Tell us what you want to express so that more people will understand what you want.

—Wen Hui, Dance with Farmworkers (2001)

Have I become an artist?

Do I have anything that deserves appreciation?

—Zhao Xiaoyong, China’s Van Goghs (2015)

Prologue

In cinema’s mythology, the contraposition between the Lumière brothers’ cinema of the real and George Méliès’s cinema of illusion has set the stage for the ontological tension between reality and imagination in film practices, histories, and theories. Documentary storytelling has been traditionally linked to the former and has played a major role, especially in giving visibility to the reality of marginalized groups. In China, independent documentary “has long been associated with the production of images of the subaltern,”1 and subaltern struggles and agency have been a focus of many documentary films.2 What happens when the reality that the documentary seeks to capture is that of subaltern creativity? How has documentary (re)presented its imaginative quality? The answer is a transnational, transmedia story that develops from China’s “cool cities” and expands in the virtual space of global digital media, in which the creative subaltern plays multiple, intersecting, and conflicting roles: the (subordinate) performer, the (self-determined) author, and the (aspiring) artist.

No Film Can Be Too Personal

In “Get Out and Push!,” Lindsay Anderson sought to reconnect (political) resistance and (personal) creativity. He criticized those for whom “art remains a diversion or an aesthetic experience,” reclaiming creativity as essential to documentary filmmaking.3 While committed to social observation and critique, he advocated for the freedom to express one’s subjective impressions and emotions about reality:

A socialism that cannot express itself in emotional, human, poetic terms is one that will never capture the imagination of the people—who are poets even if they don’t know it. And conversely, artists and intellectuals who despise the people, imagine themselves superior to them, and think it clever to talk about the “Ad-Mass,” are both cutting themselves off from necessary experience, and shirking their responsibilities.4

Anderson put this view into practice, becoming a leading filmmaker in the Free Cinema Movement.5 This short-lived but influential movement is known for “six programmes of (mainly) short documentaries shown at the National Film Theatre (NFT) in London” between 1956 and 1959. Produced outside the film industry, in semiamateur conditions, the films “avoided or limited the use of didactic voice-over commentary, shunned narrative continuity and used sound and editing impressionistically.”6 In the movement’s manifesto, the filmmakers declare:

These films were not made together; nor with the idea of showing them together. But when they came together, we felt they had an attitude in common. Implicit in this attitude is a belief in freedom, in the importance of people and the significance of the everyday.

As filmmakers we believe that

No film can be too personal.

The image speaks. Sound amplifies and comments.

Size is irrelevant. Perfection is not an aim.

An attitude means a style. A style means an attitude.7

Predating the development of postcolonial and subaltern studies, when leftist intellectual elites were beginning to debate their position vis-à-vis mass culture and mass media, Free Cinema aspired to extricate individual subjectivity from the “mass” and “capture the imagination of the people,” relying on personal perspectives while making a political intervention.

Taking Free Cinema as a departure point and postsocialist, globalizing China as its context, this study examines how “the imagination of the people” is captured on screens and, more specifically, its entanglement with elitist definitions of creativity, the representation of subaltern reality, the expression of subjectivity, and the tension between the political and the personal. In China, documentary has played an important albeit ambiguous role—provocative and empowering but also, at times, formulaic and constricting—in shaping discourse on the subaltern (more precisely, in the Chinese context, nong min gong [rural migrant worker] or dagong [working-for-the-boss, hired-hand worker]) as a creative subject. Documentary is one of the expressive forms explored in subaltern creative practices, and it has become a privileged medium for their representation and interpretation. While documentary narratives by and about the creative subaltern have made subaltern creativity visible and contributed to the emergence of subaltern celebrities, they have also devalued subaltern authorship and cast doubt on the artistic significance of subaltern creative works.

Over the past twenty years, the Chinese subaltern has taken advantage of the availability of new Digital Video (DV) technology to create documentary videos, reclaiming control over their life stories and their creative practices.8 Online platforms and social media have expanded their viewership. In 2005, the observational-style and interview-format documentaries focusing on village life produced by the apprentice amateur filmmakers participating in the China Village Documentary Project only reached limited, specialized audiences. Today, Li Ziqi’s documentary videos celebrating idyllic life and traditional cooking and crafts in rural Sichuan total 1.6 billion views. Yet, rather than a creative subject, Li is largely considered a DIY “food celebrity.”9

In addition, nonsubaltern creative practitioners (i.e., educated urbanites with backgrounds in filmmaking, visual arts, academia, or journalism) have sought to make subaltern creative practices and aspirations visible, often advocating for solidarity with their struggles. In these documentary narratives, the creative subaltern is framed in transformative stories that record and dramatize life journeys. However, such documentary storytelling often amplifies creativity’s indexicality to the real and obfuscates its imaginative quality and ambition of breaking free from the real, thus entrapping creativity in the very subaltern condition it seeks to overcome.

By reflecting on Free Cinema’s advocacy for a subjective, personal approach to capturing the “imagination of the people,” I propose that other forms of documentary expressivity—such as poetic, non-plot-driven, narratives—offer alternative, more appropriate means of capturing the complexity, heterogeneity, and contradictoriness of the subaltern condition in order for subaltern creativity to be expressed, appreciated, and affirmed.

I begin by contextualizing the discourse on creativity and subalternity as being inescapably connected with urbanization and the “cool city.”10 China has embraced this “alignment of creativity with the cool, sophisticated and metropolitan,” which has led to valuing creativity in terms of “its capacity to make profits and conforms to the entrepreneurial imperatives of city managers, reinforcing the strategic role of creative industries in economic development and urban renewal.”11 Therefore, in the Chinese context, as elsewhere, subaltern creativity develops within and in conflict with the economic drive, intellectual elitarianism, technological prominence, and class bias that characterize cool cities.

Defining Creativity: The Cool City and Four-C Model

Creativity has become a marker of urban modernity and postmodernity. Scholars have documented, evaluated, and theorized online creative practices in popular cultures, such as DIY, amateur digital writers, photographers, animators, and video makers. Rather than defining creativity as having intrinsic qualities, media and cultural studies have focused on how (i.e., through which medium, when and where, for which purpose) creativity develops. Building on notions of active audience and expanding to vernacular creativity in the context of new and spreadable media, creativity is considered a highly contextualized practice, which includes the creative expressions of participatory cultures, media social activism, and transmedia and digital storytelling.12 Understanding creativity means analyzing texts in their context and unpacking their construction of meanings and power relations.

Creativity has also been mapped, categorized, and indexed as a tangible and measurable factor in the context of creative industries and economic development. Economist and urban studies scholar Richard Florida argues that “the key to economic growth lies not just in the ability to attract the creative class, but to translate that underlying advantage into creative economic outcomes in the form of new ideas, new high-tech businesses and regional growth.”13 He has developed a “creativity index” based on measurable categories, such as the creative class’s share in the workforce and the diversity factor.14

In the Chinese context, creativity is seen as supporting and in tension with the state’s interest in cultural economy as a key source for financial gain, national branding, and soft power.15 Creativity is identified as an expression of a technologically literate urbanite culture, associated with a mobile middle class, often with transnational or diasporic identities, and situated in cosmopolitan cities such as Shanghai.16 Scholars have concentrated on creative labor, defined by “contemporary industrial processes of cultural production, including media, design and arts.”17 Yiu Fai Chow has moved beyond “concerns with employment situations and place attractiveness,” demonstrating that “creative class mobility” results from complex dynamics involving gender, age, and social and personal contingencies.18 Critical of Florida’s “optimistic rhetoric,” “utopian vision,” and “upbeat understanding of the creative class,” Chow leaves aside the conceptual debate on the academic “creative turn,” advocating instead for “more qualitative and empirical work on the people operating in these sites of cultural production.”19 While focusing on technologically literate urbanite culture, Jian Lin and Chow caution against the celebratory, romanticized view of the prosperous, creative cool city, enriched by and welcoming of skilled creative practitioners.

Even more critical of the cool city’s optimistic rhetoric are scholars who have examined the creative practices of those earning lower incomes and/ or living on the margins of urban space, separated from cities by geographical distance or displaced within them. Human geographers Tim Edensor and Steve Millington “welcome the rejection of creativity as intrinsically economic, urban and singularly individualistic” and “anticipate that elitist, class-ridden definitions will be more widely rejected, recognised as signifying banal efforts to acquire cultural capital and status, and the protean nature of creativity will become ever more apparent.”20

Yet such “elitist, class-ridden definitions” often remain unchallenged and are still used to describe and qualify creativity. In an influential article, James Kaufman and Ronald Beghetto address the distinction between minor, ordinary creativity (“little-c”) and major, extraordinary creativity (“Big-C”) and propose a four-step approach to creativity, a “Four-C model” that identifies two additional categories: protocreativity (“mini-c”) and professional creativity (“Pro-c”).21

What interests me are the premises upon which these steps are identified. With the exception of mini-c, these premises rely on the acquisition of “cultural capital and status” as an objective measure in assigning c/C status. For instance, when referring to the highest level of creativity, defined by “greatness” and “legend,” the authors explain: “Examples of Big-C creativity might be winners of the Pulitzer Prize … or people who have entries in the Encyclopaedia Britannica longer than 100 sentences.”22

If we transfer these markers to digital cultures, evidence of Big-C status may include a lengthy Wikipedia page or other measurable factors, such as Li Ziqi’s twelve million subscribers and 1.6 billion views. However, the absence of prestigious awards and posthumous recognition (listed as evidence of Big-C creativity) may assign Li’s creativity little-c status. Furthermore, because professionalism (Pro-c) is shown as a necessary step to achieving Big-C, this model privileges accredited institutions and creative industries as means to develop creative talent and acquire Professionalism (capital P), making those who have no access, no resources, or no time to gain professional training (e.g., subaltern artists) incompatible with Pro-c and Big-C.

The assumptions and assertions the model makes about creativity show how widespread and ingrained highbrow cultural biases and socioeconomic hierarchies are. These biases and hierarchies are central to my examination of Chinese subaltern creativity and its expression, representation, and interpretation in documentary filmmaking. I share Edenson and Millington’s concerns and support their call for a more inclusive appreciation of creativity, beyond the cool city, and/or its value in terms of economic growth, cultural industries policies, and global flows. However, creativity remains constrained by “elitist, class-ridden definitions”: the cultural economy is viewed as a source for financial gain, national branding, and soft power, and, as reflected in the Four-C model, creativity is associated with “cultural capital and status.” In China, creativity’s position within and outside the cool city is further complicated by the Chinese discourse on subalternity.

Globalizing China: The Subaltern as a Creative Subject

In the Chinese context, subalternity is entangled with rural-to-urban migration, social displacement, and conflicting cultural belonging. As Sun Wanning observes,

The migrant worker exists in the contested and fraught space between the government’s propaganda, market driven urban tales inundating the popular culture sector, the so-called independent, alternative, or underground documentaries on the transnational art circuits, and various forms of cultural activism engaged in by NGO workers and their intellectual allies.23

Navigating this “contested and fraught space” means understanding the limitations and contradictions involved in all these players’ perspectives and agendas and recognizing that subaltern perspectives and agendas are similarly multiple and diverse. Scholars have unpacked the unjust, exploitative, degrading, and destructive conditions of those living at the bottom of social and economic hierarchies.24 They have recognized degrees of agency, identifying the “weapons of the weak” and the strategies through which they survive, negotiate, fight against, and break through the system that crushes and tries to silence their labor and human rights.25

An emerging “activist sinology” has expanded academic discourse on subalternity, relying on open-access digital platforms and engaging with civil society.26 For example, Made in China Journal, a quarterly “on Chinese labour and civil society,” seeks “to bridge the gap” between scholars and the public and believes open access reappropriates research from publishers “who restrict the free circulation of ideas.”27 Located outside academia and aiming to hold the official trade union “accountable to its members,” the China Labour Bulletin, a nongovernmental organization (NGO) based in Hong Kong, is committed to fostering “lasting international solidarity.”28

The creative practices of worker-performers, worker-poets, worker-painters, and worker-filmmakers are “entangled” with this contested, fraught space of subalternity, where they live, work, and create.29 Sun pioneered the investigation of migrant workers’ creativity in printed and screen media.30 Maghiel van Crevel’s research on worker-poets in relation to ownership and translatability and Gong Haomin’s examination of ecopoetics in dagong poetry have disentangled the constraints that limit the reach and appreciation of subaltern literary works.31 Focusing on worker-painters, Winnie Wong’s study of Shenzhen’s Dafen Village painters exposes porous dichotomies and belongings, deconstructing clichés, unpacking assumptions about “mindless imitation” or “mechanical techniques,” and pointing out that the painters “understand themselves as both dagong workers and independent artists.”32

Alongside traditional arts, digital video and online media have become venues for the Chinese subaltern to communicate “aspirations,” “frustrations,” and “activist ethos and imaginary,” although “the extent to which migrant individuals can be empowered by this visual and technological means of expressing oneself is unclear.”33 Being creative allows for self-expression but not necessarily self-emancipation. Ngai-Ling Sum examines the multiplicity and fragmentation of working-class groups, focusing on how young migrant workers explore the tension between self-expression and self-emancipation online, via memes, texts, and photos centered on diaosi (loser) identity, which, he argues, reflects a subaltern “contradictory consciousness.”34

In the context of digital video and online media, Chinese news media has covered the growing phenomenon of subaltern performers going viral, often celebrating their talent and success as evidence of the fulfilled promises of the China dream and in support of national strength and unity. For instance, Chinese- and English-language news reported on Peng Xiaoying and her husband, two corn growers in Wenzhou, who invented dance steps that “cheered up millions of Chinese netizens who salute the couple’s smiling faces and their easygoing approach to life.”35 The China Daily co-opted the state’s agenda of nation building and soft power in its story on Ma Ruifeng, a farmer-hua’er singer who livestreams performances, quoting him: “Life can be difficult, but the support and understanding from family can keep us going. As long as you work hard, things will get better.”36 It pointed out, “The regional government spends 600,000 yuan ($86,000) every year on teaching and performing centers for the folk music,” protecting and promoting it and subsidizing “over 40 inheritors of the tradition across Ningxia, including Ma.”

Within this broad spectrum of traditional and digital arts and media, documentary filmmaking has emerged as a singularly suitable text and metatext for subaltern creativity.

The Creative Subaltern as the Performer: Oblique Incursions

Subaltern creativity has been represented obliquely in documentary filmmaking and in fiction films with a strong indexicality to the real, which are often described as having a documentary style, such as the works of the Sixth Generation filmmakers.37 By obliquely, I mean that, in these films, the subaltern’s desire and ability to be creative are not the main foci of the narrative. Rather, they are either subordinated to it or become “accidently” visible. This is what happens, for example, when Ruijuan dances alone in her office at night (Platform, directed by Jia Zhangke, 2000) or when a dreamlike animation visualizes Tao’s interior life (The World, directed by Jia Zhangke, 2004). The grey, still environment of subaltern reality is transformed temporarily in lyric scenes, filled with color, music, movement, and imagination. These scenes briefly rupture the main narrative; creativity and imagination are presented as fleeting moments before the crude reality of subaltern life resumes.

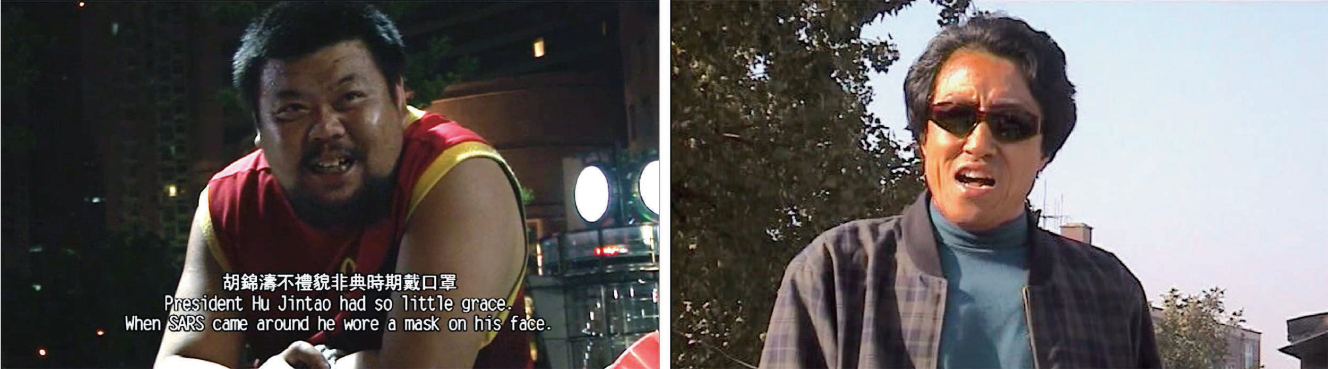

Oblique incursions of creativity in subaltern lives also occur in early independent documentary filmmaking. The films record the humorous “rapping” improvised by Da Pangzi (Big Fatty), one of the trash collectors in Street Life (Nanjing lu 南京路, directed by Zhao Dayong, 2006), or the self-staged clips of citizen activist Zhang Jinli in Meishi Street (Meishi jie 煤市街, directed by Ou Ning, 2006) who takes over the camera and confidently acts as a singer and martial arts performer. In both cases, these creative performances are temporary ruptures in documentary narratives that focus on the subaltern’s everyday struggle to survive (Street Life) or seek justice and compensation for the loss of their homes (Meishi Street) (see figure 1).

Besides these accidental incursions, the subaltern as a creative subject has been a prominent theme in documentary-style art videos produced in the context of contemporary avant-garde participatory art and performance. For instance, multimedia artist Cao Fei’s Whose Utopia? (Sheide wutuobang 谁的乌托邦, 2006) recorded workers’ daily lives at the Osram lighting factory, interviewing them and then involving them in performances. One video summary describes how “anonymous figures dance and play music” and how Cao’s “poetic, dreamlike vision of individualism within the constraints of industrialization illuminates the otherwise invisible emotions, desires, and dreams that permeate the lives of an entire populace in contemporary Chinese society.”38 According to Chris Berry, the video provocatively reflects contemporary Chinese urbanization and reenchants the metropolis.39 Exemplifying participatory art’s aim “to demystify art, removing the idea of the individual genius and reclaiming it as a social process shared by all,” Cao’s project places herself (the artist) and the workers in the same creative space, in order to “maximize reflection that is open-ended and not structured by an agenda.” The subaltern’s creative desires and capabilities are central foci of the video narrative, and Cao notes how the workers communicated to her their realization that “art is life itself ” and that “we are all artists.”40 Yet the expression of their creativity remains oblique, as it is still subordinated to the educated, urbanite artist who, despite a genuine commitment to collaborate with and empower the workers, retains full control and authorship of the project.

One of the earliest examples of the contested, fraught relationship between the professional Artist (capital A, considered as having Big-C status) and the untrained creative subaltern is Dance with Farmworkers (He mingong tiaowu 和民工跳舞, directed by Wu Wenguang, 1999). The film documents the lead-up to the performance of ten actor-dancers from China’s Living Dance Studio (led by Wen Hui, Song Dong, Yin Xiuzhen, and Wu Wenguang) and thirty migrants working in construction in Beijing. When it was released, mostly reaching academic and art circles in China and abroad, the documentary was praised as a bold, unconventional project that empowered the laborers, who originally “were only concerned about getting paid 30 Yuan a day for their efforts” but, thanks to this creative experience, then discovered that “the lowest of ‘the lower class’ could be standing at center stage and making a statement.”41 In contrast to this positive appraisal, Wen Hui and Wu Wenguang have been criticized for co-opting the workers in a live performance and media event while remaining in full control of authorship and being the only ones “standing at center stage and making a statement.” For instance, Miao Fangfei critiques the “objectification of farm workers,” who “function as bodies, not subjects,” and questions the unaddressed tension between the workers’ subaltern condition and “social elites” to which the producers and audiences belong42:

Chinese farm workers, although participating in the creation of the performance and the film, rarely receive a seat among the audiences. The elites … speak to themselves about the working class, and the working class functions as a topic in that conversation. Wen Hui and Wu Wenguang speak to other intellectuals and elites using their shared language—dance and documentary film. By so doing, they marginalize and objectify Chinese farm workers.43

In 1999, Wu Wenguang also produced a documentary entirely focused on subaltern performers. Jiang Hu: Life on the Road ( Jiang hu 江湖, aka Life on the “Jianghu” ) follows the Yuanda Song and Dance Tent Show, a troupe from the rural Henan province. In this case, subaltern creativity is given full agency: performing is their livelihood and members control their show, although their performances are represented obliquely, subordinated to the main narrative focusing on their itinerant life and the struggles they experience when, as migrant workers, they face the city’s hostility.

Twenty years on, the creative subaltern continues to be represented on-screen as marginalized by an increasingly wrecked urban modernity. Traditional artists have a higher artistic status than the karaoke singers in Jiang Hu, but their fate is not much different. Johnny Ma’s To Live to Sing (Huozhe changzhe 活著唱著, 2019) tells the story of the Jinli Sichuan Opera Troupe on the outskirts of Chengdu, centering on manager Zhao Li and her attempts to save the troupe from its inexorable decline. A real-life opera performer, Zhao Xiaoli plays the lead role, giving the film a quasidocumentary quality. Although not strictly a documentary film, To Live to Sing follows in the footsteps of the Sixth Generation’s urban realism and echoes Jia Zhangke’s surrealist ruptures by combining a documentary-style narrative with “dreamy, fantastical sequences” that make us “step into another world.”44

This overview shows how incursions of subaltern creativity in documentary filmmaking have reflected broader tensions between authenticity and subjectivity, realist and fictionalized narratives. Subaltern creativity has been captured as having an extemporaneous or amateur quality, vicariously and critically intervening in the city’s modernity, albeit only thanks to the mediation of intellectual elites (as in Dance with Farmworkers or Whose Utopia?). Alternatively, subaltern creativity has been identified as an unappreciated professionalism (as in Jiang Hu or To Live to Sing), at odds with the city that marginalizes and rejects it.

In all these incursions, even when subaltern talent and agency is visible and recognized in the audiovisual text, the subaltern is largely absent in the processes of circulation and reception. Even though filmmakers have become more aware of the ethical issues involved in producing documentary narratives about the subaltern, the questions, Can the subaltern speak through the lens of a camera? and, Can subaltern creativity be expressed through the lens of a camera? can only be answered affirmatively if accompanied by caveats and critical scrutiny about the filmmakers (i.e., those who are behind the camera), whose agency determines the content of the audiovisual narrative and impacts on its circulation, distribution, and reception.45 What happens when the creative subaltern takes control of the creative process and reclaims authorship?

The Creative Subaltern as the Author: Is a “Googleable Name” a Marker of Authorship?

In documentary videos produced by the subaltern, oppression, resistance, and solidarity remain key themes and motivations, but they are expanded, complicated, and pushed to the background in order to foreground the need for self-expression and self-representation.

Among the earliest attempts to give creative rights to the subaltern was Wu Wenguang’s Village Video Project (Cunmin yingxiang jihua 村民影像计划, 2006), in which a group of villagers individually produced a ten-minute documentary on experiments with local governance. While the project aimed to empower the villagers and provide them with the means to produce and circulate their videos, unresolved tension existed between the global, recognizable artist and the local, anonymous subaltern. The video makers’ names are listed at the beginning of each video, but only the name of the overarching architect—Wu Wenguang—is credited for the project’s authorship.

More recently, online platforms and social media offer more direct channels for self-expression and self-representation. In a complex process of alliances with and distancing from prominent intellectuals and artists with links to transnational and global audiences and established domestic channels that promote creative practices in the cool city, the creative subaltern has turned to the Internet to reclaim direct and independent authorship.

In March 2007, Zhou Shuguang 周曙光 (nom-de-blog Zuola 佐拉, aka “Zola”) made a name for himself when, “driven by [his] sensitivity to news and [his] designs to become famous overnight,” he went to Chongqing to report on the “nail house incident.”46 From 2007 to 2010 (especially 2007 to 2008), Zhou’s vlogs attracted the attention of China’s principal blogs (e.g., China Media Project) and international newspapers (e.g., the New York Times). Consequently, Zhou was featured in the documentary High Tech, Low Life (directed by Stephen Maing, 2012), increasing his visibility and fulfilling his desire for popularity.

Zhou currently is moving within news reporting, documentary filmmaking, writing, and performance. In English-language media (including his own website, http://www.zuola.com), he is referred to as an activist and a blogger, yet he describes himself as an artist who has produced many performance art works.47 Since migrating to Taiwan in 2011, he has expanded his online presence to a multimedia website while maintaining his weblog. On his home page, Zhou has a photo of his younger self in Tian’anmen Square with the caption: “a lonely knight, always selfieing by left hand” (see figure 2).

Zhou Shuguang. High Tech, Low Life (left) and zuola.com (right). Sources: High Tech, Low Life (directed by Stephen Maing, 2012) and https://www.zuola.com/.

In contrast to Zhou’s “lonely knight” identity and its focus on personal recognition, Wang Dezhi has developed a community-centered creative agenda. He remains localized as a storyteller of “the workers’ experience from an explicitly and unambiguously workers’ point of view … raising the class consciousness of … marginal social groups.”48 Wang cofounded the Migrant Workers Home (Gongyou zhi jia 工友之家) in Picun (Pi Village), Beijing, and partakes in various cultural projects.49 Seeing himself more as a cultural activist than a filmmaker, he has taken inspiration from professional filmmakers such as Jia Zhangke who have represented the subaltern but who, according to Wang, are too concerned with developing distinctive film aesthetics and gaining international recognition.50 Wang has produced several documentary and quasidocumentary narratives along with fictionalized accounts focusing on subaltern realities, including Pi Village (Picun 皮村, 2007), A Fate-Determined Life (Mingyun rensheng 命运人生, 2008), and Shunli Goes to the City (Shunli jin cheng 顺利进城, 2009), attracting academic attention.51 Wang also made a name for himself. His story and his face, voice, and words have appeared in state media (e.g., in CCTV’s five-episode documentary on Pi Village, marking the first migrant-worker Spring Festival Gala Dagong chunwan 打工春晚 in 2012) and in Huang Chuanhui’s award-winning reportage, recently translated into English.52

In line with his commitment to cultural activism, Wang has used his established individual authorship to develop collaborative projects. He is credited as screenwriter and director in Second-Generation Migrant (Yimin erdai 移民二代, 2017), produced by the “New Worker Video Team.” Described as Wang’s first feature film, its story, acting style, and narrative techniques (which include mock-documentary interviews) navigate the blurring lines between fiction and actual.53 At screenings and during interviews, Wang has emphasized the collective process, focused on advocacy and his localized belonging, distancing himself from the discourses on the creative subaltern shaped by either international independent art circles or national propaganda.

Diametrically opposite to Wang’s cultural activism, although displaying equal agency and resistance to be co-opted in those discourses, video blogger Li Ziqi (real name Li Jiajia 李佳佳) is a social influencer with vast popularity. Li has reframed subaltern creativity within the safe boundaries of traditional craft and folklore (presented as beautiful and peaceful), in striking contrast to Wang’s problematic, contentious, and unsettled urban narratives. Li’s videos are widely viewed and praised for their lyricism and their reappraisal of slow living as an alternative to urban fast living, although they have been criticized for being romanticized and too “perfect.”54

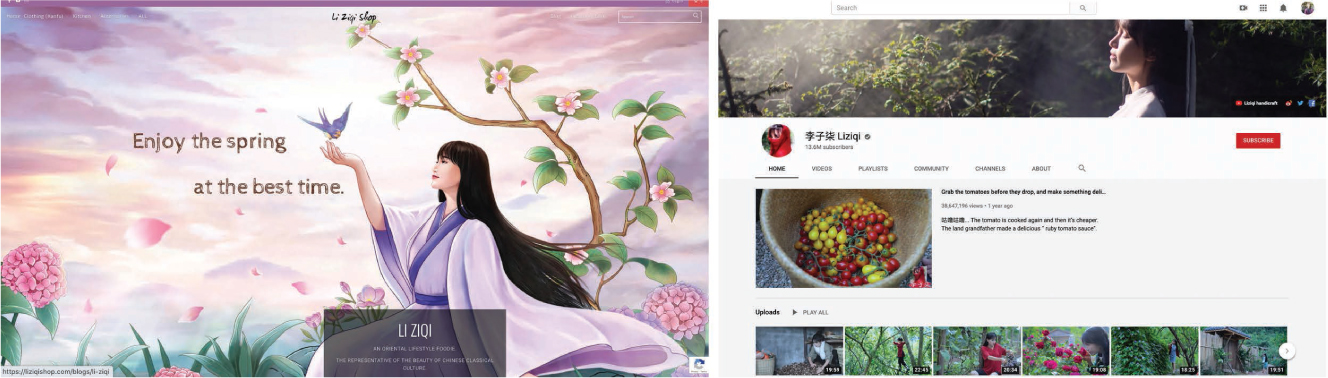

Li has become one of the most “Googleable” or “Baiduable” Chinese subaltern celebrities. Her online presence is remarkable, and one can read about her life and expanding activities in domestic and international news media (e.g., People’s Daily and The Guardian), specialized art and craft online magazines (e.g., Garland), blogs, and, of course, social media. Her short documentaries have reached millions of viewers in China and abroad and have attracted considerable media and academic attention, domestically and globally.

Li’s agency is characterized by two main claims, which may or may not be true but are clearly communicated in her videos and in the interviews she has released. Firstly, Li proudly declares a rural subaltern identity: Li and her creative works are localized in her home village, away from urban modernity and the cool city, where she lived for eight years before returning to her grandparents’ village in 2012. Her documentaries support Edensor and Millington’s proposition that “creativity proliferates and seethes in everyday life and in quotidian spaces, … cannot only be associated with entrepreneurs and artists, and is undoubtedly located in settings that are far from urban centres.”55 Secondly, Li appears to have full control of her creative process and circulation. She has repeatedly stated that her earlier videos were scripted, video recorded, and edited entirely by her and that, even though she now relies on the support of camera operators and editors, she is still the one who calls the shots. Even though state media has claimed her for upholding the same values as the Communist Party, Li has no need for government funding or additional exposure (tens of millions subscribe to her video channels and Weibo, with billions of views in China and abroad, easily surpassing television’s reach). Self-reliant, she has launched an online English-language website (https://liziqishop.com/), which includes a bio, news, links to her YouTube channel, and online shopping options to purchase Li Ziqi-branded merchandise (see figure 3).

Li Ziqi’s English-language website (left) and YouTube channel (right). Source: https://liziqishop.com/ and https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCoC47do520os_4DBMEFGg4A.

If one of the oppressive conditions of subalternity lies in its anonymity, one should see Li’s fame as a positive development for the creative subaltern. In Street Life, the trash collectors are referred to by nicknames and do not call each other by names; instead they use hometown names. In Dance with Farmworkers, one scene captures a moment in their training when all the participants (both workers and professional dancers), one after another, perform their names (i.e., they say their name with an associated movement) while the group collectively repeats the name and movement in acknowledgment. In a similar process, the repetition of Li’s name online is loud; she has stepped out of anonymity and appears to have done so on her own terms.

While different in their agendas and filmmaking styles, Li and Wang share a determination to retain a rural migrant identity and full control over their creative practices, distancing themselves from both national propaganda and international independent art circles. They do not see themselves as “artists,” nor do they wish to be recognized as such. Such ambition to belong to the Art (capital A) world instead becomes a main narrative focus in documentary films about worker-poets and worker-painters.

The Creative Subaltern as the Artist: Transformative Stories

Within the discourse of subaltern creativity, poetry and painting have become the foci of two acclaimed feature-length documentary productions: The Verse of Us (Wode shibian 我的诗篇, directed by Qin Xiaoyu and Wu Feiyue, 2015, released internationally as Iron Moon) and China’s Van Goghs (directed by Yu Haibo and Yu Tianqi, 2016). In both cases, the audiovisual narrative was expanded and connected with other multimedia projects. Focusing on worker-painters, China’s Van Goghs intersects with photojournalist Yu Haibo’s exhibitions, Winnie Wong’s monograph Van Gogh on Demand, Wong’s interview on the Shanghaiist website, the New York Times’ story “Own Original Chinese Copies of Real Western Art!,” and the state-supported Dafen International Oil Painting Biennale.56 Similarly, The Verse of Us, which focuses on worker-poets, intersects with an anthology of translated poems and other publications on dagong poetry.57 The worker-poets presented in the documentary and anthology participate in local events and publications, thus connecting with grassroots literary movements and state-sponsored institutions.

In these two films, the subaltern is the creative subject, not the subordinated collaborator in a project that is authored and owned by others. The subaltern’s artistic works (paintings and poems) are showcased, their authors explaining, reflecting, and commenting on who they are, how their art came to be, and what they wish to convey. The filmmakers clearly are committed to making subaltern art known and appreciated. In The Verse of Us particularly, the subaltern artist appears on-screen, and off-screen they remain an active albeit unequal participant in the documentary event. Furthermore, in these films, the creative subaltern are the protagonists, their life stories emplotted in the documentary and used to provide explanations, commentaries, and meaning. However, the emphasis on transformative storytelling risks overlooking the cultural and social hierarchies that devalue subaltern art and reducing its complex, ambiguous expressivity by explaining it, often didactically, as a mere reflection of the authors’ subaltern condition.

The Verse of Us focuses on the lives and poems of five poets. Wu Xia 邬霞, a garment worker living in Shenzhen; Wu Niaoniao 乌鸟鸟, a forklift driver; Lao Jing 老井, a coal miner; Chen Nianxi 陈年喜, a demolitions worker; and Xu Lizhi 许立志, the “absent” poet who killed himself while working at Foxconn and whose poem refers to the “iron moon” used as the title of the English-language version. The poets’ life stories are foregrounded as they step into the public space with their poetry. This space is welcoming and receptive, unlike their alienating, oppressive workplaces.

The film starts with shots of buildings, streets, and an airplane with the caption “Beijing”; a voice-over states, “I believe that in Chinese poetry’s history of several thousand years, this conference of worker-poets will leave a deep impact.” The scene cuts to a spotlight in a small, crowded hall; the voice belongs to the figure standing onstage, Yang Lian 杨炼, whom the caption describes as guoji zhuming shiren 国际著名诗人 (famous international poet). Yang introduces the first worker-poet, Wu Niaoniao. As Wu walks up to the stage, the camera follows him from behind, then slowly turns quasi-360 degrees, shifting from the audience’s point of view to a close-up of his face. With visual symbolism, the worker-poet is shown emerging from an obscure, anonymous audience, as the named, international poet offers him the spotlight.

The scene fades into a snowfall. The snowflakes are in the foreground with a blurred image of a city behind, then sharp images of snow-covered trees follow as Wu’s voice-over recites the first lines of his poem. Cutting back to the hall, the camera has now completed the 360-degree circle, taking Wu’s point of view, with an over-the-shoulder shot that shows the audience, blurred, as the spotlight blinds him (and us, the viewers). While Wu recites the poem on- and off-screen, the scene alternates close-ups of his face with images of the forest, a snow-covered city street, cars moving in slow motion, white pigeons on electric cables, and, in slow motion, people by railroad tracks, all covered in snow as the snowfall continues, ending with Wu uttering the final lines. A piano piece accompanies images of the snow-covered city as the film credits are interspersed with quotations from poems by Chi Moshu 池沫树, Xie Xiangnan 谢湘南, and Zheng Xiaoqiong 郑小琼 (worker-poets not included in the documentary), ending with the opening lines of Xu Lizhi’s “I Swallowed an Iron Moon.” A black screen follows, with the directors’ names, then the title, graphically composed to make the Chinese characters resemble snowflakes. Below, a small under-title quotes the closing line of Walt Whitman’s “O Me! O Life!” (“The powerful play goes on, and you may contribute a verse”), beneath which the English translation of the title appears, rendered as “The Verse of Us,” a marker of the film’s transcultural and translingual agenda (see figure 4).

This opening presents subaltern poetry as championed and validated by an intellectual elite that is domestically situated and internationally recognized. It establishes a dark-to-light symbolic trajectory to visualize the worker-poets’ journey out of their gloomy dagong condition. The snow contrasts with the grey of the polluted cities/factories and the darkness of the mines where the poets work and which the poems describe.

Poetry is brought on-screen. At times, poems are connected with their authors, who recite their work in intimate close-ups or as voice-overs to shots of their work or living environment. Wu, Xu Hongzhi 许鸿志 (Xu Lizhi’s brother), and Jike Ayou 吉克阿优 (in traditional Yi minority dress) are shown reciting their poems at a public reading. Other times, poems are associated with images reflecting and expounding their content. For instance, Xu Lizhi’s “Liushui xiande bingmayong 流水线的兵马俑” is recited with an echoing effect over an ominous soundtrack while a sequence of cranes, factories, and buildings appears on-screen in foggy, greyish surroundings. The poem’s final lines are associated with a slow-motion shot of workers clocking in; then, as fast-paced music begins, workers assemble in rows; a montage follows of assembly lines, machines, and containers shown in fast-motion, intercut with static images of Xi’an terra-cotta warriors.

These examples show how the film “is interspersed with written and spoken moments of poetry,” adding “an inspirational angle.”58 These moments, however, are outweighed by the worker-poets’ life stories. Their work and family conditions are foregrounded while the poetic dimension is an oblique, temporary incursion in the reality that poetry can momentarily escape but not impact on.

In China’s Van Goghs, paintings are more than “interspersed” moments. The art form suits visualization on-screen, and the camera focuses at length on the paintings’ textures, strokes, and colors and the workshop’s palettes, brushes, canvasses, and squeezed paint tubes. While playing a significant role in the film’s cinematography, subaltern Art is subordinate to the protagonist Zhao Xiaoyong, whose life story forms the main narrative. The documentary shows his interactions with his family, apprentice workers, and fellow painters while they eat, drink, work, or sing at a karaoke bar. The main story line centers on a trip to Europe, where Zhao encounters a client and sees Van Gogh’s original paintings, the inspiration for his own artistic self-discovery.

During the film, Zhao expresses his views about art and his ambitions, not always coherently. He sometimes conveys these reflections during meals, when everybody is inebriated. One night while he is in Amsterdam, Zhao strolls the streets with his friends, fantasizing about being true artists like Van Gogh: “Now, it’s not me. I’ve turned into Van Gogh.” Back in his hotel room, he is shown throwing up while his friend pats his shoulder and lights a cigarette. Next, a close-up of real sunflowers takes us to the Orville cemetery in France, where Zhao is paying respect to Van Gogh’s grave. Then we are back in Shenzhen with its crowded buildings and myriad lights; the city at night contrasts with the colorful, bright palette of the Orville cemetery. During a meal with his fellow painters, the inebriated Zhao shares his memories and his determination to be more than a copy painter. The epilogue presents an insight into his transformed life: original paintings adorn his workshop, depicting the worker-painters themselves, a mise en abyme of subaltern art (see figure 5).

The Verse of Us and China’s Van Goghs bring into focus subaltern Art, giving the creative subaltern unprecedented prominence. However, while the artworks (poems and paintings) are presented on-screen, the films concentrate on the artists’ stories, emphasizing their transformative journeys (from dark mines to the stage spotlight, from Shenzhen to Amsterdam, etc.).59 Tellingly, film reviews invariably only discuss the protagonists’ subaltern condition, not mentioning how their artworks intervene in China’s literary and art worlds, from which subaltern creativity continues to be excluded.

Transformative storytelling has become a main activist strategy for nonprofit organizations that advocate social change. For example, Transformative Storytelling for Social Change (2020) proposes that “creative storytelling approaches combine a participatory, collaborative methodology with the creative use of technology to generate stories aimed at catalysing action on pressing social issues.”60 In documentary filmmaking, deploying transformative narratives has become a means of conveying stronger, more effective messages, especially when addressing social inequality.61 Chinese documentaries focusing on the subaltern have shared this drive. Concerned about social change and developing a participatory methodology, cultural activist Wang Dezhi embraces transformative storytelling’s principles, showing that “the personal is political” and that the tension between the two is still relevant and pivotal to our understanding of storytelling in the postmedia age.62 I am not suggesting that this powerful method for community building and grassroots activism should be dismissed as inherently flawed. However, in documentary filmmaking about (subaltern) creativity, transformative storytelling may obfuscate creativity and its ability to (re)imagine, rather than observe and reflect, reality. Plot-driven transformative stories may not be the best way to “capture the imagination of people.”

In 2018, a group of “practitioners and scholars drawn to documentary because of its potential to intervene in the dominant consensus of the perceived world” produced “Beyond Story,” an online community-based manifesto, as a critique of “story-driven docs … built to neatly hold a compelling cast of characters in their clear and coherent world.” The manifesto attacks the pervasive nature of documentary stories focused on (1) “a small number of recognizable characters around whom feelings are generated, primarily by way of identification and cathexis, humanism and empathy” and (2) “said characters’ actions being arranged through a set of recognizable spatial/temporal templates that cohere only nominally to lived reality given that they are arranged through a cause-effect logic that does not remotely resemble reality as it is experienced.”63 Not opposed to stories per se, the manifesto calls for less formulaic documentary and echoes Free Cinema’s advocacy to embrace a spectrum of narrative possibilities, including disruptive and associative nonlinear expressive forms. By exploring these alternatives and breaking free from plot-driven narrative, documentary may intervene more effectively in the discourse of subaltern creativity.

Epilogue: Ceci n’est pas la réalité: Imagination, Lyricism, and Attitude

Entangled in the “contested, fraught space” of subalternity and discourse about creativity, with its “elitist, class-ridden definitions” and its privileged association with the cool city, documentary in China has functioned as both a text and a metatext for subaltern creativity. I have argued that subaltern creative practices have appeared obliquely in documentary films, tangential to other narratives or subordinate to the authorship of internationally recognized artists. More recently, the subaltern creator—rather than the creative subaltern—has acquired a more central role, becoming an author or the protagonist of documentary films. In the films discussed, subaltern creative practices are not a cohesive set of works (least of all a “movement”); rather, they diverge significantly in their content, form, goals, and audiences. Yet, even though they are “not made together,” they have a common “attitude,” a shared “belief in freedom, in the importance of people and the significance of the everyday.”64 Taking my essay to its conclusion, I return to the ideas and practices developed by Free Cinema.

A participant in the Free Cinema movement, Lorenza Mazzetti was an Italian migrant who had moved to the United Kingdom in 1951. “On her first day at the Slade School of Fine Art,” she “declared herself … a genius” in order to get support for her first short film K.65 Later, with support from the Slade and BFI’s Experimental Film Fund, she directed Together (1956), a “quasi-documentary account of day-to-day survival,” and she became known as the Italian who renewed British documentary.66 In Together, the subaltern protagonists—two dockworkers living humbly in London’s East End—are both deaf and mute; their friendship with each other and their alienation from others are marked by silence. Mazzetti’s goal was to express the isolation and disorientation that she had personally experienced. She maintained that Together was “a poetic film.”67 In line with the Free Cinema manifesto, Mazzetti showed that “you can use your eyes and ears. You can give indications. You can make poetry.”68 This emphasis on personal and lyric expressivity is relevant in a context (such as the Chinese one) in which subaltern creativity still remains largely collectivized and actualized while its imaginative, subjective, and artistic qualities are devalued. The question then is: In order to capture the imagination of the people, can documentary “make poetry”?

While not “poetic films,” China’s Van Goghs and The Verse of Us include incursions in personal and lyric expressivity in their transformative storytelling. For example, the documentary’s narrative almost comes to a standstill in one scene that shows Zhao painting a Van Gogh self-portrait. With non-diegetic music and no ambient sound, the painter and the act of painting are captured via a sequence of extreme close-ups of the canvas, the brush strokes, and details of Zhao’s eyes, mouth, and pores. Similarly, while cinematographically less sophisticated and symbolically more explicit, the interspersed moments of poetry in The Verse of Us rupture the observational style of the main narrative, allowing the worker-poets and their poems to explore a semiotic world beyond the reality of their subaltern condition. In the same way, Da Pangzi’s and Zhang Jinli’s performances can also be seen as brief, albeit meaningful and impactful, insertions of lyric realism, which suspend the documentaries’ main narratives so that their reality resembles, but is no longer, what society expects it to be. In these quasiaccidental “exhibitionist” moments, their subaltern condition (the political) remains visible but is interpreted as a personal and subjective experience.69

Comparing Mazzetti’s personal and lyric expressivity to Li Ziqi and her short documentaries is a thought-provoking exercise. Once we factor in the diverse historical, technological, and cultural contexts in which these two filmmakers turned their cameras to the everyday, meaningful similarities exist between their creative perspectives. Mazzetti and Li are “unlikely” filmmakers, initially self-taught and navigating a male-dominated context. They place the personal at the core of their filmmaking, emphasizing silence and actions rather than words or plot-driven narratives.

Li, however, is positioned outside—and in opposition to—the discourse of the avant-garde. She borrows visual techniques and conventions from mainstream advertising and TV food documentaries and is located as a social influencer within digital cultures and social media, thus differing from the antimainstream attitude of Free Cinema’s Mazzetti. Yet Anderson advocated for “a new kind of intellectual and artist, … who does not see himself as threatened by, and in natural opposition to, the philistine mass; who is eager to make his contribution, and ready to use the mass-media to do so.”70 Anticipating later developments brought about by digital cultures and challenges by fans and amateur artists to highbrow/lowbrow divides, Anderson thought it possible and appropriate to “capture the imagination of the people” by using different expressive forms, including mainstream media.

Can we therefore evaluate Li and her videos “in emotional, human, poetic terms”? Can we consider her work “poetic film” and, if not, why? Is the way Li captures “the imagination of the people” to be discarded because of its sentimental idealization of country life or her mainstream media popularity? Or does she still “intervene in the dominant consensus of the perceived world”?71 Instead of relying on elitist, class-ridden definitions and untenable divides between highbrow and lowbrow cultures (Big-C, little-c), we can address these questions if we understand that subaltern creative practices and Li’s short docs, while rooted in the reality of their subaltern condition, are not merely a reflection of it. Ceci n’est pas la réalité, this is not reality.

In his study on Magritte’s “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” (The treachery of images), Michel Foucault examines the tension between image and text in the painting and argues that it makes us ponder how we perceive reality precisely because it brings together two separate, distinctive semiotic systems: images and words.72 The encounter between creativity and subalternity involves a similar antagonist tension between two semiotic systems—subalternity and creativity—which both deal with reality but approach it, see it, understand it, and experience it differently. As a creative subject, the subaltern does not seek the delusion of a “fantasy world” but reclaims the freedom to interpret and reimagine reality and her/his/their own place in it.73 As an expression of (political) resistance and (personal) creativity, imagination is reconcilable with reality: it is a key attitude in representing, interpreting, and intervening in it. In order to capture the imagination of the people, documentary still needs to bear witness to reality (“use your eyes and ears”) but can and should also dare to “make poetry.”74

Acknowledgments

This essay greatly benefitted from the Global Storytelling Symposium at Hong Kong Baptist University, January 28–30, 2020, generously supported by the Centre for Film and Moving Image Research. I am very grateful to Alexandra Juhasz, who introduced the “Beyond Story” manifesto to me, and Rochelle Simmons for making me discover the works of Lorenza Mazzetti.

Notes

- Luke Robinson, “ ‘To whom do our bodies belong?’ Being Queer in Chinese DV Documentary,” in DV-Made China: Digital Subjects and Social Transformations after Independent Film, eds. Zhen Zhang and Angela Zito (Hawai’i: University of Hawai’i Press 2015), 289. ⮭

- Eric Florence, “Rural Migrant Workers in Independent Films: Representations of Everyday Agency,” Made in China 3, May 18, 2018, https://madeinchinajournal.com/2018/05/18/rural-migrant-workers-in-independent-films/. ⮭

- Lindsay Anderson, “Get Out and Push!,” Encounter (1957): 14–22, https://www.unz.com/print/Encounter-1957nov-00014/. ⮭

- Anderson, “Get Out and Push!,” 22. ⮭

- The name refers to freedom from “the pressures of the box-office or the demands of propaganda” and freedom to explore realities beyond metropolitan ones. See Christophe Dupin, “A History of Free Cinema,” BFI Screenonline, accessed August 9, 2020, http://www.screenonline.org.uk/film/id/444789/index.html. ⮭

- Dupin, “A History of Free Cinema.” ⮭

- Lindsay Anderson, Lorenza Mazzetti, Karel Reisz, and Tony Richardson, “Free Cinema Manifestos (UK, 1956–1959),” in Film Manifestos and Global Cinema Cultures: A Critical Anthology, ed. Scott MacKenzie (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014), 149. ⮭

- Jia Zhangke, “Youle VCD he shuma shexiangji yihou 有了 VCD 和数码摄像机以后” (Now that we have VCDs and digital cameras), in Yige ren de yingxiang: DV wanquan shouce 一个人的影像: DV 完全手册, ed. Zhang Xianmin 张献民 and Zhang Yaxuan 张亚璇 (Beijing: Zhongguo qingnian chubanshe, 1999), 309–11. ⮭

- Tejal Rao, “The Reclusive Food Celebrity Li Ziqi Is My Quarantine Queen,” New York Times, last modified April 20, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/22/dining/li-ziqi-chinese-food.html. ⮭

- Jeffrey Zimmerman, “From Brew Town to Cool Town: Neoliberalism and the Creative City Development Strategy in Milwaukee,” Cities 25, no. 4 (2008): 230–42; Reeman Mohammed Rehan, “Cool City as a Sustainable Example of Heat Island Management Case Study of the Coolest City in the World,” HBRC Journal 12, no. 2 (2016): 191–204. ⮭

- Tim Edensor and S. D. Millington, “Spaces of Vernacular Creativity Reconsidered,” in Creative Placemaking: Research, Theory and Practice, eds. Cara Courage and Anita McKeown (London: Routledge, 2018), 33. ⮭

- Stuart Hall, David Morley, and Kuan-Hsing Chen, Stuart Hall: Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies (London: Routledge, 1996); Henry Jenkins, Fans, Bloggers, and Gamers: Exploring Participatory Culture (New York: New York University Press, 2006); Ian Hargreaves and John Hartley, The Creative Citizen Unbound: How Social Media and DIY Culture Contribute to Democracy, Communities and the Creative Economy (Bristol: Policy Press, 2016); Carlos Alberto Scolari, “Transmedia Storytelling: Implicit Consumers, Narrative Worlds, and Branding in Contemporary Media Production,” International Journal of Communication 3 (2009): 586–606; Henry Jenkins, “Transmedia Storytelling and Entertainment: An Annotated Syllabus,” Continuum 24, no. 6 (2010): 943–58. ⮭

- Richard Florida, “The Rise of the Creative Class,” Washington Monthly, 2002, https://washingtonmonthly.com/magazine/may-2002/the-rise-of-the-creative-class/. ⮭

- While most of Florida’s measurable factors rely on statistical data, the “diversity factor” is problematic. Rather than addressing the complexity of what diversity entails, Florida identifies diversity with “the Gay Index,” which he describes as “a reasonable proxy for an area’s openness to different kinds of people and ideas.” See Florida, “The Rise of the Creative Class.” ⮭

- Michael Keane, Creative Industries in China: Art, Design and Media (Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2013); Paola Voci and Luo Hui, Screening China’s Soft Power (Abingdon: Routledge, 2017); Ying Zhu, Kingsley Edney, and Stanley Rosen, Soft Power with Chinese Characteristics: China’s Campaign for Hearts and Minds (Abingdon: Routledge, 2019). ⮭

- Xiaoye You, “Chinese White‐Collar Workers and Multilingual Creativity in the Diaspora,” World Englishes 30, no. 3 (2011): 409–27. ⮭

- Jian Lin, “(Un-)becoming Chinese Creatives: Transnational Mobility of Creative Labour in a ‘Global’ Beijing,” Mobilities 14, no. 4 (2019): 453. ⮭

- Yiu Fai Chow, “Exploring Creative Class Mobility: Hong Kong Creative Workers in Shanghai and Beijing,” Eurasian Geography and Economics 58, no. 4 (2017): 362. ⮭

- Chow, “Exploring Creative Class,” 364. Emphasis added. ⮭

- Edensor and Millington, “Spaces of Vernacular Creativity Reconsidered,” 38. ⮭

- James C. Kaufman and Ronald A. Beghetto, “Beyond Big and Little: The Four C Model of Creativity,” Review of General Psychology 13, no. 1 (2009): 1–12. ⮭

- Kaufman and Beghetto, “Beyond Big and Little,” 2 ⮭

- Wanning Sun, “Subalternity with Chinese Characteristics: Rural Migrants, Cultural Activism, and Digital Video Filmmaking,” Javnost-The Public 19, no. 2 (2012): 84–85. ⮭

- Anita Chan, China’s Workers under Assault: Exploitation and Abuse in a Globalizing Economy (London: Routledge, 2016); Hairong Yan, New Masters, New Servants: Migration, Development, and Women Workers in China (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2008). ⮭

- James C. Scott, Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008); Ivan Franceschini, “Labour NGOs in China: A Real Force for Political Change?,” China Quarterly 218 (2014): 474–92; Lianjiang Li and Kevin J. O’Brien, Rightful Resistance in Rural China (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006); Pun Ngai, Made in China: Women Factory Workers in a Global Workplace (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005). ⮭

- Paola Voci, “Activist Sinology and Accented Documentary: China on the (Italian?) Internet,” Modern Italy 24, no. 4 (2019): 437–56. ⮭

- Made in China Journal, “About Us,” accessed July 30, 2020, https://madeinchinajournal.com/. ⮭

- China Labour Bulletin, “About Us,” accessed July 30, 2020, https://clb.org.hk/. ⮭

- Rey Chow, Entanglements, or Transmedial Thinking about Capture (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012). ⮭

- Sun, “Subalternity with Chinese Characteristics”; Wanning Sun, Subaltern China: Rural Migrants, Media, and Cultural Practices (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2014); Wanning Sun, “From Poisonous Weeds to Endangered Species: Shenghuo TV, Media Ecology and Stability Maintenance,” Journal of Current Chinese Affairs 44, no. 2 (2015): 17–37. ⮭

- Maghiel van Crevel, “The Cultural Translation of Battlers Poetry (Dagong shige),” Journal of Modern Literature in Chinese 現代中文文學學報 14, no. 2 (2017): 245–86; Maghiel van Crevel, “Debts: Coming to Terms with Migrant Worker Poetry,” Chinese Literature Today 8, no. 1 (2019): 127–45; Haomin Gong, “Ecopoetics in the Dagong Poetry in Postsocialist China: Nature, Politics, and Gender in Zheng Xiaoqiong’s Poems,” ISLE: Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment 25, no. 2 (2018): 257–79. ⮭

- Winnie Wong, Van Gogh on Demand: China and the Readymade (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014), 56. ⮭

- Sun, “Subalternity with Chinese Characteristics,” 98. ⮭

- Ngai-Ling Sum, “The Makings of Subaltern Subjects: Embodiment, Contradictory Consciousness, and Re-hegemonization of the Diaosi in China,” Globalizations 14, no. 2 (2017): 298–312, https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2016.1207936. ⮭

- Zhenhuan Ma, “Dance with Zhejiang Couple Lifts Spirits of Millions,” China Daily, last modified June 8, 2020, https://global.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202006/08/WS5ede16e7a3108348172519a3.html. ⮭

- China Daily, “Online Folk Singer Gives a Voice to Migrant Workers,” China Daily, last modified January 17, 2020, http://epaper.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202001/17/WS5e20efc7a310a2fabb7a1982.html. ⮭

- Zhen Zhang, “Transfiguring the Postsocialist City: Experimental Image-Making in Contemporary China,” in Cinema at the City’s Edge: Film and Urban Networks in East Asia, eds. Yomi Braester and James Tweedie (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2010), 95–118; Xiaoping Wang, “Portraying the Abject and the Sublime of the Subaltern,” in Postsocialist Conditions, 199–245; Jin Liu, “The Rhetoric of Local Languages as the Marginal: Chinese Underground and Independent Films by Jia Zhangke and Others,” Modern Chinese Literature and Culture 18, no. 2 (2006): 163–205. ⮭

- Nat Trotman, “Cao Fei: Whose Utopia,” Guggenhein, accessed October 7, 2020, www.guggenheim.org. ⮭

- Chris Berry, “Images of Urban China in Cao Fei’s ‘Magical Metropolises,’ ” China Information 29, no. 2 (2015): 202–25. ⮭

- Berry, “Images of Urban China,” 214. ⮭

- CEAS, “CEAS Film Series,” Yale, accessed October 12, 2020, https://ceas.yale.edu/events/dv-china-2002-dance-farm-workers-2001. ⮭

- Fangfei Miao, “Here and Now—Chinese People’s Self-Representation in a Transnational Context,” Congress on Research in Dance Conference Proceedings (2015): 114, https://doi.org/10.1017/cor.2015.19. ⮭

- Miao, “Here and Now,” 115. ⮭

- “To Live to Sing,” NZIFF, accessed October 12, 2020, https://www.nziff.co.nz/2020/at-home-online/to-live-to-sing/. ⮭

- Ying Qian, “Just Images: Ethics and Documentary Film in China,” China Heritage Quarterly 29 (2012), http://www.chinaheritagequarterly.org/scholarship.php?searchterm=029_qian.inc&issue=029. ⮭

- David Bandurski, “Chinese Blogger ‘Zola’ Reports from the Scene on Chongqing’s ‘Nail House,’ ” China Media Project (blog), March 30, 2007, http://chinamediaproject.org/2007/03/30/chinese-blogger-zola-reports-from-the-scene-on-chongqings-nail-house/. ⮭

- Zhou Shuguang, “About,” Zuola.com 佐拉, accessed October 12, 2020, https://www.zuola.com/about.htm. ⮭

- Sun, “Subalternity with Chinese Characteristics,” 89. ⮭

- In 2002, Wang and Sun Heng “set up the first dagong amateur art and performance troupe in China and gave more than 100 [free] concerts for migrant workers.” They were “motivated by a desire to ‘give voice through songs, to defend rights through law.’ ” See Sun, “Subalternity with Chinese Characteristics,” 88. ⮭

- Sun, Subaltern China, 138–39. ⮭

- Sun, Subaltern China, 139–40; Jenny Chio, “Rural Films in an Urban Festival: Community Media and Cultural Translation at the Yunnan Multi Culture Visual Festival,” in Chinese Film Festivals, eds. Chris Berry and Luke Robinson (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017). ⮭

- Chuanhui Huang, Migrant Workers and the City: Generation Now (Black Point: Fernwood, 2016). ⮭

- Hatty Liu, “Migrant Identities,” World of Chinese (blog), July 3, 2017, https://www.theworldofchinese.com/2017/03/migrant-identities/. ⮭

- Alex Colville, “Li Ziqi, the New Face of China’s Countryside,” SupChina (blog), July 27, 2020, https://supchina.com/2020/07/27/li-ziqi-a-reclusive-country-vlogger-who-became-an-online-celebrity/. ⮭

- Edensor and Millington, “Spaces of Vernacular Creativity Revisited,” 39. ⮭

- Paola Voci, “Can the Creative Subaltern Speak? Dafen Village Painters, Van Gogh, and the Politics of ‘True Art,’ ” Made in China Journal 5, no. 1 (2020), https://madeinchinajournal.com/2020/05/13/can-the-creative-subaltern-speak-dafen-village-painters-van-gogh/. ⮭

- van Crevel, “The Cultural Translation of Battlers Poetry (Dagong shige)”; Maghiel van Crevel, “Debts: Coming to Terms with Migrant Worker Poetry,” Chinese Literature Today 8, no. 1 (2019): 127–45; Gong, “Ecopoetics in the Dagong Poetry in Postsocialist China.” ⮭

- Maghiel van Crevel, “Iron Moon: An Anthology of Chinese Migrant Worker Poetry and Iron Moon (the Film),” MCLC Resource Center Publication (blog), February 2017, https://u.osu.edu/mclc/book-reviews/vancrevel4/. ⮭

- Similarly, Still Tomorrow (directed by Fan Jian, 2016) focuses on the “transformative story” of dagong poet Yu Xiuhu, a woman struggling with cerebral palsy and an arranged marriage, whose fame on social media leads to financial freedom and emancipation. ⮭

- “Handbook,” Transformative Storytelling for Social Change, last modified August 30, 2020, https://www.transformativestory.org. ⮭

- Sheila Curran Bernard, Documentary Storytelling: Creating Nonfiction Onscreen (New York and London: Focal Press, 2012); Caty Borum Chattoo and Lauren Feldman, “Storytelling for Social Change: Leveraging Documentary and Comedy for Public Engagement in Global Poverty,” Journal of Communication 67, no. 5 (2017): 678–701. ⮭

- Carol Hanisch, “The Personal Is Political,” in Radical Feminism: A Documentary Reader, ed. Barbara A. Crow (New York: New York University Press, 2000). ⮭

- Alexandra Juhasz and Alisa Lebow, “Beyond Story: An Online, Community-Based Manifesto,” World Records Journal, accessed July 20, 2020, https://vols.worldrecordsjournal.org/02/03. ⮭

- Anderson et al., “Free Cinema Manifestos,” 149. ⮭

- Pamela Hutchinson, “Lorenza Mazzetti Obituary,” The Guardian, last modified January 20, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/film/2020/jan/20/lorenza-mazzetti-obituary. ⮭

- Francesca Massarenti, “ ‘Not My Country, Not My Home, Nobody in the Whole World’: The Life and Cinema of Lorenza Mazzetti (1928–2020),” Another Gaze, last modified January 8, 2020, https://www.anothergaze.com/not-country-not-home-nobody-whole-world-life-cinema-lorenza-mazzetti/. ⮭

- Massarenti, “ ‘Not My Country.” ⮭

- Anderson et al., “Free Cinema Manifestos,” 150. ⮭

- Tom Gunning, “The Cinema of Attractions: Early Film, Its Spectator and the Avant-Garde,” in Early Cinema: Space, Frame, Narrative, ed. Thomas Elsaesser (London: BFI, 1990). ⮭

- Anderson, “Get Out and Push!,” 22. ⮭

- Juhasz and Lebow, “Beyond Story.” ⮭

- Michel Foucault, “Ceci n’est pas une pipe,” trans. Richard Howard, October 1 (1976): 7–21. ⮭

- The media emphasis on Li Ziqi’s “D.I.Y. fantasy world” and how “her D.I.Y. pastoral fantasies” are “source of escape and comfort” undervalues Li’s creative choices—her style and attitude—in capturing her own subaltern reality. See Rao, “The Reclusive Food Celebrity Li Ziqi”. ⮭

- Anderson et al., “Free Cinema Manifestos,” 150. ⮭

Author Biography

Paola Voci specializes in Chinese cinema and visual cultures, and, in particular, documentary, animation, and other hybrid digital video practices. She is the author of China on Video, a book that analyzes and theorizes light movies made for and viewed on computer and mobile screens, and co-editor of Screening China’s Soft Power, a book focusing on the role played by film and media in shaping China’s global image. Her current research is on handmade cinema, shadow play and animation and other amateur, vernacular practices and their contribution to the archaeology of the moving image.