On New Year’s Eve 1959, Ferry to Hong Kong was screened at the Lee Theatre and the Astor in Hong Kong. Produced by Rank Organization as its first CinemaScope feature, and directed by Lewis Gilbert, the British film was shot on location in Hong Kong and Macau from October 1958 to February 1959.1 The big-budget film tells the real-life tale of Steven Ragan (also known as Michael Patrick O’Brien), a stateless drifter who was stuck for ten months (315 days) between 1952 and 1953 on the ferry shuttling between Hong Kong and Macau. Born an Austro-Hungarian, Ragan had previously worked in a Shanghai bar before he escaped from China, after the Communist takeover, and set foot in Macau in 1952. When his permit was revoked in the former Portuguese colony, he sneaked onto a Hong Kong-Macau ferry to avoid deportation to mainland China.2 The international press keenly reported on his unusual but hard-to-be-vindicated experience, which was subsequently fictionalized by Simon Kent (the penname of Max Catto) in the book Ferry to Hongkong.3

In the film adaptation, the Hong Kong police deport Mark Conrad (played by Curt Jurgens), a drunken Anglo-Austrian exile, tossing him aboard a ferry with a one-way ticket to Macau. When Macau rejects him as an undesirable, Conrad is condemned to be a man without a country. Taking the ferry as his makeshift home, he finds himself in a romantic encounter with Liz Ferrers (Sylvia Syms), a kindhearted schoolteacher cruising daily with her Chinese students on the passenger boat.

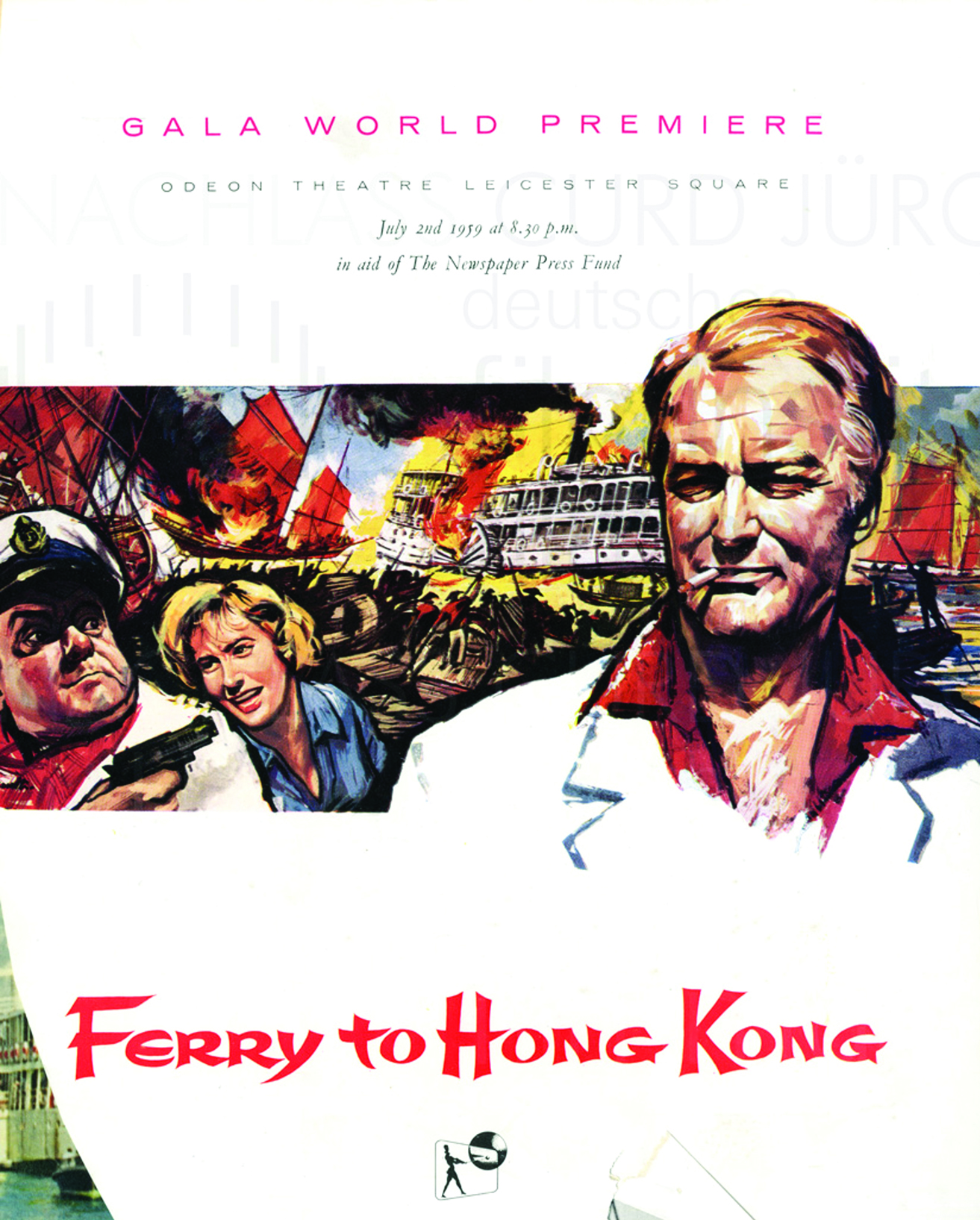

Ferry to Hong Kong was marketed as an “international film” targeting the US market.4 Rank contracted British box-office star Curt Jurgens and famed American director and actor Orson Welles (fig. 1).

Source: “Ferry to Hong Kong (1959) Programm der Gala World Premiere, London (GB),” Curt Jürgens: The Bequest, Deutsches Filminstitut & Filmmuseum, 1959, https://curdjuergens.deutsches-filminstitut.de/nachlass/ferry-to-hong-kong-1959-programm-der-gala-world-premiere-london-gb/. Reproduced by permission of Deutsches Filminstitut & Filmmuseum.

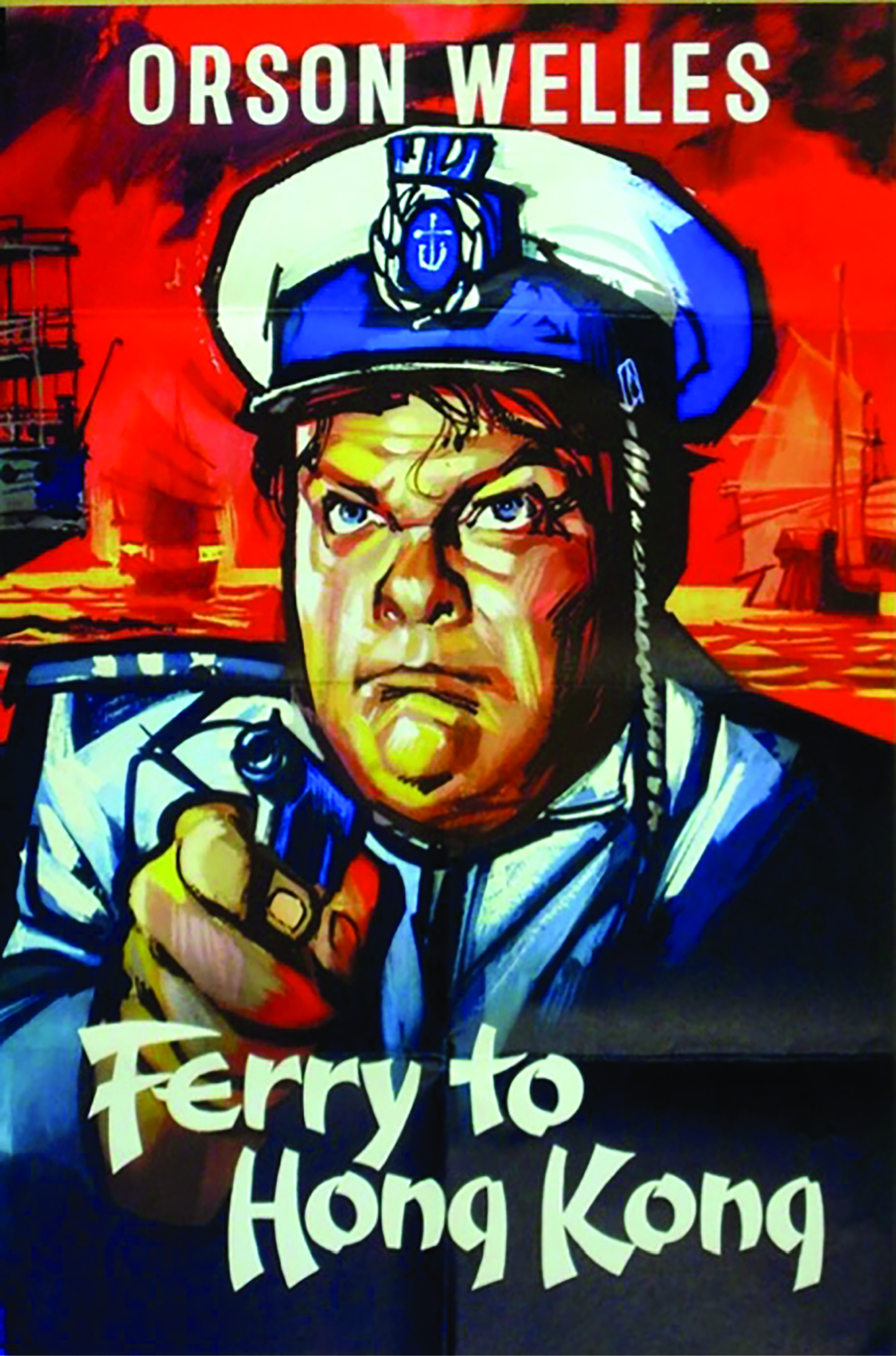

But British critics unanimously disapproved of Orson Welles, who played Captain Hart of the ferryboat, as giving his worst-ever performance.5 They ridiculed Welles’s deliberately bogus upper-class accent as a caricatured combination of Winston Churchill and the American comedian Jackie Gleason.6 Welles intended to “bluster to the extent that he [got] many unintentional laughs,”7 but his outrageous performance simply made audiences gasp in disbelief. The collaborations between Gilbert, Welles, and Jurgens did not work out smoothly. Gilbert described the shooting experience as outright “nightmarish,” mainly because of Welles’s arrogance.8 Jurgens and Welles swapped their roles before filming: Welles played the captain of the ferryboat and Jurgens the tramp.9 Welles had an interest to make the film a comedy, and often changed his own lines in filming, while Jurgens played the role seriously.10 Jurgens felt that his star status was being undermined by Welles and threatened to walk out.11 The British and American stars hated each other (fig. 2).

Source: “Ferry to Hong Kong (1959) Werkfoto 4,” Curt Jürgens: The Bequest, Deutsches Filminstitut & Filmmuseum, 1959, https://curdjuergens.deutsches-filminstitut.de/nachlass/ferry-to-hong-kong-1959-werkfoto-4/. Reproduced by permission of Deutsches Filminstitut & Filmmuseum.

In Gilbert’s memoirs, Welles on the set insisted on wearing a false nose, at one point holding up shooting for two days because he lost the correct false nose (fig. 3).12

Source: Brian Bysouth, Ferry to Hong Kong (UK Release Poster), 1959, Gregory J. Edwards on eBay, https://www.ebay.com/itm/120680537769.

He spoke with a bizarre voice with the false nose, and post-synching of his dialogues word by word only added to the weird effect.13 Notably, the disservice Welles’s overwhelming presence in the crew did to the filmmaking outweighed the value his fame was meant to add to the picture.14

In Hong Kong, David Lewin of China Mail conducted a four-installment interview series entitled “Third Man in Hong Kong” to echo The Third Man (dir. Carol Reed, 1949), an espionage noir set in postwar occupied Vienna. In the film, Welles portrayed the American racketeer Harry Lime, a fugitive sought after by the British military for trafficking in bogus penicillin to make a fortune.15 Making allusions to the Cold War, Welles remarked on Hong Kong as the “new Third Man territory” and the “free, wide-open city.”16 Taken as he was by the perilous charm of the underground world in Britain’s last colonial outpost, Welles viewed the city’s illegal businesses as “all part of the Third Man style,”17 notoriously as a haven for crime and adventure.

Gilbert’s reminiscences present an unruly Welles, who could not work with his British partners. Forget about the charisma of Welles and his cinematic classic Citizen Kane (1941). I take the untold story of Welles in Hong Kong and, more importantly, the uncomfortable cooperation between the British and American filmmakers in making Ferry to Hong Kong as emblematic of a rift in the Anglo-American alliance to defend Hong Kong against Communist China’s alarming aggression. The Anglo-American cinematic collaboration throws light on the uneasy relations between the two major Western Cold War allies, one a collapsed empire and the other an ascending global power.

On Asian Cold War fronts, the defense of Hong Kong had serious geopolitical and international implications for the United States. As Chi-kwan Mark contends, throughout the 1950s when conflicts in Korea, Indo-China, and the Taiwan Straits raised the specter of a Sino-American war in Asia, Hong Kong became a crucial concern in US foreign policy.18 As Britain kept on withdrawing its overseas garrisons due to its shrinking domestic economy, Hong Kong was rendered indefensible against an overt attack, save with US support. Anglo-American relations involved complicated negotiations—not only over the protection of Hong Kong but also concerning the general relationship of the two Western powers and the extent to which Britain was willing to support US causes in international affairs. Mark argues that Hong Kong was put in a difficult position as a “reluctant Cold War Warrior”19 in the Anglo-American alliance, as Britain had to juggle between the discordant commitments to maintaining friendly relations with China and avoiding ruptures in the American partnership.20

An allegorical reading of the production of Ferry to Hong Kong can deepen understanding of the underlying geopolitical narratives of Cold War Hong Kong. Gilbert agreed to make the film in the shadow of Britain’s special relationship with the United States, as embodied by Welles. The American filmmaker not only assumed an intimidating presence on the film set but also saw Hong Kong in Cold War terms as a city of political intrigue. Welles’s remark reminds us of Edward Dmytryk’s Soldier of Fortune (1955), in which Hong Kong was imagined as an “East Asian Casablanca,” a safe transit place for refugees and escapees from Red China and a refuge for Hank Lee (Clark Gable), the US Navy deserter turned smuggler and pirate.21 Welles observed that the frontier with China—“a collision of two worlds”—made the border one of the world’s most dangerous and exciting contact zones. As a famed American filmmaker—and a tourist—Welles gained special permission from colonial authorities to visit the China border area. He appreciated it as “the only place in the world where Britain ha[d] a common frontier with a Communist country and the Union Jack [flew] opposite the Red Flag.”22

When Welles alluded to Hong Kong as “the new Third Man territory,” he could have been voicing British fears of Soviet aggression in central Europe as much as the infiltration of Chinese Communism in Hong Kong and Southeast Asia. By 1949, British policymakers propagated the view that Hong Kong was the “Berlin of the East”—the linchpin of the eastern front of the Cold War—where rival empires had converged in the British colony.23 In September 1949, British foreign secretary Ernest Bevin told US secretary of state Dean Acheson that “Hong Kong was the rightwing bastion of the Southeast Asian front.” If Hong Kong were to be lost to the Communists “the whole front might go.”24 Hong Kong governor Alexander Grantham, who served his term of office in 1947–1957, perceived the new Chinese Communist regime as “violently anti-Western, anti-British, and anti-Hong Kong.”25 The political referent of Berlin, which was the most prominent symbol of the Cold War in a split Europe, was revoked to reveal the precarious and “indefensible” situation of Hong Kong as seen by British eyes.

No less important than economic and strategic reasons, the prestige factor in international affairs was pivotal in driving the British government to maintain control and stability of Hong Kong. Prime minister Clement Attlee warned his cabinet that a failure to defend Hong Kong “would damage very seriously British prestige throughout the Far East and South-East Asia.” Moreover, “The whole common front against communism in Siam, Burma and Malaya was likely to crumble unless the peoples of those countries were convinced of our determination and ability to resist this threat to Hong Kong.”26

The wave of decolonization, which gained momentum after World War II, was restructuring the world order as well as bringing the British empire to an end. For Britain the Asian Cold War began with the declaration of the emergency in Malaya in 1948. A more remarkable Anglo-American joint venture was The 7th Dawn (1964), produced by Rank and also directed by Lewis Gilbert, about an American major (played by American star William Holden) who helped Malayan forces defend Malaya from the Japanese invasion during World War II. After the war, he was drawn into the British’s counter-Communist operation in which he had to confront his former Chinese ally who joined the Communist rebel force. The 7th Dawn was released by United Artist in the United States, starring William Holden as one of the biggest box-office draws in Hollywood. The producer hoped that the film about British struggles in Cold War Asia “would help to make the American people as a whole more aware of the part Britain [was] playing against Communism in the Far East.”27 In addition, the US market was both commercially and diplomatically important for Rank to sell British war films abroad as well as to forge a united cultural front of British cinema and Hollywood in resistance to Communism.

The bargaining between British and American powers in international politics mirrors the nature of Anglo-American cooperation on the production of big-budget Cold War films as well as the delicate balance between this alliance and the anti-Communist coalition. Little known, however, is Welles’s cinematic trajectory from The Third Man, a political noir that captured the paranoia of Vienna during the four-power occupation of Austria from 1945–1955, to Ferry to Hong Kong, in which his high-profile excursions and interviews in Hong Kong obviously showed us the condescending gaze of an American visitor who squarely exoticized as well as marginalized the local realities of the city. The Third Man symbolized the underlying tensions and vulnerability of an Anglo-American alliance against the Soviets.28 The British could see themselves only as a diminishing empire caught between two monolithic powers, the United States and the Soviet Union.29 With contextual and textual scrutiny, I argue that A Ferry to Hong Kong not only revealed to us the vulnerability of this alliance at the production stage but that the cinematic imaginary itself was rather self-critical of British nostalgia with an uncertainty of imperialist ambitions to preserve the colony as what it used to be, in the period when Britain’s global position was surpassed by the United States, and in which empire defense was reconfigured as imperial retreat.

Cold War Cinematic Memories

This article analyzes the representation of British imperial nostalgia in a spectacular British-produced picture and an Anglo-American joint venture, Ferry to Hong Kong, to throw light on the cinematic connections between Britain and Cold War Hong Kong as a complex historical situation, in which US forces were proactively undertaking cultural interventions, not least through the dominating presence of Hollywood. Imperial nostalgia is “associated with the loss of empire—that is, the decline of national grandeur and the international power politics connected to economic and political hegemony.”30 Postwar British cinema is a compelling vehicle to articulate the underlying tensions of the dissolution of the empire and the dwindling of Britain’s world power.31 In this study, Ferry to Hong Kong is taken as an imaginary battleground in Britain’s ideological war against the forewarned Communist intrusions into the Crown colony.

A sentiment of loss of power or status underpins the nostalgic undertones in Ferry to Hong Kong. Affectively, the picture wrestles with the pain and rueful memory of a cherished past that was disappearing and embraces “a romance with one’s own fantasy,” where memories of the past are conditioned by the exigencies of the present crisis moment.32 It clandestinely informs how the less powerful nation now has to come to terms with current political reality to account for the shifting international order in the postwar world. Drawing widely on primary sources as well as secondary accounts, including media responses upon the film’s release and individual memoirs of production, this study probes into the evolution of the story of a sinking ferry from the real-life story behind the film—its fictionalization—to the events of its cinematization as a Cold War allegory.

The essay also addresses recent Cold War scholarship that has placed due emphasis on American foreign policies and strategies in containing the spread of Communism in Asia where Hong Kong played a key role. Sangjoon Lee has examined the Asia Foundation (TAF), a US nongovernmental agency that established Hong Kong as the primary center of media production—especially newspapers, magazines, and movies—to promote non-Communist and counter-Communist materials for overseas Chinese audiences in Southeast Asia. The significance of Hong Kong was fundamentally attributed to its geographical, political, and economic weight among overseas Chinese communities.33 Poshek Fu also points out that TAF was deeply involved in the cultural warfare in Hong Kong, while motion pictures constituted a major instrument of propaganda—namely, the use of moving images to contain Communist influences in overseas Chinese communities.34 Alongside TAF, United States Information Services (USIS) played a fairly important role in producing Chinese-language pictures in Hong Kong and Southeast Asia to counter the cultural and political impacts of pro-Communist cinema in the regions.35

While the United States took Hong Kong as its major propaganda hub and was proactive in engaging anti-Communist politics in Asia, British officials sought to prevent overt propaganda efforts by both the United States and China; hence, they pursued a pragmatic tactic to sustain the “ ‘careful fiction’ of Hong Kong’s neutrality in the Cold War.”36 In domestic politics, the Hong Kong government tried to maintain political neutrality and a nonconfrontational approach vis-a-vis the threatening presence of Chinese Communists across the border. The colony was a “Cold War grey zone” where “certain communist activities were tolerated but rigidly confined by the colonial legal frame.”37 Britain preferred appeasement to confrontation in order to maintain the status quo of Hong Kong.

In this light, the British never deliberately released their own war films or propaganda works in Hong Kong. Even though the colony was formally under British rule, they did not seek to advance their political cause or interest in this fashion.38 A notable example is Michael Anderson’s Yangtse Incident: The Story of HMS Amethyst (aka Battle Hell) (1957). This was a British-made war movie that hailed British naval valor against the Communist Chinese army’s attack on the Yangtze in 1949. There is no obvious local release record of the film in Hong Kong.39

On April 19, 1949, the British frigate HMS Amethyst was ordered up the Yangtze River to act as a guardship for the British embassy in Nanjing during the Chinese civil war. The ship came under fire from Communist artillery batteries on the northern bank of the river, and it ran aground. After being held in custody for three months by the Communists, whose demand for a British apology was firmly refused, the ship, under the command of Lieutenant Commander John Kerans, fled 167 kilometers (103.7 miles) in the dark to rejoin the British fleet in Shanghai. During the incident seventeen members of the crew were killed and ten wounded.40 The frigate arrived in Hong Kong in August under a glare of publicity from the world’s press.

With the intention of reconstructing an official British version of the ship’s three-month ordeal, Yangtse Incident warranted official support from the foreign office, the navy, and the veterans who went through the actual warfare. The national production gave meticulous attention to historical and technical details. John Kerans himself was the film’s technical advisor, and the real HMS Amethyst was used in the film—in fact, it was even more badly damaged during the filming than in the real warfare. While the British propagandistic war film was “a smash for [the] home market” in Britain in 1957,41 it failed to charm American moviegoers or French critics at the Cannes Film Festival. The film received more attention at home than abroad.42 Foreign viewers, even those hailing from Britain’s close allies, greeted it with lackluster enthusiasm; they were not interested in the British national pride it conveyed. Even British commentator Derek Hill was annoyed at its nostalgia: “The British cinema seems to be looking backward because it lacks the courage or honesty to look forward. And nostalgia over past military exploits is even more dangerous than nervousness about the future.”43

Yangtse Incident emerged in an age of anxiety when the empire was falling apart. The war film did not fare well enough at the box office to recover its production costs. It premiered in 1957 in Britain, two years before A Ferry to Hong Kong was screened in Hong Kong. Indeed, Gilbert was associated with a dozen war films of the 1950s made to commemorate war heroes in “the people’s war.”44 Gilbert acknowledged that the war film genre arose because “after the war Britain was a very tired nation.” Already in the mid-1950s, war films were needed as “a kind of ego boost, a nostalgia for a time when Britain was great,” since economically the country was already falling behind the defeated nations of Germany and Japan.45

Major British studios like Rank were as much enmeshed in the ideological battle against Communist subversion as they were eager to vindicate British values. The British government between 1945 and 1965 sought to “integrate the cinema within the anti-communist and anti-Soviet propaganda campaign”; films were seen as “potentially active producers of political and ideological meanings.”46 Before producing A Ferry to Hong Kong, Rank specialized in “colonial war” films, which articulated British memories of World War II and the uprisings in its colonies.47 Nevertheless, public sentiment changed in Britain with the Suez Canal debacle and the ensuing demise of British and French colonial power.48 The humiliation at Suez meant to the world that the empire was no longer a source of political strength for Britain, which had already lost its leading position to the United States and the Soviet Union as the new global superpowers.49

By 1958, British viewers were fond of grimmer and more sober remembrances of the war. Two large-budget productions, Columbia’s The Bridge on the River Kwai (dir. David Lean, 1957) (starring William Holden) and Ealing’s Dunkirk (dir. Leslie Norman, 1958), topped the British box-office polls.50 These cinematic representations and audience responses could have been telling signs that “the British psyche under stress was vulnerable, volatile, and potentially unreliable.”51 These popular war films played a role in restoring Britain’s prestige in the context of British isolationism and anxiety and conveying the enduring theme of individuals fighting against impossible odds in the madness of war.52

But Gilbert’s film did not follow the popular success of The Bridge on the River Kwai. The British American war epic and adventure story mixed personal conflicts and ordeals with heroism, valor, and anti-war ideals. Ferry to Hong Kong, instead, was informed by the allegorical storytelling of the competing interests of Britain and America in screening Hong Kong to the (Western) world. Hollywood reacted favorably to American foreign policy orientations to produce imaginary pictures of America’s Cold War confrontations with Communist China and heroic adventures set in Hong Kong, such as Soldier of Fortune, where the British were nominally in power. Hollywood’s propaganda and soft power often counted on films that portrayed the Communists as a dark and barbaric force that infiltrated and threatened to destroy America.53 Ferry to Hong Kong tended to be more subtle and subdued. It conveyed sentiments of nostalgia and loss by portraying a descendant of the doomed Austrian and British empires as an exile condemned to a drifting shipboard life. It was a cinematic exemplar of British soft propaganda, a self-defensive but self-defeating eulogy of British national influence on Asian Cold War fronts. Yet, in competing with Hollywood, the British film was locked within the Western cinematographic cliché and Cold War Orientalism.

Cold War Coproduction and Orientalism

The long-forgotten event represented in Ferry to Hong Kong and British-American joint endeavors have been a subject of Cold War film studies in East Asia. Stephanie De Boer has examined Hong Kong-Japan coproductions made from the 1950s to the 1970s in the shadow of Japanese imperial occupation of the region and its postwar media legacy.54 Cinematic coproductions, as Erica Ka-yan Poon argues, was an intensified site of cultural battles for prestige in Cold War Asia.55 The event represented in Ferry to Hong Kong makes for a cogent case study of British film production liaising and vying with Hollywood and underlies both imperial nostalgia and colonial geopolitics in the 1950s.

The production of Ferry to Hong Kong cost half a million pounds (roughly $1,400,000) and marked Rank’s most ambitious project to date. Rank sought to compete with Hollywood studios by making increasingly lavish international coproductions with CinemaScope color photography to be sold at home and abroad. In the film’s early stages of planning, Rank’s chairman John Davis decided that “an exotic title, and American leading man and a continental director” were needed to make a successful international picture.56 The declining turnout at domestic theaters amid the competition from television,57 as well as the dominating presence of Hollywood, forced Rank to shift its strategy to produce only expensive blockbusters that “had international entertainment appeal” and could be “vigorously sold in foreign markets.”58

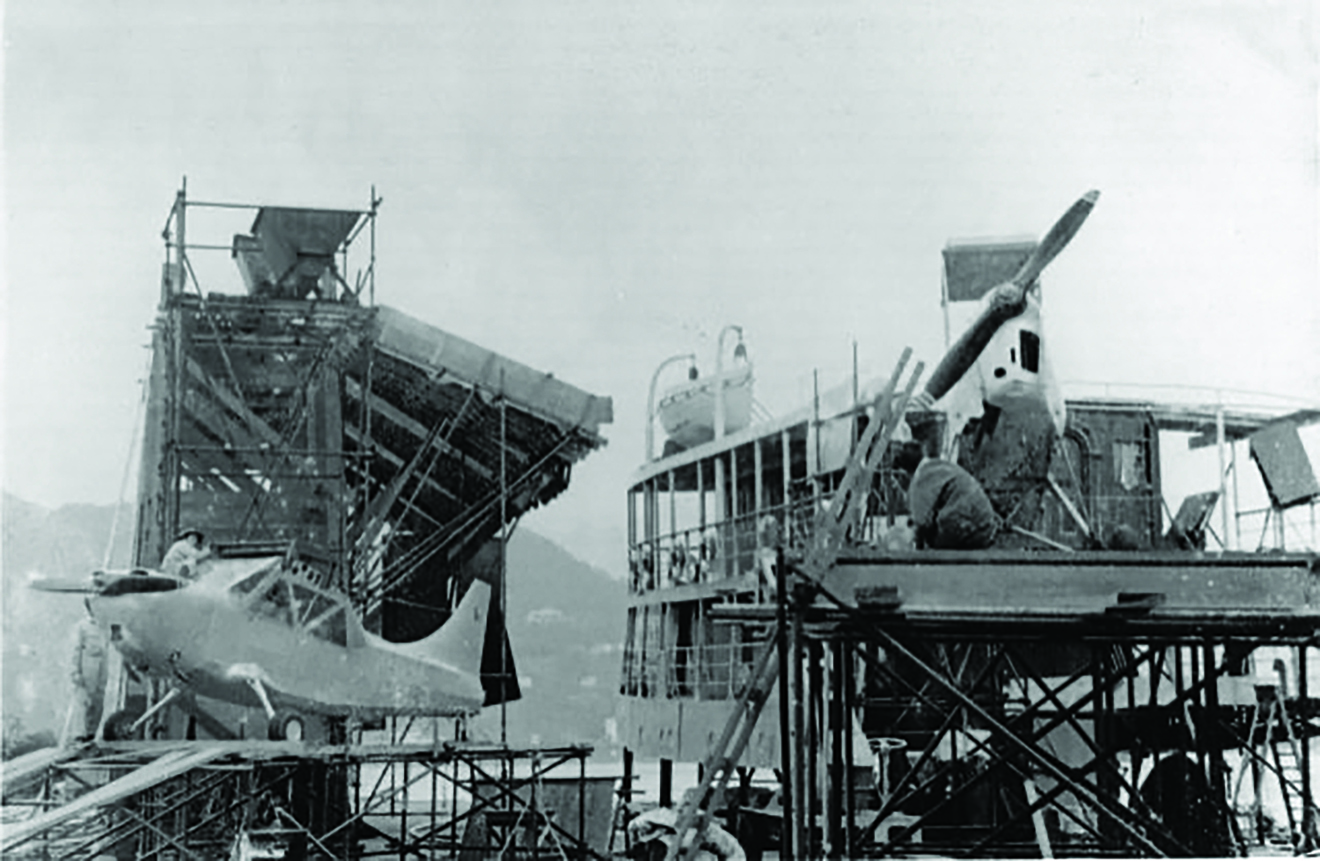

In terms of technology, Ferry to Hong Kong was the first of Rank’s feature films that adopted the US wide-screen format of CinemaScope. In Hong Kong, the production team converted a ferry into a paddle steamer specifically for moviemaking and hired local labor to build a studio stage and a crane for the CinemaScope camera.59 The on-location shooting had been widely practiced by Rank in (former) British colonies and the Commonwealth countries. The studio took full advantage of the newest Eastman Color innovation and lightweight cameras to make a range of films that exploited exotic locations.60 Made with the cosmopolitan conformity of international production, and invested with clichés of Orientalism (Chinese pirates, seductive dancers, thugs and gangsters, and devoted lovers in an underdeveloped Asian land), the film attempted to tap into the fascination of international audiences with the exotic and the spectacular in the 1950s.

In Hollywood’s most iconic Hong Kong films, Love Is a Many-Splendored Thing and The World of Suzie Wong, Hong Kong was generically featured as an exotic tropical locale where everyday life and local realities were sidelined to give way to exoticism and desire.61 The Cold War city was positioned as a place of refuge and a site of intercultural romance, where “a postwar American identity can be defined against an emerging Asian communism and the decay of European colonialism.”62 Love Is a Many-Splendored Thing opens with an astounding bird’s-eye view of Hong Kong Island and the harbor. The camera flies over and runs parallel to the waterfront until it cuts to a scene of urban streets and chaotic traffic, following an ambulance along Queen’s Road. Alfred Newman’s themed music sets the film’s affective tone with a sense of aloofness, whereas the lovers’ rendezvous occurs on an idyllic, grassy hilltop (shot in rural California), which is alienated from the urban density and social reality of Hong Kong. By comparison, The World of Suzie Wong has more engagement with Hong Kong’s urban locality, with scenes of the street markets and bars in Wanchai. The white male protagonist ventures into the shanty towns and witnesses the awful living conditions of Chinese refugees. The location shots of urban reality turn the exotic locale into a dystopic “lawless wilderness.”63

Recalling Hollywood’s dominant aesthetic temperament of location-shooting, the opening montage sequence of Ferry to Hong Kong follows the nomadic protagonist Conrad walking from the waterfront of western Kowloon to overcrowded market streets on Hong Kong Island, transitioning from day to night when Conrad passes by the Dragon nightclub with its clichéd oriental flavor (fig. 4).

Source: 20th Century Fox, Ferry to Hong Kong, 1960, printed still, IMDb, https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0052799/mediaviewer/rm572475904/.

The sequence is preceded by the juxtaposition of a modern steamship and a junk in the harbor as a stock phrase of East meets West. It cuts to a floating sampan as we see Conrad wake up and walk off to the shore. Dressed in a soiled suit and sleeping on the boat, covered by newspapers for warmth, Conrad is presented as a man without a home, a tramp on an outdoor adventure. The wide-screen format permits more lateral camera movement to capture Conrad’s walk among the boat people across the fishing shelter, showing the breadth of the physical space of the working-class neighborhood. His wandering is accompanied by a soundtrack of Nanyin (Southern tunes) singing, the local Cantonese vernacular music performed by blind singers to entertain lower-class people. The establishing sequence is followed by a shot of the sunset over the sea and the nightclub in a bright neon light, framed and illuminated by the CinemaScope and Eastman Color to transform the shore footage into an oriental spectacle. “Photographed in color entirely in the Hong Kong area,” a critic noted, “the Twentieth Century-Fox release is drenched in exotic atmosphere. It fairly simmers as the opening credits come on.”64

The Orientalism of Ferry to Hong Kong extended beyond the movie screen to real-life cinematic circles and social gatherings in London. The film was promoted in its British homeland as a blockbuster, “one of the most ambitious British films for years.”65 It received a spectacular world premiere in London attended by one thousand guests on July 2, 1959 (fig. 5).66

Source: Ferry to Hong Kong (1959) Premierenfoto 3, 1959, photograph. Curt Jürgens: The Bequest, Deutsches Filminstitut & Filmmuseum, https://curdjuergens.deutsches-filminstitut.de/nachlass/ferry-to-hong-kong-1959-premierenfoto-3/. Reproduced by permission of Deutsches Filminstitut & Filmmuseum.

Popular media compared the extravaganza to the producer Mike Todd’s grand premiere party for Around the World in 80 Days (dir. Michael Anderson, 1956). The glamorous oriental-themed party greeted the guests with fireworks and spectacles.67 A few celebrities traveled on sampan boats across the Thames River to attend the party while Jurgens and Syms took rickshaw rides (fig. 6).68

Source: Ferry to Hong Kong (1959) Premierenfoto 1, 1959, photograph. Curt Jürgens: The Bequest, Deutsches Filminstitut & Filmmuseum, https://curdjuergens.deutsches-filminstitut.de/nachlass/ferry-to-hong-kong-1959-premierenfoto-1/. Reproduced by permission of Deutsches Filminstitut & Filmmuseum.

In a cinematic setting glitzed up by Chinese lanterns and dragon icons, they enjoyed a sumptuous buffet of exotic Chinese dishes, such as honeyed grasshoppers, served with chopsticks and delivered by ethnic Chinese girls in cheongsams (fig. 7).

Source: Ferry to Hong Kong (1959) Curd und Simone privat 8, 1959, photograph. Curt Jürgens: The Bequest, Deutsches Filminstitut & Filmmuseum, https://curdjuergens.deutsches-filminstitut.de/nachlass/ferry-to-hong-kong-1959-curd-und-simone-privat-8/. Reproduced by permission of Deutsches Filminstitut & Filmmuseum.

The guests were entertained with variety shows featuring Chinese acrobats, dragon-dance performers, jugglers, fortune-tellers, and an orchestra band.69

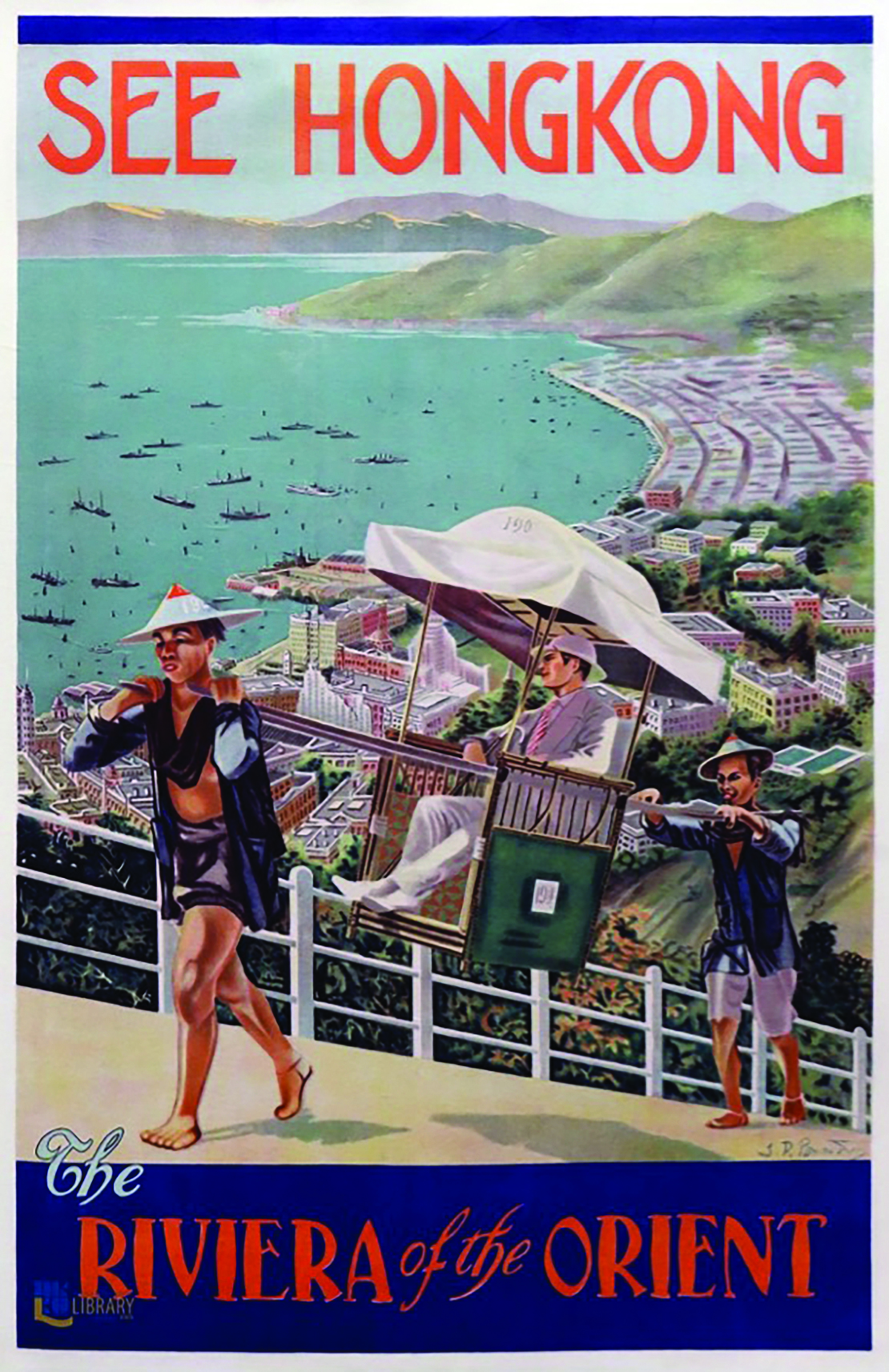

In Hong Kong, the film stars had no qualms about showing their (self-)Orientalist appreciation of the Chinese lifestyle in the colony to Anglophone media, which followed their sightseeing tours when they were not filming. Jurgens and Syms put on Chinese clothing, collected Chinese antiques, and tried outlandish Cantonese foods like snake soups and hot pots.70 Jurgens and his spouse Simone Bicheron visited the Precious Lotus Temple on Lantau Island, expressing amazement at the sedan chair ride as they were carried uphill by Chinese coolies (fig. 8).71

Source: Ferry to Hong Kong (1959) Curd und Simone Privat 13, circa 1959, photograph. Curt Jürgens: The Bequest, Deutsches Filminstitut & Filmmuseum, https://curdjuergens.deutsches-filminstitut.de/nachlass/ferry-to-hong-kong-1959-curd-und-simone-privat-13/. Reproduced by permission of Deutsches Filminstitut & Filmmuseum.

The stars marveled at their tourist excursions as they experienced and imagined how upper-class expatriates lived in Hong Kong (fig. 10).72

Source: S. D. Panaiotaky, See HongKong, the Riviera of the Orient, circa 1935, poster, color, 105 cm. x 67 cm. on cloth board. Hong Kong Travel Association, Hong Kong, in Hong Kong Baptist University Library Art Collections, https://bcc.lib.hkbu.edu.hk/artcollection/91512504h757t2/. Image courtesy of Hong Kong Baptist University Library.

The zealous coverage in the English media of the stars’ tourist activities revealed Cold War Hong Kong’s status not only as a favorite film location for Western—predominantly Hollywood—moviemakers but also as a popular tourist desination in Asia. This was particularly true of Americans, who made up the largest national group of foreign visitors. Like a host of foreigner filmmakers before him who made trips to the city to shoot travelogue footage of their exotic Orient,73 Welles took the opportunity to privately obtain movie footage of the city and documented local customs like Chinese weddings and funerals.74 Postwar Hong Kong saw a ten-fold surge in tourists from the 1950s to 1960s, making the city the second most popular destination in Asia, after Japan.75 It was American businesmen and executives who played an important role in promoting Hong Kong as Asia’s tourist hub.76 From the Korean War (1950–1953) to the escalation of the Vietnam War in the 1960s, the US military and the Seventh Fleet also used Hong Kong as a liberty port as well as a “rest and recreation” (R&R) center for thousands of American soliders and sailors.77 American tourism and Hollywood blockbusters were thus inextricably related to forging the spectacle of Hong Kong to be imagined and consumed by global visitors and by viewers on the screen.

In addition, Asia had seen rapid economic growth in the early 1950s and become an expanding market for international motion pictures: “The natives are particularly interested in Hollywood films.”78 An exemplary popular success was The World of Suzie Wong, adapted by American producer Ray Stark from a best-selling novel by British author Richard Mason. Both the fictional and cinematic storytelling infamously propagated foreign images of Hong Kong/Wanchai as the exotic “world of Suzie Wong,” with girlie bars, dance halls, brothels, and restaurants catering to foreign visitors and sailors.79

Released only one year apart, both The World of Suzie Wong and A Ferry to Hong Kong shared Hollywood’s narrative interest and commercial drive to popularize the tourist gaze on the screen. With the advantage of on-the-spot shooting, the movies could visualize the picturesque environments in color and sound, evoking an ethnic charm of working-class crowds hustling and bustling in street markets and the boat people living on waterfront shelters. But the British film could not compare with the success of Hollywood’s tale of Suzie Wong, which fueled the popular American fantasy of the “white knight,” a role assumed by a Caucasian male lover to safeguard his Asian girl.80 Sylvia Syms, who starred in both films, plays a wealthy upper-class British banker’s daughter, Kay O’Neill, in The World of Suzie Wong. A condescending British lady who despises the intimate relationship between her American painter friend Robert Lomax (William Holden) and his poor Asian lover, Suzie (Nancy Kwan), she acts as a romantic foil. Not only does the American hero save Suzie from the debris of war in poverty-stricken Hong Kong/Asia, but he also releases her from the grip of British violence and racism by physically fighting a British sailor who harasses Suzie and rejecting the temptations of O’Neill’s patronage. Robert shows his American distaste for British hierarchy and for business. By portraying an interracial love affair, the Hollywood film hides its own racism and exoticism.

In Cold War Orientalism: Asia in the Middlebrow Imagination, 1945–1961, Christina Klein explains how American middlebrow cultural products such as films, stage plays, magazines, and travel writings translated US foreign policy and shaped American audiences’ belief in the role of the United States in Cold War Asia as the defender of democracy and freedom regardless of race and class.81 Klein argues that American middlebrow fiction and films functioned to reshape its Orientalism to propel the myth of America-Asia bonding in a consolidation of the Free World in Asia.82 Similarly, The World of Suzie Wong was ideologically important for disseminating American values of freedom to audiences.

In Ferry to Hong Kong, however, the romance of the Caucasian lovers Ferrers and Conrad could not excite the Orientalist imagination of American viewers. Rather, it was the understated lead Jurgens who, as the fugitive, gave the film reflexive depth with respect to British self-image and its identity crisis. The film changes the novel’s American protagonist Clarry Mercer to British Austrian antihero Conrad. The name no doubt recalls Joseph Conrad’s characters and their misadventures in the “primitive” lands of British colonies. In Heart of Darkness (1899), Marlow’s mythical journey up the Congo River relates to his quest for the self; he is caught between the “civilized” and “uncivilized” worlds. In the film, Conrad in his uninvited excursions is met with contempt and hatred by his civilized British compatriots on board. A snobbish old lady in Victorian dress casts a derogatory look at Conrad, who cannot pay the travel fare at the entrance, when boarding the upper deck. Captain Hart despises him as a drunk and brawler. Calling Conrad “human refuse,” Hart throws him down to the lower deck with the Chinese passengers. The outcast’s experience offers viewers a glimpse of the inequality of different social classes in colonial society as reflected on the boat. By colonial law, Conrad is an “undesirable alien” expelled by the British Hong Kong police and must obey official instructions that refuse his entry to Hong Kong and Macau.

The film is inescapably stuck in a double bind between its (self-)mockery of British class society and imperialism and its Cold War Orientalism. Like Marlow’s voyage of self-discovery in Heart of Darkness,83 Conrad’s exilic journey in Ferry to Hong Kong illuminates the truth through the eyes of the underdog hero: imperialism is only a shadowy presence. But the ideological battle for hearts and minds dictates the film’s anti-Communist storytelling. The climax is freighted with thrilling action when storms and rains thrust the vessel into the darkness of the South China Sea, where pirates board the ship to rob the wealthy passengers. These uncivilized natives are none other than the Chinese Communists, who plunder the ferry. Conrad shines in his chivalric valor by heroically ridding the stranded ferry of Chinese pirates to save the passengers. Aided by Captain Hart and the crew, Conrad overcomes the pirates and comes close to steering the storm-battered ferry back to port, but it sinks in Hong Kong harbor (fig. 10).

Source: H. K. Watt, Ferry to Hong Kong Film, 1958, photograph. Archives of Hong Kong Historical Aircraft Association, https://gwulo.com/atom/13776. Courtesy of the Hong Kong Historical Aircraft Association.

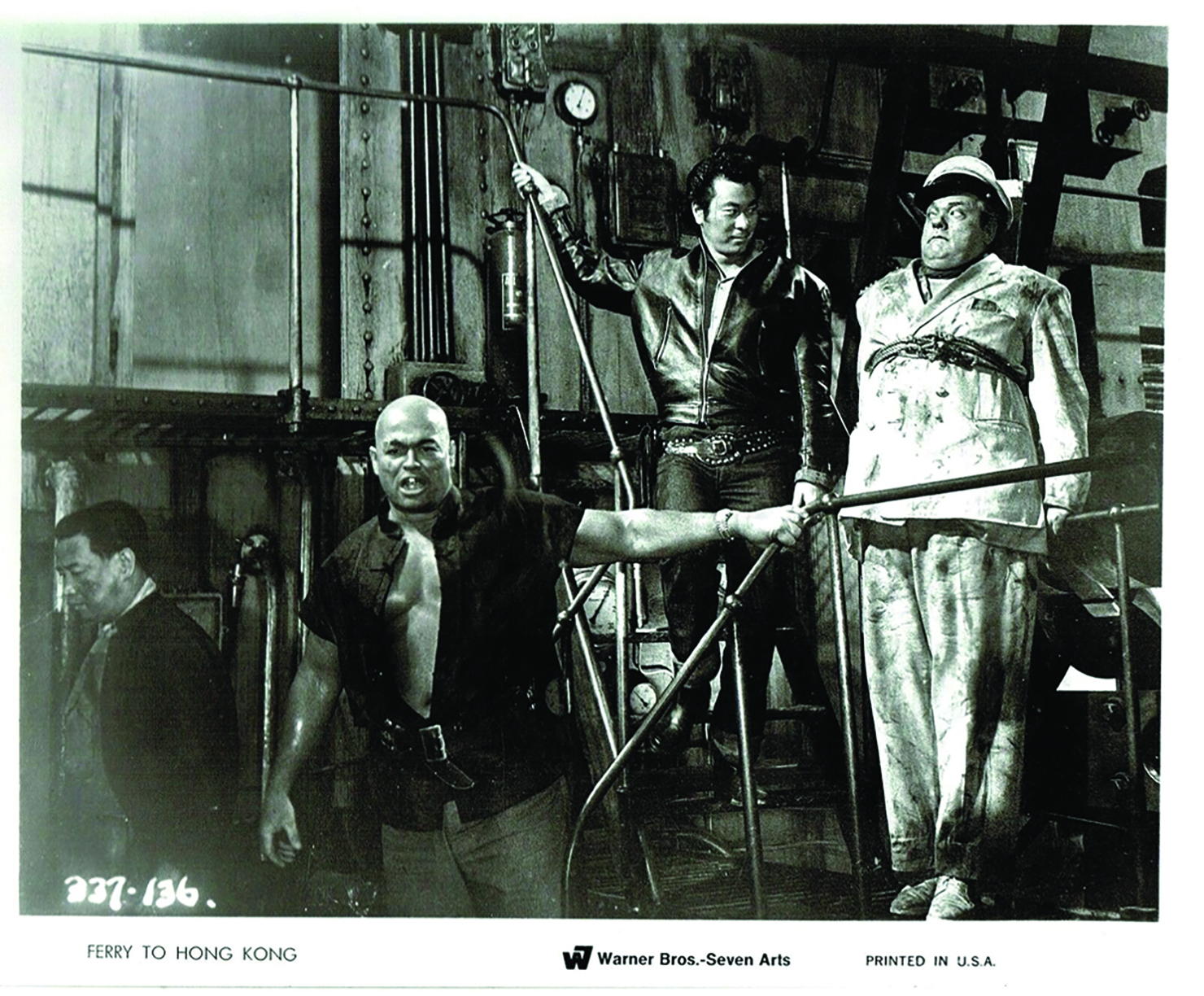

Hong Kong actor Roy Chiao plays the Americanized Chinese Johnny Sing-Up, a black-leather-jacket and blue-jean-clad Elvis-styled rogue who teams up with Master Yen, the bald-headed, brutal pirate leader. Johnny describes his partner to the passengers as “a vulgar man of action,” but “he is civilized like me” (fig. 11).

Source: Warner Brothers and Seven Arts, Ferry to Hong Kong, printed still. moondollar007 on eBay, https://www.ebay.com/itm/174206463075.

This understated line might remind us mockingly of how similar the violent looting by uncivilized pirates really is to the taking of territory by civilized colonial masters.

Chiao’s participation in the Anglo-American blockbuster attracted much Chinese media attention. In an interview published in International Screen, the Chinese flagship magazine of Cathay-MP&GI (Motion Picture & General Investment), he attempted to alleviate the charge of racism made against the film. Chiao told the reporter that he had convinced Gilbert to modify provocative dialogue to avoid racial discrimination against Chinese. Welles originally had a line, “I would rather die than be caught giving out this ferry to you ‘Dirty Chinese.’ ” On Chiao’s advice, “Dirty Chinese” was changed to “Dirty Oriental.”84 (Today, both terms are equally racial slurs.)

For Marchetti, the root of Hollywood’s representation of Asians can be traced back to the “yellow peril” in which these “irresistible, dark, occult forces of the East” will overpower and destroy the Western civilizations, cultures, and values.85 Ferry to Hong Kong smacks of blatant racism comparable to Hollywood’s in depicting Chinese as hoodlums and looters. In 1960, it might seem early to be calling out Hollywood’s stock representation of Chinese pirates.86 But Chinese commentators were already furious at the film’s Hollywood-style Orientalist gaze. A critic writing for Chinese Student Weekly denounced the film’s overlooking of Hong Kong’s urban modernity as the camera scouted only for exotic scenes.87 The leftist Ta Kung Pao lamented the portrayal of Chinese as violent pirates or more generally as ignorant, unflattering, and primitive subjects. The film inaccurately conveyed an impression of an underdeveloped city with messy traffic and an ineffective police force.88 Even expatriate viewers in Hong Kong complained about the spectacle of the harbor and the waterfront showcasing backwardness, disorder, and crime: “The only onshore impression given of Hong Kong is a place of drunken brawls in bars full of doubtful girls frequented by sailors of many countries.” The sinking of the Fat Annie in Victoria Harbor surrounded by sampans “gives a particular insulting impression of Hong Kong.”89 The film’s stereotypical depiction of the pirates as barbaric subjects is aligned with the Cold War’s “siege mentality” and “Red Scare,” in which the Communist enemy is treated as a dark force poised to invade the Free World.90

The visual-ethnographic representation of Macau was outrageous to Chinese critics too. The scenic beauty of Macau was inauthentic, and the place where it was filmed was “worse than every postcard in the market.”91 The camera featured a funeral procession. The scene was choreographed with Indigenous Chinese people dressed in archaic Qing dynasty attire to appeal to the Western preconception of premodern China. In real life, Welles took his own camera to film documentaries in Macau, including a Chinese funeral.92 Adding to the thrill of the actual filming in Macau was a potential confrontation of the crew with angry Communist supporters when they did location shooting close to the Chinese (Zhuhai) border. Communist agitators across the shore warned the crew to keep off Chinese territory, waving red flags and playing propaganda songs at Gilbert’s teammates. In response, the director broadcasted a humorous speech and played jazz music. Gilbert yelled at the Communist activists across the shore: “If you have to arrest someone, go for my cinematographer!”93

In the same year when Ferry to Hong Kong began its world premiere in London and Hong Kong, the MP&GI-produced Mandarin picture Air Hostess (1959) was released in Hong Kong, starring Chiao and Grace Chang, a talented Hong Kong Chinese movie star, singer, and popular idol. MP&GI followed the Hollywood studio system and vertical integration of production, nurturing its movie stars and churning out romantic comedies and urban dramas often filled with North American pop music and dance numbers such as jazz, cha-cha, and mambo. A big-budget film shot in Eastman Color, Air Hostess was shot like a travelogue, showcasing the exotic beauty and modernity of the Asian cities of Hong Kong, Singapore, Bangkok, and Taipei. The cinematic tourism of Asian and Southeast Asian locations outside the People’s Republic of China (PRC) orbit created an inter-Asian, pan-Chinese imagined community free from the reach of Communism and celebrated the US-supported modernity of Taiwan as an exemplar of Free China. Poshek Fu claims that Air Hostess was one of the most significant Hong Kong Cold War movies.94 The high-cost, high-tech, star-studded transnational production served ideologically to highlight the desire of Asian regions for technomodernity (air travel and mobility) and a good life of capitalist prosperity for pan-Chinese societies outside of mainland China.

While MP&GI exploited the screen success and widespread idolization of its stars to promote the tourist gaze of Asian modernity for pan-Chinese audiences, the Asian actors were marginalized in Hollywood and Anglo-American cinema. Chang was relegated to a minor, uncredited role as a sampan girl in Soldier of Fortune. Ferry to Hong Kong denigrated Chiao by casting him as a small-time rogue. It did not attend to ethnic authenticity of its Chinese characters or care very much about taking a share of the Asian market. The film was a journey of British Orientalism and cinematic tourism in search of a lost prestige, as well as an exercise in self-portraiture when faced with the oriental Other.

Besides MP&GI’s coverage of Chiao’s role in Ferry to Hong Kong, Taiwan’s Central Daily News and United Daily News applauded the Hong Kong actor for working with international stars; it brought prestige, regardless of the fact that he played an Asian villain. He was called “the actor of our country (China)” (我國演員) and the “actor of China” (中國演員).95 The claim to “China” by the Taiwan presses unabashedly unveiled the feud between the Guomindang (GMD) regime in Taiwan and the PRC over being the legitimate representative of China in the 1960s. In Hong Kong, the British authorities were cautious to avoid any possibility of a “Two Chinas” situation and strove to prevent the Taiwan question from triggering a hot war in East Asia.96 In the local cinema, censors were instructed to closely examine all Chinese-language pictures produced in mainland China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong and to “bear in mind particular sensitivities on both sides of the camp to implied recognition of ‘Two Chinas.’ ”97

The Taiwanese press was spinning the story to suit its own political agenda. Its claim of legitimacy of “China” indicated how Cold War geopolitics played out in transnational production. Indeed, the corporate strategies of MP&GI meshed with Cold War cultural politics. MP&GI’s Malayan Chinese owner, Dato Loke Wan Tho, was involved in the politics of anti-Communism and “identified with ‘Free China’–Taiwan—as the custodian of Chinese culture and thereby the only legitimate Chinese government.”98 When anti-Communist messages were taboo under Hong Kong’s censorship, MP&GI turned to the Hollywood model to produce urbanized romances and narratives of Free Asia modernity. Hollywood has become a channel for exporting American capitalism, democratic freedom, and modern-life culture. MP&GI then promoted one of its biggest movie stars, Grace Chang, to American television.99 Yet, this regional Asian cinematic pursuit of modernity was juxtaposed with the tradition of Orientalism. As mentioned, behind the filming and screening event of A Ferry to Hong Kong, the involvement of Chinese/Asian stars in Anglo-American big-budget productions concealed the Cold War geopolitics and the lopsided power dynamics of Hollywood and Asian cinema.

Coda: Sinking Boat and Floating City

Ferry to Hong Kong only played in Hong Kong’s cinemas for ten days, starting on the last day of 1959.100 It failed to sell the British story to American audiences. The picture was belatedly screened across the United States in 1961 and was considered “so terrible that managers refused first-run booking.”101 One US exhibitor called the film a complete disaster: “Two real good actors but couldn’t get any business. Played one day to a loss.”102 Even British scholars have considered the film to be “totally unbelievable.” Unsurprisingly, “it was quickly shunted into oblivion.”103 Costing half a million pounds (roughly $1.4 million), and with an all-star extravaganza, the international production split at the seams as the British and American partners quarreled.

The film was a dire flop across the globe not only because of the botched Anglo-American cooperation but also because the demands of entertainment and propaganda clashed. They fell out of place in the film’s storytelling. How can a film inform and instruct an audience given the yearning for romance and spectacle, and above all for a respite from politics, in mass entertainments? The romantic and melodramatic plots of the British film proved fruitless in appealing to an international audience; it did not do particularly well even at home, receiving terrible reviews. Gilbert would later direct three James Bond movies: You Only Live Twice (1967), The Spy Who Loved Me (1977), and Moonraker (1979). They were internationally more popular and successful as Cold War espionage cinema. Ferry to Hong Kong might well have failed to become a popular success at home and abroad despite a stellar cast and spectacular promotions. The film could be seen as a British cultural-diplomatic response to reestablish through cinematic soft power national assurance on the Cold War international stage.

Situated at the end of the 1950s, Ferry to Hong Kong invites a symptomatic reading. It tells how Conrad saves the day, overpowering the Communist intruders, and jumps to rescue the sinking vessel teeming with helpless Chinese passengers. Betraying the traits of arrogance, callousness, and snobbery, Captain Hart is a stand-in for the pragmatic colonial mentality, as he hesitates to save the people on the stranded junks.104 Conrad, the ordinary man with a bruised soul, reacts without hesitation to the most fateful conditions. He supersedes the morally weak captain to call for a rescue of the drifting survivors. The downtrodden loner is eventually recast as the “colonial freedom fighter”—with the charisma of “audacity, stoicism, unflappability, good manners, a sense of duty, and an ability to command” to defeat the Communist intruders.105

Ferry to Hong Kong is more than an adventurous picture of a vagabond who tries to redeem himself and salvage self-respect and a future from the wreck as the ferry goes down into the sea. At the end, Conrad chooses to depart from Ferrers after their romantic adventure, but he promises her school children that he is going to “fight the dragon” before coming back to “claim the princess.” Conrad uses the medieval tale of the chivalric knight slaying the “dragon” to avow his moral mission to continue the fight against Dragon China. The romantic narrative is sacrificed to make way for the film’s political intent. The antihero becomes the last British white knight of the fallen empire—with its lost transnational dominance and international supremacy—who struggles to regenerate the British position as the guardian of the Free World with heroism, nostalgia, and anxiety. But despite the denigration of imperialist ambition on the part of the protagonist, the film indulges in an inconspicuous form of imperial nostalgia by evoking the thrill of a battle between good and evil, the glamour of the gentleman-hero, and exotic far-flung locations

The analogy of the sinking ferry as a broken empire may not be easily traced in this transnational production packaged as a suspense trip and romance. However, the screen adaptation makes a pivotal change to the novel, in which the Fat Annie survived the raids and storms. As the protagonist Clarry in the novel ruminates on the battered ferryboat:

The military and political undertones could not be more obvious in this passage. The Fat Annie is not crushed by the (Communist Chinese) enemy: “She’ll never sink, the devil won’t have her!” On the screen, Captain Hart and Conrad on the lifeboat witness the vessel dipping slowly into the sea in a wide-angle shot. Just a moment before, Hart still wanted to keep his ship afloat: “Come on, Annie. Come on, old lady,” Hart declares. “This is still my ship!” We are aware of the captain’s dignified and tragic tone and understand why Welles’s somewhat comic performance could have spoiled the film throughout. The ending dwells on the moment of the sinking vessel and the image of abject defeat. “She’s lived quite a whole of our life,” Hart moans, noting their shared fate with the sunken ferry: “Eternal trying—you [Conrad], me, and the Fat Annie.” The loss of the anthropomorphized ship is endowed with connotations of self-sacrifice and the decline of the empire.He [Clarry] stood on the deck and took a long, faintly startled look at the Fat Annie, wondering for the first time—now that it was safe to wonder—how she had survived. She glimmered greyly, crusted with salt all the way down from the dented smoke-stack to the saloon. She looked as though she had just emerged exhaustedly from a naval battle, with bent stanchions, battered bulwarks, an appalling scum of debris covering her deck.106

The emblem of the sinking ship is intrinsic to the postwar naval films of Britain, an island nation and a bygone maritime empire. Jonathan Rayner identifies the status of the warship in naval films as the symbol of the nation and explains how the depiction of its loss appears dangerously defeatist to British self-esteem.107 The sinking boat imagery serves as a traumatic device to recall British naval war stories and retell romantic and narcissistic tales of British gallantry and international influence in global politics. The scene of Conrad saving the Chinese refugees on abandoned junks to board the ferry could easily remind British viewers of Dunkirk, a film about the historical evacuation of allied soldiers from northern France in World War II. The two British films were made just one year apart.108 Dunkirk, a gigantic retreat if not defeat, has become a wartime icon and national event through cinematization, in which the sea is central. This would account for Rank’s choice of the novel to narrate the British Hong Kong journey as a watered-down naval story instead of a story on land.

Whereas the in-between territory of the China Sea connotes the underground routes of pirates, smugglers, and refugees, the drifting Fat Annie is overloaded with significations of the Cold War city. The mass exodus of Chinese refugees fleeing Communist China to colonial Hong Kong in the early 1950s brought serious social and economic problems to the city as well as a strong propaganda advantage for the Free World.109 It forced the colonial government to impose border controls to stem the huge flow of illegal migrants. Cinematically, the floating ferry at sea is reflective of the class and power structure of Hong Kong society (Westerners and rich Chinese on the upper deck; Chinese commoners, coolies, and a disgraced Conrad on the lower deck) and emblematic of the precarity of Hong Kong as the floating city embattled in its Cold War dilemmas. In a nostalgic and eulogistic mode, the film projects images of benign British colonials. Ferrers, the schoolteacher, behaves like a missionary, taking care of her well-educated diasporic Chinese students. Conrad shows his respect for the coffin-carrying fellow passengers, aghast at the cruelty of the (Communist) pirates who throw the coffin, with the body inside, into the sea.

A neglected cinematic fragment, Ferry to Hong Kong offers a sound testimony of British sentiments and ideology vis-a-vis the geopolitics between Hong Kong, Britain, and Communist China during the Cold War. Postwar Hong Kong was becoming prosperous as well as precarious. A Chinese takeover of the city, as colonial officials and merchants had realized much earlier in the 1950s, seemed distant but was doomed to happen: “They feel that their island is on Red China’s time-table.”110 Fast forward to the late 1980s, in the run-up to Hong Kong’s transfer of sovereignty in 1997, the moral question remained for British intellectuals: “Should the British government hand over a city of six million people, among whom a large number are British subjects, to a regime not known for its tolerance of individual liberty and political dissent?”111

History may not repeat itself, but sometimes it rhymes.112 The former colonial regime has now been receiving up to one hundred thousand Hong Kong residents who sought to escape from Communist rule under the “one country, two systems” policy.113 The modern-day Conrad resumes his moral responsibility with pragmatism, humanitarianism, and imperial nostalgia. The untold story of A Ferry to Hong Kong still resonates with our current anxiety and reiterates the unknown nature of the future. It is—for sure—to be continued.

Acknowledgments

This article was written with the support of the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong. I am deeply grateful to Lee Sing Chak, Kuan Chee Wah, and Jessica Siu-yin Yeung for their research assistance. I am indebted to Isabel Galwey, Hazel Shu Chen, Mike Ingham, and my anonymous reviewers for their comments.

Notes

- A. H. Weiler, “Brand-New ‘Scent’ on the Todd Roster–Kelly’s ‘Gentleman’–Addenda,” New York Times, September 28, 1958; “Orson Welles Here to Make Picture: Will Play Part of Skipper in Ferry to Hongkong: Staying Four Months,” South China Morning Post, November 17, 1958, 6. ⮭

- Henry R. Lieberman, “Ferry Voyager Leaves Hong Kong After 23, 680-Mile Trip to Nowhere: O’Brien’s 315-Day Yo-Yoing Is Ended as Police See Him Off on Plane,” New York Times, July 31, 1953; and Daniel Hånberg Alonso, “The Man without a Country,” Medium, July 8, 2020, https://medium.com/@danielhanberg/the-man-without-a-country-df0044dddd09. ⮭

- Simon Kent, Ferry to Hongkong (London: Hutchinson, 1958). ⮭

- Sue Harper and Vincent Porter, British Cinema in the 1950s: The Decline of Deference (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 52–55. ⮭

- “Orson Welles in a Film Typhoon: Ferry to Hong Kong,” Times, July 1, 1959; “London Critics Flay Orson Welles,” China Mail, July 3, 1959. ⮭

- John Howard Reid, 150 Finest Films of the Fifties (Morrisville: Lulu.com, 2015), 123. ⮭

- “Flashes Review: Ferry to Hong Kong,” Boxoffice, May 8, 1961, https://lantern.mediahist.org/catalog/boxofficeaprjun179boxo_0252. ⮭

- Kirsty Young, interview with Lewis Gilbert, prod. Leanne Buckle, BBC Radio 4, June 25, 2010, https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00sqkg8. ⮭

- Lewis Gilbert, All My Flashbacks: The Autobiography of Lewis Gilbert (London: Reynolds & Hearn, 2010), 187–96. ⮭

- Chris Welles Feder, In My Father’s Shadow: A Daughter Remembers Orson Welles (Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books, 2011), 190–200; Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich, This Is Orson Welles (New York: HarperCollins, 1993), 264–66; Samuel Wilson, “A Wild World of Cinema: Ferry to Hong Kong (1959),” MONDO 70, December 15, 2017, https://mondo70.blogspot.com/2017/12/ferry-to-hong-kong-1959.html. ⮭

- Quoted from Reid, 150 Finest Films of the Fifties, 122. ⮭

- Tony Sloman, interview with Lewis Gilbert, National Film Theatre Audiotape, October 23, 1995, quoted from Harper and Porter, British Cinema in the 1950s, 55. ⮭

- Gilbert, All My Flashbacks, 189–91. ⮭

- Welles later revealed in an interview after the filming that he thought Ferry to Hong Kong had proved to be “a disappointing B movie,” one which “he wished to put out of his mind as soon as possible.” Peter Moss, No Babylon: A Hong Kong Scrapbook (New York: iUniverse, 2006), 142. ⮭

- Graham Greene wrote the screenplay for The Third Man, and his creation of the Harry Lime character was said to have been inspired by Kim Philby, the notorious British double agent for the Soviet Union. There is no question that Greene knew Philby, as they had worked in the same unit for British wartime intelligence. Tony Shaw believes that “Philby undoubtedly provided inspiration for the persona of Harry Lime.” See Shaw, British Cinema and the Cold War: The State, Propaganda and Consensus (London: I. B. Tauris, 2001), 28. The unmasking of Philby as a Soviet “mole” inside MI6 provided the model for John le Carré’s most famous espionage novel, Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy (1974). ⮭

- David Lewin, “Third Man in Hong Kong Part 1: Crime Is Inscrutable,” China Mail, February 28, 1959. Welles was curious to know about the business of smuggling “human snakes” (gang slang for illegal immigrants) from China to Hong Kong. ⮭

- “Harry Lime has gone up in the world,” Welles told his interviewer. “He would still be making fast money: from smuggling illegal immigrants from Communist China … from dealing with dope … from trafficking in gold.” Lewin, “Third Man in Hong Kong Part 1.” ⮭

- Chi-Kwan Mark, “A Reward for Good Behavior in the Cold War: Bargaining over the Defense of Hong Kong, 1949–1957,” International History Review 22, no. 4 (December 2000): 837. ⮭

- Chi-Kwan Mark, Hong Kong and the Cold War: Anglo-American Relations, 1949–1957 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2004), 6. ⮭

- For Hong Kong’s unique Cold War experience in maintaining a pragmatic balance between China, Britain, and the United States, see Priscilla Roberts, “Cold War Hong Kong: Juggling Opposition Forces and Identities,” in Hong Kong in the Cold War, eds. Roberts and John M. Carroll (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2016), 26–59. ⮭

- For an analysis of Soldier of Fortune, see Thomas Y. T. Luk, “Hollywood’s Hong Kong: Cold War Imagery and Urban Transformation in Edward Dmytryk’s Soldier of Fortune,” Visual Anthropology, no. 27 (2014): 138–48; Paul Cornelius and Douglas Rhein, “Soldier of Fortune and the Expatriate Adventure Film,” Quarterly Review of Film and Video, March 7, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1080/10509208.2021.1891832. ⮭

- Lewin, “Third Man in Hong Kong Part 1.” ⮭

- Christopher Sutton, Britain’s Cold War in Cyprus and Hong Kong: A Conflict of Empires (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), 152. ⮭

- Quoted from Steven Hugh Lee, Outposts of Empire: Korea, Vietnam, and the Origins of the Cold War in Asia, 1949–1954 (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1995), 18. ⮭

- Alexander Grantham, Via Ports: From Hong Kong to Hong Kong (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1965), 139. ⮭

- Quoted from Lee, Outposts of Empire, 18. ⮭

- Harper and Porter, British Cinema in the 1950s, 45. ⮭

- Reed later directed The Man Between (1953), which captured the demoralization of life in war-torn Berlin. But location shooting was barred in East Germany, and Reed could not replicate the visual virtuosity of The Third Man. Shaw, British Cinema and the Cold War, 70–74. ⮭

- Lynette Carpenter, “ ‘I Never Knew the Old Vienna’: Cold War Politics and The Third Man,” Film Criticism 3, no. 1 (1978): 28–29. After the defeat of Nazi Germany, Austria was subdivided into four occupation zones and jointly administered by the Soviet Union, the United States, the United Kingdom, and France. In the film, Vienna is a microcosm of international politics. The story is told from a British perspective (from producer Alexander Korda, director Carol Reed, and screenwriter Graham Green) and focuses on the precariousness of Vienna—and Europe—in the immediate postwar period: they could fall into the hands of the Soviet Union. ⮭

- Patricia M. E. Lorcin, “Imperial Nostalgia; Colonial Nostalgia: Differences of Theory, Similarities of Practice?” Historical Reflections 39, no. 3 (2013): 107. ⮭

- For a discussion of postwar British cinema and imperial nostalgia, see Stuart Ward, “Introduction,” in British Culture and the End of Empire, ed. Ward (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2001), 1–20. ⮭

- Svetlana Boym, The Future of Nostalgia (New York: Basic Books, 2001), xiii–xvi. ⮭

- Sangjoon Lee, “Creating an Anti-Communist Motion Picture Producers’ Network in Asia: The Asia Foundation, Asia Pictures, and the Korean Motion Picture Cultural Association,” Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 37, no. 3 (2017): 517–38. ⮭

- Poshek Fu, “Entertainment and Propaganda: Hong Kong Cinema and Asia’s Cold War,” in The Cold War and Asian Cinemas, eds. Fu and Man-Fung Yip (New York: Routledge, 2019), 238–62. ⮭

- For the role of USIS in propagating anti-Communist literature, see Kenny K. K. Ng, “Soft-Boiled Anti-Communist Romance at the Crossroads of Hong Kong, China, and Southeast Asia,” in Chineseness and the Cold War: Contested Cultures and Diaspora in Southeast Asia and Hong Kong, eds. Jeremy E. Taylor and Lanjun Xu (New York: Routledge, 2021), 94–109. ⮭

- Charles Leary, “The Most Careful Arrangements for a Careful Fiction: A Short History of Asia Pictures,” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 13, no. 4 (2012): 548. ⮭

- Yan Lu, “Limits to Propaganda: Hong Kong’s Leftist Media in the Cold War and Beyond,” in The Cold War in Asia: The Battle for Hearts and Minds, ed. Zheng Yangwen, Hong Liu, and Michael Szonyi (Leiden: Brill, 2020), 95. ⮭

- Kenny K. K. Ng, “Inhibition vs. Exhibition: Political Censorship of Chinese and Foreign Cinemas in Postwar Hong Kong,” Journal of Chinese Cinemas 2, no.1 (2008): 26. ⮭

- There was no clear evidence of Yangtse Incident ever being shown in Hong Kong according to available records. A report from the South China Morning Post mentioned: “Unfortunately this film is not likely to be seen as newer films are already available for preview in the Colony.” See Jean Gordon, “Around the Cinemas: Most Popular Films & Stars of Last Year,” South China Morning Post, April 16, 1958, 4. A report a year later stated that the film was not yet released. Jean Gordon, “Around the Cinemas: Cooper and Heston Dive in Sunken Hold,” South China Morning Post, August 20, 1959, 4. ⮭

- Since the late nineteenth century, the Royal Navy had protected British interests and international riverine commerce in China. For an account of the Amethyst incident, see Edwyn Gray, “The Amethyst Affair: Siege on the Yangtze,” Military History 16, no. 1 (April 1999): 58–64. ⮭

- Myro, “Film Reviews: Yangtse Incident (British),” Variety, April 10, 1957, http://archive.org/details/sim_variety_1957-04-10_206_6. ⮭

- Edouard Laurot, “Cannes Film Festival,” Film Culture, October 1957, 8–9; H.H.T., “Battle Hell: Richard Todd Stars in British Import,” New York Times, August 22, 1957. ⮭

- Derek Hill, “Down-At-Heel Dignity–At Your Cinema,” Amateur Cine World, June 1957, 160–62. ⮭

- John Ramsden, “Refocusing ‘The People’s War’: British War Films of the 1950s,” Journal of Contemporary History 33, no. 1 (January 1998): 35–63. ⮭

- Ramsden, “Refocusing ‘The People’s War,’ ” 59. ⮭

- Shaw, British Cinema and the Cold War, 3. ⮭

- These colonial war films were The Planter’s Wife (1952), regarding the Communist insurgency in Malaya (1948–1960); Simba (1955), regarding the Mau Mau uprising in Kenya (1952–1960); Windom’s Way (1957), set in Malaya; and North West Frontier (1959), set in India. See Harper and Porter, British Cinema in the 1950s, 44–46. ⮭

- Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day (1989), a novel about a fading English aristocracy and the regrets of lost love, takes as its starting point the historical setting of July 1956, which coincides with the beginning of the Suez crisis. ⮭

- In 1956, Egypt’s President Gamal intended to nationalize the management of the Suez Canal. Both shareholders of the canal company, Britain and France were irritated by Egypt’s decision. The two European powers launched an invasion of Egypt. The US president Dwight D. Eisenhower disapproved of the offensive and demanded a military withdrawal as the attack was a reproduction of the old Western colonization. See G. C. Peden, “Suez and Britain’s Decline as a World Power,” Historical Journal 55, no. 4 (2012): 1073–96. ⮭

- The Bridge on the River Kwai illustrates the lunacy of war and the moral dilemmas of the British and American POWs who are coerced to build a railway bridge across the river Kwai for their Japanese captors in occupied Burma. Dunkirk is the cinematic reconstruction of the events that took place between May 26 and June 4, 1940, when approximately 336,000 British, French, and Belgian troops were evacuated from the beaches of Dunkirk in northern France by the combined efforts of naval and civilian crews. Dunkirk is considered the point at which World War II began. ⮭

- Harper and Porter, British Cinema in the 1950s, 136. ⮭

- Penny Summerfield, “Dunkirk and the Popular Memory of Britain at War, 1940–58,” Journal of Contemporary History 45, no. 4 (October 2010): 788–811. ⮭

- See Russell E. Shain, “Hollywood’s Cold War,” Journal of Popular Film 3, no. 4 (1974): 334–50; Jeffrey Richards, China and the Chinese in Popular Film: From Fu Manchu to Charlie Chan (London: I. B. Tauris, 2017), 177–95. ⮭

- Stephanie DeBoer, Coproducing Asia: Locating Japanese-Chinese Regional Film and Media (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014). ⮭

- Erica Ka-yan Poon, “Southeast Asian Film Festival: The Site of the Cold War Cultural Struggle,” Journal of Chinese Cinemas 13, no.1 (2019): 76–92. ⮭

- Quoted from Geoffrey Macnab, J. Arthur Rank and the British Film Industry (London: Routledge, 1993), 225 ⮭

- Stephen Watts, “Rank Theatre Chain, Production List Reduced,” New York Times, October 26, 1958. ⮭

- Harper and Porter, British Cinema in the 1950s, 52. ⮭

- A. H. Weiler, “Endless Trip,” New York Times, September 28, 1958. ⮭

- Harper and Porter, British Cinema in the 1950s, 208. ⮭

- Wendy Gan, “Tropical Hong Kong: Narratives of Absence and Presence in Hollywood and Hong Kong Films of the 1950s and 1960s,” Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 29 (2008): 8–23. ⮭

- Gina Marchetti, Romance and the “Yellow Peril”: Race, Sex, and Discursive Strategies in Hollywood Fiction (Berkeley: University California Press, 1993), 110. ⮭

- Elleke Boehmer, Colonial and Postcolonial Literature: Migrant Metaphors (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), 44. ⮭

- Howard Thompson, “Ferry to Hong Kong Stars Orson Welles,” New York Times, April 27, 1961, 27. ⮭

- Reuters, “It Rivalled Even Mike Todd’s Party! Ferry to Hongkong Given Exotic Send-off in London,” China Mail, July 3, 1959. ⮭

- Reuters, “Film Premiere,” Daily Telegraph and Morning Post, July 3, 1959. ⮭

- “Premiere of Ferry to Hongkong: Chinese Setting to U.K. Party,” South China Morning Post, July 4, 1959, 9. ⮭

- Paul Tanfield, “Is There at the Night of Thousand Lanterns: This Was Mike Todd Stuff! Sampans Make a Splash on the Thames,” Daily Mail, July 3, 1959. ⮭

- James Fazakerley, “ ‘Ferry’ Wakes up London with a Bang and Makes £20,000 for Charity,” South China Morning Post, July 9, 1959, 9; Gilbert, All My Flashbacks, 195–96. ⮭

- Lewin, “Third Man in Hong Kong Part 2.” ⮭

- Lewin, “Third Man in Hong Kong Part 3: Rare Survival: A Genuine Flamboyant Star!” China Mail, March 4, 1959. ⮭

- By comparison, the American Welles showcased an Orientalism that was more self-conscious and oriented toward the grassroots. He drank “spell water” to wish good fortune for the crew according to Chinese superstition. He knew that he would not find chop suey in Hong Kong as the cuisine was created by diasporic Chinese railway workers in North America for American consumption. See Lewin, “Third Man in Hong Kong Part 4: The Fluid Face of Orson Welles,” China Mail, March 5, 1959. ⮭

- Foreign travelers and pioneers to Hong Kong had recorded city life with the new invention of the movie camera since the last nineteenth century. The oldest reel of travelogue documentaries preserved is the Edison Shorts, made in 1898 by the Edison Company. See “Transcending Space and Time: Early Cinematic Experience of Hong Kong (Early Motion Pictures of Hong Kong),” Hong Kong Film Archive, March 21–June 22, 2014, https://www.hkmemory.hk/MHK/collections/ECExperience/about/index.html. ⮭

- “Departure of Orson Welles: Hope to Come Back to Shoot Own Picture,” South China Morning Post, February 28, 1959, 12; David Lewin, “Third Man in Hong Kong Part 2: Behind the Ebullience: Welles Confesses a Lonely Bitterness,” China Mail, March 3, 1959. ⮭

- Chi-Kwan Mark, “Hong Kong as an International Tourism Space: The Politics of American Tourism in the 1960s,” in Hong Kong in the Cold War, 163. ⮭

- John Carroll, “ ‘The Metropolis of the Far East’: Tourism and Recovery in Postwar Hong Kong,” Transnational Hong Kong History Seminar Series, NTU History and Hong Kong Research Hub, Nanyang Technological University of Singapore, February 10, 2022. ⮭

- Chi-Kwan Mark, “Vietnam War Tourists: US Naval Visits to Hong Kong and British-American-Chinese Relations, 1965–1968,” Cold War History 10, no. 1 (February 2010): 1–28. ⮭

- Thomas M. Pryor, “British Film Aide Sees Asia Market,” New York Times, November 1, 1952, 17. ⮭

- Mark, “Hong Kong as an International Tourism Space,” 166. ⮭

- Marchetti, Romance and the “Yellow Peril,” 109–24. ⮭

- Christina Klein, Cold War Orientalism: Asia in the Middlebrow Imagination, 1945–1961 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003). ⮭

- Klein, Cold War Orientalism, 146. ⮭

- For a critique of imperialism in Heart of Darkness, see Edward Said, Culture and Imperialism (New York: Vintage Books, 2012), 19–30. ⮭

- Roy Chiao 喬宏, “GangAolundu yanchu suoji”「港澳輪渡」演出瑣記 [Notes on performing in Ferry to Hong Kong], International Screen [國際電影], February 1959, 26–28, http://internationalscreen.net/yingshi-detail.asp?id=2391. ⮭

- Marchetti, Romance and the “Yellow Peril,” 2. ⮭

- Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End (dir. Gore Verbinski, 2007) featured Hong Kong star Chow Yun-fat in the role of a Chinese pirate captain who is bald and scar-faced and who wears a long beard and long nails. Chow’s screen time was slashed in half by mainland Chinese censors as defacing the Chinese. See “Disney’s ‘Pirates 3’ Slashed in China,” China Daily, June 15, 2007, https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2007-06/15/content_895296.htm ⮭

- Danny 但尼, “Yingping: GangAolundu” 影評: 「港澳輪渡」 [Film review: Ferry to Hong Kong], Chinese Student Weekly [中國學生周報], no. 390, January 8, 1960, https://hklit.lib.cuhk.edu.hk/search/?query=%22%E6%B8%AF%E6%BE%B3%E8% BC%AA%E6%B8%A1%22&publish_year_=%5B1920%2C2022%5D. ⮭

- Lin Si 林思, “Yiwushichu: Ping GangAolundu” 一無是處: 評港澳輪渡 [Completely wrong: Review of Ferry to Hong Kong], Ta Kung Pao [大公報], January 4, 1960. ⮭

- C. M. Faure, “To the Editor: Ferry to Hongkong,” South China Morning Post, January 4, 1960, 11. ⮭

- Paul B. Rich, Cinema and Unconventional Warfare in the Twentieth Century Insurgency, Terrorism and Special Operations (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018), 31–35. ⮭

- Lin, “Yiwushichu: Ping GangAolundu.” ⮭

- Lewin, “Third Man in Hong Kong Part 1.” ⮭

- “Gongfei gejie yaoqi daoluan GangAolundu paishe gongzuo” 共匪隔界搖旗搗亂 港澳輪渡拍攝工作 [Commies wave flags and mess with Ferry to Hong Kong filming over the border], Central Daily News [中央日報], January 8, 1959; Hung 虹, “ ‘GangAolundu’ de daoyan Jierbo touzi zhipian”「港澳輪渡」的導演 基爾勃投資製片 [Director of Ferry to Hong Kong: Gilbert invests in own production], United Daily News [聯合報], February 24, 1961. ⮭

- Poshek Fu, “Entertainment and Propaganda: Hong Kong Cinema and Asia’s Cold War,” in The Cold War and Asian Cinemas, eds. Poshek Fu and Man-Fung Yip (New York: Routledge, 2019), 254–57. ⮭

- Hao 豪, “Aoxunweiersi yu Kouyouningsi hezuo GangAolundu” 奧遜威爾斯與寇尤寧斯 合作「港澳輪渡」[Orson Welles and Curt Jurgens collaborate in Ferry to Hong Kong], Central Daily News [中央日報], January 9, 1961; “ ‘GangAolundu’ paishe wancheng Kouyouningsi xie furen budu miyue Aoxunweiersi zuo sanlunche youjie”「港澳輪渡」拍攝完成 寇尤甯斯偕夫人補渡蜜月 奧遜威爾斯坐三輪車遊街 [Ferry to Hong Kong filming completed: Curt Jurgens’ couple makes up honeymoon; Orson Welles sightsees on trishaw], United Daily News [聯合報], February 25, 1959; Hung, “ ‘Gangaolundu’ de daoyan Jierbo touzi zhipian.” ⮭

- Steve Yui-Sang Tsang, “Unwitting Partners: Relations between Taiwan and Britain, 1950–1958,” East Asian History, no. 7 (June 1994): 105–6. ⮭

- “A Statement of the General Principles as adopted on 20 November 1965 by the Film Censorship Board of Review,” Hong Kong record series, Hong Kong Public Records Office, HKRS 934–5–34, 1965. ⮭

- Poshek Fu, “Modernity, Diasporic Capital, and 1950’s Hong Kong Mandarin Cinema,” Jump Cut: A Review of Contemporary Cinema, no. 49 (Spring 2007), https://www.ejump cut.org/archive/jc49.2007/Poshek/. ⮭

- For Grace Chang’s appearance on an American television show that conformed to the exoticized view of Chinese womanhood, see Stacilee Ford, “ ‘Reel Sisters’ and Other Diplomacy: Cathay Studios and Cold War Cultural Production,” in Hong Kong in the Cold War, 183–88. ⮭

- Adam Nebbs, “Ferry to Hong Kong: The 1959 Film about a Stateless Passenger Who Spent 10 Months Aboard the Lee Hong,” South China Morning Post, May 15, 2020, https://www.scmp.com/magazines/post-magazine/travel/article/3084137/ferry-hong-kong-1959-film-about-stateless-passenger. ⮭

- Richard L. Coe, “The Circuit Riders,” Washington Post, October 29, 1961, sec. G. ⮭

- Mel Danner, “The Exhibitor Has His Say about Pictures,” Boxoffice, December 18, 1961, https://lantern.mediahist.org/catalog/boxofficeoctdec180boxo_0616. ⮭

- Harper and Porter, British Cinema in the 1950s, 55. ⮭

- I submit to Hazel Shu Chen’s view and further explain that the role of Welles as a stubborn British captain, administrator, and buffoon in the film must have disappointed Hollywood’s audience then and now, for whom Welles on-screen had already embodied the identity of Americans who should be saving the world from Communism and colonialism. ⮭

- Stuart Ward, “Introduction,” in British Culture and the End of Empire, 15. For a discussion of British imperial heroes depicted in the post-imperial films, see Jeffrey Richards, “Imperial Heroes for a Post-imperial Age: Films and the End of Empire,” in British Culture and the End of Empire, 128–44. ⮭

- Kent, Ferry to Hongkong, 267. ⮭

- Jonathan Rayner, The Naval War Film: Genre, History and National Cinema (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2007), 215. ⮭

- The remake of Dunkirk (2017) by British American director Christopher Nolan indicates that nostalgic war films have continued to thrive at the British box office. ⮭

- Glen Peterson, “To Be or Not to Be a Refugee: The International Politic of the Hong Kong Refugee Crisis, 1949–55,” Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 36, no. 2 (2008): 171–95. ⮭

- John G Norris, “Hong Kong Low on Reds’ ‘List,’ ” Washington Post and Times Herald, December 5, 1958. ⮭

- James T. H. Tang, “From Empire Defence to Imperial Retreat: Britain’s Postwar China Policy and the Decolonization of Hong Kong,” Modern Asian Studies 28, no. 2 (1994): 337. ⮭

- “History does not repeat itself, but it rhymes”—the humorous aphorism is usually attributed to Mark Twain, but this ascription remains dubious. ⮭

- Laura Westbrook and Danny Mok, “Britain Plans Extension of BN(O) Visa Scheme to Allow Hongkongers Aged 18 to 24 to Apply Independently of Parents,” South China Morning Post, February 24, 2022, https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/society/article/3168295/emigration-wave-continues-about-100000-hongkongers-apply-bno. ⮭

Author Biography

Kenny K. K. Ng is associate professor at the Academy of Film at Hong Kong Baptist University. His published books include The Lost Geopoetic Horizon of Li Jieren: The Crisis of Writing Chengdu in Revolutionary China (Brill, 2015); Indiescape Hong Kong: Interviews and Essays, coauthored (Typesetter Publishing, 2018) [Chinese]; and Yesterday, Today, Tomorrow: Hong Kong Cinema with Sino-links in Politics, Art, and Tradition (Chunghwa Book Co., 2021) [Chinese]. He has published widely in the fields of comparative literature, Chinese literary and cultural studies, cinema and visual culture in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and China. His ongoing book projects concern censorship and visual cultural politics in Cold War Hong Kong, China, and Asia, Cantophone cinema history, and left-wing cosmopolitanism.