Who We Are and the Nature of Our Collections

Baker Library collects business records dating from the 14th century to the present and the records of the Harvard Business School since its founding in 1908. Although we are actively working to diversify the Library’s collections, the records predominately reflect business and academic fields in Western culture, which includes white-owned businesses, white families, and white individuals. Our staff has been and continues to be predominantly white, and we recognize that our descriptions have been written through a “white lens,” meaning we often describe those who are like us and overlook people and communities we are not part of, many of which have been, and continue to be, marginalized and underrepresented.

We have been aware of the shortcomings of our collection descriptions for quite some time. Interactions with faculty and researchers have exposed the lack of diversity in collection materials, the challenge of searching for collection materials to meet user needs has shown that some collections are under-described, and as the language used in description has evolved, words or phrases in the past may now be considered outdated or even offensive. Over the years we have engaged in various projects focused on identifying and describing specific marginalized and underrepresented people in collection materials and addressing problematic language; however, these efforts did not result in a holistic re-examination of our descriptive guidelines

But faced with the events of the past year, re-evaluation of our descriptive practices could no longer be ignored.

A Renewed Effort

In the wake of George Floyd’s murder on May 20, 2020, and the subsequent protests against police brutality and racism, former Harvard Business School (HBS) Dean Nitin Nohria held open conversations with the HBS community about race and equity. Community members made it clear that the school had “failed to do all it could and should have done to welcome and advance Black talent, advance knowledge related to race, educate students about racism and anti-racism, and engage the business community in change efforts” (Harvard Business School, 2020). In June 2020, the Dean announced the formation of the Dean’s Anti-Racism Task Force and over several months drafted, finalized, and widely communicated the HBS Action Plan for Racial Equity1. As members of the HBS community, Baker Library embraced the actions outlined in the School’s plan, recognizing that it was imperative to make clear how we intended to take meaningful action against structural racism and inequality.

To align with the efforts of the School, Baker Library’s leadership created a year-long strategic priority to further the HBS Action Plan for Racial Equity, which included the project we were asked to co-lead. The primary goals of the project, which started in September 2020, were to (1) focus on writing ethical and inclusive description that gives voice to those who may have previously been omitted, underrepresented, or marginalized in our descriptive practices, and (2) implement the ongoing processes of remediating our description, specifically focusing on addressing and rectifying biased language that demeans or excludes people because of identity, condition, or beliefs. When defining the goals of the project, we were confident that our efforts would promote responsible, transparent, and responsive descriptive practices, produce a richer, more inclusive, and engaged researcher experience, and ensure equitable access and accessibility to the collections we steward.

Our Approach

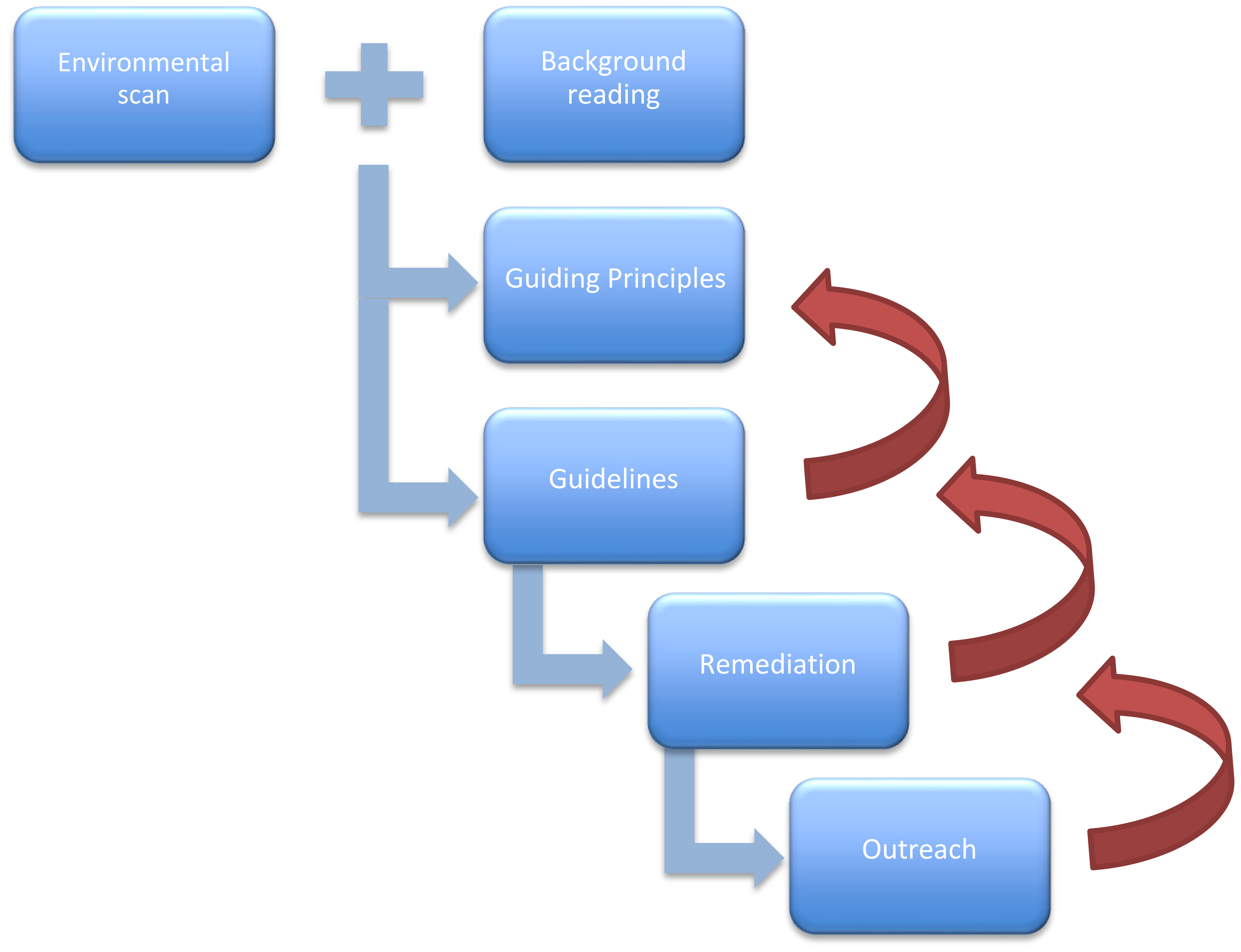

As we began to thoroughly examine the high-level objectives of the strategic project, we recognized that its complexity necessitated developing an approach for dividing it into smaller components. We felt confident that this approach would not only make the project more manageable but would also clearly show the hierarchy and connectivity between the tasks. See Figure 1.

The project began with an environmental scan of the work happening at institutions of similar size concerning their efforts on addressing conscious and inclusive description, including the guidelines developed by our colleagues at the Center for the History of Medicine at Countway Library (Lellman, 2021). Through this effort, we created a bibliography of initial readings, including professional literature, listservs, social media, and HBS journal articles, which we anticipated could inform our work. The first article we read as a team was the Archives for Black Lives for Philadelphia Anti-Racist Description Resources (Anti-Racist Description Working Group, 2019). In the discussions that followed, team members examined and reflected upon how archival description can be harmful, the role we play in the description, and what we could do individually and collectively to take actionable steps to unlearn the “neutral voice of traditional archival description” (Anti-Racist Description Working Group, 2019, p.8). These discussions, coupled with the environmental scan and other readings identified through our research, influenced the shaping of our Guiding Principles for Conscious and Inclusive Description. The Library’s position statement outlines how we intend to take meaningful action against structural racism and inequity, and provides the framework for developing conscious and inclusive description guidelines.

Understanding past descriptive practices was a necessary first step for moving forward with the guidelines, and there was no better way of doing this than finding examples in the collections held by the Library.

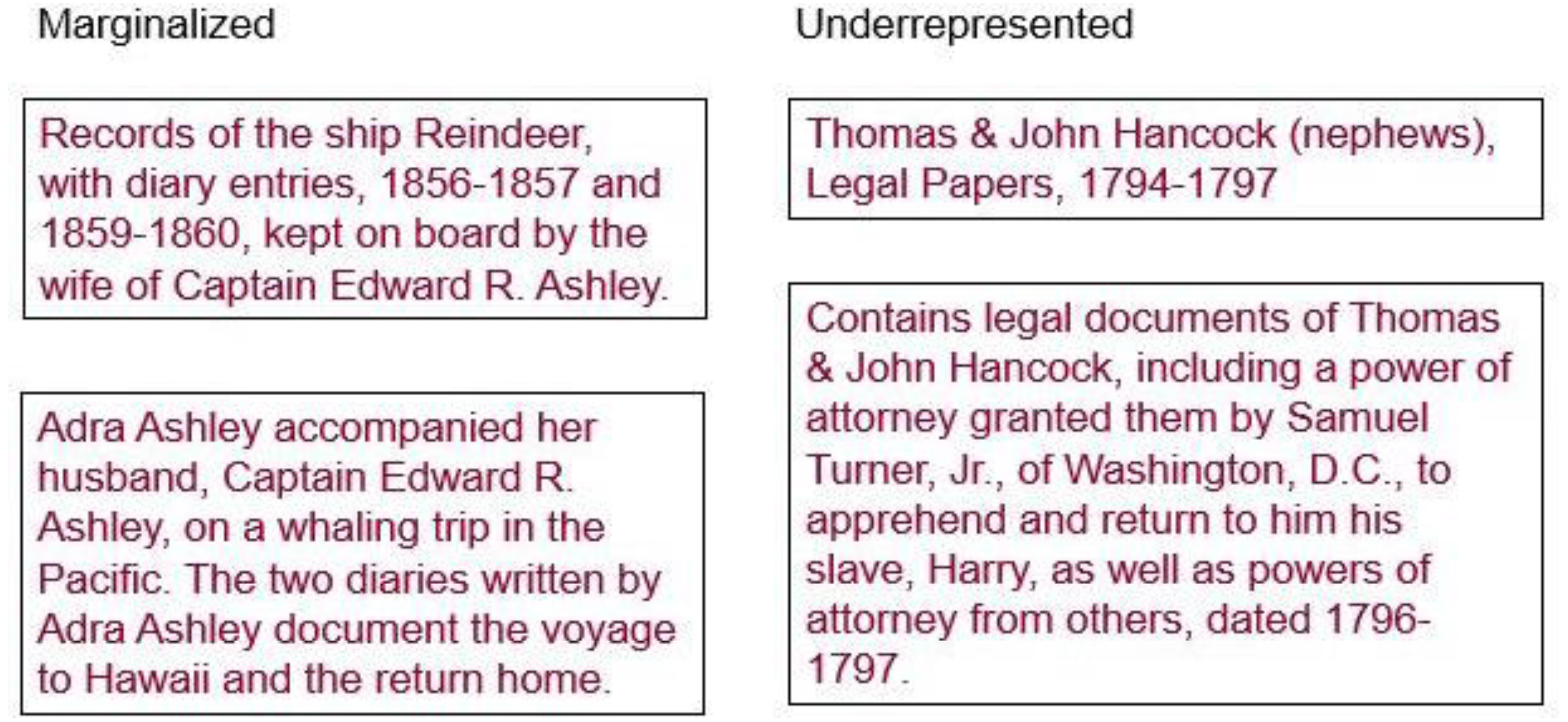

Marginalized and Underrepresented Communities

A closer look at examples of collection descriptions that have either marginalized or underrepresented individuals or communities reveal problems that require further examination (as shown in Figure 2). The example on the left illustrates how the actual creator of the collection, Adra Ashley, was marginalized in favor of her husband and the ship he captained by referring to her as the captain’s “wife.” In reviewing the collection materials, we confirmed that Adra clearly authored the diaries, not her husband, and that she had a much more active role in documenting the whaling voyage to Hawaii and the return home. The example on the right illustrates how our collection descriptions have underrepresented groups. The original description only included a folder title, with no indication that the legal papers include documents about Harry, an enslaved man, whose enslaver granted the legal right to Thomas and John Hancock to apprehend and return him.

Offensive Language and Content

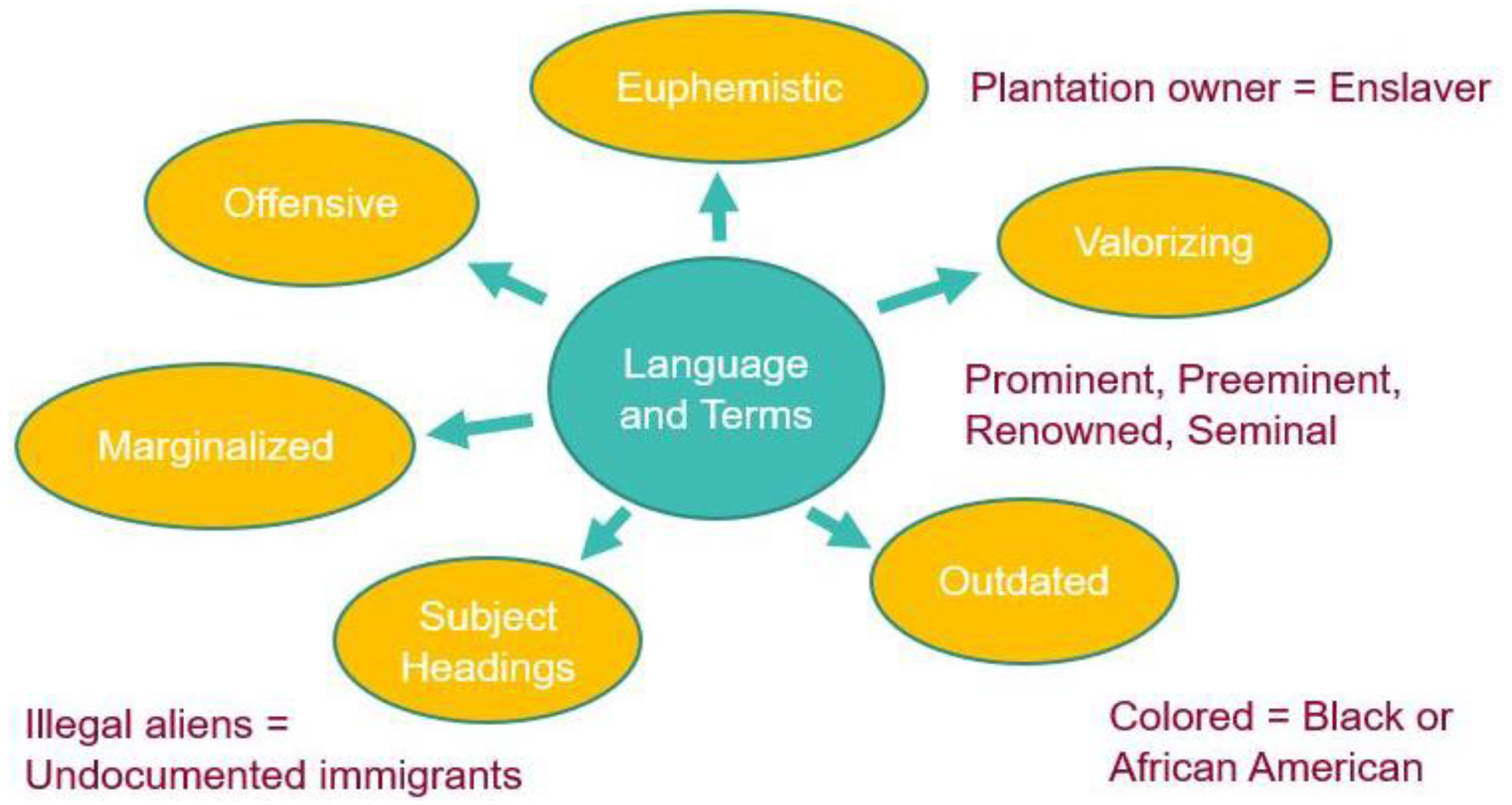

Euphemistic, offensive, and harmful language and content in archival description is problematic, as it can perpetuate historic racism and white supremacy and dehumanize or misrepresent marginalized communities. Users of collection materials can also find language and terms offensive and harmful in various ways, countering Baker Library’s commitment to having a welcoming space for all those who visit.

Euphemistic terms like planter instead of enslaver, valorizing or venerating terms like prominent, preeminent, renowned, and seminal, and outdated terms such as colored instead of African American or Black are typical examples. Users can also encounter offensive and harmful subject headings like the LCSH heading for “illegal aliens,” requiring us to consider other options for subject access. See Figure 3.

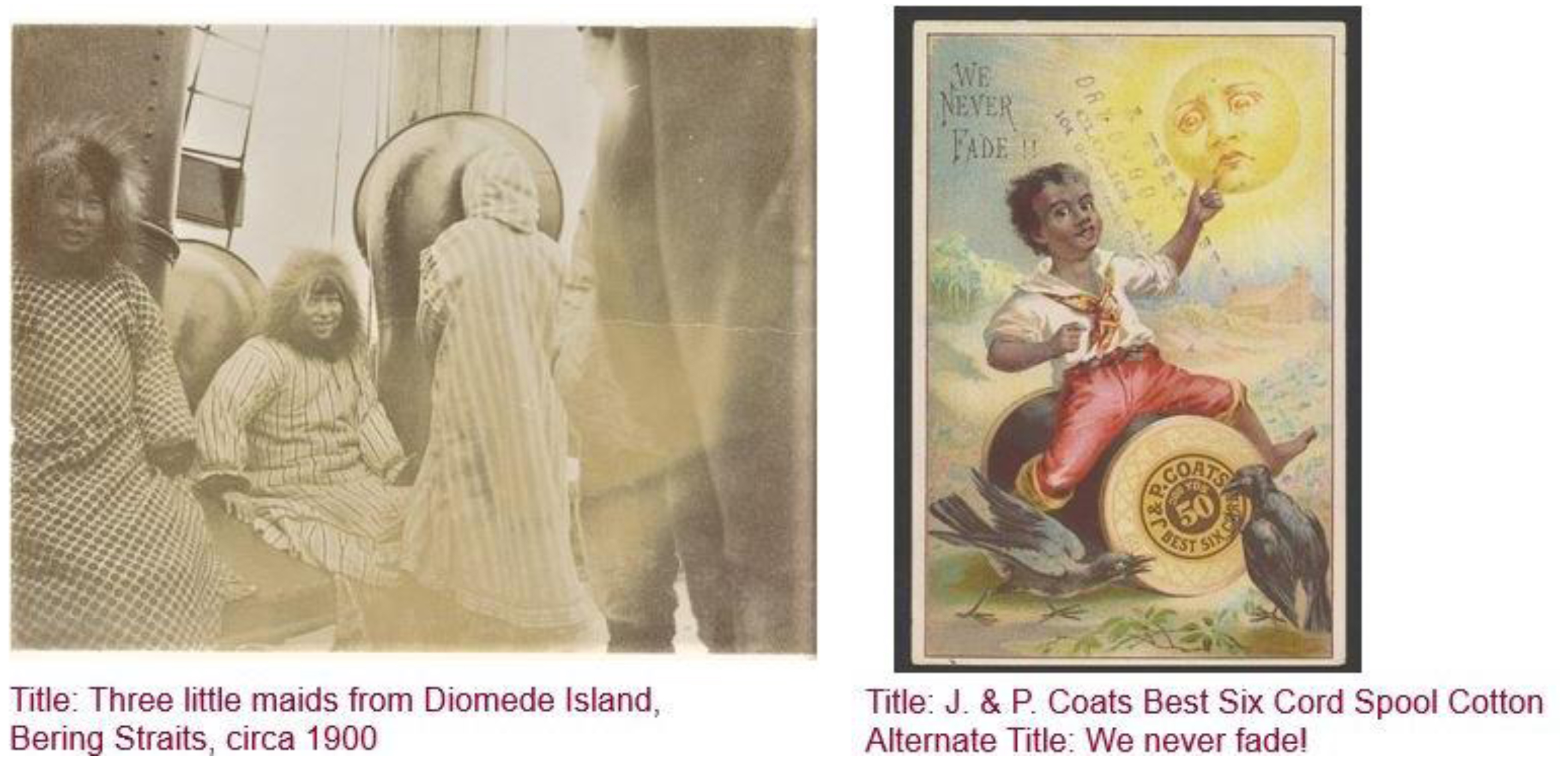

We can remediate any offensive language or terms that exist in the description of our legacy collections, but we also have collections that include offensive and harmful content. When our collections include racist language or content, we need to describe the subject matter thoughtfully so it can be researched but not erased. As these materials serve as evidence of the activities of the institution, community, or individual, we have committed to not removing or censoring them. See Figure 4 for two examples. The photograph on the left is of an indigenous woman in the Pacific Steam Whaling Company Records (https://id.lib.harvard.edu/ead/bak00223/catalog). Our descriptive practices included transcribing titles marked on the back of photographs without providing any context. It would be less offensive to relegate the creator’s title to a note field and devise our own title that accurately reflects the subject of the photograph. On the other hand, the J. & P. Coats trade card on the right uses a harmful stereotype of a Black boy to illustrate that their cotton thread will never fade. Although “African American” and “ethnic stereotypes” are two of the subject headings applied to this trade card, there is no note providing context for the illustration and the product advertised.

With a better understanding of how language matters, we began actively working on drafting conscious and inclusive description guidelines, which, when completed, will provide clarity on how to address offensive, euphemistic, or harmful language in our collection descriptions and cataloging and will also provide a framework for how to give voice to those who may have been previously omitted, underrepresented or marginalized in our description. Knowing we needed a starting point for drafting these guidelines, we identified what we were already aware of concerning the language and terms in the description of our legacy collections.

Mindful that we actively incorporate the use of valorizing and venerating language to describe HBS faculty and white businessmen, we decided to rethink and revise our approach to writing the administrative and biographical history notes. This element of the finding aid is necessary for describing the creator or creators of the records. For an individual creator, this takes the form of a short biographical note describing the key details of their life. For a corporate creator, it is an administrative history note about that corporate body. The purpose of the administrative and biographical history notes is to give an understanding of who the creator(s) of the records were and why they may be relevant to an archives user. Through readings, team discussions, and multiple revisions, we wrote guidelines that provided clarity for writing factually based notes using clear and direct language, including avoiding adjectives or descriptions that assign importance or significance to the creator and their accomplishments. Work on the guidelines is expected to continue to the end of 2021. The long timeframe reflects the complexity and sometimes contentious nature of writing the guidelines and the challenges of group consensus. Although this is a long-term commitment for team members, we want to ensure that we are thorough and thoughtful in our approach.

We are also focused on the revision or remediation of existing collection descriptions. Addressing language in our description can serve to provide context and a counter-narrative reflecting the perspective of the documented community. It can also help to address the power imbalances between creators and subjects of records.

Due to the extent of the collections held by Baker Library that may require some level of remediation, this phase of the project is focused on remediating description for a discrete grouping of collections that are known to be problematic, specifically collections documenting business in the Antebellum period. These collections include plantation records, records documenting the transatlantic slave trade, and business records of merchants who were also enslavers. Grouping materials for remediation allows us to be more deliberate in our approach when creating standards. So instead of trying to remediate all collection descriptions at once, by more narrowly focusing, we can create specific standards which can then be refined or expanded, and then applied to other groupings of materials we plan to remediate in the future.

The last component, which is currently in the development phase, is how to best communicate our work to those within and outside our library. We all agree that this is a critical component of our strategic project as it will not only inform those who use Baker’s collections that this work is part of our continuing education and critical examination of our descriptive practices, but also shows a commitment for our ongoing support of the School’s plan for Advancing Racial Equity & Diversity.

Lessons Learned

The team regularly takes time to reflect on both the positive and the more challenging experiences of the project. Sharing and discussing these lessons allows us to not only make decisions on how to use the knowledge we have gained but also to celebrate how far we have come.

Learning and collaboration are key. Specifically, learning about the aspects of conscious and inclusive description from many viewpoints allows us to understand the multitude of contexts that inform users’ interpretation of our description. This requires continual research and collaboration both within and outside of the archival profession, here in Baker, in the Harvard Library, and beyond.

Language matters. While we knew the importance of accuracy and precision in our descriptive language, we have learned many new ways in which language can matter and how it can affect the discovery and interpretation of the collections in our care. Most importantly, we have realized that we don’t know the full scope of this work and we need to be continually learning.

The process is not straightforward and will take longer than originally planned.

Amending policies or guidelines can be contentious and difficult, particularly if the policies or guidelines represent a big shift in the organization’s philosophy.

Remediation of description is not as simple as coming up with a list for one-to-one replacement of terms or finding the “right” answer. Some of the questions we have been working through are: How do you describe creators’ identities in a way that enlightens users but does not categorize, generalize, or stereotype the creators or their experiences? How do you reconcile terms that were commonplace at a point in time or are preferred by the creator but that are now considered derogatory or hateful without losing the historical context or the creator’s self-identification?

Balancing all aspects of the work that needs to be done is critical. It is important to balance reading, discussion, writing, meetings, and planning with actually starting the project and moving it forward. Because many of the topics we want to tackle can be overwhelming, contentious, and ambiguous, it is often difficult and sometimes paralyzing to figure out where to start. What we have learned as a group is that while it is important to have structure, sometimes you just have to dive in and figure it out as you go along.

We are privileged to work at a predominantly white institution (PWI) that supports these broader changes at an administrative level. Support from the Dean and the Dean’s Office, the Baker Library leadership team, and our Baker colleagues has been critical in our early efforts and has provided the authority to go ahead and change our collection descriptions. We know of colleagues that do not have the support, the time, or the resources to do the level of work that we are doing.

Updates since March 2021

Since presenting on this topic in March 2021, the Baker Library project team has completed a major component of the project and has made strides in other aspects.

Guiding Principles. The team finalized and made publicly available its Guiding Principles for Conscious and Inclusive Description (Baker Library Special Collections, 2020), shown in Figure 5. These principles outline our approach to examining current descriptive practices and acknowledges our ongoing commitment to this work.

Description remediation. We decided to begin remediating our collection descriptions before finalizing the Guiding Principles and while drafting new descriptive guidelines. To date, we have established a project management plan, identified and prioritized collections for remediation, and have drafted descriptive practices for remediation.

Project continuation. The Baker Library leadership team has recognized the importance of this strategic project and concluded that it will remain a priority for fiscal year 2022. As the work continues, the project will have three primary goals:

devise and implement a broader framework for creating and implementing guiding principles and plans;

formalize principles and guidelines for conscious and inclusive description for Baker Library collections; and

investigate the total costs of stewardship, which proposes a holistic approach to understanding the resources necessary to responsibly acquire and steward collection materials including making informed, shared collection-building decisions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Deb Wallace and the planning committee of the Academic Business Library Directors (ABLD) for the opportunity to present on this topic at the ABLD 2021 Annual Meeting. We would also like to acknowledge the members of the Baker Library Special Collections project team (Ben Johnson, Kate Neptune, Keith Pendergrass, and Liam Sullivan), whose dedicated work and commitment have moved this project forward.

Notes

- In 2021, the name of the plan was changed to Advancing Racial Equity & Diversity. ⮭

References

Anti-Racist Description Working Group. (2019, October). Archives for Black Lives in Philadelphia Anti-racist description resources. Archives for Black Lives in Philadelphia. https://archivesforblacklives.files.wordpress.com/2019/10/ardr_final.pdfhttps://archivesforblacklives.files.wordpress.com/2019/10/ardr_final.pdf

Baker Library Special Collections. (2020). Guiding principles for conscious and inclusive description. https://www.library.hbs.edu/find/collections-archives/special-collections/guiding-principles-for-conscious-and-inclusive-descriptionhttps://www.library.hbs.edu/find/collections-archives/special-collections/guiding-principles-for-conscious-and-inclusive-description

Harvard Business School. (2020, June). Developing the Plan - Advancing Racial Equity. https://www.hbs.edu/racialequity/action-plan/Pages/developing-the-plan.aspxhttps://www.hbs.edu/racialequity/action-plan/Pages/developing-the-plan.aspx

Lellman, Charlotte G. (2021, February 18). Guidelines for Inclusive and Conscientious Description, Center for the History of Medicine: Policies & Procedures Manual. https://wiki.harvard.edu/confluence/display/hmschommanual/Guidelines+for+Inclusive+and+Conscientious+Descriptionhttps://wiki.harvard.edu/confluence/display/hmschommanual/Guidelines+for+Inclusive+and+Conscientious+Description