Throughout the country and across the globe, a new type of street band movement is emerging—outrageous and inclusive, brass and brash, percussive and persuasive—reclaiming public space with a sound that is in your face and out of this world…. These bands don’t just play for the people; they play among the people and invite them to join the fun…. This is the movement we call HONK!.1

So reads the “About HONK!” page of the original annual HONK! Festival in Somerville, Massachusetts, in the Boston area. In the years following its inception in 2006, annual, noncommercial HONK! Festivals featuring community-based bands sprouted up across the United States, Australia, Europe, Brazil, and other parts of the Americas, numbering nearly two dozen at the time of this writing. Committed to filling public spaces with crowds and the acoustic music of alternative brass and percussion ensembles, the HONK! Festival network is committed to live, ephemeral, and “unmediated” musical experiences imbued with physical and social intimacy.

The above description of HONK! bands was written before the COVID-19 pandemic swept the globe in 2020, as “in your face” playing “among the people” in “public space” came to represent exactly the kind of behavior that could spread the deadly virus. When it suddenly became clear that such gatherings would be impossible in 2020, every HONK! Festival around the world was cancelled. While many social activities abruptly transferred to online platforms due to the pandemic, HONK! Festivals may have seemed to be unlikely candidates for going virtual, given their commitment to physically sharing space. In the place of in-person festivals, however, the global HONK! network began to conceive of a virtual festival they called “HONK!United” that would connect the diffuse network in this precarious moment. Over the course of fifty hours during eight days in October 2020, HONK!United brought together musicians and activists from all seven continents, sharing music videos, documentaries, live-streamed real-time performances, live chats, workshops, and panels.

The fact that the HONK! Festivals went online in 2020 is, of course, nothing unusual. Events of all sorts, including music festivals, opted for a virtual format in the face of the pandemic’s unprecedented challenge to the physical human encounters on which the HONK! movement had based its identity. But HONK!United’s capacity to link community movements around the globe that had been in some cases only tangentially related represents a case that is largely distinct from the majority of commercial music festivals that reproduced online “presentational” performances to a mostly preexisting fan base,2 which typified many virtual music festivals during the pandemic. The HONK! family of festivals had grown to be transnational before the pandemic, mostly through informal meetings at festivals that planted the seeds for new festivals elsewhere. However, during a period one HONK!United MC called “quarantimes,” the virtual festival provided an innovative platform for these disparate communities to gain unprecedented self-consciousness as parts of a global movement rather than remain allied primarily with their local festivals and manifestations.

In this article, we argue that although the pandemic presented tremendous challenges to the sustainability of live music cultures, it also provided previously unimaginable opportunities for musical movement building across the world. The possibilities the pandemic posed for connection across distance marked a line in the sand in the process of the globalization of the HONK! movement from which there is no going back. After laying out our theoretical framework in the next section, we discuss (1) the practical and conceptual implications of making an in-person event virtual, (2) HONK!United’s novel approaches to festive gathering in a virtual format as it sought to engender feelings of solidarity in this precarious moment, and (3) the tensions between unity and diversity as bands and festivals from around the globe met in this virtual encounter under the banner of HONK!United.

This coauthored article draws on the long experience, participation, and collaboration of its three authors in the HONK! movement. Andrew Snyder is a trumpet player and co-founder of San Francisco’s Mission Delirium brass band; he is writing a book about the alternative brass movement of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, which grew out of the local carnival and took up the HONK! moniker when it threw the first annual HONK! Festival in Latin America in 2015. Erin Allen is writing a dissertation on the HONK! movement in the United States and is a trumpet player with Environmental Encroachment, one of the bands that has experienced the global reach of the HONK! movement firsthand through touring. Reebee Garofalo is one of the organizers of the original Somerville HONK! Festival, is a snare player in its host band—the Second Line Social Aid and Pleasure Society Brass Band—and was an active member of the Organizing Committee in the formation of the online HONK!United Festival. This article draws on our previous collaborative work as editors of a collection of essays on the global HONK! movement entitled HONK! A Street Band Renaissance of Music and Activism.3

We interviewed several participants in the virtual festival from around the globe, as well as the majority of the members of the Somerville HONK! Organizing Committee, which transformed itself into the HONK!United Organizing Committee in 2020, about their experiences translating the festival into the virtual sphere. Our scope of focus on HONK!United in this article is rooted in and largely restricted to the perspective of the original Somerville HONK! Festival organizers who played the major role in the organization of the online global festival. We therefore focus especially on the process of producing the festival and portray the wide variety of the offerings rather than focusing singular attention on any “representative” texts, which are in fact lacking because of the movement’s great diversity, and we would direct readers to the footage of the festival itself, as well as the videos featured in this article, for a stronger sense of the offerings. We strongly encourage further readings of the online festival and the global movement beyond this North American vantage point, as well as more focus on its reception or its diverse creative art forms. This article offers self-critical thoughts for the management of the global HONK! community going forward, as well as a case study on the pandemic’s impact on translocal musical communities more generally.

Pandemic Precarity, Solidarity, and Frictions

During in-person HONK! Festivals, masses of bodies converge in a contagion of music and joy in public spaces that are otherwise often neglected and experienced solely as points of passage between private spaces. Often in alliance with leftist social movements, bands mobilize people to assemble in ways that are understood by participants as reclaiming public space and contesting hegemonic powers that might view the occupation of public spaces as disorderly at best and politically threatening at worst. The festivals ideally present an ethical alternative to the neoliberal precarity that characterizes the lives of people all over the world and reduces their relationships to commoditized and privatized interactions. In contrast to neoliberal rationales, in-person HONK! Festivals can be understood as enacting what Judith Butler calls “performative assembly,” public gatherings that signify collective manifestations of persistence and resistance.4

What Cheer? Brigade playing in 2015 at PRONK! (HONK! in Providence, Rhode Island). Video by Erin T. Allen.

As economies shut down and lockdowns isolated people around the world, the possibility for the performative assembly that HONK! Festivals typically enact in person became impossible in 2020, and the interdependency of our physical, social, and economic health came into stark relief. It became apparent to many that our individual well-being relies on the well-being of others, revealing the failure of neoliberal self-sufficiency, the heightened precarity during the pandemic, and the stark inequalities of various institutions. The murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and other Black people sparked worldwide uprisings that called attention to the fact that some lives are more precarious than others.

It is precisely at such a moment of broad crisis that public assemblies like HONK! Festivals might demonstrate an alternative ethics of collectivity and care, sounding out an ethos of solidarity that affirms mutual dependency and the need for public space and social networks. Yet in 2020, the very thing that warranted collective public response, COVID-19, rendered in-person assembly difficult or impossible. Butler has asked what it means “to act together when the conditions for acting together are devastated or falling away? Such an impasse can become the paradoxical condition of a form of social solidarity both mournful and joyful, a gathering enacted by bodies under duress or in the name of duress, where the gathering itself signifies persistence and resistance.”5 Moreover, Butler argues that long-distance solidarities can create translocal public assemblies, and HONK!United sought to facilitate such a possibility to act together when the conditions for doing so appeared impossible. Though collective music-making in the virtual format of HONK!United organized people differently in space and time than in-person HONK! Festivals, the online festival nevertheless sought to provide a mode of public assembly that might counter some of the isolating effects of the pandemic. Despite the limitations of the online forum, festival organizers aimed, somewhat paradoxically and innovatively, to maintain the in-person festivals’ core principles, including senses of liveness, social intimacy, participation, and solidarity.

Across this global expression of solidarity, however, the differences and diversity within the movement were all the more on display than they would be in their local in-person settings. The online festival presented a stark juxtaposition of cultural movements under the HONK! banner that was accessible for free all over the world. In the virtual format, the movement became aware of itself as a self-consciously more cosmopolitan and culturally dynamic movement than it had been before. However, as in any global encounter, issues of inequity, (un)common goals and values, and hierarchy challenge any narrative of HONK!United as simply a celebratory example of global, participatory solidarity. How much do bands coming from such radically different cultural contexts really have to do with one another? What happens when a dispersed network of movements adapted to local circumstances suddenly meets itself online? What might we learn from looking at HONK!United about the impact of the pandemic on translocal connections? At the end of the day, just how united is HONK!United?

Anna Tsing has argued that “globalization” does not simply result in a hegemonic top-down framework of control, transnational harmony, or ineluctable “clashes of cultures,” but rather “unpredictable, messy misunderstandings, but misunderstandings that sometimes work out.” She develops the concept of “friction” as “the awkward, unequal, unstable, and creative qualities of interconnection across difference.”6 Importantly, while there are myriad controversies in the HONK! community as in any community, Tsing specifically develops the physical metaphor of friction as a value-neutral one—what happens when different things rub up against each other—and our use of her term is not necessarily meant to imply (or exclude) conflict, but rather point to the generative impacts emerging from encounters of difference. Friction occurs when cultural “universals” meet “particulars”; by “universals,” Tsing refers to ideologies and cultural practices that presume applicability across the “particulars” of diverse cultures, and, importantly in the case of HONK!, for Tsing universals can be liberatory as well as imperialistic. Tsing argues that universals never fully absorb cultural particulars, and “[a]ctually existing universalisms are hybrid, transient, and involved in constant reformulation through dialogue.”7 Drawing on Tsing’s framework, we suggest that HONK!United presented such a forum for reformulation through dialogue, creating a new chapter in the movement’s history. We understand “HONK!” as a set of “universal” ideas about musical practices and activism colliding with “actually existing” particular practices around the globe that create new hybridities.

Central to the way these hybridities encountered each other in the virtual HONK!United Festival is a tension in how the HONK! movement had grown globally out of the Somerville Festival on the one hand but has been transformed by and combined with preexisting practices around the world on the other. There is a certain family tree lineage to festivals that have adopted the HONK! name, as emerging HONK! Festivals often consider HONK! Somerville to be the “mothership” and sometimes look with deference to Somerville for guidance and leadership. Indeed, while Somerville, like all the other HONK! Festivals, canceled their 2020 live events, only Somerville took the initiative to contact festivals and bands around the world to create the virtual HONK!United Festival. At the same time, as we argue elsewhere, there are distinctly anarchic and autonomous elements to the way these festivals have sprung up and continue to operate that recall Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of the “rhizome.”8 Like the subterranean growth of mushrooms, the rhizome “connects any point to any other point” and is unlike the metaphor of a tree, which imposes structure, lineage, and hierarchy.9 Each local HONK! Festival before the pandemic negotiated these tensions between centripetal and centrifugal, or unifying and decentralizing, forces in their localized self-identification as part of a shared movement in different ways.10 The virtual HONK!United Festival, which put the global festivals together for the first time in the movement’s history, sought to promote diversification and decentralization while being largely managed by the Somerville “mothership.” This contradiction posed a central question for organizers as the online festival was being created, one that has important implications for the promotion of the HONK! community’s global solidarities going forward.

From Live to Virtual Brass Bands

The first seeds of Somerville’s HONK! Festival were planted when a ragtag pick-up brass ensemble came together in Boston in early 2003, to support a mass demonstration protesting the run-up to the second US war in Iraq. The musicians who participated enjoyed playing together so much that they decided to form a permanent band, which they called “The Second Line Social Aid and Pleasure Society Brass Band”—an homage to the music and culture of New Orleans. The Somerville band has continued to perform for protests and political events to this day, almost always for free. About two to three years into this project, the band began to wonder how many other bands like them existed. They put out a call, a dozen bands from all over the United States answered, and the HONK! Festival of Activist Street Bands was born as a convergence point for left-leaning bands, many of whom critically theorize and practice the tangible impact of their music in promoting social justice. At the time, organizers had no inkling of the global reach and attraction the festival would attain.11

For participating bands, HONK! Festivals are a celebration, a skill share, and a call to action. For the thousands of people who attend, they are moving spectacles of colorful marching bands, energetic dancers, gigantic puppets, creative bikers, jugglers, hoopers, flag twirlers, and stilt walkers, joined by unions, leftist activist organizations, and community groups. Until 2020, the essence of HONK! Festivals around the world has been tied to ephemeral, live performances, as they have sought to use the power of brass and percussion to encourage inclusionary practices, engage in participatory music-making, reclaim public spaces, build community, and fight for social justice. HONK! Festivals have been inspired by an ideal that Thomas Turino calls “participatory performance,” in which “there are no artist-audience distinctions, only participants and potential participants.”12 In this spirit, it has always been a goal of the HONK! movement to involve “audiences” in as many kinds of performative activities as possible—parading, chanting, dancing, and the like. While many alternative and activist brass bands, as well as related festive traditions like carnival, have, of course, long preexisted these festivals, “HONK!” gave the alternative brass band movement a name and a series of convergence points for the new millennium.

Over the years, HONK! bands have participated in myriad leftist activist movements, including anti-globalization protests, anti-Iraq war protests, the Occupy movements, Japan’s anti-nuclear protests, France’s Yellow Vests protests, the US Women’s Marches, Black Lives Matter, antifascist movements, and climate justice movements, among others. The first HONK! Festival of Activist Street Bands in Somerville openly promoted such efforts by explicitly defining itself as activist in the title of the festival. However, not all of the participating bands defined themselves as strictly activist, a fact that has contributed to ongoing debate and controversy over the festival’s core meanings.13 Contributing to the confusion about the term but benefiting from a lack of predefined meanings, Somerville has long rejected a strict definition of activism, inviting bands to interpret the label themselves, as can be seen below in the submission to HONK!United of New Orleans’s Young Fellaz Brass Band.

A HONK!United video submission showcasing New Orleans’ Young Fellaz Brass Band playing during a Black Lives Matter march in 2020.

Almost entirely left-leaning, many bands play on the front lines of protest, reinterpreting the militaristic capacities of brass bands for counter-hegemonic ends, while other bands define their activism through their inclusive approaches to music making and community outreach. Still others are more countercultural performance bands who share the aesthetics and politics of HONK! bands but might not be otherwise clearly engaged in activism. Festivals founded after Somerville, as discussed below, mostly dropped the activist label—preferring to use other terms such as “community” or “alternative”—as it became a source of controversy outside of the liberal Boston area, and some felt the term did not embrace the projects of many participating bands. Despite this fact, there emerged from the outset a broad set of principles between festivals—not always obvious or conventional ones—that seemed to fall into place quite naturally and made HONK! Festivals unique events from the start. The festival, as envisioned by the original Somerville organizers, is noncommercial with no corporate logos or sponsorships, no outside commercialism of any kind. The bands, with few exceptions, play for free in return for travel assistance and free food and lodging during the festivals. Food is cooked for and shared among hundreds of musicians, free homestays with locally-based HONK! musicians or other local hosts are provided, and bicycles and instruments are loaned.14

Many HONK! Festivals include educational opportunities, such as workshops or open pick-up bands available to bandless festivalgoers, as well as collaborations with activists and community organizers in support of a range of social justice issues or mutual aid initiatives, though each individual HONK! Festival focuses to differing degrees on these types of projects. Since all the bands are loud, acoustic, and mobile, there is no electricity, no sound reinforcement systems, and no gigantic speaker columns to mediate the music; no sound checks or set-ups to delay gratification; indeed, no stages anywhere to elevate the bands above the crowd, just music at street level, experienced up close and personal. Camaraderie, conviviality, and reunion between old and new friends at jam sessions, tune-shares, and afterparties last well into each night of the festivals.

Producing a festival like Somerville’s HONK! year after year has been a complicated undertaking with lots of moving parts. It requires considerable financial resources and the development of long-term relationships with local businesses, city administrations, funding agencies, unions, neighborhood groups, and progressive political organizations—groups that do not always share a common political outlook. Not surprisingly, the festival is, and always has been, rife with contradictions—accepting, for example, funds, material goods, and logistical support from city administrations and business entities to produce a festival that is anti-commercial and does not condone corporate sponsorships, or staging a parade with Vietnam Veterans for Peace in the parking lot of a Veterans of Foreign Wars clubhouse. Organizing HONK! Festivals is a messy affair, political purity is not an option, and the question for festivals has been how well organizers learn and grow from managing such contradictions. Such tensions had presented mostly local questions for individual festivals, but they would take a global turn in HONK!United.

In its first two years, the Somerville HONK! Festival doubled in size, and with the event growing in popularity every year, the question of how to manage this growth confronted the Somerville organizers early on. Faced with becoming a victim of its own success, the Organizing Committee made a crucial decision: rather than outgrow its local venues and community roots, the committee decided to keep the festival to a manageable size and to expand by encouraging other bands to start their own HONK! Festivals in their own cities and towns. The first was Seattle in 2008 with HONK! Fest West. Festivals in Providence, Rhode Island, and New York City evolved as a natural continuation of the Somerville Festival. Bands from Austin, Texas, and Detroit, Michigan, formed their own homegrown festivals. By the mid-2010s, HONK!’s expansion took an international turn with the debut of HONK! Rio in 2013, HONK! Oz in Wollongong, Australia, in 2015, HONK! BC in Vancouver in 2018, and HONK! London in 2019. By 2020, when the pandemic hit, there existed some 22 HONK! Festivals on four continents, with five in Brazil, two each in Australia, Canada, and England, one in Costa Rica, and the rest in cities and towns across the US. Though the new festivals around the world that took up the HONK! moniker all brought innovative and local elements to their versions, they largely retained a commitment to Somerville’s organizing principles. In the late 2010s, HONK! Somerville released a list of requests to new festivals using the term HONK! that they stay true to the festival’s noncommercial, free, accessible, acoustic, and community-based spirit.15 Otherwise, HONK! Somerville has not sought to impose directives on the rhizomatic growth of the HONK! movement.

As the HONK! Festivals have grown global, they have been most available to those with access to international travel and information and have, therefore, been predominantly, but not solely, middle-class phenomena. In the United States, bands that consider themselves part of the HONK! community are predominantly white, with significantly more diversity along the lines of age, gender, and sexuality.16 Similarly, in Brazil, HONK! Festivals belong to a demographic known there as the “alternative middle classes,” which also tend to be whiter despite these festivals taking place in a much more racially mixed country.17 Confronting challenges of diversification common to many privileged leftist scenes, HONK! festivals have explicitly sought to increase the diversity of participants over the years.

In the case of Somerville, the organizers have sought to showcase all-women and gender nonconforming bands and to bring Haitian rara and Black New Orleans street bands into the HONK! orbit. Somerville often prioritizes much of its budget on bringing bands from marginalized communities to the festival, while more privileged bands are expected to pay at least some of their own way to the festival. Other HONK! Festivals around the world have sought to diversify themselves in other ways, such as HONK! Rio’s regular featuring of Favela Brass, a music education social project based in a marginalized neighborhood of Rio de Janeiro.18 Before the pandemic, international travel had been another element of diversification of local festivals, which increased contact between the Americas and Europe and later Latin America, as well as with Asia since the participation of Japan’s Jinta-la-Mvta in HONK! Fest West in 2017.

Although HONK! around the world is generally the product of a whiter, middle-class, and urban demographic, the participation of increasingly diverse participants makes it simplistic to limit a description of HONK! to any one demographic. Broader inclusion and increased diversity have remained prominent among the goals and aspirations for the life of the festivals, an aim that would be pursued in the virtual HONK!United Festival. Despite the limits of demographic diversity, HONK! bands draw on a broad variety of repertoires, performance styles, and inspiration from sources as diverse as punk, rock, and reggae; Balkan, Klezmer, and Romani influences from Eastern Europe; the Latin American sounds of samba, cumbia, banda, and salsa; and the New Orleans second line tradition. This juxtaposition of the demographic limitations of band membership with their wildly eclectic musical sources has led to heated debates about issues of tribute vs. appropriation19 and economic reward.20

In a typical year, HONK! Festivals are spaced throughout the calendar year to maximize the availability of bands to tour different festivals. Yet 2020, of course, was not a typical year. The COVID-19 pandemic struck just as Somerville was beginning to plan its 2020 festival, which was to take place in October. One by one, other HONK! Festivals that were scheduled for the first half of the year began to cancel their events. The HONK! Somerville committee initially tried to imagine anything and everything that would preserve the large-scale live performance aspects that defined HONK!, but to no avail. Clearly, international travel would be off the table. Housing and feeding hundreds of musicians would be out of the question. Performances that attracted large crowds would be unsafe and forbidden by local ordinances. It seemed like the best Somerville’s festival committee could hope for would be a hyper-local event, limited to bands from the immediate area, with small, invitation-only performances that would be socially distanced and small unannounced parades on secondary streets that would disperse before a crowd could form. By the time the long-term reality of the pandemic became apparent in the spring of 2020, well over 100 bands had been contacted to apply to Somerville’s HONK! Festival. As the festival organizers pondered how best to communicate their plight to these bands, it occurred to them that all of the individual HONK! Festivals were in the same situation. So, instead of eliminating HONK! outright, Somerville HONK! organizers initially invited everyone to stage a performance in their own locale on the same dates that would have marked Somerville’s HONK! Festival. In their letter to bands canceling the Somerville HONK! Festival, organizers instead proposed “a radically different, hyper-local, (re)conception of HONK!” called “HONK!United:”

… HONK! is everywhere—that is, everywhere there is an outrageous and unruly street band capable of producing a joyful noise in the street…. So, even though we can’t all gather in one place this year, we can make a statement at the same time. Let’s expand HONK! to locations far and wide. We invite you to host a local event in your own community on the same weekend as ours. Let’s all play in the streets of our hometowns on the same day—a “glocalized” international festival of activist street bands united by the belief in music for social change. What would it be like to celebrate HONK! in Seattle, Spokane, Eugene, New York, Providence, Madison, Atlanta, New Orleans, Austin, Rio, Wollongong, Detroit, Montpelier, Montreal, Vancouver, Paris, Rome, Pittsburgh and elsewhere?21

Festival organizers asked the bands for their “suggestions, reactions, critiques, concerns,” and the response was overwhelming and uniformly enthusiastic. But as the tragedy of 2020 rolled on, it became clear that encouraging even small local events around the world involved unacceptable levels of risk. The notion of any kind of physical encounter was scrapped, but the conception of simultaneous HONK!s around the world that was the HONK!United proposal was ultimately transferred, as were so many encounters in 2020, to the virtual realm. Attempting to keep things manageable, the newly formed HONK!United Festival Organizing Committee, which evolved out of the Somerville Organizing Committee’s call to other Festivals, proceeded to plan HONK!United as a two-day virtual festival, with Saturday, October 10, devoted to live-streamed or pre-recorded musical performances and interviews, and Sunday, October 11, reserved for a series of workshops and panel discussions.

As the “mothership” of the HONK! movement and having put out the original HONK!United call, Somerville took the lead on the project of virtually linking movements around the world. Even the initially modest conception of HONK!United required a radical reorganization of Somerville’s normal operating procedures, which typically involved regular in-person meetings and email communication. Control over the various aspects of HONK!United was also significantly dispersed by the sheer expansion of personnel needed to coordinate the operation. While the Somerville Committee normally operates as a group of a dozen or so people who live within a few miles of each other, active organizing members of HONK!United numbered four times that many and were much more widely dispersed. The Technology Committee, for example, was initiated by Alison Earnhart from the Somerville group, but it attracted some twenty-five members, albeit with a handful of volunteers doing the heavy lifting for the live stream, which was coordinated by Aireekah Laudert, a volunteer from the Seattle area. To keep track of the complexity of international communication required for HONK!United, the Somerville Organizing Committee’s normal, if inefficient, use of email as their primary means of communication, quickly gave way to the creation of a dozen or more Slack channels to streamline conversation threads, including Festival Concept Committee, Coordinating Committee, Bands, Live Events, Somerville Broadcast Segment, Technology, Workshops, Public Relations, Social Media, Graphic Design, Budget, and Political Actions. As many other communities and businesses experienced during the pandemic, the demands of online work required new uses of technology that could promote engagement among a wide range of participants dispersed around the globe.

The Somerville organizers were aware that by proposing to host HONK!United on the weekend that would have been the Somerville Festival, there was a danger of making Somerville more central to the effort than was desired. They aimed to provide, in their words, “leadership but not control” and to involve organizers from around the globe. Accordingly, the Organizing Committee’s commitment to bands submitting content was that they would accept videos “as provided” as long as they conformed to certain technical specifications. At the same time, a certain amount of curation fell to the host committee regarding scheduling and editing for length, clarity, or content, where necessary. In the end, what was envisioned as a two-day virtual festival turned into eight days of programming, with seventy bands from all seven continents—yes, even Antarctica fielded a brass band until their valves froze—which was live streamed on multiple platforms, included considerable interactivity, and has since been archived on the HONK! YouTube channel available to all.22 The opportunity the pandemic offered to unite the globally disparate community was well portrayed by the face masks featuring the HONK!United logo designed for the event.

Public Assembly in Virtual Space

As the organizers planned the virtual version of HONK!United, at the forefront of their minds was the question of how the ephemeral, live experience of public assembly at in-person HONK! Festivals could be transferred to the virtual space of the Internet in a satisfactory way. This process involved negotiating a series of apparent contradictions.

HONK! bands typically abstain from using amplification or electronic technology, drawing their inspiration primarily from the diverse brass and percussion traditions around the world, with some creative exceptions. As this acoustic aesthetic was translated to the virtual medium, however, tension emerged with the heavy reliance on new technological tools. The message broadcasted before every HONK!United event, for example, depicted HONK! bands similarly to their pre-pandemic manifestation, ironically through the mediated form of the Internet, as “Unmediated. Experienced directly. In the end there is no audience, just participants. These bands do not just play for the people; they play among the people and actively invite them to join the fun.”23 Indeed, HONK! Festivals are ideally participatory, but the experience of watching a screen is, of course, a far more presentational spectator experience. For Thomas Turino, whereas a presentational performance makes a clear distinction between the roles of performers and spectators, participatory performance is based on an “ethos that everyone present can, and, in fact should, participate in the sound and motion of the performance.”24 Nevertheless, organizers aimed to maintain the participatory ethos of the HONK! Festival in the virtual realm in creative ways. Likewise, even though most of the broadcast material was prerecorded and has been left for others to stream on YouTube, organizers sought to create a sense of liveness for those who tuned in.

As described above, HONK!United consisted of eight days of festival programming simulcasted on various social media platforms. These were broken into two-hour weeknight broadcast premiers and longer broadcasts on the weekend, including a continuous twenty-four-hour broadcast stream on Saturday, and it concluded on Sunday with a full day of workshops held over Zoom. All twenty-two HONK! Festivals, as well as individual bands and even individual HONK! musicians, were invited to submit content or propose ideas for workshops or other interactive events. Bands first submitted Festival content to the HONK!United Organizing Committee, and then a technical subcommittee composed of a handful of volunteers from across the United States curated and organized these submissions into broadcast segments that premiered on social media at a set time each day. Alison Earnhart recruited the members of the technical subcommittee from within the HONK! network based on experience with online broadcasting.

Pre-recorded content included music videos made by individual bands, such as recordings of previous in-person performances and musical demonstrations. Bands also submitted what became known as “COVIDeos,” that is, songs with the individual parts previously recorded in isolation by the members of a given band and mixed together into music videos featuring a collection of Zoom boxes on the screen. Though access to audio and video editing software no doubt played a part in who was able to participate in HONK!United in terms of content creation, easy-to-use apps like Acapella, which exploded in popularity for musicians during the pandemic, required only a smart phone and headphones to record one’s part to a common click track. While lacking the interactivity and urban commotion of an in-person HONK! festival performance, musicians in the COVIDeos often dressed flamboyantly, danced, played with children and pets, and interacted with the camera in order to capture the extravagant energy of HONK!.

A “COVIDeo” of the song “Danza del Guerrero” by Chile’s Banda Rim Bam Bum.

Individual HONK! Festivals in different cities also put together HONK!United submissions showcasing bands from their cities, and they submitted documentaries and “HONK!stories” (an intentional play on the word “history”) explaining the origins of their particular festivals as well as the various social and musical projects on which they focus. Such documentary videos and HONK!stories were submitted by individual bands, activist organizations, and others involved in HONK!.

A short documentary about HONK! São Paulo featured during HONK!United.

The Festival Organizing Committee aimed to create the feeling of “being there” at the festival together, provoking feelings of solidarity, togetherness, and support. Though some tension existed among the committee about how practically, ethically, and aesthetically to best achieve this feeling of co-presence, from those who sought a very professional look to those who prized a more DIY one, nearly all the organizers we interviewed emphasized its importance. Trudi Cohen, a member of the HONK!United Organizing Committee, spoke to the social importance of the virtual festival in the context of extreme precarity and vulnerability for all involved:

I think for bands that we already know and festivals that we already know, affirming the connections that we feel with each other, the sense that … street band music can change the world, and that things are getting worse and worse but there’s a hope for something positive in the struggles that we’re all having for social justice—like that sense of community or being part of the same mission—I think it was really important to reinforce it at this moment…. And I think the more isolated we were this past year, the more we kind of needed that sense that we do have this shared job and pleasure.25

For many HONK!United participants we interviewed, this feeling of co-presence was reinforced by the festival’s aim to promote an experience of liveness. Though much of the content was prerecorded and presented through virtual means, live interaction and participation were facilitated in a variety of ways. Hosting the festival on social media and starting each day’s broadcast stream at a set time allowed participants to watch content together, even if not physically present with one another. The festival interspersed several live segments between prerecorded sections, such as the handful of HONK! bands who chose to play together in person, outside, and physically distanced in their own locales while livestreaming the feed so that those watching around the world could see and hear them performing in real time. Though perhaps the most similar experience to that of an in-person HONK! Festival, these live performances were in the minority, with only six bands performing a short set this way.

Volunteer MCs also acted as live festival hosts, responding to prerecorded content that had just aired and introducing upcoming segments in the festival stream. MCs took two-hour shifts individually or in teams, contributing HONK! anecdotes, covering gaps during technical glitches, and interacting with those assembled in the live chat. Theresa Kadish, a volunteer MC who contributed thoughts to an informal report written by the HONK!United concept committee when they were assessing how much live content to include, suggested that MCs would allow for a feeling of liveness and co-presence appropriate for YouTube and online culture, surmising that:

The world of online video thrives and relies heavily on “react” videos. This kind of content is a big part of what makes the social Internet social. We are bombarded with content, content, content, too much content to actually internalize and sort through. So an entire media ecosystem has emerged of content creators reacting to other content, and building community around that. This live stream will be going for quite some time, and I think properly spaced commentary from MCs can help contextualize the event as a whole and help guide people in feeling socially connected to the content. We want to be encouraging interactivity—a feeling that we are all an audience in this together, even though we are socially distant. Having frequent live reactions to what is being broadcast can go a long way towards contributing to that feeling.

Indeed, how the audience might respond to festival content was a central preoccupation for HONK!United organizers. Those who arranged festival submissions practiced what we call “empathetic programming,” an adaptation of Marié Abe’s concept of “empathetic sounding” to a virtual medium.26 Abe argues that street bands, in her case Japanese chindon-ya, use “imaginative empathy” in producing increased social participation and interaction in performances.27 These street musicians engage potential listeners, who are often those who might be excluded or alienated from participating in social life, and draw them into unexpected social encounters by anticipating their reactions and making musical decisions accordingly. During in-person performances, HONK! musicians often also try to be aware of how their listeners might be affected by their sounds, particularly during political protests or neighborhood parades.

Similar to this in-person empathetic sounding, the festival programming during the twenty-four-hour broadcast stream of HONK!United was organized by time zone to empathetically anticipate the audience’s viewing habits and affective responses. The Saturday twenty-four-hour broadcast constantly changed which festivals or bands were featured from different parts of the world, as organizers had elected not to focus too strongly on any one geographical “block” at one time. However some effort was made to target “primetime” audiences around the world, as the starting time of 6:00 a.m. EST was aimed at European and African viewers, shifting to Brazilian and South American viewers, then North American viewers, and finally Asian and Australian viewers. They anticipated a given audience’s likely familiarity with particular bands, HONK! Festivals, or individuals featured in the videos and livestreams that they would be watching as part of HONK!United. Dylan Foley, a bass drum player and volunteer who worked closely with the technical production subcommittee introduced above, played a large role in the curation of festival content into organized broadcast segments. Drawing on his past experiences helping to prepare the festival performance schedule for the Somerville HONK! Festival and his familiarity with a wide swath of HONK! bands from around the world, he organized streams such that viewers in different parts of the world would witness a mix of familiar and nearby bands with content from festivals or bands from farther away. This balance was meant to keep the attention of viewers who might stop watching if too much or not enough of the content was already familiar, and aimed to facilitate feelings of both global and local connectedness during a time of extreme isolation.

HONK!United volunteer Dylan Foley acts as a live MC during HONK!United.

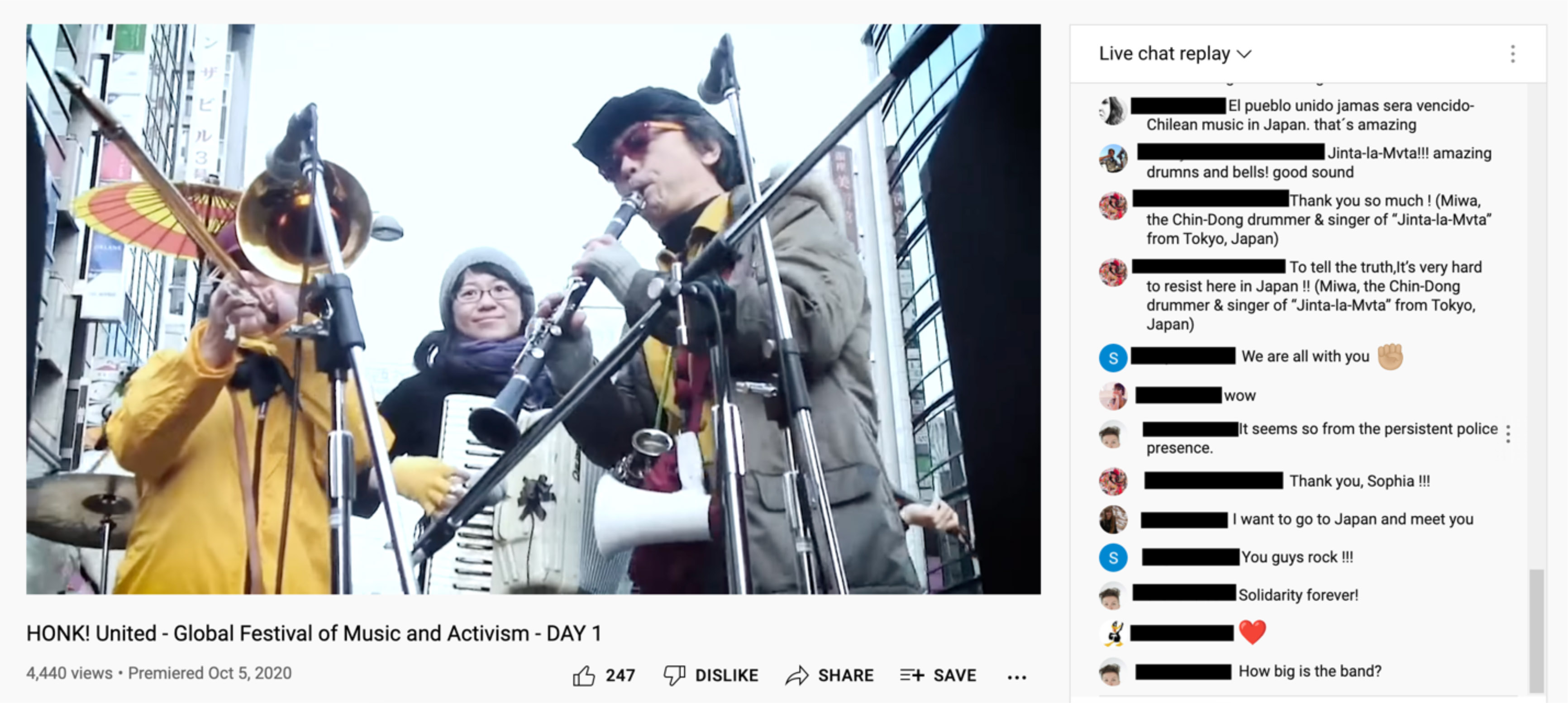

For many viewers, the most salient form of “liveness” in HONK!United was the festival chat stream. Through the live chat function on YouTube, participants were able to react to programming and interact with one another as segments were aired. Festivalgoers gathered in the live chat to show support and appreciation for the creativity in each other’s music videos, often posting clap or fire emojis to indicate that a particular song or video was “lit” or “on fire.” At times, they encouraged dancing or mini-parades in individual kitchens and living rooms. Expressions of solidarity such as raised fist emojis were common during many of the documentary-like segments about the various forms of activist work done by individual HONK! Festivals or bands. HONK! musicians located in different cities and countries greeted each other and collectively reminisced about previous HONK! Festivals. Different languages collided as, for example, Brazilians interacted with each other during a Brazilian HONK! Festival performance, while Americans would recount their memories of having seen a Brazilian band at an American HONK! Festival. Alison Earnhart recounted that, for her, the live chat was representative of the spirit of HONK!United since it was “the big virtual party where everyone was.”28 Organizer Dylan Foley also suggested that the live chat was one way of “maintaining that sense of global community.”29 The simplicity of the live chat section on YouTube appearing right next to the video, rather than on a lesser-known separate group chat app, provided technological accessibility that narrowed the participation gap.

The live chat of HONK!United can be understood as a form of what we call “digital listening”—a mode of online attention and reception that is an active form of participation that engenders feelings of sociality and belonging. Dance and media scholar Alexandra Harlig argues that social audience members on YouTube differ from passive spectators in that they “come together on the page of a given video, where even if they do not produce a response, their sense of belonging to a larger set of viewers is formed through the presence of comments, view counts, and likes.”30 Similarly, communications scholar Kate Crawford, quoting Nick Couldry, argues that listening is reciprocal and embodied, always embedded in an intersubjective space of perception, which is important to the functioning of many online spaces: listeners “actively contribute a mode of receptiveness that encourages others to make public contributions…. They directly contribute to the community by acting as a gathered audience.”31 Thus, the various forms of virtual assembly that HONK!United enabled can be thought of as vital forms of participation, despite the apparently presentational spectacle of consuming media on a screen. While it’s likely that issues of digital inequality impacted those without access to the Internet or streaming technology by preventing them from participating as gathered listeners, other attendees with disabilities who may have had difficulty participating in previous in-person HONK! Festivals were more enabled to be part of the virtual gatherings during HONK!United.

Another mode of assembly that engendered the feeling of “being there together” during HONK!United was the full day of workshops held over Zoom, either as webinars or as meetings. Conversations held during the workshops were akin to in-person conversations in which participants could, for the most part, see, listen, and respond to each other in real time. In the in-person Somerville HONK! Festival, workshops had traditionally taken place after the main weekend events on the following Monday, and organizers had long been dissatisfied by the sidelining of these moments for collective reflection. Unlike the in-person festivals, the online workshops and panels of HONK!United offered, in some ways, more opportunities for participation than consuming online videos of the rest of the festival. HONK!United took advantage of this chance to center and expand these conversations.

Iris Arieli, a percussionist from Israel-Palestine who co-organized and facilitated one of the workshops, pointed to these in-depth conversations as opportunities for participants to share music and ideas with one another as well as provide a glimpse into the histories and everyday realities of HONK! bands in different parts of the world. She found these activities to be particularly impactful in a moment when everyone around the world was experiencing the threat of COVID-19. For Arieli, hearing from others facing similar circumstances gave those who participated in HONK!United the “ability to see longevity, to see how we can keep going during a time when it’s very hard to think about the future.”32

Moreover, for Arieli, whose drumline in Israel-Palestine does not often have much opportunity to see or connect with similar bands, such as those in the United States, Europe, or other places, the virtual forms of assembly of HONK!United provided vital moments of connection and intimacy that were energizing to the continued activist work of her band in Tel Aviv, providing her with new musical and performance ideas. In a time of heightened isolation in a country that she feels is already somewhat isolated from other like-minded musicians and activists, HONK!United reinvigorated a sense of connection and belonging to a broader transnational network collectively facing the precarious situation of the pandemic and other social injustices. Arieli ended our conversation by saying that to her HONK!United felt like “a little slice of something normal and happy and joyous during a time when there is so little of that.” She suggested that virtual gatherings like HONK!United represent something different from the “reactionary” protests in which her band typically participates, instead providing a space to

Resonating with Arieli’s thoughts about HONK!United, Judith Butler argues thatinvest in what you do, so you can do it better, you can enjoy it, and you can remember why you love it…. The thing that helps us keep going is the fact that (a) we’re a community. We are connected to each other, we care about each other, we take care of each other. And (b), we are being challenged … to stay engaged in what we do. And I feel like for me HONK! is definitely that.33

… when bodies assemble on the street, in the square, or in other forms of public space (including virtual ones) they are exercising a plural and performative right to appear, one that asserts and instates the body in the midst of the political field, and which, in its expressive and signifying function, delivers a bodily demand for a more livable set of economic, social, and political conditions no longer afflicted by induced forms of precarity.34

In facilitating a virtual form of assembly, HONK!United affirmed the right to appear without being put at bodily risk of catching COVID-19 or ethical risk of spreading it to others. Affirming the right to a livable life during a year of unprecedented and widespread uncertainty, isolation, and heightened precarity, the HONK!United Festival represented what Judith Butler might see as a mode of sonic and performative assembly signifying persistence and resistance. But while participants appreciated the efforts of those who created HONK!United, praised its diverse programming, and spoke of its ability to make people feel united, no one suggested that it was “as good as” the visceral experience of live music in public space. Trumpeter and social movement scholar Meghan Kallman reflected in one of the panels:

In my band, we’ve had a lot of conversations about what does this moment mean and what can we learn from it. How can we make something just as good? I don’t find a lot of value in saying we are gonna make something just as good—it’s just gonna be online. It’s not just as good. It’s different and there is value in using this forced pause … well and thoughtfully, but to me it has highlighted how much I miss playing music…. I think the grief of missing has taught me as much as any studious reflection about my band, or the community, or whatever.35

Like most physical events translated to virtual media, most participants likely felt similarly that HONK!United was better than nothing but not equal to the in-person festival experience. Arieli’s comments above, by contrast, suggest that the public assembly the festival generated around the world was not simply a replacement for something else (hopefully temporarily) lost, but an experience qualitatively distinct from the pre-pandemic local festivals. It was an event with its own unique impact that will likely have major repercussions on the global HONK! community going forward, especially with regard to the ways that these disparate participating movements sought to “unite” themselves during HONK!United.

A Community Revealing Itself to Itself

As the HONK! network has spread to new places since 2006, it had created plenty of what Anna Tsing calls “frictions” when the HONK! concept encountered new, local settings, but the management of these frictions was mostly limited to local festivals. Nowhere, however, were such frictions more evident than during the virtual HONK!United Festival, when the global HONK! community, until then largely limited to live, ephemeral, and local expressions, suddenly revealed itself to itself. The result of this online experiment has greatly expanded the awareness of global diversity in the HONK! network, turning it into an even more cosmopolitan movement, akin to the advent of online singing in the North American Sacred Harp community during the pandemic, which “reshaped the Sacred Harp community at both the global and local levels … all but eliminating geographical barriers to participation [and], [a]s a result, a new geography of Sacred Harp singing has emerged.”36 But within this new geography of HONK!, real, uncomfortable issues of hierarchy, access, and movement identity emerged in this global format that raised questions of what it is that connects musicians and communities around the world to the HONK! movement.

Until the pandemic, much of the growth of the HONK! Festival network around the globe has been the result of haphazard encounters. Individual bands and musicians might attend a festival in one city as invited musicians and return to their city determined to launch their own event in what has been described as a seed being carried to new soil where it grows in local conditions (a metaphor that resonates with a “family-tree” lineage system of HONK!). The HONK! network in Brazil is, for example, the result of a band from Rio de Janeiro called Os Siderais visiting the Somerville HONK! Festival in 2013. They returned inspired to adapt their preexisting local alternative brass movement, strongly connected to the city’s famous carnival, to this emerging translocal movement.37 As HONK! developed local manifestations, only a minority of local participants, though a considerable one, physically traveled to festivals beyond their region, let alone to other countries.

Festivals developed strong local characters with diverse priorities, motivations, and participation from local communities. Garofalo has compared this process to the “indigenization” of the brass band itself, an ensemble spread around the world by colonial metropoles but transformed by new repertoires and uses in a global variety of local settings.38 Those who did travel made HONK! Festivals translocal affairs from the beginning, and festival organizers convinced locals to open their doors to host traveling musicians. It was a much smaller minority still of participants who truly had a grasp of the global reach and diversity of expressions of the growing network, musicians who had actually traveled to play around the United States, Brazil, Europe, Australia, and elsewhere. This is to say, until HONK!United in 2020, the network had grown in a dispersed and fragmented manner, with the vast majority of participants knowing only parts of whatever whole was being forged.

Yet despite HONK!’s somewhat anti-technological attitudes—as the festivals traditionally embraced live, acoustic, and “un-mediated” music making—organizers readily admit to the role of the Internet and its ubiquity by the 2000s in having facilitated the national and later transnational connections between bands and individuals that emerged into a movement under the HONK! banner. Indeed, the founders of the HONK! Festival in Wollongong, Australia, founded in 2015, had never physically attended a HONK! Festival. They found the event online and were inspired to create their own version dedicated to inclusive music making. The first Somerville Festival itself, organizers recount, was the result of Internet searches and emailing bands that might not have been locatable a decade before. The rise of social media accelerated the forging of connections between the participants from increasingly diverse places around the globe, with pages devoted to individual festivals as well as pan-HONK! pages, such as “HONK! Musicians and Dancers” on Facebook, which increased the visibility of the festivals from afar. While HONK!United was a sudden response to the unprecedented circumstances of the pandemic, one could also view it as a logical extension of the preexisting and increasing use of technology to mediate the translocal encounters of this global network.

For a community as diverse as the global HONK! network to see itself as broadly “united” and connected, some kind of centralized discourse about what HONK! could be conceived to be in so many places has been necessary to construct a common sense of identity. As discussed above, the original HONK! Somerville Festival had largely taken a hands-off approach to the emergence of new festivals, leading to disparate interpretations around the globe, though they had issued a statement about some broad general principles, as mentioned above. For the creation of HONK!United, the Somerville Organizing Committee, which had become the HONK!United Organizing Committee, released a statement that was placed on the festival’s website and recorded by the festival organizers reading it aloud. This recording was broadcast before every HONK!United broadcast segment, serving as a frequently appearing statement of rationale and collective identity. We suggest that this statement offered what Tsing might call a “universal” statement about HONK! around the world that would be reinterpreted by the “particular” bands, festivals, and locales that participated in the virtual festival. What Tsing calls the resulting “friction” when universals rub against particulars indicates the processes of hybridization, points of tension, and even discord as universals meet particulars, as well as the generative and diverse juxtapositions and conversations between groups from so many different places. We cite at length sections of what we are calling this “universal” statement that was frequently broadcast during HONK!United:

For the past 15 years, an October weekend has been the moment when thousands of participants from the Greater Boston area in the USA have enjoyed the HONK! Festival of Activist Street Bands—a raucous celebration of music and community that took Somerville, Massachusetts by storm in 2006.

Since that original HONK!, the idea has caught fire beyond anyone’s wildest expectations. HONK! is now a global phenomenon, with more than 20 HONK! Festivals worldwide and participating bands joining us from all seven continents….

Until this year, all these individual HONK!s have been held throughout the calendar year, forming an international network that has fostered profound artistic, political, and cultural exchanges among participating bands, local hosts and volunteers, community partners and people gathered in the streets….

Although the pandemic has made both intimate and spectacular gatherings impossible, we did not want to let a year go by without honoring and activating the HONK! spirit, especially in these times when it is urgent to fight for social justice and to renew our lives with the joy of music and art. Even though we can’t all gather in one place this year, we can make a statement at the same time.

The virtual space of the Internet allows us to reach across time and space to be more expansive than ever before. HONK!, after all, is not tied to any particular location. HONK! is where you make it. It is an idea. It is a practice. It is a commitment to using the power of brass and percussion to encourage inclusionary practices, engage in participatory music-making, reclaim public spaces, build community, fight for social justice and, ultimately, help make the world a better place.

So, this year, we invited every HONK! affiliate out there—organizers, musicians, artists, and activist partners—to contribute content to HONK!United…. Imagine being able to celebrate the power of brass and percussion from Boston to Benin, Rio to Rome and Paris, London to Wollongong, not to mention Austin, New York, Seattle, Pittsburgh, New Orleans, Montreal, Vancouver, and elsewhere … all at the same time. This is what we are offering….

We … hope to tell the stories of the HONK! movement from the founding of bands and festivals to the present day.

We also asked contributors to shine a light on conditions on the ground in their communities regarding: COVID; the Black Lives Matter movement; immigration, housing and economic justice; and the climate crisis. Whatever is relevant to their bands, their festivals, their organizations, their communities.

Then we invited the world to attend.

Each festival, of course, has its own unique character based on its historical context, cultural traditions, and musical styles, but they are united with others through a shared commitment to practices that transcend local boundaries. It’s not just the participatory music-making in the street; it’s also the unorthodox performance styles, the outrageous costumes, the progressive political spirit, the genuine camaraderie, and the sheer spectacle of it all.

Together we are HONK!United.39

There are a number of things to point out about this statement that show frictions between a universalist discourse and linear, family-tree depiction of the movement’s growth on the one hand, and a rhizomatic map of particular interpretations on the other. On the universalist and Somerville-centric side, the statement is read by the Somerville Organizing Committee, rather than, for example, representatives of different HONK! Festivals around the globe. It begins by recounting a story of emergence that begins in Somerville in 2006 and grows outward, having “caught fire.” As the statement mentions, the HONK!United Festival was scheduled to take place during Somerville’s normally scheduled Festival in early October, which impressed an importance of those dates not only to Somerville, but to the broader movement.

Following the global hegemony of the English language, the statement is read in English, which is treated as a lingua franca, as it often is around the globe, with no translation to one of the many languages used by other participants worldwide. While these organizers might be familiar faces for those who attend HONK! Somerville, for the many HONK! participants around the world accustomed to the statements and language of their own local festivals, the segment might appear quite foreign, even incomprehensible depending on language capacity. All this has the effect of reasserting the centrality of Somerville both within the movement’s history and in the organization of the online event, and, by extension, an Anglo, North-American dominance within the global movement.

At the same time, HONK! is portrayed as an “idea” and “practice” not tied to any particular place, one that fosters exchanges and connects cities from around the world directly to one another rhizomatically, and not only through the “family root” of Somerville. Festivals around the world are depicted not as adaptations of Somerville but as having their own unique characters, rooted in their own traditions. Bands are asked to use music to shine a light on the social and political concerns and movements within their local communities. HONK!United is framed as an opportunity for localized storytelling with the contribution of self-representing documentaries and “HONK!stories” that would enable participants to learn about the diversity of the phenomenon around the world.

Lastly, the focus on defining the HONK! movement in reference to its espousal of activism, as seen in reference to progressive politics and supporting diverse social movements, is notable. As noted earlier, Somerville’s explicit commitment to activism in the very name of the original HONK! Festival of Activist Street Bands has long been a subject of controversy within that festival. Somerville organizers have resisted the creation of absolute definitions or guidelines about how musical activism might manifest itself in the HONK! community. But the term itself was mostly discarded as new festivals brought the HONK! concept to other places, with the exception of Brazil, in favor of “less controversial” interpretations of the event. Austin adapted the name to HONK!TX Festival of Community Bands, and other HONK! Festivals simply highlighted their locality like Seattle’s HONK! Fest West. In other words, HONK!United frontloaded Somerville’s conception of activism in a way that challenged the apolitical rationales of other HONK! Festivals. At the same time, the forum of an online, insider-event festival allowed bands and festivals sympathetic with Somerville’s activist framing but wary of inviting controversy in their more conservative environments to be more open about their own politics.

We note Somerville’s centrality in creating and framing HONK!United as a friendly critique as well as an acknowledgement of the great undertaking that was involved in creating the virtual Festival. The organizers were responding quickly to uncertain and changing circumstances, working to create an event that would either happen if they put in the effort or likely not at all. In our interviews with the HONK!United organizers, they suggested that they aimed to assert leadership but not control, curating but not defining the work of others and retaining the horizontal spirit of HONK!. Somerville is aware of the contradictions, hierarchies, and homogenization that might emerge if a global movement that has defined itself as open to local manifestations and rejecting dogmatic definitions became more largely defined by New Englanders. As Somerville and HONK!United organizer Matt Taylor reflected after the festival,

Though it is currently unclear if something like a virtual HONK!United Festival will occur again in some future manifestation, festival organizers suggested that the structure and personnel of a future HONK!United Organizing Committee could shift away from its Somerville-centric first iteration to a more transnational direction. A global committee that meets virtually might form, or the task of planning the online festival might rotate to other local festivals around the world. The HONK! network cannot itself, of course, alter fundamental structural aspects of global hegemonies, such as the likely dominance of English in any version of a global festival. But there are ways to put the means of production of a festival of diverse transnational expressions into more transnational hands with more diverse languages.What I’m afraid of happening is more uniformity, more people looking to the Somerville committee as the guide for what needs to happen for what HONK! should look like. I don’t think any of us want any sort of gatekeeping…. And because [the global community] was revealed to itself through the lens of the HONK! Somerville committee, it’s really important that it not continue to be through that lens if HONK!United continues to exist.40

Another aspect of the irreconcilability of “universal and particular” is apparent when trying to make any global statement about what the bands that took part in HONK!United share in common. For any attempt to impose a rule, one could find an exception. Many definitions of HONK! have noted the amateur, accessible, and multi-level composition of many bands,41 but professional, world-touring bands, such as Chile’s Rim Bam Bum, Benin’s Gangbé, and Brazil’s Bagunço, complicate any definition of HONK! as amateur. As noted above, HONK!United put Somerville’s adherence to activism front and center, but this is an affiliation many bands and festivals had intentionally deemphasized, and many, if not most, contributions to the online festival were simply performances that one would stretch to call clearly activist. Many bands, including some formed by all women and nonbinary musicians, openly promote feminism in the HONK! movement, while in a workshop with a New Orleans band, discussants noted the preponderance of patriarchy within the second line scene. Even with the predominance of acoustic brass and percussion ensembles, one could find other ensemble formations, including electronic instruments and percussion with voice.

The Sunday day of workshops included a wide variety of events, many of which explicitly aimed to foster dialogue on challenging issues, including a workshop on risk management in intense police situations and during the pandemic; a conversation with the authors of our recent book about the HONK! movement42; and hosted conversations with bands and participants from Brazil, Chile, Japan, New Orleans, Benin, and Uganda, with translators when not in English. During these encounters one could witness not only frictions, but outright disagreement on a variety of issues. For some participants, such discords were perhaps surprising and possibly tugged at the very unitedness the virtual Festival projected. One workshop discussion that focused on inclusion and diversity at the Somerville Festival highlighted the negative implication of the word “friction.” It presented substantial criticisms of the festival’s shortcomings, contradictions, and activist pretensions, such as partnerships with business organizations at a noncommercial event, the use of police at parades supporting Black Lives Matter, and ongoing limits of demographic diversification. This workshop was, in fact, not archived on YouTube per the participants’ wishes.

In the transnational conversations, participants did make unifying comparisons between their local situations and those of others. Several Brazilian musicians, for example, noted parallels between the challenges their bands faced under Jair Bolsonaro and the conditions in the US under Donald Trump and the ways music was used at protests. However, ethnomusicologist Sarah Politz, who hosted a conversation with bands from Sub-Saharan Africa at HONK!United, has pointed to the radically different possibilities of political engagement for a band such as Benin’s Gangbé, who participated in HONK!United: “Musicians may or may not have the privileges of security, freedom of expression, and economic stability to levy social critique against state power from below, and for a variety of reasons they may or may not choose to exercise the agency they do have.”43 Politz shows how despite the different priorities of a professional African touring band, Gangbé expresses critique in more coded ways than those generally imagined by HONK! bands in the West.

HONK!United points, therefore, both to the continuing importance of linear and universal narratives of the movement as well as disparate, rhizomatic, and diverse ones. We conclude that it is this dynamic element of E Pluribus Unum (unity in diversity) of the movement that helps it grow and thrive, and that was a particularly engaging element of the virtual festival. Though we have already pointed to HONK!United’s risks of increasing uniformity, not all uniformity is necessarily undesirable, at least from the perspective of those who want HONK! to retain some principles as it grows around the world. Organizer Matt Taylor reflected, “Take the conversation around activism itself, being controversial in the network and lots of Festivals dropping it, and then HONK!United comes in and very much frontloads activism, which is not bad, I would say. If the thing that we become uniform on is pushing for social justice, I’m not going to complain.”44 On the possibilities for more diversity going forward, Taylor likewise suggested the “positives are limitless,” asking,

Where does [HONK!United] create opportunity for more intentional relationship building that didn’t happen already because people are now more aware of discovering each other and discovering connections they couldn’t have before because their bands didn’t go to the same Festivals … in a way that was previously unseen because of the local and decentralized nature of it all? What does [HONK!United] mean for musical influence and interpretation, performative influence and interpretation, and learning from each other? What does it mean in terms of discovering and connecting with community groups and having music be more a part of activism [in different places]?45

We have highlighted the frictions that are inevitable when a worldwide movement that has largely rejected strict guidelines suddenly comes to know itself more intimately. However, as Tsing reminds us, “There is no reason to assume that collaborators share common goals. In transnational collaborations, overlapping but discrepant forms of cosmopolitanism may inform contributors, allowing them to converse—but across difference.”46 Elsewhere, Erin Allen has characterized the HONK! movement as what Chantal Mouffe calls “agonistic,”47 rather than antagonistic, which encompasses the potentially positive aspects of conflict and which Mouffe argues is a fundamental feature of a functioning democracy. While the unitedness of HONK!United might be vague, participants who do not feel united can, after all, simply leave the conversation, and participants who don’t actually fit can be de-platformed by an organizing committee. The frictions that arise with constructing any festival, let alone a global one that values horizontalism, come with the territory, and HONK!United is not expected to simply resolve them. Rather, it provides a forum for generative dialogue that will no doubt reverberate in the physical manifestations of the festivals around the world in the years going forward, further feeding back into the consciousness of the global community.

Impacts of HONK!United on the Global HONK! Community

The online forum of the virtual festival provided for HONK! participants around the world a suddenly curated window onto a diverse array of movements that had in previous years come to define themselves under the HONK! banner. This unprecedented knowledge of Others around the world in solidarity with one another that resulted cannot but fundamentally transform the HONK! movement and the bands that latch themselves onto it going forward. As Taylor points out, participants have been bequeathed a new awareness of repertoires to play, places to visit, performance practices to try, and political conversations to have. Never again will the local HONK! Festivals be defined so strongly by their local manifestations, innocently unaware of much of the rest of the global community. Unlike the intervention on public space of the in-person festivals that draw in unwitting spectators and transform them into full participants, the online event was attended by a limited number of people around the world and was to some extent an “insider event.” But it was precisely many of those insiders who attended the virtual festival who were most motivated to contribute to and influence their own, local, in-person events.

Indeed, the HONK!United Festival was not simply a representation of the global community but an event that has the capacity to shape it going forward. The involvement of African bands in the virtual festival, from a continent in which there had never before been an in-person local HONK! Festival, is a concrete example of the impact of the virtual on the physical. We authors of the collected volume about the HONK! movement had included an article about Benin’s professional Gangbé brass band by ethnomusicologist Sarah Politz, who herself had experience with Somerville’s HONK! as a trombonist and graduate student at Harvard.48 She contributed the chapter cited above about the Beninois band’s conceptions of musical activism in relation to the HONK! movement. Although Gangbé had never attended a HONK! Festival and was a musical reference known and covered by only a few musicians and bands in the HONK! community, we editors believed the chapter offered an important critique about the challenges of exporting North American conceptions of musical activism around the world. To our surprise, however, the contact with Politz led to the participation of Gangbé in HONK!United itself.

Likewise, one of the highlights of the festival came from Uganda with a submission from the Elgon Youth Brass Band, which has since 2009 used music to help organize marginalized children in their “Saved by Music Foundation.” In the video the group sent to HONK!United, they prominently featured the HONK!United logo on a banner they had printed. HONK! Somerville has since received word that the Ugandan group expects to hold its own in-person HONK! Festival as soon as the pandemic is over. On HONK!United’s day of workshops, Sarah Politz hosted a conversation with representatives of Beninois and Ugandan bands, in French and English with a translator, about the unique histories of brass in the African continent. The virtual encounter will hopefully lead HONK! to becoming an ever more diverse movement that continues to destabilize the movement’s origins as a middle-class, Northeastern, and predominantly white festival.

Screenshot of Elgon Youth Brass Band During HONK!United.

Uganda’s ElgonYouth Brass Band Participates in HONK!United.

Closer to Somerville, Philadelphia held its first in-person HONK! festival in 2021 after a submission about a brass band supporting Black Lives Matter protests in 2020 in the city aired on PBS and was rebroadcast during HONK!United. In the case of Somerville itself, an in-person festival was held in October, 2021 as the COVID-19 Delta variant surge began to fade in the US. However, in order to prevent large, packed crowds, the festival opted for smaller events spread around the city in alliance with local social justice organizations. In this way, the disruption of the pandemic allowed the original festival to move closer to its activist missions of supporting diverse community struggles rather than prioritizing mass performance centralized in Somerville and Cambridge. The 2021 event was unusually hyper-local for an in-person HONK!, as the festival had requested that out-of-town HONK! musicians not travel to the festival in order to limit the possibility for the COVID-19 contagion to spread.