言之者无罪闻之者足以戒 (诗经·周南·关雎·序)

Do not blame the speaker, take note of his warning.

—Book of Songs, ca. 600 BC

Introduction

Storytelling is a fundamental human skill. It developed together with language and civilization and outlived the writing, print, and digital revolutions. Since public communication shifted from earlier established mass media to the Internet, and from professional performers to anybody who wishes to put themselves in front of a digital camera to share their story with an anonymous crowd, video-recorded advice on the art of storytelling has gone viral too. Countless TED, YouTube, and other social-media presentations explain what constitutes a good story, how it enchants and mobilizes, how good stories can be distinguished from bad stories, and why stories can sell almost everything to audiences, including disposable commodities, customer services, and fake news.1 Used wisely, stories unite and inspire people to act for the common good. They can effectively transmit moral values, offer solace and orientation in crises, disseminate calls for solidarity with disaster victims, or popularize scientific research results. Constructed foolishly or even with evil intentions, they can lead individuals and whole societies into a maelstrom of hatred, fanaticism, and escalating violence. This dangerous potential to stoke social antagonisms once again gains momentum today, in response to the increasingly destabilized world order brought about by such large-scale (non-)events as climate change, pandemic-sized diseases, the aggravating conflict between two superpowers on the geopolitical stage, the widening gap between the Global North and South, and many more symptoms of a global civilizational crisis.

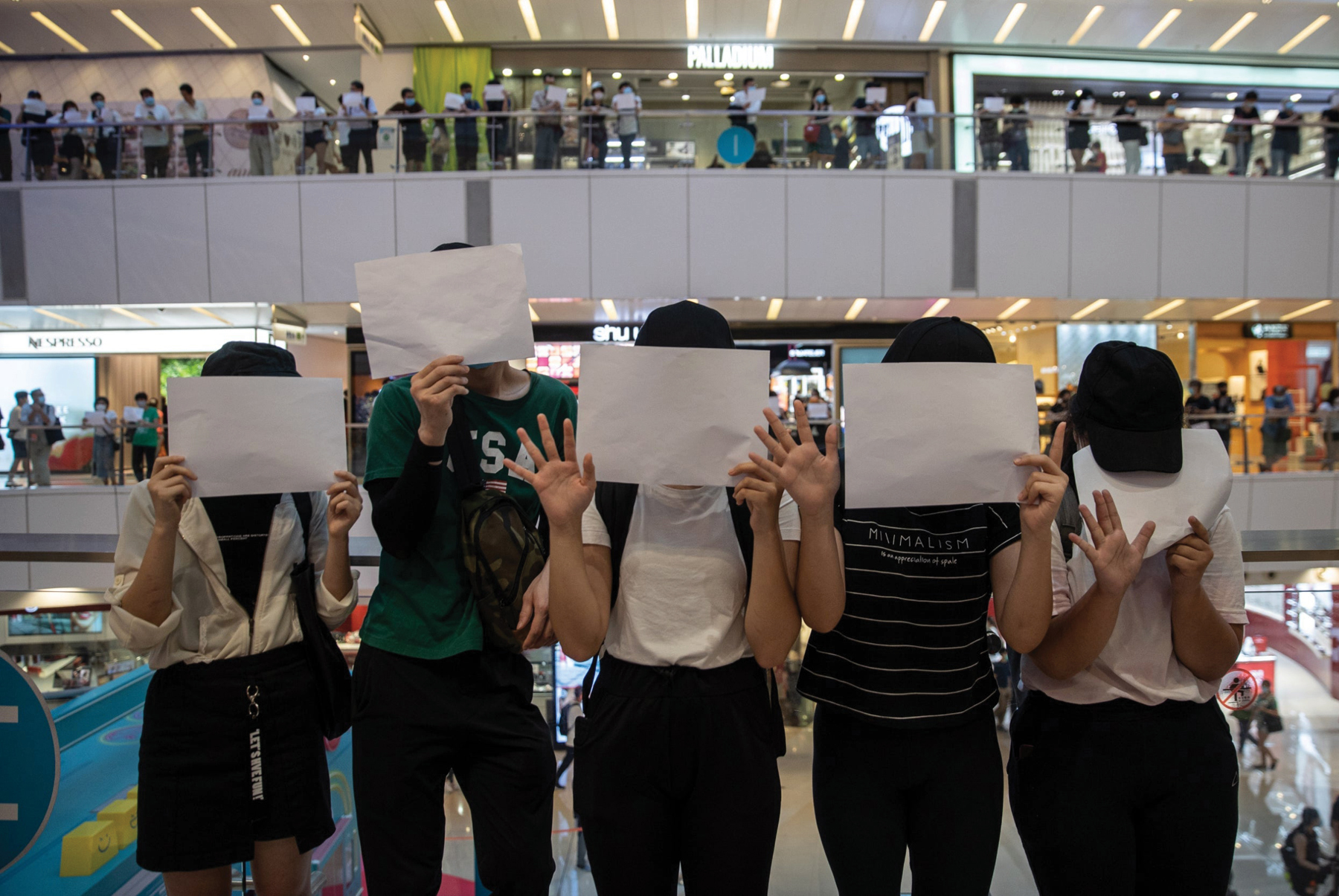

In the battle of narratives over Hong Kong’s recent problems, storytelling has also moved center stage. Old and young protesters take to the streets, sacrificing their private lives in order to proclaim their dream of a free and democratic Hong Kong. On the opposite side, officials handpicked by Beijing rather than democratically elected by the local people, and the Beijing leadership itself, are tightening their grip on the former British colony, thereby devaluing the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration’s formula of one country, two systems. Despite continuous lip service to Hong Kong’s special status, Beijing’s intent to abrogate its independent legal framework is manifesting with the new national security law for Hong Kong passed in Beijing on occasion of the annual session of the People’s National Congress in May 2020.2 Mainland social media celebrate the government’s uncompromising handling of the protests while accusing Western groups of illicit interference. Concomitantly, internal voices that criticize Beijing’s policy are instantly silenced.3 Originally tending to support the protesters, by now Hong Kong’s business elite mostly approve of the suppression of prodemocracy activism whereas critical observers insist that it is an unacceptable infringement of the joint declaration granting the city political and legal autonomy until 2046.4 Since January 2020, independent media diagnosed a fading out of protest vigor in the city upon the dispatch of new liaison office head Luo Huining, the Covid-19 outbreak, and the security law resolution. Despite these endgame calls, local activism goes on. It is changing dramatically, though, as Lisa Lim recently summarized in her description of the citizens’ turn toward symbols and performative acts meant to expose the growing walls of government-imposed silence. Lennon Walls with empty Post-It stickers across the territory, pictures of groups of protesters with blank sheets of paper covering their faces, and icons on graffiti and social media platforms testify to Beijing’s silencing policy, she argues. In her view, “Such erasure amplifies the message, giving voice to both what is being censored and the act of censorship”5.

In this paper, I will address the ramifications of Hong Kong’s story as inscribed within recent literary, visual, and multimedia-art productions related to the protests by focusing on some of the key concerns transpiring in them. Using Wong King Fai’s Umbrella Dance for Hong Kong,6 Samson Young’s sonic multimedia installations, street-art performance events, and other examples, I will address the turn from words and noise to silence in artistic storytelling projects. I am mostly concerned with the following questions: First, under what conditions can politically engaged literature and art fulfill the role of storytelling as communication and as a community-building device,7 and are these conditions given in Hong Kong’s present situation? Second, how are the differing truth claims articulated by grassroots storytellers (including the protest-supporting artists and intellectuals), institutional stakeholders, external observers, and others, and how can they be negotiated in an environment of growing mutual distrust? What is the role and function of storytelling in this aggravating conflict? And third, what kind of affective space is created and circulated in the various arenas where cultural articulation and performance take place? How do the involved aesthetic forms and stories develop over time? Deriving insights from various theories tackling storytelling, activism, and (politically engaged) art—among them postcolonial sound and affect studies—I will engage with embedded meanings across a variety of cultural forms and representations through qualitative analysis to gain deeper understanding of one of a growing number of democracy movements that currently experience increasing intolerance and violent suppression in authoritarian states. Despite my focus on cinematic and artistic storytelling, I will not delve into deep readings. Rather, I am interested in the shared tropes and affective intensities of the stories told and, therefore, will base my approach on discourse analysis similar to what is practiced in related interstitial disciplinary fields such as social anthropology and indigenous microhistory.8 I will contextualize the currently raging contest over Hong Kong storytellers’ interpretative rights with the evolving battle over global leadership among a declining and a rising world power, arguing that the mood and content of the stories told through its cultural producers change accordingly: from hope to despair, and from reconciliation to confrontation.

The Multiple Affordances of Storytelling

The narrative inauguration, dissemination, and rehearsal of a group’s shared values can be described as the core tasks of storytelling. Spiritual enlightenment, moral guidance, aesthetic pleasure, emotional balance, and longing for a better world are among the treasures a well-crafted story can provide. Adding to these, Anthony Nanson underscores the catalyst function of the storytelling imagination for tolerance and transformation, arguing that storytelling “brings people together, stimulates conversation, and thereby helps sustain community.”9 The stories about who we are, where we come from, and what we desire to become in the future determine a community’s collective imagination and can spur the spirit of shared destiny.10 Earlier in 1936, Walter Benjamin had critically reflected on the decline of oral storytelling, arguing that the type of slow cultural development accompanying oral communication was lost in industrialized societies. According to him, printed novels and mass-media-transmitted information have replaced the traditional storyteller’s wisdom. Consequently, modernity’s makers of history were often ill advised because the kind of counsel storytellers could offer—for instance, advice on how to act under the circumstances of a crisis—was no longer fashionable.11

Meanwhile, global capitalism has prompted an even less stable sociopolitical environment as mirrored in increasingly nervous cultural reverberations on the local plane. Its new mediascape stages a simulacrum of the ancient storytelling profession, wherein the world turns into an endless spectacle, while fake news and various kinds of crises and conspiracy tales threaten to annihilate the benign effects of this art like nothing before. Moreover, the widespread use of communication gadgets affords a new dimension of thought control and surveillance that by far exceeds the measures taken by totalitarian regimes in the past. Nanson argues that

Throughout the twentieth century, such ethical debates were relegated to the niches of noncommercial cultural production. Meanwhile, along with the formation of loosely organized local groups and larger institutionalized networks connecting socially engaged art and cultural activism across the globe, change seems afoot. Empowered by new forms, themes, and theories, emergent social movements have begun to incorporate oral storytelling techniques into their discourse in order to further their environmental, feminist, queer, social-justice, and other trajectories.13 These attempts to counter the ruling ideology and usher in alternative, less destructive worldviews are astutely outlined by Haraway in her collection of stories that advise how to “stay with the trouble”:in fast capitalism, products are produced and sold as rapidly as possible to reap as much profit as possible as fast as possible… . In their pursuit of maximum profit the corporate media forge a conformity of thought and fashion, a homogenizing blandness that is destroying traditional culture around the world and that sanctions mediocrity and ignorance… . The political nature of decision-making sinks out of view. The ideology of market economics is not seriously questioned outside the polders of academia and counterculture; it is simply accepted as the way the world is. The supremacy of that ideology thereby undermines the possibility of ethical debate about its social, environmental, and spiritual consequences.12

The origin of said trouble is human-induced environmental degradation, and her recipe for a morally and socially satisfying life is to reach out beyond the prevailing political structures, ideologies, and utopian dreams by actively engaging with the present through reconciliation with the material world at large or, in her words, to make kin with “all the oddkin.” On the sociopolitical plane, Hong Kong’s population has gathered invaluable experience with such a politics of reconciliation from below through negotiating and making trouble under the British colonial regime and thereafter. To protest creatively in pursuit of improvements for the community’s livelihood has been an essential strategy of enabling from below among the disenfranchised residents. Over time, it provided the unique cultural landscape of a place where, for a long period of time, the ruling elites considered aggressive promotion of business as the singular road toward prosperity and stability. Accompanying the recent escalation of dissent with Beijing’s emulation of this policy, the residents’ kin-making repertoire was enriched by new forms of community-centered art and environmental projects while the time-tested alternate rhythm of protesting and withdrawing is further developed and explicitly articulated in the “be water” tactics of various, loosely connected groups participating in the activities.15Our task is to make trouble, to stir up potent response to devastating events, as well as to settle troubled waters and rebuild quiet places. In urgent times, many of us are tempted to address trouble in terms of making an imagined future safe, of stopping something from happening that looms in the future, of clearing away the present and the past in order to make futures for coming generations. Staying with the trouble does not require such a relationship to times called the future. In fact, staying with the trouble requires learning to be truly present, not as a vanishing pivot between awful or edenic pasts and apocalyptic or salvific futures, but as mortal critters entwined in myriad unfinished configurations of places, times, matters, meanings.14

Storytelling In-between Worlds

Looking back at Hong Kong’s literary, filmic, and artistic production from the 1950s to today, multiple stories constitute the undercurrent of the periodically erupting local struggles for human rights and livability. No matter whether articulating nostalgia for the distant home in case of the early mainland refugees or worries about the erasure of the city’s history toward the end of the twentieth century and thereafter; whether temporarily escaping into the cinematographic dreamscapes of an imaginary Chinese empire or imagining the horrors of a dystopian future; whether addressing the city’s housing problems or the population’s anxieties in view of the 1997 handover, from the first wave of Mainland Chinese immigrants till now; a wealth of popular as well as highbrow literary, filmic, and other aesthetically packaged narratives pointed to these social issues while insisting on the legalization of citizen demands for active participation in their hometown’s cultural and sociopolitical design. The stories, especially when turned into the globally successful, culturally hybrid Hong Kong-style movies, have spurred the formation of a local spirit based on the wish to feel at home, build a community, and be one’s own master. Naturally, expectations were high when the 1984 joint declaration for what looked like a pathway to decolonization was signed—only to be shattered by the Beijing regime’s violent suppression of the 1989 Tiananmen student protests. Since then, yearly Tiananmen vigils, culture festivals, mass protests against unpopular policies, and many other forms of highly visible activism proliferated.16 To witness Hong Kong’s citizens’ eager political engagement for their city after the end of the colonial regime could have filled Beijing with pride and confidence. However, like Danny the Dog’s patron in Louis Leterrier’s movie Unleashed starring Jet Li,17 Mainland China’s officials tragically put their obsession with ownership above citizens’ hopes for the future.

The officially circulated Hong Kong stories on the other hand, no matter whether under British colonialism or thereafter, continued to stress the place’s miraculous economic success while painting the image of a happy, prosperous cosmopolitan community. Downplaying both regimes’ clashes with the local population, this master narrative perpetuates the colonial story of Hong Kong’s origins as a tiny fishing village awaiting first British development and then Chinese decolonization. Since 1997, Mainland Chinese officials took control over Hong Kong’s historiographic representation; for instance, by means of an exhibition at the Hong Kong Museum of History, which offered a grand narrative of the city’s smooth reunification with the homeland while glossing over the increasingly unpopular governance enacted by the post-handover chief executives.18

Underneath and beyond the master narratives, Hong Kong’s story was told from many different perspectives and in multiple affective keys. In his literary oeuvre, Lingnan University professor of literature and film studies, poet, and fiction writer Ping-kwan Leung (1949–2013) depicted a troubled yet at the same time enchanted city between worlds and forever in motion. He moreover cooperated with colleagues and friends in interdisciplinary cultural projects that successfully broke through the conventional storyline. In his view, cultural reconciliation would be the silver bullet to overcome the ideological gap between the Mainland and the postcolonial city, to be reached through fostering the two protagonists’ mutual understanding in full view of the different social, economic, and political background of the returned community. The 1989 Tiananmen incident exposed how narrow the space for dialogue had become, though, and Leung’s elegiac poems contemplate this tragic turn of events in a gloomy mood.19 However, he stubbornly continued to write poetry that clads the need for reconciliation into subtly humorous lyrical images of a tarnished yet indissoluble, intimate relationship. “Sushi for Two” (1997) is among the most well-known representing the latter type. A platter of sushi, shared by a couple of lovers whose relationship has grown tired over the years, offers the opportunity to contemplate their desires but also the grievances and lesions that contributed to their mutual estrangement. No matter what, the poem concludes, there is no other way than to continue negotiating in pursuit of whatever happiness may still be available under the circumstances:

In some of his post-Tiananmen works resignation prevails though. Reflecting on how to build and maintain a however makeshift home for oneself and one’s beloved, his “Conversation among the Ruins” (1994) transposes Giorgio de Chirico’s post–WWI painting into today’s Hong Kong. Resounding with Sylvia Plath’s poetic elegy on her broken relationship by the same title, this contemporary Hong Kong home is not an elegant mansion like hers but rather a modest place drummed up with “a few essential furnishings” and a “vestige of decorum,” where “the feeling of home” is only temporarily forged before the pillars gradually fall apart and everything inside and outside the room “dissolve[s] in the twilight.” In the end, nothing is left to remember, not even the couple’s just-finished conversation over dinner:When love is no more evening meals are mere consumption of matter/When home is no more maybe only the soul of clams will give shelter?/From different cities we came, with different winters behind us/We enjoy each other’s bright hues but what keeps us apart?/I chew slowly digesting your deep sea fibre/You go still in the noise as I melt on your tongue.20

Obviously, Leung’s restrained aesthetic reflections on the conflict, as well as his cautioning that Hong Kong’s story is difficult to tell, continue to be valid today. As the statistics provided by Marcelo Duhalde and Han Huang (2019) show, there is a continuity of public protest activities from the leftist, anticolonial riots in the late 1960s to the 2014 Occupy Central with Love and Peace (OCLP) movement and further up to the 2019 demonstrations. Their figures also indicate a dramatic upsurge of mobilized protesters since 2003.22From the very beginning, it has all come to this. I find myself flopped out in some hollow in the wilds, suit completely rumpled… . The bric-a-brac of a lifetime strewn among the ruins of old abodes, never to be retrieved… . Before it’s gone for good, I try to recollect our long conversation over the dinner table and I wonder: what was it we talked about?21

Subjected to Beijing’s two tales of one city—the official jubilant reunification theme and a semiofficial vituperating about the Hong Kong people’s enduring colonial contamination—the city found itself stuck between two sovereigns’ colonial and nationalist narratives. And whereas the British government had, if only to some modest extent, been responsive to negotiating with residents, events took a sharp turn when the post-handover regime began to implement its polarizing policy. Among the corrosive measures taken was a hotline pressuring Hongkongers to report on anyone taking part in a class boycott for universal suffrage in September 2014. According to Yiu-wai Chu, it resembled a cultural revolution-style action leading to the city’s community becoming even more uprooted and torn apart.23 Moreover, despite various efforts by the pro–Beijing political establishment to display their local engagement, nearly all critical decisions were ultimately made in China without much consideration for the residents’ opinion after the 1997 handover. In response, an increasing number of mostly low-budget films began to tell apocalyptic stories that painted a dark picture of Hong Kong’s declining institutions, economy, and local culture. Staging Hong Kong as a global neocolonial specter, these movies—among them Ten Years, The Midnight After, and Aberdeen24—forcefully convey residents’ growing anxiety. Hope for the future gave way to disillusionment and an atmosphere of morbidity.

From Distant Kin to Intimate Enemies

Meanwhile, the battle of narratives goes on. On August 13, 2019, when the Hong Kong antiextradition law protests had gone into their tenth week, a blogger in the People’s Daily recounted his experience with “Hong Kong’s trash youth” at Hong Kong International Airport, where he claims to have overheard a “foreigner” admonishing a young protester by whom he felt incommoded:

Adding that “the Hong Kong police already act with utmost restraint,” the Laowai’s (which literally translates as “foreign buddy”) words of wisdom, however, could not awaken the young protester to reason, the anonymous blogger laments. Calling his counterpart deviant, narrow-minded and irrational, he concludes by repeating the foreigner’s advice and adding his own words. Instead of making trouble and embarking on an evil path, the former should pursue a virtuous life.25 The disrespectful mode of the narrative echoes earlier voices from the mainland.26Hong Kong and Taiwan are part of China, this is publicly acknowledged by the world. If you need work, then go and look for work!

In an attempt to soothe this conflict, renowned Taiwanese writer and former culture minister Ying-tai Lung responded to the massive criticism of Hong Kong’s protesters by Chinese state media. On September 2, 2019, she wrote on Facebook:

Lung furthermore contextualized the “five demands” of the protesters—social equity, distributive justice, thorough implementation of the rule of law, government transparency, and full participation of citizens in the polity—with the core principles articulated in the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) constitution, arguing that these are identical with the protesters’ demands. In fact, they are all “commonly held values.” Rather than maligning Hongkongers as colonial collaborators and condemning them as unruly separatists or even “enemies of the nation,” Mainland China would therefore be better advised to learn more about Hong Kong’s complicated history and make an effort to understand, with a degree of humility, its citizens’ local attachments and concerns. Lung hints at the role of historiography when stating that a violent suppression of the protests would be remembered as Beijing’s betrayal of Hong Kong, not the other way around.28There is an egg, on the ground, in the garden. The fear of brute military suppression sits heavily on everyone’s mind. Each day it gets closer. And yet, many mainland Chinese view the protests in Hong Kong with scorn and derision, loudly sharing in the official critique. The violent tactics used by the protestors might prove to have been a grave strategic error, for which a heavy price will certainly be paid. But the masses of young people who have walked into the streets of Hong Kong in 2019 are not naïve. They know what kind of iron wall stands before them, and what puny, fragile eggs they are in the face of it. These teens and twenty-somethings know that when the moment for official reckoning arrives, their homes, their lives, their futures can all come to ruin.27

The Chinese state media response was hostile, accusing her of “deliberately sowing discord between mainland China and Hong Kong.”29 Evidently, the two parties were telling a different story of the protests. While the blogger claimed to tell his story in order to wake the protesters from their alleged sleep of unreason, the other advocated in favor of these same, asking those in power to listen carefully to the protesters’ claims and to develop a conciliatory attitude based on shared values and mutual understanding. Yet, they predictably both failed to reach their goals. Interestingly, the Taiwanese author’s story is more in accordance with the early CCP’s directives on handling contradictions among the people than the critical voices from today’s mainland. On May 1, 1957, a directive of the Central Committee of the CCP was issued in the People’s Daily. It offered advice on how to handle contradictions among the people. Using the ancient proverb quoted above, the text points out that

In historical hindsight, the 1950s leadership quickly abandoned its own principles, which leaves us worrying about modern Chinese history tragically repeating itself in Hong Kong. Meanwhile, the local stories continue to expose the extraordinary spirit of attunement of Hongkongers, which helped them cope with their complicated colonial situation. In the wake of the recent protests and Beijing’s increasingly unaccommodating reactions, however, their spirit of hope, tolerance, and reconciliation is giving way to narratives of anger or disillusionment. The picture of a street performance on Hong Kong Island in early December 2019 illustrates the increasingly poisoned “family affair” (see figure 2). The male actor is bringing home his bride by force, who is tied to a rope together with bricks and empty bottles. This hints at both China’s traditional patriarchal system and the western habit of tying noisy stuff to the newlyweds’ car so as to announce their happiness and bright future. The allegory of Hong Kong as the hapless token in an arranged marriage evokes memories of the fifth generation of Chinese directors’ focus on abused wives and concubines in their 1990s movies. What is different in the present street theater scene is its hybrid symbolism: without a vigilant civil society, modernity only repeats the old system’s oppressive patterns in new clothes, the scene suggests.when criticizing, or in dialogic conversation, one should encourage criticism, and resolutely implement to “allow everything that is known freely to be spoken out; do not blame the speaker and take note of the warning.” The principle of “change what needs to be corrected and encourage [the speaker who criticizes] if there is no such issue” must be applied correctly in order to not sweepingly affirm our own affairs and reject other people’s criticism.30

Sonic Histories

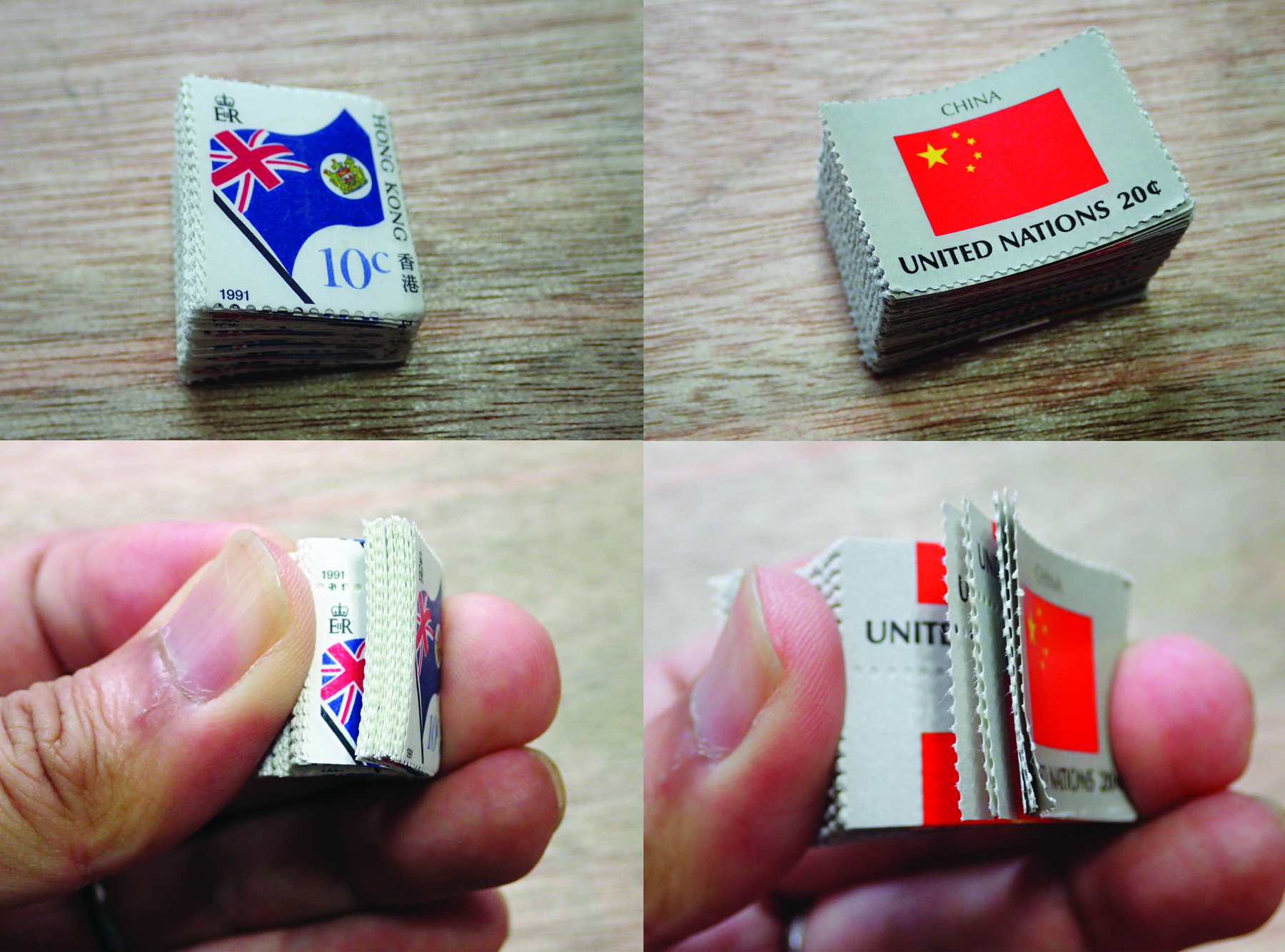

On occasion of the twentieth anniversary of the handover, curators at Karin Weber Gallery showed a 1997 immigrant’s letter sent from Australia to eight artists, inviting each of them to respond creatively to it. In the handwritten text, the refugee describes his new life as free but lacking the emotional comfort of being with his friends who had stayed behind. The resulting exhibition titled Composing Stories with Fragments of Time centers around messages having become partly illegible; for instance, because words (and narrative images) are missing or randomly reassembled.31. The exhibition thus offers a haptic escape route by equaling the passing of time with the rapidly receding scripts and sounds of diverse experiences of displacement and exile. Art critic Yeung Yang interprets the artists’ multisensory representations as successful efforts to sideline the “grand narratives of history in favor of an intimate, all-too-human encounter.”32To follow Rey Chow’s astute comments on the materiality and elusive character of sound, the aesthetic experience was thus extended beyond visual appeal and verbal communication, stimulating “acousmatic listening” to the letter writer’s absent voice.33 Absent sound was also invoked in Luke Ching’s allusion to John Lennon’s 1971 song “Imagine.” His installation titled Imagine There’s No Countries, Imagine There’s No Heaven, comprised, for example, a pile of blank envelopes with a sunken well holding flip books with stamps from the colonial era (see figure 3).

Reflecting on this turn to the as yet unspecified, or unidentified, aspects of chronotopic configurations, Yang draws attention to a third, frequently muted aesthetic category beyond the eye and the ear, the tactile sense,34 suggesting that “sometimes, one doesn’t have to rely on knowledge to be touched; to know, however, is to be touched differently.”35 It is precisely this embodied knowledge affording audiences “to be touched differently” that is seen to be endangered among Hong Kong’s artists and activists.

Likewise, the acousmatic aspects of storytelling—the presence, or conspicuous absence, of sounds whose origin is concealed—were foregrounded in an earlier performance on occasion of Germany’s Weimar Art Festival. One Sound of the Histories (2015) by Isaac Chong Wai, a Berlin-based artist from Hong Kong, united international participants in each telling his or her story simultaneously, and in their chosen language, on Weimarplatz.36 The resulting “white noise” uncannily resounded with the historical inscriptions of Weimarplatz (renamed Jorge-Semprun-Platz in 2017), where not long before, the fascist and socialist regimes had successively produced dark political meanings. Employing Henri Lefebvre’s threefold concept of space, and considering the geohistorical background of the artist, Liza Kam and Wing Man argue that the art performance on this location has something in common with the protest movement against the demolition of Hong Kong’s Star Ferry and Queen’s Piers in 2006 and 2007 and the ensuing developmental megaprojects. The similarly uneasy reckoning with the colonial inscriptions of Edinburgh Place, as articulated in one of the activist projects that collected grassroots memories connected to the place, did not prevent Hong Kong’s city planning bureaucracy from destroying the last remaining architectural signs of the city’s past (roughly) one and a half centuries. Connecting the buildings with their childhood, and thus demonstrating how lived urban space exceeds one particular time-space configuration and its political appropriations, the interviewees revealed their intense nostalgic feelings. In the eyes of citizens, the demolition was therefore not an act of decolonization but rather followed the government’s cold developmentalist logic.37

If the aforementioned art works question and complicate the national historical master narrative, statistical figures may not fare any better—even if produced outside the interest-driven discourse of governments. For example, the discrepancy, and hence unreliability, of the number of broadcasted protest-march participants is exemplified by Marcelo Duhalde and Han Huang in their comparison of official and unofficial statistics.38 Yet, even the alluring audiovisual protest happenings orchestrated by local cultural celebrities and anonymous street artists alike were prone to misappropriations. The latter’s impromptu art—among them the icons of the 2014 protest movement: protest anthem,39 Lennon Wall, and Umbrella Man40—have positively surprised the world with their creativity and determination to bring about peaceful change. Nonetheless, even the most catchpenny stagings of public protest were inadvertently rendered toothless when encountering a well-meaning yet corrosive media publicity; for instance, by tourist guide Lonely Planet’s advertisement of Hong Kong’s protest scene as a colorful spectacle worth visiting in its “Top 10 cities for 2012” edition.41 Reporting on the Lonely Planet’s 2012 choice of places to go, CNN Travel offered a sunny ocean view picture accompanied by the unaffected catchphrase: “As Hong Kong protesters demand more democracy, enjoy the view from the harbour.”42 While the tourist industry’s lobbying may have attracted affluent cosmopolitan travelers from across the globe, its blurring of global consumer spectacle and local activism fraught with personal risk was not necessarily helpful amidst the mounting unrest in the city.43

By highlighting the people’s grief and suffering in the escalating conflict, King Fai Wong’s award-winning video Umbrella Dance for Hong Kong eschews such misreadings. Focusing on sound, color, and movement, it features choreographer and dancer Cheuk Yin Mui’s dance performance with a traditional Chinese umbrella. The film’s polyphonic, wordless storytelling provides a profoundly sensual, aesthetic abstraction that successfully evades diverted interpretations of the protests by either the political establishment’s denunciation or commercial spectacularization. The dancer tells her story of the protests as a beautiful dream that quickly turns into a nightmare. From there, the camera travels with her into an empty, brightly lit space symbolizing suspense between death and transcendence. The opening, fast-forward shot of people gathering in the streets, many of them with umbrellas, is underlaid with the sound of church bells ringing, as if calling them to mass. While the bells continue to ring, a cut leads onto a dark space with what looks like a card box opening, from where Mui enters the scene. In front of her, a heap of white paper flakes. They cover the umbrella she finally spots while excitedly scooping up handfuls of flakes and sending them into the air in wave-like movements. At this moment, Hin Yan Wong’s musical arrangement44 seeps into the bell sounds and gradually takes over. After all flakes have been sent floating, the closed umbrella is picked up by the dancer. In a slow gesture lasting twenty seconds (minutes 2:50 to 3:10), the dancer closes the umbrella while pointing its tip toward the camera lens for viewers to appreciate its shape of a flower—a hint at Hong Kong’s local emblem, the bauhinia flower.

Next, she finds herself standing in front of street barriers. The background scenery of open umbrellas and police awakens to life, and the police who at first appeared in their regular blue uniforms are, from minute 4:42 onward, wearing riot gear. A sign with the message “Warning Tear Smoke” arises from the midst of the police blockage at minute 5:37, while Wong’s voice intonates a wordless, elegiac melody. Smoke enters the scene at minute 6:06, quickly filling the whole screen (see figures 4 and 5).

By this time, the dancer is no longer on her feet but performing in bent, sitting, and crawling movements until she lies still on the flake-covered ground, seemingly defeated, umbrella by her side (minute 7:40). Upon this, she enters another realm indicated by the smoke’s dissolution in soft back lighting that surrounds her upper body and upheld umbrella like a halo at minute 12:27, and the background scenery starts shifting to and fro between the real—marked by police, demonstrating people, umbrellas, and street barricades—and a dreamlike, dark empty space. As Mui slowly raises her umbrella, the music softens and the real and dreamlike backgrounds melt and collapse into each other, producing kaleidoscopic patterns into which the swirling umbrella poetically immerses itself. At minute 13:30, the camera abruptly shifts to the Hong Kong skyline by night seen from above, and from there down to the people in the streets. They pierce the darkness with their cellphone flashlights and perform human chains on a public screen while the camera passes by them. By the end of the performance, the camera’s gaze rests on the umbrella spinning unhurriedly on the ground, as if moving by its own intent.

Despite its elegiac tune, the video’s wordless, intensely poetic dramaturgy relies upon a restrained, contemplative mood. The final scene presents the dissolution of the violent real into a colorful dance of mirrored fragments and shadows and then moves further into the aimless, detached gesture of the spinning umbrella. This ending hints at a different temporality beyond the historical past/s and lived present. Neither utopian, nor hopeless, Wong’s main protagonist Mui “stays with the trouble,” to use Donna Haraway’s formula, by engaging with the real and indeed aesthetically sublimating it. Supported by the video’s composition in sober colors laid out in a liminal space between dream and death, Mui’s umbrella dance counteracts the noisy mode of the street protests while endorsing Hongkongers’ peaceful struggle for civil rights and at the same time mourning the victims. In an essay on Mui written in 2004, Ping-kwan Leung had praised her dialogic fusion of traditional Chinese folk dance with contemporary experimental forms.45 Fifteen years later, the director of Umbrella Dance for Hong Kong summoned Mui’s transcultural art to engage the world in the city’s struggle for democracy. The cinematographic call for action merges aesthetic pursuits and political gestures, which is transmitted in the cover image showing Mui and her defiantly upheld umbrella in front of the peaceful demonstrators (see figure 6).

Sonic artist Samson Young, in his multimedia art installations, addresses the contradictions of protest art by actively involving audiences in the performance.46 His compositions foster critical reflection by means of foregrounding the hidden ideological operations of music and seek social reconciliation by working with the members of oppositional political factions. For his 2017 Venice Biennale creation Songs for Disaster Relief,47 he invited the Hong Kong Federation of Trade Unions’ (HKFTU) Kwan Sing Choir to take part. Though belonging to the pro–Beijing camp, the HKFTU choir eagerly agreed to coproduce Young’s muted rendition of the charity song “We Are the World.” All that is left in the recording is agitated whisper.48 Satisfied with his aesthetic criticism of the charity industry’s compromising of music, he was moreover positively surprised by the success of his “reaching across the aisles.”49 In a similar vein, he performed birds’ voices in an exhibition hall standing on a scaffold-like structure high above visitors in an installation titled Canon (2015–2016) wearing the colonial khaki uniform used by the Hong Kong police before blue uniforms were introduced in 2004. His nature-mimicking twittering questioned the anthropocentric approach of global art fares while also critically engaging with the contradictions of state violence as represented by the transitional uniform and his long-range acoustic device (LRAD) stick—a sonic weapon of crowd control that is also used to deter wildlife from entering human security zones.50 Therefore, Young’s contribution to the Hong Kong story is at least threefold: it provides a fresh angle on musical performance and its ties to local community life, encourages the rapprochement of different ideological camps, and uncouples sound from music while underscoring its historical and geopolitical connectivities. If Simon and Garfunkel’s “Bridge Over Troubled Water” (1970)51 could inspire a Cantonese charity song version (1991), and the Cantonese charity song version inspired Samson Young to interrogate the global charity industry, then maybe the various emergent narrative and performative experiments with (re)telling Hong Kong’s story without words can also help to solve the present storytellers’ predicament—while resonating with Simon and Garfunkel’s “Sounds of Silence” (1966).52

Conclusion: Silent Hong Kong

On occasion of the new national security law for Hong Kong, local and international media warned that this would be the end of Hong Kong. Simultaneously, messages from concerned artists and cultural workers alerting to the city’s impending cultural erasure appeared, uncannily resonating with Rachel Carson’s warnings about species extinction due to the agroindustrial overuse of toxic substances.53 Even until today, her evocation of future spring seasons without birdsong has not lost its power, inspiring environmental movements across the globe. In a similar vein, the decline of Hong Kong’s local film industry was commented on melancholically as a case of cultural extinction. Fruit Chan’s The Midnight After was advertised with the tagline of “Hong Kong was lost overnight”54 whereas Ho-cheung Pang declared that his film Aberdeen, though also featuring symbols of death, was not about the end but “the beginning of the Hong Kong story.”55 On December 16, 2019, New York-based playwright Stefani Kuo published a video in response to the increasingly violent police actions against protesters in her hometown. Pleading to America for support, she describes how she imagines herself dying as one of the movement’s victims in Hong Kong’s streets while her father at home apologizes to the authorities for her misconduct as a protester.56 Maybe the city’s cultural survival is hanging by a thread but its citizens are determined to save their hometown. Even in the face of the failed dialogue leading to escalating state and protest violence, there are many literary, filmic, and art representations that convey hope that Hong Kong will be given another chance to reinvent itself from below.

In an essay on Samson Young’s installation Songs for Disaster Relief, Yeung Yang muses on the meanings of honor and hope in our age of compromised humanitarianism.57 In her view, the installation’s neon lights resonate with Henry Giroux’s concept of educated hope that not just envisions different histories but also different futures:

So long as Hong Kong’s fragmented, hybridized, muted histories continue to be told by its independent cultural producers, the future has not yet died. Multifarious aesthetic experiments with the amplitudes of discourse show that new narratives can be forged despite the narrowing space for public resistance. Attesting to Ferguson’s argument about the multiple political functionalities of resistant silence,59 the city seems to be staggering at the crossroads between the silence of death and extinction and the one foreboding a new beginning. Many of its residents are visionaries of alternative forms of kin making, among them environmental activists60 and queer Sinophone communities61 who passionately participate in this moment’s departure. As the world sympathizes with their peaceful, art-inspired forms of resistance, it is to be hoped that a window of opportunity for dialogic reconciliation will open somewhere along the long march for democratic reforms so that the multiple reiterations of Bartleby’s formula of “I would prefer not to” have a chance not to be the end but the beginning of a new story.Hope is … a pedagogical and performative practice that provides the foundation for enabling human beings to learn about their potential as moral and civic agents. Hope is the outcome of those educational practices and struggles… . Educated hope is a subversive force when it pluralizes politics by opening up a space for dissent, making authority accountable, and becoming an activating presence in promoting social transformation.58

Notes

- David J. P. Phillips, “The Magical Science of Storytelling,” TEDx Talks Stockholm, March 16, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nj-hdQMa3uA; Susan Duncan, “The Dark Side of Storytelling,” TED@State Street, Boston, November 2015, https://www.ted.com/talks/suzanne_duncan_the_dark_side_of_storytelling; Andrew Stanton, “The Clues to a Great Story,” TED 2012, Feburary 2012, https://www.ted.com/talks/andrew_stanton_the_clues_to_a_great_story?language=en. ⮭

- Yen Nee Lee, “China Approves Controversial National Security Bill for Hong Kong,” CNBC, May, 28, 2020, https://www.cnbc.com/2020/05/28/china-approves-proposal-to-impose-national-security-law-in-hong-kong.html. ⮭

- Javier C. Hernández, “China Deploys Propaganda Machine to Defend Move against Hong Kong.” New York Times, May 23, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/23/world/asia/china-hong-kong-propaganda.html. ⮭

- Shirley Zhao, “Hong Kong Media Tycoon Jimmy Lai Says Businesses Kowtowing to Beijing,” Bloomberg News, June 4, 2020, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-06-04/hong-kong-media-tycoon-says-businesses-kowtowing-to-beijing. ⮭

- Lisa Lim, “When Silence Speaks Louder than Words—in Hong Kong, Blank Post-Its and Pages Used to Convey Meaning,” South China Morning Post, July 21, 2020, https://www.scmp.com/magazines/post-magazine/short-reads/article/3093432/when-silence-speaks-louder-words-hong-kong. ⮭

- King Fai Wong, Umbrella Dance for Hong Kong, choreography by Chuek Yin Mui, Hong Kong, 2019. ⮭

- Anthony Nanson, Words of Re-Enchantment: Writings on Storytelling, Myth, and Ecological Desire (Stroud: Awen Publications, 2011). ⮭

- Don Kalb and Herman Tak, eds., Critical Junctions: Anthropology and History beyond the Cultural Turn (New York and Oxford: Berghahn, 2005). ⮭

- Nanson, Words of Re-Enchantment, 79. ⮭

- Nanson, 85. ⮭

- Walter Benjamin, The Storyteller: Essays (New York: New York Review of Books, 2019), 61–84 (ebook edition). ⮭

- Nanson, Words of Re-Enchantment, 107. ⮭

- Donatella Della Porta and Mario Diani, eds., The Oxford Handbook of Social Movements (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199678402.001.0001. ⮭

- Donna Jeanne Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), 1. ⮭

- See, among others, Edmund W. Cheng, “Street Politics in a Hybrid Regime: The Diffusion of Political Activism in Post-Colonial Hong Kong,” China Quarterly 226 (June 2016): 383–406, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741016000394; Stéphanie Cheung, “Taking Part: Participatory Art and the Emerging Civil Society in Hong Kong,” World Art 5, no. 1 (January 2, 2015): 143–66, https://doi.org/10.1080/21500894.2015.1016584; Pei-yi Lu and Phoebe Wong, “Art/Movement as a Public Platform: Artistic Creations in the Sunflower Movement and the Umbrella Movement,” in Art and the City: Worlding the Discussion Through a Critical Artscape, ed. Jason Luger and Julie Ren (London; New York: Taylor & Francis, 2017), 52–56; Tai-lok Lui, Stephen W. K. Chiu, and Ray Yep, eds., Routledge Handbook of Contemporary Hong Kong (London: Routledge, 2019); Yau Wen, Performing Identities: Performative Practices in Post-Handover Hong Kong Art & Activism (PhD thesis, Hong Kong Baptist University, Hong Kong,, 2018), https://issuu.com/wenyau/docs/thesis_whole_print_a5_issuu; and Winnie L. M. Yee, “Contemplating Land: An Ecocritique of Hong Kong,” in Chinese Environmental Humanities: Practices of Environing at the Margins, ed. Chia-ju Chang (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan Springer, 2019), 271–88. ⮭

- Lui, Chiu, and Yep, Routledge Handbook of Contemporary Hong Kong. ⮭

- Louis Leterrier, dir., Unleashed (in French: Danny the Dog; France, UK, and USA: EuropaCorp, 2005). ⮭

- Chu, Found in Transition; Wu, Reconfiguring Colonial Local Relations, 1–7, passim. ⮭

- See Leung in Mary Shuk-han Wong and Betty Ng, eds., Leung Ping Kwan, A Retrospective 回看, 也斯: 1949–2013 (Hong Kong: Leisure and Cultural Services Department, 2014), 92–113. ⮭

- Ping-kwan Leung, “Sushi for Two,” in Travelling with a Bitter Melon: Selected Poems (1973–1998), ed Martha Cheung, trans. Martha Cheung and Ping-kwan Leung (Hong Kong: Asia 2000, 2000), 249. ⮭

- Ping-kwan Leung, “Conversation among the Ruins,” trans. Jennifer Feeley, in Leung Ping Kwan, A Retrospective, 149. ⮭

- See also Cheng, “Street Politics.” ⮭

- Chu, Found in Transition, 39–40. ⮭

- Zune Kwok, Fei-pang Wong, Jevons Au, Kwun-Wai Chow, Ka-leung Ng, dir., Ten Years (Hong Kong: Ten Years Studio, 2015); Fruit Chan, dir., The Midnight After (Hong Kong: One Ninety Films, 2014); Ho-cheung Pang, dir., Aberdeen (Hong Kong: Sun Entertainment Culture, 2014). On the impact of Ten Years, see Karen Fang, “Ten Years: What Happened to the Filmmakers behind the Dystopian Hong Kong Indy Film?” Hong Kong Free Press, July 10, 2017, https://hongkongfp.com/2017/07/10/ten-years-happened-filmmakers-behind-dystopian-hong-kong-indy-film/; and Helena Yuen-wai Wu, “Reconfiguring Colonial Local Relations through Things, Places and Bodies in Hong Kong Culture and Society” (PhD thesis, Faculty of Arts, Institute of Asian and Oriental Studies, Zürich, 2019), https://www.zora.uzh.ch/id/eprint/174131. ⮭

- People’s Daily (blog), “The Trash Youth That Refuses to Wake Up,” (人民微评:叫不醒的废青), Sohu, August 13, 2019, http://www.sohu.com/a/333375376_260616. ⮭

- Jonathan Watts reports on the conflict, quoting Peking University professor Qingdong Kong who, in an interview, called Hong Kong protesters bastards, thieves, and dogs of the British Imperialists. See Jonathan Watts, “Chinese Professor Calls Hong Kong Residents ‘Dogs of British Imperialists,’ ” The Guardian, January 24, 2012, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2012/jan/24/chinese-professor-hong-kong-dogs. See also Yiu-wai Chu, Found in Transition: Hong Kong Studies in the Age of China (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2018), 29. ⮭

- YingtaiLung, “To Suppress Hongkongers with Military Force Is to Forsake Hong Kong,” Epoch Times, September 5, 2019, http://www.epochtimes.com/gb/19/9/4/n11499276.htm; English translation by Eileen Cheng-yin Chow, “ ‘The Greatness of a Great Nation Cannot Come Only From Missiles’: Lung Yingtai on the Hong Kong Protests,” Los Angeles Review of Books (blog), October 1, 2019, https://blog.lareviewofbooks.org/essays/greatness-great-nation-come-missiles-lung-ying-tai-hong-kong-protests/. ⮭

- Lung, “To Suppress Hongkongers.” ⮭

- Lung. ⮭

- “Directive of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on the Rectification Movement” (中国共产党中央委员会关于整风ff动的指示), Renmin Ribao, Beijing, May 1, 1957. ⮭

- Enid Tsui, “Hong Kong Handover-Themed Exhibitions Give Voice to Artists,” South China Morning Post, July 4, 2017, https://www.scmp.com/culture/arts-entertainment/article/2101207/hong-kong-handover-themed-exhibitions-give-artists ⮭

- Yeung Yang, “Composing Stories with Fragments of Time—Eight Hong Kong Artists’ Intimate Response to 20 Years of Changes,” COBO Social, August 1, 2017, https://www.cobosocial.com/dossiers/composing-stories-with-fragments-of-time-eight-hong-kong-artists-intimate-response-to-20-years-of-changes/. ⮭

- Rey Chow, “Listening after ‘Acousmaticity,’ ” in Sound Objects, eds. James A. Steintrager and Rey Chow (Durham, NC, and London: Duke University Press, 2019), 113–29. ⮭

- Pablo Maurette, The Forgotten Sense: Meditations on Touch (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018). ⮭

- Yang, “Composing Stories with Fragments.” ⮭

- Isaac Wai Chong, “One Sound of the Histories,” ArtAsiaPacific Almanac 11 (2016): 241. ⮭

- Liza Kam and Wing Man, “Artistic Activism as Essential Threshold from the ‘Peaceful, Rational, Non-violence’ Demonstrations towards Revolution: Social Actions in Hong Kong in the Pre-Umbrella Movement Era,” Art and the City: Worlding the Discussion through a Critical Artscape, eds. Jason Luger and Julie Ren (New York: Routledge, 2017), 115–27. ⮭

- Marcelo Duhalde and Han Huang, “History of Hong Kong Protests: Riots, Rallies and Brollies,” South China Morning Post, July 4, 2019, https://multimedia.scmp.com/infographics/news/hong-kong/article/3016815/hong-kong-protest-city/index.html?src=social. ⮭

- “ ‘Glory to Hong Kong’: Hundreds Gather to Sing ‘Protest Anthem,’ ” The Guardian, September 11, 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lEhgTBQX2kU. ⮭

- Ivan Watson, Pamela Boykoff, and Vivian Kam, “Street Becomes Canvas for ‘Silent Protest’ in Hong Kong,” CNN, November 11, 2014, https://edition.cnn.com/2014/10/08/world/asia/hong-kong-protest-art/index.html. ⮭

- Antony Dapiran, City of Protest: A Recent History of Dissent in Hong Kong (Melbourne: Penguin Specials, 2017), 5. ⮭

- Jane Leung, “Best Cities to Travel to in 2012,” CNN, November 3, 2011, http://travel.cnn.com/explorations/escape/lonely-planet-best-cities-travel-2012–716747/. ⮭

- Ming-sho Ho, Challenging Beijing’s Mandate of Heaven: Taiwan’s Sunflower Movement and Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2019), 188–90. See also Hong Kong Free Press, “Video: In Full—The Dramatic ‘Fishball Revolution’ Clashes as They Unfolded,” Hong Kong Free Press, February 10, 2016, https://hongkongfp.com/2016/02/10/video-in-full-and-uncut-the-dramatic-fishball-revolution-clashes-as-they-unfolded/. ⮭

- Rive Gauche, “7° FFCF—L’angolo degli Autori—‘Umbrella Dance for Hong Kong,’ ” Firenze Filmcorti Festival, accessed June 13, 2020, https://firenzefilmcortifestival.com/7-ffcf-langolo-degli-autori-umbrella-dance-for-hong-kong/. ⮭

- Ye Si (Ping-kwan Leung), Ye Si kan Xianggang 也斯看香港 (Hong Kong in Ye Si’s eyes) (Guangzhou: Huacheng chubanshe, 2011), 153–57. ⮭

- Claire Bishop, Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship (London and New York: Verso Books, 2012). ⮭

- Kwok Ying, “Curatorial Statement,” westKowloon, accessed June 14, 2020, https://www.westkowloon.hk/en/songsfordisasterrelief/curatorial-statement-2272. See also Hili Perlson, “Samson Young to Represent Hong Kong in Venice,” artnet News, July 14, 2016, https://news.artnet.com/art-world/samson-young-represent-hong-kong-2017-venice-biennale-557369. ⮭

- Samson Young, “We Are the World, as performed by the HK Federation of Trade Unions Choir (Muted Situation #21),” This Music Is False, 2017, https://www.thismusicisfalse.com/we-are-the-world. ⮭

- Andrew Nunes, “You’ll Never Hear ‘We Are the World’ the Same Way: ‘Songs for Disaster Relief’ Takes Aim at Charity Singles,” Vice, July 11, 2017, https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/bjxd85/samson-young-we-are-the-world-hong-kong-biennale. ⮭

- CoBo, “Samson Young’s Canon Performance at Art Basel Unlimited,” YouTube, June 17, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=foDd_DPAyA4. ⮭

- Benirene Tang, “Bridge over Troubled Water Cantonese,” YouTube, April 24, 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vfZAhF1vUb4. ⮭

- A similar trajectory—namely, to defy the saber-rattling “battle of narratives” by focusing on the challenges, vicissitudes and moments of enchantment in daily life as faced by ordinary people in present Hong Kong—is pursued in the anthology of short stories titled Quanri Gongying (All-day breakfast). See Grace Mak et al., Quanri Gongying (全日供應) (All-day breakfast) (Hong Kong and Taipei: Wenhua gongfang/clickpress, 2017). ⮭

- Rachel Carson, Silent Spring (Boston and Cambridge, MA: Houghton Mifflin Riverside Press, 1962). ⮭

- Chu, Found in Transition, 1. ⮭

- Chu, 181. ⮭

- Stefani Kuo, “2047, #speechtohongkong,” YouTube, accessed June 15, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-ycvzUIZHjQ. ⮭

- Yang Yeung, “Samson Young: ‘Songs for Disaster Relief,’ ” International Association of Art Critics Hong Kong, August 21, 2017, http://www.aicahk.org/eng/reviews.asp?id=667&pg=1. ⮭

- Henry A. Giroux, “When Hope Is Subversive,” Tikkun 19, no. 6. (2004): 39. ⮭

- Kennan Ferguson, “Silence: A Politics,” Contemporary Political Theory 2, no. 1 (March 1, 2003): 49–65. ⮭

- Yee, “Contemplating Land.” ⮭

- Howard Chiang and Larissa Heinrich, eds., Queer Sinophone Cultures (London: Routledge, 2014). ⮭

Author Biography

Andrea Riemenschnitter is Chair Professor of Modern Chinese Language and Literature at the University of Zurich and holds a PhD from Göttingen University and MA from Bonn University. Her current research is focused on aesthetic, cultural, and literary negotiations of Sinophone modernities with a special focus on issues related to environmental humanities. Recent publications include Anthropocene Matters: Envisioning Sustainability in the Sinosphere (special issue of ICCC May 2018); Hong Kong Connections Across the Sinosphere (special issue of Interventions, vol. 20, no. 8, 2018); Entangled Landscapes: Early Modern China and Europe (co-edited with Zhuang Yue, 2017), and Karneval der Götter: Mythologie, Moderne und Nation in Chinas 20. Jahrhundert [Carnival of the Gods: Mythology, Modernity and the Nation in China’s Twentieth Century] (2011). She is the organizer of the UZH Open Online Course Asian Environmental Humanities: Landscapes in Transition (Coursera, May 2018). Dr. Riemenschnitter has been invited as visiting research fellow to Heidelberg, Freiburg, Vienna, Singapore, Beijing, and Berkeley, and she was a visiting professor at Fudan University, Shanghai, and Beijing Normal University. Lingnan University Hong Kong has recognized her as an honorary fellow.