This case study outlines the author’s two years of experience designing and teaching a one-credit course, “Data Storytelling.” In this course, the students found and evaluated secondary information sources, conducted first-person interviews, and presented a persuasive argument that synthesized these, and other, sources. The course was developed from the author’s previous experience working with entrepreneurs. The use of first-person interviews in the course grounds the secondary data that students work with in their interviewee’s experience, and this interplay can have a transformative effect on how students understand an issue.

This paper details the novel dynamics of teaching data literacy in this way, and discusses the course’s process, successes, and challenges. These topics include adjustments that the author made to the course between the first and second years, as well as anticipated forthcoming improvements.

Core concepts

Data literacy is an evolving and important topic for academic libraries. Calzada Prado and Marzal provide the following useful definition: “Data literacy can be defined […] as the component of information literacy that enables individuals to access, interpret, critically assess, manage, handle and ethically use data” (2013, p.126). This definition emphasizes the interrelated set of skills that combine for data literacy. This definition also differentiates data literacy from data science, which can be defined as “the field of study that combines domain expertise, programming skills, and knowledge of mathematics and statistics to extract meaningful insights from data” (DataRobot, n.d.). This definition is helpful in the context of course design and instruction by indicating the depth to which topics are pursued in a course focused on data literacy: not statistics, not dedicated to any specific discipline, and not based on conducting computational or code-based analysis. Instead, this data literacy course emphasizes students gaining a deeper understanding of how data and statistics are generated and presented, and the choices they can make in using data to support their own decision making and communication.

Those interested in reading more on the topic of data literacy in academic libraries, particularly business libraries, will find a recent proliferation of works on the topic, including The Data Literacy Cookbook (Getz & Brodsky, 2022). Another title is Data Literacy in Academic Libraries: Teaching Critical Thinking with Numbers, which includes a chapter very relevant to this topic: “Data Literacy for Entrepreneurs: Exploring the Integration of Pedagogy, Practice & Research at MIT”. Additionally, The Journal of Business & Finance Librarianship’s special issue on business and financial data, Volume 25 Issue 3–4, 2020, has several articles on this topic.

Data literacy has particular value for entrepreneurship. While entrepreneurship education often exhorts students to “Get out of the building” and go talk to potential customers (termed customer discovery), there is also great importance placed on how market data can justify entrepreneurial activity. As Jefferson quotes one business librarian:

Entrepreneurs need to use numeric evidence to recruit support for their work and inform their own decisions, but they often rely on other sources for that evidence. Their skills in data literacy are crucial to success. Yet librarians who work with entrepreneurs are in a position to emphasize not only the importance of data literacy in the evaluation, creation, and synthesis of figures such as market size, but also to indicate how this data literacy can interact with the work of customer discovery.Think back to the market size number. You have got all these numbers floating around. Rather than just cherry picking one, you need to decide which one you’re going to use. You need to have dug into it a little bit, so you know why that’s the number that you chose or whatever method you came up with, because you use this in your presentation or your reports to the client

(2020, p.160).

In this course, design thinking is introduced to students as a general approach to problem solving and a set of tools for customer discovery. Design thinking, and its closely linked alternative expression, Human-Centered Design, are a set of practices that “[put] the people you serve at the center of your design process to come up with new answers to difficult problems” (IDEO, n.d.). IDEO is an influential design company that has pioneered the use of design thinking methodology, most fully in technology-related industries, but now also in education and other environments where understanding of the end-user is crucial. Design thinking and human centered design approaches vary according to their source and application, but the steps of Empathize, Define, Ideate, Ideate, Prototype, Test, and Implement are widely deployed and built upon for design thinking applications (Gibbons, 2016). By integrating design thinking with data literacy, this course aimed to give students a range of skills that would allow them to begin finding information, practice varying their perspective, and synthesizing sources for presentation. These skills are valuable across many disciplines.

Course Background

This Data Storytelling course was taught in fall 2021 and fall 2022. The course is one example of a “Big Ideas Seminar” that is offered as part of Michigan State University’s Undergraduate Studies program. These are open to first- and second-year students, although most enroll during their first semester. Big Ideas Seminars are designed to help students “[d]evelop important college success skills, test and challenge ideas, and connect with faculty who will continue to have an interest in [them] and [their] studies here at MSU” (Michigan State University, 2022). Part of the special value these courses offer is the chance to take an in-person course with a small number of students that features an instructor who is motivated to work directly with students. For both semesters, the Data Storytelling course format involved a 50-minute class held once per week over the 14-week semester.

The learning objectives in the Data Storytelling course relate to the two major areas of activity: (1) finding and understanding statistics relevant to a students’ chosen topic and (2) contextualizing, synthesizing, and presenting that evidence to an audience in support of an argument. To support students’ ability to meet these objectives, they were required to develop a final presentation. Small, regular assignments were also assigned to encourage students to demonstrate their learning of each practice that was the focus of a lesson. A copy of the syllabus and assignment specifics are available via MSU Commons (https://doi.org/10.17613/ta84-j458) and also via the BLExIM registry (https://sites.google.com/view/blexim-sharing/home).

Course Activities

Topic Selection

Students first identified three topics of interest, and then narrowed to one topic using the following criteria:

Students must find people in their lives who they can speak with about their topic. If a topic is too remote or too personal, a student should seek out a topic that is more accessible.

Students should select a topic that is possible to quantify.

Students should be excited about the topic, and they must be willing to change their thinking about a topic if they discover new information.

The students then practiced creating search terms for their chosen topic . As a specific assignment, this allowed for instructor feedback on both topic and keywords.

As an aside, students were encouraged to change topics over the course of the semester, particularly in cases where they struggled to identify how a topic might be scoped and/or quantified. For example, one student selected the topic of Spanish colonization of the area now called Central America. In subsequent assignments, they confronted the limitations of what was quantified in various sources in relation to this topic, particularly in the sources the instructor chose to emphasize. Part way through the course, this student chose instead to focus on the modern-day experience of undocumented immigrants in the United States, which more readily lent itself to the activities of the course.

Gaining Context

Once students chose their topics, they used Statista to find statistics relevant to their work. The students then followed Statista’s citation to identify the organization that had generated the statistics. Students learned more about the organization using a method called “SIFT.” SIFT stands for Stop, Investigate the Source, Find Better Coverage, and Trace Claims, Quotes, and Media to the Original Context (Caulfield, n.d.). This set of information literacy steps was developed by Mike Caulfield to investigate claims found on the internet and is useful for investigating sources of information. These steps encourage students to consider the statistics themselves as products of real organizations with priorities and biases.

In a subsequent assignment, the class used ESRI’s Living Atlas tool to find mapped statistics on their topics. Living Atlas is a curated collection of maps that are both well-constructed and have appropriate metadata; it is available via the subscription resource ArcGIS Online. This activity challenges students to use effective keywords to find relevant maps while navigating limitations in the availability and presentation of statistics.

During the second iteration of the course, a major assignment was to find long-form journalism articles to bolster the students’ understanding of how their topics were currently changing through the implementation of data or statistics. These articles helped students better understand the experiences of professionals in the fields of study they choose by contextualizing their topic. Two pieces were used as examples: an article on statistics in basketball by Moneyball author Michael Lewis (Lewis, 2009), and an article on how Serena Williams’ experiences with healthcare illustrate broader problems in the healthcare experience of black women (Lockhart, 2018). The latter article was featured in the book Data Feminism, an exploration of data ethics and related topics through feminist lenses (D’Ignfazio and Klein, 2018).

Where students had a strong understanding of the differences between types of articles, this assignment was extremely successful in giving them a broader context and understanding of challenges present in the issues they were interested in. However, some students did not differentiate between types of articles, such as academic journal articles, press releases, and blog posts. These types of articles did not contain the context-rich insights that would complement the students’ other work. Consequently, in future iterations of the course, the instruction must include a more explicit explanation of the different types of sources and what is required of the assignment.

Across all these assignments (Statista, SIFT, ESRI ArcOnline, and long-form article search) the students’ ability to find relevant information was challenged, and in many cases their failed searches served as important feedback on their topic or their keywords. These failed searches were an important part of the learning process, and class discussions often circled back to which searches were proving successful for students, and why that would be. In the design thinking framework, students were testing prototypes for their end topic, iteratively working towards a stronger topic to implement for their final presentations.

Data ethics module from Visualizing the Future

The course also introduced ethical components to working with data, using a teaching resource developed by Visualizing the Future, an Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) funded “community of praxis focused on data visualization” (Visualizing the Future, n.d.). The module stimulated discussion on how data visualizations are subject to bias and the unintended consequences of their creators’ design choices. Using example visualizations, discussion prompts, and an explication of the data research lifecycle, this teaching module was highly engaging for students. The sample visualizations are great opportunities to consider design choices’ impact on an audience. The module’s explication of the data research lifecycle also aligns well with the design thinking process. What’s more, the data lifecycle specifically discusses how each stage can successfully consider community input, and how mistakes have ethical implications.

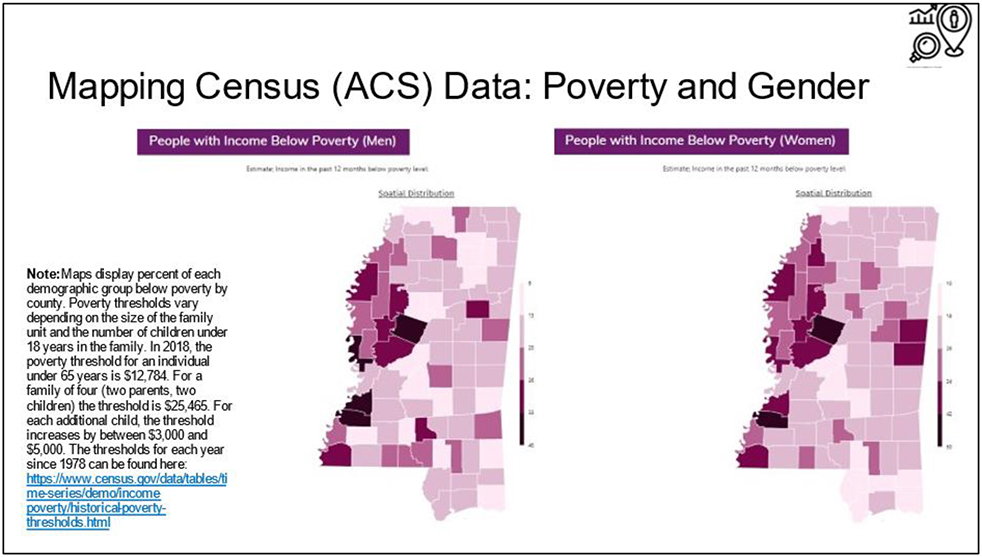

One discussion topic that resonated with students was an examination of a set of charts that represented poverty in a specific geography. Separate charts showed how the data would change when including different parameters, with these new visualizations catalyzing new conclusions. These charts and discussions allowed the class to explore intersectionality as a concept, and how visualizations selectively reveal information about their chosen topic.

Interviews

In an important complement to their work with internet-sourced resources, students were asked to interview people in their lives who had some experience with their topics. In the fall 2021 iteration of the course, students also used other data collection methods, such as creating a survey. For these activities, the course relied on the IDEO Design Kit, a web resource which includes descriptions of a wide range of methods (https://www.designkit.org/methods.html) for soliciting feedback and interacting with potential users of a product or service (IDEO, n.d.). To practice, students first interviewed each other using the “Five Why’s” method from the Design Kit.

The interviews proved transformative for many students. For example, one student studying electric cars interviewed their father, a potential EV customer. In their interview, the student discovered that the father was quite skeptical of environmental claims. This led the student to dig deeper into the processes of mining resulting in the batteries of electric cars, which they then presented to the class. In an example from fall 2021, a student interviewed multiple classmates about their perception and use of Amazon, which caused them to reevaluate their own claims about the usefulness of Amazon. In both cases, the students gained a more nuanced perspective, which they then shared with their classmates.

Across both years, students did a great job identifying people in their lives who would help them better understand some aspects of their topic, including professors, internship mentors, family members, former employers, and high school teachers. These interviewees revealed a variety of perspectives through their diverse relationships to the topics: nurses who would be users of technology, government officials who analyzed relevant topics, and manufacturing managers who worked in specific conditions.

In an example mentioned in the section on keywords and topic selection, one student was struggling to find quantitative representations of their original topic that they felt were compelling. After interviewing a family member, they landed on the topic of the lives of undocumented immigrants. The interview directly led them to discover statistics from the Pew Research Center to further connect to their argument, and their final presentation was a powerful and compelling piece.

Storytelling and the Final Presentation

The concept of storytelling was used to provide structure to the students’ presentations. The basic story arc that is followed in this course is Beginning, Tension, Conflict, and Conclusion. These calls to action were sometimes direct (e.g., “learn a skilled trade”) or subtle (e.g., requesting that audience members investigate how some phenomenon occurs in their lives). Though rudimentary, this basic outline was useful for students in structuring their arguments. The assignment required students to synthesize their topic into a five-minute presentation that introduced their topic, made an argument supported by statistical evidence, and featured some call to action for their audience.

There was a greater emphasis on the storytelling format in the second year. This came about because of a student request on behalf of their classmates; they thought there would be benefit from further coaching on the final presentation. Better supporting the students in developing their final presentations was done by scaffolding the individual lessons to align with that assignment. Toward the end of the semester, more class time was devoted to discussing the final presentation, particularly the story structuring.

Short Assignment Order and Descriptions

| Title of assignment | Description |

|---|---|

| Topic possibilities |

|

| Topic selection |

|

| Wikipedia and Statista |

|

| SIFT |

|

| Finding map content |

|

| Identifying relevant parties |

|

| Findings from interview |

|

| Response to class |

|

Course Management

Assessment and Revising the Course

To understand how to improve the course, formal and informal assessment methods were used. Student assignment submissions were an important indication of their skill development, as was participation in class activities and discussions. Conversations with students before, during, and after class, as well as the occasional email or visit to office hours, were all invaluable means of collecting information on student needs.

At the conclusion of each semester, students also provided direct feedback on the course via the final assignment and separately through the University’s formal course surveys, which students may complete for all credited courses. These submissions were the basis for much of the redesign of the course in between fall 2021 and fall 2022 semesters, as well as changes for upcoming years. These forms of feedback are not available for most library instruction.

Opportunities for intervention

One adjustment between iterations of the course was for the instructor to be better prepared to intervene to help students get the most from the course. These opportunities for intervention occurred in two patterns.

One pattern was students’ persistence with their original concepts, even though redirecting to a new topic would have led to greater success. In considering these students’ choices to persist, the assignments did not place enough pressure on them to reconsider their ideas. One correction for the second teaching of the course was to make certain the assignments were distinct enough. Another response was to identify these students early on and stress to them the importance of incorporating new information, and the opportunity to change their topics. In the second iteration of the course, far more students changed topics over the duration of the course, leading to better presentations on topics that were well suited to the needs of the course.

The second pattern that needed addressing was some students’ struggles to fully participate in the course for a variety of reasons. In addressing this, the instructor sought to identify these students early and work closely with them to encourage full participation. Early invention was key, and the instructor used many modes to communicate with these students: informal conversations before and after class, emails, requests for office hours visits, and formal messages via the guidance system. These interventions proved successful for some students in improving attendance and participation, making these efforts highly effective uses of instructor time.

Next Steps

Going forward, the course’s data visualization creation activities will be more fully developed. Students enjoyed using websites with responsive data visualizations, such as the data visualization tool “GapMinder” from the late Hans Rosling (GapMinder, n.d.) as well as the previously mentioned Visualizing the Future module that allowed them to discuss effective data visualization. Via course feedback forms, multiple students requested that future instances dedicate more time to hands on activities involving data visualization and manipulation software. Students specifically requested activities that would allow them to work with Excel, spend more time creating maps in ESRI, or create infographics. Another common point of feedback from students was requesting more student-to-student interaction.

To allow for more student engagement with data visualization design and presentation, future instances will incorporate design work, potentially using Canva and Flourish.studio, Microsoft products such as Excel, or the Google suite of products. Canva is used to create infographics and other visual presentations, and Flourish is a data visualization tool. Canva now owns Flourish, so there may be benefits to integrating both into this course, though course integration would be limited to the free-to-use versions of these web-based applications.

Both hands-on activities and student interaction would fit better in class formats longer than 50 minutes. In response to this student feedback and a better understanding of the content, future iterations of the course will happen over a different schedule: a reduced number of classes in the course (from 14 weeks to 10 weeks) but an increase in the length of each class period from 50 minutes to 90 minutes. This shift will require some content to be eliminated, combined with other lessons, or conducted more quickly.

Future classes will also have a greater emphasis on data terminology, likely including quizzing students to reinforce their learning of the content. By helping students leave with a greater command of data and statistics vocabulary, they’ll be better prepared as readers of relevant statistical evidence as they matriculate into specific fields.

Conclusion

The course’s greatest success was the emphasis it placed on the fundamentals of searching for statistics and the consideration of the context from which they are produced. In the course feedback, students highly valued these skills, which they saw as both unaddressed in their education to that point and easily translatable to the rest of their coursework.

The focus on presentation skills and offering students a chance to practice those skills was seen by the students as a benefit. According to some students, there are few opportunities to practice these skills in their course work, particularly in the first few semesters, when class sizes tend to be large. Students also indicated that the course was their first opportunity to learn and practice proper citation.

Teaching this course has helped the instructor better understand students and their needs as they begin their journey at college. The different teaching context also provided an opportunity to develop new activities, including those that complement the information search process but are not scoped well for in-class instruction in others’ classes. Insights gained from this deep interaction with students then benefits other modes of interaction, such as one-on-one consultation and one-shot classroom instruction. Lastly, having the chance to watch students improve and getting to know them better adds to satisfaction at work.

References

Bauder, J. (Ed.), (2021). Data Literacy in Academic Libraries: Teaching Critical Thinking with Numbers. Chicago, IL. ALA Editions.

Bordelon, B. (Ed), (2020). Special issue on business and financial data: Introduction. Journal of Business & Finance Librarianship, 25(3–4), 103–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/08963568.2020.1827669https://doi.org/10.1080/08963568.2020.1827669

Calzada Prado, J. & Marzal, M. (2013). Incorporating Data Literacy into Information Literacy Programs: Core Competencies and Contents. Libri, 63(2), 123–134. https://doi.org/10.1515/libri-2013-0010https://doi.org/10.1515/libri-2013-0010

Caulfield, M. (n.d.). Sifting Through the Coronavirus Pandemic. Retrieved January 24, 2023, from https://infodemic.blog/https://infodemic.blog/

DataRobot. (n.d.). Data Science. Retrieved March 21, 2023, from https://www.datarobot.com/wiki/data-science/https://www.datarobot.com/wiki/data-science/

D’Ignazio, C., & Klein, L. F. (2020). Data Feminism. The MIT Press. https://data-feminism.mitpress.mit.edu/https://data-feminism.mitpress.mit.edu/

ESRI. (n.d.). Web GIS Mapping Software. ArcGIS online. Retrieved January 24, 2023, from https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-online/overviewhttps://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-online/overview

GapMinder. (n.d.) GapMinder Tools. Retrieved March 21, 2023, from https://www.gapminder.org/tools/#$chart-type=bubbles&url=v1https://www.gapminder.org/tools/#$chart-type=bubbles&url=v1

Getz, K. & Brodsky, M. (Eds.). (2022). The Data Literacy Cookbook. Chicago, IL. Association of College and Research Libraries.

Gibbons, S. (2016, July 31). Design Thinking 101. Retrieved April 5, 2023, from https://www.nngroup.com/articles/design-thinking/.https://www.nngroup.com/articles/design-thinking/

IDEO.org. (n.d.). Design Kit – Methods. Retrieved January 24, 2023, from https://www.designkit.org/methods.html.https://www.designkit.org/methods.html

Jefferson, C. O. (2020). Business and economics librarians’ insights on data literacy instruction in practice: An exploration of themes. Journal of Business & Finance Librarianship, 25(3/4), 147–174. https://doi-org.10.1080/08963568.2020.1847554https://doi-org.10.1080/08963568.2020.1847554

Lewis, M. (2009, February 13). The no-stats all-star. The New York Times Magazine, 26.

Lockhart P.R. (2018, January 11). What Serena Williams’s scary childbirth story says about medical treatment of Black women. Vox. Retrieved January 24, 2023, from https://www.vox.com/identities/2018/1/11/16879984/serena-williams-childbirth-scare-black-womenhttps://www.vox.com/identities/2018/1/11/16879984/serena-williams-childbirth-scare-black-women

Michigan State University - Undergraduate Education. (n.d.) First-Year Seminars. Retrieved January 24, 2023, from https://undergrad.msu.edu/programs/fyshttps://undergrad.msu.edu/programs/fys

Statista. (n.d.). Statista – Empowering people with data. Retrieved January 24, 2023, from https://www.statista.com/https://www.statista.com/

Visualizing the Future. (n.d.). Ethics in Data Visualization Workshop. Ethics in Data Visualization. Retrieved January 24, 2023, from https://visualizingthefuture.github.io/ethics-in-data-viz/https://visualizingthefuture.github.io/ethics-in-data-viz/