided but non-descriptive (i.e., non-conscious, unstored, unrecallable) capacity for bodily interaction with external objects. (Matthen 2010)

2.7. Internalism and Externalism about SE

Before moving on, I will introduce some additional distinctions to help us assess theories of SE. The classical Biranian resistance theory has a dual nature: it accounts differently for the existence of inner, mental things (manifested by effort) and outer, non-mental things (manifested by resistance). As Descartes (1985: 59) and Hume (1740/1978: 236) note, our experiences themselves (as opposed to their contents) have no spatial phenomenology. However, the sense of presence and the sense of phenomenological depth are distinctively spatial. It is therefore not clear whether it is coherent to attribute a sense of perceptual presence or phenomenological depth to our own experiences. If the sense of reality is the sense of presence or phenomenological depth, maybe we should conclude that our experiences are not subject to the sense of reality! Some authors appear committed to the claim that inner, subjective, and private mental objects such as experiences do not possess a sense of reality, or that their sense of reality is somehow diminished.17 For Farkas (2014), it is fundamental for x’s sense of reality that x seems able to exist without being experienced. This stance seems to exclude the possibility of a sense of reality attributable to experiences themselves.

The idea that experiences feel unreal is extremely implausible—the example of intense pain offers an excellent counterexample. I am unsure whether these authors really wish to make a substantial claim in this regard; I am also unsure if they are deliberately committed to the unreality of experience. In any case, I will refer to the claim that the sense of reality for subjective, private mental objects is attenuated or non-existent as “extreme externalism about SE.”18 We might likewise term “extreme internalism about SE” the claim that outer objects come with less or no sense of reality. Idealists are (trivially) extreme Internalists, but there are others.19

A more plausible theory—Cartesian in spirit—holds that our awareness of existence regarding inner things (such as sensations, experiences, or oneself) differs in kind from that regarding outer things and that the latter is grounded on the former. We can simply call this position “internalism” regarding SE; it is espoused by most of the aforementioned French sentimentalists. Rousseau (1992a: 44) claims that “man’s first feeling was that of his own existence”; he is explicit that this ontogenetic priority reflects an ontological priority. James also endorses internalism: “The fons et origo of all reality [. . .] is thus subjective, is ourselves” (1890: XXI). Internalism has also been advocated by some phenomenologists, such as the early Jaspers (1997: 94) and Michel Henry (1985; 1990; 2011).20

At the other end of the spectrum, some authors claim that our awareness of existence regarding outer things is primary. This position, which we can call “externalism,” is probably influenced by Kant’s “refutation of idealism” (B274–79). Externalism is espoused by Wilhelm Dilthey (1883: 1:128), who argues that the sense of reality regarding outer things indirectly explains one’s own sense of reality.21

Several stances exist between externalism and internalism. These include the view that our awareness of internal and external things are equally fundamental; this is a form of dualism regarding SE. We can also find the claim, seemingly endorsed by Varga (2012) and attributed by him to Jaspers (1913/1962: 94–95) and Blankenburg (1971: 2), that the two forms of awareness are identical. We can call the latter claim “the identity view” of SE.

3. Depersonalization Disorder (DPD) and SE

It is difficult to arbitrate between the theories of SE hitherto presented. The phenomenology of SE is elusive; most theories are backed up by conceptual arguments that are (at least prima facie) compelling. However, at least two bundles of empirical evidence have been adduced to assess the reality and the nature of SE.22

The first bundle of evidence is drawn from cases that appear to be explained best by a “hypertrophy” of SE (cases of false positives): hallucinations. It has frequently been observed that the phenomenological difference between hallucinations and ordinary perceptions can be hard to identify. It seems that hallucinations can be much less vivid and precise than ordinary perceptions, even lacking any clear sensory element, but can nevertheless present their object as fully real. As noted by James,

It often happens that a hallucination is imperfectly developed: the person affected will feel a “presence” in the room, definitely localized, facing in one particular way, real in the most emphatic sense of the word, often coming suddenly, and as suddenly gone; and yet neither seen, heard, touched, nor cognized in any of the usual “sensible” ways. (James 1985: III)

Conversely, forms of mental imagery called pseudo-hallucinations (Kandinski 1885) do not seem to present their objects as real even though they are extremely vivid, precise, and involuntary. The best explanation of the phenomenological differences between hallucinations, perceptions, and imagery should arguably invoke SE; this is an argument against eliminativism. James indeed takes hallucinations to be “the most curious proofs of the existence of [. . .] an undifferentiated [and non-sensory] sense of reality” (James 1985: III). More recently, hallucinations have been used as a probe for SE (or perceptual presence) by Dokic and Martin (2012; 2017), Farkas (2014), Dokic (2016), and Riccardi (2019).

A strategy reliant on hallucinations has certain drawbacks. One such drawback is that even if we have well-developed neurocognitive theories of the formation of (certain types) of complex hallucinations (see Collerton et al. 2005 and Allen et al. 2008), such theories are mostly interested in explaining how complex visions can arise in the absence of the relevant stimuli. They are far less interested in explaining the difference between hallucinations (hallucinations with SE) and pseudo-hallucinations (hallucinations without SE) and are accordingly of little help in understanding the nature of SE.

Another well-studied condition can not only confirm the reality of SE but also help us settle many of the disputes concerning its nature. This condition has been called “depersonalization,” “depersonalization disorder (DPD)” (in the DSM-V), or “depersonalization-derealization syndrome” (in the ICD-10). DPD patients typically complain that many things no longer seem to be real. Early clinicians hypothesized that DPD involves a lack of “awareness of reality” (Krishaber 1873), “perception of reality,” “function of reality” (Janet 1903: 1:443–44), or “feeling of reality” (Krishaber 1873: 47; Janet 1903: 1:443). The psychologist and philosopher Pierre Janet explains:23

In one word, patients keep a normal perception and sensation of the outer world, but they have lost the feeling of reality that is ordinarily inseparable from these perceptions. And the same goes for the perception of oneself [. . .] They have kept all the psychological functions but they have lost the feeling that we always have [. . .] of being real, of being part of the reality of the world. (Janet 1903: 2:353–54)

Many philosophers, including Dilthey, James, and Bergson, used DPD in their inquiries concerning SE at the turn of the nineteenth century.

In what follows, I will describe DPD in more detail; I will demonstrate that studying it can provide arguments that settle many debates concerning the sense of existence. These arguments will have the same structure: (i) a given theory T of SE predicts that P (where P concerns what we should or should not observe); (ii) the study of DPD suggests that P is falsified (res. verified); (iii) DPD therefore disconfirms (res. confirms) T. Such arguments are always somewhat weak: they are doubly abductive. When I say that a theory of SE predicts (res. does not predict) that P, I just mean that P is best explained by that theory being true (res. false). Observation of DPD likewise suggests that P is falsified (res. verified) when P best explains (res. does not best explain) what we know of DPD. Although weak, these kinds of abductive arguments are pervasive in the natural sciences; they arguably constitute the best kind of empirical evidence we can adduce for the study of SE.

4. Characterizing DPD

DPD is characterized by a broad modification of how things appear to the subject. This modification crucially involves the impression that they have become unreal. Here are two classical reports:

It seemed to me that I did not exist anymore at all, that I could see, but that it wasn’t me who was seeing, that I could hear, but that it wasn’t me who was hearing; I wasn’t sure of anything. It seemed to be that both objects and I were nothing but a dream anymore. This state annoyed me tremendously [. . .]. (Janet 1903: 2:56–57)

I disappeared. Remained of me only an empty body [. . .] I think I can sum up: the self has totally disappeared; it seems to me that I died two years ago and that the things that subsisted have no connection whatsoever with myself. The way things appear to me does not tell me what they are, nor that they are real. Hence the doubt. (A patient of Ball, quoted in Hesnard 1909: 115)

Unlike hallucinations, which seem to involve a “hypertrophy” (false positives) of the sense of reality, DPD seems to involve an “atrophy” (false negatives).24 DPD is complex, but clinical history and practice suggest that we can distinguish at least two aspects of its phenomenology.

4.1. Depersonalization in the Narrow Sense (DP)

The first and most salient modification of experience in DPD bears on how the subject (or some of its parts) appears to itself. To distinguish this aspect of DPD from depersonalization disorder more broadly, we can call it depersonalization in the narrow sense, depersonalization symptoms, or trait depersonalization (DP). It involves the impression that one’s body is alien or unreal, that one’s mental states are alien or unreal, and that one is dead or even non-existent.

4.2. Derealization (DR)

Patients suffering from DP frequently complain that parts of the outside world or the outside world as a whole seem unreal and non-existent, or else that they are alienated from it. This is often called “derealization” (DR) (see Mayer-Gross 1935/2011 and Jaspers 1913/1962).

Of all this, it was the sensation of living in a dream that was the most painful. A hundred times I touched the objects surrounding me, I spoke out loud, to remind me the reality of the external world, the identity of my own self; but then my illusions were even more acute, the sound of my voice was unbearable and touching objects did not correct my impressions in any way. (Krishaber 1873: 9)

I lose the notions of the things surrounding me. To come back to reality, I sometimes prick myself hard with a pin; it calms me down momentarily. (Hesnard 1909: 83)

The first clinicians and philosophers to study depersonalization were extremely interested in patients’ phenomenology; they gathered extensive patient reports as well as detailed phenomenological analyses. Although the patients insist that their experience is extremely hard to articulate, they try very hard to describe it precisely. The unreal things are usually characterized as seeming (i) far or separated from them, (ii) in another world, (iii) dreamlike or hallucinatory, (iv) insubstantial, (v) lifeless and incapable of triggering emotions, and (vi) strange or image-like, bidimensional (I follow Hesnard’s [1909] excellent synthesis on impressions of unreality). Here are some quotes to illustrate these different descriptions.

Far or separated from the patients

Sometimes, mostly when I was leaving work or another absorbing occupation, something like a void appeared around me; it seems to me that this is what happens to those creatures we put under the bell jar of a pneumatic aspiration machine; everything had a new aspect, it seemed to me that everything was going far away. (Hesnard 1909)

I recognize the objects, their shape, their color and their light, but they seem somewhere else, not around me. I can see you well, but you seem far as if I was dreaming. (Hesnard 1909: 140–41)

I do not perceive the outside world well. It seems to me that I have never had direct and immediate contact with it. (Hesnard 1909)

In another world

The psychiatrist Bernard Leroy refers to “cosmic isolation,” noting that the world seems alien to DPD patients rather than simply far away (Leroy 1901).

While walking everything appeared crepuscular again [. . .] It was as if the universe had been hidden from my sight [. . .] It was like a dream as if I was outside of the world. (patient T., quoted in Hesnard 1909)

Often it seems to me that I am not from this world. My voice seems to be strange to me, and about my hospital mates, I tell myself: these are the figures of a dream. Often, I do not know whether I am awake or dreaming. (patient O., Krishaber 1873)

It is a radical isolation, you become a living atom separated from the other entities with the distance that separates stars. (Janet 1928: 46)

There is a real world that must exist somewhere as I have seen it before, where is it now? I see everything, of course, nothing seems to have changed, but things do not exist for me anymore. (patient Lætitia, quoted in Janet 1928: 47)

Dream-like or hallucinatory

I can feel numb of feelings, almost empty inside. I hate the fact I can’t feel things as I used to. It’s hard with day-to-day life when a lot of the time I struggle to know what is a dream and what real life is and has actually happened. (Sierra 2009: 27)

I used to live in a dream, in the spaces [sic] and not in the real world. (Nadia, quoted in Janet 1928: 47)

Insubstantial

[After a DPD crisis] I was finally reminded that that there is a real substrate [my emphasis] to what seemed just like a dream of life. (Dugas 1898: 129)

The world and everything in it, including his personal identity, felt unreal, unfounded, and without substance. (Simeon & Abugel 2006: 129)

Lifeless, incapable of triggering emotions

Kissing my husband is like kissing a table, sir. The same thing [. . .] Not the least thrill. Nothing on earth can thrill me. Neither my husband nor my child [. . .] My heart doesn’t beat. I cannot feel anything. (Dugas & Moutier 1911: 109)

I’m sometimes under the impression that everything is mournful, that life does not touch me, that nothing has an appeal to me, I let myself go, the landscape, the objects do not trigger the joy, the taste they used to have, but this sensation is different from the stupefaction that stroke me more often: in the latter case, there is nothing sad or joyous, there is just a discomfort in my heart and my breathing. (Hesnard 1909: 54)

Image-like, bidimensional

M. sees objects as flat, without relief, like a “cut-out image.” (Dugas 1898)

Since I am sick objects seem to be flat to me, without relief, dirty, strange. (Janet 1903: 1:247)

At times it is like looking at a picture. It has no real depth. (Sierra 2009: 51)

These reports are extremely valuable, but should nevertheless be taken with a grain of salt. The problem is not that patients are irrational and systematically unreliable. They seem perfectly rational, their “reality testing” is intact (they know that their impressions are misleading), and there is no reason to suspect that they are any more systematically misled about their experiences than someone without DPD. Nor is the problem that they can use deceptive metaphors, although that might be true. The issue is that it is difficult to establish when the purpose of their reports is to convey:

-

(i)

the fact that things seem unreal,

-

(ii)

some consequences of the fact that things seem unreal,

-

(iii)

the way things seem unreal when they do: that is, the phenomenology of unreality,

-

(iv)

the meaning of “unreality” they have in mind when they say things seem unreal to them.

Reflection can sometimes help to eliminate options. Given that the things we “see” in dreams typically seem real to us when we are dreaming, comparisons with dreams arguably fall into categories (i) or (iv). As we should not expect things that seem unreal to trigger normal emotions in us or to be directly presented to us, a lack of emotionality or picture-like character might be consequences of the lack of SE; these reports thus fall, arguably, into the category (ii). However, a large interpretative margin for error will often remain unless we invoke more objective data. We shall see that such data can also be useful in sorting out what is purely metaphorical and what is not.

5. DPD Supports Realism, Empiricism, Inflationism, and Internalism

5.1. DPD Undermines Eliminativism

Patients suffering from DPD feel as if some things are unreal or inexistent. They typically complain that they have lost something that they used to have, and we have no reason to discount the reliability of their testimony. Their misapprehension of reality has thus been construed as an atrophy of SE rather than as the hypertrophy of a sense of non-existence ever since Dugas’s and Janet’s seminal descriptions of the disorder. This should be seen as a confirmation of the claim that we do ordinarily possess SE. In other terms, eliminativism predicts that we should never lack SE, and this prediction appears to be falsified by DPD, which thwarts eliminativism.

5.2. DPD Undermines Deflationism

Consider deflationism, now. As we have seen, it relies on the thesis that existence awareness is necessarily universal: one cannot be aware of something without being aware of it as existing. The mere fact that depersonalized patients lack SE for many things of which they are aware disconfirms deflationism. Some things can appear to someone without appearing to exist, apparent being does not entail apparent existence. As depersonalization is considered to be a mental disorder, the deflationist can retreat to a more modest claim:

Quasi-deflationism: In normal cases, when one is aware of something one is aware of it as existing. SE, therefore, does not add anything to ordinary object awareness.

There is still room to adjust this weakened claim: experiences which are similar to DPD impressions, but short-lived and less intense, are arguably common and non-pathological (Sierra 2009). However, we should grant that something in the vicinity of quasi-deflationism might be safe from the depersonalization objection. Decisively, however, quasi-deflationism does not allow one to claim that SE reduces to the awareness of particulars.

5.3. DPD Supports Empiricism and Undermines Rationalism and Doxasticism

DPD is considered to involve—at least in part—a lack of SE. Whereas empiricist theories of SE predict that depersonalized patients should have abnormal experiences that explain this lack, rationalist theories predict that the patients’ rationality should also be abnormal. Doxastic theories of SE predict that the patients should have abnormal beliefs concerning what exists.

However, there is a clinical consensus that depersonalization is an essentially experiential phenomenon: things seem alienated and unreal to patients because their experience lacks something they used to have, not because they have abnormal beliefs or are irrational. This consensus is grounded on the facts that patients’ complaints typically evoke an experiential deficit (they describe a lack of certain feelings), that they have normal beliefs,25 that they are normally functioning, and that no cognitive tests have discovered a rationality problem (Simeon & Abugel 2006: 99).26 Accordingly, there is good evidence that DPD stems from experiential problems but not from rational or doxastic problems. One could object that rationality is a complex matter and that the kind of rational capacities needed for SE might not be those targeted by cognitive tests. It is traditional to distinguish between procedural rationality, epistemic rationality, and practical rationality (Bermudez 2001). While procedural rationality is concerned with reasoning according to the laws of deductive logic (and probability theory), epistemic rationality and practical rationality are concerned respectively with maintaining an optimal relationship between beliefs and evidence and between beliefs and actions. Our objector could argue that SE requires a demanding form of epistemic rationality (maybe connected with certain synthetic a priori judgments). In response, it must be emphasized that psychological tests can target certain aspects of epistemic rationality (e.g., the absence of cognitive biases) and that in any case there is yet no evidence of a single epistemic deficit explaining DPD. On the contrary, the latter seems to be completely explained by a merely experiential deficit. In the present state of research, we can thus safely conclude that depersonalization confirms empiricism about SE, but not rationalism or doxasticism.

5.4. DPD Supports Internalism and Undermines Externalism

Extreme externalists claim that SE concerning inner, subjective things is non-existent or greatly attenuated. They predict that a diminution in SE should not affect inner things (or not affect them to any great extent). This prediction is not verified for depersonalized patients. These patients complain of a sense of unreality and alienation regarding their own selves (Billon 2017), and even of their thoughts, feelings, and experiences of pleasure and pain. This is precisely what depersonalization in the narrow sense (DP) refers to. To be clear, it is not just that the patients are under the impression that their feelings and experiences are somehow abnormal because they seem to bear on unreal things: their real feelings and experiences seem attenuated or absent, replaced by a simulacrum that does not genuinely move them and that seems unreal too.27 After her hand had been pinched by Janet, a patient of his explained:

It was painful and my arm felt like withdrawing, but it was not a genuine pain, it was a pain that did not reach the soul [. . .] It is a pain, if you want, but the surface of my skin is miles away from my brain, and I do not know whether I am suffering. (Janet 1928: 65)

Another patient says:

Each of my senses, each part of my proper self is as if it were separated from me and can no longer afford me any sensation. (Sierra 2009: 8, emphasis mine).

Internalists claim that SE regarding inner things grounds SE regarding outer things; externalists claim a converse order of priority. Internalists predict that a lack of SE regarding external things should never occur without a lack of SE regarding inner things, whereas externalists predict that a lack of SE regarding inner things should never occur without a lack of SE regarding external things. We have seen that DP involves a lack of SE for inner things whereas DR involves a lack of SE for outer things. The precise relationship between the two is not totally clear (Sierra 2009: 35–37, 38–39). Many believe that the distinction between DP and DR is not clinically significant; some have even argued that DP and DR are simply two ways for patients to describe the same phenomenon (Varga 2012). Others claim that DP explains DR, their idea being that an experience that seems alienated from his subject or unreal cannot present what it refers to as being real (Dugas & Moutier 1911: 27). Whatever the relationship, patients’ reports and large-scale studies suggest that DP and DR usually occur together, that pure cases of DP are rare, and that pure cases of DR cases are so rare that their existence is controversial.28 These facts provide some limited support for internalism.

6. DPD Undermines Resistance Theories, Phenomenological Depth Theories, and Perceptual Presence Theories

Depersonalized patients are not delusional. They display no rationality deficit. We have no reason to believe that they are worse than anyone else at describing their diminished SE. On the contrary, they seem to be aware of every feature of the objects they perceive apart from their reality; they accordingly have perfect “contrast cases” to set apart object awareness with and without SE—contrast cases that we do not obviously have. Such contrast cases might provide them with clarity on SE’s precise phenomenology. The neuropsychology of DPD might likewise help us discover the neuropsychological underpinnings of SE. It is therefore unsurprising that DPD has been used to assess various inflationist theories of SE when it was discovered. Here, I will try to evaluate (what I take to be) the most influential of these theories in light of our current knowledge of DPD.

6.1. Resistance Theories

Let us first consider resistance theories. Dilthey (1890) believes that his resistance theory is confirmed by DPD:29

These observations establish with full certainty the role played by perceptual disorders in the weakening of reality attributed to outside objects, and indirectly, in the weakening of self-consciousness. (Dilthey 1890: 128, my translation)

The only evidence Dilthey cites is that DPD patients report sensory and motor complaints. He knew depersonalization only through Krishaber’s work (1873); Krishaber was arguably the first to study this pathology, and his patients did indeed complain of sensorimotor distortions. However, Krishaber was an ENT specialist. Many of his patients had vestibular problems (inducing vertigo or diplopia), and his sample was probably not representative. This explains why such perceptual complaints are far more frequent in his sample than they usually are.

DPD patients do sometimes report not feeling or seeing anything, or feeling as if they are acting passively or mechanically. However, it has been established clinically (Hesnard 1909; Dugas & Moutier 1911) and experimentally (Cappon & Banks 1965) that such complaints are not accompanied by any objective sensory or motor impairment.

As witnessed by some of the reports we have quoted, DPD patients often try to touch outside objects to verify their reality (with very limited success). This aspect of DPD might initially suggest an altered sense of resistance. However, these actions actually seem intended to verify that the testimony of one sense (such as vision) can be confirmed by other means. They do not seem directed at checking the sense of resistance. Indeed, patients do not just use touch to confirm their own reality; they also try to look at their face in mirrors, talk out loud, hurt themselves, or reflect very hard on what is happening to them (Hesnard 1909: 118).30

Conversely, some psychiatric conditions involve a loss of patients’ sense of resistance and effort, but they are not known to be accompanied by a loss of SE. Post-stroke fatigue is a case in point (Gandevia 1982).31 There is likewise evidence that schizophrenics’ delusions of alien control (whereby a patient claims that some of their actions are not their own) involve an abnormal sense of effort (Lafargue & Franck 2009; Gerrans 2014). As far as I can tell, this abnormality is not generally accompanied by a distortion of the sense of reality for the things on which these patients act.

Taken together, these observations undermine the resistance theory. Resistance theory predicts that DPD patients should have sensorimotor problems, which is not the case. It also predicts that patients with sensorimotor problems that affect their sense of effort should have an abnormal sense of reality; this is also not the case.

6.2. Phenomenological Depth and Perceptual Presence

What about phenomenological depth and perceptual presence theories of SE? Some verbal reports might suggest that these views are on the right track. As we have seen, patients sometimes say that they feel as if objects are abnormally far or separated from them. Like the resistance theory of SE, however, the phenomenological depth and perceptual presence theories predict sensorimotor problems. The phenomenological depth theory predicts problems with three-dimensional vision or at least with the apprehension of three-dimensional objects.32 The perceptual presence theory arguably predicts sensorimotor problems that affect evaluations of distance and potential bodily interactions. Again, no such problems have been observed.

In their standard forms, the phenomenological depth view and the perceptual presence view are moreover extreme externalist views. On these views, one cannot make sense of SE regarding inner items such as experiences or sensations. They are also disconfirmed by the aforementioned fact that DPD patients typically complain of the unreality of inner items as much as they do the unreality of outer things.33

7. DPD and Other Views of SE

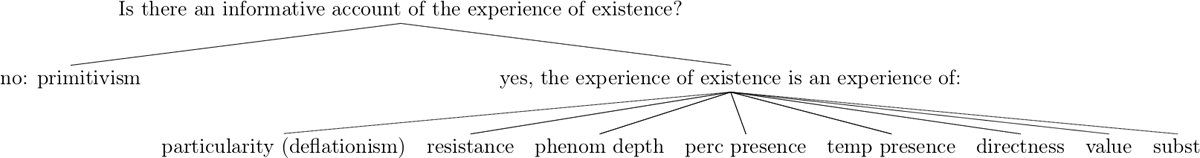

How should we understand the sense of reality? I have only presented what I take to be the most common answers to this question. The psychological and philosophical literature however contains many more theories regarding SE; it would be impossible to consider them all. To winnow down the plausible options, it might be useful to consider first alternative theories that have been put forward to account for derealization in DPD (see figure 2).

7.1. Existence and the Present Time

Bergson (1896/1912) argues that SE is the sense of the “now” or “temporally present.” His conceptual justification for this claim is the presentist idea that only the present is genuinely real. He also proposes that this sense is implemented by sensorimotor abilities that track our possible bodily interactions with the objects of perception; after all, one can only interact with what is temporally present, as opposed to the past or the future (Bergson 1896/1912: 68). After referring to Benjamin Ball’s patients (who suffer from DR), he explains:

If our analyses are correct, the concrete feeling that we have of present reality consists, in fact, of our consciousness of the actual movements whereby our organism is naturally responding to stimulation; so that where the connecting links between sensations and movements are slackened or tangled, the sense of the real grows weaker, or disappears. (Bergson 1896/1912: 174–75)

I believe that the neuropsychological aspects of Bergson’s theory have been disconfirmed by the observation that DPD patients have normal sensorimotor abilities. However, we could imagine a theory claiming that SE is the sense of the temporally present, but that the latter does not reduce to sensorimotor processing. The claim that SE is distorted in DPD because of a lack of sense of the temporal present was advocated by the psychiatrist Aubrey Lewis (1932) on the ground that patients’ perception of time is often altered. To some patients, time does seem to lose some of its putatively essential properties: the distinction between the recent and the distant past, the distinction between past, present, and future, or the fact that time passes at all. However, the temporal presence view predicts that DR and DP are always accompanied by DT; this does not seem to be the case (Sierra 2009: 35–37). Moreover, some patients complain that their memories lack a sense of reality; this suggests that, pace Lewis and Bergson, we do normally have a sense of reality for the past through episodic memory (“These memories are so vague, I wonder whether that happened to me or someone else, in a dream or in reality,” says one of Hesnard’s patients [1909: 90]; see also Janet and Raymond’s patient Toul. [1898: 159]).34

7.2. Existence and Directness

Drawing on DPD reports that describe unreal things as separated from the patients or image-like, Miyazono (2022) has argued that DR can be understood as involving a lack of “presentational phenomenology” or “object directedness” (see also Riccardi 2019). This claim could suggest that SE consists of aspects of experience in virtue of which we normally seem directly related to or acquainted with things perceptually presented, where acquaintance is understood broadly enough to include ordinary perceptual relations (along the lines, for example, of Recanati 2012).

This theory (which Miyazono does not put forward) can be seen as a generalization of the theory of perceptual presence in which spatial relations are replaced with broader acquaintance relations. It has the advantage of not being radically externalist like the perceptual presence theory: when I have a given experience, it seems to be directly related to me even though it need not seem spatially related to me. The theory is likewise compatible with the fact that DR always seems to occur alongside DP, which is problematic for externalist theories.

One problem with this theory is that the lack of a sense of directness in DPD could be incidental; it might be a consequence of the lack of SE rather than a cause. Phenomenologically, direct thoughts about particulars seem to be object-involving; they thus seem to presuppose the existence of their object. If that is correct, then every theory of SE should grant that we have SE concerning things that seem to be directly experientially presented to us. Conversely, however, it is not clear that things indirectly presented to me will ipso facto seem unreal. Take for example a professional radiologist who spots a cancerous tumor on an X-ray of his own lungs: the tumor will probably seem very real to him, but it may not seem to be directly presented to him. A deeper (and related) problem for the directness theory is its failure to answer the connection question: why would directness be required for existence?—or even just for apparent existence? The only published answer to this question I am aware of can be found in Turgot’s encyclopedia entry on “Existence” (Diderot & d’Alembert 1778). Turgot argues in a radically internalist manner that the self is the most supremely and obviously real thing; everything that seems related to it must also seem real through a kind of trickle-down effect:

Although objects are perceived outside us, as their perception is always accompanied by that of the self, this simultaneous perception establishes between them a relation of presence that gives to the terms of the relation, the self and the outside object, all the reality that consciousness grants to the feeling of oneself. (Diderot & d’Alembert 1778, my translation)

I am not sure that such a Cartesian answer will convince many philosophers today, nor that it can be adapted to do so.

7.3. Existence, Affectivity, and Value

The most common neuropsychological accounts of DPD (classical and contemporary) appeal to abnormalities in affective processing.35 In line with the Jamesian view that emotions are perceptions of one’s body, affective abnormalities in DPD are sometimes claimed to be grounded on distorted interoception.36 These affectivity accounts of DPD naturally suggest that SE is affective in nature and possibly interoceptive.

One problem with the affectivity view is that the empirical results supporting an affective account of DPD are mixed at best. It has frequently been noted that although DPD patients typically complain of attenuated or absent feelings, they seem from the outside to have normal emotional responses. This is partly why Dugas quickly gave up his affectivity account of DPD (Dugas & Moutier 1911; see also Billon 2023a). Moreover, neurophysiological measures have only shown discrete (and not always consistent, see Michal et al. 2013) abnormalities in affective processing (see Sierra 2009: 32–33). Patients’ interoceptive abilities also seem normal (Michal et al. 2014). Of course, these results do not exclude the possibility of more subtle abnormalities (see recent results obtained by Schulz et al. 2016). I do believe that current data, coupled with patients’ emotional complaints and observed lack of motivation, constitute reasonable evidence of an affective disorder of some sort in DPD. However, there does not yet seem to be a satisfying account of the precise nature of DPD’s affectivity deficit.

A related problem is that affectivity deficits in DPD patients may be an effect rather than a cause or ground of their SE disorder. It is to be expected that if something seems unreal to someone, they will not experience normal affects regarding it. You should not experience the same fear when confronted by a dangerous dog that seems real to you and a dog that seems unreal to you.37 Accordingly, it seems that any theory of SE predicts some affective distortions in DPD. The observation of affective distortions in DPD does not therefore vindicate the affectivity theory against its rivals.

Finally, the affective theory of SE does not answer the connection question. It says nothing about why affectivity should track (or seem to track) reality, nor about the concept of reality involved. Many patients do indeed claim that things seem lifeless and incapable of triggering proper emotions. But why should this lifelessness and emotional blunting be a mark of unreality? Or why should we tend to believe that it is?

A promising answer, recently suggested by Richard Dub (2021), relies on the common idea that affects in general, and emotions in particular, track values.38 They have an evaluative theme, and they present things as instantiating this evaluative theme. The evaluative theme is often called their “formal object” by philosophers (Teroni 2007); the psychologist Lazarus (1991) refers to the “core relational theme.” Fear tracks danger; anger tracks offensive behavior; sadness tracks loss. Perhaps existence is a value, just like danger or loss—or that may be how we apprehend it. The thesis that existence is a value, or extremely closely connected to a value, has a long and respectable history. Scholastics used to consider goodness and existence as “transcendental properties”: properties that transcend categories and that everything necessarily possesses. This does not quite imply that existence is goodness, but something close enough, namely, that existence and goodness are necessarily co-extensive (Aertsen 2012). Anselm characterizes existence as a perfection. Some have argued that these views can be severed from their traditional theistic grounds (Leslie 1979). Finally, Nozick (1974) has proposed the famous “experience machine” thought experiment which suggests that external reality has at least a certain prudential value. The experience machine is a virtual reality device that could give us all the pleasurable or desirable experiences we want for the rest of our lives. Nozick argues convincingly that we would refuse to get hooked to the machine because (roughly) happiness is not just a matter of sweet experiences: it requires that our experiences be experiences of the real world.

An initial problem with identifying existence (or merely apparent existence) with a value is that although we might argue that something must be real to have a value, the converse claim is less convincing prima facie. Dub simply supposes that the latter claim is true. McDaniel (2017) provides an interesting argument that might support this claim: that which “is to be counted” (without equivocation) is real, and to be real is always to deserve attention. McDaniel’s argument might suggest not only that everything real necessarily has a certain value, but even that reality is a value whose “fitting attitude” is attention. This is probably what James has in mind when he writes, to support his own affective theory of SE, that

Whatever excites and stimulates our interest is real; whenever an object so appeals to us that we turn to it, accept it, fill our mind with it, or practically take account of it, so far it is real for us, and we believe it. (James 1890: XXI)

However, there is a final and very serious objection to the claim that SE is affective because existence (or mere apparent existence) is a value. It is that existence can be described as good or bad (or as deserving or undeserving of attention) depending on whether one likes it and that the feeling of existence can correctly be described as having a positive or negative valence. For instance, Rousseau describes the feeling of existence as a positive emotion that tracks a positive value. “The feeling of existence,” he writes, “unmixed with any other emotion is in itself a precious feeling of peace and contentment” (1992b). Others, such as Schopenhauer, Sartre, and many Buddhist philosophers, describe existence as essentially negative and the feeling of existence as a nauseous and/or inauthentic and misleading sentiment (see Schopenhauer 1969 and Sartre 1938; on Buddhism, see Siderits 2007). In fact, even though most DPD patients describe their condition as awful and are often depressed, a few psychiatric patients seem to enjoy their DPD impressions (see De Martis 1956 for a striking case). Many Buddhists likewise describe the DPD impressions they attain through meditation as insightful blessings.39 If existence or apparent existence were a value, however, the feeling of existence could not be correctly described as having, depending on the context, a positive and a negative valence.

7.4. Existence and Proto-Affectivity

I believe that these difficulties with the affectivity account of SE stem from the fact that reality is not a value. It is rather a ground of value—or perhaps a proto-value. To have a genuine value (positive or negative), the thing in question must arguably be real. However, “being real” does not have a specific value, and this is so even if we were to grant that nothing can be real without having a certain value. Consider the following analogy. According to some philosophers called “quidditists”, many properties have an intrinsic nature or “quiddity” which is distinct from the property itself, and might indeed be the quiddity of different properties in other possible worlds (on the various brands of quidditism, see Smith, 2016). The quiddity of (having) a given charge e, is for example grounded in a certain quiddity which might be called a proto-charge, but which might be the quiddity of another property (say of the negative charge -e) in another possible world. The fact that existence is a ground of value explains why all theories of the sense of reality, even those that deny that reality is a value, should predict affectivity problems in DPD. This fact is also the reason why Dugas rejected his first affective theory in 1911 (Dugas & Moutier, 1911).

We might say that SE is in some sense affective, but not because affectivity grounds the sense of reality. SE is affective because affectivity is instead grounded on the sense of reality.40 A better way to say this—setting my conclusion apart from genuine affectivity theories—is that SE is “arch-affective” or “proto-affective” rather than affective.

7.5. Existence as Primitive

If SE is only proto-affective, then we still have not found a proper theory of SE. Maybe we should give up and surrender to the idea that SE is the sense of something primitive. On this view, there is an experience of reality, but this experience is a primitive experience of a “primitive realness”:41

What the experience of reality is in itself can hardly be deduced nor can we compare it as a phenomenon to any other related phenomena. We have to regard it as a primary phenomenon that can be conveyed only indirectly. [. . .] [It] is something absolutely primary and constitutes sensory reality [. . .] We can talk about this primary event, name it and rename it, but cannot reduce it any further. (Jaspers 1962: 94)

According to this (inflationist) primitivist view, there is no way to analyze the aspect of experience that grounds SE; we can at best describe its neurophysiological substrate. The connection question is answered by claiming it to be unanswerable: the experience of reality is a (conceptually) basic phenomenon.

I am sympathetic to this primitivist view. However, I believe that all forms of primitivism should be avoided by default; this is no exception. I would tentatively like to offer a possible alternative that, unlike the accounts we have reviewed so far, does not appear to be disconfirmed by our knowledge of DPD.

7.6. Existence as Substantiality

Let us take stock. As we have seen, DPD imposes some constraints on any proper theory of SE. First, a theory of SE should avoid extreme externalism; it should allow that inner things such as experiences or oneself normally seem real to us. Second, it should grant that SE is completely independent of our sensorimotor abilities. Unlike SE, our ordinary spatial judgments are grounded in our sensorimotor abilities. If we call “spatial content of experience” the aspects of experience that typically ground our spatial judgments, SE should then be independent of the spatial content of experience. Third, a theory of SE should grant that the sense of reality does not depend on our “affective abilities” and apprehension of values, although the latter two may well depend on the former.

Very few theories can meet all three constraints: I can see only one that does. Try to imagine a world exactly like our own in all respects, particularly all those respects that are relevant to the spatial content of our experiences, except for the fact that it is unreal. It might seem hard, at first because of the widespread Kantian intuition to the effect that there could not be something that does not exist (i.e., that being necessarily entails existence) and the connected appeal of deflationary views about SE. But try. Try to figure out a world that fits the experiences and descriptions of DPD patients. It would be a world in which you could play football, eat cheese with blueberries, or kill someone—but none of those activities would be real, and consequently, none of them would really count. However, we would have no way of distinguishing this imagined world from the real world through the spatial content of our perception and all the scientific knowledge that is (arguably) built on that content. The spatial and causal relationships between things would be the same as they are in our world. I think we all have a conception of what this imagined world would be like. It would be like a gigantic computer simulation. Indeed, many contemporary DPD patients convey the unreality of their world by invoking the simulation hypothesis rather than the dream hypothesis. One blog entry on the topic explains:

For most people, this [the simulation hypothesis] is a fun little theory that has little basis in reality. For persons with derealization, however, this is not simply a fun theory to think about, but instead, a question that we have to constantly tell ourselves not to pursue.

Another describes his experience as follows:

From my experience, it feels like I’m stuck in a virtual reality simulator—I know I’m me, I know my thoughts and actions are my own, but my surroundings don’t seem to be real. (I imagine it’s a bit like what Neo feels when he goes back into the Matrix after being freed.)42

In what sense would a worldwide simulation be unreal? It would be unreal in that although everything is structurally identical to the real world, its structure lacks the proper substrate—the deep intrinsic nature underlying it. This substrate might be absent. Alternatively, it would merely be silicon and code, and thus radically different from what we take it to be out there. Chalmers attacks precisely this concept of reality as “substantiality” when he claims that virtual reality is real (enough):

In what sense is normal reality real, and can virtual reality be real in that way? It’s a great philosophical question. [. . .] The view that virtual reality isn’t real stems from an outmoded view of reality. In the Garden of Eden, we thought that there was a primitively red apple embedded in a primitive space and everything is just as it seems to be. We’ve learned from modern science that the world isn’t really like that. A color is just a bunch of wavelengths arising from the physical reflectance properties of objects that produce a certain kind of experience in us. [. . .]

Physical reality is coming to look a lot like virtual reality right now. You could take the attitude, “So much the worse for physical reality. It’s not real.” But I think, no. It turns out we just take all that on board and say, “Fine, things are not the way we thought, but they’re still real.” That should be the right attitude toward virtual reality as well. Code and silicon circuitry form just another underlying substrate for reality. Is it so much worse to be in a computer-generated reality than what contemporary physics tells us? Quantum wave functions with indeterminate values? That seems as ethereal and unsubstantial as virtual reality. But hey! We’re used to it. (Chalmers 2019; cf. also Chalmers 2017)

One of Dugas’s seminal patients seems to have this concept of reality in mind: he claims that “I was finally reminded [after a DPD crisis] that there is a real substrate to what seemed just like a dream of life” (Dugas 1898: 129). Just as we are implicitly and more or less determinately aware that the things we see have hidden faces or parts, I want to suggest that we are implicitly and more or less determinately aware that the things we perceive have a certain substrate that gives them substantiality and that this substrate endows the things with a sense of being real. I furthermore want to suggest that this implicit substantiality-awareness is distorted in DPD, is proto-affective, and deserves to be called “the sense of existence.”

The substantiality view of the sense of existence does not imply that Chalmers is wrong in claiming that the substantiality view of existence should be abandoned. It just means that this view of existence somehow informs our SE, but of course, the latter could be misleading—compare again with what an eliminativist or even a physicalist about colors would say about our sense of the color blue (cf. §2.6). In order to argue, against Chalmers, for the substantiality view of existence, one would have to show not only that SE is so to speak extensionally or “ontically” reliable in the sense that it can teach us what exists, but that it is so to speak intentionally or “ontologically” reliable, in the sense that it can also teach us what it is for something to exist. This could be done by appealing to a strong form of the principle, called “phenomenal conservatism” (Huemer 2022), to the effect that “things are the way they appear to be”, a strong form of this principle that phenomenological tradition wholeheartedly endorses, but that Chalmers (2006) denies.43

I am aware that the substantiality view of SE is extremely speculative at this stage. It is also rather schematic as I haven’t said anything about the way the appearance of substantiality can be modulated and I do not know how this could be done but by further studies of DPD, hallucinations, and maybe perception of immersive virtual environments. However, unlike primitivism, it is informative (remember that according to primitivism “we have to regard [the experience of reality] as a primary phenomenon that can be conveyed only indirectly. [. . .] [that we can] name [. . .] and rename [. . .], but cannot reduce [. . .] any further” [Jaspers 1962: 94].).44 According to the substantiality view, we can say something non-trivial about SE: we can say that what distinguishes particulars that seem to really exist from particulars that merely seem to have being is an apparent feature, substantiality, that is distinct from resistance, perceptual presence, directness, phenomenological depth or value [. . .] This view would need to be backed up by more evidence, but unlike the non-primitivist theories we have reviewed so far, it is not refuted by what we know of DPD.

8. Pluralism about the Sense of Existence?

I said at the beginning that there might be more than one fundamental sense of existence. I decided to set aside this possibility and focus instead on the relatively fundamental sense of existence that seems impaired in DPD. Before concluding, I want to say a few words about the pluralist hypothesis and to refute what is probably the most influential reason to endorse it.

While trying to understand the deficit experienced by DPD patients, we have considered various aspects or concepts of “reality”: volitional independence, causal efficiency, representational independence, spatial connection to oneself (spatial presence), temporal presence, primitive realness, being interesting or worthy of attention, and substantiality. No doubt there are others. Suppose that we indeed had a form of awareness associated with each concept of reality: a sense of resistance, a sense of phenomenological depth, a sense of perceptual presence, a sense of directness, etc. Should we say that they are all equally forms of existence awareness and that pluralism is therefore true? The study of DPD strongly suggests otherwise. It shows that we can be aware of something as resistant (and thus probably as volitionally independent and causally efficient), perceptually present (and thus as in the same space as me), phenomenologically deep (and thus as representationally independent), and temporally present—but nevertheless not as really existing. This indicates that we should set SE apart from the senses of perceptual presence, resistance, phenomenological depth, being worthy of attention, etc. The fact that there are many aspects/concepts of “reality” and different senses that track them does not give us reasons to endorse pluralism about SE. They may only give us reason to endorse pluralism regarding the sense of “reality,” where being “real” is not understood simply as “existing” but as something fuzzier and less demanding such as the disjunctive (and probably open) property of existing or being volitionally independent or representationally independent or causally efficient, or in the same spatial manifold as me, etc. I suspect that pluralism about SE owes a lot to the common confusion of SE with “the” sense of “reality” thus vaguely understood.

9. Conclusion