One of the recurring themes of my first book, Vénus Noire: Black Women and Colonial Fantasies in Nineteenth-Century France, was the production of Black women as ultimate Others in white and male supremacist representations, which rely on nonsensical and animalistic terminologies to denigrate these women.1 There are multiple stories told about Black women, despite what was true. We cannot ignore them because they were symptoms of larger ideas and stereotypes about Blackness in France. My work is intended to push against the racist tropes of those stories and to examine the roles Black women have played historically and in the French imagination.

Recent work, much of it done by Black women scholars, has focused on finding and deciphering “fragments” of Black women’s experience/lives, using them creatively to generate historical narratives. I keep returning to the guidance of Saidiya Hartman’s “Notes on Method” in Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women, and Queer Radicals. She writes: “I have pressed at the limits of the case file and the document, speculated about what might have been, imagined the things whispered in dark bedrooms, and amplified moments of withholding, escape and possibility, moments when the vision and dreams of the wayward seemed possible.”2 My work as a historian of race and gender in nineteenth-century France doesn’t always lend itself to more traditional forms of engagement with the archives. Like Hartman, my job is to read the silences in historical documents.

What I have found in writing about Suzanne Simon Baptiste Louverture is that there are more than fragments from which to choose. Had anyone bothered to look for her, they would have found more, a lot more. As a historian, this puts me on alert to how easy it is to expunge a person from the historical record. We have documents that attempt to tell stories about Suzanne: as an object to be moved about, as a nuisance to be managed, a problem to be solved. What these documents don’t articulate – because the very idea was terrifying – is that their authors thought of Suzanne as a “container” of secret knowledge; she remained constantly in their thoughts, taking up space in their collective psyches. Read critically for all they do and do not say, administrative and cultural archives are thus sources that can be used to reconstitute Suzanne’s life. A biography of her, and other Black women like her, is possible.

However, women like Suzanne make impossible conventional, linear biographies such as those of the “great” white men who leave copious amounts of documents that allow us to piece together their whole lives. We do not have much of Suzanne’s writing, either because she chose not to leave more behind, or because no one thought her work important enough to save. My upcoming book is a “microbiography” that brings together both microhistory and biography. Finding meaning in “small” moments, people, or events, microhistory shows us that ordinary people matter as subjects. It can, for example, enhance our understanding of all that went on behind the scenes of the Haitian Revolution, that famous yet under-taught chapter of the Haitian past, and of the histories of French, Spanish, British, and American colonialism, including enslavement, race, gender, and sex.

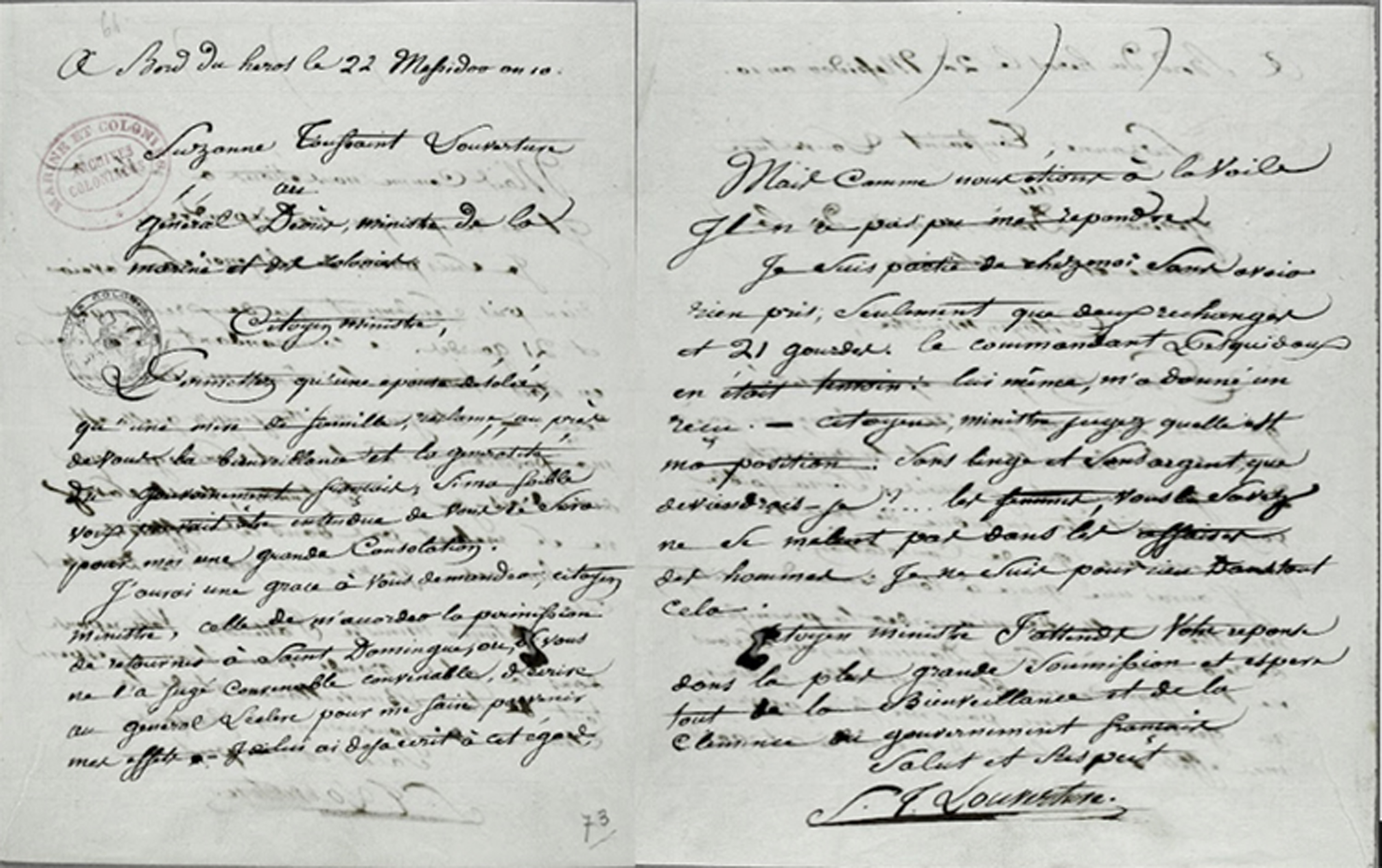

In June of 1802, after months of harassment and the forced retirement of Suzanne’s husband Toussaint Louverture, the French military, under the direction of Napoleon Bonaparte, kidnapped the family and transported them to France. The following is one of the few documents we can ascribe to Suzanne: a letter to the Minister of the Navy, General Decrès. It is dated July 1802, just as the Héros, the ship that carried Suzanne from Saint Domingue, neared its first destination of the military port of Brest, France. The document indicates that she wrote other letters, including one to General Leclerc and another to Commander Pisquidoux. While those letters have not survived, it is important to note that Suzanne knew who these three powerful men were, and that she felt emboldened to write to them. Moreover, she expected them to take her seriously. Her demands were significant, even if they were ultimately ignored.

The letter is thus stunning for what it says, what it implies, and what it leaves to a reader’s imagination. She writes:

Citizen Minister,

Allow a sorry wife, a mother of a family, to claim from you the benevolence and generosity of the French government, if my weak voice could be heard by you, it will be a great consolation for me. I will have a favor to ask of you, Citizen Minister, that of granting me permission to return to Saint-Domingue, or, if you did not consider it suitable suitable [sic], to write to General Leclerc to - to send me my belongings. I have already written to him in this regard. But since we had set sail, he couldn’t answer me. I left home without having taken anything, only a few spare parts and 21 gourdes [meaning: monetary currency of Santo Domingo]. Commander Pisquidoux witnessed it. He himself gave me a receipt - Citizen Minister, judge what my position is. Without laundry and without money, what would become of me? … women, you know, don’t get involved in men’s affairs. I have nothing to do with all of this. Citizen Minister, I await your response in the greatest submission and hope for all the benevolence and leniency of the French government.

Greetings and respect

S. T. Louverture.3

By the time the letter came into being, Suzanne had been in the same clothes for almost a month; she was probably uncomfortable and sticky from the humidity. The handwriting is different from her earlier letters, indicating that she may have dictated it to someone, possibly one of her two sons. It is also possible that the ship’s secretary wrote the letter for her. Would she have dictated it in Creole or in fractured French, as she paced within the small cabin? Other documents, including a letter in her own hand, demonstrated her ability to write in both French and Creole. This letter, while clearly in Suzanne’s voice, shows an elevated level of French. One wonders, if it was dictated, if she asked the person writing for her to read it back to make sure her thoughts were properly conveyed? Did the guard assigned to watch her at all times hear it as well? This makes sense given that Suzanne’s every move was scrutinized and surveilled. Might this have influenced what she said?

Suzanne addressed the minister with the due deference expected of her. This situates her narrative strategies within a long history of women writing self-deprecatingly, in correspondence and in print, to protect themselves from ridicule and exercise their agency by working within the discourses available to them. In this way, the letter is part of a much broader set of cultural practices. Suzanne, however, had the additional burden of enslavement to circumvent. While technically free according to the laws of 1794, her captors neither recognized this nor afforded her any agency.

But Suzanne was nevertheless assertive, despite the conventions that might have insisted upon total supplication. The French government had been neither benevolent nor generous to her family, and the minister knew this. And while her recipient might have regarded her voice as meaningless, it was the act itself of writing the letter that made Suzanne’s belief in her own power clear. Given all that it had taken to capture her (the kidnapping of the family had been a disaster of missed opportunities), there was little chance that Suzanne would ever be allowed to return home. She also noted in the letter that she had little in the way of finances. Wherever the family ended up, they would not be properly cared for. Her only means of making money was laundry. Suzanne did not ask for Toussaint’s freedom in the letter. Perhaps she knew that this request was out of the question? Or that getting back to Saint Domingue and back in control of the family’s operations might provide her with the leverage to free him later? Perhaps the best she could hope for was that some of the family would survive.

Finally, and I think most importantly, Suzanne utterly denies her own political agency on the basis of her sex: “… women, you know, don’t get involved in men’s affairs. I have nothing to do with all of this.” This statement was savvy on more than one level. While Suzanne was certainly aware of various Revolutionary activities, it would not have helped her case as a prisoner to highlight that fact. Instead, she banked on the powerful men she was corresponding with to assume that, as a Black woman, she knew very little. It is interesting to note the parallel between Suzanne’s strategy in her letter and the statement Marie Antoinette made at her own trial, asserting her lack of knowledge in order to save herself. Both instances–from a Black woman and a white Queen–relied and drew upon much larger sets of cultural practices.

She put them in a bind: if they acknowledged her true power, they would undermine the gender hierarchy so important to early-nineteenth century France. Claiming she had no idea what was going on, Suzanne also put her French captors in the position of having to explain why they had kidnapped a defenseless woman. At the same time, other documents imply that French officials were convinced that she knew about hidden treasures, treasures that a financially strapped Napoleon desperately wanted. This indicates that French authorities didn’t completely believe their own gendered rhetoric.

The story of Suzanne Simon Baptiste Louverture reveals incredible moments of her own self-expression: of sorrow, worry, and sadness that also morphed into anger, rage, vulnerability, resilience and beauty. We don’t always have a clear view into her thoughts, but there is ample evidence that highlights how she responded in certain situations. These invite speculation about her thinking. We know that Suzanne wrote to men – both Black and white – in great positions of power, and that she expected that they would answer her. Oftentimes, they did, giving us important information about the men she wrote to. It also shouts back against the French fictions created about her importance and helps explain efforts to erase her. By uncovering her life story, I hope to highlight another perspective of colonial history, one where colonial power met up against resistance, re-centered in the body of a Black woman as a historical figure in her own right.

Notes

- Robin Mitchell, Vénus Noire: Black Women and Colonial Fantasies in Nineteenth-Century France (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2020). ⮭

- Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiment: Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women, and Queer Radicals (New York: W. W. Norton & Company; Reprint edition, 2020), xiv. ⮭

- Letter from Suzanne Toussaint Louverture to the Minister of the Navy and Colonies, 22 July 1802 (22 Messidor an 10), 117–118, “Toussaint-Louverture, St Domingue,” EE 1734, Archives Nationales d’Outre Mer, Aix-en-Provence, France.

A bord du héros, le 22 Messidor an 10

Suzanne Toussaint Louverture

Au général Decrès, ministre de la Marine et des colonies

Citoyen ministre,

Permettez qu’une épouse désolée, qu’une mère de famille, réclame auprès de vous la bienveillance et la générosité du gouvernement français, si ma faible voix pourrait être entendue de vous ce sera pour moi une grande consolation.

J’aurai une grâce à vous demander, citoyen ministre, celle de m’accorder la permission de retourner à Saint-Domingue, ou, si vous ne l’a jugé convenable convenable [sic], d’écrire au général Leclerc pour me faire parvenir mes affaires — je lui ai déjà écrit à cet égard.

Mais comme nous étions à la, il n’a pas pu me répondre.

Je suis partie de chez moi sans avoir rien pris, seulement quelques rechanges et 21 gourdes [meaning: devise monétaire de Saint-Domingue]. Le commandant Pisquidoux en était témoin. Lui-même m’a donné un reçu - citoyen ministre, jugez quelle est ma position. Sans linge et sans argent, que deviendrais-je? … les femmes, vous le savez, ne se mêlent pas dans les affaires des hommes. Je ne suis pour rien dans tout cela.

Citoyen ministre, j’attends votre réponse dans la plus grande soumission et espère tout de la bienveillance et de la clémence du gouvernement français.

Salut et respect

S. T. Louverture. ⮭

Robin Mitchell is the College of Arts and Sciences Endowed Professor and an award-winning Associate Professor in the Department of History at the University at Buffalo. She is the author of Vénus Noire: Black Women and Colonial Fantasies in Nineteenth-Century France (University of Georgia Press, 2020). Her forthcoming book (under contract with Princeton University Press) will be the first biography of Suzanne Simone Baptiste, also known as Madame Toussaint Louverture.