Online Platforms and Circulation Patterns for Films

Online video-on-demand (VOD) platforms are reshaping the ways that films circulate in national and international markets, how they are introduced and promoted to audiences in those markets, and how audiences engage with them. Netflix, Amazon, MUBI, and many other VOD platforms are part of an online market with far-reaching implications for the breadth of films that audiences can watch. The online market, as well as the process of online distribution, is often talked about positively as having an enriching impact on the availability of films. The assumption is that it provides access for a wider and more diverse range of films than the DVD/Blu-ray market and the television market, and even more so the theatrical cinema market. That assumption is in various ways entrenched in some of the liberal principles that are associated with how the online market has proliferated itself in order to flourish, building on notions of limitless content abundance and audience access to films.

The prevalence of such notions of abundance and access in the online market calls for an analysis of the circulation of films, and the role of VOD platforms in making those films available, visible, and discoverable. VOD platforms operate as powerful gatekeepers with programming practices that are based on the processes of selection and prioritization.2 Their decisions determine how films are presented on platform interfaces through strategic content placement and content recommendation, and therefore navigate audiences to some films in their catalogs, which are given more prominence than others. It is through such interventions that they are able to exert influence over patterns of audience consumption.

The development of the online VOD market and its broader impact on culture and society are increasingly widely discussed within the disciplines of Media Industry Studies and Film Studies. Discussions are developing in directions such as policies and regulation, cultural diversity and distribution, gatekeepers and digital disruption, and business models for VOD platforms.3 There is also emerging research on the circulation of audiovisual works and the way they are introduced and promoted on VOD platforms. Such studies revolve around business strategies, cross-border circulation, platform interfaces, and audience recommendations through human curators and algorithm technology.4 The circulation of audiovisual works in such contributions is often associated with processes of power and control, particularly in relation to the perspective of a winner-takes-all economy.5

David Hesmondhalgh and Amanda Lotz employ the concept of circulation power to demonstrate how media industry companies can manipulate processes of circulation in the online market.6 VOD platforms exert control over the process of enabling and disabling access to films, television series, and other content, while they also exert control over the process of making that content visible. They operate as gatekeepers whose influence on processes of availability and visibility can in some cases be enriching but in other cases restricting, and certainly have an impact on the ways that different types of audio-visual works reach audiences. By filtering out audiovisual works through industrial structures of distribution and exhibition, they render some works more available and visible than others, and unavoidably create imbalances.

While academic works on the processes of online circulation have increased in recent years, there is still much to learn empirically about the dynamics behind that process. Given the continuing development of the online market, it is important to ask if well-established analytical frameworks about online circulation need to be reconsidered. The analytical discourse about the binary logics of scarcity and abundance has remained dominant, even though business models for VOD platforms have developed, diversified, and expanded, and the market for VOD platforms has become increasingly fragmented. One important development is that the size of several VOD platform catalogs has changed. Netflix, for instance, has gradually reduced the size of its film catalog in at least some countries since their transition to a subscription service, while the number of television series in their catalog increased. One report, which draws on information collected by data aggregator Flixable, notes that the Netflix film catalog in the US market decreased from 6,755 films in 2010 to 4,010 films in 2018, a difference of 41 percent over a period of eight years.7 Another report, which draws on information collected by data aggregators ReelGood and JustWatch, notes that the Netflix film catalog in the US market decreased from 6,494 films in 2014, to 4,335 films in 2016, and to 3,849 films in 2019. That again is a difference of 41 percent over a period of more than five years.8 If Netflix has often been talked about as providing a huge abundance of film titles, these developments question such descriptions.

While some platforms have decreased the size of their catalog, other platforms have increased the size of their catalog. MUBI is a well-known example of a subscription VOD (SVOD) platform that initially operated according to the logic of exclusivity and scarcity, with a rotating offer of only thirty films available at any one time. However, it changed its model in May 2020 to add a permanent collection of hundreds of classic and archive films alongside their rotating offer of thirty films.

The examples of Netflix and MUBI demonstrate that a simple opposition between scarcity and abundance hardly does justice to the complexities of the online film market. Rather, they are illustrative of the way that several VOD platforms have introduced business models with other approaches to film availability, content selections, and audience engagement in the past ten years or so. This paper analyzes the shape and structure that circulation patterns have taken in the online film market in Germany. The term circulation patterns can be broadly employed to describe how processes of access and cultural flow take shape, particularly with regard to distribution and exhibition. Based on an analysis of online availability in the film exhibition sector, I argue that new business models adopted by VOD platforms have reshaped circulation patterns. The effect is that those platforms have redefined the way that on-demand culture is experienced by audiences, in terms of their expectations about access to films. In addition, I argue that it has become increasingly challenging to think about online availability through a crude binary opposition to scarcity and abundance. The reality is more complex and nuanced because the online market for VOD platforms has become increasingly fragmented.

Researching Online Availability and Circulation Patterns

The effect of various business models and approaches to film availability is that it is unclear to what extent VOD platforms engage with different types of films and which circulation patterns have developed. If online distribution has increased availability, we need to know where films are available in order to understand the implications of that availability: in terms of the width and stretch of film circulation, their accessibility on both transactional VOD (TVOD) and subscription VOD (SVOD) platforms, their inclusion in larger catalogs as well as smaller catalogs, and therefore their ability to reach different types of audiences. A better understanding of such issues would allow us to analyze what online availability for films means in practice and to unpack the notion of content abundance.

The empirical examination of online availability that I develop in the following elaborates in various ways on other studies undertaken by academics and industry analysts. Nicolas Suzor et al. have analyzed the online availability of films, television series, music, and games in the US and Australian markets, for instance.9 Ramon Lobato and Alexa Scarlata have analyzed the availability (and discoverability) of Australian films and other audiovisual content on three VOD platforms in Australia.10 And the European Audiovisual Observatory has produced several reports about the availability of European films in European countries and non-European countries.11 While such studies are particularly useful for understanding the availability of films on individual platforms, they are less attentive to wider circulation patterns. The objective of this study of VOD platforms in Germany is to draw connections between online availability and circulation patterns. To understand circulation patterns is to analyze how widely films are available across a large and diverse range of VOD platforms.

Empirical research about online availability and circulation patterns is often based on quantitative data collection, but there are methodological challenges. First, quantitative data collection is a time-consuming process because VOD platforms are not usually forthcoming in sharing their database. Data aggregators such as JustWatch or Lumiere VOD are useful to some extent, but require further testing to ensure reliability. Second, film availability in the online market is often subject to change, with new films appearing and others disappearing, just as in the theatrical cinema market. Some quantitative studies provide what Lobato and Scarlata call “a static snapshot of an evolving infrastructure,” while others develop a time-consuming tracking study to measure availability over a specific period of time.12 Third, the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic has encouraged distributors to experiment with direct-to-VOD strategies, with some films becoming available in the online market before the theatrical cinema market, and others exclusively online. Given such methodological challenges, a case study approach is particularly useful to make research manageable and undertake in-depth analysis.

Research Focus

The research focus in this paper is firmly on the availability of what are sometimes called specialized films on VOD platforms, drawing on empirically rich data about such availability in the German VOD market. The concept of specialized films is employed to refer to a category of less familiar feature films that circulate mostly beyond the mainstream, including independent films, art-house films, festival films, and world cinema. Specialized films are commercial productions that are often associated with an appreciation of their cultural, aesthetic, and/or social values, and their enriching contribution to the diversification of film culture. As such, they are roughly located between mainstream, commercial films, and experimental, non-commercial films. The concept of specialized films is primarily used within industry discourse, in the trade press and by film practitioners, and film agencies and funding bodies, particularly in the UK and US markets. The term also appears in academic scholarship about the film industry. Several academics, for instance, employ definitions of specialized films that were introduced by the UK Film Council and the British Film Institute.13

In terms of the circulation of specialized films, they are often submitted to film festivals in national and international markets to secure festival screenings, build up a profile, and generate awareness among audiences and critics. Such screenings through the film festival circuit support the formal distribution process, whereby distributors develop a commercial release strategy for other markets in the film exhibition sector, such as the theatrical cinema market, online market, DVD/Blu-ray market, and the television market. In national markets such as Germany and the United Kingdom, specialized films are usually first released in cinemas, but only few such films are able to break out of the specialized market and cross over into the mainstream market. Examples of such films are Green Book (2018) and Parasite (2019). Most specialized films (i.e., in their hundreds every year) are typically given a modest release on a relatively low number of cinema screens by distributors in Germany and the United Kingdom. Of course, there are differences in terms of the theatrical cinema release for specialized films across national markets or territories, but it is often argued that screen time and space are mainly allocated to mainstream films.14 Given such challenging circumstances for specialized films in the theatrical cinema market, this study sets out to analyze how widely they circulate in the online market.

Online availability and circulation patterns are analyzed from the perspective of VOD platforms that operate in Germany. According to the revenue estimates for 2020 by data aggregator Statista, Germany was the largest market for VOD platforms in Europe and the fourth largest market worldwide — behind the United States, China, and Japan.15 Statista also estimates that SVOD and TVOD platforms in Germany accounted for €1.4 billion in VOD revenues in 2020. As in most markets worldwide, Germany comprises a range of national-oriented platforms such as Maxdome, Videoload, and Realeyz, as well as global and transnational platforms such as Netflix, Amazon, MUBI, and Disney+. The combination of global and national players in the German market is important for the reliability and generalizability of this study.

The umbrella term online VOD platform is employed throughout the various sections of the paper for reasons of clarity. It is most closely related to the TVOD and SVOD platforms that are analyzed in relation to film availability. Online VOD platforms are also more broadly referred to as Internet-distributed video services, particularly in media industry studies.16

Methodological Approach

The study is informed by a self-produced database with information about a sample of 150 specialized films on nineteen VOD platforms in the German market. This allows for an empirically rich case study, whereby the value is in the scope and depth of circulation patterns.

In order to identify a meaningful sample of 150 specialized films, I focused on films supported by Creative Europe, the flagship institution for film in Europe. Creative Europe provides financial support for European films that qualify for their funding programs, but many of those films can also be described as specialized films. In particular, their “distribution selective” program is relevant because it is designed for sales agents and distributors who want to enhance the circulation of European films across European countries.17

The preparatory groundwork for the database involved firstly identifying all European films that were funded through the distribution selective program in the period between 2011 and 2018 (208 films in total). The next step involved an assessment of which of those films could reasonably be described as specialized.18 A sample of 150 specialized films was identified in this way. The distribution selective program works with specific criteria for distributors across Europe. One criterion, for instance, is that German distributors can be awarded funding only for non-German (European) films. In terms of the full sample of 150 specialized films, German distributors received distribution selective funding for 117 specialized films (78%).19 Another criterion of the distribution selective program is that German productions can be awarded only to non-German distributors. There are eleven specialized films (7%) in the sample with a lead production company from Germany.20 For the remaining twenty-two specialized films in the sample, German distributors acquired fifteen specialized films (10%) without funding from the distribution selective program, while seven films (5%) were not acquired by German distributors for a theatrical cinema or online release in the German market.21 In terms of the full sample of 150 specialized films, it is also worth noting that 27 films were made with a German (minority) co-producer involved.22

There is a wide variety of specialized films included in the analysis. Their cultural performance ranged from critically acclaimed films that won the Palme d’Or Cannes Film Festival prize, such as Amour (2012), I, Daniel Blake (2016), and The Square (2017), to other films that were able to travel and develop a profile through the festival circuit, to films that generated less awareness. In addition, their commercial performance in cinemas ranged from films that performed well in most distribution territories, to films that performed modestly in most distribution territories, to films that were not given a theatrical cinema release in most distribution territories. On the other hand, the sample of specialized films is limited because it is heavily Eurocentric, with few productions that were made in collaboration with coproduction partners from other regions of the world.

The resulting database of 150 specialized films was supplemented with information about the availability of these films across TVOD and SVOD platforms in Germany and the extent to which individual VOD platforms engage with these films. Research was conducted in July 2020, during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany. While German distributors developed direct-to-VOD release strategies for some specialized films in that period, such strategies were not developed for films included in the sample of 150 specialized films. Data about online availability was collected from Lumiere VOD and JustWatch, data aggregators that work with a large number of platforms to make information about online availability publicly accessible.23 Based on their data in July 2020, it became clear that the online availability of the 150 films in the sample was spread over 25 VOD platforms.24 The scope of VOD platforms was subsequently sharpened by applying two criteria: every platform was required to be operational during the period of research from July 2020 to February 2021, while providing access to a minimum of seven specialized films (5%) of the sample.25 A broad range of nineteen VOD platforms remained included in the analysis, of which fifteen were TVOD platforms and four were SVOD platforms. They included popular global SVOD platforms such as Netflix and Amazon Prime Video, as well as transnational VOD platforms and single-nation VOD platforms.

The subsequent sections of this paper provide insight into the availability and circulation in Germany of the sample of 150 specialized films. How widely do these films circulate on German VOD platforms? Which VOD platforms stand out in terms of providing access for those films? And what is the relationship between the availability of those films in the online market and their performance in cinemas? It is through such questions that we can begin to understand how liberal principles of access and choice have developed in the online market, and how they relate to the specificities of market fragmentation and the binary logic of abundance and scarcity. This also allows us to ask questions about circulation power, the role of gatekeepers, and licensing deals that shape and structure film circulation patterns.

Circulation Patterns: How Widely Are Specialized Films Available?

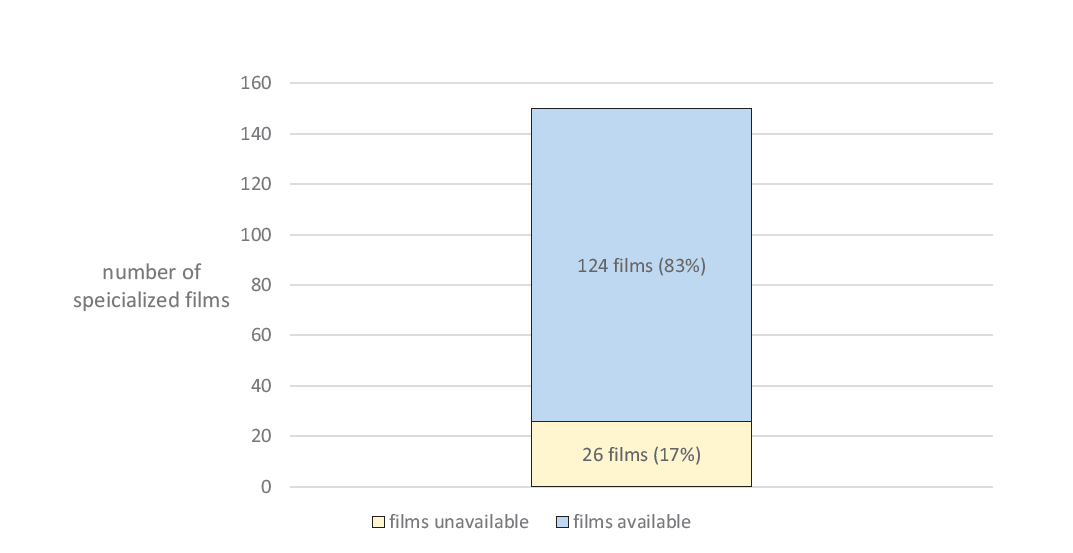

The starting point of the empirical analysis revolves around the straightforward question: how widely are specialized films available on VOD platforms in Germany? Because this analysis is based on a sample of 150 specialized films, it is not designed to make generalizations for all specialized films on VOD platforms. It is designed instead to identify circulation patterns in a period of market fragmentation. Insight is first provided about availability across nineteen VOD platforms in Germany. Figure 1 demonstrates that those platforms as a whole provide access to a relatively high number of 124 specialized films (83%) from the sample of 150 specialized films. While most such films are thus available to audiences on VOD platforms, the online market clearly does not provide unlimited access or endless choice.

Why is it not possible to access all specialized films online in Germany? Paul McDonald, Courtney Brannon Donoghue, and Timothy Havens describe media distribution as a “complex site of power, privilege, and gatekeeping.”26 It is through gatekeeper networks that decisions are made about the availability and visibility of individual films, with the release traditionally beginning in the theatrical cinema market. This process is organized through gatekeepers such as sales agents and distributors, who “filter out and narrow access through decentralized decision-making at national and international levels.”27 The online gatekeeper network is arguably more complex because various forms of online distribution have developed, including direct distribution and self-distribution. And new types of gatekeepers have appeared, with content aggregators and powerful SVOD platforms such as Netflix operating as distributors. Some films are distributed through all players in the gatekeeper network, involving sales agents, distributors, content aggregators, and VOD platforms.28 But for other films alternative arrangements may be in place, including direct relationships between producers and VOD platforms; between sales agents and VOD platforms; between distributors and VOD platforms; or between content aggregators and VOD platforms. Such different arrangements make it difficult to generalize about distribution strategies for enabling or disabling online access, and about processes of online rights management and licensing deals that impact on online availability and visibility. What these various gatekeeper arrangements and industry practices demonstrate is that online distribution is a mediated process rather than being structured through processes of open and unfiltered access; or to put it differently, processes of mediation determine the scope and stretch of circulation patterns in the online market.

It is unclear how such gatekeeper arrangements for online film availability developed in the first waves of the COVID-19 pandemic. On the one hand, online viewing became an increasingly popular activity when cinemas closed during lockdowns. That could have provided an opportunity for gatekeepers to enhance online access for their films. On the other hand, the growing popularity of online viewing does not necessarily mean that the number of films in VOD catalogues increased.

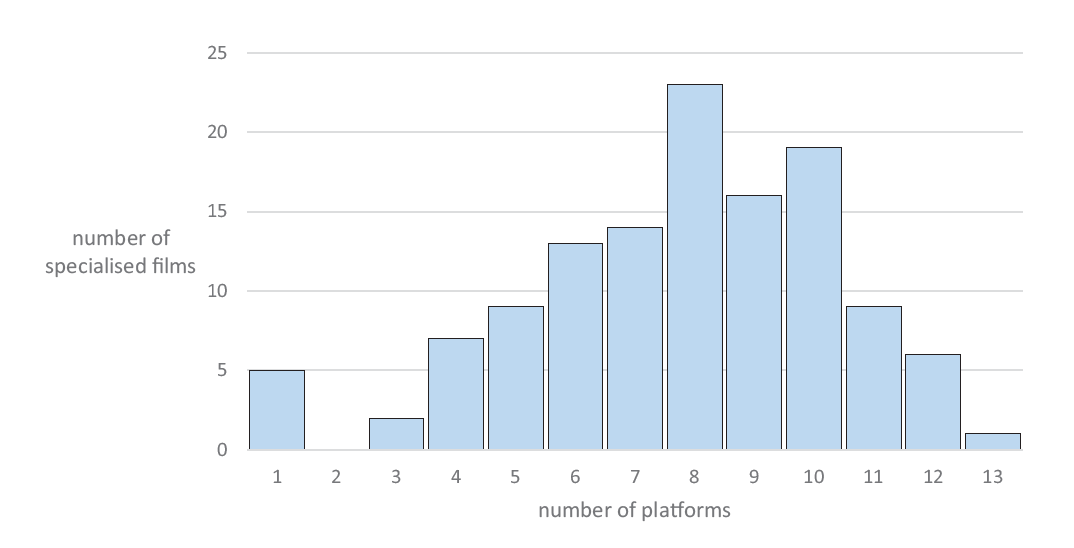

In terms of the analysis of circulation patterns, it is possible to make specific associations between specialized films and VOD platforms. Figure 2 demonstrates on how many VOD platforms such films are available in Germany. The scale of availability for each of those films varies between one and thirteen platforms. A large number of 110 specialized films (89%) are available on 5 or more platforms, demonstrating that they circulate widely and provide audiences with several online viewing options. Seventy-two of those films are available on between seven and ten platforms, while sixteen films are available on as many as eleven to thirteen platforms. On the other hand, there are a low number of fourteen specialized films (11%) that are available on between one and four platforms, and five of those films are available on only one platform.29 These various observations then provide a clear indication of the scope and stretch of circulation patterns. The analysis explores circulation patterns further in the two sections that follow. First, it identifies circulation patterns across various categories of VOD platforms. Second, it explores how circulation patterns for specialized films in the online market are associated with their commercial performance in the theatrical cinema market.

Specialized Films on Individual VOD Platforms

Online availability and circulation patterns are reliant on the particular business models, content selections, and other strategies developed by TVOD and SVOD platforms. TVOD platforms in particular offer online distribution opportunities. They generate revenues from individual online transactions, whether a one-off rental fee or purchase, which they then share on an agreed basis with rights holders. There is a great deal of variation between different types of TVOD platforms. Some of them offer access to many specialized films, while others are more selective; and some of them work with collections of specialized films that remain available for several years or even longer, while others work with collections of specialized films that rotate more often or change completely from time to time.

In terms of SVOD platforms, it is more common that they pay upfront licensing fees to acquire films. Such licensing fees usually require substantial financial investment, particularly for the most powerful SVOD platforms with relatively large catalogs. But even for such powerful SVOD platforms, the effect of upfront license fees is that their film catalogs are smaller than the largest TVOD platforms. There is also the dynamic between content rotation and long-term availability. SVOD platforms are mostly known for their emphasis on rotation, but some powerful SVOD platforms like Netflix are also investing substantial financial capital in in-house, original productions that become and remain exclusively available on their platforms.

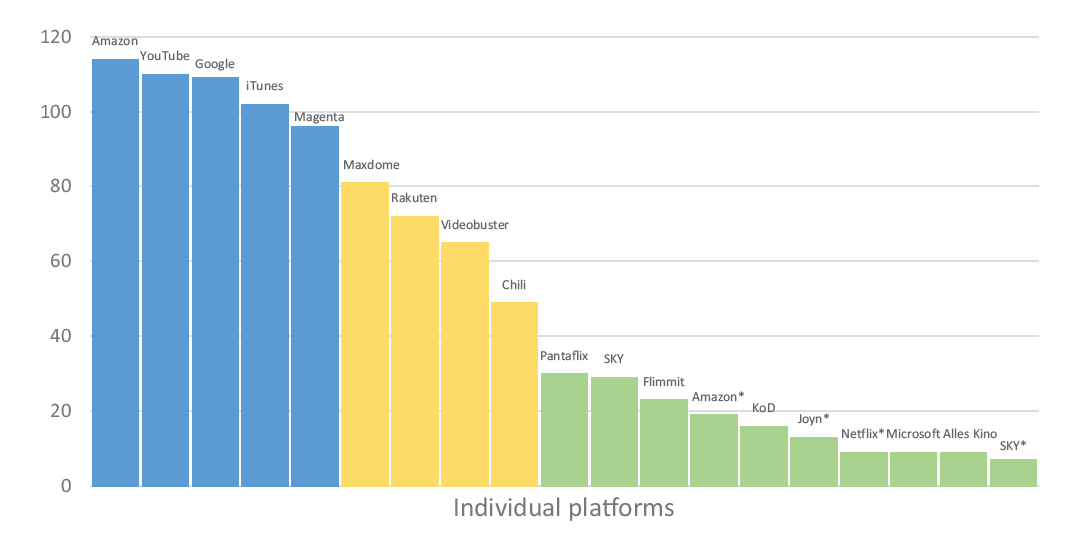

With the different licensing arrangements between TVOD and SVOD platforms in mind, Figure 3 demonstrates to what extent individual platforms in Germany engage with the sample of 124 specialized films. Three categories of platforms (appearing in blue, yellow, and green) can be identified in particular. Most specialized films are available on the following five TVOD platforms that form the first category: Amazon Prime Video (114 films), YouTube (112 films), Google Play (109 films), iTunes (102 films), and Magenta TV (96 films), with each of them appearing in blue in Figure 3. What is typical here is that Amazon, YouTube, Google, and iTunes are all companies with international operations, while Magenta TV is a powerful telecommunications company with operations in Germany and Austria.

Three categories of VOD platforms in Germany, ordered by the availability of specialized films, July 2020.

Notes: In order to distinguish between TVOD platforms and SVOD platforms, the asterisk symbol (*) is assigned to SVOD platforms. Amazon and SKY appear twice in this figure because they provide a transactional offer (Amazon and SKY) and a subscription offer (Amazon* and SKY*). KOD is an abbreviation for the platform Kino on Demand and Magenta is an abbreviation for Magenta TV.

Each of those five platforms provides access to a large proportion of the full sample of 124 specialized films, with 92 percent available on Amazon Prime Video, 90 percent on YouTube, 88 percent on Google Play, 82 percent on iTunes, and 77 percent on Magenta TV. There is also much overlap between the specialized films available on those platforms. If we take the ninety-six films available on Magenta TV, for instance, we can see that seventy-nine of those films (82%) are also available on Amazon Prime Video, YouTube, Google Play, and iTunes.30 If we draw a further comparison, we can see that the 79 films also represent the majority (64%) of all 124 specialized films online.

It is thus relatively easy for rights holders to enable access to the five platforms in this category, even though specialized films are often also available on a range of other platforms.

The second category of VOD platforms includes the four TVOD platforms, Maxdome (eighty-one films), Rakuten (seventy-two films), Videobuster (sixty-five films), and Chili (forty-nine films), with each of them appearing in yellow in Figure 3. Maxdome and Videobuster operate in Germany and Austria, Chili in Europe, and Rakuten internationally. While those platforms don’t provide access to as many specialized films as the largest TVOD platforms in the first category, they do provide wider access for a selection of films that are also available on platforms in the first category, and that explains why some films end up on a large number of platforms. If we look at the eighty-one films available on Maxdome, it becomes clear that sixty-two films (77%) are available on all five platforms in the first category. Other platforms in the second category also have high levels of similarity with platforms in the first category: Rakuten provides the same access for sixty of seventy-two films (83%), Videobuster for fifty-three of sixty-five films (82%), and Chili for thirty-four of forty-nine films (69%). On the other hand, there is variation between platforms in the second category in terms of the films that they select. If we take the forty-nine films available on Chili, we can see that only sixteen films (33%) of those films are also available on Maxdome, Rakuten, and Videobuster.31 Rather than providing access to the same films, this suggests that their content strategies are more selective.

The third and last category that can be identified in Figure 3 includes both TVOD and SVOD platforms. This category comprises a larger number of ten platforms (of which six are TVOD and four SVOD), which appear in green in Figure 3. Some are international operators, in which the provision of film content in Germany is just a small part of their overall business offer. That includes SKY (TVOD), SKY Ticket (SVOD), Amazon (SVOD), Netflix (SVOD), and Microsoft. Others are much smaller and often specific to Germany and Austria. That includes Pantaflix, Flimmit, Kino on Demand, Joyn (SVOD), and Alles Kino. The availability of specialized films on the ten platforms in the third category is relatively low. Pantaflix provides access to thirty films, SKY to twenty-nine films, Flimmit to twenty-three films, Amazon (SVOD) to nineteen films, Kino on Demand to sixteen films, and Joyn (SVOD) to thirteen films. The remaining four platforms provide access to less than ten films each: Netflix, Microsoft, and Alles Kino (nine each), and Sky Ticket (SVOD) with just seven films. Despite their relatively low engagement with specialized films, collectively they still provide access to 89 of the 124 specialized films (72%) available online. Their selections are thus spread across a wide range of specialized films. While some platforms select some of the same films as the others, there can also be huge differences between them. There is, for instance, little overlap between Amazon’s SVOD offer and Netflix, with Victoria (2015) being the only specialized film available on both SVOD platforms. Further, the specialized films available on TVOD platforms Kino on Demand and Microsoft do not overlap at all. It is also worth noting that there is little overlap between SKY’s TVOD and SVOD platforms, with only two of the same specialized films available on both platforms.

Because the film selections made by platforms in the third category are more diverse, they provide online access for some films that are unavailable on platforms in the first and second category. There are four cases where films are available on just one platform: Tabu (2011) on Pantaflix, Sister (2011) on Pantaflix, In the Fog (2011) on Pantaflix, and Nocturama (2016) on Netflix. On the other hand, the remaining eighty-five films on show on platforms in the third category are also available on platforms in the first and/or second category, which suggests that their contribution to the online market for such films revolves around making specialized films available on a larger number of platforms. The dynamic between providing access on a large number of platforms and providing limited access is of course subject to change. Clearly, more films become exclusively available on some VOD platforms due to investments in in-house, original productions. Although that development does not really come forward in this analysis, it has already affected circulation patterns for specialized films on platforms like Netflix, and that will continue to affect circulation patterns for such films in the next few years.32

Overall, the three categories of platforms are associated with different circulation patterns for specialized films. These circulation patterns can be analyzed in relation to assumptions about content abundance. The first category exemplifies the logic of abundance, although not to the extent of providing unlimited availability, access, or choice. But the second and third categories demonstrate that the meaning of the concept of abundance is more complex than often assumed. We could hardly say that Netflix (category three) with a catalog of thousands of films is not at all associated with the logic of abundance, but the contrast with platforms in category one is clear. It thus seems problematic to use a single concept of abundance to describe the often quite different content strategies and selections of the companies that might be seen as making an abundance of film titles available to audiences.

Specialized Films in Cinemas and Online

Having analyzed online circulation patterns, the study will now explore how these patterns compare to the circulation of films in the theatrical cinema market. The performance of films in cinemas often impacts on their performance in subsequent release markets. As trade observer Geoffrey Macnab notes, the theatrical cinema market is traditionally regarded as the “engine that drives the ancillary sales.”33 To what extent, then, do specialized films benefit from theatrical cinema exhibition? And what is the relationship between the performance of films in cinemas and the number of platforms on which they are available in the online market? On the one hand, films become more attractive for platforms if they perform well in cinemas, with the effect that they circulate more widely in the online market. On the other hand, there are also opportunities for less marketable films to gain access to a relatively high number of platforms.

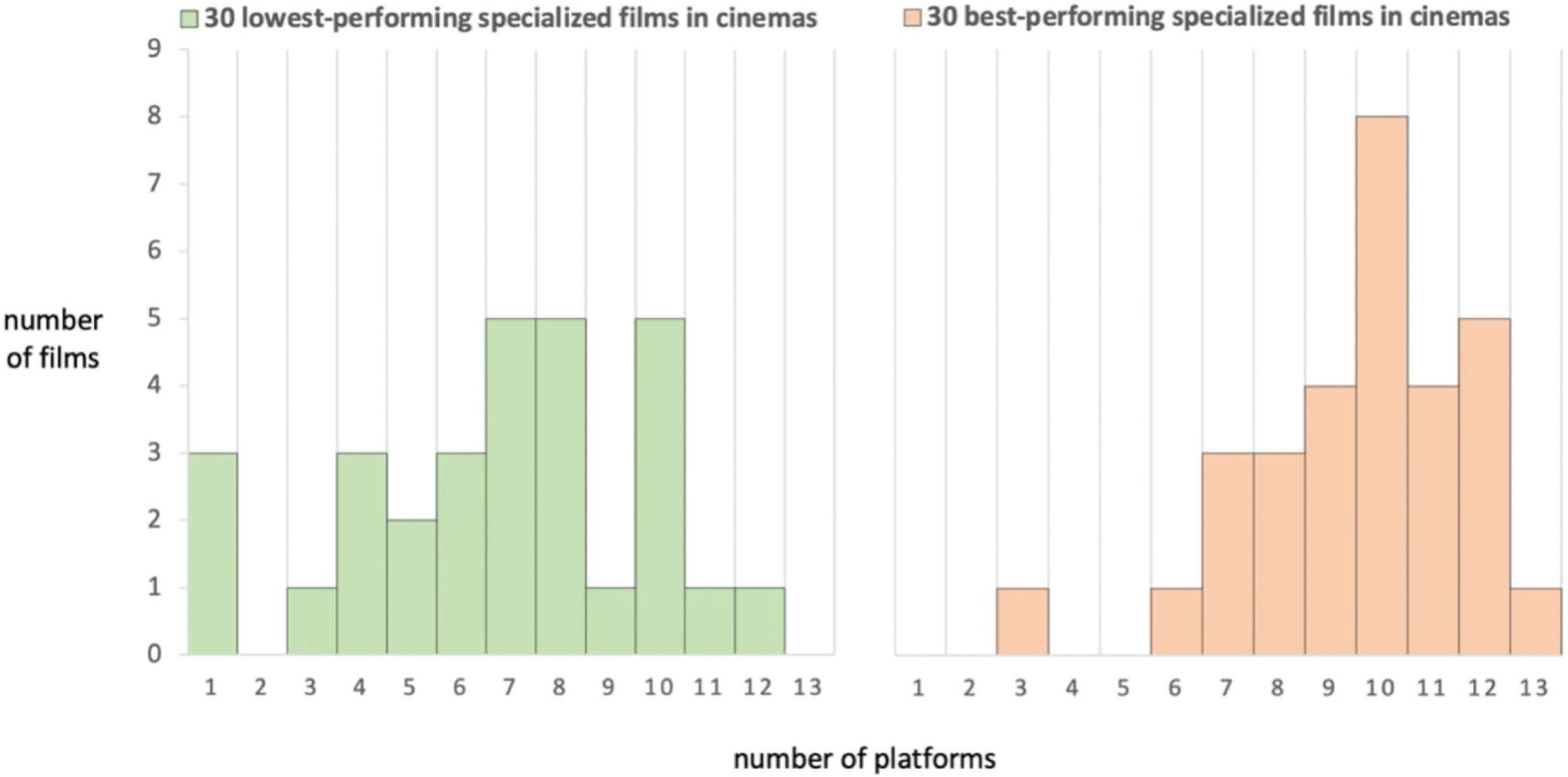

We can first establish how the availability of specialized films in the theatrical cinema market relates to the online market. This analysis is based on additional data provided by The German Association for Film Distributors about the theatrical release of films in German cinemas, including their box-office performance and the number of screens on which they were shown at the widest point of release.34 From the sample of 124 specialized films available in the German online market, a large number of 120 films were first released in German cinemas. On the basis of those 120 films, it is possible to analyze associations between the commercial performance of specialized films in cinemas and the range of platforms on which they are available. In order to do this, the sample of 120 specialized films was narrowed to the 30 best-performing films (with cinema revenues above €650,000), and the 30 lowest-performing films (with cinema revenues below €100,000). Beyond their performance in cinemas, the difference between the categories is also noticeable in terms of the scale of their release: the 30 best-performing films were shown on between 59 and 400 screens at the widest point of release in Germany, while the 30 lowest-performing films were shown on between 19 and 80 screens at the widest point of release.

In terms of online availability and circulation patterns, Figure 4 confirms that there is a relationship between the cinema release and the online release, demonstrating that the best-performing films in cinemas (appearing in pink) are more often available on a higher number of platforms than the lowest-performing films (appearing in green). That is of course not a surprising observation in itself, but it allows for more insight into circulation patterns. Of the thirty best-performing films, the majority (twenty-eight films) were available on more than six platforms. In fact, their availability is particularly concentrated around some of the highest categories: eight films are available on ten platforms, four on eleven platforms, and five on twelve platforms. Well-performing films in cinemas are thus likely to circulate on a large number of VOD platforms. By comparison, online availability of the thirty lowest-performing films in cinemas is spread over a greater range of platforms, with nine films available on less than six platforms, thirteen on six to eight platforms, and only eight on more than eight platforms. Circulation patterns for this category of films are thus more fluid and elastic than the thirty best-performing films.

Implicit in arguments about the relationship between box-office performance and online availability are industrial operations of circulation power. The fact that the best-performing films are able to secure wider access suggests that they are supported by distributors with a larger number of VOD platforms in their networks. To that extent, processes of film circulation in the online market are a consolidation of power dynamics established in the theatrical cinema market, the DVD and Blu-ray market, and the television market.

Conclusions

While VOD platforms continue to strengthen the market for online viewing of films, television series, and other content, discussions about online circulation, diversity of content in VOD catalogs, and access to markets will undoubtedly receive more traction. This paper has demonstrated that the online market has helped the nature of film distribution to evolve, according to different circulation logics and patterns. Those developments are associated with the process of market fragmentation. As a consequence, it is far too crude to rely on a simple binary opposition between abundance and scarcity. The situation for specialized films is far more complex. Online access and availability are now based on a blending of different business models, distribution strategies, and content selections.

Looking at the scope and stretch of online circulation patterns of specialized films suggests that we need further research about the operations of circulation power and online distribution processes. To understand circulation power involves first of all analyzing how films become available. That requires acquiring a deeper understanding of gatekeeper arrangements between sales agents, distributors, content aggregators, and VOD platforms to reveal the motivations behind the process of making films available and visible. But with the market for VOD platforms becoming more fragmented and changing release strategies for films, there are also more challenges to acquire a comprehensive insight into gatekeeper arrangements and licensing deals that shape and structure film circulation patterns.

Notes

- Dr. Roderik Smits is Research Fellow at Universidad Carlos III de Madrid. He is currently undertaking the research project “Online Platforms and Film Circulation” (www.onlinefilmcirculation.com). He acknowledges support from the CONEX-Plus programme funded by Universidad Carlos III de Madrid and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 801538. He would also like to acknowledge valuable feedback from Andrew Higson, Skadi Loist, Luis A. Albornoz, and two anonymous reviewers on drafts of this paper. ⮭

- David Hesmondhalgh and Amanda Lotz, “Video Screen Interfaces as New Sites of Media Circulation Power.” International Journal of Communication 14 (2020): 390. ⮭

- Luis A. Albornoz and Ma Trinidad García Leiva, eds., Audiovisual Industries and Diversity in the Digital Age (London: Routledge, 2019); Virginia Crisp, Film Distribution in the Digital Age: Pirates and Professionals (Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave, 2016); Ramon Lobato, Netflix Nations: The Geography of Digital Distribution (New York: New York University Press 2019); Amanda Lotz, Portals: A Treatise on Internet-Distributed Television (Ann Arbor, MI: Maize Books, 2017); Roderik Smits, Gatekeeping in the Evolving Business of Independent Film Distribution (Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave, 2019). ⮭

- Andrew Higson, “Netflix – The Curation of Taste and the Business of Diversification,” Studia Humanistyczne AGH 20, no. 4 (2021): 7–25; Constantin Parvulescu and Jan Hanzlík, “The Peripheralization of East-Central European Film Cultures on VOD Platforms,” Iluminace 33, no. 2 (2021): 5–25; Diane Burgess and Kirsten Stevens, “Taking Netflix to the Cinema: National Cinema Value Chain Disruptions in the Age of Streaming,” Media Industries 8, no. 1 (2021): 1–22; Mike van Esler, “In Plain Sight: Online TV Interfaces as Branding,” Television & New Media 22, no. 7 (2020): 727–42; Mattias Frey, Netflix Recommends: Algorithms, Film Choice, and the History of Taste (Oakland: University of California Press, 2021); Jan Hanzlik, “Limiting the Unlimited: Curation in Czech Film Distribution in the Digital Era,” Studies in Eastern European Cinema 11, no. 3 (2020): 262–78; Petr Szczepanik, Pavel Zahrádka, Jakub Macek, and Paul Stepan, eds., Digital Peripheries: The Online Circulation of Audiovisual Content from the Small Market Perspective (Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2020); Roderik Smits and Elliot W. Nikdel, “Beyond Netflix and Amazon: MUBI and the Curation of On-Demand Film,” Studies in European Cinema 16, no. 1 (2019): 22–37. ⮭

- There are also research projects that focus specifically on the circulation the films: “Film Circulation on the International Film Festival Network” (www.filmcirculation.net) and “Online Platforms and Film Circulation” (www.onlinefilmcirculation.com). ⮭

- Hesmondhalgh and Amanda Lotz, “Video,” 389. ⮭

- Travis Clark, “New Data Shows Netflix’s Number of Movies Has Gone Down by Thousands of Titles since 2010—But Its TV Catalog Size Has Soared,” Insider, February 20, 2018. ⮭

- Soda Staff, “Netflix’s Movie Catalog Has Shrunk by 40% since 2014,” Soda, December 3, 2019. ⮭

- Nicolas Suzor, Tess Van Geelen, Kylie Pappalardo, Jean Burgess, Patrik Wikström, and Yanery Ventura-Rodriguez, “Australian Consumer Access to Digital Content,” Australian Communications Consumer Action Network, 2017. ⮭

- Lobato and Scarlata have produced reports in 2017, 2018, and 2019. See, for instance, Ramon Lobato and Alexa Scarlata, “Australian Content in SVOD Catalogs: Availability and Discoverability.” Report. Melbourne: RMIT University, 2019. ⮭

- For example, Christian Grece, “Films in VOD Catalogues: Origin, Circulation and Age.” Report. European Audiovisual Observatory, 2018; Christian Grece and Marta Jiménez Pumares, “Film and TV content in TVOD and SVOD catalogues, 2021 Edition.” Report. European Audiovisual Observatory, 2021. ⮭

- Lobato and Scarlata, “Australian Content in SVOD Catalogs,” 16. ⮭

- In the period from 2017 to 2021, I was a project member of the UK AHRC-funded research project “Beyond the Multiplex: Audiences for Specialised Film in English Regions” (www.beyondthemultiplex.net). It was the first major study to analyze how specialized films can reach diverse film audiences in English regions outside London. We used the term specialized films in our publications (www.beyondthemultiplex.org/about/outputs). ⮭

- Differences between the mainstream market and specialized market for films are discussed in several publications, including Deborah Allison, “Multiplex Programming in the UK: The Economics of Homogeneity,” Screen 47, no. 1 (2006): 81–90; Paul McDonald, “What’s On? Film Programming, Structured Choice and the Production of Cinema Culture in Contemporary Britain,” Journal of British Cinema and Television 7, no. 2 (2010): 264–98; Huw D. Jones, “The Box Office Performance of European Films in the UK market,” Studies in European Cinema 14, no. 2 (2017): 153–71. ⮭

- Statista, “Video on Demand – Germany.” 2020. https://de.statista.com/outlook/dmo/digitale-medien/video-on-demand/deutschland. Statista revenue predictions are usually based on information extracted from a combination of sources, including market data from independent databases, third-party organizations, and financial reports of key market players. Revenue predictions were based on the development of the online market before the COVID-19 pandemic. ⮭

- See, for instance, Ramon Lobato and Amanda Lotz, “Beyond Streaming Wars: Rethinking Competition in Video Services,” Media Industries 8, no. 1 (2021): 89. ⮭

- Creative Europe, “Distribution – Selective Support.” 2020, https://www.eacea.ec.europa.eu/grants/2014-2020/creative-europe/distribution-selective-scheme-support-distribution-non-national-films-2019_nl. ⮭

- The following textual and industrial criteria were applied to identify specialized films: Is the film aesthetically, socially, and/or culturally distinct from the mainstream, with an emphasis on educational stories told in innovative ways? Did the film travel through the international festival circuit? Was the film produced on a budget below €20 million? Was the film released on less than 200 cinema screens in the opening weekend in Germany? ⮭

- Data about German distributors that received funding was extracted from reports published by Creative Europe, for the period from 2011 to 2018: www.creativeeuropeuk.eu/funding-opportunities/distribution-selective. ⮭

- For German films with a lead production company from Germany, a German distributor becomes usually attached in the development or production stage. Data about the lead production country was collected from IMDb (www.imdb.com) and the Cineuropa film database (www.cineuropa.org/en/filmshome). ⮭

- The German Association for Film Distributors provided data about theatrical cinema release of all 150 specialized films in Germany, during the period between 2011 and 2018. In terms of films funded by the distribution selective program in 2018, they were all given a theatrical cinema release in Germany before COVID-19 was declared a pandemic in Germany by late February 2020. ⮭

- The IMDb and the Cineuropa databases were used to identify (minority) coproducers. ⮭

- Both aggregators are supported by the Creative Europe Media program. JustWatch is a database that enables audiences to search for the availability of films and television series on VOD platforms (www.justwatch.com); Lumiere VOD is also a database that provides insight into the availability of films, but that insight is deliberately restricted to European films (lumierevod.obs.coe.int). I used both databases for cross-checking purposes. For 17 films of the full sample of 150 films, Lumiere VOD and JustWatch provided different numbers for the availability of films on online VOD platforms in Germany. In the case of such differences, I consulted individual VOD platforms to identify where films were available. ⮭

- Data about online availability is provided for TVOD and SVOD platforms through JustWatch and Lumiere VOD, while AVOD (advertising VOD) platforms are not included. All TVOD and SVOD platforms are legal, meaning that audiences pay to access content. ⮭

- A small sample of twenty films was analyzed in October 2020 and February 2021 in order to cross-check the availability of those films over a longer period of time, but availability remained largely the same. ⮭

- Paul McDonald, Courtney Brannon Donoghue, and Timothy Havens, eds., Digital Media Distribution: Portals, Platforms, Pipelines (New York: New York University Press, 2021). ⮭

- Smits, “Gatekeeping,” 3. ⮭

- The function of a sales agent is to secure distribution deals for films in international territories. They usually work together with distributors to release films in individual territories. Content aggregators have appeared in the global marketplace to secure online distribution for films. ⮭

- None of those five films are so-called in-house, original productions. They were also released by different distributors in Germany. Four films were first released in German cinemas before they became available in the online market and elsewhere. One film (Nocturama, 2016) is a French–German–Belgium coproduction that was acquired by Netflix for the German market on a non-exclusive basis. It was also released in the German television market. ⮭

- Magenta TV is selected for this example because it provides access to less specialized films than other platforms in the first category. ⮭

- Chili is selected for this example because it provides access to less specialized films than other platforms in the second category. ⮭

- The development of original films does not really come forward in the analysis because the database is based on a sample of 150 films for which distribution selective funding was awarded in the period between 2011 and 2018. Investment in original productions has increased more in recent years, for a growing number of films. ⮭

- Geoffrey Macnab, “Ways of Seeing: The Changing Shape of Cinema Distribution,” Sight & Sound, August 2016, 26th edition. ⮭

- German Association for Film Distributors, “Database for 150 Specialized Films.” ⮭

Bibliography

Albornoz, Luis A., and Ma Trinidad García Leiva, eds. Audiovisual Industries and Diversity in the Digital Age. London: Routledge, 2019.

Allison, Deborah. “Multiplex Programming in the UK: The Economics of Homogeneity.” Screen 47, no. 1 (2006): 81–90.

Burgess, Diane, and Kirsten Stevens. “Taking Netflix to the Cinema: National Cinema Value Chain Disruptions in the Age of Streaming.” Media Industries 8, no. 1 (2021): 1–22.

Crisp, Virginia. Film Distribution in the Digital Age: Pirates and Professionals. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave, 2016.

Frey, Mattias. Netflix Recommends: Algorithms, Film Choice, and the History of Taste Oakland: University of California Press, 2021.

Hanzlik, Jan. “Limiting the Unlimited: Curation in Czech Film Distribution in the Digital Era.” Studies in Eastern European Cinema 11, no. 3 (2020): 262–78.

Hesmondhalgh, David, and Amanda D. Lotz “Video Screen Interfaces as New Sites of Media Circulation Power.” International Journal of Communication 14, no. 24 (2020): 386–409.

Higson, Andrew. “Netflix – The Curation of Taste and the Business of Diversification.” Studia Humanistyczne AGH 20, no. 4 (2021): 7–25.

Fontaine, Gilles. The Visibility of Audiovisual Works on TVOD. Report. European Audiovisual Observatory, 2019.

Grece, Christian. Films in VOD Catalogues: Origin, Circulation and Age. Report. European Audiovisual Observatory, 2018.

Grece, Christian and Marta Jiménez Pumares. Film and TV content in TVOD and SVOD catalogues, 2021 Edition.” Report. European Audiovisual Observatory, 2021.

Jones, Huw D. “The Box Office Performance of European Films in the UK Market.” Studies in European Cinema 14, no. 2 (2017): 153–71.

Macnab, Geoffrey. “Ways of Seeing: The Changing Shape of Cinema Distribution.” Sight & Sound 26 (2016).

McDonald, Paul. “What’s On? Film Programming, Structured Choice and the Production of Cinema Culture in Contemporary Britain.” Journal of British Cinema and Television 7, no. 2 (2010): 264–98.

McDonald, Paul, Courtney Brannon Donoghue, and Timothy Havens, eds. Digital Media Distribution: Portals, Platforms, Pipelines. New York: New York University Press, 2021.

Lobato, Ramon. Netflix Nations: The Geography of Digital Distribution. New York: New York University Press, 2019.

Lobato, Ramon, and Amanda Lotz. “Beyond Streaming Wars: Rethinking Competition in Video Services.” Media Industries 8, no. 1 (2021).

Lobato, Ramon, and Alexa Scarlata. Australian Content in SVOD Catalogs: Availability and Discoverability. Report. Melbourne: RMIT University, 2019.

Lotz, Amanda D. Portals: A Treatise on Internet-Distributed Television. Ann Arbor, MI: Maize Books, 2017.

Parvulescu, Constantin, and Hanzlík Jan. “The Peripheralization of East-Central European Film Cultures on VOD Platforms.” Iluminace 33, no. 2 (2021): 5–25.

Smits, Roderik. Gatekeeping in the Evolving Business of Independent Film Distribution. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019.

Smits, Roderik, and Elliot W. Nikdel “Beyond Netflix and Amazon: MUBI and the Curation of On-Demand Film.” Studies in European Cinema 16, no. 1 (2019): 22–37.

Szczepanik, Petr, Pavel Zahrádka, Jakub Macek, and Paul Stepan, eds. Digital Peripheries: The Online Circulation of Audiovisual Content from the Small Market Perspective. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2021.

Van Esler, Mike. “In Plain Sight: Online TV Interfaces as Branding.” Television & New Media 22, no. 7 (2020): 727–42.