Research Question:

What are the recommendations for governmental and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) to address parental/guardian disclosure through explanation of benefits (EOBs) of adolescents who are taking PrEP and are insured under a parent or guardian?

Introduction

Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) is a once-daily prevention medication taken orally to prevent HIV infection upon exposure. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine as PrEP was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2012 (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2012). The pharmaceutical company Gilead Sciences marketed PrEP as Truvada. Since then, Gilead Sciences formulated another option for PrEP known as Descovy, which the U.S. FDA approved as PrEP in 2019 (U.S. Food & Drug Administration, 2019).

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recommends PrEP for those who are susceptible to HIV infection from sex or injection drug use (CDC, 2021). Recently, new recommendations from the CDC in 2021 expanded criteria for accessing PrEP, which encompasses more versions of PrEP, including generic options, where previously only brand names Truvada and Descovy were available to clients (Buhl, 2021).

In 2015, the CDC estimated the number of individuals at increased susceptibility to HIV who would be eligible for PrEP was around 1.1 million adults, capturing key populations, such as the LGBTQ+ community, young Black men who sex with men, and Black women (Huang, Zhu, Smith, Harris, & Hoover, 2018). Since PrEP’s introduction as Truvada, the percentage of people on PrEP has increased dramatically. In 2012, there were approximately 8,768 PrEP users, while data from 2016 shows 77,120 PrEP users (AIDSVu, 2018). The CDC projects that 44% of African Americans and 25% of Latinos from these key populations could potentially benefit from PrEP, but data showed only 1% of African Americans and 3% of Latinos were prescribed PrEP (Rosenberg, 2018).

The scope of this literature review defines adolescents as individuals from 13 to 26 years old. In 2017, adolescents aged 13–24 accounted for 21% of the new HIV infections in the United States (Hosek & Henry-Reid, 2020). Compared to the national average (14.1 per 100,000) and White counterparts (10.8 per 100,000) in this age group, Black (95.4 per 100,000) and Latino (31.3 per 100,000) populations saw greater rates of HIV infection. PrEP is an effective tool for those 18 years and older, and physicians can prescribe PrEP to those under the age of 18 to reduce the number of new HIV infections in adolescent populations (Harriet Lane Clinic, n.d.). However, much of the research for sexual and reproductive health has left out 13- to 26-year-olds in PrEP access and implementation programs.

Between 2013 and 2017, PrEP awareness increased in US Men who have sex with Men (MSM) population (Sullivan et al., 2020). For those aged 18–24, the percentage of those who knew or had heard of PrEP as a method of HIV prevention increased by 42.2%. The general willingness to use PrEP in adolescents increased after 2013 but stabilized at around 60%. More recently, Wood et al. found limited awareness of PrEP in adolescents (Wood, Lee, Barg, Castillo, & Dowshen, 2017). Current research has focused primarily on MSM populations, with few studies in the United States looking into PrEP awareness among trans-identifying youth and adolescent females. Studies thus far conducted in trans-identifying youth and adolescent females have a relatively small sample size compared to MSM or Black American populations (Horvath, Todd, Arayasirikul, Cotta, & Stephenson, 2019; Yusuf, Fields, Arrington-Sanders, Griffith, & Agwu, 2020). Black and Latinx adolescents in high HIV prevalence areas show a need for distinct prevention strategies to increase awareness of and willingness to use PrEP (Taggart, Liang, Pina, & Albritton, 2020).

The Society of Adolescent Health and Medicine pointed to limited provider knowledge and capacity to assess HIV susceptibility in adolescents as a barrier to adolescents receiving comprehensive help (Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine, 2018), such as the prescription of PrEP. Most adolescent health providers (93.2%) in a 2018 survey said that they had heard of PrEP. Even so, providers’ willingness to prescribe PrEP for adolescents remained well below their awareness at 64.8% and 77.8%, respectively. The willingness to prescribe PrEP is seen in US pharmacy data. From 2012 to 2017, only 2,590 (~1.5%) prescriptions for PrEP were among youth, 18 years of age and younger. For those 18–24 years old, the percentage climbed slightly to a range of 9.5–15.4% of all total prescriptions of PrEP (Paer, Mattappallil, Bentsianov, & Finkel, 2020).

When PrEP was approved by the FDA in 2012, legal and policy researchers aimed to understand barriers to accessing PrEP under current state laws. An analysis from all 50 states found that no laws specifically prohibited minors’ access to PrEP (Culp & Caucci, 2013). However, minors’ ability to consent to PrEP in most states without parental consent remains unclear. As of 2021, the CDC has listed only three states (Connecticut, Iowa, and Maryland) that have specific provisions for a minor’s ability to consent for HIV PrEP (CDC, 2021). Hence, there are few inherent legal barriers to accessing PrEP.

Certain states allow minors to have the right consent to STI/HIV testing (Minors’ Authority to Consent to STI Services, 2017). Additionally, minors can consent to the treatment of STIs/ HIV. However, upon test result outcomes and creation of a care plan in some states, a provider can disclose medical information to a parent or guardian without the consent of the minor (English & Ford, 2004). Depending on the place of prescription, a minor’s ability to consent varies from state to state. For instance, if a provider prescribes PrEP at a Title XI clinic in Michigan, a minor does not need parental consent. On the other hand, a minor will require parental consent if the provider prescribes PrEP in a non-Title XI clinic (MDHHS, n.d.). Based on the location of a minor, a Title XI clinic may not be a feasible option for the prescription of PrEP without parental consent based on state jurisdiction. This complex categorization of consent and disclosure becomes even more challenging when one considers how explanation of benefits (EOBs) may hinder PrEP uptake for adolescents. EOBs are a statement sent by an insurance company to the covered individuals explaining what treatments and/or services were paid by insurance (HealthInsurance.Org, 2022).

The purpose of this article is to conduct a systematic review of the literature to inform policy on PrEP disclosure for adolescents in the United States. I separated the materials for this literature review into two searches. The goal of the first search was to find articles within the current literature that discuss insurance coverage as it relates to PrEP, and the second search aimed to find what resources exist for providers of PrEP on PrEP and insurance coverage.

Methods

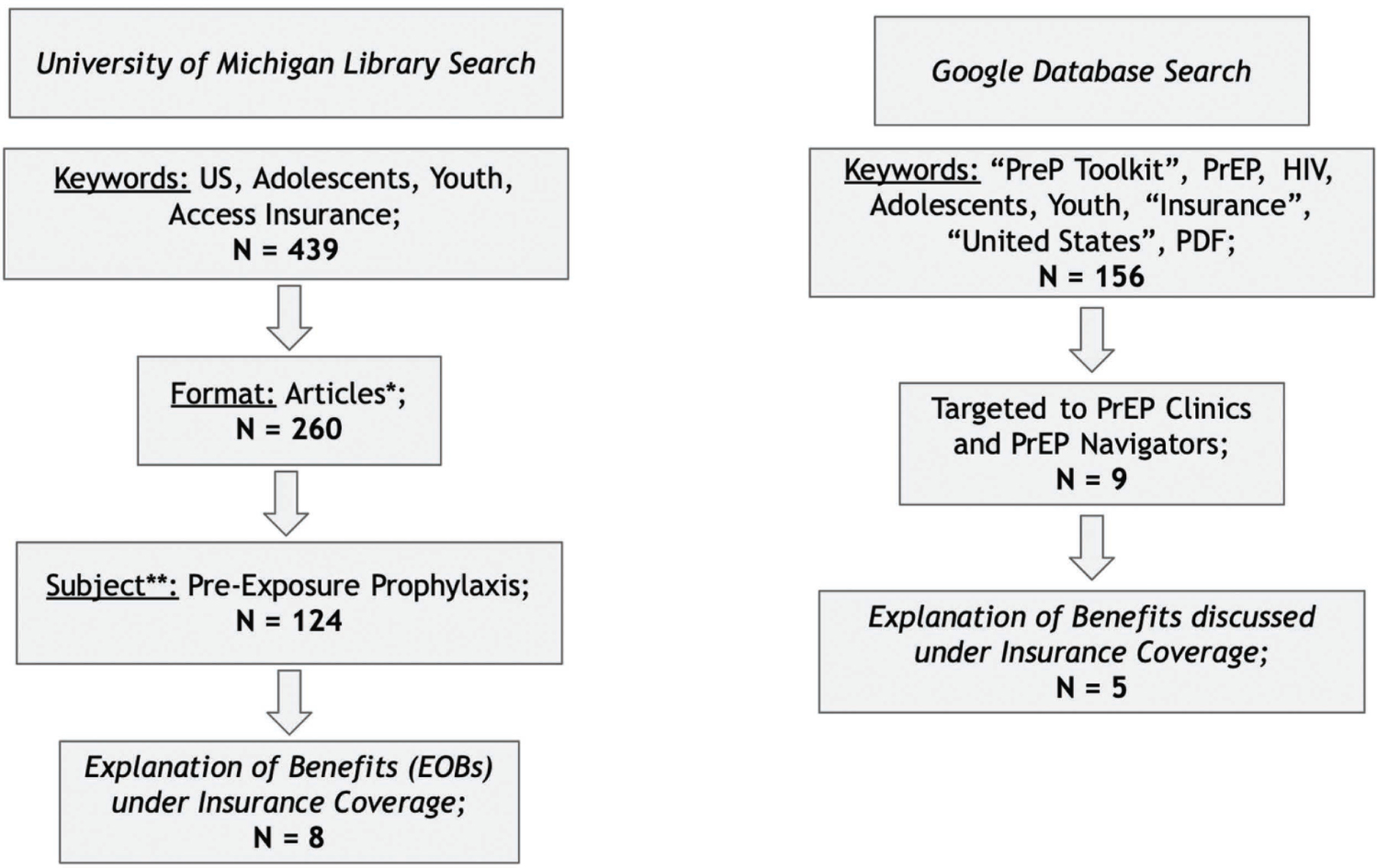

There were two main searches for this literature review. This first search utilized the University of Michigan Library Search, which is built in three main layers, from user interface to indexes to data sources. The keywords of the aggregate initial search of articles included “Adolescents”, “Youth”, “Access”, “Insurance”, “HIV”, and “PrEP”. The source format from the aggregate search was narrowed to include only articles. We selected “Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis” as a subject to filter out articles that did not address PrEP. Applicable articles contained in the literature review included EOBs under insurance coverage.

The second search looked for materials that were used in a clinical or community-based organization setting surrounding PrEP and insurance coverage. We utilized the Google Search engine. The keywords of the aggregate initial search included “PrEP Toolkit,” “PrEP”, “HIV”, “Adolescents”, “Youth”, “Insurance”, “United States”, and “PDF”. The selection process from this first search decided whether the material included PrEP Clinics or PrEP Navigators. A final review filtered out any material that did not discuss EOBs under insurance coverage.

I filtered the articles based on content relevancy to the literature review through a qualitative ranking process. The process included a numerical ranking on a scale of 1–3 and a short explanation to justify the article’s relevance to the research question. Figure 1 details the filtering of articles and materials in the literature review process.

From research on PrEP access, I identified the categories of barriers facing adolescents. Then, I contextualized the barriers in current PrEP usage/uptake in adolescent populations in the United States. Conversely, information from the PrEP toolkits outlined possible solutions to problems surrounding parental/guardian disclosure in EOBs. I devised possible solutions, elaborating on their implementation on an organizational and policy level.

Results

The final set of articles from both searches (n = 13) included two main categories of papers. In the first, a total of eight papers from the research literature discussed PrEP access, specifically insurance coverage for minors and adolescents (Kay & Pinto, 2020; Saleska et al., 2021; Mullins & Lehmann, 2018; Fisher, Fried, Puri, Macapagal, & Mustanski, 2018; Macapagal, Nery-Hurwit, Matson, Crosby, & Greene, 2021; Sinead et al., 2016; Moskowitz et al., 2020; Macapagal, Kraus, Korpak, Jozsa, & Moskowitz, 2020). In the second search, five clinic or PrEP navigator materials discussed EOBs in PrEP toolkits (MDHHS, n.d.; AIDS Education & Training Center Pacific, 2017; PleasePrEPme.org, 2020; Department of Health District of Columbia, n.d.; Para, 2020; AIDS Free Pittsburgh PrEP Subcommittee, 2017; HIV/AIDS Section – Medical Team, 2016; New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute, 2020; U.S. Department of Labor, Employee Benefits Security Administration (EBSA), n.d.).

Discussion

Insurance Navigation as a Barrier to Access PrEP

In 2020, Kay and Pinto discussed anticipated barriers to PrEP implementation from 2007 to 2017, such as parental consent or approval for PrEP prescription (Kay & Pinto, 2020). However, depending on the type of insurance an individual has, the magnitude of these barriers is different. For instance, those who are covered with state/federal government insurance, such as Medicaid, may not face difficulties of cost but face problems of eligibility and state-specific requirements (Guth, Garfield, & Rudowit, 2020). Because adolescents who qualify for Medicaid or Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) are the sole recipients of insurance services, EOBs are not directed to parents/guardians, lessening concern around disclosure. Hence, the scope of this review solely focuses on private insurance.

Several papers on HIV prevention cite concerns of insurance for adolescents pursuing PrEP. A cross-sectional analysis from New Orleans and Los Angeles on the use of PrEP among adolescent cisgender men found insurance might affect the access to PrEP in terms of the client–provider relationship (Saleska et al., 2021). Also, the researchers noted that insurance coverage more broadly is a barrier to PrEP access. In a more diverse population of adolescents and young adults, including broader gender, racial, and ethnic categories, studies found that insurance and disclosure remained a difficulty for PrEP access, even when health coverage was present (Mullins & Lehmann, 2018; Fisher et al., 2018). For sexual and gender minority adolescents assigned male at birth, there were concerns of parental involvement in the PrEP process as it relates to insurance (Macapagal, Nery-Hurwit, Matson, Crosby, & Greene, 2021). The ethical concern of EOBs disclosing the use of PrEP to a parent or guardian has been paired with equal concerns that high co-pays and insurance navigation can impact adolescent access to PrEP (Sinead et al., 2016). On top of this, perceptions from adolescents suggest an inability to navigate insurance and healthcare coverage systems without support (Moskowitz et al., 2020). For those under the age of 18, more stringent resource allocation in terms of health insurance and finances cites a problem of coverage for minor adolescents (Macapagal et al., 2020). Generally, insurance coverage is limited for sexual minority adolescents, making PrEP inaccessible on multiple fronts (Culp & Caucci, 2013; Huebner & Mustanski, 2020). PrEP may be an effective tool at preventing HIV, but insurance has shown in multiple ways how access remains limited.

PrEP Navigation Resource Evaluation

The scope of research on accessibility to PrEP in adolescent populations has primarily focused on identifying what barriers exist. However, there is limited research on practical solutions for community-based organizations (CBOs) and NGOs on the matter of EOBs for adolescent clients as discussed earlier. In other words, the research has clearly demonstrated that disclosure of the use of PrEP by an adolescent through an EOB to their parent or guardian is a defined barrier to access. However, there are no present concrete solutions offered to mitigate these negative outcomes.

There are possible solutions to this logistical problem with PrEP and insurance in legal discourse. The Guttmacher Institute released “Protecting Confidentiality for Individuals Insured as Dependents” in early September 2021 (Public Policy Office, 2021). The outline provides what innovative solutions states in the United States have implemented to address border confidentiality concerns. In 2021, “14 states have provisions that serve to protect the confidentiality of individuals as dependents.” Some states like Massachusetts, New York, Washington, and Wisconsin have protections specific to EOBs, which allow insurers to mail an EOB directly to the patient instead of the policyholder. Some states include broader confidentiality provisions under the protections for minor dependents, outlining that an “insurer may not disclose private health information, including through an EOB, without minor’s authorization.”

The complex matter of insurance disclosure is discussed in PrEP toolkits meant for clinics, including providers of PrEP and PrEP navigators. A PrEP navigator “provides intensive care coordination, support and services to HIV negative individuals who require assistance in accessing and remaining in PrEP care” (POZ, 2020). The National HIV and PrEP Navigation Landscape Assessment outlined problems with EOBs at a specific clinic, where there were concerns of sexuality of disclosure (NMAC Capacity Building Division, 2017).

In the state of Michigan, the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS) PrEP Provider Toolkit establishes different scenarios through Getting PrEPped on how to approach insurance coverage (MDHHS, n.d.). For instance, if a patient is insured and can cover the costs for PrEP, there may be assistance programs to cover co-pays and deductibles. Other PrEP toolkits have done similar case studies on navigating insurance (AIDS Education & Training Center Pacific, 2017; PleasePrEPme.org, 2020). A PrEP toolkit from DC highlights limitations to accessing PrEP for adolescents, including insurance coverage and EOB (Department of Health District of Columbia, n.d.). However, there are no counterpoints to overcoming this hurdle. In the mix of PrEP toolkits, a majority focus on PrEP and insurance but leave out how to address or handle EOB with adolescent clients (Para, 2020; AIDS Free Pittsburgh PrEP Subcommittee, 2017; HIV/AIDS Section - Medical Team, 2016; New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute, 2020).

Policy Practice to Address Disclosure

Solutions at the interpersonal and organizational level with PrEP navigators and CBOs/NGOs, respectively, have demonstrated innovative approaches to addressing the challenges that come with EOBs surrounding PrEP. Policy-level initiatives need to affect a broader demographic of adolescents. A policy change will create standards of public health measures that insurance companies must comply with or face violations at the state level (U.S. Department of Labor, Employee Benefits Security Administration (EBSA), n.d.).

A model of legislative success comes from the State of California. Outlined in the civil code division of persons, confidentiality of medical information applies to disclosure of medical information by providers (Civil Code -Civ Division 1. Persons [38–86] Part 2.6 Confidentiality of Medical Information [56–56.37], 2014). This legislative action encompasses not only insurance companies but also medical providers, such as physicians, which would otherwise have the ability in some states to disclose the use of PrEP by a minor to their parent or guardian. The policy change allows recipients insured by a primary policyholder, such as a parent, guardian, or spouse, to request that sensitive medical information not be disclosed to the primary policyholder.

As outlined by policy scholars, the state of California now clarifies the term “endanger” that federal HIPAA privacy regulations leave undefined as “fears that disclosure of his or her medical information could subject the [individual] to harassment or abuse” (Khan, 2015). The civil code outlines that covered individuals do not need evidence of endangerment or explanations as to why they feel disclosure warrants endangerment, such as physical demarcations or emotional accounts of trauma.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of California developed the website MyHealthMyInfo.org to clarify the process of submitting a confidential communications request (ACLU of Northern California & ACLU of Southern California, 2021). The website provides the necessary form to fill out along with different language options. The drop-down menu enables users to find their healthcare provider or insurance company, which opens a new page for the request filing process for that insurance company.

At the national level, the Protect Our Ability to Counter Hacking (PATCH) act attempted to create a Vulnerability Equities Review Board that would outline policy to address personal information in technology, including health (Lieu, 2017). The PATCH act was brought before the house but was never passed.

In a recent Biden administration policy change, guidance on the Affordable Care Act Implementation Part 47 outlined new PrEP coverage guidelines for insurance companies (Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services (HHS), and the Treasury, 2021). This implementation has been interpreted that an insurer must not charge co-pays, coinsurance, or deductible payments for the quarterly clinic visits and lab tests required to maintain a PrEP prescription (Ryan, 2021). However, as compliance lags from insurance companies to remove costs of PrEP, they at the very least cannot deny PrEP prescription and subsequent maintenance services to policyholders (Saloway & Benk, 2021). In essence, this would alleviate the burden of costs related to PrEP, but it is unclear whether such implementation would impact EOBs and disclosure.

Conclusion

The importance of providing PrEP for adolescents who are susceptible to HIV is critical to achieving broader goals of ending the HIV epidemic. However, many barriers exist for adolescents who would like to start PrEP, including cost associated with PrEP, geographic location, and provider competency. As this literature review suggests, EOBs that could disclose sensitive information to policyholders, such as parents or guardians, are an additional barrier to accessing PrEP. A small fraction of states have laws that protect minors in this situation, but few are comprehensive enough to avoid endangering the adolescent/minor. This literature review recommends that states attempt to review and implement changes to civil or public health codes that would further define HIPAA’s terminology of “endanger” and hold insurers accountable to EOB disclosures. Furthermore, states can facilitate this process holistically with NGOs and CBOs to essentially eliminate the barrier of adolescents seeking PrEP who are covered under another policyholder’s private insurance. There are, without a doubt, immensely valuable outcomes that could lie on the horizon with policy changes on EOBs that would empower individuals to access PrEP without fear of losing their agency.

References

ACLU of Northern California & ACLU of Southern California. (2021). Keep it confidential. MyHealthMyInfo. Retrieved from https://myhealthmyinfo.orghttps://myhealthmyinfo.org

AIDS Education & Training Center Pacific. (2017, February). PrEP toolkit contents. AETC Pacific Bay Area | North Coast. Retrieved from https://paetc.org/about/local-partners/bay-area-north-central-coast/https://paetc.org/about/local-partners/bay-area-north-central-coast/

AIDS Free Pittsburgh PrEP Subcommittee. (2017, September). PrEP toolkit for providers. AIDS Free Pittsburgh. Retrieved from http://www.aidsfreepittsburgh.org/perch/resources/prep-toolkitupdated-10-5-17.pdfhttp://www.aidsfreepittsburgh.org/perch/resources/prep-toolkitupdated-10-5-17.pdf

AIDSVu. (2018, March 18). Mapping PrEP: First ever data on PrEP users across the U.S. Awareness Days. Retrieved from https://aidsvu.org/prep/https://aidsvu.org/prep/

Buhl, L. (2021, July 6). New PrEP guidelines aim to expand access, but uptake will depend on clinicians. The Body Pro. Retrieved from https://www.thebodypro.com/article/new-prep-guidelines-expand-access-uptake-depend-on-clinicianshttps://www.thebodypro.com/article/new-prep-guidelines-expand-access-uptake-depend-on-clinicians

CDC. (2021, January 8). State laws that enable a minor to provide informed consent to receive HIV and STD services. Policy, Planning, and Strategic Communication. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/policies/law/states/minors.htmlhttps://www.cdc.gov/hiv/policies/law/states/minors.html

CDC. (2021, June 11). Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). Preventing New HIV Infections. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/clinicians/prevention/prep.htmlhttps://www.cdc.gov/hiv/clinicians/prevention/prep.html

Civil Code -Civ Division 1. Persons [38–86] Part 2.6 confidentiality of medical information [56–56.37]. (2014, January 1). California legislative information. Retrieved from https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/codes_displaySection.xhtml?lawCode=CIV§ionNum=56.107https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/codes_displaySection.xhtml?lawCode=CIV§ionNum=56.107

Culp, L., & Caucci, L. (2013, January). State adolescent consent laws and implications for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 44(1), 119–124. Elsevier Inc. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2012.09.044.10.1016/j.amepre.2012.09.044 Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/phlp/docs/prephiv-wb.pdfhttps://www.cdc.gov/phlp/docs/prephiv-wb.pdf

Department of Health District of Columbia. (n.d.). PrEP is DC’s key HIV prevention practice. PrEP. Retrieved from https://doh.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/doh/service_content/attachments/DC%20Providers%20PrEP%20Handbook.pdfhttps://doh.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/doh/service_content/attachments/DC%20Providers%20PrEP%20Handbook.pdf

Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services (HHS), and the Treasury. (2021, July 19). FAQs about affordable care act implementation part 47. Department of Labor. Retrieved from https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/EBSA/about-ebsa/our-activities/resource-center/faqs/aca-part-47.pdfhttps://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/EBSA/about-ebsa/our-activities/resource-center/faqs/aca-part-47.pdf

English, A., & Ford, C. A. (2004, March). The HIPAA privacy rule and adolescents: Legal questions and clinical challenges. Guttmacher Institute. Retrieved from https://www.guttmacher.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/pubs/psrh/full/3608004.pdfhttps://www.guttmacher.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/pubs/psrh/full/3608004.pdf

Fisher, C. B., Fried, A. L., Puri, L. I., Macapagal, K., & Mustanski, B. (2018). “Free testing and PrEP without outing myself to parents”: Motivation to participate in oral and injectable PrEP clinical trials among adolescent men who have sex with men. PLoS ONE, 13(7). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.020056010.1371/journal.pone.0200560

Guth, M., Garfield, R., & Rudowitz, R. (2020, March). The effects of medicaid expansion under the ACA: Updated findings from a literature review. Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. Retrieved from https://files.kff.org/attachment/Report-The-Effects-of-Medicaid-Expansion-under-the-ACA-Updated-Findings-from-a-Literature-Review.pdfhttps://files.kff.org/attachment/Report-The-Effects-of-Medicaid-Expansion-under-the-ACA-Updated-Findings-from-a-Literature-Review.pdf

Harriet Lane Clinic. (n.d.). FAQ. PrEP Is for Youth. Retrieved from https://prepisforyouth.org/faqhttps://prepisforyouth.org/faq

HealthInsurance.Org. (2022). What is an explanation of benefits? Glossary. Retrieved from https://www.healthinsurance.org/glossary/explanation-of-benefits/https://www.healthinsurance.org/glossary/explanation-of-benefits/

HIV/AIDS Infection - Medical Team. (2016, September 27). PrEP plan of action toolkit. Florida Health. Retrieved from http://www.floridahealth.gov/diseases-and-conditions/aids/prevention/_documents/PrEP-toolkit.pdfhttp://www.floridahealth.gov/diseases-and-conditions/aids/prevention/_documents/PrEP-toolkit.pdf ]

Horvath, K. J., Todd, K., Arayasirikul, S., Cotta, N. W., & Stephenson, R. (2019). Underutilization of pre-exposure prophylaxis services among transgender and nonbinary youth: Findings from project moxie and techstep. Transgender Health, 4(1), 217–221. doi:10.1089/trgh.2019.002710.1089/trgh.2019.0027

Hosek, S., & Henry-Reid, L. (2020, January). PrEP and adolescents: The role of providers in ending the AIDS epidemic. Journal of Pediatrics, 145(1), 1–6. doi:10.1542/peds.2019-174310.1542/peds.2019-1743

Huang, Y. A., Zhu, W., Smith, D. K., Harris, N., & Hoover, K. W. (2018). HIV preexposure prophylaxis, by race and ethnicity—United States, 2014–2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67, 1147–1150. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6741a3externalicon10.15585/mmwr.mm6741a3externalicon

Huebner, D. M., & Mustanski, B. (2020). Navigating the long road forward for maximizing PrEP impact among adolescent men who have sex with men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(1), 211–216. doi:10.1007/s10508-019-1454-110.1007/s10508-019-1454-1

Kay, E. S., & Pinto, R. M. (2020). Is insurance a barrier to HIV preexposure prophylaxis? Clarifying the issue. American Journal of Public Health, 110(1), 61–64. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2019.30538910.2105/AJPH.2019.305389

Khan, L. (2015, January 9). New California health privacy law goes into effect. Covington. Retrieved from https://www.insideprivacy.com/health-privacy/new-california-health-privacy-law-goes-into-effect/https://www.insideprivacy.com/health-privacy/new-california-health-privacy-law-goes-into-effect/

Lieu, R. (2017, May 17). H.R.2481 - PATCH Act of 2017. Congress.Gov. Retrieved from https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/2481https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/2481

Macapagal, K., Kraus, A., Korpak, A. K., Jozsa, K., & Moskowitz, D. A. (2020). PrEP awareness, uptake, barriers, and correlates among adolescents assigned male at birth who have sex with males in the U.S. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(1), 113–124. doi:10.1007/s10508-019-1429-210.1007/s10508-019-1429-2

Macapagal, K., Nery-Hurwit, M., Matson, M., Crosby, S., & Greene, G. J. (2021). Perspectives on and preferences for on-demand and long-acting PrEP among sexual and gender minority adolescents assigned male at birth. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 18(1), 39–53. doi:10.1007/s13178-020-00441-110.1007/s13178-020-00441-1

MDHHS. (n.d.). PrEP provider toolkit. MDHHS. Retrieved from https://www.michigan.gov/documents/mdhhs/PrEP_Provider_Toolkit_MDHHS_547647_7.pdfhttps://www.michigan.gov/documents/mdhhs/PrEP_Provider_Toolkit_MDHHS_547647_7.pdf

Minors’ Authority to Consent to STI Services. (2017, March 1). KFF. Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/hivaids/state-indicator/minors-right-to-consent/?activeTab=map¤tTimeframe=0&selectedDistributions=do-states-allow-minors-to-consent-to-sti-services&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%https://www.kff.org/hivaids/state-indicator/minors-right-to-consent/?activeTab=map¤tTimeframe=0&selectedDistributions=do-states-allow-minors-to-consent-to-sti-services&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%

Moskowitz, D. A., Macapagal, K., Mongrella, M., Pérez-Cardona, L., Newcomb, M. E., & Mustanski, B. (2020). What if my dad finds out!?: Assessing adolescent men who have sex with men’s perceptions about parents as barriers to PrEP uptake. AIDS and Behavior, 24(9), 2703–2719. doi:10.1007/s10461-020-02827-z10.1007/s10461-020-02827-z

Mullins, T. L. K., & Lehmann, C. E. (2018). Oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention in adolescents and young adults. Current Pediatrics Reports, 6(2), 114–122. doi:10.1007/s40124-018-0163-x10.1007/s40124-018-0163-x

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2012). FDA update, news articles HIV-1 PrEP drug can be part of strategy to prevent infection in at-risk adolescents FDA update, news articles. Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov/files/science%20&%20research/published/HIV-PrEP-drug-can-be-part-of-strategy-to-prevent-infection-in-at-risk-adolescents.pdfhttps://www.fda.gov/files/science%20&%20research/published/HIV-PrEP-drug-can-be-part-of-strategy-to-prevent-infection-in-at-risk-adolescents.pdf

New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute. (2020, January). Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) toolkit for community based organizations (CBOs). AIDS Institute. Retrieved from https://www.health.ny.gov/diseases/aids/general/prep/docs/prep_toolkit.pdfhttps://www.health.ny.gov/diseases/aids/general/prep/docs/prep_toolkit.pdf

NMAC Capacity Building Division. (2017, August). National HIV and PrEP navigation landscape assessment. NMAC. Retrieved from http://www.nmac.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/National-HIV-and-PrEP-Navigation-Landscape-Assessment-Report.pdfhttp://www.nmac.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/National-HIV-and-PrEP-Navigation-Landscape-Assessment-Report.pdf

Paer, J. M., Mattappallil, A., Bentsianov, S., & Finkel, D. (2020). 984, HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) prescription rates among adolescents and young adults (AYAs) at an urban academic medical center in Newark, NJ from 2017–2019: A quality assessment of HIV prevention for high risk youth within the epicenter of the NJ HIV epidemic. Open Forum Infectious Diseases, 7(Suppl 1), S520–S521. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofaa439.117010.1093/ofid/ofaa439.1170

Para, M. (2020, August 27). PrEP implementation in your clinic. Chicago: Midwest AIDS Training + Education Center.

PleasePrEPme.org. (2020, January). Helping people access pre-exposure prophylaxis: A frontline provider manual on PrEP research, care and navigation. PrEP Navigator Manual. Retrieved from https://www.pleaseprepme.org/sites/default/files/file-attachments/PleasePrEPMe%20PrEP%20Navigation%20Manual%20EN_JUNE2020.pdfhttps://www.pleaseprepme.org/sites/default/files/file-attachments/PleasePrEPMe%20PrEP%20Navigation%20Manual%20EN_JUNE2020.pdf

POZ. (2020, September 16). PrEP Navigator. Listings. Retrieved from https://www.poz.com/job/prep-navigator-venice-family-clinichttps://www.poz.com/job/prep-navigator-venice-family-clinic

Public Policy Office. (2021, October 1). Protecting confidentiality for individuals insured as dependents. Guttmacher Institute. Retrieved from https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/protecting-confidentiality-individuals-insured-dependentshttps://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/protecting-confidentiality-individuals-insured-dependents

Rosenberg, J. (2018, March 16). Despite increasing rates of PrEP usage, disparities remain among African Americans, Latinos. News. Retrieved from www.ajmc.com/view/despite-increasing-rates-of-prep-usage-disparities-remain-among-african-americans-latinoswww.ajmc.com/view/despite-increasing-rates-of-prep-usage-disparities-remain-among-african-americans-latinos

Ryan, B. (2021, July 21). PrEP, the HIV prevention pill, must now be totally free under almost all insurance plans. NBC News. Retrieved from https://www.nbcnews.com/nbc-out/out-health-and-wellness/prep-hiv-prevention-pill-must-now-totally-free-almost-insurance-plans-rcna1470https://www.nbcnews.com/nbc-out/out-health-and-wellness/prep-hiv-prevention-pill-must-now-totally-free-almost-insurance-plans-rcna1470

Saleska, J. L., Lee, S. J., Leibowitz, A., Ocasio, M., Swendeman, D., Rotheram-Borus, M. J., . . . Razvan, P. (2021). A tale of two cities: Exploring the role of race/ethnicity and geographic setting on PrEP use among adolescent cisgender MSM. AIDS and Behavior, 25(1), 139–147. doi:10.1007/s10461-020-02951-w10.1007/s10461-020-02951-w

Saloway, S., & Benk, R. (2021, July 29). The federal government is making HIV prevention treatment free - but there’s a catch. NPR. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/2021/07/29/1022255279/feds-are-making-hiv-prevention-treatment-freehttps://www.npr.org/2021/07/29/1022255279/feds-are-making-hiv-prevention-treatment-free

Sinead, D. M., Hosek, S., Celum, C., Wilson, C. M., Kapogiannis, B., & Bekker, L. G. (2016, October 18). Preventing HIV among adolescents with oral PrEP: Observations and challenges in the United States and South Africa. Journal of the International AIDS Society. doi:10.7448/IAS.19.7.2110710.7448/IAS.19.7.21107

Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine. (2018). HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis medication for adolescents and young adults: A position paper of the society for adolescent health and medicine. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 63(4), 513–516. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.07.02110.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.07.021

Sullivan, P. S., Sanchez, T. H., Zlotorzynska, M., Chandler, C. J., Sineath, R. C., Kahle, E., & Tregear, S. (2020). National trends in HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis awareness, willingness and use among United States men who have sex with men recruited online, 2013 through 2017. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 23(3), e25461. doi:10.1002/jia2.2546110.1002/jia2.25461

Taggart, T., Liang, Y., Pina, P., & Albritton, T. (2020). Awareness of and willingness to use PrEP among Black and Latinx adolescents residing in higher prevalence areas in the United States. PLoS ONE, 15(7), e0234821. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.023482110.1371/journal.pone.0234821

U.S. Department of Labor, Employee Benefits Security Administration (EBSA). (n.d.). Health benefits coverage under federal law. Compliance Assistance Guide. Retrieved from https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/ebsa/about-ebsa/our-activities/resource-center/publications/compliance-assistance-guide.pdfhttps://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/ebsa/about-ebsa/our-activities/resource-center/publications/compliance-assistance-guide.pdf

U.S. Food & Drug Administration. (2019, October 3). FDA approves second drug to prevent HIV infection as part of ongoing efforts to end the HIV epidemic. Press Announcements. Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-second-drug-prevent-hiv-infection-part-ongoing-efforts-end-hiv-epidemichttps://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-second-drug-prevent-hiv-infection-part-ongoing-efforts-end-hiv-epidemic

Wood, S., Lee, S., Barg, F. K., Castillo, M., & Dowshen, N. (2017, May 1). Young transgender women’s attitudes toward HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis. Journal of Adolescent Health, 60(5), 549–555. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.12.00410.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.12.004

Yusuf, H., Fields, E., Arrington-Sanders, R., Griffith, D., & Agwu, A. L. (2020, May 11). HIV preexposure prophylaxis among adolescents in the US: A review. JAMA Pediatrics, 174(11), 1102–1108. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.082410.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0824