Electronic Data Interchange

Electronic Data Interchange (EDI) is a standard that falls in the Acquire portion of the e-resource lifecycle. EDI is used in many sectors including finance, healthcare, and government. In the library and information community EDI is used by acquisitions and serials librarians, library staff, subscription agents, book vendors, and library system providers. EDI is a technical process that uses electronic files to share information from one system to another. The encoding and structured format allow systems to interpret and process the information in the file. Julia Reijnen explains that “with EDI standards, the structure and exact order of the data is defined, ensuring uniformity and consistency.” The use of standard formats makes it possible for a “system to understand the incoming data without human intervention.” EDI is often used to manage business transactions, such as ordering, billing, and claiming.1 Without EDI, an organization would manually add the data about a transaction from a document into their system. The significance of EDI “is that it standardizes the information communicated in business documents.”2 Manually entering data is time consuming and “highly prone to error” whereas EDI “improves an organization’s data quality.”3 EDI provides automation and efficiencies and thus enhances library workflows.

Electronic Data Interchange for Administration, Commerce and Transport (EDIFACT) is an EDI standard created by a United Nations committee in 1987. EDIFACT is the format in use by the library and the publishing community. The use of EDI in the library world began in the 1990s with the adoption of EDI by the book industry.4,5 Subscription agents and Integrated Library System (ILS) providers followed in the mid-1990s to early 2000s.6,7,8 EDItEUR is “the international group coordinating development of the standards infrastructure for electronic commerce in the book, e-book, and serials sectors.” The EDIFACT format standard documentation can be found at the EDItEUR website.

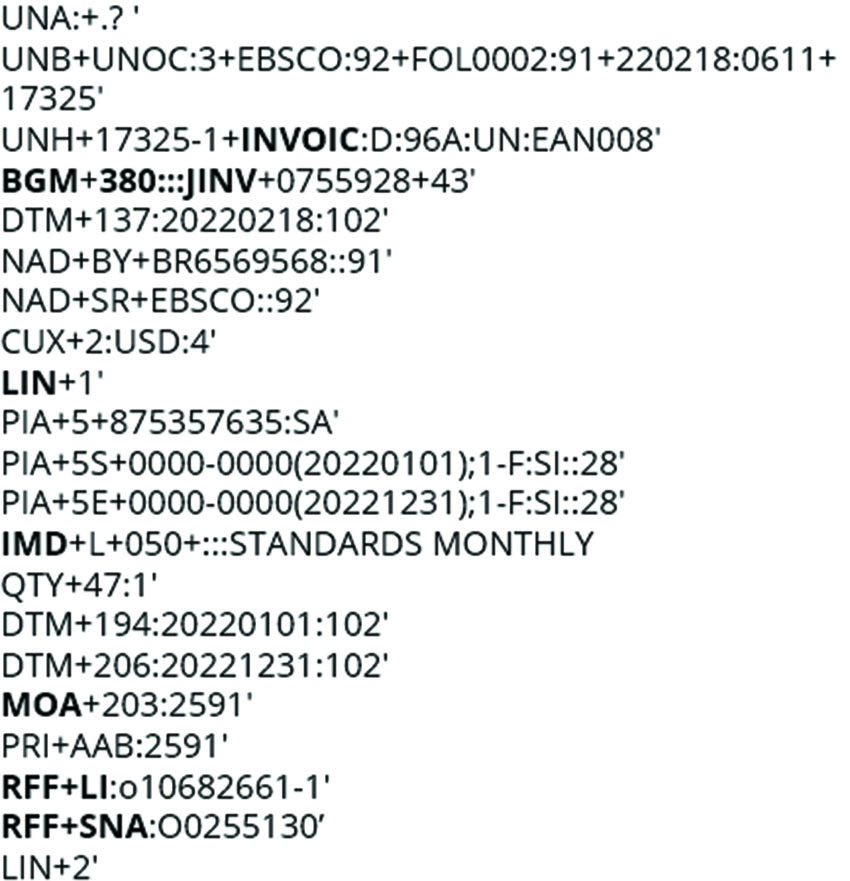

There are different kinds of EDIFACT files, called messages, identified by a code such as ORDERS or INVOIC. Within a message are segments usually marked by three-character codes that describe the data that follows. The codes and data must be arranged according to syntax rules. A portion of an INVOIC EDIFACT file is shown in Figure 1. BGM stands for beginning of message and 380 is the document code for commercial invoice. The code JINV is the document name code for journal invoice and 0755928 is the actual invoice number.

An INVOIC file can have data about more than one invoice in it. The information will be separated by another BGM line for the next invoice. LIN begins the first line item of an invoice. The details of the second line item will follow LIN 2. The item description, IMD, for this line item is the title Standards Monthly. The monetary amount, MOA, is $2,591. The code RFF LI is for the buyer’s reference code which in this case is the library’s ILS order number and is a common match point between the vendor’s system and the library’s system. The RFF SNA code is the agent’s reference number and also a common match point. Determining a match point that links the data between systems is critical for EDI to work.

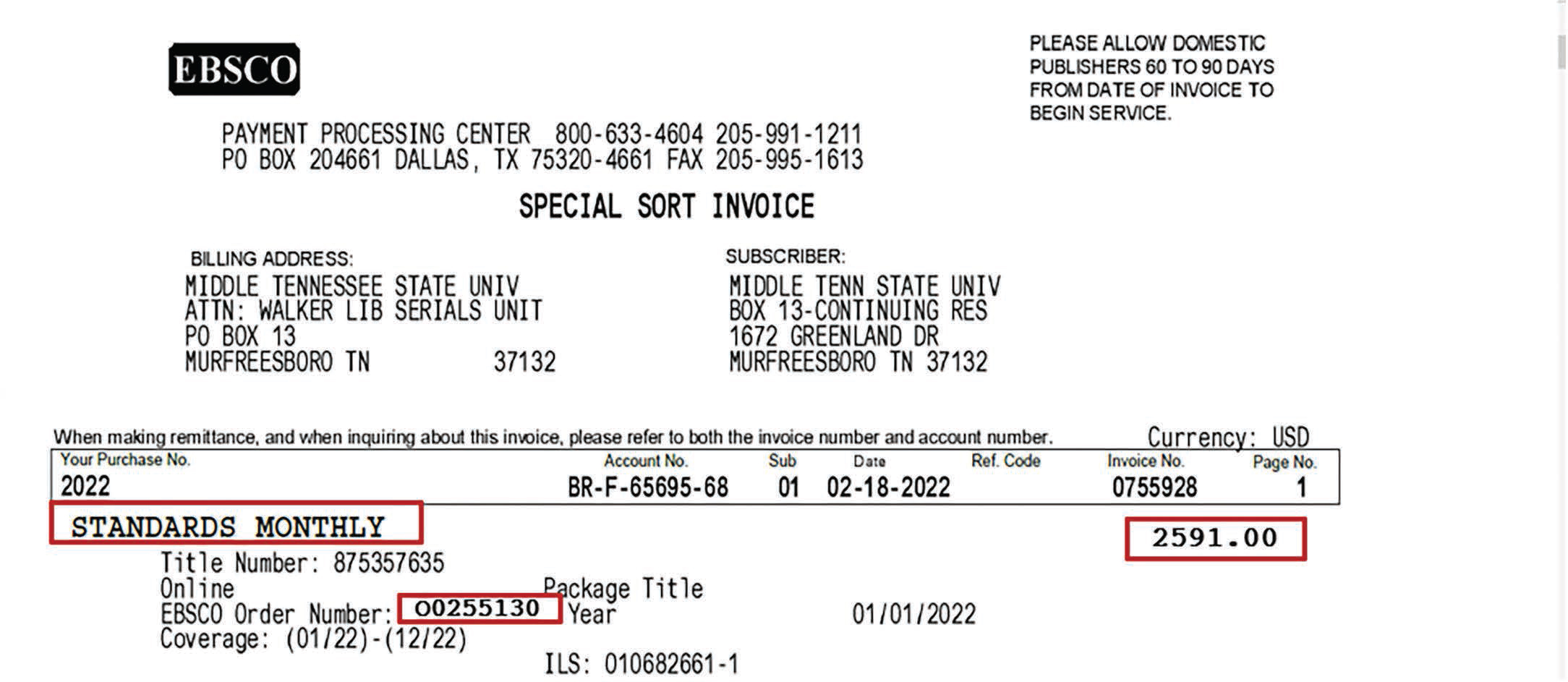

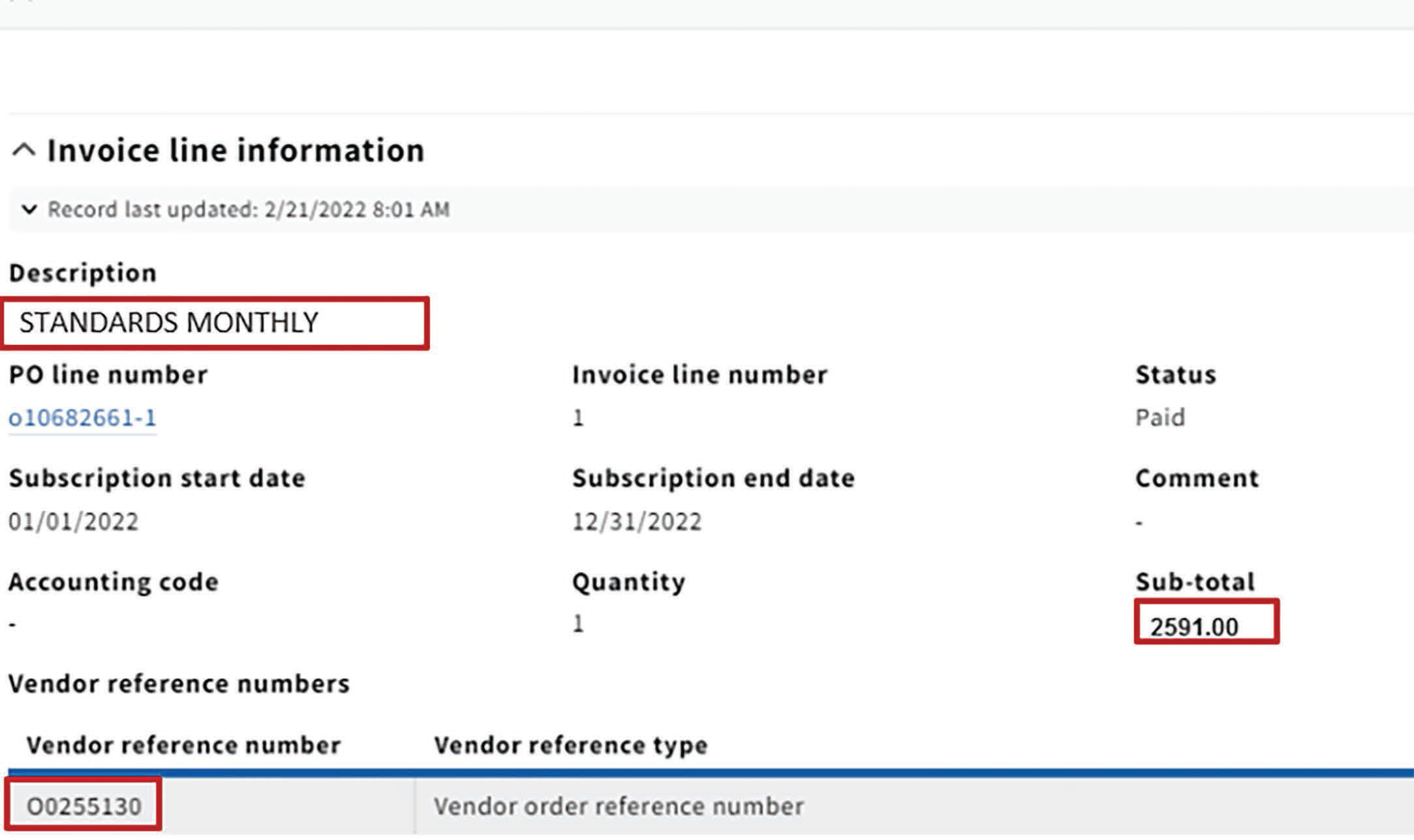

A mock-up of an EBSCO invoice for the title Standards Monthly is shown in Figure 2. Variable data from the invoice such as title, line item cost, and vendor reference number would need to be transferred into the library system. Figure 1 shows the invoice data coded as an EDIFACT message. Figure 3 shows a record in the library’s system with the variable data populated in the proper fields.

Configuring a library system for EDI requires mapping how incoming messages are processed. The segment codes are matched with the library’s system fields so that the variable data in the file are transferred to the appropriate field in the library’s system. Once fields are mapped and other configurations are set the processing of a file is a straightforward task. An email alert is set to the customer with file information such as invoice numbers, number of line items, total amounts and has instructions on how to access the file. The file is retrieved and uploaded (this will vary by system). The end result is that an invoice does not need to be keyed in manually, which is significant when processing invoices with hundreds of lines. Such efficiencies are made possible due to the adoption of a common standard.

KBART

The Knowledge Bases and Related Tools (KBART) recommended practices are integral to e-resource management in the following areas of the lifecycle: provide access, administer, and provide support. The creation, dissemination, and timely updating of KBART files by a content provider, followed by ingestion into a knowledgebase and configuration of the knowledgebase by a library are critical steps to providing authorized access and discovery of e-resources.

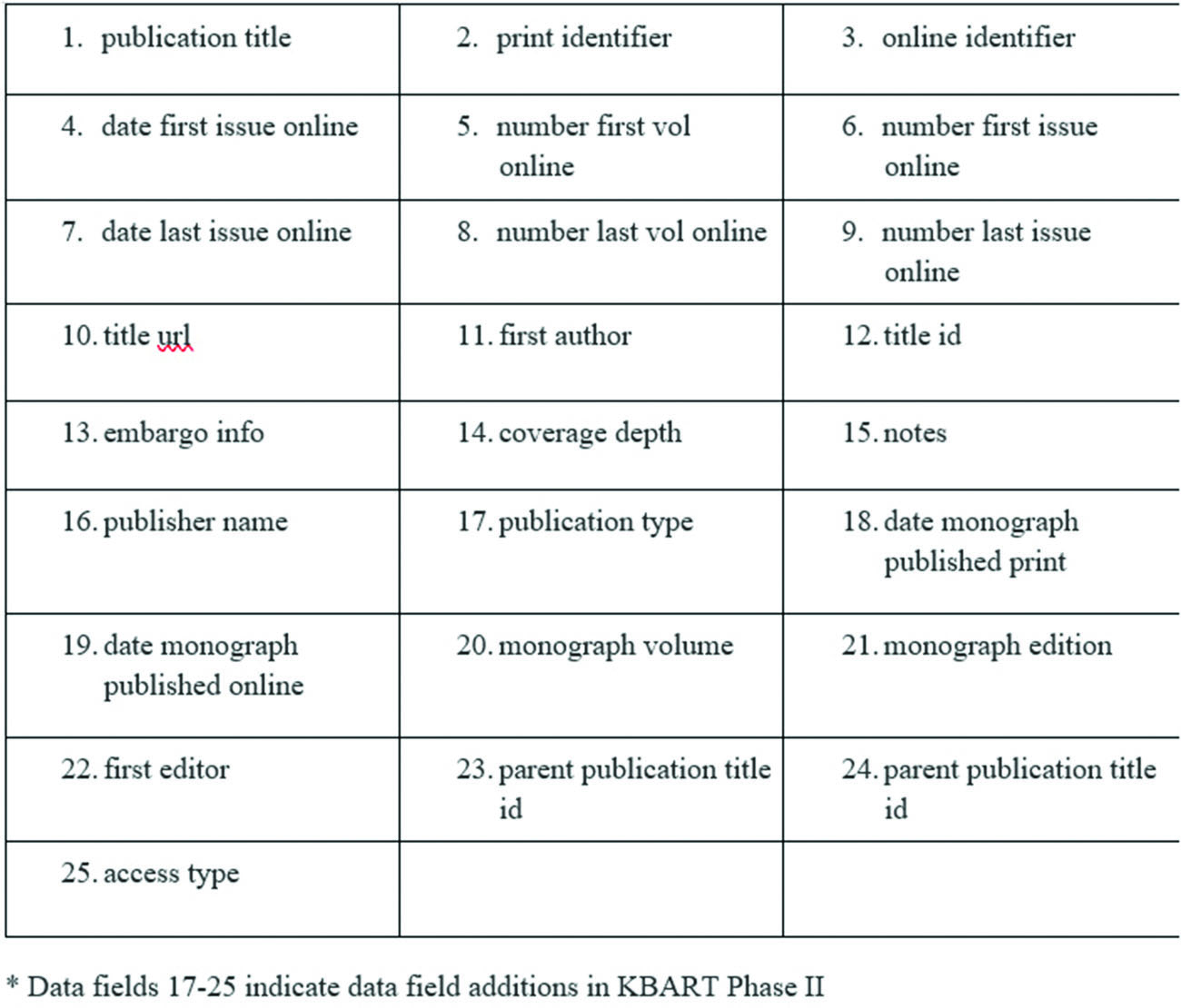

KBART was a UKSG (formerly United Kingdom Serials Group) recommended practice that began in 2007 and is now a NISO recommended practice that ensures the timely transfer of accurate data to knowledgebase and link resolver providers. KBART files are created by content providers using the guidelines in the KBART recommended practice and have evolved overtime to meet the needs of libraries. For instance, the original KBART recommendation only included fields relevant for journals. KBART Phase II Recommended Practice, the 2014 version, includes data fields for books, consortia, and Open Access. Please see Figure 4 for a complete listing of the 25 data fields for KBART Phase II Recommended Practice.

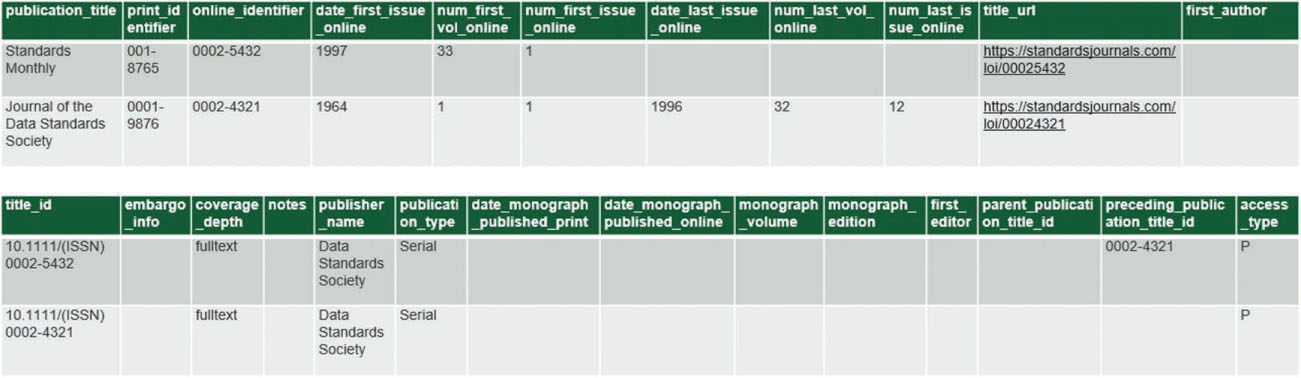

KBART files are subject to updates for various reasons. Sometimes the content provider needs to update the files to correct data, provide updated links, include new publications, and account for withdrawn or transferred titles. Therefore, most KBART files are treated as dynamic, rather than static files, and should be monitored consistently by all stakeholders. Building on the example title from the EDI discussion above, Figure 5 is a sample of a KBART file, containing the title Standards Monthly.

KBART is intended to provide high-level descriptive metadata that points to where content is hosted. In the case of Standards Monthly, there are unique identifier fields representing the title’s International Standard Serial Numbers (ISSNs) for print and online formats, and Digital Object Identifier (DOI) respectively. The available date range and enumeration information for this title is also included. The Uniform Resource Locator (URL) for the title is critical information for link resolvers to be able to channel users to the online content.

KBART files include data regarding previous titles. On the third row, we can see that Standards Monthly was previously called the Journal of the Data Standards Society. The fourth through ninth columns in the KBART file indicate that the title changed its name in 1996 after the 12th issue of volume 32, becoming Standards Monthly in 1997. The KBART access_type field indicates whether a title is free (F) or requires a payment (P).

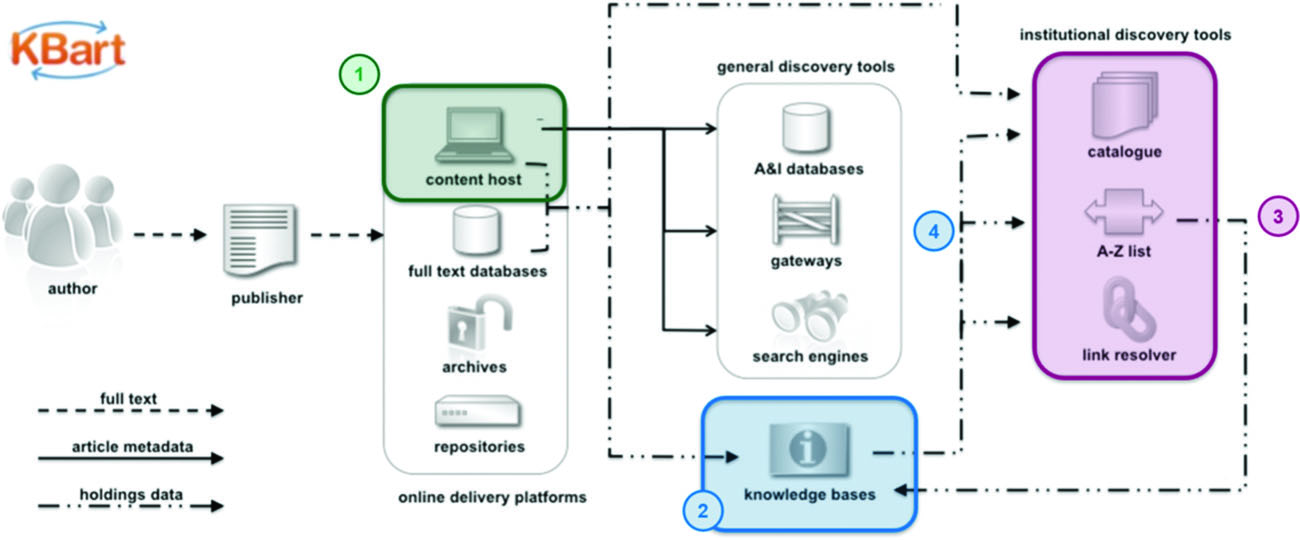

Figure 6 demonstrates the dataflow of KBART files. Moving from left to right on this diagram, the KBART dataflow starts with the content host or content provider who are responsible for creating, updating, and disseminating the KBART files. The updated files then get routed to the knowledgebase vendor. Then the library makes configurations and title selections in the knowledgebase which enables discovery tools to provide access to library patrons. Any mistakes in the KBART file can negatively impact those downstream, such as librarians and library users. It is critical for the content provider to dedicate resources and time towards their KBART files. The importance of knowledgebases and KBART files cannot be overstated. They are the backend of most journal A-Z lists and are essential for OpenURL link resolvers to provide targets for users to access authenticated content.

There are still several challenges in e-resource management including the time intensive manual selection of titles, the exclusion of some journal title history, incomplete journal transfer information, outdated linking, difficulty in identifying relevant collections or packages, lack of coverage for all content types, limited Open Access content, and erratic update schedules.9 The KBART Automation Working Group released a recommended practice in June 2019 to address the challenge of manual title selection by libraries.10 Originally developed by Elsevier in 2016, it was a proprietary means for communicating library holdings information to vendors. Later the NISO KBART Automation Working Group was formed, which included members from all stakeholder groups. The recommended practice dictated the terms for data delivery utilizing an application programming interface (API) to send library holdings data from a content provider on behalf of the library to a knowledgebase. For libraries that opted-in, the manual work required to reconcile their title level holdings in the knowledgebase was minimized. Current content provider participants are Elsevier, JSTOR, Ovid, ProQuest, Rittenhouse, SpringerNature, and Wiley. Implementation of KBART automation on the part of a publisher is very complex, but KBART Automation Recommended Practice providers a clear blueprint for sharing and ingesting metadata.11 Currently the number of participating knowledgebase providers is limited, but hopefully more will join in the future. The KBART recommended practices and KBART files form the cornerstone for communicating crucial title and institutional specific data among providers, vendors, and libraries. KBART files power library backend operations and influences front end discovery for library users.

COUNTER

Counting Online Usage of Networked Electronic Resources (COUNTER) statistics are found in the Evaluate-Monitor section of the e-resource lifecycle. COUNTER usage statistics are provided by content providers. This standard was launched in 2002 to improve the reliability of online usage statistics through codes of practice.12 This standard has gone through various releases and today the most current Code of Practice is Release 5.1.13 The COUNTER code of practice normalizes usage data for librarians and the COUNTER organization (formerly Project COUNTER) works with platform providers and publishers to ensure data is consistent and reliable.14

The Counter Code of Practice Release 5.0.2 is available at the COUNTER website and provides details about COUNTER reports.15 There are four types of reports provided in COUNTER usage statistics: platform, database, title, and item. A platform report provides usage from the platform, not the individual items subscribed or available on the platform. Database reports provide summary of activity related to a given database or fixed collection of content. Title reports provide summary of activities related to content at the title level and provide a means to evaluate the impact a title. This is where e-book and e-journal usage is found. Item reports give a summary of activity related to content at the item level such as streaming media content, or non-textual content like images.

The glossary found in the Counter Code of Practice Release 5.0.2 clarifies the meaning of terms used in COUNTER reports. Total item requests show collectively how many times a resource has been used regardless of whether by the same user. The unique item requests metric counts the first use by a user, which means although a user may have accessed a journal article more than one time the report will only record it once. Usage is tracked by log file analysis and page tagging or distributed usage logging (DUL).16 In the end, usage can be tracked across all platforms and content types. The reports help librarians make informed collection decisions across platforms to better redirect institutional funds to resources for users and are essential when making collection development decisions.

Available at the COUNTER website is the Release 5.0.2, The Friendly Guide for Librarians which provides useful scenarios to assists librarians in understanding the statistics and they best way to use them.17 For example, if a librarian decided to renew a subscription to the title Standards Monthly, they most likely referred to a COUNTER usage report like the one in Figure 7. This report also displays usage for the preceding title, Journal of Data Standards Society. Librarians must decide if the usage found in the report is worth the cost of the subscription. Evaluating statistics that are not COUNTER would involve librarians trying to compare a COUNTER usage report with a non-COUNTER report to find commonality and would require a judgement call as to whether the usage data is comparable.

Conclusion

Managing the lifecycle of e-resources requires transferring data at each stage. Standards permit transfer of data within and outside the library. Standards provide a common language that contributes to efficiencies and interoperability between systems. Without broad adoption of standards linking technologies would not function smoothly, procurement would be less automated, and evaluating usage of e-resources would be difficult. Standardization in the management of electronic resources helps publishers, vendors, librarians, and users.18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28

Contributor Notes

Beverly Geckle is the Continuing Resources Librarian, Middle Tennessee State University, Murfreesboro, TN, USA.

Matthew Ragucci is the Associate Product Marketing Director, Wiley, Hoboken, NJ, USA.

Ilda Cardenas is the Electronic Resources Librarian, California State University, Fullerton, CA, USA.

- Rob Biedron, “EDI Document Types and Transaction Types,” Planergy (website), accessed 8/15/2022, https://planergy.com/blog/edi-documents-types/. ⮭

- “EDI basics,” OpenText Corp, accessed 8/11/2022, https://www.edibasics.com/. ⮭

- “What is Electronic Data Interchange (EDI)?” IBM, accessed on August 11, 2022, https://www.ibm.com/topics/edi-electronic-data-interchange. ⮭

- Julia Reijnen, “Intro to EDI Standards & Subsets,” (2021) TIE KINETIX (website), accessed 8/11/2022, https://tiekinetix.com/en/blog/intro-edi-standards-subsets. ⮭

- Ibid. ⮭

- “About,” X12 (website), https://x12.org/. ⮭

- “What is Electronic Data Interchange (EDI)?” Union Pacific, accessed August 11, 2022, https://www.up.com/suppliers/order_inv/edi/what_is_edi/. ⮭

- “Understanding the benefits of EDI (Electronic Data Interchange)”, OpenText Corp, https://blogs.opentext.com/understanding-benefits-electronic-data-interchanges-edi/. ⮭

- John Mutter, “Parlez-Vous X12? Do You Speak EDI? A More Versatile Method for Electronic Ordering, Used in Other Industries, Should Soon Be Adopted by the Book Trade,” Publishers Weekly, November 9, 1990. ⮭ ⮭

- John Mutter and Bridget Kinsella, “Publishers Told ‘EDI or Die,’ ” Publishers Weekly 241, no. 17 (April 25, 1994): 25. ⮭

- “Faxon and Geac to Implement First EDI X12 Facility,” Information Today 11, no. 5 (May 1994): 51. ⮭

- “Endeavor, Harrassowitz Implement UN/EDIFACT for Serials,” Computers in Libraries 18, no. 1 (January 1998): 8. ⮭

- “EBSCO Information Services, Partnering with ExLibris. (Alliances & Deals),” Online, 27, no. 3 (May-June 2003): 14. ⮭

- “EBSCO and Endeavor Announce EDIFACT Invoice,” Information Today 15, no. 9 (October 1998): 58. ⮭

- “About,” EDItEUR, accessed July 24, 2022, https://www.editeur.org/2/About/. ⮭

- “KBART Phase I,” NISO, accessed July 31, 2022, https://www.niso.org/node/15671. ⮭

- “KBART: Knowledge Bases and Related Tools Recommended Practice,” NISO, accessed July 31, 2022, https://www.niso.org/publications/rp-9-2014-kbart. ⮭

- Adapted from “Figure 2: Flow of Data Through the Supply Chain,” in NISO/UKSG KBART Working Group, KBART: Knowledge Bases and Related Tools (NISO/UKSG, 2010), 6. ⮭

- “KBART 7.1: Recommendations and Further Discussion”, UKSG, accessed July 31, 2022, https://www.uksg.org/kbart/s7/next_steps/discussion#institutions. ⮭

- KBART Automation Working Group, KBART Automation: Automated Retrieval of Customer Electronic Holdings (2019), accessed July 31, 2022, https://groups.niso.org/higherlogic/ws/public/download/21896. ⮭

- Andrée Rathemacher, Matthew Ragucci, and Stephanie Doellinger, “Don’t Wait, Automate! Industry Perspectives on KBART Holdings Automation,” The Serials Librarian, 84, no. 1–4 (2022): 91–97, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0361526X.2022.2019545. ⮭

- Betty Landesman, “Taming the E-Chaos Through Standards and Best Practices: An Update on Recent Developments,” Serials Review 42, no. 3 (2016): 210–15, accessed May 9, 2022, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00987913.2016.1211443. ⮭

- Tasha Mellins-Cohen, COUNTER Release 5 Library Forum email listserv, July 12, 2022. ⮭

- Jill Emery, Lorraine Estelle, and Stephanie J. Adams, “COUNTER 5: Lessons Learned and New Insights Achieved,” The Serials Librarian 80, no. 1–4 (2021): 52–58, accessed May 9, 2022, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0361526X.2021.1884489. ⮭

- Counter Code of Practice Release 5.0.2, COUNTER, accessed May 9, 2022, https://cop5.projectcounter.org/en/5.0.2/. ⮭

- “Appendix A: Glossary of Terms,” Counter Code of Practice Release 5.0.2, COUNTER, accessed July 31, 2022, https://cop5.projectcounter.org/en/5.0.2/appendices/a-glossary-of-terms.html. ⮭

- “Logging Usage,” Counter Code of Practice Release 5.0.2, COUNTER, accessed July 31, 2022, https://cop5.projectcounter.org/en/5.0.2/06-logging/index.html. ⮭

- Tasha Mellins-Cohen, Release 5.0.2, The Friendly Guide for Librarians, (COUNTER: 2021), https://medialibrary.projectcounter.org/file/The-Friendly-Guide-for-Librarians. ⮭