As news of anti-Asian violence circulates in the 2020s, many cite the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II as evidence of the ways that the racism endured by Asian Americans is historic and systemic. While educating the general public about the injustices of wartime incarceration continues to be of significance,1 the mere signaling of the experience as proof of Asian American resilience does little to recognize the complex and nuanced ways Japanese Americans not only endured the trauma of World War II (WWII) but expressed dissent and resistance. In the face of forced removal, detention, incarceration, and resettlement, Japanese Americans enacted subtle and explicit forms of protest. Four individuals took their cases to the Supreme Court;2 inmates in incarceration facilities staged protests to improve wages and working and living conditions; and many fought against the violence perpetrated by prison guards. Many young nisei (second-generation) men questioned the draft,3 and by 1943 Japanese Americans were engaging in informal discussions about the illegality of incarceration and exploring the restoration of their rights.4

To explore another method of dissent, I take a performance studies lens to examine how the production of a parade offers room to enact a subtle form of protest. On July 4, 1942, a 22-year-old dancer named Yuriko Amemiya Kikuchi, who would later become a celebrated dancer with the Martha Graham Dance Company, wore a crown of gardenias on her head as she rode around a racetrack, formerly used for horse racing, in a convertible. Crowned the Victory Queen, Kikuchi was a featured figure in this festive parade at the Tulare Assembly Center, a temporary detention center housing Japanese American inmates during WWII. This scene of Japanese Americans celebrating Independence Day in the middle of the desert, among their temporary homes of converted horse stalls, raises the following questions: under conditions of disenfranchisement and uncertainty, why would inmates choose to celebrate Independence Day or feel the need to crown a Victory Queen? Who was victorious in this moment? In this essay I argue that the parade serves multiple functions: first as an exercise of nationalism and gender socialization, second as an attempt to reproduce pre-WWII life, and third as a deliberate act to reveal the limits of democracy by staging a subversive celebration of extraordinary patriotism in order to underscore the hypocrisy of incarceration. As participants in the parade, the inmates questioned the US government’s motivations for mass incarceration and brought into focus the injustice faced by their community at large.

Kikuchi was one of 120,000 other Japanese Americans who were incarcerated following the Japanese Navy’s attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, authorizing the formation of select military areas that could restrict and exclude any persons. This was followed by a civilian exclusion order by the Western Defense Command (WDC) that called for the specific removal of “all persons of Japanese ancestry.”5 Western Washington, Oregon, California, and southern Arizona were designated as military areas.6 Justified as a necessary means for national security, Japanese Americans were isolated and incarcerated in government-run facilities. Japanese American community leaders were the first to be arrested and removed from their homes, tearing families and communities apart. Japanese Americans were forced to suspend their education and careers and limit their involvement with social, cultural, and religious practices. Bank accounts were frozen, and generations of families were forced to sell or abandon homes, farmland, and businesses. Once served with an evacuation notice, people parted with personal belongings, friends, neighbors, and pets to temporarily relocate to remote areas with severe weather and dismal living conditions.

Only allowed to take what they could carry, individuals and families were instructed to assemble in a specific location, on a designated day and time. As large crowds gathered in transportation hubs, armed soldiers managed the space, giving everyone, from infants to the elderly, a number tag. Once accounted for, individuals and families stood in long lines, waiting for the next phase of directions. They boarded buses and trains, with the shades drawn closed, and rode for hours to an undisclosed location. Without any evidence of wrongdoing or criminal activity, Japanese Americans were gathered and tagged to be incarcerated en masse.

While the greater American public may have supported mass removal and incarceration following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Japanese Americans had been deemed a threat to the United States prior to the onset of war. As laborers from Asia, they were regarded as an economic and cultural threat since their entry into the United States in the late nineteenth century. After the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 created a labor shortage in agriculture, Japanese immigrants found success as tenant farmers in northern and central California. Their profitable farming methods were perceived as threatening to white agricultural business owners. As a result, the California legislature passed a series of Alien Land Laws in 1913 and 1920 to prevent “aliens ineligible for citizenship” from land ownership and long-term lease agreements. Similar to anti-Asian immigration policies of the late 1800s, these acts hindered many Japanese immigrants from owning property, establishing businesses, or cultivating a sense of belonging. The Supreme Court upheld these restrictions when the court case of Ozawa v. United States authorized governments to deny US citizenship to Japanese immigrants. As the successive passing of such anti-Asian legislation demonstrates, Japanese Americans were perceived as suspicious outsiders, unable to assimilate or be loyal. Such patterns, enacted by law and strengthened through social practices, set the stage for the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans following the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Kikuchi, like other Japanese Americans, was removed from her home in Los Angeles and taken to Tulare Assembly Center in the San Joaquin Valley. Assembly centers, or more accurately detention centers,7 were temporary camps where inmates lived in converted horse stalls or small barracks quickly constructed with tar paper roofs. The walls barely protected them from the natural elements, and the partitions between each unit did little to muffle the sound of neighbors. Public latrines and shower stalls had no doors, and people waited in long lines for meals and access to water. Barbed wire fences, guard towers, and armed soldiers surrounded the inmates. With the dry heat and the smell of manure lingering, inmates lived here until more permanent units could be built.

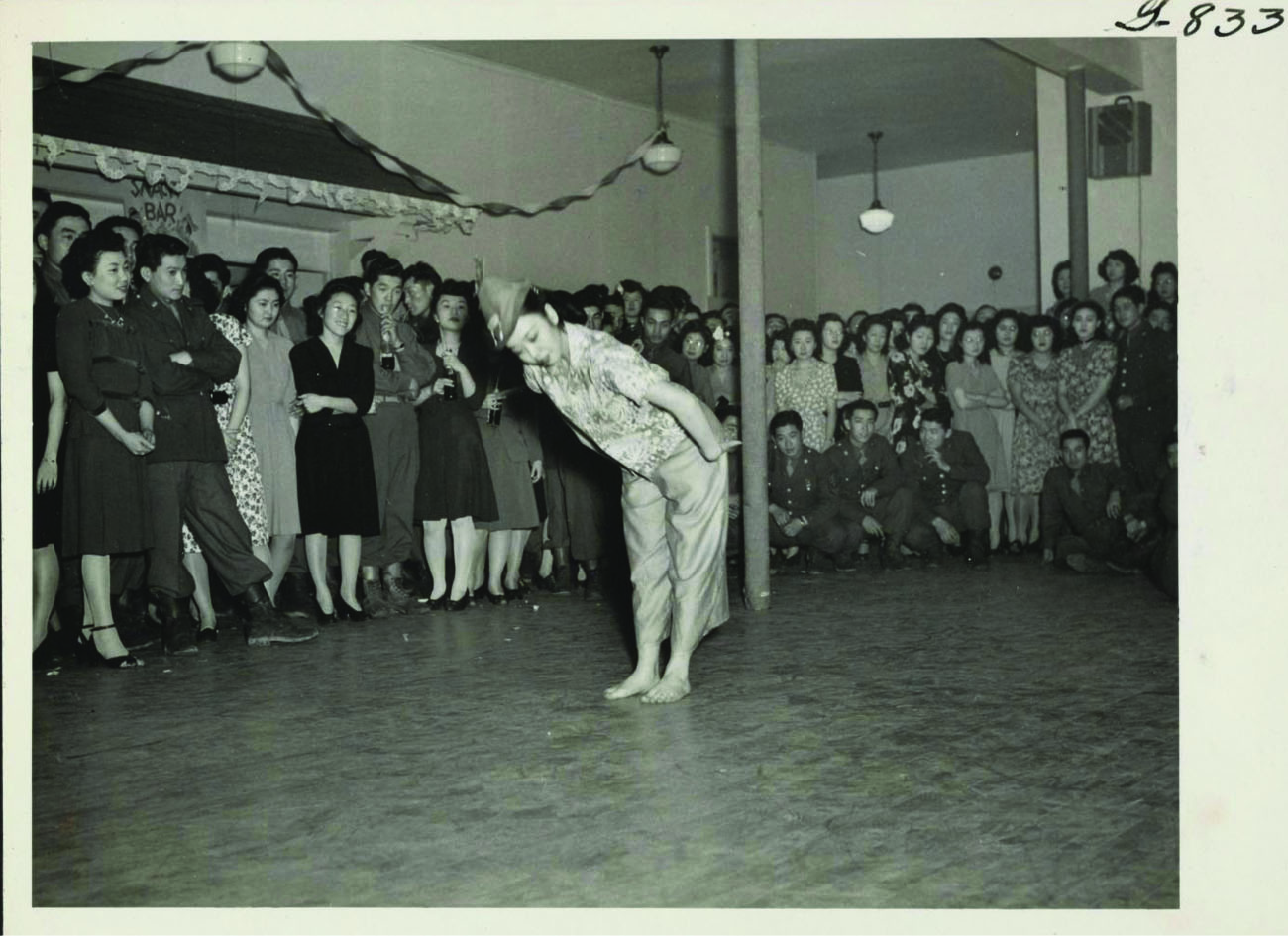

Despite these poor conditions, services were made available by the War Relocation Authority (WRA) to allow each center to operate like a small city. Managed by the state, schools, libraries, hospitals, fire and police departments, the postal service, and community newspapers were all established. The incarceration camps regularly hosted talent shows and social dances, as well as special events on holidays.

The Fourth of July parade in Tulare allowed some Japanese American inmates the opportunity to express their loyalty and prove their trustworthiness as citizens. This desire to demonstrate allegiance to the United States was felt long before WWII and heightened after their incarceration. As inmates, the desire to differentiate themselves from the Japanese enemy was clear, and some Japanese Americans worked hard to emphasize their fidelity to the nation and faithfully followed US government demands. Encouraged by white and Japanese American leaders, inmates studied and practiced ideals of Americanism. School curricula and adult education programs were developed to counter the assumption that Japanese Americans were unable to assimilate. Each morning after eating in mess halls, children attended school and most adults worked in low-wage labor funded by the US government. Children recited the Pledge of Allegiance, and many adults attended “Americanization classes” intended to teach aspects of American culture and the US legal system.8 War relocation center newsletters touted the importance of demonstrating loyalty to the United States and maintaining faith in the American way. The confinement center press often encouraged inmates to endure the crisis to be better Americans.

On the day of the Fourth of July parade, the Tulare News, the detention center’s community newspaper staffed by fellow inmates, prominently featured the Declaration of Independence on the cover, followed by a statement by conservative leaning National Japanese American Citizen Leagues’ (JACL) secretary Mike Masaoka. In the “Nisei Creed” Masaoka expressed his complete devotion to and faith in the nation, stating “I pledge myself to do honor to her at all times and in all places; to support her constitution; to obey her laws; to respect her flag.”9 With his unshakeable faith in the very government that incarcerated his family, Masaoka set the tone for the celebration.

The selection of a young woman to be the parade’s Victory Queen based on “beauty, character, and personality”10 added a gendered dimension to the patriotic celebration. Each of the contestants reflected “feminine” qualities valued by Japanese American leaders—they were meant to be young women who were educated, civic minded, and approachable by Japanese and white Americans alike.11 As a form of racialized gender socialization, these idealized characteristics were rewarded and reproduced through such social practices. As the winning queen, Kikuchi was recognized as a “well-known student of modern dancing,” and her practice was applauded as “advantageous to her in giving her natural poise and charm.”12 The judges emphasized her work ethic and commitment to teaching, commending her for designing and making her own costumes for her performances and listening to music constantly to select just the right accompaniment for her class.13 Highlighting their humility, productivity, and grace, the contestants reflected a Japanese American identity that was largely aligned with the hopes and dreams of any white, middle-class, all-American girl.

To encourage inmates to participate in the Queen’s selection, the Tulare News declared, “It’s an American privilege to vote. Elect your ‘Victory’ Queen at your Unit Headquarters.”14 The voting public identified 40 possible candidates, of whom ten were selected to be in the court and one to be the Victory Queen. The selected queen was a symbolic figure who held no decision-making power. With the coronation culminating on Independence Day, event organizers were able to conflate the inmates’ desire to celebrate their own standards of beauty and accomplishment with ideals of US democratic participation, which, of course, had been temporarily denied to Japanese Americans. A publicly recognized performer and teacher, Kikuchi was lauded for her schooling in Japan, balanced with her ability to excel in a distinctly American dance form. Kikuchi’s selection as the Victory Queen affirmed a collective (inmate) identity that agreed on an idealized feminine figure. Simultaneously, the incorporation of a ballot based voting process in the Fourth of July ceremony granted inmates the illusion of “freedom of choice” while also demonstrating the limits of American benevolence.15

As the Independence Day parade and Kikuchi’s coronation demonstrate, Japanese American inmates lived in an ambiguous space. Although of substandard quality, the government designed incarceration camps to meet very basic food and housing needs. Employment was available to those who were qualified for specific positions. Physical violence was not a constant threat, yet movement was limited and behaviors were highly monitored. In comparison to the atrocities experienced by ethnic and sexual minorities, and national “enemies” at the hands of the Axis Powers, Japanese Americans were treated with a greater degree of care toward their survival. However, WRA administrators closely regulated communication into and out of the detention center. Phone calls and telegrams were reserved only for emergencies, as determined by the welfare department.16 All packages sent were opened and inspected by the postal service.17 Even sanctioned events remained susceptible to further investigation. Personal choice was rarely exercised, as schedules were imposed not only for work and school life but also to manage the dissemination of shared resources, like food and water.

Yet, despite these conditions, inmates revealed the limits of such disciplinary mechanisms by appropriating their visibility as a method to draw attention to injustice. Performed in plain view, the elaborate patriotic Fourth of July parade and pageant exposed the painful irony of Japanese Americans pledging allegiance to a nation that incarcerated them without due process. As I show here, it is through an arguably exaggerated performance, pieced together with materials available, that inmates highlighted their ability to endure and even push back. Juxtaposing the pageantry and grandeur against the backdrop of the desolate detention center, participants and onlookers witnessed the perseverance of their ethnic community and found ways to navigate, and subvert, their status as inmates.

Although well documented in text, no images are available of the parade. I offer a composite description culled from the Tulare News. In the dry summer heat of the San Joaquin Valley, hundreds of inmates gather at the grandstand on the morning of Fourth of July, 1942. At the start of the ceremony, the Boy Scouts raise the American flag while playing “To the Colors.” The audience stand to face the flag and place their right hands over their hearts to recite the Pledge of Allegiance. Projecting his voice across the field, inmate John Fuyume continues the patriotic theme with a reading of the Declaration of Independence. Next, the audience raise their voices to sing “America,”18 to welcome the first group of parade participants. From the dusty field the Boy Scout Drum and Bugle Corp emerge, playing horns and beating drums. Then Japanese American war veterans, Tulare detention center administrators, and a man dressed like Uncle Sam greet the onlookers.19 Group after group, a stream of enthusiastic parade marchers pulling along floats made of office furniture follow, including mess hall workers, police officers, firefighters, hospital caretakers, athletes, newspaper reporters, club organizers, religious organization leaders, and finally the Victory Queen. When the dust clears, inmates participate in sports and games, from sumo wrestling, to tug-of-war, to a three-legged race, all taking place around the track and field area. Barracks close to the field feature art exhibits with paintings, needlepoint, woodcarvings, flower arrangements, and other crafts made by fellow inmates. The Fourth of July celebration culminates with a special dinner of boiled young hen with country-style noodles, mashed potatoes, garden spinach, and fresh ice-cold milk.20 The joyous day of celebration full of performances, games, and displays highlights the commitment of hundreds to plan, build, and execute an event worthy of taking place in any American town. Under the hot desert sun, however, the improvised floats, patchwork costumes, and music by the kitchen orchestra playing their vegetable peelers reveal the limits of this illusion and expose the effortful labor of inmates marching in a parade behind barbed wire.

Prior to the onset of war, urban Japanese Americans organized similar lively and extensive celebrations. In 1934, the first notable Japanese American festival, Nisei Week, took place in Los Angeles’ Little Tokyo neighborhood. Nisei Week hosted multiple events including a parade with floats and traditional Japanese folk dance, a tea ceremony, a baby contest, an essay contest, a fashion show, and a talent show.21 The first queen was inaugurated in 1935. Similar to Tulare, the public was able to vote for a queen using a ballot attained only after making a purchase at a Little Tokyo establishment.22

The desire to continue to organize such community rituals while incarcerated can be read as both a performance of patriotism and a critique. Perceivable as purely an exercise of nationalism and gender socialization, alternatively, the Tulare Fourth of July parade and coronation of a beauty queen also demonstrated a refusal by Japanese Americans to accept life as inmates. The parade, three-quarter miles in length, featured floats by 36 Tulare-affiliated groups. This elaborate and meticulously organized affair proved that Japanese Americans could be patriotic despite their incarceration. Simultaneously, this ironic production of abundance highlighted the inmate’s undeniable ability to endure hardship, be resourceful, and persevere despite living in dire conditions. With their patriotic zeal, Tulare inmates performed the paradox of their positionality as citizen and enemy.

This performance of patriotism by those deemed potential enemies also underscores the intangibility and fragility of citizenship. Scholar Anne Anlin Cheng’s reading of “Chop Suey,” a song and dance number praising the benefits of American citizenship in the 1961 film Flower Drum Song, provides a framework of analysis. In the musical number, the Asian American actors acknowledge the dish “Chop Suey” is an American invention, not “authentically” Chinese. They gleefully sing lyrics that are an amalgamation of American popular cultural references, while they skillfully and enthusiastically execute a square dance, a waltz, the cha-cha-cha, the Charleston, and several other Western dances. Cheng posits that the actors exaggerate their performance as happy consumers of American popular culture in order to present a more tolerable version of their identities and in doing so also hide their grief. She argues that the ensemble performed a “pathological euphoria,” a heightened expression of joy so great that no sign of pain or loss can be revealed.23 Knowing their rejection was inevitable, each minority figure must simultaneously deny their exclusion and hide their grief.24 With Cheng’s analytic we can see how in such a performance Asian Americans confront a paradox: in veiling their grief they both refute and uphold racism. Evoking a similar performance of pathological euphoria, Japanese Americans suppressed their grievances and enlisted the help of hundreds to produce a grand parade celebrating ideals of freedom and liberty. The exaggerated display of delight, however, merely masked and attempted to lessen the pain felt from their continual exclusion.25

By upholding specific racialized and gendered values, the selection of a queen at the Tulare Detention Center’s Fourth of July parade was not simply a lighthearted celebration. As reflected in the Tulare News, the event functioned to socialize women by rewarding ideals of Japanese American and white femininity, increase inmate morale with their participation in the selection process, and promote nationalism through a “gigantic and colossal”26 patriotic parade program, all practices occurring under the surveillance of the WRA. Challenging the bounds of these regulations, Japanese American inmates also appropriated acts of nation building. Through their celebration of the nation’s independence, inmates demonstrated that such independence was provisional to many, as no amount of patriotism could prove their innocence in wartime America. Incarcerated Japanese Americans could not make a claim to patriotism without recognizing their own status as citizens stripped of rights. With their embodied contradiction, as enemy and citizen, Japanese Americans articulated their attempts toward, and constant rejection from, full citizenship. As such, despite their abjection, through their self-produced Fourth of July festivities, Japanese American inmates exposed the very construction of citizenship and underscored the injustice of their circumstance.

Notes

- On March 15, 2022, the House passed H.R. 1931- The Japanese American Confinement Education Act to increase the authorization of the Japanese American Confinement Sites (JACS) grant program that works to preserve sites of Japanese American wartime incarceration. Although the bill passed, 16 House Republicans voted against the legislation. ⮭

- For more on Supreme Court cases of Mitsuye Endo, Gordon Hirabayashi, Fred Korematsu, and Minoru Yaso, see Dale Minami, “Coram Nobis and Redress,” Japanese Americans: From Relocation to Redress, ed. Roger Daniels, Sandra C. Taylor, and Harry H. L. Kitano (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1986. Revised edition. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1991); Brian Niiya, “Coram Nobis Cases,” Densho Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Coram%20nobis%20cases (accessed July 21, 2022); Brian Niiya, “Mitsuye Endo,” Densho Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Mitsuye%20Endo, accessed July 21, 2022. ⮭

- For more on Japanese American Nisei conscientious objectors and draft resisters, see Eric L. Muller, Free to Die for Their Country: The Story of the Japanese American Draft Resisters in World War II (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003). ⮭

- For more on the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee see, Frank Abe. Conscience and the Constitution. DVD. Transit Media, 2011. Daniels, Roger, Gail M. Nomura, Takashi Fujitani, William Hohri, Frank S. Emi, Yosh Kuromiya, Arthur A. Hansen et al. A Matter of Conscience: Essays on the World War II Heart Mountain Draft Resistance Movement (Powell, WY: Western History Publications, 2002). ⮭

- Brian Niiya, “Civilian Exclusion Orders,” Densho Encyclopedia, http://encyclopedia.densho.org/Civilian%20exclusion%20orders/, accessed February 1, 2016). ⮭

- Although not in mass, Japanese Americans from Hawaii, Alaska, and several Latin Americans countries, were also removed from their homes. ⮭

- National Japanese Americans Citizens League Power of Words II Committee, “Power of Words Handbook: A Guide to Language about Japanese Americans in World War II: Understanding Euphemisms and Preferred Terminology,” 2020, https://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8kp888m/entire_text/. ⮭

- Yoon K. Pak, Wherever I Go, I Will Always Be a Loyal American: Schooling Seattle’s Japanese Americans During World War II (New York: Routledge, 2002). ⮭

- “Nisei Creed,” Tulare News (CA), July 4, 1942. ⮭

- “Rules of Victory Queen Contest,” Tulare News (CA), June 24, 1942. ⮭

- Lon Kurashige, Japanese American Celebration and Conflict: A History of Ethnic Identity and Festival in Los Angeles, 1934–1990 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), 56. ⮭

- “Introducing the Queen and Her Court,” Tulare News (CA), July 8, 1942. ⮭

- Ibid. ⮭

- “Column-torial,” Tulare News (CA), June 24, 1942. ⮭

- Inmates who were citizens of voting age were given the right to vote in local elections in the state of their prior residency. Absentee ballots were distributed in War Relocation Centers in the fall of 1942, however, there were many barriers to this process including a lack of access to information on the candidates and campaign issues, and suspicious of the citizenship status of voters with a Japanese last name. See Natasha Varner, “Japanese Americans incarcerated during World War II could still vote, kind of,” Public Radio International (PRI), October 20, 2016, https://www.pri.org/stories/2016-10-18/japanese-americans-incarcerated-during-world-war-ii-were-still-allowed- vote-kind. ⮭

- “Phone Calls for Emergency,” Tulare News (CA), July 18, 1942. ⮭

- “Post Office Reconstructed,” Tulare News (CA), July 11, 1942. ⮭

- “July Fourth Program,” Tulare News (CA), July 4, 1942. ⮭

- Ibid. ⮭

- Cold milk was a treat as milk was often served warm or room temperature. Milk was referenced by First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt when she visited Gila River in 1943. Charles Kikuchi documented in his JERS notes that Mrs. Roosevelt commented that the milk was sour. This was a subtle act of support for the inmates especially as the American public were led to believe inmates were being “coddled.” See Karen Leong, “Gila River,” Densho Encyclopedia, last modified August 20, 2015, https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Gila%20River/. ⮭

- Kurashige, Japanese American Celebration and Conflict, 42–62. ⮭

- Rebecca Chiyoko King-O’Riain, Pure Beauty: Judging Race in Japanese American Beauty Pageants (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006), 60. ⮭

- Anne Anlin Cheng, The Melancholy of Race: Psychoanalysis Assimilation, and Hidden Grief (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 42. Cheng’s central idea of racial melancholia, further underscores this point. Her analysis of melancholia accounts for the experiences of exclusion, invisibility and rejection endured by marginalized communities throughout American history. Cheng builds on Freud’s definition of melancholia, described as feeling loss so deep one is incapable of accepting substitution and as such exists in a constant state of self-impoverishment. Cheng reframes Freud’s definition and looks to acts of systematic and legislative exclusion that lead to feelings of loss. Cheng examines exclusion as not only an individual experience but also that of a collective. She draws on psychoanalysis to further discuss the pervasive process of internalization: consuming loss and later denying its eternal presence. Cheng asserts that the rhetoric of melancholia draws attention to the complicated and contradictory emotions embedded in experiencing loss and in doing so invites “disarticulated grief” to be heard (29). ⮭

- Cheng, The Melancholy of Race, 9. ⮭

- Joshua T. Chambers-Letson, A Race So Different: Performance and Law in Asian America (New York: New York University Press, 2013), 110.Performance studies scholar Joshua Takano Chambers-Letson reads the act of pledging allegiance to the flag in incarceration facilities as an “embodied ritual structured by a uniform choreography.” As described by a teacher in the Manzanar incarceration facility, school children stood and turned to an empty corner and pledged allegiance to a flag that was not there. The problem was resolved when a student suggested to draw a flag. Chambers-Letson articulates that the children “not only bolster the nation but also inadvertently reveal the horrifying nature of the camps as a place where the law exists only in a state of suspension.” ⮭

- “Flag Ceremony to Open Fiesta,” Tulare News (CA), June 27, 1942. ⮭

Author Biography

Mana Hayakawa (she/they) is a lecturer in Asian American studies, dance studies, and disability studies. Her research examines Asian American dance and performance of nonnormative bodies in the context of empire and shifting terms of race, gender, and citizenship. Her writing is included in the anthology Our Voices, Our Histories: Asian American and Pacific Islander Women (NYU Press, 2020). She is also a co-author of the Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Literature (2019). In her capacity as an educator and student affairs professional, she has worked at the University of California, Los Angeles, Stanford University, Pomona College, and the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Works Cited

Chambers-Letson, Joshua T. A Race so Different: Performance and Law in Asian American. New York: New York University Press, 2013.

Cheng, Anne A. The Melancholy of Race: Psychoanalysis Assimilation, and Hidden Grief. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

“Column-torial,” Tulare News (CA), June 24, 1942.

“Flag Ceremony to Open Fiesta,” Tulare News (CA), June 27, 1942.

“Introducing the Queen and Her Court,” Tulare News (CA), July 8, 1942.

“July Fourth Program,” Tulare News (CA), July 4, 1942.

King-O’Riain, Rebecca C. Pure Beauty: Judging Race in Japanese American Beauty Pageants. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006.

Kurashige, Lon. Japanese American Celebration and Conflict: A History of Ethnic Identity and Festival in Los Angeles, 1934–1990. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002.

Leong, Karen. “Gila River.” Densho Encyclopedia. Last modified August 20, 2015. https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Gila%20River/.https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Gila%20River/

National Japanese Americans Citizens League Power of Words II Committee. “Power of Words Handbook: A Guide to Language About Japanese Americans in World War II: Understanding Euphemisms and Preferred Terminology.” 2020. https://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8kp888m/entire_text/.https://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8kp888m/entire_text/

Niiya, Brian. “Civilian Exclusion Orders.” Densho Encyclopedia. Last modified February 1, 2016. http://encyclopedia.densho.org/Civilian%20exclusion%20orders/.http://encyclopedia.densho.org/Civilian%20exclusion%20orders/

“Nisei Creed.” Tulare News (CA), July 4, 1942.

Pak, Yoon K. Wherever I Go, I Will Always Be a Loyal American: Schooling Seattle’s Japanese Americans During World War II. New York: Routledge, 2002.

“Phone Calls for Emergency.” Tulare News (CA), July 18, 1942.

“Post Office Reconstructed,” Tulare News (CA), July 11, 1942.

“Rules of Victory Queen Contest,” Tulare News (CA), June 24, 1942.

Varner, Natasha. “Japanese Americans Incarcerated During World War II Could Still Vote, Kind of.” Public Radio International (PRI), October 20, 2016. https://theworld.org/stories/2016-10-18/japanese-americans-incarcerated-during-world-war-ii-were-still-allowed-vote-kind.https://theworld.org/stories/2016-10-18/japanese-americans-incarcerated-during-world-war-ii-were-still-allowed-vote-kind