Introduction

During the Asia-Pacific War (1937–45), nearly 45,000 temple bells in Japan were recycled into munitions. Most Japanese Buddhist temples have a large bronze bell (bonshō 梵鐘), weighing hundreds of kilograms, that is rung by monks to announce time and enhance certain rituals, or by pilgrims at arrival, or by visitors on New Year’s Eve. Buddhist temple bells, made in Japan beginning in the seventh century, require a significant financial investment and technical skill to achieve an attractive form with good tone. These features make each a prized object, often with a singular status and prominent placement at a temple or shrine (fig. 1). Moreover, interacting with bells can be very personal, especially by the faithful when striking to offer a prayer, since bells respond immediately with sound so strong it is believed to reach the dead. These meaningful encounters made parting with them all the more difficult. This article considers the ramifications of turning bells over for recycling to transform their identities from treasured instruments into measurable hunks of metal before becoming weapons of destruction.

The theme of recycling/reuse serves as a critical framework to evaluate not only the process of how bells were shuttled to a furnace for smelting, but also the complex negotiations that were involved in each surviving bell’s escape from that fate. In turn, such negotiations reveal that these bells have a particularly strong ability to elicit a spectrum of emotions, even from a great distance.1 Using a biographical approach based on Igor Kopytoff’s work in object biography, this article examines the life histories of four bells that survived different ordeals, as case studies to show how bells participated in recycling, repurposing, and reuniting.2 Halle O’Neal’s article in this issue also employs object biography, in which she analyzes the transformation of personal letters into sacred documents with an additive process of layering stamps of deities and sacred texts. Similarly, Samuel Morse’s article in this issue examines the redeployment of damaged pieces of wood from famous temples to create Buddhist icons with layered meanings and authority. In contrast to the subjects of these two articles, where salvaged material is rescued and re-formed into new sacred objects, the bells discussed here were deliberately pursued for destruction and recycling into something as unholy as a weapon of war. My focus is on bells from the Edo period (1615–1868) because governmental authorities regarded most Edo bells, in contrast to those made in earlier generations, as so commonplace that they became appropriate targets to recycle into war munitions. Fortunately, a few escaped.

Mobilizing and Weaponizing Buddhist Bells for War

Beginning in 1938, the Japanese government issued statements calling for the recovery of superfluous metals with collection drives called kinzoku kyōshutsu 金属供出 as a response to the escalation of the war in China. The National Mobilization Law (Kokka sōdōin hō 国家総動員法) that passed that year placed the Japanese government in control of strategic industries that handled metal to build ships and munitions. The efforts to collect scrap metal moved quickly from playground equipment, public sculpture, post office boxes, manhole covers, and iron fences before extending to household pots and pans. Funeral homes were compelled to collect and hand over the gold teeth and rings from the ashes of those cremated.3 At first the goal of metal recovery was to preserve resources, but then it became necessary for the expansion of steel production, and finally it was to increase munition production.

In 1941, as pressure became more intense, the government issued orders for mandatory metal collection (kinzokurui kaishū rei 金属類回収令). These orders continued to be reissued and strengthened until the end of the war in 1945. Compliance from what were referred to as “urban mines” and “household mines” was compulsory.4 Aside from metal, there were many other categories of collection, such as oil (for aviation lubrication), charcoal (fuel), wood (construction), mulberry bark (clothing), dried grass (feed), cotton cushions (explosives), and, sadly, dogs (fur coats).5

Buddhist temple bells, with their large size and noticeable presence, were particularly obvious targets of “nonessential” metalwork. While this activity was referred to as a “donation” for the war effort, it was actually compulsory with compensation for bulk metal by weight.6 According to a study in Yamagata Prefecture, after a bell was handed over, it would pass through the city or village collection point (usually a train station), to a regional office, and then to a prefectural metal recovery office before arrival at the metal reclamation factory. Although no measure of a bell’s true worth, payment of .89 yen per kilogram would be made to the temple or shrine about six months after parting with its bell. As an example from 1943, one temple received 335 yen in compensation for an average-size bell weighing 354 kilograms.7 This amount was equivalent to two months of an average household income for a family of four in 1941.8

There are no proper statistics, but it is estimated that of 45,000 bronze bells collected for the war effort, 60 percent (approximately 27,000) were made during the Edo period (1615–1868) and nearly 40 percent were newer. Although special exemptions were made, when counting those taken by the government and those obliterated by bombings, over 90 percent of Japan’s temple bells were destroyed. There are estimates that at war’s end about 3,000 bells made after 1615 survived, including some 2,000 that had been slated for recycling not yet carried out.9

The Ministry of Interior, the Religion Bureau of the Ministry of Education, and the Ministry of Commerce and Industry jointly issued the orders for bell requisition. While the exact guidelines were left to each prefecture, exemption was largely based on the following criteria: (1) bells related to the imperial family, (2) inscriptions referencing someone or something famous, (3) bells of superior form, and (4) old bells. Fear of desecrating an imperial sixteen-petal chrysanthemum crest led to disputes over the identification of multi-petaled lotus flower designs.10 That stories persist about certain bells being hidden from authorities by burial attest to the great stress people felt over whether a bell would qualify for exemption.11

Bells made before the end of the Keichō (1596–1615) era were considered old and thus exempt from seizure. Keichō is generally considered to be the last era before the Edo period began. In 1939, world-renowned bell expert Tsuboi Ryōhei (1897–1984) published the book Keichō matsunen izen no bonshō 慶長末年以前の梵鐘 (Buddhist bells made before the end of the Keichō era), just in time to serve as a guide for wartime bell evaluation.12 Tsuboi wrote in 1947 that over 90 percent of Japan’s bells had been lost during the Asia-Pacific War and could never be replaced. He was aware that the guidelines were not always followed and some bells as old as the thirteenth century had been seized.13 Distressed as he was over their decimation, Tsuboi made his dismissive opinion of post-1615 bells clear in a lecture he gave in English to the Asiatic Society of Japan in 1948.

The bells of this epoch [Edo] are technically good. Their sound is satisfactory and their shape is correct. But artistically they are almost dead. Their loops are ugly demon’s heads, though laboriously made, the lotus flowers on the percussion centers are lifeless floral patterns mechanically produced. In short, they are merchandise, made by the craftsmen and whose sole aim was money-making. They have the accuracy and precision that modern industry may boast of. But they are nothing more. They had entirely lost the artistic beauty which their ancestors possessed.14

Tsuboi’s low opinion of Edo-period bells is reflected in his 1939 book with the 1615 cutoff date, which was in turn followed by the government to authorize seizure. Tsuboi also explained to the audience that this was not the first time in Japanese history that bells had been confiscated to make weapons—it had also happened during the Edo period.15

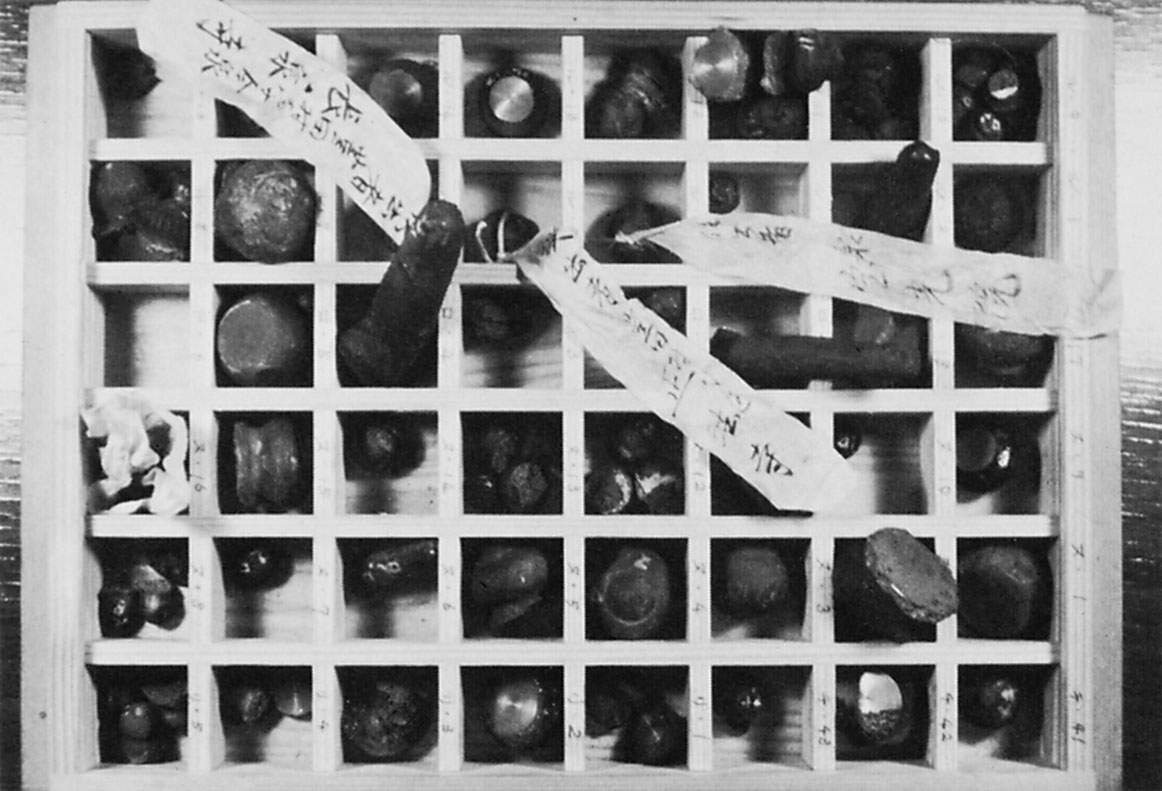

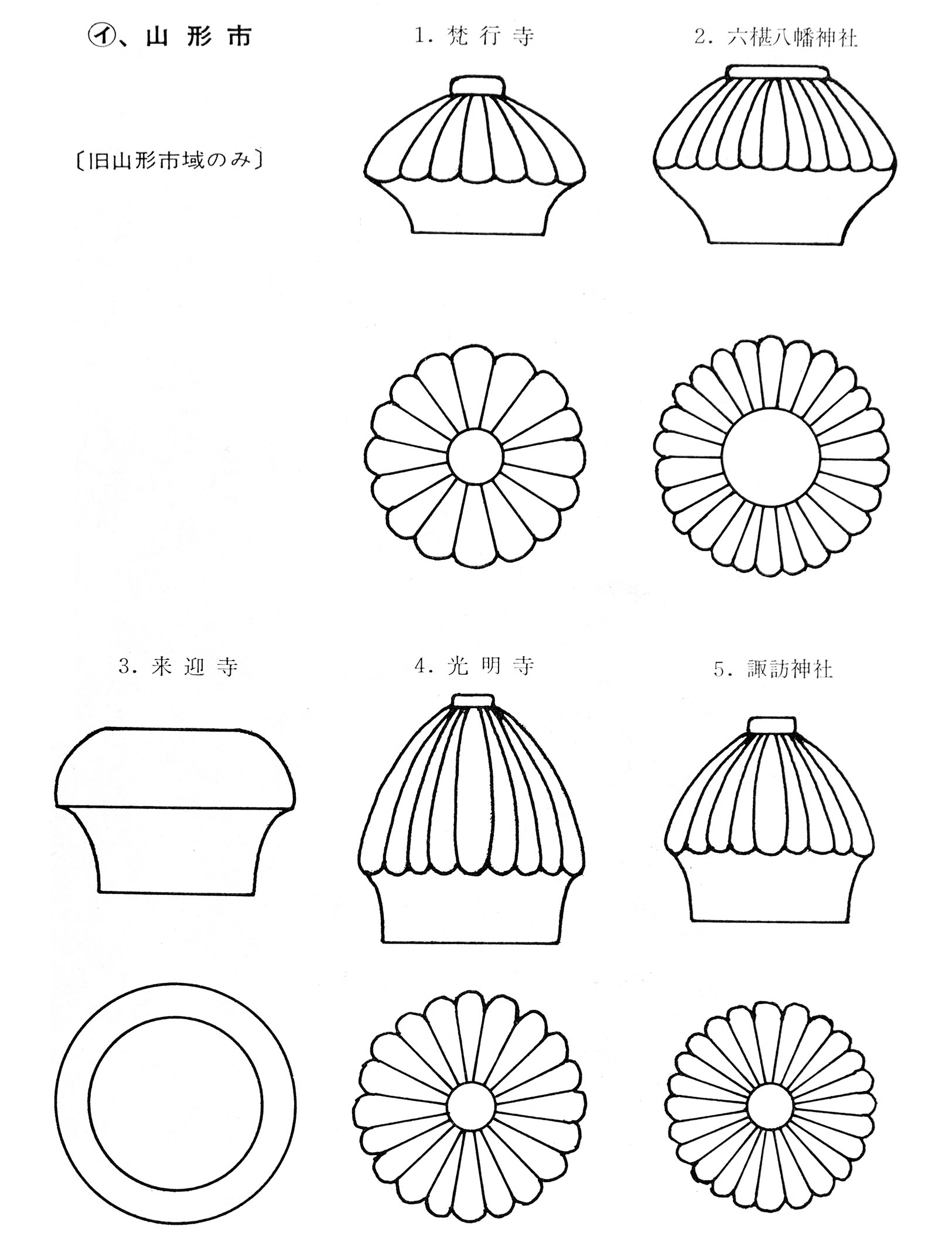

In the preface to the 1976 book Maboroshi no bonshō 幻の梵鐘 (Phantom bells), written to reclaim the history of Yamagata bells taken during the war, noted geologist Anzai Tōru 安斎徹 (1889–1976) explained that while he was working as a member of the committee responsible for wartime bell collection, he not only recorded information on each bell but also took samples of their metal and made drawings.16 The book’s author, Ogata Rikichi 小形利吉 (1912–2006), who was a curator at a local history museum and a former high school student of Anzai’s, told the story of how Anzai begged him to take over cataloging the remaining bell samples before he died. In his storehouse, Anzai had kept ten boxes, consisting mostly of bell knobs, which he referred to as “warts” (ibo 疣) (fig. 2). After the war, Anzai continued to make drawings of each one (fig. 3). He viewed each knob as an important record of the former bell’s material makeup and indication of size. Unofficially, some boxes of knobs had gone to Anzai’s high school for students to use in chemistry and physics experiments. On an emotional level, he said, extracting samples was like taking locks of hair from soldiers going off to war.17

Eventually, Ogata had the time and assistance to create a survey (sent out by postcard) asking temples and shrines about their former bell’s inscriptions, measurements, and photographs, in addition to details about when each was taken, circumstances of the farewell ceremony, and when (or if) it had been possible to get a replacement bell. Since the request included a statement that the survey was being done to celebrate Professor Anzai’s eighty-eighth birthday, it implied a sense of urgency. Nearly sixty responses, which comprised 20 percent of the surveys sent, were ultimately returned.18

Anzai’s boxes of “warts” show how in the midst of being accessed as material commodities, bells were often humanized. The author of the book’s foreword made the comparison of a bell to a mother’s body because another word used for bell knob is nipple (chi 乳).19 Anzai’s passion for capturing the lost history of the bells, as carried out by Ogata, led to a cooperative effort far different from that when the bells were surrendered to the government.

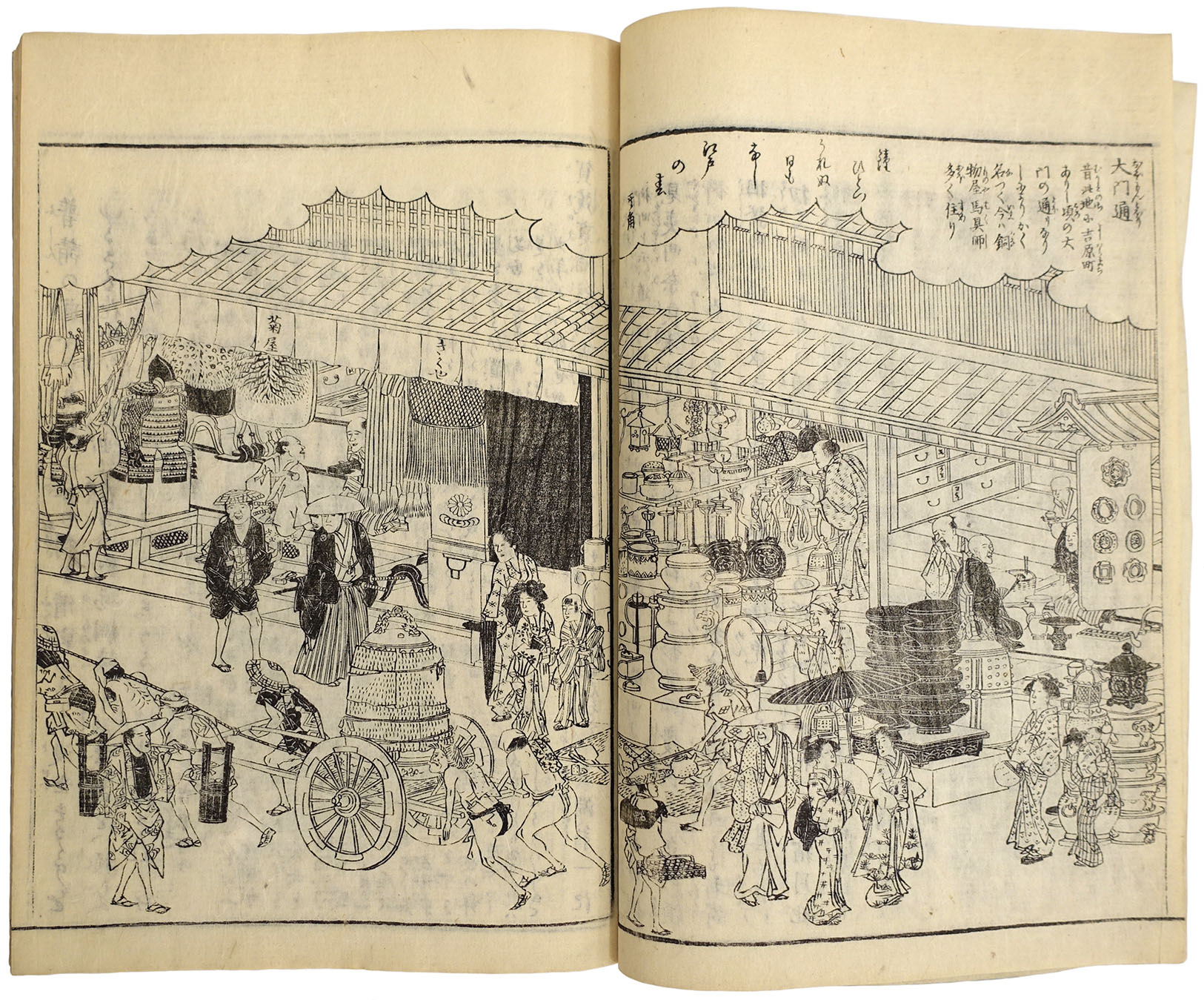

In 2001 Manabe Takashi 眞鍋孝志 (1930–2015) and Hanabusa Kenjirō 花房健次郎 (b. 1924) published the results of their twenty-year survey of 148 Edo-period bells remaining in the Tokyo area. They followed Tsuboi’s methods but did not share his low opinion of Edo-period bells.20 While many are not as refined as those from earlier times, Edo bells do exhibit a greater variety of designs. During the span of the Edo period, as bell production rapidly increased to meet the needs of the growing number of temples, bells became more commonplace. The gazetteer Edo meisho zue 江戸名所図会 (Illustrated famous places of Edo), initially published in 1834 (Tenpō 5), included an illustration of an area in Edo called Ōmondōri 大門通, where great quantities of bronze items were sold (fig. 4). Amid the newly made metal furniture hardware, braziers, and lanterns are bells (four small, one large, and another being carted away). Two roughly clad men engaged in recycling metal stand in front of the shop. One holds up a scale with which to weigh scrap, and another rakes broken items into a pile for reuse in new objects.

Embattled Bells

Temples were also under societal pressure to accede to official orders to submit their bells as patriotic duty. Beyond their material value, bells are an active part of temple life: the monks who use them, the donors, living or dead, who invest in their creation, and the parishioners who ring them for merit all have personal relationships with the bells.21 Thus, for many, parting with a bell was an enormous emotional sacrifice. We must ask how religious institutions managed to hand over their bells for the unthinkable conversion of an instrument of solace into an instrument of death.

In 1941 the journal Shashin shūhō 写真週報 (Photographic weekly report) published photographs of monks at Buddhist temples handing over metal items with a biting text that sarcastically asked:

While different approaches were taken to motivate metal donation, this 1941 article dismisses the ritual roles that bells and other metal objects played at temples as frivolous, and it attempts to build support for metal collection through pressure from the lay community.What is the point of temple bells that are never even rung once, just hanging there uselessly? And too many unused incense burners, candlesticks, and the like heaped together only become the playground of mice and the home of spiders. How much better for them to “return to society” as iron and brass. The people handing them over to make cannons and ammunition are really helping the nation.22

An eerie 1943 propaganda article from Asahi gurafu アサヒグラフ (Asahi graph) written in the “first-person” voices of bells was published to convince the public of the imperative to recycle. The bells themselves exclaim that their mission has been to save humans from suffering, but now they declare their patriotism and ultimate sacrifice to protect their emperor and country. They insist that because Japan is the leader of Asia they must fight valiantly. At the end of the article, the bells take an ultra-nationalistic tone to proclaim:

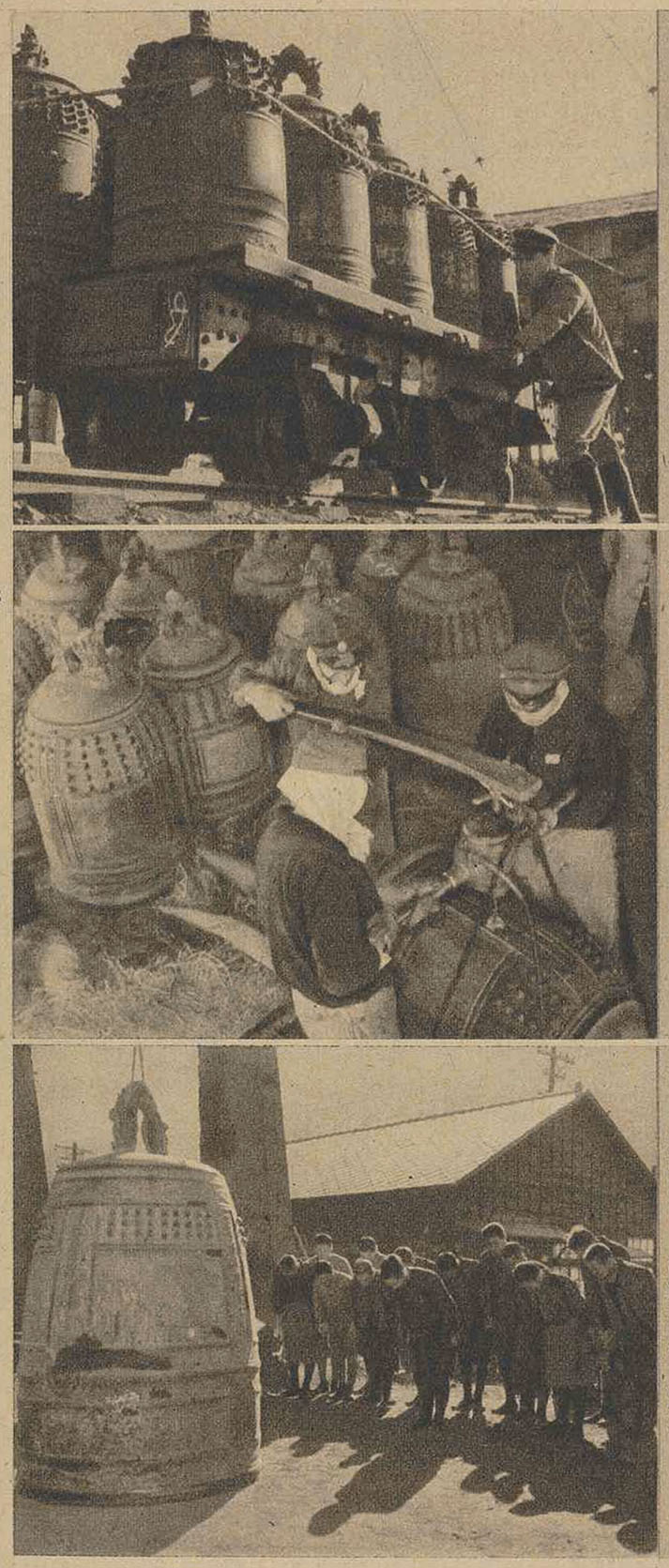

A group of three photographs in the Asahi gurafu article guides us through a bell’s journey (fig. 5). The top photograph shows a group of bells lined up for transport like soldiers on a truck. Using a bell’s voice, the caption translates to “My companions are coming and coming, they are spilling the blood of their patriotism. Look! He’s pushing the truck—Isn’t he sweating in the cold?” The photograph below shows workers drilling a hole into the side of a bell with a caption that explains, “As in a human blood test, our bodies are pierced by a hole and a sample is examined. Just as the substance of humans differs, the substance of bells also differs.” The bottom photograph shows factory workers bowing in respect to a large bell before it is sent to the furnace. On the following page, two photographs (not shown here) provide views of molten metal inside an industrial furnace with captions exclaiming how happy the bells are to give up their bodies to become weapons.I am happy because my genuine patriotism will be known to the entire country. I want to turn into a weapon as soon as possible so I can bite into the throats of the arrogant Americans and British. Countrymen! Even though my original bell shape disappears, I will now be on the front lines protecting you all.23

This article begins with a benevolent Buddhist tone and quotes the Heart Sutra (Hannya shingyō 般若心経), but halfway through, the mood dramatically shifts into an aggressive call for action. With their willingness to fight, the bells in the story not only try to convince people of the necessity to give up metal, but by comparing their inner core and surface to human blood and skin, they may also inspire people to donate their own bodies. Japanese legend is full of tales about the supernatural voices of bells. These voices are usually calming, wistful, or salvific—but sometimes indignant when humans try to force them into doing something against their will.24 In this case, however, instead of the reassuring voice of the Buddha, we find a shocking turn of events in which the bells speak gleefully of committing violence in the name of their country. As evidence of human support of their sacrifice, a 1942 photograph shows a crowd with arms raised, cheering “Banzai!” in front of Ayukai Hachiman 鮎貝八幡宮 Shrine in Shirataka, Yamagata Prefecture, as its bell is carted away to be recycled in service of the war (fig. 6).25

Memorial Services for Bells

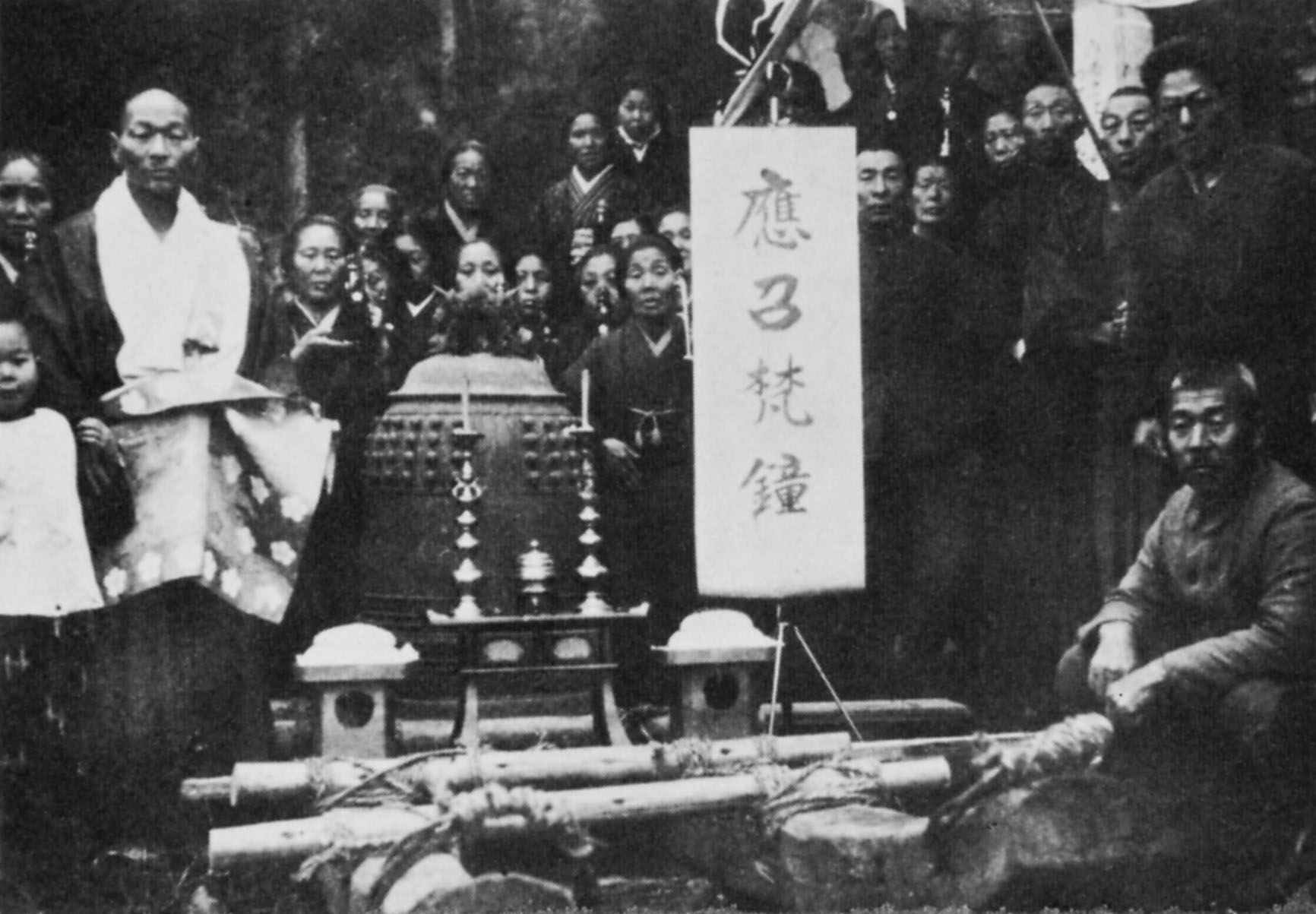

When these bells were removed from religious duty, they were often given a memorial service much like a person’s funeral. Since the seventeenth century in Japan, Buddhist memorials were common for certain inanimate objects that served humans in an intimate and dedicated manner, such as the needles and knives that seamsters’ and chefs’ livelihoods were dependent upon.26 Fabio Gygi’s article in this issue explores the memorial services performed for dolls in contemporary Japan. In a similar manner, services were also carried out for bells, especially during the Asia-Pacific War. Commemorative photographs were often taken of the events and later hung in the halls in remembrance of the departed bells.27 One example shows a dour-faced crowd posing with the bell from Enmeiji 延命寺 in Sakata City, Yamaguchi Prefecture, sitting on a makeshift altar with a sign that reads “conscripted bell” (ōshō bonshō 応召梵鐘) (fig. 7).28

In 1943 novelist Ibuse Masuji 井伏鱒二 (1898–1993) wrote the short story Kane kuyō no hi 鐘供養の日 (Day of a bell memorial service), which gives a detailed description of a rite as well as the mood of such an occasion.29 In fiction Ibuse could convey the personal sorrow surrounding a bell’s departure more poignantly than in a factual account. The setting is an imaginary temple called Ryūzenji 龍禅寺 in Hiroshima, where Ibuse grew up. The story centers on conversations between the temple’s abbot and its main patron about a fitting farewell as they relinquish their bell for the war effort.

In spite of careful planning, during the ceremony just before the abbot was about to ring the bell, he realized that because it had already been hoisted up for transport, the bell was in a bad position to ring. When he hit the bell, instead of a clear tone there was a dull thud. Even knowing each strike would be poor, everyone in the crowd just followed the abbot and one by one continued to strike the bell, becoming more distraught with every thud. After the bell was taken down, the abbot and the patron accompanied it to the train station, where it was unloaded at a collection point for bronze bells. As they watched the snow start to fall on the bells, they mused about whether bells feel the cold. Then they noticed that their own bell bore an inscription stating it was made in the “fire-sheep” year of the Meiwa era (1764–1772). They began a debate over the bell’s age and appearance, as well as the morals and ideals of earlier generations. When the patron instructed the abbot in the proper order of era names to determine the date, the abbot countered that the bell’s design of simple elegance seemed to belong to an earlier, classic period.30

While the details of this memorial are fictional, Ibuse conveys the solemnity of the occasion by recounting the order of the Buddhist texts used: Heart Sutra, a commonly recited prayer; Ten Names of Buddha (Jūbutsumyō 十佛名), often read at funerals; and Marvelously Beneficial Disaster Preventing Dhāraṇī (Shōsai myō kichijō darani 消災妙吉祥陀羅尼), which is chanted in Zen temples. Ibuse wrote that in addition to a place for the patron’s individual remarks in the ceremony, there was to be a formal reading of a text titled “Commentary on Memorial Service for Donated Buddhist Bells” (Kyōshutsu bonshō kyōshutsu nensho 供出梵鐘供養念疏). Although this title sounds official, Ibuse invented the name of a text to accompany a ritual that had become common practice at the time but was not standardized.31 Benedetta Lomi’s essay in this volume shares related traditions of protocol for “sending away” Buddhist icons.

Ibuse punctuated the sadness of the memorial with repeated descriptions of the bell’s awkward sound. Keiko Takioto has suggested that Ibuse wrote the story as a metaphor for how, even though people came to realize Japan was unprepared for war, it was too late to turn back.32 Although this piece was first published in a military journal while Ibuse was working for the government writing war propaganda, it was later considered the author’s most antiwar story.33 The fact that Kane kuyō no hi is set in Hiroshima, and was written two years before the United States dropped the atomic bomb there in 1945, makes it seem prophetic. When the abbot tells the patron he thinks the bell has an older design, this might be interpreted as his wish to claim the bell was made before the Edo period and thus is exempt from confiscation. Even so, at the end of the narrative the two recognize the futility of their conversation.

Bell Memorials in Concrete and Stone

Beyond a commemorative photograph of a memorial service, a more material way to memorialize a bell taken during the Asia-Pacific War was to have a substitute made of concrete or stone. Renshōji 蓮昌寺 in Tokyo has a wonderful example of a concrete replacement bell (fig. 8). Renshōji is a Nichiren 日蓮, or Hokke 法華, School temple said to have been founded in the fourteenth century. Measuring 174.3 centimeters in height, the concrete bell has a large dragon loop, 108 bosses, and inscriptions, all just like a real bell. Most of the text is worn, but the prominent text “Namu Shakamuni butsu” 南無釈迦牟尼佛 (Homage to Śākyamuni Buddha), is in the distinctive elongated calligraphic style associated with Nichiren’s hand. Other decipherable parts of the text tell us that the temple’s original bell was donated to the war effort in 1944 and names the two main donors of the replacement who had it made in 1951 to transfer merit to the whole universe and all spirits. While the souls of many war dead were certainly fresh in the minds of those who commissioned and constructed the concrete bell, the inscription also memorializes the bell that was removed from the temple.

According to the gazetteer Shinpen musashi fudokikō 新編武蔵風土記稿 (Newly edited records of Musashi local history), compiled in 1835 (Bunsei 8), the bell that formerly hung in Renshōji’s belfry was cast in 1765 (Meiwa 2).34 Today a bronze bell from 1966, serving as the temple’s main bell, has an inscription explaining in detail that this bell replaces the 1765 bell that was given up for the Asia-Pacific War effort in 1944, but it does not mention the concrete monument (fig. 9).

Because bell towers were constructed in a way that might collapse without the counterweight of a suspended bell, some temples hung substitutes made of concrete, stone, or ceramic.35 A light gray stone carved into a bell shape is suspended inside the belfry at Enmyōji 圓明寺 (fig. 10), a temple in Nagoya that gave up its bell in 1941 and decided to keep its replacement.36 Measuring approximately 80 centimeters in height, it is carved in the design of a bell but has no inscription. Attached to the bell tower is a hanging wooden beam that only makes a soft, dull sound when it strikes the stone bell.

Surviving bell memorials made in different forms and materials are scattered across Japan. As the surrogate bells crumble, more and more of them are being preserved in a new status as Asia-Pacific War memorials by a new generation who did not witness war firsthand. The muteness of the stone and concrete bells speaks eloquently of the great void left by the war dead.

Bells as War Trophies and Remnants of War: Case Studies

At the end of the Asia-Pacific War, some servicemen took bells home as war trophies. US military officials authorized transport on six or more warships, including the USS Atlanta, Boston, Duluth, Iowa, Pasadena, and Topeka that were in Tokyo Bay at the end of the war. Other unauthorized Japanese bell “souvenirs” were removed from the country, and while at least fifteen have been returned, others are likely to be discovered. The four case studies below were selected to show the variety of paths that surviving conscripted bells took to return.

A Former War Trophy’s Conversion to Peace Bell at Myōkeiji

Fifty-one years after conscription in 1940, a bell that was returned in 1991 to its temple from Topeka, Kansas, exemplifies the enormous effort required in the process of removal and return. After the war ended, this bell began its international journey when it was picked up in a Yokosuka scrapyard and loaded onto the USS Topeka. After the ship returned to the United States, the bell was donated to its namesake city. In 1952 the bell was placed on a concrete slab in Topeka’s Gage Park and eventually painted green. In 1974 it was removed from the park and restored, and then the mayor ordered a special “oriental-style frame” built to display it on a street downtown, between Topeka City Hall and Shawnee County Courthouse. The sign posted in front read, “This bell is a Japanese souvenir from World War II presented to the city of Topeka, Kansas by USS Topeka CL 67 Reunion Group Inc, August 10, 1974. James W. Wilson, Executive Director.”37

Members of the Zen Center in nearby Lawrence saw it and were upset by the inappropriate public spectacle of a sacred Buddhist bell outside government buildings. The 2008 documentary Resonance: The Odyssey of the Bells provides footage of an interview with former Zen Center member Mimi Thebo, who organized a letter-writing campaign to have the bell returned to Japan. In her own letter to Mayor Douglas S. Wright, dated April 20, 1988, Thebo wrote the following: “This bell used to ring for morning and evening practice to the monks and laypeople it called. It was as dear as your church organ is to you. It is shameful for us to exhibit this stolen bell as a ‘trophy’ of war. I call upon you as a fellow Kansan and a person of honor to restore this bell to Buddhists of Japan as a gesture of friendship and pledge of peace.”38

When the mayor contacted James Wilson of the USS Topeka Reunion Group about the bell’s return, an argument ensued among the members, who technically still owned it. Although some were angry because they felt they had won it as a war trophy “fair and square” and did not want to give it back, Wilson and the mayor eventually agreed that returning it to the temple was best.39

The bell hailed from Myōkeiji 妙慶寺 in Shimizu City, Shizuoka Prefecture, and temple parishioners agreed to pay to have it returned. On August 25, 1989, a ceremony at the Topeka City Center Holiday Inn was performed to transfer the bell officially to thirty-seventh generation the Reverend Imizu Gyōbun 井水堯文 and five representatives from Myōkeiji with USS Topeka Reunion Group members in attendance. Through an interpreter, the Reverend Imizu said, “When it was made almost 200 years ago, it was made through donations by the parishioners. And not just donations of money, but heirlooms like mirror frames and other items of gold. Its importance was not just that it was made to be there and to be used but that it embodies the spirits, the souls of those parishioners.”40 Finally, in 1991 then-Topeka Mayor Butch Felker and his wife traveled to Myōkeiji for the dedication of the reinstalled bell in its newly built belfry.41

Next to the bell, now positioned beside the temple’s graveyard, is detailed bilingual signage about its international journey (fig. 1). The well-proportioned bell has 108 bosses, or knobs, two multi-petaled lotus-shaped strike plates, and an inscription stating it was made in 1795 (Kansei 7) by the caster Numagami Chūzaemon 沼上忠左衛門 from Kawaragaya 河原谷 in nearby Mishima (fig. 11).42 The bell has two large vertical lines of bold, convex characters below two knobs and arched bands. One side prominently displays the full temple name Enkyōzan Myōkeiji 圓教山妙慶寺, and the other side has the phrase Namu myōhō rengekyō 南無妙法蓮華経—translatable as “Homage to the Lotus Sutra.” Nichiren 日蓮 (1222–1282), the charismatic founder of the Hokke School of Buddhism, preached the superiority of chanting this phrase as a means to end suffering, eradicate bad karma, and attain enlightenment. Known as the Daimoku 題目 (lit., “title”) because it refers to the Lotus Sutra’s sacred title in Japanese, the presence of this phrase in large characters, in the same distinctive style as in the previously discussed concrete bell monument from Renshōji, makes the temple’s sectarian affiliation obvious. Indeed, Myōkeiji was founded as a Hokke School temple in the sixteenth century. To the left of the Daimoku on the Myōkeiji bell, and also in convex script, is the name and cipher of twentieth-generation Abbot Nichiken 日研, who was responsible for the bell’s casting campaign. Large swaths of incised text list the names of numerous donors.

The Reverend Izumi’s comment that the bell embodies its parishioners through donations of infused personal objects demonstrates that strong emotional ties were at play. When visiting Myōkeiji, I discussed the return of the bell with the current priest’s wife and was struck by her positive attitude about the events. She said that if the bell had not been taken by the US Navy, Myōkeiji would not have it now.43 The Myōkeiji bell’s life story shows a radical journey from beloved temple bell to potential weapon, war trophy, public dispute, international relations object, and symbol of peace.

Shōjuin Bell: Ex-Military Mascot in Iowa

Shōjuin 正受院 is a small Jōdo School temple in Tokyo, east of the bustling Shinjuku Station, just off Yasukuni Street. Its bell, which measures 143 centimeters in height, has an inscription with the date of 1711 (Hōei 8), the names of two casters, Kawai Hyōbu 河合兵部 and Fujiwara Chikanori 藤原周徳, the name of the temple, a large block of text about the bell’s merit, and the names of fifty-four donors (fig. 12).44 In the mid-nineteenth century, Shōjuin became a wildly popular site for the worship of Datsueba 奪衣婆, a tutelary deity who has the appearance of an old hag, and by the 1950s the temple became well known for its memorial service for used sewing needles. Shōjuin gave up its bell in 1942 for mandatory metal collection, but the bell later resurfaced in Iowa. After forty years in exile, the bell was returned home in 1962.

According to a 1988 newspaper article, Shōjuin chief priest Haraguchi Tokushō 原口徳正 (1912–?) said that the bell, over 200 years old, conveys the voice of the Buddha.45 In 1942 the bell tower was draped in patriotic red-and-white curtains. He knew he had to give up the bell for the war effort, but as he thought about it being used to make cannons and guns, he could not stop crying because he considered the bell to be as irreplaceable as a dear companion. A year later Haraguchi was called to military service and sent to Japanese-occupied Manchuria in north China. After the war ended in parts of China, he continued to endure harsh conditions as a prisoner of war of the Soviets in Siberia. When he finally returned home four years later, in 1947, he found the bell tower and main hall gone. His wife, Haraguchi Tsurue 原口鶴枝 (1917–?), who took care of the temple throughout the war, said much of the area had been destroyed by aerial bombing. She recalled that in those days she lived at the temple like a beggar in a makeshift barrack-style building and had barely enough to feed her child.

Meanwhile, the Shōjuin bell was never melted down for munitions, but instead taken aboard the battleship USS Iowa at the end of the war and brought to the United States as a souvenir/war trophy. A US Navy Special Training Unit donated the bell to the Naval Reserve Officers Training Corps (NROTC) at Iowa State University (formerly Iowa State College) in Ames. A 1948 newspaper article read:

A few days earlier the student newspaper had published a similar article, titled “NROTC Receives Jap Temple Bell as War Memento,” and two days later a photograph of a man and woman admiring the bell appeared in the paper.47 According to James Leftwich Lee Jr., “In later years a touring Japanese group saw the bell and correspondence developed over its history and significance. It seems the bell was over two hundred years old and had some religious significance to the Japanese.”48Latest trophy to be brought to Iowa State college is 200-year-old Japanese temple bell, given to the NROTC unit by Secretary of the Navy John Sullivan. . . . The American military government unit in Kanagawa Prefecture, Yokohama, took the bell from the scrap heaps and gave it to the crew of the battleship USS Iowa as a memento of its post-war visit to Japan. They, in turn, brought the bell to the United States where it was decided to send it to Iowa State college where numerous Navy men received training during the war and where the present NROTC unit is located.46

Once it was decided to return the bell in 1962, there was initial secrecy surrounding the bell’s departure. “Officials said they felt the bell’s return would be ‘bad publicity’ in light of the Japanese sending ‘friendship’ bells to Iowa. . . . No one seems to know or will admit how the bell found its way to campus or whose responsibility it is.”49 A few days afterward, US Navy authorities decided it was better to be transparent about the affair. A subsequent newspaper article explained that the bell had been “rescued” from a scrap heap near Yokohama before being “presented” to the battleship USS Iowa and was now being returned as a gesture of friendship. The article further reported, “The action is the second interchange between Iowa and Japan involving temple bells. Yamanashi Prefecture was given 35 hogs and 60,000 bushels of corn by Iowans after typhoons hit the area in 1959. The prefecture, now Iowa’s ‘sister state[,]’ showed its gratitude by sending a 1,000 pound temple bell and bell house which will be installed in a flower garden on the capitol grounds in Des Moines.”50

In 1962, a few months after Iowa State University returned the bell to Japan, the new bell was dedicated in a pavilion outside the Iowa state capitol building (fig. 13). On its midsections, the bell has large blocks of bilingual text explaining the gift and a depiction of Mount Fuji, and on the lower sections are pairs of flying celestial beings. At the formal dedication of this Japanese friendship bell, instead of celestial beings the governor’s speech highlighted flying hogs.

Today, in the shadows of Mt. Fuji, the sacred mountain of Japan which province [sic], these animals and their offspring represent the hopes and livelihood of the citizens of our sister state. Officials have kept in touch with this program in Yamanashi and report that more than 500 hogs have been produced as progeny of the breeding hogs air-lifted from Iowa 2½ years ago. Because Iowans were responsible for that shipment, and because Iowa is Yamanashi’s sister state, this bell of friendship is a gift from the people of Yamanashi to the people of Iowa.51

The text on the plaque posted in front of the capitol’s bell at present mentions the famous “hog-lift.”

In 1962 as the area of Shinjuku was rapidly developing, the Haraguchi family welcomed the bell back to Shōjuin. In 1964 the year of the Tokyo Olympics, its new belfry was completed, the bell was installed, and the voice of Buddha could be heard there again (fig. 14).52 Friendship bells are a widespread phenomenon of symbols used to build international relationships.53 Because of the war, the mission of the Shōjuin bell swung drastically from one that would destroy international relationships to one that would help rebuild them.

Genkakuji Bell: Journey to an Island Paradise Turns to Hell

During the Edo period, the Jōdo School temple Genkakuji 源覚寺 in Tokyo was well-known as a place to pray to Enma 閻魔, King of the Underworld, to avoid hell and be spared from other types of suffering. The special day to visit Enma at Genkakuji, also known as Konnyaku Enma こんにゃく閻魔, was on the sixteenth of every month.54 Bearing witness to multiple experiences of different kinds of hell on earth, Genkakuji’s bell now prominently displays its battle scars (fig. 15). In addition to the date of 1690 (Genroku 3), the bell’s inscription gives the temple name and location, the caster name of Kokawa Tango no kami Kogawa Chōzaburō 粉河丹後守粉川長三郎, donor names, and text that includes a vow to distribute all merit equally and praise Amida Buddha.55 The bell, measuring 149 centimeters in height, not only survived a devastating fire in 1844 (Tenpō 15) that destroyed its belfry, but also the Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923.

By 1937 Genkakuji, which had still not replaced its bell tower lost in the 1844 fire, decided to donate its bell to a temple called Nanyōji 南洋寺, literally “temple of the south sea,” on Saipan, the largest of the Northern Marianna Islands in the Pacific Ocean, some 2,600 kilometers south of Japan. Saipan’s indigenous Chamorro people were colonized by Spain from the sixteenth century until 1898, then by Germany until 1914, and then by Japan until 1945. Now Saipan is a commonwealth of the United States.

In 1932 the Reverend Aoiyagi Kankō 青柳貴孝, whose temple had a relationship with Genkakuji, established Nanyōji and also built a girl’s school in Saipan.56 A Japanese newspaper article announcing the dedication of the Nanyōji belfry on December 9, 1937, reported, “When the dedication of the bell tower takes place, it will be the first time the sound of a Buddhist bell echoes across the ocean over there. On that day, first the bell’s dedication will take place and second will be a memorial service for the dead and wounded in the fighting following [what is known in Japan as] the China incident (Shina jihen sen 支那事変戦).”57 The author refers to the bell’s role in comforting those who were suffering and dying in the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945), which had just begun in China a few months prior to the installation of Genkakuji’s former bell at Nanyōji.

In the three-week 1944 Battle of Saipan, over 55,000 lives on both sides were lost before the few remaining Japanese soldiers surrendered to Allied Forces. Nanyōji was located in Saipan’s capital city Garapan, which was bombarded by US Navy warships on June 19. As American soldiers were destroying Nanyōji, shrapnel and bullets hit the bell, the scars of which can still be seen. In the following days, US Marines went through the rubble checking for hidden soldiers and civilians; and once the city was declared secure, some of them collected souvenirs.58 At some point after the battle, the bell disappeared and it is rumored that an American Seabee (Navy Construction Battalion) took it as a souvenir. Nearly all Japanese residents of Saipan were repatriated after the war but not the bell. A prisoner of war who had left Saipan and returned to Japan reported that the bell had survived the battle intact.59

A 1948 article in Pacific Stars and Stripes explained that because the bell was the only thing left of Nanyōji, repatriates had petitioned to have it found and sent back to Tokyo so they could build a memorial. The petition was rejected: “Dr. W. K. Bunce, chief of the Religions and Cultural Resources division of SCAP’s [Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers] CIE [Civil Information and Education] section, explained that in fairness to American tax-payers, who would otherwise be paying the costs, the return of the temple bell must be preceded by the resumption of a stable Japanese economy.”60 On the same day, a Japanese newspaper article that registered disappointment over the decision commented that over eight hundred people, including Saipan survivors, had signed the petition for the bell’s return.61

The bell’s location remained unknown until 1965, when a woman named Mitsue Hester spotted it in a junkyard in Odessa, Texas, and read its identifying inscription. She wrote a letter to the Japanese Ministry of Education, which informed the temple of the bell’s discovery, but the junkyard suddenly sold the bell and no action was taken. In 1973 Genkakuji acting chief priest Miyoshi Yūshō 三好祐照 contacted the Odessa city office and learned that the bell was now owned by maritime supplier Donald V. Clair (1922–2012) of Oakland, California, and housed in a museum. Letters to the museum from Japan pleaded for the bell’s return: “The bell should only be used as a ritual object and has nothing to do with war. Wasn’t it moved to your country from Saipan?” But no reply came.62

Clair had a substantial collection of model ships, bells, and other large objects with which he intended to develop a display in a maritime museum on the Oakland waterfront, but the plan proved unfeasible so he sold his whole collection, including the bell, to a San Francisco auction house in 1974. The bell did not sell despite its description among the auction items in a newspaper article: “Clair collected non-maritime doodads, too. A two ton, 17th Century Buddhist temple bell from Japan.”63 Then Kiyoshi Hirano (1920–1987), a Buddhist church member and owner of hotels in Stockton, California, stepped up on behalf of a friend who was a Genkakuji parishioner. Hirano became heavily involved in negotiations and worked with the Buddhist Church of America to raise funds for the bell’s return. These efforts convinced Clair to buy the bell back and donate it to Genkakuji. Before the bell left the United States, it appeared as a public-relations feature at the San Francisco Cherry Blossom Festival in 1974 with a blessing by the Reverend Miyoshi.64 The Saipan journal Highlights published a photo of the event showing Clair smiling and shaking hands with Miyoshi in front of the bell.65

At the time Genkakuji’s new bell tower was finished in 1982, Hester, who had discovered the bell in Texas almost two decades earlier, commented, “It is as if the souls of the soldiers who died in the war returned safely back home with the bell.”66 Surrounded by other war memorials, the bell now hangs at Genkakuji, honored by the name “Pan-Pacific Bell” (Han taiheiyō no kane 汎太平洋の鐘) and praised because the bullet holes and battle scars do not dampen the clarity of its tone (fig. 16).

Nensokuji Bell: Former Surrogate Takes a Long Journey Home

Less than a ten-minute walk from Genkakuji, we find that the temple Nensokuji 念速寺 in Bunkyōku, Tokyo, has another bell, measuring 133 centimeters in height, with a complicated story of disappearance and relocation (fig. 17). The bell’s inscription gives the date 1758 (Hōreki 8), temple name, location, its makers as Nishimura Izumi no kami 西村和泉守 and Fujiwara Masatoki 藤原政時, a lengthy text about the temple’s lineage of Jōdo Shin School head monks, and a verse about the reach of its sound and the virtues of transmitting the dharma.67 In contrast to the lofty ideals in the inscription, before the Asia-Pacific War the bell had acquired the inelegant but affectionate nickname “Shonben kane” しょんべん鐘, or “Pee Bell.” Older people who lived nearby used to say that if you hear the sound of the bell in the morning, it means it is time to get up and go to the toilet.

Like so many others, this bell was conscripted in 1944 during a metal drive. Although it was brought to a factory in Kumaya, Saitama Prefecture, to be smelted for munitions, the war ended before that occurred. Later, the head monk from Ōshōji 應正寺, a Shingon School temple in Saitama, went to the factory to look for a new bell since his had been taken by the government. When he noticed the Nensokuji bell was the right size, he bartered for it with some rice.68

In 1983 Hanabusa Kenjirō, previously mentioned in regard to his survey of Edo-period bells, learned by chance about the bell at Ōshōji when he went to examine a different bell in Saitama at nearby Kyōnenji 教念寺.69 Although at that time he pointed out the discrepancy in the temple names and sectarian lineage, the Nensokuji bell remained at Ōshōji until 1996. When the new chief priest of Ōshōji wanted to construct a new bell tower, he inspected the bell, read the inscription, and realized that not only had it come from a different temple but also from a different school of Buddhism. Then he quickly contacted Nensokuji and began negotiations to return it, which took place later that year. Nensokuji, which had been destroyed by aerial bombing during the war, had long since been rebuilt. Now instead of keeping the bell outside, the temple has mounted it on a movable frame inside Nensokuji’s main hall and it is treasured as a war survivor. Ōshōji was able to obtain a brand-new bell for its new belfry.

Stories of bells that made it back to their temples after the Asia-Pacific War were rarely recorded and their reunions rarely published, which makes it difficult to identify those that were successfully returned. Nensokuji is an important example because, beyond the initial seizure and final return, it reveals other awkward aspects of a bell’s past, from its nickname to the fact that even though its inscription clearly identified its original owner, its return was not pursued until 1996. Unlike the stories of international repatriation, this bell only had to travel a few hours to come home. But the journey took over fifty years.

Conclusion

Following the lives of the four temple bells from Myōkeiji, Shōjuin, Genkakuji, and Nensokuji provides a sample of bells known to have survived the destruction of 45,000 of their kin. Through the perspective of the different paths taken by the four bells, we can consider their roles in the devastation and recovery from the Asia-Pacific War. The bells’ life stories not only demonstrate the process of how bells traveled great distances but also the intense emotional investment they carried. Those feelings were anything but stable. While some constituents were clearly willing to shout “Banzai!” in support of the war, others needed persistent persuasion through written and visual propaganda in addition to peer pressure.

Originally, these bells solidified their institutional lineage, memorialized past patrons, and instantiated the hopes of parishioners. As they were threatened with recycling into weapons of destruction, during such a time of desperate circumstances the government’s limited compensation made it a little easier to part with them. Although these four bells averted being melted down, in order to survive before returning home they had to assume new identities: as trophies, pieces of junk, curiosities, or a proxy representing a different sectarian lineage. Along the way, after the bells’ worth was assessed by weight and their positions shifted, the range of human emotions they carried spanned the spectrum of indifference to embarrassment, patriotic passion, respect, grief, pain, solace, and joy.

Acknowledgments

My research has benefited from the assistance and encouragement of many individuals. In particular, I would like to thank Halle O’Neal, Michael Jamentz, the two anonymous readers, Yui Suzuki, Masayoshi Aoki, Mark Olson, the Reverend Yoriko Kondō, and Michiko Ito.

Author Biography

Sherry Fowler, PhD (UCLA), 1994, specializes in Japanese Buddhist art. Her interests include premodern Buddhist sculpture, Edo- and Meiji-period Japanese temple prints (keidaizu), pilgrimage prints (ofuda), foreign interactions with Japanese art, issues of collecting, and ritual. She is author of the books Accounts and Images of Six Kannon in Japan (2016) and Murōji: Rearranging Art and History at a Japanese Buddhist Temple (2005). Her current research project is on the relationship between dragons, water, and Buddhist temple bells in Japan. E-mail: sfowler@ku.edu

Notes

- For an overview of the study of emotions and objects, see Stephanie Downes, Sally Holloway, and Sarah Randles, eds., Feeling Things: Objects and Emotions through History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018). ⮭

- Igor Kopytoff, “The Cultural Biography of Things: Commoditization as Process,” in The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective, ed. Arjun Appadurai (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), 64–92. ⮭

- Ishikawa Kōtoku 石川浩徳, “Bonshō to heiwa 梵鐘と平和 (Bells and peace)”, Gendai shukyō kenkyū 33 (March 1999): 2–3. ⮭

- “Kieta kane no ne—Shūsen hiwa sono 11” 消えた鐘の音-終戦秘話その11- (Sounds of lost bells-The secret story of the end of the war, part 11-), Wagamachi kōhoku 116 (August 2008), https://www.okuraken.or.jp/depo/chiikijyouhou/kouhokurekishibunka/kouhoku116/. ⮭

- Murai Eiji 村井栄治, “Aichikenka no sensō iseki—konkurīto no bonshō to gunjinzō” 愛知県下の戦争遺跡―コンクリートの梵鐘と軍人像― (War ruins in Aichi Prefecture―Concrete bells and soldier statues―), Komyuniti 10 (March 2007): 115. ⮭

- “Kieta kane no ne.” ⮭

- Ogata Rikichi 小形利吉, Maboroshi no bonshō: senji kyōshutsu no kiroku 幻の梵鐘:戦時供出の記錄 (Phantom bells: Records of wartime conscription) (Yamagata: Kōyōdō Shoten, 1976), 156–57. ⮭

- Sōmushō Tōkeikyoku 総務省統計局 (Statistics Bureau, Management and Coordination Agency), ed., Nihon chōki tōkei sōran 日本長期統計総覧 / Historical Statistics of Japan (Tokyo: Nihon Tōkei Kyōkai / Japan Statistical Association, 1987–88), 4:482–83. The book is bilingual. Statistics for 1942–45 are not included. ⮭

- Tsuboi Ryōhei 坪井良平, Bonshō to kobunka: tsurigane no subete 梵鐘と古文化:つりがねのすべて (Bells and ancient culture: All about hanging bells) (1947; Tokyo: Bijinesu Kyōiku Shuppansha, 1993), 23; Tsuboi Ryōhei, Nihon no bonshō 日本の梵鐘 (Japanese bells) (Tokyo: Kadokawa Shoten 1970), 68–69. Tsuboi accounts for a total of 1,132 bells made in Japan from the seventh century until 1615, including those extant and those known only through records. Over 500 pre-1615 temple bells still exist in Japan. ⮭

- Hashizume Kinkichi 橋爪金吉, Bonshō junrei 梵鐘巡礼 (Bell pilgrimage) (Tokyo: Bijinesu Kyōiku Shuppansha, 1976), 19–20. In Kyoto, bells from the head temples of each main school of Buddhism were also exempt. ⮭

- Sherry Fowler, “The Literary and Legendary Lives of the Onoe Bell: A Korean Celebrity in Japan,” Archives of Asian Art 71.1 (2021): 57. ⮭

- Tsuboi Ryōhei 坪井良平, Keichō matsunen izen no bonshō 慶長末年以前の梵鐘 (Osaka: Tōkyō Kōko Gakkai, 1939). ⮭

- Tsuboi Ryōhei, Bonshō to kobunka, 5–6, 23–24. ⮭

- Tsuboi Ryōhei, “On Japanese and Korean Bells,” Bonshō 11 (1999): 85; lecture presented to the Asiatic Society of Japan on March 30, 1948. Also published in Tsuboi Ryōhei 坪井良平, Itsubō shōmei zukan 佚亡鐘銘図鑑 (Illustrated guide to lost bell inscriptions) (Tokyo: Bijinesu Kyōiku Shuppansha, 1977), xii. Tsuboi makes similar disparaging remarks about Edo-period bells in Bonshō to kobunka, 271. ⮭

- James Ketelaar, Of Heretics and Martyrs in Meiji Japan: Buddhism and Its Persecution (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990), 3–5, 55–56. ⮭

- Ogata Rikichi, Maboroshi no bonshō, 31–32, 37, 260. ⮭

- Ogata Rikichi, iv, 27, 32, 260–329. ⮭

- Ogata Rikichi, 34–38. ⮭

- Ogata Rikichi, i–ii. ⮭

- Manabe Takashi and Hanabusa Kenjirō 眞鍋孝志 and 花房健二郎, Edo Tōkyō bonshō meibunshū 江戸東京梵鐘銘文集 (Collected inscriptions of Edo bells from Tokyo) (Tokyo: Bijinesu Kyōiku Shuppansha, 2001), 1. ⮭

- On the functions of ringing bells, see Sherry Fowler, “Saved by the Bell: Six Kannon and Bonshō,” in China and Beyond in the Mediaeval Period: Cultural Crossings and Inter-regional Connections, ed. Dorothy C. Wong and Gustav Heldt (New Delhi: Manohar; Amherst, NY: Cambria, 2014), 333, 335–37. ⮭

- “Bonshō ikka no genzoku shiki” 梵鐘一家の還俗式 (Ceremonies for a family of bells to return to secular life), Shashin shūhō 151 (January 15, 1941): 4–5; David C. Earhart, Certain Victory: Images of World War II in the Japanese Media (Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, 2008), 130. Earhart translated the title of the article he referred to as “A Family of Bells Leaves the Temple and Reenters Society” and translated the part of the article I quote. ⮭

- “Sakimori no buki to shite: ōshō no daibonshō wa kakukataru” 防人の武器として:応召の大梵鐘はかく語る (As a defender’s weapon, great conscripted bells speak), Asahi gurafu, no. 1000 (January 27, 1943): 12–13. ⮭

- See Fowler, “Literary and Legendary Lives of the Onoe Bell.” ⮭

- Ogata Rikichi, Maboroshi no bonshō, 23, fig. 38, and 201. The bell dates to 1741 (Kanpō 1). ⮭

- See Fabio Rambelli, Buddhist Materiality: A Cultural History of Objects in Japanese Buddhism (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2007), 218–58; and Christine M. E. Guth, “Theorizing the Hari-kuyō: The Ritual Disposal of Needles in Early Modern Japan,” Design and Culture 6.2 (2014): 169–86. ⮭

- Ishikawa Kōtoku, “Bonshō to heiwa,” 1. See also Sugiyama Hiroshi 杉山洋, “Bonshō” 梵鐘 (Bells), Nihon no bijutsu 355 (December 1995): 75, fig. 135. ⮭

- Ogata Rikichi, Maboroshi no bonshō, 12, fig. 17, and 206. The bell dates from 1824 (Bunsei 7). ⮭

- Ibuse Masuji 井伏鱒二自, Ibuse masuji jisen zenshū 井伏鱒二自選全集 (Self-selected complete works of Ibuse Masuji) (Tokyo: Shinchōsha, 1985–86), 2:245–55; Keiko M. Takioto, “Kanekuyō no Hi (The Funeral of a Temple Bell) by Ibuse Masuji,” Japan Studies Association Journal 13 (2015): 25. Ibuse is most famous for his 1966 novel Black Rain. ⮭

- In the sexagonary cycle there is no “fire-sheep” year in the Meiwa era, but 1787 in the following Tenmei era is a fire-sheep year. Ibuse may have deliberately made this error to bolster the two men’s disagreement. ⮭

- Since the word nensho 念疏 is not used in Buddhist literature, Ibuse must have invented the title. In response to his survey, Ogata Rikichi provides descriptions of the send-off ceremonies, which did not all follow the same format; Maboroshi no bonshō, 145–56. ⮭

- Takioto, “Kanekuyō no Hi,” 42. ⮭

- John Whittier Treat, Pools of Water, Pillars of Fire: The Literature of Ibuse Masuji (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1988), 130–31, 270n20. ⮭

- Shinpen musashi fudokikō 新編武蔵風土記稿, vol. 22, Katsushika-gun 葛飾郡, no. 3, Kamichiba-mura 上千葉村, ed. Hayashi Jussai (Tokyo: Naimushō Chirikyoku, 1884), 10. ⮭

- Kakihana Masahiro 垣花昌弘, “Naranu kane, sensō no kioku, konkurisei, kinzoku kyōshutsu no daitai, Fukuoka no nijūyon tera” 鳴らぬ鐘、戦争の記憶、コンクリ製、金属供出の代替、福岡の24寺 (Bells that don’t ring and records of war, a concrete alternative to metal conscription at 24 Fukuoka temples), Asahi shinbun, Seibu, August 12, 2015: 7. ⮭

- Itō Tomoaki 伊藤智章, “Sensō to heiwa manande inotte” 戦争と平和、学んで祈って (War and peace, learning and praying), Asahi shinbun, Nagoya, August 16, 2017: 15. ⮭

- Resonance: The Odyssey of the Bells, written and dir. by Paul W. Creager (Stillwater, MN: Square Lake Productions, 2008). Creager’s film documents the repatriation cases of the bells that had been taken to Duluth, Minnesota, and Topeka, Kansas. See also Mike Hall, “Return the Bell, Crew Says: USS Topeka Group Wants Role in Sending Temple Bell to Japan,” Topeka Capital-Journal, July 21, 1989: 1, 3. ⮭

- Author’s transcription from Resonance. ⮭

- For an overview of the history of spolia, see Richard Brilliant and Dale Kinney, eds., Reuse Value: Spolia and Appropriation in Art and Architecture from Constantine to Sherrie Levine (London: Routledge, 2011). ⮭

- Frederick Johnson, “Treasured Temple Bell Repatriated to Japan,” Topeka Capital-Journal, August 26, 1989: 1–2. ⮭

- “Temple Bell Takes Felker to Japan,” Topeka Capital-Journal, April 23, 1991: 1-D. A temple pamphlet titled “Bonshō no yurai” 梵鐘の由来 (Legacy of the bell) (Shizuoka, Shimizu: Myōkeiji, 1991) confirms the year of the dedication, as does the article “Kyōshutsu de yukue fumei no kane, gojūichinen no saigetsu koe hibiku” 供出で行方不明の鐘51年の歳月こえ響く (Lost conscripted bell rings after 51 years), Asahi shinbun, Shizuoka, May 2, 1991: 29. ⮭

- The Numagami family was an important group of casters in this area. See Tsuboi Ryōhei, Nihon no bonshō, 263. ⮭

- In conversation with the author, July 7, 2018. ⮭

- Manabe Takashi transcribes the entire inscription, which is mainly about the merit of ringing a bell to end suffering and includes a story modified from the eleventh-century text Chanyuan qinggui 禪苑淸規 (The rules of purity of the Chan Monastery); Edo Tōkyō bonshō meibunshū, 107. On the latter text’s connection to bells, see Fowler, “Saved by the Bell,” 335–36. ⮭

- “Shinjuku, umi o watatta kane, kyōshutsu” 新宿・海を渡った鐘、供出 (Shinjuku, a bell that crossed the sea, conscripted), Asahi shinbun, Tokyo, August 14, 1988: 21. ⮭

- “Temple Bell Given to I.S.,” Ames (IA) Daily Tribune, August 3, 1948: 1. ⮭

- “NROTC Receives Jap Temple Bell as War Memento,” Iowa State Daily (Ames), July 29, 1948: 1; “Japanese Temple Bell,” Iowa State Daily, July 31, 1948: 1. ⮭

- James Leftwich Lee Jr., “A Century of Military Training at Iowa State University, 1870–1970” (PhD diss., Iowa State University, 1972), 297. ⮭

- “Temple Bell Being Sent to Japan,” Ames Daily Tribune, July 24, 1962: 1. ⮭

- “Story of Japanese Bell Told,” Ames Daily Tribune, July 26, 1962: 1. ⮭

- Norman Erbe, “Remarks by the Honorable Norman A. Erbe, Japanese Friendship Bell Dedication,” Des Moines, IA, October 17, 1962, State Historical Society of Iowa, https://iowaculture.gov/sites/default/files/history-education-pss-corn-erbe-transcription.pdf. ⮭

- “Beikoku kaeri no kane ni shōrō ga kansei, Shinjuku no Shōjuin” 米国帰りの鐘に鐘楼が完成、新宿の正受院 (Bell tower completed for bell returned from United States, Shōjuin in Shinjuku), Asahi shinbun, Tokyo, December 26, 1964: 16. ⮭

- On friendship bells, see Miriam Levering, “Are Friendship Bonshō Bells Buddhist Symbols? The Case of Oak Ridge,” Pacific World: Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies, 3rd ser., no. 5 (Fall 2003): 163–78. ⮭

- Tōto saijiki 東都歳事記 (Record of annual events in the eastern capital), ed. Saitō Gesshin et al. (Edo: Suharaya Mohē: Suharaya Ihachi, 1838), 1:14; Ikeda Yasaburō, ed., Nihon meisho fūzoku zue 日本名所風俗図会 (Illustrated guides to famous places and customs in Japan) (Tokyo: Kadokawa Shoten, 1979–1988), 3:119. ⮭

- Manabe Takashi, Edo Tōkyō bonshō meibunshū, 64–65. ⮭

- “Long-Lost Bell Returned,” Highlights: Office of the High Commissioner Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands, Saipan, Marianna Islands, June 1, 1974: 6; “Japanese Visitors Donate WWII Memorabilia,” Saipantribune, January 21, 2005, https://www.saipantribune.com/index.php/a2101c90-1dfb-11e4-aedf-250bc8c9958e/. ⮭

- “Jōshū Nanyōji no shōrō rakkeishiki” 浄宗南洋寺の鐘楼落慶式 (Bell tower dedicated at Jōdo school temple Nanyōji), Chūgai nippō, December 7, 1937: 2. ⮭

- Harold J. Goldberg, D-Day in the Pacific: The Battle of Saipan (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2007), 109–10. ⮭

- “Kiyoshi Hirano: Stockton JACLer, Dubbed Stockton’s Henry Kissinger, He Negotiates Return of Temple Bell,” Pacific Citizen (Los Angeles), August 9, 1974: 3. ⮭

- “Temple Bell in Money Trouble,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, June 18, 1948: 2. ⮭

- “Saipan no kane kaerazu” サイパンの鐘帰らず (Saipan bell does not go home), Asahi shinbun, June 18, 1948: 2. ⮭

- “Bunkyō no ne kaeshite: bonshō no yukue wa Beikoku” 文京の音かえして、梵鐘の行方は米国 (Instead of sounding in Bunkyō, the bell is in the United States), Asahi shinbun, November 17, 1973: 21. ⮭

- Jerry Belcher, “A Treasury of Odd Items Go on Auction,” San Francisco Examiner, January 24, 1974: 21. The failed maritime museum was planned for Oakland’s waterfront entertainment district called Jack London Square. See also “Kiyoshi Hirano,” 3. ⮭

- “For Him, the Bell Tolls,” Rotarian 128 (May 1976): 50; “Kiyoshi Hirano,” 3. ⮭

- “Long-Lost Bell Returned,” 6. ⮭

- “‘Anjū no hibiki’ fukkatsu ‘Han taiheiyō no kane’ taibō no shōrō” 安住の響き、復活「汎太平洋の鐘」に待望の鐘楼 (The sound of peace: The long-awaited resurrection of the bell tower for the “Pan-Pacific Bell”), Asahi shinbun, February 28, 1982: 21. ⮭

- For the full inscription, see Manabe Takashi, Edo Tōkyō bonshō meibunshū, 166. ⮭

- Ishida Hajime 石田肇, “Modotekita kyōshutsushō: Bunkyōku Hakusan no Nensokuji shō” 戻ってきた供出鐘:文京区白山の念速寺鐘 (Return of a conscripted bell: The Nensokuji bell of Hakusan, Bunkyō-ku), Bonshō 10 (May 1999): 81 and photograph on 82. ⮭

- Hanabusa Kenjirō 花房健次郎, “Saitama-ken (Musashi no kuni) no Edo jidai shōmeishū (ichi)” 埼玉県 (武蔵国) の江戸時代鐘銘集 (一) (Edo-period bell inscriptions in Saitama Prefecture [Musashi Province]) (1), Bonshō 18 (October 2005): 78–79. ⮭