Translator’s Introduction

The short story “A Modern Bride and Groom” (Haynt veltige khosen kalla) by Sara Familiant, was published in 1894 in volume 3 of Hoyzfraynd (Friend of the house), an important five-volume anthology of Yiddish writing edited by Mordkhe Spektor and published in Warsaw. Much is known about Spektor and about Yiddish in Warsaw, but I have been unable to find a single word about—or another word by—Familiant despite an exhaustive search. This is not as unusual as one might suppose. Pre-twentieth-century Yiddish literature has received considerably less attention than later works—women’s prose even less. I was drawn to this story because Familiant reflects on the themes that most concerned her male contemporaries: poverty, labor, class, modern romance. And, unlike almost every one of her contemporaries, she does so by considering what all this may mean to women. How are young women to understand the modern emphasis on love rather than arranged matches? What, indeed, does it mean to be “modern”? The last line of the story is both a plaint and a challenge: “Who needs to be concerned about a poor, unfortunate girl” in late nineteenth-century Poland, or here and now?

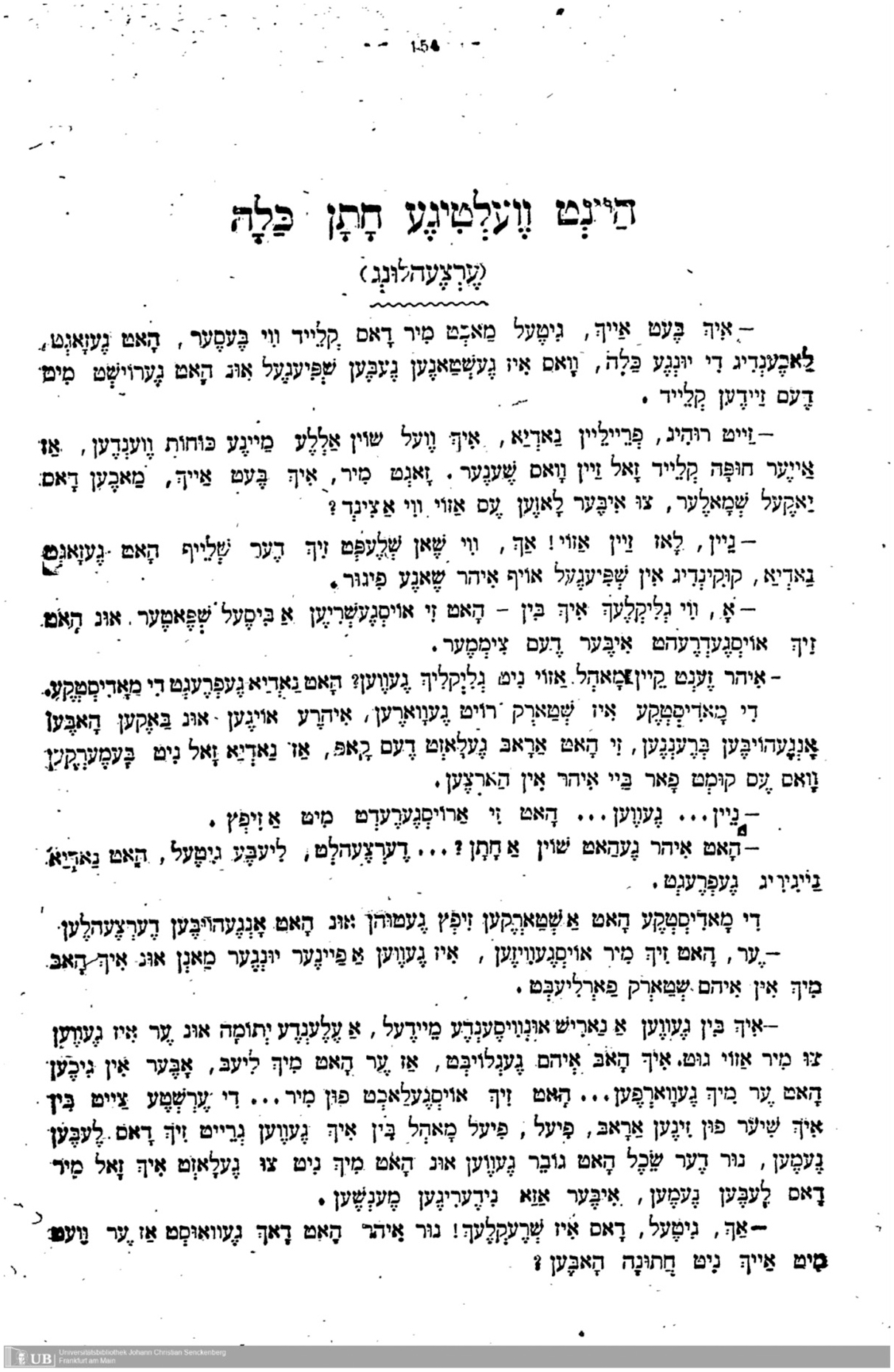

“A Modern Bride and Groom”

“Please, Gittel, make this dress as pretty as possible,” said the young bride cheerfully as she stood near the mirror swishing her silk dress.

“Don’t worry, Miss Nadja. I’ll use all my powers to make your bridal dress beautiful. Tell me, please, should I take in the jacket or leave it as is?”

“No, leave it! Oh, how beautifully the veil flows,” said Nadja, admiring her pretty figure in the mirror.

“How happy I am!” she exclaimed a little later as she paced the room.

“Have you ever been this happy?” Nadja asked the seamstress.

Gittel blushed. Her eyes and cheeks burned. She lowered her head so Nadja would not notice her agitation.

“No … I was …” she sighed.

“Did you have a groom? … Tell me, dear Gittel,” Nadja said, full of curiosity.

The seamstress sighed deeply and began to tell her story.

“He seemed like such a fine young man. I fell deeply in love with him. I was a silly ignorant girl, a lonely orphan, and he was so good to me. I believed him when he said he loved me, but soon he threw me away … He laughed at me … At first, I almost lost my mind. Often—very often—I was ready to take my own life, but common sense won out and kept me from letting such a lowly person lead me to suicide.”

“Oh, Gittel, how awful! But you must have known he wouldn’t marry you?”

Gittel’s face clouded over. “No. If I had known, I would never have gotten together with such a person.”

Her cheeks burned. Her lips trembled. “He threw me away, just as all the ‘modern young people’ do with young girls like me.”

“Poor Gittel! But you’re still young. You can still be happy!”

“No,” answered the seamstress bitterly. “I vowed never to believe anyone anymore. All men are deceivers.”

“Certainly not all!” said Nadja happily. “For example, take my fiancé. He would never deceive me. He is so good. Have you seen him?”

“No!”

At that moment, the door opened and a young man came in.

“Here he is!” exclaimed Nadja.

Gittel turned deathly pale and was barely able to stand on her feet. “That’s him … My … Yakov!” she exclaimed.

Frightened, Nadja looked at her fiancé and then at Gittel. The young man was smiling as he went into the adjoining room. Nadja followed him. He embraced her and gave her a kiss. She pushed him away.

“Listen,” she said, “were you ever the seamstress’s fiancé?”

“Fiancé?!?” he said, laughing. “What do you mean, her fiancé!?”

“She just told me …”

“Oh, darling, what do you think? Do you think I should have married her? And who would take my dear Nadja?”

He embraced her. This time, she did not push him away.

“One doesn’t marry such people!” he said and laughed cynically. “Certainly not. It’s a joke. Foolishness. Playing at love … Let her think … The devil take it …! She cost me a lot of money …”

A few days later, Nadja was married with great fanfare. Near the door of the synagogue, the couple met Gittel’s eyes, red from crying, but they walked past as if they had not noticed her. And their smiles never changed. Just then, a thought came into the bride’s head: What a silly girl! To come here and cry!

No one noticed Gittel and her tears. Indeed, who needs to be concerned about a poor, unfortunate girl—a seamstress?