Asian/American is another way to say distance

The distance the width of a (double) eyelid crease

The distance the length of a queue

The distance the height of my 5 foot 7 body

The distance the length of a cheongsam, a kimono, a hanbok, an áo dài

The distance the cadence of an “Aah So…”

The distance the width of my flat nose

The distance the force of a one-inch punch

The distance at least 6 feet

The distance the driving of the golden spike

The distance the width of a dance hall ticket

The distance the caliber of an M16 bullet

The distance the width of an atom

The distance the size of a microbe

All adding up

So I go to great lengths to bridge the distance of this distance to displace this (foreign) body always held at a distance because it is deemed too distant

7,512 miles across the Pacific Ocean. The distance between my father and myself in the living room as the “mày là con mất dạy” spills from my father’s mouth. The “Huy, don’t sit so close to the TV. You’ll ruin your eyes” coming from my mother’s mouth. The distance between the way my lovers saw me and the way I saw myself. The distance between me and the edges of my body whenever I feel small.

Asian/American

Is it only another way to say distance?

(Nguyen, Minority Without a Model, 2021)

My body remembers the first time the kids in my elementary school called me “flat nose.” My body remembers the sting of my father’s condescending words when he flew into fits of rage. My body remembers the many times throughout my life that I have felt invisible. All of these experiences contributed to a fractured sense of self, a feeling of distance, that was very much part of my Asian experience growing up. I still need reminders that these experiences were not my fault but rather the results of white supremacy, colonization, and intergenerational trauma.

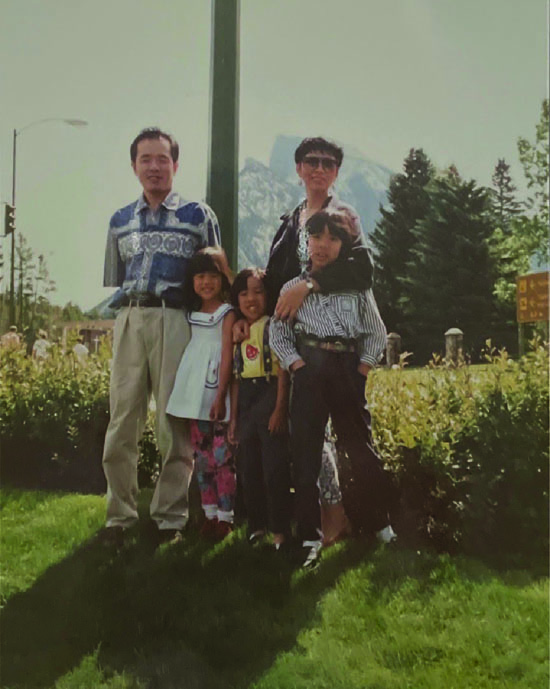

I am a second-generation Vietnamese American and a son of refugees. My parents are Mai Đỗ Nguyễn and Hùng Đúc Nguyễn. Dismemberment and separation are part of our history. The literal dismemberment of bodies like ours in the Vietnamese-American War. The forced separation of my parents from their homeland. The wounds in my family, born of intergenerational trauma. The splitting of tongues. The pressure to assimilate. The desire to be white.

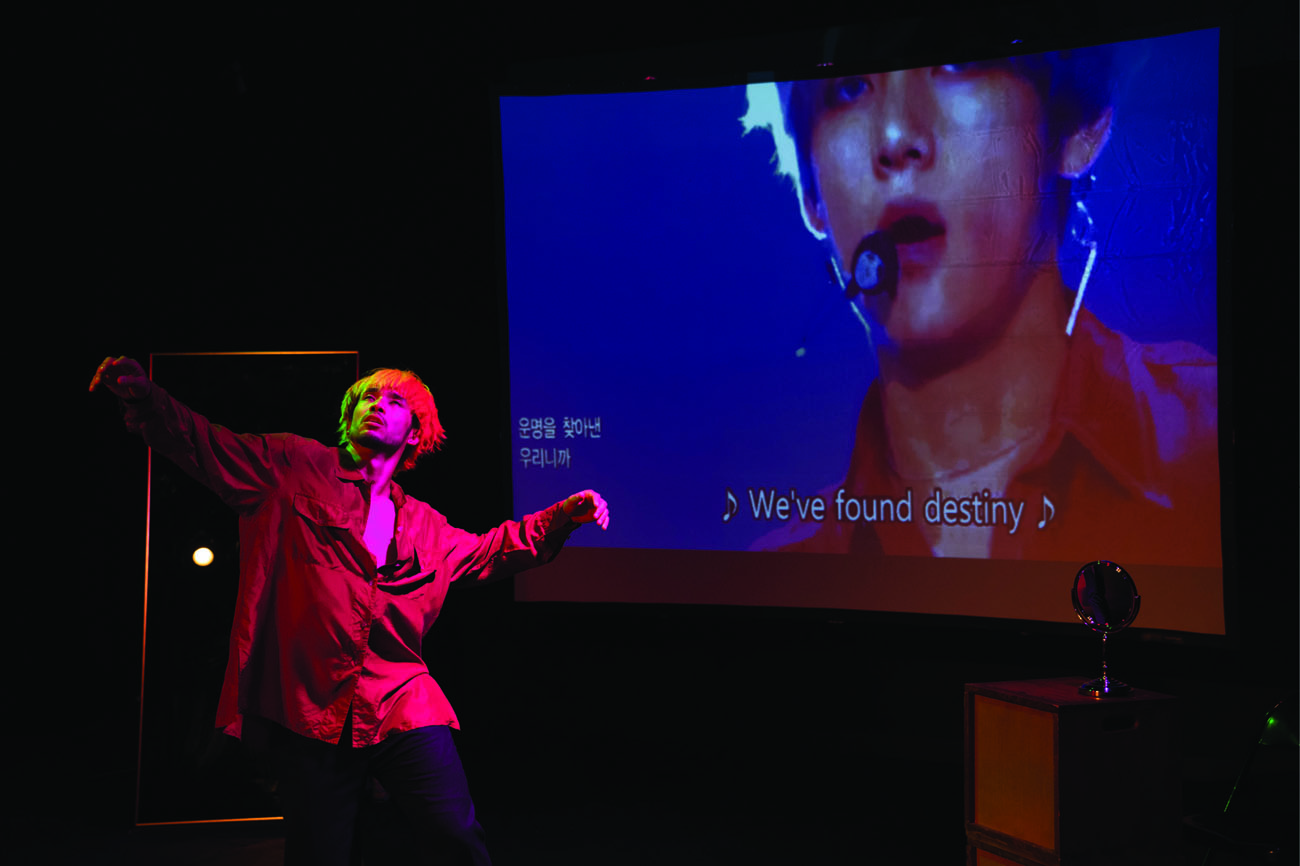

In recent years, I have been excavating the tender memories living within my body with the realization that healing does not lie in the forgetting or conquering of them, but rather the reintegration and recovery of these hurt parts of self, a re-membering. In my 2021 full-length dance theater work, Minority Without a Model, I explore the ways in which Asian emasculation, toxic masculinity, colonization, and the politics of desire live in my body. I navigate my lived experiences from childhood to now in a journey spanning Tinder, anime, Kpop, Batman, pro wrestling, protein, and pick-up artists to figure out who I’ve been and who I want to become. In the process of realizing the work, I was able to find forgiveness and compassion for myself. This was a process of embodied catharsis, and I was able to come into contact with the “flat-nosed” little boy inside me. I was able to hold him, and we reminded ourselves of who we really are at our core, beautiful beings worthy of love.

Within Native American spiritualities, it is believed that when you heal, you heal not only yourself but also seven generations backward and forward. Dance has been a way for me to heal, not just for myself, but for my family, my ancestors, and my community. Indeed, embodiment is not only a counter to dismemberment of the past and present but a way to create the future. The body is a record carrying the lifetimes and lineages of all we are connected to. It is a way for us to re-member so those who have come before are not forgotten.

As a child, I spent a lot of time with my bà ngoại and ông ngoại’s (maternal grandparents) place. We all lived in the same affordable housing complex. My immediate family lived in a townhouse and my grandparents, aunt, and uncle were in an apartment literally a two-minute walk away. My mom was the first in her family to come to Canada as a refugee, fleeing Vietnam alone at the age of 24. She brought the rest of her family over years later. One thing that stood out to me as a child was my bà ngoại’s altar. I would gaze upon the solemn faces in the black-and-white photos and was confused as to why my bà ngoại would leave oranges and burn funny smelling sticks (incense). It wasn’t until I was much older and when my bà ngoại passed that I truly understood what she was doing. I now have my own altar where a photo of her rests, and I make sure to offer her the most beautiful oranges out of the batch whenever I get them at the farmer’s market.

In 2019, I created an immersive altar and ritual performance installation, “SựHồi Tưởng,” for the annual Día de los Muertos exhibit at SOMArts. I was in deep reflection on my mother’s journey. What if she didn’t survive? Crammed under the deck of a small fishing bóat with 100 other people, she was stranded in the South China Sea for seven days when their engine stopped working. She thought she was going to die. A French trading vessel en route to the Philippines came across their boat and took them on board. It is a miracle that I’m alive. It is estimated that up to 400,000 Vietnamese lives were lost at sea fleeing Vietnam in the decade following the war. In living, I carry these lost lives and their legacy. I wanted to honor them.

For the installation, I worked with Giang Trịnh and with the help of some friends, we made 400,000 hand brushed strokes on a large canvas to be part of the altar. This was a small gesture for each life, taking a moment to honor one of the 400,000 with a physical act. The exhibition was up from October 12, 2019, to November 9, 2019. On each day the gallery was open, I gave my body as an offering through dance, movement as a ritual of remembrance. I was inspired by my bà ngoại and how she went to the temple every day for 100 consecutive days to honor my ông ngoại when he passed. This remembrance as action makes me think of how I experienced love from my parents. Love not as words but as action.

I remember wanting so much as a child, wanting to hear the words, “I love you” from my parents, just like the shows I watched on TV. It wasn’t until recent years that we’ve started saying, “I love you” and hugging, which were both things introduced by adult self to my parents. As an adult, I also now see the many ways my parents expressed their love through action. “Are you hungry?” might as well translate to “I love you.” Staying up late to make sure there was hot food for me when I came home even though they had work early in the morning. Waking up early to make my lunch. Not just a sandwich but a full meal with rice, vegetables, and protein.

These experiences inform my practice. For the altar, dance was an action to re-member the lineages that live within me. Moreover, it was an action to build a bridge of empathy with refugees worldwide, including those at our own country’s southern border, as an act of solidarity against the dismemberment due to forced displacement.

Recently, I was invited to be part of a panel at ODC in San Francisco in conversation with other Asian American dancers. In response to the question, “Can you share a personal experience of how your heritage shapes your art making?,” one of the panelists, Megan Lowe, who is a friend, peer, and collaborator, had this to say:

That last part really stuck with me. “To come in as a blank slate” is a sort of American ideal. To move forward without remembering the past, or rather, remembering a selective past. We see it in the renewed culture wars of today centering around critical race theory in schools. Apparently, looking back into history to see how events of yesterday have led to the inequities we see today is a divisive act. The operation of a white supremacist, patriarchal, capitalist society relies on cultural amnesia to keep itself going. This burying of histories of people of color is a form of dismemberment and again, dance is a strategy for re-membering.My cultural background, my identity, my mixed race—Chinese-Irish heritage. All of that feeds into everything that I am, everything that I do, and the art that I’m making, whether or not I am specifically setting out to explore those aspects of myself. I can’t separate them. It’s interesting, I’ve always had this problem going into different dance spaces or rehearsal processes or workshops, and they’re like, “Leave your stuff at the door, come in as a blank slate.” And I’m like, that’s kind of impossible, and that you’re even asking me to do that is kind of offensive. I am who I am today because of those experiences and they’re not going to separate from me.

(Megan Lowe, Art & Ideas, Feb 21, 2022)

Cultural amnesia comes in many forms and often, it may come with the best of intentions. I attended an art event last year that was meant to center the experiences of refugees. I was one of the few people of color in the audience and as part of her opening remarks, the white presenter had this to say:

COVID has made us aware of our interconnectedness and the arbitrariness of the lines that have historically divided us. The shared global experience of a virus has shaped us in such a way that perhaps we can all understand a bit of what it might feel like to be a refugee, even within our own communities.

(Redacted, Night Watch on the Bay, Fort Mason, 2021)

I can understand the intention, but these words were a spiritual bypass that expressed a false equivalency and co-opted my mother’s experiences. Moreover, it came literally days after Haitian refugees were whipped trying to enter the country by horse mounted border patrol agents. My peers and I wrote letters calling for accountability and repair, which received an initial response, but after we pushed for actual meaningful actions—namely reaching out to attendees of the event to acknowledge the false equivalency of the statement and asking that we not be burdened with having further conversation to educate them—we were met with silence. This incident motivated the creation of “We Live This,” a current work-in-progress with Hiê` n Hùynh that is slated for premiere at the Institute of Contemporary Art of San Francisco in 2023. It is our way of refusing to be silent-telling our stories with our own bodies on behalf of our families and lineages-not letting anyone else dare speak for us. Our bodies do not get to hide and so we reclaim the gaze of the other for ourselves and turn it back onto the one who is gazing, as an act of self-determination and re-membering who we are.

With the ongoing pandemic, our Asian communities are still faced with many challenges. We are both simultaneously invisible and hypervisible, model minority and perpetual foreigner, exoticized and reviled. Hybridity is a word often used to describe our lived experiences. As an Asian American and human being, I am in a lifelong process of liberation, integration, and healing. In sharing some of my experiences as an Asian American dancer within the lens of my artistic practice, I hope it provides you, the reader, with perspectives of value on embodiment as a healing practice with which to remember, reimagine, and reclaim who we are for the generations before us and the generations to come.

Dance, while recognized as an artform, is also an ancient somatic spiritual modality that has served humanity across cultures for centuries in understanding ourselves alongside our connections to one another and the world—seen and unseen—around us. With the cultural shifts we have seen in the past century in cultural consciousness and dialogue around intersectional identities, intergenerational trauma, and the dismantling of white supremacist, heteropatriarchal systems, dance can be a political and healing act for the marginalized body to declare its existence and demand visibility in its fullness. From this perspective, dance is a modality with which to re-member oneself, to reassemble the body and its interiority against colonial and imperial dis-memberment rooted in oppression and counter the culture of amnesia prevalent in the American consciousness. For Asian American bodies, these acts of dis-memberment are psychological, spiritual, physical, and intertwined—assimilation, exclusion, war, forced displacement, and most recently, COVID-19 pandemic hate crimes. Examining my lived experiences, my lineages, and my practice to date as a second-generation Vietnamese American multidisciplinary dance artist, I hope to contribute insight into dance as an intervention strategy against these historical and contemporary violences as a contribution to the existing and emergent discourse.

Author Biography

Johnny Huy Nguyen is a second-generation Vietnamese American multidisciplinary somatic artist based in Yelamu (a.k.a San Francisco) and son of courageous refugees. Fluent in multiple movement modalities including myriad street dance styles, contemporary, modern, and martial arts, Nguyen weaves together dance, theater, spoken word, ritual, installation, and performance art. In doing so, he creates immersive, time-based works that recognize the body’s power as a place of knowing, site of resistance, gateway to healing, and crucible for new futures. His most recent works are Minority Without a Model (solo, 2021) and HOME(in)STEAD (duet, 2022). In addition to his work as an individual artist, he is a member of Lenora Lee Dance and has also appeared in the works of KULARTS and the Global Street Dance Masquerade, to name a few. As an arts professional, he works as a development and program associate with Asian Improv aRts (AIR), helping to nurture the viability and sustainability of Asian American artists and organizations both locally and nationwide.