Reciprocity is a core component of community-engaged learning (CEL), a “threshold” concept that, once understood and put into practice, transforms teaching and, in effect, enacts or realizes community engagement (Harrison & Clayton, 2012; Miller-Young et al., 2015). The influential Carnegie Foundation classification positions reciprocity as a cornerstone of its definition of community engagement: “Community engagement describes collaboration between institutions of higher education and their larger communities (local, regional/state, national, global) for the mutually beneficial exchange of knowledge and resources in a context of partnership and reciprocity” (Carnegie Foundation, 2022, para. 1).

Still, the question of what reciprocity looks like in an over-researched, inner-city community remains underexplored. Universities have a social obligation to work in the interests of over-researched communities and may wish to ensure that community perspectives are central to their work. Yet they must also take care to ensure they do not exacerbate existing harms by further overburdening community members or putting them at risk by introducing underprepared learners to their community.

All of these issues are magnified in urban CEL today. At a certain point in the 1990s, community service learning1 was touted as a method to help overcome academic overspecialization, repair a democratic deficit in universities, and rebuild universities’ sense of responsibility to their surrounding communities (Boyer, 1997). In the decades since, community engagement has become institutionalized in the higher education sector; in most major Canadian research universities, including our own, it has become an institutional priority (Dean, 2019, p. 36 n.1; Ferguson et al., 2021, p. 15). However, more recent critiques from critical university studies have observed that community engagement has been repurposed by universities’ downtown real estate portfolios and is effectively legitimizing ongoing gentrification and dispossession (Baldwin, 2021; Dean, 2019). The stakes for CEL projects are higher than ever, and the question of how a university-based, student-learning-oriented project can be a benefit and not a burden to participating communities has never been more complex.

Our approach to this problem has been to create a CEL project that responds to community-identified priorities and benefits community members without requiring the direct presence of large numbers of university students in the neighborhood. In this project, first-year undergraduate students in introductory academic writing courses at the University of British Columbia (UBC), Vancouver, Canada, create publicly accessible infographic summaries of research articles arising from studies that have taken place in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside (DTES) neighborhood. This initiative addresses a community-identified priority to access jargon-free research findings about their community.

This paper explores how our thinking about reciprocity has expanded during a multi-year pilot of this project, outlining key discoveries and lessons learned. As a team of scholars and librarians with varied experiences working on community-engaged initiatives, we believe that this project offers a promising model for community engagement and knowledge exchange for undergraduate education. This initiative could be replicated where similar dynamics exist—where a research university seeks to do community-engaged work in an over-researched, under-resourced community. Although our evaluation of the project is preliminary and was interrupted by the sudden shift online with the onset of COVID-19 protections in 2020, we offer some initial evaluation results, along with a detailed description of the project, its partners, and its outputs through a reflective case study.

After a short overview of scholarship on reciprocity, we describe below how our complex project brings together undergraduate and graduate students, instructors, community-engaged researchers, librarians, staff at a community-embedded academic unit, and community members themselves in a form of “generativity-oriented reciprocity” (Ashgar & Rowe, 2016, p. 122): something new is created by bringing different groups together that could not have been created otherwise. Through this case study, we outline how this project offers multidirectional benefits to all participants while drawing on a unique combination of project participants’ assets, capacities, and labor. Next, we explore crucial insights gained in the process of doing CEL in an over-researched community. Our discussion then turns back to the concept of reciprocity, raising some institutional and instructional questions, exploring challenges encountered, and sharing three key takeaways that have emerged in the course of piloting, reviewing, and sustaining this work.

Literature Review

To date, the scholarship on reciprocity has called attention to reciprocity’s multiple and sometimes contrasting meanings in practice (Dostilio et al., 2012). Much of the research articulates a surface/depth or thin/thick distinction between different kinds of reciprocity: on the one hand, surface reciprocity has been based on “mutual benefit” to different stakeholders, usually learners and the community; on the other hand, deep reciprocity means the integration of community voices at all levels of a project, as a form of community co-research and co-creation of knowledge (Saltmarsh et al., 2009, pp. 10–12; Miller-Young et al., 2015, p. 34). This surface/depth distinction maps more or less directly onto CEL’s recent field-defining distinction between “traditional” and “critical” models of service learning (Mitchell, 2008; Getto & McGunny, 2016), where traditional approaches “[emphasize] service without attention to systems of inequality,” and critical service learning is “unapologetic in its aim to dismantle structures of injustice” (Mitchell, 2008, p. 50). While existing scholarship is hesitant to criticize projects based primarily around mutual benefit, it tends to prefer projects with reciprocity designed into every step, from inception to delivery to impact, as these move beyond transactional or charity models of service learning while instead valuing community expertise, and flattening power imbalances between university and community.

Lina D. Dostilio et al.’s (2012) “concept review” (p. 18) of reciprocity in community engagement complicates this picture in a helpful way. The authors have a non-hierarchical take on the surface/depth models; in their view, “thin” mutual benefit projects and “thick” co-research projects are merely different modes of reciprocity, appropriate to different circumstances and community engagement projects. In their three-part distinction between “exchange-oriented, influence-oriented, and generativity-oriented” (pp. 19–20) forms of reciprocity, Dostilio et al. make clear that no one approach should be normative in the field and that CEL practitioners need to develop better ways to evaluate projects based on specific contextual variables, including community capacity and institutional orientation.

Dostilio et al. (2012) arrive at this non-hierarchical conclusion after a survey of reciprocity in disciplines beyond CEL, especially Indigenous research, in which long traditions of thinking about reciprocity are foundational to sophisticated Indigenous ontologies. Continuing that line of influence, we note that for Vine Deloria Jr. and Daniel R. Wildcat (2003), reciprocity structures Indigenous ways of knowing through ethical relationships with human and non-human worlds in a posture of respectful, attentive, and responsible openness. It is moral, holistic, and assumes deep community engagement (2003, p. 23, 149). In practice, reciprocity combats the “intellectual colonialism” (Gaudry, 2011, p. 114) of Western epistemologies, whose relationships with Indigenous peoples across the globe have been typified by cultural appropriation, extraction, and imperialist logics of elimination (Tuhiwai Smith, 1999, p. 1). In response and in defense of their communities, Indigenous scholars like Linda Tuhiwai Smith outline non-extractive Indigenous research protocols built on principles of reciprocity and accountability (1999, pp. 15–16). A main concern with respect to reciprocity for Margaret Kovach (2009) is how research is shared with participating Indigenous communities: relevancy is integral to giving back. Is the research relevant to the community, and could the community make sense of the research? Dissemination of the research is a central issue, and it is important to ensure that the research is available to the community in a manner that is accessible and useful (Kovach, 2009, p. 149). Reciprocity, in this sense, implies knowledge translation, or ensuring that participant communities have opportunities to read and use any research being produced with their participation.

Many terms are used to describe activities and systems for sharing knowledge, such as mobilization, transfer, exchange, translation, brokering, and management. Shaxson et al.’s (2012) foundational concept paper gathers, defines, and theorizes these kinds of functions and processes as part of the K* spectrum. The spirit of the collaboration described in our paper best aligns with their definitions of knowledge exchange, “a two-way process of sharing knowledge between different groups of people,” (p. 2), and knowledge brokering, “a two-way exchange of knowledge about an issue, which fosters collective learning and usually involves knowledge brokers or ‘intermediaries’” (p. 2). However, due to the narrower scope of student work in our project, we describe their contributions as knowledge translation, which Shaxon et al. (2012) define as “the process of translating knowledge from one format to another so that the receiver can understand it; often from specialists to non-specialists” (p. 2).

Kovach’s recommendation that research be made accessible and useful to participating communities has also informed our project. We thought pragmatically about how CEL relationships often run the risk of straining community capacity. In analyses of university-community relationships, “research fatigue”—a barrier to reciprocity— is discussed in Indigenous studies and public health research. In Indigenous studies, Audra Simpson’s (2007) notion of ethnographic refusal, or Indigenous sovereignty over representation and participation in research and knowledge-making activities, has been broadly influential. When taken up by Tuck and Yang (2014), refusal is a reasonable response for Black and Indigenous communities who have experienced extractive research relationships and are subject to increased requests to participate in research studies (Tuck and Yang, 2014; Tuck, 2019; Tuhiwai Smith, 1999).2 Likewise, in public health research, the question of research fatigue with marginalized, vulnerable research populations has been raised (Ashley, 2021). Community research fatigue is not only an issue for researchers, but also for CEL practitioners. For example, Wollschleger et al. (2020) question the co-research model’s need for substantial commitment of resources from the community “by asking them to invest a non-trivial amount of time and energy to providing educational opportunities for my students and not really getting anything back from student involvement” (p. 7). Wollschleger et al. instead designed a project that provided a knowledge exchange deliverable for communities without asking for commitment in return: “Course projects became an actual product that was given to a local organization” (2020, p. 14). Their model is an important one when engaging with over-researched and vulnerable communities, as its focus is on building capacity. Reciprocity in this sense, though it does not involve “thick” co-research, is nevertheless an example of Mitchell’s (2008) concept of critical CSL, as it empowers future community-based research by directing university resources towards community benefit. This capacity-building approach to knowledge exchange informs our approach to communicating research published about, with, and for Vancouver’s DTES community.

Context

The Downtown Eastside Neighborhood

The DTES is the historic heart of Vancouver and has a diverse, predominantly low-income population. It is also home to a significant urban Indigenous population, many of whom have been displaced from their original communities by colonial violence (see Appendix A for an Indigenous Land Acknowledgement). As defined by the City of Vancouver, the DTES consists of seven adjoining neighborhoods, each with a distinct character, population, built form, and land use (City of Vancouver, 2013). The DTES has attracted more than its share of research attention due to high concentrations of poverty, substance use, precarious housing, compromised health, and other expressions of historical trauma. DTES residents recognize and describe it as a heavily researched community (Neufeld et al., 2019). Most of this research is published in subscription-based scholarly journals by researchers and students at local academic institutions (Linden et al., 2013). As such, many of these articles are not available to people who live and work in the DTES; this circumstance has led these groups to produce a manifesto—Research 101: A Manifesto for Ethical Research in the Downtown Eastside, 2019—denouncing extractive research practices, calling for greater consideration of potential research harm, and urging researchers to communicate findings to DTES residents in accessible ways (Neufeld et al., 2019). During the development of our project, the DTES was experiencing two overlapping public health emergencies: the COVID-19 pandemic and the toxic drug supply crisis. Sensitivity to these considerations made it even more critical to design a CEL project that minimized our ask of community members while maximizing reciprocal benefit.

Institutional Relationships: The UBC Learning Exchange and Arts Studies 100

The UBC Learning Exchange (LE) is an off-campus space in the DTES established in 1999. It provides a physical, shared space where UBC students and faculty and DTES residents and organizations connect, pursue common interests, and learn from each other in order to bring about social change (Towle & Leahy, 2016). The LE provides free educational programs for community members, diverse learning opportunities for students, and support for community-based research and knowledge exchange. LE staff act as boundary spanners (Weerts & Sandmann, 2010), helping bridge the two cultures of a research-intensive university and an over-researched inner-city community.

In 2013, the Making Research Accessible initiative (MRAi) was established by the LE in response to community concerns that research is not accessible to people in the community (McCauley & Towle, 2022). Its goals are to:

Increase the accessibility and impact of research by providing easier online access to research about the DTES;

Identify community-generated materials and increase their availability in and beyond the DTES;

Create opportunities for community organizations, community members, researchers, students, and others to share information and learn from each other.

In March 2020, the MRAi launched the DTES Research Access Portal (RAP), a public repository that as of October 2023 contains over 1900 items of relevance to the DTES including peer-reviewed articles, community-generated reports, podcasts, infographics, and other genres (https://dtesresearchaccess.ubc.ca/). An important offshoot of the MRAi has been the collaborative creation of knowledge exchange products that make academic research more understandable to community members.

ASTU 100

Two of this paper’s co-authors teach Arts Studies (ASTU) 100, a full-year literary studies and academic writing course in the Law and Society stream of the Coordinated Arts program at UBC. Their course is part of a first-year, cohort-based “university gateway” program; ASTU 100 introduces students to university-level writing and research, and offers credit towards a writing breadth requirement for the BA degree. The course positions students as “apprentice researchers” (Bonnet et al., 2013, p. 37), learning the craft and conventions of research writing via genre-based writing curriculum and assignments (Giltrow et al., 2021). Our particular sections of ASTU 100 had incorporated small-scale CEL components in the three years prior to this project, partnering with legal non-profits and community organizations, most of whom are based in the DTES. The course’s CEL orientation is communicated to incoming students via video testimonials from past students posted to our program’s website. Instructors have also worked with the University’s Centre for Community Engaged Learning, who run introductory workshops for students before they begin their community engagement. These workshops help prepare students for the kinds of issues and interactions that might come up when working on community-based projects and have them consider questions concerning positionality, power, and privilege, as well as the university’s own role in processes associated with knowledge production and mobilization.

Case Study

Creating Plain Language, Community- Oriented Infographic Summaries

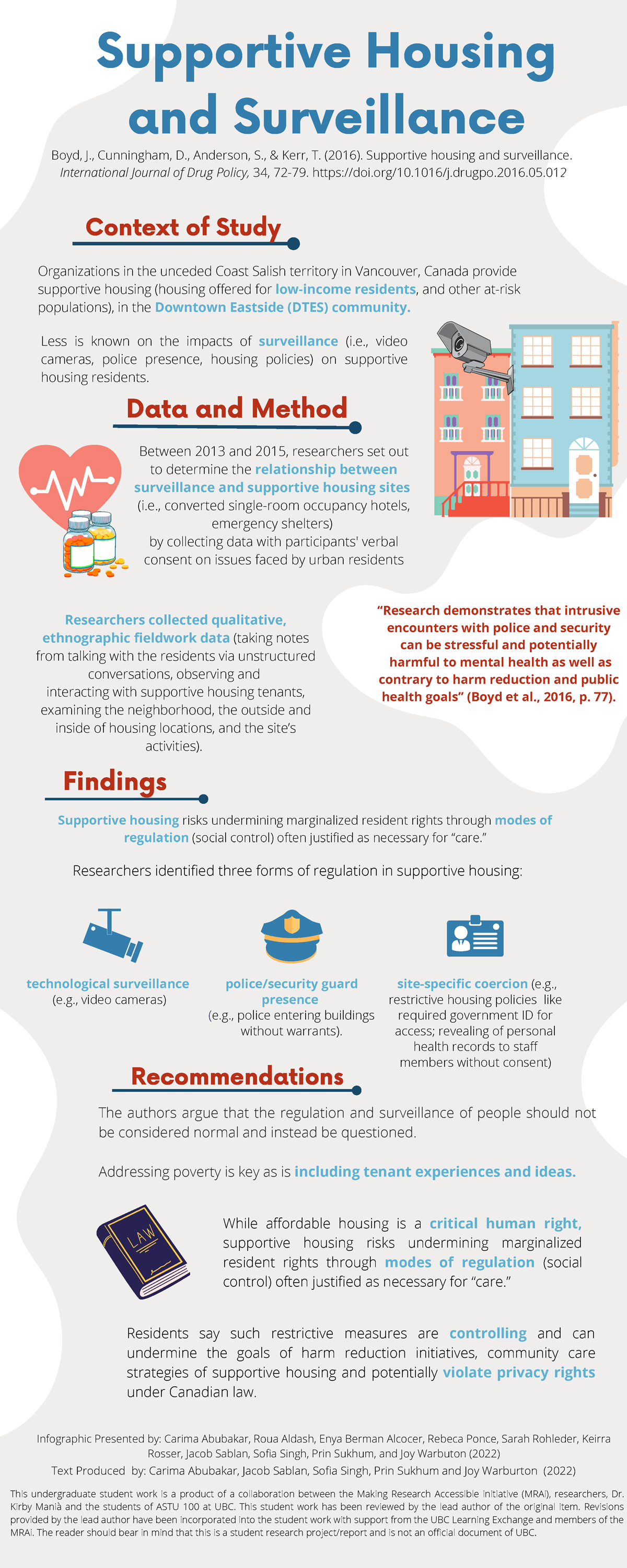

The ASTU instructors partnered with the LE’s MRAi project in 2019 in order to incorporate a robust knowledge translation assignment into the CEL component of their course (see Appendix B for a description of the project collaborators). This assignment sees first-year students translating research articles and producing accessible, plain-language3 infographic summaries to be made available on the RAP. Community members have identified infographics as a preferred model of knowledge translation (O’Brien et al., 2020, p. 35). The format consists of graphic visualizations that combine data, illustrations, text, and images to tell a story (Dunlap and Lowenthal, 2016).4 Infographics are frequently used as a vehicle to share various kinds of public service information, news stories or, more recently, as a way to disseminate academic research, particularly in public health scholarship (Thoma et al., 2018; McSween-Cadieux et al., 2021). An example of an infographic produced from this project is provided below; for more examples, refer to Appendix C.

Figure 1

Note. This infographic is based on the following article: Barker, B., Sedgemore, K., Tourangeau, M., Lagimodiere, L., Milloy, J., Dong, H., Hayashi, K.,Shoveller, J., Kerr, T., & DeBeck, K. (2019). Intergenerational trauma: The relationship between residential schools and the child welfare system among young people who use drugs in Vancouver, Canada. Journal of Adolescent Health, 65 (2), 248- 54. This infographic was created in the second year of the partnership.

CEL in the Writing Classroom

In designing this project for the first-year writing classroom, we drew on a cluster of publications from around 20 years ago that, taken together, describe a “a microrevolution in college-level Composition through service-learning” (Alder-Kassner et al. 1997, p. 1). Deans’ Writing Partnerships (2000), in addition to essay collections by Alder-Kassner et al. (1997) and Zlotkowski (2002), break a path for instructors who want to include CEL projects in writing courses. These collections document community-engaged projects in which “novice college writers are working in teams to compose research reports, newsletter articles, and manuals for local nonprofit agencies” (Deans, 2000, p. 1) and collaborating with communities on the complex writing classroom topics of genre, audience, and voice. Our project shared with this literature the twin aims of expanding our students’ introductory writing experiences while addressing community-articulated priorities.

By the time ASTU students start the collaborative knowledge translation project that this paper focuses on, they have practiced writing summaries of scholarly articles, which forms the first step in their academic writing curriculum. They have also been exposed to a series of guest lecturers speaking on topics such as community organizing for police accountability, harm reduction, Indigenous sovereignty, and resilience in the face of structural violence and have participated in public DTES events organized by community members. This knowledge translation project (which forms part of their CEL) builds on these two foundations: engaging with scholarship, and learning about community-level organizing work. The project is usually worth a total of 10–15% of their yearlong course grade. A key learning outcome of the course is to have students respond to a range of different writing situations—familiarizing themselves with both scholarly and public-facing genres. This assignment presents students with an authentic writing experience: they get to interact with real authors and prepare a document with a targeted audience in mind, and write with the very real possibility of having their work published in an institutional repository with a wide reach. In this way, students get to appreciate that research has public functions beyond writing classrooms and university readerships. Another important outcome for the course is that students gain an understanding of how disciplinary knowledge can be used to address community-identified issues and needs, and that they gain that understanding in an introductory context, near the beginning of their burgeoning sense of what research is and what it can do.

The project consists of two major assignments for students to complete: producing a summary and then an infographic based on articles arising from DTES research studies (hosted by the LE’s RAP). This process consists of a series of iterations and interventions, which is described in more detail in Table 1 below. By means of giving a high-level overview, students are first divided into research teams5 and assigned research articles available on the RAP that speak to relevant course themes. Students are then tasked with producing a group summary of the research article, where the most cogently summarized team submission is sent to the corresponding author of the article for feedback and approval. Once a summary version of the article has received author approval, all student teams assigned to that source create an infographic from the approved summary. Each research team then works independently but from the same approved summary to produce an infographic—even teams whose summary was not sent to the article’s author for approval. This gives all teams another chance at having their work selected to form the basis of the infographic—a pedagogically inclusive strategy, as it gives student research teams an opportunity to shine in different areas. The most effective infographics are then selected by the instructors and the LE team (i.e., the faculty and staff collaborating on this project) to be sent to the corresponding author for a final stage of approval, after which students sign a Creative Commons license and deposit the infographics in UBC’s institutional repository, cIRcle. These infographics are then linked as items on the RAP; they are also posted as “related materials” attached to the open access version of the associated research article which they “translate” (see: https://dtesresearchaccess.ubc.ca/object/ext.5572). After creating their infographics, students also write and read each other’s reflective writing about the process, as part of the overall assessment for the project.

Annual Project Timeline

| Stage 1: Knowledge Translation Planning | ||

| Activity | Timing | Description |

| 1. Article Selection | Summer | Instructors meet with the LE community-based research coordinator and community engagement librarian to identify potential articles. Articles are assessed for suitability based on the following criteria: appropriate length and complexity for first-year students, relevance to the course theme, and relevance to the interests of community members. LE collaborators draw on thematic analysis of RAP use, community surveys, conversations with community partners and residents, and reference questions posed by community members to determine which research topics best reflect community interest. |

| 2. Author Outreach | Fall | The LE does initial outreach to authors of selected articles, explaining the project and the collaboration and asking for their participation. Participation includes reviewing student summaries and infographics and offering feedback. We make it clear that RAP publication will be contingent on researcher approval. |

| Stage 2: Class Preparation | ||

| Activity | Timing | Description |

| 3. LE & DTES Orientation | January | Students attend a class or video lecture in which the LE team introduces the LE and the RAP, exploring the kinds of community-based research compiled there. |

| Stage 3: Student Participation and Author Feedback | ||

| Activity | Timing | Description |

| 4. Article Assignment | January | Instructors match students to selected articles based on the students’ interests. Students are assembled into working groups of 4–5 members. All students enrolled in ASTU participate in the project. One article is worked on by two groups, so the best work can be forwarded to the corresponding authors.6 |

| 5. Plain-language Text-Based Summaries | January– February | First, students individually summarize their assigned article, using summary and citation skills learned in their ASTU 100 course. Where students’ previous summaries were written for academic audiences, this time the instructors ask that they use plain-language principles to make the summary more legible to more people. Next, teams of students working on the same article will read each other’s work and produce one consolidated, group-authored summary. Instructors grade those and send excellent summaries to the articles’ authors for approval and feedback. |

| 6. Learning Design Principles | February | Students review a video outlining key principles of infographic design for community use. This video was created by a professional experience student in UBC’s Master of Library and Information Studies program based on a review of promising practices and a series of community focus groups described below. |

| 7. Infographic Design | February–March | Students work in groups to create infographics based on the summary text approved by the article’s author. Students make use of free or library-subscribed services such as Canva, Visme, and Piktochart to create an initial infographic design. |

| 8. Infographic Peer Review | February–March | Students participate in a peer-review workshop, offering feedback on each other’s infographic design and evaluating how successfully they have implemented the principles they have learned for effective, community-oriented design. |

| Stage 4: Stakeholder Approval | ||

| Activity | Timing | Description |

| 9. Team Infographic Evaluation | March | Student groups submit their infographics for review by instructors and the LE team. Here, project collaborators select one excellent example per article (which they often send back to students for revisions). |

| 10. Author Infographic Evaluation | April | Once revised, these selected infographics are sent to the authors for feedback and approval. This second editorial step with authors is key: drafts are passed back and forth until the authors are satisfied that the infographic accurately represents their research. |

| Stage 5: Licensing and Access | ||

| Activity | Timing | Description |

| 11. Publication and Dissemination | April | MRAi collaborators then arrange for Creative Commons licenses to publish student work in UBC’s institutional repository, cIRcle. Each infographic is assigned metadata and added to the RAP, along with a prominent link to the original article. Often the article itself is paywalled by publishers, but the infographic is publicly available. Infographics may be shared online, posted publicly at the LE, and used for programming. |

| Stage 6: Reflection and Renewal | ||

| Activity | Timing | Description |

| 12. Debrief and Reflection | May | At the conclusion of each year’s project, collaborators reflect on what was effective, where they were challenged, and how they can improve their collaboration. |

Our process to develop infographic summaries with students has evolved over each year of the project. It currently involves six stages and 12 steps described in Table 1.

Unique Roles of our Collaborators

As evident in the activities outlined in Table 1, this project requires the unique expertise and perspectives of community-embedded librarians, instructors, researchers, students, and the LE team at various stages of each year’s collaboration. In this section, we will outline some of the unique skills and perspectives our collaborators brought to this project and the roles they played in its development.

First-year Students as Knowledge Brokers. As mentioned above, this project offers students an authentic writing situation (i.e., a real-world purpose) in which they negotiate the interests and needs of different audiences while engaging in a process of knowledge translation. It develops students’ first-year research skills, and thereby offers a new approach to the perennial question of how to use student writing and research capacities to offer reciprocal value to participating communities, a particularly tricky question in first-year classes that incorporate CEL.

This project positions first-year students as interlocutors, situating them between the community and researchers, which requires them to translate academic jargon and methodologies into accessible terms. It capitalizes on students’ somewhat liminal status. Although they are relative newcomers to the post-secondary academic environment, they have also been equipped with a number of practical strategies to help them engage with and make sense of scholarly material. Students’ recent introduction to scholarly writing might in fact be an asset, as it helps them immediately grasp how research genres can strike non-academic readers as esoteric and alienating; however, they have sufficient skills to negotiate some of these complexities due to their instruction in ASTU 100, as the course guides them through identifying levels of reasoning in dense passages and helps them decode the conventions of research genres.

As they are developing their facility in translating research, students are also drawing on other skills that the project requires. Specifically, students’ ability to quickly learn and use free infographic-making software like Canva, Piktochart, and Visme has been essential to the project. We offer a rudimentary introduction to these software tools when introducing general principles of infographic design and point them towards helpful templates, but rely on two factors for students’ quick uptake and use of the programs: (1) there is a degree of “digital nativity” that first year students possess that allows them to operate the programs successfully (many of whom have used these tools extensively for secondary school projects); and (2) by asking students to work in groups, and having more than one group developing infographics for each article, we structure redundancy into the project’s outputs, making it more likely we receive an infographic that article authors are happy with. This is one example of how our project enacts a “generativity-oriented reciprocity,” (Ashgar & Rowe, 2016, p. 122): pairing researchers who may not have knowledge-translation or digital skills with groups of students who do, and offering a collaboration that benefits them both.

Classroom and Community-Embedded Academic Librarianship. Academic librarians are increasingly recognized as having a knowledge exchange role beyond the university community. They frequently act as information intermediaries and knowledge brokers in community-based settings (O’Brien et al., 2020). The community engagement librarian role at the LE was established in April 2020 as a pilot position to advance the MRAi’s goals and initiatives, including uptake of the RAP, as well as to leverage information expertise and resources to strengthen connections between the UBC Library and DTES communities by responding to organization and community member priorities.

As this project demonstrates, community engagement librarians have much to offer CEL projects because of their work as boundary-spanning knowledge brokers (Reale, 2016; Towle & Leahy, 2016). By working with university students in a classroom-embedded context, as well as with DTES residents in a community-embedded context, the community engagement librarian facilitates collaboration among stakeholders with diverse levels of information literacy while applying promising practices for knowledge translation, digital curation, and open licensing.

Graduate Student Involvement and the Development of Infographic-focused Materials. A Master’s of Library and Information Studies graduate student was recruited to support the third year of the project. The student completed a for-credit, 120-hour professional experience project supervised by the LE’s community engagement librarian that investigated promising practices for accessible research visualization and devised a set of recommendations to guide the ASTU students in designing effective infographics. These promising practices and recommendations were informed by an in-depth literature review and environmental scan as well as two 45-minute focus groups with the target audiences for the student infographic project: DTES community residents and organization staff.

Following this project, the graduate student joined the MRAi as a graduate academic assistant. This extended participation in the project provided the student with opportunities to offer additional contributions, including a recorded video lecture on practical principles for effective infographic design and co-facilitating a peer-review workshop with ASTU students.

Project Outputs

As of November 2022, 17 infographics have been produced through this project. They have had 4,801 views and 1,001 downloads within cIRcle alone, and are among the most accessed items in the RAP. This summary does not include other venues in which these have been shared and accessed digitally via social media and partner websites or physically, i.e., at the LE drop-in, pop-up libraries, community engagement events, and Knowledge Café discussion groups in the DTES.7

In Table 2, we outline the results of this project in each of its three years.

Infographics Produced and Published on the RAP

| Year of Project | # of Research papers | # of Students | # of Summaries Produced | # of Infographics Produced | # of Infographics Published on the RAP |

| Year 1 (2019–2020) | 11 | 74 | 24 | 9* (best 3 forwarded to researchers for feedback) | 3 |

| Year 2 (2020–2021) | 8 | 95 | 23 | 23 (best 8 forwarded to researchers for feedback) | 8 |

| Year 3 (2021–2022) | 8 | 100 | 23 | 23 (best 8 forwarded to researchers for feedback) | 6** |

| Total | 27 | 269 | 70 | 55 | 17 |

-

Notes. *Project was curtailed in Year 1 in some sections of the course due to the disruption caused by the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, which explains the lower number of infographics produced.

**In 2022 we had two infographics that were not ultimately approved by the researchers, despite engaging in the review process up to that point.

Reflecting on Reciprocity

Challenges and Lessons Learned

In this section, we discuss the challenges we encountered in this project and how we have responded by modifying our approach in subsequent years.

First, participating researchers are busy and feedback is required in a timely fashion for students to complete this work within a semester. It is critical to ensure article authors are prepared to meet the timelines set out in our initial communication and to provide helpful reminders throughout the term. Maintaining consistent and open communications with authors ensures we can make as many accommodations as possible while still remaining on track to complete the project by the end of the academic year.

Second, it takes significant effort to bridge the differing perspectives of researchers and students. Researchers sometimes insist on longer text or disciplinary jargon to reflect the depth and nuances of their work. They understandably seek full expression of their ideas, but out of necessity, the infographics must focus on the higher-level ideas and act as a preview of the deeper explorations that the genre of an academic article allows for. Students, on the other hand, are focused on plain language, community-oriented writing. Our solution to navigate these sometimes-competing objectives was to draft principles for editing to share with the researchers, based on promising practices for plain language, community-oriented writing; these principles served to develop shared goals and expectations.

Third, this project requires a high volume of administrative and communications support to coordinate between each stakeholder. Much of this work is currently shouldered by the LE. While we aspire to grow this project to increase its reciprocal benefits and better address the backlog of DTES-based research articles without a more accessible alternative, we need to increase our administrative capacity in order to do so.

Finally, this project was also rolled out in the Spring of 2020, under unique circumstances that had a profound effect on its development and current form. While COVID protections slowed or postponed many other community engagement initiatives at UBC and across the postsecondary landscape, the nature of our project made it possible as a remote teaching alternative. Our orientation workshops were still possible on Zoom, and collaborative writing and infographic-making tools like Google Docs and Canva were already in our plan and easy to adapt to remote learning. Beyond these important practical questions, however, the transition to remote instruction had the unanticipated effect of making the project’s most important feature immediately apparent: it practices reciprocity without physical presence, and offers a low-risk, low-demand way for communities to have access to university research output. In 2020–21, the DTES community was dealing with the dual public health emergencies of COVID-19 and an ongoing, worsening drug poisoning crisis. Health care systems were improvising, but many health service providers in the neighborhood shut down (Richardson 2020). Under these circumstances, research partnerships with the community needed to consider carefully what we were asking, and what we were offering. For our project, the pandemic gave new urgency to this critical element of all community partnerships.

Reciprocal Benefits

In this section, we reflect on the ways in which this project provides reciprocal benefits to each of its different community and university stakeholders.

Community Members (Early Findings). As described in our Context section, this project was initiated in response to DTES community interest in the infographic format as a more accessible way to interpret research findings (O’Brien et al., 2020, p.35). Our initial, preliminary community evaluation conducted in the summer of 2021 aimed to give us an indication of whether our project’s infographics could meet that interest. We composed two focus groups after the pilot project’s first year: one with two peers with lived experience in the community, and a second group consisting of three LE staff members with deep knowledge of the community through long standing advocacy, digital literacy, and arts-related roles. Participants were selected based on interest and availability during the brief professional experience project window. Each focus group had a facilitator and a notetaker, lasted 45 minutes, and offered space for participants to share and discuss their initial impressions of two anonymized, student-created infographics, answering open-ended questions (Murray 2021; questionnaire reproduced below in Appendix D). While we intend to engage in further focus groups to affirm the benefit of these products and refine our process, early indicators suggest community members find them compelling and useful.

Participants in the focus groups provided detailed suggestions for improvements. On language and tone, most participants agreed that academic jargon in the infographic summaries was a problem, and plain language explanatory notes were helpful. While one text-heavy infographic, with 362 words, was seen as too “wordy” (Murray 2021, p. 23), another with 147 words left participants “with more questions than answers” (p.23); a good middle ground seemed to be 200–250 words. For visuals, participants indicated that the overuse of graphic illustrations was distracting, and most appreciated a clean, minimalist design, with liberal use of negative space. Other design recommendations included sans serif fonts, a limited color palette, and white or light backgrounds to improve accessibility. Overall, participants agreed that infographics were helpful in quickly understanding the basics of research findings when time, disciplinary expertise, or journal access were limited. Participants commented that they would like to see more infographics created and made available to them. They noted that having an infographic as a complementary resource to a full-text article was ideal, as the infographic introduced the material in a less intimidating format. They could then, if desired, read the full-text article (Murray, 2021, pp. 23–27). These latter results were encouraging for our project, and the focus groups’ specific recommendations have been folded into our introductory workshop on making infographics in subsequent project years.

In order to more fully determine the reliability of these findings, further focus groups with community members are needed and have been added to the LE team’s planning process.

Undergraduate Student Learning. An instructor-designed survey of students8 during the 2020 winter term saw nearly universally positive responses to this project, despite the pandemic moving the major stages of their infographic-making online. The survey was administered by a research assistant; survey questions are reproduced below in Appendix E. We had a low response rate (35%) to this survey, which we attribute to the confusion of the winter 2020 term with its sudden pivot to online learning in response to COVID-19.9 Nevertheless, we found these preliminary results promising, as a few key themes emerged from student responses.

Familiar CEL benefits were evident across many student responses: student paradigms were shifted by working with communities (one student wrote, “it gave me a new perspective”), and students also realized a sense of agency and self-efficacy (another student wrote about “a newfound sense of awareness of the power our words have in representation”). CEL provided intrinsic motivation for students beyond their project or course grade (a student wrote, “I felt more driven to strive for perfection knowing my work could affect people other than myself”).

From our instructors’ context in an academic writing class, a key question was what students learned about the production, circulation, and translation of academic knowledge. Student responses speak of a new understanding about the benefits and limits of research, and specifically about information privilege (“articles written about a group are probably not written for that group”). Students also questioned the limits of researchers’ expertise, reframing knowledge in more relational and reciprocal terms, learning about “the relationship between a researcher and someone in the Downtown Eastside, and how they are to be considered equals.” Some students wrote about a changed sense of what research is and what it can do in the world: one student noted that the course “gave me a different perspective on research,” and another mentioned that “I think I was better able to understand how research can affect communities positively and negatively.” Another student went further: “I think [the most impactful CEL experience] was understanding my role as a researcher and forming relations with the communities I work with, because I feel like this knowledge and perspective will carry on with me throughout my degree and even after school.” This last response tells us that some students were connecting what they learned about information privilege to their own self-positioning as apprentice researchers, and it indicated that this project may have a lasting influence on students’ developing concept of research. In any case, we took responses like these to indicate that our intended pedagogical outcomes, to help students understand how disciplinary knowledge can be used to address community-identified issues and needs, and how to position themselves as writers with different audiences and in different situations, were met.

The survey responses, though limited, were encouraging. All 17 respondents answered affirmatively to two poll questions, whether they “thought [the project] was worthwhile” and whether they “would take a CEL course again.” When asked what could be improved about the program, six of the seventeen responses focused on a desire for more site visits (one student: “having the opportunity to go to the DTES as a class” would be a welcome change). We think this was partly due to the COVID lockdowns that canceled late term in-person sessions, but we also heard in these responses a student desire for immediacy and direct contact with the community. In subsequent years, our student orientation put more emphasis on the notion, quite prominent in the community-authored Research 101 manifesto, that DTES communities are overburdened with requests for participation in studies, and that our project is designed to attenuate this trend. In other words, we shifted our emphasis so that our students’ important reflections about position and privilege would also include some further consideration of their institutional location, and the need for low-burden community engagement projects. By discussing this part of the project more explicitly, we think that students are also learning more about the politics of community engagement, and specifically how to listen to community and prioritize community wellness. As mentioned above, the unique pressures of rolling this project out during a pandemic brought all of these crucial aspects of the project to the surface.

In terms of long-term impact of the project on student learning and their career trajectories, we recognize that more rigorous work needs to be done. The pandemic’s disruption of student learning and the increased operational pressures placed on the research team has delayed the implementation of a more systemic, longitudinal evaluation plan. In the future, the research team intends to survey students in their graduating year to determine the impact the CEL project had on their later learning. Until that happens, we do know that ASTU students have applied for student roles at the LE and across the institution; one ASTU student has supported the LE’s community-facing arts and cultural programming as a facilitator while another ASTU student accepted a research assistant position on a UBC project investigating the feasibility of expanding experiential education across the university. Accordingly, instructors have found it particularly rewarding that this CEL project has encouraged former students to seek out CEL work-learn positions later on in their undergraduate studies

Academic Libraries. This project provides a dual model of community- and classroom-embedded librarianship in support of a non-extractive CEL project that also contributes to scholarship. It has provided opportunities for mentorship and hands-on learning for emerging professionals enrolled in the Master of Library and Information Studies program. And finally, it aligns well with many academic libraries’ high-priority goals related to community engagement, scholarly communications, and instruction, as outlined in the Association of College and Research Libraries’ Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education (American Library Association, 2015).

Researchers. This collaboration supports researchers in making study findings (especially those that are paywalled) accessible in a high-quality format without requiring a significant investment of time or resources on their part. Researchers have the opportunity for their work to be made accessible and available for uptake within and by communities where this work is relevant. Further, they have the satisfaction of supporting student learning in a way where they can offer direct feedback and does not require them to evaluate the students’ work for marking purposes.

We found researchers to be highly engaged. They were excited about the project and this unique approach to supporting student learning. This enthusiasm was unanticipated. As demonstrated in Table 2, we expanded researcher involvement in the second and third years of the project and this was largely based on researchers’ enthusiastic response to the first year of the project.

Instructors and Further Curriculum Development. The instructors involved in this collaboration intend to expand it beyond the first-year academic writing classroom and integrate it into upper-year undergraduate courses. Curricula is being developed to offer new courses in departments beyond the Coordinated Arts program (where the project is currently housed). Increasing the number and variety of disciplinary expertise of instructors supporting this CEL project will provide opportunities for students to engage with more researchers working across a broader range of DTES-relevant and course-supported research areas. While we are mindful of not expanding beyond the capacity of the institutional partnership described in this paper, we are optimistic that this project is replicable, and could provide models for community-engaged undergraduate research activity at different levels of study.

Instructors looking to replicate this model in their own courses would be well served by balancing their students’ competencies and course learning outcomes against two considerations: (1) the desired outputs identified by the community ahead of the community engagement, and (2) available institutional capacity, including needed collaborators and campus units. For the first consideration, community desires could be identified via focus groups before designing course interventions in order to develop knowledge translation outputs that will enjoy authentic utility. For the second, departmental resources to support the hiring of teaching assistants and graduate administrative assistants are crucial to building organizational capacity as implementing community engaged learning pedagogy is significantly labor-intensive. Our experience with this pilot project indicates that both questions require careful deliberation and planning.

Conclusion: Key Takeaways for Reciprocity in Community-Engaged Learning

The multi-year collaboration we have described in this paper, through a reflective case study, illustrates an opportunity for instructors to design CEL projects in which students can engage in knowledge translation work that benefits all who are involved. We consider this sort of project to exemplify a form of “generativity-oriented reciprocity” (Ashgar & Rowe, 2016, p. 122): it assembles the needs and capacities of different groups, and from their collaboration, brings forth something new. We have argued that each of these parts, from student work to the prominent role of librarians to the work of a community-embedded unit, have been indispensable and are key factors to consider in thinking about the project’s replicability. Based on our development, iteration, and assessment of this project over three years, we offer several takeaways that may be applicable to other CEL contexts.

1. Identify Low-risk Opportunities for Students to Engage in Knowledge Translation Work That Meets a Community Priority

Universities produce a lot of scholarship that is inaccessible to the communities involved in its creation. Simultaneously, undergraduate students are not only interested in assignments with real-world value but also bring well-suited dispositions to knowledge translation. As “apprentice researchers” not yet immersed in disciplinary languages, they have proven to be well-positioned as discursive interlocuters and are able to translate specialized research writing effectively and in ways that respond to community-identified priorities.

2. Leverage Complementary Strengths of Different Stakeholders

Our project benefits from the array of skills, perspectives, and capacities each stakeholder brings to the project. Researchers have an eye for detail and complexity, which enriches the quality of student work. Community members ground the translation of research findings into something practical and accessible. Project facilitators draw on their varied skill sets as instructors, librarians, and academics to bring together students, researchers, and community members in collaboration. We were able to draw on the strengths and focused capacity of a graduate student to further our engagement with the community (through the aforementioned focus groups) and distill promising practices for research infographics that sharpened our project and improved the efficacy of its outputs. We, as authors and collaborators, reflect a wide range of disciplinary perspectives, ranging from medical science, sociology, information studies, literature and cultural studies, and writing and discourse studies. These perspectives helped us think about and carry out this project in new ways.

3. Plan to Sustain the Project

When working in a vulnerable community, it is paramount to avoid replicating the cycle of university initiatives that make big promises and disappear before those promises are fulfilled when funding runs out. The long-term, institutional presence of a community-embedded academic unit, the LE, has been crucial to the project’s success given the intensity of resources required to actualize successful reciprocal partnerships. The LE plays a key role in brokering relationships between participating instructors, librarians, researchers, and DTES communities and in centering ethical scholarship and community relationships in students’ understanding of how knowledge is made.

Continuing with this work over several years has also provided ample opportunity to iterate, refine, and improve our processes and the quality of our knowledge translation products. We also believe that we can take this knowledge translation work further; additional classes and courses can be accountable to other communities. We plan for community voices to be integrated more fully in future iterations. While community focus groups have informed our principles for infographic design, we plan to host more thorough focus groups to further discuss related formats of accessible research visualizations (i.e., social media slideshows, videos). These discussions will inform future versions of this project as we also seek to find ways to scale up this work to increase reciprocal benefits for each group involved. One other benefit of scaling up the project pertains directly to its sustainability, as a kind of hedge against the variability of our collaborators’ year-over-year teaching and administrative commitments. When multiple units across the university participate, the project becomes more resilient.

Our thinking on reciprocity will continue to expand as the project evolves, as next steps include refining our project team’s time investment in supporting the project, continuing to prepare students for the rigors of the editorial process to produce public-facing genres, and expanding community evaluation of the efficacy and usefulness of the infographic summaries the project produces.

Notes

- Our paper prefers the term community-engaged learning (CEL) to its alternatives, as it acknowledges the multi-directional exchanges that occur as a result of encounters between students and community members. However, when discussing the history of the field of Service Learning and Community Engagement (SLCE) below, we will follow other authors’ uses of “service” and “service learning”. Discussions in Bortolin (2011) and Vincent et al. (2021) have informed our terminological choices. ⮭

- The second reference (Tuck, 2019) points to a viral tweet thread by Tuck. The first tweet reads, “I have spent last months traveling + visiting with members of Anishinaabe, Haudenosaunee, Métis, Cree, Dene, Yukon, and Inuit Nations + communities; what I have learned is that they are totally exhausted by the new wave of clueless academics showing up to do research on them.” Further on in the thread, she adds, “the researchers say: I have everything taken care of, you won’t have to do a thing! But this is never the case. It is always SO MUCH WORK for communities.” ⮭

- Our project employs the term “plain language” to describe summaries that translate research findings to make them accessible to non-academic readers. This term, however, is contested in Rhetorical Genre Studies, along two lines: (1) potentially simplifying and “dumbing down” (which is inaccurate), and on this basis is patronizing for community audiences—some of whom experience access barriers to higher education but often have long standing, fine-grained experiential knowledge of issues academic arguments claim to discover; (2) “plain language” as an ideology, implying value neutrality and universality, thus making historical and contingent language uses vanish behind a power-laden ideal of so-called “plain” or clear expression (Cameron, 1995, pp. 63–72). We considered some alternative terms, such as “community-oriented language,” but any newly coined term will lack resonance with community participants. The DTES community-authored Research 101 manifesto explicitly calls for the publication of “plain language summaries” as a way of “providing meaningful knowledge translation in the community” (Boilevin et al., 2019, p. 23): this community endorsement of “plain language” was decisive for us. ⮭

- Multimodal means of sharing research information, such as through infographics, create knowledge exchange deliverables that can be more accessible and transmissible to non-academic audiences. Importantly for context, Indigenous traditions have embodied diverse approaches to knowledge exchange since time immemorial. Such approaches have been far from ubiquitous in Western scholarly communications due to the insistence by colonial states on the exclusive legitimacy, or positional superiority, of text to serve this purpose (Akena, 2012; Smith, 2013). Further, colonial states have relied on the legitimized status of Western knowledge exchange through textual means to marginalize Indigenous knowledges, seize cultural property, and displace many communities from their rightful lands. Visually encoding complex information is not new in Indigenous contexts. Many Indigenous cultures not only recognize the value of oral, visual, and other non-textual modes of knowledge exchange but have been and continue to be leaders and innovators in their practice. ⮭

- We experimented with different approaches to student group formation. In one section, students were randomly allocated into Discussion Groups in the first teaching term. These groups remained consistent the entire year, developing trust and rapport, and these Discussion Groups transitioned into Research Teams for the infographic project. In other instances, students were grouped according to their article preferences, having read article abstracts and discussed topics in class. Both approaches worked well, though both required some review of guidelines for productive collaboration in group projects. ⮭

- At least two research teams work on the same assigned article to reduce the number of corresponding authors partnering with the project in any given year. This helps keep the CEL project within the operational capacity of instructors working on the project. This also means that students know that only the strongest summary will be sent to the lead author for commentary and so they are incentivized to produce their best work if they want the chance to see their work published on the RAP. ⮭

- In addition to sharing student-produced infographics digitally and with community members at the LE, this collaboration has also led to the production of other outputs in 2022, which included: a research infographics toolkit and panel discussion with UBC’s Public Humanities Hub (see: https://sites.google.com/view/infographicstoolkit/home); presentations at the British Columbia Library Association’s annual conference; and workshops at the UBC Centre for Teaching, Learning, and Technology’s Winter Institute for faculty. ⮭

- An email with a link to the survey was sent out via the web-based learning management system to all students registered in the course. Of the 49 students who participated in this project, 17 responded to the survey. ⮭

- On March 17, 2020, UBC shifted to remote instruction for all in-person classes. The remainder of the 2020 Spring semester, four out of thirteen weeks, were done online, as was the entire 2020–21 teaching year. ⮭

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the following individuals for their contributions to this project. From the Making Research Accessible in the DTES initiative: Desiree Baron, Aleha McCauley, Kathleen Leahy, Geoff D’Auria, Anita Fata, Lupin Battersby, and Elizabeth Johnston; from the Transformative Health and Justice Research Cluster: Samantha Lee, Pam Young, and Mo Korchinski; from Supporting Transparent and Open Research Exchange and Engagement (STOREE): Heather O’Brien; from UBC Library Digital Initiatives: Tara Stephens-Kyte; from the UBC Learning Exchange: Karen Chiang, Matt Hume, Suzie O’Shea, and Jennifer Rentz; from the UBC Public Humanities Hub: Sydney Lines, Heidi Rennert, and Mary Chapman; from the UBC School of Information: Kevin Day; from the University of Guelph Research Innovation Office: Valerie Hruska; and from UBC’s Faculty of Education, Gerald Tembrevilla.

We would like to recognize the researchers and authors who participated in this project: Stephanie Allen, Geoff Bardwell, Brittany Barker, Jade Boyd, Juliane Collard, Aaron Goodman, Elke Krasny, Jing Li, Jeff Masuda, Scott Neufeld, Michelle Olding, Surita Parashar, Suzanne Smythe, Will Valley, Nicole Yakashiro, and Miu Chung Yan.

We would like to thank two anonymous reviewers for their careful reading and constructive suggestions on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

Lastly, we would like to thank ASTU 100 students for their thoughtful participation in this project.

References

Akena, F.A. (2012). Critical analysis of the production of Western knowledge and its implications for Indigenous knowledge and decolonization. Journal of Black Studies, 43(6), 599–619. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23414661

Alder-Kassner, L., Crooks, R. & Watters, A. (Eds). (1997). Writing the community: Concepts and models for service-learning in composition. American Association for Higher Education.

American Library Association. (2015). Framework for information literacy in higher education. http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework

Asghar, M., & Rowe, N. (2017). Reciprocity and critical reflection as the key to social justice in service learning: A case study. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 54(2), 117–125. http://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2016.1273788

Ashley, F (2021). Accounting for research fatigue in research ethics. Bioethics, 35(3), 270–276. http://doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12829

Baldwin, D. L. (2021). In the shadow of the ivory tower: How universities are plundering our cities. New York, NY: Bold Type Books.

Bonnet, J.L., Cordell, S.A., Cordell, J., Duque, G.J., MacKintosh, P.J., & Peters, A. (2013). The apprentice researcher: Using undergraduate researchers’ personal essays to shape instruction and services. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 13(1), 37–59. http://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2013.0007

Bortolin, K. (2011). Serving ourselves: How the discourse on community engagement privileges the university over the community. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 18(1), 49–58. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.3239521.0018.104

Boyer, E. L. (1997). Scholarship reconsidered: Priorities of the professoriate (1st ed.). Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. (2022, September 30). The Elective Classification for Community Engagement. Retrieved October 23, 2022, from https://carnegieelectiveclassifications.org/the-2024-elective-classification-for-community-engagement/

City of Vancouver. (2013). Downtown Eastside Local Area Profile. https://vancouver.ca/files/cov/profile-dtes-local-area-2013.pdf

Dean, A. (2019). Colonialism, neoliberalism, and university-community engagement: What sorts of encounters with difference are our institutions prioritizing? In A. Dean, J. L. Johnson, & S. Luhmann (Eds.), Feminist praxis revisited: Critical reflections on university-community engagement. (pp. 23–38). Wilfred Laurier University Press.

Deans, T. (2000). Writing partnerships: Service-learning in composition. National Council of Teachers of English.

Deloria Jr., V. & Wildcat, D. (2003). Power and place: Indian education in America. American Indian Graduate Center.

Dostilio, L., Brackmann, S., Edwards, K., Harrison, B., Kliewer, B., & Clayton, P. H. (2012). Reciprocity: Saying what we mean and meaning what we say. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 19(1), 17–32. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.3239521.0019.102

Dunlap, J., and Lowenthal, P. (2016). Getting graphic about infographics: Design lessons learned from popular infographics. Journal of Visual Literacy, 35(1), 42–59.

Ferguson, G., Ardiles, P., Sidhu, J., & Ravikularam, J. (2021). Strengthening community -engaged learning and teaching at SFU: Summary report November 2021. Office of Community Engagement, Simon Fraser University. https://www.sfu.ca/content/dam/sfu/communityengagement/Documents/CETL%20Report-2021-12-14.pdf

Gaudry, A. J. P. (2011). Insurgent research. Wicazo Sa Review, 26(1), 113–136. http://doi.org/10.5749/wicazosareview.26.1.0113

Getto, G., & McCunney, D. (2016). Moving from traditional to critical service learning: Reflexivity, reciprocity, and place. In A. S. Tinkler, B. E. Tinkler, V. M. Jagla, & J. Strait (Eds.), Service-learning to advance social justice in a time of radical inequality (pp. 347–358). Information Age.

Giltrow, J., Gooding, R., & Burgoyne, D. (2021). Academic Writing: An Introduction. 4th Ed. Broadview Press.

Harrison, B., & Clayton, P. H. (2012). Reciprocity as a threshold concept for faculty who are learning to teach with service-learning. Journal of Faculty Development, 26(3), 29–33.

Kovach, M. (2009). “Doing Indigenous Research in a Good Way—Ethics and Reciprocity. In Indigenous Research Methodologies: Characteristics, Conversations, and Contexts. (pp. 141–155.) University of Toronto Press.

Linden, I.A., Mar, M.Y., Werker, G.R., Jang, K., & Krausz, M. (2013). Research on a vulnerable neighbourhood – the Vancouver Downtown Eastside from 2001 to 2011. Journal of Urban Health, 90(3), 559–573.

McCauley, A. & Towle, A. (2022). The Making Research Accessible Initiative: A case study in community engagement and collaboration. Partnership. The Canadian Journal of Library and Information Practice and Research, 17(1). http://doi.org/10.21083/partnership.v11i1.6454

McSween-Cadieux, E., Chabot, C., Fillol, A., Saha, T., & Dagenais, C. (2021). Use of infographics as a health-related knowledge translation tool: Protocol for a scoping review. BMJ Open, 11(6), e046117–e046117. http://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046117

Mitchell, T.D. (2008). Traditional vs. critical service-learning: Engaging the literature to differentiate two models. Michigan Journal of Community-Service Learning, 14(2), 50–65. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.3239521.0014.205

Miller-Young, J., Dean, Y.; Rathburn, M., Pettit, J., Underwood, M., Gleeson, J., Lexier, R., Calvert, V., (2015). Decoding ourselves: An inquiry into faculty learning about reciprocity in service-learning. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 22(1), 32–47.

Murray, S. (2021). Accessible research dissemination through data visualization: Promising practices for the creation of infographics. http://doi.org/10.14288/1.0402361

O’Brien, H., De Forest, H., McCauley, A., Sinammon, L., & Smythe, S. (2020). Reconfiguring knowledge ecosystems: Librarians and adult literacy educators in knowledge exchange work. Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement, 26(2), 29–45. https://openjournals.libs.uga.edu/jheoe/article/view/2471

Reale, M. (2016). Becoming an embedded librarian: making connections in the classroom. ALA Editions.

Richardson, L. (2020, April 14). When Crises Collide: COVID-19 and Overdose in the Downtown Eastside. UBC News. https://research.ubc.ca/when-crises-collide-covid-19-and-overdose-downtown-eastside

Saltmarsh, J., Hartley, M., & Clayton, P. H. (2009). Democratic engagement white paper. New England Resource Center for Higher Education.

Shaxson, L., Bielak, A., Ahmed, I., Brien, D., Conant, B., Fisher, C., & Phipps, D. (2012). Expanding our understanding of K*(KT, KE, KTT, KMb, KB, KM, etc.): A concept paper emerging from the K* conference held in UNU-INWEH Hamilton, ON. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235434226_Shaxon_et_al_2012_K_concept_paper_Expanding_our_understanding_of_K_KT_KE_KTT_KMb_KB_KM_etc

Smith, L.T. (2013). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and Indigenous peoples. Zed Books Ltd.

Thoma, B., Murray, H., Huang, S. Y. M., Milne, W. K., Martin, L. J., Bond, C. M., Mohindra, R., Chin, A., Yeh, C. H., Sanderson, W. B., & Chan, T. M. (2018). The impact of social media promotion with infographics and podcasts on research dissemination and readership. Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine, 20(2), 300–306. http://doi.org/10.1017/cem.2017.394

Towle, A., & Leahy, K. (2016). The Learning Exchange: A shared space for the University of British Columbia and Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside communities. Metropolitan Universities, 27(3), 67–83. https://journals.iupui.edu/index.php/muj/article/view/21372

Tuck, E., & Yang, K. W. (2014). R-words: Refusing research. In D. Paris & M. T. Winn (Eds.), Humanizing research: Decolonizing qualitative inquiry with youth and communities (pp. 223–247). SAGE Publications. http://doi.org/10.4135/9781544329611.

Tuck, E. [@tuckeve]. (2019, May 1). I have spent last months traveling + visiting with members of Anishinaabe, Haudenosaunee, Métis, Cree, Dene, Yukon, and Inuit Nations + communities [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/tuckeve/status/1123543935610228736.

Vincent, C. S., Lynch, C., Lefker, J., & Awkward, R. J. (2021). Critically engaged civic learning: A comprehensive restructuring of service-learning approaches. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 27(2), 107–128. http://doi.org/10.3998/mjcsloa.3239521.0027.205

Weerts, D. & Sandmann, L. (2010). Community engagement and boundary-spanning roles at research universities. Journal of Higher Education, 81(6), 632–657.

Wollschleger, J., Killian, M., & Prewitt, K. (2020). Rethinking service learning: Reciprocity and power dynamics in community engagement. Journal of Community Engagement and Higher Education, 12(1), 7–15.

Yee, J. A., Tong, K., Tao, M., Le, Q., Le, V., Doan, P., & Villanueva, A. (2021). Sparking a commitment to social justice in Asian American studies. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 27(1), 59–92. http://doi.org/10.3998/mjcsloa.3239521.0027.104

Zlotkowski, E. (Ed.). (2002). Service-learning and the first-year experience: Preparing students for personal success and civic responsibility. The first-year experience monograph series. National Resource Center for The First-Year Experience and Students in Transition, University of South Carolina.

Authors Note

Evan Mauro https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6822-6335 University of British Columbia

Kirby Manià https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5839-053X University of British Columbia

Nick Ubels https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6487-7491 Canadian Coalition for Seniors’ Mental Health

Heather Holroyd https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8223-1053 BC Centre on Substance Use

Angela Towle https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7164-0959 University of British Columbia

Shannon Murray https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4273-1325 University Canada West

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Evan Mauro, evan.mauro@ubc.ca

Appendix A

Land Acknowledgement

We recognize that our work at the UBC Vancouver campus and the UBC Learning Exchange takes place on the unceded, traditional, and continuously occupied territories of the xʷməθkwəy̓əm (Musqueam), Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish), and Səl̓ílwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) peoples. We are grateful for the opportunity to work alongside these communities to disrupt extractive research practices and transform this harmful legacy into a more reciprocal, equitable culture of knowledge exchange.

Appendix B

Who We Are

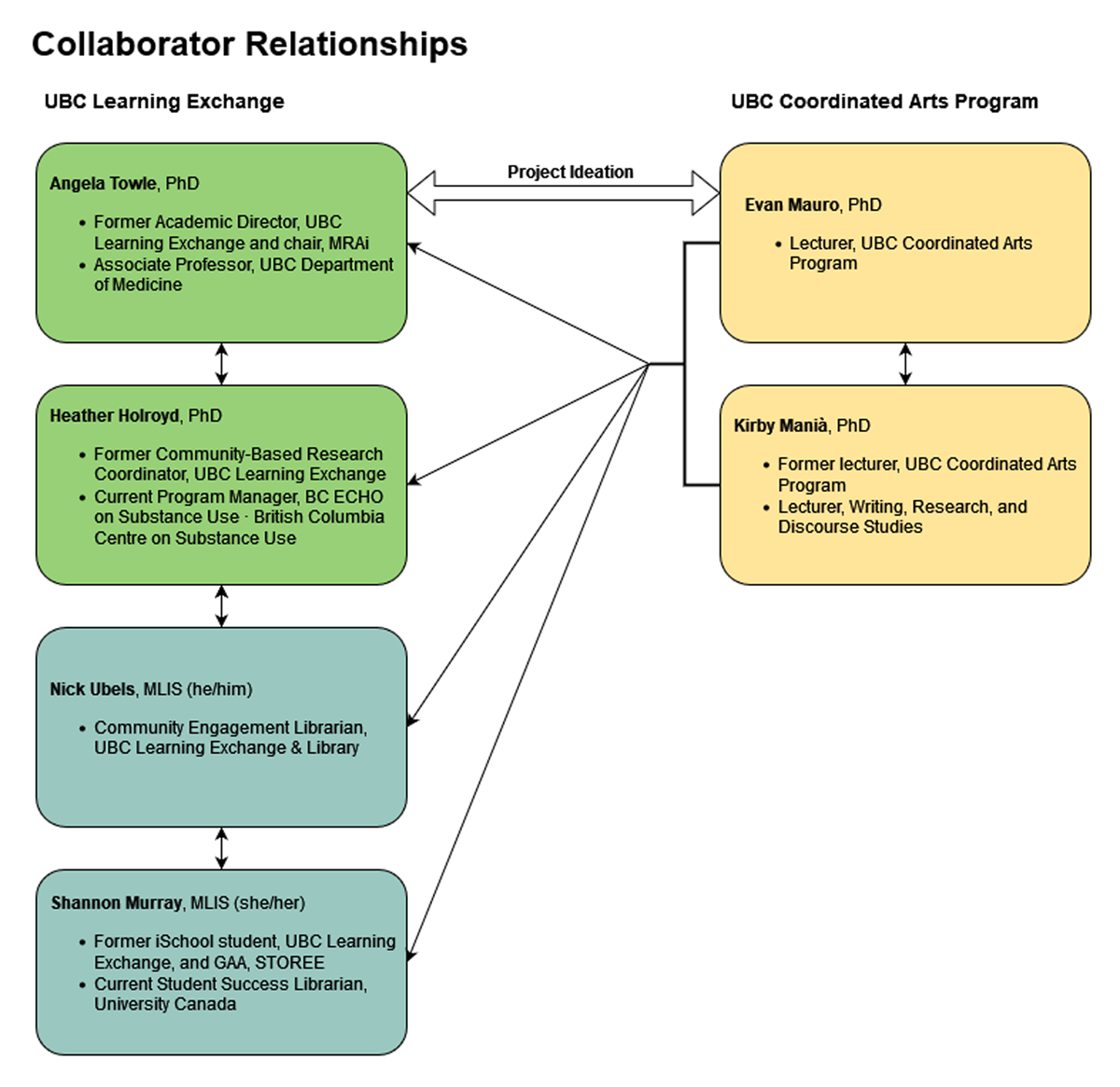

To situate our work on this project and the perspectives included in this paper, we refer to Figure 1. This diagram draws inspiration from Yee et al.’s (2021) paper and summarizes our academic backgrounds and working relationships.

Collaborator relationships

None of the paper’s authors are DTES residents. We are all also immigrants and settlers. We acknowledge the varying degrees of privilege we enjoy. To mitigate the limits in our lived experience, we humbly, deliberately, and respectively seek community perspectives to guide the focus and shape of our work in the DTES. The project has been designed with the intention of avoiding extractive and destructive research practices and to encourage constructive and collaborative methods of knowledge creation and transfer with vulnerable communities.

Appendix C

Sample ASTU 100 student created infographics

This infographic is based on the following article: Olding, M., Hayashi, K., Pearce, L., Bingham, B., Buchholz, M., Gregg, D., Hamm, D., Shaver, L., McKendry, R., Barrios, R., Nosyk, B. (2018). Developing a patient-reported experience questionnaire with and for people who use drugs: A community engagement process in Vancouver’s downtown eastside. The International Journal of Drug Policy, 59, 16–23. This infographic was created in the first year of the partnership.

This infographic is based on the following article: Barker, B., Sedgemore, K., Tourangeau, M., Lagimodiere, L., Milloy, J., Dong, H., Hayashi, K.,Shoveller, J., Kerr, T., & DeBeck, K. (2019). Intergenerational trauma: The relationship between residential schools and the child welfare system among young people who use drugs in Vancouver, Canada. Journal of Adolescent Health, 65 (2), 248–54. This infographic was created in the second year of the partnership.

This infographic is based on the following article: Boyd, J., Cunningham, D., Anderson, S., & Kerr, T. (2016). Supportive housing and surveillance. International Journal of Drug Policy, 34, 72–79. This infographic was created in the third year of the partnership.

This infographic is based on the following article: Yakashiro, N. (2021). “Powell street is dead”: Nikkei loss, commemoration, and representations of place in the settler colonial city. Urban History Review, 48(2), 32–55. This infographic was created in the third year of the partnership.

Appendix D

Community focus group questions (from Murray 2021, p. 18)

The following questions were used as a general guideline to structure each focus group session:

-

Quick-Fire Comparison Activity

Which infographic is the most aesthetically-pleasing?

Which infographic is the most eye-catching?

Which infographic has the most logical and clear layout?

Which infographic most effectively incorporates visual elements into its design?

-

Individual Infographic Analysis

How would you describe the tone of the graphic? Specifically, in regard to the written text / language?

How do the visual elements either take away, or add, to the infographic? Or, do they have little to do with your understanding of the information?

-

How would you describe the infographic’s design?

Design = layout, typeface, color palette.

Would you say that, overall, the infographic helped you in understanding the research article / material?

-

Wrap-up Questions

What is your overall impression of these infographics?

In your personal opinion, do you think that infographics are a useful tool in making research more accessible?

Would you like to see more infographics added to the RAP?

Any additional feedback or comments?

Appendix E

Student survey, April 2020

How would you describe your experience with the Making Research Accessible Initiative?

What was something you learned about yourself through this experience? Were there any specific experiences/skills you brought to the course that the CEL component spoke to?

How did the CEL experience inform your learning in this course?

Did you make public research summaries of scholarly articles (eg. bullet point summary, infographic, or annotated bibliography? If yes, was this a worthwhile task?

How do you define “advocacy”?

After taking this course, how do you feel about doing advocacy as part of coursework?

In what way (if any) did the Research 101 Manifesto and your public research assignment inform your learning in the course?

In what way (if any) did the course change your perspectives on law and justice?

Has this experience altered your personal/professional goals in any way?

What was the most impactful part of the CEL experience for you?

If you could change anything about your CEL experience, what would it be?

Would you consider taking a course with a CEL component again?