In February 1859, shortly after the Illinois Legislature reelected Stephen Douglas over Lincoln to the U.S. Senate, the first of two successive Springfield financial scandals came to light. These twin scandals unfolded over a period of months and would be the dominant state issues during the time that Lincoln was vying for the Republican presidential nomination. The first scandal involved Lincoln’s rival and former opponent in the 1855 U.S. Senate contest, the immediate-past governor Joel Matteson, a Democrat. The second scandal involved Lincoln’s ally, the incumbent governor William Bissell, a Republican.

The scandals would attract Lincoln’s attention intermittently as he advanced his presidential aspirations. As an attorney, he provided professional services related to both. As a politician, he worked with his Republican colleagues in an attempt to limit the damage of the second scandal, and when the state treasurer resigned, he worked to have one of his own allies appointed as the replacement. Both scandals were factors during the campaigns of 1860. After the election, the scandals tainted two of Lincoln’s Springfield presidential appointees. The scandals later led to reforms in Illinois’s next state constitution.

This article tells the story of the two scandals and their repercussions. The primary sources related to the scandals are somewhat fragmentary. Some correspondence has been lost, destroyed, or mis-interpreted, and all but one of Lincoln’s contemporary biographers, who had firsthand knowledge of the events, chose to ignore them. Nevertheless, it is possible to reconstruct the story of the two scandals and their influence.

The Canal Scrip Fraud

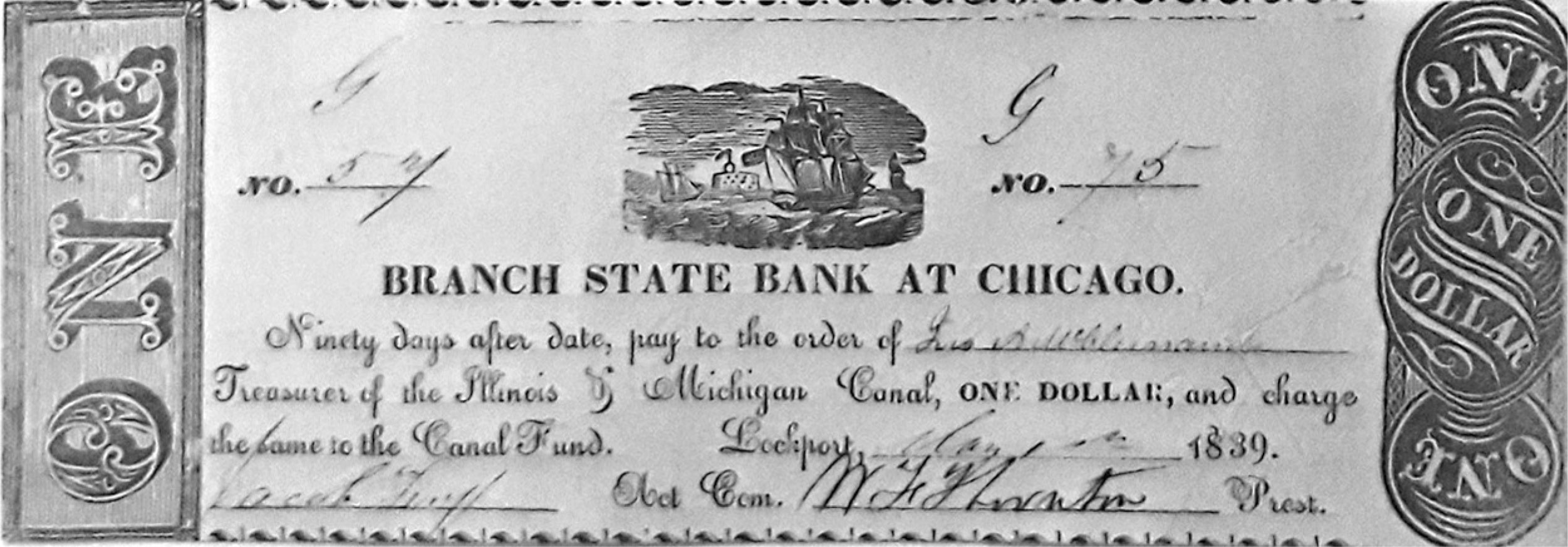

On February 2, 1859, the Illinois State Journal reported that the legislature had been notified of the possible defrauding of the state by illegal redemption of canal scrip.1 Canal scrip were IOUs the state had issued years earlier when it had run out of money during construction of the Illinois-Michigan Canal (Figure 1). The scrip was used to pay contractors who dug the canal.2 The state auditor, Jesse Dubois,3 reported that bundles of scrip were found to have been redeemed in 1857 by the immediate past governor, Joel Matteson.

On receiving Dubois’s report, the Senate authorized its finance committee to investigate.4 Lincoln together with Stephen T. Logan5 represented Matteson (one of Lincoln’s 1855 Senate opponents6) at the committee’s first hearing.7 They apparently declined to represent him further and were replaced by John T. Stuart8 and Benjamin S. Edwards,9 who, being Democrats, were politically aligned with Matteson.

It is unclear why Lincoln and Logan were asked to represent Matteson and why they were replaced at the beginning of the investigation. Despite being opponents in the 1855 election, Matteson had afterwards engaged Lincoln for various legal matters.10 Perhaps the hiring was a strategic maneuver by Matteson to help handle the Senate’s Republicans who, though they were in the minority, would be expected to be hostile. Henry Clay Whitney, the only contemporary biographer who mentions the event, offered this explanation in Life on the Circuit with Lincoln: “… the ex-Governor employed Stuart & Edwards, a celebrated firm of lawyers, and sought, likewise, to employ Lincoln and Judge Logan. Neither at first declined employment, but after mature reflection both declined, unknown to each other, both having reached the conclusion, by different routes, that the distinguished culprit was guilty.”11

The hearings were held during two weeks, a transcription being made by Robert R. Hitt, the shorthand reporter who had recorded the Lincoln-Douglas debates the previous year. Hitt’s transcription appears in the Senate record and was later serialized in the Illinois State Journal.12 The testimony showed that bundles of old scrip, having previously been redeemed and cancelled, were redeemed a second time by the former governor shortly after he left office. It was also found that he had redeemed unissued scrip, in mint condition, which had never been used to pay anyone. A bank cashier testified that he recognized the former governor, and felt obliged to redeem the scrip despite its dubious provenance.13

Both the cancelled and unused scrip had been kept in storage in the canal office in Lockport. The unused scrip had been stored in a shoebox and the cancelled scrip in a large trunk. These had been shipped to the governor at his request when he assumed office. John Nicolay, who would later serve as Lincoln’s White House secretary, was at the time a clerk for the Illinois secretary of state, Ozias Hatch. Nicolay testified that he had found what remained of the cancelled scrip in the trunk in the basement of the Capitol and that the seal on the trunk appeared to have been tampered with. The shoebox with the mint scrip was never found.14

Matteson was present at the hearings but never testified. Instead, he submitted a letter stating that, not realizing the scrip had been stolen, he had purchased it from sellers whom he could not now recall. He offered to pay back the state for its losses and encouraged the committee to continue its work in the hopes of identifying the thieves. The committee chairman incorporated Matteson’s suggestion into a legislative bill that allowed him five years to repay the state and authorized the committee to continue its investigation after the legislature adjourned.15

The payback arrangement passed the Democratic legislature nearly unanimously and was signed into law by Governor Bissell.16 Republicans felt that Matteson had stolen the scrip and should be prosecuted.17 In April, Lincoln attended the Republican State Central Committee meeting with Dubois, Hatch, and the state treasurer, James Miller, where the matter was likely discussed.18 Later that month, the Republican state officers sent a joint letter to the Sangamon County grand jury recommending an investigation and suggesting a list of witnesses.19

The grand jury convened on April 27 in the Sangamon County Courthouse and voted to investigate. The foreman of the jury was Lincoln’s longtime friend and ally William Butler.20 The jury heard from many of the same witnesses as had the Senate Finance Committee, including John Nicolay. Once again, Matteson himself did not testify. Oddly, several of the jury members were initially absent and were replaced by court bystanders. When the testimony concluded, the jury took a series of votes over two days. Initially the vote was to indict Matteson, but on subsequent votes the margin to indict shrank. Later, jurors were accused of being escorted to Matteson’s house21 between votes and accepting bribes.22 On the fourth vote, aided by all of the “bystander” jurors, Matteson was acquitted.23

Normally, grand jury proceedings were kept sealed. But Butler, who had voted consistently for an indictment, must have felt an injustice had been done. He made the unusual motion that the jury publish its proceedings. This motion passed, and the jury adjourned.24 Like the hearings of the Senate Finance Committee, the proceedings were serialized by the State Journal, which opined that the jury had been corrupted.25

The Macalister-Stebbins Bond Scandal

In early July, the second scandal came to light. The Senate Finance Committee had continued to meet as authorized. In addition to examining canal scrip, it was conducting a comprehensive review of state indebtedness. As part of its review it found that a special class of bonds the state had issued in 1841 had been improperly redeemed earlier in the year.26

The bonds in question were known as the Macalister-Stebbins bonds after the bankers who had sold them in New York on behalf of the state.27 Like canal scrip, the bonds had been issued at the height of the state’s fiscal crisis. They carried a face value of $1,000 and were supposed to pay 6% interest, but at auction they sold for only an average of $286.28 In response, when the bonds became due in 1849, an act was passed devaluing them to the purchase price plus interest. Governor Bissell, then a congressman and attorney, had represented the bond-holders in Springfield. Most of the bondholders cashed in under these reduced terms, but some held out, hoping for a better deal.29

As the state’s fiscal situation improved, the legislature passed a series of laws allowing the governor to buy back state debt.30 In 1857, with Bissell now governor, some of the holdout bondholders cited the new law and tried to sell them back to the state at face value. Governor Bis-sell refused their request. The bondholders hired Lincoln to represent them in the Illinois Supreme Court, where they sought an order directing the administration to fully redeem the bonds. The court ruled in favor of the administration, so these bonds remained unredeemed.31

In early 1859, Bissell changed his mind and directed the state’s New York agent to redeem the bonds at their face value after all. On February 4, 1859 (two days after the canal scrip fraud had been reported), the remaining Macalister-Stebbins bonds were exchanged for new bonds at par plus interest.32 Interestingly, after the fact, Bissell consulted with Lincoln and Logan regarding his bond redemption authority. They wrote back (without referencing the Macalister-Stebbins bonds or knowing of their redemption) that the acts to reduce debt were non-specific and had given the governor broad authority.33

The Democratic press pronounced the redemption illegal and demanded an explanation from the administration and a full investigation. Two Republicans responded with letters to Republican papers. Auditor Dubois explained that he had learned of the redemption only after the fact from Bissell himself and that the governor, realizing he had made an error, was attempting to have the new bonds returned.34

The second account came from State Representative Alonzo Mack, who had been appointed by Bissell as an agent to conduct the transaction. Mack was a banker from Kankakee and had been newly elected the previous fall. After winning his seat, the Joliet Signal had predicted, he would attempt to capitalize on “old claims” his bank held.35 On July 12 he wrote to the Chicago Daily Journal explaining that the redemption was initially felt to be justified under the law, but that under further review the governor “became doubtful of his authority on the matter” and that consequently the new bonds would not be recognized.36 On July 19 the Journal published an additional one-line telegram that Mack had sent from New York, “All the bonds Issued for the McCallister Stebbins bonds, will be surrendered without a cent of loss or expense to the State.”37

Years later, Secretary of State Ozias Hatch38 put the blame for the affair squarely on Mack. Hatch was interviewed by John Nicolay while collecting source material for the Lincoln biography he would write with John Hay. Hatch told Nicolay that “Mack was at the bottom of the affair.” Hatch had reported this to Lincoln, who “[t]hen getting up and stretching himself he exclaimed with his emphatic gesture of doubling one of his fists ‘I’ll be ______ if that shall be done.’”39

Lincoln Takes Action

This response would explain why on July 11 Lincoln took the unusual step of sending both a letter and a telegram to the state treasurer, James Miller, who was visiting New York. The letter argued that the governor, who was known to be suffering from a debilitating disease and could no longer walk without assistance, had been “dogged in his afflicted condition” until the bondholders had gotten their way.40 The telegram order in Lincoln’s hand was sent to Miller at “some hotel” in New York, and was direct: “For your life and reputation pay nothing on the new Macalister-Stebbins bonds.”41

On July 14, Lincoln, Logan, Hatch, Dubois, and Butler began a trip over the Illinois Central Railroad for an assessment related to a legal case involving the railroad before the state Supreme Court.42 During the week of their journey, the partisan papers continued sparring over the bond scandals. One must assume that during their trip the five men read the papers and discussed both the canal scrip fraud, with which Butler, as the former grand jury foreman, was intimate, and the unfolding Macalister-Stebbins bond scandal, from which Auditor Dubois was attempting to extricate himself.

By July 20, the railroad inspection had come to an end and members of the party were staying at the Tremont House in Chicago.43 The Chicago Times noted their presence: “During the week many Republican leaders have been in this city, caucusing about this matter. Abe Lincoln, who still hopes to hold an office, sometime, in the State, or in Washington, was here … Mr. Auditor Dubois was here. So was Mr. Secretary of State Hatch and others. One of these men was heard to say, “it is a bad egg,”—meaning the grand fraud in which our Republican State administration is implicated.”44

By July 22, Lincoln had returned to Springfield, where he found Miller’s response to his pointed telegram. “[G]ive yourselves no uneasiness, I would go to the Tomb sooner than pay one cent on Int. which is claimed on the MCallister & Stebbins Debt. The parties here holding the debt are frightened & are waiting with great anxiety to hear what will be the course decided upon by the Gov. & his counsel.”45

It is interesting to note that Miller references the course of action to be made by the “Gov. and his counsel” though the governor is not part of the conversation. This wording seems to acknowledge that Lincoln and the state officers were expected to determine the governor’s policy. The letter must not have been entirely reassuring, as they had directed Miller to “pay nothing” on the claims, and Miller only promised to not pay interest (“Int.”).

On July 28, Miller wrote a longer letter from New York to Lincoln in Springfield, retracting his earlier assurances. He argued that the Macalister-Stebbins bonds should be fully exchanged, and he reported that he understood from “Dr. Mack that Jesse K. (Dubois) & all the heads of messes were agreed that the parties here should receive bonds of our new issue …” Expressing his frustration over the mixed instructions he had received, Miller complained, “This quibling [sic] is contemptible & is very annoying to me as the agent. It carries with it a Seeming distrust in me as not being trustworthy, & is so looked upon here.”46

The Scandal Continues

In early August, the Senate Finance Committee published an interim report of its ongoing activities. The committee determined that no law warranted the Macalister-Stebbins redemption, and, moreover, it had been informed by Auditor Dubois that the new bonds had not been returned. The committee had confined its work to reviewing records, and other than the state auditor, had not questioned any of the parties involved.47

The committee report reignited the debate. Democratic papers focused on the fact that Mack had telegrammed from New York that the new bonds were being surrendered. The report showed that was not yet true.48 Republican papers pointed out that the committee had not questioned anyone besides the auditor, thus allowing them to claim that the committee had not completed its work and that former Governor Matteson and other Democrats must be involved.49

Following a political and business trip through Iowa, on which he was accompanied by Hatch, Lincoln returned home to Springfield.50 Soon after, correspondence began arriving related to the bond scandal including an August 20 bombshell letter from Treasurer Miller announcing his intention to resign and his plan to have Alonzo Mack take his place. Miller wrote, “it would be a great disappointment to me as well as deep mortification to Dr. Mack” if they could not have Lincoln’s approval, and asked Lincoln “for the light of your countenance.”51

On the same day, Ward Lamon had written Lincoln from Bloomington to say that he had received a visit from Mack. Mack had informed Lamon that Treasurer Miller was about to resign and that Mack and Leonard Swett had asked Lamon to sign a letter to Governor Bissell recommending Mack as Miller’s replacement. Lamon had joined Swett in signing the letter, but now harbored regrets.52 Lamon wrote, “Mr. Lincoln on more mature reflection, I doubt very much the propriety of appointing Mr. Mack to the office of State Treasurer in case of the resignation of Mr. Miller.” He went on to recommend Lincoln’s friend William Butler, the recent foreman of the Sangamon grand jury.53

At this point, Browning arrived in Springfield. A Republican attorney, he had been hired to assist Dubois during the canal scrip investigation. His diary implies that he, Lincoln, Dubois, Lamon, and David Davis54 were all working in concert, initially to prevent Miller from resigning, but later to prevent Mack from being appointed his successor. On August 24 Browning recorded, “Mack is in no sense fit for the office, and if the arrangement should be carried into effect it would be highly injurious to the interests of the State, & probably fatal to the Republican Party in Illinois.”55

Browning added that he had to leave Springfield, “but Judge Davis has promised me that he will stay over, prevent mischief if he can and write me tomorrow night.”56 Though Davis’s letter to Browning has not been found, Davis did send Lincoln a short note. Davis’s scrawl is difficult and the message rather cryptic. It reads, “Dear Lincoln. You need not hunt up the question of -limitation; The cheaters have filed their claims just a few days too early for me—Let it slide” In a postscript he adds, “Baker of Chicago is here, & feels we are saved a great trial.“57

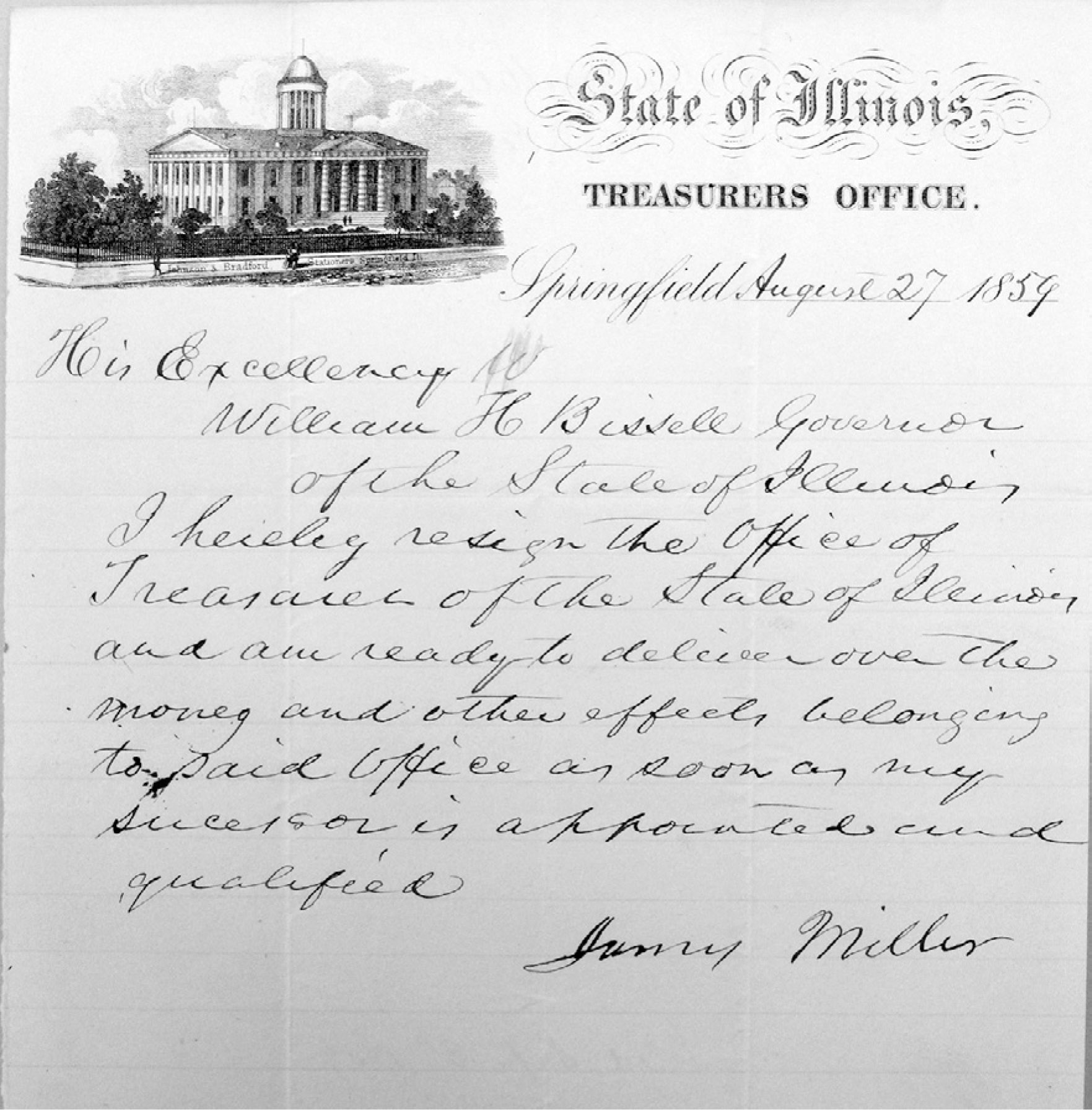

By the “question of—limitation” Davis is probably referring to the constitutional constraint on the appointment of legislators. The Illinois Constitution of 1848 expressly forbade members of the legislature from receiving any “civil appointment within this state.”58 It seems Davis no longer needed Lincoln’s assistance because Miller had been reminded of the prohibition, thereby eliminating the possibility of Mack’s accession to the office: On the day of Davis’s note, Treasurer Miller signed a letter of resignation addressed to Governor Bissell (Figure 2).59 Bissell subsequently named William Butler the new state treasurer, as Lamon had suggested. Thus, the “great trial” was averted.

Exactly how Lincoln and his allies prevented “mischief” and effectuated the appointment of Butler is unknown, but it seems that they had the governor’s ear. Perhaps one or more of them paid a visit to the governor’s residence to express their misgivings about Mack and to remind Bissell of the constitutional issue.

The resignation of the treasurer did not end the problem for the Republican administration. The Times took it as an admission of guilt and asked when Governor Bissell would address the matter, arguing that he should call a special session of the legislature to investigate.60 Miller provided a letter to Republican papers citing health reasons as the cause of his departure and denying any responsibility for attempting to fund the Macalister-Stebbins bonds. Both the Chicago Journal and the Illinois State Journal reproduced the letter on September 12 and included a statement from Dubois and the new treasurer, Butler, certifying that the office had been inspected and all the state’s accounts were in order.61

Bissell Attacked

A few months later, the Macalister-Stebbins bonds scandal was a featured theme at the January 1860 Democratic State Convention.62 Colonel James D. Morrison, a long-time rival of Bissell’s, was given prominent speaking time during the proceedings.63 Morrison recounted the entire history of the Macalister-Stebbins affair. As the speech reached its climax, he accused Bissell of “having deliberately committed outrages second only in the degree of crime to murder itself” and demanded the governor’s impeachment. Morrison then dramatically reached into his pocket and produced a collection of letters purportedly written by Bissell to an agent of the Macalister-Stebbins bondholders. According to Morrison, the letters showed that Bissell had initially refused Lincoln’s client’s request to fully fund the bonds in order to demand more of a cut for himself. Morrison had put great effort into his research, even travelling to New York to procure the letters with which to impugn Bissell.64

After the convention, the Times editorialized that the correspondence proved that the plan to fund the bonds was the result of a deliberate scheme by Bissell, not of “inadvertency” as his Republican defenders claimed.65 Two days later the Times reported that Governor Bissell was in a “rage” over the allegations made by Morrison at the convention.66

Finally, after enduring months of attacks, Bissell responded with a letter to the Illinois State Journal. In making his defense, he did not dispute the legitimacy of the documents Morrison had provided. Rather, he wrote, a key letter from the series had been purposely omitted. Had it been included, this letter would have vindicated him, because it showed he had declined the bondholders’ “dishonorable proposition” and terminated their correspondence. Morrison had conveniently ignored it because it “would blow his pitiful cobwebs sky high.”67 Bissell added that Morrison held long-standing resentment of him and that Morrison was motivated by deep-seated envy and jealousy. He suggested that Morrison had either paid for the letters or stolen them, and concluded by claiming that Morrison, a lawyer, made his living by stealing land titles from widows and orphans.68 The mercurial John Wentworth opined in his Chicago Democrat (by now usually pro-Republican), “… notwithstanding the illness of the Governor, he has waked up sufficiently to give the celebrated Colonel a most unmerciful scoring.”69

On March 14, the Chicago Tribune reported that Governor Bissell’s medical condition had worsened and he was “thought to be beyond recovery,” and on March 20, it carried the report of his death.70 The Times noted, “On or about the 8th inst. Gov. Bissell exposed himself to an atmospheric change, and was, as a consequence, visited with a severe pneumonia …. already reduced to a feeble state by long and serious bodily indispositions, he rapidly declined.”71 The Tribune reported that “Messrs. Lincoln, Hatch, Dubois, and Herndon had a brief farewell interview with him” on March 17, the day before his passing.72 The Journal reported that Lincoln attended the funeral.73

The Campaign of 1860—Republican Gubernatorial Race

Both scandals resurfaced during the 1860 election cycle. With the constitution limiting governors to a single term, prior to Bissell’s death three candidates had been maneuvering for the Republican gubernatorial nomination. They were all political allies of Lincoln’s: State Senator Norman Judd, State Representative Leonard Swett, and former Congressman Richard Yates. Judd’s longtime Chicago rival John Wentworth tried to link Judd to both financial scandals. Repeatedly, his Chicago Daily Democrat used the phrase “Judd-Matteson” in an attempt to cement a connection.74 Judd’s vote as a state senator in favor of the canal scrip indemnification plan gave Wentworth ammunition. Lacking any evidence that Judd was a participant in either scandal, Wentworth argued that Judd, as “the senior Republican Senator,” had failed to promote laws that might have protected the treasury. “We believe that laws could and should have been adopted to have saved us from the financial evils that disgrace our state.”75

On December 1, 1859, Judd filed suit against Wentworth for libel.76 Finding himself now in need of legal representation, Wentworth wrote Lincoln to ask him to defend him.77 Lincoln declined and encour aged the parties to settle, which they eventually did. But by having repeated for months the charge that Judd was somehow connected to Springfield’s financial scandals, Wentworth may have fatally damaged Judd’s gubernatorial prospects.

Judd, though, tried to use the Macalister-Stebbins scandal to taint one of his opponents, Leonard Swett. Swett and Alonzo Mack represented neighboring districts in the state House. Swett had supported Mack’s maneuvering to be appointed treasurer upon Miller’s resignation.78 As the spring State Republican Convention approached, Judd hoped to undermine Swett by having Treasurer Butler remind David Davis of Swett’s “connection with the Mack business.”79 In different ways, then, the canal financing scandals touched two of the three candidates for the 1860 Republican nomination for governor. It is impossible today to know if these accusations influenced the delegates. On the fourth ballot, delegates chose the third candidate, Richard Yates. He was a safe choice, having no connection to either scandal.

The Campaign of 1860—the General Election

Sectional issues dominated the race for president, but in Illinois the canal scrip fraud reappeared as an issue in state legislative races. Having escaped indictment, former Governor Matteson remained politically active.80 The ex-governor was publicly listed as a subscriber to Democratic campaign events, which did not go unnoticed by Republicans. A steadfast supporter of Stephen Douglas, he participated in Douglas’s Springfield rallies; some of the events started or ended at his mansion. Mrs. Matteson led a parade at one rally.81

The Republican press fueled speculation that Matteson was working out a deal with Douglas and the Democratic legislative candidates. It was alleged that if the Democrats won the legislature, in return for Matteson’s financial support, they would change the law and release him from his obligation to reimburse the state for the fraudulent canal scrip he had redeemed.82 The Tribune’s editor Joseph Medill wrote Lincoln about the charge, “You observe that we have given Matteson a broadside.”83

In September, the Senate Finance Committee reported it had discovered more fraudulent transactions by Matteson.84 Because the canal scrip fraud was familiar to the public, it was an easy topic for Republican candidates to raise on the stump. At joint appearances they would ask their opponents if they were part of the group that had made a deal with Matteson to release him from his commitment to repay the state. Democratic candidates were placed on the defensive and forced to spend time denying that they were part of any such plot.85

On October 16, with the election less than three weeks away and occupied with national affairs, Lincoln managed to write an editorial expanding on the idea that a Democratic legislature would release Matteson from his obligations. He recounted the latest revelations of the Senate Finance Committee in stating that the stolen money had been “applied to establishing banks, and building palaces for nabobs.” He wrote that since the Democratic candidates had refused to answer, the taxpayers needed to decide. “We say to them ‘it is your business.’ By your votes you can hold him to it, or you can release him.’’86 The opinion piece seems never to have been published, but its arguments paralleled the closing arguments of the Illinois State Journal and the Chicago Tribune in the final days before the election.87

On Election Day, Tuesday, November 6, Republicans made major gains. Not only did Lincoln and Yates win, but Republicans captured both the state House and Senate for the first time in Illinois history. Republican legislative candidates outpolled both Lincoln and Yates, suggesting that the voters responded to the canal scrip messaging.88

With Republicans securing control of the legislature, there would be no renegotiating Matteson’s commitment to repay the state. In 1861, as southern states were debating resolutions calling for secession, the Senate Finance Committee submitted its final report. The committee had found that Matteson’s illegal scrip redemptions dated back to 1854, while he was in office. It also found that he had written the name of a fabricated payee on unissued scrip he had redeemed, thus adding forgery to his list of crimes.89 In order to collect repayment, the state sued him, winning a verdict in a jury trial.90 Matteson’s property, including his Springfield mansion, was confiscated and auctioned off at the Sangamon County courthouse. His son-in-law purchased the mansion, so Matteson and his family continued to live there.91

Regarding the Macalister-Stebbins bonds, the committee reaffirmed that these had been unlawfully exchanged but that the new bonds were “shortly after surrendered by the parties and the old bonds received again by them.” One hundred twenty-two bonds remained outstanding.92 In 1862, the president of a New York bank that held some of the bonds met with President Lincoln in Washington. Lincoln wrote to Dubois, who was still Auditor, suggesting the bondholders be given a “fair hearing.”93 The hearing was a long time in coming, but in 1865 the legislature settled the issue by once again passing a bill allowing for the bonds to be redeemed at their purchase price (not on their $1,000 face value), with interest, by that July. Any bonds outstanding after that time would be refuted.94 In the spring of 1865 the remaining bonds were cashed in and the matter finally resolved.95

Appointments

One of Lincoln’s duties on assuming the presidency was filling a vast array of administrative and military positions by appointment. To strengthen the political coalition against the Confederacy, Lincoln adopted a policy of appointing some northern Democrats to these posts. While he viewed this as a necessary part of the war effort, the appointments raised the concern of Republicans who viewed their former political opponents’ commitment to the Union cause with skepticism.

These dynamics played out in Springfield when Lincoln appointed two of former Governor Matteson’s allies. The first was Lincoln’s brother-in-law Ninian W. Edwards, appointed a captain in the Quartermaster Department. A former Whig, Edwards had become a Democrat and an associate of Matteson’s.96 Lincoln received a barrage of complaints from Springfield Republicans and from Nicolay, who wrote while on a visit home. They reminded Lincoln that they had “been ferriting [sic] out, and exposing, the most stupendous and unprecedented frauds ever perpetrated in this country, by men closely connected with Mr. Edwards” and that his position allowed him to award contracts to the “Matteson Clique.” Eventually Lincoln relented and transferred Edwards to a lesser post.97

The second problematic appointment was that of Isaac B. Curran, a jeweler who may have engraved Mrs. Lincoln’s wedding ring. He had served as an informal chief of staff to Governor Matteson and had testified as a character witness on his behalf during the Senate investigation of the canal scrip fraud.98 In April 1862, Lincoln nominated Curran as consul for the Grand Duchy of Baden. This nomination was presented to the Senate but rejected when it was extracted from a list slated for approval and tabled.99 Though the reason for the rejection is unknown, it is likely that Browning, who by then had been appointed to the U.S. Senate seat left by Stephen Douglas’s death, was responsible.100

A final legacy of the scandals were reforms instituted in the state’s next constitution, the Constitution of 1870. The proceedings of the constitutional convention show that even though the scandals had occurred more than a decade earlier, they were factors in the delegates’ deliberations.101 When the convention completed its work, it recommended a new constitution that reinstated the position of attorney general, made grand juries optional, and included a special section on canals that was to be voted on separately. The canal section read, “The general assembly shall never loan the credit of the state, or make appropriations from the treasury thereof, in aid of railroads or canals.”102 Both the new constitution and the special section on canals were overwhelmingly adopted by Illinois voters in July 1870.

Analysis

The combined reports of the Senate Finance Committee leave little room for interpretation regarding the canal scrip fraud: Matteson had been brazenly defrauding the state for years, cashing in scrip he had obtained when he assumed the governorship. His excuse that he had purchased it from others whom he could not remember is simply untenable considering that he was a former canal contractor, Senate Finance Committee member, and expert on state debt. It is impossible to know today what portion of Matteson’s wealth was obtained in this manner and consequently the degree to which it enabled his political power. Though Matteson stole from all the citizens of Illinois, it seems that Lincoln was a particular victim of his crimes. Matteson’s financial largesse made him a near winner in the 1855 U.S. Senate election, forcing Lincoln to give up his own campaign and throw his support to Lyman Trumbull. Matteson then used his wealth to support Douglas in both his Senate and presidential campaigns against Lincoln. As the extent of Matteson’s offenses was revealed piecemeal by the Senate Finance Committee’s ongoing work, Republicans were able to use the scandal successfully in the 1860 legislative races, insuring Lyman Trumbull’s reelection to the U.S. Senate. Thus, Democratic legislative candidates also became belated victims of Matteson’s crime.

The investigation into the canal scrip fraud led to the discovery of the Macalister-Stebbins bond scandal. Lincoln and his colleagues crafted a narrative that Bissell, weakened by illness, had been taken advantage of by unscrupulous investors. Democrats argued that Bis-sell, having previously acted as attorney for the bondholders, was an expert on the bonds and that he had been crafting a swindle dating back to his refusal to redeem them in 1857. Because the exchanged bonds had not yet been cashed in, it was possible to have them repudiated and returned to the state. With no financial loss, the scandal then centered on the intent of the governor. Because Matteson had escaped prosecution for his crimes, it seemed a double standard for Democrats to pursue Bissell when his apparent plot had been thwarted. The resignation of State Treasurer Miller and the death of Bissell brought closure to the story, so Democrats could not use it against Republicans in the 1860 general elections.

A few months after his death, Bissell’s personal items were appraised by the Lincoln-Herndon law firm. The 16-page inventory of his estate survives and includes an auctioneer’s statement and a list of real estate holdings and other accounts, compiled by Herndon. The inventory includes property owned jointly with Narcisse Pensoneau, the agent with whom Bissell had corresponded regarding the Macalister-Stebbins bonds.103

Among his few papers surviving today is a contract executed with banker Charles Macalister in December 1856, just days before he became governor. This shows Macalister and 23 other investors sent Bissell $80,500 to be invested in government land purchases. There is an accompanying document showing that Bissell divested himself of this investment in 1857, so that it did not appear in Herndon’s post-mortem appraisal.104

Together these documents demonstrate that Bissell had extensive land holdings and was engaged in land speculation as he became governor. Though probably not illegal, his actions are at least reflective of an active and shrewd businessman, and not of someone mentally impaired. Bissell’s eventual assertive response to Morrison’s convention attack implies that he was mentally capable just two months before his death. Taken in toto, this evidence supports the Democrats’ claim that Bissell’s decision to fully fund the Macalister-Stebbins bonds was not a mistake or misunderstanding of an infirmed mind, but rather an intentional plan.

Missing Pieces

Due to the fragmentary nature of the primary sources, the record of the scandals remains incomplete. Governor Matteson’s mansion at 4th and Jackson Sts., Springfield, burned to the ground in 1873, and little of his personal correspondence remains. Some archives and many newspaper collections were lost in the Chicago Fire. Certain letters are clearly missing because they are referenced in correspondence but have never been found.105 At least one relevant leaf from Browning’s diary is missing.106 With Lincoln and Herndon handling Bissell’s estate, they may have been privy to information or documents which no longer exist and never became public.

Alonzo Mack’s involvement in the Macalister-Stebbins affair has been overlooked due to errors confounding his name with that of others. In a letter Lincoln wrote earlier on another subject in which he referenced Mack, someone wrote over Mack’s name, possibly in a deliberate attempt to obscure his identity. Due to this overwriting, “Mack” was misread by the editors of the Collected Works as “Mechem.”107 And in the modern publication of Nicolay’s source interviews, Mack was confused with Charles Macalister.108 Mack’s involvement in the affair is well documented by his own letters, newspaper accounts, letters by others, Browning’s diary, and the Senate Finance Committee’s 1861 report.

John Nicolay and Ward Lamon separately became Lincoln biographers. Both men were witnesses and peripheral characters in the events that transpired. Despite their intimate knowledge of the scandals and the people involved, neither mentioned them in the biographies they published.109 What explains this omission? Perhaps the authors felt the scandals were unimportant in the context of other events, or perhaps Nicolay and Lamon were reluctant to wade into sensitive subjects that involved their own friends and some of Lincoln’s most important allies and their interrelations. Regardless of their reasons, it is unfortunate for us today, because their first-person perspectives could have helped fill in today’s gap in the record.

The record of the twin scandals is incomplete, and some of their features remain a mystery. The scandals have been ignored by Lincoln scholars due to their complex nature and sometimes confusing primary sources, but they were an important fixture during Lincoln’s rise to prominence, involving many of his contemporaries and shaping the political environment in which he operated.

Notes

- “Counterfeit Canal Scrip—A Fraud upon the State Discovered,” Illinois State Journal, February 2, 1859, 2nd edition. A similar article appeared in the Chicago Press and Tribune on February 3, “Curious Development—Issue of Bonds on Fraudulent Indebtedness.” The author wishes to thank Colin Rensch for assistance with the review of newspaper collections; and his wife Sandy for accompanying him on all his research expeditions. ⮭

- John H. Krenkel, Illinois Internal Improvements 1818–1848 (Cedar Rapids: The Torch Press, 1958), 100. ⮭

- Jesse Dubois (doo-BOYCE) and his second wife, Adelia, were friends and neighbors of the Lincolns. Dubois and Lincoln had served together in the state House. The Duboises named one of their sons ‘Lincoln.’ See Bonnie E. Paull and Richard E. Hart, Lincoln’s Springfield Neighborhood (Charleston, SC: History Press, 2015), and “The Politicians: Jesse K. Dubois (1811–1876),” Mr. Lincoln & Friends, The Lehrman Institute, accessed April 25, 2020, http://www.mrlincolnandfriends.org/the-politicians/jesse-dubois/. (Lehrman Institute noted as loc. cit. hereafter.) ⮭

- Journal of the Senate of the Twenty-First General Assembly of the State of Illinois (Spring-field: Bailhache & Baker, 1859). ⮭

- Logan and Lincoln’s relationship is summarized in “The Lawyers: Stephen Trigg Logan,” Mr. Lincoln & Friends, The Lehrman Institute, accessed April 26, 2020, loc. cit. ⮭

- During the campaign, Lincoln had mistakenly written an acquaintance, Roswell E. Goodell, and revealed his campaign strategy, not realizing that Goodell had become Matteson’s son-in-law and that Matteson was secretly seeking the same seat. Tom George, “Overlooked Letter to Lincoln Reveals Misstep in 1855 Senate Race,” For the People: A Newsletter of the Abraham Lincoln Association 17:1 (Winter 2015), 6–8. Later, the Matteson campaign was rumored to have paid some legislators for their votes, but the speculation was never proven. A complete account of the allegations of impropriety during the campaign and their sources is given in Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life, 2 vols. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008) v. 1, chap. 10. ⮭

- “The Great Fraud at Springfield,” Chicago Press and Tribune, Feb. 8, 1859, 2. This first session was likely an organizational meeting of the committee that occurred before any sworn testimony was taken. Though the Tribune failed to date that meeting, such a meeting of the Senate Finance Committee was reported to have taken place on Tuesday evening, February 1, by the Illinois State Journal “to consider and investigate the matter of the counterfeit checks.” Illinois State Journal, Feb. 3, 1859, 2. ⮭

- John Todd Stuart was Mrs. Lincoln’s first cousin and Lincoln’s former legislative colleague and first law partner. When the Whig Party dissolved and the Illinois Republican Party formed, Stuart became a Democrat. A good summary of Lincoln and Stuart’s relationship is found in “The Lawyers: John Todd Stuart (1807–1885),” Mr. Lincoln & Friends, The Lehrman Institute, accessed April 25, 2020, loc. cit. ⮭

- Benjamin S. Edwards was a son of former Illinois Governor Ninian Edwards (1775–1833) and the younger brother of Ninian W. Edwards, who was Lincoln’s brother-in-law. B.S. Edwards and his brother Ninian W. were both former Whigs who supported Stephen Douglas in his Senate campaign against Lincoln. That Monday, Benjamin Edwards had joined Lincoln and a third attorney, Milton Hay, in examining an aspirant attorney, Henry I. Atkins. The trio found Atkins “qualified to practice law and recommend that he be licensed.” See “Certificate of Examination for Henry I. Atkins,” January 31, 1859, in Roy P. Basler, ed., Marion Delores Pratt and Lloyd A. Dunlap, asst. eds., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 9 vols. (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, for the ALA, 1953–55), 3:352. Hereafter cited as CW. Other sources such as the Feb. 4 entry in the diary of Orville Hickman Browning, who served as one the three state’s attorneys during the investigation, and the Tribune both list Chicago attorney David Stuart as a third attorney for Matteson present at the first hearing. See Theodore C. Pease and James G. Randall, eds., The Diary of Orville Hickman Browning, V. 1: 1850–1864 (Springfield: Illinois State Historical Library, 1925), and the Chicago Press and Tribune, Feb. 8, 1859. ⮭

- Lincoln had been retained by Matteson in matters involving the Chicago and Alton Railroad and the Marine and Fire Insurance Company. Lincoln to Matteson, Nov. 25, 1858, CW, 3:342. ⮭

- Henry Clay Whitney, Life on the Circuit with Lincoln (Boston: Estes and Lauriat, 1892), 136. A short biography of Whitney which includes modern criticism of his work is found in “The Lawyers: Henry Clay Whitney (1831–1905),” Mr. Lincoln & Friends, The Lehrman Institute, accessed April 29, 2020, loc. cit. ⮭

- “Fraudulent Canal Scrip, Report of Evidence before the Senate Committee on Finance, Feb. 4–15, 1859,” Reports Made to the General Assembly of Illinois at its Twenty-first Session Convened January 3, 1859, Vol. I (Springfield: Bailhache & Baker, 1859), 655–819. After approval by the committee, Hitt’s transcription was serialized and published in the Illinois State Journal beginning April 21 and concluding May 16, 1859. The April 21 issue included a sworn affidavit from Hitt attesting to the transcription’s accuracy. Hitt was paid $5.00 per day, which was more than the legislative salary of $2.00 per day. “Auditor’s Report,” Reports Made to the General Assembly of Illinois, at its Twenty-second Session, January 7, 1861, Vol. 1 (Springfield: Bailhache & Baker, 1861), 95. ⮭

- “Fraudulent Canal Scrip, Report of Evidence.” Browning calculated that nearly a quarter of a million dollars had been paid out in this fashion. This would amount to more than $8 million in 2021 dollars. Browning Diary, 350. ⮭

- “Fraudulent Canal Scrip, Report of Evidence.” ⮭

- Journal of the Senate of the Twenty-First General Assembly, 210. The letter was read into the record on February 4 by Senator Kuykendall and referred to the Committee on Finance. See also “Fraudulent Canal Scrip, Report of Evidence,” 818. The letter is reprinted in its entirety with Hitt’s transcription as it was included in the committee testimony taken at the February 15 hearing. ⮭

- “An Act to indemnify the State of Illinois against loss or liability by reason of unlawful funding of canal indebtedness,” Laws of the State of Illinois, Passed by the Twenty-First General Assembly Convened January 3, 1859 (Springfield: Bailhache & Baker, 1859), 190. ⮭

- Browning wrote in his diary, “The opinion of all men of both parties, so far as I can learn it, is that he is guilty—that his guilt is conclusively proven, and that the case is not susceptible to further elucidation.” Browning Diary, 354. ⮭

- Lincoln’s presence at the meeting is documented in Norman Judd to Lincoln, March 24, 1859, Abraham Lincoln Papers, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., and in Lincoln to Gustave Koerner, April 11, 1859, CW, 3: 376. ⮭

- The Great Canal Scrip Fraud. Minutes of Proceedings, and Report of Evidence in the Investigation of the Case, By the Grand Jury of Sangamon County, ILL., at the April Term of the Court of Said County, 1859. Ordered to be Published by a Vote of the Grand Jury (Springfield: Daily Journal Steam Press, 1859), 4. ⮭

- A good summary of the relationship between Butler and Lincoln is given in “The Boys: William Butler (1797–1876),” Mr. Lincoln & Friends, The Lehrman Institute, accessed April 25, 2020, loc. cit. ⮭

- Former Governor Matteson had remained in Springfield, moving into a huge mansion he had begun building during his last year in office. It rested on a three-acre estate he acquired across 4th Street from the governor’s residence. His new home dwarfed the governor’s residence, having three stories and fourteen bedrooms. James T. Hickey ed., “An Illinois First Family: The Reminiscences of Clara Matteson Doolittle,” The Collected Writings of James T. Hickey from the Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, 1965–1984 (Springfield: Illinois State Historical Society, 1990), 103–14. ⮭

- “The Next Sangamon Grand Jury,” The Chicago Daily Democrat, July 13, 1859. ⮭

- The Great Canal Scrip Fraud, Minutes of Proceedings. ⮭

- Ibid. ⮭

- The State Journal noted, “As the case now stands, it is without parallel in the judicial history of the country.” “The Fraud on the Treasury,” Illinois State Journal, May 17, 1859. ⮭

- “The State Treasury,” Chicago Daily Times, July 8, 1859. The potential loss to the state was later calculated to be near $200,000, equivalent to more than $6 million in 2020. See Alexander Davidson and Bernard Stuve, A Complete History of Illinois from 1673 to 1884 (Springfield: H. W. Rokker, 1884), 676. ⮭

- The bonds have variously been referred to as Macalister-Stebbins, Macallister-Stebbins, McAllister-Stebbins, McCallister-Stebbins, Stebbins-Macalister, etc. I have used the most common spelling and the one used in the state ledger found in the Illinois State Archives. ⮭

- The state was able to sell $912,215.44 worth of bonds but collected only $261,460. See Reports Made to the Senate and House of Representatives of the State of Illinois at Their Session Begun and Held at Springfield, December 5, 1842 (Springfield: William Walters, Public Printer, 1842). The relevant reports include “The Message of the Governor of the State of Illinois, Transmitted Dec. 7, 1842,” “The Senate Report of the Joint Select Committee,” February 25, 1843, and “Communication from the Fund Commissioner,” February 25, 1843, which detail the history of the bonds. The fund commissioner who sold the bonds for the state was John D. Whiteside. The bonds were sold in June 1841 in order to make interest payments owed by the state in July. Interestingly, Whiteside, a Democratic appointee, had served as James Shields’s second in the duel imbroglio between Lincoln and Shields in 1842. ⮭

- For an account of the Macalister-Stebbins affair, including Bissell’s early work on behalf of the bondholders, see A Complete History of Illinois from 1673 to 1884, pp. 673–78. The 1849 law was “An act to prevent loss to the state upon the Macalister and Stebbins bonds,” Laws of the State of Illinois, Passed at the First Session by the Sixteenth General Assembly, Begun and Held at the City of Springfield, January 1, 1849 (Springfield: Charles H. Lanphier, 1849), 43. ⮭

- “An Act to fund the arrears of Interest accrued and unpaid on the public debt of the state of Illinois,” Laws of the State of Illinois, Passed by the Twentieth General Assembly Convened January 5, 1857 (Springfield: Lanphier & Walker, 1857). The legislature also passed a resolution specifically excluding the remaining Macalister-Stebbins bonds from this consideration; see Senate message of concurrence of House resolution, Feb. 18, 1857, Journal of the House of Representatives for the Twentieth General Assembly, 1011. ⮭

- The governor was represented by Stephen T. Logan. People ex rel. Billings vs. Bis-sell, Martha L. Benner and Cullom Davis et al., eds., The Law Practice of Abraham Lincoln: Complete Documentary Edition, 2d edition (Springfield: Illinois Historic Preservation Agency, 2009), http://www.lawpracticeofabrahamlincoln.org, hereafter cited as LPAL. ⮭

- The 1847 ledger for the Refunding of State Debt contains an entry dated February 4, 1859, showing the redemption of Macalister-Stebbins bonds held by the Mechanics Banking Association. The ledger is found in the Illinois State Archives. Later the investigating committee would report the date as February 7, and the Chicago Daily Times as February 5. The February 7 date is unlikely as that was a Sunday. The discrepancies probably represent differences in deciphering the ledger’s handwritten numeral. ⮭

- Lincoln and Stephen T. Logan to William Bissell, Jesse Dubois, and James Miller, May 28, 1859, CW, 3:381–82. ⮭

- “The McCallister and Stebbins Bonds—A Note From Auditor Dubois,” Illinois State Journal, July 13, 1859, edition 2. This was reprinted in the Chicago Daily Journal, July 15, and the Chicago Daily Times, July 16. ⮭

- “The Old Canal Claims,” Joliet Signal, December 21, 1858. The editorial concluded, “We look to our legislature to protect us from the wholesale peculation and swindle.” ⮭

- “The Funding of the McAllister and Stebbins Bonds,” Chicago Daily Journal, July 14, 1859. There is a preface addressed to the editor, Charles L. Wilson, “Friend Wilson, I write you according to promise in relation to the McAllister & Stebbins bonds recently refunded in New York.” On the same page is found “The Illinois Canal Scrip Frauds,” the final excerpt of the testimony taken on that matter by the grand jury, reprinted from the “Springfield State Journal” (Illinois State Journal). ⮭

- “The McCallister and Stebbins Bonds! (By Telegraph),” Chicago Daily Journal, July 19, 1859. Since Mack’s July 12 letter had been sent from Springfield, he had wasted no time in getting to New York, where he was now engaged in attempting to undo the transaction. The italicized phrase appears as it was printed by the paper. ⮭

- Hatch was a Springfield neighbor of the Lincolns and a long-time political ally. A summary of their relationship can be found in “The Politicians: Ozias M. Hatch (1814–1893),” Mr. Lincoln & Friends, The Lehrman Institute, accessed April 27, 2020, http://www.mrlincolnandfriends.org/the-politicians/ozias-hatch/. ⮭

- Michael Burlingame, ed., An Oral History of Abraham Lincoln: John G. Nicolay’s Interviews and Essays (Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press, 1996), 16–17. ⮭

- The letter was signed by Lincoln, Hatch, and Logan. At the bottom, Hatch indicated in a postscript that Dubois was not at home, implying that he would have signed it as well. Lincoln to James Miller, July 11, 1859, CW, 3:392. ⮭

- The telegram order was also signed by Logan. Lincoln to James Miller, July 11, 1859, CW, First Supplement, 40. Also see “Lincolniana Notes, Library Adds Five Lincoln Manuscripts to Collection,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, 59:2 (Summer, 1966), 172–73. The article states that this and a Lincoln telegram to Asahel Gridley, April 4, 1859, were the first two telegrams Lincoln ever sent. Collected Works, however, contains at least one earlier telegram, Lincoln to George T. Brown, January 19, 1858, CW, 2:432; and one from the Whig convention in Philadelphia in 1848 was discovered by PAL staff a decade ago. ⮭

- The Lincoln Log: A Daily Chronology of the Life of Abraham Lincoln, Papers of Abraham Lincoln, accessed April 22, 2020, http//www.thelincolnlog.org. Hereafter The Lincoln Log. ⮭

- O.H. Browning, who had been hired to assist Auditor Dubois during the Senate Finance Committee’s investigation of the canal scrip fraud, was also in Chicago on business. He recorded in his diary that he visited the Tremont House, socialized with Mrs. Lincoln and others, and met with Dubois. Browning Diary, 370, and The Lincoln Log. ⮭

- “The ‘Press and Tribune’ Quibbles,” Chicago Daily Times, July 21, 1859. ⮭

- James Miller to Lincoln, Logan, and Hatch, July 14, 1859, Hatch Collection, Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library, Springfield, Ill. ⮭

- Miller also thanked Lincoln for a “suggestion” that had apparently been passed to him in a letter from Dubois. That letter is unknown today. James Miller to Lincoln, July 28, 1859, Abraham Lincoln Papers, LC. ⮭

- “The State Finances, Progress of the Senate Finance Committee,” Chicago Daily Times, August 12, 1859. The report was in the form of a letter, dated August 10, from Committee Chairman Sam W. Fuller. ⮭

- The Chicago Times announced, “These bonds HAVE NOT BEEN SURRENDERED!!” in “Republican Falsehoods—The Macalister and Stebbins Bonds—Important to the People of Illinois,” Chicago Daily Times, August 10, 1859. ⮭

- The Chicago Daily Journal suggested that “a full development might hit some Democrats, high in the affection of the Democracy, who flushed with former success in that line, endeavored to entrap Governor Bissell” in “The State Frauds,” Chicago Daily Journal, August 10, 1859; reprinted in the Illinois State Journal, August 15, 1859. ⮭

- Lincoln left Springfield on August 9 and returned on August 18. The Lincoln Log. ⮭

- James Miller to Lincoln, August 20, 1859, Abraham Lincoln Papers, LC. ⮭

- Lamon and Swett were attorney friends and allies of Lincoln who had assisted in his Senate campaigns. At the time, Swett was also a member of the state House. See short biographies at “The Lawyers: Ward Hill Lamon (1828–1893),” and “The Lawyers: Leonard Swett (1825–1899),” Mr. Lincoln and Friends, The Lehrman Institute, loc. cit. ⮭

- Ward Lamon to Lincoln, August 20, 1859, Abraham Lincoln Papers, LC. ⮭

- The standard biography is Willard L. King, Lincoln’s Manager, David Davis (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1960); see also “The Lawyers: David Davis (1815–1886),” Mr. Lincoln and Friends, The Lehrman Institute, loc. cit. ⮭

- Browning Diary, 374. ⮭

- Browning Diary, 375. ⮭

- David Davis to Lincoln, August 27, 1859, Abraham Lincoln Papers, LC, where the transcription reads, “Dear Lincoln. You need not hunt up the question of — limitation —— It The (?creaters) have filed their claims just a few days too early for me—Let it slide” I believe the ambiguous word parenthesized by the transcriber is more likely “cheaters” than “creaters” (sic). The “Baker” whom Davis mentions in his postscript is Samuel L. Baker, a Republican State Representative from Chicago. A photostat of the letter is found in the David Davis Collection of the Chicago History Museum. In its margin, Davis biographer Willard L. King has written, “What is this about?” ⮭

- The Constitution of Illinois (1848), Article III “Of the Legislative Department,” §7. Lincoln had personal experience with this provision which also included a prohibition against being elected to the U.S. Senate from the legislature. In 1854, after being elected to the legislature, he resigned his seat in order to be eligible to run for the Senate. Browning mentioned the constitutional prohibition in his diary, Browning Diary, 374. ⮭

- James Miller to William Bissell, August 27, 1859, Illinois State Archives. ⮭

- “The State Treasury,” Chicago Daily Times, Sept. 2, 1859. ⮭

- “The State Treasury, Statements of Col. Miller, the Auditor and the State Treasurer,” Chicago Daily Journal, September 12, 1859, and “The State Treasury, Statements from the Auditor and the Official Receipt of Mr. Butler to Col. Miller—The State Funds all Safe,” Illinois State Journal, August 12, 1859. ⮭

- The convention was held in Springfield on Wednesday, January 4, 1860, for the purpose of selecting delegates to the national convention to be held in April in Charleston, South Carolina. Statewide candidates would be chosen at a later convention. See “Convention To-Day,” Chicago Press and Tribune, Jan. 4, 1860, and “The Douglas State Convention,” Chicago Press and Tribune, Jan. 6, 1860. ⮭

- Colonel James D. M. Morrison is not to be confused with William Rails Morrison, Democratic State Representative from Monroe County and Speaker of the House in 1859. A short biography of James D. Morrison can be found in Newton Bateman and Paul Selby, eds., Historic Encyclopedia of Illinois, Vol. 1 (Chicago: Munsell Publishing Company, 1907), 386. ⮭

- “Official Corruption—Crushing Speech Against Governor Bissell,” Chicago Daily Times, Jan. 11, 1860. The impeachment reference is found in “Bissell and Morrison,” Joliet Signal, Jan. 24, 1860. The trip to New York is in “Gov. Bissell in a Rage,” Chicago Daily Times, Jan. 13, 1860. ⮭

- “The Macalister Bonds,” Chicago Daily Times, Jan. 11, 1860. ⮭

- “Gov. Bissell in a Rage,” Chicago Daily Times, Jan. 13, 1860. ⮭

- “A Letter from Governor Bissell,” Illinois State Journal, Jan. 9, 1860. Based on Bis-sell’s response, it seems that the letters Morrison presented at the convention between Bissell and the bondholders’ intermediary, Narcisse Pensoneau, were likely genuine. The Times had printed the full text of the letters with its report of Morrison’s convention speech. The letter that Bissell claimed would exonerate him is non-extant today. If he had retained a copy, the Republican press never published it. ⮭

- Ibid. ⮭

- “Letter from Gov. Bissell,” Illinois State Journal, Jan. 12, 1860, reprinted from the Chicago Daily Democrat. ⮭

- “Gov. Bissell,” Chicago Press and Tribune, March 14 and March 17, 1860; “Death of Governor Bissell,” ibid., March 20, 1860. ⮭

- “Death of William H. Bissell, Governor of Illinois. Official Announcement” and “Death of Gov. Bissell,” Chicago Daily Times, March 20, 1860. ⮭

- “‘The Last of Earth.’ The Death of Hon. Wm. H. Bissell. The Obsequies at Spring-field,” Chicago Press and Tribune, March 23, 1860. ⮭

- Chicago Daily Journal, March 22, 1860. ⮭

- See for example, “Another Great State Fraud,” Chicago Daily Democrat, July 11, 1859. ⮭

- “A Political Libel Suit,” Chicago Daily Democrat, Dec. 2, 1859, David Davis Collection, Chicago History Museum. The clipping is undated but the article begins, “Yesterday the sheriff called upon us with a summons to answer unto Senator Judd for a libel.” This indicates it was published Dec. 2, 1859, the day after the suit was filed. ⮭

- Judd to Trumbull, Dec. 1, 1859, David Davis Collection, Chicago History Museum. ⮭

- Wentworth to Lincoln, Dec. 21, 1859, Abraham Lincoln Papers, LC. ⮭

- Lamon to Lincoln, Aug. 20, 1859, Abraham Lincoln Papers, LC. ⮭

- Judd outlined his plan in a letter sent to Secretary of State Hatch a month before the convention. He suggested “Butler ought to be able by proper representations to Davis to blow up that Bloomington meeting so far as Sweat [sic] is concerned.” He continued, “That Treasurer business ought to be used against the whole gang—and if Sweats’ [sic] attempts to bolster up those adventurers, was properly laid before Davis he would blow up the whole concern.” He closed the letter, “Kindly ponder, and burn this as it is rather free. Yr friend, Judd” Judd to Ozias Hatch, March 29, 1860, David Davis Collection, Chicago History Museum. ⮭

- In January 1860 he had embarked on a tour to promote Douglas’s campaign in Florida and Louisiana. ⮭

- “The Douglas Wigwam,” “The Great Douglas Rally,” and “Douglas Rally,” Illinois State Journal, July 24, 26, and Aug. 20, 1860. The last article accuses Matteson of providing an “indefinite number of kegs of lager beer” to the “Douglasites” at the “Canal Scrip Synagogue.” ⮭

- The Chicago Press and Tribune and the Illinois State Journal initiated this attack on July 28 in “A Scheme to Defraud the State,” Chicago Press and Tribune, July 28; “An Act for the Relief of Joel A. Matteson,” Chicago Press and Tribune, August 30, 1860; and “The Douglas–Matteson League,” Illinois State Journal, July 28, 1860. ⮭

- Joseph Medill to Lincoln, July 29, 1860, Abraham Lincoln Papers, LC. ⮭

- Records showed that in April of 1857, Matteson had redeemed unissued scrip for new bonds that had subsequently been deposited in trust for the State Bank of Illinois, a bank he himself owned. The committee found another set of scrip that the state had issued to contractors and then redeemed with state land. Some of this scrip was found to have been redeemed a second time from the State Land Fund for new bonds. In order to pay interest due on the new bonds, the state had issued more bonds, adding to the theft. All of this could be traced to scrip that had been in Matteson’s possession. “Another Robbery of the State Discovered” and “More Frauds, A Further Discovery by the Senate Committee,” Chicago Press and Tribune, Sept. 18 & Sept. 22, 1860. “Further Frauds Upon the State Discovered,” Illinois State Journal, Sept. 20, 1860. During this period, Browning noted in his diary on three days that he was reviewing related treasury records on behalf of the state. He wrote that he met with Lincoln on one of those days, Sept. 10; see Sept. 10, 19, and 20, 1860, Browning Diary, 426–28. ⮭

- Illinois State Journal, Oct. 1, 3, 8, 9, 12, 22, and 23, 1860. ⮭

- The Canal-Scrip Fraud, Oct. 16, 1860, CW, 4:128. ⮭

- “Will You Sustain the Plunderers,” Illinois State Journal, Nov. 1, 1860, and “Questions,” Chicago Press and Tribune, Nov. 6, 1860. ⮭

- The November 6 returns show 173,877 votes cast for Republican state House candidates (counting only the top vote-getter in districts electing more than one representative) while Lincoln collected 172,171 votes. Hence the Republican candidates for the state House outperformed Lincoln. In contrast, Douglas netted 160,215 votes, while Democratic candidates for the state House received only 151,045 votes (again counting the top vote-getter in districts electing more than one representative). Hence, Democratic state House candidates underperformed Douglas. This disparity is best explained by the influence of state issues, such as the canal scrip fraud. A good example of this dynamic played out in the Sangamon district where Douglas barely beat Lincoln 3,598 to 3,556, but Republican state House candidate Shelby Cullom out-polled each of them with 3,708 votes. Record of Election Returns, microfilm reel #30–45, Illinois State Archives. ⮭

- The additional losses to the state were calculated at $165,346. The initial losses had been determined to be $223,182, so the total losses from the canal scrip fraud amounted to $388,528, or more than $12.5 million in 2021 dollars. “Report of the Senate Finance Committee,” Reports Made to the General Assembly of Illinois, at its Twenty-Second Session, 397–432. ⮭

- “The Canal Scrip Fraud” and “Matteson Fraud Case,” Chicago Press and Tribune, Jan. 27 and Oct. 29, 1862, and “State of Illinois vs. Joel A. Matteson,” Illinois State Journal, Oct. 29, 1862. ⮭

- “In Chancery,” Illinois State Journal, Apr. 4–27. This public notice ran during the three weeks preceding the sale. See also “Sale of the Matteson Property,” Illinois State Journal, Apr. 28, 1863, “A Remarkable Case of Justice,” Illinois State Journal, May 5, 1863, “The News,” Chicago Press and Tribune, Apr. 29, 1863, “From Springfield,” Chicago Press and Tribune, Nov. 14, 1863, “The Matteson Property,” Illinois State Journal, Dec. 7, 1863, “The City,” Illinois State Journal, July 11, 1864, and “Personal,” Illinois State Journal, July 19, 1864. ⮭

- This finding finally validated Mack’s July 19, 1859, telegram stating the bonds had been returned. Recall that the Macalister-Stebbins bonds carried a face value of $1,000 each but were purchased for an average of only $286. The report showed that 114 of these were exchanged in New York for new $1,000 bonds. The new $1,000 bonds had subsequently been returned for the original Macalister-Stebbins bonds. “Report of the Senate Finance Committee,” Reports Made to the General Assembly of Illinois, at its Twenty-Second Session, 420 (p. 28 of committee report). ⮭

- Lincoln to Dubois, Dec. 10, 1862, CW, 5:548. The editors of the Collected Works were unable to identify “Mr. Freeman,” but a contemporary directory of New York bankers shows Melancthon Freeman was President of the New York Mechanics Banking Association: The Bankers’ Magazine and Statistical Register, 17, 1862/63 (New York: J. Smith Homans, Jr., 1862/63), 403. Browning noted that he met with a “Mr. Freeman, the president of a bank in New York,” Browning Diary, 452; and correspondence J.D. Morrison published in his attack on Bissell included letters between N. Pensoneau and Melancthon Freeman (“Official Corruption,” Chicago Daily Times, Jan. 11, 1860). ⮭

- Journal of the Senate of the Twenty-Fourth General Assembly of the State of Illinois, At Their Regular Session, Begun and Held at Springfield, January 2, 1865 (Springfield: Baker and Phillips, 1865), 953. On Feb. 16, Governor Richard Oglesby signed “An Act to compel the holders of the Macalister-Stebbins bonds to surrender the same by July, 1, 1865.” ⮭

- “Biennial Report of the Auditor of Public Accounts of the State of Illinois,” Reports to the General Assembly of Illinois, at its twenty-fifth session, convened January 7, 1867, 1 (Springfield: Baker, Bailhache & Co., 1867), 68. The Auditor’s report for 1867 shows the bonds purchased for $286 in 1841 paid about $475 in 1865 for a compound annual growth rate of just over 2%. ⮭

- Ninian’s younger brother Benjamin S. Edwards served as one of Matteson’s attorneys throughout the canal scrip ordeal. A good overview of Lincoln’s complicated relationship with Ninian is given in “The Politicians: Ninian W. Edwards, (1809–1889),” Mr. Lincoln and Friends, The Lehrman Institute, loc. cit. ⮭

- Ozias Hatch, William Butler, and Jesse Dubois to Lincoln, July 22, 1861; Nicolay to Lincoln, Oct. 21, 1861; William Thomas to Lincoln, Sept. 28, 1861; Dubois, Butler, and Hatch to Lincoln, Oct. 21, 1861; William Yates to Lincoln, May 22, 1863; Dubois and others to Lincoln, May 23, 1863; S. Cullom to Lincoln, May 25, 1863; G. Webber to Lincoln, May 25, 1863; and Jacob Bunn to Lincoln, May 25, 1863. Abraham Lincoln Papers, LC. ⮭

- For the wedding ring, see Bryon C. Andreasen, “Curran’s Jewelry Shop,” Looking for Lincoln: Lincoln’s Springfield (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2015), 16. Curran’s connection to Matteson and Douglas is discussed in Nathaniel B. Curran, “General Isaac B. Curran: Gregarious Jeweler,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 71:4 (Nov. 1978): 272–78. Curran’s testimony in the canal scrip investigation is found in “Fraudulent Canal Scrip, Report of Evidence.” ⮭

- Lincoln’s nomination of Curran was read into the U.S. Senate record on April 24 and referred to the Committee on Commerce. On May 2, the Committee on Commerce reported the nomination and on the same day the Senate, on a motion of Senator Lot M. Morrill (R-Maine), recommitted the nomination back to the Committee on Commerce. On July 12, 1862, the measure was tabled by Senator Fessenden (R-Maine) and never brought up again. Journal of the Executive Proceedings of the Senate of the United States of America from December 2, 1861 to July 17, 1862, Inclusive, Volume XII (Washington: Government Printing Office. 1887). Unfortunately, the Illinois State Journal incorrectly reported that Curran’s appointment had been confirmed (untitled notice, July 22, 1862, p. 2). This error was repeated in the brief biography of Curran by his grandson, N. B. Curran, “General Isaac B. Curran,” 277, and is implied in the Curran’s Jewelry Shop historical marker on Adams Street in Springfield, which simply mentions that he was appointed. The text of the marker can be read at https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=48740. ⮭

- During the canal scrip investigation, he had commented in his diary that Curran’s testimony was untruthful. Browning Diary, 353. ⮭

- Debates and Proceedings of the Constitutional Convention of the State of Illinois, Convened at the City of Springfield, Tuesday, December 13, 1869, 1, Ely, Burnham and Bartlett Official Stenographers (Springfield: E. L. Merritt & Brother, 1870), 335. Browning; Milton Hay, who had studied law under Lincoln; and Joseph Medill, former editor of the Chicago Tribune, served as delegates to the convention. ⮭

- Article V Executive Department, Article II Bill of Rights, and Special Section on Canals, Illinois Constitution of 1870. ⮭

- Herndon et al. appraised property for Bissell’s estate, LPAL. The entry contains just the 16-page appraisal listing Bissell’s real estate and other accounts and the auctioneer’s statement. Herndon signed the appraisal on May 24, 1860. ⮭

- Bissell to C. Macalister, Feb. 25, 1856; trust deed, Dec. 27, 1856; Bissell to R. Hinckley, May 27, 1857, McAlester & Markee Land Co. (1 folder), Manuscript Collection, ALPL. ⮭

- Two of Norman Judd’s letters written during this period reference the destruction of correspondence. To Lincoln he wrote “that little letter is destroyed as per request.” Judd to Lincoln, June 15, 1859, Abraham Lincoln Papers, LC. In a letter to the Ozias Hatch he closed with the admonition, “… burn this as it is rather free.” Judd to Hatch, Mar. 29, 1860, David Davis Collection, Chicago History Museum. ⮭

- The Feb. 5, 1861, entry that begins discussing the Macalister-Stebbins bond issue ends abruptly with the next leaf missing. Browning Diary, 452. This missing leaf is not one of the sections of the diary withheld from publication due to unflattering references to Mrs. Lincoln. Rather, it is absent from the existing manuscript, and the reasons for its absence are unknown. (Personal communication with ALPLM staff, 4/14/2021). ⮭

- Tom M. George, “‘Mechem’ or ‘Mack’: How a One-Word Correction in the Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln Reveals the Truth About an 1856 Political Event,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association 33:2 (Summer 2012): 20–34. ⮭

- In a footnote, the statement by Ozias Hatch discussing Mack is incorrectly interpreted as referring to Charles Macalister. An Oral History of Abraham Lincoln: John G. Nicolay’s Interviews and Essays, p. 137, fn. 73. ⮭

- John G. Nicolay and John Hay, Abraham Lincoln: A History, 10 vols. (New York: Century Company, 1890). The only use of Hatch’s material is an anecdote about viewing McClellan’s Army, found in Vol. VI, p. 175. Ward H. Lamon, The Life of Abraham Lincoln From His Birth to His Inauguration as President (1872; rpt., Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1999), and Dorothy Lamon Teillard, ed., Ward H. Lamon, Recollections of Abraham Lincoln, 1847–1865 (1895; rpt., Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1994). ⮭