Introduction

From the cooperative extension service at public land grant institutions to the vision and values statements of private liberal arts institutions, and the mission of community colleges, engagement with communities beyond the walls of the academy are notable values of higher education. Service-learning, and community-based research (CBR) are important tools for institutions of higher learning to bridge town-gown divides, enhance student learning, and make a case for the value of higher education. While these values of community engagement have deep roots, the 21st century has seen significant growth in the deliberate articulation and promotion of community integration into classroom activities and research. This growth can be seen in the inclusion of service-learning as a “high impact practice” by the American Association of Colleges & Universities (Kuh, 2008) and the growth of organizations like Campus Compact, which launched with three founding institutions in 1985 and now has state and regional affiliates serving and organizing hundreds of institutions (Campus Compact, 2022). Stated values from CBR and service-learning scholars include reciprocity and mutual benefit (Israel et al., 1998; Maiter et al., 2008). Simultaneously, the open access movement in scholarly communication has worked to open previously paywalled scholarship to all interested readers. The open access movement has its roots in the removal of barriers, particularly subscription barriers to access research. This helps combat unsustainable journal pricing while satisfying funder mandates to openly publish funded research for the benefit of the funder and the public or broader community it serves (BOAI, 2002; Larivière et al., 2015). The mutual benefit and reciprocity values of CBR and the public benefit of open access research seem well aligned. Our research seeks to determine if the definition of reciprocity has come to include open access publishing by CBR journals by giving access to published scholarship to the communities who helped produce it. We will further explore how these scholarly publishing practices do or do not meet the needs of scholars as they build their careers in academic research institutions. Finally, we will make recommendations on leveraging the knowledge and tools of both movements to further advance the value each.

Key Definitions and Concepts

Over the years a range of vocabulary and jargon has grown to describe work that ties the teaching and research goals of the academy to their communities. While each term has its own purpose and nuance, not all town-gown relations are in scope for this paper. Likewise, open research principles are far-reaching in its aims and formats. Our emphasis will be on the following:

Community-Based Research (CBR)

As defined by Strand et al. (2003) in Community-Based Research in Higher Education “CBR is a partnership of students, faculty, and community members who collaboratively engage in research with the purpose of solving a pressing community problem or effecting social change” (p. 3). Of all the forms of working beyond the boundaries of campus, CBR taps directly into the research mission of colleges and universities, naturally raising questions about how these research findings are published and who has access. Some publications, institutions, and research methodology guides use the terms Community Engaged Research, Community Based Participatory Research, or Community Based Qualitative Research. These modifiers each seek to emphasize the inclusive and active nature of research with the community. For our purposes, we will discuss CBR as inclusive of these variants.

Service-Learning and Extension Service

Service-learning is “a form of experiential education in which students engage in activities that address human and community needs, together with structured opportunities for reflection designed to achieve learning outcomes.” (Jacoby & Howard, 2014, p. 2). The value of reciprocity – that students and community partners find mutual benefit in the interaction – is deeply emphasized in service-learning. On the campus side of the hyphen, service-learning is more deeply rooted in student learning than the pursuit of research. Even so, the reflection piece results in written student outputs suitable for publication, and for the scholarship of teaching and learning; service-learning provides a rich opportunity to study the pedagogical and community benefits of the practice. For this reason, there are scholarly publications outlets with a service-learning focus and we have chosen to include those in our scope of review, and given the shared value of balancing community and academic needs with benefit for all.

Cooperative Extension Service

Established by the Smith-Lever Act (1914), public land grant universities have established cooperative extension services to use the knowledge built by the academy to support their communities (7 U.S.C. 341 § 1). While restricted to universities with these programs, there are journals dedicated to extension service work and are in scope for this review.

Open Access Publishing

Open access (OA) is a complex and ever-changing area of scholarly communications with a clear goal: making information openly available and accessible. Open access publishing arose in response to subscription-based models of scholarly publication, most notably with journal articles. For many years, increases in subscription rates have outpaced inflation, resulting in unsustainable subscription pricing in order to access paywalled content, and leaving institutions or individuals who cannot afford subscriptions without access to needed scholarly literature (Larivière et al., 2015). Many models of open access publication have emerged as an alternative to the subscription-based model of access, all of which provide an alternative structure of financial support for journals other than the traditional subscription-based model.

Today, for-profit publishers see some open access models as a promising revenue stream to supplement subscription revenues (Butler et al., 2022). For example, Elsevier’s parent company, RELX, noted in its 2022 annual report that “pay-to-publish open access articles [are] growing particularly strongly” (2023.). Initiatives like OA2020, paired with a rise in library subscription cancellations, mean that open access funding is increasingly important to publishers in order to maintain or increase revenues (n.d.). However, the sustainability of different open access models is a growing concern for those who financially support open access publishing, including libraries and research funders (Willinsky & Rusk, 2019). Publishing is not free (though it does rely on unpaid labor and contributions), and as a result, open access publications must be supported financially. Financial and sustainability issues have forced many independent journal publications to sign deals with for-profit publishers, who manage and financially support the reviewing, editing, publishing, indexing, and marketing on behalf of the journal (Fyfe et al., 2017). However, this support comes at the expense of control: in open access terms, this often means that the journal cannot always freely decide on how to make its content open access, if it is an option offered by the publisher at all (Clarke, 2020).

Different open access publication models are often described with color terminology, though these terms are not always straightforward. For the purposes of this research, the publications studied fell into three primary categories. The first is diamond, also called platinum, which designates a journal where all articles are openly available, and the author does not pay any fees for publication. These journals are funded through other means – for many university presses, these costs are incorporated into a university’s budget (Hudson Vitale & Ruttenberg, 2022). This model is considered to be the most equitable model for both readers and authors (Meagher, 2021). Second is hybrid, or “pay to publish”, which is a dominant model among profit-driven publishers – in this model, a journal requires a subscription in order to access the full contents, but authors may choose to pay a publication fee to make their article openly available (Piwowar et al., 2018). Thus, a hybrid journal will have a mix of articles that are open or closed to non-subscribers (“Hybrid Open-Access Journal,” 2022). The third category is green OA – this is a broad set of criteria relating to the ability to store a version of the research article in a research repository, personal web site, or other approved website. Green OA is largely dictated by the journal and/or publisher – many publishers will only allow a prior version of an article, such as the author accepted manuscript rather than the published version of record and may impose an embargo period before this version of the research can be made publicly available (Open Access Glossary, n.d.).

Data on overall rates of open access publishing is imprecise, given the range of definitions and methods used to collect the data. A 2018 study estimated that, at a minimum, 28% of the scholarly literature published between 1950 and 2015 is OA with year-over-year data showing a steady increase including exponential growth beginning in 2000 (Piwowar et al., 2018). However, open access growth varies by discipline, leaving CBR and service-learning research out of the analysis due to its interdisciplinary nature (Maddi, 2020; Severin et al., 2020).

Discussions in the literature on why journals – or in the case of hybrid, individual authors – choose to publish open access tend to focus on scholarly impact and citation metrics, disciplinary norms, or the demographic characteristics of the authors (Langham-Putrow et al., 2021; Piwowar et al., 2018; Severin et al., 2020; Zhu, 2017). However, some research has been devoted to why specific disciplines may have a stronger imperative to publish open access due to the needs of their audience(s) (Wirsching et al., 2020).

Knowledge Sharing and Impact Assessment for Scholars and Community Partners

The results of campus-community scholarly endeavors matter to both parties, necessitating thoughtful communication and assessment strategies. Comprehensive program assessment is not straightforward and assessment tools that have been developed and honed over time tend to leave published scholarly work out of their scope of review. Building on early attempts at impactful measures focused on student learning, Portland State University developed a framework that is inclusive of students, the institution, faculty, and community (Driscoll et al., 1998; Gelmon et al., 2018). While this expansion of review adds value to our understanding of community-engaged work, the continued absence of the distribution of information/knowledge as a specific outcome leaves a gap in our understanding if community partner information needs are being fulfilled. While researchers may see publication as primarily impacting academia, community and practitioner partners may feel excluded from the published results of the partnership, particularly when research is locked behind a subscription-based ‘paywall’.

The gap between scholarly publications and assessment of community and service-learning partnerships partly arises from a lack of attention, or articulation of the need, to share information. Additionally, institutional and academic research evaluation models also encourage the researcher to think of their impact in two entirely different contexts: one is how their research impacts community partners – which is often included as a measure of service – and an entirely separate context is the evaluation of the researcher’s scholarly impact. These evaluations are most commonly associated with promotion, tenure and/or rank (PRT), where scholarship and service are usually separated and evaluated using different scales and levels of expectation and reward. In fact, pre-tenured faculty interested in research methods that engage the community report facing pressure to delay such work in favor of more traditionally valued scholarship (Changfoot, 2020). Even as engaged scholars have made headway in aligning institutional values of service and engagement to PRT policies, advocates see “a long way to go to fully align promotion and tenure policies to encourage and support scholarly outreach and engagement.” (D. M. Doberneck, 2022, p. 15). Evaluation of scholarship, or “research impact”, has been traditionally dominated by bibliometrics, which are quantitative indicators based on citation counts designed to showcase ‘impact’ narrowly focusing on other academics as the sole impact audience (Chin Roemer & Borchardt, 2015). The absence of non-scholarly audiences in scholarship evaluation is the operationalization of a value deficit where community impact is severely downplayed if not entirely absent from the traditional scholarly evaluation model. This separation of community impact and scholarly impact is clearly documented in advice for getting tenure for community-engaged scholars, who encourage researchers to publish “translated” research outputs, and separately recommend publishing in high-impact journals (Morgridge Center for Public Service, n.d.). Similarly, one of the most commonly-used rubrics for evaluating the institutionalization of service-learning, presented by Furco (1999), the rubric mentions promotion and tenure, but does not discuss publications as a measure of service-learning.

The scholarly evaluation process advocates and research translation advocates alike fail to fully acknowledge or assess the demand for access to published articles coming from the broader community. The community based research literature promotes alternative forms of information dissemination for community: community meetings, blog posts, op-eds, policy briefs, or even skits are recommended research outputs for meeting community information needs (Hacker, 2013; Strand, 2003, p. 115). This “translation” of research is commonly assumed to be necessary to overcome a perceived language barrier to accessing publications. However, communities are diverse in their information needs and some describe the challenge as one of access and timing rather than intellectual accessibility. In Karen Hacker’s book chapter, Translating Research into Practice: View from Community, community partners like Alex Pirie expressed frustration with the time lag between data collection and publication/dissemination of results. ““The time delay between the conclusion of a research project and the publication of papers is always a problem. This is a period of time when, because of the constraints of journal publication, there is a virtual embargo on the results except in the most general way, and it drives the community side nuts. ‘Hey, we know this, we want to do something with/about it!’” Alex Pirie, Somerville, MA” (2013, p. 12). Similarly, when nursing home social workers were asked what academia could do to support their daily work, they asked that academic research not be kept behind a paywall (Miller et al., 2022). This demonstrates an unmet need for access to scholarly research publications that translated outputs cannot meet. This unmet need may arise from considering community partners as a homogenous population, rather than separately considering the information needs of subgroups with more differentiated information needs, such as practitioners and other professionals. While translation materials can play an important role in meeting the diverse audiences of CBR where they are, researchers and journal editors should not assume an absence of interest in access to published scholarly work.

Our Study

Given the assessment that open access movements and CBR scholars have shared values of information sharing with communities beyond the academy, and a commitment to mutual benefit for all parties, we wanted to examine the degree to which community-based research and service-learning journals are fulfilling these values. In particular, we assess the extent to which they are identifying practitioners and other community members as audiences, making their research openly available to these audiences, and assisting researchers in measuring their impact. To do this, a range of sources was analyzed to identify a corpus of journals in these fields, then collected information about them including the publisher, open access policy, and stated target audiences. Our results show that open access practices in service-learning and community-based research journals exceed the norm for scholarly publishing but is still not a standard expectation for journals in the field. Further, openness is aligned with community service and service-learning research values, but not always explicitly articulated or adopted by the fields. Finally, tools for scholars to assess their impact through these venues varies widely. We discuss why open access is vital to CBR and service-learning partnerships and suggest potential pathways to fully closing the loop between scholars and their community partners in ways that would ultimately benefit both, as well as the development of reward systems for researchers that would value open publishing as a community impact practice.

Methods

We started with identifying scholarly journals focused on community service or service-learning. This began by identifying a corpus of journals that fall within our parameters: an appropriate content focus, peer-reviewed, and actively publishing content. Two Campus Compact resources provided a total of 27 journals (D. Doberneck, 2021; “Journal Section Comparison Table,” n.d.). We added 11 community-based qualitative research journals from a book focused on the topic (Johnson, 2017). Illinois State University offers its faculty and students a list of publication opportunities, largely affirming the Campus Compact list while giving us two additional titles to include (2022). A total of 6 journals were removed from our list due to being out of scope (1, not peer-reviewed) or no longer in active publication (5), giving us a total of 34 journals for our analysis. One publication was erroneously listed in Campus Compact as “Journal of Health Sciences and Extension” but is included in our study under its correct title, “Journal of Human Sciences and Extension”. For a complete list of journals included in the study, see Appendix A.

We identified categories of information we wanted to gather for each journal in order to learn more about the journal’s stated mission, scope, history, open access policy, available impact metrics, and how this information reflected the journal’s stated values, audience, and intentions.

For each publication we used a variety of sources to gather the information for the identified categories. We used each journals’ website when possible, gathering data on how the journal itself made the information available to readers and authors. Websites were used to collect information for: publisher, open access policy, targeted audience, targeted authors, article-level impact measures/metrics, any indications of policy change regarding openness of content when available, and any other relevant notes or content we discovered. To collect narrative data on intended authors and audience, we reviewed and collected relevant statements from the journal’s stated aims and scopes, missions, and journal introductions. In some cases, we also looked up the journal introduction found in volume 1, issue 1: where editors often expanded on who the journal was for and what it hoped to achieve. We gathered journal-level metrics from Scopus (CiteScore), Google Scholar Metrics (H5-index), and Cabell’s Publishing (acceptance rate). Date of first issue was pulled from Ulrichsweb Global Series Directory.

The resulting dataset was compiled and analyzed in an Excel spreadsheet. Most variables were easily observed on the journals’ website, including open access, publisher, and impact metrics. To establish author and reader intent, statements were copied from the “about us” or “aims and scope” sections of the websites and coded according to the themes that emerged: Mentions multi/interdisciplinary contributors, emphasis on methodology, by/for students, mentions practitioners or community partners, discipline specific scholars, and targets new or emerging scholars. Peer debriefing, pulling content from websites during a confined time period, and researchers’ expertise in scholarly communications were employed to aid in establishing credibility (Anfara et al., 2002, p. 30). For several categories including metrics and open access status, criteria were established based on the authors’ expert analysis of the journal website information.

Results

Open Access Status

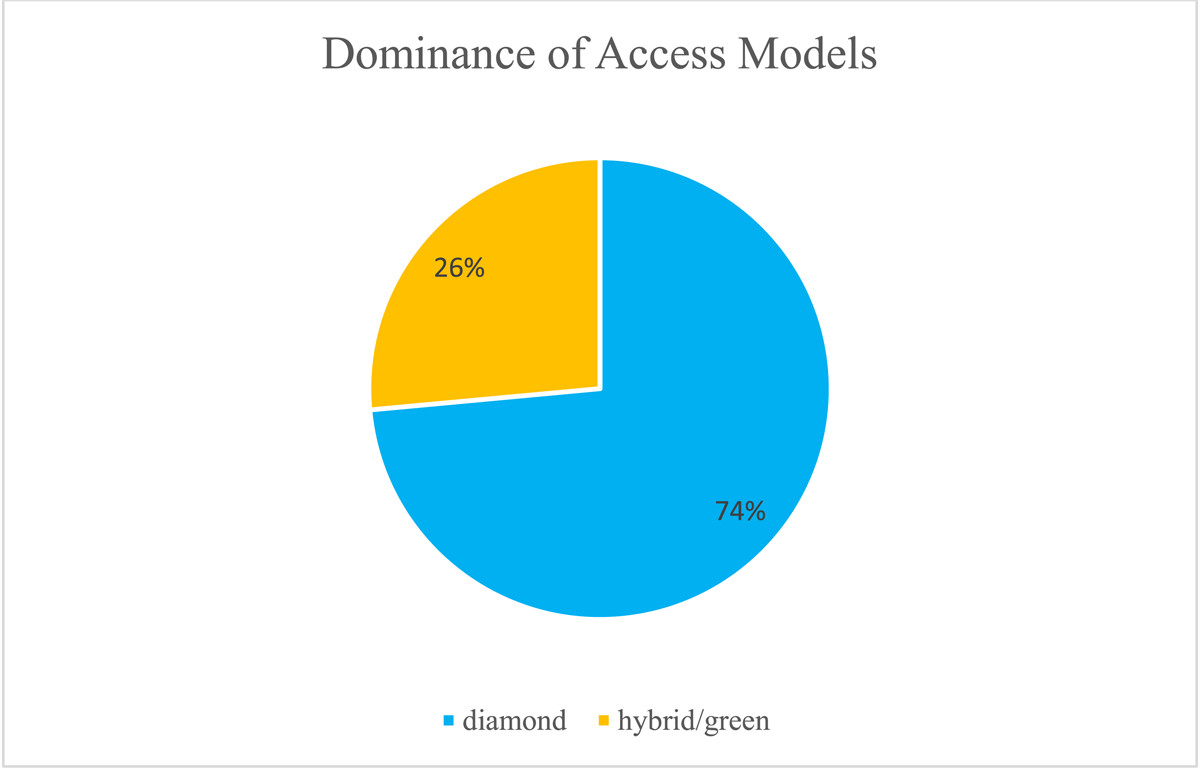

Overall, the set of journals is predominantly open – the most common model is diamond, with a variety of university or society publishers hosting these titles, with 25/34 titles operating under this model (Figure 1). The remaining nine titles were all considered to be hybrid titles, and all had various conditions set for green OA for ‘closed’ articles, or those published articles where authors do not pay to make their article open.

Publisher

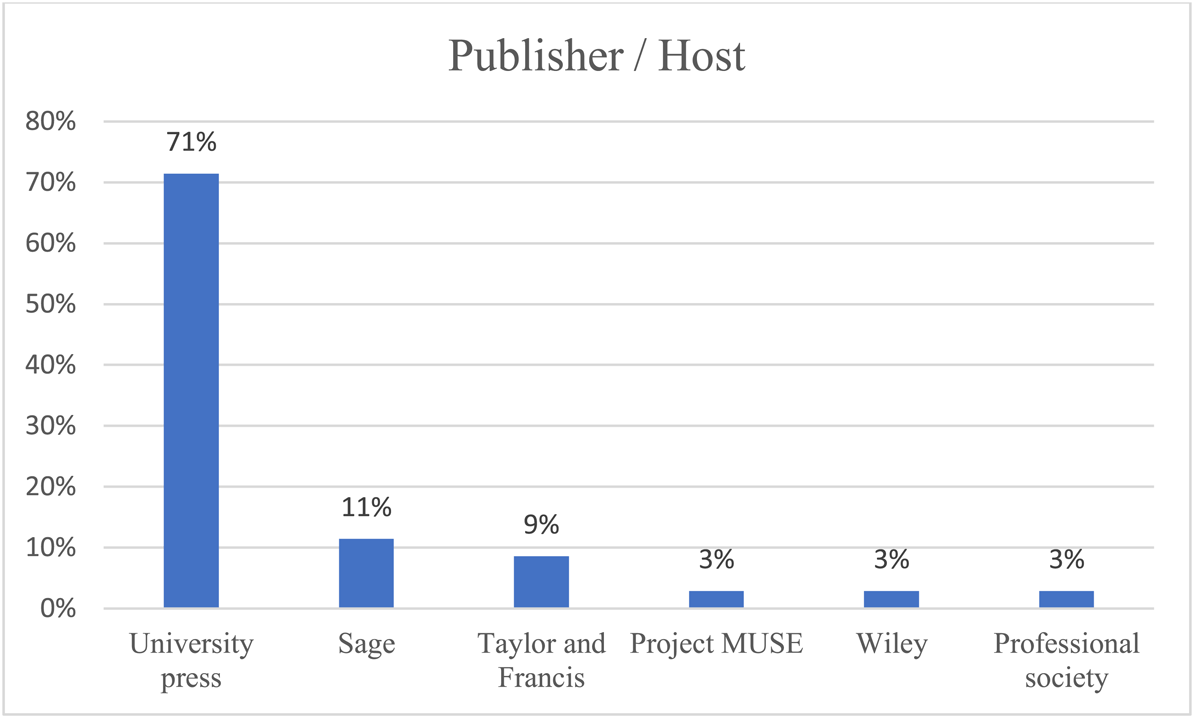

We did not attempt to record the range of institutions hosting diamond titles, but grouped them together as “university presses”, which accounted for 71% of titles (Figure 2). Most of these university presses are mostly considered to be small or medium-sized university presses. A total of 8 titles, or 23% of those analyzed, are published through a for-profit publisher: four titles are published by Sage, three titles published by Taylor & Francis, and one title is published by Wiley. Sage, Taylor & Francis, and Wiley are all “top five” for-profit publishers in terms of market share and profit (Larivière et al., 2015). In addition to the for-profit titles, one non-profit title is published by Project MUSE, a journal subscription package owned by Johns Hopkins with over 700 individual journals, and one is published by a professional society.

Journal Level Metrics

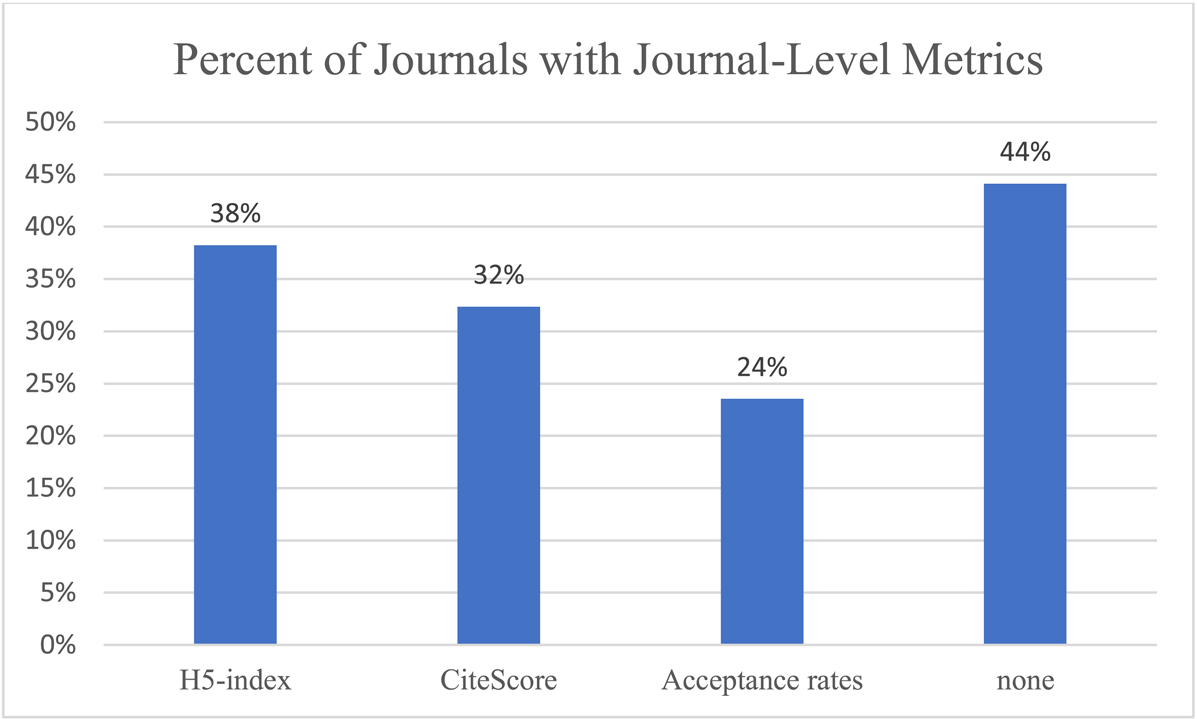

The overall rate of article level metrics for the journals was low. The most common metric was Google Scholar’s H5-index, which was available for 13 or 38% of the journals, followed by Scopus / Elsevier’s CiteScore, which was available for 11 or 32% of the journals, and we found acceptance rates for eight or 24% of the journals (Figure 3).

15 of the 34 journals, 44%, did not have any of these metrics. The 11 journals indexed in Scopus were associated with a total of 12 separate subject classifications, with education the only subject appearing for more than two journals. The breakdown of subjects and individual titles in each classification are shown in Table 1.

Prevalence of Journal Categories for Journals Indexed in Scopus

| Subject Classification | No. of Journals | Journal Titles |

| Education | 5 | International Journal of Science Education, Part B: Communication & Public Engagement Journal of ExtensionAnthropology & Education Quarterly Ethnography & EducationCommunity Health Equity Research & Policy |

| Sociology and Political Science | 2 | Journal of Community Practice Journal of Experiential Education |

| Anthropology | 2 | Anthropology & Education Quarterly Journal of Community Informatics |

| Social sciences (miscellaneous) | 1 | Journal of Community Informatics |

| Public Health, Environmental, and Occupational Health | 1 | Community Health Equity Research & Policy |

| Public Administration | 1 | Journal of Community Practice |

| Health (social science) | 1 | Community Health Equity Research & Policy |

| General Medicine | 1 | Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action |

| Gender Studies | 1 | Ethnography & Education |

| Development | 1 | Journal of Community Practice |

| Cultural Studies | 1 | Ethnography & Education |

| Communication | 1 | International Journal of Science Education, Part B: Communication & Public Engagement |

Article Level Metrics

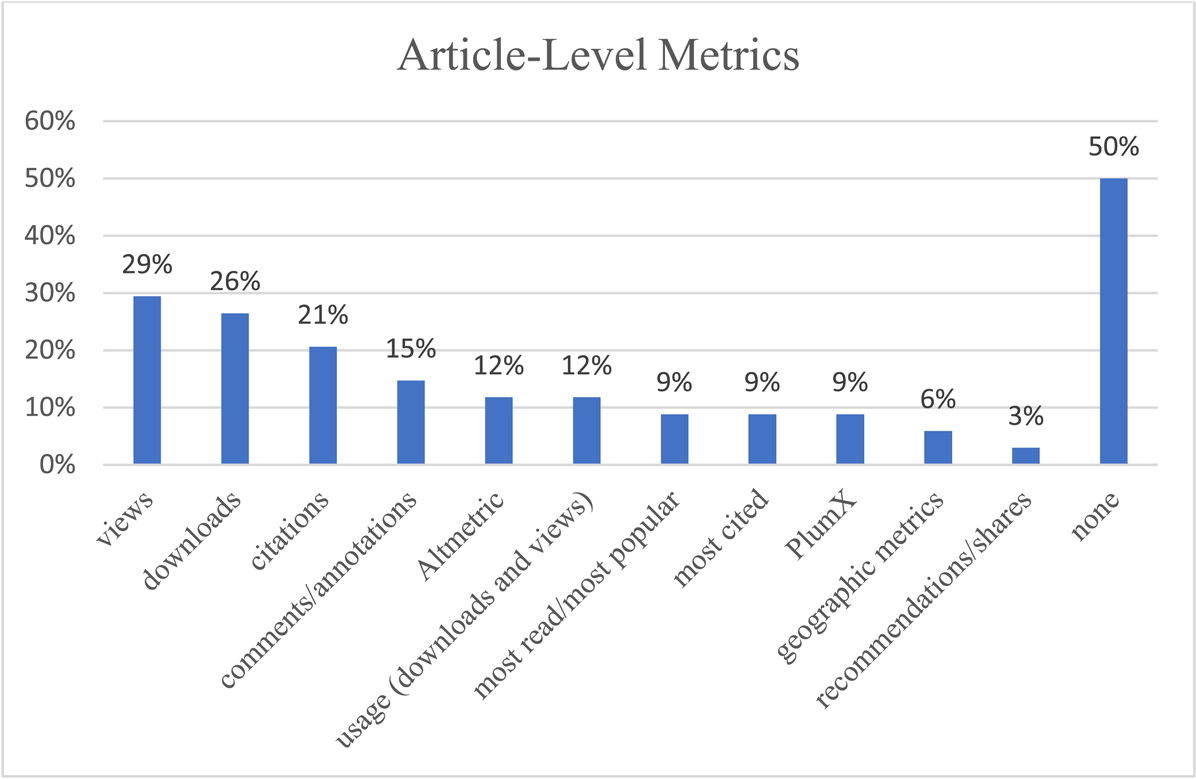

Publicly-available article level metrics were available for 50% of the journals, with views (29%) and downloads (26%) being the most common of the available metrics (Figure 4). Two vendors that collate various sources of altmetrics, Altmetric and PlumX, were available for four (12%) and three (9%) of the journals respectively. Citations, available for seven (21%) of the journals, came from different sources, such as CrossRef. The lack of altmetrics standardization between journals appears to be a result of the variety of publishers, who use a diversity of open access platforms to host content, that likely drove the availability of these metrics. More careful analysis of hosting platforms would be needed to verify this observation, but was outside the scope of this study.

Targeted Authors and Audience

For each journal included in the study, we pulled language from their website that indicated their intended contributors and audiences. While there is no standardized place for this information, “about us,” “aims and scope,” or mission/vision statements were common sources. In some cases, authorship criteria or peer review standards illuminated explicit intent to include community partners or practitioners as both contributors and readers. For example, the Journal of STEM Outreach describes itself as “a bridge between the STEM and education world,” demonstrating a desire for academic and practitioner readership, and the Interdisciplinary Journal of Partnership Studies seeks “interdisciplinary contributions from both scholars and practitioners worldwide,” indicating a desire for authors from many disciplines, community partners, with a global audience. Practitioners and community partners are more likely to be identified as readers than contributors, with 14 of the journals mentioning this group as either co-authors or potential contributors and 26 identifying them as beneficiaries of the content. Nine journals have at least a partial focus on advancing CBR methodology. Two of these, however, stand out in their commitment to including community partners through all aspects of the research process. Both Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research Education and Action and Gateways: International Journal of Community Engagement and Research encourage the voices of community leaders as contributors and co-authors, and they also include them in their pool of peer reviewers. Two others from our sample – Collaborations: A Journal of Community-Based Research and Practice and Engage! Co-Created Knowledge join in this practice, for a total of four journals with peer reviewers outside of traditional academic institutions.

While the review sought to understand the roles faculty researchers and community partners played in the production of, and audience for, the research, other groups emerged as an intentional focus. Six of the journals target students, and five explicitly mentioned emerging scholars. In some cases, this took the form of a dedicated section of journal contents, while other journals instead encouraged co-authorship. This holistic approach breaks down not only town-gown barriers but acknowledges every member of the research and learning process of the value their voice brings to the table.

Discussion

The journals selected for this study have OA practices that far exceed the norm for academic publishing. This shows consistency between the reciprocity values of CBR and the publishing practices of journals devoted to publishing the scholarly outputs of scholar-community relations. While overall values alignment is strong, a few exceptions stand out when comparing the target author and audience analysis to publishing practice. One of the journals that recommends the inclusion of community partners as authors publishes on a hybrid/green model. Similarly, 19% of journals that encourage community readership are hybrid rather than diamond.

If community engagement in authorship and readership cannot fully predict diamond open access status, it is worth considering other factors such as timing and publishing platforms. Severin, et al. note three distinct phases of OA, arcing from formation in the 1990s to transformation from the early 2000s to the mid-2010s, to stabilization running through the present (2020). The mean start date for the journals under review was 2004. Indeed, some older publications show a transition to OA in keeping with the times, having come to life under traditional subscription models. This can be seen with Journal of Extension (1963) where the inaugural volume was sponsored by a university consortium with the expectations that subscription fees would cover the cost moving forward, and Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning (1994) which initially funded itself through subscriber fees with content openly available after a six month embargo, shifting to a fully open access model with Volume 23 Number 1 in 2017 (Ferguson & Carter Jr., 1963; Howard, 2017).

A bigger factor currently, however, seems to be the nature of the publisher. We saw near-perfect alignment between open access status and publishing model – all of the journals published with a for-profit publisher are hybrid/green publications, as well as Project MUSE, which is published by a university press, Johns Hopkins, but operates more like a traditional content publisher due to the size of Project MUSE’s journal portfolio. Thus, we classified Project MUSE separately as a non-profit publisher, distinct from the for-profit and other university press publications. Conversely, all titles published by a university press are diamond publications. These two results show that OA practices are influenced by both date of journal establishment as well as publisher.

Both journal-level and article-level metrics are somewhat limited for the set of journals used in this study. Ultimately, this limits the extent to which researchers publishing in these publications can demonstrate how their research publications are impacting scholarly and other intended audiences, however it does underline the importance for community-based researchers to demonstrate research impact in a way that is often distinct from other, more traditional approaches to impact, such as the use of journal-level metrics. While we see some impact frameworks for CBR and service-learning research, they largely bypass the role of metrics, as well as that of impact audiences. A robust set of metrics of measures allows researchers to more fully craft their impact story – which audiences benefited from their research, and in what context. For these researchers, their story will also include qualitative measures that are appropriate to their community partners – surveys and other assessment measures, as well as documentation of ways in which research results are appropriately shared with these partners. As discussed, this may include publication in fully open access venues with journals whose stated scope and audience are aligned as well as other ‘translated’ outputs that are tailored to individual community partners or other audiences such as practitioners, a broader community, or the general public.

We began our investigation looking for open access publishing as a way for the academy to meet its obligations of inclusiveness to their community partners. Reciprocity, however, also includes the need for researchers to meet their scholarly goals. While these publications are largely open to the community, they could improve their impact on the scholar’s career by enhancing available metrics, allowing the scholar to better make the case of the value of CBR scholarship.

It is tricky to draw definite conclusions from studying the target author and audience. While some journals do see community members as playing a more active role in the publication process, as discussed in the results, it is likely that other journals see community members primarily as readers rather than as contributors. In that context, the content of the journals may contain messaging more closely aligned with this audience than the journal’s website, which we hypothesize is catered more toward potential authors. Furthermore, it is likely that there are private formal or informal policies in place in journals related to how and to what degree community plays a role in the journal, making our findings incomplete. However, clearly communicating those intentions on the website would help increase transparency and give those community members greater understanding of the role they play.

Limitations

Defining the set of journals proved challenging – some of the journals on this list are more squarely focused on community-based research or service-learning, while others are larger journals who regularly publish research that cover these two topics, often within a disciplinary mindset, as Table 1 shows. However, focusing more narrowly on the most highly relevant journals, or expanding our set to include other journals whose scopes are inclusive of community-based research or service-learning perspectives, would likely have altered many of our findings: as we noticed with many of the non-diamond journals falling into the latter, larger category of journals. More work to define this set of journals is still needed, given the disparity we encountered in the lists we used to construct our set.

We were also limited in the information we were able to collect. For example, some journals offer authors the ability to log in to their journal’s system, at which point additional article-level metrics may have been made available. Policies or other types of information are likewise not always obvious or made publicly available on the journal’s website, or may not have been available at the time of our study as journal websites are updated. Our research took place over the course of a few months, so we were able to observe some “real-time” updates, such as a journal ceasing publication while still remaining on a recommended list, however, we did not have definitive historical access to shifting policies, changes in scope, etc. This limits our ability to measure the scope or rate of changes we observed in a more meaningful way than chance observation.

Recommendations and Future Research

Recommendations for Journals, Editorial Boards, and Journal Editors

Altmetrics can assist researchers in demonstrating the attention, engagement, and impact of their research. However, 50% of the titles examined do not seemingly offer any article-level metrics, which limits this impact demonstration. Journals should consider adopting practices that are beneficial for their authors, including a diamond OA model, and adoption and incorporation of a variety of metrics to assist its authors in demonstrating their impact.

It is unlikely, however, that Wiley, Sage, Taylor & Francis, and Project MUSE will adopt a diamond OA model in the near future. Project MUSE will debut a “Subscribe to Open” model of OA support for some of its titles beginning in 2025, but for the three for-profit publishers, it is likely that all three will continue relying on the hybrid publication model as their dominant revenue model unless external forces necessitate a shift to an alternate source of funding and support (Project MUSE, n.d.). Therefore, any possibility for many remaining non-diamond titles to adopt equitable OA models is uncertain as long as these publishers continue to own and operate these publications.

Journals could more carefully consider adopting practices that account for the role of the community in the journal process, particularly if they see a role for community members in the publication process. We likewise recommend that the role of community members be clearly articulated on the journal’s website, and ideally, also mentioned in their mission and scope.

Recommendations for Authors

Authors should consider the availability and impact of their research when deciding where to publish and prepare a dissemination strategy for both scholarly and community audiences that is timely and accessible. They should also ask about ways hybrid journals in this field can work toward diamond open access to reach and impact their stated or presumed broader, non-scholarly audiences; in the hopes that community pressure can bring about positive change for these journals and further align disciplinary values with publication outlets.

Recommendations for the Fields of Community-Based Research and Service-Learning

Models for measuring impact in these fields could be revised to explicitly endorse and prioritize open access publications as a high impact practice. For example, the Furco model rubric’s highest level of institutional achievement, “Sustained Institutionalization”, would be enhanced by inclusion of open access publications as a pathway toward reward for service-learning scholars beyond the more generic goal of “recognition”, which further disincentives these faculty to prioritize open access rather than “high impact” when choosing a publication outlet (1999).

Updated impact models could include distinct impact audiences, relevant measures, ways to demonstrate appropriate outreach to audiences, and evidence of how research is impacting these audiences, including publishing in a journal that actively considers the role of one or more of these groups in their publishing and/or readership. These impact audiences include the broader community: including specific subgroups such as practitioners, and community members, as well as the general public. This kind of approach to defining and outlining measures is already happening elsewhere in academia; two notable examples are the Becker Model, which defines five distinct areas of impact for biomedical research, and the ACRL Framework for Impactful Scholarship and Metrics, which outlines ways for academic librarians to document scholarly and practitioner impact of their scholarship (Bernard Becker Medical Library, 2018; Borchardt et al., 2020). In addition to establishing impact frameworks, researchers may also consider using the newly-created Researcher Impact Framework, which is designed to support researchers in defining and evaluating impact audiences (De Moura Rocha Lima & Bowman, 2022). A dissemination strategy and gathering of relevant metrics can then be incorporated into the full description of scholarly and non-scholarly impact of the research.

Recommendations for Evaluators of Community-Based and Service-Learning Research

Further support for this approach to impact documentation can and should be added to PRT guidance for institutions that prioritize community-based research or service-learning. This strategy can likewise be adopted by grant funders to assist in the evaluation of grant proposals and resulting impact of funded research. Professional organizations and societies with close ties to community-based research and service-learning should consider describing and endorsing a full range of measures and metrics to demonstrate impact of this research.

Further Research

We see several avenues for further research, such as working with journals in our list that have ceased open access publication in order to examine and even help resolve sustainability issues. Alternately, working with editors of hybrid journal publications to better understand the factors that may help encourage a move to a fully open access model, in partnership with individuals associated with journals who have already made such a move. Surveying community-based research scholars would help to better clarify the role and value of open access and different metrics for these scholars when making strategic publication decisions, and how these decisions may differ based on type of appointment, such as tenure-track vs. non-tenure-track. On the other hand, surveying community members would help to understand how they interact with journal content, and where they see gaps in communication, partnership, or availability of research, and if there are differences in opinion between different types of community members. We hope that this publication will encourage creation of a more holistic impact model for community-based research and service-learning that acknowledges open access publications as a form of community impact and establishes community impact as a value and goal for research and researchers operating under a scholarly impact-dominant model of evaluation. Finally, we see an avenue for future research that elucidates the specific information needs of different population groups such as practitioners that are commonly seen as community partners, in order to better understand when and how information can be provided to these partners that fully satisfy their respective needs.

Conclusion

Community-based research and service-learning aim to bring research out of the ivory tower and positively impact community partners. Making research publications openly available for use by community partners, or specific subgroups of partners such as practitioners, has not been commonly identified as a best practice or assessment standard for evaluating the success of these research partnerships, and may constitute a lack of understanding between the academic and community researchers. This study determined that, while the majority of journals that publish research in these fields are fully open access, there is room for improvement to fully integrate and incentivize open access publications for academic researchers. These researchers would also benefit from being able to access robust altmetrics in order to demonstrate non-scholarly engagement with their research, and this effort could also be meaningfully supported through revised evaluation guidelines. Researchers in this field could consider discussing open access support for publications that are not already fully open access in order to try to fully align these journals’ values with their stated non-scholarly audiences.

References

Anfara, V. A., Brown, K. M., & Mangione, T. L. (2002). Qualitative analysis on stage: Making the research process more public. Educational Researcher, 31(7), 28–38. http://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X031007028

Bernard Becker Medical Library. (2018). Becker Medical Library model for assessment of research impact. Becker Medical Library. https://becker.wustl.edu/impact-assessment/model

BOAI. (2002). Budapest Open Access Initiative. http://www.budapestopenaccessinitiative.org/read

Borchardt, R., Bivens-Tatum, W., Boruff-Jones, P., Chin Roemer, R., Chodock, T., DeGroote, S., Hodges, A. R., Kelsey, S., Linke, E., & Matthews, J. (2020). ACRL framework for impactful scholarship and metrics.

Butler, L. A., Matthias, L., Simard, M. A., Mongeon, P., & Haustein, S. (2022). The oligopoly’s shift to open access publishing: How for-profit publishers benefit from gold and hybrid article processing charges. Proceedings of the Annual Conference of CAIS / Actes Du Congrès Annuel de l’ACSI. http://doi.org/10.29173/cais1262

Campus Compact. (2022). About. Campus Compact. https://compact.org/about

Changfoot, N. A. (2020). Engaged scholarship in tenure and promotion. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 26(1). http://doi.org/10.3998/mjcsloa.3239521.0026.114

Chin Roemer, R., & Borchardt, R. (2015). Meaningful metrics: A 21st century librarian’s guide to bibliometrics, altmetrics, and research impact. Association of College and Research Libraries, A division of the American Library Association. http://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/publications/booksanddigitalresources/digital/9780838987568_metrics_OA.pdf

Clarke, M. T. (2020). The journal publishing services agreement: A guide for societies. Learned Publishing, 33(1), 37–41. http://doi.org/10.1002/leap.1266

De Moura Rocha Lima, G., & Bowman, S. (2022). Researcher impact framework: Building audience-focused evidence-based impact narratives. http://doi.org/10.25546/98474

Doberneck, D. (2021). Annotated List of Interdisciplinary Community Engagement Journals. https://compact.org/resources/annotated-list-of-interdisciplinary-community-engagement-journals

Doberneck, D. M. (2022). Are we there yet?: Outreach and engagement in the consortium for institutional cooperation promotion and tenure policies. Journal of Community Engagement and Scholarship, 9(1), 8–18. http://doi.org/10.54656/RNQD4308

Driscoll, A., Gelmon, S. B., Holland, B. A., Kerrigan, S., Spring, A., Grosvold, K., & Longley, M. J. (1998). Assessing the impact of service learning: A workbook of strategies and methods. 2nd Edition. Center for Academic Excellence, Portland State University, P.

Ferguson, C., & Carter Jr., G. (1963). About this issue. Journal of Extension, 1(1), 2–4.

Furco, A. (1999). Self-assessment rubric for the institutionalization of service-learning in higher education. Service Learning, General. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/slceslgen/127

Fyfe, A., Coate, K., Curry, S., Lawson, S., Moxham, N., & Røstvik, C. M. (2017). Untangling academic publishing: A history of the relationship between commercial interests, academic prestige and the circulation of research. Zenodo. http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.546100

Gelmon, S. B., Holland, B. A., Spring, A., Driscoll, A., & Kerrigan, S. M. (2018). Assessing service-learning and civic engagement: Principles and techniques. Campus Compact. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/aul/detail.action?docID=5508400

Hacker, K. (2013). Translating research into practice: View from community. In Community-based participatory research. http://doi.org/10.4135/9781452244181.n5

Howard, J. (2017, April 9). Welcome. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning. https://web.archive.org/web/20170409110135/https://quod.lib.umich.edu/m/mjcsl/

Hudson Vitale, C., & Ruttenberg, J. (2022). Investments in open: Association of research libraries US university member expenditures on services, collections, staff, and infrastructure in support of open scholarship (pp. 1–18). Association of Research Libraries. http://doi.org/10.29242/report.investmentsinopen2022

Hybrid open-access journal. (2022). Wikipedia. Retrieved November 22, 2022 from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Hybrid_open-access_journal&oldid=1119205812

Illinois State University. (2022). Publication opportunities. https://civicengagement.illinoisstate.edu/faculty-staff/publication-opportunities/

Israel, B. A., Schulz, A. J., Parker, E. A., & Becker, A. B. (1998). Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 19, 173–202.

Jacoby, B., & Howard, J. (2014). Service-learning essentials: Questions, answers, and lessons learned. John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/aul/detail.action?docID=1813354

Johnson, L. R. (2017). Community-based qualitative research: Approaches for education and the social sciences. SAGE Publications, Inc. http://doi.org/10.4135/9781071802809

Journal section comparison table. (n.d.). Campus Compact. Retrieved June 6, 2022, from https://compact.org/resource-posts/journal-section-comparison-table/

Kuh, G. D., & Schneider, C. G. (2008). High-impact educational practices: What they are, who has access to them, and why they matter. Association of American Colleges and Universities.

Langham-Putrow, A., Bakker, C., & Riegelman, A. (2021). Is the open access citation advantage real? A systematic review of the citation of open access and subscription-based articles. PLOS ONE, 16(6), e0253129. http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0253129

Larivière, V., Haustein, S., & Mongeon, P. (2015). The oligopoly of academic publishers in the digital era. PLOS ONE, 10(6), e0127502. http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0127502

Maddi, A. (2020). Measuring open access publications: A novel normalized open access indicator. Scientometrics, 124(1), 379–398. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03470-0

Maiter, S., Simich, L., Jacobson, N., & Wise, J. (2008). Reciprocity: An ethic for community-based participatory action research. Action Research, 6(3), 305–325. http://doi.org/10.1177/1476750307083720

Meagher, K. (2021). Introduction: The politics of open access — Decolonizing research or corporate capture? Development and Change, 52(2), 340–358. http://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12630

Miller, V. J., Anderson, K., Fields, N. L., & Kusmaul, N. (2022). “Please don’t let academia forget about us:” An exploration of nursing home social work experiences during COVID-19. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 65(4), 450–464. http://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2021.1978027

Morgridge Center for Public Service. (n.d.). How to earn tenure while doing community-engaged scholarship. University of Wisconsin-Madison.

OA2020 – Home. (n.d.). Retrieved July 28, 2022, from https://oa2020.org/

Open access glossary. (n.d.). ChronosHub. Retrieved November 22, 2022, from https://chronoshub.io/open-access-glossary/

Piwowar, H., Priem, J., Larivière, V., Alperin, J. P., Matthias, L., Norlander, B., Farley, A., West, J., & Haustein, S. (2018). The state of OA: A large-scale analysis of the prevalence and impact of Open Access articles. PeerJ. http://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.4375

Project MUSE. (n.d.). Retrieved November 22, 2022, from https://about.muse.jhu.edu/news/S2O-UPDATE-2025

RELX 2022 annual report. (2023.). Retrieved September 1, 2023, from https://www.relx.com/~/media/Files/R/RELX-Group/documents/reports/annual-reports/relx-2022-annual-report.pdf

Severin, A., Egger, M., Eve, M. P., & Hürlimann, D. (2020). Discipline-specific open access publishing practices and barriers to change: An evidence-based review. F1000Research, 7, 1925. http://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.17328.2

Smith-Lever Act of 1914, Pub. L 63–95, 38 Stat. 372 (1914).

Strand, K., Marullo, S., Cutforth, N., Stoecker, R., & Donohue, P. (2003). Community-based research and higher education: Principles and practices. (1st ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Willinsky, J., & Rusk, M. (2019). If research libraries and funders finance open access: Moving beyond subscriptions and APCs. College & Research Libraries. http://doi.org/10.5860/crl.80.3.340

Wirsching, H., Penny, D., Lucraft, M., Franssen, J., Vanderfeesten, M., van Wesenbeeck, A., & Jansen, D. (2020). Open for all: Exploring the reach of open access content to non-academic audiences. http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4143313

Zhu, Y. (2017). Who support open access publishing? Gender, discipline, seniority and other factors associated with academics’ OA practice. Scientometrics, 111(2), 557–579. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-017-2316-z

Author Bio

Olivia Ivey, MSSW, MLS, is an associate librarian supporting research, teaching, and learning in American University’s School of Public Affairs. She has previously worked in the law library and the U.S. Department of Labor. Prior to her library career, she worked as a program director at a senior center in New York City. Her research interests center on the practical application of information literacy, including research skills and implementation in community settings.

Rachel Borchardt, MLIS, is the Scholarly Communications Librarian at American University in Washington, DC. Rachel previously worked as the Science Librarian at American, as well as the Biology and Neuroscience and Behavior Biology Librarian at Emory University. In her current job, Rachel supports open access, open education resources, and research impact initiatives through the library. Her scholarly interests concern equitable models for research production and evaluation, including diverse models for measuring and rewarding non-scholarly impact and translated research outputs.

Appendix A

Journals Included for Review

Action Research Journal

Anthropology & Education Quarterly

Collaborations: A Journal of Community-Based Research and Practice

Community Health Equity Research & Policy

Engage! Co-Created Knowledge

Engaged Scholar Journal: Community Engaged Research, Teaching and Learning

Ethnography & Education

Gateways: International Journal of Community Engagement and Research

Interdisciplinary Journal of Partnership Studies

International Journal of Service Learning in Engineering

International Journal of Research on Service-Learning and Community Engagement (IJRSLCE)

International Journal of Science Education, Part B: Communication & Public Engagement

International Journal of Service-Learning in Engineering and Social Entrepreneurship

Journal of Community Engagement & Scholarship

Journal of Community Engagement and Higher Education

Journal of Community Informatics

Journal of Community Practice

Journal of Deliberative Democracy

Journal of Experiential Education

Journal of Extension

Journal of Health Sciences and Extension

Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement

Journal of Participatory Research Methods

Journal of STEM Outreach

Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning

Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action

Public: A Journal of Imagining America

Purdue Journal of Service-Learning and International Engagement

Qualitative Inquiry

Reflections: A Journal of Community-Engaged Writing and Rhetoric

Research for All

Science Education & Civic Engagement

The Journal of Service-Learning in Higher Education

Undergraduate Journal of Service-Learning and Community-Based Research