Introduction

Automated emails sent from the integrated library system (ILS) account for hundreds (or thousands) of patron contacts each day, but the email templates typically focus on communicating library policy rather than on answering patron questions and concerns. And much like the library website, we do not know anything about the user’s emotional state when they read our emails. They might be in a hurry or worried about getting a fine they cannot afford. Automated emails are a user experience (UX) opportunity that can get overlooked in libraries since they are not a part of the main library website, typically come with serviceable default text, and are often mediated by the library’s systems person or team rather than the UX or website person or team. However, these automated emails are very much a part of the UX of the library.

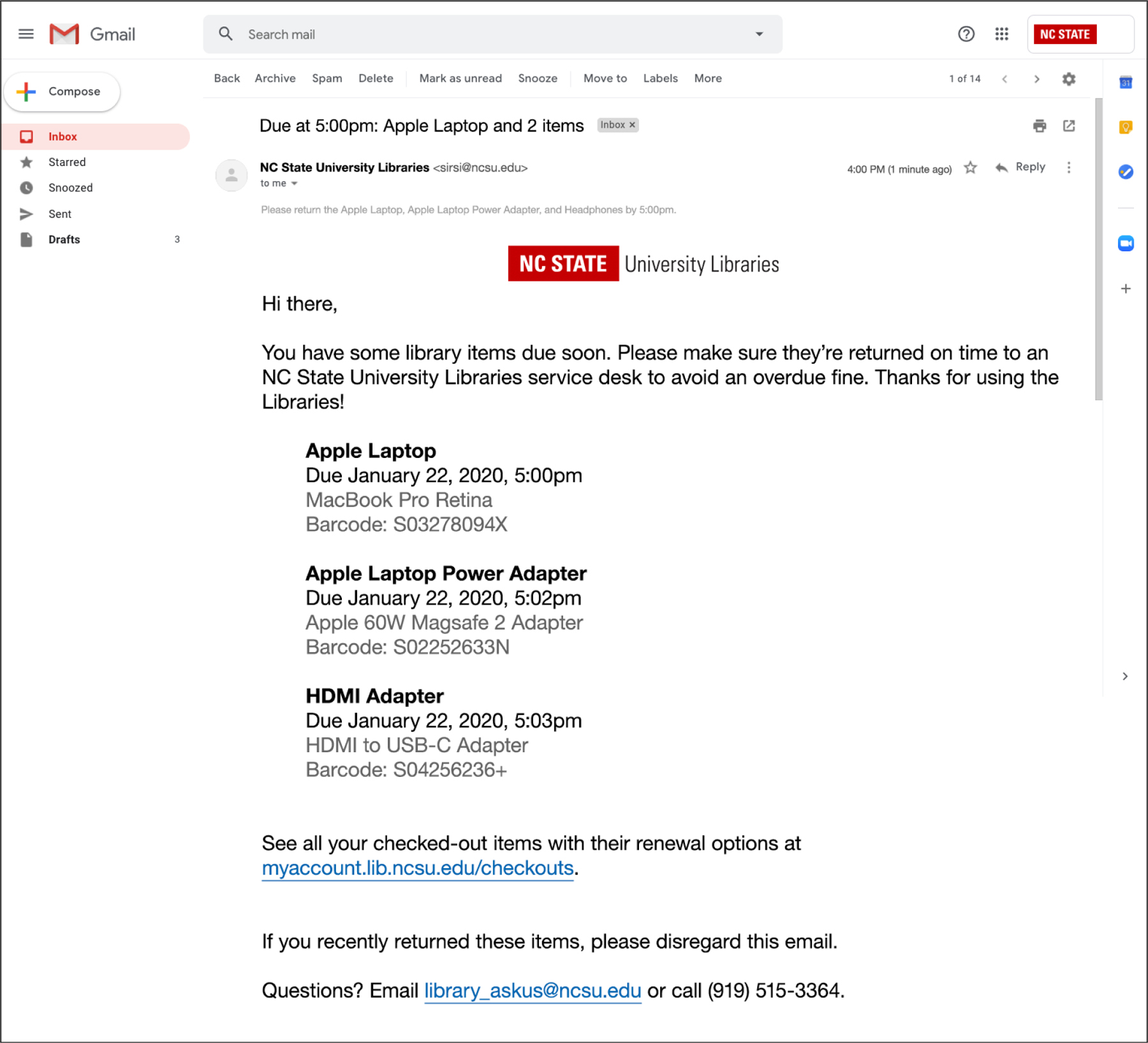

To address the issues with our emails, a small interdepartmental team rewrote all our ILS’ notification templates. (See Appendix A for three examples.) Using our Libraries’ style guide, as well as multiple rounds of user research, we refined formatting, added information users told us would be useful, and made sure the tone of each email was appropriate to its content. Our team had four people. Two public services staff used their experience answering patron questions at the desk and on chat reference to anticipate patron informational needs, and they made sure policy information was accurate. Our ILS administrator knew the constraints and affordances of the system’s email templates and had deep knowledge of circulation rules, policies, and item types. One UX librarian directed the conversations on tone and content formatting and ensured the user stayed at the center of every decision.

In this article, we will describe our approach to creating user-centered library emails, including how we applied our style guide to write for stressed users and other situational personas. We provide an overview of our user research methodology and results for three different user studies and detail how we navigated the ILS to make the necessary changes.

Literature Review

For many users, automated emails sent from the ILS may be a primary way they experience the library’s voice (Davis & Sheffield, 2021). Datig wrote, “some patrons will never speak to a librarian in person; these patrons know their libraries only through content” (2018, p. 63). Email notices are one content distribution channel for the library, along with the website, signage and wayfinding, text messages, and more (Blakiston, 2013; Halvorson & Rach, 2012). As such, they can and should be part of the library’s overall content strategy.

Libraries are using content strategy to create and maintain a positive, consistent experience across library services and communication channels. The goal of content strategy is to create user-centered content and provide structures for its oversight (Blakiston, 2013). As Halvorson defined it, content strategy “plans for the creation, publication, and governance of useful, usable content” (2011, p. 23). According to Blakiston (2013), developing a content strategy is a multi-step process that includes auditing all in-scope content, reviewing processes and standards for content creation, defining your content’s core purpose, and finally, creating workflows to ensure sustainability. While some of these stages are focused on internal workflows and the assignment of responsibilities, the ultimate goal is always to uncover and expunge “poorly written, outdated, and duplicative content” (p. 176).

Content strategy is an “inherently user-centered practice” (McDonald & Burkhardt, 2021, p. 1); that is, it should “focus, first and foremost, on helping users accomplish their goals,” rather than on the information the library wants to communicate (Demsky & Chapman, 2015, p. 27). Automated email notices are an excellent example of content that can benefit from the practice of content strategy because they tend to focus on library policies, risking a missed opportunity to provide useful content to the user.

The literature on content strategy for libraries has emphasized creating structures to address proliferation of website content and distributed authorship and on creating a culture that values writing user-centered content (Blakiston, 2013; Blakiston & Mayden, 2015; Buchanan, 2017; Datig, 2018; Demsky & Chapman, 2015; McDonald & Burkhardt, 2019; Newton & Riggs, 2016). Researchers have also examined other communication channels such as LibGuides (Logan & Spence, 2021) and social media (Datig, 2018; Young, 2016) within a content strategy framework. And while several authors acknowledged that email is an integral way libraries communicate with their users (Blakiston, 2013; Datig, 2018; Godfrey, 2015), it is an understudied aspect of library UX and content strategy. Godfrey wrote that the “principles and methods applied to websites to improve usability and readability can also be applied to all library communications, including emails … newsletters, and signage” (2015, para. 12).

Across channels, decentralized authorship is a core challenge to creating consistent, user-centered content. McDonald and Burkhardt (2019) observed that “[i]n an environment with distributed authorship lacking a strong and consistent editorial culture, an organization’s ‘voice’ can quickly deteriorate” (p. 13). An organization’s voice is its “personality” (McDonald & Burkhardt, 2019, p. 13). Young (2016) wrote that voice is “a stable organizational identity” created through a “combined expression of content and values” (p. 12). Content strategy must include voice and tone in order to maintain a strong, consistent institutional persona that communicates the values of the organization. Logan and Spence (2021) conducted a survey on content strategy practices for LibGuides and found that “respondents more frequently included the concrete considerations such as topics … and target audience … than the more abstract considerations such as voice and tone” (pp. 4–5). Buchanan (2017) suggested one way of maintaining an editorial culture focused on voice and tone was to create a style guide, though cautioned that “encouraging compliance is critical because writing for usability isn’t always intuitive” (para. 5).

Another approach to creating content with an user-centered voice and tone is to create user personas, which authors can use as imagined audiences. Personas can create “a common, consistent vocabulary for user-centered design” (Sundt & Davis, 2017, para. 2), though the process of creating personas must be attentive to the potential for flattening “important differences” (Sundt & Davis, 2017, para. 12) or creating stereotypical representations of users (Newton & Riggs, 2016, p. 8).

Library UX practitioners are grappling with how to make the library’s voice consistent across channels, while writing in a tone appropriate to the particular channel at hand. Writing in an appropriate tone and voice is more than just good branding—it’s the foundation of creating user-centered content. An organization should consider both voice and tone when writing (Mailchimp, n.d.; Moran, 2016; Young, 2016). While voice is stable, tone is (or should be) “dictated by various contexts in which your users will experience your content” (Young, 2016, p. 13). The influential Mailchimp style guide noted that “[y]ou have the same voice all the time, but your tone changes” (n.d., “Voice and Tone” section, para. 2). We do not know the user’s emotional state at the time they’re reading our website, signs, or emails. In the case of automated emails in particular, we know that some of the notices we’re sending, such as those about overdue fines or recalls, won’t improve someone’s day. We do not want to add to the burden of that news by using an inappropriate or unhelpful tone.

Tone is “the way we tell our users how we feel about our message, and it will influence how they’ll feel about our message, too” (Moran, 2016, para. 3). Moran (2016) offered four dimensions of tone: funny vs. serious, formal vs. casual, respectful vs. irreverent, and enthusiastic vs. matter-of-fact. The tone of a given piece of communication will fall along the spectrum of each of these dimensions; for example, our updated hold pickup notices moved closer to the enthusiastic side of the spectrum, while still maintaining a respectful tone.

Context should always determine the tone used for any given piece of content, and tone should be part of any content planning (Logan & Spence, 2021; Moran, 2016; Young, 2016). Young (2016) explained that “receiving an overdue notice may generate feelings of distress for the user, while reading a newsletter may be a more neutral or positive experience” (pp. 13–14). Thus, you may choose to take a more casual or even irreverent approach in a newsletter, while you would not want to do so for an overdue notice. The Mailchimp style guide teaches their content writers that “tone … changes depending on the emotional state of the person you’re addressing,” and writers must account for the “reader’s state of mind” with each piece of content (n.d., “Voice and Tone” section, paras. 3 and 9). A mature content strategy accounts for tone in the planning of all content, tailoring it to the communication channel and content of the message, which helps to maintain a consistent library voice and experience for the user (Halvorson, 2012; McDonald & Burkhardt, 2019; Moran, 2016; Young, 2016).

Our project to rewrite automated library emails took into account the user’s emotional state by planning tone around the needs of a stressed and anxious user. Many libraries, including our own institution, are now working within the paradigm that “[t]he prevailing school of thought is that student wellness is a campus-wide responsibility” (Rose et al., 2015, p. 4). While conversations around student wellness and the library often center on services such as extended hours, additional academic support services, and stress-alleviating activities (Rose et al., 2015), we wanted to bring a student-wellness focus to our automated email content.

We sought to write emails in a tone that acknowledged significant levels of student stress, anxiety, and depression (Haskett & Dorris, n.d.). Additionally, by creating user-centered content with clear language as free of jargon as possible, we sought to reduce the “expectations of tacit knowledge” and the “implicit vocabulary, procedures, and culture” of college that first-generation and international students experience when encountering university services (Couture et al., 2021, p. 127). Principles of UX and user-centered content strategy can apply to all content channels and benefit all users. By “avoiding library jargon, using personal and friendly language, and reducing unnecessary text, library communication becomes usable, useful, and clear” (Godfrey, 2015, para. 12).

User Research

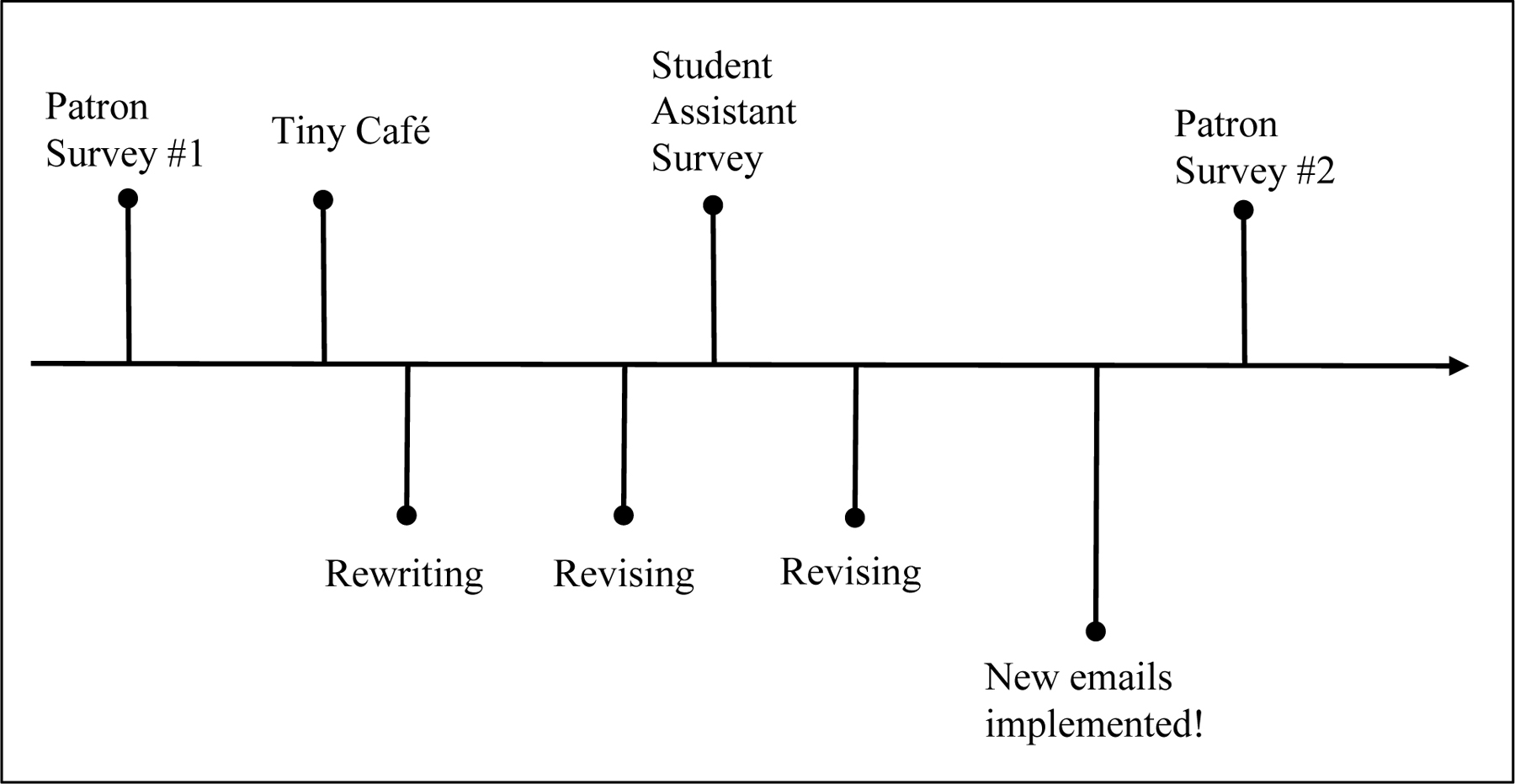

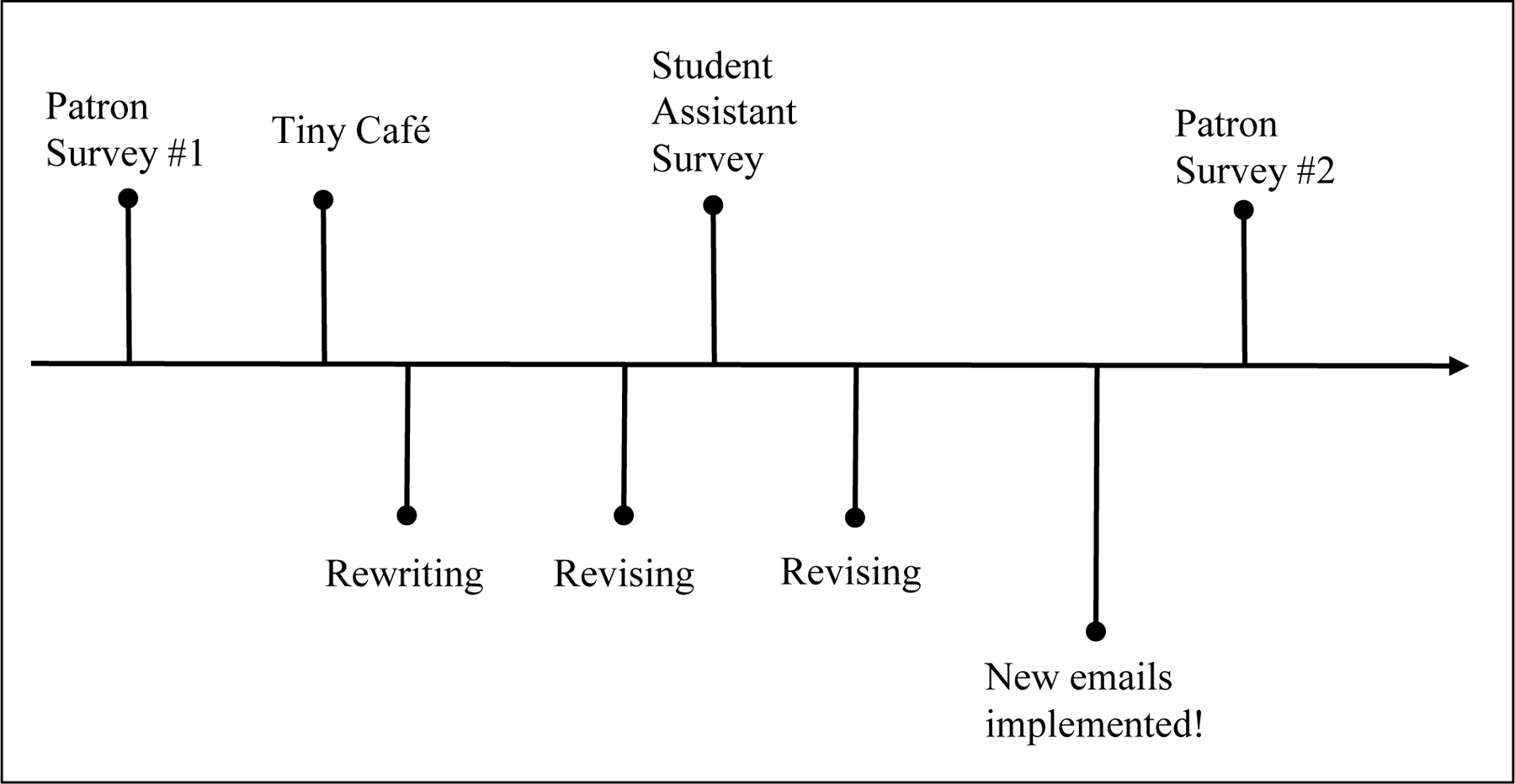

Using the Libraries’ content strategy as a guide, we knew that our email templates needed to be improved in content, tone, and voice. To identify the primary pain points for users reading our emails, we conducted user research throughout the process of revising our email templates. This included a patron survey evaluating the existing emails, a Tiny Café for testing initial prototypes, a student assistant survey evaluating the second prototypes, and another patron survey, as shown in Figure 1, below. We’ll return to this figure when we discuss how we responded to user research through the rewriting and revision process.

Patron Survey #1: Evaluating Then-Current Emails

We designed our first survey to assess how patrons perceived our then-current ILS emails.

Methods

In fall 2019, we surveyed users about the Libraries’ email communications from our ILS, SirsiDynix Symphony (Sirsi), by inserting links to Qualtrics surveys into six of our eighteen automated email templates. The text we used was “How can we improve this email? Please, let us know by filling out this short survey. You will have a chance to win a portable USB power bank! <URL>” Our goals were to identify whether our current email notices were timely, clear, and useful for patrons and to gather feedback on how we could improve our emails.

The surveys included multiple-choice questions like “How clear was this email to you?” and “How useful was this email to you?” as well as open-ended questions like “How could we improve this email?” Those questions were the same across all six surveys, but we also included more context-specific questions based on the specific email template the survey was linked from. For example, the survey linked from the expired holds email asked, “Do you feel that you received adequate notice that your requested item would be removed from the hold shelf?” See a sample survey in Appendix B.

Results

We kept the surveys open for nine weeks, and when we closed them we had fifty-six total responses. Overall, the respondents found our emails useful and clear.

We focused much of our analysis on responses to the short-term courtesy notice because it gets sent more than any other email and because we had anecdotal reports that the timing of the email was confusing. For context, we send around 800 of these notices per day, mainly for tech checked out for 8 hours, but also for textbooks checked out for 2 hours. Thirty-two of our responses were from this survey.

In this survey’s results, 72 percent said the short-term courtesy notice was “Very clear” and 28 percent “Somewhat clear.” Eighty-one percent described the email as “Very useful” or “Somewhat useful, and I’m glad I received it.” Nineteen percent of responses described an email as “Somewhat useful, but I could do without it” or “Not useful at all.”

The answers to the free-text question “How could we improve this email?” offered the most constructive feedback. Eight respondents indicated that the email was fine, and two had no comment. Four wanted more details about policy. One wanted more details about the item in the email. Ten had suggestions related to the timing or frequency of the email. Most significantly, twenty-nine offered suggestions for better formatting, such as changing 24-hour time to 12-hour time in due dates.

This survey data was useful as we started to think about updating our emails. But it had a major limitation: all the respondents were people who opened our emails and read them closely enough to see the survey link. In that way, they were not necessarily representative of all patrons.

Tiny Café: Testing First Prototypes

Based on the feedback from Patron Survey #1, we drafted a new prototype of our courtesy email for short-term loans. We chose this loan type in part because it was one we had previously identified as needing improvements and in part because the Patron Survey #1 responses indicated that it was the least useful. We chose to use a Tiny Café (pop-up table) format to get user feedback on these prototypes because we could have a quick data-collection period and more in-depth information from patrons.

Methods

Tiny Café is a user research method borrowed from the libraries of University of Arizona (Tiny Café, 2019), University of Houston (Pshock, 2017), and Penn State University (Chao, 2019). The general concept is that rather than recruiting participants ahead of time, we set up a table with coffee and snacks by the library entrance with a sign that says, “Free coffee and snacks for 10 minutes of your time,” and wait for patrons to approach. Previous to the COVID-19 pandemic, we did Tiny Cafés regularly at NC State and have a checklist for the logistics of setting one up, which includes scheduling a physical table and sign and arranging for the food and drink (Tiny Café, n.d.).

For this particular Tiny Café set-up, we had three library staff members working: the greeter, the interviewer, and the note-taker. The greeter talked with interested patrons about what we were doing and what their participation would involve. After a patron opted in, the bulk of their time was spent with the interviewer and note-taker. The interviewer’s script started with an orientation to the activities (see Appendix C).

Most of the email template rewriting team was involved in planning this user research and drafting the script. Among other things, we emphasized that we were testing our prototypes, not the participant, and that our feelings wouldn’t be hurt by their honest opinions. The interviewer then gave the participant a hypothetical scenario: “Let’s say you checked out a charger and some other things this morning from Ask Us. Now it’s 4 p.m. and you get this email in your inbox.” Then we showed the participant our paper prototype of the email subject and snippet (i.e., a screenshot of how the message looked from the email inbox) and asked questions about their understanding of and expectations about the content of the email.

Meanwhile, the notetaker took notes in a Google form, set up to have a free text box for every question in the script. The interviewer then gave the participant a paper prototype of the full email and asked more questions about the clarity and usefulness. We also asked what the participant would do if they couldn’t return the item on time, as well as about their preferences regarding email timing and content. After the participant completed the interview, they helped themselves to the refreshments.

Results

We did two iterations of this Tiny Café, one at each of NC State’s main libraries. In total, we had thirty-five participants whom we interviewed about email prototypes as described above. Overall, we received positive feedback and learned more about user expectations for library emails.

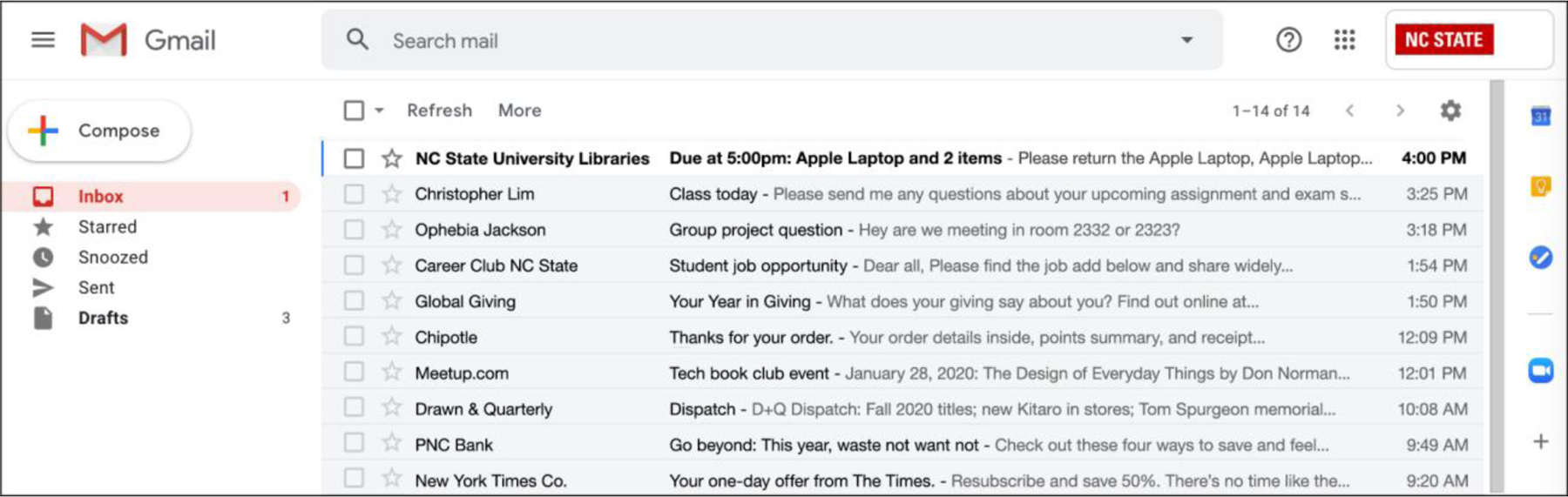

One common theme in our findings was around policies. Many participants pointed out that they wished more information were communicated in automated due date emails, including late fine policies and information about returning items to different library locations. The participants also found our subject line, “Due at 5:00pm: Apple laptop and 2 items” informative and actionable. (We later learned that dynamic subject lines like this were not possible with our ILS.) Ten out of sixteen participants (63 percent) said they would not need to open an email with that subject line to understand the thrust of the email and act upon it.

Student Assistant Survey: Testing Second Prototypes

After we drafted new versions of all our Sirsi emails, we wanted to get some feedback from people outside of our small team, so we sent a survey to the student assistants who work at the Ask Us (reference and circulation) desks at our main libraries. They have a unique perspective since they are students themselves and have many direct interactions with patrons. We paid the nineteen participants for 30 minutes of work at their regular rate.

Methods

We used internal mailing lists to invite all our Ask Us student employees to take a 30-minute Google Forms survey. The survey focused on new drafts of three email templates: a courtesy email for a short-term loan, an overdue notice, and a billing notice. For each of the three templates, the respondent would read an example email and answer a series of multiple-choice and short-answer questions.

Results

The respondents found all three emails to be clear and the tone to be respectful, though they shared our desire for better formatting. Their answers to the free-text questions “How would you improve this email?” and “Thinking about your work at Ask Us, can you foresee any confusion that a patron might have if they received this email?” were particularly helpful. For example, they suggested adding language to the billing email to clarify that patrons can still return items marked “lost” and get the replacement fees removed.

Patron Survey #2: Evaluating New Emails

After our new email templates had been implemented for a year and had undergone a second round of minor changes, we wanted to get users’ impressions of them.

Methods

We emailed 257 patrons in our campus-supplied survey pool with an invitation to complete a 10- to 20-minute survey in exchange for a chance to win a $25 meal delivery. The survey started with a hypothetical scenario of the respondent checking out a laptop and charger. They were then shown the courtesy, overdue, and billing emails for those items, similar to our survey for student assistants. For each email, the survey asked about clarity, the emotional impact of the email, where the most important info was located, how they might improve the email, and which parts might confuse other students. The survey also included questions at the end about the new Q&A sections we added to the emails and about their overall impressions of the library’s emails. (See Appendix D for this survey.)

Results

We received twenty-two survey responses. The average clarity rating, combining the ratings from all three templates, was 4.5 out of 5. An average of 89.4 percent of the respondents felt “informed” after reading the email, and an average of 51 percent reported finding the most relevant information at the top of the emails.

Respondents also offered suggestions for improvements. Formatting was again a common theme, particularly related to making the due dates more prominent. There were a few suggestions for adding more links or interactivity to the email (e.g., a renew button, or the ability to add an entry to Google Calendar), but most of the suggestions regarding interactivity or improved formatting are not feasible to implement due to system limitations. We are keeping them in mind for potential future improvements to our email templates. For the billing email, some respondents wanted more detailed information about how to return the item and/or pay the fine. Several participants suggested changing the subject to convey more urgency so that patrons would be less likely to overlook it.

The question about potential points of confusion had varied responses, but the one that came up repeatedly was for the overdue email. Respondents wanted to know more about late fees and policies, and they wondered if fees had already started accruing or when they would start.

When we asked about their overall thoughts on the Q&A sections at the bottom of the emails, six respondents indicated that they were helpful or informative. Four respondents thought they might be ignored or overlooked. A few respondents thought they were too wordy, and we also got several suggestions to make them more readable by tweaking the formatting.

Most Frequent Findings

Across all our user research activities, there were several consistent findings about what our users wanted:

more detailed information about fines and other relevant policies

specific, informative subject lines

better formatting

language conveying the appropriate amount of urgency

Content Considerations

With our initial user research findings in mind, we evaluated and revised the automated emails our ILS, Sirsi, sends. We adhered to practices from our web style guide and the UX industry about content strategy for written communication. We prioritized writing for stress cases, using an appropriate tone for each email, and structuring the email for maximum impact in a user’s inbox. With this guidance, we systematically drafted and reviewed our email templates.

Creating and Using a Style Guide

Organizations that have multiple people writing content can employ a style guide, either a popular one that already exists, such as the Chicago Manual of Style, or one that they create internally (Metts & Welfle, 2020). Style guides often provide direction about capitalization, punctuation, and words to use or avoid. Our library system already had a branding style guide, which included guidance about how to refer to our organization—“the NC State University Libraries,” not “the NCSU Libraries.”

However, the User Experience Department identified a need for a web style guide—one that addressed not just word choice, but ways in which writing for the web is different from academic writing. The Department wrote the guide for our colleagues with editing permissions on our website. We took inspiration from the Mailchimp style guide (Mailchimp, n.d.), which included sections about voice, tone, and content organization. In spring 2020, the User Experience Department published an internal web style guide (Boyer et al., 2020), which included these tips for writing for the web:

Voice.

The Libraries’ voice is our overall personality: business casual. We are professional but not stuffy.

Keep it brief.

Write in short paragraphs with lots of headings. Use bulleted lists where it makes sense. …

Use plain language.

The goal of our website is to help users get what they need quickly. Simple language lowers the user’s cognitive load. Plus, plain language is easier to understand for users whose first language is not English. …

Use positive language.

If you’re describing something a user can’t do, try to focus on what the user can do. …

Skew informal.

Web writing is more intimate and less formal than academic writing. We’re not saying you have to communicate only with emoji, just that a more casual tone makes web content more readable and welcoming. (paras. 3–7)

While the style guide was meant for web content published on our Drupal website, we applied the principles to our automated emails, too.

Writing for Stressed Users

A common writing tip for everything from college essays to advertising copy is to consider the audience. For whom is it written? On some campuses, when considering web content or emails for a university population, it can be tempting to imagine a “typical” user. Indeed, creating a persona is a common practice in UX. A persona is a “fictional, yet realistic, description of a typical or target user of the product … an archetype instead of an actual living human” (Harley, 2015). Personas are often described with character traits, background stories, and experience levels to generate empathy and a user-centered perspective while creating a product or content. In an academic library context, some projects may benefit from the use of personas (Hixson & Parrot, 2021). However, these personas often do not include disposition—they do not consider the mood or specific situation the user is in when encountering the product. Users can read emails anywhere at any time, so it’s important to consider the range of situations a user may be in when they open the email.

Instead of inventing user personas, we suggest creating situational personas when considering communication services. For instance, in the case of an overdue email template, one situational persona may be the user whose overdue book is currently in the bag they’re carrying. This user is on campus and can easily drop it off at the library that day. When they read the overdue email, it’s not a significant stressor. By contrast, a more extreme situational persona may be the user who is traveling abroad for a funeral service. This user’s stressful scenario is unrelated to the overdue email, but receiving that notice may serve to exacerbate their level of stress: this user might not know where the book is, when they’ll be able to return it, or how much of a late fine they will receive when they do. These users aren’t described by their hobbies, behaviors, or life stories. Instead, what matters is what situation they are in when they receive the automated email. Our goal was to consider the more extreme situational personas, not what we would consider “typical” ones, while rewriting our email templates.

The concept of “stress cases” from Design for Real Life informed our thinking about the audience for our emails and their situational personas. Rather than consider a typical user when writing or designing web content, consider what stressful situations they may be in, and design the content to be usable in that situation. “If someone comes to a site or an app in a moment of crisis, we bet they have a genuine need to be there—and that is the exact moment we don’t want to let them down” (E. A. Meyer & Wachter-Boettcher, 2016, p. 46). As we evaluated and rewrote our email templates, we considered how a stressed user or a user in crisis would react to the email. We repeatedly asked ourselves questions beginning with “What about a user who…” or “What if the user…?” We aimed to find a way to add the least amount of stress to our users’ already stressful lives, while still suggesting that they take action in response to some of these email templates.

One of our strategies was to include a short Q&A section addressing topics that our Ask Us student employees identified as common questions and points of confusion. For users who were engaged or worried enough by the first half of the email, we endeavored to answer questions that they probably had, such as whether they could renew their materials and how to check their account to view any fines. The objective of writing for stress cases was not to suppress information, such as the fact that the user has been billed for a lost item, but rather to explain the situation clearly, provide a next step, and do so in a way that communicated the lowest appropriate level of urgency.

This project started in March 2020. We had been discussing how to view our public-facing work through the lens of stress cases, which became even more important as the COVID-19 pandemic began. Every use and user could be considered a stress case. Logistically, the pandemic necessitated including information about policy changes in some email templates, such as a note about library branches that were temporarily not accepting returned items. We strove to consider compassion, calmness, and appropriate tone as we rewrote the emails.

Varying Tone

Using our style guide, we aimed for a consistent voice in our emails that matched the voice in the rest of our web content. However, with stress cases in mind, we varied the tone of each email depending on its contents. We were cognizant that the user might be reading the email in the middle of another task, and that communication is contextual. As Metts & Welfle (2020) noted:

[T]hings change depending on the following information: where users are in the journey; how experienced they are in using the interface; what their intentions are; [and] what their mood is: how receptive they are to what you are guiding them to do. (122)

We purposefully imagined users opening the email in a variety of scenarios, such as on their phone while riding the bus home in between reading other emails. For some emails, a happy or friendly tone would be appropriate in these scenarios, depending on the objective of the communication; for others, a more serious or authoritative tone would be more suitable.

The existing (old) email templates had last been edited extensively in 2012. They used a staid tone. As an example, here is the old template for emails that alerted users that a hold they had requested was available:

Subject: Requested library item available for pickup

[Library name]

Dear library user,

The following item is available for you at the library listed above. Please come by and pick it up.

[item listing, account link, and library contact information]

This email felt stilted and overly formal, and the subject line sounded robotic. We felt that this was an email that could have a friendlier, more human, even more celebratory tone. We were inspired by Grand Valley State University Libraries’ email template, which one staff member there noted gave her a “spark of joy” (K. Meyer, 2019). Our revision:

Subject: Great news! Your library item is available for pickup

[Library name]

Hello,

Great news! The following item(s) that you requested are now available for you to pick up at the library shown above. We’ll hold them for you at the service desk for 10 days.

[item listing, account link, and library contact information]

This example demonstrates three tone-related decisions. First, we replaced the salutation “Dear library user” with the more conversational “Hello.” Not only did that sound friendlier, but the linguist Gretchen McCulloch pointed out that some younger university students found that the word “dear” was “uncomfortably intimate, like calling your professor your darling” (McCulloch, 2021). The generic “Hello” was an appropriate salutation for all our emails, including ones about billing. Second, as part of the friendlier, more conversational tone for this template and some others, we used contractions (“we’ll”), something that the old templates avoided. Third, we allowed ourselves to use more enthusiastic punctuation. Overall, the old templates had zero exclamation points among them; our new templates had twelve total. With these three changes to the hold pickup notice, along with additional information about how long the item would be held for the user, we made this template more welcoming and informative.

For other templates, of course, we took different approaches to tone:

Overdue notices: informative, though not dire (“You have overdue items from the Libraries. Please return them soon.”)

Billing notices: serious (“Since we did not receive the following item(s) back on time, you have been fined for them.”)

Hold canceled notice: apologetic and sympathetic (“We’re sorry, we can’t fulfill a request you placed 6 months ago.”)

By varying the tone of each email notice depending on its main objective, we were able to reduce confusion and communicate the appropriate level of urgency.

Structuring Content

As much as possible, we front-loaded important information in our email templates. We followed the inverted pyramid model, in which the most important thing to know comes first, followed by other information in order of most to least importance (Nielsen, 1996). This structure can be good practice for web content, and it is doubly important for emails.

We aimed to pack the necessary information into a concise, readable subject line. Since our ILS could only support a static subject line for each template, we could not accommodate a request that came up in our user research for dynamically changing subjects, such as “Due in 1 day: Apple MacBook.” Still, we did our best to summarize the important information for each template in the subject, for example: “Library items due in 1 day.”

Furthermore, we considered how the email would look to the user in their inbox, particularly on mobile. In a typical inbox, the user would see the subject as well as a snippet or preview of the email itself. This snippet would come from the top of the email’s body, so we aimed to make the first fifteen words or so of each template as informative as we could. This necessitated changing some settings in our ILS to remove cruft that appeared at the start of the email, which we’ll cover in the following section. As the Mailchimp style guide noted, the snippet can “[p]rovide the info readers need when they’re deciding if they should open” the email (n.d.). That style guide assumed the aim is for users to open emails as much as possible to achieve a high “open rate.” But our notices are not the same as a marketing email or newsletter, so we had an opposite reaction to the idea of boosting our open rate. A successful automated email from the library might be one that the user doesn’t even have to open: the user is reminded to take an action based on the subject and snippet alone.

Generally, our templates followed this content structure:

The most important thing to know, such as that items are overdue (2–3 sentences)

Item list

Q&A section, such as “Can these items be renewed?” (2–4 questions and answers)

Email and phone number for the Libraries

The Rewriting Process

We began rewriting our email templates in the spring of 2020. We split the process into three parts: recommendations, rewriting, and reviewing. Figure 2 shows how our rewriting process was intertwined with our user research.

Recommendations

Based on our initial user research—Patron Survey #1 and the Tiny Café—we drew up a document that listed recommendations for the new email templates. Essentially, these became a requirements list. For example, we noted that we should “add information about where the item can be returned, even if it can be returned to any library.” This document of recommendations also included best practices from UX literature and writing tips from our internal style guide.

Rewriting

We set up a Google Document with all eighteen of the existing (old) templates. We split those templates among three of us, and each of us revised our assigned templates in the document, referring often to our recommendations list. We did this writing work asynchronously and made heavy use of the commenting feature.

Reviewing and Revising

After reviewing each other’s drafts, we met to discuss questions about the timing of the automated emails and other details, such as whether the subject line should say “items” or “item(s).” We sought to use consistent wording and formatting, so different phrases that meant the same thing in different drafts were normalized into consistent wording. At this point, we considered the tone and structure of every template, taking a user-centered approach as much as possible within the limitations of our ILS.

Once we had come to consensus on those revisions, we conducted another round of user research (Student Assistant Survey) and incorporated some changes based on that feedback. Finally, we sent the template drafts to the Web Content Team, which provides ongoing, strategic guidance and clarity about web content across the Libraries. We then applied their suggested revisions, including changing our original salutation of “Hi there” to “Hello.” It was helpful to get feedback from library staff members who were not part of the project. With these changes, we were ready to implement our new email templates.

ILS Limitations

Notices to library users remain an important business function of any ILS. Since migrating to Sirsi in 2003, NC State University Libraries has only sent notices to users in the form of text-based email. Historically, the Sirsi templates were designed to be dual purpose and consisted of a single business-letter template which could be used to send text-based print and electronic notices to users in one scheduled job. This text-based format is still intact today for system-generated notices, and we continue to use this format in our email communications.

Working within the constraints of system-derived templates and notice jobs means there are certain hard-coded elements and functionalities to circumnavigate. In revising our notices, we found that limitations of the notice template formatting and timing of email notifications presented the biggest challenges in revising and drafting our new email templates.

Formatting

As with any ILS, system-defined elements often constrain customization. The current text-based email notice templates are composed of a mixture of customizable text blocks and system-controlled fields. The system defines the order of the notice elements:

Heading message

Item list

Closing message

The heading and closing message text are the customizable text blocks that present the user with the reason for the notice as well as any general information that would be helpful to the user, such as hours and contact information. The item list provides information on the items, such as title, call number, date, fine amount, etc. However, the item format and elements available for output are set by the system with limited options for customization.

As part of our survey, respondents provided suggestions to improve the overall UX, such as listing certain information in bold and changes to time/date formatting for due dates and hold pickup times. Our respondents likely expected that these formatting updates would be feasible, considering the rich formatting of other automated emails that they receive, such as newsletters and order confirmations. But we couldn’t implement many of these suggestions due the nature of text-based email and system-controlled formatting. Given the feedback from our user research, providing these emails in rich text formatting is an option we will consider for future implementation.

Other challenges involved the display of hard-coded information that could not be removed from notice output. As stated, the snippet is an important part of the overall email communication that provides a snapshot view of the purpose of the email. Certain elements appear in a fixed position by default, such as the day/date of the notice, which was always at the top of the email. When elements that display at the top of the email cannot be removed or repositioned, they can cut into the snippet and limit the user’s ability to quickly skim information.

Finally, inconsistencies in the display options among the various notice template elements could result in an incongruous experience for users. For example, some notice templates would not allow us to remove the user’s address from the notice, while other templates gave the option to hide this information. Likewise, certain notice templates did not have an option to provide closing text, forcing information into the heading text that would be more appropriate in the closing text, such as general library information.

While we found that these issues did not negatively impact the overall interaction when the notice was positive, having to work within the constraints of the system forced us to make decisions on which information to prioritize and where to present that information.

Timing

The timing of the notice is just as important as its content, both for conveying context and driving urgency. For the information to be effective, it has to come to the user in time for them to take action, if required. To fully understand the implications of notice timing and how it relates to notice text, we looked at our loan policies—specifically, our short-term loan programs, such as tech items (eight-hour loan) and reserve textbook material (two-hour loan). Table 1 shows our notice schedule for various items.

Snapshot of NC State University Libraries loan periods and notice schedule.

| Item type | Fine rate | When the courtesy notice is sent | When the overdue notice is sent | When the item is assumed lost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Books and media (non-reserve) | None | 3 days before due | 1, 10, and 30 days past due | 61 days |

| Reserve material, 2-hour loan | $1 per hour | Same day | 1 day past due | 2 days |

| Tech item, 8-hour loan, high value (like a laptop) | $1 per hour | Same day | 1 day past due | 2 days |

| Tech item, 8-hour loan, low value (like a charger) | None | Same day | 1 day past due | 2 days |

| Tech item, 3-day loan, high value | $3 per day | 1 day before due | 1 and 2 days past due | 3 days |

| Tech item, 2-week loan | $1 per day | 1 day before due | 1, 3, and 7 days past due | 8 days |

For example, after a user checks out a tech item with an eight-hour loan period, they’ll receive one courtesy notice reminding them of the due date and time on the day the item is due, within an hour of checkout. If it is not returned, they will receive one overdue notice the following day—one day past the due date. After two days unreturned, the item will be “assumed lost,” and the user will be billed for the replacement cost and a processing fee.

For the most part, we were satisfied with the timing rules that were already in place, with one notable exception. Ideally, we would have liked to provide users with a courtesy notice for short-term loans closer to the date/time the charge is due. Providing an alert that the item is coming due within an expected amount of time would give the user the opportunity to take measures to return the item on time and avoid fines and ensure the material is available for another user.

However, the option to send a notice within hours or even minutes before an item is due is not available in the Sirsi reporting system that generates notices. The only criteria available for the “date due” selection for the notice job is “days,” “weeks,” or “months” before due. Additionally, the notices are sent via scheduled jobs that run every hour. Therefore, the criteria for the notice job had to be set to select charges that are due “today” where a previous notice had not been sent. This results in users receiving a courtesy notice within one hour of charging the item and shortly into the eight-hour loan, anecdotally leading to confusion or annoyance. For example, a user who checked out a laptop at 10 a.m. used to get a “due soon” notice at 11 a.m., 7 hours before their item was due.

When we revised this template, we turned it into a confirmation instead of a warning:

Old subject: Library item(s) due very soon

New subject: Thanks for checking out these items. Here’s when they’re due.

In rethinking this template, we were inspired by other automated emails that users might be familiar with: the order confirmation or emailed receipt. Moreover, we decreased the sense of urgency (“due very soon”), instead taking a friendlier, more conversational tone (“here’s when they’re due”). While the constraints of the system required compromise between notice text and timing, survey feedback was positive, with 89.4 percent of the surveyed participants stating they feel informed by the messaging. Additionally, the new templates received a rating of 4.5 in clarity on a scale from 1 (very unclear) to 5 (very clear).

Conclusion

We like our current emails, but we know they shouldn’t last forever. One thing we learned from this process is that it’s a good idea to periodically review our email templates. Aside from policy updates, there could be an updated style guide or new functionalities available in our ILS. We would also want to reassess our knowledge and assumptions about our patrons’ lives and communication habits; perhaps situational personas will emerge that we didn’t consider last time around. We plan to do a holistic review about every five years.

All in all, this project was a successful collaboration. We benefited from having core team members from four different departments and from the feedback we received from others in the organization. Through iterative user research, thoughtful content evaluation, and creative application of our ILS’ tools, we brought our library’s voice to our patron’s inboxes.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Margaret Peak for invaluable help with managing our research data and user research support; Brittany Johnson, Pete Schreiner, Cole Hudson, and Krystal Kimmel for hands-on help with our user research; the Web Content Team and Ask Us student employees for their constructive feedback about our template prototypes; and members of the Communications Infrastructure Project Team for input and support of this project.

Appendix A: “Before” and “After” Emails

General Overdue Notice

Before

Subject: Library item(s) overdue

Thursday, February 27, 2020

JANE DOE

123 EXAMPLE ST

RALEIGH, NC

27695

555–555-5555

JANEDOE@NCSU.EDU

Dear library user,

The following item(s) are overdue. Please renew or return them immediately.

1 call number:TS1109 .C6 slide1+37 ID:S00400933J

Coated paper defects.

Canadian Pulp and Paper Association. Technical Section. Coating

Committee.

due:2/26/2020,23:59

To renew, go to: https://myaccount.lib.ncsu.edu

To return, drop them off at any of the NC State University Libraries.

Thank you for taking care of this matter promptly.

NC State University Libraries Ask Us

(919) 515–3364 | library_askus@ncsu.edu

After

Subject: You have overdue items from the Libraries. Please return them soon.

May 2, 2021

Hello,

You checked out some item(s) from the NC State University Libraries, and they are past their due date. Please return them to any Libraries location, or renew if needed. Thanks for using the Libraries!

1 call number:TS1109 .C6 slide1+37 ID:S00400933J

Coated paper defects.

Canadian Pulp and Paper Association. Technical Section. Coating

Committee.

due:5/1/2021,23:59

——

What if I still need these items? Can they be renewed?

View all your checked-out items and any available options to renew them at myaccount.lib.ncsu.edu/checkouts. If you don’t have any renewals left, you may be able to check the item out again by contacting Ask Us at lib.ncsu.edu/askus or coming to a service desk.

Where should I return them?

You may return your items to any NC State University Libraries service desk or bookdrop.

What are the Libraries’ hours?

View library hours at lib.ncsu.edu/hours.

How do late fees work at the Libraries?

View our late fees at lib.ncsu.edu/borrow/fines.

Some items are considered “lost” if they’re late by a certain number of days. View our lost item fines and policies at lib.ncsu.edu/borrow/lost.

——

If you returned these items more than 24 hours ago or if you have other questions, please contact us:

Email library_askus@ncsu.edu.

Call (919) 515–3364.

Hold Pickup Notice

Before

Subject: Requested library item available for pickup

Monday, June 24, 2021

D.H. Hill Jr. Library

2205 Hillsborough Street

Box 7111

Raleigh, NC

27695–7111

JANE DOE

123 EXAMPLE ST

RALEIGH, NC

27695

555–555-5555

JANEDOE@NCSU.EDU

Dear library user,

The following item is available for you at the library listed above. Please come by and pick it up.

To view your library account, go to https://myaccount.lib.ncsu.edu

NC State University Libraries Ask Us

(919) 515–3364 | library_askus@ncsu.edu

1 How to read a North Carolina beach : bubble holes, barking sands, and

rippled runnels / Orrin H. Pilkey, Tracy Monegan Rice, William J. Neal.

Pilkey, Orrin H., 1934-

call number:GB459.4 .P56 2004 copy:1

Pickup by:7/4/2021

After

Subject: Great news! Your library item is available for pickup

Monday, September 27, 2021

James B. Hunt Library

JANE DOE

123 EXAMPLE ST

RALEIGH, NC

27695

555–555-5555

JANEDOE@NCSU.EDU

Hello,

Great news! The following item(s) that you requested are now available for you to pick up at the library shown above. We’ll hold them for you at the service desk for 10 days.

Please note that service desk hours vary at each library. You can view library hours at lib.ncsu.edu/hours and see your Libraries account at myaccount.lib.ncsu.edu.

If you have any questions, please contact us at library_askus@ncsu.edu or call (919) 515–3364. Thank you for using the Libraries!

__

1 How to read a North Carolina beach : bubble holes, barking sands, and

rippled runnels / Orrin H. Pilkey, Tracy Monegan Rice, William J. Neal.

Pilkey, Orrin H., 1934-

call number:GB459.4 .P56 2004 copy:1

Pickup by:10/7/2021

Short-Term Courtesy Notice

Before

Subject: Library item(s) due very soon

Friday, August 2, 2019

James B. Hunt Library

1070 Partners Way

Raleigh, NC 27606

JANE DOE

123 EXAMPLE ST

RALEIGH, NC

27695

555–555-5555

JANEDOE@NCSU.EDU

Dear library user,

You recently checked out the following items. Please return them by the time indicated below. If you have already returned them, you can disregard this message.

To renew, go to: https://myaccount.lib.ncsu.edu

To return, drop them off at an NC State University Libraries service desk.

1 call number:MACBOOK PRO RETINA ID:S03278094X

Apple Laptop

due:8/2/2019,16:50

If you do not return or renew these item(s) by the time specified, you may be fined.

Thank you for taking care of this matter promptly.

NC State University Libraries Ask Us

(919) 515–3364 | library_askus@ncsu.edu

After

Subject: Thanks for checking out these items. Here’s when they’re due.

May 1, 2021

Hello,

You just checked out some item(s). Thanks for using the Libraries!

1 call number:MACBOOK PRO RETINA ID:S03278094X

Apple Laptop

due:5/1/2021,16:16

——

Can I renew these items?

These items cannot be renewed, but you may be able to check them out again from the service desk when you return them, depending on our current inventory.

Where should I return them?

Technology devices that are borrowed for short-term periods, like laptops, can be returned to any Libraries service desk.

Textbooks and Reserve items should be returned to the library where you checked them out.

What are the Libraries’ hours?

View library hours at lib.ncsu.edu/hours.

——

If you returned these items more than an hour ago, or if you have other questions, please contact us:

Email library_askus@ncsu.edu

Call (919) 515–3364

Appendix B: Patron Survey #1, Survey About Then-Current Emails

We conducted this survey in 2019 by appending an invitation to participate to six email templates sent through our ILS. The link sent users to a Qualtrics survey. We offered participants a chance to enter a raffle for a portable USB power bank (value: $25).

About this Study

NC State University Libraries would like to improve our emails to you. Your responses will be used to improve our services. If you would like to enter to win a portable USB power bank, you’ll have the chance to include your email address.

What’s this Survey About?

This survey was linked from an email from the Libraries. These questions refer to that email. Feel free to refer back to it.

Results from this survey will be published (without personally identifying information) in Libraries reports and may be used in presentations. For additional information, please contact Mia Partlow (mia_partlow@ncsu.edu).

Survey Questions

[For the first question on each survey, we asked a service-specific question tailored to the type of email the survey was linked from, such as…] When would you have preferred to receive this email?

Right after checking out the item / 3 hours before the item was due / An hour before the item was due / Not at all / Other

How clear was this email to you?

Very confusing / Somewhat confusing / Somewhat easy to understand / Very easy to understand

Conditional logic: if “Very confusing” or “Somewhat confusing” is selected, an optional sub-question appears: What did you find confusing? [short answer]

How useful was this email to you?

Not useful at all / Somewhat useful, but I could do without it / Somewhat useful, I am glad I received it / Very useful

How could we improve this email? [free-text box]

Any other comments about borrowing items from NC State? [free-text box]

[Help text:] If you have a question or request about the specific item you’ve borrowed, you should contact Ask Us at (919) 515–3364 or library_askus@ncsu.edu.

If you would like to enter to win a portable USB power bank, please tell us your email address. [email address input field]

Appendix C: Tiny Café Script and Prototypes

At this pop-up user testing event, we set up a table in the library lobby. Interested passersby sat down with us for a few minutes to give us feedback about our email prototypes in exchange for coffee and pastries. We printed the prototypes in color, since they were just images and were not interactive.

Note: we created these prototypes before investigating the limitations of our ILS, so the inclusion of a logo image and formatting like bold text did not end up in our final email templates.

Script

Hi, I’m [facilitator’s name] and this is [notetaker’s name]. What’s your name? … How long have you been at NC State? … What do you study? …

We’re asking people about some library services. The first thing I should tell you is that we’re not testing you. We’re testing how well our services work for you. I’ll be giving you some paper prototypes and asking some questions. There are no right or wrong answers. Please don’t worry that you’re going to hurt our feelings. We’re doing this to improve our services, so we need to hear your honest reactions.

[Notetaker] will be taking notes throughout this session. The notes will be used to figure out how to improve our services. In any reports we write, nothing you say or do will be attributed to you by name. This will probably take around 5 to 10 minutes.

Do you have any questions? … All right, let’s get going. [Give follow-along sheet to participant] I’ll be asking some questions; here they are printed out, in case it’s helpful.

Let’s say you checked out a charger and some other things this morning from Ask Us. Now it’s 4pm and you get this email in your inbox.

Does this tell you everything you’d expect?

Do you feel like you’d need to open this email to understand its contents?

Let’s say you open the email. Here’s what it looks like:

How clear is this email?

Very confusing / Somewhat confusing / Somewhat easy to understand / Very easy to understand

What’s useful about this email?

What is missing from this email?

Let’s say you checked these items out from Hill, but you’ll be on Centennial when the items are due and can’t go back to Hill until tomorrow. What would you do next?

When would you prefer to receive an email reminding you of due dates?

If you checked out a camera and a laptop, would you prefer two separate emails or one combined email that lists both?

Appendix D: Patron Survey #2, Survey About New Email Templates

We conducted this survey in fall 2021 with students who had previously indicated an interest in participating in user research for the Libraries. We offered participants a chance to enter a raffle for a $25 meal delivery upon completion of the survey.

About this Survey

The NC State University Libraries is seeking participants for an online survey. Participants in this study have the chance to receive a $25 meal delivery of their choice from Grubhub. If you’re interested in participating, please complete this survey before 3pm ET on Weds., Oct. 20. It’ll take about 10–20 minutes of your time. The survey asked you to log in so that we have your email to enter you into the contest to win Grubhub.

What it’s about:

The survey asks you for your feedback on some of the Libraries automated emails that users receive when they borrow items.

You don’t have to know anything about the Libraries to take the survey! We want feedback from newbies and experienced users alike.

Results from this study will be used to improve library services. No personally identifying information will be published.

What you could win:

When you complete the survey, you’ll be automatically entered into a raffle to win a Grubhub meal delivery (maximum $25).

3 winners will be randomly selected and emailed by 5pm ET on Weds., Oct. 20.

Checking Out a Laptop & Charger

Email Subject: Thanks for checking out these items. Here’s when they’re due.

November 1, 2021

Hello,

You just checked out some item(s). Thanks for using the Libraries!

1 call number:DELL POWER CORD 1 ID:S03103015D

Dell Power Adapter

due:11/07/2021,16:16

2 call number:PC LAPTOP ID:S03103016F

Dell Laptop

due:11/07/2021, 16:16

——

Can I renew these items?

These items cannot be renewed, but you may be able to check them out again from the service desk when you return them, depending on our current inventory.

Where should I return them?

Technology devices that are borrowed for short-term periods, like laptops, can be returned to any Libraries service desk.

Textbooks and Reserve items should be returned to the library where you checked them out.

What are the Libraries’ hours?

View library hours at lib.ncsu.edu/hours.

——

If you returned these items more than an hour ago, or if you have other questions, please contact us:

Email library_askus@ncsu.edu

Call (919) 515–3364

How clear is this email? [1–5 Likert scale]

How did this email make you feel? (Check all that apply)

Confident, Confused, Stressed, Informed, Respected, Other: ___

Where did you find the most important information in this email?

Top, Middle, Bottom

How would you improve the email? [free-text box]

As a student, could you foresee any confusion that you or other students may have if they received this email? [free-text box]

Overdue Notice

Email Subject: You have overdue items from the Libraries. Please return them soon.

November 8, 2021

Hello,

You checked out some item(s) from the NC State University Libraries, and they are past their due date. Please make sure they’re returned today to a Libraries service desk to avoid fines.

1 call number:DELL POWER CORD 1 ID:S03103015D

Dell Power Adapter

due:11/07/2021,16:16

2 call number:PC LAPTOP ID:S03103016F

Dell Laptop

due:11/07/2021, 16:16

——

What if I still need these items? Can they be renewed?

These items cannot be renewed and should be returned to avoid a fine. If you need longer- term access to technology items for your learning, teaching, or research, please fill out the Special Request form at lib.ncsu.edu/techlending/specialrequest.

Where should I return them?

Return these items to the library where you checked them out. If you have questions about where to return your items, please call (919) 515–3364 or reach us at lib.ncsu.edu/askus.

What are the Libraries’ hours?

View library hours at lib.ncsu.edu/hours.

How do late fees work at the Libraries?

View our late fees at lib.ncsu.edu/borrow/fines

Some items are considered “lost” if they’re late by a certain number of days. View our lost item fines and policies at lib.ncsu.edu/borrow/lost

——

If you returned these items more than 24 hours ago, or if you have other questions, please contact us to let us know:

Email library_askus@ncsu.edu

Call (919) 515–3364

How clear is this email? [1–5 Likert scale]

How did this email make you feel? (Check all that apply)

Confident, Confused, Stressed, Informed, Respected, Other: ___

Where did you find the most important information in this email?

Top, Middle, Bottom

How would you improve the email? [free-text box]

As a student, could you foresee any confusion that you or other students may have if they received this email? [free-text box]

Billing Email

Email Subject: Your Libraries account has late fees.

November 11, 2021

Hello,

You have been fined for the following item(s) because we did not receive them back on time. You can pay fines and late fees online through MyPack Portal at mypack.ncsu.edu. Payments submitted online will be reflected in your NC State University Libraries account the following day. Credit card and check payments can also be made in person at the Hill or Hunt Library. The Libraries does not accept cash payments.

1 PC LAPTOP

date billed:11/11/2021 bill reason:OVERDUE amount due: $30.00

=======================================================================

TOTAL FINES/FEES AND UNPAID BILLS: $30.00

An Appeals Committee appointed by the University Library Committee considers cases that involve extraordinary circumstances. See Petition/Appeal Process at lib.ncsu.edu/borrow/appeal. For more detailed information, view the Rules on Overdue Materials at lib.ncsu.edu/borrow/overdue.

To view your Libraries account, visit myaccount.lib.ncsu.edu.

Detailed information on fines can be found at lib.ncsu.edu/borrow/fines.

Learn more about how to pay fees online at go.ncsu.edu/onlinepayment.

Thank you for taking care of this promptly.

NC State University Libraries Ask Us

(919) 515–3364 | library_askus@ncsu.edu

How clear is this email? [1–5 Likert scale]

How did this email make you feel? (Check all that apply)

Confident, Confused, Stressed, Informed, Respected, Other: ___

Where did you find the most important information in this email?

Top, Middle, Bottom

How would you improve the email? [free-text box]

As a student, could you foresee any confusion that you or other students may have if they received this email? [free-text box]

Last Questions

We’re adding a new Q&A section at the bottom of some of our automated emails:

What if I still need these items? Can they be renewed?

View all your checked-out items and any available options to renew them at myaccount.lib.ncsu.edu/checkouts. If you don’t have any renewals left, you may be able to check the item out again by contacting Ask Us at lib.ncsu.edu/askus or coming to a service desk.

Where should I return them?

You may return your items to any NC State University Libraries service desk or bookdrop.

What are the Libraries’ hours?

View library hours at lib.ncsu.edu/hours.

How do late fees work at the Libraries?

View our late fees at lib.ncsu.edu/borrow/fines.

Some items are considered “lost” if they’re late by a certain number of days. View our lost item fines and policies at lib.ncsu.edu/borrow/lost.

——

If you returned these items more than 24 hours ago or if you have other questions, please contact us:

Email library_askus@ncsu.edu.

Call (919) 515–3364.

What are your overall thoughts about this Q&A section? [free-text box]

Is there anything else you’d like to add about library emails in general? [free-text box]

References

Blakiston, R. (2013). Developing a content strategy for an academic library website. Journal of Electronic Resources Librarianship, 25(3), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/1941126X.2013.813295https://doi.org/10.1080/1941126X.2013.813295

Blakiston, R., & Mayden, S. (2015). How we hired a content strategist (and why you should too). Journal of Web Librarianship, 9(4), 193–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/19322909.2015.1105730https://doi.org/10.1080/19322909.2015.1105730

Boyer, J., Davis, R., Hawks, S., Olson, E., Orphanides, A., & Wynn, M. (2020). Writing for the Web. NC State University Libraries. https://www.lib.ncsu.edu/web-style-guide/writing-for-the-webhttps://www.lib.ncsu.edu/web-style-guide/writing-for-the-web

Buchanan, S. (2017). A toolkit to effectively manage your website: Practical advice for content strategy. Weave: Journal of Library User Experience, 1(6). https://doi.org/10.3998/weave.12535642.0001.604https://doi.org/10.3998/weave.12535642.0001.604

Chao, Z. (2019). Rethinking user experience studies in libraries: The story of UX Café. Weave: Journal of Library User Experience, 2(2). https://doi.org/10.3998/weave.12535642.0002.203https://doi.org/10.3998/weave.12535642.0002.203

Couture, J., Bretón, J., Dommermuth, E., Floersch, N., Ilett, D., Nowak, K., Roberts, L., & Watson, R. (2021). “We’re gonna figure this out”: First-generation students and academic libraries. Portal: Libraries and the Academy, 21(1), 127–147. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2021.0009https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2021.0009

Datig, I. (2018). Revitalizing library websites and social media with content strategy: Tools and recommendations. Journal of Electronic Resources Librarianship, 30(2), 63–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/1941126X.2018.1465511https://doi.org/10.1080/1941126X.2018.1465511

Davis, R., & Sheffield, S. (2021, February 25). Emails are UX, too: How to make better overdue notices & other communications [Conference session]. Designing for Digital 2021. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4562248https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4562248

Demsky, I., & Chapman, S. (2015). Taming the kudzu: An academic library’s experience with web content strategy. In Eden, B. L. (Ed.), Cutting-edge research in developing the library of the future: New paths for building future services (pp. 23–41). Rowman & Littlefield.

Godfrey, K. (2015). Creating a culture of usability. Weave: Journal of Library User Experience, 1(3). https://doi.org/10.3998/weave.12535642.0001.301https://doi.org/10.3998/weave.12535642.0001.301

Halvorson, K. (2011). Understanding the discipline of web content strategy. Bulletin of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 37(2), 23–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/bult.2011.1720370208https://doi.org/10.1002/bult.2011.1720370208

Halvorson, K., & Rach, M. (2012). Content strategy for the web (2nd ed.). New Riders.

Harley, A. (2015, February 16). Personas make users memorable for product team members. Nielsen Norman Group. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/persona/https://www.nngroup.com/articles/persona/

Haskett, M., & Dorris, J. (n.d.). Food and housing insecurity at NC State. Academic and Student Affairs. Retrieved October 29, 2021, from https://dasa.ncsu.edu/support-and-advocacy/pack-essentials/food-and-housing-insecurity-at-nc-state/https://dasa.ncsu.edu/support-and-advocacy/pack-essentials/food-and-housing-insecurity-at-nc-state/

Hixson, T., & Parrot, J. (2021). Using UX personas to improve library GIS and data services. Weave: Journal of Library User Experience, 4(2). https://doi.org/10.3998/weaveux.221https://doi.org/10.3998/weaveux.221

Logan, J., & Spence, M. (2021). Content strategy in LibGuides: An exploratory study. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 47(1), 102282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2020.102282https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2020.102282

Mailchimp. (n.d.). Mailchimp content style guide. Retrieved February 5, 2020, from https://styleguide.mailchimp.com/https://styleguide.mailchimp.com/

McCulloch, G [@GretchenAMcC]. (2021, January 12). The young people that I’ve surveyed on this often find “Dear” uncomfortably intimate, like calling your professor your darling [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/gretchenamcc/status/1349143247722065921https://twitter.com/gretchenamcc/status/1349143247722065921

McDonald, C., & Burkhardt, H. (2019). Library-authored web content and the need for content strategy. Information Technology and Libraries, 38(3), 8–21. https://doi.org/10.6017/ital.v38i3.11015https://doi.org/10.6017/ital.v38i3.11015

McDonald, C., & Burkhardt, H. (2021). Web content strategy in practice within academic libraries. Information Technology and Libraries, 40(1). https://doi.org/10.6017/ital.v40i1.12453https://doi.org/10.6017/ital.v40i1.12453

Metts, M. J., & Welfle, A. (2020). Writing is designing: Words and the user experience. Rosenfeld.

Meyer, E., & Wachter-Boettcher, S. (2016). Design for real life. A Book Apart.

Meyer, K [11kmeyer]. (2019, December 10). Every time I get one of our library hold notices, I get a little spark of joy! I’m so glad [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/11kmeyer/status/1204554258772873216https://twitter.com/11kmeyer/status/1204554258772873216

Moran, K. (2016, July 17). The four dimensions of tone of voice. Nielsen Norman Group. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/tone-of-voice-dimensions/https://www.nngroup.com/articles/tone-of-voice-dimensions/

Newton, K., & Riggs, M. J. (2016). Everybody’s talking but who’s listening? Hearing the user’s voice above the noise, with content strategy and design thinking [Conference session]. VALA 2016: Libraries, Technology and the Future, Melbourne, Australia. https://ro.uow.edu.au/asdpapers/536/https://ro.uow.edu.au/asdpapers/536/

Nielsen, J. (1996, May 31). Inverted pyramids in cyberspace. Nielsen Norman Group. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/inverted-pyramids-in-cyberspace/https://www.nngroup.com/articles/inverted-pyramids-in-cyberspace/

Pshock, D. Introducing the user cafe. (2017, August 1). User Experience at University of Houston Libraries. https://weblogs.lib.uh.edu/ux/user-cafe/https://weblogs.lib.uh.edu/ux/user-cafe/

Rose, C., Godfrey, K., & Rose, K. (2015). Supporting student wellness: “De-stressing” initiatives at Memorial University Libraries. Partnership: The Canadian Journal of Library and Information Practice and Research, 10(2). https://doi.org/10.21083/partnership.v10i2.3564https://doi.org/10.21083/partnership.v10i2.3564

Sundt, A., & Davis, E. (2017). User personas as a shared lens for library UX. Weave: Journal of Library User Experience, 1(6). https://doi.org/10.3998/weave.12535642.0001.601https://doi.org/10.3998/weave.12535642.0001.601

Tiny café. (n.d.). NC State University Libraries. Retrieved January 26, 2022, from https://www.lib.ncsu.edu/tiny-cafehttps://www.lib.ncsu.edu/tiny-cafe

Tiny café. (2019, January 8). The University of Arizona University Libraries. https://new.library.arizona.edu/events/tiny-cafe-spring-2019https://new.library.arizona.edu/events/tiny-cafe-spring-2019

Young, S. W. H. (2016). Principle 1: Create shareable content. Library Technology Reports, 52(8), 9–14.