On October 6, 1988, on the east slope of Jinan Mountain in Zhongshan District, Taipei City, a group of young college students are out on a photography club activity. Suddenly, a female corpse appears in the shaky lens of their camera—it is in such shock and suspense that the story of Light the Night (2021) kicks off. As the plot unfolds, the audience is drawn into a web of mystery and intrigue as they discover that the murder is linked to a Japanese-style nightclub called Hikari, which means “light,” where one of the hostesses is the likely victim.

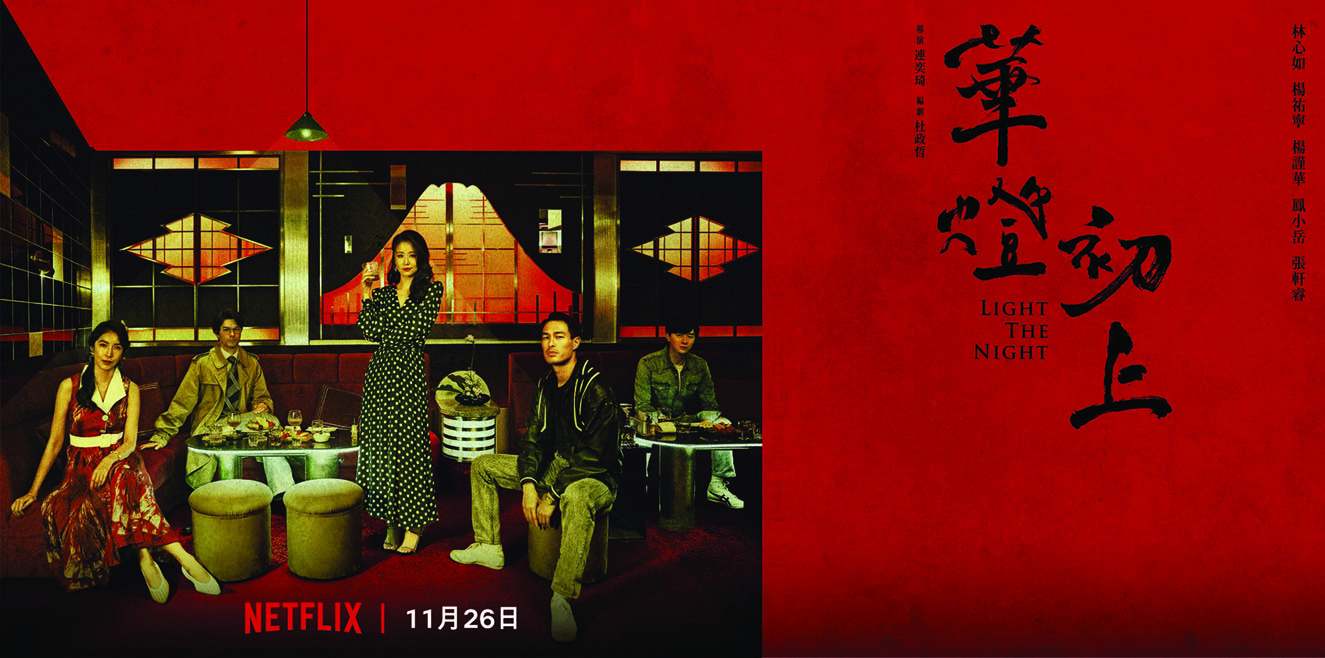

Produced by Ruby Lin, directed by Lien Yi-chi, and written Ryan Tu, Light the Night is a Netflix original series comprised of three seasons, each with eight episodes. The first two seasons were released in November and December 2021, respectively, with the third season following in March 2022. The drama boasts an impressive cast, featuring stars such as Ruby Lin, Cheryl Yang, Tony Yang, Rhydian Vaughan, and Derek Chang. It delves into the complex relationships among the hostesses working at the Hikari nightclub, exploring themes of jealousy, heartbreak, friendship, love, and betrayal.

Source: Netflix Newsroom https://about.netflix.com/en/news/in-star-studded-light-the-night-a-unique-taipei-subculture-comes-alive

The central plot of the drama revolves around the murder-mystery surrounding the unidentified corpse. The first season depicts the story building up to the murder, with the victim’s identity revealed in the concluding episode. The second season investigates the motive behind the crime, culminating in another murder and further heightening the suspense. The identity of the murderer remains a mystery until the end of the third season. The show’s immense popularity can be attributed to its use of diverse genre elements such as romance, crime, and suspense, as well as its nonlinear narrational form, as seen in its numerous flashbacks and interludes. Based on Flixpatrol’s data,1 the drama secured the top spot in Netflix Taiwan’s most-watched list on its second day of release (November 28, 2021). It maintained its position in the top ten for a total of 103 days. Additionally, the show also made it to the top ten in Netflix Hong Kong, Singapore, and Malaysia.

The story is set in the “Tiao Tong” (jo dori) area in Taiwan in the 1980s. “Tiao Tong” refers to “alley” in Taiwanese usage of Japanese, and the Tiao Tong area is comprised of nine parallel alleys near Taipei Main Station. Each alley is named from Tiao Tong One (ichi jo dori) to Tiao Tong Nine (kyu jo dori), and they are connected by the main road, Lin Sen North Road. In Taiwanese vernacular memory,2 Lin Sen North Road was a synonym for red-light districts and prostitution in the 1980s. During the Japanese economic boom in 1980, many Japanese investors came to Taiwan, and their after-work drinking culture fuelled the growth of Japanese-style nightclubs. Additionally, on July 15, 1987, Taiwan lifted martial law, ushering in economic liberalization and consumerism, which led to an increase in locals’ willingness to spend time in entertainment venues. Hikari nightclub was born out of this era. The hostesses at Hikari sell emotional companionship and romantic fantasies while striving to maintain their dignity. However, their relationships with the guests and with fellow hostesses inevitably evolve into complicated issues. Such a setting allows the drama to portray the stories of the marginalized group of hostesses, explore the existence and authenticity of “love,” and engage a sense of nostalgic sentimentality.

Set against the backdrop of Tiao Tong, the drama’s most prominent aspect lies in its portrayal of the female characters within the red-light district. The focus is on two female characters, Lo Yu-nung Rose (Ruby Lin) and Su Ching-yi Sue (Cheryl Yang), and their emotional entanglements over the years, presented through a nonlinear storytelling approach. As the story unfolds in reverse order, we witness the depth of their friendship as they navigate their past. Having been neighbours since high school, they have relied on each other through thick and thin. Su Ching-yi suffers from the trauma of being raped by her stepfather with her mother’s acquiescence, followed by an unwanted pregnancy, which ultimately leads her to leave her family behind and turn to Lo Yu-nung for refuge. During the process, Lo comes to Su’s aid with unwavering support. Meanwhile, Lo’s life is almost equally tumultuous, as she abandons her college studies to marry her boyfriend Wu Shao-chiang, only to end up in prison for several years due to Wu’s illegal activities in business. Ultimately, the two female characters both find solace and a new beginning at Hikari, where they become business partners under the pseudonyms of Rose and Sue. However, conflict takes place as they fall in love with the same man, screenplay writer Jiang Han. For all those years, Rose and Sue remain steadfast by each other’s side, making their eventual separation all the more heartbreaking.

While the intricate entanglement between the two friends serves as the primary plotline of the series, the drama ultimately presents a collective portrayal of a multitude of unique female characters, including Hana, A Chi, Aiko, and Yuri serving as other hostesses at Hikari. Through the narration of their stories, the drama generates a sense of uncertainty regarding who the victim, perpetrator, and instigator truly are. Furthermore, this group portrayal also provides a vital opportunity to explore various dimensions of female trauma, allowing for a richer and more nuanced representation of women. As such, no single character can be deemed the protagonist, as they are all integral in crafting a complex and multilayered story.

Hana, one of the most tragic female characters in the series, is once coerced into prostitution by her ex-boyfriend and goes to jail for manslaughter. The depiction of Hana’s story explores the use of film language to convey the brutality of sexual assault. Through the use of techniques such as montage, splicing the scene where Hana is raped in the rain with the scene when she takes a shower after returning home, as well as employing jump cuts between the scene of her manslaughter and the one where she repeats the mistake, the drama underscores the enduring impact of trauma by portraying the narrative itself as a scar of trauma. The character A Chi, who is initially considered the least popular figure at Hikari due to her gambling debts and frequent arguments with other hostesses, gradually evolves as we witness her dysfunctional family and her indifferent parents. By focusing on A Chi’s story, the drama highlights the relationship between a woman and the space she occupies, as A Chi lacks “a room of her own” and is constantly confined to narrow spaces such as her bed or the backyard, signifying an oppressive confinement of women. Yuri, the cool and distant hostess, shields herself behind a defensive facade. The drama exposes her vulnerable side as she seeks solace in the company of a host named Henry but unfortunately becomes involved with a drug-dealing group because of him. The drama aims to create multifaceted and diverse characters with the women of Hikari. Loneliness, the fragility of human relationships, and the deep yearning for love are recurrent motifs throughout their lives.

Mutual salvation is undoubtedly one of the profound meanings of the word Hikari. The story, overall, tells how female characters bond with, support, and help one another. Since the moment Rose and Hana become friends in jail, Rose has tried her best to protect Hana and help her rebuild herself after a traumatic experience. As the story progresses, a shift also happens in A Chi, who gradually starts to take responsibility for other hostesses as well as the club. Near the end of the third season, A Chi finds out she is pregnant and decides to leave. Rose goes to her place, and in their conversation, Rose points out, “The place where you do whatever you want, where you are truly yourself, is where you call home.” When A Chi, the most “annoying” hostess, announces her pregnancy, the characters each uniquely show that they care. Such female bonding is perhaps the central meaning of “light.”

Despite the deep exploration of female bonding, the audience may question how such profound friendships, especially between Rose and Sue, could crumble due to a man’s involvement. The drama attempts to address this by offering an alternative explanation for female jealousy, which is also the reason behind the transition in Sue’s character. Though she initially appears to be the perfect hostess, Sue harbors a desire for revenge against Rose before her departure from Taiwan for Japan, a revelation that shocks and confounds many viewers. In her diary, she describes the pain she has been feeling due to Rose’s patronizing behavior, a sentiment that other female characters like A Chi and Hana share. Their repeated question “How could you patronize me?” highlights the underlying resentment in their relationships.

Jealousy, a trait often conflated with womenhood, has been traditionally depicted in Chinese culture as a rivalry between wives and concubines. In the first season of Light the Night, Sue’s jealousy toward Rose initially seems to stem from a competition over a man. However, the series delves deeper into this theme, exploring women’s pursuit of self-establishment and their quest for agency. Sue’s suffering arises from being constantly “saved” but never taking control of her own destiny, taking responsibility for her child, or having a say in her love for Jiang Han. It is also noteworthy that the female characters at Hikari are identified mainly by their Japanese pseudonyms, which obscures their true identities and indicates a lack of control of their lives. Trapped by their names and by their profession, where emotions are feigned, their jealousy and resentment toward Rose reflect a broader sense of helplessness and lack of agency that extends beyond the traditional definition of “female jealousy.” It is their way of striving for a voice and asserting their individuality.

In addition to the complex relationships among the female characters, Light the Night incorporates various genre elements such as drug dealing, violence, corruption, crime, and gangsters, which add to its appeal and commercial success. However, the inclusion of these elements also presents challenges, such as the occasional repetition of information from the first season, which can slow the pace of the later episodes. Nonetheless, the drama’s release over a span of three months compensates for this flaw. Furthermore, the genre mixture allows for the inclusion of diverse and dynamic characters, such as the male characters Pan Wen-cheng (Yo Yang), a policeman, and He Yu-en (Derek Chang), a college student who later becomes an intern journalist. These characters complicate the plot and draw attention to issues like corruption and journalistic ethics. Another example of the show’s diverse characters is the drag queen played by Wu Kang-ren, who challenges societal norms with seemingly hilarious questions like, “Can’t a man be a hostess?” Although only comical at first sight, the later development of this character indeed brings a bold and refreshing perspective to the drama.

The richness of the drama is also evident in the details. The drama incorporates allusions to popular songs that prompt us to consider the political climate of the story. The 1980s were a decade marked by a series of significant events in Taiwan. Martial law was imposed from May 20, 1949, to July 14, 1987, creating an atmosphere of tension and terror. Popular songs were banned due to their potential political implications and news was strictly censored. The drama seeks to incorporate cultural elements by featuring the recurring Taiwanese song “May You Have Happiness,” initially released in 1972 and later celebrated for its empathy toward ordinary people like Hana. The drama also challenges cultural hierarchies. Hana’s lack of Japanese language skills and her rural background initially prevent her from joining Hikari. However, everyone eventually appreciates her singing, reflecting an attempt to value Taiwanese culture. Also, He Yu-en’s character, examined against the backdrop of the lifting of martial law, should not be seen as a naive college boy falling in love with a hostess but rather as a young man who later enters the news industry and seeks the truth. The fact that Rose has the opportunity to address the media and explain the circumstances surrounding the murder further illustrates the drama’s attention on the news industry.

The endeavour of Light the Night to tackle comprehensive and sophisticated themes should not be viewed as isolated. Instead, it warrants examination within a broader context, offering insights into the historical development of Taiwanese dramas. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, Taiwanese dramas were characterized by the “idol soap opera” style, which featured simplified and unrealistic romantic love stories between young men and women, following the tradition of Qiong Yao dramas from the 1950s and 1960s. Famous dramas include Meteor Garden (2001), It Started with a Kiss (2005), The Prince Who Turns into a Frog (2005), and Fated to Love You (2008), which were popular in Taiwan and have been imported into mainland China. However, with In Time with You (2011) as the division point, Taiwanese dramas experienced a decline around the year 2011.

Facing such a decline, there have been many efforts to explore a way out. A significant event was the emergence of a new form of TV series called Qseries, 植剧场, in 2016. The character “植” literally means “plant,” which, according to chief inspector Wang Shaudi, signifies the effort to root TV drama in Taiwan and cultivate new talents for the TV industry.3 The series comprises eight parts, with a total of fifty-two episodes, covering four major genres: love and growth, suspense and deductive, supernatural and horror, and adaptation from original works. In the 2017 Taiwan Golden Bell Awards, the Best Drama Award was given to two dramas coming from Qseries: Close Your Eyes Before Its Dark (2016) and A Boy Named Flora A (2017). Such exploration of different genres is paving the way for the future production of genre-mixing commercial dramas.

The transformation of the Taiwanese TV industry was widespread, with numerous individuals switching roles. Ruby Lin, once the leading actress in Qiong Yao-style dramas, has become a producer. Similarly, Alyssa Chia, also a well-known actress in idol soap dramas, produced the critically acclaimed drama series The World Between Us (2019), a Netflix original series that achieved phenomenal success in 2019. In an interview, Lin talks about how, as an actress, there are certain characters such as hostesses that she wants to explore, and emphasizes the necessity for workers in the Taiwanese drama industry to evolve and adjust to new roles and performances in response to the genre’s diverse demands.4

Furthermore, such development not only highlights the increased participation of female figures in the drama-production industry but also demonstrates how overseas over-the-top (OTT) media-service platforms like HBO, FOX, and Netflix have begun to produce Asian TV dramas, sparking a revival of Taiwanese dramas. In a recent interview with “Yu Li,”5 Chih-Han Chen, the producer of Someday or One Day (2019), discussed the three primary approaches to producing Chinese dramas for overseas OTT platforms. The first method involves full investment and high involvement from the OTT platform, with local production companies only responsible for production. The second approach is a joint investment between the OTT platform and the film and television company, with the former buying out the distribution rights of the project. In this scenario, the script has already been completed when communication and cooperation begin. The third approach is a collaboration between TV stations and film and television companies, with the platform deciding whether to cooperate after seeing the finished drama. According to Lin,6 this is the case for Light the Night, so the production team gets to keep all the content from the beginning. The extent to which OTT platforms should be involved in content development and how to achieve a balance between local and global/universal elements remain unresolved issues, as we see that adjustments are constantly made in different methods and cases.

Nevertheless, Light the Night is certainly a successful production of such cooperation. With its unique setting in 1980s Taiwan, the remarkable performances by Taiwanese actors and actresses, and Netflix’s professional marketing strategies, the series has successfully found a balance between entertainment and popularity and seriousness and social responsibility. Netflix commented on Taiwanese drama that “Southeast Asia is a large region with diverse and complex cultures, and Taiwanese dramas provide unique stories.”7 How will OTT platforms depict stories within the Sinitic-language world in the future? How can Taiwan further contribute to the global stage? Light the Night is just the beginning, shedding light on these questions that remain to be explored.

Notes

- “Light the Night Top 10,” Flixpatrol, accessed April 1, 2023, https://flixpatrol.com/title/light-the-night/top10/. ⮭

- Chen Yonghan 陳永翰, “Tiao Tong” “條通,” Di Shiqi Jie Taibei Wenxuejiang Dejiang Zuopinji 第十七屆臺北文學獎得獎作品集 (The collection of winning works of the 17th Taibei Literature Award) (Taibei: Taibei Shizhengfu Wenhuaju, 2015), 110–15. ⮭

- Haofengguang Chuangyi Zhixing好風光創意執行 and Yuandongli wenhua原動力文化, Yichang wenrou Geming: Zhijuchang quanjilu一場溫柔革命:植劇場全記錄. (A gentle revolution: documentation of Qseries) (Taibei: Yuandongli Wenhu Shiye Youxiangongsi, 2018). ⮭

- Fei Yu 飞鱼, “Huadeng Chushang: Sheiren Buzai Huanle Chang, zhuanfang lin xinru《华灯初上》:谁人不在欢乐场|专访林心如” (Light the night: Who is not in the entertaining circle, an exclusive interview with Ruby Lin), Toutiao.com, accessed February 10, 2023, https://www.toutiao.com/article/7083134824801960484/?source=seo_tt_juhe&wid=1678405646200. ⮭

- “Taiju Ruhe zai Liangniannei Wancheng Nixi: Chen Zhihan zhuanfang 台剧如何在两年内完成逆袭?陈芷涵专访” (How did Taiwanese drama revive in two years? An exclusive interview with Chen Zhihan), k.sina.com, accessed February 10, 2023, https://k.sina.com.cn/article_5737990122_15602c7ea01900lkys.html?cre=tianyi&mod=pcpager_focus&loc=18&r=9&rfunc=100&tj=none&tr=9. ⮭

- Fei Yu, “Interview with Ruby Lin.” ⮭

- “Sandairen de qingchun: liushinian taiju xingshuaishi 三代人的青春:六十年台剧兴 衰史” (The youth of three generations: The rise and fall of Taiwanese Drama in sixty years), Everyone Focus, accessed February 10, 2023, https://ppfocus.com/0/he631bcbd.html. ⮭

Shuwen Yang is a PhD student in the Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures at Stanford University. She is interested in science fiction, online literature, and fandom studies.