1. Introduction

The hit film Ghostbusters was remade in 2016, to the excitement of some and the chagrin of others. This new version shared much of its plot with the 1984 original, but with a glaring exception: its cast was woman-led. This fact sparked record-high levels of frustration and disappointment.1 Ghostbusters, many scorned, had been made a “chick flick.”

‘Chick flick’ is a derogatory expression.2 It is used to demean, or otherwise diminish the value of, the things it is applied to. Thus the husband dismisses his wife’s proposal in Date Night:

Date Night. A husband and wife are choosing which movie to see. The wife proposes they see “that new one with Julia Roberts.” The husband scoffs. “Why would I want to see that? That’s a chick flick.”

The husband believes that films he calls ‘chick flicks’ are not worth seeing. Why? Intuitively, it is because he believes that “chick flicks” have certain characteristic features which he considers disvaluable—viz., features which make them the sort of thing women like.

Probably, he feels the same way about romantic comedies. Though ‘romantic comedy’ is not derogatory in the same way that ‘chick flick’ is, competent speakers know that the two expressions are related. In particular, they know that the expressions are associated with many of the same stereotypes, and are applied to many of the same things.

Yet competent users of the expressions do not think that all and only chick flicks are romantic comedies.3 While many people called the new Ghostbusters a chick flick, presumably no one called it a romantic comedy. Indeed, though competent users believe that ‘chick flick’ and ‘romantic comedy’ apply typically to the same things, they accept that cases like (1) and (2) can, at least in principle, obtain:4

- (1)

- The new Ghostbusters is chick flick, but it isn’t a romantic comedy.

- (2)

- Silver Linings Playbook is a romantic comedy, but it isn’t a chick flick.5

My purpose in this paper is not (just) to theorize about the terms ‘chick flick’ and ‘romantic comedy’. Rather, ‘chick flick’ and ‘romantic comedy’ will be my way into investigating a much broader class of expressions, the most important of which are slurs.

Slurs,6 I will suggest, bear the same relationship to so-called “neutral counterpart” terms as ‘chick flick’ does to ‘romantic comedy’. In particular, we should at least start by assuming that, semantically, sentences like (3) and (4) are akin to (1) and (2):

- (3)

- He’s a Jew, but he’s not a kike.7

- (4)

- He’s a kike, but he isn’t a Jew.

My purpose in this paper is use this starting assumption to dismantle what we’ll see is a thoroughly orthodox idea about pairs (1)/(2) and (3)/(4) in the philosophical slurs literature. I will then propose that we replace this idea with what I’ll call an overlap thesis about pairs of expressions like ‘chick flick’/‘romantic comedy’ and ‘k*ke’/‘Jew’. The resulting framework has the advantages of being simple, unified, and, unlike its orthodox rivals, neatly accommodating of a much wider range of data than has previously been considered.

Most importantly, however, the overlap thesis captures something about slurs and the people who use them which has been woefully obscured by the existing literature: that everyday bigotry makes exceptions.

The vast majority of the philosophical slurs literature, I submit, has taken the wrong cases as central—viz., cases like (5):

- (5)

- [Shouted at a gay couple holding hands]

- You’re going to hell, faggots!

These are what Robin Jeshion (2013b), aptly, calls “weaponized” uses of slurs—they are attacks. They are (among other things, which I say more about later) characteristically second-personal, extremely socially aggressive, intensely direct uses of slurs. And it makes sense for philosophers to care about such uses—they have extraordinary potential for harm.

But explanations of offensiveness and harm are only one desideratum of a theory of slurs; it should also elucidate the beliefs and attitudes of the people who use them. Most ordinary slur users, though, are not virulently absolutist in their bigotry—and most ordinary slur use is not like (5). Theorists, in focusing on offensiveness, have mistakenly centered the very worst slurs, as used by the very worst bigots. Consequently, philosophical orthodoxy has failed to capture not only the speech, but the thought, of ordinary slur users. Such speakers are in the business—as in (3) and (4)—of asserting, arguing about, and admitting “exceptions to the rule”; this is not a peripheral feature of ordinary bigotry, but its core.

2. Setup

2.1. Fixing Ideas

There are certain expressions that everyone agrees are slurs. Beyond such paradigmatic examples, however, it is controversial how broadly or narrowly the term ’slur’ should be defined. Where should we draw the line, if anywhere, between slurs and other pejorative expressions?

Traditionally, theorists have assumed that the answer to this question is at least partially semantic. This, ultimately, is an assumption that I want to challenge. But some philosophers are inclined to restrict the technical meaning of ‘slur’ for reasons that have nothing to do with semantics. Geoff Nunberg (2018), likewise skeptical of a sharp semantic definition, highlights a few. For example, we might think that ‘slur’ should capture only those expressions used to derogate members of groups unwarrantedly, as on the basis of traits beyond their control.8 Alternatively, we might want to reserve ‘slur’ for only those expressions used to derogate members of protected classes, or groups which are systemically oppressed.9 There is no settled answer to these questions, and, for this paper at least, I want to remain maximally neutral about them.10 My interest, rather, is in one of the most “settled” assumptions about slurs—viz., that expressions like ‘k*ke’ and ‘ch*nk’, in virtue of being slurs, bear a unique, semantically-given relationship to non-slur expressions like ‘Jew(ish)’ and ‘Chinese’.

The assumption I have in mind, here, is so foundational in the philosophical literature, and lurks so far in the discursive background, that pinning it down precisely is actually a little tricky; I will take up that task in §9. For now, just to help fix ideas, we can start with a paradigmatic example of a view that is committed to this assumption: Timothy Williamson’s (2009) conventional implicature account of slurs and so-called “neutral counterparts”. (We will see how to generalize from Williamson’s view later.)

Williamson proposed that expressions like ‘Jew’ are, in a very literal sense, the “neutral” “counterparts” of derogatory expressions like ‘k*ke’: they have exactly the same truth-conditional content, just not the same conventional evaluative upshot. ‘K*ke’ and ‘Jew’ refer to exactly the same group of people, but differ in what (else) they imply or communicate about that group. Thus, following Dummett’s (1973) discussion of the pejorative ‘Boche’, Williamson writes:

[T]o assert ‘Lessing was a Boche’ would be to imply that Germans are cruel, and I do not want to imply that, because the implication is both false and abusive. Since the false implication that Germans are cruel does not falsify ‘Lessing was a Boche,’ it is not a logical consequence of ‘Lessing was a Boche.’ Rather, in Grice’s terminology, ‘Lessing was a Boche’ has the conventional implicature that Germans are cruel, in much the same way that ‘Helen is polite but honest’ has the conventional implicature that there is a contrast between Helen’s being polite and her being honest. Just as ‘Lessing was a Boche’ and ‘Lessing was a German’ differ in conventional implicatures while being truth-conditionally equivalent, so too ‘Helen is polite but honest’ and ‘Helen is polite and honest’ differ in conventional implicatures while being truth-conditionally equivalent. (2009: 149–50, emphasis in the original)

In other words, “neutral counterparts” are perfect semantic proxies for the (truth-conditional) meanings of slurs: it is enough to know, for example, which group ‘German’ picks out to know which group ‘Boche’ does (and vice versa), ‘Chinese’, ‘ch*nk’, and, crucially, so on and so forth for all other relevant pairs of expressions. If Williamson’s conventional implicature view is correct, it is a general semantic fact about sentences like (6) and (7) that they stand and fall together:

- (6)

- Isaiah is a Jew.

- (7)

- Isaiah is a kike.

Williamson takes it explicitly for granted that this is something “competent” speakers know, or “are in a position to know” (2009: 149). Many philosophers, most of whom (presumably) do not themselves use slurs, or associate closely with those who do, have followed his lead in accepting this “fact” as given. This has been a mistake—one that has led to serious distortions about what counts as “basic competence” with slurs, as well as what that competence requires.

We become much better positioned to see this, I suggest, once we broaden our focus to include expressions which we ourselves (or people whom we encounter in our day-to-day speech communities) do use. As I will show, many such expressions pattern systematically with the kinds of paradigmatic slurs philosophers have tended to focus on, and so (I submit) should be accommodated by any adequate semantic theory. Still, we might hesitate to call many of these additional expressions “slurs”; or indeed, for the sorts of definitional considerations already mentioned, even positively deny that they are ones. I wish to remain maximally neutral on this front. I will thus be setting aside the word ‘slur’ for the majority of what follows. I will talk instead of what I’ll call derogatory classifiers.

2.2. Derogatory Classifiers and Non-Pejorative Associates

As I intend the term, “derogatory classifier” (hereafter “DC”) covers a much wider range of (more or less) derogatory expressions than has typically been considered in philosophical work on slurs. In addition to all of the expressions which theorists have tended to focus on—paradigmatic slurs such as ‘k*ke’, ‘ch*nk’, ‘n*gger’, ‘f*ggot’—DCs also include many expressions which theorists have tended only to mention in passing, and many more which they have never considered at all. Here are some examples:

| ‘alchie’ | ‘d*ke’ | ‘junkie’ | ‘scab’ |

| ‘anti-vaxxer’ | ‘dad bod’ | ‘Karen’ | ‘shrink’ |

| ‘backwater’ | ‘dad joke’ | ‘libtard’ | ‘slut’ |

| ‘Bernie bro’ | ‘dive bar’ | ‘man cave’ | ‘soy boy’ |

| ‘Bible banger’ | ‘feminazi’ | ‘McChurch’ | ‘sp*c’ |

| ‘bimbo’ | ‘fleabag motel’ | ‘McMansion’ | ‘tankie’ |

| ‘boomer’ | ‘flyover state’ | ‘mom jeans’ | ‘tech bro’ |

| ‘bootlicker’ | ‘frat bro’ | ‘neckbeard’ | ‘tourist trap’ |

| ‘breeder’ | ‘gamer’ | ‘nerd’ | ‘towelhead’ |

| ‘breeder bar’ | ‘gangbanger’ | ‘parasite’ | ‘townie’ |

| ‘cape(shit) movie’ | ‘gas guzzler’ | ‘pig’ | ‘trailer trash’ |

| ‘chav’ | ‘geek’ | ‘pill mill’ | ‘tr*nny’ |

| cheesehead’ | ‘ginger (kid)’ | ‘pillhead’ | ‘truscum’ |

| ‘chick flick’ | ‘goy’ | ‘plebe’/‘pleb’ | ‘traphouse’ |

| ‘coastie’ | ‘gringo’ | ‘poof’ | ‘treehugger’ |

| ‘commie’ | ‘hillbilly’ | ‘poser’ | ‘Trumper’ |

| ‘cracker’ | ‘hobo’ | ‘rag’ | ‘tourist trap’ |

| ‘cripple’/‘crip’ | ‘hole in the wall’ | ‘rainbow corp’ | ‘wetback’ |

| ‘cuck’ | ‘horse girl’ | ‘redneck’ | ‘woke’ |

| ‘c*nt’ | ‘jarhead’ | ‘r*tard’ | ‘yankee’ |

| ‘curry muncher’ | ‘jock’ | ‘rug muncher’ | ‘yuppie’ |

I do not expect the reader to recognize every expression on this list, or to agree with me that every expression on it deserves to be called “derogatory.” Hopefully, though, enough of the expressions are sufficiently familiar for the reader to detect a pattern. It has been my experience that, when presented with a handful expressions on the foregoing list, ordinary, competent (American) English speakers can spontaneously, effortlessly supply others to add to it. This, I take it, is strong prima facie evidence that DCs form some kind of unified linguistic class, whose members include at least many of the above expressions. (If you don’t think an expression from my list belongs to this class, please just put it to the side and interpret everything I say as going for the rest of the expressions, as well as for other members of the class.)

Importantly, though, in assuming that DCs form some kind of unified class, we need not assume anything about what makes that class unified. In the first place, as I’ve already emphasized, I do not wish to assume anything general about DCs’ status as slurs. Obviously, expressions like ‘frat bro’, ‘boomer’, ‘McMansion’, and ‘dad joke’ are not systematically oppressive; and however offensive they may be to certain communities of speakers, they carry nothing of the hideous force of the n-word. Whether and when an expression should be called a slur are considerations as heavy as they are fraught; it is an advantage of DC-talk that it does not (or at least need not) carry the same weight.

Likewise, and perhaps more to the point given my purposes here, I do not wish to beg any questions about DCs’ semantic status. Broadly, DCs are nominalized, variably pejorative11 (American) English expressions for categories of persons or things. I assume that they include all (but not only) expressions typically taken to derogate “on the basis of such things as race, ethnicity, nationality, class, religion, ideology, gender, and sexual orientation” (Bach 2018: 60). But in saying that they are “pejorative” or “derogative”, I mean only that DCs have established pejorative or derogative uses in at least some speech communities.12 Whether those uses are explained by something general about DCs’ semantics, or by something general about their pragmatic sociopolitical contexts of utterance, is something I likewise wish to leave open.

So I haven’t told you what DCs are. But Williamson (to return to our paradigmatic example) doesn’t define his target expressions either. Williamson offers the claim that slurs like ‘Boche’ add to the descriptive content of “neutral” expressions like ‘German’ by carrying an additional conventional implicature. This is theory, not definition. And to the extent that it’s theory, it is supposed to be supported by the best available evidence about the use practices of competent speakers. Since most of us (again, presumably) do not use slurs, the best evidence we have as theorists about the use patterns of competent speakers comes from our observations of others. In Williamson’s case, it comes apparently from Dummett’s (1973) report of ‘Boche’-users. In contrast, I believe that all of our ability to extend the foregoing list of DCs shows that all of us have the relevant kind of competence with DCs. We may not exhibit that competence by using paradigmatic slurs, but we exhibit it by using other terms on the list (or others I haven’t mentioned). In this way, we can collect evidence about slurs—which, after all, are DCs, whatever else they are—in a more direct way than Williamson (and indeed nearly anyone in the philosophical literature) does.

Indeed, as ordinary competent speakers, we are liable to notice a trend among many of the DCs on my list. In particular, we are liable to notice that it’s not just the worst, most paradigmatic slurs among them which seem to have what philosophers have called “neutral counterparts”: most of the DCs on my list may be intuitively “paired up” with other, (typically) non-pejorative group or category expressions. Somewhat awkwardly, but again to avoid begging questions, I’ll call these (putatively) more “neutral” group or category expressions non-pejorative associates, or NPAs:

| Derogatory Classifier | Non-Pejorative Associate | Derogatory Classifier | Non-Pejorative Associate |

| ‘n*gger’ | ‘Black (person)’ ‘African American (person)’ |

‘scab’ | ‘strikebreaker’ ‘person who crosses picket lines’ |

| ‘k*ke’ | ’Jewish (person)’, ‘Jew’ | ‘gangbanger’ | ‘gang member’ |

| ‘ch*nk’ | ‘Chinese (person)’ | ‘pig’ | ‘police officer’ ‘cop’ |

| ‘oriental’ | Asian (person)’ | ‘jarhead’ | ‘(U.S.) marine’ |

| ‘curry muncher’ | ‘South Asian (person)’ | ‘shrink’ | ‘psychiatrist’ |

| ‘sp*c’ | ‘Hispanic (person)’ | ‘tech bro’ | ‘(male) coder’ |

| ‘wetback’ | ‘Mexican (immigrant)’ | ‘parasite’ | ‘landlord’ |

| ‘gringo’ | ‘English speaker’ | ‘hobo’ | ‘homeless (person)’ ‘unhoused (person)’ |

| ‘cracker’ | ‘white (person)’ | ‘junkie’ | ‘illicit drug (ab)user’ ‘(heroin, cocaine) drug addict’ |

| ‘goy’ | ‘non-Jewish (person)’ | ‘pillhead’ | ‘prescription drug (ab)user’ ‘opioid addict’ |

| ‘Bible banger’ | ‘(Evangelical) Christian’ | ‘alchie’ | ‘alcoholic’ |

| ‘towelhead’ | ‘Muslim (person)’ ‘Arab (person)’ |

‘stoner’ | ‘cannabis user’, ‘marijuana user’ ‘weed smoker’ |

| ‘tr*nny’ | ‘transgender’ (person) | ‘frat bro’ | ‘(male) fraternity member’ |

| ‘f*ggot’ | ‘gay (man)’ ‘homosexual (man)’ |

‘gamer’ | ‘person who plays video games’ |

| ‘poof’ | ‘gay (man)’ ‘homosexual (man)’ |

‘jock’ | ‘athlete’ ‘person who likes sports’ |

| ‘d*ke’ | ‘lesbian (woman)’ ‘homosexual (woman)’ |

‘horse girl’ | ‘girl who likes horses’ |

| ‘rug muncher’ | ‘lesbian (woman)’ ‘homosexual (woman)’ |

‘ginger (kid)’ | ‘redhead’, ‘person with red hair’ |

| ‘breeder’ | ‘straight (person)’ ‘heterosexual (person)’ |

‘fatso’ | ‘fat (person)’ |

| ‘c*nt’ | ’woman’ ‘female (person)’ |

‘trailer trash’ | ‘person who lives in a trailer’ |

| ‘r*tard’ | ‘cognitively disabled (person)’ | ‘townie’ | ‘[town] native’ |

| ‘cripple’/‘crip’ | ‘disabled (person)’ | ‘tourist trap’ | ‘tourist attraction’ |

| ‘spaz’ | ‘(disabled) person with a movement disorder’ | ‘flyover state’ | ‘U.S. state between coasts’ |

| ‘boomer’ | ‘Baby Boomer’ ‘person born 1946-1964’ |

‘McMansion’ | ‘(expensive) tract home’ |

| ‘commie’ | ‘communist’ | ‘pill mill’ | ‘pain clinic’ |

| ‘tankie’ | ‘(Stalinist) communist’ | ‘rainbow corp’ | ‘pro-LGBTQ company’ |

| ‘libtard’ | ‘(American) liberal’ | ‘breeder bar’ | ‘straight bar’ ‘bar for non-LGBTQ people’ |

| ‘woke’ (n.) | (American) ‘progressive’ | ‘rag’ | ‘newspaper’ |

| ‘feminazi’ | ‘feminist’ | ‘gas guzzler’ | ‘vehicle with low gas mileage’ |

| ‘Bernie bro’ | ‘male Bernie Sanders supporter’ | ‘man cave’ | ‘basement’, ‘den’ |

| ‘Trumper’ | ‘Donald Trump supporter’ | ‘mom jeans’ | ‘jeans a mom wears’ |

| ‘anti-vaxxer’ | ‘vaccine skeptic’ ‘person leery of vaccines’ |

‘dad joke’ | ‘joke told by a dad’ |

| ‘treehugger’ | ‘environmentalist’ | ‘dad bod’ | ‘body (type) of a dad’ |

| ‘capeshit movie’ | ‘superhero movie’ ‘comic book movie’ |

||

| ‘chick flick’ | ‘romantic comedy’ |

Call any such pair of intuitively-linked expressions a “DC/NPA pair”:

DC/NPA pair for any two group or category expressions x and y, if x and y are intuitively linked in meaning, but x is (typically) derogatory and y is (typically) not, then ‘x’/’y’ is a DC/NPA pair.

Like examples of DCs, examples of intuitive DC/NPA pairs are easy to generate. Indeed, I suspect that, having now detected a pattern, the reader will find it easy to come up with more. This again is strong prima facie evidence that DC/NPA pairs are a highly general linguistic phenomenon, admitting of a basically unifying linguistic explanation. That there is a basic “DC/NPA relationship” which they all share in common is thus my default hypothesis:

generality all intuitive DC/NPA pairs in English are unified by a general linguistic relationship.

If generality is true, then we should expect to find systematic behavior across DC/NPA pairs. That this is precisely what we do find is my central contention.

But if generality is true, then this strongly suggests that our semantic theory of paradigmatic slurs should extend to DCs generally. And notably, almost no existing theory of slurs can be generalized in this way. For example, if Williamson’s theory were to be generalized to all DCs, it would be the thesis that every DC has an NPA with which it shares its descriptive content, and from which it differs only in carrying an additional conventional implicature. Even already we should be skeptical of the this hypothesis, since it’s hard to come up with NPAs for some DCs (like ‘hillbilly’, ‘chav’, and ‘backwater’). But I’m not going to rest my case on that. Let’s suppose instead that Williamson’s theory were to be generalized only to intuitive DC/NPA pairs. Abstracting to accommodate generality, this amounts to:

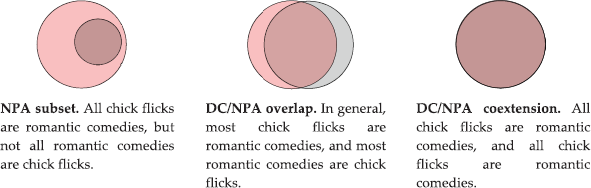

DC/NPA coextension for any DC and NPA intuitively linked in meaning, the linguistic relationship between them involves semantic coextension.

My argument against dc/npa coextension is very simple: it’s that not all chick flicks are romantic comedies, and not all romantic comedies are chick flicks. The rest of this paper consists entirely in generalizing and drawing morals.

The generalizing will proceed along two dimensions. The first, which I take up in §§3–8, is from the pair ‘chick flick’/‘romantic comedy’ to other DC/NPA pairs. I begin by presenting a range of linguistic data which philosophers of language have, regrettably, hereto overlooked. Having thus begun to motivate the idea that DC/NPA pairs, including paradigmatic slur/“neutral counterpart” pairs, appear, prima facie at least, to pattern with ‘chick flick’/‘romantic comedy’, I then propose an “overlap hypothesis” for ‘chick flick’/‘romantic comedy’ in §4. In §5, I argue that extending this same kind of overlap hypothesis to other DC/NPA pairs, more than being merely suggested by the data presented in §4, also explains the apparently systematic behavior of DC/NPA pairs in certain peculiar kinds of conversational exchanges. Moreover, as I argue in §§6–8, it explains that behavior in a simpler and more unified way than salient alternative hypotheses.

The second dimension of generalization, which I will take up in §9, is from dc/npa coextension and Williamson’s conventional implicature view to nearly every other theory in the existing philosophical slurs literature. A newcomer to that literature may be surprised to discover that the theories on offer there, despite their manifest number and apparent diversity, almost universally presuppose that the thesis of this paper, and more broadly generality, is false. This is not because generality its itself rejected as a salient hypothesis, but because a foreclosing assumption about slurs and so-called “neutral counterpart” terms is treated as near-axiomatic. This assumption, which will I call the “just-add-bad” assumption about so-called “neutral counterparts”, is especially clear in Williamson’s view; as we’ll see in §9, a much wider set of theories of slurs make a similar mistake. In §10, I offer a diagnosis for why that is.

3. Data

My first charge against standard theories of slurs is methodological. For reasons I will speculate about later, philosophers have consistently overlooked huge swaths of the relevant empirical data. They have (unsurprisingly!) focused on “paradigmatic” slurring expressions; but if generality is true, then we should expect the relevant pool of expressions to be much, much wider. In particular, we should expect to find patterns of use among not only competent users of paradigmatic slurs and their so-called “neutral counterparts”, but competent users of other DCs and NPAs as well. And the patterns we do find are striking indeed!

I will showcase two in particular. Both of these patterns involve explicitly contrastive uses of the relevant DCs and NPAs. In the first pattern, the relevant contrast is evaluative; users express differential attitudes of (comparable) approval or acceptance toward members of the relevant groups. In the second pattern, the relevant contrast is predicative; users express beliefs that one term applies but not the other.

3.1. Contrastive Evaluations and Prescriptions

Whatever the relationship is between DCs and NPAs, it is partially contrastive. This is to some extent true by stipulation, insofar as DCs are, to non-users at least, typically pejorative expressions, and NPAs (to non-users) typically are not. But beyond this perceived difference in (typical) pejorative force, it is also an empirical datum that DCs and NPAs are routinely contrastively evaluated by speakers who actually use them. The following kinds of evaluative judgments and prescriptions, for example, are made by competent users all the time:

- (8)

- From one Jew to another don’t be a Kike.13

- (9)

- It’s fine being black but don’t be a nigger everywhere you go.14

- (10)

- I’ll support the shit out of women all day long. We’re fabulous. However…it’s not OK to be a cunt just because you have one.15

- (11)

- It’s okay to be gay, it’s not okay to be a faggot tho.16

- (12)

- Be a lesbian & not a dyke, theres a huge difference…17

- (13)

- omg i so did NOT call u a wetback i said mexican there is a big difference! trust me.18

- (14)

- It’s okay to be liberal, but it’s not okay to be a libtard.19

- (15)

- I’m OK with people who support Bernie. I do not like Bernie Bros.20

- (16)

- You can be wary of Big Pharma and corrupt stuff going on [with vaccines] and unethical practices, but don’t be an antivaxxer.21

- (17)

- I’m not saying fuck the police. I’m saying fuck the pigs. There’s a difference between a police officer and a pig.22

- (18)

- Theres a difference between a Hobo, A junkie, and a Homeless person…Hobo=drunk, Junkie=thief, Homeless=deserve help.23

- (19)

- There’s a HUGE difference between living in a trailer and being trailer trash…24

- (20)

- I’m an environmentalist, but I hate treehuggers.25

- (21)

- I like redheads, but not gingers.26

- (22)

- Don’t mind people who smoke weed, HATE FUCKING STONERS!27

- (23)

- There is a massive difference between people that play games and “gamers.”28

- (24)

- Act like a fraternity brother, and not a frat bro.29

- (25)

- Be an athlete not a jock.30

- (26)

- Even if you are a mom, it’s not okay to wear mom jeans.31

- (27)

- Dads are hot but not dad bods.32

- (28)

- Craft rooms, hobby rooms, office rooms, and dens are fine. But I draw the line at man caves.33

- (29)

- There’s a fundamental difference between superhero films and capeshit. Joker is a superhero film, MCU is capeshit.34

- (30)

- I like romantic comedies. Not chick flicks. There’s a huge difference.35

This fact, along with the additional observation that among such examples there are several common patterns, is consistent with our working hypothesis about DC/NPA pairs. And supposing that that hypothesis is true, it places an empirical constraint on any adequate theory of the DC/NPA relationship: any such theory should plausibly explain not only why particular DCs and NPAs are intuitively linked for competent speakers, but also why competent users of those expressions often explicitly contrast them in evaluative judgments and commands.

3.2. Bidirectional Ascription Divergence

In §2, I emphasized how competent users of ‘chick flick’ and ‘romantic comedy’ are prepared to grant that some sentences like (1) and (2) are (or in principle could be) true:

The new Ghostbusters is chick flick, but it isn’t a romantic comedy.

Silver Linings Playbook is a romantic comedy, but it isn’t a chick flick.

In such cases, competent users take ‘chick flick’ and ‘romantic comedy’ to come apart in both directions. But this isn’t just true of ‘chick flick’/‘romantic comedy’; competent users of many, many other DCNPA pairs use them in a structurally analogous way.

Examples of such “bidirectional divergence” in DC/NPA ascriptions are exceedingly easy to come by in “real life” conversational contexts. My goal in this section is merely to showcase their apparent systematicity and range:

‘antivaxxer/‘person cautious of vaccines’

- (31)

- You don’t have to be against all vaccines to be an antivaxxer. if you’re cautious of a vaccine that’s proven safe and effective but not of the infectious disease which is more likely to kill and hospitalise, then you’re an antivaxxer.36

- (32)

- As someone with an autoimmune condition I’m leery of vaccines (I’m not an ‘antivaxxer’ just well aware my body can go haywire after getting a jab).37

‘Bernie bro’/‘male Bernie Sanders supporter’

- (33)

- Just because you’re a Bernie supporter doesn’t mean you’re a Bernie bro.38

- (34)

- You don’t have to be a man to be a Bernie Bro, you just have to act like a hooligan.39

‘boomer’/‘Baby Boomer’[‘(American) person born 1946–1964]

- (35)

- I differentiate it this way: Baby-boomer is the generation. Boomer (by itself) is an insult to connote a state of mind. You’re a baby-boomer, but not a boomer.40

- (36)

- Mayo Pete is a boomer at 37. Does this help everyone understand that boomer isn’t just an age thing?41

‘breeder’/‘straight (person)’

- (37)

- I will never understand breeders. No not two straight people having sex, I mean people who actively choose to reproduce. Literally why would you ever? You’re giving up your whole life away for a measly little spawn.42

- (38)

- Any queer who has biological children is still a breeder.43

‘capeshit (movie)’/‘superhero movie’

- (39)

- The Dark Knight is the rare instance of a superhero movie that isn’t capeshit.44

- (40)

- It’s a sad fact to come to terms with but Star Wars is “capeshit”.45

‘ch*nk’/‘Chinese (person)’ [note: first example also contains the N-word]

- (41)

- Not all Chinese people are chinks. Just like not all black people are niggers.46

- (42)

- I hate those stupid Vietnamese people. Stupid chinks always torturing animals.47

‘c*nt’/‘woman’

- (43)

- Not all women are cunts. Term is reserved for only the deserving.48

- (44)

- Men can be cunts too. Just as they can be pussies.49

‘dad joke’/‘joke told by a dad’

- (45)

- Being a dad with “actually funny jokes and not just dad jokes” might be the best feedback you can get from your kid.50

- (46)

- I don’t understand why Cory Booker tells so many Dad jokes when he’s not a Dad.51

‘dad bod’/‘body [type] had by a dad’

- (47)

- You don’t have to be a dad to have a dad bod.52

- (48)

- Lesley and I saw probably the hottest dad ever without a dad bod…god bless.53

‘d*ke’/‘lesbian (person)’

- (49)

- I always wanted a lesbian friend, lesbian not a dyke.54

- (50)

- Not all dykes are lesbians. I got a cousin who’s a dyke but she has a husband.55

‘f*ggot’/‘gay (person)’

- (51)

- Just remember honey, there are good gays, and bad gays. There are gays and then there are faggots.”56

- (52)

- Whoever decided to allow transgender faggots in the military is a retard.57

‘fatso’/‘fat person’

- (53)

- You’re a fatso. You’re skinny but you eat a lot.58

- (54)

- “You’re fat but not so fat to be called a fatso” My little brother is so kind to me.59

‘gamer’/‘person who plays video games’

- (55)

- I deliberately avoid identifying as a gamer because of the toxic associations of gamer culture. I am a game player, for sure, but not a gamer.60

- (56)

- Typical gamer. Doesn’t even play the game, just wanks off at the pretty girls.61

‘ginger’/‘redhead’

- (57)

- You stan a ginger I don’t wanna hear it. And before you say Shanks is one too no he’s just a redhead but not a ginger.62

- (58)

- She’s a ginger, not the redhead ginger though. But still a ginger. And they say gingers have no soul.63

‘horse girl’/‘girl who has horses’

- (59)

- Alright she has horses but she’s not a ‘horse girl’.64

- (60)

- You don’t have to own or ride a horse to be a horse girl. It’s a certain je ne sais quoi you have.65

‘junkie’/‘(heroin) drug addict’

- (61)

- Getting addicted does in fact make you an addict! But it doesn’t make you a junkie by any means.66

- (62)

- If you snort cocaine from time to time you’re still a junkie I don’t care.67

‘k*ke’/‘Jew(ish)’

- (63)

- Maybe, but he isn’t a kike or have a socialist agenda like 99% of the Jews.68

- (64)

- The Church at Old Jewish Schildesche wanted me dead you kike Catholics.69

‘libtard’/‘liberal’

- (65)

- I wasn’t saying all liberals are libtards. They are not. But libtards do exist and they need to be called out on their bullshit.70

- (66)

- About someone wearing a communist shirt: Maybe not the exact definition of liberal but still a libtard.71

‘mom jeans’/‘jeans worn by a mom’

- (67)

- My mom always wearing jeans. Thank god she doesn’t wear mom jeans!72

- (68)

- Lucky Obama doesn’t have a son! How would you like to grow up with a dad who throws like a girl & wears mom jeans?73

‘pig’/‘police officer’[‘cop’]

- (69)

- Not everyone who consumes marijuana is a violent criminal/bum, just like not every police officer is a trigger happy pig.74

- (70)

- Judges, prosecutors, guards, and military [aren’t police officers but] are still pigs.75

‘rag’/‘newspaper’

- (71)

- The Guardian is a lefty liberal newspaper but not a rag. I still regard it one of British media’s best in news reporting and analysis.76

- (72)

- I’ve had enough of this rag magazine [Rolling Stone]. It used to be respectable but now it’s no better than a supermarket rag paper at the checkout.77

‘stoner’/‘person who smokes weed’

- (73)

- I want a roommate that smokes weed but isn’t a stoner.78

- (74)

- You can be a stoner without smoking weed.79

‘trailer trash’/‘person who lives in a trailer’

- (75)

- “Nomadland” showed us that just because you live in a trailer, you’re not necessarily trailer trash. Similarly, Marjorie Taylor Greene lives in a house.80

The structural pattern, here, is striking—as far as it goes. But while such a pattern is consistent with my proposal—viz., that intuitive DC/NPA exhibit the same basic linguistic relationship as ‘chick flick’/‘romantic comedy’—it certainly does not entail it. Much more needs to be said to motivate this idea, especially for DC/NPA pairs involving paradigmatic slurs. This will be my goal in the next two sections.

4. ‘Chick Flick’/‘Romantic Comedy’: The Case for Overlap

4.1. An Obvious First Thought

The ubiquity, range, and apparent systematicity of the examples just surveyed lends prima face support to the default hypothesis proposed in §2:

generality all intuitive DC/NPA pairs in English are unified by a general linguistic relationship.

More specifically, we seem to have evidence that DC/NPA pairs pattern with, and hence are basically assimilable to, ‘chick flick’/‘romantic comedy’. So whatever the relationship is between ‘chick flick’ and ‘romantic comedy’, we have prima facie reason to assume that an analogous relationship obtains for all other DC/NPA pairs.

What, then, is the nature of the relationship between ‘chick flick’ and ‘romantic comedy’?

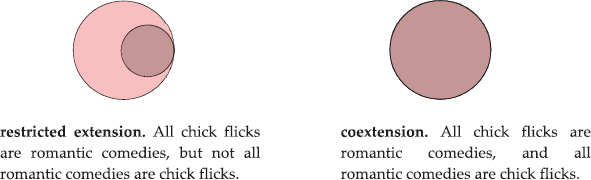

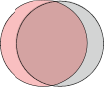

If we weren’t ourselves competent speakers, and were to take our cue from the philosophical slurs literature, we might suppose that, extensionally, there are two possibilities for ‘chick flick’ and ‘romantic comedy’: either ‘chick flick’ refers to a proper subset of the things which ‘romantic comedy’ refers to; or ‘chick flick’ and ‘romantic comedy’ pick out exactly the same extension:

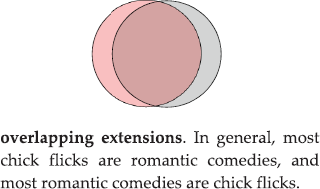

As competent speakers, though, we know that both of these hypotheses are obvious nonstarters. Indeed, the obvious first thought is that, extensionally, ‘chick flick’ and ‘romantic comedy’ generally—but not completely—overlap:

Moreover, the “obviousness” of this “obvious first thought” seems obviously not an accident. While competent users will grant that “chick flicks” and “romantic comedies” can, sometimes, fall in the margins of the Venn diagram, they expect them to fall in the middle. For competent speakers, ‘chick flick’ and ‘romantic comedy’ are prototypically directed: they are conceptually associated with most if not all of the same stereotypes, beliefs, and evaluative attitudes.

This, too, is a kind of “overlap”: call it stereotype overlap. Together, the notions of stereotype overlap and extensional overlap (hereafter “S-overlap” and “E-overlap”, respectively) give us an “obvious first answer” to our question:

overlap hypothesis the intuitive linguistic relationship between ‘chick flick’ and ‘romantic comedy’ substantial degrees of overlap in

semantic extension (E-overlap), and

the stereotypes, beliefs, and evaluative attitudes associated with each expression in the minds of competent speakers (S-overlap).

overlap hypothesis has immediate intuitive appeal. But we need not rely solely on intuition to think it’s on the right track. The ultimate test of plausibility for any of the candidate pictures of the target relationship (restricted extension, coextension, overlap, etc.) is that they have to make sense of both the phenomenon I have been emphasizing so far (explicitly contrastive uses) and cases where competent users seem, at least, to treat the target expressions as synonyms. It would be ideal, then, for us to find a test case in which speakers seem to do both of these things. And indeed, there are such cases—viz., exchanges like (76):

- (76)

- A: The new Ghostbusters is a chick flick.

- B: But it’s an action movie, not a romantic comedy!

- A: Whatever, it’s still a chick flick.

In the next section, I will argue that overlap hypothesis with some plausible assumptions about common ground, best explains this exceedingly familiar but, through the lens of the philosophical slurs literature, somewhat peculiar kind of exchange. Having made this case, I will then show that the same basic story, just as generality would have us predict, successfully generalizes to a range of other DC/NPA pairs.

4.2. A Default Presumption against Exceptional Cases

When competent users of ‘chick flick’ and ‘romantic comedy’ witness exchanges like (76), they effortlessly understand them. But what explains this, exactly? Why should B’s utterance in (76) be a relevant—let alone natural—reply to A’s? What do romantic comedies, which A never mentioned, have to do with anything?

Intuitively, the answer is that B, in responding the way he does, has taken something for granted about the relationship between chick flicks and romantic comedies. In particular, B seems to have presupposed that ‘chick flick’ applies to something only if ‘romantic comedy’ does. Thus, as he believes that Ghostbusters isn’t a romantic comedy, he tries to correct A’s application of ‘chick flick’ to the film.

On reflection, B would likely reject this presupposition about chick flicks and romantic comedies. If asked to provide counterexamples like (1) and (2), he probably could:

The new Ghostbusters is chick flick, but it isn’t a romantic comedy.

Silver Linings Playbook is a romantic comedy, but it isn’t a chick flick.

Still, he would probably have to think about it a little. For when B, like most competent users, ordinarily hears81 the words ‘chick flick’ and ‘romantic comedy’, movies like Ghostbusters and Silver Linings Playbook are probably not what first comes to mind. What likely does first come to mind are films like Pretty Woman, Love Actually, Bridesmaids, and He’s Just Not That Into You—viz., films that are both chick flicks and romantic comedies (as far as competent users are concerned). For competent users, the most prototypical examples of chick flicks are also prototypical examples of romantic comedies. Less prototypical examples are, well, atypical: if cases like (1) and (2) obtain, they do so only at the margins:

Indeed, competent users’ semantic commitment to substantial E-overlap between ‘chick flick’ and ‘romantic comedy’ is plausibly underwritten by the substantial S-overlap in their representational beliefs. And plausibly, this in turn has certain socio-pragmatic upshots.

In the first place, we should expect a semantic commitment to substantial E-overlap (underwritten by substantial S-overlap) to inform competent users’ default expectations about which sorts of things they will encounter in the world. But we should also, crucially, expect it to inform their default conversational expectations of one another. If competent users believe that the (vast) majority of “romantic comedies” they encounter in the world will be “chick flicks”, and that the (vast) majority of “chick flicks” they encounter will be “romantic comedies”, then it is plausible that they will believe of conversations with one another that possible exceptions will be “bracketed” by default. It is plausible, in other words, that in normal conversational contexts, competent users expect one another to proceed as if the E-overlap between ‘chick flick’ and ‘romantic comedy’ is complete:

Such a default presumption against exceptional cases, underwritten by a shared commitment to substantial E-overlap, can explain some important data about exchanges like (76):

- (76)

- A: The new Ghostbusters is a chick flick.

- B: But it’s an action movie, not a romantic comedy!

- A: Whatever, it’s still a chick flick.

First, it can explain why B replies the way he does. Second, it can explain why, despite B’s replying the way that he does, A’s rejoinder is felicitous, and why the exchange in general is so predictable and familiar.

Initially, at least, B is confused by A’s assertion. But this is exactly what we should expect, if B expects a presumption against exceptional cases to operative by default, and A to say so if it’s not. Indeed, A could have cancelled this presumption for B, had he wanted to or thought to. In particular, he could have said (1):

- (1)

- The new Ghostbusters is chick flick, but it isn’t a romantic comedy.

But A doesn’t say (1); he says (77):

- (77)

- The new Ghostbusters is a chick flick.

And this, together with the presumption that all and only chick flicks are romantic comedies, immediately entails (78)—which B rejects:

- (78)

- The new Ghostbusters is a romantic comedy.

Hence his attempted correction: “But it’s an action movie, not a romantic comedy!”

Of course, this is not the only possible explanation for B’s attempt to correct A. We might hypothesize, for example, that what B is attempting to correct in (76) is some obvious misusage which he takes A to have committed—one which would throw into question A’s basic competence with ‘chick flick’. But we have little reason to assume this. A need not have made a semantic error for his conversational move to be suboptimal; B’s complaint could just as easily be pragmatic. By choosing to say (77) when he could have said (1), and neglecting (ex hypothesi) to cancel the presumption that all and only chick flicks are romantic comedies, A has thus predictably and avoidably introduced confusion into their exchange.

Moreover, if A’s use of ‘chick flick’ in (76) was indeed an obvious semantic mistake—the kind that would make us question his basic competence—then it would be hard to explain why his rejoinder is (a) so immediately comprehensible, and (b) not conversation-stopping.

There is no intuitive sense that A, in rejoining the way he does, is being somehow uncooperative, or failing to give B uptake. On the contrary, A intuitively concedes B’s rejection of ‘romantic comedy’ as applied to the new Ghostbusters—this is the intuitive content of his ‘whatever’. Indeed, the casual dismissiveness of that same ‘whatever’ suggests that A is unsurprised by B’s confusion. This makes sense, if A is a competent user who normally shares a presumption against exceptional cases. That he thinks this is an exceptional case explains why, having thus conceded the rejection of the NPA, he proceeds to double down on the DC. And that such alleged marginal cases are, from the perspective of competent users, possible, explains why his doing so is felicitous. B may not agree with A that the new Ghostbusters is a “chick flick,” properly so-called; the two of them may go on to argue about it. But it would be strange, and indeed inappropriate, for B to simply throw up his hands at A’s rejoinder in (79) and conclude he’s speaking to an incompetent troll.82

Now, recall dc/npa coextension, which we abstracted from Williamson’s (2009) conventional implicature view of paradigmatic slurs and generalized for all DC/NPA pairs:

DC/NPA coextension for any DC and NPA intuitively linked in meaning, the linguistic relationship between them involves semantic coextension.

dc/npa coextension predicts that ‘chick flick’ and ‘romantic comedy’, if they indeed constitute an intuitive DC/NPA pair, are truth-conditionally equivalent.

I submit that this prediction is false on its face. But suppose that we thought it was at least prima facie plausible enough to test. An initial point in its favor is that it in turn predicts something importantly true about exchanges like (76)—viz., that competent users will conversationally presuppose that all and only chick flicks are romantic comedies. This is in fact what B seems to do!

- (76)

- A: The new Ghostbusters is a chick flick.

- B: But it’s an action movie, not a romantic comedy!

- A: Whatever, it’s still a chick flick.

But dc/npa coextension also predicts much more than this—indeed, much too much. For if dc/npa coextension were true, then we should also expect that the expressions ‘chick flick’ and ‘romantic comedy’ will, from the perspective of people who actually use them, be intersubstitutable in their normal, literal uses. We should expect, in other words, (76) and (79) to be equally comprehensible:

- (79)

- A: The new Ghostbusters is a romantic comedy.

- B: But it’s an action movie, not a romantic comedy!

- A: #Whatever, it’s still a romantic comedy.

(79), however, is not comprehensible at all! Whereas, before, A felicitously doubled-down in the face of B’s attempted correction, his rejoinder here is bizarrely uncooperative. And this actually should not be surprising, given what we’ve supposed already about A’s rejoinder in (76)—viz., that the intuitive conversational function of his qualificational ‘whatever’ is to signal concession of B’s point that the new Ghostbusters isn’t a romantic comedy. But this is just the negation of A’s original claim. A cannot felicitously concede that the new Ghostbusters isn’t a romantic comedy, while also stubbornly insisting that it is.

This pronounced asymmetry in comprehensibility and felicitousness between (76) and (79) is a datum about ‘chick flick’ and ‘romantic comedy’ which we might not have discovered, had we not thought to try fitting those expressions into Williamson’s mold. But it is a datum which any good theory of that pair should fit, all the same. And happily, overlap hypothesis can already do so, without any fancy theoretical footwork or added machinery:

overlap hypothesis the intuitive linguistic relationship between ‘chick flick’ and ‘romantic comedy’ involves substantial degrees of overlap in

semantic extension (E-overlap), and

the stereotypes, beliefs, and evaluative attitudes associated with each expression in the minds of competent speakers (S-overlap).

overlap hypothesis commits us to substantial E-overlap between ‘chick flick’ and ‘romantic comedy’; but, crucially, it does not commit us to complete E-overlap. Indeed, this was the point: to capture the intuitive idea (from the perspective of competent users) that movies can be chick flicks without being romantic comedies, and can be romantic comedies without being chick flicks (though we may debate about which ones). But no movie can, in any literal sense, be a romantic comedy without being a romantic comedy. That a speaker cannot “get away” with denying this latter claim, but may give voice to the preceding one with his reputation as competent speaker intact, is not, on the present theory, any surprise at all.

In sum, then, the “obvious first thought” to have about ‘chick flick’ and ‘romantic comedy’ is that their relationship involves substantial E- and S-overlap; and this overlap hypothesis, together with some very basic Stalnakerian assumptions about common ground, can successfully account for and predict several important data by which any adequate theory of that pair must be constrained:

that competent users of ‘chick flick’ and ‘romantic comedy’ take those expressions to be tightly intuitively related, both in extension and in the stereotypes and attitudes associated with them;

that, despite this fact, competent users sometimes apply ‘chick flick’ and ‘romantic comedy’ to different things;

that exchanges like (76) are, to competent users of ‘chick flick’ and ‘romantic comedy’, familiar and immediately comprehensible;

that B’s reply in (76) seems to presuppose that all and only chick flicks are romantic comedies (viz., that E-overlap between ‘chick flick’ and ‘romantic comedy’ is complete);

that despite this fact, A’s rejoinder in (76) is not only felicitous, but is consistent with, and indeed actually suggestive of, basic competence with the relevant expressions; and

that this marks a clear asymmetry with (79), where the exchange in general is defective, and A’s rejoinder in particular is bizarre and uncooperative.

Moreover, the present proposal explains why the foregoing would all be true, by explaining why, in normal conversational contexts, competent users would share a default presumption against exceptional cases.

This is strong evidence in favor of overlap hypothesis. It is also, if the data in §3 is any indication that generality is true, evidence for a generalize version for all DC/NPA pairs:

DC/NPA overlap for any DC and NPA intuitively linked in meaning, the linguistic relationship between them involves substantial degrees of overlap in

semantic extension (E-overlap), and

the stereotypes, beliefs, and evaluative attitudes associated with each expression in the minds of competent speakers (S-overlap)

As we’ll see, dc/npa overlap is not quite the thesis I will ultimately land on. But, like its ‘chick flick’/‘romantic comedy’ analogue, it is the “obvious first thought” to have, based on what we have seen so far; sticking with it for now will make it easier to fix ideas. It also, I think, is not very far from the truth.

5. Generalizing to Other DC/NPA Pairs

In the previous section, I began by suggesting that whatever theory we accept about the relationship between ‘chick flick’ and ‘romantic comedy’, we have good reason to entertain about DC/NPA pairs in general. In this section, I will provide some additional arguments for this claim. In particular, I will argue that (a) DC/NPA pairs pattern systematically with ‘chick flick’/‘romantic comedy’ in exchanges like (76); and (b) such patterns are plausibly explained by the same pragmatic mechanism which I proposed for (76), whereby competent users proceed conversationally by default as if E-overlap is complete.

That story, recall, involved a default conversational presumption against exceptional cases among competent users, underwritten by a shared expectation that most cases will be typical cases; viz., cases wherein ‘chick flick’ and ‘romantic comedy’ do not come apart. This explains why, in (76), B attempts to correct A’s use of ‘chick flick’ by rejecting the aptness of ‘romantic comedy’, but A nevertheless felicitously doubles down:

- (76)

- A: The new Ghostbusters is a chick flick.

- B: But it’s an action movie, not a romantic comedy!

- A: Whatever, it’s still a chick flick.

This marked a clear contrast with (79), where B instead attempts to correct A’s use of ‘romantic comedy’, and A infelicitously doubles down:

- (79)

- A: The new Ghostbusters is a romantic comedy.

- B: But it’s an action movie, not a romantic comedy!

- A: #Whatever, it’s still a romantic comedy.

Call exchanges like (76) DC-corrections and exchanges like (79) NPA-corrections.

In this section, I will show that the same asymmetry between DC- and NPA-corrections obtains for other DC/NPA pairs—including more orthodox pairs of paradigmatic slurs and “neutral counterpart” terms—and that in each case this asymmetry is plausibly explained by the same kind of overlap hypothesis proposed for ‘chick flick’/‘romantic comedy’ in §4. Moreover, I will argue that this is a better explanation than dc/npa coextension, our toy Williamsonian foil.

Philosophers who are drawn to the Williamsonian view are likely to think that slurs and their neutral counterparts are importantly disanalogous from DC/NPA pairs like ‘chick flick’/‘romantic comedy’. So part of my goal will be to argue that they are not so different after all. Proponents of the Williamsonian view might point to any of three purported disanalogies: (i) difference in presence of derogatory force or intent, (ii) difference in degree of hypothesized overlap, and (iii) difference in target kind. But as I will show, these are not general differences between slur/”neutral counterpart” pairs and other DC/NPA pairs. For each of (i), (ii), and (iii), there are some non-orthodox DC/NPA pairs which are not different from slur/“neutral counterpart” pairs in the relevant respect. Thus, we have every reason to pair that the basic DC/NPA relationship is perfectly general, making no special exception for more orthodox pars of slurs “neutral counterparts”. A semantic theory of slurs ought to be generalizable to all DC/NPA pairs. dc/npa coextension is generalized in this way, but the Williamsonian view is not and cannot be generalized in this way.

5.1. Charge: Difference in Presence of Derogatory Force or Intent

Suppose we grant overlap hypothesis for ‘chick flick’/‘romantic comedy’. I claim that, on the basis of parity, we have pro tanto reason to assume other DC/NPA pairs work the same way. But it might be worried that this pro tanto reason indeed isn’t much of a reason at all, as ‘chick flick’ “isn’t really” a DC. It has been occasionally put to me, for example, that the genre term—qua genre term—isn’t obviously derogatory; or if it is now, that it wasn’t intended to be that way.

Setting aside that many DCs (including some of the most paradigmatic! Consider the onceclinical ‘R-word’) were in fact not originally meant as derogatives, let us grant that either or both of the above hypotheses about ‘chick flick’ is true. dc/npa overlap is equally as plausible for the genre term ‘capeshit (movie)’, an explicitly derogatory expression, coined to be derogatory. Initially popularized on the internet forum 4chan, ‘capeshit (movie)’ (sometimes shortened to ‘cape movie’ or ‘cape flick’) is a derogatory category expression with an intuitive NPA (‘superhero movie’, or ‘comic book movie’). Its online usage over the last decade has become increasingly widespread, as big-budget superhero movies like the Avengers franchise have proliferated.83 And indeed, the connection between it, as a DC, and the expression ‘superhero movie’ (or ‘comic book movie’) is, for competent users, extremely tight. Still, competent users will entertain, if not in every particular instance accept, claims to the effect something is a “superhero movie” but not “capeshit (movie)”, or vice versa:

- (39)

- The Dark Knight is the rare instance of a superhero movie that isn’t capeshit.

- (40)

- It’s a sad fact to come to terms with but Star Wars [though not a superhero movie] is “capeshit”.

Like ‘chick flick’/’romantic comedy’, this is a case where an overlap hypothesis has immediate plausibility. I would even submit that it is obvious, in this case, that familiarity with the relevant stereotypes—and the negative attitudes typically attached to those stereotypes among relevant speakers—is essential for basic competence with sentences like (39) and (40), and likewise for DC-corrections like (80) and (81):

- (80)

- A: The Star Wars movies are capeshit movies.

- B: But they’re not superhero movies!

- A: Whatever, they’re still capeshit movies.

- (81)

- A: Joker isn’t a capeshit movie.

- B. But it’s a comic book movie!

- A: Whatever, it’s still not capeshit movie.

These DC-corrections, just like (76) are immediately comprehensible to speakers with basic competence with the relevant expressions. But to have the requisite competence, it is not enough to simply know that DC ‘capeshit (movie)’ is associated with ‘superhero movie’ and ‘comic book movie’. It may seem sufficient in most contexts where ‘capeshit (movie)’ is used, because in most such contexts, the films at issue are also ones to which ‘superhero movie’ and ‘comic book movie’ obviously apply. But in order to understand exchanges like (80) and (81), one must have a clearer sense of what users of the term ‘capeshit (movie)’ intend to be targeting about the kinds of movies they are expressing contempt for.

Often, this information is left tacit; but occasionally, speakers will make their meaning more explicit:

- (82)

- A: The Star Wars movies are capeshit movies.

- B: But they’re sci fi fantasy movies, not superhero movies!

- A: Whatever, they’re still capeshit movies. They use their content to sell toys and merchandise to man-babies, and actual babies. Therefore since we’re all adults they should not be talked about in a public space.84

- (83)

- A: Joker isn’t a capeshit movie.

- B: But it’s a comic book movie!

- A: Whatever, it’s still not a capeshit movie. Capeshit movies are usually the same rehash “save the planet, beat the baddie.” Joker was babies first Taxi Driver. But at least it was different than most MCU [Marvel Cinematic Universe] & DC films.85

The key stereotypes, here, are features like being about superheroes/characters who have superpowers and wear capes, being about characters based on comic books, being cinematically generic/unoriginal, being cinematically simpleminded/brain-rotting, having lots of prequels and sequels, being over-reliant on CGI effects, being childish, and catering to (the ignorant) masses.86

Crucially, these are stereotypes which competent users associate not just with the DC ‘capeshit (movie)’, but also with the NPAs ‘superhero movie’ and ‘comic book movie’. In this sense, these latter expressions (like ‘romantic comedy’ before and, I submit, NPAs more generally) are not really “neutral” at all, from the perspective of speakers who use the pejorative DC. An overlap thesis grounded in S-overlap predicts this, as it posits overlap not just in user’s associated stereotypes and descriptive beliefs, but also in their negative evaluative attitudes. Still, when they want to, competent users can—and do—recover more a “technical” sense of ‘superhero movie’ (or ‘comic book movie’), where these just mean “movie about superheroes” (or “movie based on comic books”). Thus the speaker of (39) defends The Dark Night:

- (39)

- The Dark Knight is the rare instance of a superhero movie that isn’t capeshit.

Notably, this is also what intuitively happens with ‘chick flick’/‘romantic comedy’ in cases like (2), where a ‘chick flick’-user “defends” a movie which they acknowledge is technically a “romantic comedy”:

- (2)

- Silver Linings Playbook is a romantic comedy, but it isn’t a chick flick.

And indeed, just as with ‘chick flick’/‘romantic comedy’, there is an clear asymmetry in comprehensibility and felicitousness between the above DC-corrections and (84):

- (84)

- A: The Star Wars movies are superhero movies.

- B: But they’re sci fi fantasy movies, not superhero movies!

- A: #Whatever, they’re still superhero movies.

If we find that we can “make sense” of this exchange at all, it is because we force it to, by reading A as meaning something metaphorical by ‘superhero movie’, such that his assertion is consistent with the Star Wars movies not (actually) being superhero movies. But it is the basic relationship between DCs and NPAs, in their literal uses, which we are trying to theorize, here. And if we instead force a literal reading of A’s claims in (84), then his rejoinder obviously crashes:87

- (85)

- A: The Star Wars movies are superhero movies.

- B: But they’re sci fi fantasy movies, not movies about superheroes!

- A: #Whatever, they’re still superhero movies. They’re movies about superheroes.

And as with ‘chick flick’/‘romantic comedy’, this asymmetry is plausibly explained by competent users’ mutual commitment to substantial extensional overlap (grounded in substantial stereotype overlap), but not complete extensional overlap between the DC and the NPA.

5.2. Charge: Difference in Degree of Overlap

Just as nothing turns on the relevant DCs being “mild” or plausibly nonderogative in origin, nothing in the present “overlap” model requires that the degree of overlap be the same for all DC/NPA pairs. It requires only that there be enough E- and S-overlap to allow for a presumption of complete overlap among ordinary speakers. dc/npa overlap is thus more permissive than it might initially have seemed: it is compatible with a range of degrees of the relevant overlap, including ones where the relevant DC/NPA pairs are, intuitively, less extensionally and conceptually tied than ‘chick flick’ and ‘romantic comedy’.

To illustrate, I will now present two cases where the hypothesized overlap, and speakers’ expectations of overlap, profiles differently, viz., ‘mom jeans’/‘jeans worn by a mom’ and ‘dad joke’/’joke told by a dad’. Like ‘chick flick’ and ‘capeshit (movie)’, ‘mom jeans’ and ‘dad joke’ are intuitive (if extremely mild) DCs: they are nominalized group or category expressions with established pejorative uses in certain speech communities. They also have intuitive NPAs: ‘jeans belonging to a mom’ and ‘joke told by a dad’, respectively—where the former picks out all and only the jeans worn by people who are moms, and the latter picks out all and only the jokes told by people who are dads. And these intuitive relationships, like the one between ‘chick flick’ and ‘romantic comedy’ and ‘capeshit (movie) and ‘superhero movie’, seem to involve overlap.

Indeed, as with those previous cases, I submit that it is obvious that these other relationships involve overlap. Competent users of ‘mom jeans’ are obviously committed to substantial but incomplete E-overlap: while they think that some of the jeans worn by moms are “mom jeans” (viz., the worst kind), they also believe that one need not actually be a mom to commit this particular fashion faux pas:

- (67)

- My mom always wearing jeans. Thank god she doesn’t wear mom jeans!88

- (68)

- Lucky Obama doesn’t have a son! How would you like to grow up with a dad who throws like a girl & wears mom jeans?89

Likewise, competent users of ‘dad joke’ obviously believe that while some of the jokes told by people who are dads are “dad jokes”, being a dad is neither necessary nor sufficient to be “guilty” of the jokes in question:

- (45)

- Being a dad with “actually funny jokes and not just dad jokes” might be the best feedback you can get from your kid.90

- (46)

- I don’t understand why Cory Booker tells so many Dad jokes when he’s not a Dad.91

And this commitment among competent users seems obviously grounded in S-overlap between associated stereotypes and attitudes.

In the case of ‘mom jeans’/‘jeans belonging to a mom’, the relevant stereotypes include, among other things, being loose, being high-waisted, and being unflattering. For ‘dad joke’/‘joke told by a dad’, they include properties like being trite, being punny, and being groan-inducing.92 They also, as the explicit etymological connections suggest, include stereotypes more basically associated with ‘mom’ and ‘jeans’ and ‘dad’ and ‘joke’, respectively—for example, being uncool/embarrassing, being made of denim, being silly, and being intended to be funny. Familiarity with these stereotypes is absolutely essential for understanding exchanges like (86) and (87):

- (86)

- A: Obama wore mom jeans when he threw out the first pitch at a White Sox game.

- B: But Obama’s not a mom!

- A: Whatever, he still wore mom jeans. Threw like a girl too.93

- (87)

- A: Ellen’s telling a lot of dad jokes.

- B: But Ellen’s not a dad!

- A: Whatever, she’s still telling dad jokes. Someone tell this woman she’s not funny.94

These, like the other DC-corrections we’ve seen, are felicitous, cooperative exchanges. And like in those other cases, this marks a contrast with the corresponding NPA-corrections:

- (88)

- A: Obama wore jeans belonging to a mom when he threw out the first pitch.

- B: But those were his jeans! And Obama’s not a mom!

- A: #Whatever, he was still wearing jeans belonging to a mom.

- (89)

- A: Ellen’s telling a lot of jokes [being] told by a dad.

- B. But Ellen’s not a dad!

- A: #Whatever, she’s still telling jokes [being] told by a dad.

And once again, this asymmetry is plausibly explained in terms of terms of E- and S-overlap.

Such evidence of systematicity, I have claimed, is prima facie evidence in favor of generality:

generality all intuitive DC/NPA pairs in English are unified by a general linguistic relationship.

But we might worry that (86)–(89) are not actually analogous to the other DC- and NPA-corrections we’ve considered so far. The pragmatic story I proposed for those earlier exchanges appealed to a default presumption among competent users. But we might question whether, in (86) and (87), B’s replies are actually things that a competent user would (in earnest) say.

It is true, of course, that B’s replies in (87) and (88) are, like B’s replies in the analogue exchanges, conversationally relevant; it does not feel random or inexplicable to us, as competent speakers, that B replies the ways that he does. Still, it is significantly less natural sounding, funny even.95 Would a fully competent user of ‘mom jeans’ really be confused, even if only for a second, by the fact that Obama isn’t a mom?

I’m myself inclined to think no, actually. But happily, this poses no problem at all for dc/npa overlap. Recall that the basic linguistic relationship between DCs and NPAs countenanced by that hypothesis involves “substantial” degrees of E- and S-overlap:

DC/NPA overlap for any DC and NPA intuitively linked in meaning, the linguistic relationship between them involves substantial overlap in

semantic extension (E-overlap), and

the stereotypes, beliefs, and evaluative attitudes associated with each expression in the minds of competent speakers (S-overlap)

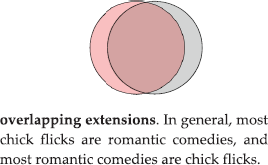

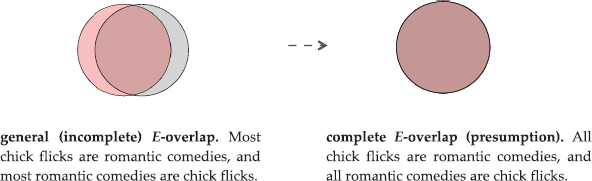

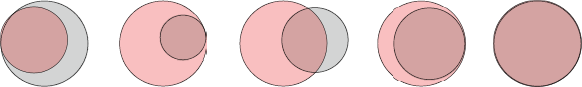

Initially, I illustrated the idea of E-overlap with a Venn diagram wherein only the outermost parts of the circles were not overlapping:

But for any given DC/NPA pair there are many other Venn diagrams we might draw, corresponding to equally as many possible instantiations of “substantial” E-overlap that pair might exhibit:

DC/NPA pairs, in other words, need not all exhibit exactly the same ratios of E- and S-overlap as ‘chick flick’/‘romantic comedy’ for dc/npa overlap to be true. It is consistent with that hypothesis that some DC/NPA pairs exhibit more E- and S-overlap than ‘chick flick’/‘romantic comedy’—even, perhaps, to the point of perfect co-extension—and that others exhibit less.

Hence, “exceptional cases”—occasions on which competent users take one member of a DC/NPA pair to correctly apply but not the other—may be more or less exceptional. Accordingly, it will be more or less conversationally strange for a speaker to presume such “exceptions” are to be bracketed by default. We may thus predict that speakers who are more competent with a given DC/NPA pair will have a stronger grasp on all of the following than speakers who are less competent:

the relevant associated stereotypes and attitudes;

the degree of E-overlap judged by other competent users to obtain between the relevant expressions; and

the norms and use practices of such speakers in ordinary conversation.

It is an intuitive datum that competence with DCs comes in degrees; dc/npa overlap can straightforwardly explain this.

5.3. Charge: Difference in Object/Target Kind

So far, all of the pairs examined in this section have involved group or category expressions for nonhuman objects. ‘Chick flick’ is a term for movies, not people. So why think its relationship to ‘romantic comedy’—whatever that relationship involves—should have any bearing on our thinking about paradigmatic slurs?

The same patterns I have been focusing on extend to DC/NPA terms for human persons or groups. Consider the DC/NPA pair ‘d*ke’/‘lesbian’. It is a prediction of our toy version of Williamson’s conventional implicature theory (and presumably his actual theory, as he intends it), that the semantic relationship between ‘d*ke’ and ‘lesbian’ involves strict co-extension. dc/npa overlap allows that this might be the case—but is only committed to the relevant E-overlap being substantial. And indeed, this latter, weaker prediction seems to accord much more comfortably with the actual practices of competent users.

Take, for example, a sentence like (49):

- (49)

- I always wanted a lesbian friend, lesbian not a dyke.

Anyone familiar with the term ‘d*ke’ as used a DC has almost certainly heard it used the way it is here—namely, to carve a distinction between the “acceptable” lesbians, and the unacceptable ones.

We may even be tempted to suppose for this reason that, contrary to both dc/npa overlap and the Williamsonian co-extension thesis, ‘d*ke’ actually picks out a proper subset of the individuals in the extension of ‘lesbian’ (cf. Ashwell 2016). But this would be to overlook the rest of the relevant data. It would be to overlook the conservative father who, upon learning that his daughter is bisexual, calls her ‘d*ke’ in a rage. And it would be to overlook the casual, commonplace bigotry of utterances like (50):

- (50)

- Not all dykes are lesbians. I got a cousin who’s a dyke but she has a husband.

Even more to our purposes here, it would be to overlook exchanges like (90):

- (90)

- A: Our daughter’s a dyke.

- B: But she’s bisexual, not a lesbian!

- A: Whatever, she’s still a dyke.

Such exchanges, structurally, are just like the other DC-corrections we have seen; and just like those other DC-corrections, they are natural-sounding and immediately comprehensible. Speaker A in (91) is not merely believable as a competent user of ‘d*ke’, but is behaving exactly as those of us who know such speakers have come to expect—it makes no difference to him whether his daughter likes only girls, or not.

Finally, the (regrettable) normalcy of exchanges like (90) again stands in predictable contrast with (91), the corresponding NPA-correction:

- (91)

- A: Our daughter’s a lesbian; she doesn’t like boys.

- B: But she’s bisexual, not a lesbian! She likes boys too!

- A: #Whatever, she’s still a lesbian; she doesn’t like boys.

And again, this asymmetry in felicity is not puzzling at all if our working hypothesis is dc/npa overlap. It is rather puzzling, however, if our working hypothesis is something like our generalized toy version of Williamson’s co-extension thesis, or the proper subset view (hereafter npa subset):

DC/NPA coextension for any DC and NPA intuitively linked in meaning, the linguistic relationship between them involves semantic coextension.

NPA subset for any DC and NPA intuitively linked in meaning, the extension of the DC is a proper subset of the semantic extension of the NPA.

dc/npa coextension predicts that ‘d*ke’ and ‘lesbian’ are extensionally equivalent in literal uses—that is, that all and only lesbians are d*kes—and that competent users know this; npa subset predicts that all literal referents of ‘d*ke’ are lesbians—but not all lesbians are literal referents of ‘d*ke’—and that competent users know this. So for either hypothesis to be correct, speakers like the conservative father in (91) must be confused about the meaning of ‘d*ke’, or using it in a nonliteral way. We should reject the former out of hand. Speakers like the conservative father, and utterances like (49) and (50), are not strange or idiosyncratic; as I have taken some pains in this paper to show, they are utterly banal. To dismiss such cases as confused or semantically defective is to posit rampant linguistic incompetence within the very speech communities supposedly at issue—viz., communities wherein the target DCs are actually, routinely used. Methodologically, this is a nonstarter.

The latter proposal, that utterances like (49) and (50) and exchanges like (91), involve nonliteral uses of the relevant DCs, is more serious. Still, I don’t think we have reason to prefer it over an overlap-theoretic alternative.

6. Why Not Say It’s Metaphor?

Probably no one actually accepts dc/npa coextension in its full generality—but many extant theories do entail that ‘lesbian’ and ‘d*ke’ are truth-conditionally equivalent in literal uses. And if one arrives with such prior theoretical commitments, a natural response to the data I have presented is to ask: why not say it’s metaphor? Perhaps uses I have been focusing on are simply nonliteral. Indeed, if we’re antecedently committed to something like Williamson’s conventional implicature view, then we have to say such data involves nonliteral uses. Sentences like (92) and (93) cannot, if ‘d*ke’ and ‘lesbian’ are extensionally equivalent, be literally true:

- (92)

- She’s a dyke but not a lesbian.

- (93)

- She’s a lesbian but not a dyke

So, if we think something like Williamson’s view is true for DC/NPA pairs like ‘d*ke’/‘lesbian’, then we have reason to think uses like those in (93) and (94) are contracted and extended, respectively.96

But do we have independent reason to think this?

As a first pass test, I offer that competent speakers generally grasp when they are speaking metaphorically. Indeed, it seems we pronounce a metaphor “dead” precisely when and because its “nonliterality,” however retrievable it may still be in principle, has now been so fully lexicalized away as to go virtually unnoticed in practice (e.g., ‘mouth of the river’). “Live” metaphors, by contrast, have a distinct “figurative feel.” For example, consider (94):

- (94)

- A: Jack’s a girl.

- B: But Jack’s a boy!

- A: Whatever, he’s still a girl. He cries all the time and can’t take a joke.97

As competent speakers of English, we know by the end of this exchange that A intends a nonliteral meaning of ‘girl’. Moreover, we have an intuitive sense of the way that B is failing to understand when he attempts to correct A—viz., by taking as literal an utterance which (in retrospect) was clearly supposed to be figurative. It is simply obvious to us, by the end of the exchange, that a literal reading of ‘Jack’s a girl’ is not available—even if it might have been initially.

Indeed, as hearers, we may reasonably wonder at the beginning of (94) about the intended literality of A’s initial claim. But once we imagine that we are A, there is simply no question of how ‘girl’ is being used. To say that that Jack is (literally) a girl and to say that Jack is (figuratively) a girl are two very different things—whether we are saying one or the other is something that we, as competent speakers, would know.

So if the uses of DCs in sentences like (49) and (50) and exchanges like (90) are in some sense metaphorical (either extended or contracted), then either (a) they are metaphorical in the sense that “dead” metaphors are metaphorical, or (b) they are “live” metaphors.

- (49)

- I always wanted a lesbian friend, lesbian not a dyke.

- (50)

- Not all dykes are lesbians. I got a cousin who’s a dyke but she has a husband.

- (90)

- A: Our daughter’s a dyke.

- B: But she’s bisexual, not a lesbian!

- A: Whatever, she’s still a dyke.

If (a), then DCs in sentences like (49) and (50) and exchanges like (91), like ‘mouth of the river’, are (now) fully-lexical terms in their own right, with a (literal) semantic relationship to NPAs which is (still) prima facie best explained by an overlap thesis. If (b), then DCs in sentences like (49) and (50) and exchanges like (90) aren’t fully-lexical in their own right, and the speakers behind those DCs generally realize—in virtue of being competent users, as again we ought to assume—that they’re speaking metaphorically.

Whether views like Williamson’s are more plausible than overlap views turns on whether this latter prediction about DC-users’, and in particular slur-users’, knowledge and intentions is true. And for what it’s worth, as someone who grew up around such speakers, I do not think that it is. As someone raised around slur users, I think I know what they mean when they say things like (49) and (50), or (51) and (52), or when they use the n-word.

- (51)

- There are gays and then there are faggots.98

- (52)

- Whoever decided to allow transgender faggots in the military is a retard.99

The supposition that such speakers—like A in (95) with ‘girl’—are knowingly and intentionally using the relevant slurs in nonliteral ways strikes me, frankly, as wildly implausible. They are simply using them, as they do, in the way that they take them to mean.