In 2021, the Georgia Southern University Libraries received a charge from the President of the University to reduce the libraries’ budget by $300,000 for 2022. The recent professional literature is replete with reports and research addressing causes, consequences, and strategies for conducting collections assessment, much of which focuses on the evaluation of electronic journals and unbundling of Big Deals.1 Of these studies, a significant number focus on canceling resources under crisis conditions, with limited time to assemble and analyze relevant data or stakeholder feedback.2 Also, these studies display diverse methodology, including quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods approaches, of which many of the latter rely on librarian judgment to weigh quantitative and qualitative variables in selection decisions.3 While reviewing this literature we concluded that, like politics, all selection decisions are local. The circumstances of our assessment were no different than the majority of these studies, and neither was our general approach. Confronted with title cancellations under crisis conditions, we amassed as much usage and cost data as we could, identified several Big Deals for unbundling, solicited faculty feedback, did our best to combine these quantitative and qualitative inputs in a principled and equitable manner, and, finally, applied our professional judgment when renewing titles.

We decided that we needed to look at all subscriptions on a title level, so we first built a list of all the libraries’ resources. We then incorporated usage data to rank those resources by cost-per-use and separated each list by subject area. The first phase was to determine which resources we planned to further investigate. We decided that print monographs and other one-time purchases would be removed from consideration for cancellation because we wanted to focus on resources we had an obligation to continue since faculty would be more likely to feel pain if a database or a subscription that they needed was cut. We also decided to retain essential software services and platforms and to exclude them from the assessment process. For example, we excluded our bepress Digital Commons subscription because that would be a very large pain point if it were cut. We also decided to exclude resources not funded by the libraries. Since we only needed to reduce the libraries’ budget, all resources provided through the statewide GALILEO consortium or by other units of the University were excluded from consideration.

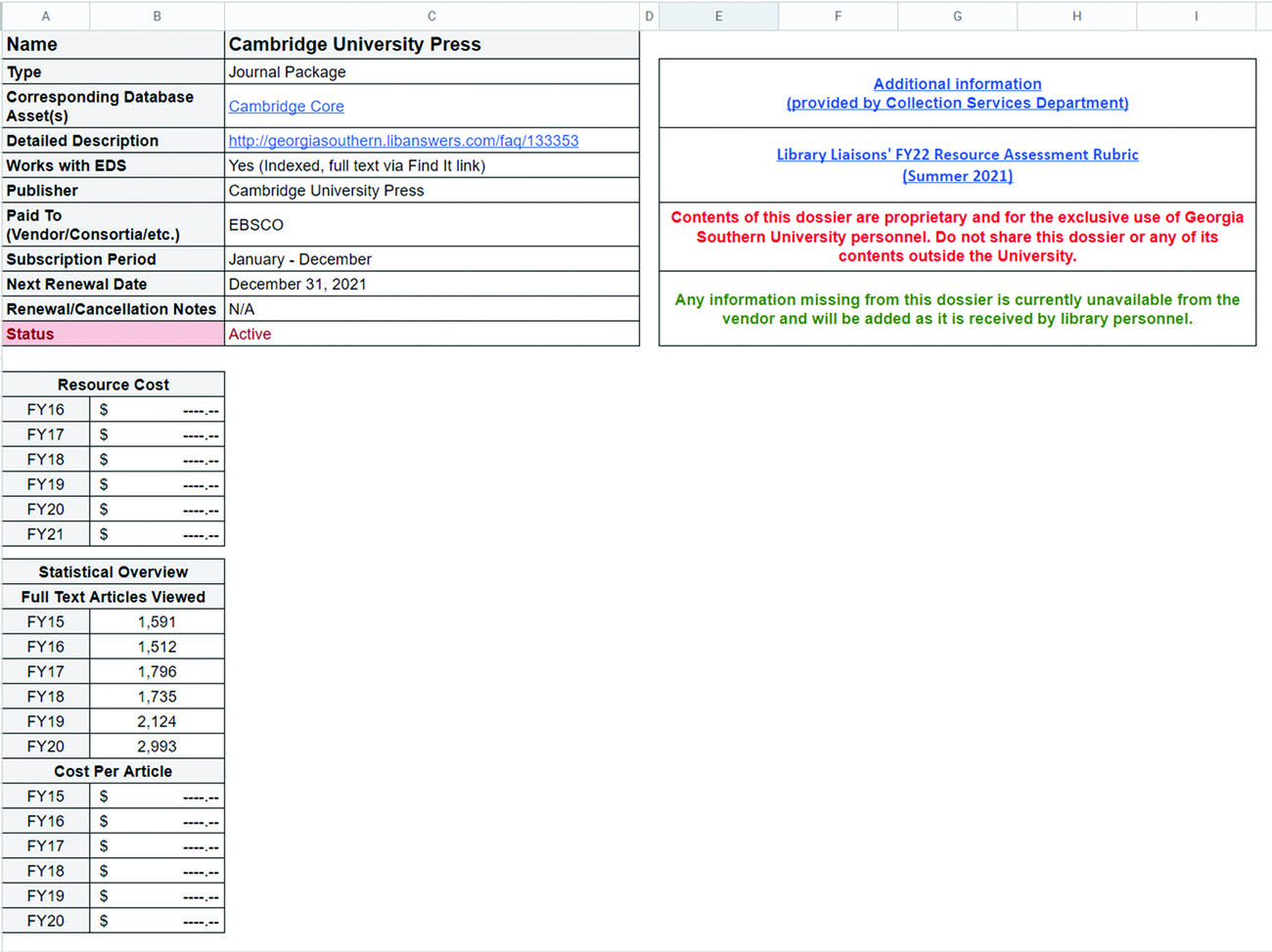

In the next phase, we assembled information about all of the resources that were subject to review. We updated the libraries’ dossiers as our first task. We began creating and maintaining dossiers in 2012 using Google Spreadsheets to compile all of the information about paid resources in one place so that, when library faculty were asked to recommend whether a resource should be renewed or canceled, the information they would need to make decisions could be easily shared among colleagues. The dossiers originally were one-page spreadsheets containing information such as the resource title, the name of the vendor who provides the resource, the subscription period, the next renewal date, historical pricing, and a summary of whatever statistics are available for the resource over time. An example of a dossier can be found in Figure 1.

As we updated the dossiers, we added more sections to these documents to include the information we were collecting as a result of our Assessment project. The original content of the dossiers became the cover page, and additional links and sheets were added to each dossier over the course of the project. These additions are described in the following paragraphs. We also decided to include the average cost-per-use for each title on the dossier instead of relying on the annual costs-per-use platform-level statistics we had used in previous years. We wanted to use the most recent data, but fiscal year (FY) 2020 was an atypical year for our students and faculty due to the COVID-19 pandemic. We instead decided to calculate the average cost-per-use by averaging the annual, journal title-level statistics for FY2018, FY2019, and FY2020 because we felt that user behavior in FY2018 and FY2019 was more indicative of the actual use of library materials.

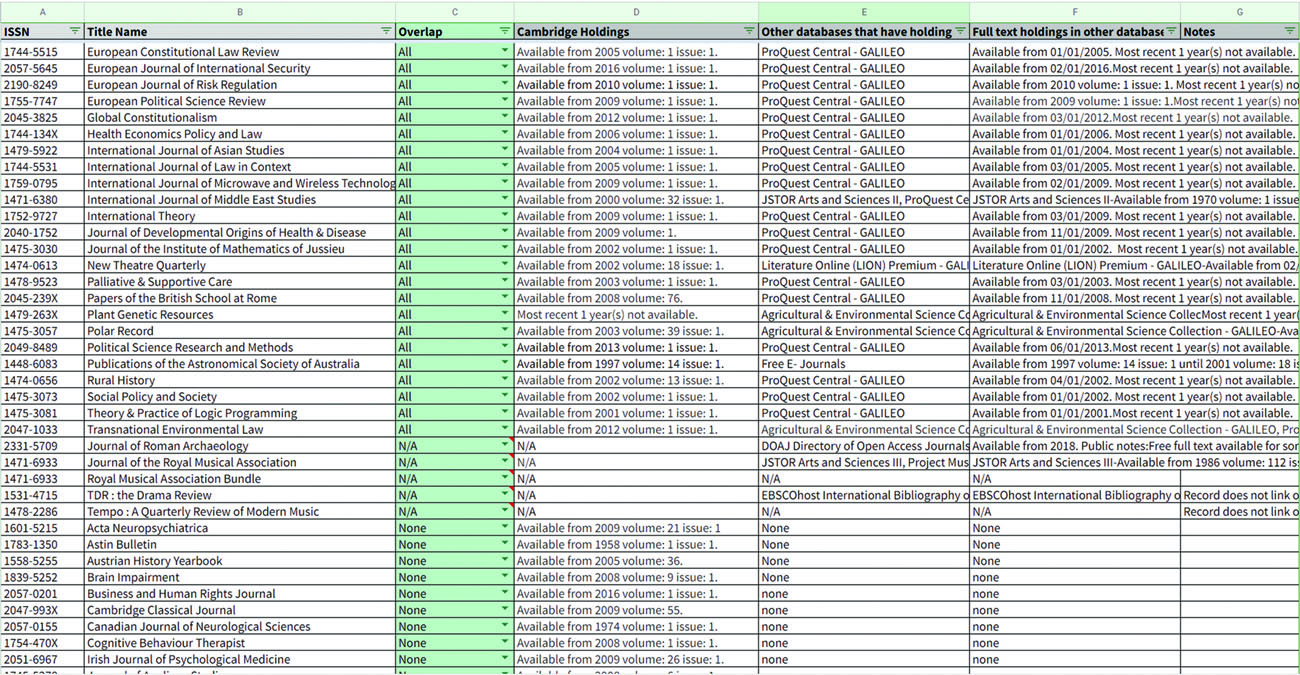

Next, we performed overlap analyses of all our packages and databases on a title level. An example of the documents we created to record the raw overlap analysis data for each resource is shown in Figure 2. We added these documents as sheets to each resource’s dossier. During the overlap analysis process, each journal that was included in a package or a database was examined to determine if and where else it was available electronically. If the title is unique, there will not be any overlap in any other package or database. Any title that shows an overlap response of “None” is not available in any other package or database. If another source such as an aggregator database provides access to a title but does not have the same issue holdings as are available through the journal package being evaluated, the title is labelled as “Partial.” A title that is available in an aggregator database but embargoed would also be categorized as partial.

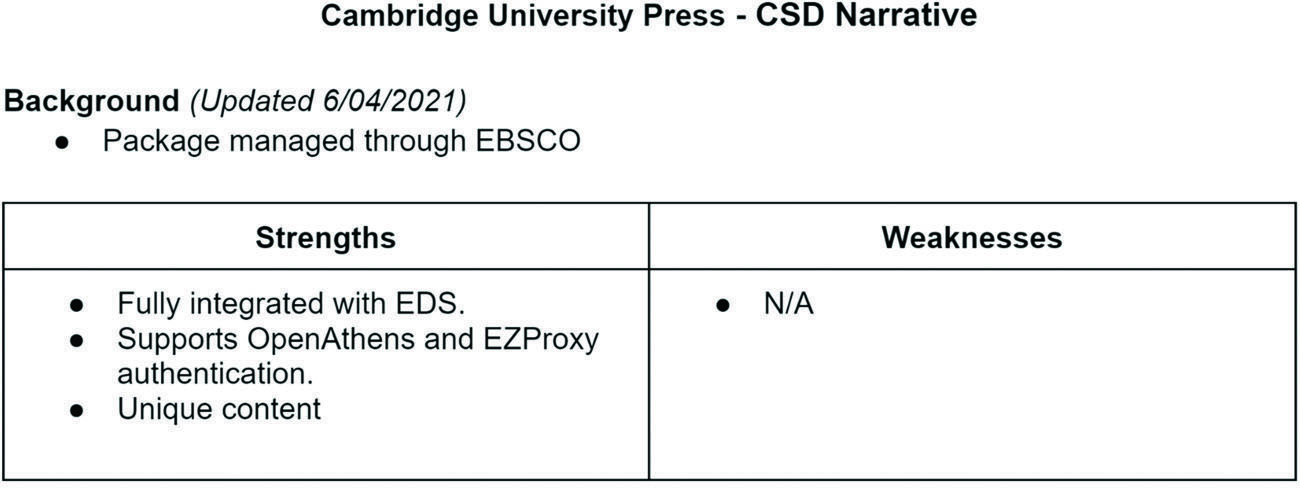

Next, our Collection Services Department (CSD) librarians created CSD narratives, as shown in Figure 3, to be used internally to provide background and insight into each resource’s perceived strengths and weaknesses to our colleagues within the libraries. These narratives tended to focus on how well the resource integrates with other products that we have such as EBSCO Discovery Service, our discovery system, or if the resource can be authenticated via OpenAthens or EZProxy to ensure that off-campus users can access the same content as users who are on-campus. A link to the CSD Narrative was added to the cover page of each resource dossier.

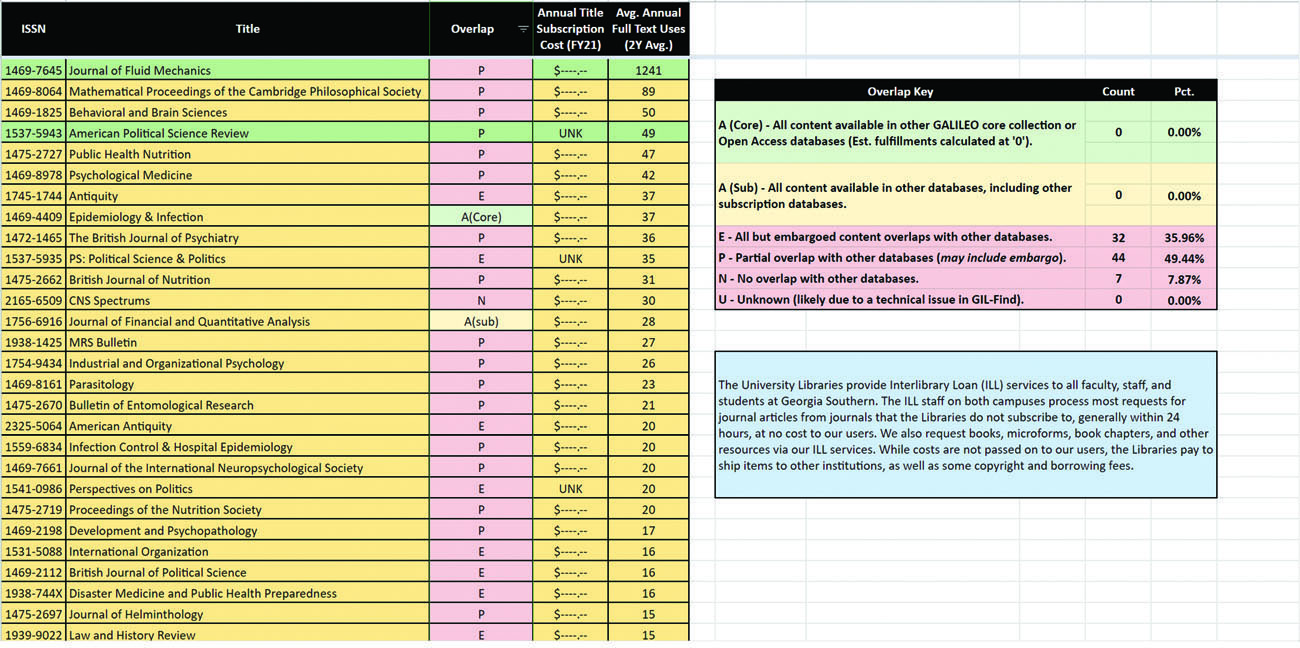

We also created combined analysis documents to summarize the data we collected and added the analyses to each dossier as a final sheet. An example of a collection analysis document is shown in Figure 4. We focused on whether there was partial overlap, complete overlap, or no overlap at all for each title. We also provided the annual title subscription costs to show how much we would pay for the title if we cancel the package and add this subscription as an individual title subscription. The annual title subscription costs were then used to calculate our expected spend and determine whether we would meet our target for the savings we were trying to obtain if we were to unbundle the journal package. We also included the estimated annual fulfillment cost to show how much it would cost the libraries to purchase individual articles from a journal through interlibrary loan if we cancel a subscription for a title or package. We wanted to make it clear to faculty that even if we were to cancel a subscription the libraries would still provide journal content, they would just need to wait longer to receive the content.

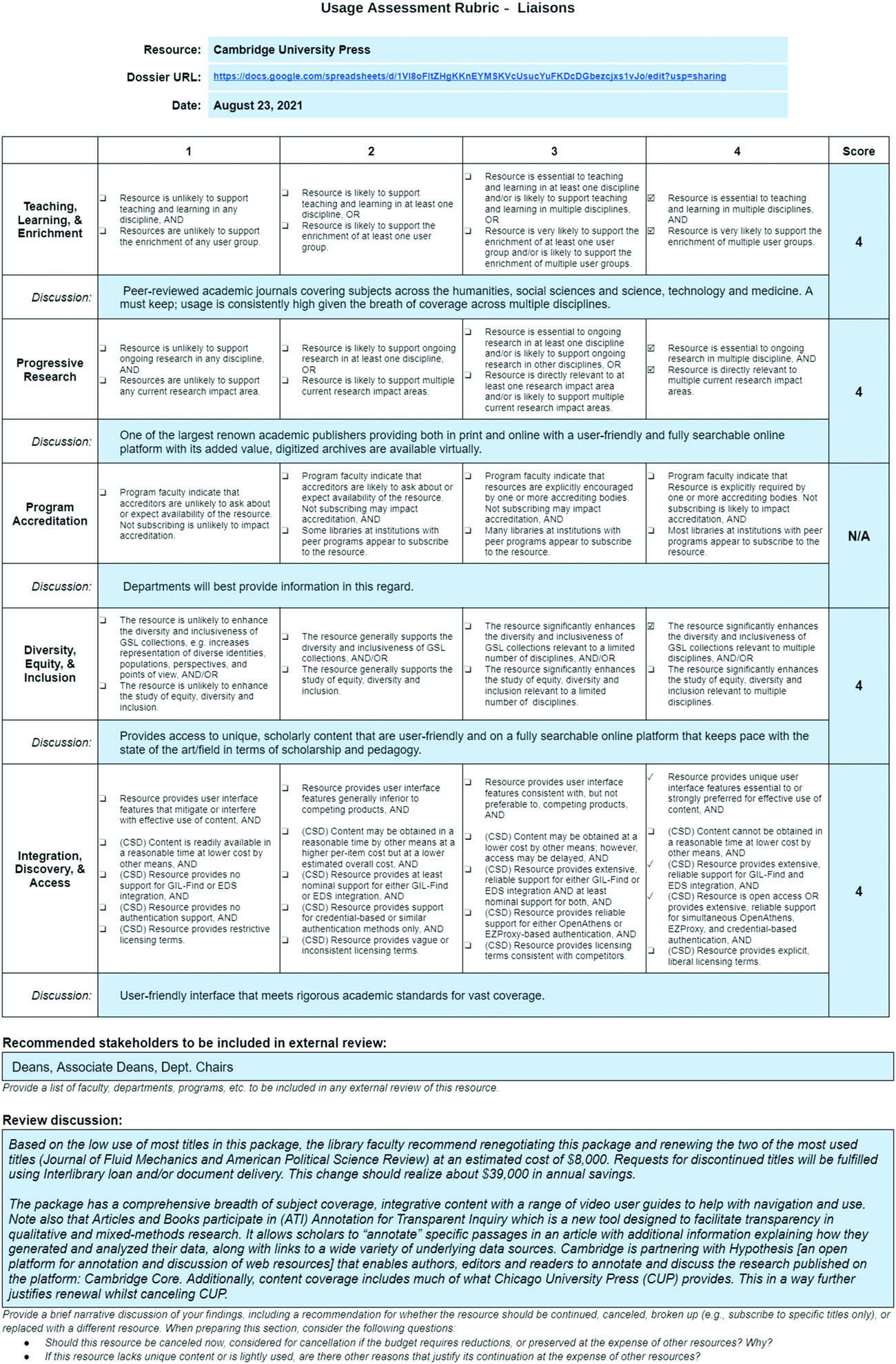

After we provided the information that we assembled about each journal package to the liaison librarians, the liaisons used this data to complete the liaison rubrics, an example of which is shown in Figure 5, using a one-to-four scale to evaluate each package. Criteria included “Teaching, Learning, and Enrichment,” “Progressive Research,” “Program Accreditation,” and “Integration with Discovery and Access.” We gave them the opportunity to discuss these points under each criterion so they could evaluate each resource and share their reasoning behind their rankings. Liaisons were asked to list the recommended stakeholders to involve in an external review, such as deans, associate deans, and department chairs. Finally, liaisons recommendations about whether we should renew or cancel a database or package and subscribe to individual journals that are important to faculty.

The liaison librarians’ final recommendation was to unbundle eleven of our big deal journal packages and to subscribe individually to the titles that the departmental faculty decided they needed. At the end of phase two, we narrowed down our focus and expanded the evaluation process to include departmental faculty.

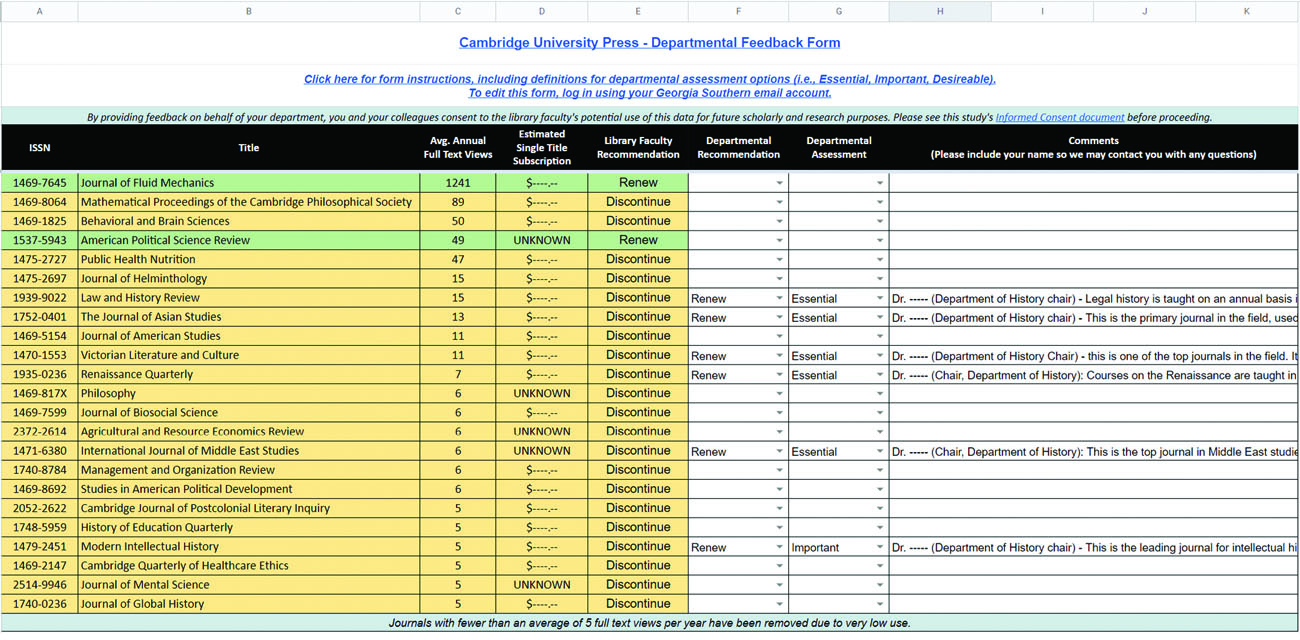

To collect faculty feedback, we created multiple feedback forms so that all academic departments had their own forms with which departmental faculty could communicate their opinions about the individual titles in the packages. The feedback forms provided the basic usage data, the estimated single title subscription cost, and the library faculty’s recommendation to cancel or renew for the journal titles that were a part of the journal collection under consideration. In each form, we included a link to instructions, links to the librarians’ dossiers and rubrics, and, and three feedback fields (see Figure 6).

To complete each form, we asked the faculty to work with their department heads and subject liaisons to review each title, then 1) indicate whether it should be discontinued or renewed; 2) indicate whether it is essential, important, or desirable for teaching and research; and 3) provide any written comments. In our instructions, we provided the following definitions:

Essential: This journal is essential to teaching, learning, and research in the discipline and it is essential that students and faculty have immediate (real-time) access to all the contents of this journal. Any delay in access will cause irreparable harm to the department’s ability to provide instruction and conduct research. Interlibrary Loan (ILL) and/or document delivery are insufficient alternatives for providing access to the contents of this journal.

Important: This journal is important to teaching, learning, and research in the discipline; however, it is not essential that students and faculty have immediate (real-time) access to all the contents of this journal. While a delay in access may cause inconvenience, it would not impair the department’s ability to provide instruction and conduct research. Interlibrary Loan (ILL) and/or document delivery are acceptable alternatives for providing access to the contents of this journal.

Desirable: This journal is desirable for teaching, learning, and research in the discipline. Immediate (real-time) access to this journal is a benefit, but not at the expense of providing access to other essential or important resources. Interlibrary Loan (ILL) and/or document delivery are acceptable alternatives for providing access to the contents of this journal.

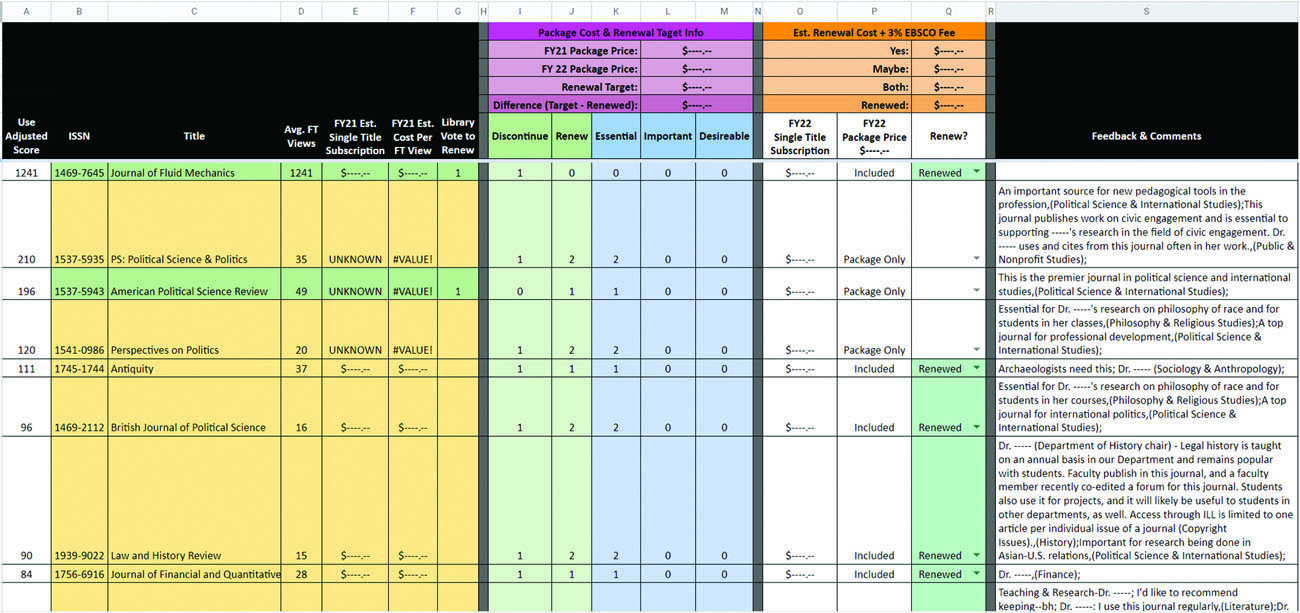

We sent copies of each of the eleven forms to each department outside of the library and gave the departmental faculty five weeks to complete their responses. Of 528 forms sent to forty-eight departments, 148 completed forms were returned. We deemed this response appropriate given that not every package under review was of importance to every department, and departments generally skipped forms related to resources that did not pertain to them. After all the forms were returned, we aggregated the departmental faculty’s feedback into a single title selection worksheet for each package. For each journal, the worksheet showed total departmental votes to renew, total departmental votes for essential status, and all written comments (see Figure 7). We then added to each worksheet information we needed to make final selection decisions, including updated pricing and usage information and estimates of cost per use for any titles we elected to renew.

With quantitative and qualitative data now in hand for each journal, we needed a way to rank titles for renewal. To do this, we developed the equation

where e is the total number of faculty votes for essential status, r is the total number of faculty votes to renew, and v is the average number of article views per year. By adopting this “Use Adjusted Score” to rank all titles from highest to lowest for each package, we principally and equitably balanced faculty feedback with usage data to ensure that we privileged journals with sufficient usage to justify the cost of subscription while safeguarding lower-use titles of unique value to faculty and students.

The task of making the final decisions fell to the Dean of the Libraries. The Dean was provided with all the title selection worksheets, and she used the use-adjusted score for each title and faculty comments to make those decisions. We also developed an expense modeler that showed the total spend across all the collections so the Dean could estimate in real time how the total renewal cost for subscriptions changed based on the titles she decided to renew. She was able to track the estimated savings to make sure she was meeting the target goal of reducing our spend by $300,000.

Once the Dean decided which titles to renew and cancel, we had to communicate these decisions to the University community. We built a public LibGuide that provided all the information to the university faculty, deans, and provost about our process. The front page of the LibGuide included a letter from the Dean, along with a full history and timeline of the project. Other pages of the guide provided a detailed description of the assessment methodology we used, the title-level renewal lists, liaison contact information, and a list of Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) that we developed based on questions we got back from faculty over the course of the process.

Our next step was to communicate our decisions to vendors. We notified vendors as early in the process as possible. During this part of the process, we received updated pricing which occasionally differed from the pricing that we were working with during the analysis stage. These differences were largely due to the added cost for multi-campus access. This new data required us to change our planned title renewals, and we again used the expense modeler as we received new pricing while negotiating our new licenses. As we re-evaluated our earlier decisions, we decided that, instead of canceling or breaking out the University of Chicago Press package, we would continue to subscribe to this package because we were able to get a better price from the vendor that helped us meet our goal. We also decided to keep the Duke University Press and Project Muse packages because the cost of subscribing to the individual titles that faculty determined to be essential was greater than the cost of renewing the whole package. On the other hand, we decided based on usage and faculty feedback that the American Society of Microbiology (ASM) package should be canceled in its entirety. We did not have the faculty feedback to justify keeping any individual journals let alone the whole package.

We updated the journal holdings in Alma, our unified library services platform, as the vendors updated our access. In some cases, our vendors kept our subscriptions activated for titles that we canceled past their end dates, and we retained access to some titles that we canceled into early spring of 2022. We tracked those changes as they happened, and we updated our holdings in real time as quickly as possible so that there would be little impact on students and faculty.

We also made changes to the resource descriptions on the Georgia Southern University Libraries’ A to Z Database page to show how our access to subscribed content changed as a result of the decisions we made during the Assessment project. We especially wanted to show that while we did cancel some journal packages, we tried to retain subscriptions to the individual journal titles most desired by faculty.

At the conclusion of this project, we reached our $300,000 goal. We now have new tools and procedures in place for the next round. We have a better idea of how we can get as much input from various stakeholders at the appropriate times in the evaluation process as possible, and we have a new framework to implement in the future. Perhaps most importantly, we also had mostly positive responses from the departmental faculty. We did receive some concerns at various points when people were afraid they would lose access to titles they really needed, but everyone in the libraries communicated diligently throughout and tried to make the process as transparent as possible. This clear and transparent communication went a long way to minimizing any pain that our community may have felt in response to the cuts, and we count this experience as a success.

Contributor Notes

Jeff M. Mortimore is the Discovery Services Librarian at Georgia Southern University in Statesboro, GA, USA.

Jessica M. Rigg is the Acquisitions Librarian at Georgia Southern University in Statesboro, GA, USA.

- Jaclyn McLean and Ken Ladd, “The Buyback Dilemma: How We Developed a Principle-Based, Data-Driven Approach to Unbundling Big Deals,” The Serials Librarian 81, no. 3–4 (2021): 295, doi:10.1080/0361526X.2021.2008582; Cindy Sjoberg, “E-Journals and the Big Deal: A Review of the Literature,” School of Information Student Research Journal 6, no. 2 (2017): 1–10, doi:10.31979/2575-2499.060203. ⮭

- William H. Walters and Susanne Markgren, “Zero-Based Serials Review: An Objective, Comprehensive Method of Selecting Full-Text Journal Resources in Response to Local Needs,” The Journal of Academic Librarianship 46, no. 5 (September 2020): 2–3, doi:10.1016/j.acalib.2020.102189. ⮭ ⮭

- Ibid. ⮭