Sections One and Two of this article appeared in the Spring 2022 issue.

Section Three: Analysis of the Narrative

It is important to note that fully one-third of Cordelia Harvey’s narrative takes place before her visits to Lincoln and the White House. In terms of story and point-of-view, the tale of her year-plus service as an official nurse and ‘sanitary agent for the state of Wisconsin’ (an inspector of hospital and medical conditions among the troops and what we would today call a patients’ advocate) among the Union hospitals and camps of Missouri, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Mississippi allows the reader to become familiar with her voice and character.1 In a word, she comes across as redoubtable: a determined woman in the altogether male world of the military.

When it came to bettering the medical and sanitary conditions of wounded soldiers, as a ‘social gospel Christian’ Harvey would not take ‘no’ for an answer, despite the obstacles strewn in her way by the military bureaucracy. What is more, she had a keen and practical intelligence and a most persuasive voice (as Lincoln would discover).From all accounts she was not beautiful, although possessed of a strong, magnetic personality, and delightfully frank, yet charming manners. Her tact was unusual, therefore she succeeded in accomplishing things in which other people failed. United with this tact was an indomitable will and an untiring persistence.2

Immediately after the horrific Battle of Shiloh (Tennessee), April 6–7, 1862, Harvey’s husband, Louis P. Harvey, Governor of Wisconsin, had traveled to the vicinity of the battlefield (Pittsburg Landing and Savannah), as head of a delegation to aid sick and wounded Wisconsin soldiers; the three Wisconsin regiments involved in the fighting had been decimated.3 In a freak accident on April 19, Gov. Harvey, while attempting to step from a landing onto a steamboat, lost his footing and fell into the Tennessee River and drowned.

When this tragic news reached Mrs. Harvey back in Madison, she fainted dead away: ‘[s]he was taken home, where for a short time her grief unsettled her mind.’ Yet only a few months later, while still in mourning, she sought something to do that would further the Union cause. She might, as so many women did, have worked voluntarily on the home front. But her independence of person and mind came to the fore. She wanted to go South, where her husband had perished, to help Wisconsin casualties of the war regain their health. On September 10, the new Wisconsin governor, Edward Saloman, appointed her “sanitary agent at St. Louis, where she arrived on Sept. 26.”4 By November she may have returned to Madison, for a government document indicates that some time that month she took delivery of a wagon load of supplies that might comfort though not cure the afflicted soldiers whose welfare she was to supervise:5 A tote of Catawba wine and a handful of brandied cherries, balanced by a spoonful of raspberry vinegar and a pickle or two: These would surely have helped the morale of invalided troops, which, as Harvey soon discovered, was about all she could initially achieve, given the state of medical care in the field.

What Mrs. Harvey encountered south of St. Louis—in Kentucky, Arkansas, southern Tennessee, and northern Mississippi—was the shocking reality of what was left behind after a major Civil War campaign had moved on. The hundreds of Union sick and wounded had but poor chances of recovering. What their injuries and amputations hadn’t done to their health, the climate and the unsanitary conditions in the camps and hospitals did. Death from infection and other kinds of diseases often resulted, even when the original battle wounds had been treated according to the best medical practices of the day. She wrote:

For the next several months she was almost constantly on the move, from one military hospital to the next, down the Mississippi River as far as Vicksburg and back up along the Arkansas side.6 Her work was constant and taxing. On December 15, 1862, she wrote to Gov. Saloman from Helena, Arkansas, that despite this “my health was never better. I get so tired at night that I think I shall be ill tomorrow, but in the morning I am quite rested & ready again for my labor. Surely my God & Father has watchful care over me.”7These hospitals were mere sheds filled with the cots as thick as they could stand with scarcely room enough for one person to pass between them. Pneumonia Typhoid and Camp fevers; and that fearful scourge, of the Southern swamps and rivers chronic diarrhea occupied every bed. A surgeon once said to me ‘there is nothing else there; here, I see Pneumonia and there fever and on that cot another disease and I see nothing else! You had better stay away, the air is full of contagion: and contagion and sympathy do not go well together.’ (ms. 3 = JALA 43:1, p. 72)

But if her will never broke, eventually her health did. As she was returning to Memphis from Vicksburg, in the spring or early summer of 1863, Harvey fell ill and was sent home to Wisconsin to recuperate.8 It had been her protracted and harrowing experience of tending large numbers of helpless and often hopeless sick and wounded soldiers that had given Harvey her big idea. Now, as she herself convalesced, she must have felt more than ever the truth behind that idea: move the men back home, provide both a better climate and better sanitation and care, and many more would heal, instead of die, and be able and willing to rejoin their regiments.

“One would almost have thought him deformed” The First & Second Interviews: Sunday, Sept. 6, 1863

Although she and her cohort seem to have worked tirelessly ‘within the system’ to gain the ear of someone with sufficient authority, including through correspondence from Wisconsin governor Edward Salomon to Lincoln himself, they were balked at every turn.9 “For nearly a year this question [of northern hospitals] was agitated, and urged with all the force, that logic, position, and influence could bring to bear; but all in vain” [ms. 17]. At last they determined to make a direct personal appeal to President Lincoln: “It is always best if you wish to secure an object, if you have a certain purpose to accomplish to go at once to the highest power be your own petitioner in temporal, as in spiritual matters officiate at your own altar, be your own Priest” [19]. Or priest-ess: So it was that Cordelia Harvey appeared at the White House the morning of Sunday, Sept. 6, 1863, having traveled from Vicksburg, Mississippi, home to Wisconsin, then on to visit friends (or family?) before arriving in Washington, D.C. She brought with her this petition:

To his Excellency, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States.

The undersigned, citizens of _______ County, in the State of Wisconsin, beg leave most respectfully to present their earnest appeal in behalf of the sick and wounded volunteers from Wisconsin (as well as in behalf of all other sick and disabled loyal soldiers of the Armies of the United States,) who are suffering disease and death, which they can only be recovered from by the establishment of suitable hospitals in the North, or by a return to their own homes. The invigorating atmosphere of our Northern climate would give them life and strength—the heated and fetid air of our Southern Hospitals only wasted energies and final death. Do our Fathers, Husbands, Sons and Brothers deserve this? Will an enlightened and christian government permit that which they can so easily prevent? Our noble ones must not be denied the right to life and health because disabled in their country’s service.

We therefore pray that our sick and disabled soldiers be granted such furloughs as shall enable them to return to their homes, recover their health, and be again prepared for service. And that proper hospitals be established at once in Wisconsin for those who have no homes. Humanity to our soldiers and justice to our country alike demand this.

And, as in duty bound, your petitioners will ever pray.10

“I had never seen Mr. Lincoln before,” Cordelia Harvey writes of that initial meeting. And she continues with a pencil-sketch that conforms with countless others: “He was alone in a medium sized office-like room, no elegance, in him. He was plainly clad in a suit of black, that ill-fitted him. No fault of his tailor however, such a figure could not be fitted. He was tall, and lean, and as he sat in a folded up sort of way in a deep arm chair, one would almost have thought him deformed…. When I first saw him, his head was bent forward, his chin resting on his breast & in his hand a letter, which I had just sent into him.” [21]. Surely this was a letter of introduction, stating her business, but from whom she does not say.11 At first Lincoln receives her barely politely:

Judge and Justice: it is difficult to ‘read’ Harvey’s tonality here. While the portrait of Lincoln’s face fits the archetype of tragic melancholy so often associated with Lincoln late in his life, her other words in this context are far less exalting. She implies that the president does not rise to greet her, though, remaining seated, he does offer his hand and bids her take a seat—”so much for Republican presentations and ceremony.” Is she pointing up a fault in manners, a failure somehow to meet her social expectations? Or is it merely a light remark about the great man’s unconventional behavior?The Pres’t took my hand, hoped I was well, but there was no smile of welcome on his face. It was rather the stern look of a judge who had decided against me. His face was peculiar, bone, nerve, vein, and muscle were all so plainly seen, deep lines of thought and care, were around his mouth, and eyes. The word justice, came into my mind, as though I could read it upon his face [22].

Lincoln begins their session peremptorily: “Madam!,” he began, “this matter of Northern hospitals has been talked of a great deal, and I thought it was settled, but it seems not, what have you got to say about it?” Though there are no tonal words here—excepting the emphasis on ‘you’—one can almost hear the fatigue and exasperation in the president’s voice. But, given an opening, Harvey plunges in, and forcefully:

Lincoln “shrugged his shoulders” and proceeded to chop at her logic: How can one man become ten? “I don’t see how … sending one sick man North is going to give us in a year ten well ones” (a “quizzical smile played over his face” as he said this). Condescension on Lincoln’s part? Realizing that she had indeed ‘misspoken,’ Harvey parries: “Mr. Lincoln, you understand me I think—” and thrusts: “I intended to have said if you will let the sick come north, you will have ten well men in the army one year from today where you have one well one now whereas if you do not let them come they will all be dead” [24].Only, this Mr President, that many soldiers in our western army, on the Mississippi river must have northern air or die. There are thousands of graves all along our Southern rivers, and in the swamps for which the Government is responsible, ignorantly undoubtedly but this ignorance must not continue. If you will permit these men to come North you will have ten men where you have now one [24].

They will all be dead…. This would have reached Lincoln, and his attempt at a riposte is unworthy of Harvey’s argument: “Yes! yes, I understand you, but if they are sent north they will desert, where is the difference. Dead men cannot fight and they may not desert.” With his anger or at least his annoyance growing (“Mr. Lincoln’s eye[s] flashed as he replied”): “a fine way to decimate the army we should never get a man of them back not one, not one.” [25] Harvey must have felt this as a black slur on the Wisconsin boys, all volunteers with more than a year left in their three-year enlistments. But when she speaks up for their loyalty to the Union cause, Lincoln will have none of it. “This is your opinion he said, with a sort of sneer,” and, further to his attitude that she doesn’t know what she’s talking about, begins to lecture her on the facts of war: “Mrs. Harvey, how many men do you suppose the government was paying in the Army of the Potomac at the battle of Antietam, and how many men do you suppose could be got for active service at that time. I wish you would give me a guess.” He changed the subject on her, to little avail, as she replied, “I know nothing of the Army of the Potomac, only there were some noble sacrifices there, when I spoke of loyalty I referred to our western army” [25–26]. (It had been nearly a year since the Battle of Antietam in Maryland, the victory that William Seward had demanded before Lincoln issued his Emancipation Proclamation. How strange that a ‘McClellan subtext’ occurs in Harvey’s narrative, caused by Lincoln: see interview four below).

As if she had not just been speaking, he said, “Well! now give a guess? How many?” She of course had no idea. According to the president’s figures, of more than 170,000 men, fewer than half “could be got for action.” So what? “It was very sad,” Harvey replied, “but the delinquents were certainly not in northern hospitals, neither were they deserters therefrom, for there are none. This is therefore no argument against them.” The vaunted logician is put into vulnerability by the determined woman from Wisconsin. Not yet ready to topple his king, Lincoln temporizes: “Well! well! Mrs. Harvey you go and see the Sec’y of War and talk with him and hear what he has to say.” Lincoln endorsed her letter of introduction with a note to Stanton, perhaps hoping not ever to see her again. But she wouldn’t be discarded so easily. “May I return to you Mr. Lincoln? I asked, Certainly he replied and his voice was gentler than it had been before. I left him for the War Dept I found written on the back of the letter these words. Admit Mrs Harvey at once, listen, to what she says she is a lady of intelligence and talks sense.” [26–27]

Stanton, it turned out, had little to say to the importunate woman. Despite Harvey’s encomium to the Secretary of War, interpolated into her ms. (“I never knew a clearer brain, a truer heart, a nobler spirit, than Edwin M. Stanton” [28]), it is pretty clear he simply wished to get rid of her with dispatch. He said that nothing could be done on the question of northern hospitals until the U. S. Surgeon General, William A. Hammond, returned from what promised to be a very long inspection trip to Union army hospitals up and down the Mississippi—the irony here is palpable, for the ‘west’ was where Harvey had been for more than a year, and the conditions Hammond was to report on were the very disturbing scenario she had documented as part of her case to Lincoln. Moreover, Hammond seems to have been sent on a kind of snipe hunt just to get him away from Stanton, with whom Hammond had recently quarreled. (Hammond would soon be fired and then court-martialed.)12 Finally, as Lincoln himself would observe when she returned to him later that day, “Mr Stanton knows very well there is an acting surgeon general here” [32], from whom the secretary might have sought advice or to whom, at a minimum, referred Harvey. Thus Stanton was putting her off, and for good, as he must have thought. She, however, was far from deterred: “‘Good morning,’ I said and left him not at all disappointed” [30].

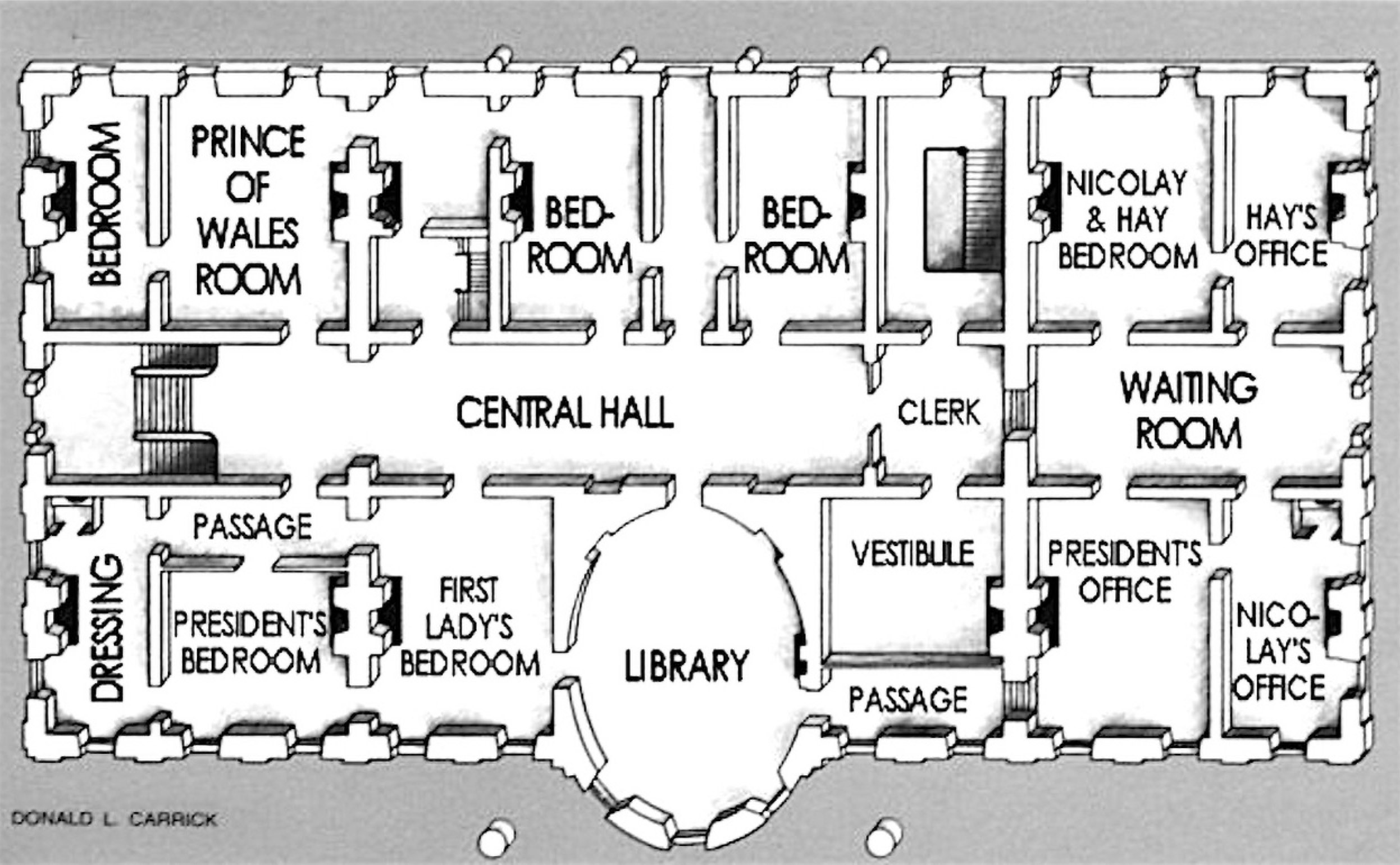

When she returned to the White House, “past the usual hour for receiving,” she was sent in directly to Lincoln—that is, not kept waiting in the reception area (see Figure 1):

Though, it would seem, Lincoln was facing or at an angle to Harvey from his desk, she was evidently far enough away and perhaps out of the light and escaped his notice. She thus was able to eavesdrop on a scene of typical Lincoln comedy: office seeker (or his delegate) pushing for some appointment; the president fending him off with a to-the-point story. The ‘gentleman’ proposed the promotion of someone or other—Mrs. Harvey could not hear clearly just who—to the rank of brigadier general in the Union Army, given that “so many Col’s are commanding Brigades” [30].I found my way to the back part of the room, and seated myself on a sofa, in such a position that the desk was between me and Mr. Lincoln. I do not think he knew that I was there. [A] gentleman with him had given him a paper. The Prest looked at it carefully and said ‘yes, there is sufficient endorsement for any body. What do you want?’

Did Harvey truly overhear Lincoln’s telling of this ‘bulls and cows’ story, or had she already known the presidential joke before coming to Washington, later interpolating it (fictionally) into her narrative? It is much more likely that the scene unfolded just as she relates it. Why risk the credibility of the entire narrative by fictionalizing a trivial incident of comic relief? Yet, interestingly enough, this particular heuristic on Lincoln’s part, while very little known (see fn. 16), had appeared in at least two newspapers in 1862. Here is the item in the San Francisco Examiner for Sept. 16: This notes both the authority, ‘gentleman,’ and the printed source, ‘St. Louis Paper.’ The story, though retold here in a rather unfunny fashion, is pretty much cognate with Harvey’s version.At this the President threw himself forward in his chair in such a manner as to show me the most curious, comical face in the world. He was looking the man straight in the eye—with the left hand raised in a horizontal position and his right hand patting it coaxingly—he said, ‘my friend, let me tell you something about that you are a farmer, I believe, if not you will understand me…. Suppose you had a large cattle yard full of all sorts of cattle, cows, oxen, and bulls and you kept selling your cows and oxen taking good care of your bulls, bye and bye you would find you had nothing but a yard full of old bulls good for nothing under heaven, and it will be just so with my army if I don’t stop making Brigadier Genls” [31].13

Lincoln’s telling a story is almost de rigueur in any recollected story about the president. We know he was constantly pestered about military and civil appointments. So if ‘bulls & cows’ proved useful to show someone especially bothersome to the door, it is hardly far-fetched to believe that he deployed it many times, nor that Harvey heard the master storyteller in action and rather neatly retold it, the better to enhance her narrative’s credibility. As does what she next writes: “you should have seen Mr. Lincoln laugh, he laughed all over, and fully enjoyed the point if no one else did. The story, if not elegant is certainly appropos [sic]” [31].

At this point there is a minor ambiguity in the text. Harvey’s gloss on the significance of Lincoln’s story becomes puzzling. Although the petitioner and his petition seem to have been shown the door by Lincoln’s story and his outsized laughter, she says that the ‘gentleman’ had gone away from his interview ‘fully satisfied I doubt not,’ meaning, one infers, that he thought his request for the brigadiership was to be granted. Meanwhile, “[I]t was a saying in Washington when one met a petitioner, Has Mr. Lincoln told you a story. If he has it is all day with you he never says yes after a story” [32]. The phrase ‘all day with you’ points to a negative outcome, meaning ‘you are out of luck / a hopeless situation.’ What the Harvey narrative intends is that while the ‘gentleman’ may have thought he’d convinced Lincoln, in fact he hadn’t, and his client, whoever that was, would never become a brigadier general in the Union army. By contrast, as we shall see, it is Cordelia Harvey who tells Lincoln a story and after a pitched battle in persuasion elicits from the president a ‘yes.’

When Harvey, having assumed the seat of the previous petitioner, let Lincoln know that Stanton had put her off, she is somewhat surprised to find the president in a more receptive mood (“he spoke kindly of my work, said he fully appreciated the spirit in which I came”). Lincoln promised to speak to Stanton that very night and meet again with her again the following day. “He smiled and bade me good evening” [33].

‘I would rather have stayed at home’ The Third Interview: Monday, Sept. 7

With good reason, then, she “returned in the morning full of hope thinking of the pleasant face I had left the evening before,” only to find Lincoln sour, as if “annoyed by something.” What transpires over the next 14 pages of her narrative—far the most detailed and dramatic part of the whole—is best imagined as a protracted agon between two strong and stubborn people of great will and intelligence: one with almost immeasurable power at hand, the other with only righteousness as fuel; one a man who does not understand women, though he is almost hopelessly fascinated by them, the other a woman with perhaps unconscious sexual chemistry as part of her strength. A man of the cloth who apparently knew Harvey personally described her character this way: “Resolute, impetuous, confident to a degree bordering on the imperious, with power of denunciation to equip as an orator, she yet … does not underestimate the worth of true womanhood by attempting to act a distinctively manly part.”14 Such was the designing woman who appeared before Lincoln for the third time. Her tactics: make a nuisance of herself, first silently, then with one hell of a speech, an approach similar to the one she had so successfully undertaken with the Medical Director at the St. Louis hospital (see ms., 10–14).

… is Harvey’s acidic response. But duty must prevail over desire. So, in front of an “annoyed” president, and from her own possibly resentful self, she immediately launches a grand monologue, a soliloquy or oration really, but for a few judicious narrative insertions just to let the reader know that Lincoln is listening, and ever more attentively. She makes the case for Northern hospitals as anything but a great humbug, and she does so through two rhetorical ploys: appeal to Republican (Union) patriotism and the story of her personal experience as a nurse among sick and wounded Wisconsin soldiers in the South. Besides the thousands of dead at Shiloh and other places along the great river since, these many barely living invalids were “[m]en who have done all they could, and now when flesh, and nerve, and muscle are gone, still pray for your life, and the life of this Republic; they scarcely ask for that for which I plead” [37]. She is certain that such soldiers would do more for the cause if only they could. And they could, were they sent North for convalescence:She sat down and said nothing.

“Well,”—Lincoln, “with a peculiar contortion of face I never saw in any body else.

“Well”—Mrs. Harvey.

“Have you nothing to say?”

“Nothing, Mr President, until I hear your decision. You bade me come this morning. Have you decided?”

“No! But I believe this idea of Northern hospitals is a great humbug, and I am tired of hearing about it.”

“I regret to add a feather’s weight to your already overwhelming care and responsibility, I would rather have stayed at home.”

“I wish you had.”

“Nothing would have given me greater pleasure” [34–36]

Lincoln had listened to all this “intently.”I know because I was sick among them last spring surrounded by every comfort; with the best of care, and determined to get well, I grew weaker day by day until not being under military law my friends brought me North. I recovered entirely simply by breathing northern air [38].

What was Lincoln’s tone of voice? How would the director of this two-person play have him say “You assume to know more than I do”? Harvey gives us an indication: “I was hurt and thought the tears would come.” But she “rallied” and reiterated, as the cliché goes, her truth to power: “it is because of this knowledge—because I do know what you do not know that I came to you…. The question only is whether you believe me or not.” If so, hospitals. If not, “well …” [39–40].He had never taken his eye from me, now every muscle in his face seemed to contract, and then suddenly expand, as he opened his mouth, you could almost hear them snap, when he said “You assume to know more than I do” and closed his mouth as though he never expected to open it again sort of slammed it too [38–39].

That Harvey is getting the better of the encounter, if not the argument, may be inferred from Lincoln’s continuing obstinacy: “You seem to know more than surgeons do.” Not at all: she couldn’t begin to do an amputation. As for surgeons, she held that they are, most of them, sufficiently political to report what the President wants to hear. That is, negatively on northern hospitals. What is more, those government officials who inspect the hospitals (and perhaps she is thinking of Hammond here) do so indifferently at best.

No, she has come to the president from beside “the cots of men who have died, who might have lived had you permitted. This is hard to say but it is none the less true.” [42]I come to you from no casual tour of inspection, having passed rapidly through the general hospitals, in the principal cities on the river with a cigar in my mouth and a ratan in my hand talking to the Surgeon in charge of the price of cotton, and abusing the Generals in our army for not knowing, and performing their duty better, and finally coming into the open air, with a long drawn breath as though they had just escaped suffocation, and complacently saying, a very fine hospital you have here sir. The boys seem to be doing very well a little more attention to ventilation is desirable perhaps. [41–42]

Harvey, in her third intimate interview, is laying a burden of guilt on the president of the war-fractured United States, a man who is probably sitting within arm’s reach of her as she speaks. Her presence and her words disturb him. He appears to her angry, perhaps even ready to break down emotionally: “a severe scowl had settled over his whole face…. one vein across his forehead was as large as my little finger it gave him a frightful look…. “I have a good mind to dismiss every man of them [Wisconsin soldiers] from the Service and have no more trouble with them!” I was surprised at his lack of self control I knew he did not mean one word that he had said—but what would come next as I looked at him I was troubled fearing that I had said something wrong. He was very pale, the silence was painful …” [43–44].

That Lincoln would have said such a thing in the presence of a woman he had known for fewer than 48 hours may be both astonishing and hard to credit for those who have studied his reserved and socially inept way with women.15 It appears to be a personal confidence completely out of character, an abrupt statement from deep inside, delivered as if he were alone. And, indeed, psychologically, he was alone during that moment. Yet Harvey offers a clue that bolsters her claim, though she herself would not have known why: From the angry bluster of moments before, now “[a]ll severity had passed from his face. He seemed looking backward, and heartward, and for a moment to forget he was not alone.” Lincoln was known to lose himself in himself while in company. Typically, he would appear to others as wholly abstracted, his face deeply melancholy. Henry C. Whitney, a friend and fellow-circuit lawyer in Illinois, remembered such an occasion when, during an 1855 session of the court in McLean County, he noticed Lincoln“If you grant my petition, you will be glad as long as you live.” “I shall never be glad any more.” [45]

But something else is emotionally in play here. It is also well-understood by Lincoln biographers that he did not like to be challenged by women who forcibly presented their points of view to him. William O. Stoddard, one of his White House secretaries, observed that although Lincoln was capable of “chivalrous deference for women,” any female who “called upon him in the prosecution of business” was unlikely to receive “special privileges” because of her sex. Probably just the contrary:sitting alone in the corner of the bar, most remote from any one, wrapped in abstraction and gloom … It appeared as if he was pursuing in his mind some specific, sad subject, regularly and systematically through various sinuosities, and his sad face would assume, at times, deeper phases of grief: but no relief came from dark and despairing melancholy, till he was roused by the breaking up of court, when he emerged from his cave of gloom and came back, like one awakened from sleep, to the world in which he lived again.16

Sometimes that answer came in a tone of angry dismissal rather than “chivalrous deference;” other times Lincoln kept his temper with almost unnatural forbearance. When Jesse Benton Frémont, the wife of General John C. Frémont, called at the White House at midnight to deliver a letter from the general—and to restate rather than plead his case concerning the freeing of slaves in Missouri—Lincoln heard her out but eventually lost patience: “She … taxed me so violently with many things that I had to exercise all the awkward tact I have to avoid quarreling with her.”18[I]t seemed an unpleasant and irksome thing to him to have a lady present a petition for any favor when the same duty could as well have been performed by a man; and if there was anything contrary to propriety or policy in the matter presented, or if the petitioner presumed upon her feminine prerogative to press too far upon his good nature, she was very likely to receive an answer in which there was far more of truth and justice than flattery.17

“Awkward tact” is a marvelous phrase of self-awareness from Lincoln. When political necessity demanded, he could keep his cool, even before an aggressive and perhaps insolent woman such as Jesse Benton Fremont. The point is important regarding Cordelia Harvey’s account of this third interview with the president. She has pushed him pretty hard on the matter of northern hospitals. He pushed back, claiming 1) it has been discussed to death and 2) the experts do not agree with her about the need. Then she has attacked again, stating that the bureaucrats haven’t been on the ground nor seen what I’ve seen nor cared for the sick and wounded of the western army, especially the Wisconsin volunteers (she makes this important emphasis). Her image of the time-serving inspector with a walking stick and a cigar and an eye for the price of cotton is worthy of a cartoonist’s caricature and effectively undercuts the authority of all such Washington ‘experts.’ And Harvey’s evocation of the suffering she both saw and nursed, from St. Louis to Vicksburg, reads as both honest and moving.

Help these many soldiers heal and “they will return to fight your battles!” [45] Suddenly Lincoln is no longer on the verge of an angry outburst. Rather he enters that auto-hynoptic state in which “[a]ll severity had passed from his face. He seemed”—I think it is important to quote this once more—“looking backward, and heartward” with “a more than mortal anguish” now on his face. One senses from the narrative that some substantial moments have passed between the end of Harvey’s appeal and Lincoln’s painful utterance, “I shall never be glad any more.”

“[T]he spell must be broken,” she writes, and so she tries to bring him out of it with conventional, though no doubt empathetically spoken, words: “[D]o not speak so Mr Pres. Who will have so much reason to rejoice as yourself when the government is restored as it will be.” Here Lincoln bows forward from his chair and replies: “I know, I know … but the springs of life are wearing away.” Perhaps he didn’t sleep well the previous night? “[H]e never was a good sleeper, and, of course, slept less now than ever before.” [46] Getting a good night’s sleep: anodyne advice, as she must have known but tried anyway. Having comforted Lincoln what little she could, Harvey took her leave, still without a firm answer about the hospitals, but with a “cordial good morning” from the president. At this point the narrator is well on her way to accomplishing two things, one instrumental to the realization of the other and (she certainly thinks) more important. She is befriending Lincoln; and Lincoln is beginning to respond to her petition, and to her, as a friend would.

Tuesdays were cabinet-meeting days, but Lincoln had assured Harvey that the members had little to do and that were she to come to the White House at noon he would be free to see her, with an answer. When she arrived, however, she met a stream of visitors “being dismissed, because the President would receive no one that day.” Except her, as the doorkeeper said, pointing her to the reception area upstairs. There she waited in the large room for “three long hours and more,” Lincoln twice sending her the message that cabinet’s adjournment was imminent. While she tried to keep herself composed, she passed the time alone in the usually crowded hall with her thoughts at the prospect of failure: ‘I was fully prepared for defeat, every word of my reply was chosen, and carefully placed. I walked the room, and studied an immense Map that covered one side of the reception room’ [48–49]. Not counting servants—Mary Lincoln was away—Cordelia Harvey was very probably the only woman in the White House late that Tuesday afternoon.“No reference was made to any previous opposition”

The Fourth Interview: Tuesday, Sept. 8

Finally, Lincoln appeared. He “came directly into the room” from his office where the cabinet had been meeting, apologizing as he approached “with a shuffling awkward motion.” Mrs. Harvey, as so many before her, was taken aback by Lincoln’s tallness; she hadn’t seen him standing before this. Forgetting for a moment her rehearsed speech of defeat, Mrs. Harvey waved off the apology, solicitous of his fatigue, and suggested they not talk that night. No, no, take a seat, he said. “Mrs Harvey I only wish to tell you that an order equivalent to granting a hospital in your state, has been issued nearly twenty-four hours [ago]” [49–50].

She was told to come to him once more the next morning to receive a copy of the order. “I was so much excited I could not talk with him.” Lincoln, perhaps with his peculiar and awkward tact, but this time with the very best will, discerns that she is still overcome with emotion at the good news and diverts her by “talking upon other subjects. He asked me to look at the Map before referred to, which he said gave a very correct idea of the locality of the principal battle-grounds of Europe.”I could not speak I was so entirely unprepared for it. I wept for joy I could not help it. When I could speak I said God bless you. I thank you in the name of thousands who will bless you for the act. Then remembering how many orders had been issued and countermanded I said Do you mean really and truly that we are going to have a hospital now With a look full of humanity and benevolence, he said, I do most certainly hope so. He spoke very emphatically no reference was made to any previous opposition [50–51].

This is one of the odd details that give the Harvey narrative the solidity of true story-telling. Yet, in addition, there is an untold joke in the air, one of which she and Lincoln and her audience at the public lecture would have felt the ironic point. This map was the best thing George B. McClellan did, back at West Point or maybe ever, and it was a map of European battlefields.I am afraid you will not like it as well when I tell you, whose work it is.

It is well done whoever it may be. Who did it Mr Lincoln?

McClellan … He did it while he was at West Point [52].

The two of them stood silently together in the hall. How were they positioned: side by side, face to face, close to one another? Or did they return to their seats? How long did this quiet interval continue? With some degree of empirical probability, we can say that by this point Lincoln has spent more time alone with a woman other than his wife than he has since the Civil War began—something that would have hugely upset Mrs. Lincoln had she known; see below. By ‘alone’ I mean in private interviews, uninterrupted by anyone else, including those with open access to Lincoln such as his three secretaries, Nicolay, Hay, and Stoddard, none of whom seem to have been aware of the multiple visits of Cordelia Harvey to their chief.

Practically speaking, the business between the President and the Lady has concluded. Harvey has his word about the hospital, and it only remains to carry back a copy of the authorization to Wisconsin, which really should not require another meeting. Yet their encounter that evening continues. She tries to read Lincoln’s mind, which is once more in silent abstraction. “Perhaps he was ballancing in his own mind the two words which then were agitating the heart of the American people, words which have ever throbbed the great heart of nations, words whose power every individual has recognized, Success and failure.” [53] Then, without recording any words of good night between them, she leaves the White House.

“Did joy make you sick?” The Fifth and Final Interview: Wednesday, Sept. 9

Harvey’s appointment at the White House was for 9 a.m. She was more than an hour late, having “been sick all night.” “I suppose the excitement caused the intense suffering of that night. I was very ill” [55–56]. When she got to the reception room she found “more than fifty persons” waiting ahead of her. She thought to go, but the official on hand told her to stay, and after “but a moment among anxious expectant faces” she was announced and made her way toward Lincoln’s office, “not a little embarrassed to be gazed at so curiously by so many…” One woman among the crowd spoke up: “she has been here every day, and what is more she is going to win.” [54–55]

In fact, she had won. Yet here she is still feeling a sort of hangover from the emotions of the momentous day and evening before. What are these emotions? Do they include anything other than relief and gratitude? Are her feelings involved with the man as well as the president? This is a nice turn in the story, just before its conclusion. Lincoln had not slept well the night before last. He rarely or never slept well these days (“Macbeth hath murdered sleep”). Now Harvey has had her restless if not sleepless night. She might be forgiven had she said, Mr. President, please give me my paper and send me on my way home. I need to sleep.

Instead, Lincoln pulled up a chair next to his own, had Harvey sit down, and heard her apology for being late, illness the excuse.

“Did joy make you sick?” is a peculiar enough question to ask. But Lincoln’s oblique allusion to an angry Mary Lincoln is anomalous in the extreme, the sort of indelicate remark Harvey would never fabricate but in truthfulness cannot omit, though passing right over it in the narrative without comment. According to Lincoln Day-by-Day, Mary Lincoln was away from the White House during the entirety of Mrs. Harvey’s four days of visits.19 Her absence could well have freed Lincoln from his wife’s usual tight constraints around his social intercourse with other women. In any case, the remark forces an invidious comparison upon the reader: this woman who had come into his life four days ago, now seated before him for the last time, has at least this one quality of character, and a crucial one, self-possession, that his wife notably lacks. Thus Lincoln is impressed (if not infatuated) with her and has, by chance, some room to show it without fear of his wife’s finding out.[D]id joy make you sick[?]

I don’t know….

I suppose you would have been mad if I had said No.

No Mr Lincoln….

What would you have done?

I should have been here at nine o’clock Mr President.

… [D]on’t you ever get angry[?] … I know a little woman not very unlike you who gets mad sometimes.

I never get angry when I have an object to gain … to get angry you know would only weaken my cause, and destroy my influence. That is true, that is true … [56–57]

That Mary Lincoln’s jealousy of any other woman who so much as talked to Lincoln—even in company, much less alone—was almost uncontrollable was well known in Civil War Washington and has been frequently noted by biographers. According to her modiste and confidante in the White House, Elizabeth Keckly, “if a lady desired to court her displeasure, she could select no surer way than to pay marked attention to the President. These little jealous freaks often were a source of perplexity to Mr. Lincoln.”20 She said things to others that would have humiliated him had he known. As Michael Burlingame tells us, “less than three weeks before his death,” on a “long carriage ride” from City Point, Virginia, toward Grant’s front lines, a certain officer and gentleman, simply making conversation, had the ill fortune to mention, after observing to Mrs. Lincoln and Mrs. Grant that a battle was soon coming, he had deduced because all the officers’ wives had been sent to the rear. Except for one, to whom Lincoln had issued a special permit to stay. “What do you mean by that, sir? … Do you mean to say that she saw the President alone. Do you know that I never allow the President to see any woman alone.” Burlingame offers another and even more alarming instance of jealously unleashed that occurred during the same sojourn of the Lincolns at City Point. When told that the president, mounted on a “gallant,” charger, “insist[ed] on riding by the side of Mrs. [General E. O. C.] Ord,” Mrs. Lincoln grew angry and when she next encountered the general’s wife

Strange as it is, however, Lincoln’s “little woman who gets mad sometimes” utterance isn’t the oddest thing Lincoln says during this final interview with Cordelia Harvey. When he proposes naming the new hospital after her, she demurs, preferring instead that it bear her late husband’s name. As with everything else they have debated, Lincoln concedes, this time easily and with benevolence. She then regrets “hav[ing] taken so much” of his time.positively insulted her, called her vile names in the presence of officers, and asked what she meant by following up the President. The poor woman burst into tears and inquired what she had done, but Mrs. Lincoln refused to be appeased, and stormed till she was tired. Mrs. Grant still tried to stand by her friend, and everybody was shocked and horrified.’21

“I looked at him and with my usual impulse (emphasis added), clasping my hands together, you are perfectly lovely to me now, Mr Lincoln. He colored a little and laughed most heartily” (59). In showing emotion to complement her intellect, she has made Lincoln glad again, paying him a woman’s deeply personal compliment about his physiognomy—a thing he himself lamented that he almost never had from women.22 Lincoln was by no means “almost handsome,” as he too well knew from a lifetime of stoically, or even self-mockingly, enduring remarks about his ugliness, the cruel intensification of which during his presidency and the Civil War was all but historically incredible. “The springs of life are wearing away,” and this had become obvious to her over the past several days and interviews, until he finally was able to laugh “most heartily” near the end of their, yes, intimacy. Thus he truly became to Harvey, at that moment, “perfectly lovely.” Hers was an act of love, and Lincoln responded in kind:No, no….

You will not wish to see me again….

I did not say that, and shall not….

[Y]ou have been very kind to me and I am grateful for it….

[Y]ou almost think I am handsome, don’t you?

I arose to go, he reached out his hand, that hand in which there was so much power, and so little beauty, and as he held mine clasped, and covered in his own, I bowed my head, and pressed my lips most reverently upon the sacred shield, even as I would upon my country’s shrine. A silent prayer went up from my heart. God bless you Abraham Lincoln. I heard him say goodbye and I was gone [60].

Section Four: Josiah Gilbert Holland’s Use of the Harvey Manuscript

“a private letter from a lady”

J. G. Holland, of Springfield, Massachusetts, finished writing his Life of Abraham Lincoln some time late in 1865; the preface is dated November, 1865, the copyright filed in 1865. The first printed copies carry the year 1866 on the title page. Earliest among the major Lincoln biographies, the book was an immediate, tremendous success, with sales eventually surpassing the 100,000 level. The Life of Lincoln is a substantial volume of 544 pages, so Holland the professional journalist, poet, and novelist must have researched and written it at a demonic pace over the six months between conception and publication. As Lincoln scholar Allen C. Guelzo recounts, Holland visited Springfield, Illinois, “less than three weeks” after Lincoln’s burial there. There he talked to Herndon and many others, gathering reminiscences of his subject’s pre-presidential life, and went back East carrying notes with “some of the most important informant materials any early Lincoln biographer would gather.” His book, though sometimes dismissed as a work of Christian sentimentalism, would, in Guelzo’s estimation, ultimately become a foundation stone of the great temple of Lincoln biography. And not least because Holland succeeded in fashioning a believable portrait of the ‘inner Lincoln’—all the more remarkable as the biographer had never met the man whose life he limned.23

Holland sought the testimony of people who had known Lincoln intimately. He could not approach Mary, Robert, or Tad, nor were the high members of the late administration available to him. Few really knew their boss intimately, and fewer still—secretaries John G. Nicolay, john Hay, and William O. Stoddard, along with confidants like Noah Brooks—would likely have talked to Holland so soon after the assassination. But he did find a source that had two bonafides which a biographer of Abraham Lincoln cherishes: others’ multiple and visà-vis interviews with the president, in the sanctum of his White House office.

Exactly when and how Holland gained access to Harvey’s manuscript are mysteries yet to be solved. Nevertheless, speculation is warranted. She reportedly gave a public lecture based on the ms. “following the close of the war,” but no date or place is given by the source.24 The opening and closing paragraphs of the memoir imply a post-war composition, though these may be framing materials added to an earlier draft. It is quite possible that Harvey turned her notes from the Lincoln interviews into a narrative soon after the events at the White House, i.e. September 1863. Yet it seems more likely that she wrote nothing until after the assassination, because that horrific event, along with the end of the Civil War, would have provided a doubly strong motive for putting her story into form. In either case, and clearly, Holland acquired the autograph copy of her ms., the very one now reposing in the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library, in time for him to edit the Lincoln interviews for “liberal” use in Ch. 25 of his biography (pp. 443–53): “The writer has before him a private letter written by a lady of great intelligence and the keenest powers of observation, from which he has the liberty to draw some most interesting materials, illustrative of Mr. Lincoln’s mode of dealing with men and women, and with the questions which were presented to him for decision.”25

“[A] private latter from a lady”—does this suggest that Harvey knew of Holland’s work on the biography and sent her ms. to him unsolicited? Or had he heard of her public lecture and sought out the material, perhaps from a third party acting as intermediary? I cannot answer, having discovered no correspondence between Harvey and Holland. In any case, the phrase “has the liberty” suggests Harvey’s explicit permission to use her material as he will, and indeed Holland quotes and paraphrases at length, pretty much following her narrative right through its account of five meetings with Lincoln over four days in early September 1863. But Holland took a greater liberty with the ms. than this. Wherever he read something he wanted to use, he penciled in quotation marks or other editorial directions, no doubt to guide an amanuensis in copying out passages. These are clearly in a different hand from Harvey’s, almost certainly Holland’s own. If so, it is an easy step to infer that the ms. itself may well have been passed, as edited, to an amanuensis for incorporation into the book. And because the marked sections correspond so closely with what later appeared in print, we may be confident that the ms. now reposing in the Presidential Library is the very one Holland “had before him.”

To show Holland’s editorial hand, let us compare the opening section from the initial interview on Sunday, Sept. 6, 1863, as the ms. has it, and then in Holland’s version:

Holland gives Lincoln slightly better manners than Harvey had allowed him: rather than remaining seated when she entered, Lincoln makes a “feint” to rise. And, in adapting her description of the man in his sanctum, Holland makes two notable excisions. One is the second part of Harvey’s observation that Lincoln’s suit fitted him so “illy,” namely, that the tailor wasn’t to blame: “such a figure could not be fitted”; and the second her frank description of Lincoln folded up in his armchair to the extent that “one would almost have thought him deformed.”Harvey—

He was alone in a medium sized office-like room, no elegance, about him, no elegance in him. He was plainly clad in a suit of black, that illy fitted him. No fault of his tailor however, such a figure could not be fitted. He was tall, and lean, and as he sat in a folded up sort of way in a deep arm chair, one would almost have thought him deformed.

At his side stood a high writing desk, and table combined, plain straw matting covered the floor, a few stuffed chairs and sofa covered with green worsted completed the furniture, of the presence chamber of the President of this great Republic. When, I first saw him, his head was bent forward, his chin resting on his breast & in his had a letter, which I had just sent into him. He raised his eyes, saying, Mrs. Harvey? I hastened forward and replied Yes, and I am glad to see you Mr. Lincoln, so much for Republican presentations and ceremony. The Pres’t took my hand, hoped I was well, but there was no smile of welcome on his face. [21–22]

Holland—

He was alone, in a medium-sized, office-like room, with no elegance around him, and no elegance in him. He was plainly clad in a suit of black, that fitted him poorly; and was sitting in a folded-up sort of way, in his arm-chair. At his side stood a high writing-desk and table combined; under his feet was a simple straw matting; and around him were sofas and chairs, covered with green worsted. Nothing more unpretending could be imagined. As she entered, his head was bent forward, his chin resting on his breast, and his hand holding the letter she had sent in. He made a feint of rising; and, looking out from under his eyebrows, said inquiringly: ‘Mrs. ______?’ Hastening forward, she replied: ‘Yes, and I am very glad to see you, Mr. Lincoln.’ He took her hand, and “hoped she was well,” but gave no smile of welcome (443).

Likewise, in his re-writing Holland occasionally softens Mrs. Harvey’s account of Lincoln’s temper in the first and third interviews, either by taking out or putting in. As an instance of both in the same sentence, also from the first session, when Mrs. Harvey, having put her case for northern hospitals before him, has this:

Holland recomposes as this:Mr President could not see the force or Logic in this last argument. He shrugged his shoulders and said, “if your reasoning was correct it would be a good argument.” [23]

This is not to imply that Holland eliminates all of Lincoln’s petulance. To do so would work against his aim of revealing the inner person. Holland, however, is convinced that from the time of the second interview on the first day, “[n]o reader can doubt … [Lincoln] had determined to grant the lady her request; and this is to be remembered in the reading of the interviews which followed; for in these interviews occurred a strange exhibition of his penchant for arguing against and opposing his own conclusions—in this case almost with temper— certainly not in the most amiable manner.” (447) To put it mildly! And if Lincoln had a penchant for “opposing his own conclusions” in argument, this writer is not aware of it, nor is he convinced that it exists, despite Holland’s attempt at reader intimidation (“no reader can doubt”). My take, as should be clear from the analysis in Section Two (JALA 43:1), is that Lincoln needed to be shaken out of an emotional freeze based on irrational stubbornness occasioned by a lady’s showing him up in argumentation and eloquence, and who did so both by chipping at and melting the ice. But were Holland correct in his assertion, another explanation for Lincoln’s behavior suggests itself: He was playing Cordelia Harvey along, and doing so because he continued to desire her company.Mr. Lincoln could not see the logic of this. Shrugging his shoulders, and smiling in his peculiar, quizzical way, he said: “If your reasoning were correct, your argument would be a good one.” (444)

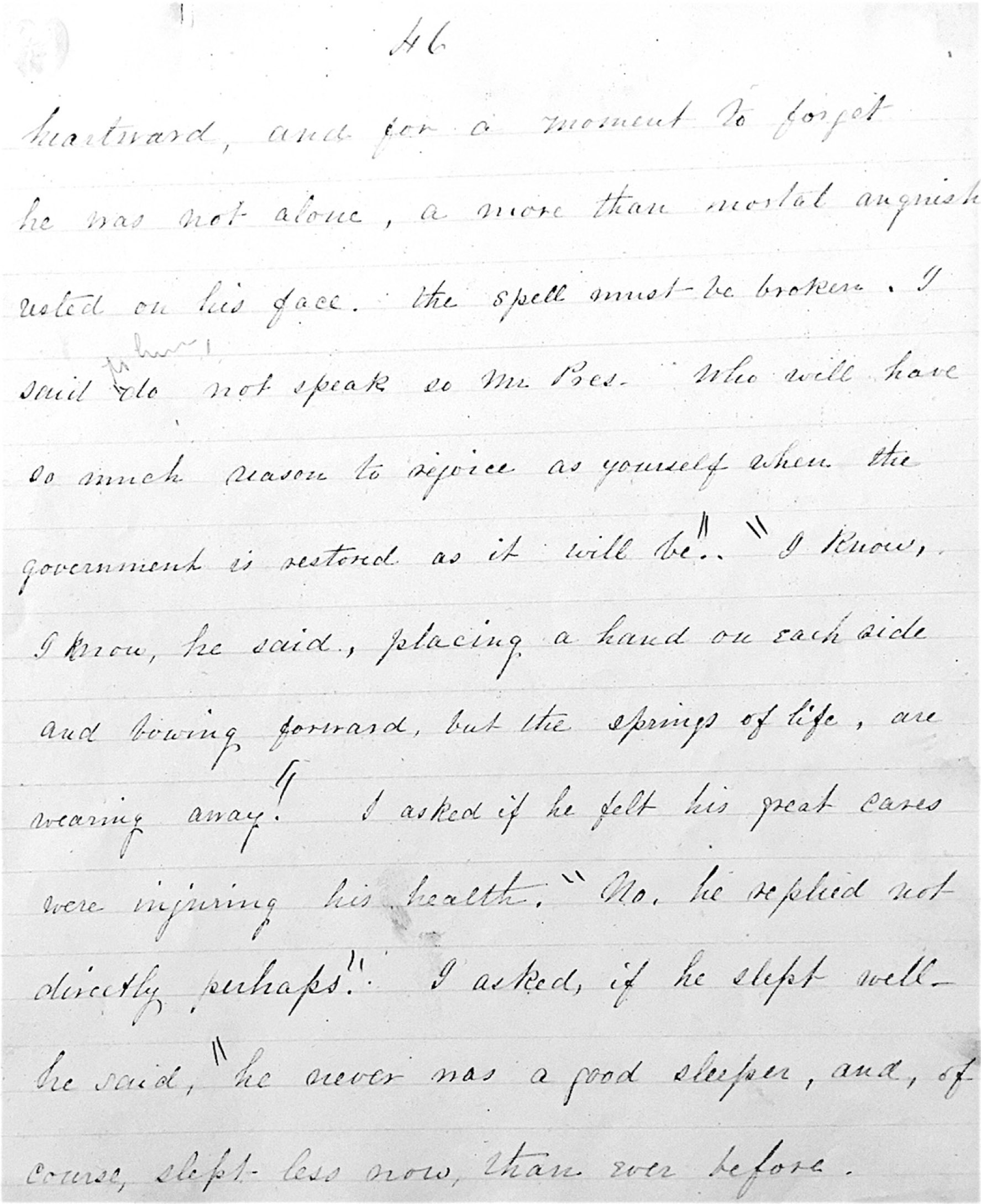

If Holland could diminish, he could also amplify his source. As we have seen, at the climax of the third interview, after Lincoln despairingly declares that he “shall never be glad any more,” and Mrs. Harvey attempts to comfort him with her point, Who will have greater cause than you to rejoice when all ends in victory? and Lincoln responds “I know, I know … but the springs of life are wearing away”—to this Holland appends “and I shall not last” (450, emphasis added). It is said that history is prophecy in reverse. Biography is absolutely so when the subject is dead, and famously and tragically dead, as in Lincoln’s case. In the photo-reproduction of p. 46 of the ms. (see below), we see graphic evidence of Holland’s working with Harvey’s text. He has put quotation marks around all the passages he will use verbatim and is not above, as noted, putting words in Lincoln’s mouth that Harvey didn’t! On balance, it is fair to say that Harvey wrote this entire section of Holland’s biography, while Holland himself merely edited it. Perhaps neither party saw anything wrong with such a procedure, as some of us might a century and a half later; but in any case Holland was most fortunate in finding this particular source as a way of getting glimpses of the interior world of his subject.

Coda: A gentleman biographer’s tact shows through in Holland’s elision (452) of Lincoln’s odd allusion to his wife in the final interview. But missing “I know a little woman not very unlike you who gets mad sometimes” makes Lincoln’s question to Mrs. Harvey—“Don’t you ever get angry?”—pointless without the comparison to Mary Lincoln. And when Lincoln and Mrs. Harvey make their adieux (453), Holland omits the kiss she gave the hand that held hers. Even though the kiss had been planted “most reverently,” as upon a “sacred shield,” it did not meet Holland’s standard of decorum. Did he think he was protecting his anonymous source’s virtue? Or that of his gentle readers?

Notes

- Edwin Bryant Quiner, ‘Mrs. Cordelia A. P. Harvey,’ Military History of Wisconsin (Chicago: Clarke & Co., 1866), 1,015. ⮭

- Ethel Alice Hurn, Wisconsin Women in the War Between the States (Madison: Wisconsin History Commission, 1911), 4. ⮭

- Wisconsin regiments at Shiloh: 14th, 16th, and 18th. I use ‘decimated’ here in its literal sense of one-tenth casualties, assuming the usual number of soldiers in a regiment as 800–1,000. According to research by one careful compiler, http://shilohnick.blogspot.com/2008/09/wisconsin-casualties-at-shiloh.html, the Wisconsin regiments had a total of 451 casualties (killed, wounded, captured, or missing in action). ⮭

- Quiner, Military History of Wisconsin, 1015. That the Lincoln administration was aware of Mrs. Harvey’s Wisconsin appointment is clear from this item in Appendix II (VIII: 500) to the Collected Works: Sept. 4. [1862], To Edwin M. Stanton, referring letter from Timothy O. Howe requesting appointment of Mrs. Lewis P. Harvey as “Embassadress” to Wisconsin soldiers, missing from DNA WR RG 107, Sec. of War Letters Received, P 171. Quiner had access to Mrs. Harvey’s ms. and used it freely in his biographical entry on her career. This means that the ms., as noted in Part I of this article, had to have been written some time between Lincoln’s assassination and the 1866 (month unknown) appearance of Quiner’s book. On this question of ‘when,’ see discussion of J. G. Holland’s Life of Abraham Lincoln below. ⮭

- Ms. receipt, Wisconsin. Governor: Letters and Papers on Ms. [sic] Cordelia Harvey, 1862–64, Wisconsin Historical Society, Madison Wisc. ⮭

- Quiner, 1,017. ⮭

- Cordelia Harvey to Edward Saloman, ALS, Letters and Papers on Ms. [sic] Cordelia Harvey, Wisconsin Historical Society, Madison Wisc. ⮭

- Quiner, 1,017. ⮭

- Roy P. Basler, et al., eds., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 9 vols. (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1953–55, for the Abraham Lincoln Association), Appendix 2, VIII: 411. The text of this letter is missing, but its context makes clear that Salomon was writing on the matter of northern hospitals for sick and wounded Wisconsin soldiers: “Mar. 15. To Edwin M. Stanton, referring letter from Edward Salomon to Lincoln, Feb. 25, 1863, recommending establishment of hospital at Prairie du Chien, Wis., missing from DNA WR RG 107, Sec. of War Letters Received, P 52.” ⮭

- The document is in the Wisconsin Historical Society, Madison. It is signed by 19 women, presumably all from Wisconsin, and may have been included with the “letter, which I had just sent into him, from a paper written by one of our senators, introducing me and my mission” [23]. However, the illustration above may be only the first page of a much longer document, since one unspecified source asserts that ‘eight thousand signatures were secured’ (quoted in Hurn, Wisconsin Women, 134). ⮭

- Mrs. Harvey might have presented Lincoln with two documents: a note of introduction and “a paper written by one of our senators, introducing me and my mission” [23]. Though this letter is not found in the Collected Works, the author was probably Sen. Timothy O. Howe (see fn. 4 above). ⮭

- Frank R. Freemon, Gangrene and Glory: Medical Care During the American Civil War (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998), 162. ⮭

- This story does not appear in either Don E. and Virginia Fehrenbacher, comps., Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln (Stanford, Cal.: Stanford University Press, 1996) or Paul M. Zall, Abe Lincoln Laughing (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982). Lincoln scholar Michael Burlingame notes a version of the story in the San Francisco Bulletin of Sept. 16, 1862 (he has kindly guided me to the text of the article); and J. G. Holland uses Harvey’s account in his Life of Abraham Lincoln (Springfield, Mass.: Gurdon Bill, 1866), 446. See Section 4 below for a discussion of Holland’s borrowings from Harvey’s ms. ⮭

- Rev. N. M. Mann, “Mrs. Cordelia A. P. Harvey,” in L. P. Brockett and Mary C. Vaughan, Women’s Work in the Civil War (Philadelphia: Zeigler, McCurdy & Co. 1867), 267. ⮭

- For an authoritative example of this scholarship, see Michael Burlingame, The Inner World of Abraham Lincoln (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994), Ch. 6. ⮭

- Paul Angle, ed. Henry Whitney, Life on the Circuit with Lincoln (Caldwell, Idaho: Caxton Printers, 1949), 147. ⮭

- Michael Burlingame, ed. William O. Stoddard, Inside the White House in War Times (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2000), 185. ⮭

- Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger, eds., Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1997), 123. ⮭

- She and Robert Lincoln were vacationing in New Hampshire’s White Mountains. Earl S. Miers and C. Percy Powell, eds., Lincoln Day by Day: A Chronology, vol. 3, 1861–65 (Washington: Lincoln Sesquicentennial Association, 1960), 205–6. ⮭

- Quoted in Burlingame, Inner World, 286. ⮭

- Burlingame, Inner World, 288–89. ⮭

- According to Henry C. Whitney, Life on the Circuit with Lincoln, 51, Lincoln liked to go to singing concerts, and one of his favorite ensembles was the Newhall Family, featuring “Mrs. [Lois E.] Hillis, a beautiful singer, whom Lincoln “greatly liked”—and who admired him. He attended a singing by the troupe in Bloomington, Illinois, during the spring 1855 term of the Circuit Court. The evening before, presumably at the hotel where both were staying, Lincoln had recited from memory his favorite poem, William Knox’s “Mortality,” to Mrs. Hillis (and perhaps others), then written out a copy and presented it to her. She was, he declared, “the only woman who appreciated me enough to pay me a compliment.” Albert J. Beveridge, Abraham Lincoln, 1809–1858, 2 vols. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1928), 1: 536, relying on Whitney’s Life on the Circuit. But when Whitney had written to Herndon in 1887—five years before the publication of Life on the Circuit—he phrased the unexampled compliment slightly differently: “Mrs Hilliss … was the only woman who liked him.” (Herndon’s Informants, 631) ⮭

- Allen C. Guelzo, “Holland’s Informants: The Construction of Josiah Holland’s ‘Life of Abraham Lincoln,’” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association 23: 1 (Winter 2002), 1. ⮭

- “A Wisconsin Woman’s Picture of President Lincoln,” Wisconsin Magazine of History 1 (1917–18), 233–55. ⮭

- J. G. Holland, The Life of Abraham Lincoln (Springfield, Mass.: Gurdon Bill, 1866), 443. ⮭