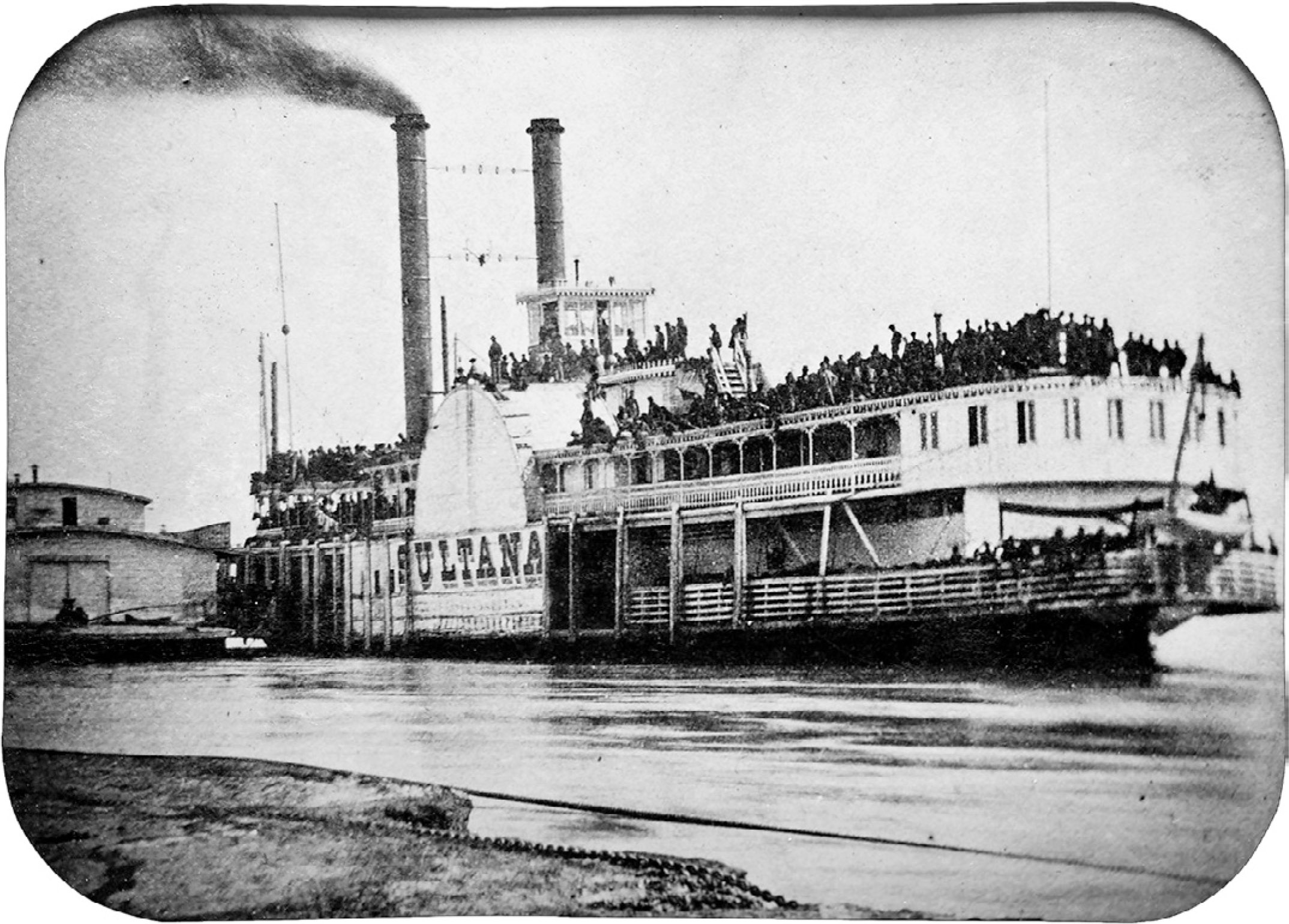

On April 27, 1865, the sidewheel steamboat Sultana, jammed with approximately 2,400 Union veterans, many returning at the Civil War’s end from Confederate prisons, exploded and sank on the Mississippi River near Memphis, killing more than 1,700 persons. The Sultana’s certified capacity was 376 persons, but the Union officers at Vicksburg, including the quartermaster, Colonel Reuben B. Hatch, allowed it to be severely overloaded even though two other transport steamers were available for boarding. Experts dispute whether the overcrowding led the Sultana’s boilers, which had been recently repaired, to overheat and explode, but overcrowding certainly caused the accident’s horrific death toll. Surprisingly, this deadly incident did not dominate national news. Because the Sultana disaster occurred shortly after Lincoln’s assassination and the Confederate army’s surrender—Lincoln’s assassin, John Wilkes Booth, was tracked down and killed the day before the steamboat exploded—it did not receive sustained newspaper attention or public scrutiny.1

After the incident, General Cadwallader Washburn, commanding the military District of West Tennessee, convened a court of inquiry. Colonel Hatch denied playing any role in overloading the Sultana. Despite testimony to the contrary and allegations that a kickback from the steamboat’s owners influenced Hatch and his subordinates, Washburn exonerated Hatch and placed sole responsibility on another local officer, the assistant adjutant-general, Captain Frederic Speed. A separate investigation ordered by Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and led by General William Hoffman called Hatch’s failure to intervene in the overloading a dereliction of duty and named Hatch and Speed “the most censurable” of the officers involved.2 On June 3, 1865, Hatch was relieved of his quartermaster duties. Two weeks later, after reviewing the Washburn Commission report, Quartermaster General Montgomery Meigs recommended that Hatch be court-martialed. Instead, on July 28, 1865, Reuben Hatch was mustered out of the army with an honorable discharge. During Captain Speed’s military trial the next year, Hatch ignored three subpoenas to testify—an indication, according to War Department officials, that he “felt a consciousness of some responsibility for the disaster.”3

Reuben Hatch’s army career thus ended in a cloud of suspicion. As recent histories have shown, that cloud can be traced back to the White House. Although Hatch’s powerful political connections were overlooked at the time, his conduct appears to implicate President Lincoln. It was Lincoln who personally requested Hatch’s initial appointment as assistant quartermaster at Cairo, Illinois, in 1861 as a patronage favor to the president’s Illinois backers. Lincoln, historians allege, also intervened to allow Hatch to emerge unscathed from multiple investigations regarding corruption charges in 1861–62. Lincoln’s subsequent aggressive lobbying to promote Hatch culminated in his assignment as quartermaster at Vicksburg, where he sent the Sultana on its fatal journey. The leading historical accounts of the Sultana disaster, including a popular PBS documentary with supporting commentary from prominent Lincoln scholar Harold Holzer, suggest that Lincoln, through his patronage largesse and careless cronyism, was indirectly responsible for the worst maritime disaster in U.S. history.4

This essay argues that Hatch’s ascent through the army ranks, although clearly smoothed by Lincoln’s support, was made possible by a lax and little-known War Department investigation of 1862, the Cairo Claims Commission. This civilian investigative body, which convened in Cairo in June and July 1862 to examine claims that originated during Hatch’s term as assistant quartermaster, completely exonerated Hatch of charges of corruption and contract fraud. The full history of the Cairo Commission may never be known, since its official report went missing from the War Department records after the war. However, piecing together surviving documents and correspondence allows us to recreate the Commission’s complicated origins, its investigative actions, and its decisive findings—and to highlight the deficiencies of its proceedings.5 President Lincoln’s decision to convene a claims commission was not an attempt to “stop the investigation” of Hatch or prevent a court martial, as avid Sultana researchers have alleged.6 Nevertheless, the Commission’s blanket absolution of Hatch opened the way for endorsements of the ambitious quartermaster by Lincoln (and by General Grant), which led to Hatch’s subsequent promotions. In appointing Hatch, President Lincoln followed traditional patronage practices, and in continuing to advance his army career after the Cairo Commission’s exoneration, Lincoln was acting in good faith. The Commission’s shortcomings bear a much greater share of responsibility than Lincoln for Hatch’s later malfeasance, including his role in the Sultana disaster.

Located at the point where the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers converged, the town of Cairo sat in clusters of ramshackle, seemingly temporary buildings on a boot-shaped marsh protected by levees from the great rivers’ overflow. Perpetually muddy and pungent with the odors of marshland and animal pens, Cairo was described gloomily by Charles Dickens during his American tour in 1842 as “a dismal swamp, … a hotbed of disease, an ugly sepulchre, a grave uncheered by any gleam of promise: a place without one single quality, in earth or air or water, to commend it.” Twenty years later, another visiting British novelist, Anthony Trollope, found Cairo’s streets “absolutely impassable with mud” and donned high boots to negotiate its plank sidewalks. By then, however, the town was no longer desolate. Early in the Civil War, Cairo became the Union’s most important river port in the West, the focal point of Northern plans to split the Confederacy in two. In the summer of 1861 Cairo served as General Grant’s headquarters; when his army headed south in the fall, it was his main communications center and supply depot. From Cairo’s docks Union gunboats were dispatched on expeditions up the Ohio and Tennessee Rivers; from its warehouses Union armies on both sides of the Mississippi—in Kentucky, Tennessee, and Missouri—received their supplies and munitions.7

The town’s sudden prominence as a military supply center severely tested its quartermaster’s office. The logistical problems of outfitting the mushrooming Union army led to improvised, irregular supply procedures; lack of government cash sometimes reduced procurement to promises and bartering; and lucrative war contracts brought enticing new opportunities for corruption. By the fall of 1861 there was growing evidence that quartermaster operations at Cairo were being managed incompetently and probably dishonestly.

The problems dated from the previous summer, when Reuben B. Hatch was appointed Assistant Quartermaster. Hatch was the younger brother of Ozias M. Hatch, a close friend and political ally of Lincoln. In the 1850s the Hatch brothers, Reuben, Ozias, and Isaac, operated a mercantile store in their hometown of Griggsville, Illinois (about 45 miles west of Springfield). Ozias became active in state politics and in 1856 was elected as Secretary of State, serving back-to-back terms. John G. Nicolay, who became Lincoln’s campaign assistant and White House secretary, had been Hatch’s clerk. According to Nicolay, Hatch’s office in the Old State Capitol was the center of Springfield political activity in the years before Lincoln left for Washington. Lincoln often visited there while using the Capitol’s law library or seeking political scuttlebutt. There also Hatch and other prominent state Republicans met early in 1860 to propose putting up Lincoln’s name as the Illinois nominee for president. Hatch headed a circle of Lincoln friends who helped secure his nomination at Chicago and provided incidental expenses for the 1860 presidential campaign. After Lincoln was elected, Hatch, along with State Auditor Jesse K. DuBois and State Treasurer William Butler, frequently advised President Lincoln on appointments and fought pro-Confederate influences in that intensely divided state.8

Reuben Hatch, according to his elder brother, was “foolish enough to desire an office,” and in March 1861, when the Lincoln administration was besieged with place seekers, Ozias Hatch asked Lincoln’s friend and sometime bodyguard Ward Hill Lamon to lobby for Reuben. Nothing came of this, so on April 26, two weeks after the war broke out, Reuben, aged 41, volunteered for the 8th Illinois Infantry and was commissioned as First Lieutenant and Quartermaster. Three months later he was mustered out from his unit, and on August 3, 1861, he was promoted to captain and assigned as assistant quartermaster at Cairo. President Lincoln had personally requested this appointment a week earlier from Secretary of War Simon Cameron.9

Harry J. Carman and Reinhard H. Luthin, the most comprehensive students of Lincoln’s distribution of patronage, contend that on the whole the President wielded his appointment powers judiciously to balance Republican Party factions, to bind War Democrats to the success of his administration, and to preserve the Union during wartime. However, “Lincoln, except in a few cases, made no very searching effort to ascertain whether the persons appointed were those best fitted by talent and experience for the job.” “In other words,” they conclude, Lincoln “followed the time-honored rule of political expediency. To friends—particularly those of long standing—he was inclined to show favoritism.” Pressures for patronage were particularly strong in Illinois, where Lincoln’s colleagues, neighbors, and supporters clamored for offices and never appeared satisfied that the President had done enough to reward them for their support. To appease those friends, Lincoln was glad to help Reuben Hatch, especially since he was unaware that Hatch was incompetent and probably corrupt.10

In July 1861 Congress, increasingly critical of the lax regime of Secretary of War Simon Cameron and aware of allegations of graft and lavish spending against General John C. Frémont, whose Department of the West included Cairo, formed a House Committee to inquire into contracts relating to western war operations. Four members of the Committee, led by Representative Elihu B. Washburne, met at St. Louis from October 15 to October 29, and at Cairo on October 31. Testimony presented at Cairo alleged such irregularities under Captain Hatch as long delays in the settling of accounts, the use of his clerk as a middleman, and the diversion of government horses and mules to Hatch’s own farm. These were noted in the Committee’s partial report of December 17.11

A few days earlier, a reporter for the Chicago Tribune wrote a story claiming that local lumber dealers were being instructed to fill out inflated bills to cover the Cairo quartermaster purchasing agent’s “commission.”12 General Grant, the commander at Cairo, had recently praised Hatch for his logistical assistance at the Battle of Belmont, and he was evidently surprised by these allegations. Grant sent an aide, Captain William S. Hillyer, to Chicago to investigate. Taking Captain Hatch along, Hillyer reported that the quartermaster had not been cooperative, but his inquiries had established that Hatch and his clerk Henry Wilcox had overbilled the government for the lumber and may have split the profits with the lumbermen.13

In January 1862, Grant, concluding that the investigation “fully sustains the charges made by the Tribune,” had Hatch and his chief clerk George Dunton arrested, clerk Wilcox dismissed, and the Quartermaster records seized. Hatch was accused of using illegal purchasing methods, defrauding the government through inflated billing on vouchers, and ignoring the graft of his assistant Wilcox. Grant requested that the U.S. Judge Advocate General’s Office begin preparing court-martial charges against Hatch, but Washington officials apparently lacked the necessary vouchers to specify charges. Grant, meanwhile, had received allegations about “selling clothing and other property by the Quartermaster, hiring boats and giving vouchers for a different price,” and buying grain in bulk to sell in smaller sacks at a profit. To investigate these accusations and determine Hatch’s innocence or guilt, the general suggested that “some suitable person” be delegated by the Quartermaster office in Washington.14

Quartermaster General Montgomery Meigs, after hearing from Grant about Hillyer’s report, and having received other incriminating reports on the Cairo office, told the new war secretary Edwin Stanton that none of his officers could be spared to investigate. Instead, Meigs ordered that all of the debts to contractors incurred at Cairo be submitted to a War Department claims commission that had been sitting in St. Louis since mid-November to examine military contracts, with General Frémont as its primary target. Kentuckian Joseph Holt, a former secretary of war under President Buchanan, Lincoln’s Illinois colleague David Davis, and prominent merchant Hugh Campbell of St. Louis were its members.15 On Grant’s advice, General Henry W. Halleck told Commissioner Davis to investigate, but not to settle, accounts from Cairo, “as every day develops [new] evidence of peculation.”16

Meigs also urged Edwin Stanton to send an attorney to investigate the allegations against Hatch and prepare additional court-martial charges if warranted.17 Stanton had heard reports of corrupt and wasteful operations in the West and was anxious to root out shady practices tolerated by his predecessor Cameron. To assess conditions at Cairo he sent Assistant Secretary Thomas A. Scott to confer with generals and tour the camps. Scott was a former Pennsylvania Railroad vice president and an efficient manager who could penetrate the fog of army contracts. On February 12 Scott reported to Stanton that “the condition of affairs under Q. M. Hatch was about as bad as could well be imagined.” Testimony from contractors had uncovered “a regular system of fraud”: vouchers billing the government for lumber, hay, oats, and ferryboat rentals were inflated over costs, and “the difference, it is supposed, was to belong to the Quarter Master’s Department as perqui-sites.” Scott reported that Hatch, currently under military confinement to Cairo, may have been responsible for further mischief: “A few days after his arrest two of his ledgers were found at the lower point of Cairo, in the water at a point where the Ohio and Mississippi meet. They were washed onshore, the intention evidently being to destroy them.” With Grant’s expedition to Fort Donelson already under way, “the accounts of Capt. Hatch should be pressed to settlement immediately,” Scott declared. He recommended that the Quartermaster’s Department be reorganized and Hatch’s accounts handed over to a competent officer who would reduce all claims to fair prices and settle them.18

The War Department’s St. Louis Claims Commission report, completed on March 10, 1862, echoed Scott’s suspicions. Its members had examined only a fraction of the claims originating under Hatch’s administration but found strong indications that transactions in coal, ice, and lumber were tainted with fraud. Perhaps to cover the trail, Hatch regularly had his clerk sign the vouchers for him, a practice which itself was illegal. The Commissioners recommended that no Cairo vouchers be paid without an investigation: “Were an intelligent and faithful commissioner sent to Cairo, with power and directions to examine the claimants under oath, and such other testimony as might be obtained, the truth would probably generally be arrived at.”19

On March 14, 1862, the House Committee on Contracts, which had been alerted by Stanton, held a new hearing in Chicago which exposed the lumber fraud in seamy detail. On two occasions late in 1861 Hatch sent his assistant Wilcox to Chicago to purchase lumber for barracks at Cairo. Wilcox brought in his brother-in-law, Benjamin W. Thomas, as a middleman. As they visited various lumber dealers, Wilcox waited outside; inside, Thomas purchased lots of lumber for an average of $9.50 per thousand board feet but asked dealers to bill the government for $10.50, representing the difference as his commission. Wilcox and Thomas testified that over half of this “commission”—more than $300—went to Hatch.

Hatch compounded the fraud with a cover-up. When Hatch had accompanied Grant’s investigator Hillyer to Chicago, he shed him to meet secretly with the lumbermen in the same hotel and renegotiate their contracts, an obvious attempt to paper over the November and December deals. Hatch then sequestered Wilcox at the farm of his brother, Sylvanus Hatch, in an unsuccessful attempt to prevent him from testifying before government investigators. Based on the testimony of Wilcox, Thomas, and the lumbermen, the House report concluded that Hatch’s lumber purchases were “fraudulent and corrupt,” and that the Quartermaster had “combined with other parties to defraud the government and put money directly into his own pocket.”20

By the spring of 1862, then, four different preliminary investigations presented allegations and testimony regarding Hatch’s complicity in various fraudulent schemes and other irregularities at Cairo. There were varied opinions on what to do next, but all the military men recommended further investigation prior to any court martial. Stanton’s troubleshooter Scott and the War Department’s St. Louis Commission recommended appointing a special commissioner to settle the Cairo claims. Quartermaster General Meigs agreed that a commissioner or Congress should take the lead, complaining repeatedly that his officers were “too few and too fully occupied with more important matters to be detailed on this investigation.” Grant awaited further findings by the War Department (either an investigator appointed by Meigs or General Halleck’s office, which was examining Hatch’s ditched books) before deciding on a court of inquiry.21

President Lincoln, meanwhile, apparently learned of the accusations against Hatch in mid-January 1862, when he came across a report in the New York Herald that the quartermaster department at Cairo was rife with “the grossest frauds and peculations,” including “coal swindles, horse swindles, mule swindles, and swindles of all kinds” perpetrated by Hatch. The reporter, Frank G. Chapman, claimed to have all the facts. Lincoln’s reaction was not to defend his appointee Hatch or suppress the story, but to have the evidence placed before the proper War Department authorities. The President contacted Chapman and directed him to see Meigs and share his sources.22

Later that month Hatch’s attorney, Jackson Grimshaw, from Hatch’s Pike County and another of Lincoln’s Illinois friends, came to Washington to protest Hatch’s arrest and argue his innocence. His presence was noted by Lincoln’s secretary, Nicolay: “Jack Grimshaw has been here a week or ten days trying to ascertain and straighten out the troubles Reuben Hatch has somehow got himself into over his Quartermaster’s affairs.” Grimshaw carried a letter from U.S. Senator Orville Browning, another Illinois friend of Lincoln, attesting to Hatch’s integrity and asking for a “fair, speedy trial.” On January 31 Grimshaw urged the President in writing to speed the process by ordering a court martial or a court of inquiry himself. The next day, Lincoln asked Judge Advocate General John F. Lee if he as president could order such a court. Lee replied that General Grant was in a better position to know the facts and intended to appoint a military inquest; Lincoln should not interpose to speed things up.23

Nearly a month passed, and the Illinois Republicans resumed their lobbying. On February 24, 1862, Illinois Governor Richard Yates, Ozias Hatch, and Jesse Dubois wrote Lincoln that the charges against the Quartermaster were “frivolous and without the shadow of foundation in fact.” Lincoln again asked the Judge Advocate General for an opinion on the case, declaring: “I also personally know Capt. R. B. Hatch, and never before heard any thing against his character.” The President was not asking Lee to squelch the case but was seeking Hatch’s release from military confinement while the investigations continued. Lee consulted Meigs, who replied that the investigation so far was “very much against Capt. Hatch” and it would be “highly improper” to pass over such serious charges and restore Hatch to duty until a trial cleared him of wrongdoing. Meigs recommended that Lincoln press General Halleck, the supreme Union commander in the West, to initiate the earliest possible court-martial proceedings. All this correspondence was forwarded to Halleck.24

As the case dragged into the second half of March, the options narrowed to two: preparing a court of inquiry into the allegations against Hatch (forming the basis for a court martial) or creating a special commission, like the one meeting in St. Louis, to examine and settle all the Cairo claims. Hatch’s attorney Jackson Grimshaw, in private and public letters, demanded an investigation by court martial or court of inquiry, in which there would be sworn testimony and Hatch could confront his accusers face to face. Grimshaw claimed that Hatch was the victim of a smear campaign being mounted by disappointed dishonest contractors and political opponents of Illinois’s staunch Republicans.25

Despite Grimshaw’s urging and General Grant’s initial support for a court martial, time loomed as a major obstacle to convening a military investigation. Establishing a paper trail that linked payment vouchers to accounts in Hatch’s ledger books would take several more weeks of research coordinated by Halleck’s office. The War Department, prompted by its St. Louis Commission and led by Meigs and Stanton, wanted to settle outstanding contract claims as quickly as possible and get on with the business of producing victories downriver (the battle of Shiloh loomed just two weeks ahead). Meanwhile, President Lincoln hovered in the background as Hatch’s patron, relentlessly badgered by his Illinois friends to expedite the case.

As things turned out, Halleck, characteristically cautious and deferential to Washington authorities, gave Lincoln the last word on how the case should proceed. Stanton and Meigs made their preference clear: a court would sit for a long time and divert too many officers from military duties, and contract claims required immediate settlement if supplies were to be procured to continue the Union’s down-river offensive. As Meigs wrote to Lee, and Lee passed on to Lincoln, “I fear that such a court would be long employed and that the services of the officers upon it could be ill spared.’’ An investigating commission consisting of civilians (like the St. Louis Commission) would avoid this problem; it could settle all outstanding claims, and it could also produce evidence to resolve the question of a court martial. Lincoln, opting for a speedy resolution of the claims and expecting that the investigation would clarify Hatch’s guilt or innocence, decided on the commission. He informed Meigs, who alerted Stanton on March 26. On April 2 the President wrote to Stanton to make it official and to suggest potential appointees.26

The foregoing sequence of events and communications does not support the accusation made by historians of the Sultana disaster that Lincoln intervened to squelch the charges against Reuben Hatch or to shield him from investigation. The idea that Lincoln moved to prevent a court martial is also misleading. On the contrary, Lincoln transmitted incriminating evidence in the case to the proper military authorities, pressed for a timely court martial (as did Hatch’s attorney), and sought to have Hatch temporarily reassigned while the investigation dragged on. Lincoln’s decision to convene a commission to examine Hatch’s claims was grounded in War Department precedent and recommended by Meigs and Stanton. A claims commission did not preclude an eventual court martial but represented an expeditious and neutral way to move the case forward amid wartime pressures of limited time and personnel. The president’s political influence did not save Reuben Hatch from prosecution, as Lincoln’s critics declare; instead, as we shall see, a shoddy investigation by the Cairo Commissioners did.

In May 1862 Stanton appointed George S. Boutwell, Charles A. Dana, and Stephen T. Logan to serve on the Cairo Claims Commission. Boutwell, formerly a Free-Soil governor of Massachusetts, had extensive experience in financial and banking investigations. Dana, who had been Horace Greeley’s managing editor at the New York Tribune, won Stanton’s attention by prodding General George McClellan to attack the Confederate army and put an end to “champagne and oysters” at headquarters. Logan was a former law partner of Lincoln and the only member who was appointed at the President’s recommendation. Stanton charged the commission “to examine and report upon all unsettled claims against the War Department at Cairo, Illinois, that may have originated prior to the first day of April 1862.” Each commissioner received a travel allowance and a modest government stipend of eight dollars a day. Former Judge Thomas Means of Leavenworth, Kansas—rather than Lincoln’s suggested candidate, John R. Shepley—was appointed as attorney for the Commission.27

Logan, Dana, and Means convened in Cairo in mid-June. They set up living quarters in a shed on the levee and organized a mess with General William K. Strong, the officer in command. Boutwell arrived a few days later; according to his recollections, their situation was “disagreeable to an extent that cannot be realized easily.” The summer heat was torrid; dead animals, the victims of the heat and earlier flooding, littered the ground; and every evening they endured thunderstorms and then higher water coming down the two rivers. Sickness was rife among the town’s inhabitants; Boutwell claimed he escaped it by eating moderately and drinking only tea and water from Iowa ice. Despite the heat—or perhaps seeking to escape it as quickly as possible—the Commissioners worked steadily, meeting almost daily in an office in “the Bank building” in town, most likely the City Bank of Cairo (1858–1865).28

Exactly what the Commissioners did has to be reconstructed from fragmentary evidence, since their official report disappeared from War Department files within a few years without being printed.29 The materials that remain in the National Archives include a journal with brief entries describing the Commission’s meetings, a partial alphabetical register of the claims and their disposition, and a small number of affidavits and letters pertaining to transactions.

According to surviving minutes, at the Commission’s first meeting on June 18 Dana and Logan were present along with solicitor Thomas Means; two days later Logan was named chair. The men drew up an announcement that the Commission was in session and solicited claims against the War Department incurred at Cairo prior to April 1862. The call for claims was published in newspapers at Cairo, St. Louis, Chicago, Springfield, Cincinnati, and Louisville. Within a few days Logan took ill and was unable to attend the commission’s meetings. He resigned on June 28 and was replaced as chair by George Boutwell, who had arrived on June 22. Logan’s seat was filled by Shelby M. Cullom, another Lincoln associate and the Republican Speaker of the Illinois House of Representatives.30

Reuben Hatch arrived in town on June 24. Sometime in April, while awaiting the commission’s investigation, Hatch had been released from local custody in Cairo by General Halleck and, at the request of General Strong, restored to duty as acting commissary of subsistence at Paducah, Kentucky. When Stanton found out, in a fit of pique he had Hatch rearrested. Hatch first appeared before the commissioners on June 27 but did not undergo examination because his attorney, Jackson Grimshaw, had not yet arrived. That day, the commissioners began examining claims.31 Thereafter they worked at a steady pace whose progress was tracked privately in letters from Grimshaw (who arrived at the end of the month) to Ozias Hatch, and noted publicly by a local reporter for the Chicago Tribune.32

The Tribune reporter, however, provided no account of the Commission’s most important meeting. On July 2 Captain Hatch appeared before the Commission accompanied by his counsel, Grimshaw. Immediately a pivotal confrontation occurred. Solicitor Means wanted Hatch sworn in and “examined generally on the management of the business of the Quartermaster’s Department” at Cairo while he was Assistant Quartermaster. Attorney Grimshaw refused to allow this, stating instead that the Commission could examine his client under oath regarding particular claims arising during his tenure. After conferring, the three Commissioners overruled Means and agreed with Grimshaw: Hatch would be asked only about particular claims, “as in their judgement may be necessary.”33

From that point on, most of the Commission’s meetings were spent examining individual claims presented by contractors and other aggrieved parties. Captain Hatch was present several times beginning on July 9, usually with his counsel, and was asked to certify under oath the accuracy of many vouchers presented. On July 12 Boutwell resigned, having been named Commissioner of Internal Revenue by Treasury Secretary Salmon Chase, and Dana was elected chair in his place. After July13 the group met every day until it concluded its business. The cutoff date for claims to be presented was July 25; the Commission worked feverishly on the remaining cases until its final meeting on July 31, at which its report was approved and a copy of its abstract of claims was made for the disbursing officer at St. Louis.34

All told, the Commissioners examined 1,696 claims, amounting to $599,219. The value of those approved and certified for payment was $451,105. The majority of the claims rejected were for damages allegedly caused by Union troops and requisitions made by the armies against citizens who had inadequate documentation, or whom the Commissioners determined to be disloyal. A particularly large claim of $33,000 by John Bird, a shipping agent from Bird’s Point on the Missouri shore opposite Cairo, was dismissed on account of his complicity with Confederates. A claim for damages to an Ohio River steamboat that General Grant had ordered seized was accepted by the Commissioners but disallowed after the war by the Senate Committee on Claims. Another set of rejected claims, which we know about only from Charles Dana’s published memoirs of 1898, concerned the Union government’s use of Cairo’s wharves for shipping and vacant lots for barracks and stables. The Commissioners decided that “the exigencies of the war” justified the temporary Union takeover of these assets rent-free.35

Of the claims the Cairo Commission accepted, most were credited at face value. “A very small percentage of the claims were rejected because of fraud,” chairman Dana later recalled. “In almost every case it was possible to suppose that the apparent fraud was accident.” Astonishingly, the Commissioners found no evidence of wrongdoing by Reuben Hatch. “All of Quartermaster Hatch’s claims were allowed, the investigation not having established anything of fraud or corruption in them,” the Chicago Tribune’s Cairo man reported.36 The full reason for Hatch’s exoneration may never be known, but surviving documents, viewed in light of the case’s complicated history, suggest some answers.

Much of the problem lay in the Commission’s interpretation of its mandate. Were the commissioners merely to examine outstanding claims or were they to undertake a larger investigation of the Quartermaster’s history and operations? Early on, the Commissioners made the unanimous decision that Hatch should not be compelled to testify on the general management of his office but only on particular claims. At the same time, the Commissioners apparently decided that they would not investigate the allegations of fraud uncovered by the Washburne Committee, the St. Louis Commission, and Assistant War Secretary Scott unless the relevant claims were presented for payment. (That was likely the implication of the “as may be necessary” limitation on Hatch’s testimony.) These two decisions drastically narrowed the Commission’s task, fatally compromised its investigation, and excluded much evidence that might incriminate Hatch.

At times the Commission seemed to take its investigative role more seriously. Two of Hatch’s clerks, George Dunton and a Mr. Dickinson, were examined under oath on business practices in his office. Dunton was questioned “at length” about hiring of men, renting of buildings, and purchases of coal. Dickinson testified about the payment of laborers. Hatch himself was asked about some purchases of steamboats that do not appear in the Commission’s partial roster of claims.37 The Commissioners took testimony relating to coal purchases from V. B. Horton, Jr., who, according to a witness deposed earlier by Assistant Secretary of War Thomas Scott, was systematically shortchanging the government. However, they found no wrongdoing on Hatch’s part and paid Horton’s claims in full.38 The Commissioners also conducted a reasonably thorough investigation of shoe and boot contracts of October and November 1861, but they uncovered no convincing evidence to sustain an agent’s allegation that he had to pay Hatch a 5% premium to obtain a government contract. (Hatch claimed that the agent himself was “skimming,” and the agent’s boss did not defend him.) The Commissioners did ascertain that Hatch had his clerk sign vouchers for him in his absence, a practice that violated military regulations.39

According to Dana, the Commissioners also looked into the charge that Hatch destroyed incriminating evidence: “The books and papers were taken out of Captain Hatch’s custody at the time of his arrest,” Dana wrote, “and there was not a particle of evidence produced before the Commission that he had had any control over them, subsequent to that event. One of his books was found on the shore of the Ohio River, but this book was an attempt made at the beginning of his service as Assist. Quartermaster to keep his accounts by the casual mercantile system of double entry, and there was nothing in this book to indicate any dishonesty or fraud on his part.” Ignoring the question of how Hatch’s account books ended up in the river, the Commissioners concluded that they demonstrated his inexperience, not dishonesty. In short, as Dana recalled 18 months later, “it was the unanimous conclusion of the Commission that there was no evidence before it to prove him [Hatch] other than an honest man.”40

Yet even by the loosest of standards no thorough investigation had been undertaken. When asked by Lincoln’s secretary Nicolay in February 1864 to clarify the Commission’s findings, Dana reported that the Commission examined the Chicago lumber purchases in dispute and found “no evidence whatever” of dishonest billing or charging of commissions. Surviving records call this judgment into question. The Commission’s alphabetical register of claims includes 10 small claims for lumber, all of which were approved at prices between $8.75 and $9.50 per thousand board feet—uninflated market prices. However, none of these were the Chicago lumber purchases in dispute. The Commissioners did not interrogate Hatch’s accomplices in the lumber fraud, Wilcox and Thomas, nor did they review the testimony of those men under oath before Washburne’s Committee. Hatch confirmed that no claims were submitted to the Commission relating to the lumber and ice transactions that had been targeted by the St. Louis board. These shady dealings were therefore not investigated. Instead, Hatch was allowed to insert a statement into the Commission’s record in which he claimed that the high prices he paid for lumber and ice in November 1861 were “a business necessity” in some cases, or a “misunderstanding” between the parties in others. He flatly denied receiving any commission: “I had not and never have had any pecuniary interest in the shape of commissions or otherwise in these or any other purchases made by me as Asst. Qr. Master.”41

For other transactions, the Commissioners evidently did not check the amounts in the discarded ledger books against vouchers at the War Department, as Assistant Secretary Scott had urged. Amazingly, for the majority of claims the Commissioners simply accepted Hatch’s sworn certification “as to their correctness and legality.” The only resistance to this procedure came later from quartermaster officials in St. Louis, who protested against paying claims presented without regulation vouchers. Dana replied in defense that the Commission’s job was to settle valid claims, not to examine vouchers for proper signatures.42

There is little doubt that Hatch was guilty of fraud in the lumber deals and probably in others. It was obvious that he ran his office in a haphazard and sometimes illegal fashion. But the Cairo Commissioners did not find—nor did they look hard for—evidence to support a court of inquiry into Hatch’s conduct. Besides their myopic focus on settling outstanding claims, was there more at work in this oversight? Did Hatch’s connection to Lincoln influence the Commissioners’ too-friendly inquiry?

Officials at the War Department certainly knew about Hatch’s friends in high places. As early as January 1862 prominent Illinois Republicans complained to Stanton about Hatch’s arrest. Hatch’s attorney Grimshaw called on Stanton in Washington, and Lincoln’s testimonial praising Hatch probably passed through the War secretary’s hands.43 Although Lincoln never asked to have the charges dropped but only to have the case resolved as quickly as possible, Stanton and his commissioners no doubt felt political pressure to acquit Hatch. Still, it is hard to imagine Stanton meekly acquiescing, given his prickly independence in other cases in which Lincoln referred cases of aggrieved friends and political allies to him. It was Stanton, for example, who had Hatch snatched from duty at Paducah and rearrested before the Cairo Commission met. And Stanton, not Lincoln, dominated the Commission’s makeup: One of the commissioners Stanton appointed (Logan) had been suggested by the President, but Dana and Boutwell were the War Secretary’s choices, and they were known for their tough stands against fraud and incompetence. It is also hard to imagine Boutwell and Dana, who were essentially auditioning for full-time government posts—Boutwell at the Treasury and Dana as one of Stanton’s assistant secretaries—trying to please Stanton with a lackluster investigation. The two men fully expected to sustain the charges against Hatch and were pleasantly surprised by the Commission’s findings. “There is rascality in some of the [western] Quartermasters I am pretty certain,” Dana wrote to a friend, “but generally the business of the army is honestly done. Charges of fraud, as I have ascertained, dwindle when you come to sift the evidence.” Years later Dana remembered that finding so little corruption in a case “where the charges seemed so well based … was a source of solid satisfaction to everyone in the War Department.”44

Clearly the commissioners cut Hatch enormous slack. They allowed for the difficulties an inexperienced officer faced in running the over-burdened quartermaster business early in the war, and they lowered their standards out of consideration for Hatch’s Unionist loyalty in a hotly contested border-state region. The irregularities the Commissioners did find—unauthorized signatures and deceptive vouchers—could be dismissed this way. “Much of the business,” Dana recalled, “had been done by green volunteer officers who did not understand the technical duties of making out military requisitions and returns.” His fellow commissioner Shelby Cullom said much the same thing: The Cairo claims concerned “property purchased by commissary officers and quartermasters in the volunteer service before the volunteers knew anything about military rules or regulations.” High prices had to be offered suppliers because of cash shortages, and Cairo vouchers were being sold in the market at a discount. Although such considerations could not excuse waste or frauds, the Cairo Commissioners allowed them to govern their assessment of Hatch.45

When the Cairo Commission’s report was made public, attorney Jackson Grimshaw, who had predicted that it would “fully exonerate” Reuben Hatch, was “much rejoiced” at the news, although he lamented that due to the investigations “the country has lost the offices of an able, honest officer for six months.” Ozias Hatch and other Illinois Republicans wrote to Lincoln asking that Reuben be released from arrest and remanded to duty. Lincoln forwarded these requests to Secretary Stanton and Quartermaster General Meigs, noting that Shelby Cullom “says that the Com. at Cairo investigated the accounts of R.B. Hatch & utterly failed to find any thing wrong.” Meigs nevertheless remained suspicious of Hatch and delayed his release until the president, after being informed by Ozias Hatch that his brother was still under arrest, personally ordered it six weeks later.46

In the end even General Grant, who initially had been keen for a court martial, endorsed the Cairo Commission’s finding and its exculpatory arguments. In February 1863 Grant recommended Hatch’s promotion to colonel and appointment to Quartermaster in the regular army. As Grant explained to Lincoln, Hatch “offered his services to his country early in this war and was placed from the start in one of the most trying positions in the Army.” Hatch had to run his department for many months without funds and faced the resentment of contractors who were paid late in inflated cash, a position “embarrassing and dangerous to his reputation even without a fault being committed by himself.” Referring to the Cairo Commission, Grant noted that “a full investigation has entirely exonerated him and even shown a most economical administration of his duties.” Grant, who was pleased with Hatch’s performance since the Commission adjourned, considered his testimonial “a simple act of justice to Capt. Hatch.”47

The Cairo Commission’s whitewash of Reuben Hatch opened the way for a succession of promotions for the well-connected army officer. Once the Commission acquitted Hatch, Lincoln had good reason to believe that Hatch was honest, and he saw no obstacles to promoting him and pleasing his Illinois Republican allies.

Hatch returned to active duty in February 1863, when with Grant’s and Lincoln’s endorsements he was appointed chief quartermaster for the eastern district of Arkansas. Shortly thereafter, a flurry of letters from Grant, General Prentiss, and Cairo Commissioner Cullom recommended that Hatch be promoted to colonel. Frustrated by his lack of promotion and apparently suffering financial difficulties, Hatch tendered his resignation in August 1863, then attempted to withdraw it. General Meigs, who still harbored suspicions of Hatch, recommended that Hatch not be reinstated, pointing out that Hatch had been absent without leave for three months. Again, Hatch mobilized his prominent Illinois connections—his older brother, Jesse Dubois, and Richard Yates, the Republican governor of Illinois, who lobbied with Lincoln and Stanton.48

Bowing to their patronage request in an election year, Lincoln in January 1864 asked Stanton to appoint Reuben Hatch a quartermaster in the regular army: “I know not whether it can be done conveniently, but if it can, I would like it.” Montgomery Meigs again was the main obstacle. Lincoln’s secretary Nicolay, Ozias Hatch’s former clerk, asked Charles Dana to remind General Meigs that the Cairo Commissioners had found Hatch innocent. Dana’s letter “removed a painful impression from my mind in regard to Hatch,” Meigs wrote, and in March 1864 he allowed Hatch to be promoted to chief quartermaster of the Thirteenth Army Corps.49

After the Thirteenth Corps was disbanded in June 1864, another campaign of testimonials from Grant, Lincoln, and his Illinois circle petitioned for Hatch to be promoted to colonel and assigned to the Department of the Gulf. After a brief reassignment and a bout of ill health, Hatch became an assistant adjutant general for the Department of the Mississippi and joined the staff of General Napoleon J.T. Dana in Vicksburg, and in February 1865 he became chief quartermaster. In that capacity he allowed the Sultana to be overloaded for its fatal trip upriver.50

We may never know conclusively whether chief quartermaster Reuben Hatch was bribed at Vicksburg or whether a different quartermaster would have intervened to prevent the Sultana’s departure so dangerously overloaded with passengers. Circumstantial evidence appears to damn Hatch for negligence, if not corruption, at the Vicksburg wharf. Insofar as Hatch was implicated in the Sultana’s horrific fate, the “trail of culpability” might plausibly lead to the White House, since President Lincoln had been eager to appoint and promote Hatch to please his Illinois backers.51 The evidence presented here suggests, however, that Lincoln’s course, together with Grant’s, relied heavily on Hatch’s complete vindication by the Cairo Commission, and thus that a larger share of the responsibility lay with that body’s questionable acquittal.52 The Cairo Commissioners did not fix their findings to please Lincoln, but their fatally limited and lax examination of Reuben Hatch’s quartermaster practices prior to April 1862 allowed the President to advance Hatch’s military career without qualms, a course that ended with that officer’s dubious and deadly entanglement in the Sultana tragedy.

Notes

- Published histories of the Sultana incident include James W. Elliott, Transport to Disaster (New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1962); Frank R. Levstik, “The Sultana Disaster,” Civil War Times Illustrated 12 (January 1974): 18–25; Wilson M. Yager, “The Sultana Disaster,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 35 (1976): 306–25; Jerry O. Potter, “The Sultana Disaster: Conspiracy of Greed,” Blue & Gray Magazine 7 (August 1990): 8–24, 54–57; Potter, The Sultana Tragedy: America’s Greatest Maritime Disaster (Gretna, La.: Pelican Publishing Co., 1992); Gene Eric Saleker, Disaster on the Mississippi: The Sultana Explosion, April 27, 1865 (Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, 1996); and Noah Andre Trudeau, “Death on the River,” Naval History Magazine 24 (August 2009), https://www.usni.org/magazines/naval-history-magazine/2009/august/death-river. ⮭

- For these reports, see The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880–1901) (hereafter OR), I, v. 48, pt. 1, 210–20; quotation is from 215. For summaries of the testimony, see Potter, Sultana Tragedy, 133–52. ⮭

- Report of Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt, in OR I, v. 48, pt. 1, 220. ⮭

- See Potter, Sultana Tragedy, 32–42; Saleker, Disaster on the Mississippi, 29–31; Trudeau, “Death on the River.” Lincoln’s complicity in the Sultana disaster climaxed a PBS television documentary, “Civil War Sabotage?” which was initially aired in July 2014 as an episode of “History Detectives: Special Investigations.” For the video and transcript, see https://www.pbs.org/opb/historydetectives/investigation/civil-war-sabotage/. As a TV critic noted, the documentary concluded by “finding (or refinding) a trail of culpability that leads to Lincoln himself.” Neil Genzlinger, “More Time for Sifting Among Clues,” New York Times, June 30, 2014. Lincoln’s guilt was also implied in a 2012 blues ballad titled “Reuben B. Hatch” by the band Dirt Farm: “Facing court-martial/ His brother petitions Lincoln/He was a financial supporter/ And sometimes an adviser/ To intercede and proceed/ So Hatch was never tried ….” http://thesultana.com/project/reuben-b-hatch/. ⮭

- Most of the surviving records are in the Cairo Commission Consolidated Correspondence File, RG 92, National Archives and Records Administration (hereafter NARA), Washington, D.C. Scattered letters and documents located elsewhere add to the picture. A preliminary attempt to re-create the Commission’s origins appeared in Charles V. Spaniolo, “Charles Anderson Dana: His Early Life and Civil War Career” (Ph.D. diss., Michigan State University, 1965), 84–98. The following history of the Commission elaborates on the summary presented in Carl J. Guarneri, Lincoln’s Informer: Charles A. Dana and the Inside Story of the Union War (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2019), 84–90. ⮭

- Potter, Sultana Tragedy, 36; Potter, “The Sultana Disaster,” 11; “Civil War Sabotage?,” PBS documentary (July 2014), transcript. ⮭

- Charles Dickens, American Notes (1843; New York: John W. Lovell Co., 1883), 747; Anthony Trollope, North America (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1862), 2:112; James M. Merrill, “Cairo, Illinois: Strategic Civil War Port,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 76 (1983): 242–56. ⮭

- For biographical information on Reuben Hatch, see “Reuben Benton Hatch (May 16, 1819–July 28, 1871),” at https://www.pikelincoln.com/explore-historical-pike-county/northern-district/griggsville-cemetery/. For Ozias Hatch and his circle, see “Mr. Lincoln and Friends: Ozias M. Hatch,” at the Lincoln Institute website: http://www.mrlincolnandfriends.org/the-politicians/ozias-hatch/. ⮭

- Ozias M. Hatch to Ward Hill Lamon, March 18, 1861, in Lamon, Recollections of Abraham Lincoln 1847–1865 (Washington, D.C.: Dorothy L. Teillard, 1911), 316; Lincoln to Cameron, July 26, 1861, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (hereafter CW), ed. Roy P. Basler (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1953), 4: 461. ⮭

- Harry J. Carman and Reinhard H. Luthin, Lincoln and the Patronage (New York: Columbia University Press, 1943), 334; David Herbert Donald, Lincoln’s Herndon: A Biography (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1948), 153; Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: The Improvised War, 1861–1862 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1959), 34; Ward Hill Lamon, Recollections of Lincoln, 27–28. See “Mr. Lincoln and Friends: Illinois Patronage,” http://www.mrlincolnandfriends.org/illinois-patronage/. ⮭

- House Reports 2, 37 Cong., 2nd sess., Serial 1143, li–lii, and Appendix: Journal of the Committee, 6–29 (testimony at Cairo). ⮭

- Chicago Tribune, December 12, 1861. ⮭

- Chicago Tribune, December 18, 1861; W.S. Hillyer to Grant, December 22, 1861, Cairo Claims Commission File, RG 92, NARA. ⮭

- Grant to Montgomery Meigs, December 29, 1861, The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant (hereafter PUSG), ed. John Y. Simon (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1967–2012), 3:351; Grant to Gen. Halleck, January 12, 1862, PUSG 4:37; Grant to Reuben B. Hatch, January 12, 1862, PUSG 4:44; Grant to Gen. Meigs, January 13, 1862, PUSG 4:46–47; Grant to Meigs, January 22, 1862, PUSG 4:79–80; J. F. Lee to John G. Nicolay, May 19, 1862, Lincoln Papers, Library of Congress (hereafter LC), online. ⮭

- Meigs to Stanton, January 31, 1862, Cairo Claims Commission file, RG 92, NARA; Meigs to Grant, January 4, 1862, PUSG 3:352. ⮭

- General H.W. Halleck to David Davis, January 13, 1862, PUSG 4:36n. ⮭

- Meigs to Grant, January 4, 1862, PUSG 3:352. ⮭

- Thomas A. Scott to Edwin Stanton, February 12, 1862, Stanton Papers, LC. ⮭

- Report of the St. Louis Claims Commissioners, March 10, 1862 (copy), Joseph Holt Papers, Huntington Library, San Marino, California. ⮭

- House Reports 37 Cong., 2nd sess., Serial 1143, pp. 1090–1137, lii. ⮭

- Grant to Meigs, January 22, 1862, and Meigs to Stanton, January 29, 1862, PUSG 4:79–80. ⮭

- “Our Cairo Correspondence,” New York Herald, January 11, 1862; Meigs to Stanton, January 31, 1862, Cairo Claims Commission file, RG 92, NARA. ⮭

- Nicolay to Therena Bates (his fiancée), February 2, 1862, in Michael Burlingame, editor, With Lincoln in the White House: Letters, Memoranda, and Other Writings of John G. Nicolay, 1860–1865 (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2000), 68; Orville Browning to Stanton, January 27, 1862, PUSG 4:59n.; Jackson Grimshaw to Lincoln, January 31, 1862, Lincoln Papers, LC, online; Lincoln to John F. Lee, February 1, 1862, CWL 5:116. ⮭

- Yates, O. Hatch, and Dubois to Lincoln, February 24, 1862; Lincoln endorsement to J. F. Lee, March 20, 1862; Meigs endorsement to Lee, March 21, 1862; all in PUSG 4:83. ⮭

- Grimshaw letter to editors, Chicago Tribune, May 29, 1862. ⮭

- Meigs to J. F. Lee, February 3, 1862, Lincoln Papers, LC, online; Meigs to Stanton, March 26, 1862, PUSG 4:83; Lincoln to Stanton, April 2, 1862, CW 5:177. ⮭

- Edwin Stanton to Charles A. Dana, January 24, 1862, Dana Papers, LC; Stanton to Dana, June 16, 1862, Dana Papers, LC; Lincoln to Stanton, April 2, 1862, CWL 5:177. ⮭

- George S. Boutwell, Reminiscences of Sixty Years in Public Affairs (New York: McClure, Phillips & Co, 1902), 293–94. ⮭

- After the Commission adjourned, chairman Dana sent the report and related documents to the Assistant Quartermaster at Chicago with instructions to forward them to the Office of the Quartermaster General at Washington, where their reception was noted in the Register of Letters Received on August 6, 1862. But within a few years they went missing. ⮭

- Cairo Claims Commission Proceedings, June 18, 19, 28, 1862, RG 92, NARA; Chicago Tribune, June 23, 1862. ⮭

- Chicago Tribune, May 29, June 26, 1862; CW 5:116, note (Hatch’s release in April 1862); Nicolay to John F. Lee, May 19, 1862, with endorsement by Montgomery Meigs, Lincoln Papers, LC, online; PUSG 4:84. ⮭

- See Jackson Grimshaw to Ozias M. Hatch, July 11, 20, August 1, 1862, in Ozias M. Hatch Papers, Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum, Springfield, Illinois (hereafter ALPLM). I am indebted to Christopher Schnell, Manuscripts Curator at ALPLM, for sending me scans of Grimshaw’s l862 letters in the Hatch Papers. See also seven reporters’ letters from Cairo to the Chicago Tribune, June 23–August 2, 1862. ⮭

- Proceedings, July 2, 1862, Cairo Commission File, RG 92, NARA. ⮭

- Proceedings, Cairo Commission File, RG 92, NARA. ⮭

- Dana, Recollections of the Civil War (New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1898), 13–14; New York Times, August 5, 1862; U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Claims, 45th Congress, 3rd Session, Senate Report 553, December 12, 1878. ⮭

- Dana, Recollections, 14; Chicago Tribune, August 2, 1862. ⮭

- Proceedings, July 2, 3, 8, 1862, Cairo Commission File, RG 92, NARA. ⮭

- Thomas A. Scott to Edwin Stanton, February 12, 1862, Stanton Papers, LC; Proceedings, Register of Claims, Cairo Commission File, RG 92, NARA; Jackson Grimshaw to Ozias M. Hatch, July 11, 20, 1862, Ozias M. Hatch Papers, ALPLM. ⮭

- On the boot and shoe purchases, see Reuben Hatch to Benedict Hall, June 2 and 3, 1862; William B. Hall to Charles A. Dana, July 7, 1862; and other correspondence in the Cairo Commission file, RG 92, NARA; Jackson Grimshaw to Ozias M. Hatch, July 20, 1862, Ozias M. Hatch Papers, ALPLM. ⮭

- Charles A. Dana to John G. Nicolay, February 6, 1864, Cairo Commission File, RG 92, NARA. ⮭

- Charles A. Dana to John G. Nicolay, February 6, 1864; Proceedings, Register of Claims; Reuben Hatch to Charles A. Dana, July 25, 1862, all in Cairo Commission File, RG 92, NARA. ⮭

- Proceedings, July 10, 1862; P. Clark to Dana, August 27, 1862; Dana to Boutwell, September 3, 1862, all in Cairo Commission File, RG 92, NARA. ⮭

- Orville Browning to Stanton, January 27, 1862, PUSG 4:59. ⮭

- Charles A. Dana to James Shepherd Pike, July 24, 1863, Pike Collection, University of Maine, Orono; Dana, Recollections, 14–15. ⮭

- Dana, Recollections, 12; Shelby M. Cullom, Fifty Years of Public Service: Personal Recollections of Shelby M. Cullom, 2nd ed. (Chicago: A.C. McClurg & Co, 1911), 97. ⮭

- Jackson Grimshaw to Ozias Hatch, July 20, August 1, October 12, 1862, O. M. Hatch Papers, ALPLM; Ozias Hatch to Lincoln, August 11, 1862 (copy), Cairo Commission File, RG 92, NARA; Orville Browning to Lincoln, n.d., RG 107, NARA; Lincoln to Meigs, August 15, 1862 (copy), Cairo Commission File, RG 92, NARA; Lincoln to Stanton, September 27, 1862, CW, Supplement I, 154; Meigs to Gen. Lorenzo Thomas, November 8, 1862, RG 94, NARA. ⮭

- Grant to Lincoln, February 8, 1863, PUSG 7:297–98. ⮭

- PUSG 7:298n; Potter, Sultana Tragedy, 38–39. ⮭

- Ozias Hatch to Jesse K. Dubois, December 30, 1863, Lincoln Papers, LC, online; Lincoln to Stanton, January 14, 1864, RG 94, NARA, quoted in PUSG 7:298n.; Meigs, endorsement on Charles A. Dana to John G. Nicolay, February 6, 1864, Cairo Commission File, RG 92, NARA. ⮭

- Potter, Sultana Tragedy, 40–42. For Grant and Lincoln’s recommendations, see PUSG 11:357. On February 1, 1865, Hatch was called before an examining board in New Orleans, which found that his ignorance of regulations and accounting practices made him “totally unfit to discharge the duties of assistant quartermaster.” However, the board’s report was not forwarded to the secretary of war for action by the president until June 3, the day Hatch was relieved of his duties and several weeks after Lincoln’s death and the Sultana incident. See Potter, SultanaTragedy, 41–42. ⮭

- Genzlinger, “More Time for Sifting Among Clues,” New York Times, June 30, 2014. ⮭

- I have found no evidence that Grant or the former Cairo Commissioners connected the Sultana disaster to Hatch’s earlier exoneration by the Commission. Immediately after the explosion, Grant assigned his aide de camp Adam Badeau to investigate. Badeau’s findings were incorporated into General Hoffman’s report, which listed Hatch among those “censurable.” Grant must have read Badeau’s report before he forwarded it to Washington. See PUSG 15:533. ⮭