Introduction

David Bordwell notes a chess motif in the mise-en-scène of Tomas Alfredson’s Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (2011), manifesting in production design in ways that connect the film’s aesthetic to its espionage theme: “the imagery (with the briefing room as a gridded checkerboard) reminds us that spying, known for decades as The Great Game, is now a global chess match”.1 This article develops Bordwell’s idea to argue that the motif of the grid or box is common in the espionage thriller in both cinema and television. Adapting Bakhtin’s chronotope, 2 the article demonstrates how setting, set design and camerawork intersect to underpin narrative structures and visual metaphors. It connects production site to construction of onscreen space to consider the visual style and metaphoric function of these Cold War spaces on screen. The article concludes that a stable Cold War “chronotope” informs these screen texts, while the mise-en-scène is permeated by the motif of the grid or box.

The article first discusses the concept of the chronotope and demonstrates its utility in analyzing the narrative spaces of screen texts. It then discusses Weber’s “iron cage” of modernity3 and explores its connections to modernist architecture and the motif of grids and cages, both material and symbolic. It then analyzes how this motif is expressed in The IPCRESS File (Furie 1965), Spooks (BBC 2002-2011) and Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (Alfredson 2011). It then conducts a visual analysis of The Game (BBC 2014) before offering some conclusions about the Cold War chronotope and the cage motif in all of these productions.

The Chronotope

Literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin applied the term “chronotope (literally ‘time space’)” to “the intrinsic connectedness of temporal and spatial” in literature4. In concretizing the time and space of a novel’s events, the chronotope makes possible the representation of the abstract events of the novel. For Bakhtin, the most obvious significance of the chronotope was its effect on narrative. Chronotopes are “the organizing centers for the fundamental narrative events of the novel. The chronotope is the place where the knots of narrative are tied and untied”.5 Bakhtin was discussing literature, but the chronotope can be applied to cinema too. Lee Wallace comments “Narrative theory has long recognized that the place in which a story occurs is never a neutral backdrop but has an instrumental relation to the story it ostensibly foregrounds”.6 The chronotope is a site from which particular situations, themes and characters habitually emerge. It is therefore useful for understanding the conventional settings of particular genres: “the chronotope is a tool for synthetic analysis, not only for identifying and reasserting the force and information of concrete space on the temporal structure of the novel but also for comprehending historically the phenomenological relation between text and context in a way richer than that afforded by traditional generic analyses”.7 Never merely a backdrop to narrative, the chronotope is intrinsically part of how narrative works as setting gives rise to action.

Michael Montgomery criticizes the generality of Bakhtin’s “master chronotopes” and suggests that any chronotopic analysis needs cultural specificity. New chronotopes illustrate social change and emergent social spaces within wider cultural contexts; Montgomery identifies the shopping mall as a key chronotope for 1980s cinema.8 Sobchack builds on Bakhtin’s salon chronotope to identify the cocktail lounge and/or nightclub as a key film noir setting. What emerges in Sobchack’s analysis is the “lounge time” chronotope, which incorporates such public but anonymous sites as the cocktail lounge, the nightclub, the hotel room, the diner, the roadside café, and the motel. In contrast to the respectable domestic spaces of the home, these sites of aimless time and transient space give rise to louche characters and particular sets of, often criminal, activities.

In another example, Wallace examines the settings of five lesbian-themed films in order to “attend to the way in which cinematic space produces the lesbian story” through the apartment chronotope.9 The bar and schoolroom constitute further lesbian chronotopes, with more to come as social change advances. Settings and narrative are therefore intrinsically linked and involve a dialectical relationship between genre and dramatic site. The chronotope demonstrates “how concrete spatiotemporal articulations generate narrative structures, figures, characters, and tropes”.10

This article argues that the Cold War thriller is a genre located within a particular range of settings which generate such narratives, characters, and tropes. It uses the concept of the chronotope to examine setting, design, and mise-en-scène in a range of British screen dramas dealing with the Cold War, espionage and conspiracy. I have argued elsewhere that Cold War narratives deploy the “Iron Curtain discursive unconscious”, to construct the marginal, peripheral spaces of Communist Eastern Europe.11 This visual chronotope constitutes material onscreen space from sets of generic signifiers forming the internationally recognized landscape of Cold War narratives. I expand this idea to argue that the Cold War dramas discussed here incorporate these settings into a wider chronotope incorporating bureaucratic offices of state, English gentlemen’s clubs, shabby safe houses, cheap hotels, and drab domestic interiors. In addition, the dramas discussed here are linked through mise-en-scène to the motif of the cage.

Weber’s “Iron Cage” of Modernity

The sociologist Max Weber is famous for his conception of modern, capitalist society as a “cage”; 19th century Fordist production and rational planning led to rapid social change and the emergence of a bureaucratic society concerned with disciplining the newly emergent masses concentrated in cities. Modern state planning and consumption are linked in this model: “increasing bureaucratization is a function of the increasing possession of goods”.12 Bureaucracy is also interested in its own continuation and, in the secrecy of its workings, has a precarious relationship with democracy.13 It is the invisible bureaucracy of state surveillance, and the internal workings of those bureaucratic systems, which much spy fiction depicts.

According to Edward Tiryakian, Weber did not actually use the term “cage” and this translation is attributed to Talcott Parsons.14 However, the “cage” is such a useful metaphor for the disciplinary nature of modern life that I continue to use it here. The cage is a metaphor for the entrapping, bureaucratic nature of modern capitalism, including the unending cycle of production and consumption. Toby Miller argues that spy stories on screen function hegemonically as part of a process of mirroring “repressive state apparatuses” (army, police, prisons, bureaucracy) via “ideological state apparatuses” (church, school, media).15 Miller specifically uses the cage metaphor to describe the way in which the production and ideology of such fictions are imbricated in hegemonic assumptions about capitalism: “both the processes and the contents of espionage cinema and TV appear intensely problematic, caught in a cage of capitalist normalcy. They are pro-state and pro-capital – to repeat, an ISA representation of the (R)SA”.16

The “Great Game” of espionage is thus represented thematically via tensions between Communism’s rational state planning and the excess of commodity capitalism. Frequently, this theme is visually represented through the motif of the grid. Miller connects Weber with grid imagery in his account of class in capitalist society, invoking “the Weberian stress on position within the labor market and the additional grids of status and authority”.17 In material terms, the geometric grid is essential to the rationalization of modernity, particularly in urban planning and architecture such as Haussman’s modernization of Paris boulevards and the planning of many American industrial cities.18 Modernist housing is also planned around geometric grids, rectangles and boxes, such as Le Corbusier’s Unité d'habitation block in Marseilles.19 Deriving from earlier forms of Modernist architecture, Unité d’habitation represents “the birth of Brutalism”,20 defined as “an uncompromising modern form of architecture which appeared and developed mainly in Europe between approximately 1945 and 1975”.21 Brutalism is characterized by sometimes monumental use of modern materials – glass, steel, concrete – and connotations of state planning, socialism and social-engineering. Its use of bare rough-cast concrete (béton brut) lends it an “unfortunate reputation for evoking a bleak dystopian future”.22

Many critics note the contradictory and ambiguous relationship between modernity and the individual with rational planning seen as dehumanizing and oppressive, eradicating “authentic” organic communities and fitting subjects into boxes both metaphorical and literal.23 Haussman’s Paris boulevards were good for commercial and military transport, but less welcoming to the individual citizen. Boxes and grids are recurrent visual symbols for conveying the alienating, entrapping conditions of modernity throughout many espionage screen fictions, as this article now discusses.

“Low-ceilinged Paranoia”: The IPCRESS File

Pasquale Iannone24 notes the proliferation of grids and boxes in the visual design of The IPCRESS File (Furie 1965). The film, based on Len Deighton’s novel, is in the mold of espionage novelist John Le Carré’s morally dubious universe: what Oldham25 calls the “existential” anxiety of the realist spy thriller, asking “what if ‘we’ are just as bad as ‘they’ are?”.26 Recruited by a secretive branch of the MoD to locate missing scientists, working-class agent Harry Palmer (Michael Caine) is kidnapped and subjected to brainwashing in what he thinks is Albania. Escaping, he finds he is still in London and has been part of a plot to flush out a double agent in the secret service. Critics have discussed the film’s striking cinematography: “Director Sidney J. Furie and cinematographer Otto Heller’s complex visual approach, which frequently involves obscuring the main action through crowding the foreground of the image with everyday objects, greatly adds to the suggestion of a world of hidden secrets and unknown truths”.27

Similarly, Miller notes the noirish style and canted angles of the cinematography, and how looming foreground objects suggest danger.28 Iannone points out the division of the screen within Furie’s manipulation of the widescreen format. Door frames, doors, windows, bookcases, room dividers, kitchen cabinets, bookshelves, pillars, and stair railings divide interior space up into grids and confine characters behind bars. In the Science Museum library, Palmer is seen behind balcony railings. When Palmer suspects intruders in his apartment, stark noirish banister shadows turn his hallway into a cage. The camera peers through the police cell’s door grille. In the office, Jean Courtney (Sue Lloyd) is filmed through her wire mesh wire in-tray, drawing attention to the bureaucracy of spycraft. Even spacious exteriors become claustrophobic through mise-en-scène. Narratively unmotivated shots from behind telephone boxes turn exterior space into confining cages, the screen divided into a grid confining characters within their separate boxes. Shots through telephone box windows, car windscreens, or spectacle lenses place glass layers between the camera and the characters, isolating them in frames-within-frames and behind transparent walls, visually suggesting the surveillance theme. A point-of-view shot of Palmer’s myopic vision without his glasses blurs the image, suggesting the opacity of the plot and the moral ambiguity of spycraft29.

Ceilings are prominent in the film’s mise-en-scène, such as the underground car park where protagonists exchange hostages, suggesting modernity’s oppressive psychological weight and the entrapping nature of spycraft: visually conveying “low-ceilinged paranoia”.30 In the supermarket, symbolic site of American capitalism, the grid of the ceiling tiles is prominent, subliminally connecting modernity and consumerism as a social and cultural cage. Square ceiling lights turn the grid into a gaming board, anticipating Bordwell’s checkerboard motif.

When Palmer goes on the run, the grid motif continues. In Jean’s flat, the wallpaper’s diamond-patterned trellis turns the supposed sanctuary into a cage, and foreshadows that she will contact Colonel Ross (Nigel Green) who is suspected of being the double agent. Towards the film’s end, the brainwashing sequence sees the grid motif of earlier scenes tighten into a box as the trap closes on Palmer. The brainwashing space is a large cuboid within a prison-like warehouse, a room within a room with hard verticals creating another confining box; space becomes a confining 3D grid. During processing, Palmer is observed by the brainwashing scientists on a monitor screen, another entrapping box creating a frame within the frame and materializing the theme of disciplinary surveillance.

Palmer escapes and rings his office, using another telephone box – visually suggesting that he is still “caged” by the effects of brainwashing. He looks into the small mirror inside the box, which recalls his face on the monitor screen during processing and highlights that the brainwashing may have affected his sense of self. When the two suspected traitors meet him in the final warehouse scene, they stand on either side of a hard vertical line on the wall. After the traitor is killed, another strong background vertical – a prominently lit beam supporting the staircase – visually separates Ross and Palmer when Palmer says “You used me as a decoy. I could have been killed or driven stark staring mad.” But he reaches his bloodied hand out across the beam to Ross, signalling the restoration of an uneasy trust through breaching of the vertical line. The film’s visual design – grids and boxes in set design and shot composition – is thus explicitly connected to its narrative and theme.

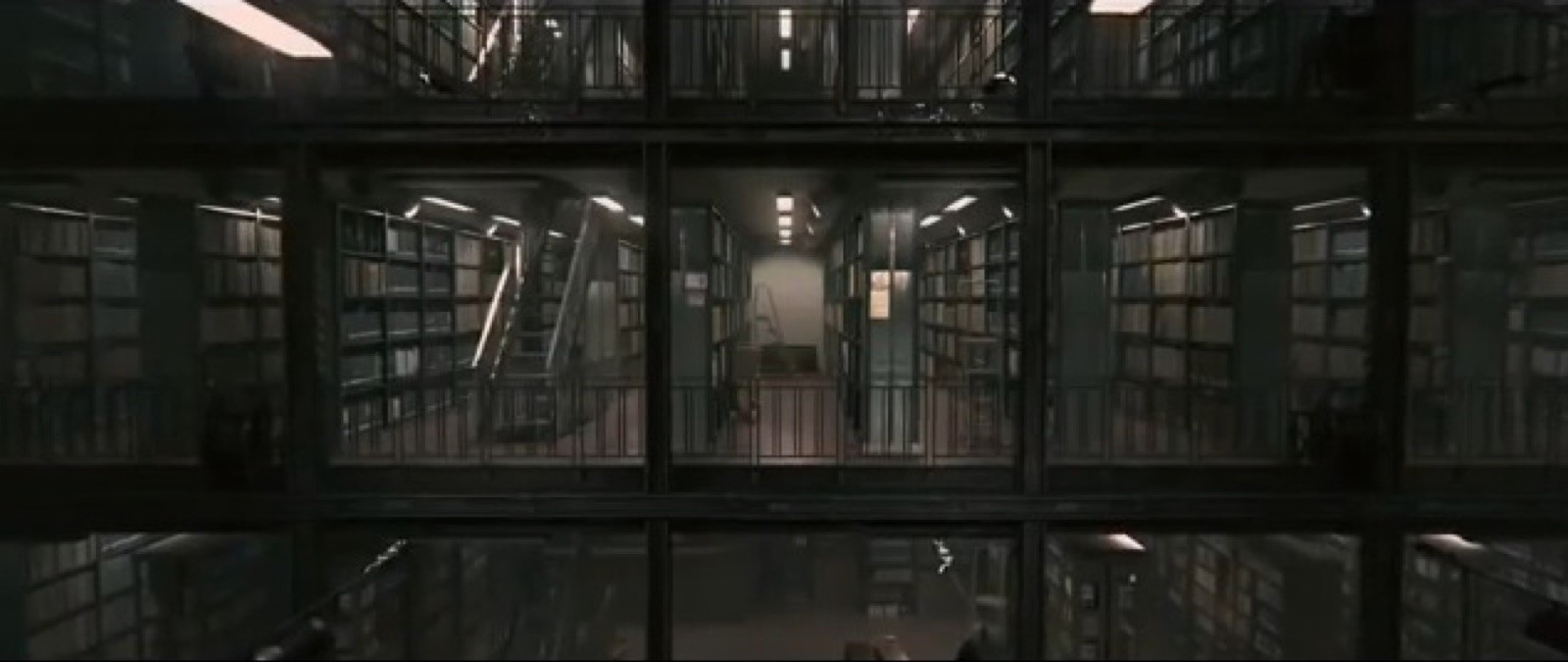

Similarly, the cinema version of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (Alfredson 2011) also features grids and boxes. David Bordwell links this motif to a chessboard used early in the film to set out the suspected “moles” (spies) within the Secret Service, with the checkerboard effect of orange pyramidal soundproofing foam on the “Circus” headquarters briefing room walls making visual reference to spying as the “Great Game”.31 Elsewhere, I have developed Bordwell’s observation to demonstrate that this motif is an integral element throughout the film’s mise-en-scène. Where the 1979 BBC television adaptation tended to use small, shabby office rooms and safe houses as claustrophobic settings, the cinema version uses much larger scale locations which, nonetheless, trap characters within the “Great Game” through a rooms-within-rooms motif. This is expressed in the Brutalist Secret Service building concealed within the Edwardian Baroque façade of Blythe House (1899-1903), through freestanding office modules within the expansive Circus interior, and through a grid motif integrated throughout the film’s visual design:

the 2011 film does not rely on compressing characters into shabby, claustrophobic rooms, but instead turns its more expansive cinematic spaces into grids, constructing space as a series of layered frames to suggest observation and entrapment. Characters are isolated either within intradiegetic frames, behind transparent layers, or both [...] The film traps its protagonists by using transparent layers and intradiegetic frames to divide the screen; even expansive cinematic space becomes a cage.32

Jane Barnwell similarly notes how grids throughout the film contribute a “labyrinth” motif, and how production design and mise-en-scène create “divisions, grids and compartmentalization of space and character”33. Shots through windows create “rigid lines that box in characters” and glass “reflects and creates disorientating space”. For Geraint D’Arcy, the transparent layers convey that “privacy is an illusion”.34

Grids and boxes similarly proliferate throughout the visual design of the screen dramas discussed here to create the effect of a cage motif, suggesting that The IPCRESS File casts a long shadow across the visual conventions of the Cold War drama. This motif is evident in television depictions of espionage, such as the BBC’s Spooks (2002-2011).

Spooks (2002-2011)

Spooks responds to the changing landscapes of both post-Cold War espionage and the broadcasting industry.35 With the fall of the Soviet Union, MI5 largely reoriented itself from counter-espionage (against Russia) to counter-terror (post-9/11). Spooks was devised by production company Kudos as a new popular series, and a state-of-the-nation spy drama commenting on current events and therefore focused on counter-terrorism. As Joseph Oldham explains, the series is organized around a setting actually named The Grid – an open plan “precinct”36 space, a central institutional setting around which narratives revolve and to which characters return after adventures. Technical advances in the 21st century mean that information comes into the Grid for processing by the characters, who thus don’t need to go out much. This enables a focus on the procedural and technical side of espionage, particularly in terms of the surveillance state, and therefore addressing issues around privacy, data, and surveillance of citizens in the internet age. Weber’s bureaucratic cage is thus dramatized on screen through the activities of the agents. As Oldham demonstrates, this interest in surveillance and data is reflected in Spooks’ distinctive visual aesthetic of split-screen following several strands of action at once.

Split-screen functions as another form of grid or cage isolating characters within onscreen rectangles. For example, in episode 1:1 as characters enter the Grid, grids feature both within the diegesis and as part of the mise-en-scène, where the split-screen effect divides the television frame into separate boxes, and highlights surveillance since this split-screen comprises CCTV images. For Oldham, the combination of “cinematic” visual style – single camera, tilted angles, rapid focus changes, expressive lighting – and the “televisuality” of ostentatious, distracting split-screen and CCTV aesthetics is a factor in an increasingly competitive television landscape.37 However, the grids and boxes of split-screen continue the cage motif and, intercut with shots of CCTV cameras, explicitly connect this motif to the theme of surveillance. Within the Grid, computer and video screens further subdivide the diegetic space into rectangles, prefiguring Bordwell’s “checkerboard” and expressing the flow of information into the Grid as a form of video game. This constitutes what Oldham calls “paranoid style”, a visual excess of data. Boxy wall shelving within the Grid continues the grid motif. Glass walls and internal windows also subdivide the space with transparent layers, and reflections make place unstable and liminal.

Oldham points out a key visual binary within the settings of Spooks. While the precinct interior of the Grid is high-tech, high-contrast ultramodern, it has an imposing Art Deco exterior. MI5’s real-life original base was Thames House (1929-30), but in Spooks it is played by the vaguely neoclassical, Art Deco Freemasons’ Hall (1927-1932) in Covent Garden, redolent of Whitehall bureaucracy. The tension between 21st century high-tech interior and 1930s Establishment exterior parallels the Brutalist office block concealed inside Edwardian Blythe House in Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (2011). Another Establishment space which regularly figures in Spooks is the gentleman’s club. To invoke the chronotope again, narrative tensions play out across a structural opposition between old and new spaces, a chronotope of technological modernity versus Establishment antiquity. In this kind of series, “aristocratic characters and high-culture environments typically serve as a shorthand for entrenched power elites with cynical or authoritarian tendencies”.38 This space recurs in a number of espionage dramas and can therefore be considered part of the Cold War chronotope.

The chronotope of the espionage drama therefore comprises settings such as bureaucratic offices, high-tech sites of surveillance, monolithic Establishment architecture, and aristocratic heritage spaces. These spaces recur in the next example, Cold War thriller The Game.

The Game (2014)

Produced by BBC Cymru Wales, The Game (2014) is set in 1972 and concerns MI5’s quest to prevent the KGB from initiating the mysterious “Operation Glass”. Across the serial’s six episodes, Operation Glass takes on different forms; initially presumed to be a planned nuclear “accident” on British soil, it transpires that Operation Glass involves the assassination of the Prime Minister and the activation of high-ranking sleeper agents in the British government. Woven into this narrative is the search for a “mole” within MI5.

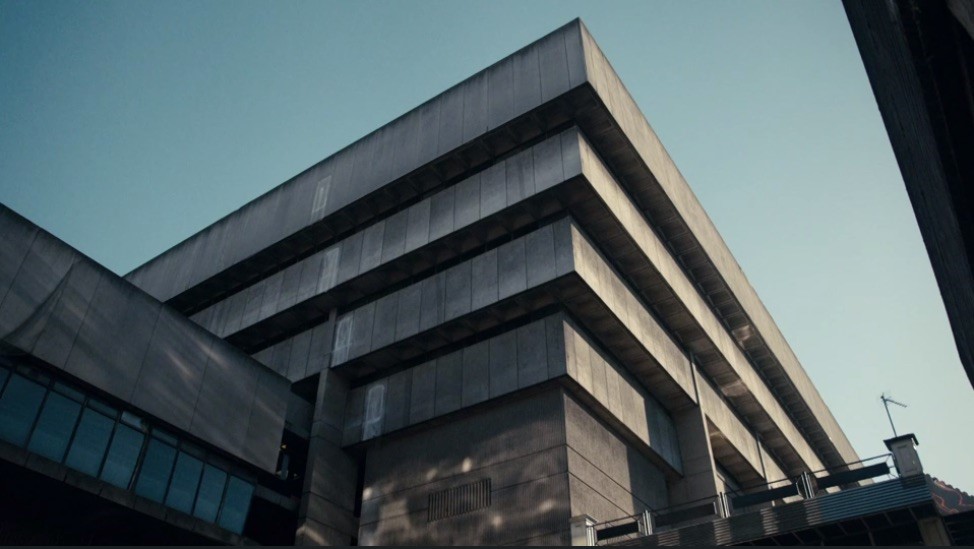

The Game was mostly shot in Birmingham locations such as Moor Street Station, Moseley Road Baths, Cannon Hill Park, and the Central Fire Station.39 The Game’s version of MI5, nicknamed “The Fray”, is based in John Madin’s Brutalist Birmingham Central Library, opened in 197440 and demolished shortly after the drama completed shooting. The “Stalin-style”41 building resembles the modernist “Circus” in 2011’s Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy. Jonathan Meades argues that “Brutalism was the cold war's architectural mode, on both sides of the Iron Curtain – Mutually Assured Construction”.42 The choice of this “inverted ziggurat” (Glancey 2003)43 may be a nod to the current MI5 headquarters in Vauxhall. To protect books from daylight, the Birmingham library had limited window provision, giving it an inscrutable, armored exterior. Alan Clawley comments “On the outside the windows are restricted to narrow high-level strips, but the central atrium is completely glazed behind deep concrete balconies”.44 The interior was built with bush-hammered columns and coffered ceilings,45 square concrete panels with deep sunken recesses in a grid pattern. The series’ interior headquarters was situated within a central atrium with multiple balcony levels, a space which functions as a “precinct” around which the plot revolves.

Urban planning journalist Amanda Kolson Hurley explains:

The BBC crew built a number of sets inside the "fantastic basic structure" of the library, bringing in new items but also making use of existing bookshelves and other "stuff that was lying around," says the show's production designer, Michael Howells. They painted walls in dull blues and grays, and for the offices of the senior MI5 officials, carefully chose objects—a golf tchotchke for one, contemporary art for another—that suited the respective characters.46

The domestic spaces of The Game are largely designed and lit in drab, faded oranges and beiges – recalling the “rusting” British Empire47 and “paisley and brown nylon”48 “1970s theme park”49 of the 2011 Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy. The Fray, however, is largely grey concrete with blue accent panels and black sound-insulation foam, connoting modernity. As Owen Hatherley notes, in the British imaginary, 1970s concrete Brutalism frequently connotes state subsidy. Urban planning and modernist architecture were seen as techniques for disciplining the unruly city, and the myths of Brutalism focus on the oppressive quality of such buildings as connoting “the inhumanity of totalitarian modernism”.50 State provision is associated with Soviet life behind the Iron Curtain, and the Brutalist building at the narrative’s heart therefore hints at the parallels between MI5 and the KGB.

In the serial, the library’s central atrium area features rows of desks at which administrators sit, and a montage of staff using rubber stamps and typewriters in episode one conveys Weberian bureaucracy as well as Oldham’s “authenticity through a new emphasis on documentary detail and procedure”51 in the espionage drama. Glassed-in offices and meeting rooms around the ground floor and first-floor atrium balconies create transparent boxes within the modernist interior. The vertical supports of the internal windows subdivide space further, providing grids within which characters are trapped; visually situating them within these squares marks them as players in “the game”.

The sunken squares of the coffered ceiling create a concrete lattice which is frequently visible in shot, acting as a grid backdrop to characters in low angle shots, and broken up by square lights which recall the supermarket ceiling in The IPCRESS File. Regular use of one-point perspective, similar to the visual composition of much of the Tinker Tailor movie, turns expansive space into confining boxes.

The interior walls are largely corrugated cast concrete, the vertical lines of which evoke the bars of a cage and turn the Fray into a prison-like space. Wall panels in the Fray are lined with black pyramidal acoustic foam which provides a visual link to the orange foam in Tinker Tailor, subdivides these panels into much smaller grids, and creates a slightly threatening effect of square spikes.

Blocking of actors and shot composition make interesting use of this space. Long shots of characters seen through windows confine them within the space, and suggests the theme of surveillance. Nicholas Barnett uses Alice Chess to analyze The Game, noting a gameplay motif in the mise-en-scène, with characters framed in medium shot resembling chess pieces, a London square acting as a chessboard, and subplots forming other boards.52 Mise-en-scène also indicates the instability of identity in the world of espionage. In publicity material, Tom Hughes, playing undercover agent Joe Lambe, explains that characters are not what they seem: “Joe is the type of character that you come across very rarely - on the surface one person, but inside someone entirely different”.53

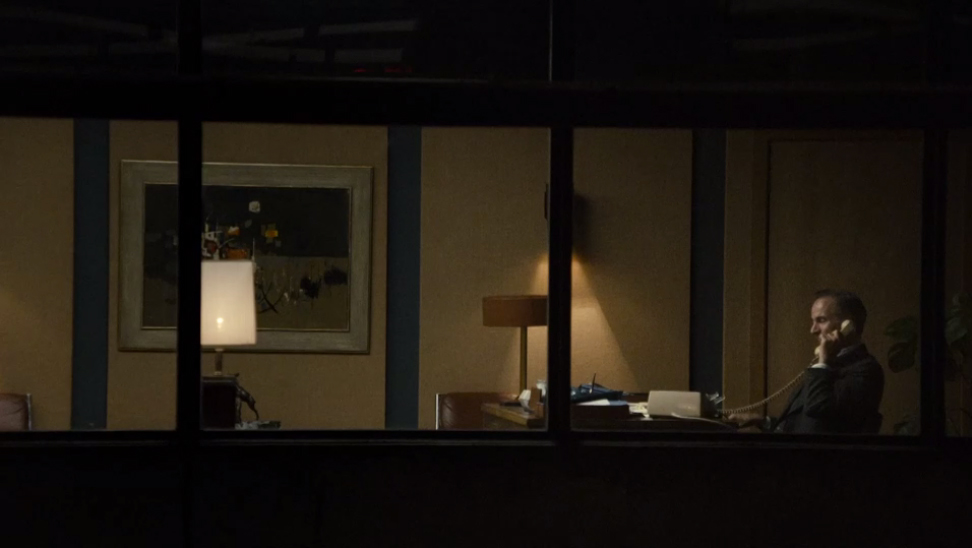

At the end of episode two, a wide shot of MI5 head “Daddy”’s office window from the far side of the atrium reveals precise arrangement of characters. The vertical frames divide the wide horizontal window into five squares. Shy newcomer Wendy (Chloe Pirrie) is in the extreme left-hand square, with awkward technician Alan (Jonathan Aris). “Daddy” (Brian Cox) and his protégé Sarah (Victoria Hamilton) are in the next pane, suggesting their shared loyalties. Ambitious, unpopular Bobby (Paul Ritter) is alone in the next, and brooding Joe (Tom Hughes) occupies the right-hand square. This symmetrically arranged one-point perspective shot, with the concrete ceiling grid prominent with selected square lights illuminated, suggests again the board of the Great Game. It also arranges the characters according to personal loyalties and tensions. Furthermore, the separation of characters into isolating frames hints at the secrets they are concealing from each other. “Daddy” is planning to help a Chinese ballerina defect; Sarah is a KGB spy; Bobby is a closeted homosexual; Joe is obsessed with the KGB agent who shot his lover Yulia (Zana Marjanovic).

Careful use of camera angles puts the architecture of the Fray to expressive use at specific narrative moments. When Bobby is linked with homosexual blackmail, “Daddy” summons him to discuss it. The scene starts with a symmetrical one-point perspective wide shot of the office with “Daddy” and Bobby at opposite sides of the screen, giving them equal authority at this stage of the scene. As the dialogue progresses, a low angle shot of Bobby, framed against the square concrete tiles of the ceiling, draws attention to the prison-like quality of the architecture. The texture of the grid behind his head acts as a cage-like framework showing his social and professional entrapment; the sunken panels of such a ceiling are “caissons” or boxes. The image of the entrapping “box” of the closet is evoked in the dialogue, as “Daddy” says “Trouble is, once these things are out there it’s not so easy to put them back into their box now”. Design, camerawork, and dialogue combine to inform the underpinning themes of the scene.

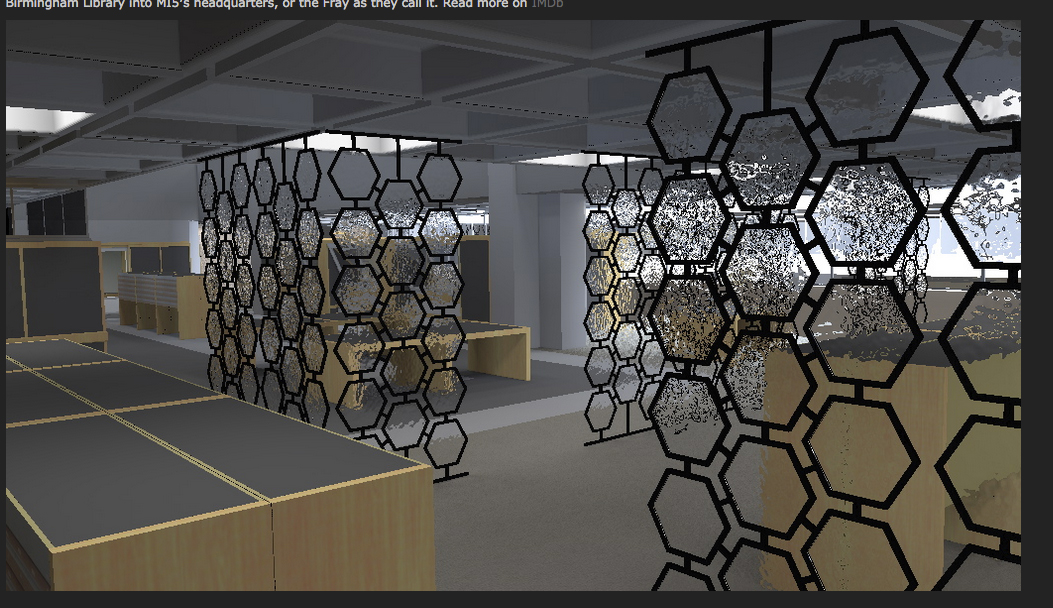

Another design feature within the Fray takes the form of decorative room dividers made up of framed rectangular pebble glass panels. These continue the grid motif, and characters are viewed from behind the panels. The distorting pebble glass suggests the blurred morality of spycraft and recalls Palmer’s myopic vision in The IPCRESS File. Visualizations of production design concepts at www.fabricespelta.com54 indicate that these panels were originally intended to be hexagonal, suggesting that the grid motif is at least partly subconscious, or else that the hexagons were rejected in favour of grids.

Mirzoeff notes that much modernist architecture is functional in intention and designed around control of its subjects through surveillance: “The key to this visualized system was that those who could be observed could be controlled”.55 Foucault uses the concept of the panopticon to explore institutional architecture as determining social control, examining spatial and temporal structures regulating individuals within scopic disciplinary regimes.56 Panoptic regulation applies to institutions such as schools, hospitals and factories (and, through CCTV surveillance, public streets). Segmentation and surveillance of space becomes vital to social power in modernity as observed subjects discipline themselves. The Fray is a panoptical space, materially embodying the serial’s themes of surveillance, mistrust, and concealed identities. With its small exterior windows but extensive use of interior glass, this panopticon is an inward-looking one, suspiciously disciplining its own subjects. Given the visual and narrative themes of surveillance and (lack of) transparency, it is perhaps no coincidence that the KGB plot is called Operation Glass, suggesting moral equivalences between the KGB and the team in the Fray. British post-war urban planning has been called “municipal Stalinism”,57 demonstrating its ongoing association with state socialism. The Game is thus an “existential thriller” in which “‘we’ are just as bad as ‘they’ are”.58

And yet, the sets are not purely, sterilely modernist. “Daddy”’s office in particular is decorated with brown leather sofas and mahogany bookcases, suggesting his connections to the old Establishment and relieving the concrete and blue of the Fray. Hurley sees a domestic quality in the space:

The Game humanizes Brutalist architecture. It makes Brutalism the scene of interactions that for once aren't thuggish or sinister.

The show's set design helps, warming up the concrete with furnishings in jewel and earth tones. Leather sofas, paintings, bookshelves, and lamp lighting make the spy agency seem not quite domestic, but lived-in.59

Hatherley complicates the idea of concrete modernism as unremittingly cold and constraining, arguing that “achingly fashionable” Brutalism is now celebrated as “futurist nostalgia”.60 There are interesting tensions at work then between the Fray as repressive Panopticon, and as site of stylish 1970s retro-modernity for the eyes of a 21st century audience.

Grids and Cages outside The Fray

The imagery of cages, grids and boxes recurs throughout the serial in spaces other than the Fray. In episode 2, Soviet sleeper agent Arkady (Marcel Iureș) attends a dead letter drop in a public lavatory surrounded by railings. The lavatory cubicles form further rooms within rooms, and the ceiling is slatted like prison bars. Later in the episode, sleeper agent Tom Mallory (Steven Macintosh) is shown against white wood paneling, the wall creating a lattice behind him foreshadowing that he is also in “the Game”. Episode 3 shows Joe taking his lover Yulia home; Joe’s shabby flat inexplicably contains the frame of a stud wall with no paneling. The skeletal grid here suggests barriers between spies and the people they love. Red telephone boxes feature regularly, both as a signifier of Cold War London but also as another form of cage recalling The IPCRESS File’s ostentatious shots through telephone boxes. In episode 3, suspected spy Catherine (Rachael Stirling) has room dividers in her flat which signify 1970s décor, but also recall Palmer’s apartment in IPCRESS, and like the skeletal wall in Joe’s flat, suggest the barriers between people working in the secret service. Venetian blinds in her flat create yet more bars blocking surveillance, while the presence of Diana Rigg’s daughter in a spy drama subliminally recalls The Avengers (ABC 1961-69). In the same episode a concrete interrogation room is shown in wide shot, symmetrically composed with Catherine and Joe on opposite sides of the frame. A black handrail along the wall behind their heads creates a strong background horizontal and the verticals of its supports divide the room into rectangles. The Turkish baths where Joe finds a Soviet agent similarly subdivide space into rooms within rooms, and the tiling on the walls evokes the grid yet again.

Even leisure spaces feature the cage motif. In episode four, Joe visits a nightclub to meet a KGB contact. The scene starts with a shot of chandeliers (again, glass distorting light). The mise-en-scène is overwhelmingly red and sensual; but the club’s dancing girls are inside giant gilded cages. The camera observes from both inside and outside the cage; it is both trap and protection from the leering men peering through the bars. The imagery of glass, cages, and bars is thus an ambiguous one which recurs in other spaces. The townhouse where Bobby lives with his domineering high society mother Hester (Judy Parfitt) uses signifiers of English Establishment aristocratic heritage, but also functions as a prison. Trying to conceal his homosexuality for career purposes, and to satisfy his mother’s social ambitions, Bobby asks Wendy on a dinner date. The opening shot of the restaurant scene shows the couple reflected in a long thin mirror creating another frame within a frame, a claustrophobic box within which the pair are trapped. After the date ends badly, Bobby is seen climbing the stairs at home; the diamond patterned mesh on the stair railing of his mother’s house creates another cage, hemming him in with social expectation.

In episode five, the plot introduces former British army captain, Denmoor (Craig Conway), planting a bomb in Conservative Party Headquarters. Undercover, Wendy visits Denmoor’s house to gain more information. His front door has a six-paned window and a trellis on the wall forms more grids in the mise-en-scène, signifying that Wendy, on her first field mission, is now active in the Game. Recalling the Fray’s pebbled glass panels, the window in Denmoor’s front door is textured glass which again suggests blurred morality and the impossibility of clear vision. There are more trellises in his back garden, on the walls of the house, and around the tops of the garden walls, visually continuing the grid theme. A skeletal greenhouse resembles an actual cage. The displacement of narrative theme onto the diegesis occupied by individual characters indicates that they are part of the “Game” of Cold War espionage, and visual style offers meta-textual clues to character motivation and narrative.

The Cold War Chronotope and the Pine Forest

I have argued elsewhere that the Cold War in the popular imagination consists of a set of recognizable signifiers comprising a stable cultural identity, which I term the Iron Curtain discursive unconscious:

This semiotic core revolves around an iconographic shorthand of checkpoints, blockhouses, watchtowers, Eastern European cars, pine forests and urban wastelands; liminal boundary sites reflecting the Cold War’s border crossings and moral ambiguities. This place-discourse can be seen in cinema films such as the Le Carré adaptation The Spy Who Came In From The Cold (1965).61

A similar place-discourse is used in television: for example, the Callan episode Heir Apparent (Thames 1969) depicted Eastern Europe through studio interiors of a bierkeller, with filmed exteriors in a pine forest featuring a bunker, fences, guards, spotlights and explosions. The Czechoslovakia ambush in Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (BBC 1979) was shot in Scotland, again utilizing pine forests as a hostile Eastern European periphery. In The Game, flashbacks show Joe with his lover Yulia in an undefined Eastern Europe location represented by pine forests. Despite the romantic quality of the mise-en-scène, the vertical columns of the trees create an outdoor “cage” with the trunks forming bars. This visually foreshadows Joe’s dilemma at the serial’s end. Yulia comes back from the dead and may be a double agent; Joe is “trapped” by the suspicion that he cannot really trust her. This suspicion is signified by further vertical dividers visually separating the pair in the airport scene where this realization happens. Pine forests therefore serve a dual function in such screen dramas; firstly as a setting signifying generalized “Eastern Europe-ness”, but also reinforcing the cage motif and suggesting the way in which characters are physically or metaphorically trapped by their circumstances as players in the game.

Conclusions

The screen texts discussed here reveal a consistent Cold War chronotope comprising Panoptic Brutalist architecture, bureaucratic offices, shabby safe houses and apartments, heritage spaces of Establishment clubs and townhouses, and an Eastern Europe of pine forests and waste ground. These settings are stable signifiers of Cold War narratives meeting audience expectations and generating narratives of suspicion, surveillance and betrayal. Furthermore, the grid, the cage, and the box recur narratively, thematically and stylistically within these spy dramas, turning interiors and exteriors into constraining prison-like sites through breaking space up into “chessboards” and trapping characters within and behind bars, meshes and transparent layers. This article has therefore demonstrated that from its literary origins, the chronotope can be applied now not only to the dramatic and metaphorical meaning of settings and set design in screen media, but can also perhaps be applied to visual style, in the motif of grids, cages and boxes which pervade the Cold War dramas discussed above.

The analysis also demonstrates how these dramas, The Game in particular, function as “recombinant” screen texts. Trisha Dunleavy argues that increasing competition means producers recycle existing successes: “‘recombinant culture’... worked to reduce drama’s conceptual possibilities either to a re-versioning of the tried-and-proven or to ‘recombination’, the latter involving a marriage between previous shows with a ratings pedigree”.62 Oldham notes the long shadow cast by the BBC’s 1979 Tinker Tailor over subsequent spy dramas. As a composite of the earlier screen texts discussed in the first half of this article, The Game is not just nostalgic for the Cold War of the 1970s; it is nostalgic for BBC Cold War thrillers of the 1970s and in particular for one of the jewels in its crown, Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy. As reviewer Vicky Frost commented, “It feels slightly odd for the BBC to be making a 70s period drama about spying, when they have already made the ultimate 70s drama about spying”.63 Oldham argues that there are close parallels between the UK’s intelligence services and its public service broadcasting institutions, specifically the BBC. He argues that both the BBC and the intelligence services function as a social microcosm of the nation.64 Consequently, television dramas around spying, conspiracy and the secret state are really concerned with the broadcasting institutions themselves. If earlier espionage dramas were about the BBC’s loss of certainty in its role as public service broadcaster in the national context of the UK, then a “recombinant” TV drama like The Game (initially broadcast on BBC America)65 is about risk aversion in an increasingly competitive market.

Author Biography

Douglas McNaughton is a Senior Lecturer in Film & Screen Studies at the University of Brighton. His research focus is on sites of screen production as both material and social spaces, and politics of labor within those spaces. His publications include articles on the multi-camera television studio in Journal of British Cinema and Television and Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, and articles and book chapters on camerawork as performance.