The recent success and legibility of South Korean Netflix dramas like Squid Game (오징어 게임)1 and All of Us Are Dead (지금 우리 학교는)2 have reinforced the position of Korean television drama serials (K-dramas) at the forefront of East Asian and global entertainment. Having offered Korean television shows to its US members since 2012,3 Netflix, the popular subscription video-on-demand (SVOD) over-the-top (OTT) streaming service, has enabled K-dramas to enjoy widespread circulation and recognition beyond East and Southeast Asia, where Korean entertainment has the advantage of cultural and geographical proximity. In recent years, Netflix has been expanding its collection of Taiwanese entertainment offerings, and this expansion includes Netflix-funded and distributed Taiwanese dramas like Light the Night (華燈初上)4 and The Victim’s Game (誰是被害者).5 Taiwan is a major consumer of South Korean entertainment and popular culture or Korean Wave (K-Wave or Hallyu) content,6 so much so that the K-Wave has been credited with improving diplomatic relations between Taiwan and South Korea after the latter broke off diplomatic relations with Taiwan in 1992 to establish diplomatic relations with mainland China.7 Considering the current dominance and popularity of K-dramas on Netflix, within Taiwan and around the world, Taiwan’s entertainment industry necessarily situates itself regionally, transnationally, and globally in relation to and in response to K-dramas’ dominance.

I argue that among these Netflix originals, the recently released television drama series Mom, Don’t Do That! (媽別鬧了, henceforth abbreviated as MDDT)8 is a key development in global Taiwanese television drama that strategically repositions Taiwanese dramas in relation to the popularity of K-dramas and the normalization of SVOD media-viewing cultures. Adapted from a Taiwanese bestselling novel,9 the narrative of MDDT may initially appear to be a straightforward family drama and comedy reflecting on the everyday domestic and relationship troubles of an elderly widow named Mei-mei and her two unmarried adult daughters named Ru-rong and Ruo-min. Having lost Chen Guang-hui, Mei-mei’s husband and the father of Ru-rong and Ruo-min, to a sudden heart attack five years prior, the three women of the Chen household continue to struggle to adapt to a life without their primary caregiver, companion, and mentor. Eager to remarry and desperate to marry off her two adult daughters, Mei-mei makes a bet with them to see who will get married first. Although this is MDDT’s deceptively simple and comedic premise, the production background of the Netflix original series already suggests that the seemingly lighthearted family drama might have more to offer than a casual viewer might expect. Backed by CJ E&M Hong Kong, the Southeast Asian headquarters of South Korea’s CJ Entertainment & Media,10 MDDT’s production background is suggestive of the inter-Asian and transnational dialogic ties and discursive connections being established between South Korean and Taiwanese entertainment industries. Enjoying the support of one of the largest and most prominent South Korean entertainment and mass-media companies, this easily negligible production detail complicates our understanding of global Taiwanese drama’s uneasy, but also undeniable, connections with South Korea’s entertainment industry. The respective globalizing pursuits and ambitions of Taiwan and South Korea’s entertainment industries have, in other words, resulted in a series of strategic media convergences and divergences between their industries.

I argue that MDDT may be read as a dramatized metacommentary that reflects on and responds to the global dominance and popularity of K-dramas and post-TV media-consumption cultures. MDDT does acknowledge both the popularity and success of South Korean entertainment and the enabling role of Netflix in facilitating South Korea’s and their own global production, circulation, and reception. Yet, it also offers commentary on the less desirable effects and implications of K-drama’s increasing visibility and popularity, as it is facilitated by SVOD media-consumption cultures. By strategically offering subtle commentaries on K-dramas and post-TV online media consumption within the narrative of an ostensibly Taiwanese drama, MDDT deftly renegotiates a position for global Taiwanese television drama, seeking to renew its relationship with its audience through its consistent evocations of transnational nostalgia. In doing so, the drama discreetly challenges the ubiquity of both K-dramas and Netflix, drawing attention to the latter’s curative influence and the prevailing effects such influence has on regional and global media-consumption cultures.

The Implied Authorial Audience: Recalling the Golden Era of Regional Taiwanese Dramas

The Taiwanese entertainment industry had been gaining its regional footing throughout the 1980s and 1990s, and its prime-time Hokkien-dialect (Minnan) television dramas and Mandarin idol-dramas were regionally popular in mainland China and Hong Kong, as well as in Southeast Asian countries like Malaysia and Singapore, throughout the 2000s. Minnan television dramas like Dragon Legend: Fei Lung (飛龍在天)11 and Mandarin idol-dramas like Meteor Garden (流星花園)12 and Autumn’s Concerto (下一站,幸福)13 had immense cultural influence and popularity in many parts of East Asia and Southeast Asia. The Taiwanese idol-drama adaptation of Meteor Garden, though originally inspired by a Japanese shōjo manga series,14 was so well-received that it went on to inspire a Japanese live-action series adaptation,15 a South Korean television series remake,16 and a mainland Chinese television series remake.17 This regional popularity of Taiwanese dramas in the 2000s—arguably a golden era of regional Taiwanese entertainment—coincided with and was subsequently disrupted by the parallel rising popularity of K-dramas, which continued to attract more viewership and accrue regional and global interest beyond the 2000s. This disruption has produced a palpable discontinuity or gap in the regional circulation and reception of Taiwanese dramas. Although Taiwanese dramas continue to be made, few dramas enjoy the enduring regional and international popularity and influence that Taiwanese television dramas in the 2000s did, and subtly calling attention to this discontinuity and reestablishing continuity today in the 2020s is what MDDT seeks to achieve.

References to the characteristic styles of both Minnan television dramas18 and Mandarin idol-dramas in MDDT encourage a transnational nostalgia toward Taiwanese dramas of the early 2000s. By strategically establishing continuities and discontinuities between the 2000s era of Taiwanese dramas in a contemporary Taiwanese drama, MDDT seeks to reconnect with its audience from the 2000s era, reminding them of the reasons they used to enjoy Taiwanese dramas. Self-referentiality or self-reflexive devices have been identified as characteristic of Taiwanese idol-dramas. As has been previously theorized in relation to Taiwanese idol-drama, the “use of self-reflexive gestures that foreground artifice in a highly mimetic genre … serve[s] as a form of covert communication between implied author and authorial audience.”19 Michelle Wang distinguishes the “implied author” of Taiwanese idol-dramas from “the real or flesh-and-blood author,” arguing that the implied author is “particularly useful in narrative genres like television drama serials, because these are not single-authored narratives but the synthesis of varied and multiple creative efforts on the parts of the director, screenwriter, actors and actresses.” Building off Wang’s identifying of an implied author in Taiwanese idol-dramas, I propose that in the case of MDDT, the implied author is the Taiwanese entertainment industry responding collectively to a post-TV entertainment industry dominated by K-Wave entertainment offerings. The implied authorial audience that this implied author self-reflexively reaches out to is one that is familiar with both Taiwanese dramas in the past as well as the popularity of K-dramas today, especially as they are both mediated through international entertainment circuits, online broadcast networks, and streaming services.

For instance, during a cab ride, Ru-rong—the stressed-out elder sister of the Chen family—starts to imagine her family members as stereotypical Minnan-speaking characters in a fictitious, melodramatic family drama titled The Sound of Mother’s Lament (阿母的靠北聲).20 Simulating an actual prime-time television drama playing on the small screen inside the cab and on a big outdoor screen that the cab passes, the stylized bright-red title is emblazoned on the top right-hand corner of the screen (see Figure 1), a characteristic visual format of Minnan television dramas.

Source: Screenshot from the Netflix drama series Mom, Don’t Do That! (媽,別鬧了!, 2022), episode 3

This flitting and humorous sequence in the drama’s representation of Ru-rong’s financial and familial predicament serves as a nostalgic reference to this regionally popular genre, strategically reminding its implied authorial audience of how it was considered prime-time entertainment that undeniably contributed to the Taiwanese or Chinese wave in the 2000s. MDDT also references the regionally popular Minnan television drama Dragon Legend: Fei Lung by having Ru-rong encounter her former ex-boyfriend, a minor character played by Nic Jiang.21 Since actress Alyssa Chia, who plays Ru-rong in MDDT, also plays Jiang’s love interest in Dragon Legend, this interdrama connection is a delightful Easter egg for those who recall and recognize this on-screen romantic couple from more than twenty years ago, at once attesting to Dragon Legend’s regional popularity and continued resonance. Jiang is not the only casting choice that reflects an intention to remind the implied audience of Taiwan’s golden era of television. Boasting a stellar and beloved cast of veteran and popular Taiwanese actors and actresses like Billie Wang, Shao-hua Lung, Alyssa Chia, and Kang-ren Wu, MDDT adopts and adapts beloved and memorable elements and characters from its Minnan melodramatic family dramas and Mandarin romantic idol-dramas.22 These adaptations strategically remind the audience of their relationship with Taiwanese entertainment, rewarding them for recalling these previously popular Taiwanese television genres and household names. The use of self-reflexive devices in MDDT thus reminds the audience of both Minnan family melodramas and Mandarin idol-dramas, representing an amalgamation of the two popular Taiwanese television drama genres of the 2000s that is likely to evoke nostalgic reactions. At the same time, through these strategic borrowings, MDDT establishes itself as a new, hybrid genre of versatile global Taiwanese television drama that seeks to renew its relationship with the former audience of both Taiwanese Minnan television dramas and Mandarin idol-dramas.

The Spatial Relegation of Traditional Television to Nostalgic Clutter

It is within this hybrid genre of versatile global Taiwanese television drama that MDDT boldly stages television’s obsolescence as a crucial subtext to the online dating platforms that Mei-mei uses, and this staging of television’s obsolescence is also meant to evoke transnational nostalgia, which characterizes the domestic and emotional landscapes of the Chen household. When younger sister Ruo-min moves back home after catching her boyfriend Cha cheating on her, she is exasperated to discover that her mother and older sister have filled her room with numerous boxes of clutter in her absence, treating her room like their own storage facility23 (see Figure 2).

Source: Screenshot from the Netflix drama series Mom, Don’t Do That! (媽,別鬧了!, 2022), episode 1

This all-too-familiar and deceptively simple domestic scenario and premise at the start of MDDT motivates the many recurring scenes of the family packing and sorting through boxes throughout the course of the drama. In the process, the family discovers long-forgotten photographs, the personal diary of the late Guang-hui, an old tape recorder, and cassette tapes of popular Taiwanese music in the late ’80s and early ’90s.24 These scenes of the family rifling through nostalgic clutter sets the stage for other forms of nostalgia to be exhibited and revisited regularly throughout the television series, whether in the form of the household’s memorabilia or past experiences that they miss. While the characters of MDDT do not ever openly comment on the role of the television in the household, the on-screen placement of the traditional television set in the Chen family living room is strategic and represents the gradual obsolescence of the shared, domestic media-viewing experience, as it is affected by SVOD platforms and other personalized, small-screen entertainment.

While Reed Hastings, the cofounder of Netflix, has proclaimed that they offer a “decentralized network” that “break[s] down barriers [so] the world’s best storytellers can reach audiences all over the world,”26 Netflix’s decentralizing impact on the domestic media-viewing experience encourages the putting-up, rather than the breaking-down, of barriers. While it may be true that Netflix enables narratives to circulate beyond immediate geographical and cultural contexts, these platforms and the media consumption practices they encourage have also redrawn domestic and interpersonal borders along post-TV lines, a phenomenon that MDDT self-reflexively draws attention to. MDDT depicts the evolving role of the television screen in the domestic space and how this, in turn, alters familial interactions and interpersonal relationships. The gradual obsolescence of the domestic, shared television screen and its decentralized role in the household is self-reflexively portrayed throughout the duration of MDDT. In the Chen household, this television set is situated in the living room and is framed by a studio family portrait and a clock27 while the top of the television set itself is covered in commonplace commemorative objects. As is evident in Ruo-min’s return to the Chen household described earlier, the domestic space of the Chen household is filled with nostalgic clutter and like the symbolic, commemorative objects that surround the television set, the domestic, shared television screen of the Chen household has been relegated to the space of nostalgic clutter.

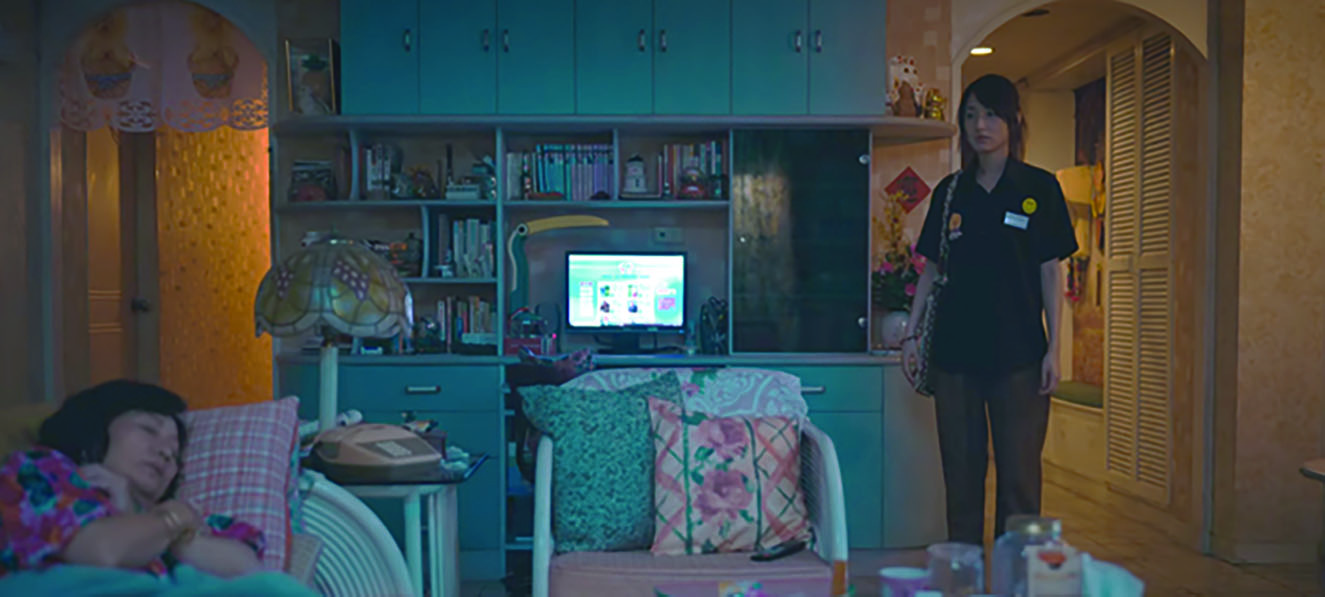

Rather than the all-too-familiar image of a family gathered around the television screen at the end of the day, the television screen of the Chen household is barely used throughout the series, and the family members spend most of their time relying on their personal desktops, laptops, and phone screens for entertainment. Ruo-min even returns home one day to find Mei-mei asleep on the couch with the television playing in the background,28 a heart-wrenching portrait of domestic loneliness (see Figure 3).

Source: Screenshot from the Netflix drama series Mom, Don’t Do That! (媽,別鬧了!, 2022), episode 1

Almost decorative, the domestic shared-screen’s decentralization and displacement in the living room is reiteratively represented by the camera angles throughout MDDT, which frequently privilege Mei-mei’s desktop computer, located to the left of the domestic shared screen (see Figure 4).

Source: Screenshot from the Netflix drama series Mom, Don’t Do That! (媽,別鬧了!, 2022), episode 1

When a wheelchair-bound Mei-mei makes numerous online impulse purchases while recovering from an injury, her purchases notably include a new Tatung flatscreen LED display television screen.30 This new purchase seems to briefly revitalize the domestic shared screen’s role in the household and Ruo-min and Cha are seen excitedly trying out the new television set.31 This revived enthusiasm is short-lived, and the symbolic death of the shared, domestic television screen is further represented when Mei-mei is subsequently forced by Ru-rong to return all her impulse purchases, including the newly bought television. Of all the purchases, it is this new flatscreen television that viewers witness Mei-mei having trouble parting with.33 A superficial assessment of Mei-mei’s reluctance might lead to the conclusion that she is merely unwilling to give in to her daughter’s interference in her purchases and unwilling to relinquish what little matriarchal and maternal control she has over her household. Yet, Mei-mei’s reluctance to part with the television set also represents a more profound and deeper refusal of the symbolic shift and transition from one viewing culture to the next.

The removal of the television set from its central position in the living room radically alters the orientation of domestic space. Even Mei-mei’s use of the computer in the shared living room is short-lived, and when Mei-mei is wheelchair-bound, she starts to use the computer located in her bedroom rather than the one in the living room.34 In the words of Ramon Lobato, “[The] internet distribution of television content changes the fundamental logics through which television travels, introducing new mobilities and immobilities into the system, adding another layer to the existing palimpsest of broadcast, cable, and satellite distribution.”35 Although Mei-mei’s temporary immobility is what prompts her to make this shift, the choice to depict this transition is also a symbolic representation of the ways personal, small screens have altered patterns of mobility and interactions within the domestic space. Mei-mei’s physical immobility compels her to try out the new mobility of online shopping, online chatting, and online and overseas dating, all from the convenience of her own bedroom. Even after she recovers, Mei-mei’s computer use happens exclusively in her bedroom, symbolizing her complete transition from predominantly occupying the shared domestic living space as the mother of the household to fashioning the private and personal space of her boudoir.36 In the imagined community of elderly online dating, Mei-mei is free to pursue the new love life she wants, yet this shift also alters the domestic and interpersonal boundaries and interactions of the Chen household. The effects of Netflix and other SVOD and OTT platforms and how they have radically decentralized domestic media-viewing and redrawn domestic and interpersonal borders become apparent.

While the domestic, shared television screen used to demarcate the media-viewing gathering site for a household, the removal or obsolescence of the television decentralizes, disrupts, and disperses social and domestic-viewing practices, redistributing media onto the various personal electronic devices of our characters. This dispersion, domestic reorientation, scattering, and redistribution of media-viewing centers of the household onto a bunch of smaller personal screens represent a shift from social and domestic viewing practices to more individual and private media-viewing habits. In the wake of Guang-hui’s passing, the Chen household must contend with the inevitable divergences in their respective lives and entertainment preferences. While Mei-mei is in her room chatting-up potential suitors online, Ru-rong is at the neighborhood convenience store working on her next novel on her laptop, and Ruo-min is in her room playing computer games.37 Like the sudden passing of Guang-hui, which the narrative trajectory and soundtrack of MDDT 38 encourages us to accept as an inevitable rite of passage that is no less heartbreaking as it is necessary, viewers are invited to consider the symbolic “death” of the domestic television screen as Guang-hui’s machine-parallel. Like the accommodating and tireless husband and father-figure that the Chen family finds difficult to move on from, the “passing” of the domestic television screen is an inevitable technological and entertainment rite of passage, a life-altering change we may grieve but must eventually come to terms with and move on from.

Ru-rong does eventually cave and viewers see her shopping online for a new flatscreen television for the family, carefully comparing the prices and specifications.39 However, in what is arguably the most peculiarly self-referential and metafictive scene that immediately follows the scene of Ru-rong making this new purchase, viewers see the three women sitting on the couch snacking happily while watching television together. When the camera turns to the screen to show us what they are watching and laughing about, the screen is self-referentially screening one of the first establishing scenes from MDDT when Ru-rong is arguing with the wife of one of her mother’s earlier suitors.40 At once spectral and specular, this new and surreal television screen in the Chen household projects the television series viewers are watching onto itself and within itself. This nested narrative effect draws viewers into closer proximity to the characters41 while also inviting viewers to reflect on their own evolving relationships with screens—both big and small, both shared and personal, and both old and new—and contemplate the corresponding changes in the domestic and social relations that are fostered around our media-viewing habits. Apart from the social and interpersonal changes that occur because of this media redistribution from one central and shared domestic screen to many small and personal screens, MDDT also invites viewers to contemplate how our media consumption habits and cultures have come to shape other aspects of our domestic and social life, specifically our food-consumption culture. In the same way that MDDT seeks to remind its authorial audience of the golden era of Taiwanese entertainment before K-drama’s disruption of its regional popularity, MDDT evokes transnational nostalgia by subtly relating its depiction of food, foodways, and food consumption to those typical of K-dramas. To understand how MDDT relates to K-drama depictions of food and food-consumption culture, it is important to contextualize and acknowledge the subtle shifts in the way K-dramas depict food and foodways.

What and How We Eat On-Screen: Media Consumption and Food Consumption Cultures

Media representations of food, foodways, and food-consumption culture have been an increasing interest among both food studies and media scholars. One contributing factor to this interest is the prevalence of food imagery in K-dramas, which has positively contributed to the global demand for Korean food exports.42 Internationally popular K-dramas like My Love from Another Star (별에서 온 그대),43 for instance, has been credited for popularizing Korean fried chicken, which is widely regarded as the new KFC that has superseded the popularity of the original Kentucky Fried Chicken.44 As early as 2003, Korean dramas like Jewel in the Palace (대장금)45 were already showcasing and dramatizing traditional Korean cuisine, emphasizing advanced culinary skill, culture, and aesthetics to its East and Southeast Asian viewers—the regional audience that responded well to the initial K-Wave. This media phenomenon is widely recognized among K-drama fanatics, many of whom are actively involved in online forums or discussions about food featured in K-dramas.46 Evidently, the relationship between South Korea’s food industry and its entertainment industry is a mutually supportive one, and while viewers tend to dislike conspicuous product placements, K-drama fans generally seem unperturbed and even actively seek out the products that are featured in their favorite dramas.

With fans dedicating so much time and effort to seek out the products they see depicted in their favorite K-dramas, the South Korean entertainment industry has begun to reflect on, tap into, and further develop this phenomenon in their recent dramas. Specifically, they have begun to unapologetically and boldly include tongue-in-cheek, self-reflexive gestures that comically and metafictively call attention to K-drama’s influential role in promoting and influencing global food consumption and food-consumption cultures, especially when it comes to the promotion of South Korean food and drinks. Rather than attempt to make their product placements more inconspicuous, K-dramas openly call attention to their many brands and product placements, even boldly featuring these brands and products in the television series that the K-drama characters themselves are watching.

In the recent K-drama Hi Bye, Mama! (하이바이, 마마!),47 Yu-ri, the female protagonist, is seen watching a fictional prime-time Korean television drama called Her Kimchi Water (그녀의 물김치) while enjoying cans of beer with her dinner. On Yu-ri’s screen, a man and woman are depicted enjoying a home-cooked meal, and viewers of Hi Bye, Mama! are thus treated to two instances of on-screen food consumption: Yu-ri eating her dinner with beer and the home-cooked meal that the characters are eating on Yu-ri’s television screen. The woman in Her Kimchi Water suddenly slams her pair of chopsticks down on the table and asks the male character if the food tastes a little too familiar to him. She then stands, delivers a loud slap to his face, and throws a big red tub of kimchi water at him. Hooked by this rapidly unfolding melodrama on her television screen, Yu-ri’s viewing pleasures are unfortunately frustrated when her husband’s new wife, Min-jung, switches the channel to the news broadcast instead.48 A subsequent drawn-out montage shows Yu-ri enjoying finger foods like fried chicken with beer while watching K-dramas. Viewers quickly realize that Yu-ri is reminiscing about the many times she enjoyed delicious food while watching her favorite dramas, an activity she misses now that she can no longer partake in such activities as a ghost roaming the mortal realm.

Another example of this is a running gag in the K-drama Business Proposal (사내맞선)49 involving Do-goo Kang, the grandfather of the male protagonist and a semiretired chairman of the Go Food company—an obvious reference to CJ CheilJedang, the prominent South Korean food company best known for the brand Bibigo. Kang, like Yu-ri, enjoys watching a fictional prime-time K-drama called Be Strong, Geum-hui (굳세어라 금희야)—another obvious reference to an earlier popular K-drama Be Strong, Geum-soon! (굳세어라 금순아)50—and many scenes in Business Proposal depict Kang watching this K-drama in his pajamas. In one scene, characters of Be Strong, Geum-hui have gathered in a pork cutlet shop to discuss the failing marriage proposal between the male protagonist and his wealthy potential in-laws—a common melodramatic scenario and dramatic trope. After the male protagonist confesses that he loves someone else—predictably a woman from much humbler origins and a more modest family background—his offended potential mother-in-law criticizes him for humiliating their daughter and slaps him across the face with a crispy pork cutlet from the table.51 This absurdly melodramatic exchange witnesses Kang covering his face in disapproval. Later in the same episode, he even self-reflexively comments on how these dramas always depict the wealthy as the drama’s villains, and he wonders if people really think all wealthy people behave this badly.

These scenes from recent K-dramas like Hi Bye, Mama! and Business Proposal, both notably available to watch on Netflix, signify an important but subtle shift in the way K-dramas depict food and food consumption. Bibigo’s logo, company, and food products are still prominently featured in many of Business Proposal’s episodes, but the focus is less on the eating of these food products themselves and more on the company’s corporate identity and ethos. The food products prominently featured and eaten in these scenes—fried chicken and canned beer in Hi Bye, Mama! and pork cutlet in Business Proposal—belong instead to fictional or unnamed brands and establishments. The beer that Yu-ri takes from her fridge all have their brand names facing the front, as if they belong to a strategic product placement, but “Clauster Beer,” supposedly a German beer brand, and “Wide Beer,” supposedly a brand producing grapefruit beer, are both fictional brands. Rather than feature real brands, these fictional brands promote the food item and influence when and how people consume such food. In other words, the Korean entertainment industry strategically promotes specific food preferences like chimaek—also known as the fried chicken and beer fever—and food-related consumer habits (e.g., indulging in chimaek while watching K-dramas). Consistently including scenes that depict characters of K-dramas watching K-dramas not only normalizes the watching of K-dramas, as if it is now an everyday activity that even K-dramas themselves cannot avoid depicting if they want to seem realistic, but also allows for self-reflexive meditations on filmic mediations themselves. These scenes depict a fictional televisual mediating of reality within the already mediated reality of the actual K-drama viewers are watching, creating a nested narrative structure of a television drama within a television drama.

Contrary to what one might assume to be a risky self-reflexive moment that might disrupt the viewers’ immersion in the drama’s reality and cause them to reflect on how these dramas discreetly seek to influence their consumer behavior, viewers seem to buy into such mediated and self-reflexive portrayals. Netizens on popular online South Korean entertainment forums like theqoo52 and dcinside53 started online threads that specifically mentioned the Her Kimchi Water scene in Hi Bye, Mama!, with a significant number of fellow netizens finding these forum threads and leaving comments about how funny that scene was.54 One of the anonymous netizens even commented that they immediately noticed the familiar Lock & Lock container55 for kimchi on the table, and it came to their mind that they would personally have poured out the kimchi water rather than have it continue sitting on the dining table. This thought made the subsequent throwing of the kimchi water on the man even funnier. These forum threads suggest that these self-reflexive scenes not only invite viewers to become more invested in the primary K-drama they are currently watching but also invite viewers to be invested in the secondary K-drama that the characters of the primary K-drama are watching. K-dramas have arguably paved the way for purposeful and economically productive on-screen representations of food in Asian dramas and have reaped the rewards of influencing food-consumption culture through their entertainment offerings. The popularity of these recent Easter eggs and their self-reflexive commentaries on brand endorsement, product placements, and media influence represent a significant shift in how K-dramas innovatively integrate product placements and advertisements into the narrative. These self-reflexive strategies and shifts in product-placement norms in K-dramas, in turn, influence how MDDT chooses to depict Taiwanese food and food-consumption culture.

While MDDT briefly features a few food and beverage brands throughout the series, such as the brief, recurring scenes in which Ruo-min works as a store manager at TKK Fried Chicken (頂呱呱)56 (a Taiwanese chain of fried chicken restaurants), the food at these stores are never prominently featured on-screen. Instead, two recurring food-related scenes in MDDT feature domestic food preparation and a relatively nondescript roadside food stall, foregrounding family-oriented, home-cooked food and centering local, small businesses instead of recognizable brands and large businesses. The late Guang-hui is known for his culinary expertise, and scenes of the family gathering around the table to enjoy his signature braised pork belly57 serve as wistful reminders of the domestic dinner table and the warmth of home-cooked meals. With the widow Mei-mei struggling to match her husband’s cooking prowess, the two daughters frequently complain about their mother’s strange and unpalatable culinary “experiments.”58 Another recurring food-related scene takes place at a thirty-five-year-old roadside food stall (see Figure 5), affectionately known only as Mr. Zuo’s Old Stall and referred to by the characters as “the old place” (老地方).60

Source: Screenshot from the Netflix drama series Mom, Don’t Do That! (媽,別鬧了!, 2022), episode 1

The Chen family is shown to frequent the stall, even before the passing of their Guang-hui, so much so that Zuo,61 the owner of this roadside food stall, knows them and knows their standard order of braised meat, dry noodles, and wonton soup by heart. MDDT romanticizes this food stall, indulging its viewers in the elaborate fantasy of nostalgic regularity, familiarity, domestic ritual, and impossible permanence. No matter which combination of characters patronizes this stall and no matter the time, they are always seated at the same table with the backlit painting of yellow poppies on the shutters behind them. No matter how often the interpersonal disputes and whims of the Chen family disrupt the dining experience of other patrons—Mei-mei takes a dish from another table without their permission to show some foreigners what they should order62—the other patrons are always kind enough to shrug these inconveniences off without kicking up a fuss. This on-screen portrayal of food, foodways, and food-consumption culture is at once distinct from and a part of the K-drama model.

MDDT implicitly suggests that the K-drama model of food consumption favors eating out, ordering in, eating alone, and bigger, well-established brands. Although it might appear as if MDDT is rejecting the K-drama model of representing food on-screen, these depictions of home-cooked food and roadside stalls still serve to promote Taiwanese food and local street-food consumption. Through the many recurring and romanticized depictions of home-cooked meals and Zuo’s roadside stall, MDDT reminds viewers of Taiwanese dramas and how their local food cultures used to dominate many of the screens in East and Southeast Asia, presenting yet another nostalgic reminder of a bygone era of regionally popular Taiwanese entertainment. Adopting and taking a leaf out of K-drama’s playbook, MDDT strategically imbues local dishes and food cultures with media, cultural, and affective significance. Since credit scenes on Netflix are often cut short by the automatic transition into the “Next Episode” or the automatic playing of trailers from Netflix’s entertainment recommendations, the format of the platform enables a strategic and convenient overlooking of the credits. This overlooking of the credits facilitates the discretion of the impressive range and number of sponsors and brands backing the production of this Taiwanese drama.63 Thus, MDDT’s response to the K-drama model of mediated food representation acknowledges the influence of this K-drama model while simultaneously drawing attention to how this model has altered viewers’ food consumption habits and preferences in ways that they might not have been aware of, such as in its subtle critique of mukbang.

MDDT critiques the K-drama model of representing food and food consumption culture in its depictions of the mukbang (먹방, eating broadcast) phenomenon64 and masculine cooking65—the former being a social media phenomenon that originated in South Korea and the latter being a well-established K-drama trope. Dashi Yaoji (大食妖姬)—the online handle of the young lady that vies with Ruo-min for Cha’s affection—is a popular livestreamer who films herself eating copious amounts of food. Like the many South Korean mukbang broadcast jockeys, Yaoji is pretty, young, and feminine, adopting a sweet and bubbly persona.66 Portraying her as a somewhat endearing villain who tricks Ruo-min into sponsoring her with TKK Fried Chicken for one of her livestream sessions, Yaoji’s on-screen personality belies her potential for vindictiveness and petty vengeance. If the home-cooked meals of the Chen family67 and Zuo’s roadside stall represent forgotten and underappreciated Taiwanese food cultures and sociality, the deluge of scathing, anonymous online comments that Yaoji’s mukbang livestreams receive is the cultural antithesis. Even as an angered Ruo-min spitefully forces Yaoji’s face into a pile of chicken wings and fries and pours a bottle of coke over her head on the livestream, Yaoji’s followers continue to leave comments, variously delighting in the spectacle, mocking Yaoji, and cynically asking if the conflict is staged.68 While K-dramas frequently have embedded mukbang-like sequences, such as the earlier scene described in Hi Bye, Mama! when Yu-ri is seen indulging in chimaek as she watches her K-dramas, these scenes are meant to induce food cravings and are not meant to critically reflect on the implications and effects of mukbang. By inserting a character like Yaoji as an on-screen embodiment of this phenomenon, MDDT foregrounds the negative effects of an individualistic, materialistic, overindulgent, and narcissistic food-consumption and media-consumption culture,69 problematizing how K-Wave content and OTT media-consumption culture have coproduced these negative outcomes. By the end of MDDT, Yaoji has given up on chasing Cha and is preparing to further her studies to become a primary school teacher,70 a fate that symbolizes the rehabilitative food-media relationship that MDDT indirectly offers to its viewers.

Reflecting on yet another K-drama trope of masculine cooking, MDDT’s characterization of the character Senior—the supposed love interest of Ru-rong—is yet another attempt to criticize the gendered media-food relationship that K-dramas have normalized. The K-drama trope of masculine cooking often features an attractive and financially successful man rolling up his sleeves to whip up delicious and professionally plated food that is then served to the lucky woman he is attracted to.71 Senior is an over-the-top representation of this K-drama archetype. Shortly after he runs into Ru-rong at the convenience store, Senior looks deeply into her eyes, shares that he is good at cooking, and invites her to his place so that he may prepare a meal for her.72 A smitten Ru-rong will eventually be seen visiting Senior’s home and delighting at the perfectly portioned and professional-looking meals he prepares for her.73 Senior, with his stylish bachelor pad, successful career, substantial wealth, and professional cooking standards74 checks all the boxes of a stereotypical male lead in a K-drama. The drama makes it abundantly clear that the character is meant to be interpreted in relation to this K-drama trope and archetype, and a Korean song plays in the background during a melodramatic rainfall scene between Ru-rong and Senior. Senior runs out in the rain to meet Ru-rong and the slightly off-key Korean song plays in the background as the usually glib Senior uncharacteristically stutters over what to say to Ru-rong.75 This parodic Korean song titled “Want Rock-Hard Pecs” (我的胸很硬) is composed and sung by Taiwanese lyricist Matthew Yen (嚴云農), who refers to this song as “the perverse Korean song from episode 7” (第七集的變態韓國歌) in an Instagram post promoting the MDDT television series.76 These metareflexive and self-referential commentaries in MDDT are akin to a long trail of breadcrumbs throughout the drama, casting doubt on Senior’s character and inviting viewers to laugh at how unrealistic and problematic this K-drama archetype is. Senior’s qualifications and mysterious charm à la Christian Grey barely disguise his possessiveness, his controlling personality, and his erratic outbursts, and viewers are encouraged to consider the possibility that he might be a psychopath and a serial killer.77 Only in episode 9 do the viewers learn that Senior has always been a figment of Ru-rong’s imagination, is merely a new character in the novel she is writing, and his appearance is inspired by a staff member working at the convenience store that Ru-rong often writes at. Senior, as an exaggerated portrayal of the typical K-drama male lead, becomes a strategic counterstereotype to the masculine domesticity that K-dramas have been centering and encouraging its viewers to fantasize about.

As a Taiwanese drama responding to K-dramas’ dominance, MDDT establishes this masculine stereotype as not just improbable and unrealistic but as laughably banal and inane as it is unhealthy and abusive. Rather than a paragon of progressive masculinity and eligibility, MDDT boldly recasts and problematizes the aspirational K-drama male archetype as a dysfunctional, dangerous, and morally depraved person whose traits should not inspire desire but instead serve as cautionary red flags. This huge narrative twist, if unanticipated by the viewer prior to episode 9, proves MDDT’s point that K-dramas have normalized this problematic archetype and romantic dynamic to the extent that we no longer even question the nature of this unlikely and untoward relationship. The breadcrumbs—or clues—scattered throughout the television drama’s duration are painstakingly apparent. Senior’s image has always been discreetly featured on all the covers of Ru-rong’s published romance novels.78 In another self-reflexive moment, Ru-rong dreamily talks about the good looks of Taiwanese actor Kang-ren Wu to convince Ruo-min to break up with her unfaithful boyfriend, naming the actual Taiwanese idol-drama actor who later plays the role of Senior in MDDT.79 When Ru-rong first meets Senior in the convenience store, she has also taken off her glasses and needs to squint to recognize him, a minor detail that is meant to foreshadow the metaphorical blindness of those who fail to recognize these apparent tells that would suggest Senior is not a reliable or real character.80 Mei-mei even foreshadows this twist when she tells Ru-rong that convenience stores will not provide her with the inspiration she needs to write a romance novel,81 further hinting at the lack of genuine romantic fulfilment between Ru-rong and Senior, whose relationship is ultimately confined to Ru-rong’s active writer’s imagination.

Conclusion: The Uncertain but Hopeful Horizons of Global Taiwanese Television Drama

By employing these self-reflexive devices as a means of establishing metadramatic continuity between Taiwanese drama-consumption cultures in the 2000s and this new Taiwanese Netflix original, MDDT invites its viewers to recognize and acknowledge their “shared sensibility,” “shared creative understanding,” and “shared worldview or outlook.”82 This shared experience does not exclusively pertain to the domestic, familial, romantic, or even cultural resonances but extends to their collective experience of the transformations in media-viewing habits and the dwindling regional popularity of Taiwanese dramas, as it is impacted by the popularity of K-dramas and changes in media-viewing cultures. Viewers may recognize how their media-consumption habits and preferences are complicit in enabling the normalization of certain dramatic tropes, media-viewing cultures, and media-influenced social relations, yet these media-consumption habits and preferences are simultaneously indispensable in remedying and revising the less desirable effects of such normalization.

The illusion that MDDT indulges its implied authorial audience in is one in which the regionally popular Taiwanese dramas of yesteryear, whether Minnan family melodramas or Mandarin idol-dramas, collectively represent a romantic, domestic, and sociocultural phase that viewers may look back on fondly and send off like an old and dear friend or like a beloved family member. MDDT grants their “long-lost”83 viewers symbolic closure by metaphorically depicting the untimely and regrettable “death” of Taiwanese dramas, represented by the abrupt deaths of Chen Guang-hui84 and Mei-mei’s lifelong best friend Jin.85 Although the deaths of the two characters take place five years apart, the two deaths occur one after the other within the anachronistic narrative trajectory of MDDT, with the details of Guang-hui’s death unfolding in episode 6 and Jin’s death and funerary rites unfolding in episode 7. The former dies just as he is planning to bring his wife on a long-anticipated trip around the world, while the latter dies after reconciling with an estranged friend. These untimely deaths come to represent the regrettable and premature “death” of Taiwanese dramas and their growing regional popularity in the 2000s, which was unfortunately stunted by the popularity and predominance of K-dramas. I consider this metaphorical on-screen death and farewell to Taiwanese dramas of the past as an elaborate and beautiful illusion because the regional and global popularity of entertainment offerings from South Korea and Taiwan will remain an ongoing contestation and Taiwanese Minnan prime-time family melodramas and Mandarin idol-dramas have not really “died out” at all. In fact, MDDT’s production background might even suggest that the relationship between the two entertainment industries may move toward a more inter-Asian, global-Asian,86 or transnational collaborative model.

Ironically, the symbolic on-screen deaths, farewells, and moving-on from Taiwanese dramas of the past, as they are poignantly depicted in MDDT, potentially usher in a large-scale revival and revitalization of the Taiwanese entertainment industry, and this hope at revitalization is represented by MDDT’s significant departures from old Taiwanese dramatic tropes. Rather than the domestic reunions and matrimonial or romantic unions typical of the happily-ever-after endings that characterize Taiwanese dramas of the past, MDDT ends with a series of necessary but open-ended departures, dispersions, and separations that are at once hopeful and wistful. After selling their home, Mei-mei marries Robert and relocates to Australia to live among his eclectic trailer community. The two sisters continue to live in Taiwan but now live separately, seemingly content with their newfound independence and solitude. Akin to a compelling yet invisible thread connecting its implied authorial audience, the somewhat ambivalent ending of MDDT invites viewers to gather at this shared and mediated sociocultural threshold, where they, too, might consider what their next step might be in terms of their media-viewing preferences, habits, influences, and effects.

Playfully foregrounding the less desirable effects of K-dramas and post-TV SVOD and OTT media consumption cultures and poking fun at how viewers are captivated by absurd and predictable plotlines and archetypes, MDDT gives pause to the uncritical consumption of K-dramas, Taiwanese dramas, and SVOD and OTT-hosted media content. With its ambivalent conclusion, MDDT gestures at the emergent and uncertain possibilities and horizons of global Taiwanese television drama. If there is a happy ending or resolution to be found at the end of the series, it is the implicit reassurance and promise that Taiwanese television dramas, like MDDT, will continue to evolve and will remain an available and increasingly global entertainment option.

Acknowledgments

The author of this manuscript would like to thank Dr. Nahyun Kim of Drexel University for her help in translating the lyrics of the song “Want Rock-Hard Pecs” from Korean to English.

Notes

- Dong-hyuk Hwang, Squid Game, performed by Jung-jae Lee, Hae-soo Park, Ha-joon, and HoYeon Jung, Netflix, 2021, https://www.netflix.com/title/81040344. ⮭

- Jae-kyoo Lee and Nam-su Kim, All of Us Are Dead, performed by Chan-young Yoon, Ji-hu Park, Yi-hyun Cho, and Lomon, Netflix, 2022, https://www.netflix.com/watch/81237996/. ⮭

- Hyejung Ju, “Korean TV Drama Viewership on Netflix: Transcultural Affection, Romance, and Identities,” Journal of International and Intercultural Communication 13, no. 1 (2020): 33. ⮭

- Yi-chi Lien, Light the Night, performed by Ruby Lin, Yo Yang, Cheryl Yang, and Rhydian Vaughan, Netflix, 2021–22, https://www.netflix.com/watch/81482855. ⮭

- David Chuang and Kuan-chung Chen, The Victim’s Game, performed by Joseph Chang, Wei-ning Hsu, Shih-hsien Wang, Netflix, 2020, https://www.netflix.com/watch/81230884. ⮭

- Yu-Tien Huang and Jowon Park, “Taiwanese Korean Drama Viewing Experience through the Internet Prior to Official Import and Its Relationship with the Afterward Intention to View the Officially Scheduled Drama: The Case of ‘The Legend of the Blue Sea’ by SBS,” Journal of Media Economics & Culture 15, no. 4 (2017): 162. ⮭

- Sang-Yeon Sung, “Constructing a New Image. Hallyu in Taiwan,” European Journal of East Asian Studies 9, no. 1 (2010): 25–27. ⮭

- Wei-ling Chen and Chun-hong Lee, Mom, Don’t Do That!, performed by Billie Wang, Alyssa Chia, Chia-Yen Ko, Johnny Kou, Kang-ren Wu, and Po-hung Lin, Netflix, 2022, https://www.netflix.com/watch/81477928. ⮭

- Ming-min Chen, My Mother’s Foreign Wedding [我媽的異國婚姻] (Taipei: Eurasian Press [圆神出版社], 2018). ⮭

- Karen Chu, “Netflix Comedy Series ‘Mom, Don’t Do That!’ Wins Taipei Festival Award Ahead of Worldwide Debut,” Hollywood Reporter, July 14, 2022, https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/tv/tv-news/netflix-comedy-series-mom-dont-do-that-wins-taipei-festival-award-ahead-of-worldwide-debut-1235180986/. ⮭

- Kai Fung, Dragon Legend: Fei Lung, performed by Nic Jiang, Alyssa Chia, Eric Huang, and Phoenix Chang, Formosa Television, 2000–1, Television Series. ⮭

- Yueh-hsun Tsai, Meteor Garden, performed by Barbie Hsu, Jerry Yan, Vic Chou, Ken Chu, and Vanness Wu, Chinese Television System Inc., 2001, Television Series. ⮭

- Hui-ling Chen, Autumn’s Concerto, performed by Ady An, Vanness Wu, Ann Hsu, and Wu Kang-ren, Taiwan Television, 2009–10, Television Series. ⮭

- Yōko Kamio, Boys over Flowers (Tokyo: Shueisha, 1992–2008). ⮭

- Yasuharu Ishii, Boys over Flowers, performed by Mao Inoue, Jun Matsumoto, Shun Oguri, and Shota Matsuda, Tokyo Broadcasting System, 2005, Television Series. ⮭

- Ki-sang Jeon, Boys over Flowers, performed by Hye-sun Ku, Min-ho Lee, Hyun-joong Kim, and Bum Kim, KBS2 and Netflix, 2009, Television Series, https://www.netflix.com/watch/70189961. ⮭

- Helong Lin, Meteor Garden, performed by Shen Yue, Dylan Wang, Darren Chen, and Caesar Wu, Hunan Television and Netflix, 2018, Television Series, https://www.netflix.com/watch/81005506. ⮭

- These Minnan dramas are known as 台語劇 or 鄉土劇 and were popular in China, Hong Kong, Malaysia, and Singapore, as well as other Southeast Asian countries, especially in the 2000s. While the domestic and overseas popularity of these Minnan dramas have undeniably been affected by the popularity of K-dramas, they remain popular among some groups of people in these places. In Singapore, for instance, Minnan dramas like Dragon Legend: Fei Lung (飛龍在天, 2000), Taiwan Ah Cheng (台灣阿誠, 2001), The Spirits of Love (愛, 2006), and Night Market Life (夜市人生, 2009) were and are still often the preferred prime-time television shows of many older Singaporean Chinese generations. ⮭

- W. Michelle Wang, “[這又不是演戲] ‘We’re not playacting here,’ ” JNT: Journal of Narrative Theory 45, no. 1 (2015): 106. ⮭

- Mom, Don’t Do That!, episode 3, performed by Alyssa Chia, Billie Wang, and Chia-Yen Kuo. ⮭

- Mom, Don’t Do That!, episode 1, performed by Alyssa Chia and Nic Jiang. ⮭

- While it is more evident how MDDT is part Minnan family melodrama here, it will be evident later in my article how MDDT is also part romance-idol drama when I dive into Ru-rong and Senior’s romance. ⮭

- Mom, Don’t Do That!, episode 1, performed by Chia-Yen Kuo, Po-Hung Lin, Billie Wang, and Alyssa Chia. ⮭

- These cassette tapes specifically reference the Taiwanese boy band Little Tigers (小虎隊) and the girl group Yu Huan Pai Tui (憂歡派對). ⮭

- An almost identical scenario plays out again in episode 4 when Ruo-min returns to the house again after breaking up with her boyfriend once more. ⮭

- CES, “Reed Hastings, Netflix—Keynote 2016,” YouTube, January 6, 2016, 42:39, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l5R3E6jsICA. ⮭

- It is possible to catch glimpses of this domestic, shared, central television screen in the background throughout the drama series, but this television screen is only featured more prominently in one or two scenes, which I will elaborate on later in this article. ⮭

- Mom, Don’t Do That!, episode 1, performed by Chia-Yen Kuo and Billie Wang. ⮭

- Mom, Don’t Do That!, episode 1, performed by Chia-Yen Kuo and Billie Wang. ⮭

- Tatung is a multinational appliance company based in Taipei. ⮭

- Mom, Don’t Do That!, episode 3, performed by Billie Wang, Alyssa Chia, Chia-Yen Kuo, Po-Hung Lin. ⮭

- Mom, Don’t Do That!, episode 1, performed by Billie Wang and Alyssa Chia. ⮭

- Mom, Don’t Do That!, episode 3, performed by Billie Wang. ⮭

- Mom, Don’t Do That!, episode 3, performed by Billie Wang. ⮭

- Ramon Lobato, Netflix Nations: The Geography of Digital Distribution (New York: New York University Press, 2019), 5. ⮭

- Mei-mei puts in a lot of effort to thematically coordinate her bedroom, clothing, and food she prepares with the nationality, culture, and preferences of her foreign suitors, setting up plants, Godzilla figurines, and national flags. Mom, Don’t Do That!, episode 3, performed by Billie Wang. ⮭

- These scenes depicting members of the Chen family household using their electronic devices separately from one another recur throughout the television series. There are no specific episodes or scenes that stand out, but over the course of the television series, viewers learn that what the three women use their devices for and where and how they use these devices are completely different. These differences in their lifestyles and preferences also implicitly explain why they might not watch television together in the living room after Guang-hui’s death. ⮭

- The ending song of MDDT is Eric Chou’s “Graduation” (最後一堂課), which may also be literally translated as “The Last Lesson.” Metaphorically referring to the inevitable experience of death, loss, and mortality, the song and its lyrics are thematically tied to Chen Guang-hui’s death and the family’s struggle to move on. In episode 6, after Chen Guang-hui dies, a brief scene features the gate of the school where Ru-rong teaches, further connecting Chen Guang-hui’s death to the song’s suggestion of death being the last lesson we all have to reckon with. ⮭

- Mom, Don’t Do That!, episode 4, performed by Billie Wang, Alyssa Chia, and Chia-Yen Kuo. ⮭

- Mom, Don’t Do That!, episode 1, performed by Tien Wa and Alyssa Chia. ⮭

- Viewers are momentarily invited by the camera’s angle to join the Chen family on their couch to watch the same television series we are already watching. ⮭

- Eunice Ying Ci Lim and Kai Khiun Liew, “Her Hunger Knows No Bounds: Female-Food Relationships in Korean Dramas,” in Routledge Handbook of Food in Asia, ed. Cecilia Leong-Salobir (New York: Routledge, 2019), 176–92. ⮭

- Tae-yoo Jang, My Love from Another Star, performed by Ji-hyun Jun and Soo-hyun Kim, SBS TV, 2013–14, Television Series. ⮭

- This phenomenon is also sometimes referred to as the “Chimaek fever,” which is an abbreviation of the Korean words for fried chicken (chikin; 치킨) and beer (maekju; 맥주); Seung-ah Lee, “Soap Opera Drums up Chimaek Fever,” Korea.net, March 3, 2014, https://www.korea.net/NewsFocus/Culture/view?articleId=117903. ⮭

- Byung-hoon Lee, Jewel in the Palace, performed by Young-ae Lee and Jin-hee Ji, Munhwa Broadcasting Corporation, 2003–4, Television Series. ⮭

- Senater, “An Introduction to K-drama Food,” Tell It, September 30, 2021, https://tellit.io/forums/topic/AN-INTRODUCTION-TO-KDRAMA-FOOD/697. ⮭

- Je-won Yoo, Hi Bye, Mama!, episode 3, performed by Tae-hee Kim, Kyu-hyung Lee, and Bo-gyeol Go, tvN and Netflix, 2020, Television Series. ⮭

- The premise of Hi Bye, Mama! focuses on how Yu-ri, a mother who died in a tragic accident, finds herself a ghost roaming the mortal world. Even though her husband subsequently remarried, Yu-ri continues to linger around the household so that she can watch over her family. Yu-ri, as a ghost, frequently fantasizes about the human activities she misses, and one such fantasy has to do with indulging in chimaek as she watches her television dramas. The montage in this scene is meant to show us how much Yu-ri enjoyed indulging in food and drink while watching television dramas on her own, so much so that even in death, this is an activity that she craves and recalls fondly. ⮭

- Seon-ho Park, Business Proposal, episode 2, performed by Hyo-seop Ahn, Se-jeong Kim, Min-kyu Kim, and In-ah Seol, SBS TV, International, and Netflix, 2022, Television Series, https://www.netflix.com/watch/81509457. ⮭

- Dae-young Lee, Be Strong, Geum-soon!, performed by Hye-jin Han and Ji-hwan Kang, Munhwa Broadcasting Corporation, 2005, Television Series. ⮭

- Business Proposal, episode 2, performed by Deok-hwa Lee. ⮭

- “Hi Bye Ma Her Kimchi Water Meme [하바마 그녀의 물김치 짤],” theqoo, February 29, 2020, https://theqoo.net/dyb/1333568597. ⮭

- “Hi Bye, Mama! Gallery: [Normal] Her Kimchi Water [하이바이, 마마! 갤러리: [일반] 그녀의 물김치],” dcinside, February 29, 2020,: https://gall.dcinside.com/board/view/?id=hibyemama&no=739. ⮭

- The thread from theqoo has 1,065 views and two comments, while the thread from dcinside has 648 views and five comments, as of December 9, 2022. ⮭

- Lock & Lock is a household products company based in South Korea. Such containers are commonly used in South Korean households to store kimchi and other food items, and it is my belief that the strategically brief and discreet featuring of a Lock & Lock container in a fictitious television series within another actual television series enables more immersive K-drama world-building. Viewers are invited to share their characters’ reality and delight in the pseudorealism (or hyperrealism) of recognizing a product placement that their beloved K-drama characters are likewise not exempt from seeing and being influenced by. ⮭

- Mom, Don’t Do That!, episode 3, performed by Chia-Yen Kuo and Chloe Xiang. ⮭

- Mom, Don’t Do That!, episode 6, performed by Billie Wang, Alyssa Chia, Chia-Yen Kuo, and Johnny Kou. ⮭

- Mom, Don’t Do That!, episode 2, performed by Billie Wang, Alyssa Chia, Chia-Yen Kuo, and Johnny Kou. ⮭

- Mom, Don’t Do That!, episode 1, performed by Billie Wang and Shao-Hua Lung. ⮭

- The expression “old place” (老地方) is frequently used in Chinese-speaking communities to refer to a usual and preferred meeting place. The expression does not necessarily mean that the place is old and has a positive connotation that generally suggests it is a place that people frequent and are fond of. ⮭

- The ladies of the Chen family address the owner of this roadside stall as 左伯伯 (Zuo bêh4 bêh4; Uncle Zuo) and 老左 (Old Zuo), which signify their regular patronage and familiarity with the owner. ⮭

- Mom, Don’t Do That!, episode 7, performed by Billie Wang. ⮭

- By clicking on the “Watch Credits” option or toggling the Autoplay Next Episode setting on the platform, viewers of MDDT will gain access to the list of Taiwanese and international sponsors and supporting organizations for the television drama, which range from the Taiwanese Uni-President Enterprises Corporation (統一企業公司, the company responsible for Tung-I instant noodles), the Taipei Culture Foundation (台北市文化基金會), the Berlin-based but Asia’s leading online food and grocery delivering platform foodpanda, and South Korean multinational electronics corporation Samsung. ⮭

- For studies that problematize the mukbang phenomenon and its negative effects, see Kang, Lee, Kim, and Yun (2020); Kircaburun, Yurdagül, Kuss, Emirtekin, and Griffiths (2020); and Jeon and Ji (2021). For studies that delve into the motivations, desires, and sociality involved in the mukbang phenomenon, see Spence, Mancini, and Huisman (2019); Kim (2021); and Choe (2019); Eun-kyo Kang, Ji-hye Lee, Kyae-hyung Kim, and Young-ho Yun, “The Popularity of Eating Broadcast: Content Analysis of ‘Mukbang’ YouTube Videos, Media Coverage, and the Health Impact of ‘Mukbang’ on Public,” Health Informatics Journal 26, no. 3 (2020): 2237–48; Kagan Kircaburun, Cemil Yurdagül, Daria Kuss, Emrah Emirtekin, and Mark D. Griffiths, “Problematic Mukbang Watching and Its Relationship to Disordered Eating and Internet Addiction: A Pilot Study among Emerging Adult Mukbang Watchers,” International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction 19, (2021): 2160–69; Chang-young Jeon and Yunho Ji, “A Study on Irrational Consumption Tendency According to Exposure of Video Contents of Mukbang (Eating Broadcasts) and Cookbang (Cooking Broadcasts),” International Journal of Tourism Management and Science 36, no. 1 (2021): 23–40; Charles Spence, Maurizio Mancini, and Gijs Huisman, “Digital Commensality: Eating and Drinking in the Company of Technology,” Frontiers in Psychology 10 (2019): 1–16; Yeran Kim, “Eating as a Transgression: Multisensorial Performativity in the Carnal Videos of Mukbang (Eating Shows),” International Journal of Cultural Studies 24, no. 1 (2021): 107–22; Hanwool Choe, “Eating Together Multimodally: Collaborative Eating in Mukbang, a Korean Livestream of Eating,” Language in Society 48, no. 2 (2019): 171–208. ⮭

- Jooyeon Rhee, “Gender Politics in Food Escape: Korean Masculinity in TV Cooking Shows in South Korea,” Journal of Popular Film and Television 47, no. 1 (2019): 56–64. ⮭

- Mom, Don’t Do That!, episode 4, performed by Chloe Xiang. ⮭

- Mom, Don’t Do That!, episode 1, performed by Billie Wang, Johnny Kou, Alyssa Chia, Chia-Yen Kuo, and Kang-ren Wu. ⮭

- Mom, Don’t Do That!, episode 4, performed by Chia-Yen Kuo and Chloe Xiang. ⮭

- Mom, Don’t Do That!, episode 7, performed by Chloe Xiang. ⮭

- Mom, Don’t Do That!, episode 7, performed by Chloe Xiang and Chia-Yen Kuo. ⮭

- This is yet another K-drama trope that is not often acknowledged among scholarly communities but is well-established among K-drama fans. The fan-made YouTube video “6 K-Drama Scenes that Prove We Want Our Men to Cook for Us,” with twelve thousand views, compiles six different K-drama montages that feature an attractive male character cooking. The video demonstrates how common these scenes of masculine cooking are in K-dramas and how aesthetically pleasing these scenes are meant to be. Amusing Sphere, “6 K-Drama Scenes that Prove We Want Our Men to Cook for Us,” YouTube, February 9, 2021, 4:15, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ciszKngW8Rw. ⮭

- Mom, Don’t Do That!, episode 1, performed by Alyssa Chia and Kang-ren Wu. ⮭

- Mom, Don’t Do That!, episode 3, performed by Alyssa Chia and Kang-ren Wu. ⮭

- Mom, Don’t Do That!, episode 3, performed by Alyssa Chia and Kang-ren Wu. ⮭

- Mom, Don’t Do That!, episode 7, performed by Alyssa Chia and Kang-ren Wu. ⮭

- Matthew Yen (嚴云農, kumono_yan), “而我最想給你的,是一雙翅膀,讓你從我的世界,飛出去 …,” [But what I wish to give to you the most, is a pair of wings, so that you may take flight and depart from my world …,] Instagram, July 25, 2022, https://www.instagram.com/p/CgbKwKGB4jf/. It is worth noting that this “Korean love song” is written in grammatically incorrect Korean or broken Korean, and part of the song’s lyrics even include comedic lines that can be roughly translated as “I want to sing Korean song, but I don’t know Korean,” “Let’s go Korean,” and “Sing Korean song, it doesn’t matter if I don’t understand it,” ironically highlighting how Korean songs, especially those with romantic themes, are popular even though many international consumers of K-dramas do not know what the songs are actually about. The author of this article would like to thank Dr. Na-hyun Kim for her help in translating and transcribing the lyrics of this song. ⮭

- Mom, Don’t Do That!, episode 9, performed by Alyssa Chia and Kang-ren Wu. ⮭

- Mom, Don’t Do That!, episode 1, performed by Billie Wang, Alyssa Chia, and Kang-ren Wu. ⮭

- Mom, Don’t Do That!, episode 1, performed by Alyssa Chia, Chia-Yen Kuo, and Kang-ren Wu. I refer to the actor Kang-ren Wu or Chris Wu as a Taiwanese idol-drama actor because one of his most well-known roles is that of the supporting male lead Hua Tuo Ye in the idol-drama Autumn’s Concerto (2009). Notably, Ru-rong’s adulation of actor Kang-ren Wu is also self-reflexive in that Alyssa Chia—the actress who plays Ru-rong—recently starred in another Taiwanese television drama, The World Between Us (2019), alongside Kang-ren Wu. ⮭

- Mom, Don’t Do That!, episode 1, performed by Alyssa Chia and Kang-ren Wu. ⮭

- Mom, Don’t Do That!, episode 2, performed by Billie Wang and Alyssa Chia. ⮭

- W. Michelle Wang, 【這又不是演戲】 ‘We’re not playacting here,’ ” JNT: Journal of Narrative Theory 45, no. 1 (2015): 107–8. These are all expressions that Wang uses to describe the narrative and affective effects of self-reflexive devices on the implied authorial audience of Taiwanese idol-dramas. ⮭

- “Long-lost” is in scare quotes as these viewers have never really gone anywhere but have simply diversified or changed their media-viewing preferences. Some viewers, like the author of this article, have never really left and are still avid supporters of Taiwanese dramas. ⮭

- Although viewers know since the start of the series that Chen Guang-hui died, the twelve hours that lead to Chen Guang-hui’s death are only covered in detail in episode 6 of the television series. ⮭

- Jin is Mei-mei’s life-long best friend. Episode 7 of the television series focuses on her passing and funerary rites. ⮭

- Depending on one’s preferences, this phenomenon may also be described as or belong to existing Pan-Asian or Trans-Asian discourses. ⮭

Eunice Ying Ci Lim is a PhD candidate in comparative literature and Asian studies (dual title) at Pennsylvania State University. Her research interests are in contemporary Southeast Asian and East Asian literature and media, with a focus on non-Mandarin Sinitic languages, language policy, translingualism, and Sinophone-Anglophone intersections. Her book chapter on representations of gendered food consumption in South Korean television dramas (coauthored with Dr. Liew Kai Khiun) is published in the Routledge Handbook of Food in Asia (2019). Eunice has also published in the journal Antipodes and ariel: A Review of International English Literature (forthcoming in 2023). Her dissertation focuses on the intergenerational effects of Singapore’s language policies and how contemporary Sinophone and Anglophone literature and media deftly negotiate and respond to these language policies.