It should come as no surprise that complex projects abound in library land. Project planning is a fascinating study area because comparing workflows and specific considerations across institutions of various sizes and specialties can provide practical guidance. It is essential to see what our colleagues are doing at their libraries. In this session, Willa Liburd Tavernier, MarQuis Bullock, and Savannah Price outlined a collaborative project undertaken by Indiana University (IU) Bloomington’s Herman B. Wells Library, the Neal-Marshall Black Culture Center Library, and the Lilly Library, Land, Wealth, Liberation: The Making & Unmaking of Black Wealth in the United States,1 which allowed students to learn about scholarly communication, Open Access, and digital collections. This presentation covered the following sections: Resources for Library Driven Projects, Student Perspectives, Benefits & Complexities, and Sustainability & Potential Future Uses.

Project Overview and Resources for Library-Driven Projects

The desire to contribute a more nuanced understanding of African American communities’ challenges was the impetus for this project. The understanding that marginalized communities may celebrate different milestones than those in power was essential to the work. These milestones are frequently overlooked in traditional K-12 education. This project looks at Black land ownership from 1820 to 2020. While expansive, this project is not comprehensive; it serves as a starting point for broader conversations about race and wealth in the United States. Given the focus on land providing information about the intersections of Afro-Indigenous populations was also essential, with the ultimate goal of this project being to foster an intercultural dialogue about the racial wealth gap that challenges the “bootstrap” narrative while using open and freely accessible digital materials for all researchers including the general public.

Liburd Tavernier, Bullock, and Price related that the “bootstrap” narrative denies that there is a larger system of power in place. The team further quoted Wilkerson (2020) who stated “… the caste system sets people at poles from one another and attaches meaning to the extremes, and to the gradations in between, and then reinforces those meanings, replicates them in the roles each caste was and is assigned and permitted or required to perform.”2 One persistent feature of the “bootstrap” narrative is that it points to the successes of other minority and immigrant groups.

Given this project’s scope, how and why might the library become involved in lifting marginalized voices? With the emerging focus on diversity, equity, and inclusion, libraries and librarians can be leaders in utilizing technology for restorative justice because of our connections with departments on our campuses and the larger research community. Libraries are critically evaluating how we handle collection development decisions. Liburd Tavernier framed this project through the lens of Trouillot’s philosophy that the past exists in its material traces and, therefore, that the past is a product. Trouillot’s (1995) work was referenced further by Liburd Tavernier when she related to those assembled that “inequalities experienced by the actors lead to uneven historical power in the inscription of traces … Sources are thus instances of inclusion, the other face of which is, of course, what is excluded.”3 Given this background information, libraries are logical partners to shine a light on the history of marginalized groups.

Liburd Tavernier pointed out that the library is ripe for curating and preserving digital materials for several reasons, including but not limited to the work of Black scholars in digital humanities, specifically regarding recovery.4 Libraries and museums are memory keepers and information providers, and we have an onus to facilitate intercultural communication. Projects such as this not only encourage that intercultural communication but also have broader cultural implications because they reframe our understanding of many topics—in this instance, American history.

Rather than a “traditional” timeline of American history—including the standard guideposts of The American Revolution, The New Nation, The Civil War and Reconstruction, among others—the Land, Wealth, and Liberation project presents a new, thought-provoking timeline to reframe the Black experience, specifically regarding land ownership and wealth. According to Liburd Tavernier, subject matter experts weighed in during every stage of this project. The project team benefited from representation across the Indiana University Bloomington Libraries with valuable initial framing provided with the assistance of DeLoice Holliday, the Multicultural Outreach Librarian and head of the Neal-Marshall Black Culture Center Library who became part of the core team and by nicholae cline the liaison to the First Nations Educational & Cultural Center and subject-specialist for gender and media studies. The rest of the core team included librarians from special collections and education, and the digital initiatives librarian consulted with the core team. Other contributors to the project team included subject specialists concentrating on map librarianship, archives, and African studies. This project frames American history through the milestones of The Missouri Compromise (1820–1864), Reconstruction to Tulsa (1865–1921), After Tulsa, the Great Depression & The New Deal (1922–1949), Urban Renewal (1949–1979), and The Neo-Liberal Economic Era (1980–2020). While this project has a national scope, local information germane to Bloomington is presented, including information about racial covenants dating back to the 1920s.

The history librarian consulted during the planning process to determine the scope of materials to include in the project. The project emphasized storytelling, especially stories that might not have been recorded elsewhere which were prioritized. Liburd Tavernier explained that although the project charter was revised a few times, there were clear roadmaps and timeframes for completing the project. Liburd Tavernier further mentioned that this material is heavy and traumatic; therefore, it was crucial for those participating in the project to have time and space to process their emotions. Viewing this material is heavy work, and the project leaders and student workers understood that breaks from processing materials were essential. The completed project presents a content warning as well as a link to the Unspeakable discussion guide created to assist educators while facilitating complex race-related discussions with their classes.

Student perspectives

One of the most salient aspects of this project was the opportunity it provided undergraduate and graduate students to learn more about Black digital humanities within the library world. Two students involved with the project, MarQuis Bullock and Savannah Price, shared their experiences during this session. The project team sought to engage students with marginalized history while learning new skills and technologies to prepare them to enter the workforce.

Price, an undergraduate history and gender studies major, said she was brand new to the technologies involved in this project and studying Black digital humanities. She mentioned it was enlightening to see the intersections of digital humanities and real-life situations. Price pointed out that the technologies she learned—such as Omeka S, Timeline JS, Audacity, and Zotero—made her more confident in sharing her research. She expressed that she is empowered to publish in the future and is exploring avenues in the Indiana Journal of Undergraduate Research. She further elaborated that working on his project has afforded her tremendous opportunities, such as speaking at a national conference while she was still an undergraduate student.

Bullock, a Master of Information and Library Science student at Indiana University with a records and archives management concentration, stated the following about the project: “you think about what the past could have produced, and what futures could have been created had Black Americans been given full autonomy over the direction of their lives after enduring one of the most fraught experiences—enslavement—in American history.”

Bullock also related the perspective of one of his fellow student workers, Rihonda Bing-English, a Master of Social Work student. Bing-English was quoted as saying “growing up in Bloomington, Indiana, a predominantly White community, I had zero information on these policies and history. I’m finding out about this now and processing it as an adult.” Liburd Tavernier also presented the perspectives of April Urban, a Library and Information Science Masters student, and Apoorva Chikara, a Master of Public Affairs student. Liburd Tavernier reported that Urban said, “making history publicly accessible is crucial to engaging communities, increasing understanding, and starting conversations.” This emphasizes the importance of the intersection of intercultural communications and how libraries can assist in fostering these meaningful conversations. Liburd Tavernier related that Chikara said, “humans are mortal. So are ideas. An idea needs propagation as much as a plant needs watering. Otherwise, both will wither and die.” This analogy was particularly striking when thinking about this through a diversity, equity, and inclusion perspective because libraries have many opportunities to “propagate and water” or plan, present, and even facilitate intercultural dialogue.

Benefits & Complexities

Library projects generate benefits and complexities regardless of the scope or goals. Liburd Tavernier discussed multiple benefits and complexities in this project. The benefits outweigh any complexities that the team encountered.

Among the benefits was using historical information to create a dialogue about a more inclusive society with the ultimate goal of working to disrupt and eliminate the “master” and “bootstraps” narratives. One of the essential benefits of this project is that it has a real-world impact and is open to the public. This project has the potential to have meaningful effects on researchers both locally and globally. Finally, this project has the benefit of increasing the skills of student workers, which has afforded them the opportunity to learn more about scholarly communications and digital humanities while preparing them for further research and to enter the workforce.

Some complexities encountered included having to process an overwhelming amount of information and presenting it in an easily digestible manner for others. There was also a technological learning curve with the Omeka S software. Carefully crafting research terms and phrases to describe resources proved incredibly time intensive. Liburd Tavernier also reported that there were many moving parts to the project that required higher level librarian intervention rather than easily being handled by student workers.

During this portion of the session, Liburd Tavernier conducted a short survey that gauged audience comprehension of critical digital collections and student-employee engagement in libraries. The survey questions addressed how this project would or could inspire librarians’ future work, how libraries’ strategic plans address historically excluded populations, preferences about the level of interest and expertise of student workers, the identities of student workers, and how libraries can incorporate marginalized communities outside of our institutions into this type of project. One theme quickly emerged from the answers to the final question: libraries should partner with organizations across and outside our institutions to further this work.

Sustainability & potential future uses

Liburd Tavernier, Bullock, and Price proved that this type of scholarly communications project is feasible and sustainable. Using the Land, Wealth, Liberation resource as a model, other libraries can determine diverse areas of their collections they would like to spotlight and prepare an interactive timeline as well as other media productions. Libraries’ growing attention to diversity, equity, and inclusion creates the perfect opportunity for such projects to thrive.

Easily adaptable to many types of libraries, not just academic ones, this project is a fantastic example of how libraries can connect and collaborate with community partners to amplify marginalized voices. Libraries also have an excellent opportunity to highlight marginalized communities and facilitate an effective intercultural dialogue.

Questions & answers

During the Question-and-Answer portion of this session, Price related that she spent October to May learning more about her home state, Kentucky. Price related that she believed she knew about a popular recreation area, Kentucky Lake, but that a hidden history emerged during her research. Price further shared that working with this project taught her how to research and use critical thinking and evaluation skills.

Bullock elaborated that this project helped expand the historical presence of people of color, specifically of African descent. This project encouraged him to participate in Open Access projects beyond graduate school and enabled him to visualize a future for himself in libraries that had not been as clear as when he started his MLS program. He related that he would love to generate a project about Black culture in the future.

One audience question that was particularly thought-provoking was about determining the scope of the project, specifically regarding what to include and omit. Liburd Tavernier related that there were ongoing and frequent consultations with the project team to define the timeline while conceptualizing how the project talks about land.

Final thoughts

The Land, Wealth, Liberation project is a model scholarly communications projects for other libraries to emulate. Libraries have a renewed interest in diversity, equity, and inclusion, and this project could spark conversations within libraries about uplifting marginalized voices. To foster intercultural dialogues, librarians must lead the way in reframing historical events by highlighting diverse voices within their collections. Librarians also have tremendous opportunities to engage community partners through targeted outreach.

Appendix

During this presentation, Liburd Tavernier sought audience participation using a Qualtrics poll.

The following are the questions and their respective answers:

Question One:

“In what ways does this project inspire you for your own work? This question was a free text box and generated a word cloud. (See Figure 1)

Questions Two:

“Do you have a strategic plan that identifies supporting historically excluded portions as an explicit goal?” Choose all that apply (See Figure 2)

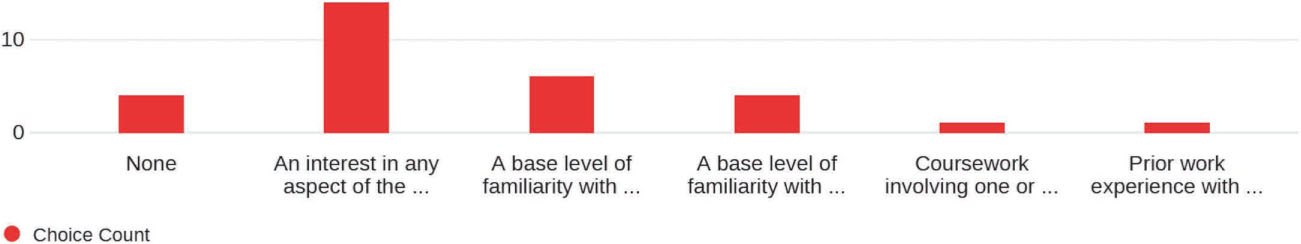

Question Three:

“What level of subject-area knowledge do you EXPECT students to have before you hire them? For scholarly communications librarians, this may include digital librarianship, open access, open educational resources, library publishing, institutional repositories and more.” (See Figure 3)

Question Four:

“What level of subject-area knowledge do you PREFER students to have before you hire them? For scholarly communications librarians, this may include digital librarianship, open access, open educational resources, library publishing, institutional repositories and more (See Figure 4)

Question Five:

“To the best of your knowledge in the past 5 years how often has your department hired students who identify as: Indigenous, First Nations, or Native American, A member of the LGBTQ2S+ Community, Black, a person of color (other than black or indigenous), biracial or multi-racial, white” (See Figure 5)

Question Six:

“How can we incorporate persons from marginalized communities outside of our institutions in this type of work?” (Live audience responses)

Our dept could do more outreach to students’ campus communities

More examples of people who like these persons working at the library

Be very open about what counts as experience

Volunteer opportunities projects that are well advertised to the public and call for participation

Recruitment

Recruit widely. Target marginalized groups (through word of mouth, and partnerships with marginalized student groups.

Partnership with community organizations and advocacy groups

Spend more time creating projects in those communities. Offer opportunities to gain new digital skills that may in turn entice them to consider libraries as a future.

By working with other departments such as LGBTQ+

However, we haven’t hired any student workers since I have been at my institution in my department since 2018.

Hosting events that would interest them and bring them into the library

Volunteer opportunities, reaching out to the community and being visible in the community as a resource.

I think the best way, like much of anything else, is just conversations. It allows everyone the opportunity and gives us the chance to invite/introduce everyone to these options.

Outreach and advertisement in the local townships

In our case we are working toward diversifying the campus as a whole

Promote the positions via marketing channels that persons from marginalized communities are aware of

I’m not sure.

“Did you take this survey as part of a Conference Presentation?”

Question Seven (B):

“Can we email you if we want to follow up on this work?”

Contributor Notes

Willa Liburd Tavernier is Research Impact & Open Scholarship Librarian at Indiana University Bloomington.

MarQuis Bullock is a graduate student in the Information and Library Science Program (ILS) in the School of Informatics, Computing, and Engineering at Indiana University Bloomington.

Savannah Price is an undergraduate in the Bachelor of Science in History and Gender Studies Program at Indiana University Bloomington. Price is also a Herman B. Wells Scholar.

Michelle Colquitt is Continuing Resources and Government Information Management Librarian at Clemson University, in Clemson, South Carolina.

- “Indiana University Bloomington,” Digital Collections at Indiana University, 2022. https://collections.libraries.indiana.edu/iulibraries/s/land-wealth-liberation/page/introduction. ⮭

- Isabel Wilkerson, “An Old House and an Infrared Light,” in Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents, (Random House, 2020), Chapter 2, p. 19. ⮭

- Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Boston: Beacon Press, 2015). https://hdl.handle.net/2027/heb04595.0001.001. EPUB. ⮭

- Kim Gallon, “Making a Case for the Black Digital Humanities,” in In Debates in the Digital Humanities, Version 2.0, ed. M. K. Gold, & L. F Klein (University of Minnesota Press, 2016). ⮭