The COVID-19 crisis presented unprecedented challenges for libraries, library users, and vendors. Even at the onset of the pandemic, it was clear that the crisis would have a significant impact on teaching and learning at colleges as well as on academic library services and collection development approaches. By mid to late March 2020, most colleges and universities switched their course delivery to an entirely on-line format so that the campus communities could practice social distancing as recommended by national and global health agencies. This rapid change required academic libraries to quickly shift their collection development foci toward mostly electronic purchases in an effort to support their students with e-textbook needs.

While students from wealthier backgrounds might transition to the online courses smoothly, underprivileged students might not have stable Internet access or a quiet study environment at home. Those students who routinely came to physical libraries to borrow print textbooks for a short-term loan through course reserves could no longer do so when the library facilities were closed due to the pandemic. Although the services offered through VitalSource and similar businesses provided a relief by offering seven free e-textbooks per student, there was much uncertainty because those services ended on May 25, 2020 (see, e.g., VitalSource, 2020). Academic libraries were suddenly expected to fill this gap by providing what was immediately needed for students’ learning including e-textbooks, which were not routinely supported through libraries beyond mostly in-person course reserves. This meant that libraries had to shift their spends toward more e-books and e-textbooks while containing costs in areas such as print monographs and journals as well as negotiating cost increases for renewals.

The International Coalition of Library Consortia (ICOLC) was quick in their response to the Global COVID-19 Pandemic. ICOLC (2020, March 13) published a statement directed to publishers and other content providers to describe the challenges that consortia and libraries were facing as well as to suggest approaches that might help both libraries and vendors. This ICOLC statement, other efforts, and vendors’ own initiatives led to numerous free vendor offers. These offers were temporary and created new opportunities and challenges for libraries. These offers were different from the ones that were directly sent to students and faculty, e.g., VitalSource free e-textbooks, in that they normally required institutional subscriptions. It is common for vendors to grant a free trial access to their products for up to 30 days. Libraries typically evaluate the pros and cons of these free trials before accepting such offers. The COVID-19 situation required libraries to respond to those offers more quickly, while being mindful of the fact that their students and researchers desperately needed more electronic access to information resources.

At Penn State University Libraries (PSUL) where the author works, the situation was the same as many other academic libraries. The students and faculty lost access to the libraries’ print collections as of March 20 and became dependent on remotely accessible electronic content offered through the Penn State Libraries’ websites. Requests for e-books were overwhelming during the first two weeks after the library building closure. The Acquisitions Services unit ordered approximately 1,000 e-books in late March to support students and faculty who were teaching and learning remotely. Additionally, PSUL accepted selected free offers during this chaotic period. This article examines the free vendor offers during the COVID-19 crisis, presents a case study of PSUL business decisions on those free offers, and demonstrates a cost and benefit analysis of those free offers in order for libraries and vendors to make better decisions on future free offers and come up with win-win scenarios. In this article, the term “free” is used to indicate that the resource itself has no cost.

Literature Review

In the library and information science literature, trials to electronic databases emerge as a topic that is often discussed in relation to the electronic resource life cycle and best practices. Bhatt (2015) discusses lessons learned from years of coordinating trials for electronic resources and identifies common pitfalls. Some of those common pitfalls include an abundance of simultaneous trials, lack of established processes for gathering feedback, and lack of mechanisms for documenting trial history. Like Bhatt, Pionke (2015) recognizes the challenges inherent in gathering feedback on trials and makes a case for using community organizing techniques to address these challenges. Emanuel (2013) describes the use of screencasting to promote database trials and draw attention to features that may be of interest to library users. While the literature in library and information science offers advice for managing and publicizing trials, it does not offer a great deal of information on determining value.

Most existing studies that explore the value of free offers or free trials and the drive behind offering them have been published in marketing and decision science publications. Robert Cialdini, a leading social scientist in the field of influence, described six principles of persuasion: reciprocity, consistency, social proof or consensus, liking, authority, and scarcity, and argued that free samples “can engage the reciprocity rule” and “can release the natural indebting force inherent in a gift” (2001, p. 27). At the same time, it is not easy to retain the customers acquired with free trials. Datta et al. (2015) used household panel data from a digital television service and found that marketing communication and usage behavior drove free-trial customers’ retention decisions, which suggests that service providers could use direct marketing to communicate the usage patterns and encourage more usage, thus securing the relevance of the service.

Businesses find benefits in free trials and services in different ways. For example, Li and Yi (2017) studied software and video game firms’ free trials and found that a trial may enable the seller to segment the market and charge a higher price to high-valuation buyers, although free trials can also cause a decline in demand. Ajorlou et al. (2018) found that, while both buyers and non-buyers contribute to information diffusion, buyers are more likely to spread the news about the product and suggested that companies use free offers, as seen in the smartphone app market, to attract low-valuation customers and to get them more engaged in the information spread so that they can reach potential high-valuation consumers in parts of the social network that would otherwise remain untouched without the price drops. Furthermore, Chen et al. (2017) analyzed software free sampling on CNET Download.com (CNETD), word of mouth (WOM) on Amazon.com, and sales on Amazon.com over a 25-week data set and found that more adoptions of CNETD free sampling led to a larger volume of Amazon WOM, and this impact was more significant for less popular products.

Estimating the worth of free customers is a challenging task for businesses. Gupta and Mela (2008) argued that managers tend to underestimate free customers’ significance for two reasons: first, they naturally focus more on paying customers, and second, they lack a method for calculating the lifetime value of free customers, and presented a model that estimates the long-term impact of each additional free customer on a company’s profits, considering the degree to which the customer brings in other customers and the ripple effect of those customers.

Existing research also suggests that quality and completeness of free offers affect customer retention. For example, Li and Yi (2017) found that, if the free trial deviates from the true nature of the full product, buyers may feel “cheated” by the trial provider, which might lead to a negative image of the brand and less likelihood of customer retention beyond the free period. Additionally, Li et al. (2019) examined how quality and other design factors of the free sample affect profit generated by the product or service in the context of a book publisher that provides free samples for the books it sells online and found that free samples of the entire content, instead of partial samples, can be very effective in increasing revenues. They also found higher-quality samples have a greater impact on the sales of popular content.

Additionally, customers are generally just as likely to accept pseudo-free offers, i.e. offers that are free but require them to make nonmonetary payment, such as completing a survey or providing personal information. Customers view these offers as free as long as the costs of the pseudo-free offers are below some threshold and are more likely to accept pseudo-free offers than comparable non-free offers. Dallas and Morwitz (2018) provided evidence that consumers respond to pseudo-free offers, e.g. free Wi-Fi, Gmail, Facebook, etc. that require personal information, in this way because, in general, consumers perceive the pseudo-free offers as fair.

Free trials are not risk free. For example, Foubert and Gijsbrechts (2016) analyzed the data set that incorporated customers’ trial subscription, adoption, and usage behavior for an interactive digital television service. They found that free trials constitute a double-edged sword in that they can generate new paying subscribers by allowing customers to become acquainted with the product for free, or can alienate potential customers if their trial experience is disappointing especially in early periods when quality has not been ‘tried and tested’. Based on this observation, they argued that timing of free trials, i.e. offering only fully developed products, and consumers’ usage intensity during the trial are key to the effectiveness of these promotions.

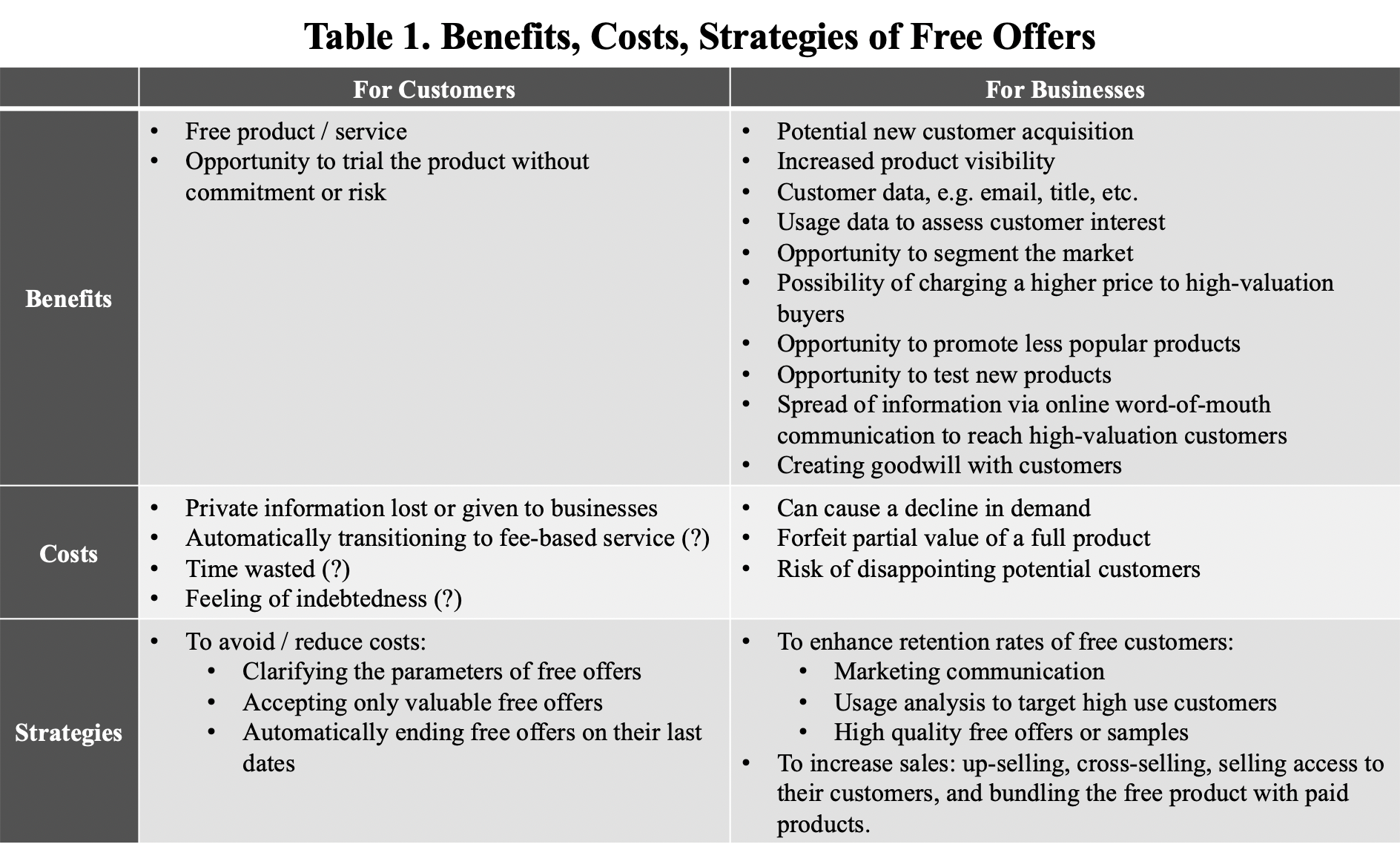

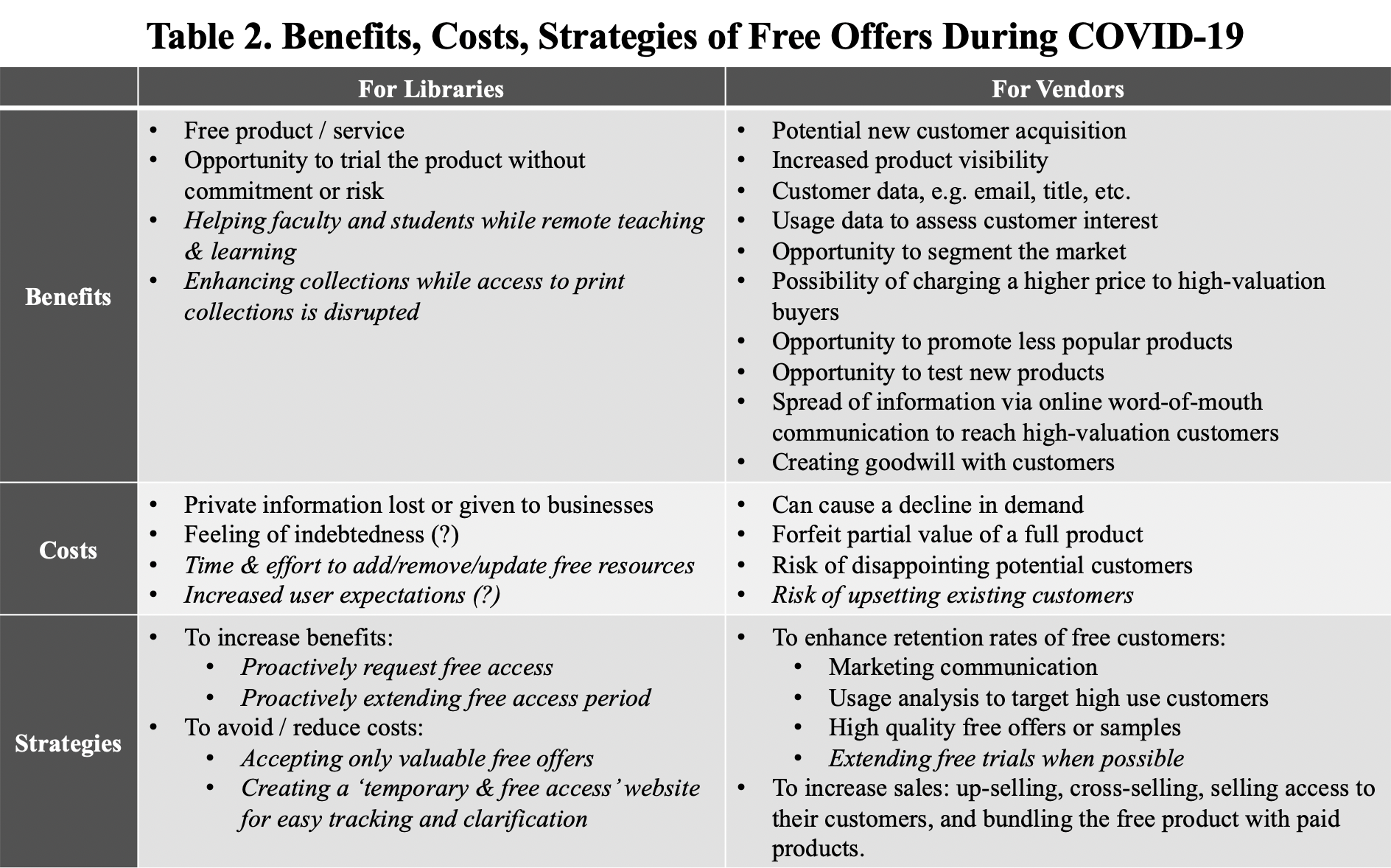

Bryce et al. (2011) acknowledged embracing free strategies is not easy for established businesses due to the profit-center structure and the cost accounting system. They suggested that they fend off their competitors’ free offers by introducing a better free product, generating revenues and profits through up-selling or cross-selling, charging third parties or selling access to their customers, and bundling the free offer with paid services. Table 1 summarizes the benefits, costs, and strategies of free offers for customers and businesses based on the literature review.

Free offers provide many benefits for businesses that might not be apparent to customers, as Table 1 shows. There are strategies to increase benefits and decrease costs for both customers and businesses. Much of the existing literature suggested that it would be beneficial for businesses to offer high-quality free trials, track usage of those offers, and communicate the usage, if it is high, with the customer. Customers could save cost and avoid any confusion by accepting only free offers they need and clarifying that those offers are temporary.

While the existing business literature is helpful in understanding the value and strategies related to free offers in general, research focused on libraries and library vendors’ free offers is lacking. Hence, this study will examine recent free offers during the COVID-19 pandemic, analyze a research library’s business decisions on those offers, and evaluate the outcome through a cost benefit analysis in order to make suggestions to increase value of free offers for both libraries and vendors.

Objectives

This study involves a systematic review of free vendor offers during the COVID-19 crisis and a case study of PSUL business decisions on those offers to answer the following questions:

What free offers were made for academic libraries during COVID-19?

What free offers were accepted by PSUL?

What are the benefits, costs, and strategies of free offers for academic libraries and vendors, and what can libraries and vendors do to increase the value of the free offers?

A cost benefit analysis is performed based on the understanding that value is created when benefits are larger than costs (Anderson & Narus, 1998). Therefore, to create value, we can either increase the benefits, or decrease the costs, or do both at the same time. In this study, the benefits, the costs, and the value are all intangible, i.e., not measurable through cost-per-use data analysis because free offers do not involve explicit monetary value.

Methods

To identify a wide range of free offers for academic libraries, the author monitored the following from March 1, 2020 through May 31, 2020: direct offers from vendors, LIBLICENSE-L@LISTSERV.CRL.EDU, information obtained from peers, and the ICOLC COVID19 Complimentary Expanded Access Specifics Google Docs (International Coalition of Library Consortia, 2020). Sometimes information was duplicated; however, this multi-channel approach ensured that the author was aware of a variety of free offers. The following was recorded for the purpose of this study: the date of the offer, the provider, the resource name, the URL of the announcement if any, the type of the resource, registration requirement, the effective through date, extension of the free offer if any, and PSUL decisions.

The following free offers were excluded from this study because the purpose of this study is to evaluate the free electronic resource offers that would normally require paid subscriptions through libraries: offers for individual faculty members and students, e.g. VitalSource, RedShelf, free digital inspection copies; discounts; upgrades, e.g. unlimited access; webinars and workshops; OA or resources that are always free to read, e.g. COVID-19 specific research that was published as OA; free print samples; and expansion of remote access capabilities and other free technical enhancement. Additionally, offers that couldn’t be confirmed through vendors or on their websites were also eliminated.

Findings

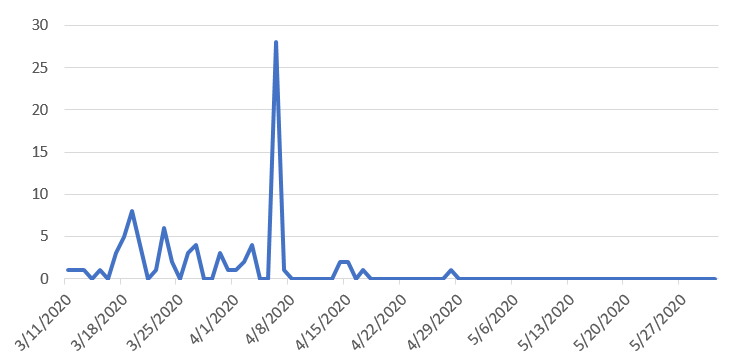

During the three-month period, total 86 free offers that met the criteria were received. Some of the offers were directly relevant to business librarians: EBSCO Harvard Business Publishing Collection, SAGE video, Bloomberg Businessweek Archive: 1929–2000, Business Periodicals Index Retrospective: 1913–1982, Forbes Magazine Archive: 1917–2000, and Fortune Magazine Archive: 1930–2000. Many others also seemed useful for researchers interested in business topics. See Appendix for details. Most of the offers were provided in late March and early April 2020, as Figure 1 shows. The spike on April 8 is partly due to a vendor offer that involved a large number of database products. After mid-April 2020, not many new free offers were provided.

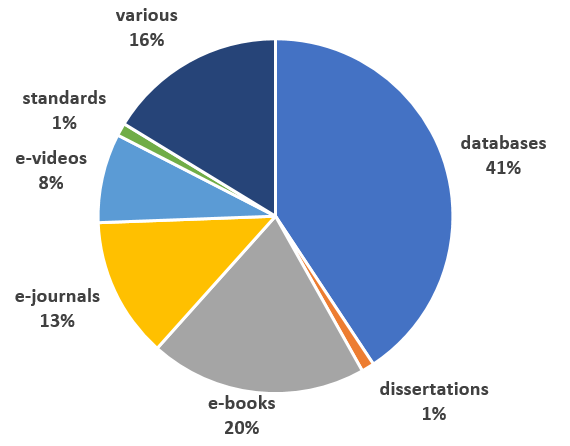

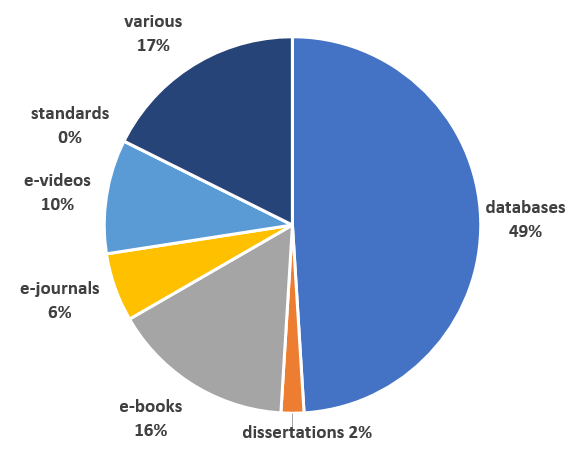

The offer type varied, as shown in Figure 2. This was unexpected, as the author believes that most academic libraries were hoping to add more e-books while access to the print collections was disrupted. At the same time, this supports the literature review findings that businesses sometimes provide free offers to promote less popular products or to test new products. Databases were the largest offer category with total 35 free offers (41%), followed-by e-books with total 17 offers (20%). Additionally, 14 offers (16%) included a variety of products such as a mix of e-videos and e-journals and are labeled “various” in Figure 2.

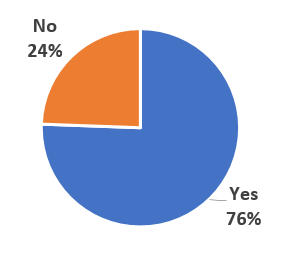

Seventy-six percent (65 offers) required registration by library representatives, as Figure 3 shows. Registration allows vendors to track usage and protect themselves from unauthorized downloads and criminal activities. While these offers are free to the customers, i.e. libraries, the vendors benefit by gathering usage data and identifying high-value customers whom they might be able to retain after the free period, as marketing literature suggested. At the same time, the fact that 24% or 21 offers did not require registration might indicate that the vendors were more interested in supporting libraries during the challenging COVID-19 period and building goodwill for potential long-term benefits rather than rushing to lead those free offers to immediate sale of those products. Considering that these are resources that normally require subscription fees, it is significant that almost one quarter of these offers did not require registration. Nevertheless, a careful examination revealed that five of the 21 offers that did not require registration were provided on the platforms on which PSUL already had active subscriptions. Therefore, those free offers were trackable in terms of usage analysis.

The length of free access varied between 30 days and 287 days as of May 31, 2020, with the average of 97 days. Eight offers did not specify end dates. Initially many of the free offers were for the Spring 2020 semester only. As the COVID-19 crisis prolonged, some vendors extended their free offer’s end dates which was very much appreciated by library users. As of May 31, 2020, total 24 out of 86 offers (28%) extended the length of free access. One of them was extended because a PSUL librarian requested the extension to support ongoing needs for some courses. It is possible that other offers might also be extended if requested.

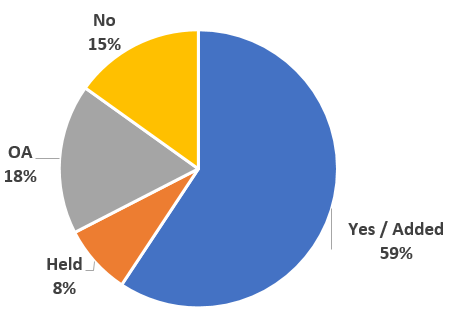

PSUL accepted 59% (51 out of 86) of the free offers, as Figure 4 shows. Additionally, 18% or 15 offers were provided with open access (OA) during the pandemic, although they would normally require subscription fees and registration. OA in this study means free, immediate, and online availability of the content. Furthermore, 8% or seven resources were already held at PSUL. The fact that only a small portion of these free offers was already held at PSUL might indicate that most of the offers were either new, not high-priority or not affordable for PSUL. Combined these three categories (yes/added, OA, and held) together, 85% (73 out of 86) of the free offers became available to PSUL. The rest of the offers, consisting of 15% or 13 offers, were not accepted because they were not requested by library users or did not meet the parameters of this project, e.g., not related to research & teaching at PSUL, technical challenges, etc. Due to the increased workload during the pandemic, the Acquisitions unit added resources when the benefits for users outweighed the costs such as staff efforts and technical issues.

PSUL decisions were made based on local teaching and research needs at The Pennsylvania State University, as well as other considerations such as technical issues and staff time. In terms of the resource type, the largest category involved databases, with total 25 additions (49%) as Figure 5 shows. Explicit interest from faculty, students, and library staff suggests that these resources have potential to become paid subscriptions if the free access meets or exceeds the requestor’s expectations and if funding becomes available.

Acquisitions Services received suggestions and requests for free offers and accepted them as long as they did not cause technical or maintenance challenges. Additionally, the Acquisitions unit worked with the libraries’ Web team to create a special website for these free offers, so that the parameters for those additions were clarified. The introductory text reads as follows: “In an effort to respond to the increased need for electronic content to support teaching and research, the University Libraries is taking advantage of select offers from vendors and publishers for free temporary access to resources due to COVID-19. The following resources have been added to library collections on a temporary basis” (The Pennsylvania State University, 2020). PSUL focused on helping end users in a timely manner. Paid subscriptions and usage analysis were not considered for emergency and temporary access to free resources during the pandemic. Therefore, the value achieved by PSUL was intangible with no explicit monetary value, requiring different analysis than typical cost-per-use data analysis to assess the value of free offers.

Discussion

Although PSUL accepted 59% (51out of 86) of free offers during the initial three months of the pandemic, it was also mindful of the time and effort required to add and update those resources through PSUL websites, catalog, electronic resource management system, etc. PSUL’s decisions were based on coursework and research needs and were dependent on user and librarian inquiries and requests. The vendors’ offers to extend the free periods were greatly appreciated when libraries were facing not only the COVID-19 remote teaching & learning transition but also budgetary issues. In fact, only three vendors suggested paid subscriptions at the end of May 2020.

As discussed earlier, value is created when benefits outweigh costs. In this study of free offers, both benefits and costs are intangible. The offers were temporary and for short periods and did not have explicit monetary value. PSUL employees were focused on helping students and faculty in a timely manner and added requested resources as long as there were no technical and other constraint. In other words, resources were added regardless of expected usage whenever the perceived benefits for library users outweighed the perceived costs involved in adding those free resources. The value created for PSUL was therefore also intangible with no explicit monetary value and yet positive based on user feedback.

Nevertheless, during the three-month period of this study, between March and May 2020, it appears that both PSUL and the vendors generated additional value as shown in Table 2. The italic font indicates unique observations during this study. PSUL increased the value of the free offers by proactively requesting free access to resources that were not automatically provided for free and by proactively asking for free period extension, while accepting only free offers they need and listing those offers on a separate website for temporary resources. The vendors increased value of the free offers by increasing visibility of those products through extended free offers, while establishing goodwill with customers and protecting their revenue from core resources. Many organizations, including the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL), the Association of Research Libraries (ARL), and the Oberlin Group of Libraries, requested continuation of free access during the COVID-19 pandemic (Aiwuyor, 2020). Vendors will hopefully realize that free offers provide benefits not just for libraries but also for vendors and consider extending the length of free periods, especially during challenging times.

Limitations

The main limitation of this study is that only three-month period, from March 1 through May 31, 2020, was observed for data gathering purposes. At the same time, as the data shows, the peak of these offers was in late March through early April 2020. Another limitation is that the data gathering was done manually by observing mailing list posts, the ICOLC vendor free offer document, and word of mouth. It is possible that there were other free offers provided through other channels. The goal of this study is to find key value drivers for academic libraries and vendors through free offers to guide their future actions on these offers, and the author believes adequate data was identified. Finally, this study does not discuss future purchasing patterns of PSUL related to the accepted free offers. While this data would demonstrate possible increased value for the vendors, it seems challenging to attribute future paid subscriptions solely to these free offers. Many universities, including Penn State, are experiencing extraordinary financial challenges due to the pandemic, and immediate purchases might be challenging even if free offers resulted in increased interest in those products.

Conclusion

Academic libraries received numerous free offers during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in late March and early April 2020. About 28% of the free offers’ access period was extended by vendors as the pandemic prolonged. As of May 31, 2020, the length of free access varied between 30 days and 287 days, with the average of 97 days. Databases were the largest offer category (41%), followed-by e-books (20%). Most (76%) required registration by library representatives, allowing vendors to track usage data. PSUL accepted 59% of the free offers. Combined together with the content that became temporarily OA and the content that was already held at PSUL, 85% of the free offers became available to PSUL. The fact that only a small portion (8%) of these free offers was already held at PSUL might indicate that most of the offers were either new, not high-priority or not affordable for PSUL.

Free offers provide intangible value for both libraries and vendors that cannot be measured through cost-per-use data analysis. PSUL gained opportunities to trial new products without any risk, temporarily expand their collections, and help users during the crisis when access to the library facilities were closed and services were disrupted. PSUL’s Acquisitions unit added resources only when the benefits for users outweighed the costs such as staff efforts and technical issues. Vendors increased product visibility, gained usage data, and created goodwill. The cost benefit analysis showed that libraries can increase the benefits by proactively asking for free access and requesting extension of the free offers. They can minimize the costs by accepting only valuable offers for their purposes and clarifying the parameters of the temporarily added free resources internally and externally through a public website.

This study is relevant to business librarianship not only because these free offers included business and related disciplines but also because some business librarians engage with vendor relations and need to understand different business models including free offers. The insights from this study suggest that these free offers can be mutually beneficial for both libraries and vendors particularly during COVID-19 and other challenging times. Vendors might consider extending free offers to increase their visibility while protecting their revenue from established products because many libraries are likely to have difficulty adding new resources due to financial and other challenges during the pandemic.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Julia Proctor for her contribution to the library and information science literature review, her evaluation of free offers, and her insightful comments on the draft manuscript. I would also like to thank Jamie Jamison for his timely activation and deactivation of free offers, Penn State Libraries Discovery, Access, and Web Services for maintaining the temporary free offers website while they were active, and reference and instruction colleagues for supporting library users utilizing a variety of resources including free offers during the COVID-19 pandemic. These colleagues’ efforts allowed me to conduct this study.

References

Ajorlou, A., Jadbabaie, A., & Kakhbod, A. (2018). Dynamic pricing in social networks: The word-of-mounth effect. Management Science, 64(2) 971–979. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2016.2657https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2016.2657

Anderson, J. C., & Narus, J. A. (1998). Business marketing: Understand what customers value. Harvard Business Review, 76(6), 5–15.

Aiwuyor, Jessica. (2020, June 5). ACRL, ARL, Oberlin Group of Libraries urge library vendors to continue free access, hold subscription prices steady during COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.arl.org/news/arl-acrl-oberlin-group-of-libraries-urge-library-vendors-to-continue-free-access-hold-subscription-prices-steady-during-covid-19-pandemic/https://www.arl.org/news/arl-acrl-oberlin-group-of-libraries-urge-library-vendors-to-continue-free-access-hold-subscription-prices-steady-during-covid-19-pandemic/

Bhatt, A. H. (2015). E-trials in academic libraries: 101 and beyond. Journal of Electronic Resources Librarianship, 27(2) 121–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/1941126X.2015.1029424https://doi.org/10.1080/1941126X.2015.1029424

Bryce, D. J., Dyer, J. H., & Hatch, N. W. (2011). Competing against free. Harvard Business Review, 89(6), 104–111.

Chen, H., Duan, W., & Zhou, W. (2017). The interplay between free sampling and word of mouth in the online software market. Decision Support Systems, 95 82–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2017.01.001https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2017.01.001

Cialdini, R. B. (2001). Influence: Science and Practice (4th ed.). Allyn & Bacon.

Dallas, S. K., & Morwitz, V. G. (2018). “There ain’t no such thing as a free lunch”: Consumers’ reactions to pseudo-free offers. Journal of Marketing Research, 55(6) 900–915. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022243718817010https://doi.org/10.1177/0022243718817010

Datta, H., Foubert, B., & Van Heerde, H. J. (2015). The challenge of retaining customers acquired with free trials. Journal of Marketing Research, 52(2) 217–234. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.12.0160https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.12.0160

Emanuel, M. (2013). Using screencasting to promote database trials and library resources. Journal of Electronic Resources Librarianship, 25(4) 277–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/1941126X.2013.847675https://doi.org/10.1080/1941126X.2013.847675

Foubert, B., & Gijsbrechts, E. (2016). Try it, you’ll like it-or will you? The perils of early free-trial promotions for high-tech service adoption. Marketing Science, 35(5) 810–826. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.2015.0973https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.2015.0973

Gupta, S., & Mela, C. F. (2008). What is a free customer worth? Harvard Business Review, 86(11), 102–109.

International Coalition of Library Consortia. (2020). ICOLC COVID19 complimentary expanded access specifics. [Data set]. https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1xiINlF9P00tO-5lGKi3v4S413iujYCm5QJoKUG19a_Y/edit#gid=2027816149https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1xiINlF9P00tO-5lGKi3v4S413iujYCm5QJoKUG19a_Y/edit#gid=2027816149

International Coalition of Library Consortia. (2020, March 13). Statement on the global COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on library services and resources. https://icolc.net/statement/statement-global-covid-19-pandemic-and-its-impact-library-services-and-resourceshttps://icolc.net/statement/statement-global-covid-19-pandemic-and-its-impact-library-services-and-resources

Li, F., & Yi, Z. (2017). Trial or no trial: Supplying costly signals to improve profits. Decision Sciences, 48(4) 795–827. https://doi.org/10.1111/deci.12233https://doi.org/10.1111/deci.12233

Li, H., Jain, S., & Kannan, P. K. (2019). Optimal design of free samples for digital products and services. Journal of Marketing Research, 56(3) 419–438. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022243718823169https://doi.org/10.1177/0022243718823169

Pionke, J. J. (2015). Community organizing for database trial buy-in by patrons. Journal of Electronic Resources Librarianship, 27(3) 165–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/1941126X.2015.1059643https://doi.org/10.1080/1941126X.2015.1059643

The Pennsylvania State University. (2020). Temporary and expanded access to vendor and publisher resources.

VitalSource. (2020). VitalSource helps. https://get.vitalsource.com/vitalsource-helpshttps://get.vitalsource.com/vitalsource-helps

Appendix

Free Offers for Academic Libraries

Offer Date |

Effective Thru |

Length (day) |

Extended? |

Provider |

Resource |

Type |

Registration required? |

Added? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

3/11/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

111 |

unknown |

Docuseek |

Bullfrog Films and Icarus Films on Docuseek |

e-videos |

yes |

held |

3/12/2020 |

6/15/2020 |

95 |

unknown |

JoVE |

JoVE Science Education Library |

e-videos |

yes |

yes |

3/13/2020 |

5/31/2020 |

79 |

yes |

Kanopy |

Free films |

e-videos |

no |

OA |

3/15/2020 |

unknown |

unknown |

unknown |

Ohio State University Press |

Language Files |

e-books |

no |

OA |

3/17/2020 |

6/29/2020 |

104 |

yes |

Cambridge University Press |

Cambridge Core |

e-books |

yes |

yes |

3/17/2020 |

6/29/2020 |

104 |

yes |

Cambridge University Press |

Cambridge Elements |

e-books |

yes |

yes |

3/17/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

105 |

unknown |

University of Michigan Press |

University of Michigan Press |

e-books |

no |

OA |

3/18/2020 |

8/31/2020 |

166 |

yes |

Elsevier |

Elsevier ScienceDirect e-textbooks |

e-books |

no |

yes |

3/18/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

104 |

unknown |

Harvard University Press |

LOEB CLASSICAL LIBRARY |

e-books |

yes |

no |

3/18/2020 |

unknown |

unknown |

unknown |

Publishers Weekly |

Publishers Weekly |

e-journals |

no |

OA |

3/18/2020 |

unknown |

unknown |

unknown |

Wiley |

Cochrane Library |

database |

no |

OA |

3/18/2020 |

5/31/2020 |

74 |

yes |

Wolters Kluwer |

Up to Date |

database |

yes |

no |

3/19/2020 |

8/31/2020 |

165 |

yes |

American Mathematical Society |

MathSciNet |

various |

no |

OA |

3/19/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

103 |

yes |

Bloomsbury |

Bloomsbury Digital Resources |

various |

yes |

yes |

3/19/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

103 |

yes |

Bloomsbury |

Drama Online |

various |

yes |

yes |

3/19/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

103 |

yes |

Bloomsbury |

Human Kinetics Library |

various |

yes |

yes |

3/19/2020 |

12/15/2020 |

271 |

yes |

Hein Online |

HeinOnline Academic |

database |

yes |

held |

3/19/2020 |

12/31/2020 |

287 |

yes |

JSTOR |

JSTOR resources during COVID-19 |

e-journals |

yes |

yes |

3/19/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

103 |

unknown |

JSTOR |

JSTOR resources during COVID-19 |

e-books |

yes |

yes |

3/19/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

103 |

yes |

MIT Press |

MIT Press Direct |

e-books |

yes |

yes |

3/20/2020 |

6/15/2020 |

87 |

unknown |

EBSCO |

EBSCO eBook Comprehensive Academic Collection |

e-books |

yes |

yes |

3/20/2020 |

6/15/2020 |

87 |

unknown |

EBSCO |

EBSCO Harvard Business Publishing Collection |

e-books |

yes |

held |

3/20/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

102 |

unknown |

University of California Press |

Free access to all UC Press journals through June 2020 |

e-journals |

no |

OA |

3/20/2020 |

unknown |

unknown |

unknown |

John Libbey Eurotext |

John Libbey Eurotext |

e-journals |

yes |

no |

3/22/2020 |

5/31/2020 |

70 |

unknown |

McGraw-Hill |

AccessEngineering |

various |

yes |

yes |

3/23/2020 |

5/15/2020 |

53 |

yes (requested) |

Digital Theatre Plus |

Digital Theatre Plus |

e-videos |

yes |

yes |

3/23/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

99 |

unknown |

ProQuest |

ProQuest Central |

various |

yes |

yes |

3/23/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

99 |

unknown |

ProQuest |

ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global |

dissertations |

yes |

yes |

3/23/2020 |

7/31/2020 |

130 |

yes |

SAGE |

SAGE Knowledge Books & Reference |

e-books |

yes |

held |

3/23/2020 |

7/31/2020 |

130 |

yes |

SAGE |

SAGE Research Methods Video |

e-videos |

yes |

yes |

3/23/2020 |

7/31/2020 |

130 |

yes |

SAGE |

SAGE Video |

e-videos |

yes |

yes |

3/24/2020 |

6/1/2020 |

69 |

Princeton University |

Index of Medieval Art |

database |

no |

OA |

|

3/24/2020 |

unknown |

unknown |

yes |

Brill |

COVID-19 Collection |

various |

no |

OA |

3/26/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

96 |

unknown |

Berghahn Books |

Berghahn Journals |

e-journals |

no |

OA |

3/26/2020 |

5/31/2020 |

66 |

unknown |

Brepols Publishers |

Brepols |

various |

yes |

no |

3/26/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

96 |

unknown |

Canadian Electronic Library |

desLibris |

various |

yes |

no |

3/27/2020 |

unknown |

unknown |

unknown |

ASTM International |

ASTM Standards & COVID-19 |

standards |

yes |

no |

3/27/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

95 |

unknown |

Project Muse |

Free Resources on MUSE During COVID-19 |

e-books |

no |

yes |

3/27/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

95 |

unknown |

Project Muse |

Free Resources on MUSE During COVID-19 |

e-journals |

no |

yes |

3/27/2020 |

6/15/2020 |

80 |

yes |

Infobase |

Open Trial Distance Learning Packages for Institutions Affected by COVID-19 |

database |

yes |

no |

3/30/2020 |

8/31/2020 |

154 |

yes |

e-Marefa |

Specialized Services |

database |

yes |

no |

3/30/2020 |

unknown |

unknown |

unknown |

Érudit |

COVID-19: Érudit Access and Services |

e-journals |

no |

OA |

3/30/2020 |

60 days |

60 |

unknown |

Wolters Kluwer (OVID) |

Global Infectious Diseases and Epidemiology Online Network (GIDEON) |

database |

yes |

no |

3/31/2020 |

8/31/2020 |

153 |

yes |

EDP Sciences |

EDP Sciences |

e-journals |

no |

OA |

4/1/2020 |

Unknown |

unknown |

unknown |

Library Journal |

Library Journal |

e-journals |

no |

OA |

4/2/2020 |

6/15/2020 |

74 |

yes |

Annual Reviews |

Annual Reviews Journals |

e-journals |

no |

yes |

4/2/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

89 |

unknown |

GeoScience-World |

A comprehensive resource of eBooks for researchers in the Earth Sciences |

e-books |

no |

OA |

4/3/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

88 |

unknown |

American Economic Association |

Open Access to AEA Journals through June 30 |

e-journals |

no |

held |

4/3/2020 |

8/31/2020 |

150 |

unknown |

ProQuest |

Coronavirus Research Database |

database |

yes |

yes |

4/3/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

88 |

unknown |

IEEE |

Now Publishers Foundations and Trends® Technology eBooks |

e-books |

yes |

no |

4/3/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

88 |

yes |

Newspaper-Archive |

NewspaperArchive |

database |

yes |

held |

4/6/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

85 |

unknown |

De Gruyter |

ACCESS YOUR LIBRARY’S PRINT COLLECTION ONLINE |

e-books |

yes |

no |

4/6/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

85 |

unknown |

EBSCO |

African American Historical Serials Collection |

database |

yes |

yes |

4/6/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

85 |

unknown |

EBSCO |

Applied Science & Business Periodicals Retrospective: 1913–1983 |

database |

yes |

yes |

4/6/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

85 |

unknown |

EBSCO |

Arte Público Hispanic Historical Collection, Series 1 |

database |

yes |

yes |

4/6/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

85 |

unknown |

EBSCO |

Arte Público Hispanic Historical Collection, Series 2 |

database |

yes |

yes |

4/6/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

85 |

unknown |

EBSCO |

ATLA Historical Monographs Collection: Series 1–13th Century to 1893 |

database |

yes |

yes |

4/6/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

85 |

unknown |

EBSCO |

ATLA Historical Monographs Collection: Series 2–1894 to 1923 |

database |

yes |

yes |

4/6/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

85 |

unknown |

EBSCO |

Atlantic Magazine Archive: 1857–2014 |

database |

yes |

yes |

4/6/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

85 |

unknown |

EBSCO |

Bloomberg Businessweek Archive: 1929–2000 |

database |

yes |

yes |

4/6/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

85 |

unknown |

EBSCO |

Business Periodicals Index Retrospective: 1913–1982 |

database |

yes |

yes |

4/6/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

85 |

unknown |

EBSCO |

Ebony Magazine Archive: 1945–2014 |

database |

yes |

yes |

4/6/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

85 |

unknown |

EBSCO |

Education Index Retrospective: 1929–1983 |

database |

yes |

yes |

4/6/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

85 |

unknown |

EBSCO |

Forbes Magazine Archive: 1917–2000 |

database |

yes |

yes |

4/6/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

85 |

unknown |

EBSCO |

Fortune Magazine Archive: 1930–2000 |

database |

yes |

yes |

4/6/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

85 |

unknown |

EBSCO |

Frick Art Reference Library Periodicals Index |

database |

yes |

yes |

4/6/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

85 |

unknown |

EBSCO |

Humanities Index Retrospective: 1907–1984 |

database |

yes |

yes |

4/6/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

85 |

unknown |

EBSCO |

Index to Legal Periodicals Retrospective: 1908–1981 |

database |

yes |

yes |

4/6/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

85 |

unknown |

EBSCO |

Library Literature & Information Science Retrospective: 1905–1983 |

database |

yes |

yes |

4/6/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

85 |

unknown |

EBSCO |

Nation Magazine Archive: 1865–2020 |

database |

yes |

yes |

4/6/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

85 |

unknown |

EBSCO |

National Review Magazine Archive: 1955- June 2020 |

database |

yes |

yes |

4/6/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

85 |

unknown |

EBSCO |

People Magazine Archive: 1974–2000 |

database |

yes |

yes |

4/6/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

85 |

unknown |

EBSCO |

Social Sciences Index Retrospective: 1907–1983 |

database |

yes |

yes |

4/6/2020 |

6/2/2020 |

57 |

unknown |

Wolters Kluwer |

Acland’s Video Atlas of Human Anatomy |

e-videos |

yes |

yes |

4/6/2020 |

6/2/2020 |

57 |

unknown |

Wolters Kluwer |

Advanced Practice Nursing |

various |

yes |

yes |

4/6/2020 |

6/2/2020 |

57 |

unknown |

Wolters Kluwer |

Exercise Science Collection |

various |

yes |

yes |

4/6/2020 |

6/2/2020 |

57 |

unknown |

Wolters Kluwer |

Occupational Therapy Collection |

various |

yes |

yes |

4/6/2020 |

6/2/2020 |

57 |

unknown |

Wolters Kluwer |

Physical Therapy Collection |

various |

yes |

yes |

4/6/2020 |

8/31/2020 |

147 |

yes |

Paratext |

U.S. Documents Masterfile |

various |

yes |

no |

4/7/2020 |

5/31/2020 |

54 |

unknown |

RILM |

RILM |

database |

no |

OA |

4/14/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

77 |

unknown |

Gale |

Gale/CRL Partnership for Access to Gale Primary Sources |

database |

yes |

yes |

4/14/2020 |

7/31/2020 |

108 |

yes |

Thieme Medical Publishers |

Thieme MedOne Education |

database |

yes |

yes |

4/15/2020 |

12 weeks |

84 |

unknown |

Adam Matthew |

Adam Matthew (All Collections) |

database |

yes |

held |

4/15/2020 |

7/31/2020 |

107 |

unknown |

Springer-Nature |

SpringerNature textbooks |

e-books |

no |

yes |

4/17/2020 |

6/30/2020 |

74 |

unknown |

Mango Languages |

Mango Languages |

database |

yes |

yes |

4/28/2020 |

5/28/2020 |

30 |

unknown |

Numérique Premium |

Numérique Premium |

e-books |

yes |

no |

Data Labels

Extended – “Yes” shows the free offer was extended in duration.

Added – The free offer was added to the PSUL collection.

Held – PSUL already held the resource and the free offer was not added.

OA – The resource was available with open access, providing free, immediate, and online availability of the content.