Introduction

The Nollywood film industry expresses, among other things, a powerful Nigerian national pride. Nigeria’s size (two hundred million people, 20 percent of the world’s Black population) and ethnic diversity (four hundred languages are spoken) give it an exceptional dynamism, power, and significance in many dimensions. The government of Nigeria is not, generally, the source or focus of pride. This essay describes two analogous and intertwined sources of national identity that have welled up from below, unofficially, out of popular culture: Nollywood and the lingua franca Nigerian Pidgin. Between them, they provide crucial media through which Nigerian stories get told and the notion of Nigeria as a nation is created and reproduced.

State Failures (and Some Successes)

Nigeria is certainly not a failed state, as the term is applied to places like Somalia. But the government of Nigeria has failed in conspicuous ways. Life expectancy is only fifty-four years. Nigeria has surpassed India as the country with the largest population of the desperately poor, and a fifth of the world’s out-of-school children are in Nigeria.1 The whole educational system, once ambitious and still vast, is in abysmal shape—a looming catastrophe in a nation where the median age is eighteen and an economy dependent on oil exports approaches a foreseeable dead end. Electricity and running water are unreliable where they exist at all. The state has no monopoly of violence. Kidnapping for ransom afflicts most of the country, and armed insurgencies, banditry, and warlordism affect five of the nation’s six geopolitical zones—all but the southwest, home of Lagos, the commercial capital and center of Nollywood. Spectacular levels of corruption underlie all these failures.

Generations of political leaders, and indeed Nigerian society itself, must be held responsible for this situation, but Nigeria’s historical insertion into the world system is also a very important factor. During the centuries of the transatlantic slave trade, Europeans called what became Nigeria “the Slave Coast.” The huge demand for African bodies created a political and moral race to the bottom that reached far inland. Firearms, available only through the Europeans, enabled the acquisition of enslaved people and were indispensable for defense against aggressive slave traders. It was difficult or impossible to opt out of trading. Powerful new political formations—“secondary empires” such as the kingdoms of Oyo and Benin and the “canoe houses” of the Niger Delta and Cross River—arose on this basis, often displacing more consensual forms of governance.

At the end of the nineteenth century, the European “scramble” to impose direct colonization on Africa created what the historian Basil Davidson called “the Black Man’s Burden”: a state imposed by colonial masters on societies that did not want it, a state utterly foreign in language, culture, historical evolution, and ideology, and clearly exploitative in intention. The colonized naturally regarded this government with cynicism. The morality produced by Africa’s myriad indigenous political cultures did not apply. The tragedy of postcolonial Africa is that Africa could not do without the structures of the modern nation-state, and as a practical matter, undoing the absurd borders the Europeans had drawn was impossibly difficult. African elites rushed to fill positions vacated by the colonizers, but the structures remained basically the same, as did the problem of political legitimacy.2

Obafemi Awolowo, a leading nationalist architect of independent Nigeria, famously remarked, “Nigeria is not a nation. It is a mere geographic expression.”3 The name “Nigeria” was invented by the girlfriend of the British colonial governor general Frederick Lugard, who amalgamated two colonial holdings: a predominantly Muslim north and a south that would become predominantly Christian. More than a century later, this remains a profound division. But it is only the most dangerous conflict in a nation assembled for the convenience of the colonizer out of peoples from hundreds of different cultures and thousands of different polities. The British engineered a system of politics based on ethnic competition among these many groups, which was reformulated at the time of independence as the issue of “how to divide the national cake”—a spoils system in which communities sent politicians to the center of power to get whatever they could.

By the end of the first decade after independence in 1960, this system exploded in coups and a horrendous civil war. The’70s brought an oil boom and the “resource curse,” amplifying corruption as the essential logic of the system. Exuberant “kleptocracy” under restored civilian rule led to another round of coups in the 1980s, but corruption continued unabated and the military oversaw a criminalization of the state—political scientists were busy creating a vocabulary to describe processes at work across Africa.4 In the mid-1980s, neoliberal structural-adjustment programs were imposed on heavily indebted nations around the world by the World Bank, International Monetary Fund (IMF), and other lenders, with uniformly disastrous results. Projects of national development crashed along with the whole formal economic sector. Governments no longer had the revenues or capacities to carry out basic functions of education, health care, and security.5

In the midst of all this, somehow a sense of Nigerian national identity took hold. Generations grew up saluting the flag, singing the national anthem, and supporting the national football team. The national educational system—entirely in English, the official language, at least past primary school—aimed at universal, free primary education and created universities where important work of intellectual decolonization took place.

Not least in importance was television, which began in Nigeria in 1959—the first in Africa. Stations sponsored by regional (later, state) governments carried a lot of programming in indigenous languages and featuring local cultures. The national network—the Nigerian Television Authority (NTA)—was more deliberate in creating a sense of national culture, a role national televisions have often played. The national news broadcasts may have been turgid, but they addressed Nigerians as one. So did the extremely popular television serials, which were crucial in creating a national linguistic medium.6 Though typically centered in one household, they contained characters from various ethnicities—a casting formula that continues up to today in Nigerian screen media. This deliberately created an image of the multicultural nation, responding to the challenge of making a nation out of an exceptionally diverse population.

The linguist Nicholas Faraclas describes that complexity: “Home to a highly mobile, vibrantly enterprising, and intensely commercially-oriented population, the territory known today as Nigeria has for millennia been one of the most pluri-cultural and pluri-linguistic parts of the world. Its people speak nearly 400 ancestral languages.” Faraclas also describes methods of dealing with this complexity, long embedded in the population: “From well before European contact to the present, the average West African child has grown up with a command of at least one or two local languages as well as a pidginized, creolized, and/or koineized regional market language. When the Europeans arrived, pidginized, creolized and standard varieties of European languages were added to this rich linguistic repertoire.”7

The NTA’s multiculturalism, then, was not (just) a state imposition but a reflection of a lived reality. In line with the NTA’s nationalist purposes, Nigerian Standard English was the framing language. The great original serial, The Village Headmaster (on air from 1968 to 1988), was about an apostle of modernity in a fictional Yoruba community. The village was on a road, so all sorts of people passed through or settled, adding their varieties of speech, with loan words from various languages; Nigerian Pidgin English was used extensively. The result was a playful, rich, and pungent linguistic “soup”—an endless source of comedy, and a way for the whole audience to find itself in the show. Being a Nigerian was made to seem fun.

The NTA television serials are the most important of all the sources of the later video film industry known as Nollywood.8 Nollywood films immediately spread far beyond Nigeria’s borders—across the African continent, the Caribbean, and beyond—through no effort of the films’ producers and usually without their knowledge, first carried by informal market traders and pirates and later through satellite broadcasting and the Internet. Nigerian film culture could travel in this remarkable fashion because it was already multicultural.

Nollywood

Nollywood burst onto the world scene in 1992 as a dramatically new phenomenon: a major film industry based entirely on analog video technologies, from cameras through postproduction work to distribution on cassettes. The economic crisis stemming from the structural adjustment program destroyed Nigerian celluloid film production and exhibition and greatly weakened the NTA. Trained personnel from the NTA found a video-distribution system in the “infrastructure of piracy” (Brian Larkin’s phrase9) that had been created in the informal economic sector to service the VCRs of the middle class with pirated Hollywood, Bollywood, and Hong Kong films. And, they found a model for production in the Yoruba Travelling Theatre tradition, whose artists had moved dexterously from itinerant stage performances to television and celluloid film. They, too, operated in the informal sector. (Seminal academic work by Biodun Jeyifo and Karin Barber on “the African popular arts,” defined as informally produced, springing from and addressed to the heterogeneous masses of African cities, and requiring little capital or formal education, had the Yoruba Travelling Theatre as their subject.10)

Three parallel video film industries were created at the same moment, divided on a linguistic basis. The one that would later be called Nollywood began by making films in Igbo, the language of the “marketers” (so-called because they operated in the informal markets of Lagos and the cities of southeastern Nigeria). But production soon switched over to English because profits were greater on the national market for films in the national language, and personnel from numerous ethnic groups joined the industry, though the Igbo marketers maintained their dominance of distribution and much of film financing. Yoruba Travelling Theatre artists established their own Yoruba-language industry, and a Hausa-language industry was established in northern Nigeria, centered in Kano.11 These three branches of the Nigerian video industry still have their own professional organizations and marketing systems. The triplication is a sign of its grassroots origins and the lack of any centralized control or encouragement.

The government paid very little attention to the new industry. The parastatal charged with regulation and classification changed its name to the National Film and Video Censors Board, but in practice, it has done very little censoring, aside from occasional, often ill-conceived interventions. (According to many producers, it has done very little of anything besides collect envelopes of cash in return for the stamp of clearance.) The higher officials—like nearly all the producers and directors who had been working in celluloid film and like the more educated sector of the population generally—looked down on the rough productions of the upstart medium, with their raw expressions of “superstitious” beliefs, crime, and other embarrassments to the national image, and for a long time hoped that the video films would just go away.12

The Hausa film industry has had a difficult time with Kano State’s censorship board and with restrictions of a conservative Muslim culture, against which the movies have often gently pushed.13 But the Nollywood and Yoruba industries have seldom given the censors much to worry about. Producers are, and feel, vulnerable to the losses that would result from even a single film being banned. In any case, they have, in large part, picked up the NTA’s mantle as a unifying national force and as the champion both of modernization and of the preservation of “tradition.” National unity is assumed as a value; the truly dangerous religious division between Islam and Christianity never comes up (though it is common to see a Christian pastor doing battle with the forces of darkness, which frequently wear the face of indigenous religions). This restraint is striking in light of Nollywood’s predilection for the scandalous. From the beginning, excitement about the new film culture was generated partly by its difference from the kinds of things the NTA would broadcast. The “get-rich-quick” films that initially branded Nollywood film culture featured murderous occult money rituals, witchcraft, demonic possession, prostitution, drug dealing, criminal fraud, and so on.14

A second parastatal, the Nigerian Film Corporation, has mattered even less. Denja Abdullahi, surveying the history of the government’s relationship with the film industry, writes, “Well or badly led, the parastatals are inert, ineffective, irrelevant bureaucracies… . merely fulfilling the motions of officialdom… . The flurry of recent government interventionist measures in the industry is akin to that of an architect rushing to a building site with a blueprint after the builders and craftsmen have completed the building of the house.”15

It is what the government has failed to do that has structured the industry. Piracy is a problem for all film industries. The whole Nollywood business model of churning films out rapidly on very low budgets is premised on the fact that films will be pirated before a larger investment can be recovered. The Nigerian government has never been serious about solving or even limiting this problem. The penalties are so mild they encourage rather than deter piracy. Intellectual property rights, or indeed any form of contract law, are generally not respected in Nigeria, and there is strong evidence of official collusion.16 Politicians take money from the pirates at election time and so will not prosecute them. The largest pirate in Lagos is said to be sheltered in a military cantonment where the police cannot come.

In 2007, the censors board tried to transform the distribution structure from the “informal” system set up by the marketers, where virtually nothing was written down, to a formal, more transparent one in which larger-scale capitalist corporations could invest. The marketers saw this as an attempt to take away control of the business they had built; the opacity of their methods served to maintain their dominance.17 They fought this initiative to a standstill.

But the intervention of formal capitalism was inevitable, given the enormous potential profits in this underdeveloped sector of the global media market. The period of Afropessimism, during which the international community largely wrote off Nigeria’s future, was replaced in about 2005 by the “Africa rising” narrative: for a decade, African countries had some of the highest growth rates in the world as foreign investors realized the potential of a reviving middle class. Nigeria remained a difficult place to do business, but the government of Lagos State turned the nation’s commercial capital into a plausible destination for direct foreign investment. Telecom companies were the star performers. Upscale shopping malls began to appear in Nigeria’s major cities and multiplex cinemas in them.

Simultaneously, media distribution across the globe was shifting from material media such as video discs to immaterial transmission through Internet streaming and satellite or cable broadcasting systems.18 Such technologies are far beyond the capacities of the tiny Nollywood production companies. In Nigeria, the two most consequential corporations in this new world were the transnational Internet startup iROKOtv—“the Netflix of Africa”—and the South African satellite broadcaster MultiChoice. MultiChoice’s Africa Magic channel—now a bouquet of eight channels—soon reached nearly everywhere on the African continent. Both satellite broadcasting and Internet streaming require massive amounts of content and would have been inconceivable without the enormous volume of films produced by Nollywood and their attractiveness to audiences outside of Nigeria. In 2013, both of the aforementioned corporations and others began investing in the production of their own original content, both feature films and serials.19

The current state of the industry is as follows.20 The original Nollywood industry, based on the disc market, still exists and still makes the same kind of movies, but its center of gravity has shifted from Lagos to the Igbo part of the country, where the marketers are from. Profit margins and budgets are lower than ever, and it gets much less media coverage than it used to. It is hard not to see it as provincialized if not residual, though predictions of its demise have always been wrong.

The term New Nollywood began to be used around 2010 to describe films of higher technical and artistic quality, made possible by and designed for the new multiplex cinemas.21 There are still very few cinemas and, aside from the occasional blockbuster, filmmakers mostly make little or no money in them, but investors in all but low-budget films want assurance of a coveted slot on the big screens. This means pleasing the very specific demographic of the cinema audience: disproportionately young, affluent, educated, and shaped by transnational (United States) tastes. From the cinemas, films are “windowed” through video on demand, satellite subscription services, sale to airlines, and so on. Often, distribution to the impoverished masses on disc or by downloading to phones is left to pirates. The satellite and Internet corporations pay for great quantities of cheap content—$10,000 per film or less—that must meet minimal technical standards and often feature beautiful people in beautiful settings, but mostly are negligible artistically.

This system is thoroughly neoliberalized, the various platforms corresponding to class divisions, and is very unlike the fundamentally democratic system imposed by the piracy of discs, which requires that the film reach everyone at once, before the pirates got at it. Nollywood began at a moment of crisis when the creative personnel who deserted or were deserted by the national institution of the NTA found common cause with a whole nation suffering from extreme precarity and disgust at the wickedness of their rulers, and so Nollywood often mounted a stinging social critique. Filmmakers saw market women as their target demographic—dogged workers in the informal economy who would have the price of a movie at the end of the week. Now, at the pinnacle of Nollywood, privileged cinemagoers watch slickly produced images of the lives of successful professionals in enclaves of wealth, in films that largely accept the premises of this life.

The formation of social classes and the consolidation of distinct class cultures is a relatively recent phenomenon in Nigeria—of course, this is not a simple matter—but it is proceeding rapidly and Nollywood is implicated in it. But the creation of divisions is by no means the whole story. The logic of the most highly capitalized media platforms—satellite broadcasting and Internet streaming—depends on aggregating diverse audiences all willing to pay a subscription fee rather than producing a single product imposed on the whole audience. People channel surf between New Nollywood and the old; Africa Magic has channels in Yoruba, Hausa, Igbo, and Swahili as well as English, and many people watch films that are not in their mother tongues.22

It is possible to see the increasing range of Nigeria’s film production structures not as balkanization but as a source of strength. If at the top end Nollywood is more open than ever to foreign models and inspirations, its popularity depends on staying open at the bottom, maintaining the sense the audience has always had that it tells “true stories”—meaning what is felt to be their own stories, in the form they want them told. From the beginning, Nigerian consumers were willing to pay more for a Nigerian film made on a budget of 15,000 USD, with all the deficiencies that budget entails, than for a (pirated) 250 million USD Hollywood film, because Nollywood expressed their world. Nigeria’s film culture and film industry still depend on this intimate relationship with its audience’s desires and sense of identity and, as always, the linguistic dimension is key.

Nigerian Pidgin

Nigerian Pidgin figures in this essay as an important element in Nollywood films and a significant ingredient in their success. It also figures as a strong parallel phenomenon: it, too, is a central and unifying cultural expression, grounded in multiethnic popular culture; it, too, has been largely ignored if not opposed by the government and other official institutions, but nevertheless, it, too, has become a major or even dominant cultural force.

Nigerian Pidgin is a creole (i.e., spoken as a first language) for about five million Nigerians, mostly in the Niger Delta region where the language was formed. But, according to Nicholas Faraclas,

It has been estimated that, “given the rapid spread of Nigerian Pidgin (NPE) among younger Nigerians, this proportion should increase to cover over seventy or eighty percent by the time the present generation of children reaches adulthood.”24 Only something like 57 percent of Nigerians have some proficiency in Standard English.at least half of all Nigerians (along with millions more in the diaspora) speak Nigerian Pidgin in some form. With a speech community of over 75 million [this number should be revised upwards in line with the current estimated population of 200 million or more], Nigerian Pidgin is not only the African language with the largest number of speakers, but also the most widely spoken pidgin/creole language in the world… . Nigerian Pidgin has become far and away the most popular, widely spoken, readily learned, practically useful, and fastest growing language in Nigeria today.23

Nigerian Pidgin is not evenly distributed geographically. In northern Nigeria, Hausa serves as the lingua franca. In the cities of the north, Pidgin flourishes in the neighborhoods of nonindigenes and in the shadow of the institutions of the national government, with their multiethnic personnel: military and police barracks, offices of the bureaucracy, boarding schools and universities, and the highway network. In southern Nigeria, Pidgin flourishes in these contexts also, but commerce and polyglot urbanism are far more important in making a working knowledge of Pidgin nearly indispensable.

National languages of this level of importance are normally promoted in a standardized form by the powers that be. But Nigerian Pidgin spread without any such form of political or cultural patronage, and it has been given no recognition by the Nigerian government. English, French, and the three most widely spoken indigenous African languages (Hausa, Yoruba, and Igbo) are official languages, but Pidgin is not mentioned in the Nigerian Constitution or in government policy. The educational system ignores and actively discriminates against it: much of English-language instruction involves beating Nigerianisms out of students, who have often been punished for using Pidgin. Discourses of contamination and contagion are regularly invoked in this context.25 Nigerian linguists have been divided on the subject of the status Pidgin should have. Some eminent figures have for decades advocated recognizing Pidgin as an indigenous Nigerian language (Ayo Banjo) and adopting it as an official language (B. O. Elugbe). But prejudices against it have been deeply entrenched.26

The Nigerian linguist Charles C. Mann calls Pidgin “the language of sociocommunication, intimate and familiar conversation, humour, anger and proverbs” and “in many urban centres, the principal medium of public trading and exchanges.” He quotes B. Mafeni: “Many Nigerians, although they use Pidgin as a register in certain, especially familiar contexts, are nevertheless ashamed to be associated with the language in public. This is probably a result of the influence of parents and school authorities, who have often discouraged its use because they consider it a debased form of English and not a language in its own right.”27 In a later study, Mann critiques a system for gauging “ethnolinguistic vitality” that uses three criteria—status, demography, and institutional support—pointing out that Nigerian Pidgin has none of these: its status has been very low, it is not the traditional language of any ethnic group, and it has gotten no institutional support.28 Pidgin has flourished anyway, and when the government really needs to reach the masses of the population—in public-health campaigns, for example—it has always turned to Pidgin. Without the prestige of “authentic,” “traditional” culture or of elite modernity, Pidgin is associated with the intermediate zone, vastly fertile but often disrespected, from which African popular culture comes.29

Nigerian Pidgin was created in the context of early British trading on the coast, when human beings were the most important commodity. Pidgin was a necessary means for the enslavers to communicate with those on shore and those in the holds of their ships. It remains a language of command, what masters speak to their servants and what police bark at those they stop on the roads. But the passage by Nicholas Faraclas quoted earlier suggests a different and more important genealogy, one rooted in the long history of intercommunicability among the peoples of this exceptionally rich linguistic region. Kelechukwu Ihemere stresses that “at every stage of its history, Nigerian Pidgin has been used primarily as a means of communication among Nigerians rather than between Nigerians and traders, missionaries or other foreigners.”30 But it has had a strong association with the lower classes, those without the formal education through which they would learn “proper” English.

In 2008, the linguist Herbert Igboanusi published an essay titled “Empowering Nigerian Pidgin: A Challenge for Status Planning?” in which he makes solemn recommendations for measures that the government and other institutions could take to improve the status of Pidgin.31 But Nigerian society was already dramatically altering its attitude toward Pidgin, whose place in the culture has been transformed.

By the mid-1980s, “it was no secret that the most socially popular adverts, public awareness jingles, drama sketches, record request programmes, etc.” were in Pidgin, and it had begun to be used for news and debate broadcasts on radio and television in the Niger Delta region.32 Wale Adenuga’s 1984 Pidginphone celluloid film Papa Adjasco was a huge hit as was his later television serial of the same name. Hotel de Jordan (1988) was the first popular Pidgin television serial. All these exploited Pidgin’s association with humor.

To the extent that one person can be said to be the agent of Pidgin’s new prestige as a language of serious discourse, that person is the musician Fela Anikulapo Ransome-Kuti (1938–1997). Fela was born into the cultural and nationalist political elite of the Yoruba city of Abeokuta. He was radicalized during a sojourn to the United States in 1969, which exposed him to the Black Panther Party and other revolutionary currents in African American and Pan-African thinking. Thereafter an implacable foe of successive Nigerian governments, he was frequently jailed and severely injured by the police and soldiers. Fela’s public persona was a calculated affront to Nigerian norms of respectability. He performed wearing nothing but underwear, smoked marijuana constantly onstage and off, and once married twenty-seven women in one ceremony (all dancers at his club, thereby protecting them from police harassment).

At the beginning of his career, Fela sang in Yoruba and English; after his radicalization, he sang in Yoruba and Pidgin, the change expressing a commitment to linguistic solidarity with the oppressed masses and to a recognition that Pidgin was the key to actually reaching those masses and to the political unity that might result.33 Pidgin was the language of his “yabis,” the fierce commentaries on political and cultural matters that were interspersed with music.

Fela’s funeral in 1997, near the end of a long period of military dictatorship, drew a crowd of one million people who effectively shut down the center of Lagos. His stature has only increased since then. His music is the indispensable soundtrack for Lagos life and his songs became anthems for a generation or two of professionals who came of age under military rule. The strange conversion of Fela into something like official culture seemed complete when president Emmanuel Macron of France visited Nigeria in 2018. He had interned at the French embassy in Lagos and become a Fela fan, so on the occasion of his visit, a meeting with stakeholders in the media and culture industries convened at the New Afrika Shrine run by Fela’s children. A far cry from Fela’s original club, which was a rough structure in a rough neighborhood and protected from the police by local street gangs, the New Afrika Shrine is a stone’s throw from the Federal High Court and the seat of Lagos State government, and is adorned with corporate advertising.

In 2007, an all-Pidgin radio station, Wazobia FM, began broadcasting in Lagos. According to Yomi Kazeem, “In its early days, Wazobia faced doubters from advertising circles and even among some of its own staff. Indeed, as professional broadcasters seemed unsure of taking up Pidgin, Wazobia’s first radio hosts were cleaners hired from the restaurant business owned by its parent company.”34 But it quickly became the most popular station in Lagos. More than 60 percent of the radio audience in Nigeria’s four major cities listens to all-Pidgin stations.35 Sports commentary is now often in Pidgin, including on transnational satellite channels, and stand-up comedy, which has become a major form of popular culture and big business with corporate-sponsored tours, almost invariably is in Pidgin. The lyrics of Afrobeats, the hip-hop-influenced reigning Nigerian musical style, have Pidgin at the center of their constant code switching.36 In 2011, Google launched a Pidgin interface, and the BBC established an immediately successful Pidgin language service in 2017. All the telecommunications companies offer their call center customers the option of using Pidgin.37

Dramatic evidence of how far Pidgin has come since it was seen as the language of the lower, uneducated classes is that it is widely used as a primary language for text messages and for all kinds of online commentary and customer comments. In this context, Theresa Heyd and Christian Mair argue that Nigerian Pidgin’s new coolness puts it on a trajectory (previously followed by African American Vernacular English and Jamaican Creole) from a stigmatized vernacular “to social capital, to an asset that can be marketed and, ultimately, monetized … our data can be seen as evidence of early-stage commodification” of the language. They associate this development with Nollywood and the increasing international popularity of Nigerian musicians.38

In 2009, the Naija Languej Akademi was founded, aiming to rebrand Nigerian Pidgin as Naija, to create a standard orthography and generally to promote its use and study. Naija is a slang term for the nation of Nigeria, which had begun also to be used to name its lingua franca. Jenny Benjamin Inyang identifies the name change as an ideological move designed to do several things. It jettisons the term Pidgin on the grounds that Nigerian Pidgin has become creolized as the first language of many of its speakers, that the language now serves many purposes beyond those of a contact language, and that Pidgin carries connotations of inferiority, of being derivative and less than an independent language in its own right. The name change embraces Naija because it identifies the language with the nation and its values—a unifying gesture, celebrating the lingua franca that has functioned so powerfully to allow communication among Nigerians, thereby making this multiethnic nation possible. And the move also marks the language that Nigerians have created for themselves as distinct from all the other closely related pidgins and creoles spoken in Sierra Leone, Liberia, Gambia, Ghana, Cameroon, and Equatorial Guinea.39

Proponents of Naija/Nigerian Pidgin point to the fact that communicating across ethnicities is in its very nature. Unlike all other Nigerian languages, it is spoken by people from every regional, ethnolinguistic, and religious group in the country, and unlike Nigerian Standard English, it is spoken by all social classes rather than only by the relatively privileged who have had the years of formal education needed to reach proficiency.40 It has been credited with downplaying differences and engendering peaceful coexistence in ethnically heterogeneous cities such as Warri, Sapele, and Port Harcourt.41 Well over a million people for whom it is their first language are the offspring of multiethnic marriages.42

Nigerians have agreed to keep English as their main official national language in no small part because it is not the language of any particular Nigerian ethnic group that might be suspected of ambitions to dominate the whole country. Pidgin has the unique advantage of being a “language that is both home grown and ethnically detached.”43 Faraclas observes that the sounds of Pidgin—its particular selection of consonants and vowels, and its tonal patterning—come from the commonalities of the indigenous substrate languages.44 So it feels familiar and homey to Nigerian ears, not foreign like English. Even for those who do not speak it or understand it well, it expresses a will to communicate and a faith that communication is possible.

Those who are opposed to Pidgin may fear its supposed corrupting influence on “proper” English; they may also fear its erosion of indigenous Nigerian languages. Even the largest and strongest Nigerian languages are to be in danger of disappearance as the younger generation declines to learn or at least to master them. They often are supported in this by their parents, who see English as “the language of success” (a phrase used by Moradewun Adejunmobi in an early and important essay on the linguistic character of Nigerian video films)45, or, as the filmmaker Tunde Kelani put it to me, they see English as the language of those who have pillaged the Nigerian economy and they want their children to be among the pillagers, not the pillaged.46 Nigerian cultures largely did not use writing before the advent of Islam and European colonialism. Much of Nigerian culture exists only in the oral tradition, which is suffering catastrophic loses as urbanized, often de-ethnicized Nigerian youth decline the slow processes of linguistic and cultural transmission and the long discipline of mastering traditional verbal arts.

As elsewhere, young people are glued to their phones, where they find a world saturated with transnational media. But this does not mean that Nigerian youth want to stop being Nigerian. Speaking Pidgin, listening to polyglot Afrobeats music, attending Pidgin stand-up comedy performances, and watching Nollywood films all are ways of being proudly African while also being urban, modern, and open to a globalized media environment. Rudolf Gaudio demonstrates how precisely Nigerian musicians have located Nigerian culture within that environment:

Elsewhere, Gaudio makes a parallel argument for the cultural work of stand-up comedians:Their performances often combine elements of coastal west African musical styles, such as highlife and Afrobeat, with African American and Afro-Caribbean styles, especially hip hop and reggae; and their lyrics juxtapose NP, English, and various Nigerian languages alongside African American English and occasionally Jamaican Creole. By aligning Nigerians’ cultural and political experiences with those of African Americans and Jamaicans—whose languages have also been stigmatized as “broken English”—these artists engage what Thompson (1984) and Gilroy (1993) have called the Black Atlantic artistic tradition. At the same time they index a distinctly Nigerian public within that transnational cultural space.47

For musicians, stand-up comedians, and Nollywood film producers, using Pidgin and code switching are a commercial strategy—a strategy to increase the potential national market, in the first place, but also to amplify their roles as regional media hegemons across the continent and the Black Atlantic. Pidgin creates intercommunicability or at least resonances of a shared heritage with other West African pidgins and creoles, Jamaican Patois and Barbadian Creole, and African American Vernacular English. Nigerian Afrobeats stars are collaborating with leading US hip-hop artists, and the business of Internet streaming of Nigerian films has, because of the slow speeds and high data costs of the Internet in Nigeria and elsewhere in Africa, depended principally on the enormous Nigerian and African diaspora created by decades of brain drain. In Brooklyn and in London, having parents from Nigeria—or (for that matter) Bangladesh or Egypt—is now cool in a way it wasn’t ten years ago, and in this world held together by phones and laptops, Nigerian Pidgin and Nollywood films are major elements.Through their use of NP and English, Nigerian comedians are helping to forge a racially conscious Nigerian national (and transnational) public by highlighting and making fun of the country’s fraught historical and contemporary relationships with predominantly White, English-speaking nations, especially the United Kingdom and the United States.48

Nigerian Pidgin on Screen

As far as I am aware, there is nothing like a comprehensive academic account of the role Pidgin has played as a language of Nigerian filmmaking. Often it is left out entirely. The National Film and Video Censors Board categorizes films according to language, recognizing English, Igbo, Yoruba, Hausa, Bini, Esan, Ibibio, Urhobo, Etsako, and Itsekiri—but not Pidgin, which is silently assimilated to English.49 Debates on what language(s) African filmmakers should use in their films closely parallel those about African literature; in both cases, the debates are as old as the media. They tend to be cast in binary terms as a choice between indigenous African languages, which have the virtues and advantages of “authenticity,” and English or the other “world” languages imposed by colonialism, which are now also national languages in Africa, which can reach beyond a particular ethnic group to national and international audiences.50 Pidgin slips through the cracks of this debate. The most detailed analysis of code switching in Nollywood films centers on a film (Jenifa, 2008) that constantly mingles Yoruba and English; Pidgin is scarcely mentioned and is treated as a subset of English.51 There has been no equivalent to the attention devoted to the use of Pidgin by musicians, stand-up comics, and Internet users.

My purpose here is not to argue that Pidgin should be the language of Nollywood, but rather to shift the debate to recognize Pidgin’s central role as a binder in a polyglot multiethnic environment where people slide naturally from one language to another depending on context and where code switching (within a conversation) and code mixing (within a sentence) are endemic.

The history of Nollywood’s use of Pidgin runs parallel to the story of its rise outlined prior. The first video films entirely in Pidgin—comedies—appeared the same year (1994) as the first English-language Nollywood film. Jagua (Afolabi Afolayan), who had had a popular show on the NTA and who came out of the Yoruba Travelling Theatre tradition but was based in Jos, outside of Yorubaland, and so worked in Pidgin, made Devil’s Money, a comic take on the occult money-ritual theme. This is low comedy, set in a village full of foolishness and debility; it is an example of what Mikhail Bakhtin calls “the carnivalesque,” a popular form that emphasizes “the lower bodily stratum” and its desires and functions—a world of drunkenness, hunger, defecation, frank sexual desire, and grotesquely enlarged stomachs and buttocks. This crude fecundity is linked to a laughing acceptance of life that punctures refined pretentions and seriousness of any kind. Language is handled playfully as a material thing.52 All these characteristics are associated with Pidgin itself.

Lagos Na Wah!! (another film from 1994), advertised on its jacket as “Pidgin Comedy,” joined the forces of two leading troupes of television comedians, one Yoruba, playing native Lagosians, the other from the Igbo part of the country, cast as bewildered visitors to the metropolis. Again, the emphasis was on improvised fooling in a world of fools and sly tricksters. Pidgin was the natural language for interactions among lower-class characters from different ethnicities, and the linguistic play to which Pidgin lends itself was fully exploited. This comic tradition is still going strong: Lagos Real Fake Life, a direct descendant of Lagos Na Wah!!, made good money in the multiplexes in 2018.

But, outside the comic tradition, few films have been entirely in Pidgin. There is a strong analogy with the Nigerian novel, where some dialog in Pidgin is a routine feature—it would be nearly impossible to represent urban life realistically without it—but where novels written entirely in Pidgin are extremely rare. The narrative voice remains a bastion of Nigerian Standard English. This is surely one reason why Pidgin is underestimated as an element in film culture: it nearly always has a frame around it in a more respectable language.

But Pidgin turns up in many places, even in Violated (1996), Amaka Igwe’s sophisticated romance, whose extravagantly luxurious settings and psychological depth were designed to appeal to the Nigerian upper classes. But the heroine is working as a sales clerk when the film begins, and her work friends keep up an earthy, disabused commentary in Pidgin on her unfolding relationship with her Prince Charming. Films about cross-class romances continue to exploit Pidgin in this way, as in Kunle Afolayan’s Phone Swap (2012) and Tope Oshin’s New Money (2018).

Zeb Ejiro’s Domitilla: The Story of a Prostitute 1 and 2 (1996, 1998) represents both the use of Pidgin as a vehicle for the socially conscious exploration of the life of Lagos’s streets and the expression of the culture of the Niger Delta, Pidgin’s epicenter, from which the film’s heroine and her friends come. Recently, two of the most sensitive explorations of the dire situation of underprivileged youth in Lagos, Uduak-Obong Patrick’s Just Not Married (2016) and Ema Edosio Deelen’s Kasala! (2018), are, true to their settings, entirely in Pidgin or nearly so.

The new millennium brought a crop of new Nollywood genres,53 nearly all of which featured Pidgin. In crime films (like Chico Ejiro’s Outkast [2001]) and vigilante films (like Lancelot Imasuen’s Issakaba series [2000, 2001]), Pidgin is the natural language of criminals. In the genre of films about Nigerian emigrants struggling to establish themselves abroad (such as Goodbye New York [2004], Dollars from Germany [2004], The London Boy [2004], Toronto Connection [2007], and Europe by Road [2007]), Pidgin figures for several overlapping reasons: it is a pungent reminder of home and a bond between Nigerians of various ethnicities; forged in the slave trade and associated with poverty, Pidgin is also the language of hard times and the most direct expression of emotional need.

Those who can afford foreign visas and airfare are generally middle class, though usually they are shown being driven abroad by some kind of acute distress—if nothing else, the depressed economy—and, in the films, they always encounter harsh trials. Students at Nigerian universities are also predominantly middle class, and the genre of “campus films” devoted to their experiences (for example, Girls Hostel [2001], Campus Queen [2004], The Cat [2004], and Dangerous Angels [2010]) also invariably presents the campus as a harsh environment, dominated by “campus cults” (i.e., fraternities gone bad that violently organize social hierarchies, sexual predation, intimidation of faculty, and perhaps also prostitution, drug dealing, and robberies). University students are noted for their affection for Pidgin: never heard in lecture halls, it is the language of student hostels and (often) of faculty staff clubs. The population of students in Nigerian universities has continued to rise steeply, even as the extreme dysfunction of the educational system encourages radical perspectives. Pidgin is the language students use as a sign of toughness in their constant confrontations, in vying for social status, and for “gisting” (getting to the gist, the pith, or heart of something) with their roommates about their love lives. If English is the official language of lectures, readings, and exams, unofficial life in this modern and relatively de-ethnicized environment takes place in Pidgin (see figure 6.1).

This rough sketch of the history of Pidgin in Nollywood intersects at this point with the history of Pidgin’s rise from subaltern status to fashionableness, driven (as noted) in no small part by university students and graduates, and it intersects with the history of the transformations of Nollywood and its culture(s) by the intervention of formal capitalism. New Nollywood was based on the new multiplexes, which are disproportionately patronized by university graduates, and the later films sponsored by transnational corporations often represent professionals successfully adapted to the glossy dimension of the new world of transnational neoliberal capitalism.

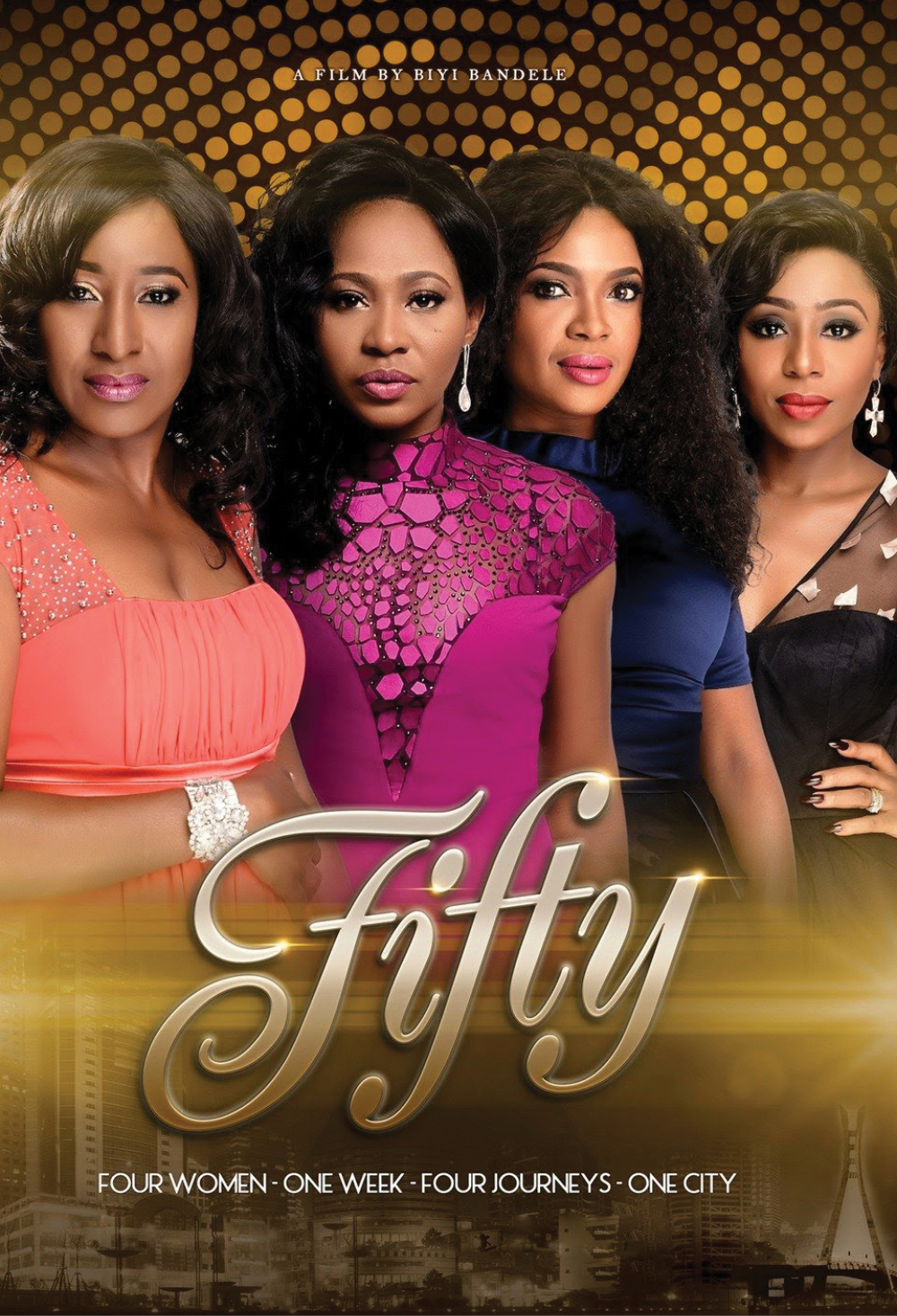

Code switching and code mixing are the order of the day in these films, even when they never leave the world of sophisticated privilege: the blockbuster Fifty (2015), a Sex and the City-style film about a group of women professionals approaching middle age, for example, is in English, Pidgin, Yoruba, and Igbo. Omoni Oboli’s Okafor’s Law (2016), another film about the sexual mores of prosperous Lagosians, centers on three extremely eligible bachelors who switch constantly from English to Pidgin, a habit linked to their friendship dating back to university.

Some of the most talented current younger directors have turned to the crime film (inspired by foreign directors ranging from Francis Ford Coppola and Quentin Tarantino to the Brazilian Fernando Meirelles) as a genre with which to present a panorama of Nigerian society held together by corruption, from low-life criminals to the heights of wealth and power. Walter Taylaur’s Gbomo Gbomo Express (2015) is in English and Pidgin as is Toka Mcbaror’s Merry Men: The Real Yoruba Demons (2108). Dare Olaitan’s Ojukokoro (Greed) (2016) and Kemi Adetiba’s King of Boys (2018) switch among English, Pidgin, Yoruba, and Hausa.

In her 2002 essay “English and the Audience of an African Popular Culture,” Moradewun Adejunmobi wrote that English-language Nollywood films represented not a particular Nigerian class or cultural fraction, but

This was a brilliantly insightful analysis of the situation when she wrote, and it remains true that a film in which wealthy people spoke entirely in Pidgin would be strange. But there has been a profound shift: sophisticated and affluent Nigerians are now eager to claim Pidgin as part of their repertoire.a sodality of social aspiration. The specific attraction of the films resides in their deployment of narratives of mobility that feed upon the anxieties and desires of disparate social groups seeking to rise beyond their present station in life… . If the producers had been merely seeking to communicate across ethnic and class lines, Pidgin would have sufficed for that purpose… . But … within the Nigerian imaginary, Pidgin retains its associations with illiteracy, poverty, and sexual license. English, on the other hand, operates as linguistic signifier of affluence in the popular arts… . In my opinion, a film about the well-to-do made entirely in Pidgin would be a contradiction in terms… . When the rich are represented in Nigerian texts, they are almost never imagined as speaking Pidgin.54

The Ghost and the Tout

Directed by Charles Uwagbai, The Ghost and the Tout (2018) has not been chosen as my central example because it is a masterpiece. Everything about the film reflects the persona of Toyin Abraham, who produced and cowrote it and plays the central character. She has typecast herself as a boisterous, crude, uneducated, irrepressible person—Pidginphone, naturally—who wreaks havoc around her. The filmmaking has the same slapdash manner characteristic of the low end of “old” Nollywood comedies. Abraham’s films generally get bad reviews because the reviewers are offended by their presence in the multiplex cinemas that are the preserve of the aspirational New Nollywood. But the Nigerian films that have made the most money in those theaters are evenly split between slickly crafted, high-budget, Hollywood-style blockbusters and broad (mostly Pidgin) comedies by the actress Funke Akindele, whose persona greatly resembles Abraham’s, and the stand-up comic AY Makun, who also expresses himself naturally in Pidgin. Abraham’s projects are a favorite investment for FilmOne, the biggest of the distributors serving the cinemas and a major investor in productions, because they cost a small fraction of the blockbusters. There is more filmmaking craft under the rough surface than meets the eye—enough that the film has been picked up by Netflix, which is the aspiration for many Nigerian film projects.

The story: Mike, a prosperous young Lagos businessman, is murdered in the street by hitmen and finds himself a ghost, looking on at the scene but not understanding who sent the killers. He wanders the streets, unseen and unable to communicate with anyone, until he bumps into Isila the tout, who alone can see and talk with him. The door to the supernatural was thrown open for her by an accidental encounter, as she was making her way home from her boyfriend’s, with masqueraders of the Yoruba Oro cult. (The Oro festival celebrates the patrilineage of a town, and women and outsiders are strictly forbidden to see its masquerades. Isila is suffering retribution for her transgression.) Mike pleads with (and then pays) Isila to act as intermediary with his fiancée Adunni, and together the ghost and the tout solve the mystery of who ordered his murder, after suspicion had fallen in various directions (see figure 6.4).

The ghost is in an intermediary relation between the worlds of the living and the dead; the tout is a professional intermediary in business transactions, a role that Isila extends to sticking her nose into everyone’s business in her community. But she is not at all eager to take on Mike’s assignment, as it requires her to be the intermediary between social classes, which makes her uncomfortable and does not go well: when trying to enter Adunni’s environment, she is repeatedly beaten up, dismissed as crazy, and hauled away by security men. She is at home in the “ghetto” (as it is called) while he is upper-middle class. Drone shots emphasize the contrast between her wedge of slum and the vast surrounding new development for the prosperous on the Lekki Peninsula of eastern Lagos.

Both settings are amply developed. In the ghetto, where people switch between Yoruba and Pidgin, the Oro masks are powerful but appear only fleetingly in this multiethnic, recently constructed settlement. We see much more of the community organization that is collecting funds for a modest neighborhood carnival. Many episodes demonstrate the contagion of rumor in the neighborhood, the gullibility that keeps fraudsters in business, the constant explosion of loud disputes—a vast reservoir of comic idiocy, among other things, but presented with genial familiarity and amusement. In presenting the hanging around that is the substance of social life, the production seems to be continuing the practice of the filmmaking tradition that descends from the Yoruba Travelling Theatre of casting everyone they know in bit parts, but in this case, the faces are not familiar from stage, film, or television appearances but from Instagram and other forms of social media—the fertile soil of the new grassroots.

Mike’s world is also multicultural. In repeated scenes, his father hurls Igbo proverbs at his Yoruba business associate; they are always shouting at one another but have been friends since secondary school. (In contrast to the Instagram-famous ghetto cast, the two men are played by iconic actors from the Nollywood and Yoruba film industries. Igbos are the second-largest ethnic group in Lagos, after the Yoruba.) Mike’s Igbo father married a Yoruba woman, of excellent character. She demands strict but gracious manners, including respect for social inferiors, from her daughter and is evidently the source of Mike’s own calm, quiet, balanced, intelligent, and generous bearing. These are the virtues of elders and kings, highly prized in Nigerian cultures, and a blessed relief from the chaotic noise generated by everyone else. Mike inherits an Igbo identity from his father, but his beautiful fiancée is Yoruba. Mike’s best friend is Yoruba but the friend’s fiancée is Igbo. (She distinguishes herself for her noisiness and jealousy, even in this film that is full of both things. The motorbike-mounted, stick-wielding posse of angry women she mobilizes to confront her boyfriend for his [incorrectly] suspected infidelity is one of the film’s memorable moments.) Mike the ghost is still Igbo, and Isila the tout is Yoruba. But she speaks Pidgin half the time. Much of the film’s comedy is generated around her deficiencies as an intermediary. Moody, distractible, garrulous, uneducated, and none too intelligent, her mind fractured to the verge of mental impairment, she is often opaque as a medium of communication. But she does get through.

Throughout the film, there are repeated appeals to the notion of family, community, and even the nation. In one incident in the ghetto, Isila tries to prevent an irate woman from beating her husband who is busy getting drunk; the woman slaps Isila, who is stunned for a second and then bursts into a rendition of the Nigerian national anthem followed by the declaration “We are one family.” “Don’t come between a couple,” is the reply she gets. When Adunni tells Isila that what they have undergone together has made them family, Isila rejects the idea out of hand: “We can never be family.” Of course Isila eventually bonds with Adunni and with Mike: this is a comedy, and things work out. (It’s also a romance—there are touching scenes of love and grief between Adunni and the invisible Mike—and it’s a melodrama, a murder mystery, a ghost story, and a social satire. This kind of genre mash-up has become common.) There is a hardheadedness in the film that keeps its sentimentality in check (see figure 6.5).

The drone shots that show the small ghetto surrounded by a sea of middle-class development invert the reality of Lagos, where two-thirds of the population works in the informal sector and lives in slum conditions on less than two dollars a day. Nigeria’s class problem becomes manageable, in the imagination, when presented in this way. Another suggestive image comes from the interior of Isila’s boyfriend’s place—a shack, with walls partly composed of a poster for an event cosponsored by FilmOne—The Ghost and the Tout’s distributor—the Ford Foundation, and the United States embassy. A self-reflexive in-joke, doubtless, but this also shows understanding that people do really shelter behind corporate refuse and perhaps makes a comment on how few degrees of separation there are between the elite and the masses.

The film is profoundly urban in the way essential plot points depend on accidental encounters—people bumping into one another on the street, being out when the masquerades appear, catching glimpses in a crowd. The city is a melting pot where ethnicities have bonded through generations of friendship and erotic love. (The realm of intimacy is where problems are generated: jealousy of one kind or another motivates most of the plot lines.) The class division is harder to overcome, and it is hardening, but the long history of social fluidity and mobility is not over.

As is often true in Nollywood films, there is little sign of political consciousness. This film also does not suggest a teleology or historical temporality. The classes have always been there; the ghetto does not represent “tradition” in spite of the Oro masquerade (the residents are much more excited about the advent of the iPhone 10, though the only one they actually see is a fake, with nothing inside of it—an emblem perhaps of the “modernity” of the periphery). The ghetto isn’t sentimentalized as something left behind because it hasn’t been left behind.

But the work of social integration is there to be done, and the film does it. When Nollywood first appeared, it was heralded as the voice of the grassroots. Can the subaltern make movies? This was always a simplification: university-educated, NTA-trained personnel were always an important part of the phenomenon. But it is deeply consequential that story ideas and the money to make these films often came out of the same informal markets where people went to buy the films—it was an expression by and for the masses. It is too much to say that The Ghost and the Tout’s point of view or social center of gravity are in the ghetto, or that anything is settled by the fact that Toyin Abraham, the film’s driving spirit, makes herself at home in the part of the ghetto heroine. Similarly, Pidgin is no guarantee of authenticity or a subaltern perspective: it has been coopted for advertising by predatory corporations and politicians. But the film culture of Nollywood’s early days is still alive in this film and so infuses it with vitality, with humor, with the power to express a popular vision, that it can’t be kept out of the air-conditioned multiplex theaters in the new Nigerian shopping malls, those nodes of transnational corporate capitalist consumption. The mall’s educated and affluent patrons speak Pidgin as part of their linguistic repertoire, thoroughly over the condescension of previous generations, because Pidgin is in them on the most intimate level and expresses their rootedness in a Nigerian national reality and national identity.

Notes

- UNICEF, “Nigeria: Education,” UNICEF, accessed January 7, 2020, https://www.unicef.org/nigeria/education. ⮭

- Basil Davidson, The Black Man’s Burden: Africa and the Curse of the Nation-State (London: James Currey, 1992). ⮭

- Obafemi Awolowo, The Path to Nigerian Freedom (London: Faber, 1947), 47–48. ⮭

- On “resource curse,” see Jeffrey Sachs and Andrew Warner, “The Curse of Natural Resources,” European Economic Review 45, no. 4–6 (2001): 827–38; on “kleptocracy,” see Stanislav Andreski, The African Predicament: A Study in the Pathology of Modernisation (London: Joseph, 1968); and on the “criminalization of the state,” see, Béatrice Hibou, Stephen Ellis, and Jean-François Bayart, The Criminalization of the State in Africa (New York: Oxford, 1999). ⮭

- James Ferguson, Global Shadows: Africa in the Neoliberal World Order (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006); and Charles Piot, Nostalgia for the Future: West Africa after the Cold War (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010). ⮭

- Segun Olusola, “Film-TV and the Arts—the African Experience,” in Mass Communication in Nigeria: A Book of Readings, ed. O. E. Nwuneli (Enugu: Fourth Dimension, 1986), 161–78; Oluyinka Esan, Nigerian Television: Fifty Years of Television in Africa (Princeton, NJ: AMV Publishing, 2009). ⮭

- Nicholas Faraclas, “Nigerian Pidgin,” in The Survey of Pidgin and Creole Languages, Volume I: English-based and Dutch-based Languages, ed. Susanne Michaelis, Philippe Maurer, Martin Haspelmath, and Magnus Huber (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013). ⮭

- Don Pedro Obaseki, “Nigerian Video as the ‘Child of Television,’ ” in Nollywood: The Video Phenomenon in Nigeria, ed. Pierre Barrot (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009), 72–76. ⮭

- Brian Larkin, “Degraded Images, Distorted Sounds: Nigerian Video and the Infrastructure of Piracy,” Public Culture 16, no. 2 (2004): 289–314. ⮭

- Biodun Jeyifo, The Yoruba Popular Travelling Theatre of Nigeria (Lagos: Nigeria Magazine, 1984); Karin Barber, “Popular Arts in Africa,” African Studies Review 30, no. 3 (1987): 1–78. ⮭

- Sometimes all three industries are lumped together as Nollywood; I believe many Yoruba filmmakers would not complain about this, but many Hausa filmmakers would. I use the term in the more restricted sense. On the early history and structure of the three industries, see Jonathan Haynes and Onookome Okome, “Evolving Popular Media: Nigerian Video Films,” Research in African Literatures 29, no. 3 (1998): 106–28; and Jonathan Haynes, Nollywood: The Creation of Nigerian Film Genres (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016). ⮭

- See Onookome Okome, “Nollywood and Its Critics,” in Viewing African Cinema in the Twenty-First Century, eds. Raul Austen and Mahir Saul (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2010), 26–41. ⮭

- Abdalla Uba Adamu, “Islam, Hausa Culture, and Censorship in Northern Nigerian Video Film,” in Viewing African Cinema in the Twenty-First Century, eds. Ralph Austen and Mahir Saul (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2010), 63–73; Carmen McCain, “Nollywood, Kannywood and a Decade of Hausa Film Censorship in Nigeria: 2001 to 2011,” in Silencing Cinema, eds. Daniel Biltereyst and Roel Vande Winkel (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), 223–40. ⮭

- Haynes, Nollywood, chapter 2. ⮭

- Abdullahi, Denja, “Teaching an Old Dog a New Trick: Reviewing Government’s Interventions in the Nollywood Industry,” paper presented at the Society of Nigerian Theatre Artists (SONTA) Annual International Conference, Abuja, August 2015, 2–3. ⮭

- Barclays Foubiri Ayakoroma, Trends in Nollywood: A Study of Selected Genres (Ibadan: Kraft Books, 2014), 76–78. ⮭

- Jade Miller, Nollywood Central (London: BFI/Palgrave, 2016). ⮭

- Alessandro Jedlowski, “African Media and the Corporate Takeover: Video Film Circulation in the Age of Neoliberal Transformations,” African Affairs 116, no. 465 (2017): 671–91. ⮭

- Jonathan Haynes, “Keeping Up: The Corporatization of Nollywood’s Economy and Paradigms for Studying African Screen Media,” Africa Today 64, no. 4 (2018): 3–29. ⮭

- For a more detailed description, see Haynes, “Keeping Up.” ⮭

- Moradewun Adejunmobi, “Evolving Nollywood Templates for Minor Transnational Film,” Black Camera 5, no. 2 (2014): 74–94; Connor Ryan, “New Nollywood: A Sketch of Nollywood’s Metropolitan New Style,” African Studies Review 58, no. 3 (2015): 55–76. ⮭

- Hyginus Ekwuazi, “The Perception/Reception of DSTV/Multichoice’s Africa Magic Channels by Selected Nigerian Audiences,” Journal of African Cinemas 6, no. 1 (2014): 21–48. ⮭

- Faraclas, “Nigerian Pidgin.” ⮭

- Ifechelobi, Jane Nkechi, and Chiagozie Uzoma Ifechelobi, “Beyond Barriers: The Changing Status of Nigerian Pidgin,” International Journal of Language and Literature 3, no.1 (June 2015): 213. ⮭

- Herbert Igboanusi, “Empowering Nigerian Pidgin: A Challenge for Status Planning?” World Englishes 27, no. 1 (2008): 68–82. ⮭

- See Igboanusi, “Empowering,” 69; Jenny Benjamin Inyang, “The Naija Language and the ‘Naija Languej Akademi’ as an Ideological Movement,” AFRREV LALIGENS: An International Journal of Language, Literature and Gender Studies 5, no. 2 (October 2016): 19. ⮭

- Charles C. Mann, “Language, Mass Communication, and National Development: The Role, Perceptions and Potential of Anglo-Nigerian Pidgin in the Nigerian Mass Media,” paper presented at the International Conference on Language in Development, Langkawi, Malaysia, July 1997, 7; Mafeni, B. “Nigerian Pidgin,” in The English Language in Africa, ed. J. Spencer (London: Longman, 1971), 99. ⮭

- Charles C. Mann, “Reviewing Ethnolinguistic Vitality: The Case of Anglo-Nigerian Pidgin,” Journal of Sociolinguistics 4, no. 3 (2000): 458–74. ⮭

- Barber, “Popular Arts.” ⮭

- Kelechukwu Uchechukwu Ihemere, “A Basic Description and Analytic Treatment of Noun Clauses in Nigerian Pidgin,” Nordic Journal of African Studies 15, no. 3 (2006): 299. ⮭

- Igboanusi, “Empowering.” ⮭

- Mann, “Language, Mass Communication,” 7. ⮭

- Rotimi Fasan, “ ‘Wetin Dey Happen?’ Wazobia, Popular Arts, and Nationhood,” Journal of African Cultural Studies 27, no. 1 (January 2015): 10–11. On Fela’s life and significance, see also Tejumola Olaniyan, Arrest the Music! Fela and His Rebel Art and Politics (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2004); and Sola Olorunyomi, Afrobeat! Fela and the Imagined Continent (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 2003). ⮭

- Yomi Kazeem, “How Pidgin English Became the Voice of International Media in West Africa,” Quartz Africa, September 6, 2018, https://qz.com/africa/1349143/why-pidgin-english-is-the-new-cool-for-foreign-media-in-west-africa/. ⮭

- Odirin Victor Abonyi, “Re-Visiting the National Language Question: the Nigerian Pidgin Nexus,” in Scholarship and Commitment: Essays in Honour of G. G. Darah, eds. Enajite Ojaruega and Peter Omoko (Lagos: Malthouse Press, 2018), 406. ⮭

- Akinmade Akande, “Code-Switching in Nigerian Hip-Hop Lyrics,” Language Matters 44, no. 1 (March 2013): 39–57. ⮭

- Ifechelobi, Nkechi, and Ifechelobi, “Beyond Barriers,” 214. ⮭

- Theresa Heyd and Christian Mair, “From Vernacular to Digital Ethnolinguistic Repertoire: The Case of Nigerian Pidgin,” in Indexing Authenticity, eds. Véronique Lacoste, Jakob Leimgruber, and Thiemo Breyer (Berlin, München, and Boston: De Gruyter, 2014), 251. ⮭

- Inyang, “The Naija Language.” ⮭

- Ihemere, “A Basic Description.” ⮭

- Nneka Umera-Okeke, “Still on the National Language Question: Can the Nigerian Pidgin (NP) Suffice?” Revue Africaine et Malgache de Recherche Scientifique 7, no. 1 (2018): 107. ⮭

- Inyang, quoting C. Mokwenye, “The Naija Laguage,” 19. ⮭

- Ifechelobi, Nkechi, and Ifechelobi, “Beyond Barriers,” 215. ⮭

- Faraclas, “Nigerian Pidgin.” ⮭

- Moradewun Adejunmobi, “English and the Audience of an African Popular Culture,” Cultural Critique 50 (2002), 74–103. ⮭

- Tunde Kelani, personal communication, Lagos, 2015. ⮭

- Rudolf P. Gaudio, “The Blackness of ‘Broken English,’ ” Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 21, no. 2 (2011): 230–46, 231. ⮭

- Rudolph P. Gaudio, “Pidgin Pride and Prejudice: Race, Gender and Stylistic Codeswitching in Nigerian Stand-Up Comedy,” In Routledge Companion to the Work of John R. Rickford, eds. Renée Blake and Isabelle Buchstaller, eds., (New York: Routledge, 2019), 331–39, 334. ⮭

- National Film and Video Censors Board, Film & Video Directory in Nigeria, vol. 3, eds. D. R. Gana and Clement D. Edekor (Abuja: National Film and Video Censors Board, 2006), 272–73. ⮭

- A classic early (1965) statement is Chinua Achebe, “The African Writer and the English Language,” in Gods and Soldiers: The Penguin Anthology of Contemporary African Writing, ed. Rob Spillman (New York: Penguin, 2009), 3–12; for a recent discussion, see James Tar Tsaaior, “Another Tower of Babel or a Future of Possibilities? The Language of Nollywood and the Politics of Cultural Communication in Postcolonial Nigeria,” in Nigerian Culture and the Idea of the Nation, eds. James Tar Tsaaior and Francoise Ugochukwu (London: Adonis & Abbey, 2017), 47–71. ⮭

- Adedun Emmanuel Adebayo, “The Sociolinguistics of a Nollywood Movie,” Journal of Global Analysis 1 (2010): 113–38. ⮭

- Mikhail Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1968). ⮭

- See Haynes, Nollywood, chapters 7–12. ⮭

- Adejunmobi, “English,” 85, 96, 100n16. ⮭

Author Biography

Jonathan Haynes is Professor Emeritus of English at Long Island University in Brooklyn, New York. His latest book is Nollywood: The Creation of Nigerian Film Genres (2016). He co-authored Cinema and Social Change in West Africa (with Onookome Okome, 1995) and edited Nigerian Video Films (1997). Educated at McGill and Yale Universities, he has also published two books on English Renaissance literature. He has been a Guggenheim Fellow and has held Fulbright research and teaching positions in Nigeria at the University of Nigeria-Nsukka, Ahmadu Bello University, the University of Ibadan, and the University of Lagos.