Welcome! It’s great to be with you at my first in person conference since 2019. Our vendors are transitioning themselves from publishing or integrated library systems to data analytics, a phrase they are using; I’m going to talk about what this transition means for us. I’m a librarian and a lawyer, but my role as a law professor is what has allowed me to research and write about this. Being outside of a library, I have the luxury of tenure and not being around contracts, but I understand why these conversations can be fraught. When you’re negotiating with vendors, it’s hard to step back and critique them or think about the larger implications of what they are doing. I want to specify that this discussion is about vendors and our relationship to them, but it is not about bashing vendors. We cooperate with vendors. There are a lot of great things that vendors do, and I have always loved the people I’ve worked with in the organizations that I’m going to talk about. I’m going to discuss what data analytics are, I’m going to talk about the big implications of what data analytics and these companies’ changes mean to us, and end with some simple things that we can do along with our vendors to ease some of our concerns in these areas.

Data Analytics Defined

Data analytics is the pursuit of extracting meaning from raw data using specialized computer systems that transform, organize, and model the data to draw conclusions and identify patterns. Raw data include personal data we create as we use digital products, as well as more structured information that these companies have been collecting, archiving, and selling us for years: newspaper articles, blog posts, court cases, academic articles. These informational assets are being run through machine learning and algorithmic systems to create data analytics products.

Here are some examples of data analytics products; if we work in a library, these are all things that our products already include or that the companies that we work with are trying to sell us. Big analytics companies like RELX or Clarivate sell other businesses “business solutions,” advice about what to do based on data analytics. Analytics companies also assess all of us. Are we risky? Are we likely to commit a crime, commit fraud, or have health concerns that might make us riskier to insure? The companies we work with sell these predictions as “risk assessment” products. “Competitive intelligence” is compiling, sorting, and visualizing data about the competitors and consumers in any given market. Competitive insights about clients are really useful in law firms and a lot of law firms even have their own competitive intelligence analysts. “Metrics” involve putting stuff in a list and saying which is worst, which is best, which is in the middle. We can rank institutions, labs, people, what have you. Any data analytics product ending in the word “insights” is just taking the data sets a company has, running them through data analytics, and making more insightful information based on whatever those systems spit out. Finally, analytics that predict what will happen are the creepiest and most fraught. Sometimes they’re useful, predicting the next COVID-19 outbreak, where there will be a drought, or how hurricane season will look, but some are predictions about people, who might commit a crime or commit fraud. There are all sorts of analytics we deal with every day where machine learning or algorithms are used to predict what people might do.

I want to stop here and say that I am not anti-data analytics, and I don’t know if any of us should be. Part of progress is accepting new technology, and data analytics are part and parcel of that new technology. Data analytics are doing a lot to benefit society when it comes to tracking things like illness, weather, or global conflict. But data analytics can be very bad if used incorrectly in a way that perpetuates violence, bias, or inequality, and they are very different than what we are used to our vendors doing.

From Publishing to Data Analytics

Traditionally, our vendors did things like print and sell final edited materials. When we bought a set of encyclopedias or an ongoing update of a serial, there was one point of sale when we got the material. There was no secondary data market; once the publisher handed over a book, they did not track who used it afterwards. Finally, for traditional vendors, libraries and readers were the main customers. We were the main consumers for Westlaw and the people that Elsevier worked with and wanted to satisfy.

Data analytics is a whole different business. Data analytics companies still sell books and serials online, but in this new world they also sell analytics based on raw data they get from platforms and from crunching their data assets. There are no complete purchasing transactions; we only license material that stays on the vendor’s cloud in their servers. While we are on their platforms, they are watching us the whole time to make sure we’re not violating their copyright; there is no truly private searching. And these companies have a lot of new customers and libraries and readers are just one among them.

Companies like RELX are proudly and openly switching to data analytics from publishing. They say their heritage is in publishing and they have managed down their print publishing to just 10 percent of their sales. They employ thousands of technologists and invest billions of dollars in growing data analytics. They have recategorized on the Morgan Stanley Index as a “business services” company (a phrase that means data analytics), and they now describe themselves as “a global provider of information-based analytics and decision tools for professional and business companies.”1 So they are changing, and they are not the only ones! Clarivate “provides data insights and analytics for the innovation lifecycle”2 and Bloomberg sells themselves as “facing the data, changing the world.”3 These vendors are selling us data analytics products within our old packages. You used to log into Westlaw and there would be statutes, case law, or regulations; now you can find litigation analytics to help you improve your strategy. When you look at an Elsevier article, they overlay metrics over the primary content you are looking for. We are either directly or indirectly paying for embedded analytics products, whether we want to or not. There is no way to untangle them and tell Westlaw we just want the databases or tell Elsevier we want ScienceDirect without the metrics.

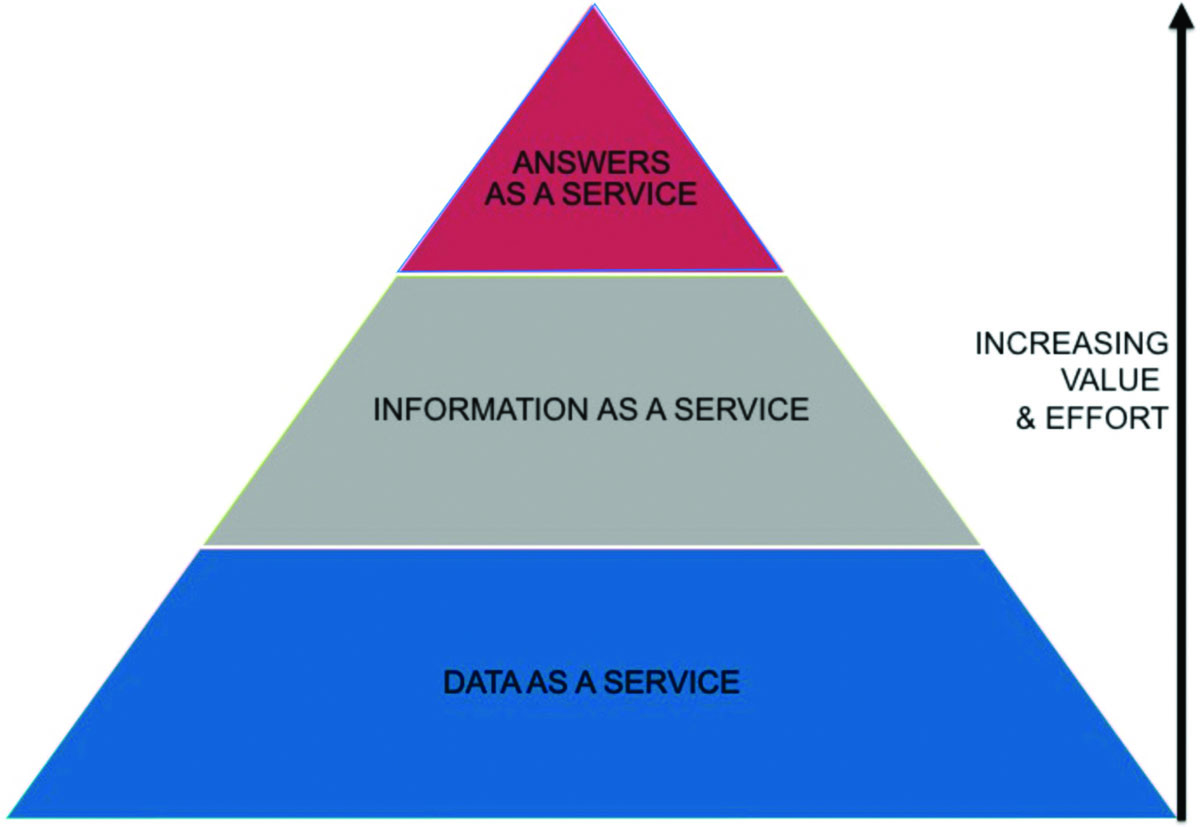

Clarivate’s 10-K report explains how getting into data analytics allows them to sell layers of data and information products and profit at each point. You can buy just their raw data dossiers; data they have cleaned up, standardized, and organized; or their entire platform of databases; but the real value-add is in their predictive analytics that tell users what will happen and their prescriptive analytics that tell users what to do.4

Here is a simplified version of Clarivate’s chart (see Figure 1). They are increasing the value, revenue, and customer base on informational assets they already have, finding new ways to slice and dice them and sell not just the information but also predictions and prescriptions: answers as a service. That is the part we need to pay attention to as information professionals.

Why are our vendors becoming data analytics companies? Because all companies are becoming data analytics companies. Our vendors are following the trend of information capitalism, moving away from physical goods towards selling all the great data they are getting from digital goods. In other industries, thermometers can now track illness. Refrigerators tell us when we are running out of milk (but also collect information about how often we buy milk). Cars sell data about how we drive to insurance companies. I’m wearing a watch that is telling a company what my heart rate is, how many steps I took, where I took those steps, and what the weather was like. Our vendors are doing the same thing, and why wouldn’t they? They are for-profit companies, and this is a creative way to make more money.

When you do a Google Image Search for “data analytics” you get miraculous images, but in reality, data analytics is more like the Play-Doh “Fun Factory” toy I spent a lot of time with as a kid. You took different pieces of clay and squished them through an extruder to make products like spaghetti hair. In essence, that is what data companies are doing. They have millions of academic articles, all the case law and Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) filings in the history of the United States. They are taking this information, like chunks of useful clay, and extruding them through data analytics products to make new data products to sell. The problem is we do not know how they are doing that. We cannot see inside their trade secret protected algorithms. When RELX describes its own data analytics products, they describe them as systems that move so quickly and do so many different functions that even Elsevier does not know how they work.

We may not be sure how algorithms work, but we do know that algorithmic bias and error are common occurrences and algorithms might not be things we want to depend on.5 The other problem is biased data sets in which the amount of data in the system affects which results will be pushed to the top, for example, academic article citation metrics dominated by prestigious institutions, or criminal data sets where Black men have bigger criminal files than white women due to structural racism. We cannot be sure that data analytics systems are reliable and free from algorithmic and data bias. Nobody knows, not even RELX itself.

Implications for Libraries

So what does this have to do with libraries? It has led to vendor consolidation. All industries move toward consolidation as they mature, but library vendor consolidation is interesting because information is non-fungible. You cannot exchange one item for another; if you ask me for an article about COVID-19 and I give you an article about malaria, that does not work. These companies are trying to collect as many data assets as possible because every piece is unique, the company that has more has the most robust platform, and the company with the most robust platform wins. In law librarianship, many of us continue to use Lexis in large part because we need access to material we can’t get anywhere else. We are also no longer vendors’ first and only customers. Our libraries’ and our patrons’ data are seen differently as useful resources. We are getting all sorts of predictive and prescriptive bells and whistles added into our products and contracts without our consent, and we are paying for them. And we are, more and more, only able to access the material we need on walled garden platforms, where every person has to log in so they can be uniquely tracked around the platforms.

I wanted to touch on vendor consolidation. If you ever want to be shocked by the amount of consolidation among our vendors, visit Marshall Breeding’s Web page. He tracks vendor consolidation and shows how fifteen companies have been consolidated into Clarivate.6 A great study by Alejandro Posada and George Chen shows how Elsevier makes money not just on published articles at the point of sale, but also by tracking clicks on preprint platforms and selling analytics in the research evaluation process. Products for the pre-publication, publishing, and research evaluation processes all used to be independent companies, but are now all consolidated under Elsevier, allowing the company to monetize more of the research process.7

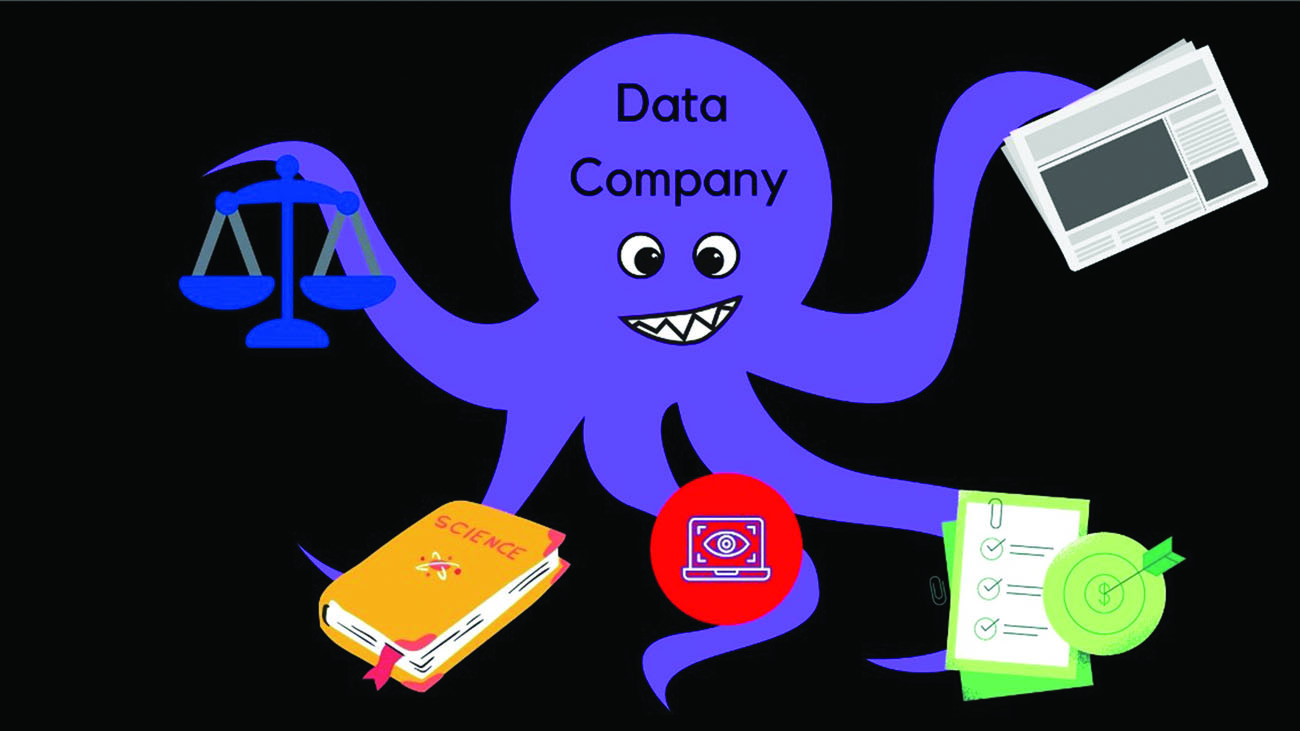

My book about data analytics is called Data Cartels because really what we are dealing with are burgeoning, ever-growing monopolies like Standard Oil, the monopoly that spurred our whole anti-trust law system. Standard Oil was compared to an octopus because the company was so powerful that it reached into all industries. It was even able to capture government offices because the government depended on oil. Everybody needed oil. If we have moved from the industrial era to the information era, that means information companies have the same power. I do not have the artistic skills of the Standard Oil cartoon artist, so this is my version (Figure 2). Data companies can reach like octopuses across a lot of segments. We all know about the academic journal oligopoly. RELX claims to have the biggest news archive in the world. Legal information is a duopoly in the United States between RELX and Clarivate. These are also huge data brokers with some of the biggest dossiers of personal data in the world, which is what drew my attention to this topic in the first place.

Problems with Data Analytics Companies

New business, as I said, equals new customers. Libraries are just one of many customers for data companies. In law librarianship we have been talking about this a lot. They do not need us as much, they do not care about us as much, and we can feel that in our negotiations with them. They sell huge data dossier and predictive policing products to law enforcement. LexisNexis and Clarivate are major data sellers to Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and helped to fuel ICE’s predictive policing and immigration tracking systems involving child separation.8 It’s not just law enforcement; LexisNexis says that it sells personal data products to 70 percent of local government and almost 80 percent of Federal agencies.9 LexisNexis data gets sold to tenant screening companies, which, because the data are imperfect, leads sometimes to bad outcomes. People are unable to get housing.10 They also sell data products to healthcare systems and tag people who might be at more risk of opioid addiction or other illnesses. That might bring unwanted attention to them or make certain kinds of healthcare treatments hard to access.11 LexisNexis sells a ton of data products to insurance companies and banking institutions, leading to the kind of data problems and imperfections that we see every day as librarians.12

Many of these new customers are being sold risk solutions products. LexisNexis describes this business in detail on its website.13 We all have data dossiers in LexisNexis with a universal identifier called a LexID used to link, identify and rank people, and alert customers when something changes. They have 283 million LexIDs containing 78 billion records and they get data from over 10,000 sources, which is one of the reasons that the data tend to be wrong so much of the time; they cannot vet the fire hose of personal data always coming into their systems. Thousands of law enforcement agencies use LexisNexis as a common pool to share data among themselves; this is a lot like the fusion centers created after 9/11 that civil rights organizations said were problematic, but LexisNexis is doing this as part of its business without any oversight or government regulation. LexisNexis data are used across all of their products, and they have not been able to promise that our library products are not part of the system. I don’t want to pick on one company; Clarivate also describes how it is broadening its systems into data analytics. It describes its acquisition of ProQuest as an opportunity to use ProQuest’s data cloud, with its billions of harmonized data points, in its Clarivate Research Intelligence platform.14

In addition to risk assessment products, data analytics vendors also sell “evidence-based planning and foresight.”15 They identify emerging research areas and technologies and uncover hidden opportunities in your institution’s research portfolio, but they also knock out what they perceive as unprofitable research – which is often public-interest oriented research. The new ProQuest and Clarivate are rethinking their products to be data vectors that they can sell to not just our own institutions, but also tech and pharma companies, to shape our knowledge system by telling people what to invest in, what labs to set up, and what labs to defund. We are giving these private companies a lot of power to make decisions that impact knowledge and research right at our own institutions. This is something to be vigilant about.

Conclusions and Recommended Solutions

Here are the problems with data analytics companies that I hope this talk has helped you understand. First there are privacy problems. Risk and metrics products are based on data clouds full of personal data. Our personal data is becoming more infused in research systems whether we consent to it or not, and because they are monopolies, we have little choice about what vendors we can use. Second, there are access problems as we face consolidation into walled garden platforms and the datafication of information. News, academic research, and financial information is becoming less and less accessible and prices are less negotiable. Finally, there are data and information quality issues. Information and data are like the soil data analytics products are grown in, so the more you have, the better. Vendors used to be concerned about giving us the best quality information; legal databases would never have thrown trial court filings and random legal blogs into information lawyers were supposed to rely on. Now on Westlaw there are trial court filings with no precedential value, which often are not even well drafted, blended into the products that I teach my new students how to use. They are getting a firehose of new data about us all the time and the companies fully admit that they’re not vetting the data. Quality control is becoming more of an issue.

Luckily, there are some solutions we can do cooperatively and work on as a team. They don’t hurt libraries; they don’t hurt vendors. For privacy problems, I would love to see all vendors promise to protect and expunge library data. Vendors should apply the same privacy norms that we apply in our libraries and make sure there is a wall between research platforms and the data brokering products sold to law enforcement, healthcare companies, or insurance companies. Let’s ask the companies to promise us that those two businesses will be separate. To address access problems, we need open and affordable information options. There is a whole Open Access movement and so much work being done, but it takes a lot of people, labor, and maintenance. We need to convince information companies or governments to better fund that work. And for quality problems, we could ask companies to use some of their profits for quality control. Research shows that Elsevier is a billion-dollar company with higher profit margins than Facebook and Google. They could hire people or set up systems that vet data and information resources, rather than simply routing all that revenue to growing more algorithms or machine learning products.

Thanks for listening. It was fun to talk in person! I think it’s time for questions.

Questions and Answers

The first question was whether there is any legal recourse for data brokering, given that it is commonly accepted that “if the service is free, you’re the product,” but these are paid services scooping up and reselling our data to other companies. I have been really surprised that since I started paying attention to these issues in 2017, there has been zero legislation to deal with data brokering. There has been a little action around preventing data brokering in predictive policing, but the selling of people’s data is a vastly unregulated industry. I’m not saying we want to put extra work on librarians–most of us are overworked already, doing the jobs of other people who our institutions let go due to attrition–but people who focus on these issues could think about what legislation would look like that protects us from this kind of exploitation. The 1970’s were a time when there was a lot of surveillance–libraries were being surveilled by the FBI–and the American Library Association pushed for state laws that required library privacy for stacks and paper circulation records. It is time to think about what library privacy looks like in a digital era and update the legal infrastructure, whether at the state or Federal level.

The question about incentives for companies to improve data quality has no easy answer because automating vetting services that were once human is so much more affordable and efficient. But there definitely are quality problems when you automate. My mentor, Susan Nevelow Mart, has done empirical research on the inaccuracies of automated legal research systems, how often a case is marked as “good law” when it is actually bad law, and vice versa.16 We need to make it clear to vendors that this problem needs to be corrected or accounted for because it is fundamentally important to quality research and to scientific and humanistic progress. We are in this world where misinformation is more prevalent than ever, with information bubbles and misinformation spreaders who blatantly share information that is not high quality. We work so hard to ensure that academic research is peer reviewed and verifiable, and then to see it trashed in these algorithmic systems that strip away the veracity is frustrating. Financially, it does not make any sense to put people back in the equation, but we know that in a lot of cases we need humans to make sure the algorithms are getting it right.

This is a great comment that library budget cuts contribute to the monetization of data because libraries have, in some cases, no other choice but to look at a less expensive or freely available product where we then become the data. Having library organizations lobby for increased external support is important. Internally, we know libraries are important and know all the roles that libraries serve, but outside of the library, people are not thinking about the library as much as they should be, which means we are not getting as much external support. We need to make sure others know that if we do not support libraries, all our Internet and social media problems with misinformation are going to get worse. Libraries are an important player in the information ecosystem and when we underfund them, society loses out. Libraries are this free hub where you have intellectual freedom to research whatever you want with professionals by your side and the promise of not being tracked. You don’t get that for free online!

It describes the problem perfectly to ask whether buyers of data analytics products will at some point realize they are low quality and stop buying them, or whether buyers won’t care because analytics serve as a “seal of approval” so buyers can do what they wanted to do in the first place! What makes me sad is I think it’s the latter. In my book I cite situations where data analytics have been proven wrong, but nobody cares because they are so easy. In Colorado, a law enforcement agency was using a LexisNexis product called Lumen. If I thought you might commit a crime, I could take a picture of you and it would automatically line you up with an entire catalog of police booking photos. But there’s all these veracity problems with predictive policing systems–a lot of the people who were booked are later found innocent, your face might not match correctly—so they took Lumen away. The law enforcement officers are quoted as saying they are just waiting until they get Lumen back.17 I think it’s like Palantir. It has been proven that Palantir’s predictive policing systems do not identify people who are going to commit a future crime, but they are still a multi-million-dollar company with tons of government contracts.

The last question asks for advice for librarians who are finding that they have less leverage to negotiate for privacy clauses in database contracts due to vendors’ willingness to let libraries walk away from negotiations and instead sell to other customers. I have been working this year with SPARC, an amazing organization that focuses on Open Access, to create a community of discussion around that exact issue. We are going to have to try things and see what works and talk to each other. In the CUNY system, we have been looking at specific contract language such as Becky Yoose’s list of recommended contract language and suggestions.18 We are tailoring them to our institutions to see what, if anything, will work, but it is going to be another layer of negotiations that we have to do as librarians. Not just negotiating their content, but also negotiating what content they get from us when we use their products. I guess that’s it. It’s so nice to be here in person, and I hope you enjoy the conference!

Contributor Notes

Sarah Lamdan is Professor of Law at City University of New York School of Law, Flushing, New York.

Sanjeet Mann is Arts and Systems Librarian, University of Redlands, Redlands, California.

- “Our Business Overview,” RELX Group, accessed July 14, 2022, https://www.relx.com/our-business/our-business-overview/. ⮭

- “About Us,” Clarivate PLC, accessed July 14, 2022, https://clarivate.com/about-us/. ⮭

- “About,” Bloomberg LP, accessed July 14, 2022, https://www.bloomberg.com/company/. ⮭

- “SEC Filings, Form 10-K 2021,” Clarivate PLC, accessed July 14, 2022, https://ir.clarivate.com/financials/sec-filings/default.aspx. ⮭

- Safiya Umoja Noble, Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Enforce Racism (New York, New York: University Press, 2018); Ruha Benjamin, Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2019); Virginia Eubanks, Automating Inequality: How High-Tech Tools Profile, Police, and Punish the Poor (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2017); Cathy O’Neil, Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy (New York: Crown, 2016). ⮭

- Marshall Breeding, “Clarivate: Mergers and Acquisitions,” Library Technology Guides, accessed July 14, 2022, https://librarytechnology.org/mergers/clarivate/. ⮭

- Alejandro Posada and George Chen, “Preliminary Findings: Rent Seeking by Elsevier,” The Knowledge G.A.P.: Geopolitics of Academic Production, September 20, 2017, accessed July 14, 2022, http://knowledgegap.org/index.php/sub-projects/rent-seeking-and-financialization-of-the-academic-publishing-industry/preliminary-findings/. ⮭

- Sam Biddle and Spencer Woodman, “These are the Technology Firms Lining Up to Build Trump’s ‘Extreme Vetting’ Program,” The Intercept, (August 7, 2017), accessed July 14, 2022, https://theintercept.com/2017/08/07/these-are-the-technology-firms-lining-up-to-build-trumps-extreme-vetting-program/. ⮭

- “Industries We Serve,” LexisNexis Special Services Inc, accessed July 14, 2022, https://www.lexisnexisspecialservices.com/who-we-are/industries/. ⮭

- Megan Kimble, “The Blacklist,” Texas Observer, (December 9, 2020), accessed July 14, 2022, https://www.texasobserver.org/evictions-texas-housing/. ⮭

- Richard K. Grape, “No One Party or Workflow Can Address the Opioid Crisis,” Health IT Outcomes, (November 12, 2018), accessed July 14, 2022, https://www.healthitoutcomes.com/doc/no-one-party-or-workflow-can-address-the-opioid-crisis-0001.; Maia Szalavitz, “The Pain Was Unbearable. So Why did Doctors Turn Her Away?” Wired, (August 11, 2021), accessed July 14, 2022, https://www.wired.com/story/opioid-drug-addiction-algorithm-chronic-pain/. ⮭

- Alice Holbrook, “When LexisNexis Makes a Mistake, You Pay for It.” Newsweek, (September 26, 2019), accessed July 14, 2022, https://www.newsweek.com/2019/10/04/lexisnexis-mistake-data-insurance-costs-1460831.html. ⮭

- “LexID,” LexisNexis Risk Solutions, accessed July 14, 2022, https://risk.lexisnexis.com/global/en/our-technology/lexid. ⮭

- “Clarivate to Acquire ProQuest,” Clarivate PLC, (May 17, 2021), accessed July 14, 2022, https://about.proquest.com/en/news/2021/clarivate-to-acquire-proquest/. ⮭

- “Research Analytics, Evaluation, and Management Solutions,” Clarivate PLC,, accessed July 14, 2022, https://clarivate.com/products/scientific-and-academic-research/research-analytics-evaluation-and-management-solutions/. ⮭

- Susan Nevelow Mart, “The Algorithm as a Human Artifact: Implications for Legal [Re]Search,” Law Library Journal 109, no. 3 (2017): 387–422, accessed July 14, 2022, http://scholar.law.colorado.edu/articles/755. ⮭

- Elise Schmelzer, “How Colorado Law Enforcement Quietly Expanded its Use of Facial Recognition,” Denver Post, (September 27, 2020), accessed July 14, 2022, https://www.denverpost.com/2020/09/27/facial-recognition-colorado-police/. ⮭

- “Vendor Contract and Policy Rubric,” LDH Consulting Services as a component of the Licensing Privacy project led by Lisa Janicke Hinchliffe, accessed July 14, 2022, https://publish.illinois.edu/licensingprivacy/files/2021/11/Licensing-Privacy-Vendor-Contract-and-Policy-Rubric.pdf. ⮭