Introduction

For decades, designers have been encouraged by thought leaders, their peers, their professional organizations, and their disciplines at large 7 to evolve their design practices in ways that can be qualified as “socially responsible” and “socially innovative.” Thus, guided by intentions rooted in striving to ensure positive social, economic, and sometimes political and environmental impacts, many designers have leapt into the artisan sector with the goal of improving the livelihoods of the artisans with whom they interact to produce a wide variety of goods. The potentially positive roles designers can play across the varied communities of artisans around the world has been affirmed by many global organizations like Aid to Artisans and Artesanías de Colombia because they facilitate, “an interface between tradition and modernity, helping match craft production to the needs of modern living.” 8 In fact, the default model for designers working in collaboration with artisans, within which we have participated, and which is used by established and emerging companies, NGOs and nonprofits, as well as governments across the Global South, typically involves a designer being hired to travel to a given community to engage with its artisans in various ways that, in the end, result in a product line or accessories collection that will be exported and sold in mostly G20 nations.

Those connections between artisan-produced goods and the markets within which they are sold do not usually originate from within a particular community of artisans, but instead are imposed on them by the designer with whom they are collaborating, or a brand manager, founder, merchandising director, or project donor. This “Made By” model 9 is very much predicated on designers “parachuting in” to communities of artisans across the Global South for brief periods of time, usually from one week to one month. They arrive with market-ready and trend-aligned designs most often targeted at buyers in western Europe and the United States, and they bring these ready to hand off to artisans to execute. Additionally, although the projects that the authors have undertaken with the variety of indigenous artisans with whom we have worked purport to be the results of “human-centered” and “co-designed” processes, they are almost never produced within a span of time that allows for the artisan to function as a creator rather than as a maker. (Most artisans are approached because of their mastery of practicing a given craft, which helps ensure that the goods they produce will be produced effectively and at a high level of quality by a given deadline.) Most artisans are also rarely allowed enough of a production timeline to afford them opportunities to fulfill any types of creative roles regarding the development of the goods they are commissioned to make. All of these factors combine to ensure that most artisans never get the opportunity to work as anything other than inexpensive labor tasked with creating artifacts that range from ceramic ware, decorative wood carvings, woven pieces, baskets, jewelry, and thousands of other items that are eventually sold to buyers often far from where they were made. Although the artisan sector is the developing world’s second largest employer, the more than 200 indigenous and traditional artisans with whom we have worked directly in Guatemala and Colombia live in poverty or have at least one basic human need that is unmet (e.g., they live in precarious housing conditions, and only have access to low-quality schooling and healthcare). Within the communities that most of these artisans live and work, each of the authors has heard many stories of a designers’ well-meaning efforts to increase the economic and social fortunes among a particular artisan group not yielding positive results. A common example of this helps to illustrate the magnitude of this problem: many artisan communities are often talked into taking on a high quantity of one-off projects that forces those working within them to re-organize themselves to fulfill on time. The businesses that hire these communities to do this incentivize these transactions by promising them more work in the future, which is a promise that is all too often not kept.

The business models of many artisan sector brands rely on their paying local, in-country minimum wages (these are not necessarily “fair” nor “living”) to artisans in exchange for their production of craft products (or so-called intermediate goods, such as textiles) that can be marketed globally. Instead of perpetuating gig economy-like models 10 that neither offer sustainable income nor social security to those artisans who produce them, the authors propose the following question as a means to suggest a positive alternative for operating these business models, at least from the artisans’ points of view: what if designers stopped continuing to demand that the artisans they commission to produce to sell in Western markets conform to Western socio-cultural perceptions and frameworks for what artisan-produced work should look like? While the maintenance of various aspects of a given artisan community’s invaluable cultural heritage is often the starting point for a designer or brand founder’s interest in supporting that community, the demands imposed by global market forces usually require some modifications to many of the traditional skills that these artisans practice. These can include but are not limited to the incorporation of new techniques and machine-based production methods into an artisan community’s specific working processes in order to improve production efficiency. Both of these practices have been shown to contribute to the disruption of an artisan community’s socio-cultural and even political and technological fabrics. The scholarly work of anthropologist Brenda Rosenbaum has highlighted that “…global markets have led to the deeper impoverishment of artisans, to commodification and alienation, and to the loss of important cultural traditions.” 11

Most collaborative projects undertaken between designers and artisans default to being guided in their development by traditional “design thinking” methodologies, 12 and creative control is rarely shared with the latter group, insisting on externalizing the designing to the designer or consultant with claims that they are culturally closer to the craft good’s final marketplace. Furthermore, though these design-led engagements may at times kick off with a thorough assessment of community needs, client-driven projects often have quick timelines which need to move rapidly toward commercial ready-for-sale product lines. Maria Cristina Gómez, an indigenous Wayúu artisan from La Guajira in northern Colombia, in a semi-structured interview with Professor Lawson Jaramillo at the craft fair Expoartesano in Medellín reflected on these requirements of speedy work and generally on the framework imposed upon her by designers, “By imposing [market] expectations, designers are asking us to become industrialized. We’re launched into the void.” She also affirmed interest in working with designers to generate additional income through the sale of their craft goods but remained most concerned about one-off projects as they do not lead to ongoing partnerships, and therefore do not result in sustainable income for the artisan community. How might designers shift their ways of working to position artisans as true partners and not simply workers-for-hire? The shift should celebrate the artisan as a creative practitioner and master of their craft and adapt to their cultural norms and temporal frameworks (especially in the case of indigenous communities). What becomes possible in models in which the frameworks are not necessarily driven by capital and consumerism, but by people (artisan livelihoods) and values (indigenization)? With literature pointing to indigenization as a path towards sustainability 13, products that come out of the artisan sector are well poised to be as ethical and sustainable as the brands’ marketing materials claim to be 14.

What follows is an overview of the process the co-authors have used and have observed as typical for intermediaries working with artisans who wish to market their work in societies beyond their own. Within the context of our academic work in the DEED Research Lab (co-founded and directed by Professor Lawson Jaramillo), we have supplemented knowledge gained through fieldwork with secondary research, drawing from academic literature from anthropologists, social impact designers, in-progress work from graduate students of design and craft, and mainstream publications focused on the current business trends of artisan sector brands. The co-authors include notes from ethnographically guided fieldwork engagements, and suggestions for more sustainable, and decolonized, ways forward.

Identifying an Artisan-based Community with Which to Partner as a Co-Designer

When artisan-designer projects commence after a period of trust-building, they’re more likely to result in mutually beneficial outputs, with artisans participating as true partners and with creative input. These initiatives often start with a designer (or artisan brand founder) circumstantially living in proximity to a community skilled in a particular technique or medium; and that immersive experience serves the designer or founder to understand firsthand the community’s needs, their histories, and the role craft has played in their culture and daily life. Though the duration of that life-in-community is an important factor in the project’s evolution, what is most critical is how the designer or founder address issues of positionality, power, and privilege in the business model they develop. Most projects the co-authors have experienced firsthand for the past 15+ years unfortunately begin with a desire to bring artisan-produced goods to a particular market, and the assumption that artisans-as-laborers will be the means to achieve this. In addition to the questions of time and goal-setting, how a designer is introduced to a given community also sets the tone for potential collaboration. Ideally, the arrival follows a formal invitation from the artisans, and includes a commitment from the designer or founder to long-term support, rather than the flimsy promise of a single collection of artifacts that that can be sold only once. Furthermore, of equal importance to their arrival and introduction to a particular group of artisans, designers must also clearly specify when a given project will end, a factor that is often guided by how many resources may be available to complete it. 15

In one fieldwork program in San Antonio Aguas Calientes, Guatemala, Professor Lawson Jaramillo and the DEED Lab team struggled to build trust with the local artisan community of Mayan backstrap loom weavers. It took several working sessions over a period of weeks to realize that the major barrier to open and honest communication was, in fact, how the Lab’s team had been introduced to the community. The local town government (the governor’s office of San Antonio Aguas Calientes, with which not everyone in the artisan group was politically aligned), had suggested the DEED Lab team was arriving with monetary help, which was not at all the intention, and in fact goes against the Lab’s ethical fieldwork framework 16. The team tried their best to begin their work with this artisan community as active listeners (see Figure 1) and facilitating workshops in which artisan voices and concerns would be centered. Despite these efforts, the artisan community’s expectations were biased from the very start. The Lab’s interests to assess the community’s needs and offer workshops that would benefit their craft activities had not been properly described, which was clearly further exacerbated because of the realities of the Guatemalan context — decades of top-down charity 17 and short-term religious missionary work with little evidence of impact 18, and centuries-old histories of colonization and the psychological and physical trauma that accompanies it.

Designers, educators, and researchers need to develop a broadly informed and deeply examined understanding of a specific community (through secondary research focused especially on histories and ideally also time spent in situ) to know exactly how long-term artisan-designer initiatives should be implemented and sustained. If artisans are to benefit in meaningful ways from their interactions with designers and founders, then these initiatives must center the needs, time, and creativity of the community, to avoid solely extractive interactions. To avoid imposing Western frameworks, designers must be prepared for delays due to familial or weather events that affect the artisans’ abilities to engage in their work, they must appreciate the local spatio-temporal frameworks, and meaningfully honor artisans as creative practitioners and not just as inexpensive labor.

Objectively Assessing the Needs and Wants of Artisan-based Communities

The second step in artisan-designer collaborations that are expected to go beyond just one project or collection, is usually an assessment of community needs. Though this well-intentioned framework is meant to align support initiatives with local necessities, it is challenging for designers or other intermediaries to make room for meaningful input if they’ve arrived with the pressures of a sponsor (corporate or non-profit donors) who expects a ready-for-sale collection as the outcome. This is yet another reason why commercial initiatives are not the path towards long-term sustainable support — the diversity and scale of community needs are most often misaligned with the for-profit goals of such endeavors.

As an example, consider Colombia where 76% of artisans live below the poverty line 19 (defined in 2019 by the World Bank and the former Encuesta Continua de Hogares as $57 USD per month), 40% of the sector resides in rural areas, 20 and 81% of poor rural homes lack a connection to potable water. 21 Now imagine being a designer who travels to the region of La Guajira, home to the indigenous Wayúu people, and one of the country’s driest places. You arrive with a corporate sponsorship 22 and the pressure of a timeline that is expected to result in an artisan-made collection to be displayed in Colombiamoda (Colombia’s “fashion week”), and maybe (hopefully?) even marketed to an international audience via one of myriad U.S. and Europe-based trade shows. You know better than to jump straight into a co-design workshop and therefore facilitate a needs assessment activity with what is hopefully a group of community members that can effectively represent its various constituencies. You expect to hear them speak about “income generation,” “craft making,” “artisan knowledge,” and “cultural heritage” because that is what you—as a designer—have come prepared to facilitate during the evolution of the workshop that you have planned according to your limited and perhaps assumptive understandings of and about this community. Instead, community members wish to tell you about the kinds of challenges they must confront to get through each day successfully: “we need sustainable income,” “we don’t have clean drinking water,” and “our children’s school doesn’t have teachers.”

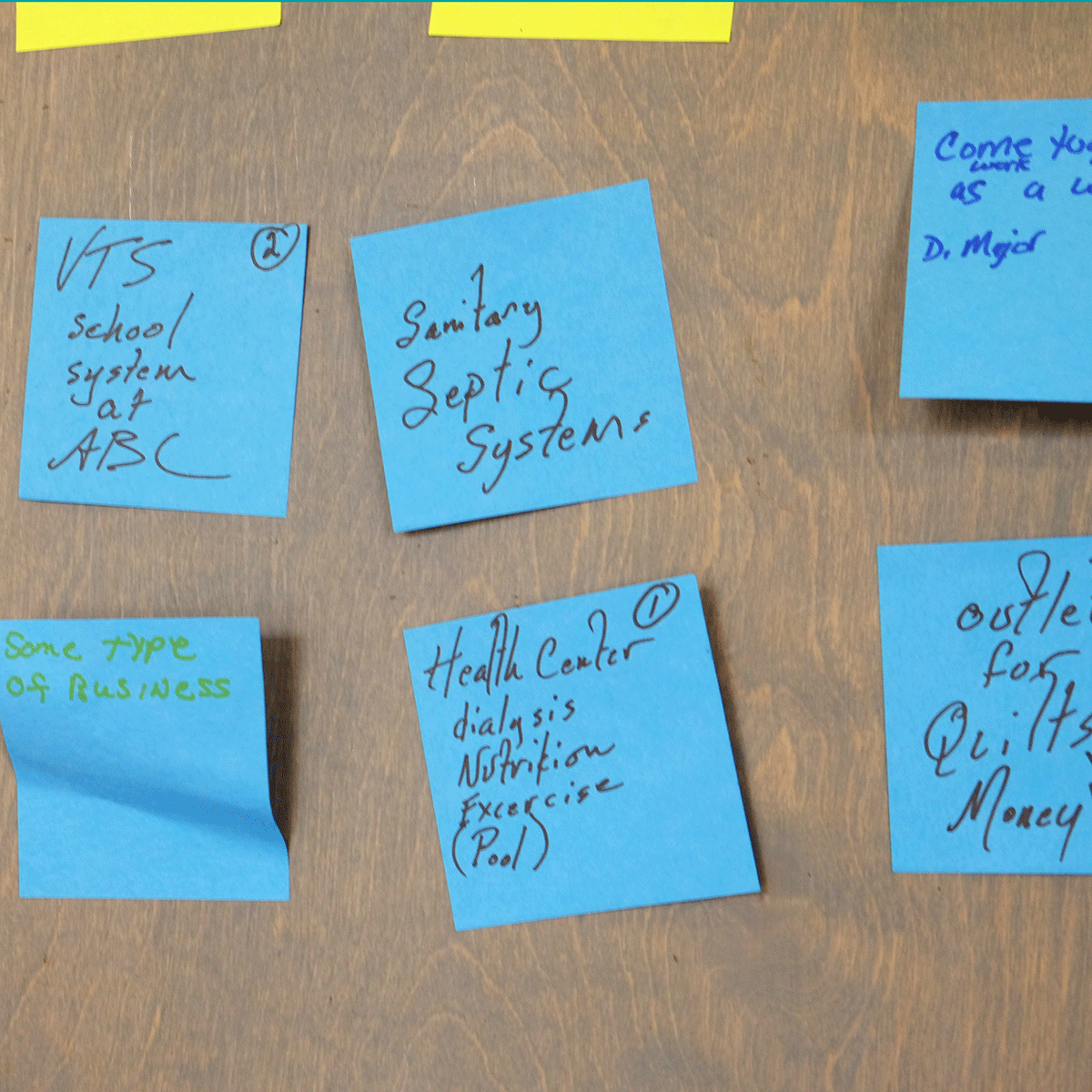

In many ways, arriving with a sponsor already makes a needs assessment less useful. Designers and other intermediaries should strive to first assess what the community really needs (see Figure 2), and then figure out together how to appropriately partner with its members, if at all. The community members often know best how to invest resources that come their way, and do not need to also be overburdened by an expectation to produce goods and products to prove they are worth our admiration and support.

FIGURE 2: Documentation from a Needs Assessment workshop operated with quiltmakers in Gee’s Bend, Alabama (United States) that reveals needs rooted in community health and well-being, education, and economic opportunities that exist well beyond the scope of any craft-centric initiative. Photograph by Cynthia Lawson Jaramillo.

Building and Sustaining Capacities for Co-Designing and Producing among Artisan-based Communities

“Whose capacity are we building? Why and with whose input did we determine what capacities are needed?” These are questions that designers who wish to work with artisans must pose as they begin to plan the kinds of making endeavors with given groups of artisans if these are to prove mutually beneficial, and, in even the near term, sustainable. When designers introduce capitalist-based frameworks into indigenous communities, they are immediately confronted with a lack of. Specifically, this means that between artisans and their intermediaries (who are often designers), there are many instances where designers have access to logistical and technological infrastructures, technologies, socio-cultural networks and paradigms, and economic systems that the artisans do not. These include but are not limited to being able to access digital technologies and having the literacy necessary to operate them effectively, as well as English fluency, the ability to produce quality at scale, and experientially gained knowledge of what is marketable in the United States and Europe. Therefore, the reason designers determine that capacities need to be built is often because they are in fact introducing goals, expectations, and ways of working that are commerce-centric and that actually counter indigenous ways of living. Like the impositions brought by the Spaniards to the Americas in the 1500s, designers often engage in ways of planning and working that in fact replicate many of the consequences of colonization. And the insistence on relying on the operationalization of such frameworks, as mentioned above, has led to doing more harm than good in many of these communities.

A contemporary example of capacity-building (gone somewhat awry) is the case of the “tejido en chaquiras” (literally, “weaving in beads”) in Colombia (see Figure 3). Jhonier Puchicama Castillo, a fourth generation beader, shared with designer, researcher and co-author Valentina Palacios that this technique, even though it is marketed as indigenous craft from the Embera community, was actually brought to Colombia just a few decades ago by local artisans who had attended a craft conference in Panama. On the one hand, it’s a wonderful example of how communities can choose to advance their own livelihoods by learning new skills. On the other hand, it puts into question the cultural heritage goals that drive many of these initiatives. Though perceived as an ancestral Embera technique, “tejido en chaquiras” in fact was recently learned.

Artisan sector consultant, designer and co-author of this article Valentina Frías participated in a project in 2021 that highlights how resource-constrained living and making can affect creativity. This project took place within the Orillo Initiative (@orillo.artesanias on Instagram), in Turbo, Colombia. This artisan community lives in the Urabá region, where the vast majority of Colombian banana and plantain exports are grown. During a Zero Waste Set Design workshop (in this context, the term “set” refers to a physical construction against which photographs can be taken), which was planned as an exploratory way for the artisans to make products from what they could find on their own land, the community members worked together to brainstorm, collect plants, and build a photography set in the backyard of the group leader’s home. To create additional benefits for the community, the workshop was also designed to support the development of a storytelling strategy, or strategies, that would effectively communicate key aspects of the Orillo culture to a broad audience (with the sets created as backdrops for their artisanal work to be photographed, as seen in Figure 4). Though the access to supplies to develop crafts is limited, clearly this was not necessarily an obstacle for the community’s potential creative process. Orillo also did not need new capacities. Instead, they had a lot to teach Frías about the artisans’ land and resources, as well as about the creativity that can emerge even when supplies are scarce.

FIGURE 3: Analicia, a woman from the Embera Katios Tribe, while she was beading with "chaquiras" (beads) as part of a Fe Handbags campaign in Medellín, Colombia. Analicia was one of the 200+ members of this tribe who were displaced from Chocó, Colombia to Medellín during the Colombian civil war that transpired between 1964 and 2018. Photograph by Andrés Ochoa.

FIGURE 4: The Orillo artisan initiative in Turbo, Colombia needed high quality photographs of their handicrafts. Here depicted are two artisans in the set they designed, using only locally found natural materials, during the Zero Waste Set Design workshop led by artisan sector consultant and co-author Valentina Frías. Photograph by Valentina Frías.

What occurred in Orillo is a clear example of a community identifying and mobilizing existing, but often unrecognized, assets. If co-author Frías had arrived with a brief to create a particular, extant type of a set design against which photographs could be shot, then she and the artisan community would’ve most likely focused on building with materials that are typically used to design these types of sets (e.g., wood and fabric). Instead, because she designed a workshop guided by much more open-ended parameters, which included prompts for those involved to explore the local land and its resources, the community chose plantain leaves (typically used solely as fiber for their craft goods), as well as dried flowers, coconuts, and other biowaste that would otherwise have been discarded, to design this set. This is an example of an Asset Based Community Development (ABCD) strategy, which is guided by a set of principles that, if effectively applied, can help ensure sustainable, community-driven development. 23 The premise of ABCD is that communities can propel the development process that guides a particular initiative themselves by making use of often unrecognized, local assets, and, in so doing, respond to and create local economic opportunities. This premise aligns with anthropologist and design educator Dori Tunstall’s invitation to consider "design thinking [as] based on our ability to be intuitive, to recognize patterns, to construct ideas that have emotional meaning as well as being functional, and to express ourselves in media other than words or symbols.” 24 In this way, we can all apply design thinking and design anthropology by taking advantage of already-existing capabilities and work towards design innovations without necessarily insisting on having to utilize new and external knowledges. We can commit to changing roles and create spaces within which historically marginalized communities can show us their know-how as a means of enhancing our own.

Exploring the Dynamics of Designers Who Co-Design With Artisans

The artisan sector is one of the contexts within which the binary relationship between designers and non-designers seems to be comfortably accepted by brand founders, designers, and consumers alike. “Designer” is a label typically reserved for people who have received knowledge and training of and about their particular design discipline in a formal, higher education setting—such as a college, university, or academy of art and design—who engage in creating visual communications artifacts and systems, products, environments, apparel, experiences, and more on behalf of paying clients or organizations who wish to use these outcomes of design processes to enhance the efficacy and efficiency of various aspects of their operations, or to generate or improve revenue streams, or to guide the development and implementation of new ways of making, doing, or thinking. This boundary between “designer” and “artisan” therefore runs along lines of socio-economic privilege, economic and political access, education, and socio-cultural class. In situations where they are mindful of their advantages, designers seem to be turning to the approaches and methods that guide the process of co-design as a means to facilitate more non-hierarchical and more equitable collaborations between themselves and those who do not possess their unique combination of skills and knowledge. Unfortunately, many co-design processes that transpire between professionally trained and educated designers and artisans often evolve according to an insistence on the part of the designer that he, she, or they has as much to contribute to the realization of a product or product line rooted in indigenously informed craft techniques as the indigenous artisan who possesses centuries-old knowledge and understandings of these. And sometimes—perhaps—the designers do possess some of this knowledge and these understandings, but these are of much less importance if the primary goal of a given co-design project is to sustain a dying craft or technique. This begs the following question: How might the design methodologies, and the methods that stem from them, that guide these types of co-design endeavors vary if the so-called “non-designers” (a.k.a. artisans) are instead accepted as “designers with other names” 25 (see Figure 5)?

In some cases, designers or brand founders have a clear idea of the wants and needs of a given group of consumers, as well as how to align these with a marketing strategy as they approach a particular artisan community to commission work from them. This often involves utilizing pre-established designs that are formally aligned with reports generated by trend forecasting companies, such as the Worth Global Style Network (WGSN). In these cases, as the authors have observed on several occasions, the creativity and mastery of the artisan tend not to be celebrated, recognized, or fostered. Instead, individual artisans or artisan-based communities receive a bag or bags that contain the exact materials, patterns, and dimensions of whatever it is that has been specified for production, and then they are told that they must follow and execute these plans and patterns exactly and with materials provided in order to receive payment. In other models, intermediaries who may or may not have design knowledge, or designers, first immerse themselves into a specific artisan-based community for a short time to attempt to understand at least some aspects of the richness of their culture, and then appropriate these as so-called “inspiration(s)” for a collection of goods or products without incorporating any critical input from the artisans, or yielding any benefits to them from the sales of the collection they helped inspire. Challenges inherent in this model arise especially when sacred, ancestral patterns and symbols are used to construct the formal core of a specific product or collection of them. Navigating the appropriate usage and incorporation (or adaptation) of these kinds of elements into this type of collection is a major ethical challenge for those from outside the cultures of indigenous artisans who wish to work with them, or to commission them, to produce broadly saleable goods and products.

The Colombian shoe and accessories brand, Wonder for People was able to effectively address this problem in their work with the indigenous Kamsá community, located in the Sibundoy Valley of the Putumayo Department in the southern portion of the country. As described directly to co-author Valentina Palacios by the brand’s co-founder, Maria Claudia Medina (who is not indigenous), Wonder for People was concerned about culturally mis-appropriating the community’s indigenous symbols into their lines of goods and products. To avoid this, the brand designer and one of the Kamsá tribe members co-designed a new set of symbols that could be used into some of the brands visuals. “Trazos” (which translates to “Strokes”), as both parties came to refer to this set of symbols, are based on the importance of tobacco to the Kamsá people and the healing power that they believe it has. Although some questions remain regarding the cultural heritage and authenticity of the Trazos (because they were used in goods and products by Wonder for People, though not necessarily ancestral in origin), this approach to an artisan and a brand designer engaging in the co-creation process is a positive example of working in ways that encourage and empower artisans to fulfill roles as creative practitioners rather than mere producers. This also allowed them to be celebrated as holders of important aspects of their community’s cultural knowledge and understandings.

If they are well-planned and well-facilitated, co-design approaches and processes can effectively expose artisans to and immerse them in new practices in ways that are beneficial to them. In this way, co-designing affords artisans and artisan-based communities to engage in activities that align with the more empowering and culturally celebratory descriptor “Designed By,” rather than the much less empowering and culturally dismissive “Made By.” 26 One optimal instance, which involved artisans being exposed to and then immersed in a new way of designing and then making in ways that allowed them to construct knowledge that they could incorporate into future work, occurred during 2021 in the Guajira area of far northern Colombia. A charitable foundation and several members of the Wayúu community who live there developed a collection of products for sale during the local Christmas season (which is celebrated in many major Colombian cities using products adorned with Western imagery of pine trees and lights, and with traditionally western European red-and-green color palettes). This design process that was planned and operated was undertaken in part to rescue a cord-making technique that was in the process of being forgotten within the artisan group, and then apply it to products that could be sold in a high-demand, local urban market (who purchased them for use as Christmas decorations). Today, the new ways of making cords that are based on utilizing older, indigenously informed techniques, has the potential to remain a part of the creative toolkit of the Wayúu artisans community for generations as it simultaneously fulfills a demand within the regional accessories market.

In addition to these small-scale commercial examples, the authors also see great potential and value in open-ended projects framed and facilitated as creative residencies which include contributions from artisans and artists or designers who are not necessarily part of a given artisan-based community. One such example is Oax-i-fornia, 27 which paired art and design students from the California College of the Arts (CCA) with artisans from Oaxaca, Mexico for brief yet intensive periods of collaboration. Over the span of several days, each artisan-student pair was tasked with co-creating something that was informed by an amalgam of their skills and accrued bases of knowledge, but was beyond the scope of either of their usual areas of practice. One example of this involved a product design student being paired with an indigenous textile weaver who worked together to jointly design and produce an outcome that incorporated both of their skill sets and sensibilities but that was neither solely a product nor a woven textile. The final exhibitions of these artifacts highlighted the results of knowledge and skill sharing that allowed for creativity and co-creation to be more important than attempting to satisfy market demands or trends. It’s no coincidence that this idea “incubator” was hosted within the relative safe ideological and practical space of the academy, where disconnection from commercially and socio-culturally imposed constraints is most possible.

In the end, designers need to be clear, and accountable, for their contributions and impact. If their goal is to foster tradition and cultural manifestations in and among artisan-based communities, they should strive to avoid causing artisans to engage in production methods that will detach them from those that are deeply rooted in and guided by their historical and cultural bases of knowledge. With this stated, it should also be understood that the ultimate goal of these endeavors should be to elevate and center the lives of artisans in ways that meet their needs and satisfy their aspirations, even if doing this means a loss of ancestral knowledge—after all, it is theirs to hold, share, and even relinquish.

Critically Examining How Artisan Brand Products Are Marketed and Sold

The typical designer-artisan project the authors have described thus far in this piece culminates in marketing and selling handmade products (or so-called intermediate goods, such as textiles) to typically urban and online marketplaces in major country capitals, as well as across the United States and Europe. Across our shared experiences, we’ve observed that this step is likely to be overseen by a designer/brand founder, and, in slightly larger organizations (those with more than ten employees), it often involves contributions from additional, specialized teams of people who may be responsible for overseeing logistical issues such as shipping and receiving, or devising, implementing, and analyzing marketing strategies, or managing payable and receivable accounts.

The authors have studied two general models. The first includes non-profit organizations such as Mercado Global, Global Goods Partners, and Nest, and entails a process whereby a large buyer is identified (such as, in the case of Mercado Global, the clothing company Levi’s, and the personal style company StitchFix) who orders a certain number of items made by artisans, with very high expectations regarding the quality level of whatever goods are produced. In this model, organizations enter into a work agreement with artisans with the intention of having them produce an array of goods intended for sale in a particular retail environment. The second includes smaller brands such as Wonder for People and Duka, which, at times, also represent a significant portion of a larger organizations’ business portfolio, and which operates a business model that facilitates direct sales to consumers. In this model, the brand often absorbs the expenses of buying inventory from artisans in the hope that it can be sold to individual consumers via transactions facilitated by their websites. 28

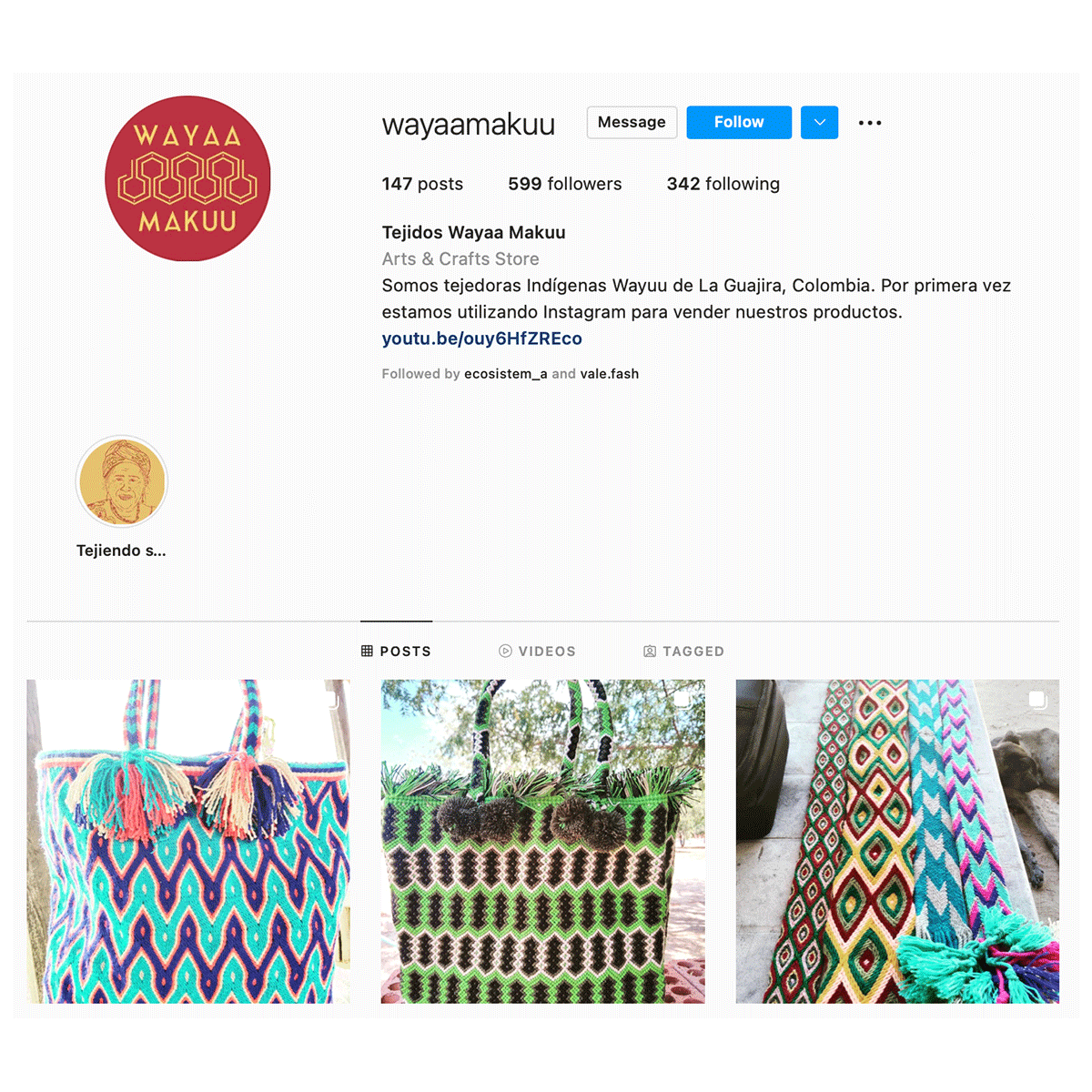

Instagram has become a central operational component of both of these types of marketing strategies. It has proved to be an excellent storytelling platform across which to articulate various aspects of the lives and livelihoods of many artisan communities, and, in so doing, it allows brands to showcase more than just the products they are attempting to sell: they can also depict who makes these products, as well as how and where they are made. As a result of this, many of these initiatives have started to incorporate workshops designed to familiarize artisan communities with the workings of the internet and some social media platforms. Unfortunately, there remain many examples of artisan groups who were not able to continue leveraging the technological access they were introduced to via this type of workshop-based training program. With that stated, the authors note that it is a welcome sign to begin to witness a rise in artisans’ direct participation in how content of and about them is contributed to and manipulated on social media platforms. Even though the goal of many of these endeavors may still be commerce-based, these models teach artisans skills they may one day be able to apply in a wide variety of future contexts. For example, early in the Covid-19 pandemic, designer and co-author of this piece Valentina Frías taught technology inclusion workshops to improve the staging and photographic skills of Wayúu artisans in La Guajira, Colombia. The goal was to teach them how to independently maintain an Instagram account that allowed them to author and post news about their community (see Figure 6). This account was transferred to them in February 2021, and the community has since been able to effectively apply what they learned.

While the artisan-run approach may feel more inclusive, there are certainly challenges reflective of the gaps in socio-cultural and economic understandings between many Western consumers and these communities of artisans who produce the artisan-based goods they consume. For example, as she operated marketing campaigns to promote a new collection of artisan-produced products she had launched, brand founder and co-author of this piece Valentina Palacios experienced greater sales conversion rates when using photos in which Western buyers could picture themselves in familiar settings sporting a specific artisan-produced product. This involved examples such as depicting a scene within which a handmade, artisan-produced product was modeled by someone on an urban street of a major metropolitan area in the U.S. or western Europe. This proved to be a more effective means of marketing these products than relying on visual communication strategies that emphasized depictions of artisans and/or the [often rural] contexts within which they worked. In instances such as this, the artisan and designer/brand founder will need to decide what is more important: increasing the sales of a line of artisan-made products or encouraging accurate depictions of artisan communities across social media accounts they control.

Additionally, once the decision is made to promote products from a given artisan-based brand on specific social media platforms, the brand owners and promoters need to be up front with consumers if representatives from that artisan-based community are not necessarily open for business 24/7, 29 and they need to be clear about how inquiries from prospective customers can be shared (via direct messages or otherwise). Since the immediacy and speed of social media do not necessarily align with the spatio-temporal frameworks of many artisan communities, the authors also encourage a shift in the thinking of consumers, who need to understand that their frequent calls to establish more sustainable and resilient supply chains are or will be causal factors in slower rates of production and shipping, which also correlate with slower communications and less frequently updated media presences. Based on their experiences working with artisan communities in Central and South America, the authors are also optimistic about the abilities of many artisan communities to operate made-to-order business and production models. These would entail artisans only beginning a given production schedule after they receive a credible and concretely financed order from a given consumer or brand owner, as all involved will have a clear understanding of how this schedule will evolve from the moment it is commenced until it is fulfilled.

Strategizing and Operating Ways Forward That Center Sustainable Artisan Livelihoods

Designers can and do play myriad roles across the artisan production sector, but for those among us who wish to work with artisans in ways that positively affect them, we must be willing to set aside the business-as-usual expectations of commercial projects (such as ensuring the maintenance of our normal project fee structures, client retention and exclusivity agreements, and ironclad, intellectual property rights protections). Instead, we must work toward facilitating more inclusive and equitable ways of working with artisans who do not enjoy the legal and economic protections that those of us who work in so-called developed nations take for granted. It is also high time to answer the multitude of calls for accountability in design practice 30 and leave the traditional, often exploitative role it has played in the history of designers who work with continually marginalized and impoverished artisans. Realizing and maintaining actual positive social, economic and, as far as it is possible, economic impact have become more important than merely expressing our good intentions if we’re serious about implementing and sustaining inclusive models of support, and fostering an artisan-centric sector within which the artisans wield as much power as the designers and other intermediaries with whom they collaborate.

Designers, educators, researchers, and scholars who have worked with and on behalf of artisan communities are familiar with the following scenarios: the individual artisan who shows up to the workshopearly on sunny days and late on rainy days, or the group that is unable to complete a particular work order on time because their socio-cultural tradition demands a month-long mourning for the passing of a loved one, or the buyer that is frustrated that the turnaround time for the production of a given array of goods will not transpire with Amazon-like speed. Yet, while many designers and industries are sourcing from handmade, craft-based, and artisanal makers as a response to urgent calls for environmental sustainability from many consumers around the world, designers and their clients need to cease imposing external frameworks on indigenous communities who—for centuries—have engaged in more people-and-planet-friendly ways of living and of making.

The processes described and contextualized in this article can serve as an initial template for allowing designers to evolve more equitable, mutually beneficial strategies for guiding their collaborations and agreements with artisans. (Whether marketing and sales enter into these, in small or large scales, will need to be determined on a case-by-case basis). The authors perceive great opportunities for designers who are willing to shift away from working modalities that entail them merely serving as conduits who facilitate order filling that call for directing artisan-made goods into specific markets toward working modalities that involve working with artisans as active listeners, facilitators, and collaborators. Instead of co-designing products in ways that call for artisans to work toward specifications with which we provide them, we invite designers and their clients to co-create an artisan-centric process that affords artisans to lead design processes strategically and tactically. Additionally, instead of continuing to insist on capitalist models for defining and providing the primary means for sustaining the livelihoods of artisans, we believe that designers should adopt the thinking articulated by anthropologist Arturo Escobar to effectively reimagine a way forward: “We cannot exit the crises with the categories of the world that created the crises (development, growth, markets, competitivity, individual, etc.).” 31 Operationalizing this approach will most likely not yield a hugely profitable and financially sustainable way forward, but it’s time we stop insisting that the existential problems that the artisan sector must confront to sustain itself can be solved through continuing to operate traditional business models.

Let’s welcome, learn from, and co-create new “categories of the world” to reclaim and re-invent these concepts in ways that can be used to guide and support artisans as they engage in new ways of planning and making that will hopefully challenge rather than perpetuate the inequities that limit their social, political, and economic opportunities. By doing this together, we can redefine, reframe, and actualize old and new ideas about knowledge, design, mastery, privilege, and power.

Notes

- MARC Group, “Handicrafts Market: Global Industry Trends, Share, Size, Growth, Opportunity and Forecast 2023-2028,” IMARC, 2022. Online. Available at: https://www.imarcgroup.com/handicrafts-market (Accessed March 25, 2023). ⮭

- Scrase, T. “Precarious production: globalisation and artisan labour in the Third World,” Third World Quarterly, 24.3 (2003): pgs. 449–461. ⮭

- Thomas, H. “Macy's Partners with Traditional Artisans to Help Rebuild Economy and Culture in Earthquake-Devastated Haiti,” Macy’s, 21 September 2010. Online. Available at: https://www.macysinc.com/news-media/press-releases/detail/979/macys-partners-with-traditional-artisans-to-help-rebuild. (Accessed March 25, 2023). ⮭

- Velasquez, A. “Levi’s Expands Partnership With Latin American Artisan Organization,” Rivet, Sourcing Journal, 13 December 2022. Online. Available at: https://sourcingjournal.com/denim/denim-brands/levis-expands-partnership-with-latin-american-artisan-organization-mercado-global-396420/ (Accessed March 25, 2023). ⮭

- Author unknown. “Contemporary Design Meets Traditional Craft,” IKEA, 20 March 2023. Online. Available at: https://www.ikea.com/us/en/new/contemporary-design-meets-traditional-craft-pub8fe0fc00. (Accessed March 25, 2023). ⮭

- Sydney, P., Nicole, s., and Bird, T. “On Purpose: Creating a New Manufacturing Partner,” in Global Economic Empowerment Report, ed. U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation, Washington D.C., USA, 16 December 2014. Online. Available at: https://www.uschamberfoundation.org/blog/post/kate-spade-co-working-artisanal-suppliers-and-increasing-revenue/42356 (Accessed March 25, 2023). ⮭

- Papanek, V. Design for the Real World: Human Ecology and Social Change. Chicago, IL, USA: Academy Chicago Publishers, 1984, and Eames, C. and Eames, R. “The Eames Report April 1958,” Design Issues 7.2 (1991): pgs. 63–75. ⮭

- Craft Revival Trust, Artesanías de Colombia S.A, and UNESCO. Designers Meet Artisans: A Practical Guide. New Delhi, India, Bogotá, Colombia and Paris, France: Craft Revival Trust, Artesanías de Colombia SA. and UNESCO, 2005: p. 4. ⮭

- Lawson, C. “‘Designed by’ versus ‘Made by’: Two Approaches to Design-Based Social Entrepreneurship,” The Journal of Design Strategies, 4.1 (2010): pgs. 34-40. ⮭

- Chappe, R. & Lawson Jaramillo, C., “Artisans and Designers: Seeking Fairness within Capitalism and the Gig Economy,” Dearq, 26 (2020): pgs. 80–87. ⮭

- Rosenbaum, B. “Forward,” in Artisans and Advocacy in the Global Market: Walking the Heart Path, ed. by Jeanne M. Simonelli, Katherine O'Donnell, and June C. Nash. Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA: Santa Fe: School for Advanced Research Press, 2015: p. xii. ⮭

- Lockwood, T. Design Thinking: Integrating Innovation, Customer Experience and Brand Value. New York, NY, USA: Allworth Press, 2010: p. xi. ⮭

- Sarah Jane Moore and Yulia Nesterova, “Indigenous Knowledges and Ways of Knowing For a Sustainable Living,” ed. UNESCO Futures of Education, Paris, 2020, https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374046. ⮭

- “Together, On Purpose,” Kate Spade, accessed March 20, 2023, https://www.katespade.com/social-impact/on-purpose. and Erica Martin, “Sustainable Hemp Products for a Cleaner Tomorrow,” Mosaic (blog), Ten Thousand Villages, January 19, 2022, https://mosaic.tenthousandvillages.com/sustainable-hemp-products-cleaner-tomorrow/. ⮭

- Beatrice Lorge Rogers and Kathy E. Macías, “Program Graduation and Exit Strategies: A Focus on Title II Food Aid Development Programs,” Washington, D.C.: Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project, Academy for Educational Development, November 2004. https://www.fantaproject.org/sites/default/files/resources/TN9-Exit-Strategies-Nov2004.pdf. ⮭

- “Guiding Principles,” Parsons DEED Lab at The New School, Accessed on March 23, 2023, https://deed.parsons.edu/guiding-principles/. ⮭

- Heather Vrana, “The Precious Seed of Christian Virtue: Charity, Disability, and Belonging in Guatemala, 1871–1947,” Hispanic American Historical Review 1 May 2021, 101 (2): 265–295, https://doi.org/10.1215/00182168-8897490. ⮭

- Nicole S. Berry, “Did We Do Good? NGOs, Conflicts of Interest and the Evaluation of Short-term Medical Missions in Sololá, Guatemala,” Social Science & Medicine, Volume 120, 2014, 344-351, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.05.006. ⮭

- Davalos, M. “Poverty & Equity Brief Colombia,” World Bank Group, 10 April, 2021. Online. Available at: https://databank.worldbank.org/data/download/poverty/987B9C90-CB9F-4D93-AE8C-750588BF00QA/AM2020/Global_POVEQ_COL.pdf. (Accessed April 14, 2023). ⮭

- “Información de Artesanías de Colombia S.A. para el Cuarto Reporte de Economía Naranja,” Artesanías de Colombia. Online. Available at: https://artesaniasdecolombia.com.co/Documentos/Contenido/37773_2020_-_informe_de_artesani%CC%81as_de_colombia_para_cuarto_reporte_naranja_2020_vf.pdf (Accessed April 26, 2022). ⮭

- Julio Enrique Soler B., “Globalisation, Poverty And Inequity,” Social Watch (blog), Soler B., J.E. “Globalisation, Poverty And Inequity.” Social Watch (blog), 28 September, 1997. Online. Available at: https://www.socialwatch.org/node/10587 (Accessed April 20, 2022). ⮭

- “Maestros Ancestrales – Club Colombia,” Club Colombia, 19 October, 2017, video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p3K053vehyM. (Accessed April 14, 2023). ⮭

- Author Unknown. “What is Asset Based Community Development (ABCD)?” Collaborative for Neighborhood Transformation, October 2019. Online. Available at: https://resources.depaul.edu/abcd-institute/resources/Document/WhatisAssetBasedCommunityDevelopment.pdf (Accessed April 20, 2022). ⮭

- Tunstall, E (Dori). “Decolonizing Design Innovation: Design Anthropology, Critical Anthropology, and Indigenous Knowledge.” In Design Anthropology, edited by Gunn W., Otto, T., Smith, R.C. London, UK: Routledge, 2013: pgs. 232–250. ⮭

- Calderón Salazar, P. & Gutiérrez Borrero, A. “Letters South of (Nordic) Design.” Nordes 2017: Design and Power, 7 (2017): pgs. 1-5. ⮭

- Lawson, C. “‘Designed by’ versus ‘Made by’: Two Approaches to Design-Based Social Entrepreneurship,” The Journal of Design Strategies, 4.1 (2010): pgs. 34-40. ⮭

- Cabra, R. “Oax-i-fornia: Generative Intersections and the Design of Craft.” Iridescent, 2.4 (2012): pgs. 15-31. ⮭

- “Case Studies.” Parsons DEED Lab at The New School, 2020. Online. Available at: https://deed.parsons.edu/projects/case-studies/. (Accessed on September 2, 2022). ⮭

- Bennett, M. “Why 24/7 business is the future.” The Telegraph: Business, 13 April 2022. Online. Available at: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/ready-and-enabled/the-future-of-24-7-business/ (Accessed March 25, 2023). ⮭

- von Busch, O. & Palmås, K. The Corruption of Co-Design: Political and Social Conflicts in Participatory Design Thinking, New York, NY, USA and London, UK: Routledge, 2023: p. 23; Aye G., “Design Education’s Big Gap: Understanding the Role of Power,” Greater Good Studio (blog), Medium, 2 June 2017, https://medium.com/greater-good-studio/design-educations-big-gap-understanding-the-role-of-power-1ee1756b7f08 (Accessed March 25, 2023). ⮭

- Escobar, A. Otro posible es posible: Caminando hacia las transiciones desde Abya Yala/Afro/Latino-América. Bogotá, Colombia: Ediciones Desde Abajo, 2018 ⮭

- ⮭

- ⮭

- ⮭

- ⮭

- ⮭

References

Artesanías de Colombia. “Información de Artesanías de Colombia S.A. para el Cuarto Reporte de Economía Naranja.” Online. Available at: https://artesaniasdecolombia.com.co/Documentos/Contenido/37773_2020_-_informe_de_artesani%CC%81as_de_colombia_para_cuarto_reporte_naranja_2020_vf.pdf. (Accessed April 26, 2022).

Author Unknown. “Maestros Ancestrales–Club Colombia.” Club Colombia, 19 October, 2017. Video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p3K053vehyM (Accessed March 25, 2023).

Author Unknown. “What is Asset Based Community Development (ABCD)?” Collaborative for Neighborhood Transformation, October 2019. Online. Available at: https://resources.depaul.edu/abcd-institute/resources/Documents/WhatisAssetBasedCommunityDevelopment.pdf (Accessed April 20, 2022).

Aye, G. “Design Education’s Big Gap: Understanding the Role of Power.” Greater Good Studio (blog). Medium. 2 June 2017. Online. Available at: https://medium.com/greater-good-studio/design-educations-big-gap-understanding-the-role-of-power-1ee1756b7f08 (Accessed March 25, 2023).

Bennett, M. “Why 24/7 business is the future.” The Telegraph: Business, 13 April 2022. Online. Available at: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/ready-and-enabled/the-future-of-24-7-business/ (Accessed March 25, 2023).

Berry, N. S. “Did We Do Good? NGOs, Conflicts of Interest and the Evaluation of Short-term Medical Missions in Sololá, Guatemala.” Social Science & Medicine. 120, (2014): pgs: 344–351. Online. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0277953614002937?via%3Dihub (Accessed March 25, 2023).

Cabra, R. “Oax-i-fornia: Generative Intersections and the Design of Craft.” Iridescent, 2.4 (2012).

Calderón Salazar, P. & Gutiérrez Borrero, A., “Letters South of (Nordic) Design.” Nordes 2017: Design and Power, 7 (2017).

Chappe, R. & Lawson Jaramillo C., “Artisans and Designers: Seeking Fairness within Capitalism and the Gig Economy,” Dearq, 26 (2020).

Craft Revival Trust, Artesanías de Colombia S.A, and UNESCO. Designers Meet Artisans: A Practical Guide. New Delhi, India, Bogotá, Colombia and Paris, France: Craft Revival Trust, Artesanías de Colombia SA. and UNESCO, 2005.

Davalos, M. “Poverty & Equity Brief Colombia,” World Bank Group, 10 April, 2021. Online. Available at: https://databank.worldbank.org/data/download/poverty/987B9C90-CB9F-4D93-AE8C-750588BF00QA/AM2020/Global_POVEQ_COL.pdf. (Accessed April 14, 2023).

Eames, C., & Eames, R. “The Eames Report April 1958.” Design Issues, 7.2 (1991): pgs. 63–75.

Escobar, A. Otro posible es posible: Caminando hacia las transiciones desde Abya Yala/Afro/Latino-América. Bogotá, Colombia: Ediciones Desde Abajo, 2018.

IKEA. “Contemporary Design Meets Traditional Craft.” A video. Online. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p3pxL-Tx0X4 (Accessed on March 20, 2023).

IMARC Group, Handicrafts Market: Global Industry Trends, Share, Size, Growth, Opportunity and Forecast 2023-2028, 8 July, 2022. Online. Available at: https://www.imarcgroup.com/handicrafts-market (Accessed April 6, 2023).

Author Unknown. “Together, On Purpose.” Kate Spade, March 2023. Online. Available at: https://www.katespade.com/social-impact/on-purpose (Accessed March 25, 2023).

Lawson, C. “‘Designed by’ versus ‘Made by’: Two Approaches to Design-Based Social Entrepreneurship,” The Journal of Design Strategies, 4.1 (2010).

Lockwood, T. Design Thinking: Integrating Innovation, Customer Experience and Brand Value. New York, NY, USA: Allworth Press, 2010.

Macy’s. “Macy's Partners with Traditional Artisans to Help Rebuild Economy and Culture in Earthquake-Devastated Haiti.” 21 September, 2010. Online. Available at: https://www.macysinc.com/news-media/press-releases/detail/979/macys-partners-with-traditional-artisans-to-help-rebuild (Accessed April 6, 2023).

Martin, E. “Sustainable Hemp Products for a Cleaner Tomorrow.” Mosaic (blog). Ten Thousand Villages, 19 January, 2022. Online. Available at: https://mosaic.tenthousandvillages.com/sustainable-hemp-products-cleaner-tomorrow/ (Accessed April 6, 2023).

Moore, S. J. & Nesterova, Y. “Indigenous Knowledges and Ways of Knowing For a Sustainable Living.” Edited by UNESCO Futures of Education, Paris France, August 18, 2020. Online. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374046. (Accessed April 14, 2023).

Oxford University Press. Oxford Learner’s Dictionary. Oxford, UK. Continuously updated. Online. Available at: https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/us/definition/english/artisan_1 (Accessed March 25, 2023).

Papanek, V. Design for the Real World: Human Ecology and Social Change. Chicago, IL, USA: Academy Chicago Publishers, 1984.

Parsons DEED Lab at The New School. “Case Studies.” Parsons School for Design, The New School, 2020. Online. Available at: https://deed.parsons.edu/projects/case-studies/. (Accessed on September 2, 2022).

Parsons DEED Lab at The New School. “Guiding Principles.” Parsons School for Design, The New School, Online. Available at: https://deed.parsons.edu/guiding-principles/ (Accessed on March 23, 2023).

Price, S., Nicole S., & Bird, T. “on purpose: Creating a New Manufacturing Partner.” In Global Economic Empowerment Report, edited by U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation, Washington D.C., USA 2014. Online. Available at: https://www.uschamberfoundation.org/blog/post/kate-spade-co-working-artisanal-suppliers-and-increasing-revenue/42356 (Accessed March 25, 2023).

Rogers, Beatrice Lorge, and Kathy E. Macías. “Program Graduation and Exit Strategies: A Focus on Title II Food Aid Development Programs.” Washington, D.C.: Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project, Academy for Educational Development, November 2004. Online. Available at: https://www.fantaproject.org/sites/default/files/resources/TN9-Exit-Strategies-Nov2004.pdf (Accessed March 25, 2023).

Rosenbaum, B. “Forward,” in Artisans and Advocacy in the Global Market: Walking the Heart Path, edited by Simonelli, J.M., O'Donnell, K. & Nash, J.C. Santa Fe, NM, USA: School for Advanced Research Press, 2015: p. xii.

Scrase, T. J. “Precarious production: globalisation and artisan labour in the Third World.” Third World Quarterly. 24.3 (2003): pgs. 449–461.

Soler B., J.E. “Globalisation, Poverty And Inequity.” Social Watch (blog), 28 September, 1997. Online. Available at: https://www.socialwatch.org/node/10587 (Accessed April 20, 2022).

Thomas, H. “Macy's Partners with Traditional Artisans to Help Rebuild Economy and Culture in Earthquake-Devastated Haiti,” Macy’s, 21 September 2010. Online. Available at: https://www.macysinc.com/news-media/press-releases/detail/979/macys-partners-with-traditional-artisans-to-help-rebuild. (Accessed March 25, 2023).

Tunstall, E (Dori). “Decolonizing Design Innovation: Design Anthropology, Critical Anthropology, and Indigenous Knowledge.” In Design Anthropology, edited by Gunn W., Otto, T., Smith, R.C. London, UK: Routledge, 2013.

Velasquez, A. “Levi’s Expands Partnership With Latin American Artisan Organization.” Sourcing Journal: Rivet, 13 December 2022. Online. Available at: https://sourcingjournal.com/denim/denim-brands/levis-expands-partnership-with-latin-american-artisan-organization-mercado-global-396420/ (Accessed March 25, 2023).

von Busch, O. & Palmås, K. The Corruption of Co-Design: Political and Social Conflicts in Participatory Design Thinking. New York, New York, USA and London, UK: Routledge, 2023.

Vrana, H. “The Precious Seed of Christian Virtue: Charity, Disability, and Belonging in Guatemala, 1871–1947.” Hispanic American Historical Review, 1 May 2021, 101.2: pgs. 265–295. Online. Available at: https://read.dukeupress.edu/hahr/article-abstract/101/2/265/173222/The-Precious-Seed-of-Christian-Virtue-Charity?redirectedFrom=fulltext (Accessed March 25, 2023).

Biography

Valentina Frías is a Colombian fashion and textile designer with a bachelor’s degree from Universidad de los Andes in Bogotá, Colombia. Her interests lie in examining and advocating for creative processes that are rooted in the expression of authentic cultural heritages made manifest using traditional craft techniques and analog media. She has served as a consultant for Fundación ACDI/VOCA LA since 2020, where she is currently part of a women’s artisanal project in La Guajira, Colombia. (Fundación ACDI/VOCA LA works to transform environments and create opportunities for effective inclusion, based on programs that generate social and environmental value that contribute to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.)

Additionally, Valentina is developing her auto-ethnographic project called Memorabilia, which includes a wearable, textile archive of memories that have been expressed by her crafting of discarded materials. The main objective of her work is to create an amalgam between art direction, craftsmanship, community design, and the preservation of ancestral memory in Colombia. ma.valentinafrias@gmail.com

Cynthia Lawson Jaramillo is a Brooklyn-based Colombian artist, technologist, and educator. At Parsons School of Design in New York, New York, U.S.A., she is the Dean of the School of Design Strategies and a Professor of Integrated Design. An internationally exhibited artist, her current research focuses on social design, community engagement, and the artisan sector via the DEED (Development through Empowerment, Entrepreneurship, and Design) Lab, which she co-founded in 2007 and currently directs. She is an active member of the design education networks of AIGA and the Future of Design in Higher Education, and a co-organizer of the annual conference Digitally Engaged Learning. Cynthia earned her B.S. in Electrical Engineering from Universidad de los Andes in Bogotá, Colombia, and a Master of Professional Studies (MPS) in Interactive Telecommunications from New York University’s ITP (Interactive Telecommunications Program). She can be reached via email at: cynthia@newschool.edu

Valentina Palacios is an MS (Master of Science) Candidate enrolled in the Strategic Design & Management program at Parsons School of Design in New York, New York, U.S.A., and a Research Fellow of the DEED (Development through Empowerment, Entrepreneurship, and Design) Lab. Previously, Valentina founded Fe Handbags—a Colombia-based social enterprise that worked in partnership with indigenous communities to create luxury handbags and accessories that incorporated ancient, indigenous art. The mission of the organization was to empower marginalized indigenous women by helping them to achieve financial independence while breaking the cycle of poverty for these artisans and their children. Part of what inspired Valentina to create her company was her desire to showcase the beauty and depth inherent in Colombian culture to people living around the world. She has confidence in the power that individual actions can have to initiate and sustain positive social, cultural, and economic change, and that these can help many of the world’s peoples to evolve into living within more inclusive and equitable societies. She can be reached via email at: palav293@newschool.edu