The acronym ‘SIC’ stands for ‘Standard Industry Classification’ codes. SIC codes are primarily of use to governments, but they are also one of the few resources for scholars looking to map the screen industries. The shortfalls of the SIC system have been recognized by trade groups lobbying for the interests of the UK’s screen industries. But as Harvey has pointed out, ‘[t]he Soho cluster [of industries] doesn’t easily comply with standard industrial classification codes. These tracking systems also fail to capture some of the more important relationships and interactions that are crucial to business. Current government tracking would place David Heyman’s Heyday Films as a SME [small to medium-sized enterprise] operating in Motion Picture, Video and TV programme production activities, rather than a creative entrepreneur and catalyst for most of the UK’s success in special visual effects worth many billions of pounds.’1

In this article I try to connect recent work on promotional screen industries with efforts by scholars such as Craig and Cunningham to propose a new programme of scholarship around the idea of an integrated screen industries ecology, engaging with the research agenda advanced by Cunningham and Flew.2 I do so by looking at a case-study analysis of the advertising screen production industry. This industry is a significant horizontally and vertically integrated sector of the screen industries headquartered in London’s Soho cluster. It emerged in the wake of the launch of commercial television in Britain in 1955 to produce content within a distinctive supply chain: commissioned by agencies that in turn are contracted and financed by brands. Newly formed production companies were launched in London’s Soho with specialist skills in the creation of television commercials (1955–2005) and digital internet advertising (2006–). This sector is thriving post-pandemic and is characterized by micro-entities and SMEs which make specialist advertising films but rarely own the intellectual property (IP) in those films.3 There are approximately 250 businesses of which 160 are production companies and the remainder VFX, post-production and audio-post houses. The average annual turnover is £4 million.4 The sector is represented by the Advertising Producers’ Association (APA) and by Screen Alliance. The constituent companies have an average of 12 fulltime permanent staff, although, in practice, this is largely composed of fractional and flexible workers. The largest of the companies are post-production houses with staff ranging from several hundred to over one thousand: The Mill, the Moving Picture Company, Framestore and Molinaire are the largest. These large post-production companies employ approximately 1,000 staff in the UK with additional employees based in the United States, China and India. The APA industry is forecast to be one of the success stories in the post-Covid economic recovery.

Aims and Methods

The aim of this article is to ask whether a research methodology built around SIC codes could identify ‘hidden’ sectors of the screen industries on which relatively little research has been done. By ‘hidden’, I mean sectors that are not immediately obvious to academics who are reliant on secondary sources and have no direct personal access to industry, or sectors of which academics are aware but lack publicly accessible data on industry shape or size. The screen advertising sector constitutes part of what David Lee has termed the British ‘independent television production sector’,5 which has executed core R&D functions for the screen industries as a whole,6 despite not being featured in many studies of that sector, including Lee’s own study. For Lee, the independent television production sector began in the early 1980s in the wake of the UK’s launch of commercial television in 1955 and the start of Channel 4. It recruited largely from the UK’s documentary production companies and was largely overlooked in film and television studies until some 10 years ago when Grainge and Johnson published their breakthrough work on the ‘promotional screen industries’ and Hardy his work on ‘branded content’.

This article reports a critical analysis of SIC methodology used by the UK government in relation to the APA industry. I report on a pilot scoping study undertaken into the SIC reporting methods of the APA member companies during 2018. This scoping study was undertaken following a programme of Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC)-funded research on the British music video industry which had highlighted the methodological challenges in data collection for scholars conducting research on the promotional screen industries. If the SIC codes are not helpful in identifying ‘hidden sectors’ in order to understand how the ‘screen industries’ as a whole work, then what value are they to scholars? Should scholars bother to examine them at all? If SIC codes are not useful, what other methods are available to researchers seeking not only to identify activity in the screen industries but to quantify that activity? Moreover, if SIC codes can only be used for contemporary analyses of industry, what methods are available to scholars conducting historical analyses? Mapping of the screen industries is an historical endeavour. Understanding how the APA sector sits within the independent sector as a whole is vital to a comprehensive mapping exercise.

First, I will outline the background to the use of SIC data by the British government to collect data on the screen industries as part of a programme initiated during the Blair governments to brand Britain as a creative economy. Then I will present the categories for mapping screen advertising production that have been used, along with the findings of the scoping study. I will then return to a discussion of the degree of the role SIC data might play in independent academic research on the screen industries.

Screen Industries and the SIC Codes

The concept of the UK’s ‘screen industries’ became fashionable as a result of the focus by three Labour Governments (1997–2001, 2001–5, 2005–7) on the UK’s growth potential as a ‘creative economy’. The category of ‘creative industries’ was itself created by the Labour Government in the late 1990s.7 The adoption of the term ‘screen industries’ appears to have been influenced, if not appropriated, from the work of researchers associated with Griffith University in Australia in the mid-1990s, foremost amongst them Stuart Cunningham. Within British scholarship, the conception of screen industries has risen in popularity since 2010. The screen industries special interest group (SIG) was launched at the British Association of Film, Television and Screen Studies’ (BAFTSS) first annual conference in Lincoln in 2013. The British Film Institute (BFI) subsequently moved to adopt the term and has commissioned a number of reports designed to measure activity within the screen industries. However, despite widespread use of the term ‘screen industries’, neither a precise definition nor a model of the concept has ventured in recent reports,8 and few have explicitly included discussion of the screen advertising sector.9 Without a precise definition, the general assumption is that the concept of screen industries includes the full supply chain: production (film, television), suppliers (camera, lighting, studios), freelance crew, distribution (including digital) and exhibition and platforms.

The British Standard Industry Classification (SIC) codes were introduced in the UK in 1948, following their launch in the United States in 1937 to classify business establishments by type of economic activity, and they remain the basis of government statistics about the UK’s industry. ‘Mapping’ and industry statistics have been a core post–World War II component of the strategy of nation-states to raise taxation in the pursuit of low unemployment and low inflation. The UK government, like many other governments, has relied on an industry classification system to collect data on creative industries. This is part of an agenda for all nation-states to collect statistics on GDP and favour growth. Potentially, SIC codes present a rich seam of data for quantitative analysis of any industrial sector because they define the number of workers involved in particular strands of business activity. The classifications that government uses are to some extent arbitrary and a result of political negotiations and influence. The data are intended to be useful and fit for purpose in diagnosing issues related to tools for stimulating economic productivity such as tax credits and interest rates, and training schemes. The UK Department of Culture Media and Sport (DCMS) offers a variety of codes for different elements of screen industries activity.

Since the 1990s, both SIC and standard occupational classification (SOC) codes have been a primary instrument of data collection in the Australian and UK governments’ drives to map their creative industries. One of the UK’s first major publications was the 1998 Creative Industries Report produced by the Work Foundation.10 SIC codes served as a primary data collection tool. They were used in subsequent DCMS Creative Industries Economic Estimates11 and served as a core method in the reports compiled by the National Endowment for Science, Technology and the Arts (NESTA) in 1998 to promote innovation in UK industry through a combination of programmes, investment, policy and research.12 SIC data also form a core component in the research work of NESTA’s Policy and Evidence Centre (PEC), launched in 2019, as part of the Creative Industries Clusters Programme led by the AHRC, and funded through the UK government’s Industrial Strategy Challenge Fund. Recent attempts to ‘map the creative economies of the UK and Australia have all used standard industry codes’.13

The SIC data have also been used by independent scholars. Pratt, for example, in his analysis of London as a ‘media centre’, a study examining the question of whether London – and ‘the media industries’ – fits the normative model of a ‘cluster’ in business studies, uses SIC codes to identify the prevalence of different ‘bits’ or ‘industries’ within the ‘media industries’ in London.14 One of the crucial values of the data for scholars is the potential they hold to deliver robust and accurate measures of the size of different sectors of the screen industries that can be used for comparative regional and historical analysis.

Findings: SIC Codes Used by the Screen Advertising Producers’ Industry

I was prompted to undertake this research into SIC codes when I sat in the audience of the launch of the Work Foundation’s report in 1998.15 It was not possible to tell whether the productivity of the screen advertising production industry had been counted as an output of the advertising industry or of the film and television production industry in that report. As a previous producer in the commercials and music video industries, I was curious to understand in which category data about those companies were positioned. The question led me to ask the CEOs of the companies I previously worked with which codes they reported under. None of the CEOs I questioned knew what a SIC code was.

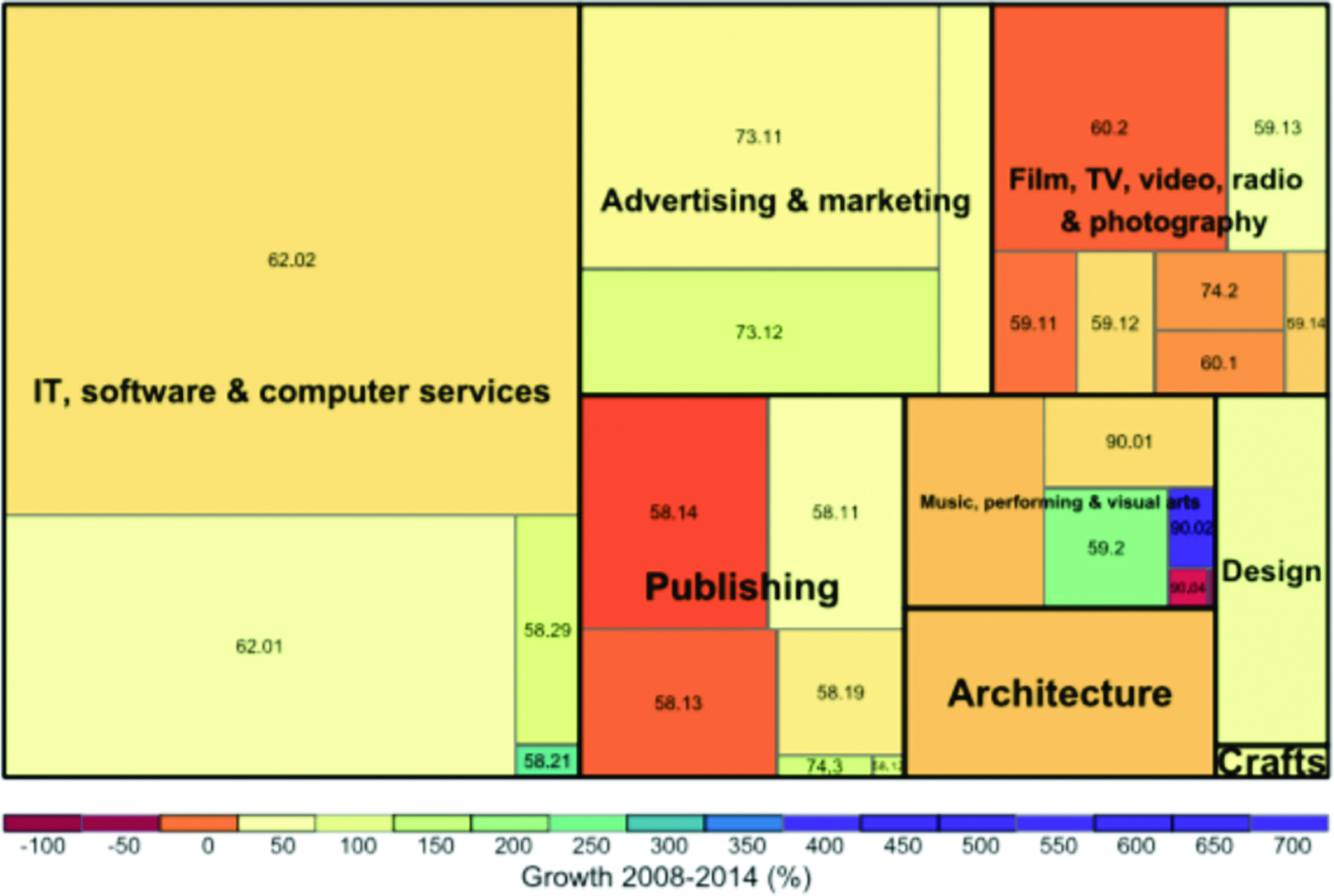

In order to find out which SIC codes the companies were using, I first analysed the SIC categories that would be available to them in a recent Department of Culture Media and Sport’s Creative Industries Economic Estimates.16 The report uses SIC data to compile a table demonstrating ‘growth’ in sectors of the creative industries between 2008 and 2014, and I include a copy of the graph in Figure 1.

Figure 1 presents a code for advertising and marketing and film and TV. The question I sought to answer is whether the ‘gross value added’ of the APA sector (the value of the goods and services) and the employment of the APA sector (payroll and freelance) were categorized as advertising or film. My research had shown that, geographically, the APA was clustered with advertising agencies and film and TV companies in central London in a format often characterized as an archetypal ‘creative cluster’ with a village-like community which hired and re-hired one another’s employees and exchanged ideas within a geographic social life.17

The advertising industry consists of four sectors in a value chain: distribution platforms, brands, agencies and producers. Distribution platforms include TV, Cinema, Radio, Outdoor, Digital and Press. Agencies and their teams have had to adapt their creative communication skills to the different platforms as they emerged. Brands, also termed clients, include all those corporations, such as Nike, Hovis and British Telecom, that commission and finance advertising content. The companies vary hugely in size. Larger brands have marketing departments headed by a marketing manager or director who takes charge of advertising. In 2020, over 3,000 brands were represented by the Incorporated Society of British Advertising (ISBA). Advertising agencies originate commercials content in the sense that creative teams (copy-writer and art director under the supervision of a creative director) generate text and images for audio-visual campaigns. The Institute of Practitioners in Advertising (IPA) represents the interests of these agencies and has over 300 members varying in size from multinationals, such as WPP, to smaller agencies, such as Mother. It is this sector which has received most attention in academic scholarship, notably in the historical work of Schwarzkopf, Nixon, Henry and Fletcher.18 Production companies are the fourth sector, and this sector developed in Britain as a response to the demand for specialist television content after ITV was launched in 1955.

The Screen Advertising Producers’ Association sits in a value chain, crafting and supplying digital content to the advertising agencies using skills and R&D developed largely in film and television. In the 1950s and 1960s, this industry, as documented by Russell and Taylor,19 recruited personnel from the British documentary and industrial film industries. Indeed, it was Mike Luckwell of production company HSFA Associates and Leon Clore, producer of public information films for such directors as Lindsay Anderson of Film Contracts, who originally helped to set up the AFPA (the precursor of the APA) as an adjunct of the British Film Producers’ Association (BFPA). Clore set up a production company called Film Contracts to secure his documentary and free cinema directors some advertising work.20 Specialist production and post-production companies emerged to meet this demand, and by the 1980s there existed a substantial network of independently owned production companies based in Soho, with institutionalized legal and financial arrangements for the production of commercials; these companies used camera houses, film laboratories and film studios which developed as suppliers for the film industry. The most comprehensive description of the emergence of the sector remains that of the production company owner James Garrett.21

In order to find out the screen advertising industry’s habits of SIC code reporting, I examined the codes used by the leading 16 production companies operating in advertising production in their most recent complete set of company returns lodged with Companies House. As micro-entities, some are exempt from having to submit a full set of returns. The criterion these companies had to meet in order to be selected was that they should be members of the APA and thus represent those directors recognized in the main awards-ceremonies for advertising in the UK. This criterion does not follow others, such as turnover or profits, used elsewhere to identify ‘leading’ companies. ‘Turnover’ as a criterion would have been possible using the company reports publicly available at Companies House, but it does not recognize the importance of factors other than economic size, such as peer acclaim, in holding competitive advantage22 in screen advertising production, nor the fact that ‘Small is Beautiful’23 has, since the late 1990s, blighted the expansionist phase of production in this sector. Many producers have resisted any cultural or economic pressure to expand or have their companies purchased by larger media companies.

The 2016 Creative Industries Economic Estimates report shows that the UK film and television industry does, indeed, offer production companies a range of SIC codes which enable them to identify some value chains. The block representing the Film, TV, Video and Radio industry states that the main codes under which this sector reports are 59.11 Film, Television, Video and Advertising Production,24 59.12 Film, Television and Video Post-Production,25 59.13 Film, Television and Video Distribution,26 59.14 Motion Picture Projection (Cinemas), 60.1 Radio,27 60.2 Television Broadcasting, Transmission & the BBC28 and 74.2 Film Processing, Film Copying (not motion picture), Motion Picture Developing.

So how did the companies report? Eight of the 16 companies reported under the codes that would allow them to be identified as sitting within the advertising value chain: Blink, MJZ and Rattling Stick submitted their company return under ‘Advertising Film Production’ (59111). Forever Pictures, Canada London, Riff Raff Films, Partizan and Pulse, however, submitted theirs under Advertising Video Production (59112). Half report under ‘film’ and half under ‘video’, despite the fact that neither originates on video nor film these days but on digital. By tradition, however, and prior to the adoption of high definition as the industry norm, TV commercials were shot on film, not on video tape; thus, the 59111 category would have been more accurate.

Five of the 16 companies (Somesuch, Academy, Riff Raff, Dark Energy, Pretty Bird) report under 82990 Other Business Support Service Activities Not Elsewhere Classified. Somesuch is a company headquartered in London and set up in 2010 by Sally Campbell (previously joint MD of Academy) in partnership with Tim Nash (previously video commissioner of Atlantic Records UK); it set up a US subsidiary in Los Angeles in 2017. Academy Films was founded in 1985 by Lizzie Gower, representing directors such as Jonathan Glazer, and, within its A2 division, FKA Twigs. One of the 16 companies, Ridley Scott Associates (RSA), reports under a combination of 59111, 59112 and 59120 (Motion Picture, Video and Television Programme Post-Production Activities). It is interesting that RSA alone submitted under a combination of codes. The majority of the 16 companies are diversified and, like RSA, operate in film, TV, advertising, music and film.

Two of the 16 companies (My Accomplice and HLA) reported a code normally associated with feature film and documentary production: 90030 Artistic Creation. This code is often used by micro-entity film production companies comprising owner / director / producers who purchase or originate scripts and formats. As well as ‘line producing’ films, feature companies such as Greenacre also ‘originate’ content and package and sell the scripts to other ‘line producers’ and broadcasters such as the BBC or Wall to Wall. These companies set up Single Purpose Vehicles (SPVs) for the production of individual dramas or feature films. In the past this led to the generation of alarming data for economists about short-lived and non-sustaining film production companies. Interestingly, one of the companies most intensively involved in the business of ‘origination’, Pulse, did not file under ‘90030 Artistic Creation’. A simple search of Pulse Films on the Companies House database renders a list of SPVs for the production of its films such as American Honey. SPVs are not set up for television commercials or music videos, the production of which will be run through the main ‘originating’ production company.

What does this investigation into SIC code reporting reveal? All 16 of the companies reported under film and television SIC codes. They did not file their returns under those SIC codes counted by the 2016 report as constituting ‘Advertising and Marketing’. This finding suggests that the economic activity of screen advertising producers is reported by government not as activity of the advertising industry but as activity of the film and television industry. That is despite the fact that most of its revenue accrues from contracts with advertising agencies to make commercials. The rationale for reporting under film and TV may be aspirational; this question would require ethnographic investigation into ‘production cultures’. The 2016 Estimates also show that advertising is represented as an entirely separate creative industry to film and television. Advertising commences with the digits 73, whereas film codes commence with the digits 59. Within the industry marked ‘Advertising and Marketing’, the Creative Industry report includes SIC codes 73.11 (Advertising Agencies & Related29) and SIC codes 73.12 (Media Representation30). This is significant. It raises the question of whether an industry such as the screen advertising industry has its GDP measured as part of the value chain for advertising or as part of the horizontally integrated film and television sector.

My research also shows that the SIC codes are blunt tools. Diversified production companies are elected to report under a single SIC code rather than a range of SIC codes which might identify the gross value added of their economic activity within each of the supply chains in which they operate. The SIC codes also have limited value in identifying value chains because so many codes are missing. Advertising fared better than fashion film, music video and games. Video games famously lack a SIC code. Neither fashion film nor music video has a code. The APA companies could report under ‘Advertising Film Production’ (59111) and ‘Advertising Video Production’ (59112).

Discussion

Since the first UK SIC in 1947, harmonized classifications have been a valuable way to generate comparable statistics from different government departments. The classification provides a framework for combining estimates from separate surveys in derived statistics such as the National Accounts. Given that SIC codes were originally created in the 1940s by nation-states as a tool to generate wealth and competitive advantage, how much use are they to government organizations wanting to measure productivity and innovation today?

Researchers such as Andy Pratt and Stuart Cunningham have identified significant problems with the SIC codes in conducting mapping research.31 Those problems have become more apparent recently. A major issue is that the codes need updating with new industries. For example, in the current programme of research that the BFI is undertaking with UK Interactive Entertainment (UKIE), the BFI is using an alternative methodology because there is no SIC code for video games. Researchers use web-scraping – counting any company website online that includes key words related to video production in the title. The web-scraping method was also used for NESTA’s Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre report in November 2020 identifying 709 ‘microclusters’ in the UK.32 The research – conducted by the Science Policy Research Unit at the University of Sussex – used survey data and novel web-scraping techniques to identify where the UK’s creative businesses were located and to what extent they were grouped together in ‘microclusters’. To create a map of the UK’s creative industries, researchers scraped data from the websites of 200,000 creative businesses, allowing them to pinpoint where organizations were based. This helped them to identify ‘clusters’ of creative firms within walking distance of each other. Even where an industry is well established, such as with ‘brand film’ – to some extent the twenty-first-century version of ‘industrial film’, there is an equal absence of codes. For his recent report on the Brand Film Industry, Steve Garvie uses not only data from the ONS which partly relies on SIC data but data from the Moving Image Directory and Televisual Corporate50.33

The second problem is that the codes need revisions in order to capture supply chains. Cunningham and Higgs have discussed extensively the challenges involved in modelling supply chains in the creative industries using SIC and SOC codes alone.34 My own analysis here shows that the SIC codes contain potential as a research method for scholars to identify some, if not all, value chains in British screen production. Currently, they cannot be used to identify and analyse horizontal and vertical integration or the value chains which cut across the screen industries. The codes ought to allow us to identify both the value chain within which a sector sits and the production industry: they ought to be able to reveal both the horizontally integrated industry within which a sector sits and its vertically integrated value chain. The existing codes do contain that potential: for example, ‘Advertising Film Production’ identifies production which sits in a different value chain to ‘Motion Picture Production’. A diversified producer can submit under a number of value chains. Clear guidance needs to be issued to producers such as Pulse and RSA, which are reporting for diversified companies operating in a number of value chains. RSA submits under 59111 ‘Motion Picture Production’. However, this does not capture the volume of turnover channelled through the distinctive advertising value chain and music video value chain produced by RSA. With codes for ‘games film production’ and ‘fashion film production’, this problem could be overcome. The BFI is currently working with UKIE on this issue.

The identification of supply chains could assist in the analysis of innovation and productivity in the screen industries.35 I have argued elsewhere that the music video and advertising sectors served as incubators for the development of telecine, post-production technologies, camera equipment and talent subsequently adopted in high-end television and film.36 The value of an R&D supply chain may not be apparent from its direct contribution to GDP but may only be apparent when mapped within a larger screen ecology which demonstrates the impact on GDP within another sector. In this way SIC codes could make a significant contribution to existing debates about sustainability, ownership, productivity, regional development, clustering and flexible labour in the study of British independent production.37 The need for greater understanding of the relationship between the sectors was suggested by Hill and McLoone’s important work on the connections between film and television.38 Craig and Cunningham (2019) have argued that the current ecology rests on a conflictual relationship between the old IP-led studios (NoCal) versus the new non-IP-led IT companies (SoCal). Craig and Cunningham cite 2006, when YouTube launched, as the date of the distinctive rupture between the old and the new, but there have been numerous periods in the twentieth century when ‘new media’ (whether platforms or technologies) have emerged through similar levels of conflict.

Any proposal to use SIC codes in future comes with a caveat. Work needs to be done to introduce consistency and accuracy by those reporting. But the data entry points also need to be tackled by the professional trade bodies in each of the screen industries. SIC data are collected from annual company returns. All public and private British companies are legally required to file their accounts at Companies House. As of 2016, all companies registered there had to do so with at least one SIC code. This means that companies themselves decide which SIC codes to report themselves under. In practice, it means that the decision is made by the company owners based on the advice of their freelance or company accountants. Micro-entities will hire freelancers or use specialist accountancy firms to prepare their reports. The accuracy of the SIC codes then depends on the production companies, many of whom currently choose to report under a single code for simplicity’s sake. When I raised the issue of inconsistent reporting with the CEO of the APA, Steve Davies, he was not aware of SIC codes or their use, despite the fact that it is the task of a professional association like the APA to lobby for the interests of a sector and undertake measures to improve diversity, productivity, regional spread and growth.

But as Smith and Jones show, making even minor changes in the UK’s SIC codes causes major upheavals in the collation of the national accounts39 such that the government is unlikely to urge the ONS to make further changes to the system. Changes in the classification in the UK have occurred about every 10–15 years.40 The most recent large changes in the UK’s classification were from SIC (80) to SIC (92) (in the mid-1990s) and then from SIC (2003) to SIC (2007). (The change from SIC (92) to SIC (2003) was not large and involved only minor changes at the most detailed level.)

Connecting the dots between different phases of British independent production would be a useful contribution to knowledge and understanding of the drivers of independent film and television production. This kind of historical analysis can only be conducted through interviews, archival research and ethnography, as used in the AHRC-funded British Music Video Project. The screen advertising production industry is part of Britain’s independent film production industry, and the reason for this is in part historical. The AFPA’s first member companies were subsidiaries and offshoots from the established documentary companies, because, like many of those documentary companies, they crafted ‘industrial films’ for corporations such as General Post Office (GPO Films) which retained the copyright and IP. Guild Television, an advertising production subsidiary of The Film Producers Guild, is one example. There were other connections: James Garrett, for instance, who had worked at British Transport Films and went on to launch one of the first leading commercials companies and has written about the process by which the sector became established. Amy Sargeant has also written on the links between television commercial production and GPO Films.41 A company called Wallace Productions was significantly involved in advertising as well as documentaries. Given these historic relations with documentary production, it might appear anomalous that the sector was put under the motion picture agreement by the trades unions. The production companies involved in screen commercials and music videos in the 1980s were the seedbeds and parents of many latterly influential independent film and television companies – not least Working Title and Kudos.42 Working Title began at a desk in the offices of music video production company Millaney Grant Mulcahy and Malet (MGMM) on Golden Square in London, one of the earliest, and almost certainly for a period the most powerful, of the music video production companies headquartered in London. Today, many of the production companies operating in film and television are diversified producers of content for a range of supply chains, from high-end TV drama to features, branded content, documentaries, fashion films and music videos.

Studio Lambert is a case in point. Founded in 1955 by Roger Lambert, the company was one of the earliest independent television commercials production companies. It was re-launched by Lambert’s son Stephen Lambert in 2008, and the company articulates this heritage as part of its brand value in 2020. Many of those early companies emerged from the independent documentary companies and producers specializing in ‘industrial film’. Thus, it would probably be sensible to start making connections with the significant scholarship on documentary production and industrial film.43 From a policy perspective, including the screen advertising industry in ‘the film and television industries’ could make a significant difference to research around the perceived lack of sustainability in the independent sector.44

The pattern of ‘diversification’, common to all the APA members, is relevant to the findings of the 2014 Northern Alliance report on the corporate finance of SMEs in the UK Film Industry45 and paints a more comprehensive picture of than has previously been evident of the Soho cluster of film and television production companies. Having a diversified portfolio across the value chains means that production companies are protected from recessions or other blockages in the funding of single value chains. Overheads received by production companies have traditionally formed a hugely important source for funding office rental, core front of house staff, business rates and other overheads. As indicated in my 2019 article, several of today’s leading film and television companies were incubated using overheads from the music video and advertising value chain.46

If SIC codes are to be of use to academics, they might help us to identify ‘less visible’ sectors such as these, which emerge in the course of archival and ethnographic research. Scholars have limited access to ‘industry’: when they encounter ‘industries’ or phenomena for study only as a result of their own personal encounters (watching the news, for example). While Herbert, Lotz and Punathambekar assert the importance of not imagining the ‘industry as a clean, self-evident sphere or as a bounded site for research’47 or a pre-given category,48 in practice these authors do not manage to develop a framework, either definitional or methodological, through which cultural constructions of industry can be made.

The Way Forward

The object of my analysis is not only to propose a methodology that can be used by governments, industry and scholars. The aim is also to stimulate critical debate about the ways in which nation-states define and measure industries. In his Introduction to the 2013 Focus on Media Industries Studies, Paul McDonald is keen to differentiate this area of work from studies of media and/or cultural economics (the former being more ‘critical’ than the latter). Media industry scholars still need a methodology for categorizing and referencing economic and industry activity, however. They need to treat secondary data with caution. To speculate on the basis of general impressions without reference to data is questionable. Part of a political economy of media involves understanding how and why nation-states attempt to collate industry data to leverage advantage in the competitive field. Wasko has collapsed media industry studies into ‘celebratory media economics’ on the one hand and critical ‘media political economy’ on the other,49 a distinction which we need to move beyond. As many scholars have observed, the media industries are structured internationally and operate as global corporations beyond the control of nation-states. Negus has illustrated this recently in relation to music, but it could equally be applied to the advertising industry.50 While the screen industries are not ‘boundaried nationally’, the policies of nation-states on screen industries have immediate consequences for issues of diversity, zero hours contracts and employment rights.

Ecology is the branch of biology that deals with the relations of organisms to one another and to their physical surroundings. The concept of ‘an ecology’ denotes the inability of organisms to survive alone. Peter Bloore has contributed some important modelling on the value chain in the independent feature film industry, addressing points raised previously by other scholars.51 Conceptualizing the screen industries as a non-geographic constellation of interlocked value chains enables us to explain how suppliers such as camera houses and post-production houses have not only remained trading but expanded and innovated at a time when the feature film industry was in recession in the 1980s. This conceptualization allows us to model the reliance of risk-averse sectors such as high-end television on risk-embracing production sectors for new and emerging media such as music video to deliver R&D.

Power politics underlie the exclusion of screen advertising, industrial film and music video from government data collection methods. Since 1955, the sector has been represented by the APA, set up in the year that ITV was launched to act as a buffer between the IPA (representing the agencies) and the Association of Cinematograph Technicians (ACT, later ACTT), which was the union representing Britain’s film crew. The ACT was very hostile to new commercial production52 but held the power to dictate how the production industry worked. When commercials launched, the ACT had two sections to their production agreement – one for features, which required 12 people to work on a film unit (four each in the production, camera and sound departments), and one for documentaries, which required only four people in total. After initially refusing to recognize the legitimacy of independent commercial production, the ACT eventually conceded. It deemed that commercial production should fall under the feature agreement, rather than the documentary one, because feature films were shot on 35 mm at the time while documentaries were photographed on 16 mm. In part because these industry models are unsuitable candidates for the ‘auteur paradigm’ approach to analysis, they have been placed lower down the unspoken hierarchy of screen arts in film and television studies.53 Industry classification studies and the historical power struggle to determine classification should be part of the terrain that we, as academics, study. Cunningham writes of ‘evolutionary economics’, and for us to really explore that, we need pre-2006 analyses.

Some might argue that the SIC codes are irrelevant, and that scholars should use their own independent methods for collecting data on the screen industries. These methods need to recognize that, as John Caldwell has pointed out, ‘industry is a mess’54 of complex ritualistic constellations and networks of activity, the essence or significance of which cannot be captured by attempts to categorize them into boundaried industries and value chains. However, collecting data by other methods is labour- and time-dependent. Given that there are arguments for reviewing the data on an annual basis in order to track growth, regional spread and diversity, there is a strong argument in favour of having a default methodology which is cost-effective and reliable. The SIC codes have much potential to meet these criteria.

But there is another important point here, about the value of SIC codes to academic scholars. It is that surely the codes themselves, and the industry organizations that create them, ought to form part of the subject of study rather than a research method. Classification codes created by political organizations affiliated to government are not value neutral. As Freedman has argued, ‘All too often, media policy research is viewed as not just a poor relative of more exciting media industries research but rather the boring next-door neighbor who spends too long at your house, convinced that he has lots of interesting things to say while everyone else makes polite excuses and tries to usher him out.’55

This article has not examined the political lobbying and power processes which have led to the exclusion of screen advertising from the DCMS functional definition of ‘the screen industries’, nor does it attend to the consequences for the micro businesses constituting the APA which have been excluded thus far. At the core of the endeavour I have proposed is the need for clarity around terms of analysis that we use. Is the APA community an ‘industry’ or a sector of an industry? Should we talk of the ‘screen production industries’ or ‘screen production industry’? A future model of how the screen production industries work should function as an explanatory model of how change occurs when new entrants to the market adopt new technologies or target new audiences. As Freedman says, ‘We need, therefore, to treat media policy a bit more like a production study, to investigate as Mayer et al. put it, “the complexity of routines and rituals, the routines of seemingly complex processes, the economic and political forces that shape roles, technologies, and the distribution of resources according to cultural and demographic differences.” Above all, we need to engage with questions of power in terms of the distribution of resources that are concentrated inside the media and the struggles for the redistribution of those resources’ (2014: 13, quoting Mayer et al. 2009: 4).56

Conclusion

In this article, I have tried to explore methodological and theoretical issues in the new paradigm of a screen ecology through a case-study analysis of the screen advertising industry. Without a comprehensive understanding of the history of this independent sector, it is not possible to understand the long-term growth strategies and actualities of the independent film and television sector in Britain post-war. Bringing Fashion Film, Branded Content, Medical Film, Education Film and so forth into our conception of the screen production industries would enable us to really appraise what drives demand, innovation, R&D, diversity and talent. For David Lee, ‘the independent television production sector’57 began in the early 1980s with the launch of Channel 4. Yet this is simply not true, as the existence of the early independent production companies for advertising such as Eyeline, James Garrett and Partners, N. Lee Lacy, and Studio Lambert demonstrate. The purpose for government of the data collected from SIC codes is to provide accurate, representative, reliable data which are sufficiently detailed in order to answer a range of questions about whether regional growth has taken place, productivity has fallen, an industry has strong export value, is diversified socially and what kinds of taxation, training and employment policies might boost growth.

In future, academics will need to study the kinds of power relationships that prevail within the production sectors of screen industries. While using SIC data presents methodological challenges, these are challenges that can be overcome; the result should afford a robust, repeatable methodology of considerable value to those interested in the historical documentation of how the characteristics of independent production change over time.

Notes

- Tom Harvey, Huffington Post. 09/11/2015 ⮭

- Craig, D., & Cunningham, S. (2019). Social media entertainment: The new intersection of Hollywood and Silicon Valley. New York University Press; Cunningham, S., & Flew, T. (Eds.). (2019). A research agenda for creative industries. Edward Elgar Publishing. ⮭

- Turnover of less than £632,000 and ten employees or fewer (Gov.uk 2020). A ‘small’ business by contrast has a turnover of £10.2 million and 50 employees or fewer (Gov. uk 2020). ⮭

- American Psychological Association. (2018). Private Communication with Steve Davies. CEO of APA. ⮭

- Lee, D. (2011). Networks, cultural capital and creative labour in the British independent television industry. Media, Culture and Society, 33(4), 549–565. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443711398693. ⮭

- Caston, E. (2019). The pioneers get shot: Music video, independent production and cultural hierarchy in Britain. Journal of British Cinema and Television, 16(4), 545–570. https://doi.org/10.3366/jbctv.2019.0498. ⮭

- Moore, I. (2014). Cultural and Creative Industries concept–a historical perspective. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 110, 738–746: 740. ⮭

- E.g. Econometrics, C. (2005). Economic Impact of the UK Screen Industries. a report to the UK Film Council, BFI 2015, Carey et al. 2017. ⮭

- E.g. Econometrics, ‘Economic Impact of the UK Screen Industries’, Economics, O. (2007). The economic impact of the UK film industry. Oxford Economics, Olsberg with Nordacity. (2015). Economic contribution of the UK’s high end film, of the UK’s film, high-end TV, video game, and animation programming sectors. ⮭

- Will Hutton & The Work Foundation, 2007. ⮭

- E.g 2004, 2010, 2015, DCMS. ⮭

- E.g. Bakhshi, H., Freeman, A., & Higgs, P. (2013). A dynamic mapping of the UK creative industries. ⮭

- Higgs, P., Cunningham, S., & Bakhshi, H. (2008). Beyond the creative industries: Mapping the creative economy in the United Kingdom; Higgs, P., & Cunningham, S. (2008). Creative industries mapping: Where have we come from and where are we going? Creative Industries Journal, 1(1), 7–30. https://doi.org/10.1386/cij.1.1.7_1; Higgs, P., & Cunningham, S. (2007). Australia’s creative economy: Mapping methodologies. ⮭

- Pratt, A. C. (2011). Microclustering of the media industries in London. In Media clusters. Edward Elgar Publishing, p. 7 ⮭

- Will Hutton & The Work Foundation, 2007. ⮭

- DCMS Creative Industries Economic Estimates, January 2016. ⮭

- Nachum, L., & Keeble, D. (1998). Business clustering and internationalisation of film production in central London. A report prepared for the Economic Enabling Unit of Westminster City Council; (1999). Neo-Marshallian nodes, global networks and firm competitiveness: The media cluster of central London. Economic and Social Research Council Centre for Business Research, Department of Applied Economics, University of Cambridge; (2000). Foreign and indigenous firms in the media cluster of central London, 2000. Economic and Social Research Council Centre for Business Research; (2003). MNE linkages and localised clusters: Foreign and indigenous firms in the media cluster of Central London. Journal of International Management, 9(2), 171–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1075-4253(03)00007-3; Rocks, C. (2017). London’s creative industries. GLA economics. Rogers, Everett M. Diffusion of innovations. Simon & Schuster; Chapain, C., & Stachowiak, K. (2017). Innovation dynamic in the film industry: The case of the Soho cluster in London. In Creative industries in Europe (pp. 65–94). Springer; Chapain, C., Cooke, P., De Propris, L., MacNeill, S., & Mateos-Garcia, J. Creative clusters and innovation. Putting creativity on the map. National Endowment for Science Technology and the Arts. (2010); Nixon, S. (2013). Advertising executives as modern men Buy this book: Studies in advertising and consumption, 103. ⮭

- Schwarzkopf, S. (2005). They do it with mirrors: Advertising and British Cold War consumer politics. Contemporary British History, 19(2), 133–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/13619460500080199; Schwarzkopf, S. (2011). The subsiding sizzle of advertising history. Journal of Historical Research in Marketing, 3(4), 528–548. https://doi.org/10.1108/17557501111183653, Schwarzkopf, S. (2009). What was advertising? The invention, rise, demise, and disappearance of advertising concepts in nineteenth-and twentieth-century Europe and America. Business and Economic History On-Line, 7, Schwarzkopf, S. (2008a). Creativity, capital and tacit knowledge: The Crawford agency and British advertising in the interwar years. Journal of Cultural Economy, 1(2), 181–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350802243594, Schwarzkopf, S. (2007). Transatlantic invasions or common culture? Modes of cultural and economic exchange between the American and the British advertising industries, 1945–2000. In Anglo-American media interactions, 1850–2000 (pp. 254–274). Palgrave Macmillan, Schwarzkopf, S. (2008b). “Turning trade marks into brands: How advertising agencies created brands in the global market place, 1900–1930.” Centre for Globalization Research Working Paper 18, Schwarzkopf, S. (2015). Marketing history from below: Towards a paradigm shift in marketing historical research. Journal of Historical Research in Marketing, 7(3), 295–309. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHRM-06-2015-0021; Nixon, S. (1996). Hard Looks: Masculinities, Spectatorship & Contemporary Consumption. UCL Press, Nixon, S. (2003). Advertising Cultures: Gender, Commerce, Creativity. Sage Publications., Nixon, S. (2010). ‘Salesmen of the Will to Want’: Advertising and its critics in Britain 1951–67. Contemporary British History, 24(2), 213–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/13619461003768306, Nixon, S. (2016). Hard sell: Advertising, affluence and transatlantic relations, c. 1951–69. Manchester University Press; Henry, B. (Ed.). (1986). British television advertising: The first 30 years. Vintage Book Company; Fletcher, W. (2008). Powers of persuasion: The inside story of British advertising 1951–2000. Oxford University Press. ⮭

- Russell, Patrick, and James Piers Taylor (Eds). (2010). Shadows of Progress: Documentary Film in Post-War Britain. BFI Publishing. ⮭

- APA, 2018. ⮭

- Garrett, 1986. ⮭

- Porter, M. E. (1998). Clusters and the new economics of competition. In Harvard Business Review, 76(6), 77–90. ⮭

- Schumacher, E. F. (2011). Small is beautiful: A study of economics as if people mattered. Random House. ⮭

- Film Production for Projection or Broadcasting and Film Studios, Motion Picture Production, Film Producer (own account), Production of Theatrical and Non-Theatrical Television Programmes, Television Programme Production Activities, Television Studio, Training Film Production, Training Video Production, Video Production, Video Producer (own account), Video Studios, Advertising Film Production, Advertising Video Production. ⮭

- Film Processing Activities Inc. Soundtrack dubbing & synchronisation, Film cutting, Film Editing, Motion Picture Film Laboratory Activities, Motion Picture Post Production Activities, Post Production Film Activities, Photographic Film Processing Activities (for the motion picture industry), Television Post-Production, Video Post Production Activities. ⮭

- Film Rental, Film Broker, Film Hiring Agency, Film Library, Motion Picture Distribution Activities, Motion Picture Distribution Rights Acquisition, Television Distribution Rights Acquisition, Television Programme Distribution Activities, Video Tape and DVD Distribution Rights Acquisition, Video Tapes Distribution to Other Industries. ⮭

- British Broadcasting Corporation (Radio), Data Broadcasting (integrated with Radio), Independent Broadcasting Authority (Radio), Internet Radio Broadcasting, Local Radio Station (Broadcasting), Radio Broadcasting Station, Radio Programme Transmission, Radio Station, Radio Studio, Transmission of aural programming via over-the-air broadcasts, cable or satellite. ⮭

- British Broadcasting Corporation (Television), Data Broadcasting (integrated with Television), Recording Studio (Television), Television Broadcasting Station, Television channel programme creation from purchased and/or self-produced programme components, Television Programmes Transmission, Television Service, Television Relay, Image with Sound Internet Broadcasting. ⮭

- Poster Advertising, Showroom Design, Signwriting, Window Dressing, Advertising Campaign Creation and Realisation, Advertising Contractor, Advertising Consultant, Advertising material or samples delivery or distribution, Aerial and Outdoor Advertising Services, Bill Posting Agency, Bus carding, Commercial Artist, Copywriter, Creating and Placing Advertising, Creation of stands and other display structures and sites, Marketing Campaigns. ⮭

- Advertising Space or Time (Sales or leasing thereof), Media Representation. ⮭

- Pratt, ‘Microclustering of the media industries in London’; Higgs & Cunningham, Australia’s creative economy. ⮭

- Siepel, J., Roberto, C., Monida, M., Jorge, V.-O., Patrizia, C., & Bloom, M. (November 19 2020). Creative Radar: Mapping the UK’s creative industries. National Endowment for Science Technology and the Arts. ⮭

- Garvie, S. Moving image. The Brand Film Industry Report: Revealing the Hidden Sector, 2020, pp. 28–29. ⮭

- Higgs & Cunningham, Australia’s creative economy. ⮭

- Watson, G. (2004). Uncertainty and contractual hazard in the film industry: Managing adversarial collaboration with dominant suppliers. Supply Chain Management, 9(5), 402–409. https://doi.org/10.1108/13598540410560784. ⮭

- Caston, ‘The pioneers get shot’; Caston, E. (2020). British music videos. Art genre and authenticity 1966–2016. Edinburgh University Press. ⮭

- For an outline of some of these key issues, see Doyle, G., & Paterson, R. (2008). Public Policy and Independent Television Production In the U. K. Journal of Media Business Studies, 5(3), 17–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/16522354.2008.11073473, Doyle, G., Paterson, R., & Barr, K. Television production in transition: Independence, scale, sustainability and the digital challenge. Springer. Nature Publishing. (2021), Pratt, A. C., & Gornostaeva, G. The governance of innovation in the film and television industry: A case study of London, UK. Creativity, innovation and the cultural economy. (2009): 119–136, Lee, Independent television production in the UK. ⮭

- Hill, J., & McLoone, M. (Eds.) (1996). Big picture small screen: The relations between film and television. University of Luton Press/John Libbey Media. ⮭

- Smith, P. A., & James, G. G. (2017). Changing industrial classification to SIC (2007) at the UK Office for National Statistics. Journal of Official Statistics, 33(1), 223–247. https://doi.org/10.1515/jos-2017-0012. ⮭

- See Smith, P., & Penneck, S. (2009). 100 years of the Census of Production in the UK. Office for National Statistics, for an overview of industrial classifications used in UK statistics since 1907. ⮭

- Sargeant, A. (2012). GPO Films: American and European models of Advertising in the Projection of Nation. Twentieth Century British History, 23(1), 38–56. https://doi.org/10.1093/tcbh/hwr065. ⮭

- Caston, ‘The pioneers get shot’; 2020. ⮭

- E.g. Chapman, J. (2015). A new history of British documentary. Palgrave Macmillan, Russell & Taylor 2010, Swann, P., & Paul, S. (1989). The British documentary film movement, 1926–1946. Cambridge University Press, Sargeant, ‘GPO Films’. ⮭

- Davenport, J. (2006). UK film companies: Project-based organizations lacking entrepreneurship and innovativeness? Creativity and Innovation Management, 15(3), 250–257. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8691.2006.00394.x, Deakin, S., & Pratten, S. (1999). Competitiveness policy and economic organisation: The case of the British film industry (No. wp127). Economic and Social Research Council Centre for Business Research, and Deakin, S., & Pratten, S. (2000). Quasi markets, transaction costs, and trust: The uncertain effects of market reforms in British television production. Television and New Media, 1(3), 321–354. https://doi.org/10.1177/152747640000100305. ⮭

- Northern Alliance. (2014). The corporate finance of SMEs in the UK film industry: A report for the British Film Institute. October. ⮭

- Caston, ‘The pioneers get shot’. ⮭

- Caldwell, J. T. (2013). Para-industry: Researching Hollywood’s Blackwaters. Cinema Journal, 52(3), 157–165. https://doi.org/10.1353/cj.2013.0014, p. 157. ⮭

- Govil, N. (2013). Recognizing ‘Industry’. Cinema Journal. Grainge, 52(3), 172–176. https://doi.org/10.1353/cj.2013.0019 ⮭

- Wasko, J. (2013). Hollywood in the information age: Beyond the silver screen. John Wiley & Sons. ⮭

- Negus, K. (2019). Nation-states, transnational corporations and cosmopolitans in the global popular music economy. Global Media and China, 4(4), 403–418. https://doi.org/10.1177/2059436419867738; Negus, K. (2019). From creator to data: The post-record music industry and the digital conglomerates. Media, Culture and Society, 41(3), 367–384. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443718799395 ⮭

- Bloore, P. Re-defining the Independent Film Value Chain;[Online] UK Film Council, London (published February 2009), Hearn, G., Roodhouse, S., & Blakey, J. (2007). From value chain to value creating ecology: Implications for creative industries development policy. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 13(4), 419–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/10286630701683367, Abadie, F., Friedewald, M., & Weber, K. M. (2010). Adaptive foresight in the creative content industries: Anticipating value chain transformations and need for policy action. Science and Public Policy, 37(1), 19–30. https://doi.org/10.3152/030234210X484793; Finney, A. (2014). Value chain restructuring in the film industry: The case of the independent feature film sector. In International perspectives on business innovation and disruption in the creative industries. Edward Elgar Publishing; Watson, ‘Uncertainty and contractual hazard in the film industry’. ⮭

- Garrett, 1986. ⮭

- Caston, ‘The pioneers get shot’. Hill, J. (2004). UK film policy, cultural capital and social exclusion. Cultural Trends. Will. “Staying ahead: the economic performance of the UK? s creative industries.”, 13(2), 29–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/0954896042000267134. ⮭

- Caldwell, ‘Para-industry’: 163 ⮭

- Freedman, 2011: 14. ⮭

- Freedman, 2011. ⮭

- Lee, ‘Networks, cultural capital and creative labour’. ⮭

Bibliography

Abadie, F., Friedewald, M., & Weber, K. M. (2010). Adaptive foresight in the creative content industries: Anticipating value chain transformations and need for policy action. Science and Public Policy, 37(1), 19–30. https://doi.org/10.3152/030234210X484793https://doi.org/10.3152/030234210X484793

Albert, A., & Reid, B. (2011). The contribution of the advertising industry to the UK economy: A creative industries report. Work Foundation.

Finney, A. (2014). Value chain restructuring in the film industry: The case of the independent feature film sector. In International perspectives on business innovation and disruption in the creative industries. Edward Elgar Publishing.

American Psychological Association. (2018). Private Communication with Steve Davies. CEO of APA.

Bakhshi, H., Freeman, A., & Higgs, P. (2013). A dynamic mapping of the UK creative industries.

Bloore, P. Re-defining the Independent Film Value Chain;[Online] UK Film Council, London (published February 2009). (2009).

British Film Institute. (2015). The economic contribution of the UK’s film. High-End, TV, Video Games and Animation Programme Sectors,

Crowley, L., Dudley, C., Sheldon, H., & Giles, L. (2017). A skills audit of the UK film and screen industries: Report for the British Film Institute. Work Foundation.

Caldwell, J. T. (2013). Para-industry: Researching Hollywood’s Blackwaters. Cinema Journal, 52(3), 157–165. https://doi.org/10.1353/cj.2013.0014https://doi.org/10.1353/cj.2013.0014

Caston, E. (2019). The pioneers get shot: Music video, independent production and cultural hierarchy in Britain. Journal of British Cinema and Television, 16(4), 545–570. https://doi.org/10.3366/jbctv.2019.0498https://doi.org/10.3366/jbctv.2019.0498

Caston, E. (2020). British music videos. Art genre and authenticity 1966–2016. Edinburgh University Press.

Chapain, C., & Stachowiak, K. (2017). Innovation dynamic in the film industry: The case of the Soho cluster in London. In Creative industries in Europe (pp. 65–94). Springer.

Chapain, C., Cooke, P., De Propris, L., MacNeill, S., & Mateos-Garcia, J. Creative clusters and innovation. Putting creativity on the map. National Endowment for Science Technology and the Arts. (2010).

Chapman, J. (2015). A new history of British documentary. Palgrave Macmillan.

Craig, D., & Cunningham, S.. (2019). Social media entertainment: The new intersection of Hollywood and Silicon Valley. New York University Press

Cunningham, S., & Flew, T. (Eds.). (2019). A research agenda for creative industries. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Davenport, J. (2006). UK film companies: Project-based organizations lacking entrepreneurship and innovativeness? Creativity and Innovation Management, 15(3), 250–257. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8691.2006.00394.xhttps://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8691.2006.00394.x

Daws, L. B. (2009). Media monopoly: Understanding vertical and horizontal integration. Communication Teacher, 23(4), 148–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/17404620903218783https://doi.org/10.1080/17404620903218783

DCMS. (2006). Access to finance and business support [Report]. http://www.cep.culture.gov.o.uk Retrievedhttp://www.cep.culture.gov.o.uk 29/11/2007

DCMS creative industries economic estimates. (January 2015). Statistical release date: 13/01/2015 (ALSO 2004, 2010).

DCMS creative industries economic estimates. (January 2016).

De Propris, L. (2005). Mapping local production systems in the UK: Methodology and application. Regional Studies, 39(2), 197–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/003434005200059983https://doi.org/10.1080/003434005200059983

Deakin, S., & Pratten, S. (1999). Competitiveness policy and economic organisation: The case of the British film industry (No. wp127). Economic and Social Research Council Centre for Business Research, and

Deakin, S., & Pratten, S. (2000). Quasi markets, transaction costs, and trust: The uncertain effects of market reforms in British television production. Television and New Media, 1(3), 321–354. https://doi.org/10.1177/152747640000100305https://doi.org/10.1177/152747640000100305

Doyle, G., Paterson, R., & Barr, K. Television production in transition: Independence, scale, sustainability and the digital challenge. Springer. Nature Publishing. (2021).

Doyle, G., & Paterson, R. (2008). Public Policy and Independent Television Production In the U. K. Journal of Media Business Studies, 5(3), 17–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/16522354.2008.11073473https://doi.org/10.1080/16522354.2008.11073473

Econometrics, C. (2005). Economic Impact of the UK Screen Industries. a report to the UK Film Council.

Economics, O. (2007). The economic impact of the UK film industry. Oxford Economics.

Ellis, J. (2004). British? Cinema? Television? What on Earth Are We Talking About? Journal of British Cinema and Television, 1(1), 21–26. https://doi.org/10.3366/JBCTV.2004.1.1.21https://doi.org/10.3366/JBCTV.2004.1.1.21

Ellis, J. Interstitials: How the “bits in between” define the programmes. Ephemeral media: Transitory screen culture from television to YouTube. (2011): 59–69.

Fletcher, W. (2008). Powers of persuasion: The inside story of British advertising 1951–2000. Oxford University Press.

Freedman, D. (2014). Media policy research and the media industries Media Industries Journal 1, 1(1), 11–15. https://doi.org/10.3998/mij.15031809.0001.103https://doi.org/10.3998/mij.15031809.0001.103

Fu, W. W. (2009). Screen survival of movies at competitive theaters: Vertical and horizontal integration in a spatially differentiated market. Journal of Media Economics, 22(2), 59–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/08997760902900072https://doi.org/10.1080/08997760902900072

Garrett, J. In Henry. (1986)

Garvie, S. Moving image. The Brand Film Industry Report: Revealing the Hidden Sector, 2020 p.p. 28–29.

Govil, N. (2013). Recognizing “Industry”. Cinema Journal. Grainge, 52(3)(3), 172–176. https://doi.org/10.1353/cj.2013.0019https://doi.org/10.1353/cj.2013.0019, and

Johnson, C. (2015). Promotional screen industries. Routledge, Jonathan. (2010). Show sold separately: Promos, spoilers, and other media paratexts. New York University Press.

Hardy, J. Commentary: Branded content and media-marketing convergence. The Political Economy of Communication 5, no. 1. (2017).

Harvey, T. (09/11/2015) 08:23 GMT | Updated 06/11/2016 05:12. The creative future for Soho— Manifesto for growth. Huffington Post. Accessed June 28 2021.

Hearn, G., Roodhouse, S., Blakey, J. (2007). From value chain to value creating ecology: Implications for creative industries development policy. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 13(4), 419–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/10286630701683367https://doi.org/10.1080/10286630701683367

Henry, B. (Ed.). (1986). British television advertising: The first 30 years. Vintage Book Company

Higgs, P., Cunningham, S., Bakhshi, H. Beyond the creative industries: Mapping the creative economy in the United Kingdom. (2008).

Higgs, P., Cunningham, S. (2008). Creative industries mapping: Where have we come from and where are we going? Creative Industries Journal, 1(1), 7–30. https://doi.org/10.1386/cij.1.1.7_1https://doi.org/10.1386/cij.1.1.7_1

Higgs, P., Cunningham, S. Australia’s creative economy: Mapping methodologies. (2007).

Hill, J., McLoone, M. (Eds.) n.d. Big picture small screen: The relations between film and television. University of Luton Press/John Libbey Media.

Hill, J. (2004). UK film policy, cultural capital and social exclusion. Cultural Trends. Will. “Staying ahead: the economic performance of the UK? s creative industries.”, 13(2), 29–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/0954896042000267134https://doi.org/10.1080/0954896042000267134

Jin, D. Y. (2012). Transforming the global film industries: Horizontal integration and vertical concentration amid neoliberal globalization. International Communication Gazette, 74(5), 405–422. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048512445149https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048512445149

Lambert, S. (1982). Channel 4: Television with a difference? British Film Institute.

Lee, D. (2011). Networks, cultural capital and creative labour in the British independent television industry. Media, Culture and Society, 33(4), 549–565. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443711398693https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443711398693

Lee, D. (2018). Independent television production in the UK: From cottage industry to big business. Springer.

Mateos-Garcia, J., Hasan, B. (ND). The geography of Creativity in the UK: Creative clusters, creative people and creative networks.

Mayer, Vicki, Banks, Miranda, and Caldwell, John Thornton. (2009). “Introduction: Production Studies: Roots and Routes,” in Production Studies: Cultural Studies of Media Industries, eds. Mayer Vicki, Banks Miranda, and Caldwell John Thornton. New York: Routledge, 1–12.

McDonald, P. (2013). : Introduction. Cinema Journal, 52(3), 145–149. https://doi.org/10.1353/cj.2013.0025https://doi.org/10.1353/cj.2013.0025

Moore, I. (2014). Cultural and Creative Industries concept–a historical perspective. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 110, 738–746: 740.

Nachum, L., Keeble, D. (1998). Business clustering and internationalisation of film production in central London. A report prepared for the Economic Enabling Unit of Westminster City Council.

Nachum, L., Keeble, D. (2003). MNE linkages and localised clusters: Foreign and indigenous firms in the media cluster of Central London. Journal of International Management, 9(2), 171–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1075-4253(03)00007-3https://doi.org/10.1016/S1075-4253(03)00007-3

Nachum, L., Keeble, D. (1999). Neo-Marshallian nodes, global networks and firm competitiveness: The media cluster of central London. Economic and Social Research Council Centre for Business Research, Department of Applied Economics, University of Cambridge.

Nachum, L., Keeble, D. (2000). Foreign and indigenous firms in the media cluster of central London, 2000. Economic and Social Research Council Centre for Business Research.

National Endowment for Science Technology and the Arts. (2017). RnD in the creative industries [Blog].

Nixon, S. (1996). Hard Looks: Masculinities, Spectatorship Contemporary Consumption. UCL Press.

Nixon, S. (2003). Advertising Cultures: Gender, Commerce, Creativity. Sage Publications.

Nixon, S. (2010). ‘Salesmen of the Will to Want’: Advertising and its critics in Britain 1951–67. Contemporary British History, 24(2), 213–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/13619461003768306https://doi.org/10.1080/13619461003768306

Nixon, S. (2013). Advertising executives as modern men Buy this book: Studies in advertising and consumption, 103.

Nixon, S. (2016). Hard sell: Advertising, affluence and transatlantic relations, c. 1951–69. Manchester University Press.

Alliance, Northern. (2014). The corporate finance of SMEs in the UK film industry: A report for the British Film Institute. October.

Olsberg with Nordacity. (2015). Economic contribution of the UK’s high end film, of the UK’s film, high-end TV, video game, and animation programming sectors.

Orlebar. The TV ad and its afterlife in Powell, Helen. Promotional culture and convergence: Markets, methods, media. Routledge. (2013).

Oxera. (2017). Impacts of leaving the EU on the Uk Screen Sector. Prepared for the Screen Sector Task Force.

Porter, M. E. (1998). Clusters and the new economics of competition. In Harvard Business Review, 76(6), 77–90. (download via Athens).

Pratt, A. C. (2011). Microclustering of the media industries in London. In Media clusters. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Pratt, A. C., Gornostaeva, G. The governance of innovation in the film and television industry: A case study of London, UK. Creativity, innovation and the cultural economy. (2009): 119–136.

Pratten, S., Deakin, S. (2000). Competitiveness policy and economic organization: The case of the British film industry. Screen, 41(2), 217–237. https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/41.2.217https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/41.2.217

Rocks, C. (2017). London’s creative industries. GLA economics.

Rogers, Everett M. Diffusion of innovations. Simon Schuster

Russell, Patrick, and Taylor, James Piers (Eds). (2010). Shadows of Progress: Documentary Film in Post-War Britain. BFI Publishing.

Sargeant, A. (2012). GPO Films: American and European models of Advertising in the Projection of Nation. Twentieth Century British History, 23(1), 38–56. https://doi.org/10.1093/tcbh/hwr065https://doi.org/10.1093/tcbh/hwr065

Saundry, R. (1998). The limits of flexibility: The case of UK television. British Journal of Management, 9(2), 151–162. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.00080https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.00080

Schumacher, E. F. (2011). Small is beautiful: A study of economics as if people mattered. Random House.

Schwarzkopf, S. (2005). They do it with mirrors: Advertising and British Cold War consumer politics. Contemporary British History, 19(2), 133–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/13619460500080199https://doi.org/10.1080/13619460500080199

Schwarzkopf, S. (2007). Transatlantic invasions or common culture? Modes of cultural and economic exchange between the American and the British advertising industries, 1945–2000. In Anglo-American media interactions, 1850–2000 (pp. 254–274). Palgrave Macmillan.

Schwarzkopf, S. (2008a). Creativity, capital and tacit knowledge: The Crawford agency and British advertising in the interwar years. Journal of Cultural Economy, 1(2), 181–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350802243594https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350802243594

Schwarzkopf, S. (2008b). “Turning trade marks into brands: How advertising agencies created brands in the global market place, 1900–1930.” Centre for Globalization Research Working Paper 18.

Schwarzkopf, S. (2009). What was advertising? The invention, rise, demise, and disappearance of advertising concepts in nineteenth-and twentieth-century Europe and America. Business and Economic History On-Line, 7.

Schwarzkopf, S. (2011). The subsiding sizzle of advertising history. Journal of Historical Research in Marketing, 3(4), 528–548. https://doi.org/10.1108/17557501111183653https://doi.org/10.1108/17557501111183653

Schwarzkopf, S. (2015). Marketing history from below: Towards a paradigm shift in marketing historical research. Journal of Historical Research in Marketing, 7(3), 295–309. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHRM-06-2015-0021https://doi.org/10.1108/JHRM-06-2015-0021

Siepel, J., Roberto, C., Monida, M., Jorge, V.-O., Patrizia, C., Bloom, M. (November 19 2020). Creative Radar: Mapping the UK’s creative industries. National Endowment for Science Technology and the Arts.

Smith, P. A., James, G. G. (2017). Changing industrial classification to SIC (2007) at the UK Office for National Statistics. Journal of Official Statistics, 33(1), 223–247. https://doi.org/10.1515/jos-2017-0012https://doi.org/10.1515/jos-2017-0012

Smith, P., Penneck, S. (2009). 100 years of the Census of Production in the UK. Office for National Statistics, 1

Starkey, K., Barnatt, C. (1997). Flexible specialization and the reconfiguration of television production in the UK. Technology Analysis and Strategic Management, 9(3), 271–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537329708524284https://doi.org/10.1080/09537329708524284

Starkey, K., Barnatt, C., Tempest, S. (2000). Beyond networks and hierarchies: Latent organizations in the UK television industry. Organization Science, 11(3), 299–305. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.11.3.299.12500https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.11.3.299.12500

Street, S.. “‘Another Medium Entirely’: Esther Harris. National screen service and film trailers in Britain, 1940–1960.” Historical Journal of Film. Radio and Television 29, no. 4. (2009): 433–448.

Swann, P., Paul, S. (1989). The British documentary film movement, 1926–1946. Cambridge University Press.

Tempest, S., Starkey, K., Barnatt, C. Diversity or divide? In search of flexible specialization in the UK television industry.” Industrielle Beziehungen/The German Journal of Industrial Relations. (1997): 38–57.

The Contribution of the Advertising Industry to the UK Economy A Creative Industries report Conducted on behalf of Credos. (November 2011). Prepared by Alexandra Albert and Dr Benjamin Reid.

UK Film Council. (2003). Post production in the UK.

Watson, G. (2004). Uncertainty and contractual hazard in the film industry: Managing adversarial collaboration with dominant suppliers. Supply Chain Management, 9(5), 402–409. https://doi.org/10.1108/13598540410560784https://doi.org/10.1108/13598540410560784

Work Foundation. (2007). Staying ahead: The economic performance of the UK’s creative industries. http://www.cep.culture.gov.uk Retrieved 29/11/2007http://www.cep.culture.gov.uk

Wasko, J. (2013). Hollywood in the information age: Beyond the silver screen. John Wiley Sons.

Negus, K. (2019). Nation-states, transnational corporations and cosmopolitans in the global popular music economy. Global Media and China, 4(4), 403–418. https://doi.org/10.1177/2059436419867738https://doi.org/10.1177/2059436419867738

Negus, K. (2019). From creator to data: The post-record music industry and the digital conglomerates. Media, Culture and Society, 41(3), 367–384. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443718799395https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443718799395