Creary, M., Peoples, W., Thatcher, L., & Fleming, P. (2023). Working toward anti-racist local health departments: The ARCC towards Justice project. Currents, (3)1.

The intertwined pandemics of racism and COVID-19 have been deadly for Black people and other communities of color. In the United States, these pandemics have put a spotlight on public health and the urgency of more fully integrating anti-racism into the field to better advocate for institutional and systemic changes that will facilitate good health. The spotlight shines bright on our contemporary situation, but the historical legacies of racism as embedded in the creation of the public health system are well documented. The introduction of public health systems is entangled with a sociopolitical environment deeply shaped by racial hierarchy, disparate resource distribution, and consequent health outcomes. To that point, Zambrana and Williams (2022) highlight W. E. B. Du Bois’s observation that “racial differences in health as reflecting differences in ‘social advancements’ and the ‘vastly different conditions’ under which Black and White people lived, indicating that the causes of racial differences in health were multifactorial, but primarily social” (p. 164). The legacy of racial inequities as adequately addressed by the public health system remains.

Like many other agencies of public health (Mendez et al., 2021), county health departments throughout Michigan in 2020 explicitly declared racism a public health crisis and declared a collective commitment to health equity (Slootmaker, 2022). Though frameworks like those offered by the Government Alliance on Race and Equity (GARE) do exist, they are not often tailored to the specific workings of local health departments. Public health professionals at local health departments do not always receive support to meaningfully implement anti-racist frameworks in their work portfolios. This is a sentiment we heard repeatedly in our work with a local health department. Local health department participants in this project, across demographics and organizational ranks, described experiencing high levels of fatigue in the midst of the public health crises of the last three years. They noted that this fatigue negatively impacts their capacity for incorporating what they see as additional labor to learn and integrate anti-racism into their work portfolios. As a result, existing racial-equity frameworks are often not incorporated into the day-to-day working of local health departments. Our research project was designed to better understand the constraints and affordances of incorporating and implementing anti-racist frameworks into one local health department and developing tools to better aid this work in the future of this health department and others.

This paper preliminarily reports on community-based collaborative research that addresses racism on the institutional level instead of the usual practice of interventional focus on marginalized communities. Our work was grounded in concepts from the public health critical race praxis (Ford & Airhihenbuwa, 2010), which draws from critical race theory to highlight the importance of “centering the margins.” We also draw on principles of community-based participatory research that are synergistic with anti-racist research (Fleming et al., 2023) and the concept of bounded justice (Creary, 2021).

Partnering with a county health department (CHD) in Michigan and key community stakeholders, we are developing and implementing the Anti-Racist Counties and Cities towards Justice (ARCC towards Justice) project. In this paper, we present our conceptual model on how anti-racist health departments can help achieve equity and justice, share how findings from our formative research with staff and community members will inform our novel Racial Justice Impact Assessment tool that will be cocreated between CHD staff and communities to aid in anti-racist transformation, and discuss initial challenges observed for this case that speak to larger challenges of transformational change.

In its efforts to increase anti-racist practices and outcomes in local county health departments, this project draws on the concept of “bounded justice,” a term coined by coauthor Creary (2021). As a racial equity analytic, bounded justice argues that even institutions trying to be anti-racist are still “bounded” in that they may not swiftly achieve health equity for their residents because the countervailing forces of structural racism are so strong. Equity is linked with notions of fairness and ethical concepts of justice—particularly distributive justice (i.e., a just distribution of resources according to needs). If health equity is improved by a need-based distribution of resources, it is easy to think that all we need to address equity is an equitable distribution of public health goods and resources (Creary, 2021). These standard interventions, however, in effect end up being surface-level solutions to deep, subterranean problems. These well-meaning attempts at justice are bounded by greater sociohistorical constraints.

This project draws on Creary’s approach to racial equity for two primary reasons. The first is to highlight the intersectional and interconnected nature of racial-equity transformation. Local health departments will have to go beyond the bounds of their particular organization and work broadly in their communities in order to address concerns that may seem beyond the immediate scope of public health but that are deeply connected to broader questions of racial equity in their communities. The second reason is to establish for ourselves and our research partners that racial equity work is beyond quick or easy solutions and requires a long-term and ongoing commitment rooted in individual and institutional-level stamina. This is a critical point given the way racial equity efforts developed in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder are being increasingly dismantled as the years progress (Kelderman, 2023). Local health departments grounded in a bounded justice perspective and anti-racist principles are better able to identify these “bounds” and are equipped with the tools to adaptively respond and counteract these forces to improve health.

Conceptual Model

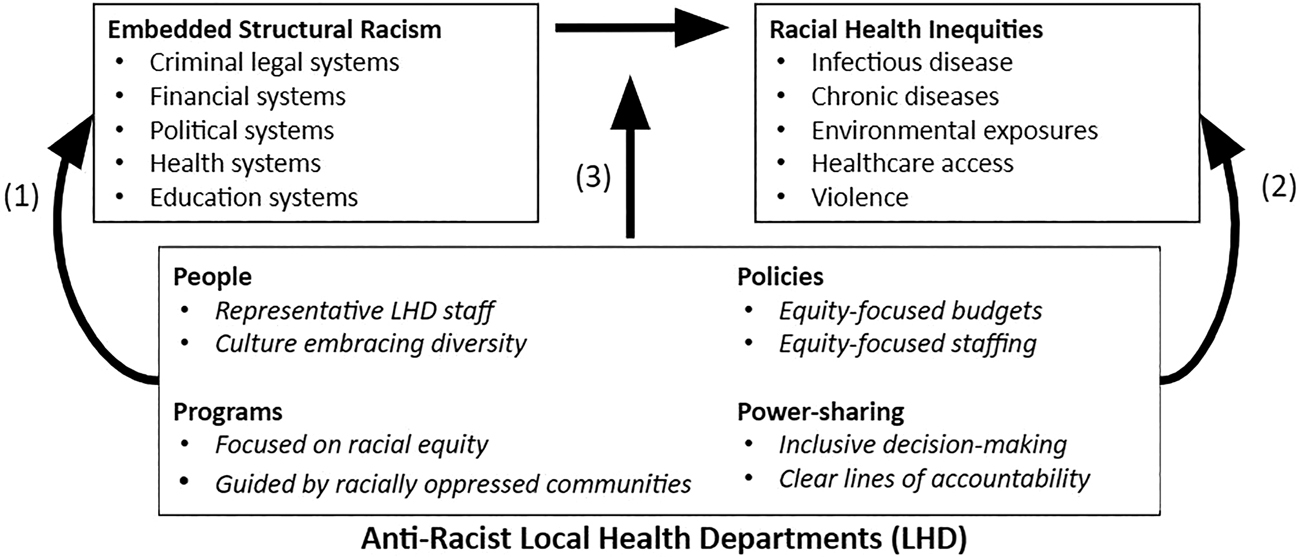

An anti-racist local health department can disrupt the fundamental relationship between structural racism and racial health inequities (see Figure 1). Structural racism is embedded within key institutions throughout society, similar to those in our criminal legal systems, financial systems, political systems, health departments, health-care systems, and educational systems (Bailey et al., 2017). These systems work synergistically to produce broad and persistent health inequities and poor health for racially marginalized communities. This fundamental relationship is represented by the black boxes and arrows in the model presented in Figure 1. Anti-racist local health departments will be able to disrupt this fundamental relationship in three key ways: first, anti-racist local health departments will engage in advocacy to transform other systems to become anti-racist (see arrow 1). Second, anti-racist local health departments will moderate and help reduce the negative health impacts of other systems on racially marginalized communities by engaging in cross-sector collaborations and partnerships with community-based organizations (arrow 2). Third, anti-racist local health departments will equitably provide direct services in racially marginalized communities following anti-racism principles (arrow 3).

Formative Research and Intervention Planning

We collected mixed-methods data to triangulate a response to Dr. Camara Phyllis Jones’s (2018) question “How is racism operating here?” and identified baseline levels of capacity for anti-racism among health department staff. Specifically, we conducted staff focus groups (n = 5) and a staff survey (n = 88). In addition, we facilitated several informal sessions with a team of county-wide community members who live in and identify with communities affected by health inequities and who help to guide some of the work of the health department. All study procedures have been approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board and the health department leadership.

Staff Focus Groups and Survey

We conducted focus groups with different segments of staff at the local health department, which included the senior CHD leadership team (four participants), the expanded CHD leadership team (nine participants), and two focus groups with other CHD staff members who are not part of leadership (seven participants and three subsequent participants). Focus groups were mixed race, with the majority of all participants being white. We recruited staff through an email sent by the university team asking for voluntary participation. Focus groups were facilitated by the authors with the goal of having at least one white-identifying and one Black-identifying facilitator at each session. Focus groups focused on three main topics: (1) a vision for equity at the health department five years in the future, (2) perceptions of readiness to work toward that vision, and (3) perceptions of where the health department is on its path toward anti-racism. All focus groups were recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed thematically.

Our data collection and analytic process were informed by the interpretive description approach that is focused on pragmatic knowledge-creation from qualitative data to improve health outcomes (Thorne et al., 1997; Thorne, 2016). Practically, this meant that we sampled people (community members and certain CHD staff) who could provide the most useful information to the research question, developed an interview guide for the focus groups in collaboration with leadership at the CHD to help provide useful information, and analyzed the data using strategies that kept the focus on questions such as “What is happening here?” and “What am I learning about this?”

All focus groups expressed some level of fatigue that undermined their ability to engage in anti-racism. While many participants felt anti-racist values were present, they also felt there wasn’t knowledge of how to operationalize those values and incorporate anti-racism into everyone’s portfolio. Hiring practices along with the restrictions, protections of union contracts, and county rules that superseded CHD policies often came up as examples of gaps between CHD values and practices. Moreover, CHD leadership and staff with longer tenures tended to be more pessimistic about the department’s progress around racial equity than newer staff because they had seen variation in progress over the years.

The staff survey was sent to all 160 staff members at the CHD by the university research team, with CHD leadership encouraging survey completion at staff meetings and via email. The survey was anonymous but included questions on participant demographics, characteristics of roles, attitudes related to race and racism, and perceptions of health department practices related to racism and equity. The 88 participants who completed the survey identified as follows: 12% Black or African American, 66% White, 2% American Indian or Alaskan Native, 7% Asian/Asian American, 2% Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, 3.5% Middle Eastern/North African, 5.8% Hispanic/Latinx, and 1% not listed. To ask about attitudes related to race and racism, we adapted items from the Pew Race in America scale (Menasce Horowitz et al., 2019). To ask about perceptions of health department practices, we adapted the Health Equity and Social Justice discussion guide to ask about 11 different domains of practice and rank the health department (1 to 4) on equity (Bloss et al., 2018).

The survey revealed that most staff think the CHD is moving toward more equity and anti-racism. Consistent with the focus group findings, survey findings indicated that equity practices that appeared to be stronger were focused on the domains of “leadership” and “values” but less so on “community partnerships” and “hiring/retention.”

Community Involvement

Guided by community-based participatory research (Fleming et al., 2023), the meaningful inclusion of community members has been a key aspect of our work with the CHD. As such, we planned on including community focus groups as part of formative data collection. We began our community engagement efforts by meeting with an established group of community advocates convened by the CHD and modestly compensated for lending their time and perspectives to the group. This group is composed of individuals from six communities within the county that disproportionately experience poor health outcomes. These communities are primarily, but not exclusively, composed of people of color, and many of the poor health outcomes they experience are due to the structural racism that has economically and socially disadvantaged these neighborhoods.

An initial meeting with the community advocates’ group revealed that the group was hesitant to recruit community members to our focus groups. The predominant reasoning was that they had previously shared concerns about racist practices at the CHD and did not feel like there was meaningful action afterward. They expressed frustration with what they perceived to be a purely extractive process with no returns on their investment of time and insight. The group’s experiences reflect long-standing problematic practices in the history of university-based research in communities and marginalized communities in particular (Dempsey, 2010; Lane et al., 2022). In the group’s response to our request, our team was reminded that we were implicated in that history by virtue of our university affiliation and we had to attend to that history and do more to earn this group’s trust and sufficiently learn about the history of racial equity at the CHD. In response to the feedback we received, we pivoted toward trust-building by meeting with individual community members as well as attending community events. Slowly we were able to learn more specifics about the challenges the group faced in their work with the CHD. As a result, our team did due diligence by first listening and then believing what we were hearing from the group about their past experiences with the CHD. Deep listening and cultivating belief led us to do more background research by looking into documents and talking with CHD staff and other community members about the relationship between the CHD and the community. We also made regular updates to the group about how we were following up on their guidance and what we were learning in the process. We measured the success of our efforts by how the engagement of the community advocates’ group changed over time. The more we met with the group, reported back on our efforts, and displayed a growing understanding of the community and CHD relationship nexus, the more eager group members were to engage and support the next phase of the project.

Challenges to community engagement in research have been well documented (Akintobi et al.,2020; Holzer et al., 2014; Weerts & Sandmann, 2008). Our study is designed to contribute to that literature with a research model that is iterative and responsive to the voices of the community. As such, we outline a few challenges encountered in the process thus far.

Confusion between perceptions of community input versus cocreation: When initially encountering the community group to introduce and begin engagement in the project, many members preemptively assumed that we wanted input on a finished product despite our insistence that the product was not developed and would not be developed without the involvement of the community. They were accustomed to research processes that were largely extractive and, as a result, it took many months of intentional effort to build trust and repair relationships before the community came to understand and, more importantly, trust our desire to collaboratively engage.

Internal staff resistance from constant criticism of COVID-19 response as racist: We partnered with the CHD in the midst of the public health response to the global COVID-19 pandemic. By the time we began initial data collection with staff, burnout and frustration associated with the CHD’s COVID-19 response were apparent. In particular, talk of anti-racism did not land well with some staff, including staff of color, who felt that the CHD and its employees were unfairly criticized for COVID-19 initiatives, such as the vaccine rollout campaign, in the county. These staff felt that anti-racism had been weaponized against them and they seemed concerned that engaging in our anti-racist project would only open them up to further criticism.

Lack of acknowledgment and transparency of historical engagement with community: When the research team began engagement with the community group, the group expressed frustration and concern about historical practices of alleged partnership with the CHD. Group members noted past projects in which information was collected but substantive follow-up never occurred. As a result, the research project started with inherited distrust from previous engagement practices.

Insufficient understanding of equity and diversity: Despite working toward increasing the staff’s knowledge base around diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI), an increase in DEI training, and political will from leadership, some staff still did not understand the value of a diverse workforce and the benefit of power-sharing with community groups. For example, some white senior staff struggled with how to integrate DEI into core CHD processes such as hiring and portfolio management. These staff noted that they were unsure whether they should hire the candidate who displays the best “fit” for the job and organization or “the most diverse” candidate, indicating their belief that these two characterizations are mutually exclusive. Seeing diversity as antithetical to hiring the best candidate and hiring for “fit” are both examples of how racism impedes the development of more equity-focused hiring practices and outcomes. The individual viewpoints of these senior white staff contribute to the overall organizational beliefs of the CHD and, left unchallenged, will hinder any potential cultural shift at the CHD.

Cocreation of the Racial Justice Impact Assessment Tool

With these challenges in mind, the research team proceeded with successful trust-building practices and data collection with the community group and CHD staff. After data collection, we shared the results with the health department, shared what we had accomplished to date with the community, and planned for the next phase of the project. The goal of the next phase is to cocreate a tool to help examine CHD processes, programs, and policies for alignment with anti-racist principles. We have developed a framework to guide this, called the “Four Ps of Anti-Racist Practice,” which include preconceptions, people, power-sharing, and policies. This framework mirrors our conceptual model, with one notable difference: the removal of “programs” and the inclusion of “preconceptions.” This change reflects what we learned in our survey and interview data about the importance and impact of individual and collective ideas and opinions about racial equity on organizational progress at the CHD. In addition to the input of the CHD staff and community partners, the four Ps framework is also informed by other frameworks such as the Racial Equity Impact Assessment (REIA) used by the organization Chicago United for Equity (CUE) and the Government Alliance on Race and Equity (GARE) (Brar, 2023; Chicago United for Equity, 2023; Government Alliance on Race and Equity, 2023). The Board of Health in this CHD’s locale declared racism a public health crisis and committed to the “dedication of Department resources to deepen this work in solidarity with social movements for racial justice and in accordance with the Health Department’s vision and guiding principles for health equity”(Washtenaw County Board of Health, 2020). With this commitment in mind, the work of the Racial Justice Impact Assessment tool is to help align practices and policies with these stated commitments.

The outcomes of this work are yet to be known since this process is at its midpoint. The plan in this work is to bring together a group of six community leaders who represent different neighborhood groups’ experiences around health inequities and six health department staff members who are instrumental in program planning and policy development. This small working group will come together for a total of 12 facilitated hours of cocreation that will begin with relationship- and trust-building among the group-level setting around the concepts of racism, white supremacy, and related topics; cocreation of the tool; feedback from other community members and staff; piloting the tool on a program or policy; and disseminating the tool to staff and community members. We view the process as important as the outcome.

The tool will ultimately be able to formally identify the bounds of anti-racist action as well as the opportunities. It is this work that will help staff and community hold leadership accountable to not only seize opportunities but also act as advocates for addressing the structural barriers that are constraints to progress. For example, in the information-collection phase, we frequently heard about union contracts as a barrier to equitable hiring practices because seniority was prioritized over and above everything else. In this example, the tool will help to identify the changes in hiring practices that would help move the health department toward anti-racist principles and name the constraints in place so that they could attempt to address them. It is within this process that institutions can break the current cycles of inequity and better target those structural barriers in future actions.

Conclusion

Institutional transformation is a promising approach to disrupting structural racism but a deeply complicated process. What has been made evident for us is that even with so-called increased capacity toward DEI knowledge or aptitude, the behaviors, beliefs, and attitudes matter the most for change to be effective. Transformation calls for a gradual shift in cultural norms of the workplace, which can then lead to a shift in program and intervention design at county health departments. In our work, we encountered efforts to protect white staff from discomfort in the process of institutional transformation. Relatedly, there was a struggle to reckon with what power-sharing with the community could actually look like. We also found savvy community members who were used to research and its promises and as a result, were understandably mistrustful of the process. These members were fatigued about new tasks related to equity from CHD staff. Despite these challenges, taking on this project allows us to directly unearth some of the barriers to greater anti-racist action by the CHD and begin to strategize for how to overcome them. While the project is only one small step in the direction of an anti-racist institutional transformation, it has allowed us to push action to happen from within the CHD itself. The arc of the moral universe is long—like the process of institutional change—but concerted and collective efforts can help it bend toward justice.

Bios

Dr. Creary is an interdisciplinary social scientist who has worked with the sickle-cell and bleeding disorder community as a scientist, policymaker, and public health researcher for over 20 years. Her primary research interests include how science, culture, and policy intersect, particularly around ethical, legal, and social concerns (ELSI). Through a health-equity lens and using historical and ethnographic methods, she uses sickle-cell disease as a case to investigate simultaneous constructions of race and science via the development of policy. Her anti-racist research also theorizes how embodied outcomes of accumulated injustice and exclusion inhibit the receipt of justice, even via well-meaning programs, policies, and technologies designed to build equity. She speaks on topics of justice, racism, and anti-racism in health and biomedicine, COVID-19, identity politics in health, and bioethics. She has been published in Social Science & Medicine, BioSocieties, the Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, the American Journal of Bioethics, and JAMA Open Network.

Dr. Paul Fleming focuses his work on the root causes of racial health inequities and strategies to address them. He conducts community-based participatory research focused on the health needs of Latinx immigrants in Michigan and examines how to best integrate anti-racist principles into public health training and practice. He also is a member of Public Health Awakened and contributes to community organizing efforts to promote health through social change. He received his PhD from the University of North Carolina’s School of Public Health and MPH from Emory University.

Dr. Whitney Peoples serves as the inaugural director of diversity, equity, and inclusion. She brings over 20 years of experience in feminist and critical race research, activism, and teaching to her work at the School of Public Health. She earned a PhD in women’s, gender, and sexuality studies from Emory University. She has spoken and written on the intersections of race, gender, health, and popular culture, taught broadly in the areas of women’s and gender studies and African American studies, and published critical essays on topics that include Black autobiography, advertising for oral contraceptives, and anti-racist teaching. She is a cofounder of the Black Feminist Health Science Studies Collective and coeditor of the book Radical Reproductive Justice: Foundations|Theory|Practice| Critique.

Lindsey Thatcher is a public health professional who has worked with diverse populations in a variety of contexts, from the National Malaria Control Program in The Gambia as a Peace Corps volunteer to public health programming with refugees and migrants on the US–Mexican border. She received her master’s in public health from the University of Arizona in 2018 as a Paul D. Coverdell Peace Corps fellow. Most recently, Thatcher acted as the program manager for the Contact Tracing Corps at the University of Michigan as part of the COVID response. She has been working as a research program manager since 2022 at the School of Public Health at the University of Michigan.

References

Akintobi, H., Tabia, Jacobs, T., Sabbs, D., Holden, K., Braithwaite, R., Johnson, N., Dawes, D., & Hoffman, L. (2020, August 13). Community engagement of African Americans in the era of COVID-19: Considerations, challenges, implications, and recommendations for public health. Preventing Chronic Disease, 17. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/93359.https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/93359

Bailey, Z. D., Krieger, N., Agénor, M., Graves, J., Linos, N., & Bassett, M. T. (2017). Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: Evidence and interventions. The Lancet, 389(10077), 1453–63.

Bloss, D., Canady, R., Daniel-Echols, M., & Rowe, K. (2018). Health equity and social justice in public health: A dialogue-based assessment tool. Michigan Public Health Institute. https://www.mphi.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/HESJ-Dialogue-Based-Needs-Assessment-MPHI-CHEP.pdf

Brar, N. (2023). Niketa Brar (MPP ’15) on racial equity impact assessment. Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy. https://fordschool.umich.edu/event/2023/niketa-brar-mpp-15-racial-equity-impact-assessmenthttps://fordschool.umich.edu/event/2023/niketa-brar-mpp-15-racial-equity-impact-assessment

Creary, M. S. (2021). Bounded justice and the limits of health equity. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 49(2), 241–56. https://doi.org/10.1017/jme.2021.34

Chicago United for Equity. (n.d.). What is an REIA? Retrieved October 2022, from https://www.chicagounitedforequity.org/approach

Dempsey, S. E. (2010). Critiquing community engagement. Management Communication Quarterly, 24(3), 359–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/0893318909352247https://doi.org/10.1177/0893318909352247

Fleming, P. J., Stone, L. C., Creary, M. S., Greene-Moton, E., Israel, B. A., Key, K. D., Reyes, A. G., Wallerstein, N., & Schulz, A. J. (2023). Antiracism and community-based participatory research: Synergies, challenges, and opportunities. American Journal of Public Health, 113(1), 70–78. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2022.307114

Ford, C. L., & Airhihenbuwa, C. O. (2010, October). The public health critical race methodology: Praxis for antiracism research. Social Science & Medicine, 71(8), 1390–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.030

Government Alliance on Race and Equity. (n.d.). Racial equity toolkit: An opportunity to operationalize equity. Retrieved January 19, 2023, from https://www.racialequityalliance.org/resources/racial-equity-toolkit-opportunity-operationalize-equity/https://www.racialequityalliance.org/resources/racial-equity-toolkit-opportunity-operationalize-equity/

Holzer, J. K., Ellis, L., & Merritt, M. W. (2014). Why we need community engagement in medical research. Journal of Investigative Medicine, 62(6), 851–55. https://doi.org/10.1097/JIM.0000000000000097https://doi.org/10.1097/JIM.0000000000000097

Jones, C. P. (2018). Toward the science and practice of anti-racism: Launching a national campaign against racism. Ethnicity & Disease, 28(suppl 1), 231–34. https://doi.org/10.18865/ed.28.S1.231

Kelderman, E. (2023, January 20). The plan to dismantle DEI. Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/the-plan-to-dismantle-deihttps://www.chronicle.com/article/the-plan-to-dismantle-dei

Lane, A., Gavins, A., Watson, A., Domitrovich, C. E., Oruh, C. M., Morris, C., Boogaard, C., Sherwood, C., Sharp, D. N., Charlot-Swilley, D., Coates, E. E., Mathis, E., Avent, G., Robertson, H., Le, H.-N., Williams, J. C., Hawkins, J., Patterson, J., Ouyang, J. X., & Spencer, T. (2022). Advancing antiracism in community-based research practices in early childhood and family mental health. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 61(1), 15–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2021.06.018https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2021.06.018

Menasce Horowitz, J., Brown, A., Cox, K. (2019, April 9). Race in America 2019. Pew Research Center’s Social & Demographic Trends Project. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2019/04/09/race-in-america-2019/https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2019/04/09/race-in-america-2019/

Mendez, D. D., Scott, J., Adodoadji, L., Toval, C., McNeil, M., & Sindhu, M. (2021). Racism as public health crisis: Assessment and review of municipal declarations and resolutions across the United States. Frontiers in Public Health, 9. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2021.686807https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2021.686807

Slootmaker, E. (2022, July 28). Nearly 20 Michigan communities have declared racism a public health crisis. What happens next? Second Wave Michigan. https://www.secondwavemedia.com/features/racismpublichealthcrisis07282022.aspx

Thorne, S., Kirkham, S. R., & MacDonald-Emes, J. (1997). Interpretive description: A noncategorical qualitative alternative for developing nursing knowledge. Research in Nursing & Health, 20(2), 169–77. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-240X(199704)20:2%3C169::AID-NUR9%3E3.0.CO;2-Ihttps://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-240X(199704)20:2%3C169::AID-NUR9%3E3.0.CO;2-I

Thorne, S. (2016). Interpretive description: Qualitative research for applied practice. Routledge.

Washtenaw County Board of Health. (2023, June 30). A resolution naming racism as a public health crisis and confirming our collective commitment to health equity in Washtenaw County. https://www.washtenaw.org/DocumentCenter/View/17190/Resolution-Racism-is-a-Public-Health-Crisis-June-2020-FINALhttps://www.washtenaw.org/DocumentCenter/View/17190/Resolution-Racism-is-a-Public-Health-Crisis-June-2020-FINAL

Weerts, D. J., & Sandmann, L. R. (2008). Building a two-way street: Challenges and opportunities for community engagement at research universities. The Review of Higher Education, 32(1), 73–106. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.0.0027

Zambrana, R. E., & Williams, D. R. (2022). The intellectual roots of current knowledge on racism and health: Relevance to policy and the national equity discourse. Health Affairs, 41(2), 163–70. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01439https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01439