Translators’ Introduction

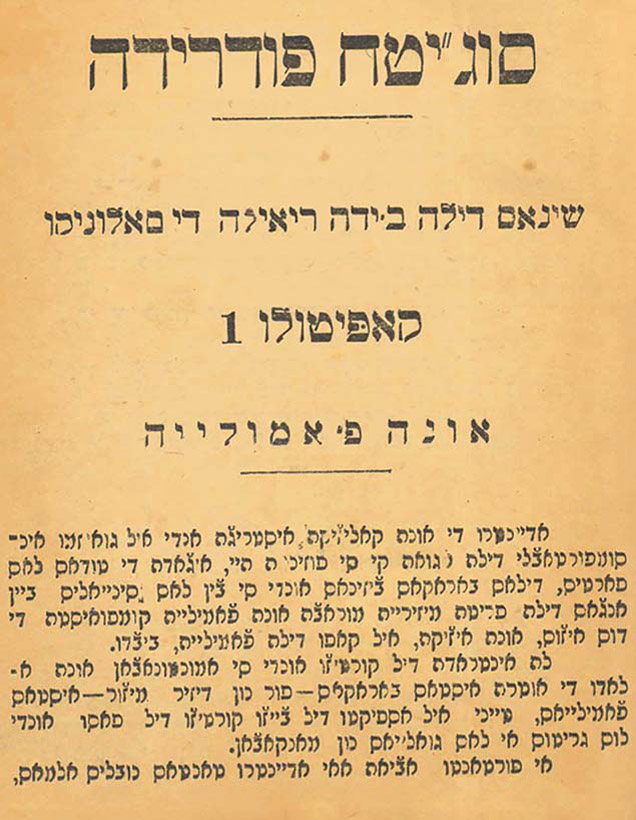

The novel Sochetá podrida: Shenas dela vida reala de Saloniko (Rotten Society: Scenes of Real Life in Salonika) by Shemtov Revah was published around the end of 1930. It was written in Ladino using the Rashi script, which was commonly used to print Ladino works, but by this time was already replaced by the Latin script in places that became part of the Turkish Republic. The story is set in Salonika (Thessaloniki), Greece, a city that had become home to a large Sephardic community after their expulsion from Spain. The city had been under Ottoman control before it was annexed by Greece in 1913, which is reflected in the use of vocabulary derived from both Turkish and, to a lesser extent, Greek in the novel.

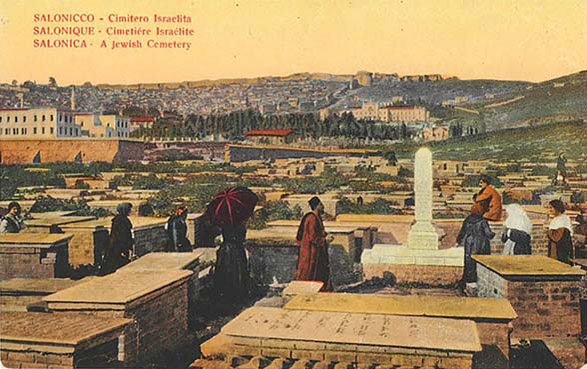

Until the Balkan Wars (1912–13) and the city’s annexation by Greece, Salonika was known across the Jewish world as the only place where Jews were the majority population and was often referred to as “Jerusalem of the Balkans” and “City and Mother in Israel.” At the time this novel was published, the city still had a substantial Jewish population, though it had decreased significantly as a result of wars, emigration, and the Great Fire of 1917, which burned through the city. The fire left more than 50,000 Jewish residents homeless. Half of the population emigrated while many others were pushed to the suburbs of the city.1 By the end of the Second World War (1939–45), more than 90 percent of the city’s remaining Jewish residents had been killed. Rotten Society is one of a handful of novels narrating the last decade in the existence of this once robust Jewish community.

The novel is set in an impoverished Jewish neighborhood called Teneke Maale, whose name comes from the words for “tin quarter” in Turkish. What follows is a translation of excerpts from the first three chapters of the novel, titled “Una familia,” “Une muerte,” and “Sola en la vida.” The story follows a young Jewish woman named Sara who lives with her father and two brothers. In the preface, the author explains that the novel seeks to “walk among the masses” and “dare to see their suffering and their joys” in order to confront readers with the extent of the decay that spread in their society.

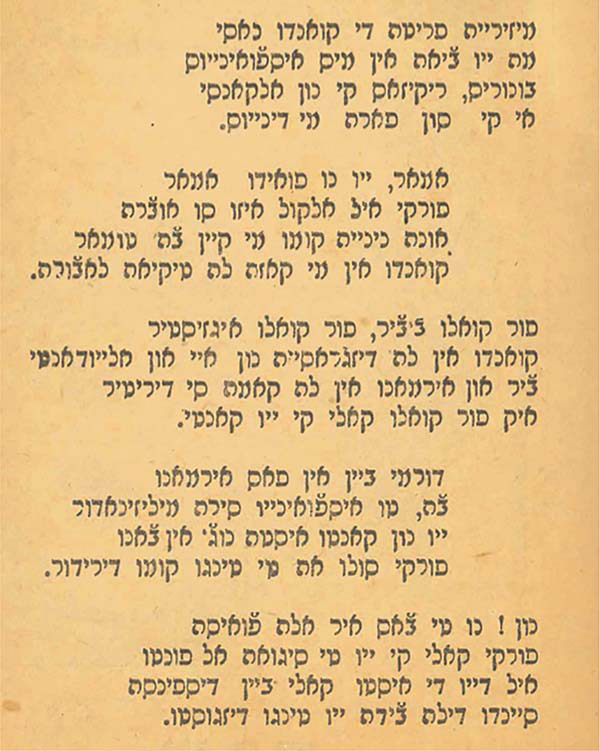

The excerpts featured in this volume depict the death of Sara’s brother and the repeated abuse she faces from her father, an unemployed alcoholic. As she cares for her brother on his deathbed, Sara expresses her anguish in a touching poem, full of pathos, that captures her loneliness and despair. The use of poetry to address everyday occurrences and concerns were very common and appeared often in the Ladino press. Amplifying the voice of the individual, such poems employed structures and themes of traditional Sephardic songs to portray contemporary issues such as military conscription, emigration, economic hardship, and even things like the rise in coffee prices.2 The use of this popular genre within the novel demonstrates the diverse nature of Ladino literary culture and the multitude of forms used by Ladino speakers to express their experiences and especially the hardships they endured in the twentieth century.

The novel’s hair-raising account of depravity, violence, extreme poverty, and disease serves its educational purpose, as it proclaims on the title page that “in this novel our readers will see and judge the consequences of alcohol.” In this regard, it partakes in the long tradition of educational writing in Ladino, which was especially common in newspapers and magazines that sought to eradicate behaviors such as drinking and gambling as well as to educate readers on a wide range of issues, from moral etiquette and child-rearing to nutrition, fashion, and hygiene.3 By employing fiction to edify and inculcate the masses, the novel also aligns itself with the broader tradition of the Haskalah, the Jewish Enlightenment movement, that spear-headed the emergence of modern Jewish literature with the explicit aim of modernizing and rectifying Jewish customs and behaviors.

Rotten Society can be perceived as evidence of the narrative of decline that often governs historical accounts of Salonika’s Jewish community. This narrative begins with the wealthy, robust society that emerged in the city after the resettlement of Jewish refugees from Spain and ends with the murder of most of its inhabitants in the Second World War. But it can also be seen as an example of the diverse literary corpus that emerged in this city, one of the largest printing centers in the Jewish world. We can sense in it echoes of rabbinic musar (ethics) literature that flourished in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, alongside reverberations of European realism and especially French authors such as Eugène Sue, Victor Hugo, and Émile Zola, who were extremely popular in the Ottoman Empire. It is therefore a quintessentially Jewish and Ottoman work of literature, weaving traditional and Western European elements in an effort to address the turbulence experienced by a community in flux.

Translating Ladino is admittedly not my usual arena as a PhD student in mathematics. However, I had the opportunity to take a course on Ladino at the University of Michigan with Dr. Gabriel Mordoch, which led me to this project. Given that Ladino is derived from medieval Spanish, I was able to build on my knowledge of Spanish while also picking up new vocabulary from other languages along the way. I greatly enjoyed working on this translation and hope to have done it justice.

From Rotten Society

1. “Una familia”

On a narrow street, where the smell of the water from the neighboring barracks was unbearable, where one could see the signs of dark misery, lived a family of two sons, a young daughter, and the head of the family—a widower.

The old courtyard where the barracks—or rather, these families—were stacked one on top of the other looks like a place where there is no shortage of cries. And, inside, there were so many noble souls, so many pious hearts, that although they didn’t have much, they wanted to help each other. The wretched poor pitied more those that suffered a little bit more than them.

And, it is in this moment that we see the neighborhood rush to help a young girl, with her hair undone, barefoot, and with torn clothes, who came out of the barracks followed by an old man who, trembling with rage, told her:

“Wretched, dirty girl! You’re going to tell me not to drink raki. I want to drink, look at what will take you from this world!”

And looking at the neighbors, he entered inside, murmuring, “Horrible people, ‘protecting’ me from raki!”

And the young girl was brought inside a barrack and sat down on a chair by some pious neighbors. As she was soothed and her clothes mended, she cried slowly to the quiet women.

At that moment, the older brother David—also brutalized by alcohol—came into the courtyard. Like his father, he was without work and dedicated himself to drinking, followed around by the police. He had no other comfort but drinking, making the life of the family hell. This afternoon, he ordered his sister to get up: “Ay! Sarika, why don’t you come get me something to eat, I want to lie down! Did you hear me or not?”

Reluctantly, the girl got up and went to the kitchen to make him food. While carrying the food, her younger brother Isaac came through the door. He was an intelligent young man, unlike his older brother. Having been in many gatherings, learning much about life, it was with disgust that he entered his house.

It wasn’t the misery that scared him, being that he had already suffered quite a lot. But the disgust that it provoked in him was caused by the sight of his big brother and his father. The moral authors of his mother’s death.

And if it weren’t for his little sister, young with blue eyes and a round face that was marked by cries and deprivation, he would have already abandoned this house, taken a chance, so that he no longer had to see the scenes that made him anxious.

Raising her eyes, Sarika noticed that her brother Isaac entered.

“Come in Isaac, you don’t want to eat?”

“No, little sister, I don’t feel like it.”

“You’re going to eat, I insist!”

“Look, you bastard,” the father jumps in, “she’s begging that he eats! First he has to bring money!”

[…]

“I don’t have any money because it’s not payday. If it’s for raki, I’m not going to give you money ever! Look at where raki brought you already; you were a lion, no one could put a foot in front of you, and now you’ve become a hunchback.”

“Me! A hunchback!”

And the father lifts the tin cup from the table, which he threw at Isaac.

“Ha! Ha!” David jumps up laughing, “have a good shower!”

He couldn’t see that it hit Isaac’s head and he fell, swimming in a pool of his blood.

Sarika ran to his aid. She called him, but he did not respond. Like a madwoman, she ran for help while the father and the son laughed indifferently.

For the second time, the neighbors rushed in, lifted the young man and put him in bed. They cleaned the blood and eventually he came to. He turned his glance to his sister. The girl was at his side, crying.

2. “Una muerte”

Autumn had passed and the rigorous winter, with all its evils, had returned for the families in the barracks, most of all for the poor ones.

In Sarika’s barrack, the darkest misery reigns. Because of a financial crisis, the principal winners ravaged the furniture, and what furniture: a dining table, an old sink, and a closet were all that could be found in the barrack.

The father, not finding anyone to drink with, drank with anyone who came around, and mostly with Sara. It was she who put up with everything, hiding from her brother Isaac the suffering that her father and brother David had caused her. After some time, David had committed a large robbery, fallen into the hands of the police, and been sentenced to six months in prison.

Isaac, weak, tired from wandering the streets without being able to find any work, arrived with a piece of bread in his pocket. The poor young man found himself in a miserable state, with torn clothes, without a coat, and had become so ill that it was a miracle he’d survived. But it left him weak, and, from a lack of care, he’d developed an issue with his lungs. Isaac hid all this from his sister, who already understood the sickness with which her brother was afflicted.

But what to do? What to do? The poor boy cursed society, the vices of men and most of all capital—capital that takes everything and doesn’t leave anything for the poor.

It was January, the month of harsh cold. The strong wind blew on the roofs of the barracks. The rain fell heavily, and there, in Sara’s barrack, young Isaac agonized. He’s nothing but a pile of bones perched on the sofa, covered by a quilt—which was only a quilt in name, so much of it was torn and filled with holes.

His sister Sarika, who sat next to him, couldn’t cry anymore. She watched her brother without stopping, attentive to all his gestures. Suddenly, the agonizing Isaac calls out:

“Sara!”

“What is it, Isaac?”

“How’s the weather outside? Rain, wind? Our barrack seems to be full of water!”

“No! Isaac! Sleep and get some rest!”

“Sleep! Eternal rest is already coming for me. Don’t cry, Sara, I don’t regret anything in life. Being that it was nothing but torment and suffering for me. I think of you, my dear sister. I don’t want to die so that I can protect you, alas! My strength has already escaped me.”

[…]

The air blew stronger and stronger, and the rain fell heavily. Sara’s father still hasn’t returned from the tavern. Isaac, having become tired, seemed to have fallen into a deep sleep, a sweet sleep … In his delirium he went on talking about his past, about dashed hopes and about his loves.

Suddenly, someone knocked on the door. Sara went to open it. It was the father, tripping from side to side, stumbling over everything on his way to the sofa where the sick man lay.

“He! The lazy one is already in the bed! Mister Isaac, you didn’t earn anything to bring something to eat?”

“You can’t eat seeing how he is, he’s going to die!”

“Die! And I’m dying to eat!”

“There isn’t anything!” she responds.

Lifting his hand he punched her and knocked her down. Crying, Sara got up and sat next to Isaac who was still asleep. Suddenly, hearing the sound of tin blown by the wind, Isaac woke up.

“Sara,” he called, “where are you? Tell me, has father come home? Tell him I forgave him, in the end he is my father, he’s the one who brought us into the world. Still, I can’t forgive the one in prison, my big brother … If the oldest of the family were less of an alcoholic, if he’d taken care of the family, our mother would still be alive, and we wouldn’t have suffered so much. Ah! What cursed society! Are they cursed? Those people who brought us here? Are those who don’t allow us to earn our bread through the sweat of our forehead? No! No! Better to stay quiet, to leave without worrying too much about death, about eternal sleep, and to free myself from this weight.”

“Don’t talk like that, my dear. Don’t talk too much, it will make you tired, and you’re so weak!”

“But why shouldn’t I talk, sister? Look! It’s the end! When my eyes close forever, I won’t speak anymore. Why shouldn’t I say now what I think of this cursed society?”

And he fell back against the headrest with a cough that pulled on his insides. Sara got up, crying, and began to sing:

Dark misery since I was born, But I saw in my dream, Good fortunes, riches that I didn’t reach, And that are denied to me.

To love, I cannot love, Because alcohol did its work, Who will take a girl like me, When in my house consumption reigns.

For what to live, for what to endure, When in disgrace there is no succor, To see a brother dissolve in bed, That is why I sing.

Sleep well in peace, brother, Go, your sleep will be curative, I sing not in vain tonight, Because I only have you around me.

No! You’re not going to the grave, Because I must follow you to the moment, God must give this well, Since for this life I have disgust.

As she sang, the rain fell suddenly in a flood; the father, with his hoarse voice, yelled from the bed, “Sara! Come look over here! Is water leaking?”

“I can’t. You look.”

In that moment, the tempest howled in all its fury. Tin pieces of the roof lifted and flew away like pieces of paper. In the courtyard, the rain was stronger. It fell heavily. Inside the barrack it looked like the sea, full of water. Suddenly, the sick man jumped up crying, “What is happening? Why is the water running? Ah! My god, I’m cold! I’m trembling! Sara … Goodbye my dear sister …”

And he fell, breathless, onto the sofa while the rain continued to fall on him, until Sara covered him with her body. In the terrible night, Sara’s moans could be heard through the commotion of the wind. The neighbors didn’t suspect anything. And her father slept, unaware of the water that dripped all over him. With a startle, Sara found herself close to the bed where her cursed father slept:

“Get up, wretched father! Get up and see your son in bed! Get up and see who an hour ago you called lazy!”

“What are you saying?” he asked, rubbing his eyes.

“I mean that my brother died!”

The drunk father got up and looked at his son without shedding a tear and sat in a corner of the barrack. One could only hear the young girl crying bitterly for her brother. And thus passed the night, the terrible night, and in the morning the neighbors were astonished to hear about Isaac’s death.

3. “Sola en la vida”

The neighbors were astonished to hear of Isaac’s death. They didn’t believe that in a short time, a young man would leave for eternal rest, having only his little sister to cry for him.

The father stayed in the corner with a bottle of raki in his hand, casting his gaze everywhere and pausing over the dead body of his young son. It was already ten in the morning and there was no one to do the necessary procedures to take the dead man to his last resting place.

Sarika didn’t cry anymore, and it was an unemployed neighbor who took on this duty, seeing that there was no one else. Sara’s relatives came. Which relatives were those? An old woman and a distant relative and no one else. The mortuary, with its stillness of death, seemed even more melancholy than death row. This sad scene continued until midday. The neighbors came and went, with nothing to say or do but to pity the poor girl. Although she still had her father and brother, she was alone in life. It was four o’clock when time came for the bathing of the dead man. They toiled over the body. The carriage came. Isaac was put inside and, with the hurry that a child is usually carried, went on its way.

Who accompanied this young soul to its final resting place? Only his father. The criminal who indirectly killed him. The rest—his acquaintances, his friends, those whom he had seen often—had forgotten him. In this rotten society, it’s a habit to abandon the unfortunate, but when they succeed, their friendships are desired. There was no honor to be found here but that of the neighbors and the cries of the sister.

Passing through the Vardar district and the Teneke Maale, people expressed sorrow when they saw the carriage of the dead man. The cantor, instead of riding in front, didn’t wait more than one or two streets before he got up and sat next to the driver, giving the appearance of a carriage carrying cargo when it entered the cemetery.

The victim of society didn’t have anyone who would shed a tear over his grave, since his father, who mistreated him, did not make the effort to come.

Sara was crying at home and thought of what her life would be now. She knew what was waiting for her.

Meanwhile, the night passed. A sympathetic neighbor had made them some pastries.

And so, father and daughter slept that night and dreamt onerous dreams. In the morning, Sara’s father went out and came in falling over at midday. He didn’t bother to sit shiva.

Notes

- Naar, “‘Mother of Israel.’” ⮭

- Weich-Shahak, “Shire aktu’alia be-ladino.” ⮭

- Stein, Making Jews Modern, 124–147. ⮭

Works Cited

Naar, Devin E. “The ‘Mother of Israel’ or the ‘Sephardi Metropolis’? Sephardim, Ashkenazim, and Romaniotes in Salonica.” Jewish Social Studies: History, Culture, Society 22, no. 1 (Fall 2016): 81–129.

Stein, Sarah Abrevaya. Making Jews Modern: The Yiddish and Ladino Press in the Russian and Ottoman Empires. Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 2004.

Weich-Shahak, Shoshana. “Shire aktu’alia be-ladino.” Ladinar 2 (2001): 95–120.