Introduction

Even when controlling for social determinants of health such as insurance status, income, age, and pre-existing conditions, numerous studies demonstrate racial and ethnic disparities in health care for minority populations.1–3 Patients who identify as underrepresented minorities (URM) and have physicians with racial concordance report better satisfaction, compliance, and health outcomes than those who do not.4–6 Despite the increasing diversity of both the national population and the population of matriculating medical students, only 7% of academic surgeons in the United States identify as URM, and there has been no change in this number from 2005 to 2018.7

Increasingly, surgery departments across the United States are implementing strategies to diversify their residency classes.8 However, residency programs show differing rates of success. Studies regarding residency program rank lists, in general, show that overall location and program factors (eg, morale and clinical experience) are the most influential factors in rank list for all applicants.9,10 Women and URMs are more likely also to prioritize family and diversity factors.9,10 However, factors specific to URM applicants pursuing general surgery programs remain unknown and understudied.11

To increase URM recruitment and retention in surgical disciplines, programs must have a deeper understanding of factors important to URM candidates applying into general surgery residency. In this study, we explored factors considered by URM in creating their National Resident Matching Program (NRMP, or Match) rank order list for general surgery residency. We hope these results yield opportunities for surgical residency programs to strengthen their cohorts by improving diversity and representation in pursuit of racial justice and health equity. Specifically, we hypothesize that URM participants will prioritize factors related to diversity and inclusion efforts.

Methods

Participants

We employed a mixed method approach using an online survey and semi-structured interviews developed through focus group engagement and literature review. Participants were eligible for the survey if they matched during the 2020 cycle into a US general surgery residency program regardless of URM status. URM status was self-reported. Surveys and interviews were conducted from June 2020 to July 2020 prior to matriculation at any US general surgery residency program. Interview participants were exclusively URM, defined as Black/African American, Hispanic/Latino, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and/or Native American. Participants were ineligible if affiliated with a Historically Black College/University because these programs have traditionally accepted more URM residents than other programs. This study was exempted by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board (HUM00183224).

Survey

An electronic 18-question survey was distributed to URM and non-URM general surgery interns through targeted social media platforms and emails to determine important factors for ranking residencies. Both the survey questions and the interview guide were developed by identifying important factors and themes for ranking residency programs via (1) a focus group of current URM medical students and faculty at the University of Michigan and (2) an extensive literature review from PubMed searches from 2004 to 2020 combining the keywords “URM,” “general surgery,” and “residency.” Surveys evaluated 18 pre-determined factors contributing to rank lists focused on (1) program diversity features, (2) educational factors, (3) prior and anticipated experiences, and (4) lifestyle factors. Participants were provided two optional write-in factors if they wanted to report a factor not part of the 18 pre-determined factors (Table 1). Differences in survey responses were evaluated using Mann-Whitney U tests with an alpha of 0.05.

Survey Questions

Yes/No |

Black or African American Native American or Alaska Native Asian Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander White Hispanic or Latino Other Prefer not to answer |

Male Female Transgender male Transgender female Genderfluid Nonbinary Other Prefer not to answer |

Yes No Prefer not to answer |

Single/never married With significant other Married/remarried Separated Divorced Widowed Prefer not to answer |

Yes No Prefer not to answer |

20-24 25-29 30-34 35-39 40-44 45+ Prefer not to answer |

Yes No Prefer not to answer |

Yes No Prefer not to answer |

Categorical Preliminary-Undesignated Preliminary-Designated Prefer not to answer |

Proximity to family and/or friends Diversity of residents Diversity of faculty Diversity of patient population Job opportunities for spouse or significant other Geographic location Academic reputation Program size Program benefits and finances Post-graduate job or fellowship opportunities Formal mentorship program opportunities at program Political climate in location of program The feeling of being wanted at program Diversity and inclusion statements by program Anticipated clinical experience Perceived morale of residents Revisit opportunities Department support of resident-led initiatives Another factor (Please write in) Another factor (Please write in) |

|

Interview

A snowball sampling technique was used to identify incoming URM students in the 2020 Match class to complete interviews (Table 2). URM interns were interviewed through semi-structured telephone interviews. We chose to interview only URM, as we aimed to highlight their voices with this study. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, independently coded by two researchers, and analyzed for themes.

Semi-Structured Interview Guide

Construct/concepts |

Questions |

|---|---|

Rapport building |

|

Applicant features |

We will be asking personal questions. You may decline to answer them.

|

Program-specific characteristics |

Tell me about your residency application experience.

Can you tell me about your interview day at the program you matched at?

|

|

What factors signaled to you that a place would be a good place to train as a URM?

|

|

Individual and support factors |

What are your long-term goals? How does the program you matched in factor into those goals?

|

Signing out |

Can you recommend additional recently matched URM residents to interview next?

|

Bold questions were asked of all respondents. Other questions were suggestions for guiding conversation according to relevant themes.

Results

Survey Results

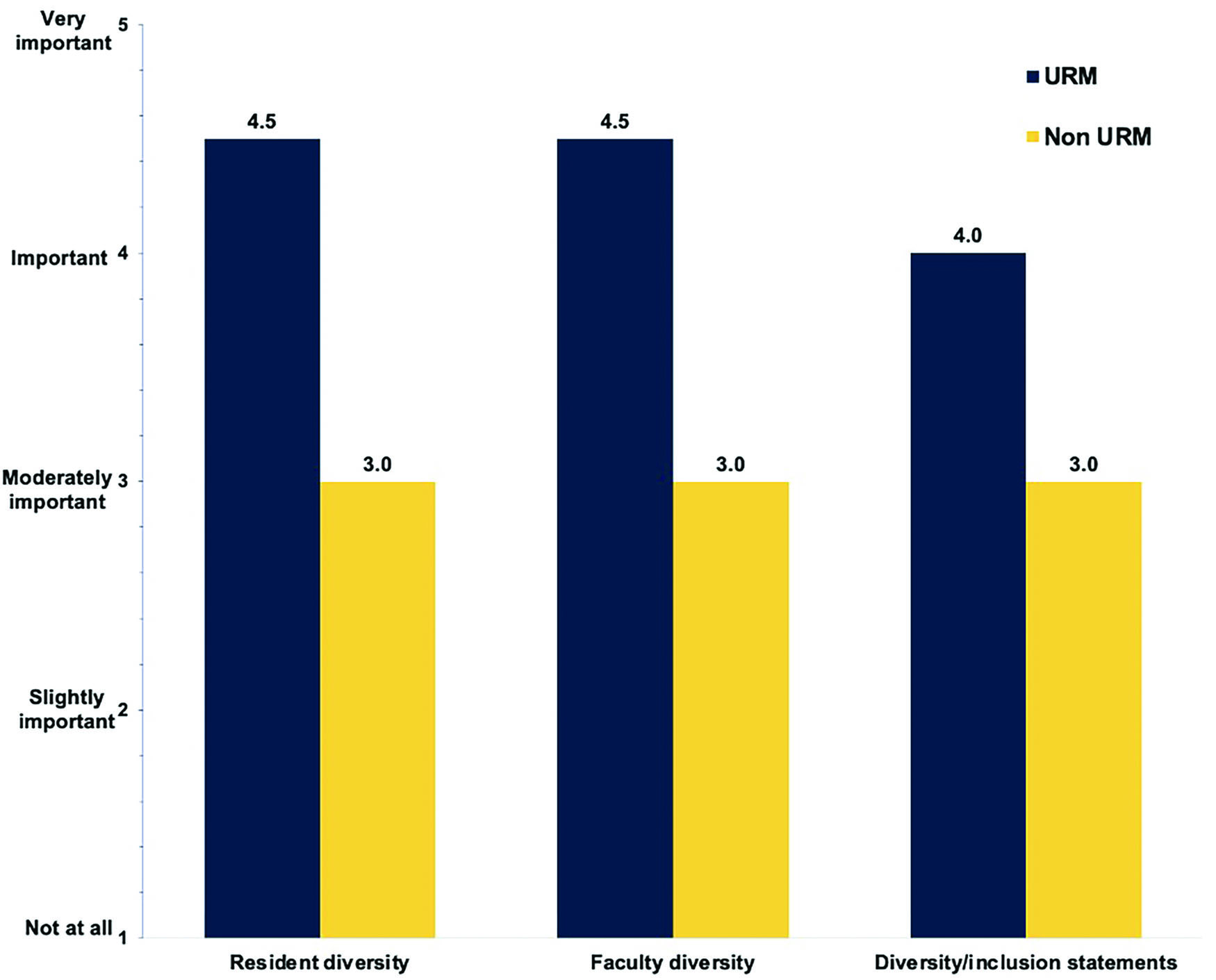

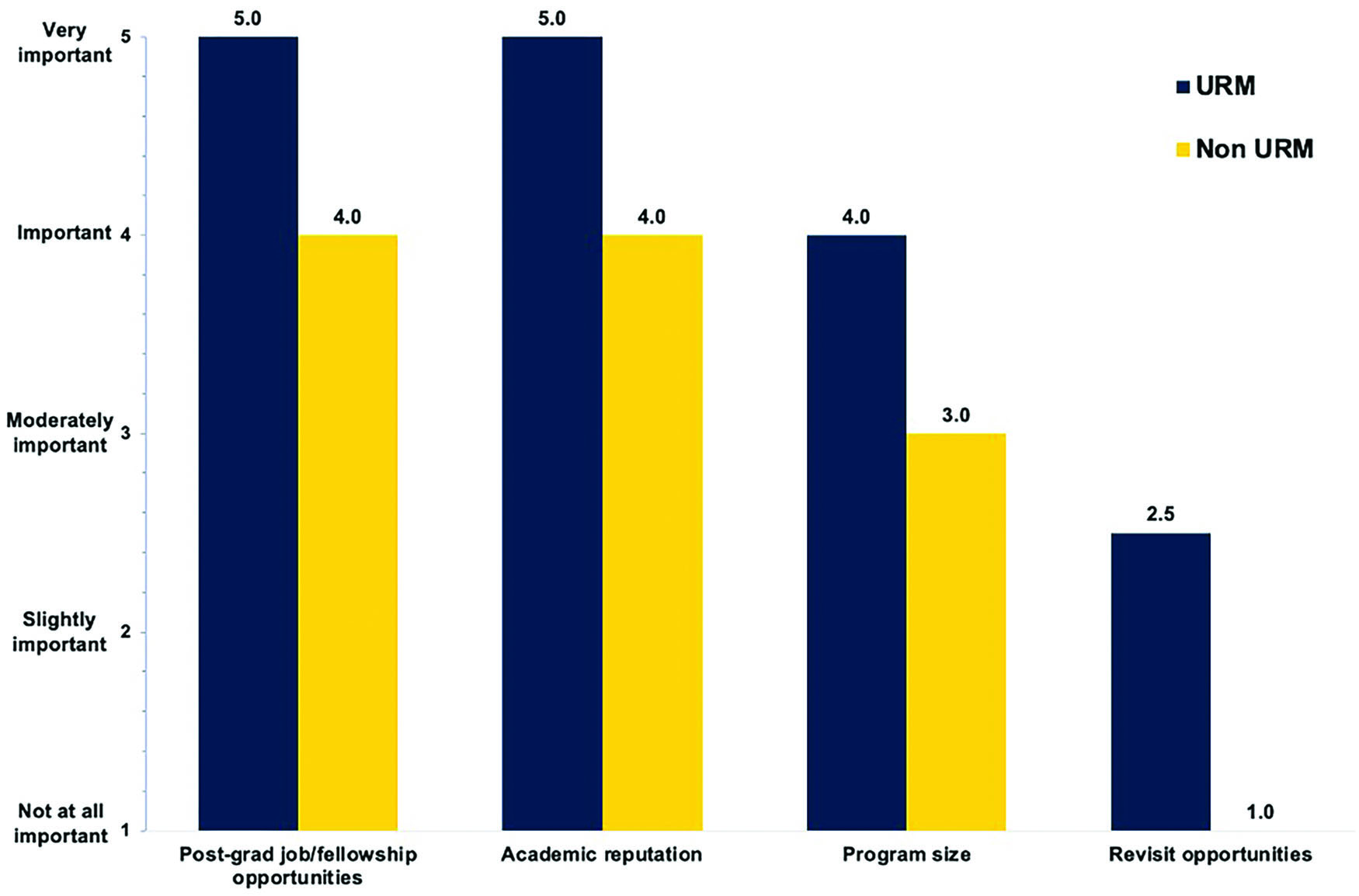

Sixty-four students (median age 25–29, 67% female; Table 3) out of 993 total students who matched to general surgery residency programs in the NRMP in 2020 completed the survey.12 There were 22 URM respondents, 12 of whom self-identified as Black or African American, 7 as Hispanic or Latino, 2 as Pacific Islander, and 1 as Native American or Alaska Native (Table 3). Of the 18 factors contributing to general surgery residency rank, post-graduate job or fellowship opportunities, the feeling of being wanted at the program, anticipated clinical experience, and perceived morale of residents were ranked highest among all participants. Of the list, URM residents ranked post-graduate opportunities and perceived morale of residents the highest of all factors. URM participants ranked the importance of factors related to diversity (diversity/inclusion statements, resident/faculty diversity), education (post-graduate/fellowship opportunities, academic reputation, program size, revisit opportunities), experiences (mentorship, feeling of being wanted, support of resident-led initiatives), and lifestyle (benefits/finances, spouse job opportunities, political climate) higher than did non-URM participants (p<0.05; Figure 1). Additionally, URM participants ranked certain program educational factors—post-graduate opportunities (p<0.05), academic reputation (p<0.05), program size (p<0.05), and revisit opportunities after interview day (p<0.05)—higher than did non-URM participants (Figure 2).

Survey Respondents’ Demographics

All respondents (n=64) |

URM respondents (n=22) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity — n (%) | ||

| White | 28 (44%) | 12 (55%) |

| Asian | 13 (20%) | 7 (32%) |

| Black or African American | 12 (19%) | 2 (9%) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 7 (11%) | 1 (5%) |

| Pacific Islander | 2 (3%) | |

| Native American or Alaska Native | 1 (2%) | |

| No answer | 1 (2%) | |

| Gender — n (%)* | ||

| Female | 43 (67%) | 17 (77%) |

| Male | 21 (33%) | 5 (23%) |

| International medical graduate — n (%) | ||

| Yes | 7 (11%) | 3 (14%) |

| No | 57 (89%) | 19 (86%) |

| Marital status — n (%) | ||

| Single | 45 (70%) | 17 (77%) |

| Married | 9 (14%) | 4 (18%) |

| With significant other | 6 (9%) | 0 (0%) |

| Divorced | 3 (5%) | 1 (5%) |

| No answer | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) |

| Have children — n (%) | ||

| Yes | 59 (92%) | 19 (86%) |

| No | 4 (6%) | 3 (14%) |

| No answer | 1 (2%) | |

| Age — n (%) | ||

| 20–24 | 1 (2%) | 1 (5%) |

| 25–29 | 51 (80%) | 17 (77%) |

| 30–34 | 7 (11%) | 2 (9%) |

| 35–39 | 4 (6%) | 2 (9%) |

| No answer | 1 (2%) | |

| First generation — n (%) | ||

| Yes | 11 (17%) | 6 (27%) |

| No | 53 (47%) | 16 (73%) |

| Low income — n (%) | ||

| Yes | 19 (30%) | 12 (55%) |

| No | 43 (67%) | 9 (41%) |

| No answer | 2 (3%) | 1 (5%) |

| Residency position | ||

| Categorical | 51 (80%) | 17 (77%) |

| Prelim-Undesignated | 10 (16%) | 4 (18%) |

| Prelim-Designated | 3 (5%) | 1 (1%) |

There were no respondents who self-identified as transgender, genderfluid, nonbinary, or other.

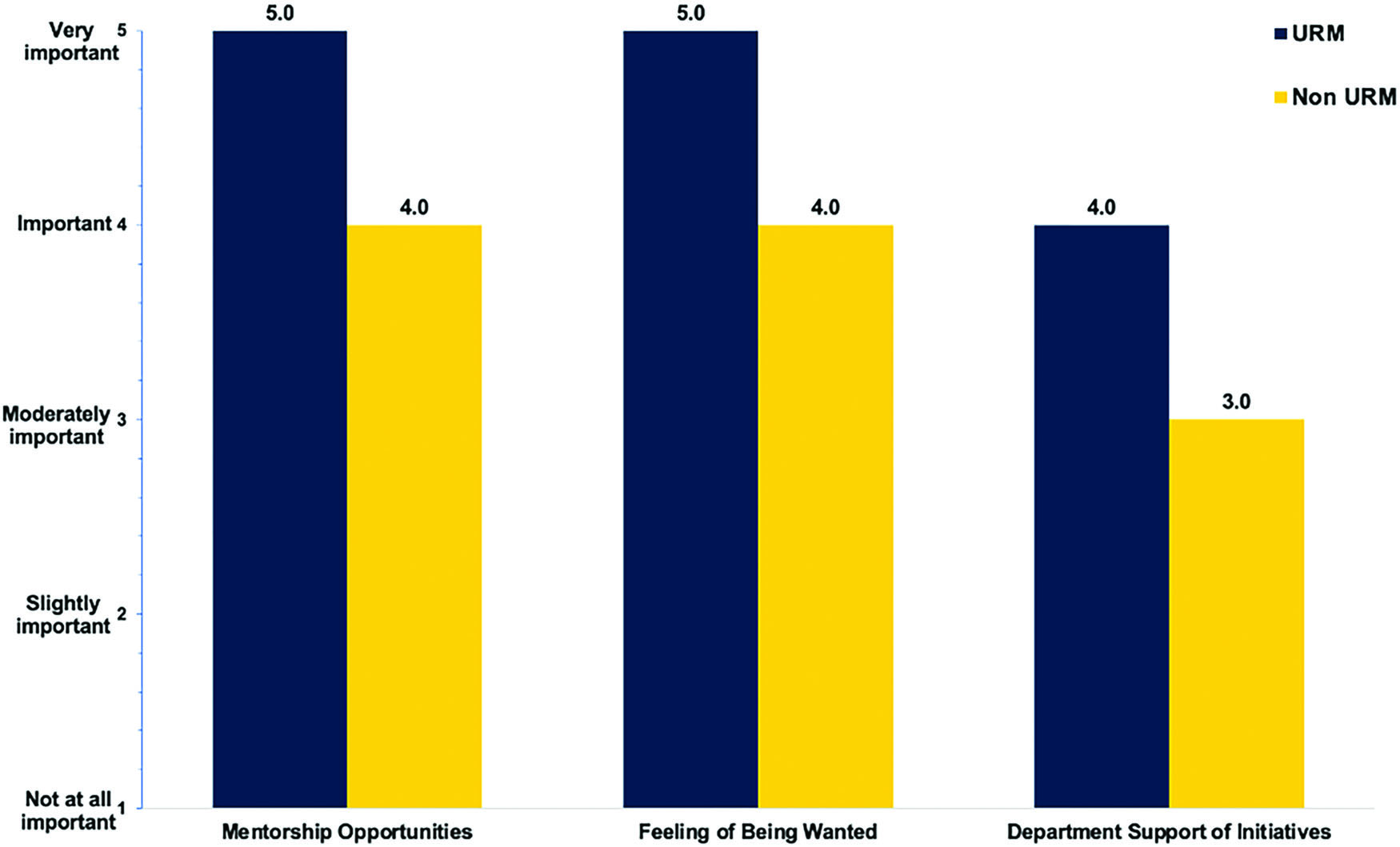

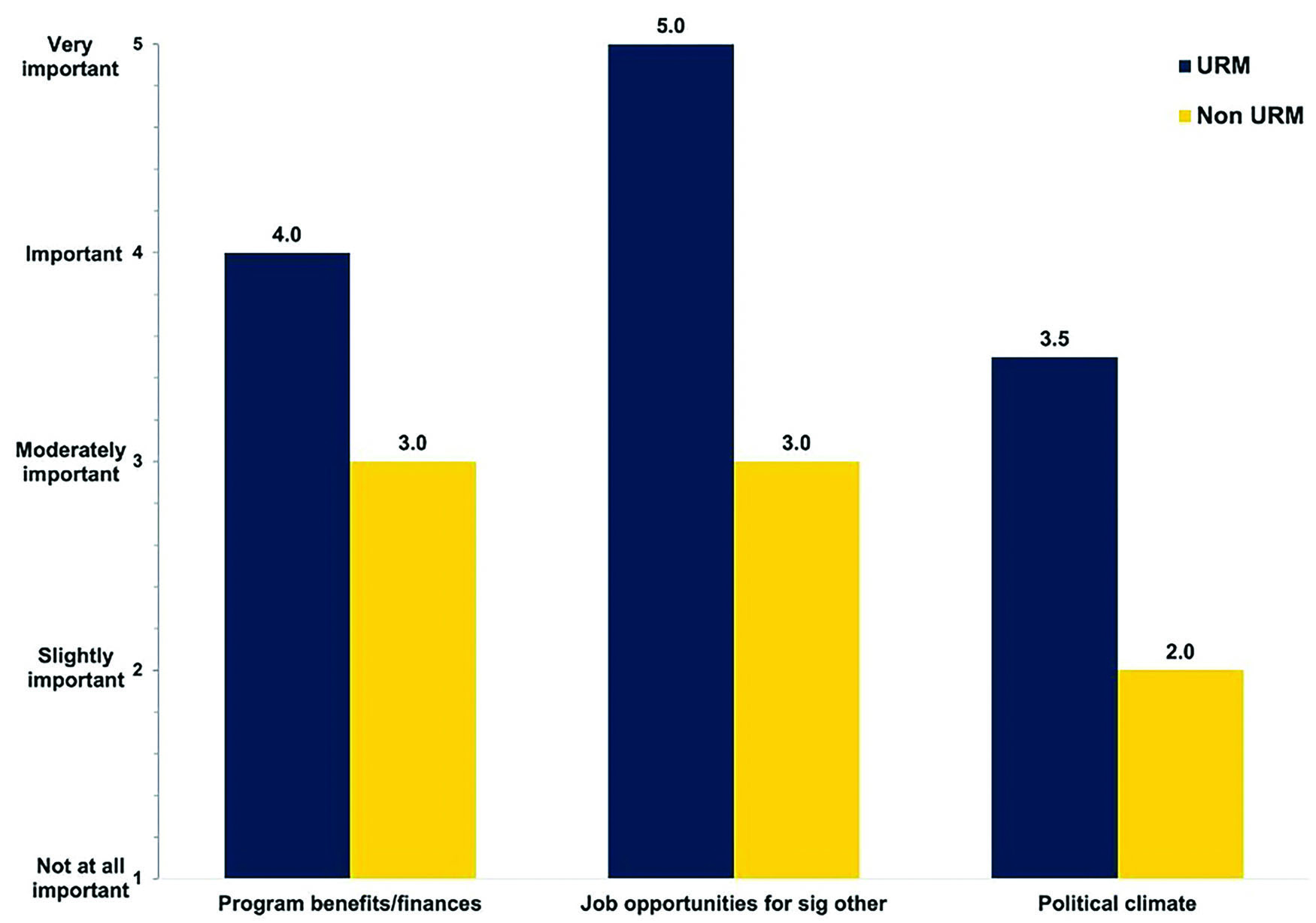

URM participants prioritized a supportive learning environment during residency more than did their non-URM peers. They prioritized factors such as formal mentorship opportunities (p<0.001), the feeling of being wanted (p<0.05), and department support of resident-led initiatives (p<0.05; Figure 3). Similarly, URM participants placed greater emphasis on residency experience outside of academics, such as program benefits and finances (p<0.05), job opportunities for one’s spouse or significant other (p=0.05), and the political climate of the program (p<0.05; Figure 4). Some factors did not differ in importance between URM and non-URM participants. Among these factors were proximity to family, geographic location, anticipated clinical experience, and perceived morale of residents. Overall, URM participants rated all factors higher than did non-URM participants.

Semi-Structured Interview Results

Five URM general surgery interns were interviewed (4 female, 1 male). Four themes emerged with respect to factors influencing rank list order: (1) URM representation in program, (2) program support, (3) active inclusivity efforts, and (4) current URM resident experiences (Table 4). Interview participants consistently expressed not wanting to be the only URM in their residency program. The presence of URM trainees and faculty signaled values of diversity and inclusion. Several participants reported ranking a program lower or not applying at all due to lack of representation among residents and faculty members. Interviewees expressed difficulty assessing the racial and ethnic program diversity. They relied on rosters and faculty photographs to determine representation and used URM visibility on interview day as a proxy. The experiences of current URM residents were factored heavily in the ordering of rank lists.

Identified Themes From Semi-Structured Interviews

Theme |

Definition |

Exemplary quotes |

|---|---|---|

URM representation |

Perception of program’s URM representation |

“I knew that I did not want to be the only Black person in my program. I wanted to be at a program that truly, truly valued diversity and inclusion of all sorts. […] I don’t want to be at a program where I feel like I have to speak on behalf of all Black people because I’m the only Black person there.” (ID 1) “Most programs in general just don’t have a lot of residents that are people of color. [In that case, programs needed to] realize [it] was an issue and it was kind of on their frontline for things that they wanted to address.” (ID 2) “What’s going to happen is I’m going to [be] pulled for every diversity committee that they have, I’m going to get put on it when they want to know the views of a Black person or a person of color. And I just do not want to be a representative for my entire race, or even my gender, for that matter. So honestly, I just kind of looked at class rosters.” (ID 2) |

Program support |

Perception of program support of resident-led goals via tangible resources |

“[The program director] literally stopped me and said, ‘I think you would be a great fit here, and we’d be able to support you. Let me talk to you about some of the resources that we would have available for you to achieve this idea that you have,’ and he literally laid out some stuff for me. […] I left feeling like, well, if I came here, nobody is just smoking mirrors in my face. They’re actually going to help me achieve this goal.” (ID 2) “My co residents or attendings — will call me and say, ‘Hey, I have this Spanish-speaking patient, are you in the hospital? Can you help translate? It’s amazing. It makes me feel so fulfilled.” (ID 5) |

Active inclusivity efforts |

Program has concrete plans to increase diversity and representation and articulates these plans |

“I asked [the program director] very bluntly, ‘what active measures are you guys taking to improve the diversity of your programs?’ He went into this like, very detailed plan of his and I’m an actions speak louder than words type person. […] It wasn’t like it was lip service.” (ID 3) “I looked for the institutions that have black attendings, black fellows, and black residents.” (ID 4) “It was mostly asking those questions like asking the residents, ‘Can you tell me about a time when your program — or you know, whoever, like your program director — stood up for you or changed something when there was an issue?’ I asked that at pretty much every dinner.” (ID 5) |

Current URM resident experiences |

Opinions held by current URM residents at a program heavily influence interviewee’s perception of the program |

“I believe strongly in solidarity with other URMs. Like you want to warn someone if you are hating it and you want to lure people if you’re loving it.” (ID 1) “They actually had a good number of Black residents across their entire residency classes. […] I met a couple at the pre-interview dinner, and then one or two during the interview day, and after my interview, that program director literally sent an email contact and also CC’ed me on introductory emails with other residents of color, which I thought was really, really nice.” (ID 2) “I asked, you know, kind of the tougher questions — just asked [current residents], ‘As a female, have you ever felt like you were treated differently in your training class?’ I asked if they had any mentors either that were female or people of color that they felt comfortable going to.” (ID 5) |

Incoming URM interns sought out programs that shared their values and expressed how they could support them throughout residency and beyond. They looked for programs that actively supported resident-led initiatives by providing resources, encouragement, and assistance in project development. All interviewees weighed the experiences of current URM residents heavily in making their rank lists. Stories and opinions by current URM residents were a significant factor in an interviewee’s perception, both positive and negative, of a program.

Active inclusivity efforts were highlighted across all interviews as critical to evaluating whether a program would be a good place to train as a URM. Though efforts and initiatives were different across programs, incoming interns consistently looked for concrete plans and actions to increase representation and inclusion. Interviewees distinguished whether interest in supporting diversity was genuine by looking for program recognition of diversity issues as important, willingness to discuss issues candidly, and articulation of concrete plans to ameliorate disparities.

Discussion

This study identified several discrete factors that URM interns value in the NRMP rank list process, including (1) diversity factors, (2) active inclusivity efforts, and (3) a supportive learning environment. The demographic distribution of age, race, and other variables in the cohort described in this study is consistent with the distribution for incoming general surgery interns in 2020 as reported by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC).12 Our data align with that of other studies, highlighting that all incoming interns prioritize post-graduate opportunities, anticipated clinical experience, perceived morale of residents, and the feeling of being wanted.9,10 However, our data demonstrate unique factors valued by URM during the rank list process.

First, diversity factors were especially important to URM medical students applying into general surgery. URM interns cited the “diversity tax” as a concern related to the lack of persons of color in a residency program. The diversity tax describes the phenomenon that URM academics are frequently asked to take on additional, uncompensated work to address systemic racism at their institutions, such as serving on diversity committees and mentoring URMs in their field.13 When there are very few URMs in a program, this burden rests on the shoulders of just a few individuals. Understandably, incoming interns did not want to be put in the position of speaking on behalf of their entire race. Facing an academically and clinically rigorous program such as general surgery residency, URM interns unsurprisingly would be hesitant to take this on.

URM general surgery interns reported using visual scans of representation on program websites and on interview day as a proxy for lived values of diversity and inclusion because assessment was otherwise difficult. General surgery programs could be more welcoming to URM applicants through appropriate representation in the faculty ranks and by increasing visibility of diverse faculty on interview day and online. Rather than shying away from issues of diversity, we suggest programs lean into difficult conversations by being intentional, frank, and public with goals to increase representation and diversity of perspective. This approach aligns with URM applicants’ desire to see programs willingly discuss related efforts candidly.

Second, incoming interns also looked for evidence of inclusion initiatives. Several incoming interns expressed that some programs seemed to feel, as one participant put it, “behind on the diversity game” and thus expressed interest in URMs to increase their diversity numbers as opposed to genuinely valuing diverse perspectives. Being told that a program values diversity is not as reassuring to URMs as seeing evidence of action to promote inclusivity because of the risk that a program is a performative ally.14 Programs can signal true allyship in a way that is valuable to URM applicants by funding meaningful initiatives to address self-identified areas for improvement.

Third, the data emphasize that a supportive program environment is highly valued by URM interns. The availability of formal mentorship opportunities was a significant factor in evaluating programs for URM interns. URM interns also looked for programs that would actively support their goals. This support may come in the form of resources such as allocated funding and assistance with project development through goal-specific mentorship or protected time. Several interns noted specific interests within academic surgery and shared examples of their interviewers describing how a particular program could help them achieve goals in their area of interest.

Our data indicate that URM applicants weigh the presence of a visibly diverse and inclusive culture and facilitated mentorship opportunities heavily when making decisions about where to train for general surgery residency. Programs should lean into difficult conversations by being transparent and realistic regarding efforts to increase representation and diversity within their departments. By valuing and allocating resources toward resident-led goals, programs can create an environment that is empowering and inclusive, thus providing a supportive training environment for URM residents. This environment would benefit not only the professional growth and development of URM residents but also the surgery community at-large through diversity of thought and improved patient care.

Our study is not without limitations. One limitation is the number of interviews and surveys completed relative to the number of applicants into general surgery. Distribution was limited to targeting professional social media, mainly what was then known as Twitter. As a result, we were unable to assess response rate. Additionally, given the COVID-19 pandemic, graduating students in the United States may have been in various phases of being recruited earlier to assist with patient care during our study, so there may be a selection bias in participants who had the bandwidth to complete interviews. Similarly, interviewees during this cycle were the last to complete interviews in-person to date. It is possible applicants have different perceptions of programs’ diversity initiatives during in-person versus virtual interviewing. Given that rank lists were submitted prior to the height of the pandemic, it is unlikely the COVID-19 pandemic affected participants’ perspectives throughout the interviewing and recruiting process. Lastly, our findings are mostly applicable to underrepresentation by race and ethnicity given the lack of responses encapsulating experiences of people outside the gender binary. Despite these limitations, we believe that our study provides important, previously unknown information given that currently only 8.9% of general surgery residents self-identify as Black, African American, Hispanic, or Latinx.9 More research is needed on the perspective of program directors and their approach to this issue.

Conclusions

This study indicates that incoming URM general surgery interns weighed several discrete factors more heavily than did incoming non-URM interns in building their Match rank order list. These factors are (1) diversity issues including representation within the department, (2) active inclusivity efforts, and (3) a supportive program environment. To foster a more diverse residency, programs should address these factors directly through (1) elevating minority faculty and making representation a department-wide priority, (2) funding meaningful initiatives to address areas for improvement in the diversity space, and (3) listening to and supporting resident-led goals. These findings are critical for making the field of academic surgery more welcoming to URM applicants. Programs must recognize diversity issues as important; discuss them candidly; and make it a priority to address disparities directly, intentionally, and publicly.

References

1 Xierali IM, Castillo-Page L, Conrad S, Nivet MA. Analyzing physician workforce racial and ethnic composition associations: geographic distribution (part II). Published August 2014. https://www.aamc.org/media/7621/downloadhttps://www.aamc.org/media/7621/download

2 Saha S. Taking diversity seriously: the merits of increasing minority representation in medicine. JAMA Intern Med. 2014; 174(2):291–292. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1273610.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12736

3 Walker KO, Moreno G, Grumbach K. The association among specialty, race, ethnicity, and practice location among California physicians in diverse specialties. J Natl Med Assoc. 2012; 104 (1–2):46–52. doi:10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30126-710.1016/s0027-9684(15)30126-7

4 Cooper-Patrick L, Gallo JJ, Gonzales JJ, et al. Race, gender, and partnership in the patient-physician relationship. JAMA. 1999; 282(6):583–589. doi:10.1001/jama.282.6.58310.1001/jama.282.6.583

5 Alsan M, Garrick O, Graziani GC. Does Diversity Matter for Health? Experimental Evidence from Oakland. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2018. Working Paper 24787. doi:10.3386/w2478710.3386/w24787

6 LaVeist TA, Nuru-Jeter A, Jones KE. The association of doctor-patient race concordance with health services utilization. J Public Health Policy. 2003; 24(3–4):312–323.

7 Valenzuela F, Romero Arenas MA. Underrepresented in surgery: (lack of) diversity in academic surgery faculty. J Surg Res. 2020; 254:170–174. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2020.04.00810.1016/j.jss.2020.04.008

8 Peek ME, Kim KE, Johnson JK, Vela MB. “URM candidates are encouraged to apply”: a national study to identify effective strategies to enhance racial and ethnic faculty diversity in academic departments of medicine. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2013; 88(3):405–412. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e318280d9f910.1097/ACM.0b013e318280d9f9

9 Aagaard EM, Julian K, Dedier J, Soloman I, Tillisch J, Pérez-Stable EJ. Factors affecting medical students’ selection of an internal medicine residency program. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005; 97(9):1264–1270.

10 Phitayakorn R, Macklin EA, Goldsmith J, Weinstein DF. Applicants’ self-reported priorities in selecting a residency program. J Grad Med Educ. 2015; 7(1):21–26. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-14-00142.110.4300/JGME-D-14-00142.1

11 Agawu A, Fahl C, Alexis D, et al. The influence of gender and underrepresented minority status on medical student ranking of residency programs. J Natl Med Assoc. 2019; 111(6):665–673. doi:10.1016/j.jnma.2019.09.00210.1016/j.jnma.2019.09.002

12 The Match: National Residency Matching Program. Charting Outcomes in the Match: Senior Students of U.S. MD Medical Schools — Characteristics of U.S. MD Seniors Who Matched to Their Preferred Specialty in the 2020 Main Residency Match. Published July 2020. Accessed October 5, 2022. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Charting-Outcomes-in-the-Match-2020_MD-Senior_final.pdfhttps://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Charting-Outcomes-in-the-Match-2020_MD-Senior_final.pdf

13 Gewin V. The time tax put on scientists of colour. Nature. 2020; 583(7816):479–481. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-01920-610.1038/d41586-020-01920-6

14 Kalina P. Performative allyship. Tech Soc Sci J. 2020; 11(1):478–481. doi:10.47577/tssj.v11i1.10.47577/tssj.v11i1