Introduction

Health facilities in low- and middle-income countries face a severe shortage of infrastructure, equipment, and drugs, which negatively impact families with low income. Several studies have emphasized the lack of resources and adequate infrastructure in hospitals (Joshi et al., 2014; Mabuchi, Sesan, & Bennett, 2018; Rao, Rao, Kumar, Chatterjee, & Sundararaman, 2011). The procurement policy of drugs plays a crucial role in service delivery and ensuring people have access to health care at an affordable price. The unavailability of drugs, interrupted supplies, and lack of consumables pose significant barriers to the provision of health services (Watt et al., 2017). This, in turn, hampers access to essential medicines and disproportionately affects low-income populations, both due to the lack of drugs in public health facilities and the out-of-pocket expenses required to obtain them (Bigdeli, Laing, Tomson, & Babar, 2015; Magadzire, Marchal, & Ward, 2015; Wirtz et al., 2017). Scholars have stressed the importance of strengthening local drug procurement (Prinja, Bahuguna, Tripathy, & Kumar, 2015; Tatambhotla, Chokshi, Singh, & Kalvakuntla, 2015; Waako et al., 2009), but it remains a challenging area.

Local-level drug procurement depends on various factors. In a study on drug procurement in East Africa (Kenya and Tanzania), Mackintosh et al. (2018) found that frontline health staff manage procurement at the local level. However, concerns arise regarding the quality of supplies from public wholesale providers, as specific drugs may not be available for over 6 months. Typically, health facility staff procure drugs from local shops and wholesalers (Mackintosh et al., 2018). In another study conducted in Tanzania, Plotkin et al. (2014) evaluated the integration of HIV screening into government health facilities that provided cervical cancer services. The study revealed that while there was adequate uptake of cervical cancer screening, approximately 71% of women did not receive HIV screening due to the unavailability of HIV kits at the health facility (Plotkin et al., 2014). Logistic barriers, limited access to essential supplies and equipment, and the lack of integration may hinder the delivery of comprehensive health services.

The shortage of equipment and drugs impairs the ability of health workers to provide effective care (Manongi, Marchant, & Bygbjerg, 2006). Diagnostic and screening tools, as well as necessary consumables for health and safety, are often lacking, which directly impacts service delivery and quality of care. In addition, hospital infrastructure and resource availability are critical factors in delivering integrated care to patients. However, these aspects depend on external factors beyond the control of health workers, such as organizational policies, procedures, rules, and financial resources. This paper aims to examine the institutional process of drugs procurement in the National Program for Prevention and Control of Diabetes, Cardiovascular Disease, and Stroke (NPCDCS). It seeks to illustrate how various guidelines, policy texts, and local practices are interconnected and affect the availability of drugs within the program at district hospital.

Background

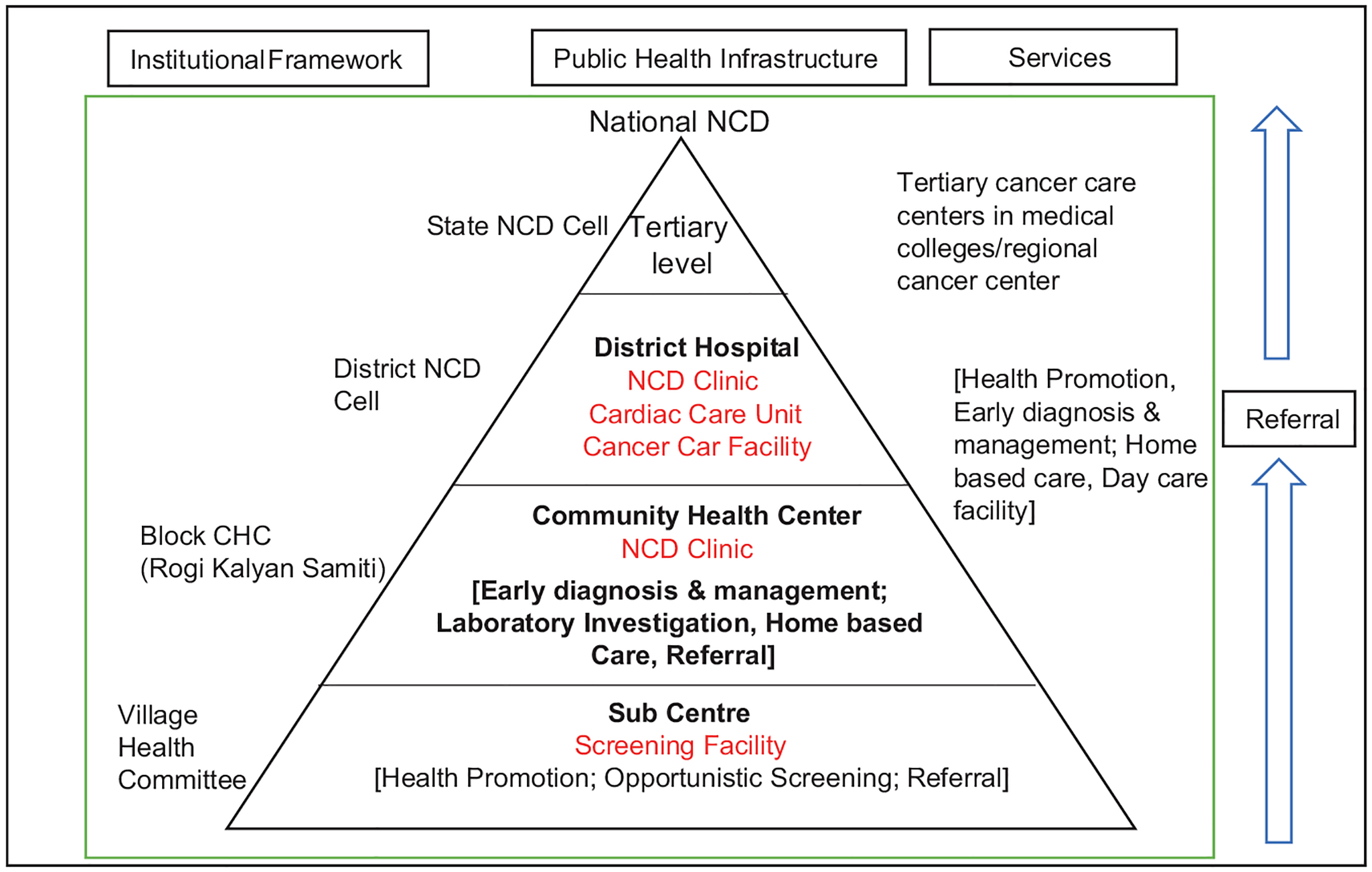

In 2008, the Government of India launched the NPCDCS as a pilot project in 10 states: Punjab, Rajasthan, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Assam, Madhya Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Sikkim, and Gujarat (Government of India, 2011). The NPCDCS has been implemented at various levels of care, including primary, secondary, and tertiary. The program was expanded to 100 districts by merging the National Cancer Control Program into the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) structure. Within this program, primary care is responsible for creating awareness, facilitating early detection, and making appropriate referrals, while secondary and tertiary care levels provide prevention, early detection, management, referral, training, and surveillance services. The integration of the NPCDCS program into the general health system aims to optimize resource utilization, ensure uninterrupted care for patients, and achieve maximum efficiency.

The NPCDCS was integrated into the NRHM at both the state and district levels, leading to the establishment of district noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) cells in each district. Figure 1 provides an overview of the institutional structure for service provision, and Table 1 outlines the services available at different levels of care within the NPCDCS program. The primary role of the district NCD cell was to plan, implement, monitor, and evaluate program activities, while also being held accountable for achieving the physical and financial targets set by the state program. They were responsible for ensuring that these targets were met in a timely and efficient manner. However, due to a shortage of personnel within the NPCDCS program, the management and implementation of the program have been delegated to the district health society (DHS).

Source: Government of India (2011).

NPCDCS: National Program for Prevention and Control of Diabetes, Cardiovascular Disease, and Stroke; NCD: noncommunicable diseases.

Packages of services at the different levels of care under the NPCDCS program

| Health subcenter |

|

| CHC |

|

| District Hospital |

|

| Tertiary Cancer Centre |

|

Source: Government of India (2011).

CHC: Community Health Center; CVD: Cardiovascular disease; ECG: Electrocardiography; BP: Blood pressure

NPCDCS: National Program for Prevention and Control of Diabetes, Cardiovascular Disease, and Stroke.

The NPCDCS program employs various integration strategies aimed at enhancing patient outcomes through improved coordination of services. These strategies include case management, co-location of services and information, implementation of healthcare teams, and adopting a population health approach to facilitate health system integration.

Methodology

Methods

Using institutional ethnography, this study explored how drugs are procured in the NPCDCS program in Bihar. This method of inquiry, developed by Canadian sociologist Smith, examines everyday work from the standpoint of people and how they acquire knowledge (Smith, 1987, 1999, 2005, 2006). Institutional ethnography rejects theory and objective accounts and embraces a reflexive way of knowing the world based on our own experiences (Smith, 1990, 2006). It offers an insider perspective that does not be subject to absolute truth, objectivity, or ideology (Kearney, Corman, Hart, Johnston, & Gormley, 2019). Institutional ethnography allows researchers to examine the multifaceted social relations that organize everyday experiences (Campbell & Gregor, 2004; Smith, 2005). Smith (2006) argues that texts shape the social order by conveying the interests of actors, located outside the local environment, and regulating people’s everyday actions. Smith defines texts as “specific forms of work, numbers, or images that can be materially reproduced” (Smith, 2001, p. 164).

In Smith’s perspective (2001, p. 174), the act of reading texts mirrors the standardization of work and activities across different time periods and locations. According to Smith (2001, p. 175), texts serve as the “fundamental medium for coordinating people’s work activities.” Building upon this concept of textual practice proposed by Smith, this study aims to analyze the drug procurement and availability in the NPCDCS program in district hospitals in Bihar. The study received ethical approval from the Institute for Global Health and Development at Queen Margaret University, with reference number REP0280. Prior to their participation in the study, all research participants provided written and verbal informed consent.

Data Collection and Data Analysis

The fieldwork and data collection for this study were carried out in three phases over a 10-month period, from November 2015 to August 2016, in three districts of Bihar: West Champaran, East Champaran, and Vaishali. In 2010–11, the NPCDCS program was introduced in Vaishali and Rohtas districts in Bihar and subsequently expanded to four additional districts: Muzaffarpur, East Champaran, West Champaran, and Kaimur, in 2011–12. The data were collected using participant observation, interviews, and reviews of official documents and program guidelines. Observations took place at various locations, such as hospitals, NCD clinics, mental health clinics, and administrative offices, to gain insights into the service provision process and the activities of health personnel in integrated health programs and service delivery.

A total of 27 people who work in different roles related to the NPCDCS program were interested including health workers, program managers, hospital managers, administrators, medical doctors, etc. The selection of participants was based on their ability to provide relevant information and gain knowledge about their work in the NPCDCS program. A total of 48 official textual documents were analyzed to understand how institutional processes are coordinated at different levels. Social mapping, analytical writing, and textual analysis were used to analyze the data and examine how institutional processes affect the procurement of drugs and delivery of NPCDCS programs at the district hospitals.

Findings

Centralization and the Power of the State Government over Drug Procurement

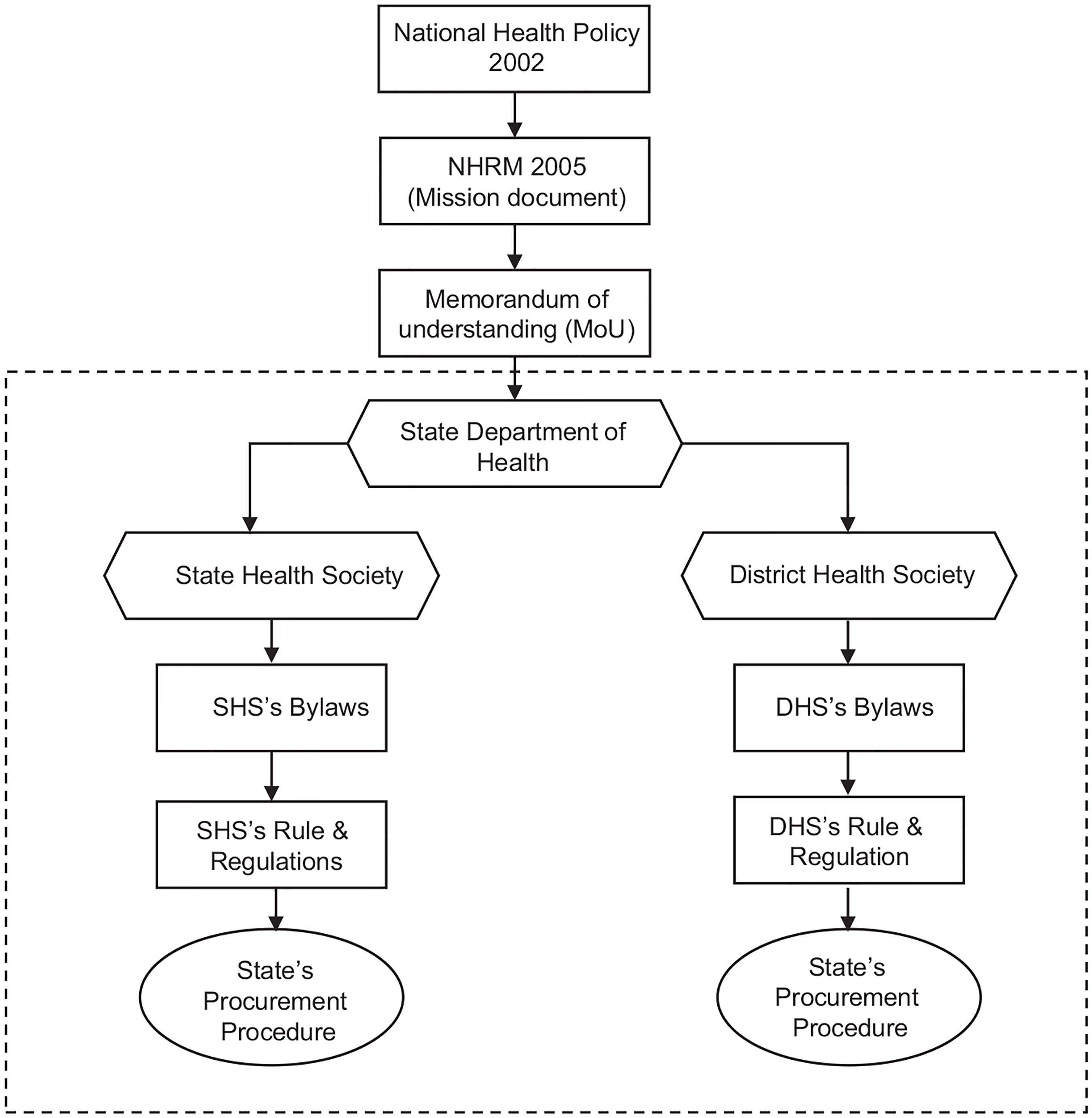

National health programs are delivered under the NRHM framework, which later included urban component and became the national health mission (NHM) in India. Under this NHM framework, memorandum of understanding (MoU) outlines the role and responsibility of center and state government in delivering health services across the country. These policy and program guidelines, along with various documents, such as rules, regulations, and laws, provide direction to state officials regarding the procurement of goods and services at the state and district levels. However, there is a contradiction between the memorandum of association (MoA) of the State Health Society Bihar (SHSB) and the model generic bylaws of the state health society, which were provided by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) at the time of signing the agreement. The Department of Health is obligated to adhere to the bylaws as part of the MoU signed between the department and the MoHFW.

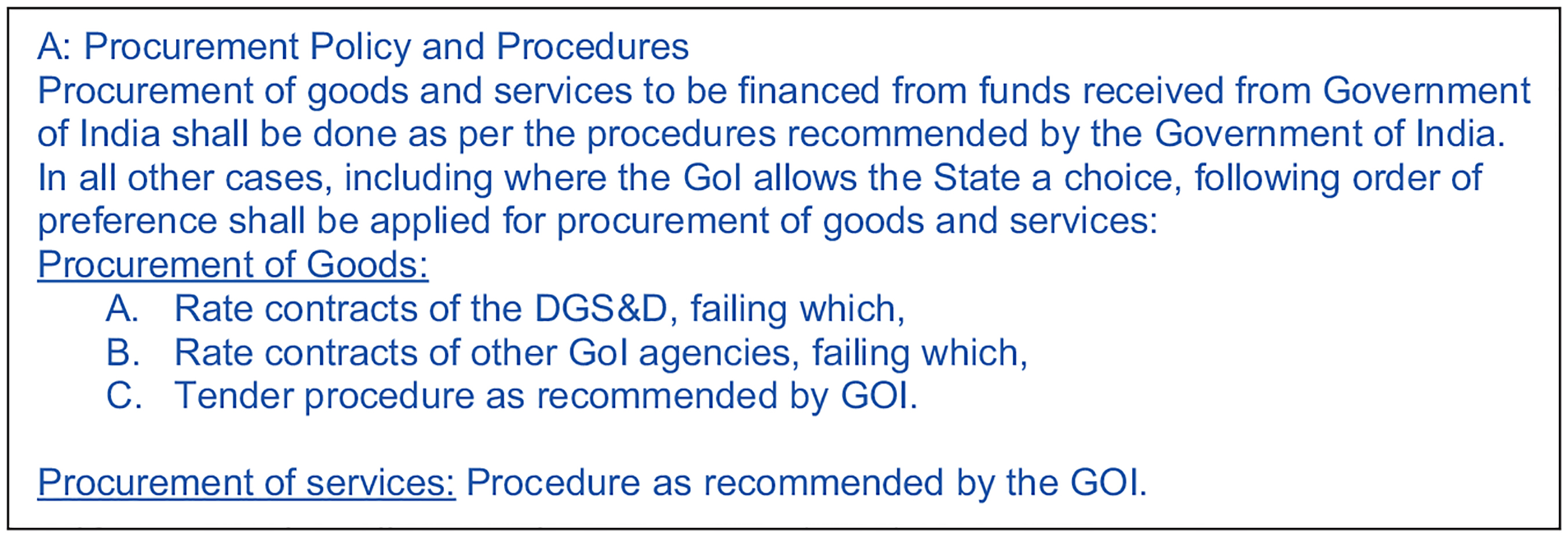

On the other hand, the SHSB is an autonomous organization with the authority to establish its own procurement procedures and policies as outlined in its bylaws. While the state has the power to develop its own policies related to health care service delivery, an analysis of textual documents reveals that the procurement of goods and services by the state health society is indirectly coordinated and governed by the MoHFW. According to the SHSB’s MoA, the society has the freedom to “establish its own procurement procedures and use the same for the procurement of goods and services” (Government of India, 2005). This highlights the autonomous nature of the SHSB, allowing it to determine its own organizational rules, regulations, and policies. However, the generic bylaws of the state health society, which are part of the MoU between the Department of Health and the MoHFW, state that “the procurement of goods and services to be financed from funds received from the Government of India [central government] shall be carried out according to the procedure recommended by the Government of India” (Government of India, 2005). This implies that the state government and its agencies have limited authority over drug procurement processes if they are funded by the central government. Figure 2 illustrates the conditions related to the procurement of goods and services under the NRHM as outlined in the MoU.

By signing the MoU, the state government agreed to comply with all existing manuals, guidelines, instructions, and circulars related to the implementation of the NRHM, as long as they do not contradict the provisions of the MoU itself (Government of India, 2005, p.6). This MoU, being an official partnership document, imposes limitations on the authority of the SHSB and creates a dependency on the MoHFW for instructions regarding the procurement of goods and services for national health programs. As a result, it restricts the ability to innovate and address drug acquisition within the Indian states. Figure 3 provides an illustration of how the MoU indirectly coordinates and controls the procurement policy for both state and district health societies through the MoHFW’s influence.

The NPCDCS program in Bihar demonstrates the clear dependence of the SHSB on the MoHFW for instructions regarding the procurement of goods and services.

The Dependence on the Central Government for Drug Procurement Led to the Supply of Substandard Quality Drugs

Under the NPCDCS program, the government provides free drugs to patients with common NCDs, such as diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease, who receive treatment at public hospitals. To support the provision of these drugs, the government has allocated Rs. 50,000 (approximately $714) per month for drug procurement for diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and stroke in each district NCD clinic, as stated in the NPCDCS guidelines (2011). It is the responsibility of the state government to procure the necessary drugs for the NPCDCS program through the state’s procurement mechanism. Table 2 in this document presents the list of drugs for diabetes, CVD, and stroke as specified in the NPCDCS guidelines.

Indicative list of drugs for diabetes, CVD & stroke (NPCDCS guideline, 2013)

| Drugs | Drugs |

|---|---|

| Tab. Aspirin | Inj. Digoxin |

| Tab. Atenolol | Tab. Digoxin |

| Tab. Metoprolol | Tab. Verapamil (Isoptin) |

| Tab. Amlodipine 10 mg | Inj. Mephentine |

| Tab. Hydrochlorothiazide 12.5, 25 mg | Tab. Potassium IP (Penicillin V) |

| Tab. Enalapril 2.5/5 mg | Inj. Normal saline (Sod chloride) 500 mL |

| Tab. Captopril | Inj. Ringer lactate 500 mL |

| Tab. Methyldopa | Inj. Mannitol 20% 300 mL |

| Tab. Atorvastatin 10 mg | Inj. Insulin Regular |

| Tab. Clopidogrel | Insulin Intermediate |

| Tab. Frusemide 40 mg | Tab. Metformin |

| Inj. Streptokinase 7.5 lac vial | Inj. Aminophylline |

| Inj. Streptokinase 15 lac vial | Tab. Folic Acid |

| Inj. Heparin sod.1,000 IU | Inj. Benzathine Benzyl penicillin |

| Tab. Isosorbide Dinitrate (Sorbitrate) | Carbamazepine tabs, syrup |

| Glyceryl Trinitrate Inj., Sublingual tabs | Inj. Lignocaine hydrochloride |

| Diazepam Inj. & Tab | Inj. Dexamethasone 2 mg/mL vial |

| Inj. Adrenaline | Tab. Prednisolone |

| Inj. Atropine sulfate | Promethazine Tab, Syrup , Caps, Inj. |

Source: NPCDCS guideline (2013).

NPCDCS: National Program for Prevention and Control of Diabetes, Cardiovascular Disease, and Stroke.

Although the NPCDCS program offers free medicines, patients are often directed to purchase their medication from local private shops. During my observation, I noticed that patients were informed about the insufficient availability of medicine for diabetes and hypertension at the district hospital. Curious about this issue, I approached a health worker to inquire about the supplies of medicine and consumables at the hospital. He responded,

Do you know… in the beginning, we used to conduct diabetes screening at the NCD clinic. All the necessary supplies such as lancets, strips, and glucometers were provided by the Indian government (the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, MoHFW). However, at a later point, we received a large quantity of strips that were nearing their expiration date. During that time, the nodal officer instructed us to utilize all the strips during a medical camp. We organized these camps in various locations like the local market, bus stand, and train station. However, after that incident, we stopped receiving any drugs or consumables from the government. Currently, we have to purchase everything including strips, lancets, and diabetes drugs from the local market. (Health worker, NCD clinic)

After gathering information from the health workers regarding the consumables provided by the MoHFW, I conducted further research and examination of official documents and letters at the District State Hospital (DSH) and SHSB. These documents shed light on the procedures for the supply of consumables. The official documents reveal that the MoHFW had a significant role in supplying consumables to the state between June 2011 and September 2013, following the launch of the NPCDCS program. These consumables were received from the MoHFW and stored at state drug storage facilities located in Patna. According to the official records, the Department of Health received two batches of strips from Abbot Health Care Ltd. in January 2013. It is worth noting that these two batches of strips had only a few months remaining before expiration. Unfortunately, one batch expired in March 2013, while the second batch was due to expire in May 2013 (refer to Table 3; field notes, Patna).

Expiry dates (months/years) of supplies procured by the MoHFW

| Supply Lot No | Glucometer | Strip | Lancet | Reference (letter date/supply date) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 03/2012 | 02/2012 | 09/2015 | 30/06/2011 |

| 2 | 03/2012 | 06/2012 & 07/2012 | 09/2015 | 20/10/2011 |

| 3 | – | 03/2013 & 05/2013 | 11/2016 | 12/04/2012 |

| 4 | – | 03/2013 | 11/2016 | 05/02/2013 |

| 5 (Directly delivered to DHS) | – | 08/2013 & 09/2013 | – | – |

Source: State Health Society Bihar.

MoHFW: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; DHS: district health society.

The state drug storage officer raised concerns about the substandard quality of consumables procured by the MoHFW and communicated this issue to the Executive Director of SHSB through a letter. In response to the complaint, the SHSB wrote a letter to the MoHFW informing them about the substandard supply of consumables, specifically the expired strips, and seeking their advice on the matter. The MoHFW, in turn, sent a letter instructing the Department of Health to utilize all the supplied strips (which were close to expiry) through health camps and fairs in the district before the expiration date.

The purpose of the MoHFW’s letter was to ensure that the state made use of the supplied strips through health camps. However, the letter did not address any action taken against the supplier of the substandard consumables. The focus of the instruction was solely on the utilization of the strips through health camps. It is important to note that organizing health camps is a significant undertaking at the district level, requiring careful planning and execution across districts. However, the letter did not provide any additional information about the health camps, such as human and financial resources required. It failed to address crucial questions, such as who would organize the health camps, which staff category should be deployed, and how the NCD clinic’s screening services would be managed if staff were deployed to the health camps. These important questions remained unanswered.

This official letter initiated a “text–reader conversation” process, requiring the administrator to take action based on the instructions outlined in the letter. Following the MoHFW’s letter, the SHSB sent a letter to inform district health administrators about the utilization of the strips through organizing health camps. However, this letter also lacked information regarding the necessary resources for organizing the health camps. The district health administrator, as the reader of the letter, understood it as an administrative order that needed to be followed. In response to this administrative order, the district health administrator deployed health workers from the NCD clinic to organize health camps at various locations in the district. The purpose of these health camps was to increase awareness and provide diabetes screening services to the general public, leading to a disruption of services such as screening and counseling at the NCD clinic.

Despite the efforts of the district health administrator and health workers, the utilization of the strips was limited due to a shortage of health workers, resulting in significant wastage. This situation demonstrates how the authoritative text (i.e., the letter) from the MoHFW brought the SHSB, DHS, and health workers into a social relationship focused on accomplishing the task of utilizing the strips through health camps, without acknowledging or discussing the local capacity or available resources. It highlights how the work of health workers is interconnected with the MoHFW, shaping their everyday tasks and responsibilities.

Transferring the Responsibility of Drug Procurement to the State Was not Successful

Following the incident of substandard supplies, the MoHFW issued a letter instructing all states, specifically the Department of Health, to procure consumables and supplies for the NPCDCS program through the state’s procurement system. This instruction immediately transferred the responsibility for procurement from the MoHFW to the state government. However, the state was unprepared to assume this responsibility, leading to unexpected delays and interruptions in procurement, as stated by the program manager of SHS. The procurement process for consumables involves various unseen tasks and activities, such as creating a list of required drugs, estimating the quantity needed, obtaining administrative approval, preparing guidelines, initiating the technical bid and tendering process, evaluating bids, and finalizing the procurement, which all require a significant amount of time. The MoHFW did not provide any guidance on how the state should ensure the availability of consumables during the transition period.

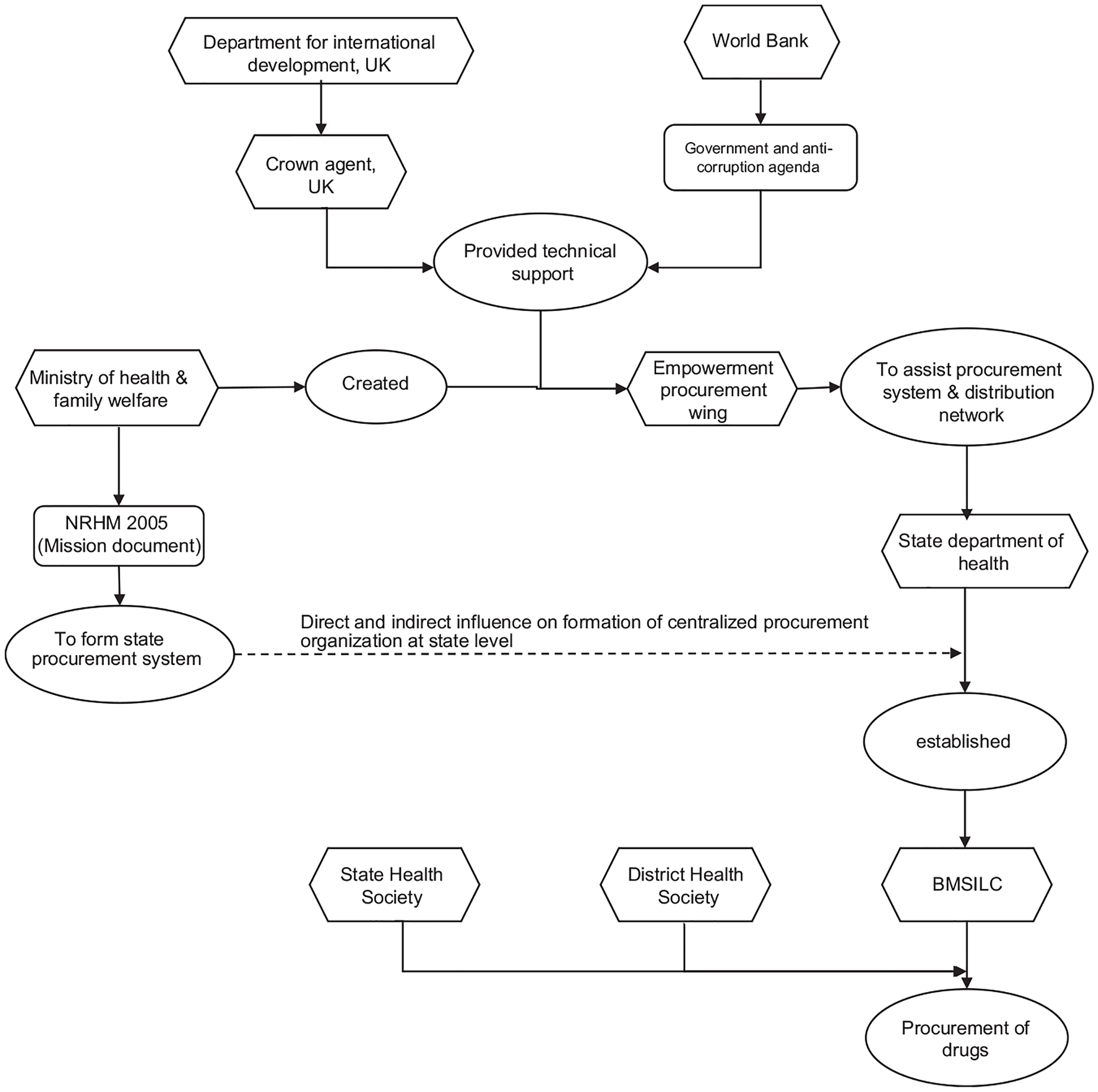

It is important to note that the state program manager responsible for implementing the NPCDCS program does not have the authority to procure drugs and consumables. After delegating the procurement responsibility to the Department of Health, the Bihar Medical Service and Infrastructure Corporation Limited (BMSICL) was assigned the task of procuring consumables for the NPCDCS program. BMSICL is designated as the State Purchase Organization (SPO) and was established in 2010 under the 1956 India Company Act. It received support from the Empowered Procurement Wing (EPW) of the MoHFW and technical assistance from the Crown Agent in the United Kingdom, funded by the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (DFID) (The Global Fund, 2008). The establishment of BMSICL aimed to expedite the development and streamlining of infrastructure and services in the Indian health sector. In 2005, the NRHM conceptualized BMSICL as a state-led procurement system and distribution network to enhance the supply and distribution of drugs and medicines. BMSICL serves as the sole procurement and distribution agency for goods and services for all establishments under the Department of Health, Government of Bihar. The involvement of the Crown Agent UK included training, needs assessment, development of procurement procedures and systems, storage management, quality assurance, and information management. The establishment of a centralized procurement agency for the state aimed to bring transparency to the procurement process. Figure 4 provides an overview of the coordinated efforts to establish a state procurement system in Bihar.

Despite the efforts to promote transparency and efficiency in the procurement of goods and services, BMSICL, in 2014, faced allegations of corruption. The Department of Health discovered that BMSICL had purchased substandard drugs and medical supplies from a blacklisted company at exorbitant prices (Bihar Purchased Drugs from Blacklisted Firms – Times of India, 2014). In response to these findings, the government took action by suspending senior health officials and initiating an inquiry into the corruption charges. The suspensions at BMSICL had a significant impact on drug procurement in Bihar.

Between April and May 2015, BMSICL issued a short-term tender for the supply of life-saving drugs. However, this tender did not attract suppliers or pharmaceutical companies to participate in the bidding process. Out of the 25 required drugs, BMSICL received only one bid for 23 drugs, which was subsequently rejected on technical grounds (Life-Saving Drugs’ Purchase Bid Fails – Times of India, 2015). According to the Bihar Financial Rule (Amended) 2005, a single bid cannot be accepted for procurement decisions (Government of Bihar, 2005). This corruption incident had a wide-reaching impact, affecting procurement for all health programs in Bihar. During a discussion with a state program manager, he expressed frustration with BMSICL for the delayed procurement of consumables for the NCDs programs,

…However, the BMSICL officers do not listen to us. Despite sending numerous letters to the Managing Director (MD) of BMSICL, we have received no response to our requests. We have been specifically requesting the rate contract so that we can inform the district health administrators (DHS) to procure goods at the rates finalized by BMSICL. (Program Manager, State Health Society, Patna)

In the interview, the health official expressed his concern about the unexpected delay caused by BMSICL. Despite his efforts to draw attention to the procurement of drugs and consumables for the NPCDCS program, BMSICL did not respond to his requests. This delay in BMSICL’s actions had a significant impact on many health programs in Bihar, as noted by the manager at SHSB. The frustration resulting from these delays was also observed during discussions with health workers at NCD clinics in the study sites. The health workers felt helpless when they were unable to provide medication to financially disadvantaged patients at the NCD clinic.

These experiences of frustration and helplessness stemmed from broader institutional inaction. Until August 2016, BMSICL had not established the procurement rates for consumables such as strips, lancets, and drugs. This further hindered program implementation and service delivery. In the absence of a response from BMSICL, the SHSB issued instructions to the DHS, urging them to procure drugs and consumables for health programs at the district level, following the Bihar Financial (Amendment) Rule 2005, until further orders were received from the SHSB.

Drug Procurement at the District Level

The district hospitals responsible for implementing the NCDs program faced a shortage of essential drugs for patients with common NCDs. As a result, patients were required to purchase drugs and medicines from private shops, leading to increased out-of-pocket expenses. Although drugs were purchased in smaller quantities to address immediate patient needs, it proved insufficient. A health worker mentioned a “local purchase system” that enables district administrators to procure drugs without being burdened by administrative and bureaucratic processes. During an interview, a health worker expressed:

Since the government, specifically the MoHFW, has ceased providing us with medicine, we resort to procuring it through a “local purchase” system. In most cases, the account manager provides us with funds to purchase lancets, strips, and medication for diabetes and hypertension. We buy medicine on a weekly basis, adjusting the quantity based on consumption levels. On one occasion, when I informed a nodal officer about the lack of drugs at the NCD clinic, he personally contributed Rs 5,000 [$71.4] and instructed me to utilize the money immediately to acquire the necessary medicine and consumables. (Health worker, NCD clinic)

The health worker shared his experience with the drug procurement process, highlighting the recurring issue of medicine shortages at the NCD clinic. The manager clarified that “local purchase” refers to procuring goods from local shops without engaging in a bidding or quotation process for purchases below Rs 15,000 (US $214.28). Upon further investigation, I discovered that the manager’s description of “local purchase” aligned with a specific financial rule. Rule no. 131C of the Bihar Financial (Amendment) Rule 2005 specifies that goods can be procured up to Rs 15,000 without the requirement of inviting quotations or offers. The rule states,

Rule 131C. Purchase of goods without quotation: Purchase of goods up to the value of Rs. 15,000/- (Rupees Fifteen Thousand) only on each occasion may be made without inviting quotations or bids on the basis of a certificate to be recorded by the competent authority in the following format. “I, ___________________, am personally satisfied that these goods purchased are of the requisite quality and specification and have been purchased from a reliable supplier at a reasonable price.” (Rule No. 131C, the Bihar Financial (Amendment) Rule 2005)

The Bihar Financial (Amendment) Rule 2005 is a set of guidelines that governs the procurement of goods and services by government departments. Table 4 outlines the procurement process and requirements specified in the rule.

Procurement of goods according to the Bihar Financial (Amendment) Rule, 2005

| Price range | Requirement as per financial rule | Documentation/Record-keeping process |

|---|---|---|

| Procurement up to Rs.15,000 | No quotation required | Certified and recorded by competent authority |

| Procurement between Rs.15,000 and Rs. 100,000 | Recommendation for the purchase of goods from identified suppliers after a survey by the purchase committee | Joint certification for the purchase by “Purchase committee” |

| Procurement above 100,000 | Through the bidding process depending upon the estimated cost and specification goods: (i) Advertised Tender Enquiry; (ii) Limited Tender Enquiry; (iii) Single Tender Enquiry | Assessment of bid by examining eligibility criteria, product specification, and other criteria |

Source: Bihar Financial (Amendment) Rule 2005.1

The “local purchase” process has been implemented to reduce administrative and bureaucratic involvement, as stated by the manager from the DSH. This system allows for flexibility in procuring medicine and drugs based on local needs. However, I discovered that managers were hesitant to purchase large quantities of medicine and consumable supplies due to a shortage of health workers in the NPCDCS program. One manager expressed the following concern:

There is no point in buying strips and drugs in large quantities because only a few staff members are working on the programme [NPCDCS]… Who will distribute the drugs and who will manage the programme? If something goes wrong, then who will be responsible and be held accountable? (Manager, DHS office)

The manager expresses concerns about the additional responsibility and accountability that comes with procuring large quantities of consumables. They highlight the potential challenges of drug distribution and the risk of wastage due to a shortage of staff. On the other hand, health workers believe that alternative mechanisms, such as involving hospital pharmacists or maintaining proper distribution records, can ensure transparency and accountability in the process. However, these discussions around accountability and transparency overshadow the concern for patient affordability. It’s important to note that medical drugs and consumables are regulated goods, and their procurement should ideally be supervised by qualified authorities. In contrast, health workers in the NCDs program receive cash to purchase medicine from the local market, as described in an interview with one of them.

Sometimes, the nodal officer provides us with money to purchase drugs and medicine. We take the money and buy them from a local private medical shop. If we feel that we don’t have enough medicine and consumables, we inform the nodal officer about the situation. In response, the nodal officer sometimes gives us money and instructs us to submit the bill to the account manager. At times, we visit the DHS office where the accountant provides us with the necessary funds to buy medicine. This is the process we follow to procure medicine. (Health worker, NCD clinics)

Health workers are regularly involved in the procurement process of drugs and medicines at the local level. They follow a sequential series of actions, including assessing the weekly requirement, informing the nodal officer, coordinating with the account manager, visiting the DHS office, receiving funds for procurement, visiting the local market to purchase medicine and consumables, coordinating with nodal officers for approval and signing of receipts, submitting the receipts to the accountant at the DHS office, maintaining procurement records in an inventory register at the NCD cell office, and informing other staff members about the availability of drugs for distribution.

The involvement of health workers in procurement is based on decisions made by managers, guided by official texts such as the Bihar Financial (Amendment) Rule 2005, the MoU, and NPCDCS guidelines 2013. However, these texts lack specific information to guide officers in making informed decisions. Some gaps in the texts include who should procure drugs from the local market, criteria for selecting shops and suppliers, and the required knowledge and understanding of the person involved in the purchase.

To address these gaps, managers interpret the official documents and engage in a text–reader conversation to form their own understanding. They align their actions with the conditions outlined in the official documents. Due to the lack of clarity in the texts, managers involve NCDs program health workers in the procurement process, allowing hospitals to provide free medicine to patients. However, this involvement significantly affects the primary work of health workers in the NCD program, such as providing counseling services to patients with common NCDs. Health workers often spend time coordinating with managers and nodal officers for procurement and may even need to convince managers to urgently procure medicine or consumables.

While managers and administrators are responsible for procurement, involving health workers in administrative tasks like purchasing drugs detracts them from their primary role of providing healthcare services. The regulatory texts provide guidelines but do not address the impact on service delivery caused by gaps in the text. This situation allows managers to manage health workers without considering the consequences on service delivery.

Discussion and Conclusion

Scholars have argued that a centralized procurement system can lead to cost reduction, improved efficiency, and increased transparency and accountability in procurement procedures (Bossert & Beauvais, 2002; Singh, Tatambhotla, Kalvakuntla, & Chokshi, 2013; Tatambhotla et al., 2015). However, this study reveals that the centralized procurement system can be influenced by local factors, such as corruption in purchasing organizations and the supply of substandard drugs. Despite the establishment of a specialized drug and procurement organization, namely BMSICL, to promote transparency and accountability, the organization failed to procure drugs for over 3 years.

The availability of drugs and supplies is considered a crucial factor for the success of integration (Watt et al., 2017). Insufficient availability of drugs in health facilities also increases out-of-pocket expenses for patients (Binnendijk, Koren, & Dror, 2012; Prashanth et al., 2016). The findings of this study align with previous research (Mackintosh et al., 2018; Watt et al., 2017), indicating that despite the provision of free medicine for common NCDs, most patients still purchase drugs from private health care providers. At district hospitals, drugs are often procured in small quantities to minimize administrative work. However, this approach fails to meet the demand for drugs in these hospitals. The Bihar Financial (Amendment) Rule 2005, a standard text for procurement of goods and services in Bihar, only outlines the procurement procedures such as local purchase, quotation, and tender. It does not specify which cadre of health workers or managers should be involved in the drug procurement process. As a result, local managers and officers are left to interpret the rule and find ways to navigate the procurement process. Increasing administrative support and implementing large-scale procurement at the district level could ensure drug availability for the NPCDCS program. The study highlights the influence of various institutional and regulatory texts that shape the implementation of integrated programs in district hospitals and carry the authority and instructions of the MoHFW. While these health societies were intended to be autonomous, the study reveals that their governance, decision-making, and autonomy were restricted through textual practices, despite their legal entity and autonomous status.

This study contributes to the social development and health system literature by illustrating how procurement at the central, state, and local levels is influenced by multiple factors. It emphasizes the need for policymakers to carefully consider the formulation of policies and examine how they are interpreted and utilized. The involvement of managers and officers in engaging frontline health workers in drug procurement, which goes beyond their job description, ensures drug availability but can temporarily disrupt service delivery at district hospitals.

Ethical Statement

Before commencing the fieldwork, ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Institute for Global Health and Development at Queen Margaret University, with reference number REP0280. Written and verbal informed consent was obtained from all research participants before their involvement in the study.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

Bigdeli, M., Laing, R., Tomson, G., & Babar, Z.-U.-D. (2015). Medicines and universal health coverage: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Pharmaceutical Policy and Practice, 8(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40545-015-0028-4https://doi.org/10.1186/s40545-015-0028-4

Bihar purchased drugs from blacklisted firms - Times of India. (2014). Retrieved from http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/patna/Bihar-purchased-drugs-from-blacklisted-firms/articleshow/37728561.cmshttp://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/patna/Bihar-purchased-drugs-from-blacklisted-firms/articleshow/37728561.cms

Binnendijk, E., Koren, R., & Dror, D. M. (2012). Can the rural poor in India afford to treat non-communicable diseases. Tropical Medicine & International Health: TM & IH, 17(11), 1376–1385. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.03070.xhttps://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.03070.x

Bossert, T. J., & Beauvais, J. C. (2002). Decentralization of health systems in Ghana, Zambia, Uganda and the Philippines: A comparative analysis of decision space. Health Policy and Planning, 17(1), 14–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/17.1.14https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/17.1.14

Campbell, M., & Gregor, F. M. (2004). Mapping social relations: A primer in doing institutional ethnography. Altamira Press: Walnut Creek.

Government of Bihar. (2005). The Bihar Finance (Amendment) Rules, 2005. Department of Finance: Patna.

Government of India. (2005). National rural health mission 2005. Retrieved from http://www.nhm.gov.in/nhm/nrhm.htmlhttp://www.nhm.gov.in/nhm/nrhm.html

Government of India. (2011). Operational guideline: National programme for prevention and control of cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and stroke (Npcdcs). Retrieved from http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=101234http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=101234

Joshi, R., Alim, M., Kengne, A. P., Jan, S., Maulik, P. K., Peiris, D., & Patel, A. A. (2014). Task shifting for non-communicable disease management in low and middle income countries – A systematic review. PLoS One, 9(8), e103754. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0103754https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0103754

Kearney, G. P., Corman, M. K., Hart, N. D., Johnston, J. L., & Gormley, G. J. (2019). Why institutional ethnography? Why now? Institutional ethnography in health professions education. Perspectives on Medical Education, 8(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40037-019-0499-0https://doi.org/10.1007/S40037-019-0499-0

Mabuchi, S., Sesan, T., & Bennett, S. C. (2018). Pathways to high and low performance: Factors differentiating primary care facilities under performance-based financing in Nigeria. Health Policy and Planning, 33(1), 41–58. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czx146https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czx146

Mackintosh, M., Tibandebage, P., Karimi Njeru, M., Kariuki Kungu, J., Israel, C., & Mujinja, P. G. M. (2018). Rethinking health sector procurement as developmental linkages in East Africa. Social Science and Medicine, 200, 182–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.01.008https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.01.008

Magadzire, B. P., Marchal, B., & Ward, K. (2015). Improving access to medicines through centralised dispensing in the public sector: A case study of the Chronic Dispensing Unit in the Western Cape Province, South Africa. BMC Health Services Research, 15(1), 513. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-1164-xhttps://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-1164-x

Manongi, R. N., Marchant, T. C., & Bygbjerg, I. C. (2006). Improving motivation among primary health care workers in Tanzania: A health worker perspective. Human Resources for Health, 4, 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-4-6https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-4-6

Plotkin, M., Besana, G. V. R., Yuma, S., Kim, Y. M., Kulindwa, Y., Kabole, F., … Giattas, M. R. (2014). Integrating HIV testing into cervical cancer screening in Tanzania: An analysis of routine service delivery statistics. BMC Women’s Health, 14(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6874-14-120/FIGURES/2https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6874-14-120/FIGURES/2

Prashanth, N. S., Elias, M. A., Pati, M. K., Aivalli, P., Munegowda, C. M., Bhanuprakash, S., … Devadasan, N. (2016). Improving access to medicines for non-communicable diseases in rural India: A mixed methods study protocol using quasi-experimental design. BMC Health Services Research, 16(1), 421. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1680-3https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1680-3

Prinja, S., Bahuguna, P., Tripathy, J. P., & Kumar, R. (2015). Availability of medicines in public sector health facilities of two North Indian States. BMC Pharmacology & Toxicology, 16(1), 43. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40360-015-0043-8https://doi.org/10.1186/s40360-015-0043-8

Rao, M., Rao, K. D., Kumar, A. S., Chatterjee, M., & Sundararaman, T. (2011). Human resources for health in India. The Lancet, 377(9765), 587–598. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61888-0https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61888-0

Singh, P. V., Tatambhotla, A., Kalvakuntla, R., & Chokshi, M. (2013). Understanding public drug procurement in India: A comparative qualitative study of five Indian states. BMJ Open, 3(2), e001987. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001987https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001987

Smith, D. E. (1987). The everyday world as problematic: A feminist sociology. Northeastern University Press: Boston.

Smith, D. E. (1999). Writing the social: Critique, theory and investigations. University of Toronto Press: Toronto. https://utorontopress.com/9780802081353/writing-the-social/https://utorontopress.com/9780802081353/writing-the-social/

Smith, D. E. (2001). Texts and the ontology of organizations and institutions. Studies in cultures, organizations and societies, 7(2), 159–198.

Smith, D. E. (2005). Institutional ethnography: A sociology for people. AltaMira Press: Lanham.

Smith, D. E. (2006). Institutional ethnography as practice. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc: Lanham.

Smith, G. W. (1990). Political activist as ethnographer. Social Problems, 37(4), 629–648. https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.1990.37.4.03a00140https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.1990.37.4.03a00140

Tatambhotla, A., Chokshi, M., Singh, P. V., & Kalvakuntla, R. (2015). Replicating Tamil Nadu’s drug procurement model. Economic and Political Weekly, 47(39), 7–8. Retrieved from https://www.epw.in/journal/2012/39/commentary/replicating-tamil-nadus-drug-procurement-model.htmlhttps://www.epw.in/journal/2012/39/commentary/replicating-tamil-nadus-drug-procurement-model.html

The Global Fund. (2008). The Office of the Inspector General Procurement, supply chain management and service delivery of the global fund grants to the Government of India. Retrieved from https://www.theglobalfund.org/media/2588/oig_procurementandscminindia_report_en.pdfhttps://www.theglobalfund.org/media/2588/oig_procurementandscminindia_report_en.pdf

Waako, P. J., Odoi-Adome, R., Obua, C., Owino, E., Tumwikirize, W., Ogwal-Okeng, J., … Aupont, O. (2009). Existing capacity to manage pharmaceuticals and related commodities in East Africa: An assessment with specific reference to antiretroviral therapy. Human Resources for Health, 7, 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-7-21https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-7-21

Watt, N., Sigfrid, L., Legido-Quigley, H., Hogarth, S., Maimaris, W., Otero-Garcıa, L., … Balabanova, D. (2017). Health systems facilitators and barriers to the integration of HIV and chronic disease services: A systematic review. Health Policy and Planning, 32, iv13–iv26. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czw149https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czw149

Wirtz, V. J., Hogerzeil, H. V., Gray, A. L., Bigdeli, M., de Joncheere, C. P., Ewen, M. A., … Reich, M. R. (2017). Essential medicines for universal health coverage. The Lancet, 389(10067), 403–476. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31599-9https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31599-9

Vikash Kumar is Assistant Professor, Department of Social Work, Northern Michigan University, Marquette, MI, USA. He can be contacted at vkumar@nmu.edu.