Antecedents: India in the United States

Commodities from India, particularly textiles, had entered American markets from the mid-eighteenth century onward, principally through the New England trading centers that established channels for trade with merchant communities based in Indian port cities.1 While imports from India included raw materials like linseed oil and jute, luxury textiles such as shawls from Kashmir continued to be coveted. Additionally, returning American mariners would often bring back “curiosities,” gifts, and souvenirs. These so-called curiosities, as distinct from traded commodities, were a peculiar class of object that often comprised the unfamiliar, the unusual, or the exotic, and whose lack of express use value may have been superseded by their tangible connection to an imagined elsewhere.2

In the second half of the nineteenth century, following the model established by the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London, the most expedient mode for audiences in the rapidly developing cities of Europe and the United States to imagine faraway lands was through curiosities and commodities exhibited at events such as World’s Fairs. India was presented to Americans in this manner at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition in 1876, and more spectacularly at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, when a consortium of Indian businessmen and heads of princely states supported the dedicated India Building. The goods and objects available for sale and display revealed “the industrial skill of the natives of Hindostan,” which included elaborately wrought silverware, fine silks, light muslins, intricate ivory carvings, inlaid boxes, sandalwood furniture, rugs, and fragrant teas, all displayed in visually dense and sumptuous interiors, literally evoking a bazaar and serving to confirm the Orientalist fantasy of India in terms of a surfeit of sensorial experiences.3 Completing the scene was an exhibit described in the official directory as “India in a nut shell,” which consisted of models and dioramas illustrating Indian architecture, sculpture, and people.4 For the fairgoer this type of display served as a substitute for travel while establishing an ethnological lens through which India could be viewed at a safe remove (fig. 1).5

If the Columbian Exposition presented an abundantly sensual and material view of India, at the same time a more spiritual perspective was being offered at the 1893 World’s Parliament of Religions, through the words of Swami Vivekananda (1863–1902). The parliament, which was held in conjunction with the fair in Chicago, included representatives from several religions from across the world, and the young monk was one of the Indian delegates. Eloquent and erudite, Vivekananda’s addresses presented spiritual values that were tolerant and universal, and found immediate resonance with contemporary audiences. Following the parliament, he quickly became a celebrated and in-demand speaker among the American cognoscenti and launched his national tour of lectures in Detroit in February 1894 (fig. 2).

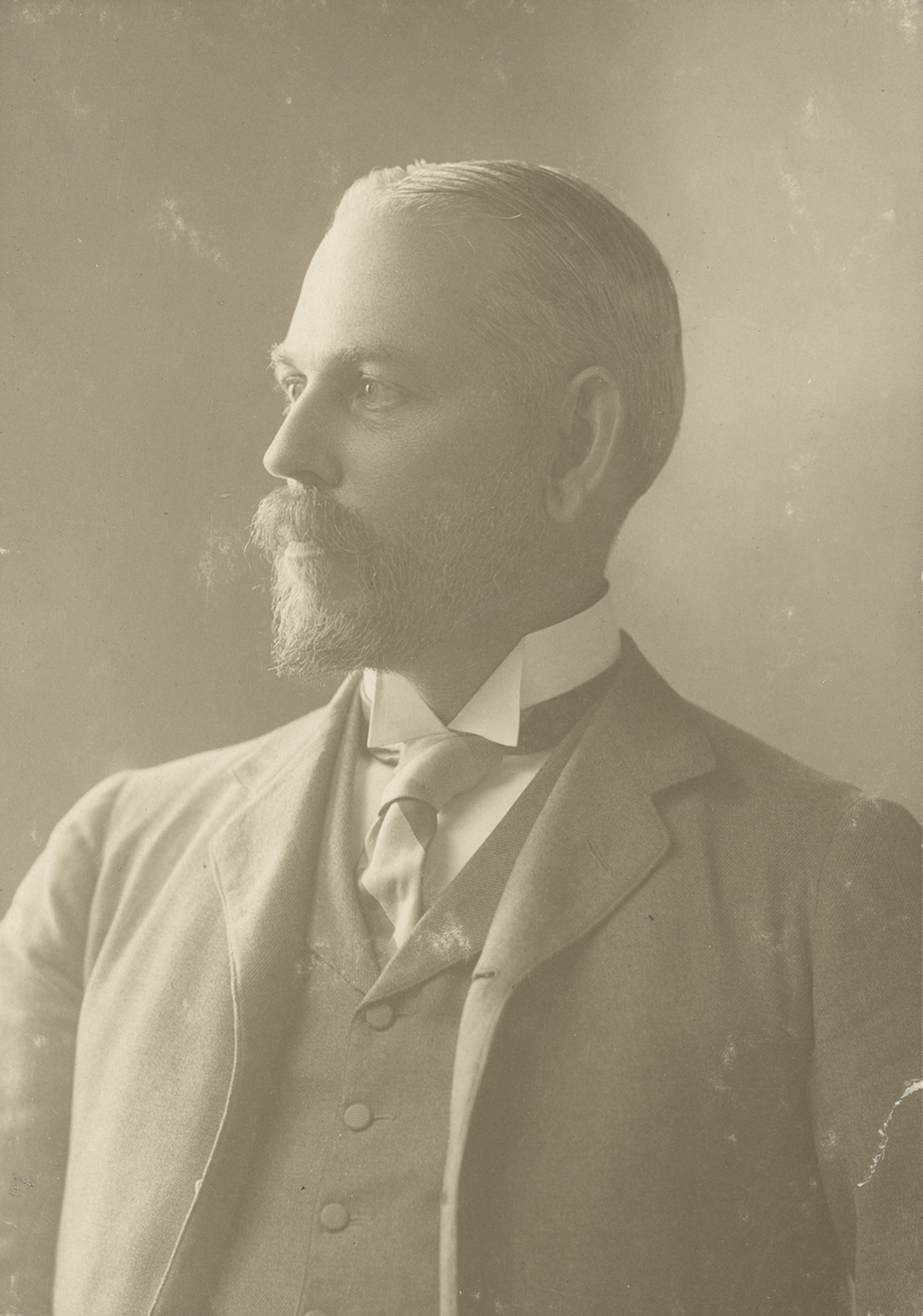

By 1893, Charles Lang Freer could aptly be described as a notable collector of American paintings (fig. 3). A successful businessman from humble beginnings, he had made his fortune in the railroad industry alongside his mentor, business partner, and lifelong friend Colonel Frank J. Hecker (1846–1927). In 1885 the two men had established the Peninsular Car Company, a railroad-car manufacturing company in Detroit, the thriving industrial city where they would build large bespoke homes on neighboring plots of land. Freer’s collecting began somewhat conventionally for a young man with newly acquired means, and while he initially limited himself to collecting European prints, by the late 1880s, under the influence of the Aesthetic movement he had expanded his interest to the works of American artists. By far the most impactful was James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903), the London-based American painter whom Freer met in 1890 and with whom Freer developed a profound artistic and personal rapport, eventually amassing over a thousand works by the artist. Freer had purchased the occasional object from Asia, notably acquiring a painted Japanese fan as early as 1887, but Whistler is often credited with being an early catalyst for Freer’s turn to East Asian material via the former’s enthusiasm for Japanese prints.6 Freer would be friend and patron to other American artists as well: Frederick Stuart Church (1842–1924) was a frequent travel companion and correspondent, while Dwight William Tryon (1849–1925) and Thomas Wilmer Dewing (1851–1938) made paintings expressly designed for Freer’s new home on Ferry Avenue in Detroit. Thus, by the time of the World’s Columbian Exposition, paintings and etchings by Church, Dewing, Tryon, and Whistler were among the objects from Freer’s collections loaned to the exhibition. Although Freer’s diary entries cannot confirm that he saw the India Building or even attended the Parliament of Religions during his visit to Chicago in 1893, by 1894 he had hosted Swami Vivekananda at his home and ordered a two-volume set on the World’s Parliament of Religions, and later that year embarked on a journey to India.7

An American Traveler in India

“‘But you must have three weeks to do India properly’ her husband conceded, anxious to have it understood that he was no frivolous globe-trotter.”8

This snippet of after-dinner conversation from Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence, set in 1870s Gilded Age New York, draws a picture of the way traveling not just to Europe in the manner of the Grand Tour, but further afield to more remote places in Asia, including India, had come to hold a certain cultural cachet in American society. Following the quelling of the Revolt of 1857, most of the Indian subcontinent had come under the control of the British crown. The decades following the midcentury also saw an expansion of passenger rail networks that greatly facilitated transport through India. It was in this context of political stability and more efficient travel options that Thomas Cook began operations in India in 1881 and, as with Egypt in years prior, began marketing India to European and American travelers and tourists as a destination that could be visited with reliability and ease. The era also saw a proliferation of travel guides for and memoirs of travelers in India. The latter included missionaries, and we have some evidence through vouchers among Freer’s papers that he was aware of the work of American missions in India, having made a small donation to the missionary Hattie Standart and designated for her salary in India in January 1894.9 At the same time readers of Harper’s Weekly would have encountered the writings and illustrations of the American Orientalist painter Edwin Lord Weeks (1849–1903), who traveled to India several times from the 1880s onward (fig. 4).10 Weeks had also exhibited his paintings of India at the 1893 exposition alongside Freer’s loans.11 Thus, by the time Freer contemplated traveling abroad, the prospect of doing so for a person of his ilk was neither remote nor reckless, and indeed even among the art cognoscenti he had forebears in such an endeavor. A full decade earlier, in 1884, the Boston-based couple Isabella Stewart Gardner (1840–1924) and her husband, Jack, had also traveled to India, traversing similar routes and destinations.12

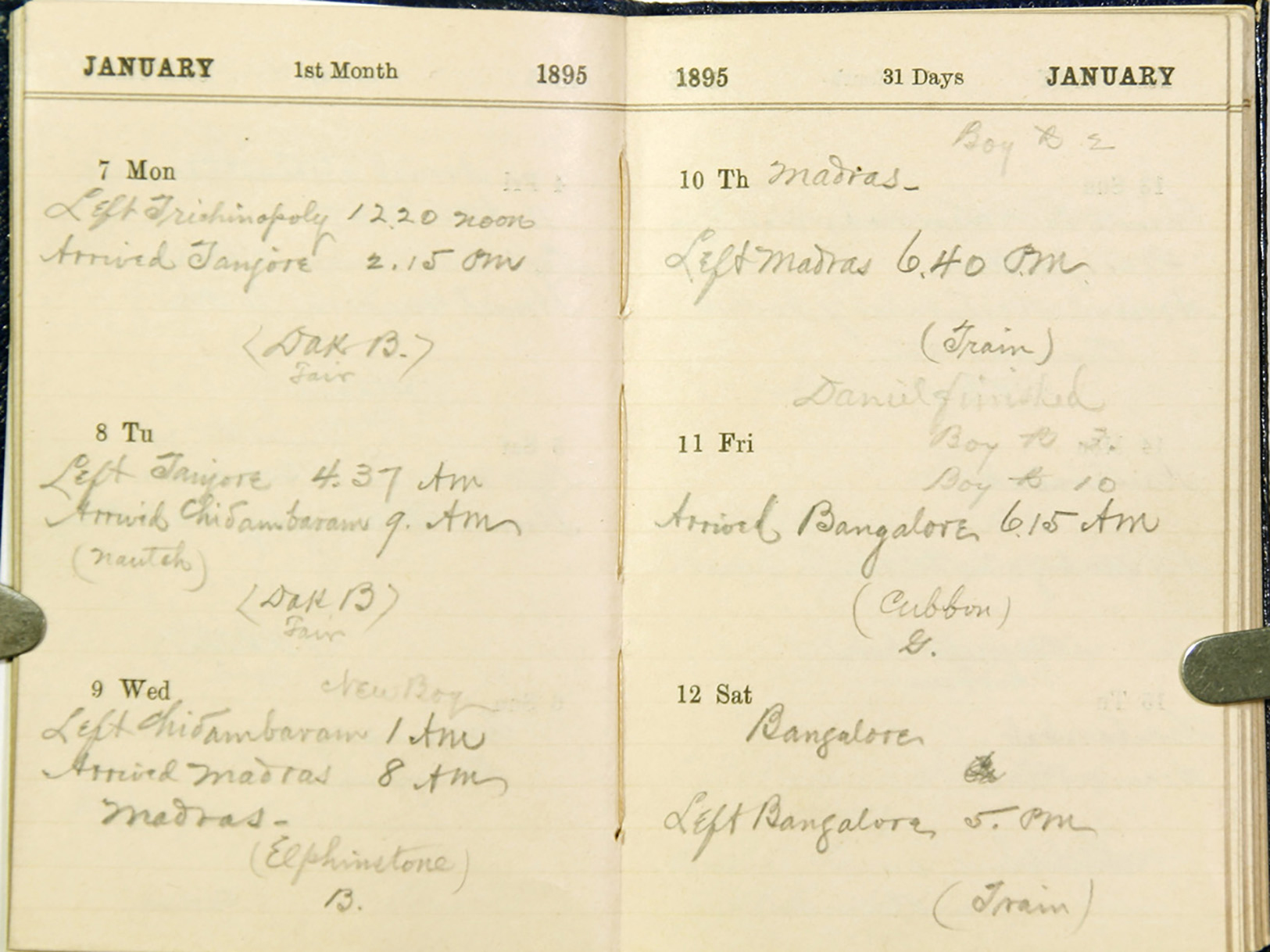

In the fall of 1894, Freer set forth for Europe, from whence he would embark upon his first travels to the East. A month before his departure, he sketched out his planned itinerary in a letter to Frederick Stuart Church: “On the 19th of September I expect to leave Detroit for New York, and on the 22nd, expect to sail for Italy. . . . This trip will probably be quite a lengthy one and will include France, India and possibly Japan. It will take the better part of the year.”13 His prediction for the length of his travels was accurate almost to the day, for he returned to his home in Detroit on September 12, 1895. If the letter to Church is any indication of his intentions, India was of certain interest and definitely on his itinerary, while Japan remained only a possibility at that moment. As his travel plans unfolded, Freer ended up spending a little under three months in India, from January to March 1895, when the weather was pleasant in the subcontinent, while the greater part of his time abroad was spent in Japan, from April to August of that year. This was the only time Freer experienced Asia primarily as a tourist, forming impressions and beginning his understanding of the different cultures with little initiation. By the time he returned to the East, over a decade later, his interest in Asian culture was better informed and had deepened. Moreover, in subsequent trips Freer’s reputation as a collector would precede him, and his access to and interests in places and people and their collections would be far more pointed. Freer’s accounts, too, would become more expository and refined, but at this early stage, during his first voyage, his correspondence was restricted to a few individuals, and his diary notations were minimal (fig. 5).

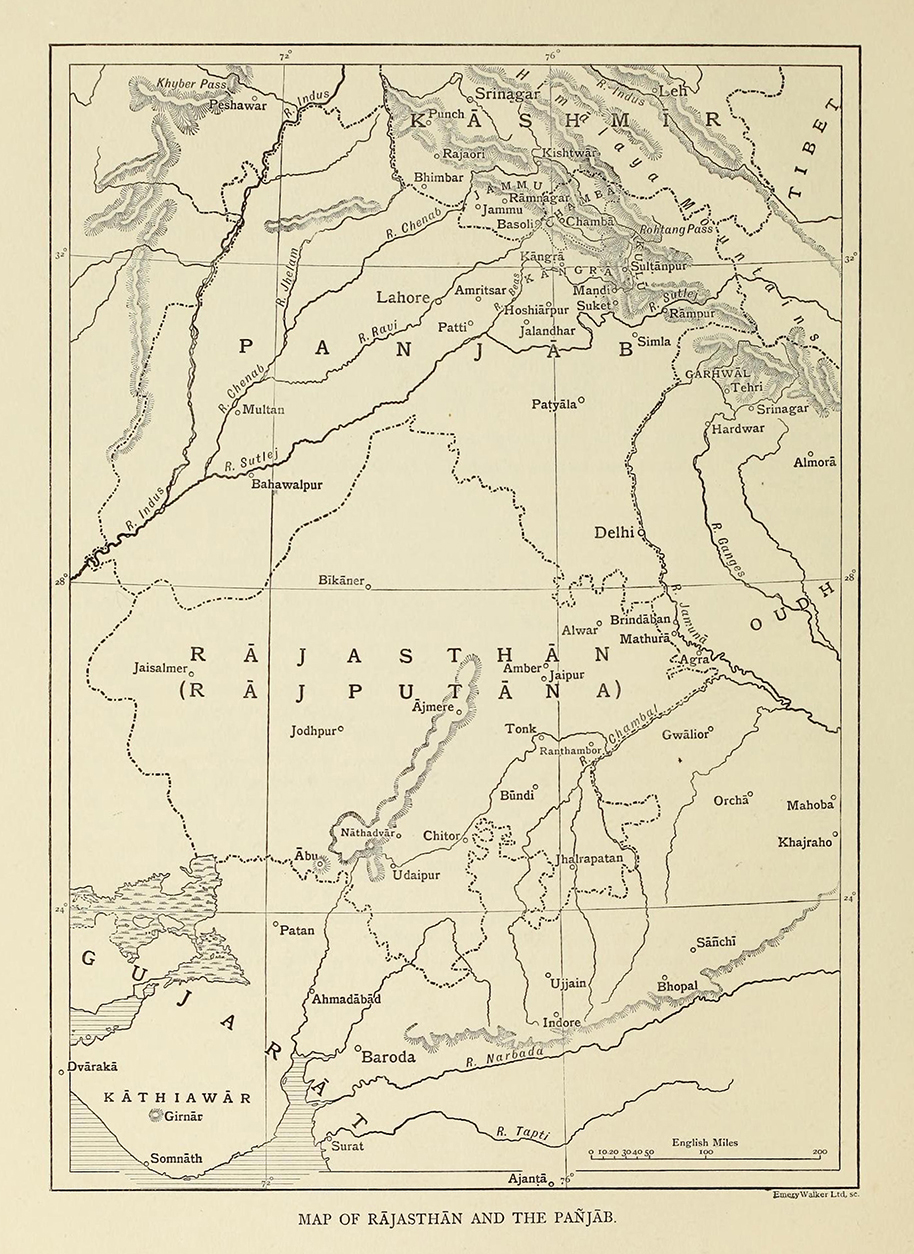

Freer’s diary entries do, however, enable one to trace his journey through the Indian subcontinent, while correspondence with Hecker gives some insight into his experiences and the impressions he was forming. Unsurprisingly for a first-time tourist whose outlook was inevitably mediated through guides, both published and personal, his descriptions were often clichéd and drew upon romanticized Orientalist tropes. Yet Freer’s enthusiasm was palpable in the repeated expressions of “fun” in his letters.14 He also found himself profoundly moved by the richness and diversity of all that he saw and absorbed it with frank interest and admitted naïveté.15 After having toured Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), and following a difficult sea voyage, Freer landed in southern India in the port city of Tuticorin (Thoothukudi), from where he began his travels moving northward. His tour of the major South Indian temple towns concluded upon arrival in Madras (Chennai), from whence he boarded a train for his onward journey, traveling via Bangalore, Hyderabad, Bijapur, and Pune to Bombay (Mumbai). All along the way he took in the expected sites, which ranged from the ancient (the Buddhist caves at Karli) to the modern (the Chowmahalla Palace). In Bombay Freer resided at the recommended Great Western Hotel on Apollo Road and used it as his base. He was also able to receive his mail in the city and took the opportunity to write to Hecker and reflect upon his experiences thus far. He then pressed on northward, reaching Ahmedabad by the end of January, from where he began his travels in the princely territories of Rajputana (now comprising mostly the state of Rajasthan). After visiting the Jain temples at Mount Abu, he proceeded to Jodhpur, where he was impressed by the wealth and generosity of the Jodhpur ruler Maharaja Jaswant Singh II (1838–1895), who extended to Freer the courtesy of the use of his private stables, his servants, and an English-speaking companion to show him all the sights of the region. In a letter to Hecker recounting his experiences in Jodhpur, Freer noted that “Jodhpore nobility are much interested in the proceedings of the parliament of religion held in Chicago.”16 Although he did not elaborate upon the matter, it nevertheless suggests that the subject, and perhaps even Freer’s own interactions with Swami Vivekananda a year prior, were topics of mutual interest or conversation, and certainly enough to warrant specific albeit fleeting reference in his correspondence.

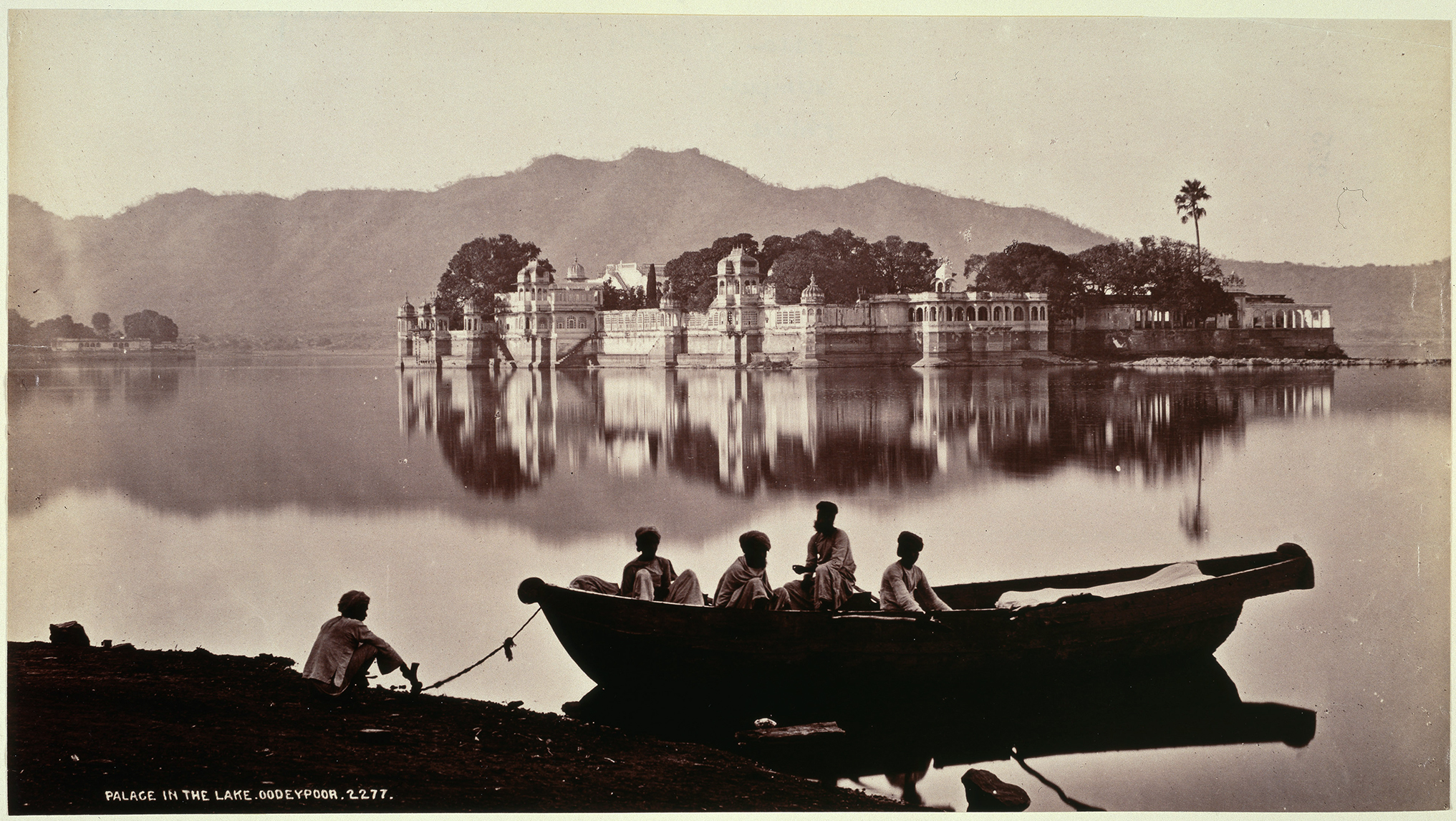

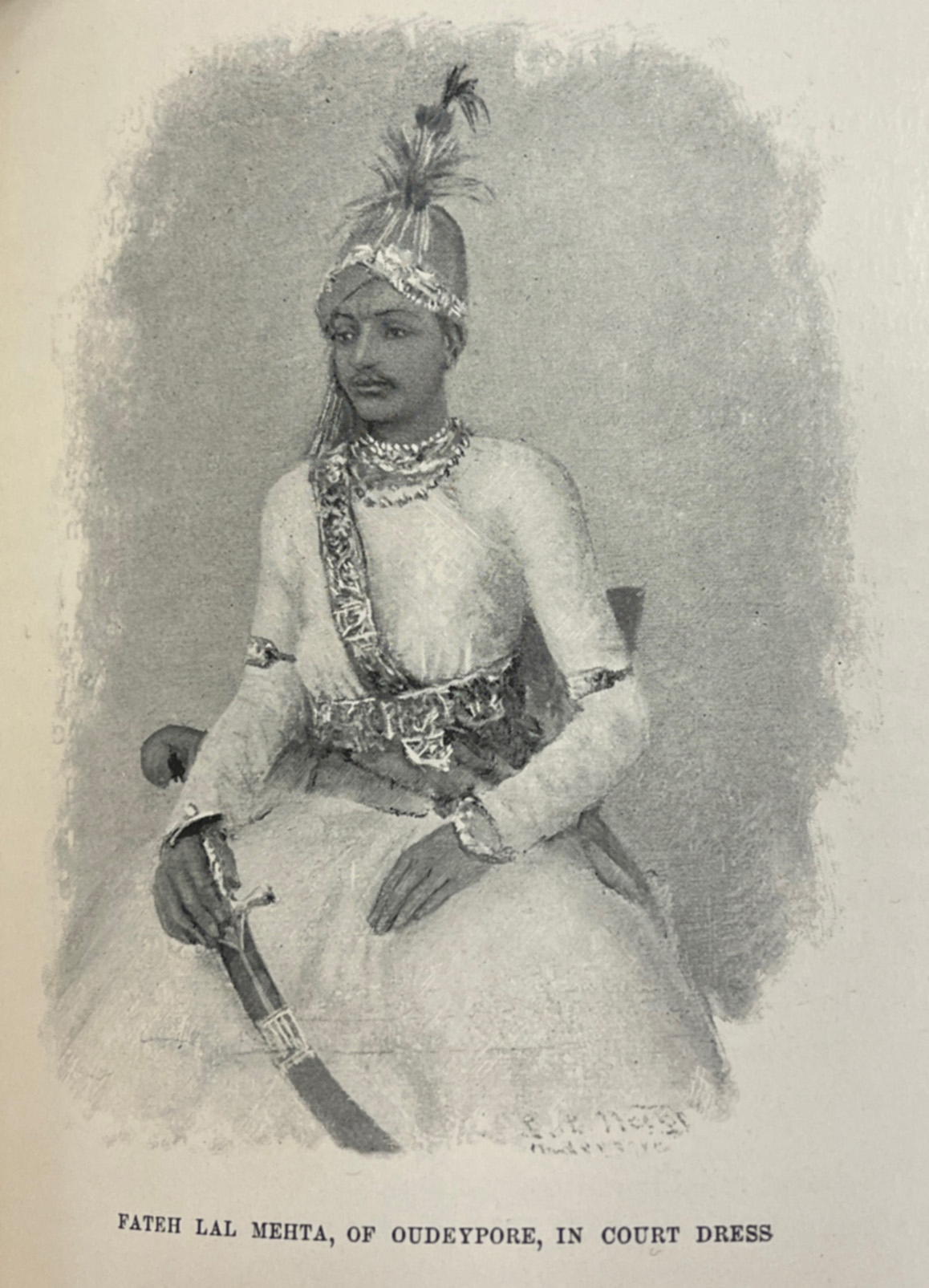

At this stage of his journey, after overcoming some initial obstacles, it seems that Freer greatly anticipated visiting “the City of Oodeypore [Udaipur] and its sights—said to be the most beautiful city in the world,” closely echoing guidebook descriptions of the famous city (fig. 6).17 In his letter to Hecker he continued, “Should I succeed in meeting there Fateh Lil Metha [sic], a young native prince, who is fond of Americans I will probably have another bang up event to add to those I have already struck while in Bombay.”18 Fateh Lal Mehta was the son of the prime minister and also the author of the only English publication on the city of Udaipur, titled the Handbook to Meywar and the Guide to Its Principal Objects of Interest (1888) (fig. 7).19 He and Freer did indeed meet, and Mehta with his connections facilitated what turned out to be an immensely pleasurable and memorable visit over five days in the region. Freer wrote effusively to Hecker, “I can scarcely ever hope for impressions of any earthly place more completely to my liking than those I expect always to cherish of Oodeypore.”20 Freer’s lasting regard for Mehta is evidenced in the correspondence that continued between the men, and Freer gratefully acknowledged receipt of a collection of photographic views of the city taken by the official royal studios that Mehta sent to his home in Detroit in 1896.21

Following his visit to Udaipur, Freer stopped at Alwar and although he was less taken with that city nonetheless took time to remark that “its copy of the Gulistan and splendidly illustrated Persian manuscripts, also its wonderful stable (unusual combination) are worth a long journey to see.”22 Here once again his account follows the directions of guidebooks that especially noted both the features that Freer mentions.23 The renown of the nineteenth-century copy of the Gulistan manuscript in the Alwar Library included its prominent mention in Thomas Hendley’s Ulwar and Its Art Treasures (1888). It would continue to be regarded favorably and was described in 1911 by Vincent Arthur Smith as “probably the best example of modern book illustration in the Indo-Persian style” in his A History of Fine Art in India and Ceylon: From the Earliest Times to the Present Day.24 In later years Smith’s book and his account of the Henry Bathurst Hanna collection, published in 1910, would be found in Freer’s library. In 1895, however, Freer’s passing remark in his letter to Hecker gives some suggestion that this was an early, or perhaps even the first, encounter with this style of Indian painting. Moreover, it raises the question as to whether the memory of having seen the Alwar Gulistan, with its reputation at the time as a quintessential exemplar of Indo-Persian painting, would have any bearing some years later on informing Freer’s interest in Hanna’s collection, which was primarily focused on Indo-Persian paintings and which also happened to include an illustrated copy of the Gulistan (see fig. 19).

Through the following weeks until the end of March 1895, Freer traveled across northern India, before gradually turning eastward. His diaries record that he visited Delhi, Lahore, Peshawar, Multan, Amritsar, Agra, Fatehpur Sikri, Lucknow, Benaras, and Calcutta, but neither his entries nor his letters recount in any detail all the sites he saw or his specific experiences. Nevertheless, it is likely that—in the manner of tourists of the day—he would have visited the Mughal palaces, mosques, and tombs including the Taj Mahal, the ghats in Benaras, and the birthplace of Buddha; and in his letters to Hecker some themes recur. Freer’s interest in architecture and interiors was elevated because of the planning around his home in Detroit, and so he wrote expressively to Hecker from the train station at Bankipore Junction: “I am daft on Indian architecture just now. It has so many fine points for domestic application and the time is not far distant in my opinion when modifications of it will be used to great advantage (artistically) in America.”25 Indeed, at the time that Freer penned these words, another intrepid American was bringing Indian elements into American interiors; Lockwood de Forest (1850–1932) had in the decade prior, along with Mugganbhai Hutheesing, established the Ahmedabad Wood Carving Company and had also exhibited their productions at the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893.26 Freer himself had admired the wood carving he had seen in Ahmedabad on his visit to that city.27

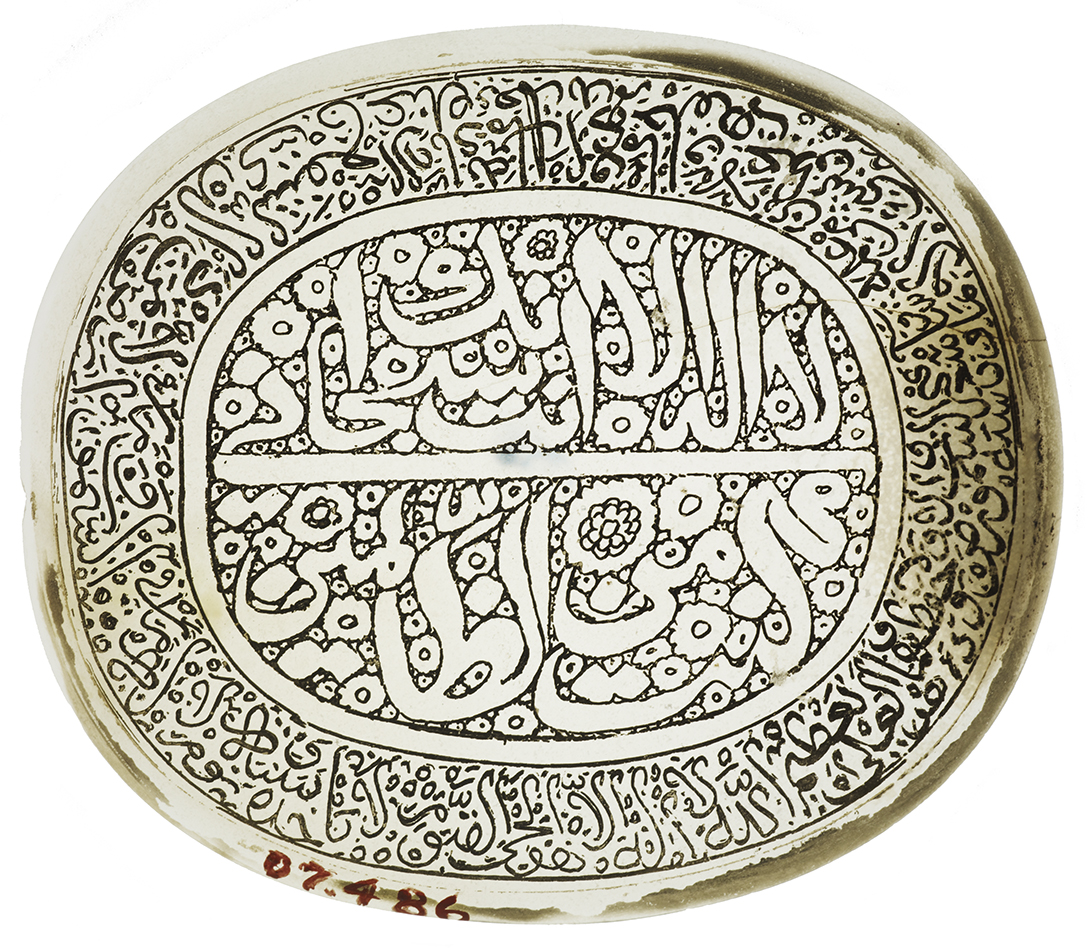

Another activity that Freer indulged in was the purchase of souvenirs and other mementos of his journey, including photographs. For the European or American traveler, India of the 1880s and 1890s was a destination not only for experiences but also for shopping to commemorate personal aspects of their journey. In this context Tina Choi has proposed that the souvenir functioned “as another kind of mediating object in a complicated cultural landscape, strategically situated between experience and expectation, at once actively mass-marketed and self-consciously traditional, sold in city shops as a symbol of an idealized village life.”28 Freer, like the Gardners before him, bought a number of souvenirs of his travels, both through establishments in larger cities that catered to Western travelers’ needs, ranging from silver objects, jewelry, and shawls purchased at J. P. Watson and Co. in Bombay to photographs purchased at the studios of Bourne and Shepherd in Calcutta.29 At the same time he had already begun to see himself as more discriminating in his tastes than his Gilded Age peers.30 Freer clearly delighted in the experience of smaller town bazaars, writing to Hecker from Multan, “In this sunny land virtue is easy, consequently, when I stumbled upon a superb lot of old tiles in this most famous land of tiles, I let slip again my resolution, to buy nothing during this trip—(The only thing that will stop me will be an exhaustion of funds, unfortunately, a condition becoming daily more a certainty).”31 Several letters to Hecker inform him to expect Freer’s purchases of “trinkets” and “skins” that he had instructed Watson to forward to Detroit. We also have evidence that while in Lahore Freer encountered the dealer Syed Bahadur Shah, for in the following year Shah would send to Detroit a collection of sixteen engraved stone amulets (fig. 8).32 Shah would go on to be an important source for Pahari paintings, including those purchased some years later by Ananda Coomaraswamy, from whose collection certain objects would eventually find their way into the Freer Gallery of Art.33

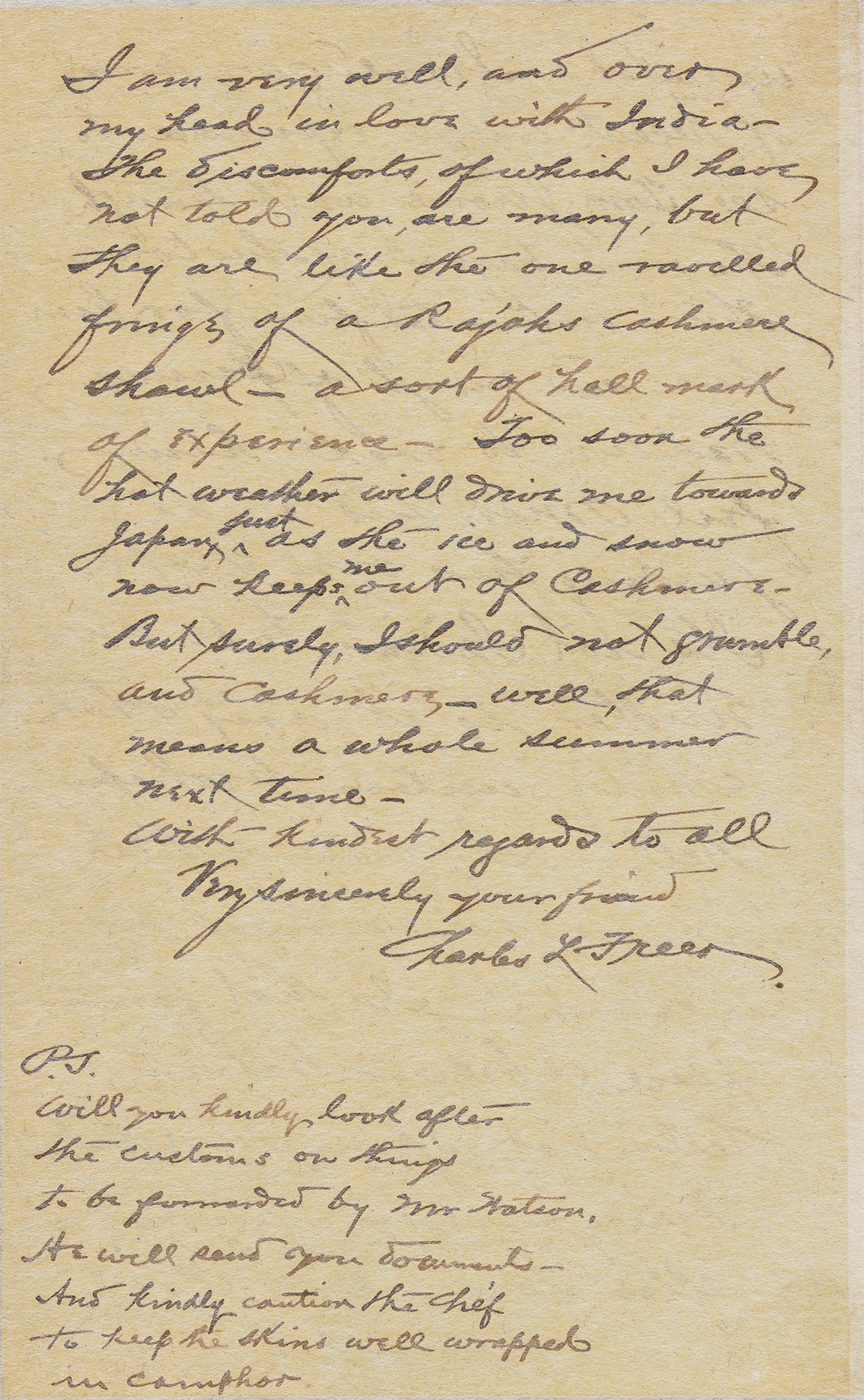

Freer’s packed itinerary and relentless pace eventually caught up with him, and by the time he reached Calcutta, he was having difficulty walking and was advised by a doctor to make a brief sojourn to recuperate in the hill station of Darjeeling. As he recovered, he wrote reassuringly to Hecker, “My sprained leg is practically well but I still tread carefully—Fever entirely gone—and I hope soon to regain all that these little ills of Hindustan took from me—mere nothings compared to what she gave me.”34 He finally left India on March 20, 1895, sailing back to Colombo before heading eastward, where he visited Hong Kong and Shanghai. Somewhat ironically, his glancing impressions of China at this stage left him unimpressed, and he noted that “India spoiled me for Chinese influences.”35 Japan was the intended destination, and while Freer looked forward to it, he did not expect his experiences of India to be surpassed: “I am very well, and over my head in love with India. The discomforts, of which I have not told you, are many, but they are like the one ravelled fringe of a Rajah’s cashmere shawl—a sort of hallmark of experience. Too soon the hot weather will drive me towards Japan just as the ice and snow now keeps me out of Cashmere. But surely, I should not grumble, and Cashmere— well, that means a whole summer next time” (fig. 9).36 The next time that Freer anticipated never came to pass, but even while in Japan he continued to reflect on his time in India and suspected that “Indian life and adventures will I think, leave more lasting and precious impressions in my mind. At any rate they will prevent indiscriminate affection for Japan.”37

Nevertheless, Freer would be profoundly moved by his experiences in Japan, and especially with the place and practice of Buddhism in Japanese culture.38 More significantly, he actively sought to develop and nurture his interest in Buddhism by seeking out resources upon his return to the United States. This was very much in keeping with the growing American interest in Eastern religions and spirituality, with which Freer was already somewhat acquainted prior to his travels. New England, especially Boston, was the American seat for these interests in the East, and given Freer’s frequent travels to the city on business and to see exhibitions, his proximity to this cultural environment shaped his tastes in a more defined direction.39 Specifically, his collection of art was enabled by the presence of key individuals in his milieu. Principal among these was Ernest Fenollosa (1853–1908), regarded at the time as the foremost authority on the art of China and Japan, and under whose tutelage and guidance Freer would develop his own approach to building a collection of Asian art (fig. 10). The two men met around the turn of the century, and as Kathleen Pyne has argued, Fenollosa’s aesthetic approach would enable Freer to conceive of a collection of art that spanned and reconciled a temporal and geographic range that eventually stretched from tenth-century China to nineteenth-century America.40

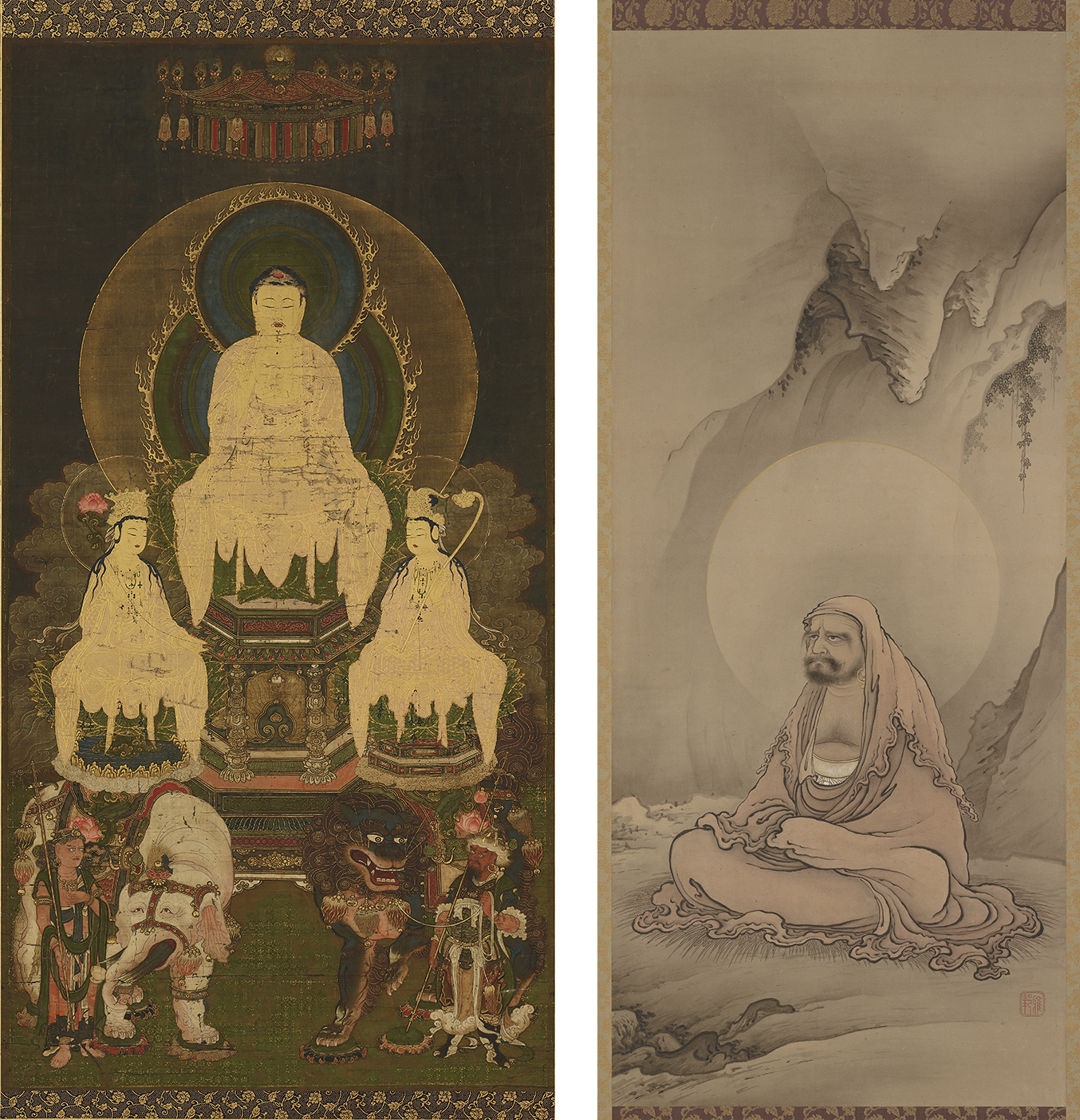

Fenollosa not only provided the intellectual contours for Freer’s collecting but also assisted in the acquisition of objects. In years prior he had helped build the collections of Japanese art at the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) in Boston, and would later guide Freer’s purchases as well (figs. 11a,b). Moreover, the presence of dealers who regularly supplied material from Japan such as Bunkio Matsuki (1867–1940) and exhibitions of Japanese art at venues including the Grolier Club in New York would be crucial in creating an ecosystem that facilitated the kind of collecting practice Freer was developing. The existence of a network of scholars, fellow collectors with similar interests, dealers, and exhibition venues helped cultivate and sustain Freer’s interest and desire for objects from Japan. These features would be key later as well when Freer’s interest in Chinese art would develop more deeply, but also as his interests diversified into West Asia through the presence of dealers such as Dikran Kelekian (1868–1951) and Siegfried Bing (1835–1905), and his acquaintance with early exhibitions of Islamic art in Paris.41

By contrast, had Freer been keen, as the enthusiasm expressed during his travels suggests, to develop or pursue his interest in the arts of India, at that time there were no equivalent networks in place in the United States for the reception or collection of objects from India. Although there had been a substantial presence of Indian objects and Indian businesses at the exposition in Chicago in 1893, de Forest had been the only supplier with a New York address. Moreover, de Forest’s ventures, which cast finely crafted objects from India in Gilded Age interiors, still positioned them within the legacy of industrial design, while Freer was increasingly seeking objects that were sensitive to beauty and aesthetically transcendent—in other words, that lay within the realm of fine art.42 As it was, Freer’s interests in Asian art closely followed the disciplinary shift that saw those objects being transformed from an ethnographic context to that of art history and aesthetics through the work of a new generation of scholars that included Fenollosa. A similar shift would see West Asian art also recast for connoisseurly appreciation, such as the illustrated folios of Persian manuscripts that were being retrieved from the principal purview of bibliophiles or specialists of design and positioned as paintings with genres and motifs, and whose stylistic evolution could be tracked—marking the beginnings of new fields of art historical inquiry. These transitions would be reflected in the growing collections of East Asian and later Islamic art at fine arts museums in the United States, including those in Boston and New York. For the field of Indian art, however, the transformation was only just starting to take place by the first decade of the twentieth century. Scholars in India and England, such as E. B. Havell and particularly Ananda Coomaraswamy, were beginning to argue for the art historical legitimacy and aesthetic value of Indian fine art.43 At the end of the decade, organizations such as the India Society in London would be formed to elevate the appreciation of Indian art as well. For his part Freer regularly bought books on India and Indian culture from various booksellers in England and the United States, and after an introduction by Laurence Binyon of the British Museum, he also became a member of the India Society. Thus, while Freer’s interest in India endured, his furtherance of it through the development of an art collection was more likely limited by a lack of requisite networks to pursue it robustly than by a lack of inclination. Unsurprisingly, therefore, when the time and opportunity presented itself, Freer actively pursued this avenue and materially articulated this interest through the purchase of the Henry Bathurst Hanna collection.

Purchasing the Hanna Collection

By 1904, Freer had decided to bequeath his collection of art to the United States in the form of a museum, the first dedicated to fine arts as part of the Smithsonian Institution. Focusing on American and “Asiatic” schools, Freer explained his collecting ethos to Samuel P. Langley, then the secretary and head of the Smithsonian, in the following terms: “My great desire has been to unite modern work with masterpieces of certain periods of high civilization harmonious in spiritual and physical suggestion, having the power to broaden aesthetic culture and the grace to elevate the human mind.” He went on to say that he would, in consultation with experts, “remove every undesirable article, and add in the future whatever I can of like harmonious standard quality.”44 This latter statement explains in part the accelerated, determined, and focused pace with which he collected thereafter, growing his initial gift of about twenty-five hundred objects to nearly ten thousand works upon his death. Strategic among these was the purchase of the Hanna collection of Indo-Persian painting.

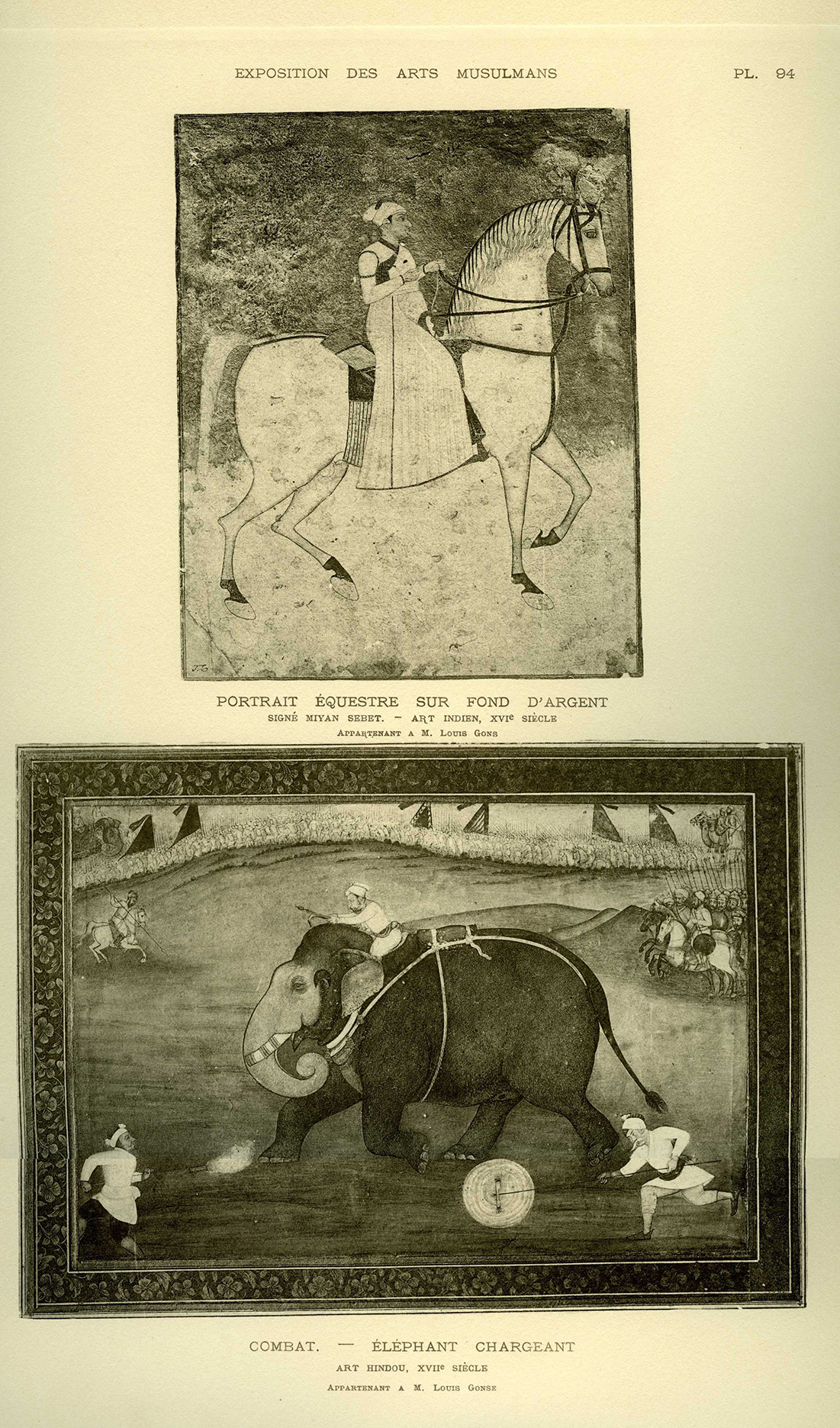

In 1903, Freer excitedly wrote to Hecker from Paris of an exhibition then on view: “To our delight, on arrival here, we found on exhibition in the Louvre, a special collection of Spanish-Moresque, Persian, Arabic and Babylonian art—the great forerunners—loaned from the private collections of Paris—i.e. Baron de Rothschild, Gillot, Vever, Koechlin, et.al. The whole including the first thoroughly good exhibition of these arts ever publicly made. It has offered us a great opportunity to continue our study and compare the various periods, mediums and wares.”45 Although the exhibition in question, the Exposition des art musulman at the Pavillon de Marsan, primarily included metalwork and pottery—with the latter being of special interest to Freer—it also included a few paintings, simply identified as “Indian art,” some of which were reproduced in the accompanying catalogue. Their inclusion indicates the circumscribed way in which art from India at the time was defined and largely skewed collectors toward Mughal paintings, but nevertheless also points to the presence of a few such paintings in private collections, albeit sometimes as related or tangential to a larger corpus of Persian paintings (fig. 12).

Mughal painting, then often termed Indo-Persian, had for its naturalism and decorative qualities been of interest to and acquired by a select group of collectors in Britain and Europe. In the wake of the decline and disintegration of the Mughal Empire on the Indian subcontinent, the great libraries and painting collections that had been compiled by the ruling families were often looted or destroyed. Of the surviving material, much made its way to Britain during the colonial era, accounting for the wealth of sixteenth- to nineteenth-century Mughal-style paintings in British collections. Some works were also made available to European collectors through the work of dealers operating with connections in the Persian and Ottoman empires (these included the likes of Kelekian). While initially collected out of bibliophilic interest in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, focus on the artistic merits of Mughal painting received a fillip in the early twentieth century through the efforts of scholars such as Havell and Smith, who championed the naturalism and aesthetic qualities of such paintings. Nevertheless, among Freer’s milieu of Near Eastern–art aficionados in Paris in 1903, Mughal art was still relegated to a marginal position, Indian in content but derivative from Persian art in sensibility and thus Indo-Persian. While this interstitial position rendered Mughal painting of peripheral interest to most collectors who concentrated on Persian painting, it is conceivable that it was Mughal painting’s very hyphenated status, its perceived interconnected position, that made it especially attractive to Freer at a moment when he was looking for ways to make connections among his diverse collections. Indeed, writing about the Hanna collection a few years later to his friend and fellow collector Charles J. Morse, Freer observed: “I have been anxious for nearly a year to see a collection of Persian-Indo paintings, which are for sale privately. If they are as fine as they are said to be, I shall probably purchase them as I fancy they represent an important link in the chain which connects potteries of Syria, Persia, Babylon, with the later art of China and Japan.”46 Finding such connections between the cultural zones abutting Central Asia was a recurring theme, for the following year Freer shared with Gaston Migeon, the organizer of the Exposition des art musulman in 1903, that he believed the recently excavated “Chinese-Turkestan objects in Berlin … must be of priceless value to all who are interested in Oriental art; they are undoubtedly the great connecting link between the Buddhistick [sic] art of India and all that grew out of it in later periods in the further east.”47

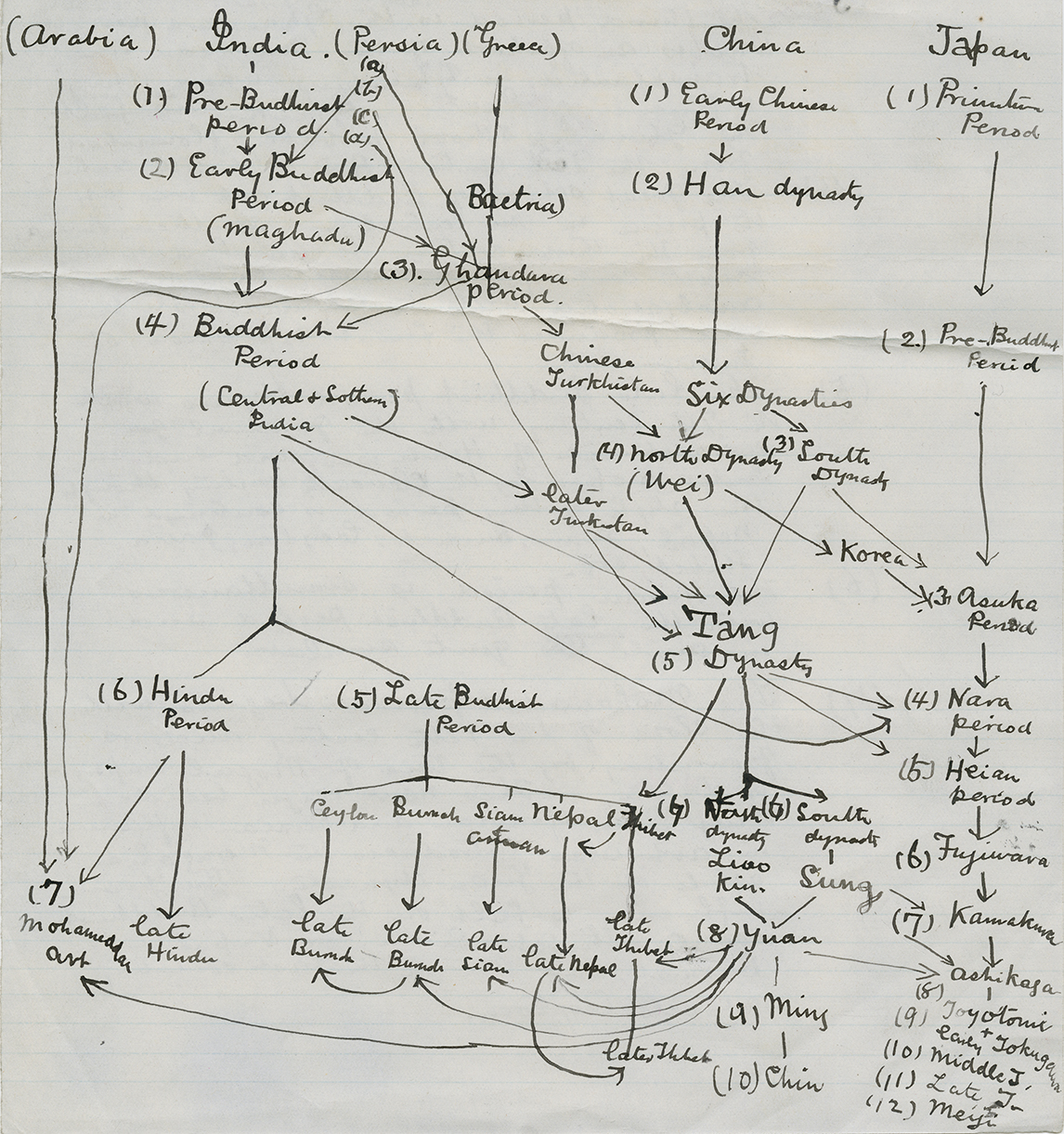

The desire to draw lines that connected the cultures of Asia through art was not unique to Freer. Indeed, some parallels may be seen in the work of Okakura Kakuzo (1863–1913), the Japanese scholar-connoisseur and successor of Fenollosa at the MFA (fig. 13). In a 1908 report assessing the role and future of the Department of Chinese and Japanese art at that museum, Okakura included a diagram as a visual aid to explain the evolution of and connections between the arts of the various cultures in Asia and through time (fig. 14).48 For a department focused on Far Eastern art, Okakura unsurprisingly privileged the principal cultures of India, China, and Japan in a schematic encapsulation of his famous dictum “Asia is One.”49 At the same time, while his notations of “Arabia” and “Persia” were minimal and undifferentiated, he nevertheless connected “Mohammedan art” from India to both in a manner comparable to Freer’s expressed understanding in his letter to Morse. Notably Okakura’s diagram more precisely connected this Indian art (which was understood at the time as largely concomitant with Indo-Persian or Mughal painting) to art from “Yuan”-dynasty China, which Freer did collect, and not the later Ming, which Freer would eschew.50 Similarly akin is the connection that Freer postulates with regard to the connections represented by Chinese-Turkestan objects in his letter to Migeon.

Okakura’s notes that accompanied the diagram also included words that would likely have resonated with Freer’s own ambitions for his museum: “There is a deep significance in the fact that the art of the Extreme Orient should be so well represented in America—the most western of western nations. It makes our Museum a potent factor in the scheme of universal culture, and entitles it to the attention not only of Americans, but also of humanity at large.”51 Considering Freer’s remarks and Okakura’s diagram in tandem further underscores the close manner in which the collector’s interests and understanding—especially with regard to Far Eastern art—and the connections that stemmed from it tracked with those of the MFA, not least because of Fenollosa’s connection to both. The museum’s Japanese art collection was second-to-none outside Japan, but in terms of Chinese art, the museum was competing with others collecting in this area, including Freer. The turn to Chinese art in the opening decade of the twentieth century was expedient, for it was a period of great political turmoil on mainland China, and important objects were entering the international market in unprecedented numbers. One of Okakura’s most significant contributions was his development of the collections of Chinese art at the MFA, and by the time he made his report, the museum had already been greatly enriched by his efforts on trips to China in the years between 1904 and 1908.52 As I have argued elsewhere, following the schema outlined in his diagram, art from India would be key in realizing through a collection Okakura’s imagining of an aesthetically and spiritually interconnected Asia; and very likely, having propelled the museum’s expansion through the collection of Chinese art, Okakura would have turned to collecting Indian art as well.53 In 1907 it was Freer, however, who took an early step in the direction of including art from India within his larger and growing collection of Asian art.

During his travels to Ceylon in January 1907, Freer was informed of the Hanna collection’s availability from an unexpected source, Dr. Frances Elizabeth Hoggan (1843–1927) (fig. 15). Hoggan was a Welsh physician—the first woman to receive a doctorate in medicine from a European university—and a social reformer. In 1906 she was touring the United States giving lectures and while in Chicago had learned about Freer in an article on his gift to the nation published in the Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine.54 Over a short correspondence with Freer, she shared her acquaintance with a collection of Indo-Persian paintings that were then available privately on the market in England, and she subsequently arranged for Freer to receive a catalogue and a few photographs of the works (fig. 16). It was based on these materials that Freer determined to travel to England later that year to meet Hanna and see his collection in person.

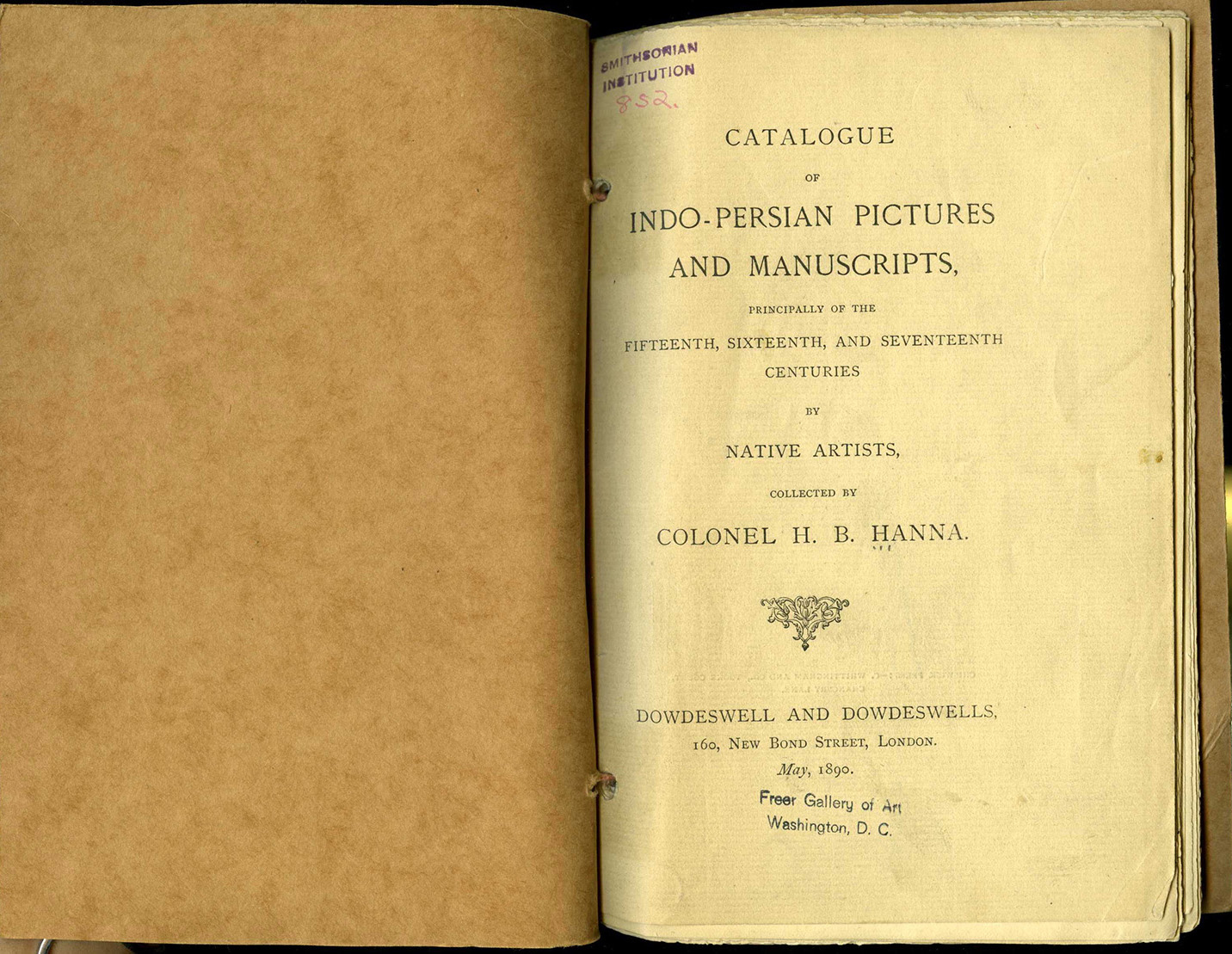

Colonel Henry Bathhurst Hanna (1839–1914), a retired British officer, had served in India for three decades, from the time of the Revolt of 1857—then called the Indian Mutiny—and had amassed the collection in question.55 In his catalogue of the collection, he described having gradually acquired the painted folios and illustrated manuscripts over a thirty-year period, mostly in places outside the large cities, in a manner echoing Freer’s own experience of preferring purchases in smaller bazaars during his time on the subcontinent. Hanna delighted in having had what he described as “the pick of the market”56 but blithely acknowledged that many of the works then in his collection had undoubtedly become available in the chaotic aftermath of conflict, especially the Mutiny: “Many of my pictures must have belonged to the Royal Library at Delhi, and were sold by the English authorities, or carried off by the mutineers after the Siege. Others again may have been stolen from the Palace at Agra when the Jats plundered that city in the eighteenth century.”57 In so doing he drew a distinction between what he would have understood to be official pillage or the permissible expropriation of property by the English and that which was simply purloined by native populations (whether the Jats or the mutineers).58 In any event, whether Hanna understood the works to have been licit loot or the spoils of war, he did not question the circumstances that led to their availability to him or the legitimacy of his purchase—the matter of provenance was of interest to him only insofar as it bolstered the prestige of the works in his collection.59 Hanna made this collection available for sale when in May 1890 he exhibited it at Dowdeswell and Dowedswell’s, a London gallery specializing in prints. When he did not find a buyer, he sent the paintings on long-term loan to Laing Art Gallery at Newcastle-on-Tyne, and it was there that Freer saw the collection when he visited England in September 1907.60

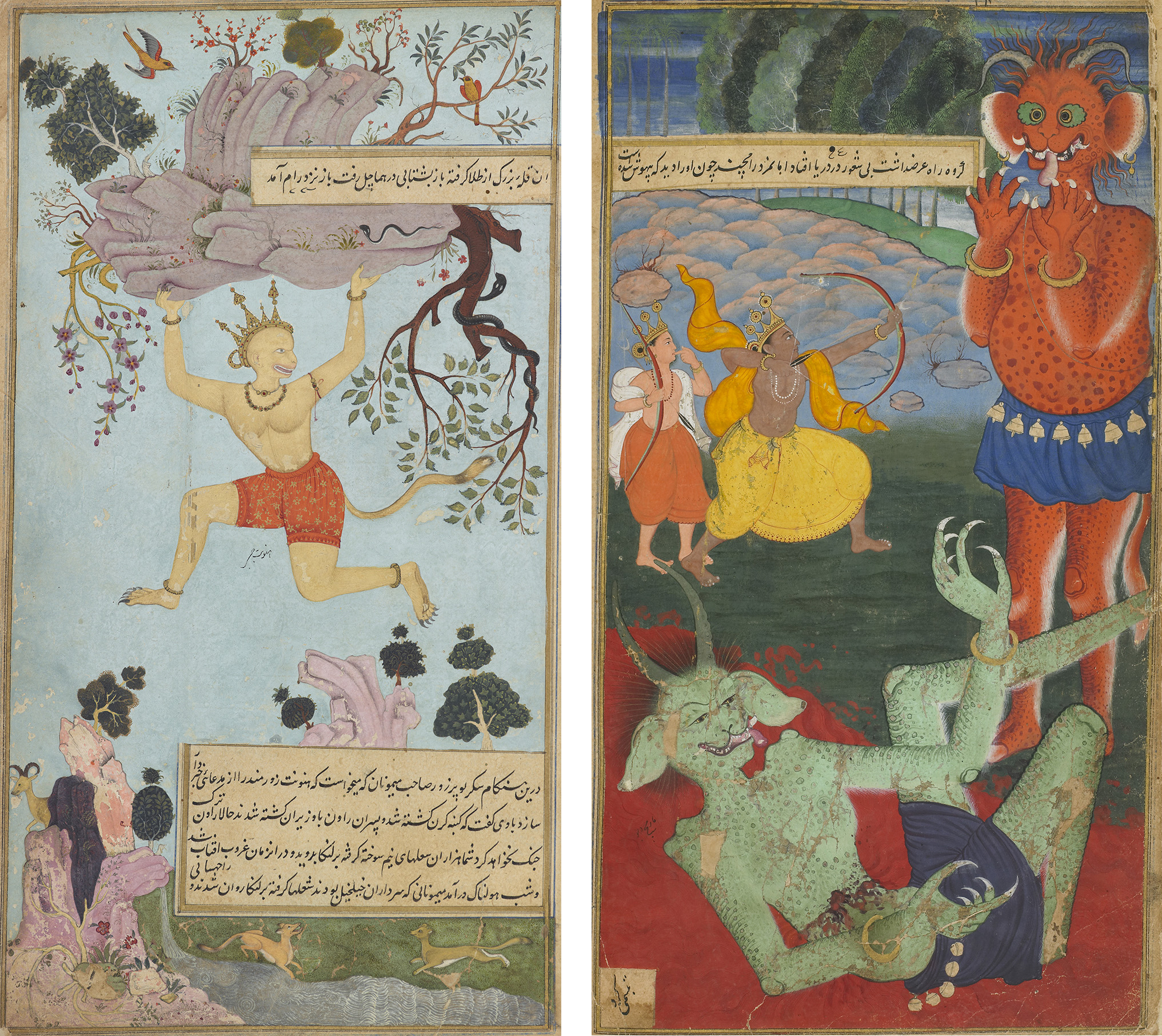

Freer spent a whole day examining the collection, which consisted of 129 paintings and thirteen manuscripts, and made brief notes about their quality and his estimation of their value. His notes and correspondence surrounding the purchase do not suggest that the original sources and channels from whence the individual paintings came to the Hanna collection were of particular interest or concern to Freer. Hanna was seeking to sell the collection in its entirety, in order to provide for some relatives, and had reduced his asking price from £10,000 to £7,500.61 According to the catalogue of the collection, authored by Hanna himself, most of the works were described as imperial Mughal albeit from differing periods (many of these ascriptions would be revised to later dates in subsequent years). Prized above all was an illustrated version of the Hindu epic the Ramayana then attributed to the atelier of the emperor Akbar (figs. 17a,b). While the patronage of this manuscript has since been emended, it remains the jewel of the Hanna collection, and a third of the eventual price Freer paid for the whole collection was for this one work.

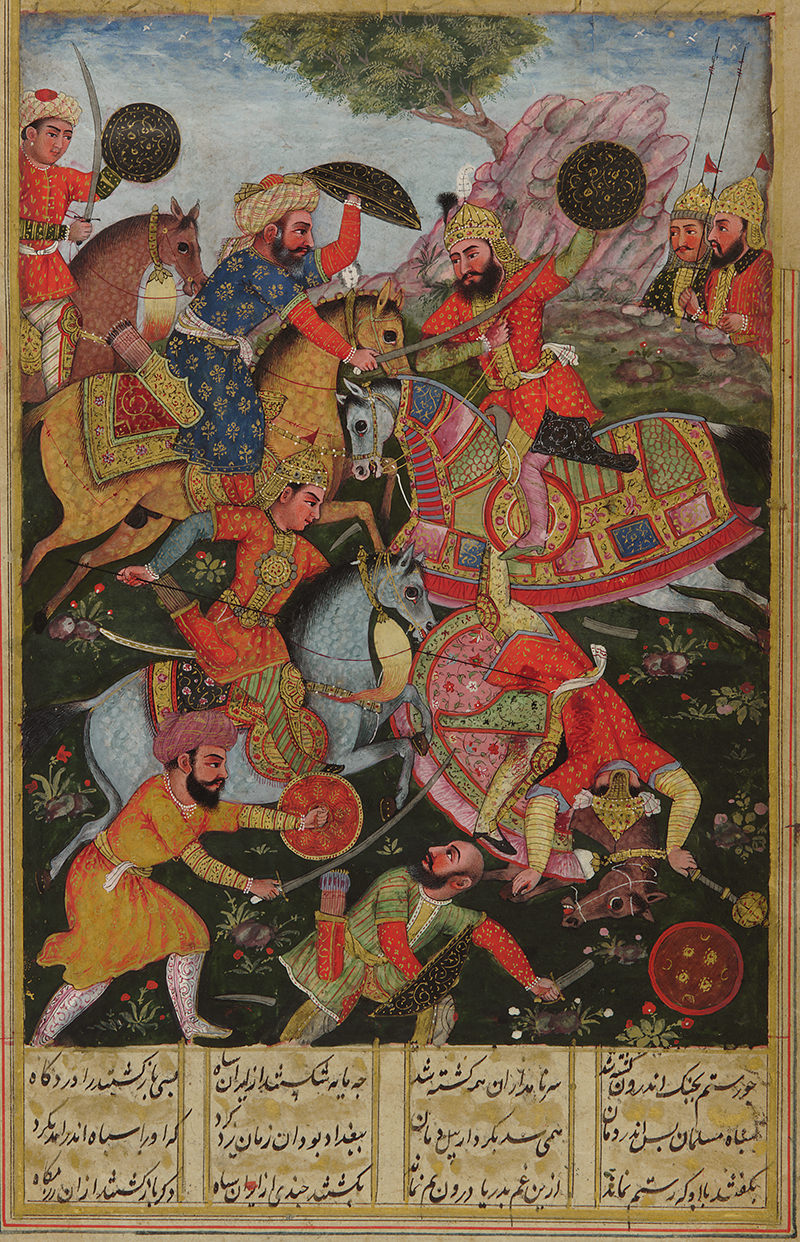

The Hanna collection itself was eclectic, with paintings ranging from portraits of Indian rulers and Indian ethnographic types to classic compositions of genre scenes, to architectural views of important Islamic buildings. The manuscripts included an album and three copies of the Shahnama and a Gulistan, types of works typical and likely familiar to Freer (figs. 18, 19). In his notes Freer recorded for his own reference those he preferred as “good,” “fine,” or “superb,” and ascribed values for works between $25 and $250. Aside from the Ramayana, there was only one painting next to which he noted $300, a singularly greater value than the others—a painting described in the catalogue as a portrait of the emperor Aurangzeb (fig. 20). The disjunction evident to contemporary eyes is explained in part by the fact that at the time Hanna had erroneously (unwittingly or otherwise) described his collection in quite specific terms, tethering subjects in several paintings to known individuals or events, often relating to imperial Mughal history and thus giving greater credence to their historicity.62 In this light, coupled with the fact that Hanna was not a dealer routinely trading in such material and thus less likely to knowingly mislead on matters of attribution for the purposes of a sale, Freer’s decision to value more greatly those paintings with ascribed imperial Mughal associations may be more understandable. However, before committing to purchase the collection, Freer sought further guidance from his friends in Paris, including Gaston Migeon and Raymond Koechlin, prior to eventually offering to purchase the collection for £3,100 (at the time equal to approximately $15,000). Hanna was disappointed but agreed to the sale in October 1907.63

Having expressly traveled across the Atlantic in pursuit of the Hanna collection, and perhaps enthused by his latest acquisition, Freer indulged in a few further Persian and Indo-Persian painting purchases on the same trip, from Luzac & Co. and Bernard Quaritch in London and from M. Bing in Paris (figs. 21, 22). Observing this brief burst of interest and possibly discerning a new avenue of collecting in his patron, Dikran Kelekian also offered Freer some Persian paintings at his establishment in Paris, but in this instance Freer declined to make further purchases. Upon receiving a letter from Kelekian complaining about this perceived slight, Freer’s mollifying response may also explain his temerity in not pursuing much further this area of collecting: “This [Hanna] collection, along with a few other specimens which I already owned, some of which came from your store, will receive during the coming winter much of my time. I shall study them carefully and hope to familiarize myself with this charming art, and by degrees in the future when opportunity offers, I hope to add to the collection, but I feel it would be very unwise on my part to rush into the market and buy promiscuously without knowing more about the subject and it was for this reason and for none other that I declined to buy the specimens shown me in your shop in Paris.”64

In spite of Kelekian’s best efforts, and his bemoaning the state of the market for Persian paintings in America, Freer’s foray into the realm of Persian and Indo-Persian paintings was largely confined to the period 1907–1908. Some years later, in 1914, in a letter to Kelekian discussing the recent purchase of the Goloubew collection of Persian paintings by the MFA, Freer gave partial explanation for his own pivot away: “It seems more important to secure fine specimens of Chinese Art than it does to secure specimens of Persian Arts. Many other collectors and museums are quite likely to buy Persian things before they are likely to invest heavily in Chinese objects, and I feel it wiser for me to watch for things Chinese before too many buyers enter the market and send the prices beyond my reach. . . . The Goloubew collection of Persian miniatures was offered to me privately some time ago but I declined to consider the purchase of the collection for the reasons above mentioned.”65 Ever the pragmatist, Kelekian did not hesitate to offer Freer Chinese works instead! The response also indicates that Freer continued to keep an eye on the trajectory of growth of the collections at the MFA and sought a competitive advantage as he focused his energies and resources on objects from China. At the same time, he maintained cordial relations with Denman W. Ross (1853–1935), a trustee of the museum and its principal patron for Asian art, discussing their mutual interests in India and Chinese art.66 The overlapping and intersecting ambitions of the Freer and MFA collections would continue in the years ahead. Indeed, it was Ross who bought for the MFA in 1917 the next significant collection of Indian paintings that came on the market—a collection offered by Ananda Coomaraswamy—but would do so only after it had been declined by Freer.

The Coomaraswamy Coda

Although the purchase of the Hanna collection established a new area in Freer’s collection in 1907, it did not yet usher in an era of active growth. Nonetheless, Freer would have felt vindicated in his decision to pursue it and include it among the collections being prepared for his eponymous gallery, especially upon reading Vincent Arthur Smith’s account of the Hanna collection in an article from the Indian Antiquary of June 1910. In it Smith described the group of paintings (known to him only through the catalogue and some reproductions) in laudatory terms: “Colonel H. B. Hanna made it his business to collect the best specimens of the skill of the Indo-Persian artists, and thus succeeded in bringing together a wonderful collection, probably the best in the world.”67 He also favorably noted its comparison with the collections of the British Museum, the South Kensington Museum, and the India Office Library. The highlighting of pieces in the collection was occasioned by its sale to “the great Art Gallery which is being built at Washington,” and the article ruefully concluded that “the only consolation is that it will be carefully preserved in its new home, and probably more appreciated than if it had remained in London or Calcutta.”68

Freer also kept himself informed on new scholarship on Indian art and added books by Havell and Smith and publications from the India Society to his library, even as his collecting interests were focused on Chinese art at this time. Indeed, it was via his books that Ananda Coomaraswamy (1877–1947; fig. 23), who had published The Arts and Crafts of India and Ceylon in 1913, presumed Freer might be acquainted with him and his work when he wrote to the collector in 1915, requesting permission to reproduce “your beautiful Sung Kwanyin” in his forthcoming book, Buddha and the Gospel of Buddhism (1916).69 Freer obliged the request to illustrate the work, which is now understood to be from the later Qing period. The following year Coomaraswamy traveled to the United States for the first time, accompanying his English wife Alice Richardson, a singer who went by the stage name Ratan Devi, on a series of concerts. It was during this tour that Freer’s diaries indicate he and Coomaraswamy met in New York, first at the Plaza Hotel on March 10, 1916, and subsequently on at least three other occasions in the company of the American sculptor Paul Manship and his wife. Freer also took in a performance by Mrs. Coomaraswamy. Although what transpired between the men during these interactions remains unknown, one can speculate that perhaps their conversation rekindled Freer’s dormant interest in his own nascent collection of paintings from India, for later that summer, while in the Berkshires at Great Barrington in Massachusetts, he noted in his diaries that he spent the greater part of some days examining “Mogul paintings and books.” Coomaraswamy for his part gave lectures and, at the same time, kept a lookout for opportunities to sell his collection and secure an income from it.

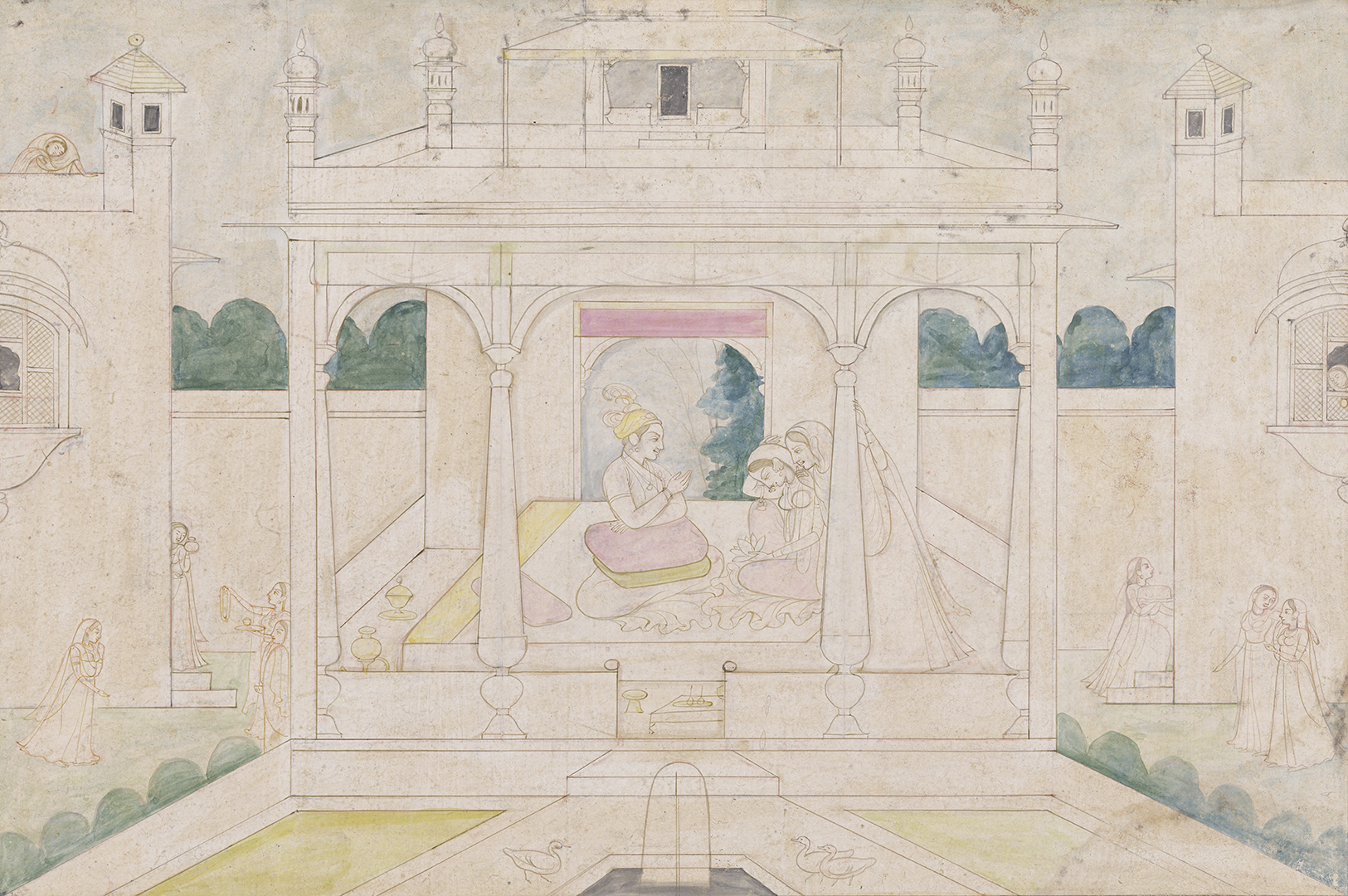

Coomaraswamy’s personal collection, primarily of paintings and drawings, had been assembled during his travels to India in the preceding decade and crucially formed the material for his thesis proposing the field of Rajput painting. In Coomaraswamy’s early publications in this area, of the forty-one items reproduced in Indian Drawings (1910), thirteen belonged to the author, and of the thirty-seven items that he published in Indian Drawings: Second Series, Chiefly Rajput (1912), all but one belonged to him. Finally, of the 105 items that Coomaraswamy published in his magnum opus Rajput Paintings (1916), 81 belonged to the author (fig. 24).70

It was about this collection that Coomaraswamy wrote to Freer in July 1916, marshaling arguments similar to those made by Okakura in his 1908 report for its inclusion in an American museum: “It has always been my earnest wish that this collection, which is in many ways unique, should be preserved intact and either during my lifetime or subsequently be permanently housed in a suitable museum. I had at one time wished that this should have been in India but I am now inclined to think that many human advantages are better gained by the dissemination than by the local concentration of works of art. Your great Chinese collections for example will have at this stage of the world’s history, more effect in their home at Washington, than if they had remained in the East. Their dynamic effect is greater here where they present the strongest contrasts. From this point of view, in the same way, it would not distress me to see my own collection properly housed in an American Museum.”71 Confessing to the financial exigencies brought on by the ongoing effects of World War I that necessitated the sale, Coomaraswamy continued by pressing his case for the purchase of his collection, noting the ease with which it could be melded with Freer’s and complement the scope of the museum he was building, but also importantly, and in a manner that was of particular interest to Coomaraswamy, extend the ambit of Indian art beyond that of simply Mughal painting: “It would not, indeed, be difficult to transform this into a Museum of Asiatic Art, rather than of purely Far Eastern art: but in any case, and apart from this, it seems to me that it would be very possible to add to it an Indian room or rooms where the bronzes and later schools of painting, Rajput and Mughal, together with the choicer types of decorative art, might be for the first time in America, or indeed the world, adequately represented.”72 Finally, he appealed to Freer’s well-known business acumen in setting the proposed value: “The price that I should ask would be $55,000 (fifty-five thousand) for the collection delivered in America. I have no doubt that in years to come it will be valued more highly than this; on the other hand Indian art has not at present the commercial vogue which attaches to some others, and I think this might be regarded as a good opportunity for the nation, through your far-sighted activity to take the pioneer step in this direction.”73

Notwithstanding the strategic framing and flattery of Coomaraswamy’s proposal, Freer while appreciative was obliged to decline it in a letter later that month citing his ill health and insufficient capacity to “investigate the matter as fully as it deserves.”74 In the same letter he acknowledged having read Coomaraswamy’s Rajput Painting, which he shared had given him “many hours of pleasure.” The map of Rajputana included in Coomaraswamy’s volume noted many of the places Freer had himself traveled to in 1895 and would have surely brought back fond memories (fig. 25). He went on add: “Since my purchase of the Hanna collection of so-called Indo-Persian miniatures, I have had but little opportunity to examine the same, or to familiarize myself with Indian Art, and some time ago when it was determined that I should spend this summer at Great Barrington, I had the Hanna collection brought here, and I have had some little opportunity to compare my pictures with those illustrated in your book, but last week the work was stopped by my physician.”75 Although Freer’s letter indicates that his return to the Hanna collection was short-lived, and his capacity to develop his Indian collections was curtailed by his declining constitution, there is indication that the encounter with Coomaraswamy had some impact. The typed inventory lists of works destined for the Smithsonian bear Freer’s additional notes based on Rajput Painting, which is referenced, quoted, or in other instances indicated by the short marginal notation “Rajput?” alongside the descriptions of the works, further evidencing that Freer had indeed closely compared the compositions of paintings from the Hanna collection with those illustrated in Coomaraswamy’s volume.76 This brief but sincere engagement with Coomaraswamy and his scholarship suggests once more that while Freer remained interested in and open to developing his understanding of Indian art, in this instance it was the limitations of his personal circumstances that stymied his progress and further collecting. The following year, Coomaraswamy sold part of his collection to Denman Ross for the MFA and became the first keeper of Indian art at the museum.77

Conclusion

By focusing on the circumstances surrounding Freer’s purchase of the Hanna collection, this article has suggested that its uniqueness notwithstanding, rather than being an incidental or even tangential acquisition, it was a decision that was purposeful and embedded within deeper personal experiences and broader cultural trends. Freer’s belated arrival at collecting Indian art is attributable in part to the unevenness of access—East Asian and even Near Eastern objects would find their ways to American collectors and museums far earlier than those from South or Southeast Asia on account of the specialization of networks of dealers and markets—but also because as Freer developed his connoisseurly eye he sought out objects of art rather than what he considered merely curios, the type of things he had purchased as a tourist in India and would largely dispense with in his lifetime. Therefore, when presented with the opportunity to add a preassembled group of paintings of a kind he had some familiarity with and found to be of strategic connective interest within his larger collections, he sought to acquire it without reservation. In hindsight the eclectic subjects of the works across a limited range of painting styles undoubtedly present a circumscribed framing of Indian art. But understood in the context of his developing schema, with this one move Freer delineated an initial place for art from India, a place that he may well have wished to develop further in time. Unlike the collectors and museum makers of the nineteenth century, Freer’s aim at the outset was the aesthetic framing of works, and as such he was deeply influential in the larger appreciation of non-Western art in this manner, not only through the establishment of his own museum but also through connections with contemporaries at other museums. This was indisputably the case for Japanese and Chinese art, in which he was guided by Fenollosa. And as the interactions between Coomaraswamy and Freer suggest, it is conceivable that had their paths crossed at a more opportune moment, Coomaraswamy might have played a role for Indian art in Freer’s collecting similar to Fenollosa’s. Instead, in his capacity as a keeper at the MFA, Boston, Coomaraswamy became a colleague of John Ellerton Lodge (1876–1942), a scholar of Chinese art, Okakura’s successor, and Freer’s choice to head his gallery. Coomaraswamy and Lodge maintained a rapport, and tellingly it was during the early years of Lodge’s leadership that the first pieces of Indian art added to the Freer Gallery of Art were acquired from Coomaraswamy, serving to more robustly establish a place in the museum for the study, appreciation, and collection of such works (figs. 26, 27).78 It was thus in Freer’s legacy of a museum that Indian art proved to be that enduring presence he suspected it would be from his very first encounter, and for which his acquisition of the Hanna collection served as a singular prelude.

Acknowledgments

This article is dedicated to Kavita Singh (1964–2023), scholar, mentor, and friend. I would like to thank the editors of Ars Orientalis and the anonymous peer reviewers of this essay. I am grateful for the Smithsonian Institution Predoctoral Fellowship that allowed me to conduct the primary archival research for this essay as well as the guidance of Debra Diamond, Lee Glazer, Nancy Micklewright, and David Hogge during the fellowship.

Author Biography

Brinda Kumar, PhD (Cornell University), 2014, is an Associate Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, where her curatorial projects have included monographic exhibitions on the work of Nasreen Mohamedi, Gerhard Richter, and Charles Ray as well as thematic exhibitions including Like Life: Sculpture, Color, and the Body (2018) and Home Is a Foreign Place: Recent Acquisitions in Context (2019–20). She is part of the curatorial team working toward the Oscar L. Tang and H. M. Agnes Hsu-Tang Wing at the Met. Kumar is the author of several essays for museum catalogues and has published articles from her doctoral research on the history of collecting Indian art in the United States. E-mail: brinda.kumar@metmuseum.org

Notes

- For further discussion of this history, see Susan Bean, Yankee India: American Commercial and Cultural Encounters with India in the Age of Sail, 1784–1860 (Salem, MA: Peabody Essex Museum, 2001), 13. ⮭

- “Because curiosities were actually from far-off places, unlike recollections or journal descriptions that were merely about those places, they embodied real connection to their places of origin. . . . People who had never been to India had to connect exotic things they saw to what they already knew, believed, or imagined about the world’s creatures, civilizations, or arts.” Bean, 13. ⮭

- “Entering, we find ourselves in what appears to be a Bazaar. To the left, a number of gorgeous rugs, some hanging from the wall and others piled in heaps upon the floor, reveal the industrial skill of the natives of Hindostan. To the right, a series of small rooms are devoted to the sale of fragrant tea, the pungent odor of which pervades that part of the building. Passing these rooms, we enter an oblong hall surrounded by galleries, and covered with a plate-glass skylight through which the sun shines down with an almost Indian radiance. . . . So great is the amount of hard sandal-wood, such as tables, panels and even gates, that the heavy odor drifts searchingly through the great hall and adds to the general oriental flavor.” James W. Shepp and Daniel B. Shepp, Shepp’s World’s Fair Photographed (Chicago: Globe Bible Pub., 1893), 470. ⮭

- “Many ancient monuments, street, bazaar and house scenes, durbars, burial processions and grounds, temples, wedding and betrothal ceremonies, religious worship and customs. . . . There are also models of artisans with their tools and appliances; of the means of transport by land, river and sea, and of the different tribes and castes of India. This class of exhibits is composed of several thousands of most artistic figures dressed in the costumes worn by the people.” Moses P. Handy, The Official Directory of the World’s Columbian Exposition: May 1st to October 30th 1893; a Reference Book of Exhibitors and Exhibits (Chicago: W. B. Conkey, 1893), 129. ⮭

- Peter H. Hoffenberg, An Empire on Display: English, Indian, and Australian Exhibitions from the Crystal Palace to the Great War (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), 146. The celebrated Indian painter Raja Ravi Varma (1848–1906), who submitted a series of ten portraits to the fair titled The Lives of Native Peoples as a counter to colonial narratives, nevertheless found himself contending with this ethnographic bind on an international platform. Saloni Mathur, India by Design: Colonial History and Cultural Display (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), 105–6. ⮭

- Ingrid Larsen nuances the oft-repeated assertion that the origin of Freer’s interest in Japanese prints is solely traceable to his encounter with Whistler, noting Freer’s early familiarity with and interest in such objects, notably through a Japanese print exhibition at New York’s Grolier Club in 1889. Ingrid Larsen, “‘Don’t Sent Ming or Later Pictures’: Charles Lang Freer and the First Major Collection of Chinese Painting in an American Museum,” Ars Orientalis 40 (2011): 10. ⮭

- John MacFarlane, Bookseller and Stationer, voucher, June 1, 1894, Charles Lang Freer Papers, box 125, folder 1-8, National Museum of Asian Art Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, Gift of the estate of Charles Lang Freer, FSA.A.01 (cited hereafter as Freer Papers). ⮭

- Edith Wharton, The Age of Innocence (London: D. Appleton; New York: Scribner’s, 1920), 340. ⮭

- Financial materials - Vouchers - General vouchers, 1894, Freer Papers. ⮭

- For an analysis of Weeks’s role as an expatriate American painter who “shaped a form of European Orientalism based on the textures of British India while also mirroring, perhaps coincidentally, the taste for exoticism in the American Gilded Age,“ see Romita Ray, “‘A Dazzle of Light’: Edwin Lord Weeks and Royal India,” in India in the American Imaginary, 1770s–1880s, ed. Rajender Kaur and Anupama Arora (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), 247–81. ⮭

- These included The Last Voyage—A Souvenir of the Ganges (set in Benaras), Study at Bombay, and Marble Court at Agra, all depicting places that Freer himself would visit in 1895. Moses P. Handy and Halsey Cooley Ives, World’s Columbian Exposition, 1893: Official Catalogue; Part X, Department K: Fine Arts (Chicago: W. B. Conkey, 1893), 29. ⮭

- For more on Isabella Stewart Gardner’s travels to Asia, including India, see Alan Chong and Noriko Murai, Journeys East: Isabella Stewart Gardner and Asia (Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 2009). ⮭

- Charles Lang Freer to Frederick Stuart Church, August 15, 1894. All of Freer’s correspondence and diary entries cited in this article are with the Freer Papers in the National Museum of Asian Art Archives. Their original orthography and punctuation have been retained. ⮭

- It is likely that Freer referenced the 1892 edition of the popular Handbook for Travellers in India and Ceylon published by John Murray in London. The travel guide had been published since 1859 and went through several editions into the early twentieth century. We also know that Freer engaged a servant (correspondence with a “Dorasawmy Butler” in Madras reveals that he had been engaged by Freer during his entire journey, and Freer recommended him to Hecker during the latter’s travels to India) and guides during his journey, noting in his correspondence with Hecker the presence of a certain S. Daniel who took him to see temples in the vicinity of Madras (now Chennai): “The present is the great festival time of Southern India and I am up to my neck in the fun. . . . Trichinopoli is very gay today with its crowds of gaily dressed natives (have seen only four whites) good natured, good looking, following the religious practices of thousands of years. Singing, marching, dancing, exchanging visits, giving flowers, bathing in the Kaveri River and in sacred tanks, crowding to the temples, carrying great bejewelled idols and doing as they please without government interference. It is all strangely picturesque and extremely fascinating. . . . In the thickest of the crowd this morning my progress not at all unpleasant to me, seemed not to please one of the high priests who sent a splendid big elephant with a crowd of servants to walk beside me so that I should have plenty of room. My guide however, who hates the Hindus said the high priest didn’t care a rap for me but did not want the clothing of his chosen ones defiled by coming too near me— either way—it was great fun.” Charles Lang Freer to Frank J. Hecker, January 6, 1895. Daniel also arranged for Freer to see a nautch performance at Chidambaram, which struck him as unusual enough to note down specifically in his diary and to write back to Daniel on his return to Detroit, thanking him “for remembering my request to give me the name of the interesting dancing girl at Chidambaram. I recall with pleasure her graceful movements and sweet disposition.” Charles Lang Freer, Diary entry, September 17, 1895, Freer Papers. ⮭

- “This going from wonder to wonder and then wondering if wonders ever end. This mixture of stately beauty and simple happy lives of great wealth and extreme poverty, out of which both high and low seem to extract so much contentment and so little care. The responsibilities of life as we call them, are adjusted here upon much simpler and I fancy happier basis. Of course my opinions are based upon very slight evidence and may be entirely wrong, but one can easily see that the masses here although much poorer are immensely happier than in our country. One logical reason therefore is because their necessities are so very much less. . . . It’s tremendously interesting to study the simplicity of their food, clothing and customs—and the complexity of their castes and religious practices.” Freer to Hecker, Bombay, January 27, 1895. ⮭

- Freer to Hecker, February 4, 1895. ⮭

- “The marvelously picturesque capital of the state of Meywar, the residence of the Maha Rana and of a political agent, to whom a suitable introduction should be brought. It is difficult to conceive anything more beautiful than the situation of this place.” A Handbook for Travellers in India and Ceylon: Including the Provinces of Bengal, Bombay, and Madras, the Punjab, North-West Provinces, Rajputana, Central Provinces, Mysore, etc., the Native States, Assam and Cashmere (London: Murray, 1892), 85. ⮭

- Freer to Hecker, February 5, 1895. ⮭

- Mehta also likely met Edwin Lord Weeks on his visit to the state, as an illustration of him in court dress is included in Weeks’s book From the Black Sea through Persia and India (1896). ⮭

- Freer to Hecker, February 18, 1895. ⮭

- “My dear friend, Some weeks ago I received the package of photographs which you so kindly sent. . . .The photographs are many beautiful works. I am delighted to have them.” Charles Lang Freer to Fateh Lal Mehta, February 18, 1896. The set of albumen prints from Mohan Lal studios were originally thought to have been bought by Freer himself while in India, but the letter from Freer to Mehta as well as the presence of labeled inscriptions in Mehta’s handwriting confirm that these prints were sent to Freer by Mehta in 1896. In letters between the men, Freer addressed Mehta’s inquiries about the price and availability of bicycles, magic lanterns, and harmoniums, and promised to send him copies of Omar Khayyam and Longfellow. ⮭

- Freer to Hecker, February 18, 1895. ⮭

- “Besides other state rooms, the palace contains a valuable Library, kept in excellent order, and rich in Oriental manuscripts. The chief ornament of the collection is a matchless ‘Gulistan,’ which cost about £10,000 to produce; it is beautifully illustrated with miniature paintings… The Rajah’s Stables are worth a visit. There are 200 horses, some of them very fine.” Handbook for Travellers in India and Ceylon, 128. ⮭

- Vincent A. Smith, A History of Fine Art in India and Ceylon: From the Earliest Times to the Present Day (Oxford: Clarendon, 1911), 342. ⮭

- Freer to Hecker, March 9, 1895. Elsewhere he had noted: “Oriental art and architecture is ‘crawling through my innards’ so to speak, and whether it will prove a tonic or a tape worm, is still an enigma. I can certainly hope for no certain result until after digestion and that means many months.” Freer to Hecker, February 23, 1895. ⮭

- For more on de Forest, see Roberta A. Mayer, Lockwood De Forest: Furnishing the Gilded Age with a Passion for India (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2008). ⮭

- “At Ahmedabad I found the most beautiful wood carving I have ever seen and was treated with great consideration by a charming old Jain family.” Freer to Hecker, February 5, 1895. ⮭

- Tina Young Choi, “Producing the Past: The Native Arts, Mass Tourism, and Souvenirs in Victorian India,” Lit: Literature, Interpretation, Theory 27.1 (2016): 55. ⮭

- While the photographs are now in the Archives of the National Museum of Asian Art, many of the souvenirs collected by Freer, including several shawls and textiles, were given away as gifts during and after his lifetime. Miscellaneous lists of textiles, for instance, have the notation “KNR” next to entries for several shawls from India, indicating that these were given to Katherine Nash Rhoades. Two possible exceptions are F1909.408 and F1909.409. ⮭

- ”When you visit India waste no time at Calcutta, Madras, Bombay or Delhi—and still, it is these very towns that tourists from America and Europe fill themselves with things not Indian and then ever thereafter d[am]n India. They might as well judge Italy by visiting the Italian quarter in New York.” Freer to Hecker, March 15, 1895. ⮭

- Freer to Hecker, February 23, 1895. ⮭

- These were originally thought to have been bought by Freer in Egypt in 1907. However, letters from Shah and a voucher dated April 19, 1897, confirm that Freer bought these from the Lahore-based dealer. The items correspond to accessioned objects F1907.486 through F1907.501 in the Freer Gallery. ⮭

- These are the Nala-Damayanti drawings corresponding to F1923.10 through F.1923.13 in the Freer Gallery. ⮭

- Freer to Hecker April 20, 1895. ⮭

- Freer to Hecker, April 20, 1895. ⮭

- Freer to Hecker, February 18, 1895. ⮭

- Freer to Hecker, May 7, 1895. ⮭

- “In the Orient one’s mind frequently and easily turns many corners of the endless road to the great unknown. To the stranger in India that Faith which drove Buddhism from its very birth place to China, Korea and finally Japan seems the representation of Archaic Truth.” Freer to Hecker, June 26, 1895. ⮭

- Kathleen Pyne, “Portrait of a Collector as an Agnostic: Charles Lang Freer and Connoisseurship,” Art Bulletin 78.1 (March 1996): 80–81. ⮭

- “Fenollosa’s evolutionary philosophy of aesthetics cast Whistler’s art in the religious terms of late nineteenth-century agnosticism, an understanding which accorded well with Freer’s own use of art. Fenollosa’s scholarship thus provided a forceful direction in Freer’s quest after 1900 to create an art collection that from ancient to modern times chronicled the presence of spirit in the material form of the eternal perfected object. . . . In 1907 Freer himself was eventually led by Fenollosa’s theories to attempt to trace these aesthetic principles back to their supposed source in Egyptian art and pottery. In the years before he died, Freer devoted nearly all his economic and physical resources to demonstrating the existence of such universal aesthetics and constructing a correlative sequential development in his collection with representative pieces from the Near East and the Far East.” Pyne, 93. ⮭

- The collectors of West Asian art had hitherto been primarily in Europe, but with Kelekian’s efforts, the market was being extended westward to the United States as well. Nevertheless, Islamic art was still best accessed in Europe, where the major exhibitions such as the Exposition d’art Musulman at the Palais de l’Industrie (1893) and Exposition des art musulman at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs (1903) took place in Paris. Freer would have catalogues for both exhibitions in his library and also saw the latter in person. ⮭

- “Sensitivity to beauty, which might be achieved through an educated appreciation of art, was considered by certain collectors, including Freer, the antidote to the materialism of the Gilded Age.” Thomas Lawton and Linda Merrill, “Acquired Taste,” in Freer: A Legacy of Art, ed. Lawton and Merrill (Washington, DC: Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution; New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1993), 19. ⮭

- Both Havell’s and Coomaraswamy’s books would have been found in Freer’s library. ⮭

- Charles Lang Freer to Samuel P. Langley, December 27, 1904. As part of this weeding-out process, he also dispatched to Professor Edward S. Morse, then director at the Peabody Museum in Salem, a number of items including an “Indian water jar, silver anklets and a lot of eight engraved charms [that] were bought during my first trip to India.” Charles Lang Freer to Edward S. Morse, October 26, 1908. ⮭

- Freer to Hecker, June 22, 1903. ⮭

- Charles Lang Freer to Charles J. Morse, August 30, 1907. ⮭

- Charles Lang Freer to Gaston Migeon, October 26, 1908. ⮭

- Okakura Kakuzo, Adviser to the Department, Department of Chinese and Japanese Art, to the Committee of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, May 9, 1908, p. 8, Art of Asia departmental files, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. ⮭

- Shortly before coming to the MFA, Okakura had authored Ideals of the East (1903), published after a year spent studying art in India, where he came into contact with Bengali intellectuals including members of the Tagore family. Okakura had famously opened his book with the bold statement that “Asia is One,” but it was not until he was in Boston that his ideas about Asian culture could be worked out beyond the page. ⮭

- “Do not send me any Ming or later pictures,” Charles Lang Freer to K. T. Wong, February 28, 1919. ⮭

- Kakuzo to the Committee of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, May 9, 1908, p. 8. ⮭

- For more on the history of the department’s collections at the MFA, see Jan Fontein, “Notes on the History of the Collections,” Asiatic Art in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1982), 6–15. ⮭

- Brinda Kumar, “Okakura’s Diagram for Asiatic Art,” Mapping Asia (2014): 64–75. ⮭

- Leila Mechlin, “The Freer Collection of Art,” Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine 73 (November 1906–April 1907): 357–70. ⮭

- “I began collecting in the Indian Mutiny, and I need scarcely say that I am selling these old friends with great reluctance. . . . Had I been a rich man, I would have given them to India, their birth place.” Henry Bathurst Hanna to Charles Lang Freer, April 10, 1907. ⮭

- “Many of my books and pictures I have discovered in out of the way places, whilst great cities, where such things might fairly be looked for, have not yielded one to the most patient search.” Henry Bathurst Hanna, Catalogue of Indo-Persian Pictures and Manuscripts, Principally of the Fifteenth, Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries by Mughal Artists, Collected by Colonel H. B. Hanna (London: Dowdeswell and Dowdeswell’s, 1890), 5. ⮭

- Hanna, 5. ⮭

- For more on the terms of looting and the latter as “official pillage” in the nineteenth century, see Richard H. Davis, “Three Styles in Looting India,” History and Anthropology 6.4 (1994): 293. ⮭

- “Among my books, the Ramayana belonged to Akbar, the Koran to Jehangir, and the battles of Mahomet to the Nawabs of Oude. This, too, disappeared in the Mutiny, and was only recently unearthed in a remote village.” Hanna, Catalogue, 5. ⮭

- Hanna to Freer, April 16, 1907. ⮭

- “In fixing the value of my Collection, I took into consideration the length of time and difficulty I found in collecting the M.S.S. and Pictures, the high prices I paid for some of them, and the fact that such specimens are no longer obtainable in India, the supply being now practically exhausted. . . . I could get good prices for some of the Pictures & M.S.S. if I were willing to sell them separately, but I have always been loth [sic] to break up a Collection so unique both from a historical & artistic point of view.” Hanna to Freer, October 3, 1907. ⮭

- For example, the painting described as “The Emperor Jehangir in his Diwan-i-Khas, or Hall of Private Audience, A.D. 1605–1628” in the Hanna catalogue is now simply titled A Prince Holding an Audience and dated ca. 1750 (F1907.186). For the painting originally described as “Deer-stalking by Night, the young Emperor Akbar on Horseback. A.D. 1556–1605,” the identification of Akbar has now been removed and the date broadly assigned to the eighteenth century (F1907.199). ⮭

- Hanna to Freer, October 4, 1907. ⮭

- Freer continued, “As further evidence, I must say that after arriving in New York, I called upon your brother and borrowed three of his finest Persian books which I brought with me to Detroit to compare with other specimens of Persian art which I already owned. This kindness on the part of your brother helped me to learn the comparative value of my own specimens. . . . I appreciate the fact that your knowledge of Persian art is so far advanced that you can make purchases independent of other connoisseurs, but unfortunately for me I am only a beginner and I cannot as yet act entirely independent. I need all the coaching and training that I can get and I seek it in all possible directions. To you particularly, I am very greatly indebted for the little that I know.” Charles Lang Freer to Dikran Kelekian, October 28, 1907. ⮭

- “I was glad to hear that Boston Museum of Fine Art bought the Goloubew collection of Persian miniatures I have never been able to sell in 21 years time more than one dozen of Persian miniatures outside of Mr. Henry Wolters [sic] who always bought them … I have today the finest collection of Persian Miniatures in the word yet nobody even asks about it. Nevermind I always hope my time will come. I am not yet discouraged.” Kelekian to Freer, May 22, 1914. ⮭

- “India too will furnish both yourself and Mr. Maclean splendid entertainment and rare opportunities for the study of sculpture, especially at Ajanta and Ellora. Twenty years have passed since my first view of Ellora and certain impressions of the place made, pointed the way to many delights of recent years. . . . Quite a large number of our mutual acquaintances have brought me work concerning the beautiful objects brought to Boston by Mr. Okakura on his return to America last fall. I am very happy to know that he succeeded in securing numerous good things. The interest in early Chinese art is spreading rapidly throughout America, and the recent accessions at Boston will exert splendid influence throughout our country.” Charles Lang Freer to Denman W. Ross, January 26, 1913. ⮭

- Vincent Arthur Smith, “Colonel H. B. Hanna’s Collection of Indo-Persian Pictures and Manuscripts,” Indian Antiquary (June 1910): 182. ⮭

- Smith, 182, 184. ⮭

- Ananda K. Coomaraswamy to Charles Lang Freer, May 21, 1915. ⮭

- The full title of the volume is Rajput Painting: Being an Account of the Hindu Paintings of Rajasthan and the Panjab Himalayas from the Sixteenth to the Nineteenth Century, Described in Their Relation to Contemporary Thought with Texts and Illustrations (London: H. Milford, 1916). ⮭

- Coomaraswamy to Freer, July 12, 1916. ⮭

- Coomaraswamy went on to sketch out the scope of the purchase: “It would include 8 or 10 bronzes of great importance, some early stone heads, a hundred or more pictures, cartoons and drawings, and a few specially noteworthy specimens of decorative art, as well as some illustrated MSS.” Coomaraswamy to Freer, July 12, 1916. ⮭

- Coomaraswamy to Freer, July 12, 1916. ⮭

- Freer to Coomaraswamy, July 25, 1916. ⮭

- Freer to Coomaraswamy, July 25, 1916. ⮭

- Examples of related notes appear for the following works: Treatise on Hindu Mythology, now titled Selections from the Mahabharata (F1907.627); Marriage of Rama and Sita, now titled A Holi festival (F1907.255); Krishna. An Incarnation of Vishnu, now titled A musical mode (Sri Raga): Krisna and Radha on a terrace (F1907.248); and A Mourner, now titled A musical mode (varari ragini) (F1907.257). See “Art Inventories: Paintings; Persian and Indian; H. B. Hanna Collection,” Freer Papers, box 65, folder 13. ⮭

- For more on Coomaraswamy’s retention of part of his collection and its subsequent dispersal, see Brinda Kumar, “Collecting with Éclat: Coomaraswamy and the Framing of Indian Art in American Museums,” in Arts of South Asia: Cultures of Collecting, ed. Allysa B. Peyton and Katherine Anne Paul (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2019), 129–49. ⮭

- These included sixteen paintings and manuscripts purchased in 1923 and 1924: F1923.3a–zz, F1923.4, F1923.6 through F1923.12, and F1924.4 through F1924.10. ⮭