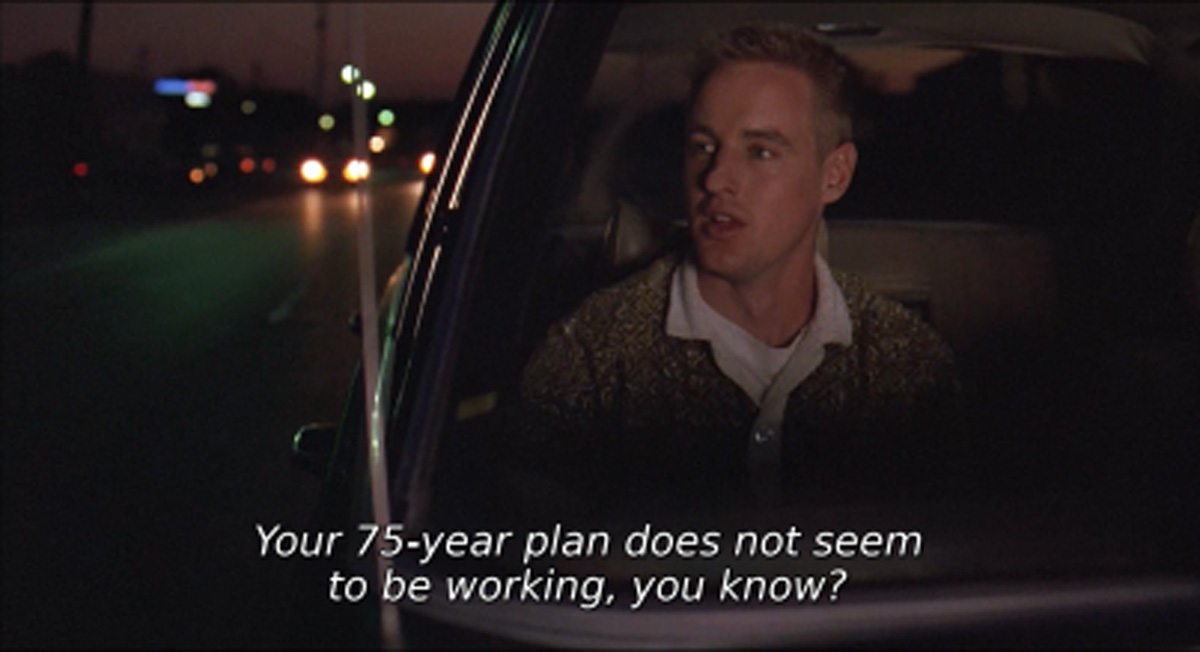

When you watch a movie, it’s usually possible to reconstruct, from each shot, a location from which the image is being presented. We’ll call this the perspective spot.2 At this stage, we are assuming only that if viewers were prompted to identify the place from which a scene is being presented, many of them would describe the same location. This could only happen if there is some information embedded in film sequences that allows this convergence. For instance, in this still from the film Bottle Rocket, this spot is outside the car, on the passenger’s side:

There are two things to note about the perspective spot. First, it is a location in the space of the film, not in the space of the viewer nor the actual location of filming. This is especially clear in animated films, since the spot from which the scene could have been observed would have to be in the world of the film, and thus not in any real space. Second, the location is not that of the actual camera (though it might coincide with the camera’s location). In the still above, the camera might have been placed much further from the car and zoomed in; nevertheless, we can pinpoint the perspective spot just based on how the clip is presented visually.

So, who, if anyone, is experienced as located at the perspective spot? Different films and scenes seem to point towards different answers. In the still above, it’s clear that no one, or at least no normally embodied person, could be in the perspective spot, since any such person would have to be floating outside a moving vehicle. And a person viewing the scene would likely not find this perspective spot location jarring, nor feel a sense of concern for the imagined observer dangerously exposed to speeding cars. While it’s easy to identify the perspective spot, there is no temptation to think about that spot as occupied by anyone, even a camera.

But now consider this second sequence from the same film:

This scene takes place as two characters at the fence are waving goodbye to the blond man in the prison uniform. We see them standing and watching from the fence in the first frame, and then we see the second shot, which goes on for quite a while as the prisoners file in through the door. This sequence sends a clear narrative message: the two characters on the other side of the fence are there, lingering and watching the prisoners enter the building. This message is conveyed by the fact that the perspective spot suggests the perspective of these characters. It tells us they are watching, by presenting the scene from their perspective. Interestingly, it doesn’t require any kind of heavy-handed cinematic technique to introduce this suggestion, just a correspondence between the perspective spot and a location occupied in the film by a character.

These two examples illustrate the difficulty of our question of who, if anyone, is experienced as located at the perspective spot. First, taking the examples at face value suggests that the two simplest answers are wrong: the perspective spot is neither experienced as always occupied nor as never occupied. Second, there are many different modes of experiencing perspective in film, which we seem to switch between effortlessly. Finally, a third aspect of the question emerges when we examine the experience of the last frame: in addition to learning that the other characters have remained to watch the prisoners file away, an observer might also have the experience that she herself is there behind the fence, watching and lingering. This impression is compounded by the fact that this is the final scene in the movie, which can be fairly easily predicted by a combination of sound and narrative cues. So, the viewer is watching the prisoners walk away, thinking about the characters waiting a little too long in saying goodbye to their friend, as she is also watching the film end and in a second-order sense watching the characters leave. If this is right, she thinks of herself as both inside the film, in the perspective spot watching the character move away from here, and outside the film, watching the world of the film move away from her. Of course, one or both of these senses of her taking a perspective might be more metaphorical than literal. But, this brings out the third aspect of the question: just as our film experience seems to have both occupied and unoccupied perspective points, the sense of occupation seems to both implicate the actual viewer in addition to the characters, and also to remain separate from the viewer.

One more thorny issue before we turn to answers to the perspective spot question. This question is about film experience, but following others in this debate (Currie 1995; Terrone 2020), we take the important question to be the normative question about a kind of experience mandated by or made apt by the film, rather than about the average experience or any particular viewer’s actual experience. The idea of a mandated or apt experience is a thorny one: on the one hand, this experience should neither be equated with a vision in the mind of the creator of the film, nor reduced to what happens to be understood by the audience. We won’t make an intervention or take up a position in this debate beyond acknowledging that it is a complex normative issue.3 Our approach is to focus on film examples whose proper or apt experience is relatively uncontroversial and, in this way, to evade some of these complexities.

In what follows, we’ll first argue for subject pluralism, the view that film experiences are sometimes personal (i.e., subjective) and sometimes impersonal (i.e., objective) (§1). Then we’ll argue that in at least some cases, the subject represents a subjective perspective that is not indexed to her, the viewer, nor to any character in the film, nor, indeed, to any individual whatsoever. This kind of representation we dub unindexed subjectivity (§2).4 We then discuss how these theses support and are supported by the embodied and multi-modal nature of film experience, and the way in which they place cognition of film on a continuum with more familiar forms of cognition, such as memory and mindreading (§3).5

1. In Favor of Subject Pluralism

In philosophy of film, a central question is whether films typically mandate that a viewer experiences herself as located where the perspective spot is. We have already suggested that we take this question to have a false presupposition: There is no ‘typical’ for film, as some films mandate that the viewer experiences herself as located in the perspective spot and others do not. In what follows, we will make good on this suggestion by criticizing two contrastive and prevailing views of who is located at the perspective spot, and the second is the view that in general, film experiences do not mandate that the viewer experience anyone as located at the perspective spot. Theorists who presume film experiences to mandate an experience of the viewer as herself located at the perspective spot include: Mitry (1965), Wilson (1986; 2011), and Curran (2016; 2019). Theorists who deny this and hold that the experience is always or normally impersonal include Currie (1995; cf. Currie 2011) and Lopes (1998). Terrone (2020) develops a nuanced view, on which film experience typically mandates that the viewer imagines being a disembodied subject who can perceive the events in some fictional world—that is, there is a single (normal) type of experienced perspective, but one that is not exactly personal or impersonal.6

In contrast to these views, we’ll follow theorists such as Gaut (2010) and Smith (1997; 2022a; 2022b) in arguing for pluralism. Gaut defends a mixed view, on which film experience is typically impersonal but sometimes mandates that one experiences oneself as located at the perspective spot (see, esp., Gaut 2010: ch. 5). However, in contrast to Gaut, we make no claim about whether there is a “default” perspective (and indeed we doubt that there is such a thing). Our motivations are also wholly distinct from Gaut’s.

Smith’s view is much closer to our own, in that he acknowledges that both impersonal and personal imagining play a central role in film experience.7 We are also sympathetic to Smith’s motivations which involve, in part, the need to explain the emotional, perceptual, and bodily identifications which film experience can afford. However, our view goes beyond Smith’s pluralism, in that we argue that the subjectivity mandated by film is sometimes indexed to no one at all.8

Ruling out two extremes, where there is always or never the experience of a person at the perspective spot across film experiences, does not in itself show that pluralism is true. However, as we will show, each of these unified views reflects something accurate about some film experiences, and so pluralism is an attractive way to preserve these explanatory advantages. The more variety we observe between sequences with respect to subjectivity, the more plausible pluralism becomes over a view on which there is still a typical or uniform experience but one that sits somehow between personal and impersonal perspectives.

Why think that films generally mandate that the viewer experiences herself as located at the perspective spot? The motivations for this view are many. One comes from the felt intimacy of the film experience, an intimacy which is not necessarily present in non-visual art forms, such as written, or more broadly verbal fiction. One simply feels that one is there, lying next to the soldiers in the battlefield as they die, or watching the newly widowed man weep on a bed, or hearing the ecstatic crackling of fireworks in the distance. Film permits a presence and an intimacy which, one could argue, would be hard to achieve were it not the case that film experience somehow mandates that one experiences oneself as located there, between the soldiers, next to the mourning spouse, or in the field below the fireworks. Call this the ‘felt presence’ motivation.

Consider how particular sequences seem to support the ‘felt presence’ motivation. For instance, consider the famous ‘shower scene’ from Psycho (1960), in which Norman Bates faces a shower with a wielded knife, ready to stab Marion Crane. The sequence involves close-up shots of Norman Bates with his knife raised high, obscured only by a thin veil of flowing shower water. The perspective suggests Crane’s perspective, but it also arguably elicits an experience in the viewer in which she experiences herself as located at the perspective spot, herself ready to receive terrifying blows from the killer. In favor of this suggestion is the fact that many viewers who watch this scene experience fear; indeed, they might even clutch the seat of their armchair, scream, or jump. This is, presumably, a mandated aspect of the film experience. Of course, the viewer knows she is not endangered, but some suite of emotional and bodily experiences gives rise to a felt sense of her own bodily endangerment. The view that films mandate that a viewer experiences herself as located at the perspective spot can straightforwardly explain this fact; the viewer experiences herself as there, as roughly where Crane is.

Notice that the experience of this sequence in Psycho does not merely disclose a visually encoded vantage point. The experience of fear is not just a felt presence near Crane, but a bodily experience of elevated heartrate, indrawn breath, a proprioceptive awareness of one’s own physical position, along with a set of visual and auditory sensations. This experience involves action as well: for instance, you might draw back into a protective posture, a motion driven by some awareness of your initial sitting position. These experiences are, at least very roughly, of the kind that a normally embodied human being would have. So, we take it that it is not a mere indexed mapping of visual information that is disclosed. It is a kind of subjectivity, or at least a partial one, that the viewer is meant to represent.

Here is another sort of sequence which seems to support the view that film mandates that the viewer experiences herself as located at the perspective spot. In Drinking Games (2012), several sequences utilize erratically spinning shots in a small room where other characters are inebriated, suggesting the dizzying effect of alcohol. The film itself seems to mandate this experience, and it is hard to explain how the spinning shots could achieve this effect without the film also mandating that the viewer experience herself as located at the perspective spot, a spot which is in this sequence, rapidly shifting location and course.

What, then, of the opposite form of singularism in the literature, the view that films typically do not mandate that the viewer experiences herself as located where the perspective spot is? Advocates of this view sometimes point out that if the viewer experienced herself as located in this shot, this would disrupt the narrative in certain bizarre ways. One would have to represent oneself as an additional, hidden, silent character in the film, as a hidden individual lying next to the soldiers in the battlefield, as an invisible voyeur watching the grieving spouse, and so on (Currie 1995). So, it would seem that this view suggests bizarre and unexpected additions to the narrative element of the film. Indeed, taken to its furthest conclusion, this view might even suggest that the narrative of the film varies depending on who is viewing it. For when Ella watches the film, she represents herself, that is, Ella, as an invisible additional element in the film, but when Minou watches the same film, she represents herself, that is, Minou, as an invisible additional character in the film. This would be a bizarre result indeed.

Advocates of the view that films typically do not mandate that the viewer experience herself as located where the perspective spot is are also quick to point to sequences where it would seem bizarre to think of oneself—or anyone—as there. For instance, Currie draws on the phenomenology of certain typical sequences to make this case. Consider, for instance, a scene in The Birds, one which depicts a woman in a boat, paddling with an oar in order to make her way to a dock, where a man awaits her. This sequence involves close-up shots of the woman in the boat, further away shots of the woman in the boat, and shots of the man waiting for her on the dock.

Currie suggests that in watching scenes such as these, were we to experience ourselves as located where the perspective spot is, we would experience ourselves as moving frantically between multiple locations; such as between the dock where the man is located and the boat itself. But, in this particular, rather prosaic sequence, we don’t experience ourselves as moving. We simply track the woman’s movement.

Here, then, we have the makings of a puzzle. On the one hand, film seems to facilitate a certain intimacy with another world, in the sense that it seems to present events and characters as here, that is, as just in front of us. And some sequences, such as fear-inducing sequences like the shower scene in Psycho or dizzying sequences, such as those in Drinking Games, seem to not merely implicate our bodily experiences in a causal way but to demand of the viewer that she have certain emotional or proprioceptive experiences of the kind that would be easily explained if she experienced herself as present at the perspective spot. These observations motivate the view that in general, films mandate that the viewer experiences herself where the perspective spot is. On the other hand, if films mandate that viewers experience themselves as located where the perspective spot is, this suggests that the viewer herself is a constantly present but causally and truth-conditionally inefficacious element of the film’s narrative, which is a bizarre result (for instance, the viewer’s presence would make assertions like “I’m the only one in the room” always false when said by a character near enough to the perspective spot).

Moreover, some sequences, such as close-up shots and familiar shot-reverse-shots, do not seem to suggest that we experience ourselves as located where the perspective spot is. Indeed, at least some such shots do not signal that any subject is ‘present’ at the perspective spot. Consider, for instance, establishing shots, which are typically exterior shots taken of a cityscape or neighborhood. While such shots have an identifiable vantage point, they do not signal, either through integrated perceptual cues or emotional cues, any kind of subjective representation. We take these shots to typically mandate non-subjective, that is, impersonal representations.

Together, all of the preceding considerations support a thoroughgoing pluralism about who, if anyone, is experienced as present in the perspective spot. In some cases, films mandate that the viewer experiences herself as located where the perspective spot is; in some cases, films mandate that the viewer experiences a character as located where the perspective spot is; in some cases, films mandate that some unspecified individual is located at the perspective spot, and in some cases, films mandate that no one is located at the perspective spot because in such cases the ‘perspective spot’—so-called—does not signal a perspective at all. Rather, it merely centers some impersonal vantage point.

More particularly, our overall view is that film experience can mandate the full range of representations glossed in the figure below. On our view, representations mandated by film experience can be subjective or non-subjective, that is, impersonal. Among subjective representations, some are indexed to the viewer, some are indexed to someone else, such as a character or even, potentially, a narrator or the director herself. Moreover, as we will now argue, in at least some cases, films mandate representations of unindexed subjectivity, where these are representations that are encoded in the first-person and yet are not indexed to any particular individual:

2. The Unindexed Subjectivity View

As we’ve noted, theorists who take first-personal representations to figure in film experience typically presume that these experiences are indexed to you the viewer, not to a character in the film or to no one at all. This fact is intelligible against a backdrop in which it might seem that it is a conceptual matter that subjective representations are invariably indexed to oneself, that is to the person whose representation it is. In the context of a discussion of point-of-view sequences, Walton writes:

Whatever one prefers to say, in the various kinds of cases in which a depiction portrays things from a character’s perceptual point of view, about whether the spectator imagines being identical to the perceiving character, what is important is that she share the character’s perspective. She participates in a visual game of make-believe using part or all of the depiction as a prop, and it is fictional that she sees in a way in which, fictionally, the character does-whether through the character’s eyes or her own; she imagines seeing thus. (1990: 348)

Subjectivity involves the representer herself as part of the representation—it is part of the fiction that she sees. We call this the classical view of subjectivity in film experience.

We will argue, contra this classical view, that some subjective representations in film are not one’s own and indeed, are not anyone’s at all. On this view, films at least sometimes mandate representations of unindexed subjectivity, where these are subjective experiences not indexed to any particular individual. For instance, in at least some cases, a film might mandate, via auditory, perceptual, proprioceptive, or other cues, that a viewer represent, ‘from the inside,’ walking through a fog-cloaked Italian vineyard. However, at times, the viewer will not represent that she herself—the individual watching the film—is walking through the vineyard. Rather, in such cases she will represent this scene in a subjective way, ‘from the inside,’ but in a way that is neutral as to whether the subject of that experience is her, a character in the film, or even anyone at all. In these cases, the ‘I’ in this experience, the experience which ‘says’ ‘I walk through the vineyard,’ is not indexed to any particular individual. The ‘I’ in the representation is much like an unfilled variable. We call these representations of unindexed subjectivity.

Recall that while we acknowledge these unindexed subjective elements in film experience, in other cases, the viewer’s film experience does not involve a subjective presentation of the scene at all; in such cases, she imagines a scene in an impersonal manner. For instance, an establishing sequence of a city-scape typically mandates an impersonal representation, but these should be carefully distinguished from unindexed subjective representations. We provide examples of the latter shortly.9

Recall further that subjectivity in the sense we are interested in is not merely a visual centering or perspective point. Rather, subjectivity in our sense will typically involve the integration of cues from multiple sensory cues—including, in some cases, visual, auditory, and even kinesthetic cues—along with, in at least some cases, an emotional centering. So, it is more than a vantage point or a mapping of information with a privileged location.10

A further specification of the unindexed subjectivity view as we will develop it here is that subjectivity is at least sometimes encoded in the structure of unindexed subjectivity. That is, we find the first-personal perspective principally in the way content is presented, not in the content itself. This in fact explains why unindexed subjectivity is possible: it’s quite bizarre to imagine the properties of the vineyard itself signaling that someone is watching, without conveying who that person is. But the insight we take from de Vignemont and others is that the same need not be true for the mode of presentation: elements of an ordinary visual scene can and do convey a subjective perspective, but through the way the content is presented rather than the content itself.

In the case of film, this structure/content distinction lines up to some degree with a semantics/syntax distinction, though we employ the former rather than the latter out of a suspicion that this distinction in the case of language is much sharper than the cinematic or perceptual one.11 That is, sentences like “I am here” and “Minou is in San Diego” have the same contents when suitably filled out even though they differ in syntax, whereas it is more challenging to find two visual presentations, one indexical and the other not, that would be accurate and inaccurate under exactly the same circumstances. Presumably this is because semantic vehicles are for the most part arbitrary whereas cinematic vehicles are less so.

A closer link can be drawn between fiction films and literary fiction. With some exceptions, the book or the film as an object does not exist in the fictional world. This means that ways of conveying content through the properties of that object can come apart from features of the fictional world. In the case of the novel, these features might involve a first- versus third-personal narration, the use of ornate language and metaphor, and so on. In the case of film, these could be camera angles and movements, soundtrack, and number of cuts. So, imagine a situation where a clandestine meeting occurs in public. Through film, we can convey that this meeting is risky by showing it from a human-height perspective at a neighboring café (implying that the characters could be observed) or by the use of a suspenseful score. In the novel, we might instead have a narration that is staccato and draws attention to many features of the scene, conveying a similar anxious mood and drawing attention to the nature of the space as public. Both of these are structural in that they do not strictly speaking create the impression of observability by presenting some new fact about the fictional world. However, in context, “purely” structural features often heavily imply content, and content feeds back into structure: shooting the scene from the nearby café might imply that someone is at that particular café, and the staccato mode of narration might imply that a particular character is nervous. Both of these are states of the world. Conversely, we might heighten an anxious mood by showing a passerby’s anxious facial expression: this brings about a mood in the audience in a way that is almost structural, though it starts from presenting content.12

Do these considerations invalidate the structure/content distinction? Not exactly. We can instead relativize the distinction to a particular content. That is, with respect to presenting the meeting as potentially observed, the anxious face and the anxious score present this content structurally. With respect to presenting the people in the café as anxious, the anxious face does so through content and the score does so through structure. Thus, features of film are not absolutely divisible into structure and content, but when we are asking how a particular impression is mandated, we can divide features into roles based on structure and content. The only difference, then, that singles out the “structural” features listed above, such as the third-person narrator or anxious score, are that they are liable to never play the content role since the world of the film or novel does not in general contain the narrator, camera angles, or score.

Some theorists will find the notion of unindexed subjectivity an incoherent one. They will maintain that no representation can signal subjectivity if that representation does not also signal which particular individual is the subject of that representation. We maintain that while the notion of an ‘unfilled in’ subjectivity might be an odd one, it is not conceptually incoherent; there is nothing logically impossible, for instance, about a representation which is in a subjective ‘mode’ and which leaves open which particular subject occupies that mode.13

Moreover, even if unindexed subjectivity were incoherent, it would not follow that we cannot represent this subjectivity, and our claim pertains merely to the representation of an unindexed subjectivity, not to its metaphysical possibility. If we can imagine or otherwise represent what is not possible, then even if unindexed subjectivity is incoherent, this would be no barrier to our claim that the representation of unindexed subjectivity sometimes figures in film experience. The claim that we can imagine what is impossible is a long-standing and contentious one and not one we aim to settle here, but we merely note that there are some prima facie reasons to support this claim, such as evidence that we parse and understand impossible fictions—in at least some sense of ‘understand.’14

We will suggest two different arguments in favor of the unindexed subjectivity view, the view that, in at least some cases, mandated film experience elicits a subjective experience unindexed to any particular individual. The first appeals to a phenomenon we call perspective divergence, wherein a film suggests a kind of embodied presence at a perspective spot without any narrative implication that anyone is there—and in fact, with narrative-based reasons suggesting that no one could be there. The second argument appeals to the phenomenon of what we call post facto point-of-view shots—these are point-of-view shots which are marked as indexed to a particular character after some sequence, instead of during or before that sequence.

2.1. The Argument from Perspective Divergence

In Nanni Moretti’s semi-autobiographical film Dear Diary (Caro Diario), we spend much of the first act following the protagonist (also named Moretti) on his Vespa as we hear his first-person narration. The protagonist is usually in the shot, so we are not seeing things from his perspective. According to the narrative, there is no character there behind him. And yet, consider the following frame, as Moretti visits the site where Pasolini was murdered:

Two elements of this sequence are relevant for our argument: first, the camera, as we follow the scooter, shakes and moves as though it is itself on a moving vehicle. It gets closer and farther from the character as someone driving behind him would and follows a path consistent with a vehicle staying on the road. Second, in one moment captured above, as the camera passes the woman on the left, she looks directly at us. These two elements create the sense of a subjective perspective at the perspective spot: someone is there. These elements contrast with another scene earlier in the same act, where we see Moretti from far away:

Here, there is no suggestion that someone is present in the perspective spot.

But who is present in one scene and absent in the other? In the broader context, it could not be an actual car always gliding behind Moretti—he’s calm and never looks back, even when the camera moves in more closely or when both Moretti and the camera come to a stop. Unlike the shot from Bottle Rocket, then, we don’t use the perspective spot to infer narrative information about what the characters observe.

But it’s not right to say the perspective is unoccupied. Most obviously, the woman looking at the camera indicates that in a sense, someone embodied must be there. This is an example of a content clue. And structural elements signal that the shot is occupied by someone embodied as well—for instance, the camera movements suggest the “observer” is driving on some kind of vehicle, though at times we seem higher up than Moretti himself is on the Vespa. The contrast between this and the birds-eye shot in the second scene reveals a sense of presence in the first scene, and absence in the second.

Is the viewer herself represented as present, then, riding behind Moretti? Certainly not as a narrative element. Unlike a true fourth wall break, this momentary gaze does not give us the sense that we are being seen and addressed. Note that in the final act of the film, Moretti does talk directly to the camera, and it is a surprising shift from the distance of the Vespa episodes. The woman glancing at the camera might even strike us as a kind of joke or accident, given how fleeting it is. Another way to interpret the sequence might be that we are seeing through the eyes of Moretti’s later self as he remembers his trip to Pasolini’s memorial. But this could be true in both sequences—we sometimes remember ourselves from far outside, and without the sense of being someone watching ourselves.

So, in this pair of sequences, we see that the structural elements of film can be used to suggest a subjective perspective—in this case by camera movements and location. We also noted that a content element produces a similar signal in the attention of the woman passing by. We feel that someone is there, an embodied person in a vehicle. But at the same time, outside of this one suggestive glance by the woman on the street, in the narrative of the film, there is no one there. These narrative elements of the film do not suggest an observer, and in fact rule out the presence of an observer.

Reviewers of the film often comment on the intimate feeling evoked by these sequences. For instance, a Guardian reviewer remarks: “calling Dear Diary up close and personal doesn’t really do it justice” (Dickson 2011). This supports our interpretation that the subjective style of these sequences creates a sense of being there at the scene—across the whole of Act 1 of Dear Diary, we follow Moretti on his Vespa and almost feel as though we are also on a trip. A New York Times review notes that the first act is “shot in a deliberately simplistic fashion to evoke an almost home-movie amateurism.” Relatedly, a New Yorker review notes “In the process [of the film], he [Moretti] realizes a longstanding, if unstated, ideal that runs through the history of the modern film: to be able to tear pages from a cinematic notebook and paste them onscreen as a finished work, the way that modern painters can do with their sketches” (Brody 2015). These comments both reflect the sense that this film, while a fictional depiction, brings us closer to the process of filmmaking itself.

Could the subject here actually be the cameraman? For instance, if Dear Diary were a documentary, we might think that rather than an unindexed subject, the style of filming clues us in to the presence of a person behind the camera. This is especially clear in documentaries where we hear the voice of someone near the cameraman conducting an interview with the person on camera. In the case of a documentary, the subject is a person both in the film and in the real world, whereas a similar sequence in a ‘mockumentary’ would position a character in the world of the film as the subject, such as the fictional filmmaker Marty in This Is Spinal Tap. However, Dear Diary is not a documentary: we never hear anyone behind the camera, we don’t see film equipment, crew or so on, and there is no narrative element that references what we see as part of a film in the world of the movie. However, the film does have a variety of metacinematic elements, including a character in the second act who is obsessed with television, the ending sequence with direct eye-contact to the camera, and a through-line in the first act about Moretti’s obsession with the actor Jennifer Beals and the movie Flashdance. The semi-autobiographical nature of the film also shares something with a documentary, as well as the framing as a diary. But a film-diary differs from a classic documentary in that Dear Diary presents Moretti’s world to us without presenting him as creating the footage or indicating anything about who else would be doing so. As the New Yorker review quoted above suggests, the film is something like a deliberately unfinished sketch of a traditional film, rough around the edges and bearing the more visible marks of the creator, but not a different kind of representational object entirely. Thus, these Vespa sequences of Act 1, including the Pasolini sequence we’ve been discussing, are cases of perspective divergence: they evoke a person’s perspective and position at the perspective spot without presenting that person as anyone in particular, including a cameraman, film crew, or similar.

How can we explain this phenomenon of perspective divergence? We might claim that this is simply an incoherence in film experience, a sense in which in the narrative of the film, there both is and is not a subject in the relevant location. Or we might attempt to explain the phenomenon away by redescribing the sequences above to allow either a specific, indexed subject or an impersonal perspective, but not both of these. We maintain that the unindexed subjectivity view provides a superior explanation to these alternatives, one that does not force us to attribute an incoherent narrative to the film and one that does not force us to brush away all of the seemingly incoherent aspects of the sequence. Namely, the Dear Diary Pasolini sequence mandates an unindexed subjectivity, a perspective that is, in the narrative of the film, both subjective and yet not indexed to anyone in particular.

To appreciate the point that the unindexed subjectivity view best explains the Dear Diary sequence, it will be helpful to say something about different forms of signaling subjectivity and when those figure in an incoherent narrative and when they do not. Unindexed subjectivity naturally makes use of the structure of experience, just as implied by the term “unindexed,” which points to a structural feature. It is a structure in the sense that the idea of the unfilled variable picks out a format or organization to the representation, not part of the content of that representation (because of course the content can’t be filled or unfilled—it’s content that does the filling).

If we can invoke these structures in film, our view predicts that there should be cases of bare subjectivity without a particular subject, which is exactly what we see in the case of Dear Diary. Further, this bare subjectivity should be signaled by structural or syntactic features, rather than semantic ones: there is a very different kind of subjectivity one might imagine at the narrative level. For instance, in Italo Calvino’s novella The Nonexistent Knight (Il Cavaliere Inesistente), we are introduced to the titular character in the following exchange:

“I’m talking to you, paladin!” insisted Charlemagne. “Why don’t you show your face to your king?”

A voice came clearly through the gorge piece. “Sire, because I do not exist!”

“This is too much!” exclaimed the emperor. “We’ve even got a knight who doesn’t exist! Let’s just have a look now.”

Agilulf seemed to hesitate a moment, then raised his visor with a slow but firm hand. The helmet was empty. No one was inside the white armor with its iridescent crest.

In this passage, Agilulf is described as seeming to hesitate, which we might say of a robot or other entity without subjectivity. But Agilulf clearly has an internal life:

Agilulf tried to control himself, to limit his interest to particular matters which would fall to him the next day, such as ordering arms’ racks for pikes, or arranging for hay to be kept dry. But his white shadow was continually getting entangled with the guard commander, the duty officer, a patrol wandering into a cellar looking for a demijohn of wine from the night before. Every time Agilulf had a moment’s uncertainty whether to behave like someone who could impose a respect for authority by his presence alone, or like one who is not where he is supposed to be, he would step back discreetly, pretending not to be there at all. In his uncertainty he stopped, thought, but did not succeed in taking up either attitude. He just felt himself a nuisance all round and longed for any contact with his neighbor, even if it meant shouting orders or curses, or grunting swear words like comrades in a tavern.

He tries to control himself, feels a nuisance, experiences uncertainty, and so on. Agilulf then is a kind of bare subjectivity as well: he explicitly doesn’t exist (and subtextually, is a kind of construction of chivalric norms), and yet, he is the locus of a subjective viewpoint. We know this because it is told to us as part of the content of the story, an assertion about its world.

Imagine a film version of The Nonexistent Knight with a voiceover or other direct signaling of Agilulf’s paradoxical existence. This film would have a content-based version of a bare perceiver, a subjectivity without a real subject. The alternative explanation we gestured at above, that perspective divergence is a standard kind of narrative incoherence, would treat the case of Agilulf and of the Pasolini sequence as the same phenomenon. But this explanation has serious downsides. First, while certainly many works of art are deeply incoherent in important ways, the burden of proof should be on the theorist to show that a particular case is truly incoherent, since this style of explanation is so weak that it can be applied in almost every context. Why is this kind of incoherence possible? And why should it so easily be triggered in a context that is not particularly esoteric, jarring, ironic, or avant-garde?15 This is especially clear when we contrast the Pasolini sequence with The Nonexistent Knight, since the latter is patently absurd, whereas the former is not.

Second, there is a different intuitive feel between these cases, arising from the fact that the Pasolini sequence uses subjective presentation to express something non-perspectival about the fictional world, whereas the Agilulf passages communicate the idea of a bare perspective. On our theory, we don’t typically represent the idea of a bare perspective but merely take up such a perspective at times when experiencing film. In this sense, our theory, as we’ll shortly discuss, has far less of a meta-cinematic character than many of its competitors.

In this section, we’ve argued that films sometimes present a point of view as subjective through camera motions, sound cues, camera position, and other structural devices even when it’s no part of the content or narrative of the film that anyone is in the perspective spot. This is actually a prediction of the unindexed subjectivity view: that in at least some cases, film experience mandates an embodied subjective perspective even without a fact of the matter as to whose perspective it is. Where other accounts struggle to come up with a content-based sense in which the observer is there but not there, the unindexed subjectivity view suggests that it is not a form of complex representational metaphysics that explains this sense of there-but-not-there, but instead that the divergence arises from two fundamentally different ways of conveying an observer: through content, and through the structural representation of subjectivity.

2.2. The Argument from Meta-Cinematic Inferences

Our second argument for the unindexed subjectivity view comes from certain inferences viewers are meant to make about certain point-of-view sequences. In some cases, these representations of unindexed subjectivity serve an evidential role in generating inferences about which perceptual experiences are had by individuals in a narrative. We will suggest that the unindexed subjectivity view offers a better explanation than the classical view of how viewers easily form inferences about what we call post facto point-of-view sequences. These are sequences which are presented from a character’s point of view but which aren’t signaled as being from a character’s point of view until after the sequence.

Often, the fact that point-of-view shots are perspectives of a character is signaled by information in the shot itself or else by information given prior to the shot. For instance, a character might be shown looking through a tube at a skyscraper, and the next shot might be of the skyscraper presented as from a low angle, wrapped in what look to be the dark corners of a tube. In this case, the shot of the character looking through a tube helps the viewer determine that the subsequent shot is a perspective of the character. Or, a sequence of Clarice Starling moving slowly through a room, the whole scene tinted green, wrapped in two dark partial orbs, suggests that we are seeing her, in the dark, through the point of view of the killer she seeks, who is wearing night goggles. In this case, information present in the point of view sequence itself helps to indicate to the viewer that what is presented is a character’s point of view.

In contrast to these examples, what we might call post facto point-of-view sequences only reveal that they are from a particular character’s exact perspective after the onset of the sequence itself. Here, we suggest, is an example. In A Portrait of a Lady on Fire, we see Héloïse through flames. She then slowly walks a short distance before pausing, gazing squarely in what seems to be the direction of the viewer. We then notice that a bit of her dress is on fire, which she doesn’t seem to notice. It gradually dawns on us, with increasing confidence as the sequence proceeds, that the vantage point from which we see Héloïse is Marianne’s perspective and has been all along; this is why the gaze is so fixed, so unmoving from Héloïse, even after her dress catches fire, and why Héloïse’s gaze returns so unwaveringly. It is the gaze of someone transfixed by Héloïse as an object of desire and who has in turn transfixed Héloïse.

This sequence is, we maintain, a post facto point-of-view sequence. The perspective it embodies is all along Marianne’s, but it only becomes clear to us that this perspective is Marianne’s exact perspective—and not merely a visual scene from a vantage point at approximately Marianne’s location—when we realize that the visual scene is explained by the gaze of someone transfixed by Héloïse, so much so that the possessor of this gaze is unable but to continue staring at Héloïse’s face, even when Héloïse’s skirt catches fire. (Compare: at the very beginning of the sequence, a brief shot shows Héloïse at a much closer distance than the shots later in the sequence. It seems unlikely that this close-up shot discloses Marianne’s exact perspective, as it is not from her vantage point, in which case it would not be a true point-of-view shot.)

Consider the classical view, on which all representations of subjectivity in film are necessarily indexed to you, the viewer of the film. How might the classical view explain how a viewer might initially experience a visual perspective as not necessarily belonging to any character but then ultimately conclude that perspective belongs to some character? We will argue that on the classical view, this prosaic phenomenon requires a rather surprising explanation, one that posits that the viewer must make certain inferences about the nature of the film experience itself in order to reach the conclusion that the perspective presented is (say) Marianne’s. Put otherwise, our rival view must appeal to meta-cinematic inferences to explain the viewer’s experience of post facto point-of-view shots. In contrast, on our preferred, unindexed subjectivity view, the viewer’s experience of these sequences can be explained without attributing to the viewer meta-cinematic inferences. Rather, the viewer can reach this conclusion merely via ‘first-order’ inferences about the events in the film itself. As we will argue, meta-cinematic inferences typically have different aesthetic effects than those achieved by sequences such as the ‘Héloïse’ sequence, so we take our explanation to outperform the classical view.

To be clear, we think films can and often do mandate that their viewers engage in inferences about the nature of film experience. We also think films can mandate highly sophisticated patterns of reasoning in viewers. So, our qualm with the rival view will not be that it posits that in some cases, viewers make sophisticated inferences about the nature of the film experience. Rather, we will argue that it is odd that such meta-cinematic inferences should come into play when it comes to this kind of sequence, when this sequence seems to have the effect of drawing one further into the world of the film and into the minds of its characters, not to push one outside of the world, into reflections about the film or about oneself. Thus, our objection is not that the rival view is ‘too cognitive,’ in that it requires viewers to engage in reasoning that is too sophisticated to be psychologically plausible; rather, it is that our rival view attributes the wrong kinds of inferences to the viewers to explain this particular type of experience, whose total effect is the viewer’s greater absorption into the world of the film.

We will first explain how our preferred, unindexed subjectivity view can explain the sequence without appealing to inferences about the film itself. And then we will argue that our rival, the classical view, cannot do this, before suggesting why this difference constitutes some reason to prefer our view to the classical view.

On our preferred unindexed subjectivity view, the ‘Héloïse’ sequence and similar sequences are explained this way: in the early stages of the sequence, the viewer represents Héloïse through a fire. This representation is not taken to be the viewer’s, even though it is first-personally represented. Nor is the representation taken to be Marianne’s, at least not initially. As the shot unfolds and as it becomes increasingly clear that this shot depicts the gaze of someone transfixed by Héloïse, the viewer comes to understand that the shot portrays Marianne’s exact perspective, not merely a perspective of Héloïse from some vantage point near Marianne. So, the viewer understands early on that the perspective represents a subjective vantage point, but it is left open whether it is hers (the viewer’s), Marianne’s, one of the other women’s present at the bonfire, or an unowned perspective. Later, the viewer ‘fills in’ the unfilled variable; the subjective experience is Marianne’s, who is transfixed by Héloïse, which explains why the perspective is unchanging even as Marianne’s dress catches fire.

In other words, the unindexed subjectivity view attributes to the viewer the following abductive inference:

There is a first-personal experience as of Héloïse through bonfire light, meeting someone’s gaze and seemingly transfixed.

Marianne is opposite Héloïse.

On the best explanation, the experience is Marianne’s.

The experience is Marianne’s.

To say that the unindexed subjectivity view attributes this inference pattern to the viewer is not, of course, to say that this view posits that the viewer consciously engages in this inference. This inference might be entirely non-conscious; or its premises might be non-conscious and its conclusion conscious. The view merely posits that this inference or something very close to it explains the viewer’s (justified) conclusion about the owner of the perspective at hand. Notice that this inference pattern is ‘first-order,’ in that the viewer can reach it without appealing to premises about the nature of film experience, merely by appealing to facts about the world of the film itself. Consider: The first premise is about an experience. In particular, it is about a literal perspective of a character, one that obtains in the world of the film (importantly, it is not about a depiction of a perspective). The second premise is about a character’s location in that world. The third premise is about a relation between that experience and a character.

One might object to this ‘first-order’ characterization of the inference pattern by claiming that (3) reflects a meta-cinematic inference. For, presumably, the grounds for (3) are that in films, point-of-view shots are often signaled by visual and auditory information encoded in a certain way, which, when supplied with narrative information about the locations of various characters, can suggest to the viewer that some shot is a point-of-view shot. Thus, (3) draws on knowledge of cinema as an art form.

For some viewers, background knowledge of the cinematic form might in fact play a role in their production of (3). But, our point is that viewers can reach (3) without appealing to any presumptions about the nature of the film itself. Thus, we deny that the epistemic reasons for (3) essentially involve meta-cinematic presumptions. For, consider: Outside of the context of film, if one were to describe some perspective without indicating whose it was but were to supply additional information about the locational information of a certain perceiver, you might well conclude that the perspective was owned by that perceiver. Thus, this form of inference can be made on the basis of this kind of information without appealing to traits of cinema.

What of the ‘best explanation’ appealed to in (3)? Is that itself a meta-cinematic explanation, one that obtains ‘outside’ of the film, not in it? We can and should resist that suggestion; explanations can obtain between facts in fictional worlds, no less than facts in the actual world. The fact that Sherlock Holmes is a detective can help explain the fact that he received pay to investigate a certain curious incident of the dog in the night time. This explanation is not meta-narrative; it obtains within the narrative itself, about elements in the fictional world itself. So too, we maintain, do facts about Marianne and facts about her perspective hold within the fiction itself, even though those facts are, of course, rendered and made visible for us in a film work.

Notice that this rather simple explanation of the viewer’s reasoning in post facto point-of-view sequences is not available on the classical view, on which subjective representations are invariably represented as the viewer’s. For, recall that on this view, films invariably mandate that the viewer imagines herself to have some imagined perceptual experience. So, on this view, the viewer imagines that she herself perceives Héloïse through a bonfire. Then, as the sequence progresses, and as it becomes increasingly clear that this sequence depicts the gaze of someone transfixed by Héloïse, the viewer comes to understand that she is seeing Héloïse from Marianne’s exact vantage point, not merely Héloïse from a vantage point near Marianne. The viewer then infers that the perceptual experience she is having is qualitatively identical to Marianne’s. And in this way, she learns something significant about Marianne’s experience. Here, then, is the abductive inference the classical view will attribute to the viewer of this sequence:

I (myself) have a first-personal experience as of Héloïse through bonfire light, meeting someone’s gaze and seemingly transfixed.

Marianne is opposite Héloïse.

The best explanation of (1) and (2) is that my experience is qualitatively identical to Marianne’s.

My experience is qualitatively identical to Marianne’s.

Marianne has a first-personal experience as of Héloïse through bonfire light, meeting someone’s gaze and seemingly transfixed.

Notice that this inference pattern, unlike the previous one, appeals to meta-cinematic premises. In particular, both (1) and (3) appeal to the viewer herself, to her first-personal representation of Héloïse. So, the premises of this argument are at least partly about elements outside of the world of the film, namely about the viewer herself.

What is wrong with the fact that the classical view attributes a meta-cinematic inference to the viewer to explain her understanding of the ‘bonfire’ sequence? To reiterate, our complaint is not that the inference is ‘too cognitive’ nor merely that it is meta-cinematic; it is that the view attributes a meta-cinematic inference to a viewer to explain an inference whose main effect, it would seem, is to draw the viewer further into the world of the fiction. When we learn via the ‘bonfire’ sequence that Marianne is infatuated with Héloïse, we are pulled into the psychology of Marianne and into the drama between the two women. We learn something intimate about Marianne. We are perhaps excited for her, or scared. We perhaps emotionally resonate with her and begin to see Héloïse a bit more as she does, as elevated and simultaneously as an object of desire. The overall effect of the sequence does not seem to be to pull us out of the world of the film, to remind us that we are consumers of art; if anything, the sequence would seem to only further paper over this fact, inasmuch as it succeeds at making us care about and empathize with the growing attraction between the two women.

As further, defeasible evidence that the ‘bonfire’ case doesn’t involve a meta-cinematic inference, we present other cases in which viewers are overtly asked to draw a meta-cinematic inference, and we note that these cases seem to have a very different overall effect than the ‘bonfire’ sequence. Consider, for instance, the film Waltz with Bashir (2008), which is animated for the entire film except the last few minutes. It tells the story of a veteran struggling to remember his involvement in the Lebanese civil war. These animated sequences invite the viewer to represent that the animated world is real, in some sense. The last minutes of the movie are documentary footage of the aftermath of a massacre of refugees in the Sabra and Shatila camps. This switch from animation to documentary is extremely jarring. There are likely several reasons this is so, one of which is the graphic and disturbing content. Another one is that the dramatic and unexpected switch undermines the previous cooperation between the film and the viewer, wherein the viewer ‘agreed’ to treat the animated world as real, in some sense. But a final, and we suspect, significant, reason is that the switch draws the viewer’s attention helplessly to the very nature of the film experience itself, to the format of the film, whereas ‘typical’ film experience permits absorption in the world with little care for its format. Of course, this is just one case, and a complex one, but we take this to be at least some evidence that meta-cinematic inferences tend to pull the viewer out of the world of the film, psychologically speaking, not to thrust her further into it.

Cases in which characters ‘break the fourth wall,’ or speak directly to audience members are also examples of films which mandate that their viewers engage in meta-cinematic reasoning. Classic examples include Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (1986) and Amélie (2001), both of which see their respective protagonists explaining themselves to the audience. While breaking the fourth wall can have wildly different effects in different contexts, this technique is often at least slightly jarring to audience members. Depending on the broader narrative and aesthetic context, that sense of surprise can have different further aesthetic consequences. In the cases mentioned, the effect adds to the whimsy of the films; the effect is received as a kind of winking or joke, a reminder that we are making believe but in doing so, we agree to continue going along with the gag. The effect is to facilitate our playful cooperation.

Notice that, while breaking the fourth wall can have different effects, in none of the cases considered does it have the effect of making the audience member feel further absorbed into the world of the film, forgetful of herself and her own world. Rather unsurprisingly, to draw the viewer’s attention to the fact that she is watching a film would seem to tend to disrupt or distort her ability to engage in that film in a fully immersive way. Our total suggestion, then, is that sequences which require viewers to reflect on the fact that they are watching a film will tend to be ones which draw the viewer out of the narrative, at least momentarily. They do not tend to facilitate the narrator’s greater absorption into the world of the film. We do not take this pattern to constitute a universal rule, and, given the highly variable nature of film, we think it extremely likely that the pattern will have notable exceptions. But we think that the existence of this pattern constitutes at least some defeasible evidence in favor of our unindexed subjectivity explanation of post hoc point-of-view shots.

We conclude, then, that it is at least some reason to prefer the unindexed subjectivity view over the classical view that the unindexed subjectivity view can explain the viewer’s experience of sequences like the Portrait of a Lady on Fire sequence without attributing to the viewer a meta-cinematic inference pattern.

3. Cinematic Experience in Its Cognitive Context

So far, we’ve motivated a kind of thoroughgoing pluralism about representations in film experience, on which the perspective spot in cinema is sometimes experienced as unoccupied, sometimes experienced as occupied, and sometimes experienced as part of a richly embodied subjective experience, one which in turn is sometimes indexed to the viewer or a character but sometimes indexed to no one at all.16

We’d like to close by drawing out some consequences of the ‘unindexed subjectivity’ view. First, it provides a set of tools to talk about divergent centers of perspectives, cases where for instance the perspective spots for auditory and visual information are located at different places. Second, it places film experience on a continuum with other forms of imagination and mind-reading.

Subjectivity, including unindexed subjectivity, in film not only signals a subjective observer, but locates that observer in space (i.e., at the perspective spot). Our examples have primarily been visual, but of course, film also uses sound to mandate experiences, and the experience of film involves an even broader spectrum of sensory imagination, including proprioceptive, tactile, and olfactory cues. And beyond standard forms of sensory imagination, film experience may also sometimes include experiences of embodiment and vivid emotional representations ‘from the inside’ such as certain forms of empathy. All of these forms of experience can be thought of as centered at a location. But what happens when the locations fail to coincide?

In many cases, sound design in film is consistent with a single multi-modal perspective spot, but only rarely is an entire film fully consistent in this way. Common transitions, such as the J-cut, in which audio from the next scene begins before the visual transition, involve momentary divergence between the auditory and visual perspective spots. As another example, in this sequence from Once Upon a Time in Anatolia (Bir Zamanlar Anadolu’da), we hear the audio from inside the car for over a minute as we see the car from far away. In the second sequence, as the conversation continues, the audio and visual perspective spots are now consistent, both inside the car:

We can observe a similar divergence in affective centering. As Currie (1995: 176) notes, film sequences implying the perspective of a person in pursuit of a victim often trigger, somewhat paradoxically, an emotional identification with the victim rather than one that is consistent with the center indicated by the visual perspective.

But is this form of affective identification a merely metaphorical sense of centering? It seems to depend on what we mean by affective identification. We might mean that we feel sympathy, a sense of similarity, or other form of abstract commonality with the victim. In this sense, centering on a spatial location is a mere metaphor, since we imply a relationship between us and their personality, trajectory and so on—features that, strictly speaking, are not spatially localized. But in embodied identification, we feel a sense of centering in a location that is far more literal: for instance, we might feel the urge to duck when the victim nearly hits his head on an overpass or grab our arm when his arm is stuck. These actions imply more than an abstract identification, an identification with a particular physical location in the world of the film.

Does each sense modality convey its own sense of subjectivity? Or, put another way, is there a one-to-one correlation between subjective perspectives and spatial centers of experience? The emphasis on structure in the unindexed subjectivity view is the key to answering this question. One form of structure in experience that encodes subjectivity is at the level of sensory modality, and a second form is at the multi-modal or integrative level. In the type of pursuit scene sketched above, this seems to exhaust the form of subjectivity at play: a visual identification with the chaser, and an embodied one with the victim.

But the Once Upon a Time in Anatolia sequence is different. We are still presented with two forms of unindexed subjectivity (provided the far-away view is really signaling subjectivity at all, which seems somewhat controversial). But this sequence triggers a feeling of alienation, as if we’re the silent prisoner in the middle of the back seat of the car, dislocated and lost in the landscape, rather than included in the conversation. That is, the experience created by the juxtaposition of the two representations of unindexed subjectivity is itself a subjective representation, evoking a distinctive feeling of being unmoored, which (arguably) is indexed to the prisoner.

This mirrors the explanation our account gives of the visual perspective case. In some sequences, the film mandates a subjective experience, in others it doesn’t, and these switches are signaled in a fairly subtle structural way. Subjective perspective can be mandated through different modalities, and at times these modalities suggest different perspective spots. But because of the hierarchical nature of subjective experience, as we’ve just suggested, these multiple spots may themselves be signaled as constituents of an integrative subjective experience, as in Once Upon a Time in Anatolia, or not, as in the chase sequence or the J-cut. In the latter kinds of scene, there is no mandated subjective experience at the integrative level, just as in the ordinary non-perspective shots, there is no mandated subjective visual experience. We think this extension of the view shows its explanatory strength, but also opens interesting questions about how the integrative form of subjectivity works, when it is triggered, and how it contributes to the distinctive aesthetic of film.

On our account, what is held in common between film experience and other forms of cognition? The possibility of subjective representational structures with no subject might seem odd or incoherent. This oddness may be seen as evidence in a broader debate about impossibility and imagination. Where normal experience has to be all “filled in,” imagination is (arguably) often gappy and unresolved in ways that no outer experience could possibly have been. For example, in Borges’s Dreamtigers, the narrator describes imagining a flock of birds, without imagining any particular number of birds. We can imagine a person without imagining exactly what clothes they are wearing, or a boat without a sense of how large it is. Thus, imagined scenes are often lacking in detail in a way that no real scene could possibly be lacking; whenever I see a flock of birds, I do so in virtue of seeing a flock of a certain number (even if I don’t know how many there are). Along similar lines, Sorensen (2002) entertains the idea that a picture of nothing may be the best example of an impossible depiction. So, contextualizing the unindexed subjectivity view of cinematic experience as a kind of imagination explains away the mystery of the unfilled-in variable: it’s a more general feature of imagination to be informationally gappy, a feature that may even be linked to the distinctive role of imagination in learning. This incompleteness may fall short of impossibility but (potentially) still represent a way in which perceptual imagination fails to abide by principles of perception.

The unindexed subjectivity view also forges a connection to the mindreading literature. De Vignemont proposes that unindexed subjective experiences might sometimes explain our rapid inferences about the mental states of others. One question about mindreading is that of its connection with self-knowledge. The putative existence of widespread ‘mirroring’ mechanisms, whereby, for instance, motor neurons for action are activated when viewing others performing actions, along with familiar observations that empathy seems to contribute to knowledge of others, has led many theorists to posit a deep connection between self-knowledge and knowledge of others, though it is highly contested what this relation amounts to.17

On one view, we tend to make attributions of others’ mental states first by simulating some of their relevant actions, thereby coming to know what mental state would explain our actions. We then infer that others who engage in such actions have the mental state in question. This is, in some sense, a ‘self first’ view of knowledge of others’ mental states. On another view, we tend to come to know our own mental states by employing a general theory of behavior—one possibly gained by observing others—and by applying that theory to ourselves. This is, in some sense, an ‘others first’ view of oneself. De Vignemont proposes a path to knowledge of others and oneself that is, in at least some cases, one and the same. This is the unindexed subjectivity model on which we at least sometimes represent certain actions first-personally but without representing whether it is ourself or others who are doing them and then, employing context clues, draw an inference about whose action it is. If this view is right, the connection between knowledge of self and others is far deeper than going views have assumed; both start in the exact same place, with ‘neutral’ knowledge of a subjective representation.

While we do not wish to endorse the unindexed subjectivity view of self/other knowledge, we take it to be some reason in favor of our view that it places film experience on a continuum with models of cognition to explain other aspects of experience, such as mindreading. Moreover, if unindexed subjectivity figures, even very occasionally, in self/other understanding, the connection between film experience and experience of the social world is far more intertwined than we might previously have realized; to watch a film is to exploit capacities developed to understand both others and ourselves.

4. Conclusion

In this paper, we’ve considered a classic question in philosophy of film: Who, if anyone, occupies the perspective spot, the location in the world of the movie from which the action is portrayed? First, we’ve argued for a kind of pluralism, on which this question has a false presupposition. There is no ‘typical.’ Sometimes no one is represented in this spot, and sometimes this spot helps to anchor a subjective representation.

We have further suggested that in at least some cases, the perspective spot helps anchor a subjective representation which is ‘unindexed,’ in the sense that it is not indexed to the viewer but is rather indexed to no one at all. In other cases, this experience is indexed to you (the viewer), and in others to a particular character. This is possible because of the structural device of an unindexed subjectivity: a way of presenting an experience as subjective via its structure that does not require a specified occupier of the subject position.

The unindexed subjectivity view has some crucial advantages: it explains perspective divergence, cases where content and structure suggest differing answers to the question of who, if anyone, is present in the perspective spot. It explains post facto point-of-view shots, cases where we only learn who is perceiving the scene later on. It also allows us to explain the hierarchical structure of subjective experiences that emerges in cases where multiple sensory and embodied modes pick out subjective viewpoints at distinct spatial locations.

We’ve suggested that among the many possible types of perspective that can be engaged by films is a perspective that is truly subjective while lacking a subject. This might at first sound nonsensical. But consider the wide variety of tools film has to create an impression, synchronically and diachronically, through different modalities, and through conventions, features of perception, and aspects of experience and convention. It would have been surprising if these tools always had to work in unison to create a univocal and unchanging perspective. All we need to make sense of unindexed subjectivity, then, is already in place when we see that the means of conveying that a sequence is an experience of a person rather than a mere recording from a position, and the means of conveying who if anyone that person might be, need not be the same from context to context. The viewer of a film may stitch everything together into a perfectly complete miniature world, but sometimes she will leave things open, unfinished, or in conflict, allowing for many of the complexities of this art form to unfold.

Notes

- Both authors contributed equally. ⮭

- Cumming et al. (2017) call this the viewpoint, and they propose explanations of certain conventions governing spatial relations between viewpoints. However, we want to allow for non-visual forms of perspective to signal a perspective spot: for instance, a film might use sound cues to locate the perspective spot near the engine of a car. See also Gaut on a film’s ‘intrinsic perspective’ (2010: 39). For a spatial explanation of how point-of-view and similar shots signal what a character sees, see Cumming et al. (2021). ⮭

- Why think typical experience and mandated experience come apart? Consider an extremely boring film, one so complex and unengaging in its content that it tends to cause viewers to ignore the film altogether, retreating, perhaps into whatever daydream can most distract them. The kinds of experiences made apt by or mandated by the film are about the deeply complex plot, but the kinds of experiences audiences happen to have might be rather banal or pleasant ones, about certain fantasies of theirs. But, of course, the latter are not the kinds of experiences mandated by the film, even if they are systematically caused by the film. ⮭

- Our inspiration for the view of unindexed subjectivity is de Vignemont (2004) who calls these shared representations. See also de Vignemont and Fourneret (2004) and de Vignemont (2010; 2014). We prefer a different locution to make clear that these representations needn’t be simultaneously occupied by multiple individuals; indeed, on our view, these representations needn’t be occupied at all. ⮭

- Our method is thus very similar to Murray Smith’s (2022a; 2022b), in that we aim to understand film experience from a cognitive science, phenomenological, and aesthetic perspective. ⮭

- Likewise, L.A. Paul suggests that in video games, perspectives can switch from a first-person perspective to something ‘analogous to an objective perspective’ (Paul 2017: 13). ⮭

- Following Wollheim (1984), Smith (2022a) often calls these acentral and central forms of imagining, respectively. ⮭

- Smith (2022a) is in some ways inspired by Wollheim (1984), who also espouses a kind of pluralism. ⮭

- Here we break from McCarroll (2018) who (in the context of memory rather than film) divides memorial experiences by different centerings. He holds that there is no genuine allocentric memory experience, but our observer-perspective memories typically involve an “unoccupied point of view.” McCarroll is a pluralist with respect to these centerings: for instance, I might have an experience that is visually centered at one location and affectively centered at a different location. But for him, location and subjective modality go together, whereas we hold that in film, the perspective spot is sometimes the locus of a first-personal, subjective presentation and at other times the locus of an impersonal presentation. Further, one of the authors (SA), unlike McCarroll, holds that multiple subjective centerings are always in a sense incoherent. ⮭

- It does seem plausible that some kind of spatial centering might be a necessary component of subjectivity; for instance, even thinking about someone’s emotions from the inside might invoke a spatial reference point in interoceptive space. But surely a visual perspective is unnecessary, since other modalities, such as the auditory sense, can anchor a perspective. ⮭

- See Cumming et al. (2017) for a discussion of these kinds of parallels between film and language. A relevant concept they employ is that of a semantic convention, which might also ground an alternative to the structure/content distinction we put forward. On their notion, whether a feature is semantic depends on whether it is conventional, whereas features of a film can be structural without being conventional (e.g., a connection between score and mood that takes advantage of psychological tendencies or rational inference rather than rule-like conventions). However, the cues used to signify first-personal experience may not be conventional so much as isomorphic to critical features of experience. See Gaut (2010: e.g., 56) for a criticism of the view that film experience is language-like. ⮭

- Thanks to an anonymous referee for this suggestion. ⮭

- Moreover, since the fact of whose subjective experience is represented plausibly comes in degrees, it is not implausible that it might come in ‘degree zero,’ as when a subjective experience is attached to no one. We thank an anonymous referee for making this point. ⮭

- See, e.g., Sorensen (2002) and Gregory (2020) for discussions of whether images or imagery can represent the impossible. ⮭

- Of course, the film Dear Diary as a whole is somewhat avant garde (and very meta-cinematic), but we’d maintain that this sequence is quite mundane. ⮭

- Thus, our view is distinct from Lopes’s (1998) view that film experience mandates an impersonal centered perspective. Lopes’s view primarily concerns the presence of a vantage point or a center, not the integration of sensory cues of the kind which signal the presence of a typical human body or emotionally relevant cues. A closer view to ours is that developed by Enrico Terrone, on which the kind of experience mandated by film is that of a disembodied subject. In particular, Terrone’s view is that “the spectator of a fiction film imagines being a subject of a different kind, namely, a disembodied subject of experience who can perceive events that occur in a world in which that subject has no place” (Terrone 2020). We lack the space to assess the many rich and compelling points Terrone adduces in favor of his view. Instead, we will merely point to three significant differences between his view and our own. First, while we think film experience sometimes mandates subjective representations, we also think that in some cases, film experience mandates impersonal representations. In contrast, Terrone’s view is that film experience invariably mandates disembodied representations. Second, focusing just on those cases in which film experiences mandate subjective representations, we think these representations are at least sometimes experienced as embodied, mirroring, as they often do, the integration of visual, auditory, proprioceptive, emotional, and other cues in a normally embodied human being. Terrone, in contrast, maintains that subjective representations in film experience are as of a disembodied being, a ‘pure potential for experiences.’ Third, Terrone thinks subjective representations are invariably indexed to you, the viewer of the experience. In this much, Terrone’s view is a variant of what we have been calling the classical view, on which subjective representations mandated by film are indexed to you, the viewer of the film. We thus take this aspect of the view to be targeted by our arguments for the unindexed subjectivity view. ⮭

- See, e.g., de Vignemont (2004; 2010; 2014) and de Vignemont and Fourneret (2004). ⮭

Acknowledgments

For extremely helpful comments on this paper, we are indebted to: Josh Armstrong, Liz Camp, Gabe Greenberg, Chris McCarroll, Alexander Nehamas, Dustin Stokes, and participants of the Workshop on Cognitive Science, Aesthetics, and the Imagined World. Special thanks to two anonymous referees and an anonymous area editor.

References

Anderson, W. (Director) (1996). Bottle Rocket [Motion picture].

Bilge Ceylan, N. (Director) (2011). Bir Zamanlar Anadolu’da [Motion picture].

Brody, R. (2015, February 3). Movie of the Week: Caro Diario. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/richard-brody/movie-week-caro-diario

Calvino, I. (2010). Our Ancestors. Random House.