Ciudad-Real, V., Mwine-Chang, S., & Painter, G. (2023). Deploying social innovation models for anti-racist practices: Lessons from homelessness research in Los Angeles. Currents, (3)1.

Background: Racism and Homelessness

Racism is a primary driver of homelessness (National Alliance for Ending Homelessness, 2019; Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, 2018). Across the United States, Black Americans are more likely to experience homelessness than white Americans, and the Los Angeles region is no exception (National Alliance for Ending Homelessness, 2019). Over the last five years, Black people have made up 30% to 40% of the population experiencing homelessness in Los Angeles County despite accounting for only 9% of the population (Los Angeles Homeless Service Authority, 2022). As a result, the Los Angeles Homelessness Service Authority established an ad hoc committee on Black people experiencing homelessness to investigate these racial disparities and their root causes.

The committee concluded that these stark trends are the cumulative effect of systemic racism in the United States (Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, 2018). Decades of exclusionary housing and economic policies, along with disinvestment, have resulted in Black people experiencing homelessness disproportionately in Los Angeles County (Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, 2018). High rates of incarceration, poverty, unemployment, and contact with the foster care system have compounding impacts that have contributed to homelessness and housing instability (Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, 2018).

Even in best practice interventions for serving the unsheltered population like housing-first programs, retention rates differ across racial groups, resulting in Black single adults returning to homelessness at higher rates than white single adults (Homelessness Policy Research Institute, 2018). Black permanent supportive housing residents are 19% more likely to return to homelessness than white residents, even when accounting for factors such as demographics, service history, housing, and programs (Edwards et al., 2021). The same mixed methods study from the California Policy Lab concluded that housing discrimination, segregation, underinvestment, and lack of support contributed to Black people returning to homelessness after transitioning from permanent supportive housing (PSH) (Edwards et al., 2021). The study found that Black people experiencing homelessness had fewer housing options because of racial discrimination on behalf of landlords and even homeless service system staff (Edwards et al., 2021). As a result of housing placement in historically underinvested neighborhoods and racist bias on behalf of caseworkers, Black PSH recipients also reported a lack of safety in their neighborhoods once placed in PSH while also feeling like their placements limited their path to housing stability once they did reach important milestones in their treatment plans (Edwards et al., 2021). Additionally, high turnover among homelessness case workers made it difficult to provide continuity among those receiving services, which many Black PSH recipients claimed was already failing to adequately prepare residents for transition out of PSH units into non-PSH housing or the private housing market (Edwards et al., 2021).

Most policy approaches for addressing homelessness have been race neutral, making no distinction between how people of different races can be treated and are affected differently (Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, 2018). However, such approaches have not adequately addressed the impact of institutional barriers, incarceration, child welfare, affordable housing, and bias that primarily affect Black people experiencing homelessness (Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, 2018). An example of the shortcomings of color-blind policies includes the McKinney-Vento Act (MVA), which aimed to identify and support children who might be experiencing homelessness and not enrolled in school. While the MVA did provide increased access to mental health services and better shelters to people experiencing homelessness more broadly, it was indifferent in targeting Black people as a subpopulation and overlooked unique barriers they faced as a result of racial bias and systems. As a result, disparities persisted with Black people staying in shelters twice as long as white people (Roacha et al., 1996). Additionally, when combined with harmful stereotypes, issues that primarily affected Black people—including discriminatory practices in housing, discrimination, mass incarceration, and redlining—were left unresolved. These color-blind approaches can reinforce stereotypes and limit solutions by overlooking racism as a contributor to homelessness (Edwards, 2021). Further, Bonilla-Silva (2006) argues that societal color-blindness can mask persistent racial inequality.

Scholars have documented how the United States has turned to color-blindness to avoid discussing race but can still perpetuate racist inequalities (Bonilla-Silva, 2006; Edwards, 2021). However, color-blind policies more broadly have failed to acknowledge the ways in which racism operates at a systemic level and therefore requires explicitly anti-racist interventions (Kendi, 2019). As a result, recommendations by the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority have included deploying a “racial equity lens” in research, involving Black people experiencing homelessness and service providers in research design, and enhancing data collection for tracking progress (Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, 2018).

Anti-racism is defined as the opposite of racism, as it actively recognizes racism and seeks to undo inequities produced by it (Kendi, 2019). Adopting anti-racism is facilitated with a definition of equity that seeks not only equitable outcomes but also equitable processes to produce those outcomes (Race Forward, 2022). This means that beyond solely tracking results—including the voices of those who have been overlooked; in this case, Black, Indigenous, people of color (BIPOC), and those experiencing homelessness—should be accounted for and engaged in order to inform the interventions and processes and define the desired end-result. Given that our current systems and approaches have come short in achieving both equitable processes and outcomes, new models should be considered by policymakers and practitioners.

Social Innovation Primer

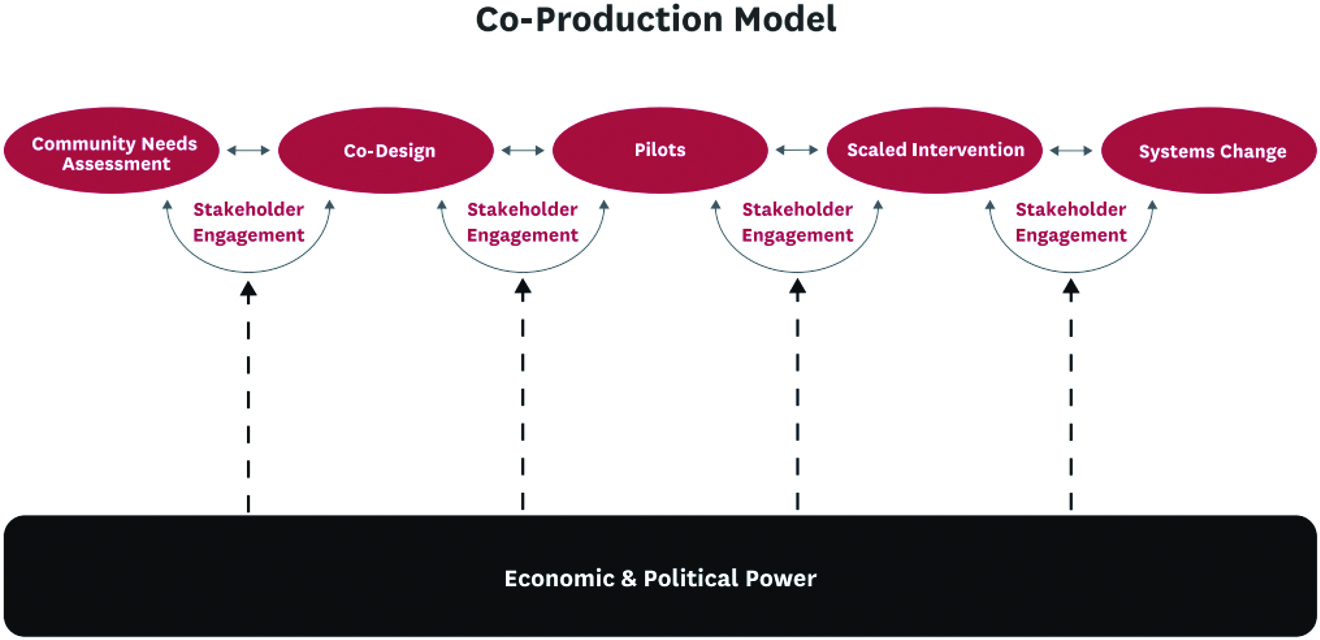

Social innovation (SI) offers frameworks for deploying anti-racist practices and facilitating equitable processes and outcomes. SI can be defined as “an iterative, inclusive process that intends to generate more effective and just solutions to solve complex social problems” (Beckman et al., 2020). Thereby, SI offers an alternative framework to standard policy approaches to address systemic issues. By providing the infrastructure for collaborative power-sharing, SI cultivates new ideas and refines solutions through the meaningful engagement of key stakeholders, including those who are primarily affected by the policy issue (see Figure 1).

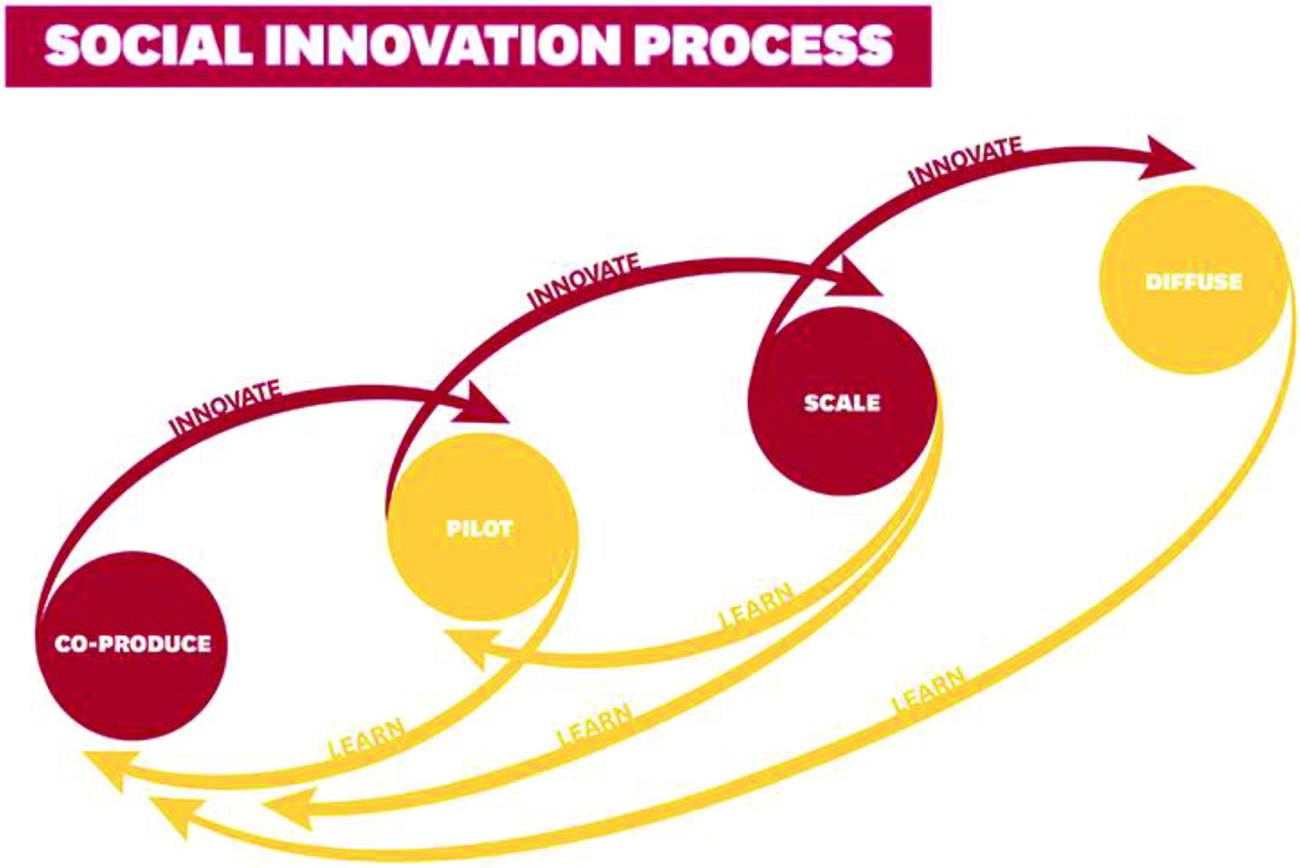

Social Innovation begins with coproduction, defined as “a co-constructed process to transform processes and outcomes toward more equitable power and resource distributions” (Rosen & Painter, 2019).1 Coproduction principles assert that expertise is found not just among those who traditionally hold power but primarily within those most affected by the problem itself. The relationship calls for shared power between all stakeholders, including policymakers, practitioners, funders, community members, and researchers, to adequately define problems and allow new solutions to emerge. After this initial phase, social innovation continues with the piloting phase where strategies are tested at a small scale and then scaled and implemented with more resources, and eventually the innovation is disseminated more widely. Between each phase, cocreation permeates the process, and iteration is required to refine innovations (see Figure 2).

These practices allow users to reflect on anti-racist principles and seek changes when they are not being met. The nature of SI lends itself to anti-racist processes and outcomes by making a concerted effort to bring in, collaborate, and cocreate solutions with community stakeholders. Under the SI framework, if the goal is to address racism and achieve equity, then BIPOC voices must not only be included but also valued for their expertise. The iterative nature of coproduction within SI permits anti-racist practices to be continuously refined, which is necessary given the stronghold of inequity perpetuated by the status quo. Iteration also provides opportunities for accountability by requiring interventions to be measured and reflected upon to ensure progress and document learnings. Similarly, pilots can be developed and tested among different target subpopulations. These principles provide a framework for organizations to attempt to develop, implement, and refine anti-racist interventions. It should be noted that bringing in marginalized voices can expose these members to more harm if done incorrectly, including retraumatization (Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, 2018). This is why many initiatives that solely invite diverse perspectives may not be successful in their anti-racist practice. Coproduction, on the other hand, requires that stakeholders share power and therefore rebalance existing inequality.

One model that can practice social innovation is collective impact (CI). CI, as defined by Kania and Kramer, is a “commitment of a group of important actions from different sectors to a common agenda for solving a specific problem” (2011, p. 36). Successful CI have the following key elements: a common agenda, a shared measurement system, mutually reinforcing activities, open and continuous communication, and a backbone organization. A common agenda ensures a clear vision and understanding among stakeholders to collaborate, and a shared measurement system helps the CI track its progress. Reinforcing activities provide the opportunity for the CI to leverage the expertise of its members without overburdening one member. Additionally, communication provides transparency and builds trust among the CI’s parties to further their unified goal. Finally, a backbone organization is critical for a CI’s function because it designates separate resources to undertake management and administrative responsibility to increase capacity among its members (see Figure 3).

With these components, CI initiatives are situated to holistically address intractable issues, such as homelessness. In particular, CIs can center equity if and when they ground the work in data and targeted approaches, focus on systems change in addition to programs and services, shift power, listen to and act with community, and build leadership and accountability (Williams, 2022). With these principles, SI provides a roadmap for groups to work together in meaningful and transformative ways, as well as creating and testing solutions.

Collective Impact for Homelessness Research and Solutions

In Los Angeles, social innovation has been deployed to address racism and homelessness through research and coproduction. The Price Center for Social Innovation launched the Homelessness Policy Research Institute (HPRI) in 2018 to bring researchers together in the Los Angeles region, along with policymakers, funders, and service organizations, to facilitate solutions to homelessness. Under the leadership of Dr. Gary Painter and Saba Mwine-Chang, as well as full-time staff, HPRI’s mission is “to accelerate equitable and culturally informed solutions to homelessness in Los Angeles County by advancing knowledge and fostering transformational partnerships between research, policy, and practice” (Homelessness Policy Research Institute, 2020, p. 11). As a collective impact network, HPRI’s model encourages cross-sectoral collaboration and deep partnership to holistically address homelessness (Price Center for Social Innovation, 2018; Kania & Kramer, 2011). HPRI’s activities include conducting and facilitating high-impact research, gathering and translating research for policy and practice, and convening and engaging stakeholders in the LA region and beyond. The following insights reflect the authors’ observations in supporting and leading HPRI through the spring of 2023.2

Since its launch, HPRI has grown to include over 100 researchers, policymakers, service providers, and experts with lived experience of homelessness, bringing together expertise across multiple disciplines and practices. The HPRI Race Equity Working Group was established in the spring of 2018 in recognition that effective research to end homelessness should acknowledge and prioritize the disproportionate impact of homelessness on BIPOC. In 2021, the work group became a committee, institutionalizing HPRI’s commitment to racial equity as a strategic priority and deeply held value. The primary purpose of the HPRI Race Equity Committee is to steward and codevelop equitable community-engaged approaches to research, policy, and practice.

The Race Equity Working Group—a cadre of Black and Brown researchers and practitioners—provided support to its members who wished to be part of a community or researchers committed to codevelopment of policy solutions to address the challenges identified by the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority’s Ad Hoc Report on Black People Experiencing Homelessness. The report issued provides 67 policy recommendations to meaningfully address Black homelessness in Los Angeles County and beyond. HPRI facilitated subsequent research on the development of unbiased homelessness triage tools and the retention of Black people in permanent supportive housing. HPRI’s current race-equity framework seeks to address internalized and interpersonal forms of white supremacy culture by developing (1) shared language, (2) shared history, and (3) culture-building. Shared language has been established in meetings and through trainings. Shared history has been created by providing trainings, workshops, and retreats for the HPRI network. Culture-building is created through shared trauma and informed care principles and reflected on at each convening, facilitating programing that includes multiple perspectives (lived experience and service providers).

The impact of the Race Equity Committee can be found not only in their influence in broader policy conversations but also within the organization itself. The HPRI research agenda—a coproduced, living document outlining regional research priorities—takes an active stance in adopting an anti-racist approach for future homelessness research and funding by centering racial equity throughout the four main research priorities (Homelessness Policy Research Institute, 2021). Under this commitment, HPRI at large promotes and practices coproducing with people with lived experience of homelessness and diverse researchers to inform homelessness policy, including new research committee members with lived experiences of homelessness. The committee also supports the research community by applying an equity focus to their work, advising and producing guidelines in a number of key areas, including engagement of people with lived expertise, language and methodologies for race-equity research, and implementation of key practices for addressing homelessness. Additionally, the culture of the Race Equity Committee has been disseminated across all HPRI convenings carrying out racially affirming, culturally and trauma-informed practices. This includes the adoption of a land acknowledgment, shared community agreements among members, and ensuring diverse voices in HPRI events.

Despite the creation of the Anti-Racism, Diversity, and Inclusion Initiative, a new county department dedicated to addressing race equity in our region, Los Angeles is now challenged by the deceleration of momentum in implementing measurable recommendations (Los Angeles County, 2022). HPRI currently measures its internal progress toward anti-racism through metrics such as convenings and membership. To promote accountability within homelessness policy, HPRI has committed to “co-defin[ing] the outcomes that would be needed for an anti-racist system” as well as interrogating existing data infrastructure (Homelessness Policy Research Institute, 2021). HPRI demonstrates how social-innovation tools can be used to systematically identify and address racism within the region’s most pressing policy issue.

Discussion: Lessons Learned from HPRI

The launch and administration of HPRI did not come without its challenges. As outlined in their second-year reflection report, despite its initial success, HPRI experienced rapid growth and resource competition, which required HPRI to address power and equity dynamics within the collaborative (Homelessness Policy Research Institute, 2020). HPRI’s commitment to the social-innovation principles of inclusion and iteration facilitated responsive anti-racist practices:

It transformed relationships by facilitating partnerships across sectors toward a common goal and nurturing existing ones. HPRI brings the research community studying homelessness together with funders, service providers, and people with lived experience to collectively discuss pressing research needs and inform current policies and on-the-ground practices. Similarly, researchers have a platform through the HPRI Research Committee to connect more frequently, which has enabled faculty members and consulting research firms to collaborate so new relationships form.

It has centered Black and Brown voices by fostering leadership and encouraging community engagement. As part of their commitment to equity, HPRI has earmarked resources to support the involvement of the Race Equity Committee cochairs, who also serve on the HPRI Steering Committee. The cochairs are people with expertise in racial equity and also hold marginalized racial identities themselves. By providing resources and a platform for leadership and convening, HPRI has not only centered underrepresented voices in its collaborative but also within the larger research community. The committee also includes service providers and lived experience committee members who advise on HPRI’s activities and research approaches. Lastly, HPRI as an organization is now coled by a Black managing director and white director institutionalizing Black leadership, modeling white allyship and exemplifying HPRI’s core value of collaboration.

It has redistributed power through coproduction. As a designated backbone organization with resources, HPRI is able to manage and move forward the collective’s work while also sharing power with its committee members. Through its various committees and with strategic advisement from the Steering Committee, decisions made by HPRI often take time but ensure that ownership of the organization is shared rather than through the top down. Such an approach is required for challenging the status quo through iterative learning for promoting new anti-racist practices.

We define and measure success to reflect on the collective’s direction. In addition to metrics such as attendance and convenings, which HPRI tracks to measure growth, the collective engaged in a yearlong strategic planning process to clearly cocreate goals and define the values the organization sought to achieve. An example of this includes the research agenda, which emerged as an activity from HPRI’s strategic planning session. The research agenda provides HPRI an opportunity to not only outline research priorities but also provides a guidepost to ensure there is progress made in each research priority.

Notes

- It is worth noting that the terms like coproduction, codesign, and cocreation are sometimes used interchangeably in the literature. In fact, coproduction can simply refer to the codelivery of services (Voorber et al., 2015), which is the antithesis of how coproduction is used here. ⮭

- Dr. Gary Painter has been HPRI’s director since its launch. Saba Mwine-Chang is HPRI’s inaugural managing director beginning in 2022. Prior to this role, she was a Race Equity Working Group cochair. Victoria Ciudad-Real served as a staff member who supported HPRI from 2019 to 2022. ⮭

References

Los Angeles County. (2022, July 1). About the L.A. County Anti-Racism, Diversity, and Inclusion Initiative. https://ceo.lacounty.gov/ardi/about/https://ceo.lacounty.gov/ardi/about/

Bonilla-Silva, E. (2006). Racism without racists: Color-blind racism and the persistence of racial inequality in the United States. Rowman & Littlefield.

Beckman, C., Painter, G., & Rosen, J. (2020). What is social innovation? USC Price Center for Social Innovation. https://socialinnovation.usc.edu/about-the-price-center/what-is-social-innovation/https://socialinnovation.usc.edu/about-the-price-center/what-is-social-innovation/

Collaboration for Impact. (2018). The Collective Impact Framework. https://collaborationforimpact.comhttps://collaborationforimpact.com

Edwards, E. (2021). Who are the homeless? Centering anti-Black racism and the consequences of colorblind homeless policies. Social Sciences, 10(9), 340.

Edwards, E., Milburn, N., Obermark, D., & Rountree, J. (2021). Inequity in the permanent supportive housing system in Los Angeles: Scale, scope and reasons for Black Residents’ returns to homelessness. California Policy Lab. https://www.capolicylab.org/inequity-in-the-psh-system-in-los-angeles/https://www.capolicylab.org/inequity-in-the-psh-system-in-los-angeles/

Kania, J., & Kramer, M. (2011). Collective impact. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 9(1), 36–41.

Kendi, I. X. (2019). How to be an antiracist. One world.

Homelessness Policy Research Institute. (2018). Homelessness interventions: Costs versus benefits. USC Price Center for Social Innovation. https://socialinnovation.usc.edu/homeless_research/2376/https://socialinnovation.usc.edu/homeless_research/2376/

Homelessness Policy Research Institute. (2020). HPRI year 2 reflection: Collective impact as a framework for collaborative homelessness research. USC Price Center for Social Innovation. https://socialinnovation.usc.edu/homeless_research/hpri-year-2-reflection-collective-impact-as-a-framework-for-collaborative-homelessness-research/https://socialinnovation.usc.edu/homeless_research/hpri-year-2-reflection-collective-impact-as-a-framework-for-collaborative-homelessness-research/

Homelessness Policy Research Institute. (2021). Moving toward an anti-racist system for ending and preventing homelessness in Los Angeles. USC Price Center for Social Innovation. https://socialinnovation.usc.edu/special-initiatives/homelessness-policy-research-institute/hpri-research-agenda/https://socialinnovation.usc.edu/special-initiatives/homelessness-policy-research-institute/hpri-research-agenda/

Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority. (2018). Report and recommendations of the Ad Hoc Committee on Black people experiencing homelessness. https://www.lahsa.org/news?article=436-lahsa-ad-hoc-committee-on-black-people-experiencing-homelessnesshttps://www.lahsa.org/news?article=436-lahsa-ad-hoc-committee-on-black-people-experiencing-homelessness

Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority. (2022). 2022 greater Los Angeles homeless count. https://www.lahsa.org/documents?id=6545-2022-greater-los-angeles-homeless-count-deckhttps://www.lahsa.org/documents?id=6545-2022-greater-los-angeles-homeless-count-deck

National Alliance to End Homelessness (2019). Demographic data project: Race, ethnicity, and homelessness. Homeless Research Institute, National Alliance to End Homelessness, https://endhomelessness.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/3rd-Demo-Brief-Race.pdf.https://endhomelessness.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/3rd-Demo-Brief-Race.pdf

Price Center for Social Innovation. (2018). What is collective impact? USC Price Center for Social Innovation. https://socialinnovation.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Collective-Impact-Handout.pdfhttps://socialinnovation.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Collective-Impact-Handout.pdf

Race Forward. (2022). What is racial equity? https://www.raceforward.org/about/what-is-racial-equityhttps://www.raceforward.org/about/what-is-racial-equity

Rocha, C., Johnson, A. K., Young McChesney, K., & Butterfield, W. H. (1996). Predictors of permanent housing for sheltered homeless families. Families in Society, 77(1), 50–57.

Rosen, J., & Painter, G. (2019). From citizen control to co-production: Moving beyond a linear conception of citizen participation. Journal of the American planning association, 85(3), 335–47.

Voorberg, W. H., Bekkers, V. J., & Tummers, L. G. (2015). A systematic review of co-creation and co-production: Embarking on the social innovation journey. Public management review, 17(9), 1333–57.

Williams, J. (2022, March 11). Core principles to support anti-racism in collective impact [Audio podcast episode]. Collective Impact Forum. https://collectiveimpactforum.org/resource/core-principles-to-support-anti-racism-in-collective-impact/https://collectiveimpactforum.org/resource/core-principles-to-support-anti-racism-in-collective-impact/