Introduction

In the second half of 2019, as Hong Kong’s prodemocracy protests gathered force, residents of the city who paid attention to international media were struck by the cognitive dissonance of headlines and images suggesting a city under siege. In my case—and I was hardly alone—relatives and friends outside Hong Kong contacted me with concern. Was I safe? Would I need to leave the city in a rush with no more than a suitcase in hand?

On one of those frenzied days when Hong Kong seemed to be burning, I strolled down Wyndham Street into the central business district on Hong Kong Island, at the junction of Peddar Street and Des Voeux Road, lined with high-end luxury stores and banks. In mid-November, demonstrators emerged twice daily, at noon and after work, to wave flags, obstruct traffic, and build artistic barriers from bricks and bamboo building materials that were quickly removed after each episode. A few hours before I walked down, after the noon break, riot police had stormed up Wyndham Street firing tear gas. Now all was calm.

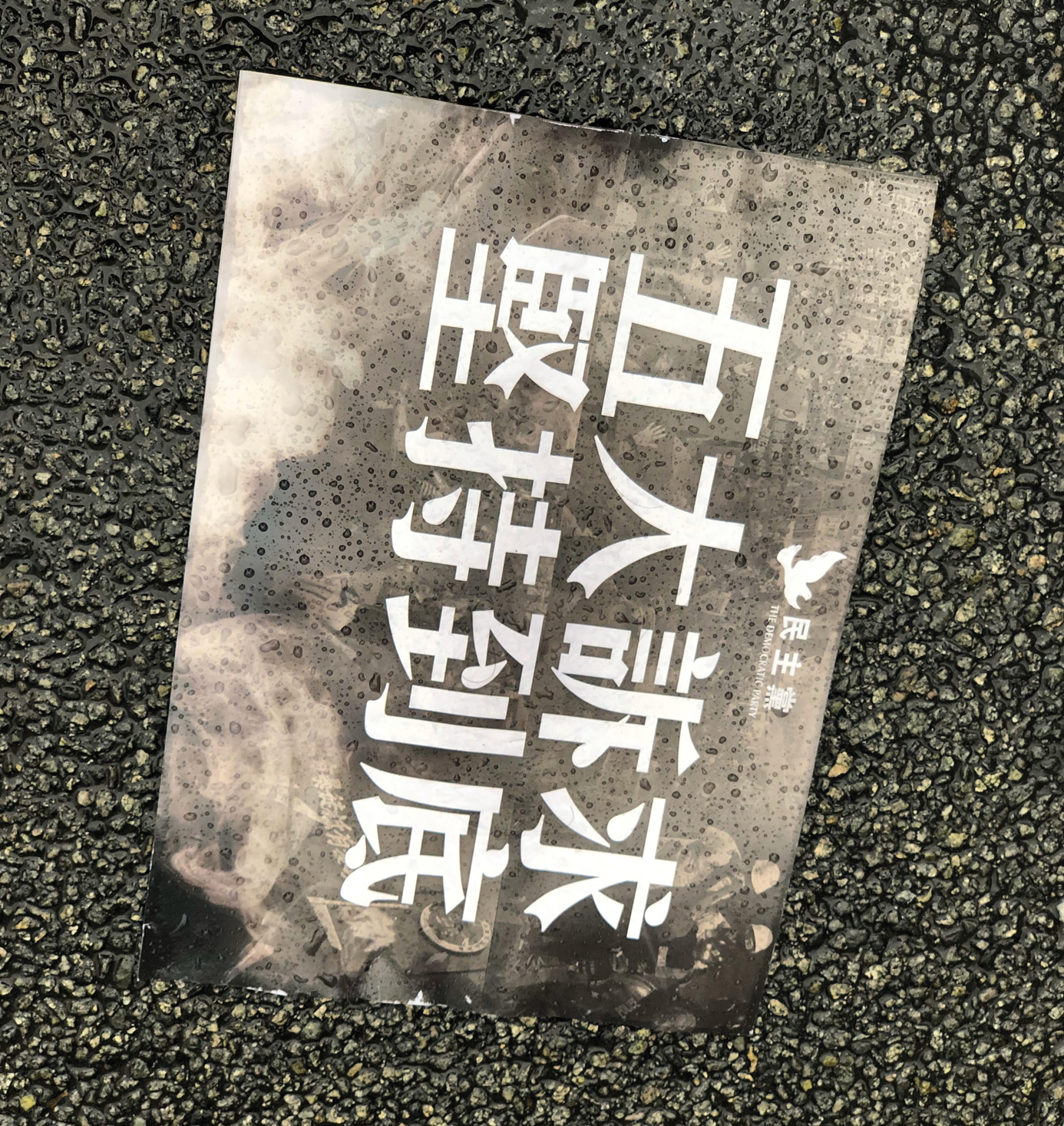

A group of one hundred or so protestors—clad in black, the uniform of the protests, and mostly unmasked—stood chatting in the otherwise empty streets at about 6:30 p.m. Some gathered around traffic lights giving each other boosts to get to the height where they could smash signal lights. Others gathered to push over concrete planters. Earlier, someone had smashed the windows of China Commercial Construction Bank, one of China’s state-owned banks. A black-clad young man walked back and forth with a large black flag, emblazoned in white letters: “Free Hong Kong: Revolution Now.” There were no police in sight. Some of the protestors made distinctly fashionable statements in black, derived in part from video games. Nobody paid attention to a foreign woman passing through until I began taking photos with my mobile phone. Then the protestors made shushing motions with their hands and raised umbrellas to hide their identities. Half an hour later, in advance of a police cordon, the crowd melted away.

There were, of course, vast flows of people in organized marches, as many as a quarter of Hong Kong’s population, in early June 2019, and focused violence, particularly against police and Hong Kong’s Mass Transit Railway system, or MTR, which had tried to block protestors by shutting down parts of its massive network. Masked and helmeted protestors in black T-shirts and jeans hurled petrol bombs and smashed MTR gates, turnstiles, and ticket machines. Protestors barricaded two major university campuses in November 2019, fighting off police in full riot gear with bows and arrows and catapults. Yet the genius of the movement was its ability to launch small-scale actions in many parts of the city simultaneously, from the skyscraper canyons of Central to the decaying shop houses of Kowloon and dense high-rises of the New Territories. Urban residents, including myself, had to go looking for the protests, learning to circumnavigate the more intrusive ones.

The drama that gripped the world for many months was many things, but it was not the full-fledged rebellion that it appeared to be on the evening news and which served the purposes of both China’s central government, who denounced the protestors as terrorists and rioters, or the Trump administration in the United States, hailing them as “freedom fighters.”1 One reason for the disconnect was the masterly use of social media by the protestors, not as disinformation but as a megaphone, GPS-driven organizing tool and platform, with mainstream media accepting their message and delivering it directly to readers and viewers around the world.

The bureaucratic local government was caught flatfooted both by the scale and the use of social media by organizers to create constantly forming and dissolving nodes of protest across the city of 7.5 million. Unlike in Mainland China, where the government has long monitored social media and employed armies of so-called 50-centers to foil any sign of dissent with counter-messaging, in Hong Kong, not only was social-media content nearly free from regulatory or political interference, it was wielded by some of the most tech-savvy kids on the planet. Protest movements elsewhere have quickly learned the methods and adopted them, from Paris to Bangkok. In Hong Kong, however, the initial success of the movement contributed to its own destruction, as protestors failed to seek compromise even after achieving at least one of their goals. Instead, some of the well-known features of social media worked against de-escalation, particularly its tendency to create filter bubbles against contrary fact and create self-reinforcing loops of information.

Social media did not create Hong Kong’s 2019 protests but created enormous energy that amplified both their organizing capabilities and their messages. The quantum ecology of social-media instruments and platforms was readily understood and put to use by those outside the establishment. It has become one more instance of the immense power of a new way of building human community—in this case, around the identity politics of resisting the “mainlandization” of Hong Kong. Nearly everybody in Hong Kong owns a mobile phone, or several. But it was principally the young, who grew up after 2007 in the age of the iPhone and its shopping mall of software applications, for whom locational and messaging apps were an integral part of social life and who were able to integrate the technology organically as they became politicized.

The Weaponization of Social Media

The protests built up quickly from an unlikely beginning, a government bill to allow transfers of fugitives from Hong Kong courts to Mainland China, Macau, and Taiwan, which had been disallowed under existing law. While the local government contended it was designed merely to fill a procedural loophole, many in Hong Kong, including the business elite, saw it as a means to extend application of Mainland law to Hong Kong and potentially drag offenders across the border. The protests disrupted the city’s airport and rail transport and sporadically halted road traffic as protestors used bricks, railings, rubbish bins, and other objects as barriers.

In 2019, more than one hundred groups on the messaging site Telegram, Instagram, and LIHKG, an online forum, crackled with activity, shaping the protests themselves as well as local and global media coverage. The local Hong Kong government was blindsided, but China, long aware of the risks of social media and accustomed to tight monitoring, saw the hyperactive expressions and political organizing through social media as the beginning of a color revolution in the manner of politically traumatized nations in the Middle East and the former Soviet Union.

Unlike the toxic ways in which actors as diverse as Russia, alt-right activists in the United States, and K-pop fans have put social media to use to destroy opponents largely by spreading disinformation, there was a kind of wild innocence to the sprawling mass of social-media content generated by the Hong Kong protests.

Anjana Susarla, an associate professor of information systems at Michigan State University, argues that there are two mechanisms that make social media influential in digital activism: the role given to a few influencers with large networks to influence public opinion, and the tendency to engage on social media with like-minded people, which Professor Susarla calls homophily.2 “Social media’s opinion-making power and preference for like-minded connections also lead to online filter bubbles, echo chambers that amplify information that people are predisposed to agree with and filter out information that contradicts people’s points of view,” she writes.

Both were key elements of the Hong Kong protests, together with a third factor unique to Hong Kong: its admirably efficient public transportation network and its antithesis of absurdly congested streets. Using GPS-enabled messaging apps, the protestors literally flowed like water through the city while police forces and firefighters were consigned to the road system. This made the movement a nightmare to control, despite the MTR’s efforts to shut down parts of the system to block the protests.

Another factor behind the successful deployment of social media by Hong Kong’s digital activists was the sheer density of mobile phone use. The city’s five competing telecommunications operators offer high bandwidth and immaculate coverage. According to Hong Kong’s Office of the Communications Authority, Hong Kong’s mobile subscriber penetration rate as of May 2020 was 273.9 percent and there were 23.1 million mobile subscriptions for its 7.5 million people, implying three subscriptions and three phones for every resident.3 Hong Kong’s mobile phone operators generally provide the latest handsets for free with every service renewal, making it even easier for residents to acquire the latest, most highly featured phones (see figure 1.5).

During the 2019 protests, mobile phones recorded each confrontation from multiple angles. Images went viral over the interlocking networks of the movement. Every encounter featured a thicket of upraised arms pointing camera phones at the action, with simultaneous uploads making it possible for viewers to conduct rudimentary real-time fact checking. The combination of a ubiquitous smartphone ecosystem, efficient MTR, and GPS-enabled social messaging apps made it possible for protestors to move across the Hong Kong landscape “like water,” in a phrase adopted from kung fu icon Bruce Lee that lent itself to the protests later called the water movement, ebbing and flowing ahead of organized police actions and striking at locations across the MTR system virtually at will. The water movement was not the only name given to the protests—yellow helmets were seen as its symbol in the early days—but it was the one that stuck.4

The fact that social-messaging apps were relatively open to all subscribers added another dimension. The protestors assumed that everyone in Hong Kong was as savvy as they were with messaging apps. As long as they gave a few minutes of warning before the next strike, they could recruit protestors to race to the scene as well as warn bystanders to stay away. Instead, traffic snarled up readily as protestors manned overpasses and blocked exits to the main tunnel under Victoria Harbor.

In August 2019, Reuters pieced together their modus operandi of protest social media based on more than one hundred groups on the messaging site Telegram, Instagram, and the LIHKG online forum: “The groups are used to post everything from news on upcoming protests to tips on dousing tear gas canisters fired by the police to the identities of suspected undercover police and the access codes to buildings in Hong Kong where protesters can hide,” the Reuters story noted (see figure 1.2).5

Any observer subscribing to the messaging app Telegram, for instance, could access groups texting event lineups in Chinese and English on a daily and even hourly basis. Twitter feeds and Instagram were also readily accessible to observers outside the protest movement. Police could monitor the channels as well but were prevented by their own protocol and logistics—using the motorways and traveling in groups rather than individually—from effective action.

Social media also helped the protestors develop a specific style, which was replicated by other protest movements in its aftermath. The style mutated out of ubiquitously popular video games, with ninja-like black uniforms paired with helmets, goggles, and umbrellas, first seen on Hong Kong’s streets in mid-June 2019. Dr. Tommy Tse, an assistant professor at Hong Kong University, was quoted saying: “Protestors wanted to use [the color of their clothes] to communicate their sorrow, anger and regret… . It also creates a stronger visual effect when it comes to the aerial photos by the media, symbolizing a sense of unity and determination against the unprecedentedly suppressive political environment.”6

There is no question that Hong Kong’s many young people are addicted to video games, and Hong Kong as a location for video games is popular globally, according to Hugh Davies, a games researcher at RMIT University.7 According to a 2017 survey of upper primary students by the University of Hong Kong, students spent an average of eight hours a week gaming.8 Among the games that are regularly cited by Hong Kong media for their popularity is the 2016 game Mini Metro, which challenges users to understand transport systems and use them competitively. The Hong Kong edition of the game9 is based around Kowloon and rewards players for delivering eleven hundred passengers using no more than eight stations and spookily seems as though it might have been a learning tool for the protests (see figure 1.3).

The point at which social-media narratives overwhelmed conventional reporting is unclear—traditional media valiantly provided saturation coverage—but the geographic fluidity of the movement and the absence of single-point communications made it inevitable. Nobody, not even the local Chinese broadcast and print media or the well-funded English-language South China Morning Post, could put enough reporters on the ground to cover a movement that popped up here, there, and everywhere as protestors shared spur-of-the-moment ideas about where to go next and what to do there. Virtual media live-streamed events.

In between the one hundred or so social media channels, citizen journalists, mobile-wielding protestors, and members of the public also wielding mobile phones, the volume of content was extraordinary, becoming a rich trove of images and information for mainstream media and accessible to anyone using the same apps anywhere. Telegram, for example, had English-language channels, which quickly translated instructions for the protests and served as message boards.

Social media became more than just a platform. Social media was the story itself, with its stark, dramatic, and appealing narrative. Prominent international journalists such as Washington Post columnist David Ignatius dropped in on the events to see Hong Kong’s “freedom fighters” for themselves.10 The line between peaceful protest and violence was blurred; the protestors insistence on key principles of solidarity and leaderlessness prevented advocates of Gandhian civil disobedience advocates from speaking out against the radicals who drew their motto from the dystopian 2012 film The Hunger Games: “If we burn, you burn with us” (see figure 1.4).11

The line between social media as input and social media as proxy for direct reporting of individuals and events one by one may have seemed clear at the outset but became increasingly blurred. The fact checking of traditional journalism was challenged by the massive stream of content.

Consequences

A year later, the city has gone silent, partly as a result of restrictions on public gatherings during the COVID-19 outbreak. A new National Security Law enacted by China’s National People’s Congress has made the acts of posting social-media content, painting graffiti, using the slogans of the protests, and even displaying their art or performing its music into treasonable acts subject to lengthy prison sentences and potentially transfer to the grim administration of Mainland courts. The accounts have since closed, and a Stasi-like government hotline to report suspected violations of the National Security Law got more than ten thousand calls in its first week of operation.12

Despite the hyperventilation of social media and mainstream media combined, during the protests, civil liberties and the rule of law remained in place, even if they were under severe pressure. This was what made the images and headlines of mainstream media so discordant to local observers, activists aside. Images of fires and tear gas translated into impressions of a City on Fire, the title of a well-regarded book by Hong Kong-based lawyer Antony Dapiran.13 It helped that Hong Kong was remote and exotic and that to viewers outside Asia, the geography might be indistinct.

Major international media accepted the story line of the protest movement and used the movement’s social media as a source, despite evidence of many kinds of malfeasance to which it is prey, ranging from doxxing to leaking personal detail on social media14 to false identities to conspiracy theories. While the protests lasted, roughly from June to November, there was virtually no oxygen for reporting the views of government, business, or the roughly 40 percent of the population that opposed the protests. To be sure, behind closed doors, many within the city’s political and business elite were furiously angry with the government of Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor, the chief executive of Hong Kong, for allowing the protests to escalate and for failing to withdraw the extradition bill earlier. But there were also many who were angry with the protestors for their intransigence and for tearing the city apart. The chief victim was the loss of any sort of middle ground or space for constructive dialogue.

Among the untold—or at least under-told stories—was the protest movement’s exclusion of outsiders, which ensured that Hong Kong’s non–Cantonese-speaking population served mainly as bystanders to the movement, underlining the identity politics that were an essential part of the protest narrative. The movement welcomed international observers but not nonlocal participants, defining local as Chinese who were born and grew up in Hong Kong with local parents. Social media reinforced the barriers, not only because it was largely in Cantonese, which has many unique Chinese characters and grammatical variation from the standard spoken Chinese used in Mainland China, but also because the protestors began using alphabetic forms of Cantonese as a means of encrypting their communications.15 More than one million Mainlanders resident in Hong Kong were not represented at all, and the protestors pointedly demonized the use of standard spoken Chinese, Mandarin, or Putonghua versus the local language, Cantonese.16

It rapidly became clear that taking sides for or against the protestors was risky in the extreme. Few of Hong Kong’s seven hundred thousand international expats publicly embraced or denounced the protest movement, worried about jobs and education for their children when most schools cancelled classes due to the protests. Companies like Cathay Pacific, Hong Kong’s flagship airline, fired employees just for displaying sympathy with the protests on their Facebook accounts.17 Expatriate entry visa applications plummeted.18

There was, in fact, no middle ground from which to build dialogue. Some of those who self-identified as centrists tried to influence the course of events the traditional way of Hong Kong elites, by networking at the top. Their efforts were futile. Christine Loh, a respected former legislator and government official as well as the founder of the think tank Civic Exchange, concerned with urban sustainability, argued for a change in mindset that would allow Hongkongers to put aside their British-colonial past and work toward a shared identity with Mainland China, particularly in southern China and the newly proclaimed “Greater Bay Area,” including Hong Kong and its neighboring metropolitan areas in the Mainland.19 This point of view, which might have gained traction with Beijing, was unappealing to middle-class Hongkongers accustomed to the civil liberties enshrined in the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration on Hong Kong and the 1990 Basic Law, or mini-constitution, enacted at the time of the handover in 1997 (see figure 1.5).

City on Fire?

As theater, the protests were successful, but as political action, they failed. The protest movement gained momentum and broad public support based on fears that the Hong Kong government was eroding civil liberties guaranteed at the time of Hong Kong’s handover in 1997, under the formula of “one country, two systems.” The leaderless structure of the protests, however, combined with its apparent support for violence, gave key cards to the Hong Kong authorities and, behind them, Beijing.

The protestors’ use of simple and vivid slogans to represent their demands helped in delivering their message if not too closely examined. The key slogan—“five demands, not one less”—continued to be repeated even after one of the core demands, removal of the extradition bill, had been met. The five demands,20 including electoral democracy, were represented by the upheld hands and outspread five fingers of the protestors, with the other hand usually holding a mobile phone.21 No serious set of proposals ever surfaced to negotiate the remaining four demands, due to absence of a leadership structure that might have designed a strategy.

Rowena He, a political scientist, was teaching Chinese politics in the fall semester of 2019 when the Chinese University of Hong Kong became a battleground.22 Writing from a firsthand perspective, He argues that the intentional lack of leadership and open discussion, together with the imposition of a draconian unity rule, undermined the movement and led to its eventual failure.

To defend the absence of leadership, the protestors used the expression, “no main stage,” referring back to prodemocracy protests in 2014 inspired partly by Occupy Wall Street and other centers of power. Factionalism and the later arrest of movement leaders were seen as fatal flaws of the earlier movement. To support their insistence on solidarity, the protestors used an archaic Chinese expression: “no mat cutting,”23 referring to a late Han fable in which two students—one idealistic, the other pragmatic—sitting on a reed mat cut it to demonstrate their different values as well as the end of their friendship.24

He writes: “The animus toward [the] ‘main stage’ and the rejection of ‘mat-cutting’ were legacies of 2014’s failures and its aftermath. In reacting to the perceived flaws of hierarchical power and centralized decision-making, Water Movement protesters swung too far in the opposite direction. When leaders were needed to make strategic and tactical decisions, the animus against leadership proved disabling.”25 While the use of social media was not responsible for creating the norms of the movement, it reinforced them through online filter bubbles, possibly preventing the protestors—and the mainstream media following them—from being more critical of their lack of strategy.

Outside Hong Kong, however, the water movement was a resounding success, arousing sympathy around the world and leading to punitive actions against the Hong Kong government, seen as a bad actor in the protests. Hong Kong became a live issue in the United States Congress and the White House. On July 14, 2020, US president Donald Trump signed an executive order ending the special-trade status granted to Hong Kong under the United States–Hong Kong Policy Act of 1992, which gave Hong Kong-passport holders preferential treatment over Mainland China passport holders, allowed Hong Kong to import US military and defense equipment, and exempted it from tariffs imposed on China.26 On the same day, he signed a bill into law requiring sanctions against individuals and banks contributing to the erosion of Hong Kong’s autonomy.27 By August 11, 2020, the United States had issued sanctions on eleven Hong Kong figures, under the provisions of the Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act of 2016.28

As early as June 2020, hardliners in the United States had suggested using provisions of the Global Magnitsky Act against “China’s rules,” including Hong Kong officials, “to impose enduring pain on senior party officials and on the corrupt police and judges who implement policy at the street level in Hong Kong.”29 While Lam, the chief executive of Hong Kong, publicly derided the sanctions as “meaningless,”30 their passage underlined that the United States considered Hong Kong to have surrendered its autonomy under the “one country, two systems” formula, originally proposed by China’s paramount leader Deng Xiaoping in the early 1980s.

Aftermath

Other than the withdrawal of the extradition bill, the protestors gained none of their objectives, and the relatively narrow extradition bill had been replaced by the sweeping National Security Law, including claims of extraterritoriality, which, by August 2020, placed a number of Hong Kong and American activists on an international wanted list published by the Hong Kong government. One could argue, as some did, that the protest movement would live on because of its principles and idealism and because the problems that fed the movement remained unresolved. But the movement itself, like the social media that had been its voice, went into deep freeze, with social distancing rules under the COVID-19 pandemic preventing most public gatherings beginning in January 2020. Time will tell, of course, whether the goals of the movement are met if and when China becomes more democratic, but that time was not in 2020.

Social media used for political advocacy may only be in its infancy, and the digital activists of Hong Kong in 2019 expanded its use in ways unique to the city and its population. The fact remains that its use threatened the world’s second most powerful nation and played into the hands of a hostile and aggressive US administration focused on containment of its rival. The result was to crush Hong Kong’s immediate aspirations for democratic evolution.

Without the flamethrowers of social media, the outcome may have been the same, given the geopolitical backdrop, but it would almost certainly have taken longer and been less extreme.

Notes

- Michale R. Pompeo, “Secretary Michael R. Pompeo with Bob Cusack, Editor-in-Chief of the Hill,” interview, US Consulate General Hong Kong & Macau, July 15, 2020, https://hk.usconsulate.gov/n-2020071502/. ⮭

- Anjana Susarla, “What TikTok Teens Fooling Trump Means for the 2020 Election,” Fast Company, July 4, 2020, https://www.fastcompany.com/90523591/what-tiktok-teens-fooling-trump-means-for-the-2020-election. ⮭

- Office of the Communications Authority, the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, “Data & Statistics: Key Communications Statistics,” OFCA, accessed October 2020, https://www.ofca.gov.hk/en/data_statistics/data_statistics/key_stat/. ⮭

- Nicolle Liu and Sue-Lin Wong, “Hong Kong Mood Darkens as Hard Hats Replace Yellow Umbrellas,” Financial Times, June 14, 2019, https://www.ft.com/content/b4eb3fb6-8d87-11e9-a1c1-51bf8f989972. ⮭

- James Pomfret, Greg Torode, Clare Jim, and Anne Marie Roantree, “A Reuters Special Report: Inside the Hong Kong Protesters’ Anarchic Campaign against China,” Reuters, August 16, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/hongkong-protests-protesters/. ⮭

- Zoe Suen, “How Hong Kong’s Protest Uniform Changed a Market,” Business of Fashion, November 7, 2019, https://www.businessoffashion.com/articles/china/the-aftermath-of-hong-kongs-protest-uniform. ⮭

- Hugh Davies, “Why Is Hong Kong Such a Popular Video Game Location?” M+ Voices, October 15, 2018, https://stories.mplus.org.hk/en/blog/why-is-hong-kong-such-a-popular-video-game-location/. ⮭

- “HKU Survey Reveals Gaming Addiction Problem among Hong Kong Upper Primary Students,” press release, University of Hong Kong, June 20, 2017, https://www.hku.hk/press/news_detail_16488.html. ⮭

- Mini Metro Wiki, “Hong Kong,” Fandom, accessed December 22, 2020, https://mini-metro.fandom.com/wiki/Hong_Kong. ⮭

- David Ignatius, “The U.S. Has to Tread in the Middle When Handling the Hong Kong Protests,” Washington Post, August 16, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/global-opinions/the-us-has-to-tread-in-the-middle-when-handling-the-hong-kong-protests/2019/08/15/ee89b7b0-bf88–11e9-a5c6–1e74f7ec4a93_story.html. ⮭

- Translated pithily in Cantonese as laam chau, 攬炒, or “fry with me.” Yuen Chan, @xinwenxiaojie, “Canto lesson,” Twitter, August 16, 2019, https://twitter.com/xinwenxiaojie/status/1162047384152694787. ⮭

- Christy Leung, “Hong Kong’s Controversial National Security Law Tip Line Gets 10,000 Messages in First Week of Operation,” South China Morning Post, November 14, 2020, https://www.scmp.com/print/news/hong-kong/law-and-crime/article/3109867/hong-kongs-controversial-national-security-law-tip. ⮭

- Bron Sibree, “Review: City on Fire Revisits Hong Kong’s 2019 Protests and Asks, ‘What Next’?” South China Morning Post, March 15, 2020, https://www.scmp.com/magazines/post-magazine/books/article/3074466/city-fire-revisits-hong-kongs-2019-protests-and-asks. ⮭

- Lisa Lim, “Doxxing: The Powerful ‘Weapon’ in the Hong Kong Protests Had a Petty Beginning,” South China Morning Post, November 11, 2019, https://www.scmp.com/magazines/post-magazine/short-reads/article/3036663/doxxing-powerful-weapon-hong-kong-protests-had; Sum Lok-kei, “Hong Kong Protests: With Nearly 5,000 Doxxing Complaints Since Unrest Erupted, Officials Mull New Powers for Privacy Commissioner,” South China Morning Post, January 20, 2020, https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/politics/article/3045239/hong-kong-protests-nearly-5000-doxxing-complaints-unrest. ⮭

- Lisa Lim, “Do You Speak Kongish? Hong Kong Protestors Harness Unique Language Code to Empower and Communicate,” South China Morning Post, August 30, 2020, https://www.scmp.com/magazines/post-magazine/short-reads/article/3024863/do-you-speak-kongish-hong-kong-protesters. ⮭

- Julie Zhu, “Mainlanders in Hong Kong Worry as Anti-China Sentiment Swells,” Reuters, October 30, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-hongkong-protests-mainlanders-idUSKBN1X90Q8. ⮭

- “Cathay Denounced for Firing Hong Kong Staff after Pressure from China,” The Guardian, August 28, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/aug/28/cathay-pacific-denounced-for-firing-hong-kong-staff-on-china-orders. ⮭

- Frances Yoon, “Hong Kong Draws Fewer Expats as China Curbs City’s Freedoms,” Wall Street Journal, August 6, 2020, https://www.wsj.com/articles/hong-kong-is-losing-its-charm-for-expats-as-china-tightens-the-screws-11596706202. ⮭

- “New Book Announcement: ‘No Third Person: Rewriting the Hong Kong Story’ by Christine Loh and Richard Cullen,” Asian Review of Books, October 1, 2018, https://asianreviewofbooks.com/content/new-book-announcement-no-third-person-rewriting-the-hong-kong-story-by-christine-loh-and-richard-cullen/. ⮭

- Wong Tsui-kai, “Hong Kong Protests: What Are the ‘Five Demands’? What Do Protestors Want?” South China Morning Post, August 20, 2019, https://www.scmp.com/yp/discover/news/hong-kong/article/3065950/hong-kong-protests-what-are-five-demands-what-do. ⮭

- The five demands remained “five” even after the first one was met, for withdrawal of the extradition bill. The other four were to call a commission of inquiry into alleged police brutality, retraction of the use of the word rioters to describe protestors, amnesty for arrested protestors, and universal suffrage for both the Legislative Council and chief executive of Hong Kong. ⮭

- Rowena He, “To Lead or Not to Lead: Campus Standoff in Hong Kong’s Water Movement,” Journal of International Affairs 73, no. 2 (Spring/Summer 2020), 119–34. ⮭

- Bat got zik in Cantonese, 不割席. ⮭

- Wee Kek Koon, “Why Hong Kong’s Protestors Do Not Want to ‘Cut the Reed Mat’—They Believe They Are Stronger Together,” Post Magazine, September 12, 2019, https://www.scmp.com/magazines/post-magazine/short-reads/article/3026830/why-hong-kongs-protesters-do-not-want-cut-reed. ⮭

- He, “To Lead or Not to Lead.” ⮭

- Denise Tsang, “United States Ending Hong Kong’s Special Trading Status Will Hurt US Firms, City’s American Chamber Of Commerce Says,” South China Morning Post, July 17, 2020, https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/hong-kong-economy/article/3093573/united-states-ending-hong-kongs-special-trading. ⮭

- Owen Churchill, “US President Donald Trump Signs Hong Kong Autonomy Act, and Ends the City’s Preferential Trade Status,” South China Morning Post, July 15, 2020, https://www.scmp.com/news/world/united-states-canada/article/3093200/donald-trump-signs-hong-kong-autonomy-act-and-ends. ⮭

- The original Magnitsky Act, or the Russia and Moldova Jackson-Vanik Repeal and Sergei Magnitsky Rule of Law Accountability Act of 2012, was named for Sergei Magnitsky, a Russian tax lawyer who died in a Moscow prison cell after investigating a $230 million fraud involving Russian tax officials. ⮭

- Paul Wolfowitz and Frances Tilney Burke, “Hong Kong Sanctions with Teeth,” Wall Street Journal, June 2, 2020, https://www.wsj.com/articles/hong-kong-sanctions-with-teeth-11591119841. ⮭

- Iain Marlow and Natalie Lung, “Hong Kong Leader Carrie Lam Has Credit Card Trouble after U.S. Sanctions,” Bloomberg, August 19, 2020, https://www.bloombergquint.com/global-economics/hong-kong-s-leader-has-credit-card-trouble-after-u-s-sanctions. ⮭

Author Biography

Anonymous is a former foreign correspondent, author, and commentator based in Hong Kong since 2000. Fluent in Chinese and Japanese, Anonymous has lived across Asia including in other countries where political changes have led to sharp reversals in basic freedoms and economic conditions, for better or worse. As a front-row observer of Hong Kong’s changing politics, the writer was forced to adopt anonymity for this article due to reservations by third parties about its impact on clients and employees.