As the digital shift continues to influence how academics conduct and present research, online exhibition has become an important tool to make rare archival materials and information about them accessible. The digital exhibition Tekagami & Kyōgire: The University of Oregon Japanese Calligraphy Collection (fig. 1) embraces the possibilities of these new modes of teaching and scholarship, vividly portraying practices of calligraphy preservation, appreciation, and text reuse through two of the University of Oregon’s prized archival holdings: an album known in Japanese as tekagami 手鑑 (lit., “mirror of hands”) containing 319 calligraphy fragments, and a series of 36 mounted fragments of calligraphy known as kyōgire 経切 (lit., “sutra cuttings”). The former is held by the Knight Library Special Collections and University Archives while the latter belongs to the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art on campus. Together, these objects represent a diverse body of written and material history, comprising poetic works, personal correspondence, spiritual texts, and other items created between the eighth and seventeenth centuries.

Tekagami & Kyōgire began in 2017 as a part of a multi-project initiative at the University of Oregon supported by an Andrew W. Mellon Foundation grant to fund faculty-organized public-facing digital humanities projects that enhance cooperation across library and museum collections. Launched in 2020, the project is led by Dr. Akiko Walley (Maude I. Kerns Associate Professor of Japanese Art, Department of the History of Art and Architecture, University of Oregon) and showcases important cultural materials of the Knight Library and the Schnitzer Museum. Far from a partnership in name only, Tekagami & Kyōgire embodies the extensive shared labor necessary to undertake a combined digitization and digital exhibition project from start to finish, with roughly twenty technical partners listed in its acknowledgments and a number of others (mostly in Japan) cited as crucial to the research process.

The project is built with Omeka S, an open-source content management platform designed specifically for the exhibition of digital collections and web-based publishing; the S version is geared toward institutions that wish to host multiple sites using an Omeka framework that enables them to share resources across projects. In the case of materials related to Japan and East Asia at the University of Oregon, this includes the Yōkai Senjafuda digital exhibit on supernatural creatures, led by Dr. Glynne Walley. One of the benefits of using Omeka for these exhibits is its ability to easily integrate plug-ins to showcase high-resolution images; Tekagami & Kyōgire uses Mirador, a IIIF (International Image Interoperability Framework) viewer, to host its digitized materials in a virtual environment where they can be easily indexed and examined alongside their associated metadata (fig. 2).

As the title of the website suggests, Tekagami & Kyōgire is divided into two main sections. Both the Tekagami and Kyōgire tabs include explanations of the materials of each genre, detailed examinations of certain characteristics found within these and similar bodies of materials (for tekagami, identification slips pasted into the album, and for kyōgire, types of sutra fragments), a closer look at the collections specifically held at the University of Oregon, and short “Scholar’s Pick” commentaries on one or more calligraphy fragments. Each of these subsections includes further thematic explorations that highlight the tenuous relationship between the historical record and artistic connoisseurship illustrated by tekagami and kyōgire, taking the reader through the lives and afterlives of calligraphic works with generous contextual information. Tekagami & Kyōgire contains a wealth of complex information that has been carefully researched and linked to several hundred objects—no easy task. Each collection featured could be the subject of a monograph on its own. Walley has therefore undertaken a formidable challenge in making an inherently fragmented and disjointed assemblage of artifacts into a legible narrative for her audience.

There is no denying the value of such a media-rich, open-access contribution to research on the written word across centuries. The project will have an even greater impact when developers have addressed some of the common challenges inherent to ready-to-use platforms such as Omeka, which is not particularly intuitive for the uninitiated visitor. The exhibition’s digital content requires guidance to help readers navigate both Omeka and Mirador environments. First-time visitors would benefit from more explanation on the landing page to complement the introduction to the exhibition and collections. For example, it would be helpful to have instructions on using the navigation bar to select individual topics, and on moving through the essays using the somewhat elusive “Next” buttons placed at the bottom right-hand corner of each page. The media content integrated into each page would also benefit from varied placement and simple captions or figure numbers; images and YouTube embeds provide rich complements to the explanatory text, but float (sometimes at the end of a page) without direct identification of their collection number or content, leaving the viewer to guess at their purpose based on the essays.

Had an explanation of Omeka’s metadata capabilities been provided at the outset, users might know that clicking images not presented directly in Mirador (fig. 3) will take them to a separate page showcasing the details of the artifact and the IIIF viewer that can be used for closer inspection of the individual fragments and the pages on which they have been preserved (crucial for those studying the materiality of tekagami and kyōgire). The metadata pages, too, could benefit from some refinement, as the image viewer appears buried at the bottom of a lengthy metadata page that may be somewhat redundant, given that Mirador features a collapsible “more information” tab with each item’s associated metadata (see fig. 2). How to use the Mirador viewer is briefly explained part way through the last essay of the third tekagami subsection, though it is better suited to prefatory content.

The “Browse” and “Advanced Search” options are perhaps the most in need of modification to improve user experience and content (fig. 4). There are 423 items digitized across five pages under the “Browse” tab but no clear explanation of the naming conventions used for titling each image or the differences between the sorting options offered—does “identifier” refer to the item number as it appears in the collection or as it has been labeled in the database for metadata purposes? Are they the same? Is “class” a vestigial category, given that all items are images, or does it distinguish between “image” and “physical object”? Is the “date of creation” the date of the object or of the digital surrogate’s creation? The “advanced search” option has yet to be refined, as the full-text search is limited to English-language terms (sutra will return results while 経 will not, despite the availability of bilingual metadata), and the “item set” option, a beneficial function of Omeka’s thematic exhibition building that allows the creators to make tagged subcategories of images within their collection, mistakenly retains the labels used from the Yōkai Senjafuda digital exhibit, rather than Tekagami & Kyōgire.

Given the great volume of sophisticated content, some minor tweaks might further assist viewers, such as adjusting difficult-to-read text to be single spaced (typical for web publishing) and avoiding colors that present extreme contrasts or closely match the near-black background. Additional subheadings within each topical page would also better guide readers through the wealth of information provided.

Put in perspective, these issues are the tip of a vast iceberg of invisible labor that characterizes most digital projects: high-resolution scanning, image editing, digitization, database development, background research, metadata creation and standardization, translation, content organization, essay writing, IIIF integration, platform development, and all the collaborative steps in between by the specialists who make these processes possible. Walley herself notes that this exhibit should be considered a work in progress and part of ongoing research that will be refined in time.

One of the greatest assets of Tekagami & Kyōgire is its opportunities for multidisciplinary education and research. The exhibition will be relevant to scholars, students, and casual readers with interests in literature, art history, calligraphy, materiality, religious studies, aesthetics, textuality, intra-Asian cultural exchange, digital preservation, and more. These collections inherently showcase the intersection of diverse fields, and the availability of high-resolution images allows for their study if one is not able to physically travel to the university archives or museum.

Another, though less obvious, asset of the project is that all of the images from the two collections have been made IIIF compatible. IIIF manifests allow users to drag and drop images into other IIIF viewers for their own exhibitions or research, even comparing the fragments with other IIIF-compliant digitized materials located at any archive in the world. This functionality is a boon to specialists in Asian manuscript studies and has been used widely for many years by papyrologists and codicologists studying page fragments, recycled paper, and lost folios of texts from the Latin West and North Africa.

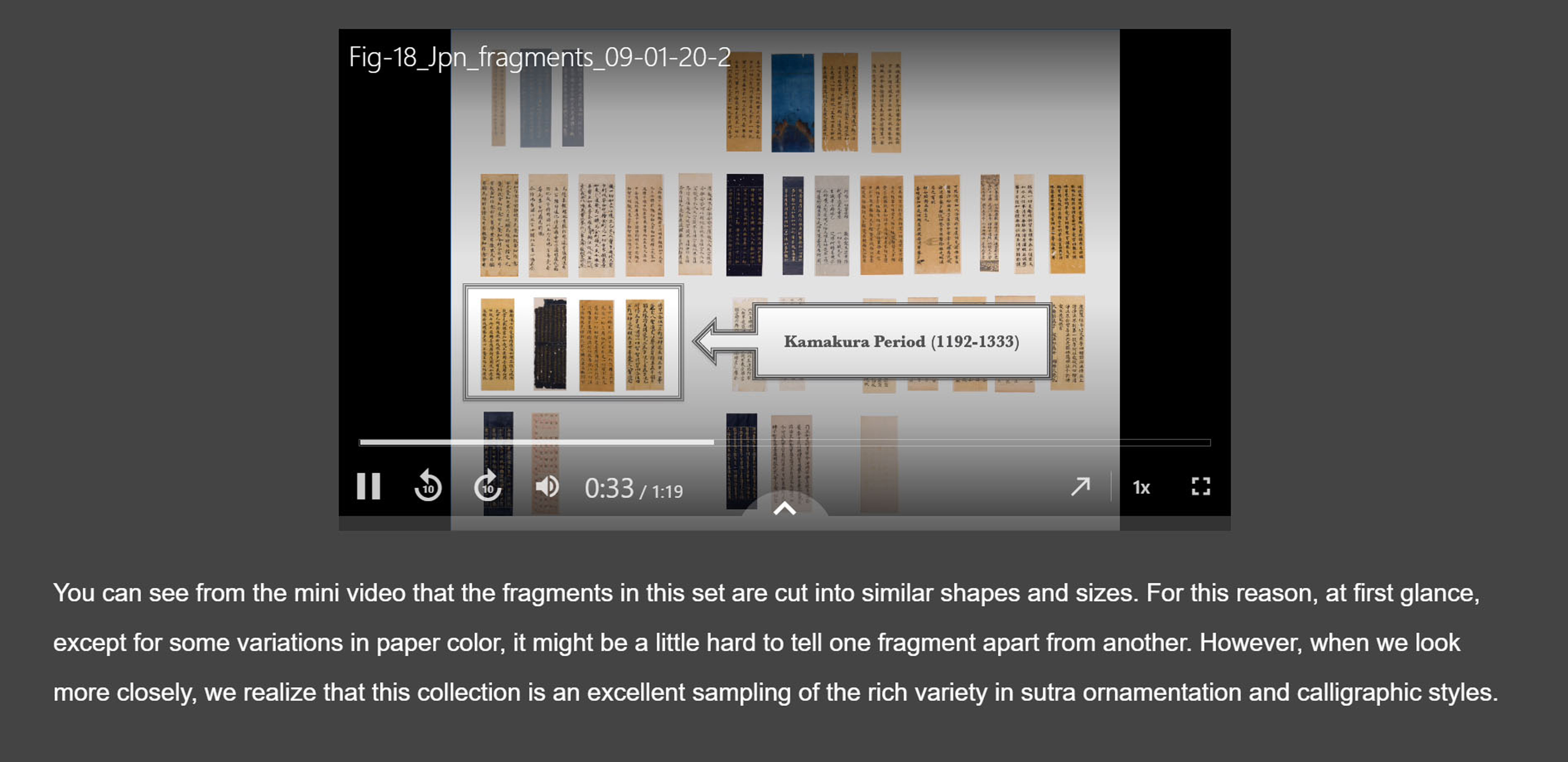

As the site continues to evolve, it would be invaluable to learn more about the process of creating the exhibition and more of Walley’s research findings, particularly those that could take advantage of IIIF functionality to link tekagami and kyōgire to other digitized collections for comparison and contrast, perhaps even reuniting disassembled texts. The Bibliography page also features a subsection, “Tekagami and Calligraphy Audio/Video,” that hosts a variety of introductory videos that might be better leveraged throughout the site and expanded upon; short visual complements such as that of the kyōgire fragments video (fig. 5) tucked away at the end of the “Types of Kyōgire Fragments” page entice viewers to explore further and showcase other multimodal forms of learning from the collections.

Technical and aesthetic stumbling blocks aside, one should not lose sight of the immense and time-intensive intellectual and digital labor underpinning Tekagami & Kyōgire. Walley’s work joins recent and important scholarly dialogues on fragmentation, including Ed Kamens’s Tekagami-jō Project's on the album held by the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University and Halle O’Neal’s work on Buddhist memorial letters and palimpsests.1 I look forward to the Tekagami & Kyōgire project’s growth as Walley’s collaborations continue and more is uncovered about the lives and afterlives of these fascinating fragments.

Author Biography

Paula R. Curtis, PhD is a historian of medieval Japan. She is presently the Yanai Initiative Postdoctoral Fellow and Lecturer with the Department of Asian Languages & Cultures at the University of California, Los Angeles. Her current book project focuses on metal caster organizations from the twelfth to sixteenth centuries and their relationships with elite institutions. Dr. Curtis collaborates on and manages several online projects, including the Digital Humanities Japan initiative, online databases for digital resources, employment opportunities related to East Asia, and the blog What can I do with a B.A. in Japanese Studies. E-mail: prcurtis@umich.edu

Notes

- Transcriptions of Yale’s tekagami album can be found on their open-access Ten Thousand Rooms platform (https://tenthousandrooms.yale.edu/project/tekagami-jo-shou-jian-tie-project). O’Neal’s “Inscribing Grief and Salvation: Embodiment and Medieval Reuse and Recycling in Buddhist Palimpsests” (Artibus Asiae 79, no. 1 [2019]: 5–28) offers a fascinating examination of object biographies and premodern ritual reuse. ⮭