Leonard Volk’s disposition of his first casts of Lincoln’s face and hands is undoubtedly the crux of any account of his Lincoln sculptures. In the most direct statement of the matter, Volk wrote that he had presented his “original life casts” of Lincoln “to my son who sold them to some subscribers in New York.” The original casts were then “presented by them to the Smithsonian Museum.” Volk went on: “When residing in Rome the last time,” in 1870–72, “I had Malpricari, the noted formitore in plaster, make careful moulds from these originals, and when I came home I brought with me the originals and moulds.” Volk then referred to three copies that he made from Malpricari’s moulds: “Soon after 1873, probably, I cast the first replicas which I now have. At the request of my son, then in Paris, I sent him the 2nd replica which he presented to his Prof. in the Beaux Arts, M. Gerome, and [he gave] the 3rd replica of the face cast to his friend Wyatt Eaton.” In other words, Leonard Volk distributed the three replicas as follows: He retained the first one, which later went to Douglas Volk and which they usually referred to as the “artist’s copy.” Douglas presented the second replica to Jean-Leon Gerome (1824–1904), in whose Paris studio he trained. And Douglas gave the third replica to Wyatt Eaton, his fellow student.2

Knowing the value of his original Lincoln casts, Volk guarded them carefully. Indeed, he kept them in his immediate possession on four voyages across the ocean, as he went to and from Italy in 1868–69 and 1870–72. Thus, fortunately, he had these casts with him in Rome in 1871, when the great Chicago Fire consumed the contents of his studio.3

In 1872, after Leonard Volk, his wife, and daughter had returned from Rome to Chicago, Douglas Volk pursued on his own his education as a young American artist in Europe. “I suppose you are getting used to being alone by this time,” the father wrote his 15-year-old son. “Be diligent in your studies, remembering that your opportunities at present are the best in the world for acquiring a knowledge and a start in your art.” Leonard Volk added, perhaps recalling his own hardscrabble youth: “There are but few boys indeed who have such glorious privileges of all the freedom of a man, to act and decide for your self and lay out your pleasant work and studies as best suits your tastes.”4

The Gerome Replica

Douglas Volk entered Jean-Leon Gerome’s atelier at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, after briefly studying with other painters in Venice, Rome, and Paris. With several friends who were also to make their mark in American art, he trained with Gerome from 1873 to 1879, interrupting his education only in 1876, when he made a trip home to Chicago and visited the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. A photograph of L’atelier Gerome at this time shows more than fifty young men. Gerome was an immensely influential instructor, inspiring his students without expecting them to imitate him. Volk himself began by painting scenes of Puritan life in colonial New England which were in effect “as chaste a domestication of Gerome’s exotic almehs as might be imagined.” Yet, as Volk later wrote, he doubted “if any master of our times was held in greater reverence by his pupils than Gerome. In fact, this feeling amounted almost to an overwhelming awe.” Volk named one of his sons Gerome, and presented to his mentor, upon returning to his studio in 1876, “the first duplicate of the mask which ever left our possession.” Douglas Volk was referring to one of the three replicas that his father had made from the original cast of Lincoln’s face. In making this gift, he wrote, “I did all I could to show my gratitude to him for the years of instruction he gave me.”5

Gerome duly acknowledged the replica that Douglas Volk had given him, “but it seems that his sentiments were from the tongue only or he would not so soon have parted with it.” Gerome parted with the cast by giving it to Truman H. Bartlett, another American artist in Paris, about twenty years older than Volk. By the late 1870s, Bartlett had begun a wide-ranging career as a sculptor, art critic, and art teacher, which included 22 years as an instructor in drawing and modeling at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. One of Bartlett’s many interests was Lincoln, and he assiduously collected material for his study of “The Physiognomy of Lincoln” and “An Essay on the Portraits of Lincoln.”6

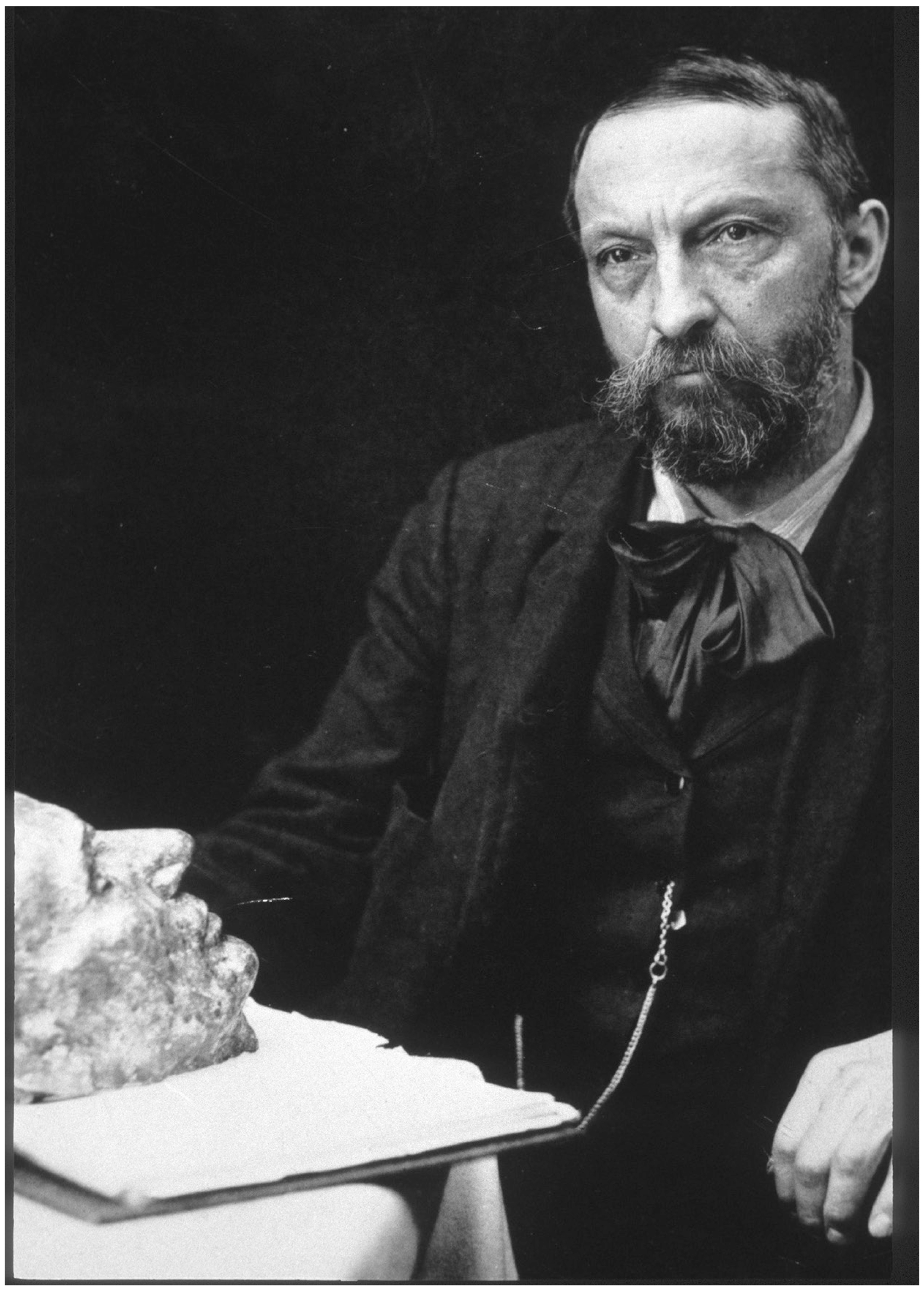

In a photograph at the time (Figure 1), Bartlett is shown contemplating the Volk cast that Gerome had given him. Bartlett could be severely critical of Leonard Volk. Although his plaster copy of the Lincoln mask was “wonderful,” it was “all due to perfect firmness of the muscles of his face, even when supporting a more than usual thickness of plaster.” Unfortunately, “Volk was not an adept in doing such work.” Moreover, Bartlett remarked, “Mr. Volk left no estimate of how Lincoln impressed him,” perhaps because, for Volk, making Lincoln’s bust was “a purely business enterprise.” Yet the Gerome replica put Bartlett in touch with Douglas Volk for many decades.7

The Eaton Replica and the Gilder Subscription

Douglas Volk gave the second replica of his father’s original Lincoln casts to his close friend Wyatt Eaton (1849–1896). In the mid-1870s, Volk and Eaton were fellow students in Paris, living at the same address, and, upon returning to America, they both offered classes in painting at the Cooper Union in New York. With such close connections, it was natural for Volk to give Eaton one of the three replicas of his father’s Lincoln mask. And it was that replica that prompted Richard Watson Gilder (1844–1909), editor of the Century, to initiate a subscription by which to acquire Leonard Volk’s original Lincoln casts for presentation to the National Museum.8

“In the winter of 1886,” Gilder explained to Homer Saint-Gaudens, the son of Augustus Saint-Gaudens, “I was calling on Wyatt Eaton,” who was then living in Washington Square in New York, and “on his table I was amazed to notice a mask of Lincoln … the now famous life-mask.” Having never heard of it, Gilder asked Eaton where he got it. Eaton replied that “Douglas Volk had given it to him in Paris, it having been taken” by his father “who also took Lincoln’s hands.” Gilder “thereupon got up a little committee” which included Saint-Gaudens; Thomas B. Clarke, perhaps the most prominent American art collector at that time; and Erwin Davis, who was also a collector and successful New York businessman. “We raised by subscription enough money to purchase the original cast, which we presented to the National Museum at Washington, where it has ever since been on exhibition.”9

On February 1, 1886, Gilder and the committee issued a printed handbill in which they undertook “to obtain the subscription of fifty dollars each, from not less than twenty persons, for the purchase” from Douglas Volk of the original casts taken by Leonard Volk “from the living face and hands of Abraham Lincoln, to be presented, together with bronze replicas thereof,” to the National Museum. The committee’s appeal would thus be successful if it brought in 20 subscribers at $50 each, or $1,000. But the handbill opened the way for a better return: “The subscribers are themselves each to be furnished with replicas of the three casts, in plaster or bronze. If in plaster, there will be no extra charge beyond the regular subscription of $50; if the complete set is desired in bronze, the subscription will be for $85; if the cast of the face only is desired in bronze, the hands being in plaster, the subscription will be for $75.”10

The first list of subscribers contained the names of 19 individuals and 2 institutions. It included the members of the committee, of course. John Hay, Lincoln’s secretary, and another subscriber are listed c/o Gilder. Except for George W. Childs and Dr. S. Weir Mitchell in Philadelphia, John J. Glessner in Chicago, and Edward W. Hooper in Cambridge, Massachusetts, all others lived in New York. They included Alexander W. Drake, the Century’s art editor, and Allen Thorndike Rice, editor of the North American Review, as well as several bankers and other prominent men of affairs in New York. The Boston Athenaeum and the Fairmont Park Association in Philadelphia were the institutional subscribers. Of those in this initial list, 10 paid for bronze replicas and 6 for plaster. “The scheme for buying the mask of Lincoln by Mr. Volk has succeeded,” Gilder later wrote Truman Bartlett, “but the list is not yet quite closed.” Others who finally subscribed included, besides the Century Company, Benjamin Altman, J. L. Cadwalader, William Carey, George M. Eddy, Walter Howe, Henry E. Howland, B. Scott Hurtt, P. J. Koons, Enoch Lewis, R. J. Lyle, J. W. Mack, Payson Merrill, Jacob Schiff, F. M. Stimson, William Thomson, Alexis Turner, and J. Q. A. Ward. In this group, Douglas Volk may have enlisted Ward, another sculptor. Leonard Volk made a particular effort to secure a set of the casts for “the old Home of Lincoln” which the custodian, Osborn H. Oldroyd, had “converted into a Museum of the most interesting relicts.” Volk thought it would be particularly appropriate if the hands were displayed “in the house where they were made,” but Oldroyd did not acquire copies for the Lincoln “Homestead” until 1890. Interestingly, the final tally included not only Henry Irving, the preeminent Shakespearean actor of the day, but also Bram Stoker, his London manager, who is now best known as the author of Dracula. In the end, 33 supporters, subscribing $1,500, made it possible for Douglas Volk and Gilder’s committee to convey Leonard Volk’s original casts and bronze replicas to the National Museum.11

Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848–1907), in his New York studio, carried out the task of making the required number of copies of the Volk casts. For the casts destined for the National Museum, he used the original molds that Leonard Volk had safeguarded since 1860. For the subscribers, however, Saint-Gaudens may have used the first casts from those molds. Writing a few years later, Leonard Volk was ambiguous: “The subscribers for purchase of originals were all furnished with replicas of hands & face in plaster & Bronze from moulds made over, or from, my first copies which I sent them for the purpose, so the originals might be preserved, intact and sharp, as when I first made them from life.” Of the three replicas made from Malpricari’s molds, it is conceivable that Leonard Volk was here suggesting that the subscribers’ copies were taken from his “artist’s copy.” It is also conceivable that the copy of the Lincoln mask in particular was taken from the replica that Douglas Volk had given to Wyatt Eaton. In modeling the face for his own statue of Lincoln for Chicago, Saint-Gaudens had written Volk for his consent to “borrow one of the replicas—that one in New York.” Saint-Gaudens, who at that time was supervising the casting of the subscribers’ copies, was probably referring to the replica in Wyatt Eaton’s possession.12

The exact path of the original casts from Leonard Volk to the National Museum also became an issue when the newspapers reported that they had been “lost” or “abandoned” by him but were finally found, “after many vicissitudes,” by Saint-Gaudens in “a cellar” of the Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York. Gilder hastened to assure Volk that Saint-Gaudens “never meant to reflect upon your or your son’s care” of the mask, “but he thought that in placing it in the basement of the Metropolitan Museum the managers of that institution did not fully realize its great importance.” Douglas Volk later wrote that his father had sent him the “originals, the life mask and two hands of Lincoln,” from Chicago to New York, that he had them “placed in an appropriate portable oak case, with a glass cover,” and that they were exhibited “for a short period” at the Metropolitan. They then became the responsibility of Saint-Gaudens, who saw to it that bronze or plaster copies were made for subscribers and a bronze set for the National Museum. Thus, months before the matter became a concern of the press, Douglas Volk could safely “presume” that “the originals are in Washington.”13

Douglas Volk surely appreciated the leadership of Gilder and Saint-Gaudens in securing the Lincoln casts for the National Museum. They had led in the formation of the Society of American Artists in 1877, Wyatt Eaton served as the Society’s secretary, and Volk was engaged with its exhibitions, all of which circumvented the established but tradition-bound National Academy of Design, founded in 1825. (Later, differences between the Society and the Academy narrowed and they merged in 1906.)14

Saint-Gaudens individualized each cast made for the subscribers (and randomly inserted periods). On the back of Gilder’s own copy of the mask are the following words, every letter capitalized (although two dates are now unclear): “This cast was made for. R. W. Gilder. subscriber/. to the fund for the purchase/and presentation to the United States/Government of the original. mask/made. in Chicago April [?] by Leonard. W. Volk from the living./face of Abraham Lincoln./This cast was taken from the/first replica of the original in New. York. City February 188[?]” The inscription on this cast for Gilder was slightly expanded on other copies, for they also noted that there were “thirty three subscribers.” Similarly, the inscription on each hand was not uniform. On the stump of each wrist are the following words, again in all caps: “This cast of the hand of Abraham Lincoln was made from the first replica of the original made at Springfield, Illinois the Sunday following his nomination to the presidency in 1860,” to which was sometimes added “Copyright 1886 by Leonard W. Volk.” The Gilder cast, made from an eight-piece mold, is preserved at the Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site in Cornish, N.H. Of the other casts, some can still be traced from owner to owner, often selling at inflated prices, while many have now come to rest in institutional collections.

That Gilder took up the subscription for Volk’s casts reflected his long-standing appreciation of Lincoln. Volk’s article on “The Lincoln Life-Mask and How it was Made” first appeared in the Century in 1881. In 1886, as if to celebrate the success of the Volk subscription, Gilder penned a poem, in the manner of a Shakespearean sonnet, “On the Life-Mask of Abraham Lincoln.” He wrote essays on “Lincoln the Leader” and “Lincoln’s Genius for Expression,” the two being issued together in 1909. He serialized a large part of Nicolay and Hay’s 10-volume Abraham Lincoln: A History before its completion in 1890. And, as the historian of his magazine put it, “a rash of Lincolniana broke out in the Century’s pages” every February.15

Casts in the National Museum

The subscription whereby Gilder’s committee obtained Leonard Volk’s original Lincoln casts for presentation to the National Museum stipulated, first, that “the originals shall never be tampered with, and that any casts taken in the future shall be from the bronze replicas and not from the original casts.” It further stipulated “that for a period of ten years, or till January 1, 1896, no casts shall be made, or permitted to be made, by the Government.” Finally, it was stated that “Subscribers will also be asked to agree that until the same date, January 1, 1896, they will permit no casts to be taken from the replicas in their possession; while during the same period Mr. Leonard Volk, or heirs, will be permitted to dispose of copies at not less than the sums paid by the subscribers.”

The foremost difficulty in initiating this subscription was Truman Bartlett’s possession of the Gerome replica of Leonard Volk’s mask of Lincoln. Late in 1885, Douglas Volk anxiously asked Bartlett “not to have any duplicates made” from that replica. Already, as Bartlett had written about himself, “An American sculptor who lived in Paris some years ago had carried a copy of Volk’s mask of Lincoln to a celebrated bronze founder to get it cast in bronze, for better preservation.” In other words, Bartlett had already obtained a bronze copy of the cast that Gerome had given him, although Volk probably did not yet know whether Bartlett had used the bronze for additional copies. But, as Volk wrote, “the existence of any number of duplicates would lessen their value.” Bartlett wrote “rot” next to this statement, but surely he must have realized that the proliferation of copies would diminish the value of the originals for Leonard Volk. Leonard and Douglas Volk were now “endeavoring to dispose of them to some museum,” and Leonard, having “with great care and some expense guarded the originals for twenty five years, intending to make use of them,” could hardly afford to part with them unless adequately compensated.16

Early in 1886, Douglas Volk wrote Bartlett again regarding the movement now “on foot to purchase the original casts of Lincoln in my possession,” for presentation to the Government. “Mr. Gilder, the editor of the Century, without a suggestion from me has undertaken, in conferring with a committee of prominent men of N.Y., to get the desired number of subscribers.” Although a number had already been secured, “Mr. Gilder says that the only thing that stands in the way of the scheme now is the fact that you possess a duplicate and have allowed others to be made from it.” In light of the stipulation that would for a period of ten years preclude subscribers as well as the Government from duplicating their copies, Volk wrote that “subscribers [would] naturally require that others be bound in the same way.” Otherwise, they would “refuse to subscribe and I thereby lose a large amount of money.” Volk continued: “There are only two duplicates” of the original casts, “father’s and one other [Wyatt Eaton’s], with the exception of the one that fell into your hands [from Gerome] and the one or two which I am sorry you gave away.” However, Volk wrote, “there is a way out of the difficulty,” namely, to have those with “the casts in question” agree to the same conditions that “the $50.00 subscribers agree to. They can not refuse this can they? And will you please consent to sign also yourself.” As Bartlett had a mind of his own, he must have erupted when he read that Volk had written “merely to satisfy the gentlemen who have the matter in hand and who need some formal assurance that there will be no further leaks.” Gilder’s scheme subsequently went forward with success, but Bartlett never subscribed to it.17

In due time, the National Museum received Leonard Volk’s first Lincoln sculptures. According to the text of the illuminated manuscript which first accompanied the casts, they were “the gift of 33 subscribers in 1888.” Inscribed on the reverse of that document was Leonard Volk’s affidavit. Given accession numbers 20084 and 61655, the Volk originals thus entered the collections of the National Museum, which had its origin as the Smithsonian Institution. With the growth of the Smithsonian, the Volk casts became the responsibility of more particular units, first the National Museum of History and Technology and then the National Museum of American History. Finally, in 1971, they were transferred to the National Portrait Gallery of the Smithsonian and accessioned as PG.71.21.18

Copies by Egberts and McGann

In 1892, a National Museum curator had to remind Truman Bartlett that “the original plaster cast of the life mask” was subject to the stipulation that “no casts were to be made, or allowed to be made, by the Government” before 1896. The Museum had also received a bronze copy of the mask, and it too was covered by the agreement for obtaining Volk’s casts. Although “the originals shall never be tampered with … any casts taken in the future shall be from the bronze replicas.” However, these provisions were not construed to keep Volk’s molds inviolable. In 1917, Richard Rathbun, who was in charge of the Museum, informed Bartlett that the Museum “cannot undertake to supply replicas from the molds in its possession,” but it “is willing to permit Mr. William H. Egberts, one of the preparators in the Department of Anthropology, to use them in making casts for you as a personal matter, and entirely outside of his official duties.” It is not known how many copies Egberts proceeded to make, although he used the Museum’s bronze replicas for the plaster casts that were subsequently displayed. He also sent Bartlett a price list for copies of “the Lincoln life mask and hands.” In white, a set would cost $6.00; with “ivory effect,” $6.50; and if “bronzed,” $7.00. Each would be a dollar more if placed on a pedestal.19

Egberts, who also offered casts of a life mask of Washington and a death mask of Napoleon, explained that the casts that he made for Bartlett were “exact duplicates of the originals. As the molds were never intended for commercial use, they were not altered.” Of course, he continued, “the ears and eye-sockets could be very much improved by alteration, but that would destroy the original work.” Clearly, Egberts believed that commercially fabricated copies of Volk’s work, which had begun to proliferate, were superior to what the original molds could provide. Such was the common assumption, then and since, even though many sculptors and curators have come to appreciate the unique value of the originals and to know that they would deteriorate with each use.20

Bartlett, who ordered only the $6 Lincoln set, was appalled by its quality. The copies were “so bad that I sent them back & protested against such reproductions.” By 1920, Bartlett had seen “a number of plaster copies made from the Gilder mould” at the National Museum. “Such is a little of what that wonderfully beautiful Life Mask of L. has suffered.” Meanwhile, as Bartlett remarked, “100s of duffers” have “tinkered over” reproductions of the mask.21

Disgusted with the reproductions made by Egberts, Bartlett turned to T. F. McGann and Sons, a foundry in Boston, which made satisfactory copies of his own bronzes. One recipient was “delighted” with McGann’s copies of the copies which Bartlett himself had taken from Gerome’s copies of the original Volk casts. As McGann correctly predicted, Frederick H. Meserve would “soon be on your trail. I think he wants a set.” Meserve, a leading collector of American historical photographs, promptly obtained a duplicate set, the mask of which Edward Steichen photographed. Steichen’s photograph, used in the works of Carl Sandburg, soon became a well-known illustration of Volk’s work.22

Bartlett and the Gerome Replica

Bartlett gave his bronze casts of Leonard Volk’s work, including the bronze cast of the plaster mask that Douglas Volk had given to Gerome, to his friend Alfred Bowditch. These casts then reached the Massachusetts Historical Society. To be precise, Alfred Bowditch’s daughter, Mary Orne Bowditch, inherited the bronzes from her father, whereupon her uncle, Charles Pickering Bowditch, on her behalf deposited them for safekeeping in the Society. Accompanied by a statement by Bartlett, these casts were reported among the gifts to the Society in 1919. Unfortunately, Mary Bowditch, who was herself a sculptor, did not receive “a formal acknowledgment” of her gift, causing her in 1948 to regret that she had failed to “keep or sell the bronzes.” The Society’s director hastened to make amends and to secure the Bowditch deposit in its collections. Thus the Society was pleased to report in 1948 that the year’s “greatest acquisition” was the Bowditch bronzes.23

In 1959, the bulk of Truman Bartlett’s papers were deposited at Boston University, not at the Massachusetts Historical Society. Although several incoming letters in that collection are important, Bartlett himself seldom kept copies of his outgoing correspondence, and what he wrote elsewhere, particularly toward the end of his life, is at times imprecise or mistaken. His papers indicate that he either gave away several Volk casts or lost track of them, and that he confused his copy of the Gerome replica with the bronze copy that he had made from it and then further duplicated. At one point, for example, Bartlett wrote that “the cast Gerome gave me was well cast in bronze;” that he left that copy with his wife; that his wife gave it to a young woman who was studying modeling in Paris; that she, “without saying a word to me” about it, carried it with her to a teaching position in Minneapolis or St. Paul; that when she suddenly died the principal of that school took possession of it; and that the principal, when contacted by a friend of Bartlett’s, was “determined to keep the bronze.” By 1920, Bartlett had quite “forgotten the name of the city or woman.” That friend also wrote about Bartlett’s bronze mask of Lincoln, having learned that “Miss Gates,” who was “in need of ready money,” sold the cast to “Miss Evers,” the principal of Stanley Hall, a school for girls in Minneapolis, who so prized it that “only real necessity” would cause her to part with it. Another account included yet more particulars: Bartlett’s wife, in his absence, borrowed money on the mask; when Bartlett failed to redeem it, it became the property of an art student from Minneapolis who was studying in Paris; financial “reverses made it compulsory for her to sell all her possessions;” a dealer in Los Angeles, acting for a new owner of the mask, offered it to the Lincoln Museum in Fort Wayne, but the Museum did not buy it. Whatever the case, Gerome’s replica of the Lincoln mask may indeed have come to rest in the Bartlett collection at Boston University.24

The Eaton Replica

The path of the replica that Volk gave his friend Wyatt Eaton is clear, unlike the Bartlett imbroglio. After Eaton’s death in 1896, his widow kept possession of his replica. She exhibited it in 1899 at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. Inscribed into the thick plaster cast is “Lincoln” in capital letters, and below it the words “L. W. Volk, fecit” and the year “1860”. Pasted behind the left ear is a red-bordered label on which is printed “M.F.A.” and on which is written both the owner’s name, “Mrs. Wyatt Eaton,” and an exhibit number, 7546. On June 4, 1900, Robert Lincoln replied to a letter from Mrs. Eaton. He did not know how many copies Volk had made of the mask “but the one you have is no doubt a perfect reproduction of his mould…. The Bust itself has always been to me one of the most satisfactory portraits of my father of this character, as it represents him before he ceased to shave his beard.”25

Not long after Wyatt Eaton’s cast of Lincoln had been exhibited in Boston, it was acquired by Henry Theodore Thomas, the son of Richard Symmes Thomas, a lawyer, newspaper editor, and Whig politician in Virginia, Illinois, to whom Lincoln had written several letters. By 1909, the younger Thomas had become “the grand old man of Zeta Psi,” active in fraternity affairs ever since 1864, when he had graduated from the University of Chicago where he was a charter member of its Zeta Psi chapter. That chapter died with the old University (before the founding of the present University of Chicago), causing Thomas to give his Lincoln collection, which included not only the Eaton mask but also a pair Lincoln hands cast by the Caproni company, to the first new Zeta Psi foundation in Lincoln’s home state, the Alpha Epsilon chapter at the University of Illinois, founded in 1909. Thomas made his donation with the understanding that his collection be exhibited to mark Lincoln’s birthday each year. With only a few exceptions, the chapter has indeed held an annual banquet, often with a Lincoln scholar as the speaker and always with a few of Thomas’s Lincoln relics on display, including the mask. Over the years, the mask, like many plaster replicas, has been chipped and its surface has become mottled, but it retains its value as an object that distinguishes Zeta Psi from other fraternities on the Illinois campus.26

The Volk Replica (“Artist’s Copy”); Berchem and Hennecke

Leonard Volk kept in his Chicago studio one of the three replicas of his first casts of Lincoln’s face and hands. By terms of the subscription of 1886 to purchase the originals for the National Museum, subscribers were not permitted to make duplicate casts of their own copies for 10 years, but Volk was not so restricted, provided that he did not dispose of such copies at “less than the sums paid by the subscribers.” Volk promptly copyrighted the Lincoln mask, probably his “artist’s copy,” and arranged with Jules Berchem, a new foundryman in Chicago, to have it cast in bronze. This collaboration is documented by the inscription on the mask: “Copyright 1886 by L.W. Volk—J. Berchem.” Later castings by Berchem omitted the founder’s name at the same time that they included Lincoln’s and the year in which the first cast was made: “A.LINCOLN/1860/L.W.VOLK-fecit.” Such wording, which Berchem also used on the stump of the hands, was often adopted by other companies which made Volk reproductions.27

Berchem had apprenticed in a Parisian foundry at the age of 9, emigrated to New York when he was 29, and settled in Chicago a year later. Doing business first as the American Bronze Company, he soon renamed it the American Art Bronze Company. His ever-expanding business came to be favored by leading sculptors of the day, giving him a solid reputation in the trade. In 1891, he cast Volk’s Lincoln atop the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument in Rochester, New York.

Foundry work was hard and hazardous. In a photograph of Berchem’s foundry, he is pictured on a framework next to begrimed workmen who are lifting a newly-cast bronze statue out of a mold. To finish it, one of them would fill his mouth with granulated powder to blow on the statue’s surface. The powder would also settle in a worker’s lungs. Such was the experience of another French emigrant, Georges Jagot, who died young.28

Volk apparently worked with Berchem to make several bronze copies of his set of Lincoln casts. When Jesse W. Weik, the Lincoln biographer, wrote to Volk in 1888, he replied that he did not wish “at present to duplicate the life mask in cheap plaster but will make replicas of it in finest bronze metal as follows—life mask of face $60, hands each $30.” In this quotation, Volk did not strictly adhere to the proviso that he or his heirs, although “permitted to dispose of copies,” were not to do so “at less than the sums paid by the subscribers” in 1886. Those subscribers had received either plaster or bronze copies of the original casts before Berchem had duplicated the replicas in Volk’s possession.29

Correspondence regarding Berchem’s casts continued after Leonard Volk’s death. In 1909, Robert T. Lincoln suggested to William M. R. French, director of the Art Institute of Chicago, that he contact Douglas Volk for permission to copy Berchem’s cast of Volk’s mask. In 1913, Berchem gave a copy of that mask to the Chicago Historical Society (now the Chicago History Museum). At about the same time, Berchem joined the Winslow Brothers as head of that company’s bronze department. The Winslow firm, which specialized in ornamental iron work, had itself merged with the Hecla Iron Works, a New York rival. After World War I, the Hecla-Winslow company discontinued bronze castings, at which point Berchem presented to William E. Barton, a prolific Lincoln scholar, the casts that he had used for his casts of the Lincoln mask and hands. Although it now seems impossible to trace more than a few Volk bronzes cast by Berchem, a complete set was found in 1979 in a Terre Haute, Indiana, pawn shop by O. Gerald Trigg, minister of a Methodist church in nearby Greencastle. That set is now in the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library.30

In 1890, Leonard Volk contracted with the C. Hennecke Company of Milwaukee to make plaster copies of his Lincoln life mask and hands as well as statuettes of his statue of Lincoln in Rochester, New York, and of Douglas at his monument in Chicago. Hennecke was to be the “sole agents and publishers” of these works for fifteen years, and Volk was to receive 25% from their sale. Hennecke also reproduced multiple versions of Volk’s draped bust of Lincoln. At one point, the company reported that it had on hand 25 busts already “packed in boxes” and 240 “not yet packed.” Many collections now contain Hennecke casts or what appear to be anonymous copies of them.31

Casper Hennecke emigrated from Germany to Milwaukee in 1865, and opened a Chicago office in 1888. His company specialized in making plaster casts of antique sculpture, especially for schools, and it labeled its products. To do so, it either impressed on its cast of Lincoln’s right hand, at the stump of the wrist, the words “C. Hennecke Co./Formators/Milwaukee, Wis.” or it affixed an oval brass plate which read “A. Lincoln. From Life./By L. W. Volk, 1860./C. Hennecke & Co./Mnfrs. & Sale Agents/Milwaukee & Chicago.” Describing this hand more particularly, the company’s brochure pointed out both “its swollen muscles after the hand-shaking” and “its wedge-making scar on the thumb.” The Hennecke company made brackets and pedestals for displaying its busts. To its Lincoln mask and hands, it attached a string for hanging them as Leonard Volk and others had done. Shortly after Leonard Volk died, Douglas Volk wrote the Hennecke company, thinking that it had retained “the originals of mask and hands of Lincoln.” Such, however, was not the case, for the company had already informed him that his father has “allowed us to have the originals only long enough to enable us to take our mould, when they were immediately returned to him.” Thereinafter Douglas Volk referred to the “artist’s copy” of these works as being in his own possession.32

Volk’s Memoirs

Although Chicago’s newspapers often took note of Leonard Volk’s activities as a sculptor, it was Century that brought his Lincoln work to the attention of a national audience. In 1881, it published “The Lincoln Life-Mask and How It Was Made,” an article extracted from the sixth notebook of his “memoirs,” a manuscript which also has been referred to as his “reminiscences” or “autobiography.” Volk explained the matter to Truman Bartlett in 1892: “The memoirs I have ready [to be] typewritten for publication terminating in 1886, but [I] shall not publish till I have added something more and made some modifications, in fact [I] had rather it would appear, if at all, after departure to the unknown ‘Round-up’!” The manuscript of Volk’s memoirs provides a long, rambling autobiographical account of his life, with ample attention to the haunts of his youth, his voyages to and from Europe, and his experiences as a tourist there. Although it throws light on his personality, it contains little about his development as a sculptor or the circumstances of his commissions. Volk intermittently kept pocket diaries after 1886, but he never used them to continue his memoirs. Early in 1895, S. S. McClure, over his own signature, wrote to Volk several times, hoping “to get some extracts from your memoirs to use” in his magazine “before they are printed in book form.” Volk soon forwarded the manuscript, which Ida Tarbell then read with an eye toward using parts of it for another article on Lincoln that she would prepare for McClure’s. But she found only about 5,000 words about Lincoln “not used in the Century,” and only about half of those, “but not more,” would she be able to use. She wrote Douglas Volk about this in the fall of 1895, his father having died the previous summer. In the end, McClure’s only published two photographs of the life mask, which Ida Tarbell described as “the most perfectly characteristic portrait we have of Lincoln when first elected President.” She saw in the mask “the kindliness of its lines, the splendid thoughtfulness of the brow, the firm yet sweet curve of the lips, and, particularly, the fine expression of dignity and power.”33

In his last years Leonard Volk kept busy in his studio except for summers in Osceola, Wisconsin, where he and his son had camped and where he had a second studio. Volk had David Richards, another Chicago sculptor, sculpt both a bust and a statue of himself. That statue was exhibited at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, as was a set of Lincoln’s face and hands cast by Berchem’s American Bronze Company. After Volk’s death in 1895, the statue was placed at his grave in Chicago’s Rosehill Cemetery, where it depicts Volk resting on a rocky ledge, walking stick in hand as if at the end of a long walk through life.34

Douglas Volk and Caproni Copies

In the late 1890s, Douglas Volk and his wife, Marion Larrabee Volk, acquired property on Lake Kezar, near Center Lovell, Maine. They renovated a farmhouse there, using oaken timber (hence calling it “Hewnoaks”), built a cottage for their boys (“Viking Court”), a studio for Douglas, and a boathouse. Such were the structures on the property in 1901, when it was sketched by their son, Wendell Douglas Volk. Many friends visited the Volks at Hewnoaks, including, for instance, George de Forest Brush, one of Douglas Volk’s compatriots in Paris.35

As popular interest in Lincoln escalated with the approach of the centennial of his birth in 1909, Douglas Volk and his family quickened their link to Lincoln. In 1907, Wendell Volk advertised Leonard Volk’s premier work. Under a letterhead embossed with the words “The Lincoln Life Mask,” he offered “an authenticated cast of the great emancipator’s face rather than one of doubtful origin or from a poor mold.” Skilled in woodworking, Wendell Volk mounted the mask on an oak plaque and surrounded it with a carved “decorative laurel wreath” of his own design. Affixed to the plaque was an excerpt from his grandfather’s account of casting Lincoln’s face and a certificate of authenticity signed by his father. So prepared, plaster copies of the mask sold for $35, and bronze copies for $90. A cast of either the right or the left hand cost an additional $10 in plaster and $50 in bronze. “By direct comparison with the original cast,” Douglas Volk “remodeled and restored” a number of right hands, which were similarly mounted on oak and authenticated.36

In 1911, Douglas Volk wrote J. Pierpont Morgan, attempting, unsuccessfully, to interest him in buying for $5,000 a cluster of Volk family treasures for presentation to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. They included the “artist’s copy” of the mask, the chair on which Lincoln sat for his bust in 1860, an “absolutely sharp” short bust, and the sculptor’s memoirs. Meanwhile, he sought to interest several foundries in casting his father’s work in bronze. He sent the models of Lincoln’s hands to the Henry-Bonnard Bronze Company in New York, which assured him that it would “insert a lap of wire in the wrist of each hand by which to hang them,” just as had been done with many plaster copies. Repeatedly between 1909 and 1929, he engaged Riccardo Bertelli’s Roman Bronze Works in Brooklyn to cast the Lincoln hands, mask, and bust. Facilitating these arrangements was Roland Knoedler, a leading art dealer with whom Douglas Volk routinely consigned his own paintings. In 1914, Volk had occasion to explain to Knoedler that the Roman Bronze company had cast a copy of the Lincoln bust “directly from my father’s personal or ‘artist’s copy,’” and “not over a couple more have been made from this particular cast so far.” Thus “the bronze you see is very sharp.”37

Douglas Volk also dealt with the New York firm of S. Klaber & Co., “artistic marble & bronze workers,” which manufactured casts of Lincoln’s hands and the short bust. With the Lincoln centennial approaching, Klaber issued the Bust of Lincoln Modeled from Life,” an undated leaflet which contributed to the growing popularity of the short bust. In 1914 the Theodore B. Starr company gave a Klaber cast of the bust to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Derivatives of the short bust, some taken from the Metropolitan’s copy, are now quite widely available, perhaps more so than any other piece of Lincoln sculpture.38

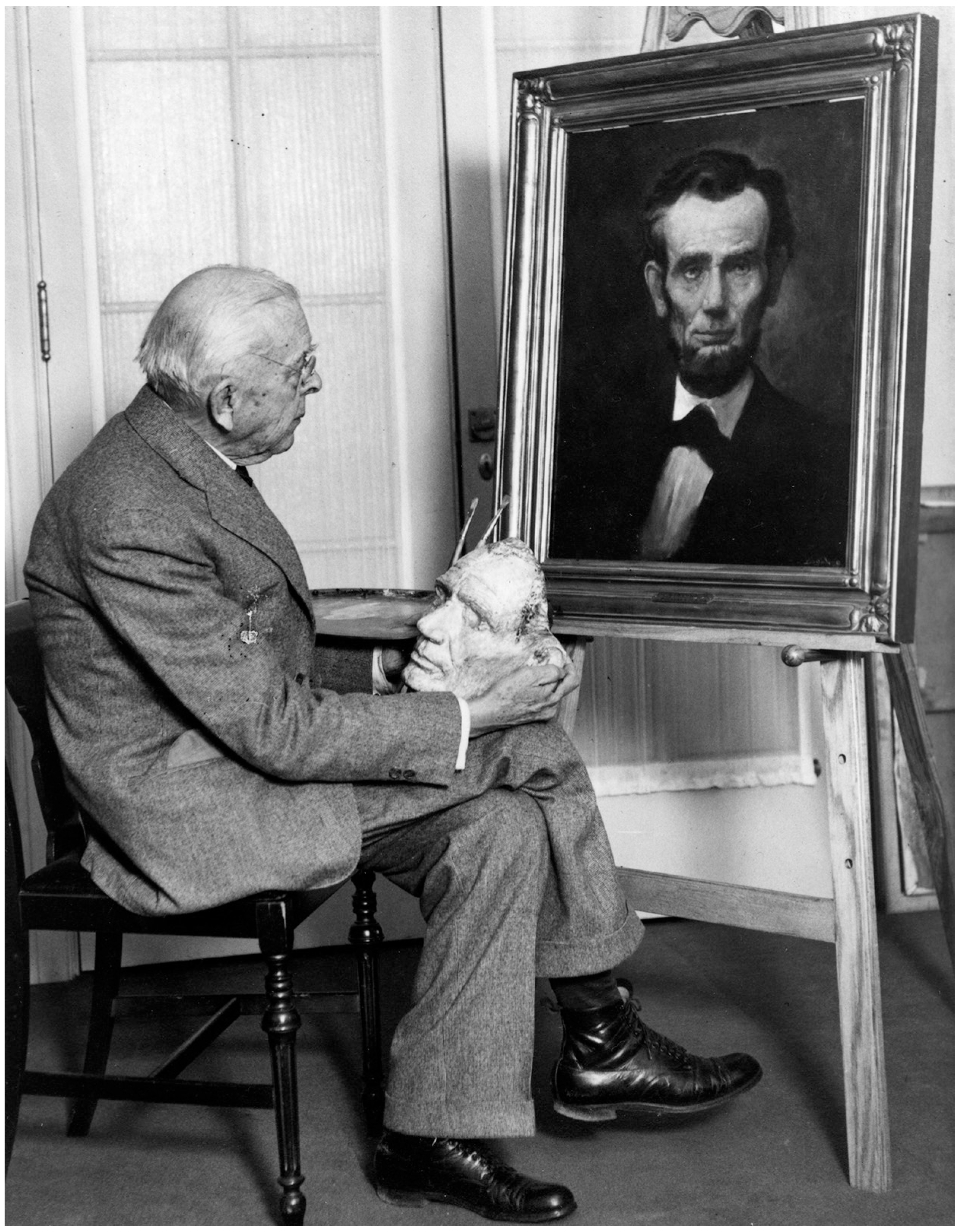

Lincoln was an abiding presence in Douglas Volk’s life. Photographs of him show him gazing reverently at a copy of the Lincoln life mask that he holds (Figure 2). As an artist, he came to specialize in portraits of Lincoln. Museums acquired at least six of these portraits, one of which was used for a U.S. Post Office four-cent stamp between 1954 and 1963. Volk destroyed other canvases as not measuring up to his conception of Lincoln, and a few were auctioned off at the Cyr auction in 2006, including one in which he expressed his reverence for Lincoln by picturing a cross in the background.

In 1917, wishing to write up the history of the Lincoln life mask, Truman Bartlett put a number of questions to Douglas Volk. Bartlett was deflected by Volk’s reply that “I myself have been engaged for some time in preparing a brochure on this subject…. I shall have to ask you, therefore, to wait for the information you ask until I can complete the task which I have long had in hand.” In 1920, Volk again deflected Bartlett, but not without asking him about the replica that Gerome had given him: “I am a little hazy as to the history of it after leaving his hands.” Others, too, had trouble unraveling the story of the casts. In 1928, when a friend of Volk’s abandoned the effort, she could only declare “What strange misconceptions attach to historic relics!” Douglas Volk, in preparing to speak locally to several schools and groups, scrambled the pages of his father’s memoirs relating to Lincoln, and when he died in 1935 he left only fragments of his own account. As for Leonard Volk’s memoirs, the full manuscript was never published, although his article in Century in 1881 has been reprinted many times and parts of it are often quoted.39

It would appear that at no point in his life did Douglas Volk correspond with the Caproni company, the leading American manufacturer of plaster reproductions in his day. Yet Caproni cast countless copies of Leonard Volk’s Lincoln works. Pietro Caproni’s company in Boston was a much larger enterprise than the Berchem and Hennecke companies in the Midwest. Formed in 1892, and continuing well into the 20th century, P. P. Caproni and Brother (Emilio), and their successors, expanded the market for plaster replicas of ancient and modern sculpture, examples of which still fill niches or sit atop bookshelves of many schools and libraries. Lorado Taft, Chicago’s most prominent sculptor after Volk, recognized Caproni’s success in popularizing sculptural works: “When I am in Boston I generally visit the Museum of Art; I always go to the Caproni shops.” The Caproni company, like its smaller competitors, usually identified its work by placing its name in the plaster, for instance by embedding its hallmark in the base of a bust. It also manufactured sculptural composites, one such being a Lincoln head by Max Bachmann placed on the body of Lincoln as sculpted by Saint-Gaudens, and it often bronzed its plaster copies.40

Over the years, the Caproni company imprecisely and freely sold several models of Lincoln busts by Volk and others. Its catalog in 1900 pictured a bust “by Volke” and in 1907 it was sued by Truman Bartlett for an unauthorized reproduction. In its copies of Volk’s works, Caproni especially favored the toga-clad bust of Lincoln, varying from time to time the width of the shoulders and the arrangement of the drapery. The company outdid itself in 1909 with a “Special Circular for the Lincoln Centenary” which offered from the Volk Lincoln oeuvre four busts, two bas reliefs, the two hands, and, most notably, the Volk mask mounted against an upright backing. Caproni marked each piece, using in different combinations the words Lincoln, mask, Volk, and 1860. Most of the Lincoln casts sold by Caproni in 1909 were also advertised in that year by a rival, Rafaello Gironi of the Boston Sculpture Company, which was located in Melrose, Massachusetts. For instance, Gironi marketed a Volk mask with upright backing, the design of which made it possible to hang the piece on a wall. That design was used in recent years when a collector obtained a copy from an antique shop, had a foundry cast it, created a website for selling copies, and, for a time, made reproductions available to the Lincoln Forum, to use as an award at its annual program in Gettysburg.41

In recent decades, numerous companies, becoming as prominent as Caproni had been, have used diverse materials to manufacture approximations of Volk’s work. Products of the Mazzolini Artcraft Company of Cleveland, Ohio, and “Alvastone” copies made by Alva Museum Replicas of New York are particularly ubiquitous, although other firms are also represented online or in museum shops. For many years, Mazzolini made Volk copies for the Lincoln National Life Insurance Company. Lincoln National had taken its name with Robert Lincoln’s approval, and Arthur Hall, who led the company, strengthened the association by supporting the Lincoln Museum in Fort Wayne, Indiana, and by selling Mazzolini copies of the Volk hands, mask, and bust to the company’s agents, who in turn presented them to their “valued clients.”42

Conclusion

“Genial, modest, enthusiastic, devoted to his art”—and fortunate to have sculpted Lincoln in 1860—Leonard Volk remained “hale and erect” until he died in 1895. As Chicago’s first professional sculptor, he stood out among the city’s many early painters who vied for attention, and was thus positioned to lead the city’s artistic community. Yet in the literature on American sculpture, Volk has never been studied as closely as several other artists who are mainly associated with Eastern states. The one exception to this generalization, however, are Volk’s Lincoln works, the history of which has always been incomplete and often mistaken. His Lincoln casts have appeared in untold numbers since 1860, but even then pirated copies have complicated their history. That reproductions continue to proliferate, however, is indisputable evidence of his singular and enduring success.43

Notes

- Part I of the article appeared in the preceding issue of this Journal, 41:2 (Summer 2020). ⮭

- Leonard Volk to Truman H. Bartlett, Nov. 23, 1892, Bartlett Papers, Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center, Boston University Archives (hereinafter Bartlett Papers). In quoting Volk’s enumeration of the replicas of his casts, as in quoting him elsewhere, it is sometimes necessary, for clarity’s sake, to turn a dash into a period, to capitalize the first word of a sentence, and to insert a few commas. ⮭

- Volk to editor, Chicago Tribune, Oct. 22, 1887, p. 15, col. l. ⮭

- Leonard Volk to Douglas Volk, Aug. 25, 1872, author’s collection; exhibitions of the Chicago Interstate Industrial Exposition and the Chicago Academy of Design, 1873–76, indexed under Volk in James L. Yarnall and William H. Gerdts, The National Museum of American Art’s Index to American Art Catalogues from the Beginning through the 1876 Centennial Year (Boston: G. K. Hall & Co., 1986), vol. 6. ⮭

- H. Barbara Weinberg, The American Pupils of Jean-Leon Gerome (Fort Worth, Tex.: Amon Carter Museum, 1984), 102; Douglas Volk to Truman Bartlett, Oct. 30, 1885, Bartlett Papers. For a photograph of Gerome’s students in 1873, see Will H. Low, A Chronicle of Friendships, 1873–1900 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1908), opp. p. 42. ⮭

- Douglas Volk to Truman Bartlett, Oct. 30, 1885, Bartlett Papers; Bartlett, “Physiognomy,” McClure’s Magazine, 29:4 (Aug. 1907), 391–407, and “Portraits,” published with Carl Schurz in Abraham Lincoln: A Biographical Essay (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1907), 5–38. ⮭

- Clipping from a Detroit newspaper of Dec. 16, 1894, in Bartlett Papers; Bartlett to the editor, Boston Evening Transcript, March 12, 1917, reprinted in Magazine of History with Notes and Queries, 41:1 (1940), Extra Number 157, p. 15; Bartlett’s notes on Volk’s Century article [“The Lincoln Life-Mask and How It Was Made,” Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, 23:2 (Dec. 1881), 223–28], Bartlett Papers. ⮭

- Weinberg, American Pupils, 102; Chicago Academy of Design, Exhibition (1880), Catalogue #40, filed with miscellaneous Academy publications, Chicago History Museum; Scribner’s Monthly, 15:4 (Feb. 1878), frontispiece. Eaton’s portrait of Volk is pictured in Arlene M. Palmer, “Douglas Volk and the Arts and Crafts of Maine,” Antiques, 173 (Apr. 2008), 116. ⮭

- Gilder to Homer Saint-Gaudens, Mar. 25, 1909, in Rosamond Gilder, ed., Letters of Richard Watson Gilder (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1916), 148–49. ⮭

- Homer Saint-Gaudens, ed., The Reminiscences of Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 2 vols. (New York: Century Company, 1913), 1:355; subscription handbill. A second printing of the handbill, on February 6, included Davis’s name. In Chicago on February 22, Leonard Volk signed an affidavit that he had taken the plaster casts of “the face and hands” of Abraham Lincoln in April and May 1860. Copies of the handbill and affidavit are in several institutions. ⮭

- Gilder to Bartlett, Apr. 30, 1887, Bartlett Papers; “Statement by Mr. Bartlett,” Massachusetts Historical Society, Proceedings, Oct. 1918–June 1919 (Boston, 1919), 52:321; initial list of subscribers, compiled by Saint-Gaudens for Clarke on May 21, 1886, in the Cyr auction; T. D. Stewart, “An Anthropologist Looks at Lincoln,” Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1952), 107:423; Volk to Oldroyd, Mar. 8, 1886, Dec. 18, 1890, Osborn H. Oldroyd Collection, University of Chicago. This footnote and several subsequent notes include a reference to the huge collection of Volk family papers which Douglas Volk preserved at his summer home near Center Lovell, Maine. Douglas Volk’s daughter-in-law, Jessie McCoig Volk (1904–2005), finally bequeathed those papers to the University of Maine, Orono. Unfortunately, the University promptly hired the Cyr Auction Company, Gray, Maine, to auction off the entire collection, one miscellaneous lot after another. James D. Cyr did so on July 19, 2006, before which he gave prospective bidders permission to photocopy a few items. All such photocopies used in this paper are cited as from the “Cyr auction.” ⮭

- Leonard Volk to Truman Bartlett, Nov. 23, 1892, Bartlett Papers (italics added); Saint-Gaudens to Leonard Volk, Aug. 31, 1887, in Chicago Tribune, Oct. 22, 1887, p. 15, col. 1. ⮭

- Volk to Gilder, Nov. 10, 1887, Cyr auction; Gilder to Volk, Nov. 14, 1887, ibid.; Chicago Tribune, Oct. 20, 1887, p. 1, col. 6; Douglas Volk, unpublished manuscript, circa 1926, in Volk Papers, Smithsonian Institution; Volk to Bartlett, Apr. 28, 1887, Bartlett Papers. ⮭

- John H. Dryfhout, The Work of Augustus Saint-Gaudens (Hanover: University Press of New England, 1982), 27–28; Henry J. Duffy and John H. Dryfhout, Augustus Saint-Gaudens: American Sculptor of the Gilded Age (Cornish, N.H.: Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site, 2003), 123. ⮭

- Arthur John, The Best Years of the Century: Richard Watson Gilder, Scribner’s Monthly, and the Century Magazine, 1870–1909 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1981), 241. ⮭

- Douglas Volk to Truman Bartlett, Oct. 30, 1885, Bartlett Papers; “Chats about People,” an article clipped by Bartlett from the Boston Post which he dated Feb. 23, 1886, and annotated by him as written by request. Ibid. ⮭

- Douglas Volk to Bartlett, Jan. 13, 1886, Bartlett Papers. ⮭

- Files relating to the acquisition and conservation of the original pieces are kept by both the Portrait Gallery and the Division of Political History of the National Museum of American History. ⮭

- F. W. True to Bartlett, Aug. 22, 1892, Bartlett Papers; Rathbun to Bartlett, Apr. 10, 1917, ibid.; Egberts to Bartlett, Apr. 18, 1917, ibid.; Ellen G. Miles, undated workfile notes relating to Volk’s work, National Portrait Gallery. ⮭

- Egberts to Bartlett, May 15, 1917, Bartlett Papers. ⮭

- Bartlett to Douglas Volk, June 5, 1920, Cyr auction. ⮭

- Chas. T. White to Truman Bartlett, Mar. 14, July 2, Nov. 12, 1917, Bartlett Papers; McGann to Bartlett, Nov. 13, 1917, Mar. 1, 1918, ibid.; Bartlett to Douglas Volk, June 5, 1920, Cyr auction; and see Frederick Hill Meserve and Carl Sandburg, The Photographs of Abraham Lincoln (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1944), frontispiece. ⮭

- Correspondence relating to acquisition #306, Massachusetts Historical Society [MHS]: Mary O. Bowditch to Stewart Mitchell (Director, MHS), May 31, 1948; MHS, Proceedings, 52 (Oct. 1918–June 1919), 320–21; Augustus P. Loring (Treasurer, MHS), by his secretary, to Mitchell, June 1, 1948; Mitchell to Loring, May 20, 1948; Paul B. Volk to Mitchell, May 19, 1948; MHS Proceedings, 69 (Oct. 1947–May 1950), 458–59. In 1927, the Society was also given another life mask made by Bartlett. Ibid., vol. 61 (Oct. 1927–June 1928), 41. See also Edward W. Hanson, Catalog #151, in Witness to America’s Past: Two Centuries of Collecting by the Massachusetts Historical Society (Boston: MHS and Museum of Fine Arts, 1991). ⮭

- Bartlett to Volk, June 5, 1920, Cyr auction; Emily S. Chapman to Bartlett, Oct. 26, [1920], Bartlett Papers; Harry L. Remster (Flotsam & Jetsam, Los Angeles) to M. A. Cook (Librarian, Lincoln National Life Insurance Company), Feb. 21, 1940, digitized in “Statues of Abraham Lincoln: Leonard Wells Volk: Lincoln’s Face,” frames 64–67, Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection, Allen County Public Library (hereinafter Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection); Eric McHenry, “Saving Face,” Bostonia: The Alumni Quarterly of Boston University,” Spring 2000. Ironically, in 1890, when Volk’s own copy of Lincoln’s left hand was apparently stolen from his studio during a fire in McVicker’s Theater Building, and before it was recovered, he sought to borrow the National Museum’s cast so as to duplicate it. “Life Cast of Lincoln’s Hand Gone; Probably Stolen the Night of the McVicker Theater Fire,” Chicago Sunday Tribune, Oct. 5, 1890, p. 10, col. 2. ⮭

- “Contributions to the Loan Exhibitions,” Trustees of the Museum of Fine Arts, Twenty-Fourth Annual Report (Boston, 1900), 146; Robert T. Lincoln to Mrs. Eaton, Robert T. Lincoln letterpress books, 34:260 (roll 57), Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library. ⮭

- The Zeta Psi mask is photographed in J. G. Randall, Lincoln, the President, 4 vols. (New York: Dodd, Mead, 1945–55), 1:11. ⮭

- Mark E. Neely, Jr., “A Life Mask Discovered” and “The Berchem Connection,” in Lincoln Lore, no. 1701 (Nov. 1979) and no. 1706 (Apr. 1980). ⮭

- “Artist-Foundryman Learned His Trade in France,” The Foundry, Jan. 15, 1930, p. 101; “Art Bronze in America,” The Monumental News, 5:1 (Jan. 1893), 29; Lewis Waldron Williams, II, “Commercially Produced Forms of American Civil War Monuments” (M.A., University of Illinois, 1958), 91; Ted Barnes (Jagot’s grandson), interview, Aug. 22, 1996. ⮭

- Volk to Weik, May 15, 1888, quoted in A. F. Hall (Lincoln National Life Insurance Co.) to Benjamin W. Morris (Parke-Bernet Galleries), Nov. 5, 1941, in “Statues of Abraham Lincoln: Lincoln’s Face and Hands,” frame 25, Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection. ⮭

- Lincoln to French, Sept. 25, 1909, Robert T. Lincoln letterpress books, 43:277 (roll 75); William E. Barton, “How Abraham Lincoln Looked,” Dearborn Independent, 26:16 (Feb. 6, 1926), 20–21, 31. ⮭

- Agreement between Leonard Volk and C. Hennecke Co., Oct. 24, 1890, in The Lincoln Life Mask, Hands, Bust and Statuette, a 16-page booklet (Milwaukee and Chicago: C. Hennecke Co., 1891); C. Hennecke Co. to Volk, Mar. 26, 1894, Cyr auction; and see The Lincoln Centenary … Abraham Lincoln in Sculpture, an 8-page leaflet (Milwaukee: Hennecke Studios, 1909). ⮭

- C. Hennecke Co. to Douglas Volk, Dec. 23, 1895, Jan. 6, 1896, Cyr auction. ⮭

- Volk to Bartlett, July 3, 1892, Bartlett Papers; McClure to Leonard Volk, Feb. 2, Mar. 27, Apr. 5, May 9, and May 18, 1895; Tarbell to Douglas Volk, Sept. 23, Nov. 30, 1895, Cyr auction; Tarbell, “Great Portraits of Lincoln,” McClure’s Magazine, 10:4 (Feb. 1898), frontispiece, 339, 345. ⮭

- Helen Douglass to Leonard Volk, Mar. 14, July 5, 1895, Cyr auction; William Armstrong, “The Great Sculptor: Leonard Volk, the Eminent Western Artist in His Studio,” The Banner of Gold, 3:13 (Apr. 1, 1893), 104; Agreement between Richards and Volk, Oct. 30, 1892, Cyr auction. ⮭

- “Famous Persons at Home CXII, Douglas Volk,” Time and the Hour (Boston, Mass.) 9:19 (Apr. 15, 1899), 6–7; Douglas Volk interview by DeWitt Clinton Lockman, transcript in “Interviews of Artists and Architects Associated with the National Academy of Design, 1926–1927,” New York Historical Society, as microfilmed by the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, frames 845–891 (frame 861 on Brush); Nancy Douglas Bowditch interview by Robert F. Brown, Jan. 30, 1974, Archives of American Art. ⮭

- Wendell D. Volk to Melville E. Stone, Sept. 4, 1907, Cyr auction; Douglas Volk, printed statement, Dec. 23, 1908, ibid. ⮭

- Volk to Morgan, Oct. 9, 1911, Cyr action; Eugene F. Aucaigne (Henry-Bonnard) to Douglas Volk, Apr. 25, 1902, ibid.; Invoices and letters, Roman Bronze Works to Volk, ibid.; Knoedler to Volk, Jan. 15, 1914 (photocopy of a letter in the files of Knoedler & Company before it closed in 2011). ⮭

- S. Klaber & Co. to Douglas Volk, July 8, 1909, Mar. 25, 1910, Mar. 20, 1912, Cyr auction; Bulletin of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 9:7 (July 1914), 168; Thayer Tolles, ed., American Sculpture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1999), 1:122–24. ⮭

- Bartlett to Volk, Mar. 15, 1917, Cyr auction; Volk to Bartlett, Mar. 27, 1917, June 2, 1920, Bartlett Papers; Marian Huddleston Miller to Volk, Oct. 2, 1928, Cyr auction. ⮭

- Lorado Taft to Paul L. Crabtree, Jan. 21, 1933, in Capronicasts, no. 5; Richard E. Hart, ed., Lincoln in Illinois: Commemorating the Bicentennial of the Birth of Abraham Lincoln, February 12, 2009 (Springfield: Abraham Lincoln Association, 2009), 100–101. ⮭

- Caproni cast no. 13526; Mark D. Zimmerman, “The Abraham Lincoln Plaster Life Mask of 1860,” Lincoln Herald, 112:1 (Spring 2010), 31; Lincoln Forum Bulletin, Spring 2008, p. 11; ibid., Fall 2009, p. 8. For two printings of Caproni’s “Special Circular” see “Statues of Abraham Lincoln: Leonard Wells Volk: General Information,” frame 82, Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection. ⮭

- Hall to Morris, Nov. 5, 1941, Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection. ⮭

- “Hours in the Art Union Gallery,” Chicago Tribune, Jan. 25, 1861, p. 3A; Annie Hungerford, “An Afternoon with Leonard Volk: He Tells the Story of the Lincoln Life Mask,” ibid., Aug. 25, 1895, p. 41, col. 1. ⮭