Introduction

Policy practice, advocacy action, and voicing social work perspectives in various political arenas are critically important roles in the social work profession. Likewise, teaching the practice of advocacy action in pursuit of social justice to emerging social workers is an obligation of social work educators supported by the National Association of Social Workers (NASW) Code of Ethics (2017) in the United States. The current authors posit that social work students often find engaging in actual macro-level social justice advocacy practice beyond the classroom environment to be a daunting and intimidating experience, particularly when interacting with law makers at the regional, state, or federal levels. The goal of this descriptive case study is to describe how a student peer mentoring program was implemented across five annual state-level legislative advocacy events, before and during the global pandemic, within a social work educational program at a regional university in the United States. The authors further propose that the assistance of peer mentors in developing and promoting legislative advocacy skills among social policy students can be a powerful tool for preparing future social workers at both undergraduate and graduate levels for macro policy practice.

Policy Practice in Social Work Education

Historically, Moore and Johnson (2002) highlight the indispensable importance of incorporating policy practice and political advocacy into social work educational content. More recently, Nowakowski and Kumar (2021) proclaim policy practice as fundamental to the education of students including, “rigorous, comprehensive and experiential training in legislative advocacy” (p. 1). As a foundational aspect of curriculum within social work educational programs, there exists an obligation to increase political interactions between students and policy makers. To build student confidence, Nowakowski and Kumar (2021) advocate that educators provide students with opportunities to learn and practice newly acquired skills. The current study authors contend that peer mentoring in social policy practice may help further demystify the legislative process for social work students.

Within social policy courses at this regional comprehensive university, students are reminded that social work is a policy-based profession advocating social justice for vulnerable, marginalized, and underserved populations. Moreover, students receive information on central concerns to the profession about political influences, policy impacts on social issues, and contemporary problems impacting human rights and issues of social justice. Social policy courses also address policy practice roles such as planners, administrators, policy analysts, and program evaluators, as well as ways to improve human services delivery systems through the application of problem-solving, critical thinking, and advocacy action (Poppel & Leighninger, 2019). One overarching goal of this legislative learning project is that students discern social work as a political profession.

High-Impact Practice (HIP)

The study authors propose that HIP experiences can be enhanced by peer mentoring, particularly in challenging novel situations, such as legislative encounters represented in this article. Modern-day high-impact experiential learning projects are largely influenced by Bloom’s (1956) taxonomy of learning wherein six processes are utilized as new knowledge is attained. Roughly translated, Bloom’s six processes include: acquisition, interpretation, utilization, distinguishing component parts, integrating meaning into a whole, and critically evaluating outcomes. Subsequently, Kuh (2008) asserted that HIPs are highly effective methods in promoting student learning within higher education as they require sustained exertion of effort over time, collaborative engagements with others, and experiencing diverse viewpoints in the learning journey. Furthermore, Kuh (2005) upholds that well-orchestrated HIPs become transformative student learning experiences by broadening their view of the world and expanding their knowledge about personal qualities in relation to others. Kuh (2008) further advocates HIPs as avenues to provide students with real-world opportunities for applying newly acquired knowledge to improve learning outcomes and promote academic success. Finally, Kuh (2008) also describes various types of high-impact learning practices including, but not limited to, common intellectual practices, collaborative assignments and projects, capstone projects or courses, global/diversity learning, e-portfolios, writing-intensive courses, learning communities/internships, and service/community-based learning. Among these various HIP types, the following three were particularly applicable in this policy case study: common intellectual student learning practices, collaborative student projects, and macro-level service learning through advocacy by design.

The strengths and benefits of HIP learning experiences are numerous (Ash & Clayton, 2004; Bringle & Clayton, 2012; Kolb, 1984; Kolb & Kolb, 2005; Kuh, 2005, 2008) and one of the greatest may be that students remember these experiences long after completing their graduation and often convey these experiences as both profound and transformative, sometimes even as the single most meaningful and memorable learning achievement from their college career. Conversely, orchestrating macro-level HIPs has challenges for faculty as well. One primary charge for HIP faculty is keeping students engaged throughout the effortful learning process. This requires contagious faculty excitement for the HIP project with frequent student interactions and continual feedback to keep them engaged, motivated, and fully participating from initiation of the HIP learning experience through the critical reflection stage after project completion.

Peer Mentoring

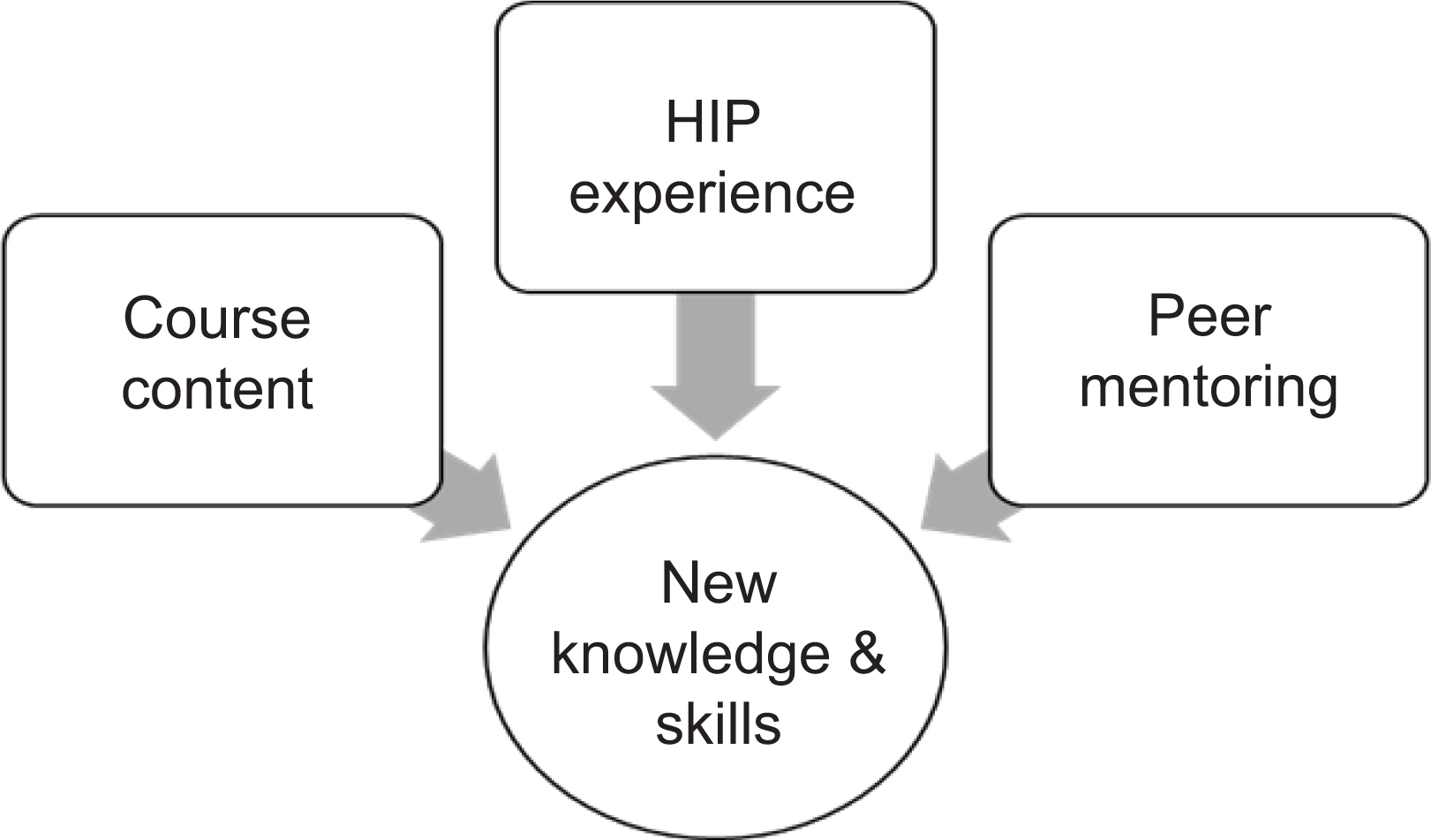

According to Walsh and Kinney’s (2018) poster, peer mentoring among students is defined as, “a supportive one-to-one relationship with persons closely approximating one another’s experiences (e.g., educational, professional, and vocational) with the goal of academic and social integration” (unpublished). Although utilized among many professions, particularly within the healthcare arena, Walsh and Kinney (2018) note that student peer mentoring is largely nonexistent within social work educational programs in the United States. This absence may not, however, be a global phenomenon; Simpson et al. (2022) note that, “internationally, higher education providers have embraced peer mentoring” (p. 3). Peer mentoring in higher education often involves upper-level students sharing their knowledge and experiences with under-classmates as they model appropriate behaviors and lead discussions with peers to enhance learning. The benefits of peer mentoring in higher education may surpass actual learning for both mentors and mentees in the transfer of knowledge (Seery et al., 2022). Benefits for peer mentors may include improving leadership and valuable interactional skills, which can become resume builders moving forward, whereas mentees build confidence in novel areas of learning. In this context, expanding course content through the HIP experience, combined with peer mentoring interchanges, may promote new knowledge and skills for peer mentors and mentees alike (Figure 1).

Integration of course content, HIP experience and peer mentoring in the acquisition of new social work knowledge and skills. Adapted from Lewis, M. L., Rappe, P. T. and King, D. M. (2018).

The overall practice of mentoring has many forms and uses. Simpson et al. (2022) describe types of mentoring,

such as classic (one-to-one) mentoring, friend to friend, group mentoring, mentoring across different agencies and professional disciplines, multiple mentors, distant mentoring, peer mentoring, and reciprocal mentoring”

(p. 1).

This case study incorporates the strategic use of three types within the added context of peer mentoring: (1) individual peer mentors assigned to a small face-to-face student learner group, (2) multiple peer mentors interacting together face-to-face with small student learner groups, and (3) several distant/remote peer mentors assigned to two or three groups of remote online learners.

The foundation and rationale for integrating peer support and mentorship guidance into this state-level legislative advocacy action project is underpinned by the professional obligation to adequately prepare emerging social workers as required within the ethical code for the profession. The NASW Code of Ethics (2017), Standard 6 declares social workers’ ethical obligations to society. Specifically, Standard 6.04 entitled, “Social and Political Action” states the role of social workers in the political arena:

(a) Social workers should engage in social and political action that seeks to ensure that all people have equal access to the resources, employment, services, and opportunities they require to meet their basic human needs and to develop fully. Social workers should be aware of the impact of the political arena on practice and should advocate for changes in policy and legislation to improve social conditions in order to meet basic human needs and promote social justice.

Furthermore, the Council on Social Work Education, Educational Policy and Accreditation Standards (CSWE-EPAS, 2022) mandate policy practice as an integral part of macro-level student social work education. This descriptive case study provides an overview and possible roadmap of how a legislative advocacy student peer mentoring program can be implemented.

Methodology

This is a descriptive case study on how a student peer mentoring program was implemented within a macro-level HIP legislative learning event. Social work students from this regional comprehensive university participate in an annual 2-day event wherein students who previously attended qualify to serve as peer mentors to new learners at the undergraduate and graduate levels. The process of event planning, peer mentor recruitment and training, student classroom preparation, capitol communications for all participants, and reflection activities are described. In addition, this case study includes the pandemic years requiring an online pivot for faculty, students, and peer mentors alike.

Legislative Advocacy Event

This state-wide, 2-day annual advocacy event has a long and rich history dating back approximately 30 years and includes students, educators, and professionals from across the state lobbying for or against current legislative bills of concern. Furthermore, this HIP event provides social work students with opportunities to observe the legislative process in real time and to professionally interact with lawmakers as advocates on issues of importance to the social work profession and vulnerable populations across the state. Over time, this annual event has evolved into a meaningful state-level voice for the social work profession. Moreover, within the last decade, the number of participants has increased with several pre-pandemic years approximating 1,000 or more participants representing 10–11 CSWE accredited programs around the state. Strategies implemented during the pandemic pivot are detailed in a later section.

One important goal for this HIP peer mentor project is bringing together current and prior policy students from diverse backgrounds as they collectively and collaboratively share in social welfare policy experiential learning activities. These peer mentors support immersive learning activities as current policy students undertake novel legislative engagement opportunities to inform and educate lawmakers on matters of social welfare concern. In so doing, peer mentors benefit by practicing leadership skills as they assist social work faculty in guiding and supporting mentees through the learning process. HIP policy project activities are specifically designed to inspire curiosity and inquisitiveness about the legislative process among new social welfare policy students, as well as to promote student and peer mentor interactions with one another and with state lawmakers as all student participants test their newly acquired skills at various levels. Finally, these immersive learning activities may positively impact student learning outcomes (SLOs) for current policy students and create aspirations for service to others and lifelong learning among both mentees and their peer mentors.

Event Planning Activities

This annual 2-day legislative advocacy event occurs in one of the larger U.S. states containing a strong NASW presence and is held in conjunction with the state legislative session each spring. The actual event activities begin with student orientation and training activities on day one followed by engagement in the legislative process at the state capitol on day two. In preparation, NASW leadership and faculty collaborations begin in early fall. Planning activities include both event logistics and selection of legislative bills. Event planners volunteer to serve on one of two committees focusing on either logistics or bills selection.

NASW state-level legislative priorities and concerns are identified by looking both backward and forward. Any issues of concern carried over from the prior legislative session are identified and then current legislative proposals are reviewed for new social issues of concern. As these are updated, new bills are identified, discussed, narrowed down, and selected by the Bills Selection Committee as the legislative session approaches. Some typical social work legislative target priorities include child welfare, criminal justice reform, education, veterans and military families, mental and behavioral health, immigration justice, and disability rights. Although numerous bills may be identified and followed by the NASW state chapter, the number of bills for student educational purposes is typically narrowed to less than 10 from the legislative target priorities each spring. University faculty may then select individual bills on which students are to focus their attention in preparation for the advocacy event.

The Logistics Planning Committee duties begin with proposed event dates coordinated around legislative session schedules and university holidays and breaks. Logistics also involves arranging adequate conference facilities to host a large number of participants for orientation, training, keynote speakers, and university roll call on day one. In addition, coordinating an early morning day-two breakfast rally on the capitol steps is a key component as participants prepare to enter the capitol complex en masse as legislative interactive activities begin. Finally, logistics coordinators arrange a designated area within the capitol complex for social work networking activities among participating universities on day two.

In addition to state-level collaborative efforts, policy professors at this regional university partner with campus librarians to ensure that library guides contain information and resources specific to the social work profession. These professors routinely collaborate with the designated social work librarian each fall to design student trainings on researching bills and gathering policy-related information using credible sources. This partnership is essential to the success of this HIP project as librarians often host student workshops and online trainings on navigating legislative websites and methods of tracking bills.

Peer Mentor Recruitment and Training

An essential aspect of preparation for the legislative advocacy event is the recruitment, training, and preparation of student peer mentors. In order to qualify for service as a peer mentor, students must have previously participated in this legislative event. Recruitment activities include calls for potential student peer mentors announced in classes and in student organization meetings early in the academic year. Other possible candidates may be found each fall among graduate assistants (GAs). The goal is to have multiple peer mentors to support all sections of social welfare policy students at both undergraduate and graduate levels.

Once selected, peer mentors are invited to participate in state-level preparation activities along with faculty members and NASW Chapter leadership. Peer mentors spend time learning which bills from the previous session had successful outcomes based on NASW Chapter’s prior legislative priorities. In addition, they explore current social welfare issues around the state and research new bills of concern as the legislative session gets underway. In researching new bills, student peer mentors utilize faculty developed instruments designed to capture key components contained within each bill. These same instruments are later utilized by students; thus, peer mentors are prepared to assist mentees in addressing inquiries as student advocacy training ensues.

In early spring each year, peer mentors are assigned student groups across policy course sections to assist and support throughout this high-impact learning project. One key feature of this HIP project is that student groups are purposefully intermingled across undergraduate and graduate course sections so as to create a bonded student group at the actual event. Although each year is unique in the composition of student peer mentors, ideal partnerships using undergraduate and graduate peer mentors is often perceived more favorably by student mentees across program levels.

Student Classroom Preparation

Faculty-led student preparation for this annual event begins in the classroom each spring. Student training first addresses how bills become law at both federal and state levels, followed by an orientation to the state legislative process, learning how to find state legislators, as well as legislator committee assignments and their voting histories. Peer mentors are kept abreast of student learning along the way as the event approaches and are invited to participate in all student training and reflection activities before and after the event. Policy students are educated on parliamentary procedures, matters of professional decorum, expectations of capitol visitors, and lobbying strategies. To further reinforce student learning on advocacy strategies, students and peer mentors participate in role-plays and rehearsals simulating interactions with lawmakers using best-case/worst-case scenarios while practicing legislative etiquette and communication skills.

Students are assigned to groups with designated bills to research, analyze, and present to class peers. Peer mentors follow this progression in student training as they are matched with student groups and bills as well. The framework for bill assignments requires that students utilize specific social work policy library resource guides within the university system to ascertain information on policy summaries of the social issue addressed in each assigned bill, history and bill development, implementation plan, program evaluation plan, analysis of cost effectiveness, and current recommendations. The purpose of this assignment is to teach students to locate credible research related to a social issue, policy, or program. In so doing, students initiate the process of analyzing social policy and thereby develop necessary critical thinking skills toward future solutions.

Classroom preparation includes observing any updated NASW Chapter materials, virtual committee meetings and utilizing capitol archival materials. Students also observe a virtual orientation to the large state capitol complex, the Senate and House of Representative Chambers, and archived videos from previous voting sessions on the Senate and House floors. When class schedules permit, multiple social policy course sections across undergraduate and graduate programs meet together in order to interact with peer mentors and reinforce support and networking opportunities. Logistically, having in-person social policy class meetings offered on the same weekday further facilitates networking opportunities and helps ensure legislative advocacy success across undergraduate and graduate levels. Likewise, bringing online course sections together in virtual student preparation sessions helps to create online student communities. Final preparation activities include student consent forms for social media, use of student photographs, and arranging messaging among all participants so as to maintain continuity once at the capitol complex.

Capitol Communication

Once at the capitol, students demonstrate professionalism in their interactions with peers and lawmakers alike. Peer mentors serve as role models for professional communication and as group leaders assisting students in navigating the capitol according to faculty-directed itineraries. Internal communications and timely messages among professors, peer mentors, and students are key to keeping everyone on schedule during this busy and rapidly evolving state-wide event. Announcements and updates are shared using a messaging application on mobile devices with peer mentors monitoring this fluid process so as to support student learning throughout the event. Students and peer mentors often rehearse bill presentations while awaiting scheduled appointments with law makers. Verbal communications between student groups and lawmakers during these appointments are further supported using NASW Chapter developed fact sheets highlighting key features and social implications of specific bills. These are provided to law makers by student groups during scheduled appointments arranged by university faculty. Prior training is reinforced as students are encouraged that it is okay to state, “I don’t know” in response to specific inquiries from legislators as opposed to generating erroneous information, although follow-through on returning accurate information to the legislator within a specified time frame is vital in exhibiting professional courtesy. Finally, peer mentors are helpful in debriefing student groups after scheduled legislator appointments.

Pandemic Pivot

The global pandemic necessitated a pivot from fully in-person immersive student experiences to fully online virtual high-impact student learning. To preserve the consistency of this long tradition of state-wide social work advocacy, NASW state-level leadership and policy faculty from around the state collaborated to bring this interactive event to students during the pandemic years as a fully online virtual high-impact student learning experience. The use of virtual or distant peer mentors was vital during this unprecedented pivot to reduce student anxiety during virtual preparation activities, as well as assisting student participants in navigating each 2-day legislative event. This successful state-wide collaboration hosted hundreds of policy students during those years with virtual real-time student orientation on day one and coordinated video conferencing appointments with law-makers on day two. Students were provided with links to House and Senate committee meetings, as well as NASW Chapter chat rooms frequented by peer mentors for support throughout the 2-day virtual event. Faculty and NASW Chapter leaders served as online moderators, team leaders, trainers, and appointment coordinators in order to provide a comprehensive student learning experience approximating the in-person events of prior years with student mentors providing support to students from this regional university where ever possible. As in pre-pandemic years, student groups from this university were purposefully intermingled across undergraduate and graduate course sections via faculty-led online video conference sessions to create a bonded student group for each virtual annual event during pandemic pivot years.

Reflection, Evaluation, and Conclusion

After the HIP legislative event, students and peer mentors participate in facilitated discussions, either face-to-face or online, to share and reflect upon successes and challenges experienced during the 2-day event and to help transfer learning to real-world applications as future social workers. These facilitated discussions provide valuable interactions, which help guide student completion of written critical reflection papers. Written reflections detail perceptions of learning, personal growth, and how participating in this experience better prepares them as future social work advocates (Lewis, Rappe, Albury, & Edler, 2017). Student reflections include describing preparation activities for the event, their interactions with peer mentors, their roles at the actual event, and the impact of this student learning opportunity in terms of professional development. These important critical reflection activities bring an element of closure as students examine their pre-existing ideas to link and integrate with newly acquired knowledge (Kolb, 1984; Kolb & Kolb, 2005).

In keeping with Kuh’s (2008) notion of transformational learning, the current study authors contend that combining legislative HIPs with the strategic use of peer mentoring creates transformative student learning opportunities. Such opportunities may broaden student world views through interactions with diverse others while being supported by faculty and peer mentors. This provides students with avenues to practice real-world social work advocacy as they apply new knowledge and skills, thereby possibly improving learning outcomes and promoting academic and professional success.

This case study describes the process and utility of incorporating peer mentors into legislative learning projects for undergraduate and graduate students of social work. It is hoped that this article inspires social work faculty to promote and implement peer mentoring HIP projects within their social welfare policy courses. The sustained success of any HIP project is largely determined by contagious faculty enthusiasm coupled with programmatic support of HIP initiatives that make a meaningful student impact across time. Fostering peer mentoring opportunities as central features within legislative advocacy action projects creates possibilities for students to share supportive group relationships with one another along their developmental learning journey.

References

Ash S. L., & Clayton P. L. (2004). The articulated learning: An approach to guided reflection and assessment. Innovative Higher Education, 29(2), 137–154. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:IHIE.0000048795.84634.4ahttps://doi.org/10.1023/B:IHIE.0000048795.84634.4a

Bloom B. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook 1: Cognitive Domain. New York: McKay Publishing.

Bringle R. G., & Clayton P. H. (2012) Civic education through service-learning: What, how, and why? In McIlraith L. L., Lyons A. A., & Munck R. R., (Eds.), Higher education and civic engagement: Comparative perspectives (pp. 101–124). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Council on Social Work Education – Educational Policy and Accreditation Standards (CSWE-EPAS). (2022). Alexandria, VA: Council on Social Work Education.

Kuh G. D. (2005). Student success in college. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Kuh G. D. (2008). High-impact educational practices: What they are, who has access to them, and why they matter. San Francisco: Association of American Colleges and Universities.

Kolb A. Y., & Kolb D. A. (2005). Learning styles and learning spaces: Enhancing experiential learning in higher education. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 4(2), 193–212. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2005.17268566https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2005.17268566

Kolb D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Hoboken, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Lewis M. L., Rappe P. T., Albury J. D., & Edler L. D. (2017). Creative teaching and reflection in nontraditional settings: Regional, national and international experiences. International Journal of Social Development Issues, 39(1), 29–40.

Lewis M. L., Rappe P. T. & King D. M. (2018). Development and Promotion of Student Advocacy Skills within a Human Trafficking Course. International Journal of Social Development Issues, 40(2), 24–35.

Moore L. S., & Johnston L. B. (2002). Involving students in political advocacy and social change. Journal of Community Practice, 10(2), 89–101. doi:10.1300/J125v10n02_0610.1300/J125v10n02_06

National Association of Social Workers. (2017). NASW code of ethics. Retrieved from https://www.socialworkers.org/About/Ethics/Code-of-Ethics/Code-of-Ethics-English.https://www.socialworkers.org/About/Ethics/Code-of-Ethics/Code-of-Ethics-English

Nowakowski-Sims E., & Kumar J. (2021). Increasing self-efficacy with legislative advocacy among social work students. Journal of Social Work Education, 57(3), 445–454. https://doi.org/ezproxy.lib.uwf.edu/10.1080/10437797.2020.1713942https://doi.org/ezproxy.lib.uwf.edu/10.1080/10437797.2020.1713942

Seery C., Andres A., Moore-Cherry N., & O’Sullivan S. (2021). Students as Partners in Peer Mentoring: Expectations, Experiences and Emotions. Innovative Higher Education, 46(6), 663–681. https://doi.org/ezproxy.lib.uwf.edu/10.1007/s10755-021-09556-8https://doi.org/ezproxy.lib.uwf.edu/10.1007/s10755-021-09556-8

Simpson D., Pearson B., Kelly M., Mendum I., Lockwood A., & Fletcher S. (2022). Buddy up! Student mentoring in a social work undergraduate programme. Social Work Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2022.2057465https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2022.2057465

Poppel P., & Leighninger L. (2019). The policy-based profession: An introduction to social welfare policy analysis for social workers, (7th ed.). New York: Pearson.

Walsh J. S., & Kinney M. K. (2018, January 10–14). Peer mentoring in social work education: Strengths & challenges [Poster Session]. In SSWR 2018 Conference of the Society for Social Work and Research, Washington, D. C., United States. Retrieved from https://sswr.confex.com/sswr/2018/webprogram/Session9330.htmlhttps://sswr.confex.com/sswr/2018/webprogram/Session9330.html

Melinda L. Lewis, PhD, LICSW, PIP, Janet D. Albury, MSW, and Miu Ha Kwong, PhD, LCSW are Professors, Department of Social Work, University of West Florida, Pensacola, FL, USA. They can be contacted at mlewis1@uwf.edu; jalbury@uwf.edu; mkwong@uwf.edu.