Editorial Note: The International Section of Ticker aims to connect and strengthen an international and global network of academic business librarians. We believe there is much we can learn from, and be inspired by, colleagues beyond our regional silos. This article offers a view into how one business librarian serves as a learning facilitator in the highly global instructional context of NYU Shanghai. It offers rich details of the particular context of his work, and his adaptive approaches in a variety of instructional settings. We hope that such practices are at once familiar and novel for new and seasoned academic business librarians in helpful ways.

HD McKay

Introduction

Instruction is a core component of any business librarians’ job responsibilities. The instructional role of a business librarian requires navigating many situations and applying important principles. Benjes-Small and Miller (2017) state that instruction librarians have eight hats in different situations: colleague, instructional designer, teacher, teaching partner, advocate, project manager, coordinator, and learner (pp. 40–41). In AACSB’s latest Guiding Principles and Standards for Business Accreditation (2020), one of the three categories is learner success, with an emphasis on curriculum, assurance of learning, learner progression, and teaching effectiveness and impact. In my experience as a Business librarian, I have taken on a variety of instructional roles and have applied these guiding principles to serve as a learning facilitator. I work with faculty and staff across campus to facilitate multicultural students’ learning throughout their whole university career.

Institutional Context

NYU Shanghai

As China’s first Sino-US research university and the third degree-granting campus of the NYU Global Network, NYU Shanghai seeks to cultivate globally minded graduates through innovative teaching, world-class research, and a commitment to public service. The student body currently consists of nearly 2,000 undergraduate and graduate students, half of whom are from China. Students from the United States and 70 other countries represent the other half of the student body. The faculty are also global in their backgrounds and scholarly interests. (NYU Shanghai, n.d.-h). All NYU Shanghai undergraduate students can earn a Bachelor of Arts or Bachelor of Science degree conferred by New York University—the same degree awarded at the New York campus—as well as a Chinese diploma recognized by the Chinese government. This qualifies graduates for opportunities both in China and around the world. The instructional language is English, and all non-Chinese students must become proficient in Mandarin Chinese. Students are required to complete a core curriculum in the liberal arts and sciences that encourages them to explore across disciplines and provides a solid grounding in key subjects before selecting an academic major. NYU Shanghai offers 19 different majors and a variety of minors. All students must spend at least one semester studying at one of NYU’s global sites and campuses, adding yet another international perspective to their education (NYU Shanghai, n.d.-g). The median class size is 12 students (NYU Shanghai, 2024), and the faculty-to-student ratio is 1:8 (NYU Shanghai, n.d.-a).

Business Programs

For undergraduate programs, students can choose three of 19 business program options, including Business and Finance, Business and Marketing, and Interactive Media and Business (NYU Shanghai, n.d.-e). Students declare a major when they’ve completed or enrolled in at least 32 credits, typically when registering in the fall of their second year (NYU Shanghai, n.d.-c). They can also pursue minors from NYU Shanghai or NYU New York by schools (NYU Shanghai, n.d.-f). According to the estimated data, 30–40% of students at NYU Shanghai choose business as their major.

For graduate programs, NYU Shanghai offers four degrees in business, jointly offered with the NYU Stern School of Business, including MS in Data Analytics and Business Computing (DABC), MS in Quantitative Finance (QF), MS in Marketing and Retail Science (MRS), and MS in Organization Management and Strategy (OMS) (NYU Shanghai, n.d.-d).

My Teaching Philosophy

Support Multicultural Learners.

NYU Shanghai enrolls students from over 70 countries, including at least 25% who are not from China or the United States. When demonstrating business databases, I sometimes use examples from different countries, for example international trading between Romania and Indonesia, beauty brands in India, and the beer industry in Vietnam. These examples demonstrate to students that the library's licensed databases provide extensive global coverage, enabling them to conduct reliable research about their home countries using authoritative sources. For some research topics, there may not be enough English language materials to complete their projects. It may be necessary to show them how to search for and evaluate the sources using non-English language options, e.g. peer-reviewed journals in Chinese, Korean and Japanese, and how to cite non-Latin language materials in English papers/reports/presentations.

Cultivate Critical Thinking in Business Information Context.

Students may not be familiar with the variety of source types in the business information landscape. They need to engage with primary sources such as annual reports, corporate policies, earnings call transcripts, promotional materials, and financial statement spreadsheets. They also need to practice evaluating the authority of different types of business information in specific contexts and purposes. Students need repeated practice in searching different source types, understanding the features and functions, and knowing how to use them critically and ethically. The knowledge and skills can benefit the students as lifelong learners throughout their career paths.

Encourage Open Discussion and Deep Engagement.

Students in a class may come from different majors and at different academic levels. By encouraging them to ask questions, join group discussion, and share what they learn with peers, we can show the students how they can expand their perspectives, identify any knowledge and skill gaps, and enjoy the process of learning in a collaborative way. Simulating realistic business learning experiences can help students focus on the strategies and tactics of real business environments, and train them to think like industry professionals, which help them understand the business situations and challenges they may encounter in workplaces.

Supporting Classroom Learning through Scenarios and Inquiry-based Library Instruction

Undergraduate students have opportunities to learn basic information literacy skills such as Boolean searching, subject-specific sources, and working with scholarly materials. These types of instruction are integrated within their required core courses in their first and second years: Social and Cultural Foundations, Writing, Mathematics, Science, Algorithmic Thinking, and Language (NYU Shanghai, n.d.-b). The Instructional Services Librarian at NYU Shanghai collaborates with faculty on the courses of English for Academic Purposes, Writing as Inquiry, Perspectives on the Humanities, and Global Perspectives on Society. They provide library course guides, tutorial videos, course-embedded workshops, and research consultations to help students develop these skills before I might engage with them in a business context.

As a business librarian, I reinforce or build on students’ prior learning related to information literacy skills. I collaborate with Business and IMB (Interactive Media and Business) faculty to customize business information literacy skills when students take business courses. I may mention some pieces of the basic search skills but focus more on the competencies of using business information sources.

My library instruction supports three distinct types of course-based learning needs:

Project-based: Students need to finish a research project individually or in groups and present it in finals week, e.g. Management & Organizations, Understanding Financial Technology, Pricing, Research for Customer Insights, Strategic Marketing in China, Dynamics of Innovation (Graduate).

Resource Identifying: Students need to find primary and/or secondary sources to support their writings, either for academic purposes or industry/company/consumer research purposes, e.g. Foundations of Finance, Introduction to Media Industries & Institutions, Information Technology in Business and Society, Global Beauty Industry, Entrepreneurship and Globalization.

Capstone: Students need to write a thesis, a capstone paper on a research project, or figure out a solution to a real-world problem, e.g. Business & Economics Honors Seminar, Senior Thesis Seminar, Interactive Media and Business Capstone, Marketing and Retail Science Capstone (Graduate).

From my observations and experiences of working with business faculty on these types of courses, I have identified two types of support that help students master specialized information literacy skills to finish their course assignments successfully. One type of support is scenario-based learning. This type is well-suited for lower-level students like first- and second-year business students, or students from other majors taking foundation business courses. Scenario-based learning is more accessible for students who don’t have much domain knowledge and are not clear about what information they will need. The other type of support is inquiry-based learning. This approach is more suitable for upper-level students like third and fourth-year business students, who need help to think more deeply or clearly about research topics they already have in mind.

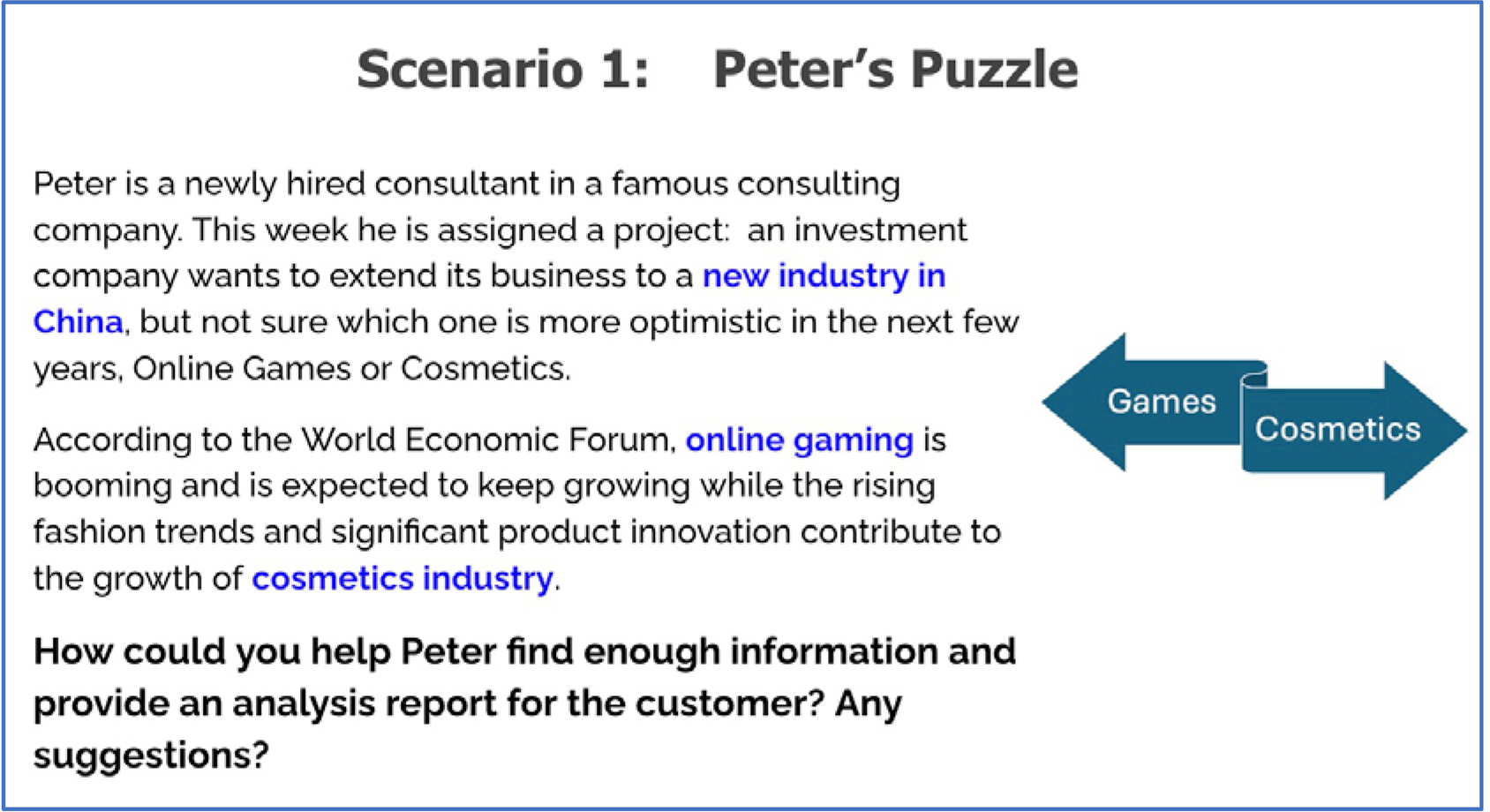

Scenario-based Learning: Lower-level Students

Scenario-based learning is a training strategy where learners are presented with work-related real-life situations that require them to make decisions and solve problems (Shreshtra, 2024). I used this learning strategy for the course Management & Organizations (Business Core Elective) in the fall semester of 2022, 2023, and 2024. Students need to present their final projects in groups. I designed three scenarios for industry, company, and consumer research and asked students to find key information to support the decision in each scenario. Before they worked on the in-class activities in groups with different roles, I first introduced source types in business with multiple examples from library databases. When they finished the activities, I demonstrated how I think about them and wrapped up with my search steps and tips.

I provided a handout that listed the following key elements that they could refer to:

Industry definition, similar industries, industry revenue, industry profit, industry businesses, industry employment, industry wages, industry outlook, the life cycle stage

Products & services, demand determinants, major markets, business locations, major players

Student feedback demonstrated enthusiasm for discovering the library's extensive collection of business databases, which offer more authoritative and valuable information than freely available websites and large language models. They appreciated the resources with high retail value, that were more reliable than search engines, open webpages, and even AI tools. There was one very positive comment in 2022 when I delivered this workshop for the first time, “I think this workshop (recording/content/slide) should be provided to all business students. It’s too important, but no one has told me before. Is it possible to make it mandatory for all junior business students?”

Through the in-class dialog, I learned a lot from the students. For example, when they searched for information, they had confidence and passion at first but felt frustrated and ‘stuck’ when overwhelmed with too many search results. I also learned that sometimes I might quickly gloss over what I considered ‘basic’ functions. For example, students wanted to more about navigating the interface and understanding the results page features. These were skills I has assumed that they mastered through library workshops that were embedded in their fundamental courses. There were additional concepts that remained unclear for students and had to be revisited. For example, they wanted to know easier ways to identify databases for different needs. The concept of source types in business (primary, secondary and tertiary) helped them understand the specialized functions of databases for different purposes. This categorization helped them select relevant resources for their research topics. When I looked back to the whole process of instruction and reviewed the workshop evaluation forms, it encouraged me to better address students’ real needs about “How to find the relevant information as fast and accurate as possible?" and develop their information literacy skills. This echoes one of their learning outcomes for business majors: Students will achieve an understanding of the role of business within our global society and be able to measure trade-offs to improve decision-making.

Inquiry-based Learning: Upper-level Students

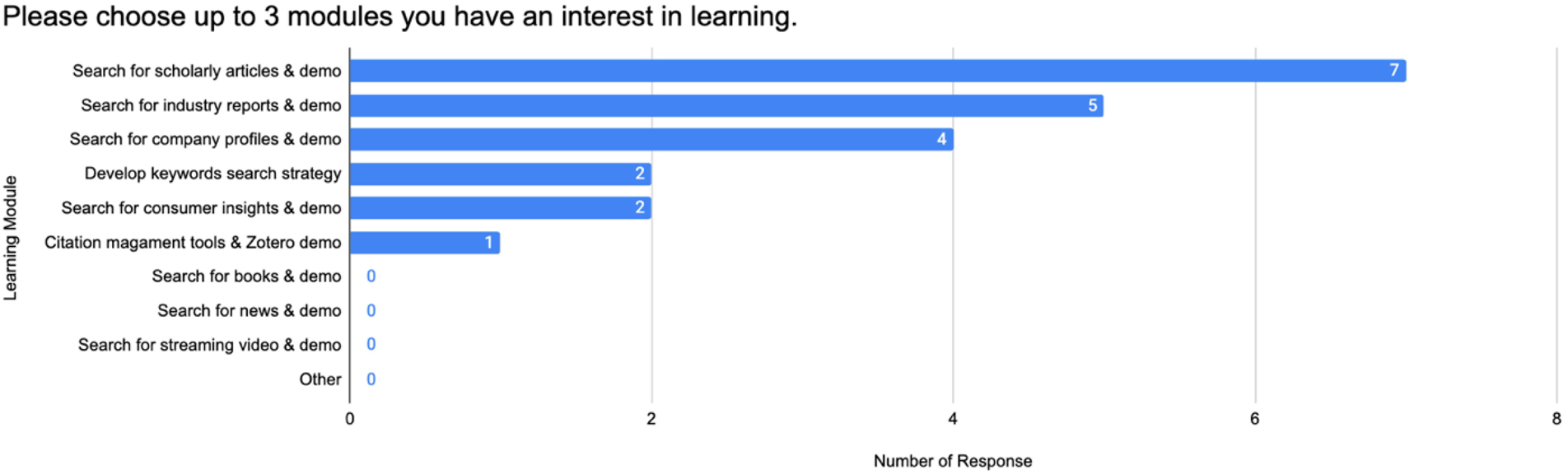

Inquiry-based learning encourages students to explore materials, ask questions, and share ideas in small groups guided by the course coordinators (Institute for Teaching and Learning Innovation, n.d.). I used this learning strategy for the course Understanding Financial Technology (an Interactive Media and Business elective) in the fall semester of 2021 and 2023, and the spring semester of 2022 and 2023. Students can choose to write research papers or design project prototypes individually. In this case, the workshop was delivered in the middle of the semester and most of the students had already discussed their research topics with the instructor, had basic knowledge of the key terms they would use in their research, and already had tried some searching before I met them. For these reasons, I focused my instruction on enhancing their information search and evaluation of their findings. To better understand the specific information literacy gaps of these students, I used a quick poll before the workshop. With the instructor’s help, I asked the students to choose up to three modules they would like to prioritize for the library workshop.

Using the poll results, I demonstrated the top three types of library databases and asked them to find 1–2 sources and describe how they used them for their research topics. The prompts I provided are below:

What database did you choose?

Why did you choose this database?

What search strategy did you use for your research topic?

List one resource from the database, including the title, author, publisher, publication date, etc.

List reasons that you think this resource can serve your research purpose.

The in-class activity with guided instruction is an important step for working towards self-directed learning. An AACSB article emphasized that to pursue learning through a self-directed discovery journey, students collected data from various resources to analyze the details (for example, trends, formulas, general concepts, and variables) of the business problem and taught themselves the relevant information to answer questions and critically evaluate their hypotheses (Kotee & Nguyen, 2021). Self-directed learning is crucial for helping students meet one of the outcomes for the Interactive Media and Business major: Develop critical thinking skills that facilitate analysis and placement of their work within various research contexts (i.e., cultural, historical, aesthetic, business, and/or technological). In this way, building opportunities for self-direction and choice can help students further develop and build these skills for thesis development and for drawing research conclusions.

From workshop student feedback, I was glad to see the session helped students become aware of the full range of library resources and helped them explore multiple databases to find relevant information.

“Especially if you are a business student, the NYU Business Library is extremely helpful as it has almost every type of business information out there. Start with broad searches and add more keywords to get more specific.”

“Do not just google studies/resources you need, use the library, as much as you can. We have access to many resources.”

“This workshop is conducive to building a comprehensive view of research. The Best Bets booklet is very helpful, check it!”

The course-embedded library sessions are a critical part of my instruction portfolio. Without them, students may not have the opportunity to learn the skills of searching for business information, guided by a subject expert. However, solely relying on these opportunities can be limiting in finding the ideal timing for students. For example, when students need to use the library resources for their capstone projects in their fourth year, it may be too late to prepare them with the essential skills. One senior student provided feedback after attending one workshop session, stating, “I feel this workshop would have been very useful to be introduced in freshman year.” For this and other reasons, the other half of my instruction portfolio takes place outside of the curricular classroom.

Supporting Learning Beyond the Classroom

I use extra-curricular instruction to both bridge the gaps within the curricular instruction and support lifelong learning. Course-embedded library sessions mostly focus on marketing and management, and few on finance and other topics. I have tried to fill in the gaps to develop instruction for other topics such as hands-on skills for career planning/development. Students have emailed the library several times about what resources they could continue to use after their graduation and expressed a desire for library tools with career information. For example, one student mentioned a key takeaway from the NYU Alumni Executive Mentor Program: reading financial publications, research reports, and industry blogs expanded her knowledge and allowed her to engage in meaningful conversations and contribute more effectively to her work (The Center for Career Development, n.d., p.8).

The three main ways of supporting students’ development out of the classroom are library pre-scheduled workshops, business competitions, and one-on-one research consultations.

Pre-scheduled Workshops

NYU Shanghai Library offers many workshops. These sessions range in topics from the basics of using the library to subject-based search skills, to practical use of tools and research-based knowledge and skills. The topics are developed from commonly asked questions at library reference desks, online chats, emails, and one-on-one research consultations. In business, I delivered topics in the following areas:

Industry Reports (I): Basic Elements

Industry Reports (II): Industry Classification

Company Profiles (I): Public Companies

Company Profiles (II): Private Companies

Business News

Popular News

Career Resources

Business Information 101

Financial Data

Analyst Reports

Alumni Resources

Pre-scheduled workshops are usually independent of courses and research projects. They are open to everyone who has an interest in navigating library resources on the topic. Based on past registration and attendance data, I have learned that students from majors that use a lot of data for their course work (such as economics, mathematics, data science, and computer science, or even undeclared students) are very interested to explore what datasets are available in the library’s business collection to support their learning and research projects in the future. The workshops are delivered mostly in the late afternoon or evening so that more students can attend, and the average attendance is between 10 and 12 students. Considering the small class sizes at the institution previously mentioned, this is an encouraging participation rate.

Business Competitions

Business competitions simulate real business environments to mimic real-world problems and challenges. The AACSB states that “experiential learning elements replicate what students will face when they are thrust into difficult, uncomfortable situations in the corporate environment and must produce tangible deliverables” (Keller & Jain, 2023). At NYU Shanghai, the Center for Career Development is responsible for hosting most of the business competitions on campus and collaborating with regional, national, and global organizers to select candidates. Competitions include the Bloomberg Global Trading Challenge (training by Bloomberg Analyst), NYU Shanghai Consulting Case Competition, and ĽOréal Brandstorm.

Usually, on the kick-off day or before the registration deadline, I am invited to deliver a competition-based library workshop for all participants. I showcase how to interpret the theme from a business librarian’s perspective and demonstrate how to choose relevant databases and develop effective search strategies to gather useful information. I help them prepare by using resources to develop background knowledge and insights from industry experts and professionals. The average number of attendees has ranged from 39 to 65. In addition to synchronous instruction, I have created a library research guide page for Students Competitions (NYU Shanghai Library, n.d.-a). Students can find information about the background, timeline, registration information, and supporting resources (official user guide, tutorial videos, books, journals, cases, reports, etc.). Participating in these competitions has allowed me to see just how valuable business research skills are in professional life. For example, on a final presentation day, one of the competition judges was an NYU Shanghai alumni working at a consulting company. He told all the participants that the skill of searching and evaluating information was one of the most important skills in his daily work, and that it was certainly not limited to academic research. He shared the three evaluation criteria below for students who want to make market plans like professionals and stand out among others:

Feasible Plan: Is it practical and actionable to implement the plan? Students can read cases and reports to get a full picture of the industry, company, and consumers and think about the specific topic they will research on.

Professional Thinking: Before making any analysis, students should know the rationale, framework, and theoretical structure behind the topic/theme. A successful market plan is concluded on a reasonable and solid market hypothesis and inference.

Reliable Source: Authoritative data and trustworthy reports lay the foundation for students to build a model and predict a future market to see if there will be an opportunity to invest.

I introduced students to market research resources at the workshop. I did so in a way that they could understand their authoritativeness in a business information context. This approach helped the students develop habits of thinking like industry professionals.

Research Consultations

When students don’t have any opportunities to attend course-embedded or extracurricular workshops or have more personalized questions on course assignments and research projects, they may seek assistance through one-on-one research consultations. Each student has their pain points based on their past learning experiences, which can be deeply impacted by their different cultural and educational backgrounds. The instruction during research consultations is similar to in-class instruction, but more customized to a personal need. By asking them questions and guiding them on how to deconstruct their research questions and use library resources step by step, students can mitigate information anxiety when they encounter overloaded information on the internet and library database lists.

For example, one student was interested in a new trend related to eVTOL Aircrafts and wished to write a market analyst report for China. Because the term was quite new, he tried a few sources such as Google, ProQuest, McKinsey, and local newspapers, but didn’t know where else to search for the relevant information to support the report. I worked with him to list a few synonyms, such as, Electric VTOL, eVTOL Aircraft, Electric VTOL Aircraft, electric vertical take-off and landing aircraft, electric aircraft, aerial vehicle, (advanced) air mobility, urban air mobility, flying taxi, 电动垂直起降航空器 (electric vertical take-off and landing aircraft), 电动飞机 (electric airplane) in a syndetic structure and showed the types of sources in business and how they functioned for multiple purposes. I asked him to conduct the search on his own laptop under my guidance. Like many of my students, after several rounds of testing, the student was able to master the basic skills in how to use the advanced search with Boolean operators and narrow down the search result with narrower terms and filters for industry classification/category, geographic location/region, and generation/demographics to meet his project’s research requirements. I could also tell that it was very helpful for the students to know that, as a business librarian, I also needed time to think about and try a few resources when I saw a new term/concept/topic. This insight brought them confidence and patience to think over their concepts and try different strategies to fix the problems they encountered.

Moreover, if I receive consultations on the same/similar topics multiple times, I will consider building a guide page on that topic, such as Electric Vehicle (NYU Shanghai Library, n.d.-b) in the research guide Business in Contemporary China.

Future Goals Building on Past Success

In the past four years, I have collaborated with faculty in eighteen courses, reaching 721 students. When I looked back to my first semester in this role, I only got two requests for course-embedded sessions. Today, I might receive 8–10 requests for one semester. When you build trust with business faculty, their word-of-mouth marketing brings more requests for library support.

Learning how to support students in and out of the classroom has been my primary focus since pivoting from a role as an acquisitions librarian to a business librarian. I learned a lot from collaboration with faculty and staff members and students evaluations and feedback. My next goal as part of my role as learning facilitator is to take a more systematic approach and create a framework that combines ACRL Threshold Concepts (Association of College and Research Libraries, 2015) with Business Research Competencies (Reference and User Services Association, 2019) and map it to the business curriculum at NYU Shanghai.

Additionally, I plan to work with more departments, like Academic Advising and Graduate Program Managers, to better understand student learning needs in the age of digital transformation and AI.

References

AACSB. (2020). Guiding Principles and Standards for Business Accreditation. https://www.aacsb.edu/educators/accreditation/business-accreditation/aacsb-business-accreditation-standardshttps://www.aacsb.edu/educators/accreditation/business-accreditation/aacsb-business-accreditation-standards

Association of College and Research Libraries. (2015). Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education. https://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframeworkhttps://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework

Benjes-Small, C., & Miller, R. K. (2017). The New Instruction Librarian: A Workbook for Trainers and Learners. ALA Editions.

Institute for Teaching and Learning Innovation. (n.d.). Case, scenario, problem, inquiry-based learning. The University of Queensland. Retrieved January 9, 2025, from https://itali.uq.edu.au/teaching-guidance/teaching-practices/active-learning/case-scenario-problem-inquiry-based-learninghttps://itali.uq.edu.au/teaching-guidance/teaching-practices/active-learning/case-scenario-problem-inquiry-based-learning

Keller, E. D. W., & Jain, R. (2023, April 17). Two Approaches to Experiential Learning. AACSB Insights. https://www.aacsb.edu/insights/articles/2023/04/two-approaches-to-experiential-learninghttps://www.aacsb.edu/insights/articles/2023/04/two-approaches-to-experiential-learning

Kotee, T., & Nguyen, C. (2021, July 16). Instruction vs. Discovery Learning in the Business Classroom. AACSB Insights. https://www.aacsb.edu/insights/articles/2021/07/instruction-vs-discovery-learning-in-the-business-classroomhttps://www.aacsb.edu/insights/articles/2021/07/instruction-vs-discovery-learning-in-the-business-classroom

NYU Shanghai. (n.d.-a). Admissions. Retrieved December 3, 2024, from https://shanghai.nyu.edu/admissionshttps://shanghai.nyu.edu/admissions

NYU Shanghai. (n.d.-b). Core Curriculum. Retrieved December 3, 2024, from https://shanghai.nyu.edu/curriculum/core-curriculumhttps://shanghai.nyu.edu/curriculum/core-curriculum

NYU Shanghai. (n.d.-c). Declare or Change a Major. Retrieved December 3, 2024, from https://shanghai.nyu.edu/advising/academic-procedures/declare-or-change-a-majorhttps://shanghai.nyu.edu/advising/academic-procedures/declare-or-change-a-major

NYU Shanghai. (n.d.-d). Graduate and Advanced Education. Retrieved December 3, 2024, from https://shanghai.nyu.edu/graduate-admissionshttps://shanghai.nyu.edu/graduate-admissions

NYU Shanghai. (n.d.-e). Majors. Retrieved December 3, 2024, from https://shanghai.nyu.edu/academics/majorshttps://shanghai.nyu.edu/academics/majors

NYU Shanghai. (n.d.-f). Minors. Retrieved December 3, 2024, from https://shanghai.nyu.edu/academics/minorshttps://shanghai.nyu.edu/academics/minors

NYU Shanghai. (n.d.-g). Undergraduate Studies. Retrieved December 3, 2024, from https://shanghai.nyu.edu/undergraduatehttps://shanghai.nyu.edu/undergraduate

NYU Shanghai. (n.d.-h). Who We Are. Retrieved December 3, 2024, from https://shanghai.nyu.edu/abouthttps://shanghai.nyu.edu/about

NYU Shanghai Library. (n.d.-a). Student competitions research guide page. Retrieved January 9, 2025, from https://guides.nyu.edu/c.php?g=277131&p=9466159https://guides.nyu.edu/c.php?g=277131&p=9466159

NYU Shanghai Library. (n.d.-b). Electric Vehicle research guide page. Retrieved January 9, 2025, from https://guides.nyu.edu/c.php?g=757127&p=9735323https://guides.nyu.edu/c.php?g=757127&p=9735323

NYU Shanghai. (2024). Facts and Figures. https://shanghai.nyu.edu/about/facts-and-figureshttps://shanghai.nyu.edu/about/facts-and-figures

Reference and User Services Association. (2019). Business Research Competencies. https://www.ala.org/sites/default/files/rusa/content/resources/guidelines/business-research-competencies.pdfhttps://www.ala.org/sites/default/files/rusa/content/resources/guidelines/business-research-competencies.pdf

Shreshtra. (2024, September 18). Scenario Based Learning - The Next Big Thing in Corporate Training! Animaker. https://www.animaker.com/hub/scenario-based-learning/https://www.animaker.com/hub/scenario-based-learning/

The Center for Career Development. (n.d.) NYU Alumni Executive Mentor Program: 2022–2023 Mentee Story Book. NYU Shanghai. Retrieved January 9, 2025, from https://cdn.shanghai.nyu.edu/sites/default/files/22-23_mentee_storybook.pdfhttps://cdn.shanghai.nyu.edu/sites/default/files/22-23_mentee_storybook.pdf