What It’s All About

We are all about other people’s diaries! Sounds invasive? Well, obviously, our diarists consented to us reading their journals, and we did not ask them to include much about their personal lives. But let’s take a step back and see what the diary study was all about, where it took place, and how it went.

For context, the Berlin State Library was founded in 1661 and is Germany’s biggest research library, with a general collection of over 12 million books. Several extensive special collections complete the portfolio, which is mostly used by researchers. Due to the division of Germany in the post-war period, the library building Unter den Linden became part of East Berlin. To complement it, West Germany built a second huge library in the western part of Berlin, which is now known as Haus Potsdamer Straße. In 1992 both libraries merged into one institution offering services at both sites.

Currently, the Berlin State Library is planning an extensive renovation of its modern building, Haus Potsdamer Straße. Built in the 1970s by Hans Scharoun, it is the home for all modern literature while ancient books and historical special collections reside a few kilometers away in the Wilhelmine building Unter den Linden. Scharoun designed the library as an egalitarian “reading landscape” with a lot of free space, broad visual axes, natural light, and many private corners between bookshelves and plants. Most readers and staff admire its architecture and charm, so it’s no wonder that Wim Wenders filmed some scenes of Wings of Desire there. However, fifty years later, libraries have moved on as the readers’ needs and expectations have evolved into new directions.

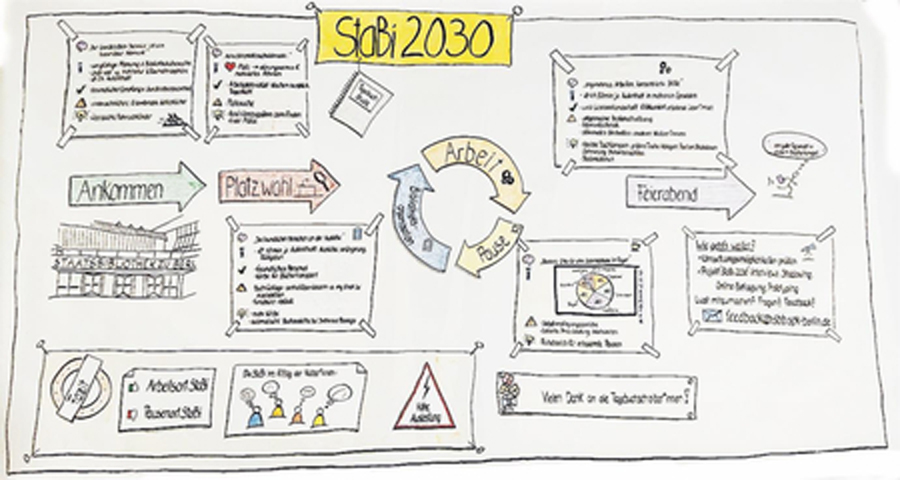

The planning process for the renovation of Potsdamer Straße started some years ago without anticipating participation of readers or staff. In 2018, following the creation of a new position for user research, a two-year project named StaBi2030—short for Staatsbibliothek/State Library—was designed to include the readers’ perspectives in the planning process. Its aim is to inform the players involved—architects, builders, and building consultants—about readers’ activities, needs, and expectations. The StaBi2030 team consists of two people who together invest about 60 percent of a fulltime equivalent employee to the project.

StaBi2030 started with a graffiti wall on which we asked readers to write, scribble, or doodle what they envision doing in the State Library in 2030, how the library of the future could facilitate these activities, and which features of the library should remain untouched. The graffiti wall stimulated more than 230 responses within two weeks. Three topics stood out: the need for communication areas that would not compromise the very quiet atmosphere of the reading room, the readers’ wish to participate in the decision-making on the library’s further development, and the need for more adequately designed spaces for break-time activities. While this method was great for engaging readers and compiling a list of topics that were, to some extent, new and unexpected, it did not allow for assessing the context tied to the topics on the graffiti wall. Nor did we know how many readers would support a comment on the wall—for instance the wish for more high tables in the reading room—or how important that comment was in relation to others, such as food and beverages in the cafeteria.

To make up for these foreseeable uncertainties we had planned two subsequent empirical enquiries: a diary study followed by a representative online survey, thus combining qualitative and quantitative data, and taking into account each method’s disadvantages. While we successfully completed the diary study in 2021, we had to postpone the online survey until 2022. But the diary study has already proved to be an excellent bridge between the graffiti wall and the survey, as we will show.

What We Did and How We Did It

For the diary study, we wanted to know what kinds of activities readers engage in during their visits, where those activities take place, and in what ways the library currently encourages these activities. In order to understand the full picture, we also wanted to find out about the frequency and the amount of time spent on different kinds of activities. A diary study seemed to be a perfect fit for these rather detailed questions that cannot be answered comprehensively and reliably with retrospective methods such as interviews or surveys. Who can really remember exactly how much time one spent at a specific spot in the reading room hours or days ago, how many breaks one took during a visit, or the causes of minor or even major interruptions and distractions?

While we preferred in situ methods over retrospective methods, we still had to pick the most adequate one for our research. We opted against shadowing or observation as a methodological approach because we expected diary entries in which readers described their own activities to be more precise and reliable than an external observer’s perspective. The activities we assumed would take up a large part of every library visit were reading, thinking, and writing—activities easily disturbed and maybe influenced by the presence of a silent person sitting nearby, observing behavior and taking notes. A reader’s own diary seemed less intrusive than observational methods and at the same time more reliable and precise than retrospective data collection.

Sampling and Recruiting

Planning started in November 2019, and we spent some time choosing an adequate sample and a useful diary format that reflected our needs and the diarists’ work routines. Our sampling strategy aimed at adequately representing basic patron groups in our sample. At the same time, we were going for maximum heterogeneity regarding those attributes we could not represent proportionally and those whose distribution among our readers we did not know. Accordingly, we looked for researchers at different stages of their careers, students, professional users with diverse backgrounds, and private readers, that is people who visit the library mostly for personal reasons such as exploring their family history. In addition, we considered people representing various disciplines and research subjects, language backgrounds, preferred working environments, disabilities, parenthood status, and experience in using the library. Balancing time schedule, effort, and expected saturation—the point at which additional participants would confirm existing data rather than providing new information—we aimed to recruit fifteen participants.

In addition to a call on the library’s website, blog, and social media sites (Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram), we created posters for various sites in the library and placed 100 flyers on desks in the reading room, at the entrance of the cafeteria, and at the information desks. See appendix A for recruiting materials. Using different online and offline communication channels was a good way to recruit participants, as registrations reached us during the whole enrollment period—about two months—via all those channels. Diarists later recommended toilet doors as another effective way to display information for library users.

As an incentive, we promised small surprises during journaling, a guided tour behind the scenes of the library, and a drawing for use of a carrel for one week. However, interviews with participants later showed that most did not notice these incentives but were motivated by personal interests such as the desire to participate in the improvement of library services and curiosity and interest in the diary method. Others expressed feelings of commitment and obligation to the library.

During the enrollment period we realized that we had not included private readers and patrons with disabilities in the sample. Hence, we published calls aimed specifically at these groups and succeeded in adjusting our sample. In the end, we received eighteen commitments for taking part in the diary study. Following our sample strategy and taking into account possible dropouts, we chose sixteen people to participate. Our sample largely corresponded to the library’s basic user groups, but there were fewer private readers and professional users without a university background compared to all registered users. Regarding other attributes such as language, age, library experience, disabilities, or parenthood status, we succeeded in creating a very heterogeneous sample. All in all, recruitment turned out to be much easier than expected as we had slightly underestimated our users’ willingness to participate.

Diary Format

Our decision to use the diary format followed from one premise: our choice of format should not disadvantage any participant. Hence, we would not conduct a purely digital diary study, as we did not expect everyone to come to the library with the required devices. It turned out that two of the diarists sometimes worked without mobile devices or laptops in the library. On the other hand a strict pen-and-paper approach promised to be elaborate and demanding for the research team as we would have to transcribe all data before starting the analysis. Taking into account additional factors such as budget restraints and GDPR requirements—a European Union regulation that unifies the rules governing the processing of personal data by most private and public controllers—as well as participants’ preferences, we decided on a pen-and-paper approach. For those who preferred, we offered a simple digital template as a diary structure. However, no diarist requested it. Furthermore, most diarists were happy about the pen-and-paper approach as it set journaling apart from their own research work. An entry in the diary did not interrupt their computer work because the diary always lay next to them, and they shifted to a different writing style when making an entry.

We asked the participants to keep a diary for three days, as we did not want to strain their engagement, and we expected less new information each day. We did not expect diarists to write on three consecutive days, especially if that did not correspond with the frequency of their visits; instead, we asked diarists to choose three authentic and, ideally, typical days in the library.

Every morning the library’s information desk provided the diarists with a small package in a colorful shiny envelope that contained a pen, paper for taking notes, an information sheet including our contact details, and a floor plan of the reading room to mark the chosen seat. We also included items for a little fun such as a card with fun facts about the library (e.g., highest reminder fee of all times), gummy bears, and sticky notes. Every legal pad had a handwritten welcome note on the first page, followed by observational tasks for the day and an example of our preferred diary structure. Day 1 started with the basic diary structure for participants to use throughout the study: participants should briefly describe every activity, noting its location and start and end times. We asked participants to enhance these entries on Day 2 with an evaluation of specific locations with respect to the activities they undertook there. On Day 3 participants added their own ideas concerning the library space and the library services—whatever suggestions for improvement they had in mind, we wanted to know. See appendix B for examples of these prompts.

Data Collection

We conducted the survey January to March 2020. This included an introductory interview with every participant, three days of journaling, and a debriefing interview with every diarist. The initial semi-structured interviews gave us insight into individual routines and preferences when using the library and when doing intellectual work in general. This included the kind of work participants wanted to accomplish with the support of the library (e.g., finishing a PhD thesis, writing a novel, etc.) and the reasons they preferred to do that in the State Library instead of other places, such as other libraries, a coworking space, home, or their offices. We asked participants to describe the course of an ordinary day in the library, their preferred spots in the library, and how often and at which time of day they usually spent time in the library. In addition to providing us with valuable context, these interviews let us explain the study’s aim and design, which stimulated interest and commitment among the participants. The interviews created an atmosphere of trust between us and the diarists, so they felt comfortable leaving their journals with us.

Overall, the diary data proved to be very useful for the analysis, and most participants felt at ease with the journaling approach. Obviously, they were familiar with the use of diaries as tools for reflecting and documenting, as Hyers (2018) described. However, for the analysis it would have been useful if all diarists had stuck more closely to the structure we had proposed. We learned that the mixture of a semi-structured diary is fine as long as diarists maintain the structure in a strict way—an aspect we did not point out strongly enough during the initial interviews.

Concerning the survey period, three days were fine but two days might have been enough as well. Some participants mentioned afterwards that they somewhat fell into journaling and spent a little too much time with their diaries because they liked to reflect. Others pointed out that days in the library are much alike and that they could not add a lot of information on Day 3. This aligns with our experience that the density of information reduced on Day 3. Two days of journaling might produce the same new value and reduce time for data cleanup considerably. Another possibility to reduce that time could be a limit of ten diarists instead of fifteen, if the sample still shows sufficient heterogeneity.

The semi-structured final interview after the journaling phase left room for queries from both sides, facilitated joint reflection on the diaries, and ensured methodological feedback for the project team. Two interviewers conducted all interviews, one responsible for interviewing and the other one in charge of documentation. The interviews were especially helpful for more deeply understanding the participants and their library use, but they were also time consuming, which, of course, we could have anticipated. Fortunately, a few close colleagues-in-training stepped in and were of crucial help. Lesson learned. While we still would opt for two interviewers instead of one with additional recording, it makes sense to spread out the start dates of the diary phase for the individual participants over several weeks.

Data Wrangling

Diaries are incredibly rich sources of data—that is what makes a diary study so insightful. However, data does not talk. To answer our research questions we had to find a reasonable way of selecting and organizing the data to extract useful information from the diaries. This was one of the most time-consuming steps in the entire study. But once we had selected the relevant data, categorized it, and put it in a well-structured Excel spreadsheet, we had the answers to many of our research questions, such as duration of stay, number and location of breaks, and time spent on library services, at our fingertips. Literature on diary studies has rarely covered this aspect in detail. In our experience this is the most important and the most difficult step, so here is a detailed description of how we proceeded.

Since one aim of the study was to learn more about how much time people spent on specific activities (e.g., breaks) and at specific places (e.g., reading room or cafeteria), we had to exclude the diaries that did not have sufficient timestamps explaining the activities. Most participants included starting times for each activity that we could use to calculate their duration. In addition, we could sometimes deduce this information from existing data. This step allowed us to see how much time the diarists spent at each location. However, some diaries were of a very literary style or just did not include enough timestamps. We searched these eight diaries for mentions of attractive or unattractive spaces, descriptions of important library functions or dysfunctions, and the like.

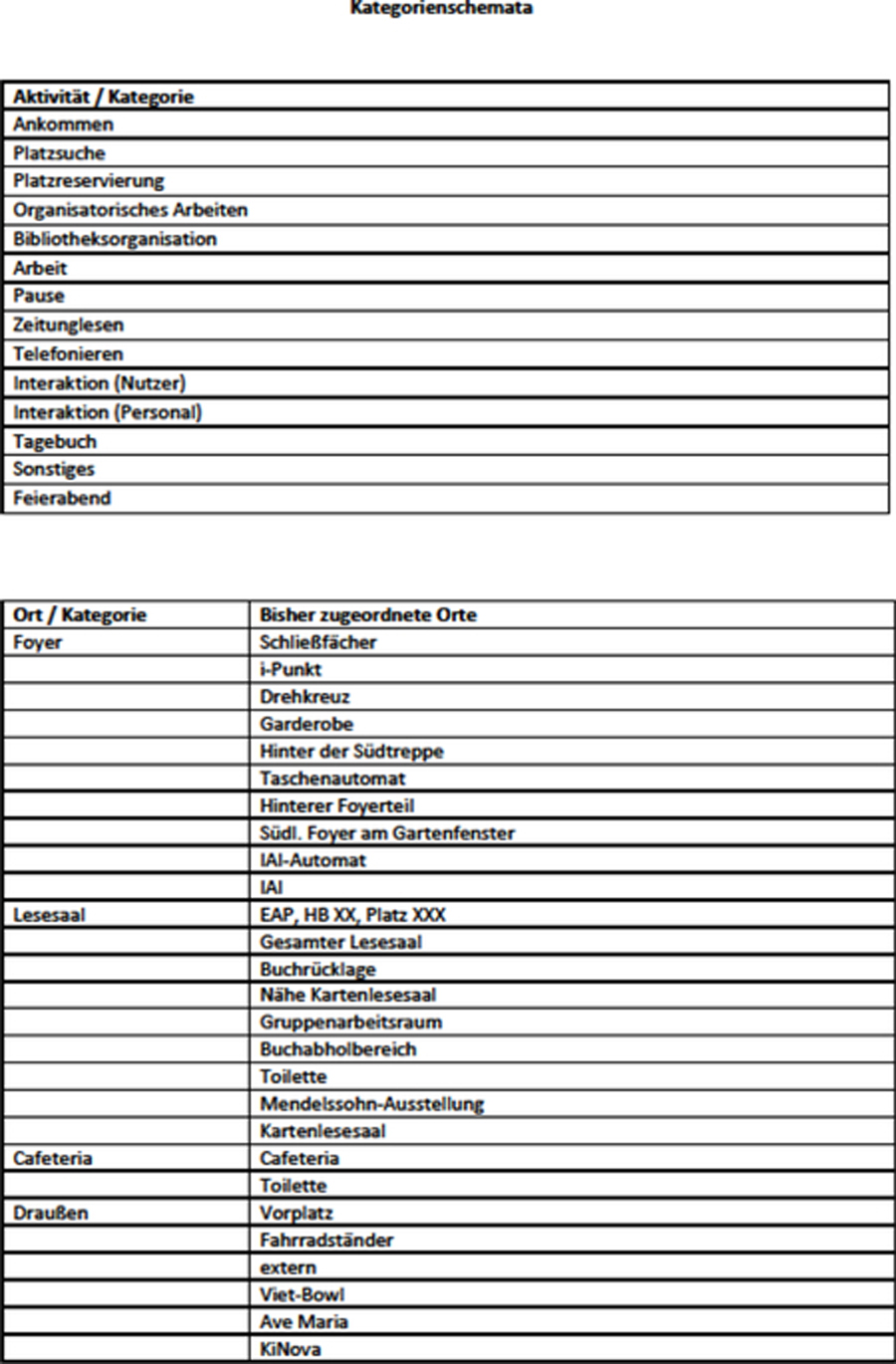

In the end, we needed to prepare thirty-seven diaries for analysis. First, we determined which activities would constitute the smallest units of our data set. Our spreadsheet contained one line for every single activity described in one of the thirty-seven diaries. For example, we treated a working session by one participant on Day 2 from 10 a.m. to 11:30 a.m. as one activity; we treated another working session by the same participant later in the afternoon as another activity. To allow for a more aggregated view of the data, we then developed a coding scheme that merged identical activities with different participant descriptions. In the end, we worked with fourteen different activities such as arriving, concentrated work, and interaction with other patrons. Next, we developed other coding schemes for locations and topics to which participants referred positively or negatively when they evaluated what they experienced in the library (library staff, lockers, behavior of other users, food, etc.).

Our aim was to describe every activity as comprehensively as possible, so we added a column for each of these aspects: date, day of the week, start time, end time, calculated duration, location as described in the diary, location code, evaluation as described in the diary, topic code, and ideas or suggestions as described in the diary. To find patterns tied to individual demographics of our participants—patron group, age, library experience, disability, international background and many more—we added columns for this information, which we had documented in the interview protocols.

At the end of the day our spreadsheet contained 884 lines—one for every activity documented—and thirty-five columns containing additional information on every activity. This was the basis of our analysis. See appendix C for excerpts from our spreadsheets.

What We Learned About the Library

The diary study produced four main findings about library usage. First, the daily structure of an average visit to the State Library becomes very clear. Second, the State Library provides a good working environment that needs minor improvements. Third, spending breaks in the State Library is not especially comfortable or relaxing. And fourth, to our readers the State Library is much more than just a place for work or books.

Visit Structure

An average visit to the State Library takes about seven hours, and readers spent two-thirds of this time with focused work on their individual project. However, that does not imply that this kind of intensive work passes without interruption. Other activities more or less regularly disrupt the concentrated focus, resulting in roughly three working episodes. Interrupting activities include about 30 minutes that go into organizational matters like answering e-mails, making phone calls, or structuring the day ahead. This kind of organizational work is less intensive but still closely connected to the individual projects or to other forms of necessary wage labor. In addition, the participants spent about 10 minutes with tasks that are part of using the library, like extending the lending period of books or managing their library account. Last but not least, readers take breaks. Of course, this fact in itself was no surprise, but we were astonished to realize that breaks did not take longer than 60 minutes total and that these 60 minutes were segmented into three smaller breaks. We had expected longer lunch breaks and—to be honest—more and longer breaks altogether.

Work Environment

It was striking that almost every diarist highlighted their pivotal reason for coming to the Haus Potsdamer Straße lies in its architecture and atmosphere. Other libraries in Berlin cannot compete with the spacious layout of the reading room, the natural light, the plants that form smaller seating areas, and the vast views throughout the building. What is maybe even more compelling is the incredible atmosphere of concentration, which results from the State Library’s status as a library used for research—a lot of reading and writing compared to less learning or group work. Concerning the working spaces themselves, the diaries described a mostly satisfactory situation. Some of the few suggestions included more storage possibilities close to patrons’ seats and reading lights that offer more options for individual adjustments.

In addition, the diaries provided a detailed model of the perfect working space in the library, which is characterized by a balanced relationship between wide space on the one hand and intimacy on the other. It is located in a quiet spot with few passers-by and half-height room dividers or shelves that block the desk from passing routes behind one’s seat. However, it allows for views through the bright reading room and to the outside—without any dazzling light. It is aligned in such a way that there is no seat opposite and so the distance to the neighboring table is large enough to ensure sufficient privacy. Given that ideal, it became clear that the existing high desks in the reading room are not in the right spot and need improvement.

Besides remarks about the temperature in the reading room and hints to worn furniture, two findings stuck out. First, most disturbances the diaries documented were due to the behavior of other library users. Second, there was no suitable library space for one activity that occurred on a regular basis: phone calls. This presents the downside to the wide and open architecture of the library. Wherever one decides to go for that one important phone call during the day, or the urgent call from a child’s daycare, other people could overhear the call. Readers feel disturbed by others, and they have to deal with an absence of privacy. More than once the diarists told the story of listening to job interviews while using the bathroom because that seemed to have been the most private location the caller could find. Since then, the library has provided call boxes that users can easily reach from everywhere inside the library.

Break Environment

Taking breaks during a seven-hour library day is crucial, and most of the documented breaks occurred either in the cafeteria, which is not open to the public, or in the spacious and public lobby of the library. The cafeteria is only accessible from the reading room, and as there is a strictly enforced no-food policy, it is not possible to bring homemade food inside the cafeteria. Hence, readers can only eat homemade food in the library’s lobby. More than half of the diarists brought their own food to the library, and they criticized the lack of suitable furniture in the lobby, such as tables and chairs for dining.

Concerning the cafeteria, the diaries showed clearly that the cafeteria’s offerings and prices do not meet the patrons’ expectations. That includes the costs for basic drinks like water that diarists perceive as quite high. This results in the common use of taps in the bathrooms to fill water bottles halfway through the day. It is no surprise that diarists described these refills as unsanitary and a little undignified. Until now, the library did not realize the importance of a more sanitary way to refill one’s drinking bottle during the day, and we definitely need to take care of that fundamental problem.

In addition, the diaries mentioned a specific kind of break we had already heard about via the graffiti wall months earlier: the power nap. It seems like the need for a short nap is as common with library patrons as with library staff—regardless of age or user group. Who is not familiar with that hour after lunch when time goes so slowly and energy levels are so low? However, we still need to figure out how urgent the need for such a designated break room is and which setup would be comfortable, practical, and truly preferred.

Other Benefits

Next to providing books, journals, and other items and apart from the working spaces in the reading room, the library fulfils a second role that is at least as important: structuring. Visiting the library helps to separate personal life from work. Opening hours support temporal structuring which may help to create a kind of everyday office routine. As the success of research work can be uncertain, aspects such as motivation, discipline, and self-control are necessary. The library fosters all these aspects through codified and non-codified behavioral expectations. Due to those expectations, some of the diarists refer to the library as “a factory” in which they voluntarily submit to visible and invisible rules helping them to “function.” In the end, there is a very German Haus und Benutzungsordnung (usage regulations) in effect which clearly regulates what people may take inside the reading room and how to behave in it.

Also, the presence and behavior of other concentrating visitors had a favorable effect on the diarists’ own work behavior and the library atmosphere. The debriefing interviews showed that users disapproved of reading room activities not consistent with the notion of “functioning” in the “knowledge factory,” such as watching videos on YouTube, engaging in social media, and in some cases even learning. To put it more positively, working next to other people who are engaged in comparable tasks helps one stay focused and motivated. It also supports acknowledging one’s own work as relevant. Even and especially if the diarists only knew their neighbors by sight and not personally, they felt socially embedded and could focus more easily.

The State Library seems to add another helpful element to the mix: it is not part of any university or research institute and as such, the library itself facilitates their work but is not expecting any results from its patrons. The State Library is a neutral space for every researcher in town, and its goal is nothing other than to help and to enable.

What Changes and Developments Resulted

The primary goal of the StaBi2030 project is to feed information on users’ needs and expectations into the planning process for the library renovation. The presentation of the projects’ main findings to the architects was a crucial first step to making the users’ perspective visible in the planning process. The library has since set up a new board for the renovation process, with a seat for every department and one for user research specifically.

The diary study also revealed numerous things that did not have to wait until the renovation to improve. Among them were small yet critical improvements in the cafeteria: we installed a second coffee machine to reduce the waiting time, and we abolished the five-euro minimum for card payments. In addition, we installed telephone booths in the reading room and the entrance hall to provide a silent and pleasant place for phone calls. And some data proved especially useful in the beginning of the pandemic, when the average duration of a library visit—7 hours in the diary study—helped us design adequate timeslots for the dramatically reduced number of people allowed in the reading room.

Other gains from the diary study are not immediately tangible but still important. For example, the library’s lack of areas where readers can spend time other than working at a desk did not come as a surprise. But backed up with empirical data, this observed knowledge became a robust fact when we discuss service improvements and priorities within the library.

The diary study also raised more questions, some of which we will cover with the online survey to come. Among the things we would like to know more exactly are questions such as how many of our users have languages other than German as their first language, how many have conditions affecting their mobility and sensory perception, how many bring their own food, and how many would support the idea of a napping area.

Recommendations for Practice

Reflecting on the course of our diary study, we found several decisions to be especially significant and some steps to be particularly in need of rigor. These are precisely the aspects the literature on diary studies emphasized (Bartlett and Milligan, 2015; Priestner, 2021; Salazar, 2015) because they deserve special attention. In this section, we look at these important points and link our observations to relevant literature.

But first it is worth noting that diary methods are much less common than other qualitative methods (Atkinson & Silverman, 1997). One of the first scholarly disciplines to engage with diary methods was psychology, and today health studies are—next to social sciences—the most common place to look for diary methods (Bartlett & Milligan, 2015). Hyers (2018) provided a comprehensive history of diaries and their research uses as well as a helpful overview of some well-known diary studies. Keeping this professional center of gravity in mind, it is no wonder that most comprehensive papers about diary methods are not found in library and information science literature. But since the narrative turn of the 1990s, diary methods became more and more popular, and marketing researchers are keen practitioners.

Library user experience itself picked up diary methods too, such as in the Cambridge FutureLib project (Murphy, 2016; Priestner, 2016) and at Edge Hill University (Jamieson, 2016). The Cambridge team tried to learn more about undergraduates’ activities, preferences, and routines on campus. At Edge Hill, a team concerned with the development of learning spaces asked students to note learning-related activities as well as thoughts, feelings, troubles, etc. However, even if Heath (2016) presented diary studies as a human-centered design approach next to shadowing, interviews, and user journey mapping, it is obvious that diary methods still have a rather hidden existence. A recent survey showed that diary studies are the method UX professionals in US academic libraries are least likely to employ (Young et al., 2020). We believe this is mainly due to the high effort diary studies necessitate and partly due to methodological insecurity in the face of the “paucity of methodologically oriented literature on diary method” (Cao & Henderson, 2021, p. 830).

In Germany, UX in libraries is an evolving field that is equipped with neither high budgets nor a lot of human power. But we also found that some smart choices can help to reduce the workload.

Choosing the Method

Deciding whether a diary method is suitable means reflecting on the kind of data you want to gather. If you are interested in qualitative information about everyday incidents, personal experiences, spatial or temporal details, the course of specific actions, or introspection, then a diary study might be a good fit. For example, Murphy (2016) did one to learn about book lending routines of students. One of the strong methodological arguments for diary studies is their ability to produce valid and reliable data by substantially reducing recall bias (Alaszewski 2006; Bartlett & Milligan, 2015; Bolger et al., 2003; Kenten, 2010). As events and impressions are documented in their natural, spontaneous context, diary studies have been praised for capturing “life as it is lived“ (Bolger et al., 2003). In our case we found that especially true when we dealt with the number and duration of specific activities (e.g., working, having a break, interacting) and events such as disturbances. Had participants reported these activities in an interview or questionnaire hours or days after they happened, recall bias would have impaired data quality considerably.

However, diaries are situated somewhere “between the spontaneity of reportage and the reflectiveness of crafted text” (Langford & West, 1999, p. 8). One should be aware of the fact that participants write their diaries with the researchers in mind. Triangulating findings from diary research with other methods, especially interviews, can mitigate self-selection or self-reflection biases (Mittelmeier et al., 2021). So if you want to explore some kind of phenomenon in depth—including context as well as feelings, perceptions, or thoughts of the participants—you still might want to go with a diary approach. If the survey should take place over an extended period of time, a diary is probably more suitable than methods like shadowing because it reduces the time necessary for data collection (Heath, 2016).

But while the diarists will do data collection for you, structuring and analyzing the data will more than counteract this benefit. You will also need time for recruiting users and for briefing and debriefing sessions, which makes a diary study a time-intensive method. The more structured your diaries are the less messy data analysis will be. If you plan on using rather unstructured diaries you should be ready to spend the largest share of your research time on data analysis and interpretation. A diary study is tied to participants’ expressive abilities and hence limited to those who are familiar with the concept of diaries and versed in such self-reflection (Hyers, 2018; Lallemand & Koenig, 2017), which makes it a method applicable for many but not all populations.

Determining the Format

In most cases, a diary method concerning library visits will build upon solicited diaries. You will commission diaries for the purpose of your study, which puts you into the position of structuring the diaries depending on your needs. Usually, you will sample participants who have exactly the knowledge you are looking for, and they will write diaries about a specific task or situation that they will not only record but also reflect on. The better you know what kind of information you need, the more precise your choice of diary can be. Therefore, the first step might be the choice between a pen-and-paper approach versus a digital one. Hyers (2018) described the pros and cons of each option. If you have access to the necessary funds, you could think about using diary software, which will enable the participants to note their observations in some kind of app via their smartphones or other device. Often it is also possible to include photography or voice messages. Bartlett and Milligan (2015) discussed the influences of technology on diary methods. On a smaller budget, you could decide to go with a messenger service, email, or text documents.

In our case, we found that a low-threshold access for all participants, institutional requirements, data protection, and limited funds combined with the hope of providing the participants with a warm and playful atmosphere indicated pen and paper rather than a more technological solution. In addition, it turned out that even diarists who, at first, were hesitant toward handwriting enjoyed it. Pen and paper contributed to an experience of self-reflection because it set itself apart from computer-based research activities. However, it is crucial to keep in mind that transcribing handwritten diaries will require a lot of time later on.

After you settle on a basic format, you need to decide how much structuring is necessary to answer your research question (Bartlett & Milligan, 2015). If you aim for detailed records that allow you to gather numerical data, then you will want to opt for a more structured diary. Jamieson (2016) described their diaries as a “log sheet with entry slots for time of day and the activity being undertaken” (p. 175).

On the other hand, if you prefer very free and open reflections you might want to give the diarists a little more space and let them develop their own structure, one that might change from entry to entry or from day to day. For our purposes, a modified version of a classical time-space diary format (Ellegård, 2019) was a good decision. We did not provide diarists with a log sheet but with a general schema for the entries, and we asked them to maintain that schema throughout their diaries. However, that did not happen in every diary, so we had to calculate missing values and exclude the diaries that did not provide the information we needed. Hence, we recommend a more rigid diary structure, which should still leave enough room for personal insights and the diarists’ priorities.

Organizing and Analyzing the Data

Organizing and analyzing the data will be time consuming because diaries tend to produce a lot of data. We did not transcribe word by word, but we extracted decisive numerical and locational data, and we paraphrased and partially transcribed activities, ratings, and ideas. We organized the first few diaries in very close exchange, and discussions sometimes took quite some time until we could figure out helpful guidelines. It became obvious that the researchers themselves are important participants in this kind of study. Even if interaction between researcher and diarist during the diary phase is not that close, researchers will be “shaping the conclusions” (Hyers, 2018, p. 79) from the moment data editing starts. Thus, you should reflect on your choices, discuss them whenever possible, and note them for transparency of the following report.

After editing the data, the first step toward analysis was coding the entries. To facilitate the content analysis, we worked with a thematic coding system that emerged from the research questions and from a cursory reading of the diaries. We followed a “constant comparative approach” (Bartlett & Milligan, 2015, p. 43) during which we discussed most codes and refined them until we achieved clearly structured data. Eventually, the coding scheme provided us with both detailed insight into our data and a good overview of what topics we needed to think about. In our experience, it is crucial to take enough time for editing and coding the data, even if that might take weeks of stamina. Regular debates within the team proved to be very fruitful. We’d always advise on a study team rather than a single researcher.

Reporting the Results

Of course, the whole point of such a study is not only to work toward a better understanding between library staff and readers, but to achieve tangible steps that improve the library in a user-orientated way (Goodman, 2011). In a conservative institution like the Berlin State Library, a report is the indispensable first step toward that goal. As we intended to spread our findings and the supporting quotes as widely as possible in the library, we tried to create a readable report that still met methodological requirements. Hyers (2018) gave an overview of different styles of reports.

We wrote a standardized section concerning research questions, sample, method, etc. followed by a narrative description of a visit to the library including all relevant findings. Charts and diagrams presenting quantitative information, such as the duration and timing of the documented library visits, the distribution of areas used for recreation episodes, and the average duration of all activity types, supported the findings. Ellegård (2019) had manifold suggestions for visualizing quantitative data from diary studies. We combined that kind of synoptic meta-diary with side notes that allow easy navigation through the report.

Having satisfied the formal requirements, we translated the findings into visual presentations and designed a poster, which we presented in the reading room. We also wrote short summaries for the library’s blog. See appendix D for our reports. We presented the study to our colleagues on several occasions, which helped to install the project as a valuable source of information for strategic decisions. For instance, the current pandemic forced the library to regulate access to the reading room in order to comply with hygiene regulations. As the library wants to allow as many readers as possible in the reading room while offering adequate timeslots for concentrated work, the diary study helped us determine the ideal duration of bookable timeslots.

However, tangible improvements do not seem to result from any kind of report automatically. Library staff tends to be overwhelmed with day-to-day tasks, so it is hard to really engage with changes or take charge of needed improvements and push them forward. That is why we decided to offer workshops to stakeholders in the library to develop action plans and put them into place. We are curious to find out whether we will be able to encourage our colleagues sufficiently to really get things done. Let’s hope so.

Ten Questions Worth Considering

We want you to benefit from our experiences, so here is a quick checklist you can consult if you think about trying a diary method yourself. Just go through the questions, and we are sure you will cover the most important decisions concerning diaries:

Is a diary method the right tool for your research question(s)?

Are you aware of the time commitment and workload of a diary method? Will there be a team or at the very least temporary support from colleagues?

Is your targeted user group at ease with techniques of self-reflection and able to do that through written or spoken language?

Are there any specific requirements your sample should meet?

Will you use any kind of technology for the diaries? If yes, how will you deal with technical problems?

Are you looking for structured, semi-structured, or unstructured data?

Will participants be able to contact you during the diary phase if there are any questions or concerns?

How will you edit the data? Did you prepare an initial coding scheme to refine continuously?

Are you writing a narrative report that will grow while you analyze your data?

In what ways will you transform your findings into tangible actions?

Appendix A: Recruitment

Blogpost

Our call for participation in the library blog announces the diary study, explains the StaBi2030 project context, names the main research questions, invites onsite users of different demographics to take part in the diary study, offers incentives, and explains the enrollment procedures.

Recruitment Flyer

The flyer contains context on the diary study and has a one-page questionnaire (left page) we asked potential participants to fill out with their names, contact information, and other information such as library user type (casual vs. power user), preferred noise level in the reading room, user group, and particular perspective (e.g., international background). The questionnaires were returned at the service desks and were a great support during sampling.

Appendix B: Data Collection

Diary Prompt 1

The first page of every diary was a welcome note from the project team explaining what to do and where to return the diary at the end of the day as well as announcing an example entry on the following page.

Diary Prompt 2

The diary structure and examples for entries are on the second page of the diary (here for Day 1). Besides name, date, and time we asked participants to write where they spent their time, what exactly they did, and why they chose that specific spot for that activity. On Days 2 and 3 we added more elements: assessment of the library areas and ideas for improvement.

Appendix C: Analysis

Data Spreadsheet 1 (Excerpt)

The original data spreadsheet is an Excel file with 884 lines and 35 columns. In the excerpt we swapped the axes for easier display. Data on the participants are blue and refer to aspects such as age (in this case, 30–35), user group (PhD student), discipline (history of science), project (thesis), frequency of library visits (almost daily), preferred noise level (moderate, does not mind noises from the information desk, does not use earplugs), and others. The gray entries are activities and activity-related information such as date, day of the week, diary number, start time, end time, and duration. Next to the activities (emailing, scheduling and coffee break) are activity codes (organizational work and having a break), location and location code (reading room and cafeteria) and evaluative comments, such as, “Sitting here because the ventilation is too noisy in other reading room areas. Very disturbing and distracting,” and, “Unfortunately they do not have newspapers here [in the cafeteria].”

| Person (ID) | 2m | 2m | (…) |

| Alter | 30–35 | 30–35 | |

| Nutzung als… | Doktorand*in | Doktorand*in | |

| Fachinteresse… | Wissenschaftsgeschichte | Wissenschaftsgeschichte | |

| Nutzungsanlass | Dissertation | Dissertation | |

| Nutzungsintensität | fast täglich | fast täglich | (…) |

| StaBi-Seniorität (in Jahren) | 2 | 2 | |

| Bestandsnutzung | Magazin, HB, Zeitschriften, selten Fernleihe | Magazin, HB, Zeitschriften, selten Fernleihe | |

| Endgeräte | Laptop | Laptop | |

| durchschn. Aufenthaltsdauer (h) | 9 | 9 | |

| Internationalität | Nicht erkennbar | Nicht erkennbar | |

| präferierte Arbeitslautstärke | angenehm ruhig (keine Ohrstöpsel und Auskunftsgeräusche sind nicht störend) | angenehm ruhig (keine Ohrstöpsel und Auskunftsgeräusche sind nicht störend) | |

| Warum PST? | Architektur/Design, außerdem relevanter HB-Bestand | Architektur/Design, außerdem relevanter HB-Bestand | |

| Perspektive auf UdL? | |||

| Wohnort Berlin? | Berlin | Berlin | |

| Arbeitsort Berlin? | Berlin | Berlin | |

| Behinderung? | Nicht erkennbar | Nicht erkennbar | |

| Elternschaft? | Nein | Nein | |

| Lieblingsplatz /-bereich | HB5 bei Pflanzen | HB5 bei Pflanzen | |

| Mischnutzung? | nein, versucht Beruf/Privatleben zu trennen | nein, versucht Beruf/Privatleben zu trennen | |

| Rolle der SBB | Arbeitsort, “Büroersatz” | Arbeitsort, “Büroersatz” | |

| Tag (Datum) | 27.1. | 27.1. | |

| Wochentag | Donnerstag | Donnerstag | |

| Tagebuchtag | 1 | 1 | |

| Uhrzeit (Start) | 9:31 | 10:18 | |

| Minuten (Dauer) | 47 min | 12 | |

| Aktivität_Paraphrase | Emails und Terminplanung | Kaffeepause am Stehtisch | |

| Akt_Kategorie | Organisatorisches Arbeiten | Pause | |

| Ort | EAP, HB5 | Cafeteria | |

| Ort_Kategorie | Lesesaal | Cafeteria | |

| Text Bewertung | „ein sehr wichtiger Grund, warum ich gerade hier sitze: es gibt keine Geräusche von der Luftung! An anderen Stellen hört man die Klimaanlage / Heizung sehr stark. Das finde ich ganz furchtbar. Es lenkt mich sehr ab.“ | „Leider gibt es keine Zeitungen hier. Schade.“ | |

| Bezugspunkt/Thema | Klima | Cafeteria | |

| Positiv | |||

| Negativ | x | ||

| Ideen |

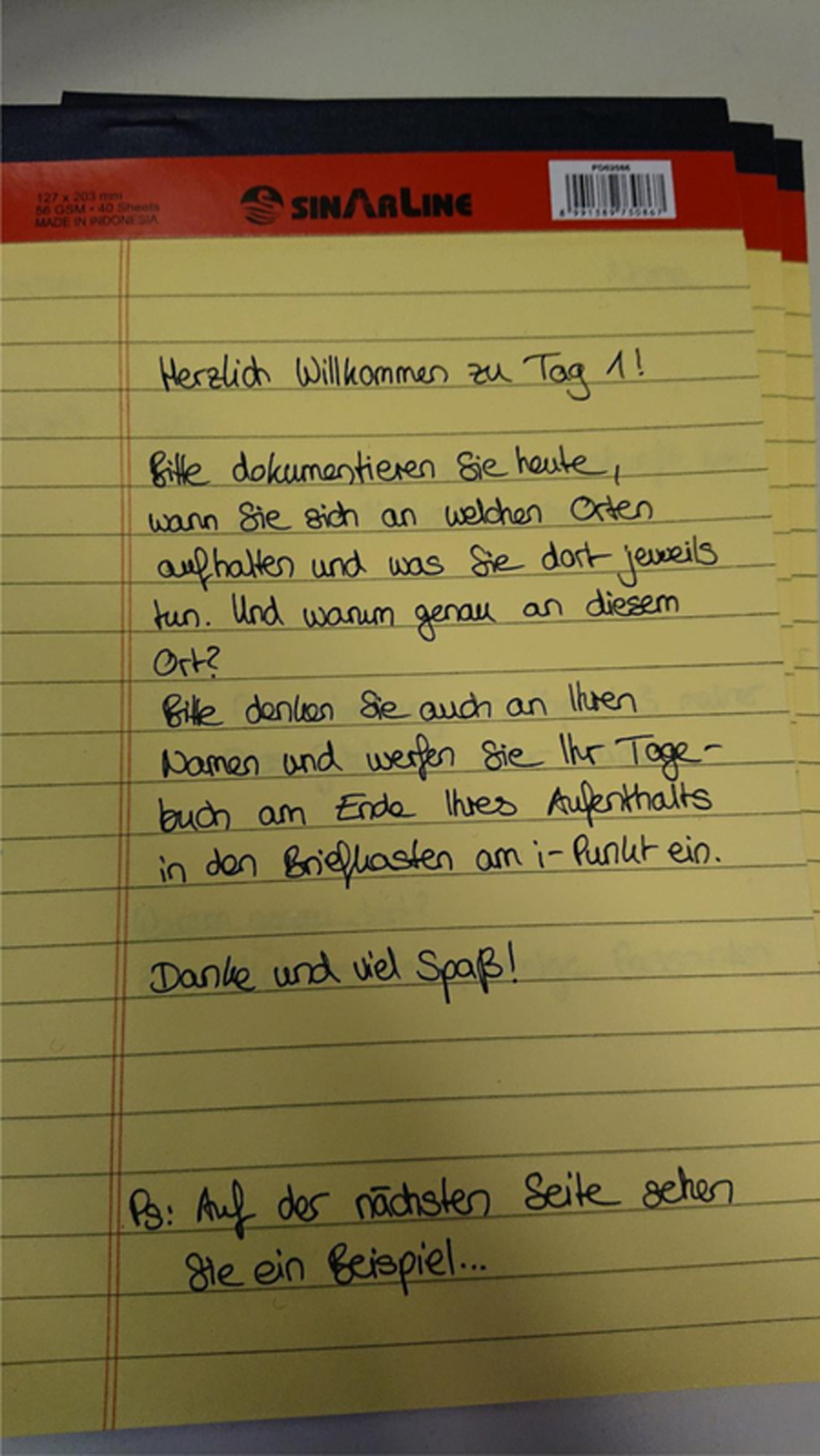

Data Spreadsheet 2 (Excerpt)

We used the spreadsheet for aggregating the data in different ways. In this excerpt, we display the activity structure of every documented library visit using a color for each activity, such as arriving at the library (light grey), finding a desk (dark grey), doing organizational work (red), working on the project (pink), or having a break (blue). We added locations in an extra column next to the activities. The size of each cell does not indicate the duration of the activity.

Coding Vocabulary

The first table shows how we used coding to cluster activities into general categories, such as arriving, finding a desk, working, doing organizational work, and interacting with other visitors or with library staff. We also used coding to cluster locations, as in the second table. For instance, we used the code “foyer” for those activities that took place at the lockers, the information desk, the entrance control, and other areas.

Appendix D: Reporting

Report

We published the full report on the library website and announced it in the library blog.

https://blog.sbb.berlin/wp-content/uploads/Tagebuchstudie_final.pdf

Blogpost

The blogpost states the main results of the study, contains a link to the report, announces further UX activities, and invites users to participate in the StaBi2030 project.

https://blog.sbb.berlin/stabi-2030-ergebnisse-der-tagebuchstudie/

References

Alaszewski, A. (2006). Using diaries for social research. SAGE Publications.

Atkinson, P., & Silverman, D. (1997). Kundera’s immortality: The interview society and the invention of the self. Qualitative Inquiry, 3(3), 304–325. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F107780049700300304https://doi.org/10.1177%2F107780049700300304

Bartlett, R., & Milligan, C. (2015). What is diary method? Bloomsbury. http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781472572578http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781472572578

Bolger, N., Davis, A., & Rafaeli, E. (2003). Diary methods: Capturing life as it is lived. Annual Review of Psychology, 54(1), 579–616. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145030https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145030

Cao, X., & Henderson, E. F. (2021). The interweaving of diaries and lives: Diary-keeping behavior in a diary-interview study of international students’ employability management. Qualitative Research, 21(6), 829–845. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1468794120920260https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1468794120920260

Ellegård, K. (2019). Time-space diaries. In Kobayashi, A. (Ed.), International encyclopedia of human geography (2nd ed., Vol. 13, pp. 301–311). Elsevier.

Goodman, V. D. (2011). Qualitative research and the modern library. Chandos Publishing.

Heath, P.-J. (2016). Applying human-centered design to the library experience. In Priestner, A., & Borg, M. (Eds.), User experience in libraries: Applying ethnography and human-centered design (pp. 49–67). Routledge.

Hyers, L. L. (2018). Diary methods: Understanding qualitative research. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190256692.001.0001https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190256692.001.0001

Jamieson, H. (2016). Spaces for learning? Using ethnographic techniques: A case study from the University Library, Edge Hill University. In Priestner, A., & Borg, M. (Eds.), User experience in libraries: Applying ethnography and human-centered design (pp. 173–177). Routledge.

Kenten, C. (2010). Narrating oneself: Reflections on the use of solicited diaries with diary interviews. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 11(2). https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-11.2.1314https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-11.2.1314

Lallemand, C., & Koenig, V. (2017). Lab testing beyond usability: Challenges and recommendations for assessing user experiences. Journal of Usability Studies, 12(3), 133–154.

Langford, R., & West, R. (1999). Marginal voices, marginal forms: Diaries in European literature and history. Rodopi.

Mittelmeier, J., Rienties, B., Zhang, K. Y., & Jindal-Snape, D. (2021). Using diaries in mixed methods designs: Lessons from a cross-institutional research project on doctoral students’ social transition experiences. In Cao, X., & Henderson, E. F. (Eds.), Exploring diary methods in higher education research: Opportunities, choices and challenges (pp. 15–28). Routledge.

Murphy, H. (2016). WhoHas? A pilot study exploring the value of a peer-to-peer sub-lending service. In Priestner, A., & Borg, M. (Eds.), User experience in libraries: Applying ethnography and human-centered design (pp. 103–107). Routledge.

Priestner, A. (2016). Illuminating study spaces at Cambridge University with Spacefinder. In Priestner, A., & Borg, M. (Eds.), User experience in libraries: Applying ethnography and human-centered design (pp. 94–102). Routledge.

Priestner, A. (2021). Diary studies. In Priestner, A. (Ed.), A handbook of user experience research & design in libraries (pp. 219–234). UX Lib.

Salazar, K. (2016). Diary studies: Understanding long-term user behavior and experiences. Nielsen Norman Group. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/diary-studieshttps://www.nngroup.com/articles/diary-studies

Young, S. W. H., Chao, Z., & Chandler, A. (2020). User experience methods and maturity in academic libraries. Information Technology and Libraries, 39(1). https://doi.org/10.6017/ital.v39i1.11787https://doi.org/10.6017/ital.v39i1.11787