Background and Introduction

On March 11, 2020, COVID-19 was characterized as a global pandemic (World Health Organization (WHO, 2020). In an effort to mitigate the spread of the virus, colleges switched from in-person to remote learning (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2022). This switch in learning format had its consequences; there is evidence that COVID-19-related school closures had a negative effect on the academic achievement and performance of students (Hammerstein et al., 2020). For example, it was found in a study involving students from Hanyang University College of Medicine in Korea that there was a significant decrease in average test scores in 10 out of 16 classes (62.5%) that transitioned to an online format (Kim et al., 2021). Another study concluded that COVID-19-related school closures resulted in learning loss, particularly among students from disadvantaged and low socioeconomic status (SES) homes (Engzell et al., 2021). Often, these students do not have the same privileges as their high-SES peers, such as the availability and support of parents, reliable access to the internet and technology, and secure housing (George et al., 2021; Lederer et al., 2020).

Online classes also raised concerns about the mental and physical health of educators and students alike. In a study conducted at a large public United States university, participants reported increased snacking due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Son et al., 2020). Additionally, they reported that the COVID-19 pandemic led to them experiencing depressive and suicidal thoughts (Son et al., 2020). Social isolation, which is exacerbated by the previously discussed changes to learning, was commonly cited as a key contributor to poor mental and physical health (Elmer et al., 2020; Michigan Medicine Department of Psychiatry, 2020, Son et al., 2020).

Although it is well-known that the COVID-19 pandemic has adversely affected the education, mental health, and physical health of college students, the role that living situation (i.e., on-campus versus off-campus) played in modifying the pandemic remains to be explored. Many college students believed that living off-campus during the 2020–2021 academic year meant missing out on new experiences and opportunities, but it is uncertain if there were truly advantages or benefits of living on-campus. This study utilizes a Qualtrics survey that was distributed at the University of Michigan (U-M) campus in Ann Arbor, Michigan to better understand the relationship between the effects of COVID-19 and living situation. Ultimately, these findings could help identify problem areas in the QOL of college students amid the pandemic and give us a better idea of how to address them.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

The survey used in this study was administered via Qualtrics. It was advertised and distributed to U-M students through the monthly Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program (UROP) email newsletter and several group chats, such as a 30-member U-M Housing GroupMe and an over 5000-member U-M Discord community server. All messages had a brief description of the study, its purpose, and an anonymous link to the survey. The survey was open from November 2020 to January 2021. The participants were able to take it at any time within that time frame. There were 66 responses from U-M students. Of the respondents, 44 were female (66.7%) and 22 were male (33.3%). Twenty identified as Asian (30.3%), 4 identified as black and African American (6.1%), 37 identified as Caucasian (56%), 4 identified as other (6.1%), and 1 preferred not to say (1.5%). The average household income of participants was varied: 8 reported under $25,000 (12.1%), 12 reported between $25,000 and $50,000 (18.2%), 14 reported between $50,000 and $100,000 (21.2%), 18 reported between $100,000 and $200,000 (27.3%), 8 reported over $200,000 (12.1%), and 6 preferred not to say (9.1%). The living situation of participants was almost evenly split during the 2020–2021 academic year, as 35 lived on-campus (53%) and 31 lived off-campus (47%). Within the on-campus group, 24 participants were female (68.6%) and 11 were male (31.4%). A majority of participants identified as either Asian (31.4%) or Caucasian (57.1%). Within the off-campus group, 20 participants were female (64.5%) and 11 were male (35.5%). Like the on-campus group, a majority of participants identified as either Asian (29%) or Caucasian (54.8%).

Survey Content

The Qualtrics survey had a total of twelve questions. Participants were asked for general demographic information (e.g., age, household income, and race and ethnicity), as well as COVID-19- and health-related questions (e.g., “How would you describe your physical health? How would you describe your mental health? Are you worried about contracting COVID-19?”). For the health-related questions, participants were given the options of poor, fair, good, very good, or excellent. Question 11 specifically asked participants to assess the effect of COVID-19 on the following five factors using a Likert-type scale: diet, education, exercise, sleep, and social activity. The Likert-type scale ranged from 0 to 10, with 0 being low and 10 being high. Lastly, question 12, which was an optional open response, asked participants if they had anything else to add.

Data Analysis and Collection

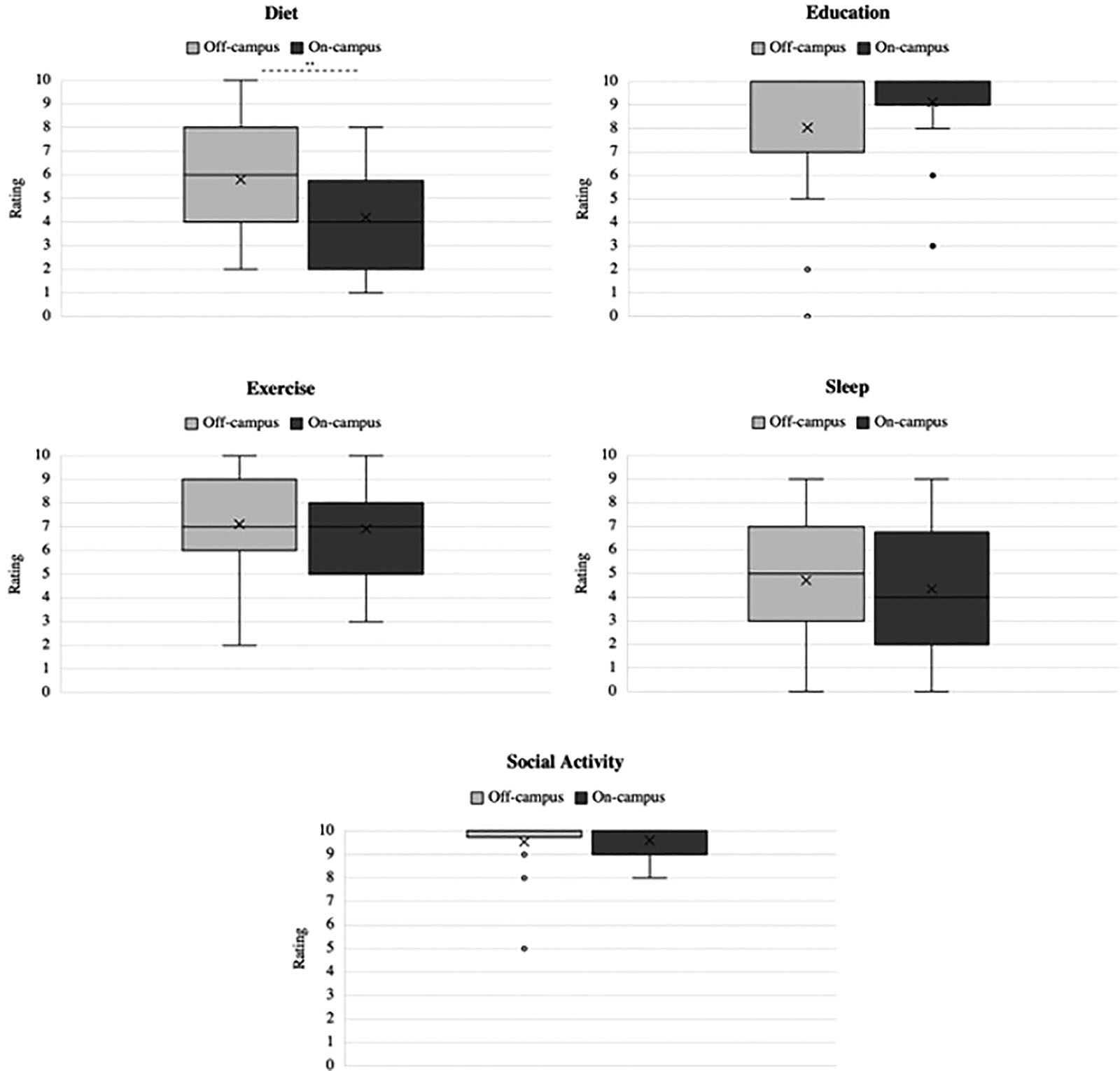

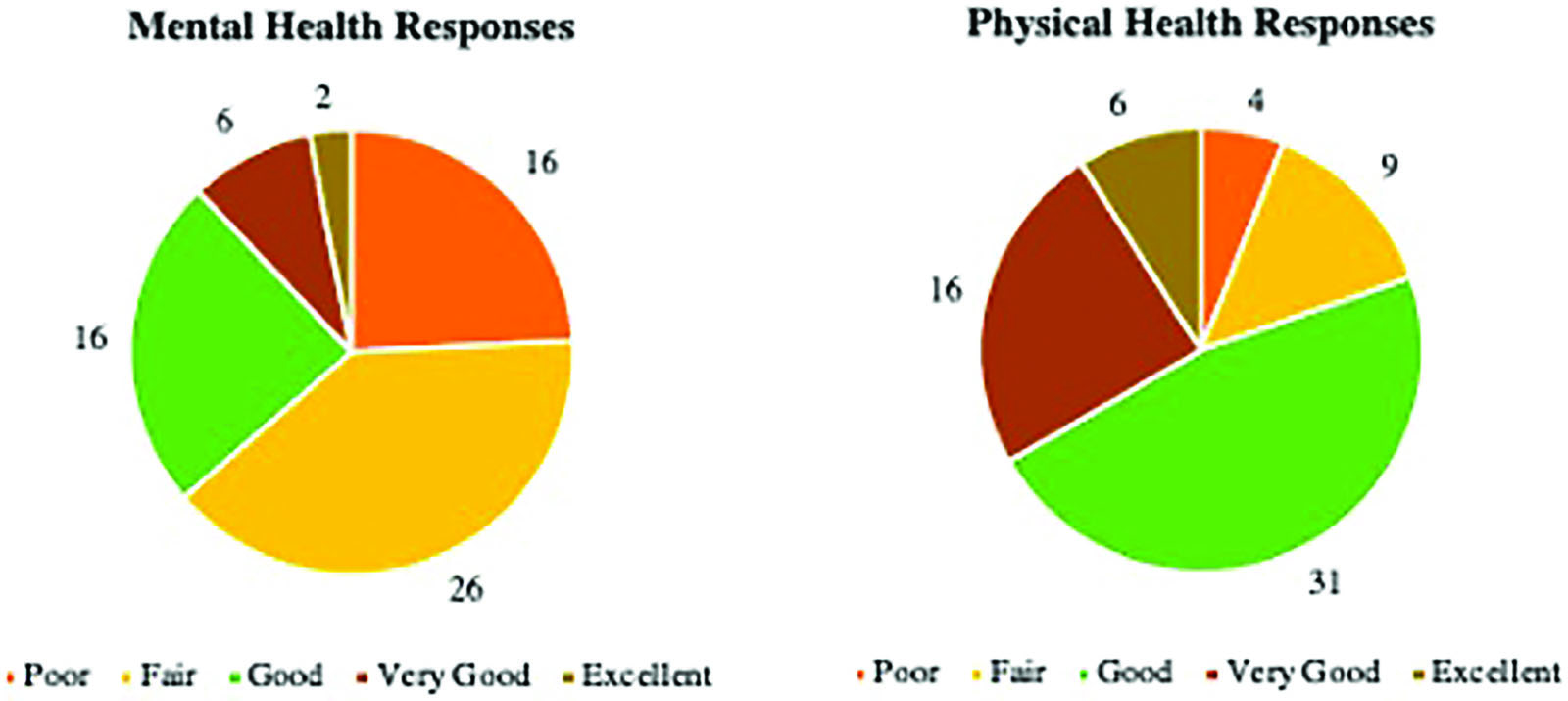

After the closure of the survey, independent t-tests were performed with JASP to determine if there were any significant differences between the responses of off-campus and on-campus participants for each of the five factors (i.e., diet, education, exercise, sleep, and social activity). A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. Box and whisker plots were generated to visualize the results (Figure 1). The responses to the mental and physical health questions were also compiled and examined for general differences and trends (Figure 2).

Discussion and Results

Diet, Education, Exercise, Sleep, and Social Activity

As shown in Figure 1 and Table 1, there was not a significant difference between the responses of on-campus and off-campus participants in terms of education, exercise, sleep, and social activity. There was, however, a significant difference in their dietary habits. This finding adds to past studies that have reported increased snacking, inconsistent eating patterns, and reduction in nutritious food consumption due to the pandemic (Son et al., 2020). There are a few reasons for why off-campus college students might not be able to maintain healthy diets, such as financial insecurity and little or no access to food pantries and grocery stores (Balch, 2020). It is also likely that the diet of U-M students living in the residential halls is influenced by the requirement of having an unlimited meal plan (Michigan Dining, 2022). Notably, the averages of participants’ responses to all five factors tend towards the mid- to high-end of the scale regardless of living situation. Education (M = 8.62, SD = 2.34) and social activity (M = 9.57, SD = .90) were the most affected, whereas sleep (M = 4.52, SD = 2.57) was the least affected. With classes being online, there are fewer opportunities to socially interact in both a classroom setting and social context, but there is also less travel time and fewer in-person commitments, which could lead to more sleep.

The statistics (i.e., mean, range, and standard deviation), as well as p-values from the independent t-tests for diet, education, exercise, sleep, and social activity of respondents. A p-value of less than 0.05 is considered significant.

Effect of COVID-19 on Diet, Education, Exercise, Sleep, and Social Activity |

||||

Factors |

Statistics |

Off-campus |

On-campus |

P-Value |

Diet |

Mean |

5.79 |

4.12 |

.01 |

Range |

2 - 10 |

1 - 8 |

||

SD |

2.38 |

2.22 |

||

Education |

Mean |

8.03 |

9.11 |

.06 |

Range |

0 - 10 |

3 - 10 |

||

SD |

2.97 |

1.51 |

||

Exercise |

Mean |

7.11 |

6.91 |

.73 |

Range |

2 - 10 |

3 - 10 |

||

SD |

2.41 |

2.08 |

||

Sleep |

Mean |

4.71 |

4.34 |

.58 |

Range |

0 - 9 |

0 - 9 |

||

SD |

2.49 |

2.66 |

||

Social Activity |

Mean |

9.53 |

9.60 |

.77 |

Range |

5 - 10 |

8 - 10 |

||

SD |

1.07 |

.74 |

||

Mental and Physical Health

Participants were asked the following questions: “How would you describe your physical health?” and “How would you describe your mental health?” Figure 2 depicts the distribution of responses to these questions. Interestingly, 53 out of 66 (80.3%) participants described their physical health as good, very good, or excellent, whereas only 24 out of 66 (36.4%) participants described their mental health as good, very good, or excellent. Most participants (39.4%) described their mental health only as fair. These results suggest that participants were able to find ways to maintain their physical health despite the pandemic. Mental health, however, was hit harder by remote classes and quarantine. The lack of social activity could be linked to participants’ mental health only being fair. In fact, surveys within the first month of the pandemic revealed that feelings of loneliness increased by twenty to thirty percent, and emotional distress tripled (Holt-Lunstad, 2020). The results presented here in the study support the recent and urgent need to address the consequences that the pandemic has on mental health (Holmes et al., 2020).

Participants’ Comments

The last question of the survey gave participants the chance to provide their own comments regarding COVID-19 and the 2020–2021 academic year (Table 2). There were 6 participants who responded, approximately half female and half male. Their ages ranged from 18 to 21, and all but two participants identified themselves as Caucasian. Several of the comments indicated frustration with their education (e.g., “professors need to make their classes easier […] we can’t be on the screen for hours and hours on end” and “the University is doing a terrible job helping students during this time…”). Other comments, such as those from participants “C” and “D,” further highlight the effect that COVID-19 has on mental health. Overall, these comments from participants bring up interesting avenues for future study (e.g., financial and pre-existing challenges), and lend a more personal perspective on issues associated with COVID-19. There is nevertheless a collective sentiment that the pandemic has been a negative and stressful experience.

Responses to the “Is there anything else you want to add?” question.

Comments Regarding COVID-19 and 2020–2021 Academic Year |

|

Participant “A” |

“Professors need to make their classes easier, their assignments lessened understanding we can’t be on the screen for hours and hours on end!” |

Participant “B” |

“COVID has mainly had a negative influence on all these areas.” |

Participant “C” |

“I feel as though my entire life has been flipped upside down by the virus. My already abysmal life became a black hole, and I am currently on the cusp of failing out of the University. I am financially burdened and feel I have no resources to aid me in my situation.” |

Participant “D” |

“I have pre-existing mental health issues whose effects are exacerbated since I am in quarantine. It’s hard getting quality distractions/relief.” |

Participant “E” |

“I am worried about contracting covid more due to the fear of spreading it to my parents than the fear of having it myself.” |

Participant “F” |

“The University is doing a terrible job helping students during this time, we need a break.” |

Conclusion

This study provides insight into how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected life for college students, and analyzes the relationship between these effects and their places of residency. The findings presented here suggest that making more resources focused on enhancing education, diet, social activity, and mental health available to students would most effectively improve their QOL. For example, free public transportation to grocery stores would greatly help students, especially those who do not have their own vehicle, with their diet. For mental health, it has been demonstrated that individual counseling and peer support groups are useful tools for reducing anxiety and depression (Viswanathan et al., 2020; Suresh et al., 2021). Of course, this study has its limitations and only tells part of the story. One limitation is that there were no explicit definitions for on-campus and off-campus. The participants simply responded with yes or no to the question of “Are you currently living on-campus?” Future research should specify what is considered on-campus (e.g., residence halls) versus off-campus (e.g., living with parents), as well as include a larger and more representative sample of college students by surveying at different campuses. Additional questions to probe for specific variables that might contribute to the differences between living on-campus versus off-campus would be helpful too (e.g., “How are you maintaining your physical health” and “Why would you describe your mental health as only fair?”). By asking these questions, the COVID-19-related issues that are faced by on-campus and off-campus college students can be further identified and addressed.

References

Balch, B. (2020). 54 million people in America face food insecurity during the pandemic. it could have dire consequences for their health. AAMC.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). Guidance for COVID-19 Prevention in K-12 Schools. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Elmer, T., Mepham, K., & Stadtfeld, C. (2020). Students under lockdown: Comparisons of students’ social networks and mental health before and during the COVID-19 crisis in Switzerland. PLOS ONE, 15(7).

Engzell, P., Frey, A., & Verhagen, M. (2021). Learning loss due to school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(17).

George, G., Dilworth-Bart, J., & Herringa, R. (2021). Potential Socioeconomic Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Neural Development, Mental Health, and K-12 Educational Achievement. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 8(2), 111–118.

Hammerstein, S., König, C., Dreisörner, T., & Frey, A. (2021). Effects of COVID-19-Related School Closures on Student Achievement--A Systematic Review. Frontiers in Psychology, 12.

Holmes, E. A., O’ Connor, R. C., Perry, V. H., Tracey, I., Wessely, S., Arseneault, L., Ballard, C., Christensen, H., Cohen Silver, R., Everall, I., Ford, T., John, A., Kabir, T., King, K., Madan, I., Michie, S., Przybylski, A. K., Shafran, R., Sweeney, A., … Bullmore, E. (2020). Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(6), 547–560.

Holt-Lunstad, J. (2020, June 22). The Double Pandemic of Social Isolation and COVID-19: Cross-Sector Policy Must Address Both. Health Affairs.

Kim, D., Lee, H., Lin, Y., & Kang, Y. (2021). Changes in academic performance in the online, integrated system-based curriculum implemented due to the COVID-19 pandemic in a medical school in Korea. Journal of Educational Evaluation for Health Professions, 18, 24.

Lederer, A., Hoban, M., Lipson, S., Zhou, S., & Eisenberg, D. (2020). More Than Inconvenienced: The Unique Needs of U.S. College Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Health Education & Behavior, 48(1), 14–19.

Michigan Medicine. (2020). Coping with the COVID-19 Pandemic as a College Student. Michigan Medicine Department of Psychiatry. Residence Hall Students: M Dining. Michigan Dining. (2022).

Son, C., Hegde, S., Smith, A., Wang, X., & Sasangohar, F. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 on College Students’ Mental Health in the United States: Interview Survey Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(9).

Suresh, R., Alam, A., & Karkossa, Z. (2021). Using Peer Support to Strengthen Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 714181.

Viswanathan, R., Myers, M. F., & Fanous, A. H. (2020). Support Groups and Individual Mental Health Care via Video Conferencing for Frontline Clinicians During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychosomatics, 61(5), 538–543.

World Health Organization. (2020, March 11). WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19–11 March 2020. World Health Organization.